1

Community-Led Research through an Aboriginal lens

L. Riley (2021). Community-Led Research through an Aboriginal lens. In V. Rawlings, J. Flexner & L. Riley (Eds.), Community-Led Research: Walking new pathways together. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

There is no argument that since the arrival of the British on the shores of what is now known as Australia, the First Nations people have been affected in ways that have at the least traumatised and irrevocably changed their lives, culturally, politically, legally and socially. It is also very clear that this is due to the impact of research undertaken by the British who focused, directed and in turn used this research in policy directions aimed at controlling Indigenous lives. This research commenced at the onset of contact, with the ‘Secret Instructions’ given to Cook on his journey to Australia:

You are likewise to observe the Genius, temper, disposition and Number of the Natives, if there be any, and endeavour by all proper means to cultivate a Friendship and alliance with them, making them presents of such Trifles as they may Value, inviting them to Traffick, and Shewing them every kind of Civility and Regard: taking care however not to suffer yourself to be surprised by them, but to be always upon your guard against Accident.

You are also with the Consent of the Natives to take possession of the Convenient Situations in the Country in the Name of the King of Great Britain; or, if you find the Country uninhabited take possession for his Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions as first discovers and possessors. (See National Library of Australia, nd; Smith, 2010)

This research focus created the many ways in which Indigenous Australians have been viewed and then governed in Australia (Robinson, Flexner & Miller, this volume). Research was undertaken initially to find out about the people in the southern lands, so that the King of England and his people could best learn how to utilise them, their country and their resources for their own advantage. Engagement was viewed as a one-sided venture to benefit the British, not necessarily to create equitable relations or resources for Indigenous Australians. As such, it was in the interests of the British to claim Australia as being terra nullius, despite the writings of Cook in his journal that highlighted seeing Aboriginal people going about their daily lives and occupation of Australia from his ship. As Cowlishaw (2013) states, the emphasis in early research was to support Australia as being terra nullius, and was carried out without permission, consultation or involvement of First Nation peoples. Hart and Whatman (1998) observe that:

The premise of most [Western] research and analysis has been locked into the belief that Indigenous Australians are anachronisms and, in defiance of the laws of evolution, remain a curiosity of nature, and are ‘fair game’ for research. The overt and covert presumptions underwriting all [Western] research and analysis into Indigenous Australian cultures is the inherent view of the superiority of Non-Indigenous society’s cultures. (p. 3)

This chapter will provide an overview of the focus of research approaches and the impact of research on Indigenous Australia; what needs to be considered in research with Indigenous Australia; new debates and directions in research with Indigenous Australians through both international and national Indigenous influences, and why this is relevant; and what is often the reason Community-Led Research (CLR) is used in research. It will explore some of the do’s, don’ts and concerns in where and why CLR should be used with Indigenous Australians.

Indigenous research impact

It must be recognised that until most recently the majority of research undertaken on Indigenous Australia has been through the lens and/or influenced by anthropological research, in both the framework of study – the methodologies used – and in the analysis of the data collected.

The history of the literature on Aborigines is the history of anthropological hegemony and in the recent contributions from educationalists, historians, psychologists and political scientists, there is a tendency to rely on anthropologists’ work for authoritative statements concerning Aboriginal traditions. It seems important therefore to define the limits of the anthropologist’s area of expertise and admit that the discipline has no special authority in the area of what is called ‘social change’ or in the analysis of the kind of society into which Aborigines have been incorporated. The bulk of social anthropology in Australia on Aboriginal society until recently may be more accurately described as social archaeology. (Cowlishaw, 2013, p. 75)

Cowlishaw (2013) in her review of the work of anthropologists and their research of Indigenous Australians, stated that anthropologists have been extremely influential in how Aboriginal people and their societies were viewed and ‘understood by Australian intellectuals, politicians, journalists and now by the land courts’ (p. 61). What is important to clarify here is that whilst this research was done on Aboriginal people, the influence of the research in controlling Aboriginal lives, through the development of policies and ongoing structural systems and practices, is the key to the ongoing marginalisation of Indigenous peoples (Moore, Pybus, Rolls & Moltow, 2017).

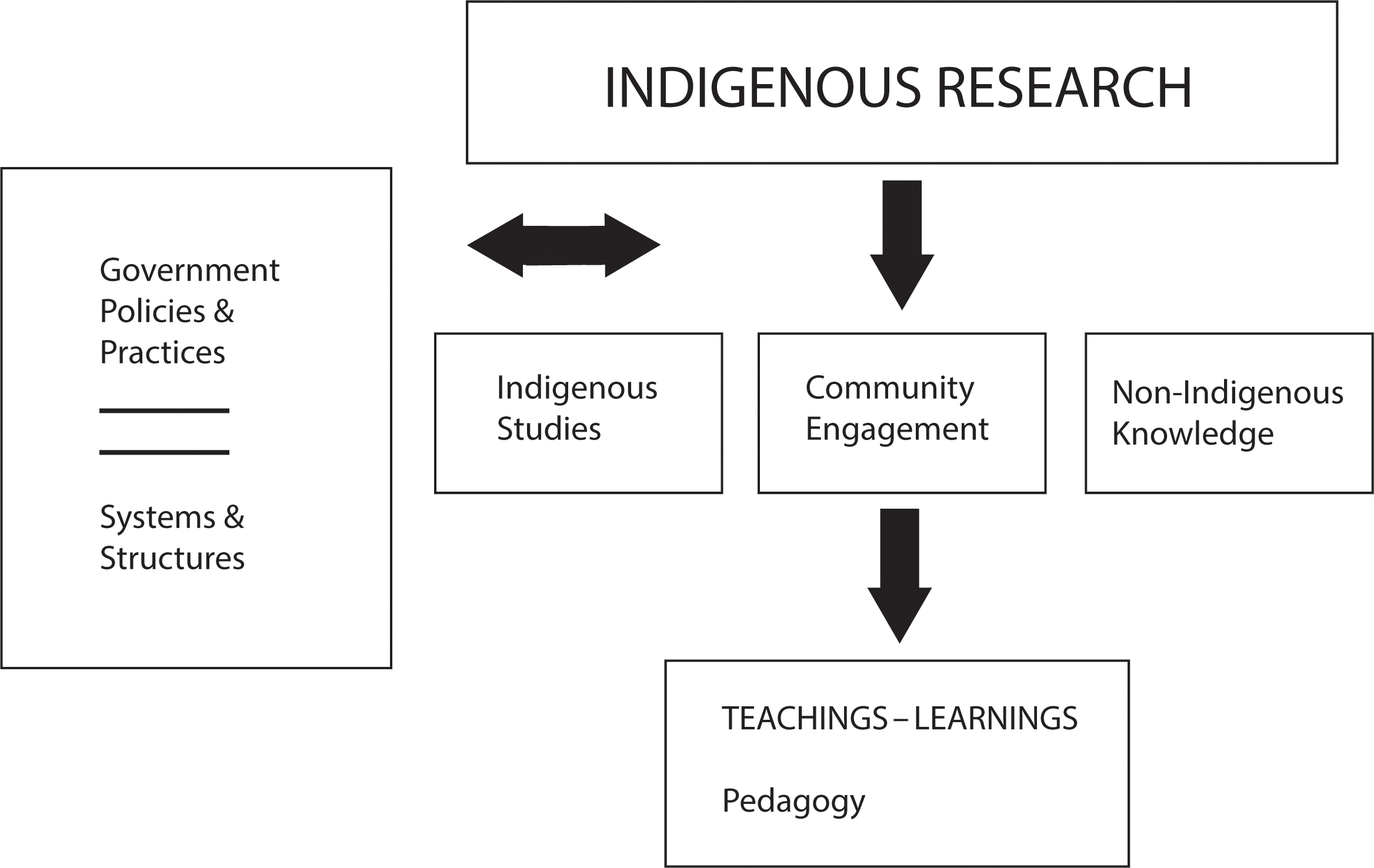

Figure 1.1, showing the Indigenous research impact flowchart, highlights the impact of research on First Nations peoples and how it has governed the studies undertaken, the approaches to Indigenous community engagement, and specifically the knowledge and understanding of non-Indigenous Australians:

Figure 1.1 Indigenous Research Impact

Research undertaken has created and affected:

- Indigenous studies: the type of studies done in relation to Indigenous people, initially undertaken and developed to work in remote communities with Indigenous peoples;

- Indigenous community engagement: the style and type of Indigenous community engagement, often using a patriarchal and Western-dominated approach; and

- Non-Indigenous people’s knowledge of Indigenous Australians, which helped govern personal and wider relationships in society; and one could also say led to the rise of racism and the stereotypes attributed to Indigenous peoples in Australia.

These three factors have been influential in forming government policies and the practices of organisations and structures for not only social systems in Australia, such as education, health, housing and employment opportunities, but also for how private organisations and businesses have interacted with Indigenous Australians. This has in turn influenced teachings and learning about Indigenous Australia. The pedagogical approaches in education with Indigenous students – that is, the ways in which Indigenous people have been taught, or been allowed to engage in education – and the ways in which learning through curriculum developed for all other Australians, outside of anthropology, about First Nations peoples have been undertaken in the past and currently are seen as relevant or irrelevant, across all levels of education (Moore, Pybus, Rolls & Moltow, 2017; Cowlishaw, 2013).

The influence of these processes combines to impact the range of policies and practices utilised in Australia, which form our social systems and the structures to govern our nation. This in turn affects Indigenous peoples’ place in Australian society – how they are viewed and the ways in which they have been affected by past and ongoing policies and practices, which has in effect led to exclusion on multiple levels in our current society (World Health Organization, 2019; Popay, et al., 2008). This therefore means that to ignore the past research undertaken on Indigenous Australians, how this research was undertaken, and the Western methodologies and influence in analysing this data, would mean maintaining a coloniser’s view of Australia and ensuring Indigenous Australians remain marginalised. It is imperative therefore that we make sure that Indigenous Australians are able to determine what research is required to be undertaken and how this will be done in order to ensure their cultural, political and social needs are met, and are not simply determined by external agencies.

History of research approaches on Indigenous Australia

Cowlishaw (2013) has described six layers of research through anthropology that have influenced political and social structures for Indigenous Australians since contact commenced with the British in Australia in 1788 – the first two being the Moving Frontiers (1800s–1930s) and the Protection Era (c. 1860s–1890s). Cowlishaw (2013) comments that these two eras are reflective of maintaining the premise and legal doctrine of Australia being founded on ‘terra nullius’. That is, that no people lived in Australia, it was not populated and had no productive civilisation occupying the lands. This doctrine has been refuted by many people since this time (Pascoe, 2018). The research in these two eras, whilst focused on ‘terra nullius’, also reinforced this premise and was undertaken on Indigenous Australians without their permission, consultation or involvement. Cowlishaw (2013) states that a clear issue was the way in which Indigenous people were viewed in this research, in that:

Anthropologists’ definition of Aborigines was always dependent on notions of their cultural integrity and homogeneity. No concepts or theories were developed within Australian anthropology which could adequately deal with either relations between the indigenous population and the invaders or with changes in either. (p. 61)

and that further:

when anthropologists did conduct research with non-traditional groups the very vocabulary of ‘caste’ and ‘blood’ with which such groups were described, relied on biological ideas of race, and the search for the traditional also relies in the final analysis on the reification of race. (p. 61)

Clearly, anthropology was used to support the Western belief of one theory of evolution – and the idea of Westerners’ own superiority, seeing themselves at the top of the evolutionary ladder, was well entrenched in research.

The third era discussed by Cowlishaw (2013) is Coercive Segregation (the late 1890s into the 20th century) which was based on a conservative approach that determined the importance of having national development; that is, one national identity into which all other cultures and races must be subsumed – a ‘White Australia’ identity. This in turn diminished Indigenous culture, languages and narratives in their landscapes, placing Indigenous peoples at the bottom of the social hierarchy through social marginalisation due to their cultural differences.

The fourth era of research reinforced a need for Assimilation (1930s–1960s; Cowlishaw, 2013), and created a revisionist reinterpretation. This led to some correction of the conservative approach and allowed Indigenous voices to be heard and some aspects of hidden or excluded histories to come to light; however, the key focus was on forcing First Nations peoples to divest themselves of their culture and take on the cultural mores of the British.

The fifth era in research introduced Rights and Self-Determination (1970s–2000; Cowlishaw, 2013) and opened greater dialogue, engagement and participation for Indigenous people. This was often due to Indigenous people gaining political voices and being heard on a national and international level, with their fights for Indigenous rights. The sixth era of research, Indigenous Directives, arose since the 2000s, and has created more forums where Indigenous peoples can direct and inform what Indigenous Studies should be and has also generated new research paradigms.

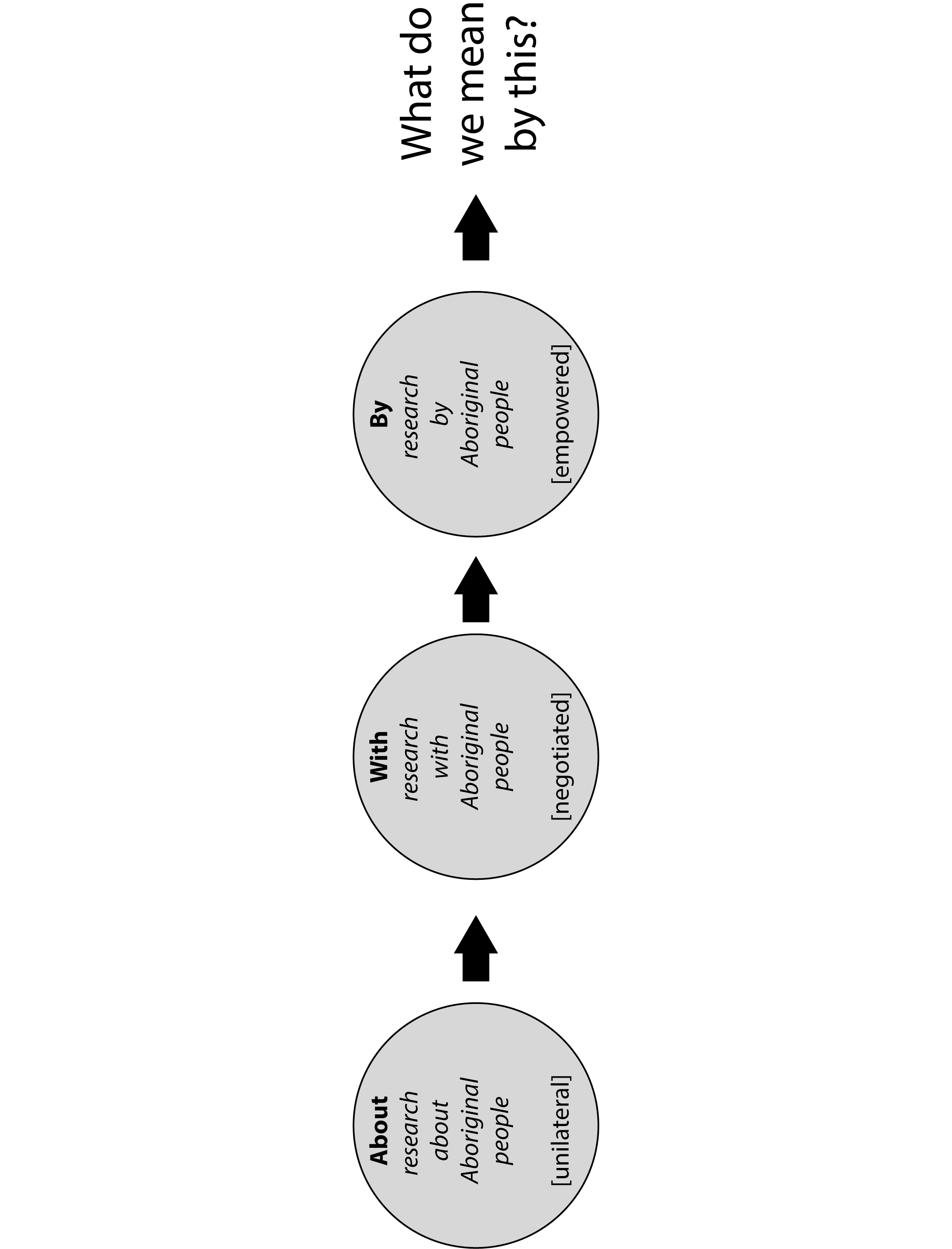

As such, we can clearly see a change in the approaches being undertaken in research concerning Indigenous peoples, as reflected in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Research and Aboriginal People (after Driese & Mazurski, 2018, p. 14)

Driese and Mazurski (2018), in Figure 1.2, highlight that where research is undertaken about Indigenous people it is unilateral and allows no engagement with Indigenous people and all the control of the research is outside of Indigenous peoples’ parameters. Research with Indigenous people allows some negotiation, but control of the research – who runs it, where it is undertaken and who is involved – again is outside of Indigenous control. Research by Indigenous people allows for an empowered situation to occur, where Indigenous people control what research they want undertaken, who is involved in the research, where the research occurs and how the data gets analysed. When carrying out research we need to be very clear how the research is undertaken to allow optimum empowerment of Indigenous communities, to resolve their own community directions and crises and provide self-determination for them and their communities.

What do we need to consider to empower Indigenous research?

In assessing what is required to empower Indigenous peoples through research, the responses to the following questions need to be known, considered and understood.

- Indigenous research methodologies – how do they differ from other areas of research?

Be aware of what is entailed in Indigenous research methodologies, how these may differ from or support Western research methodologies, and how they empower Indigenous peoples’ directions. - What does privileging voices in research mean? How does this influence knowledge and teaching?

Acknowledge and learn how research often privileges Western voices and rhetoric and how we can change the way we undertake research to privilege Indigenous voices and empower Indigenous communities. - Are Indigenous research methodologies important? Why?

Study the impact of research that has a Western approach and that may not privilege Indigenous voices, and how this may have a negative impact on Indigenous communities’ needs and goals. Alternatively, how can this be changed to ensure Indigenous voices are privileged to ensure positive impacts for Indigenous peoples? - What does disrupting Western research mean?

Explore the differences between Western and Indigenous research methodologies and what must be done to empower Indigenous communities through their research requirements. - What does working with Indigenous communities mean?

Assess the importance of different cultural protocols and how these influence community engagement and voice in research practice and procedures. - How can we ensure Indigenous voices are included?

Ensure research methodologies commence with Indigenous voices and Indigenous control of the research processes, directions, analysis and outcomes. - Why is ‘decolonality’ important? What does it mean in research and in the transmission of knowledge?

Decolonality starts with assessing the self in understanding the purpose of the research to be carried out and who the research serves to support. If in this reflective process you realise that the research does not support the research participants of the research – that is, the real value of the research goes towards empowering the researcher – then you must check the validity of the research and acknowledge whose privilege it serves. Decolonality starts with self-reflection and understanding the ultimate purpose of the research. - What is the impact of Indigenous histories and representation through museums? Understand the role museums have played in collecting and cataloguing Indigenous peoples and their cultures. Issues that need to be raised are:

(i) What consultative processes have been used and what processes have been put into place to allow Indigenous communities to veto particularly significant cultural items from public display?

(ii) Historiography: The need to understand actions in the past from the viewpoint of the participants – scientist, missionary, Aboriginal Elder, etc. – and how each must be understood in light of the era’s political and social barriers.

(iii) Museums are sites for continued learning in that they have acquired many cultural items, which may now need greater cultural and social commentary from Indigenous peoples; and/or greater access to view items in privacy to allow communities to mourn the loss of items and remember people these items were linked to; and/or have items of significance returned, through repatriation programs.

(iv) Determine what steps you would take in a museum when working with human remains; consider different cultural protocols if the human remains are Aboriginal, Islander or European. - What impact does nationhood, statehood and sovereignty have on us as Australians?

Remember that different policies reflect the directions of each nation. This will have an impact on how policies are implemented and the level and type of engagement of people from different Indigenous cultural backgrounds. - What is important about Indigenous cultural and intellectual property and how does it impact on Indigenous research methodologies?

The understanding of who has the final say regarding the ownership of cultural items and the provision of intellectual property is the practice of privileging Indigenous peoples’ authority to veto and/or support research, items collected and/or displayed. - What is the importance of place-, space- and time-based methodologies? What role does perspective play in these?

Byrne and Nugent (2004) discuss this within the following three parameters of knowledge keeping and re-telling, which requires a clear understanding of the use and influence of:

(i) Archives – who collects them, where they are kept, access to records, style of recording keeping, recognition of oral heritage through yarning, and styles and types of mapping. The issues are: what exists, what are the gaps, who interprets this material, and the impact of change across different eras.

(ii) Landscape – mapping spatial areas, what or who influences changes in landscapes, what lies beneath the layers of history and keeping of records, what are Aboriginal interpretations of landscapes vs Western interpretations? The issues are: what’s in a name, history of contact, policies and wider community engagement or exclusion for Indigenous peoples, places of control, and are Indigenous people and their places of significance used as tourist attractions in differing landscapes.

(iii) Lives – through lived stories and histories; are they published or oral stories and histories, what is used as corroborating evidence, what is visible and invisible in these histories, recognising how cultural lives are not included in archives. The issues are: the interpretation of these histories – who does it, the quality of past recordings of people’s stories, the ethics employed in the collection of material, and is there understanding and recognition of intellectual property in the collection and use of material.

Sommerville (2013, p. 42), in discussing her research and the importance of Aboriginal peoples’ perspectives of place, space and time, reflects that inclusion of and listening to Aboriginal people provided her with

an important story that might offer a way to enter a different sort of understanding of place and identity in Australia …

I had many unanswered questions. Where did this story fit into the landscape? What were the places of its beginning and ending? How did it connect with the multitudes of other stories about the creation of the landscape and all of its creatures? These are complex questions that are part of a larger context that has taken me ten years to begin to unravel … So I go to a place I have been to before, a taken-for-granted beach place, like all other beach places in Australia. On the one hand, I have a deep sense of the significance of this place, the intensity of the storylines that intersect there, but on the other hand, it is just a normal beach place with a caravan park and estuary, headlands, beach, and sea. How do I reconcile these things? What sense can I make of the intersection of these meanings? In a sense these questions are the quintessential questions about writing.

Indigenous histories, culture, stories and perspectives intersect to create a depth of knowledge about the Australian landscape for different places, spaces and times; if these are not included, there is no real understanding of Australia.

Processes for Indigenous research

It is vital that researchers (Robinson, Flexner & Miller, this volume) understand the different cultural protocols (Welsh & Burgess, this volume) required in any research process and that these will be different to the requirements of Western research processes. The model of the processes used in the Kinship Online Project (Mooney, Riley & Howard-Wagner, 2016) differs from Western research processes.

The following articulates the various stages and actions undertaken in the research model established by Mooney, Riley & Howard-Wagner (2016, pp. 24–27). This model demonstrates how research with Indigenous people (Webster, Hill, Hall & See, this volume; Welsh & Burgess, this volume) needs to be more critical and reflective through the provision of longer time frames, to guarantee appropriate research is undertaken with the consent of Aboriginal people and for the benefit of their communities. It is important to point out that in this model the key to the different engagement processes is that for Aboriginal people it is the validity of the people involved through relationships and knowing one another, through following Aboriginal protocols, that will be the primary focus of who should be engaged – from both the academic and the Aboriginal community – in the research. In the Western processes, the engagement in research is based on the credentials of the researcher, such as having a doctorate, which is acknowledged and recognised through Western academia.

The stages for Aboriginal engagement identified in this model were:

Precursor – Informal

This informal process commenced at least six to twelve months prior to any research ideas in order to gauge people’s thoughts on whether they believed it was a worthy project. Through meeting with local community, engaging with potential research assistants and assessing venues and locations for meetings, it was ensured that the Aboriginal community protocols for the validation of researchers were adhered to.

Stage 1: What if?

Ask questions and work with the community to determine the viability of the research. Some questions asked were: What if we were to submit a proposal for a grant to do …?; Would you think this is a good idea?; Would you be supportive of the research?; In what way could you be supportive?; Where could we hold workshops?; Who do you think could/should be involved in organising events/components for this research in …?; Who should be invited to participate in the workshops for the research?; If we apply for the grant, and if and when the ethics process is cleared, does anyone want to be contacted further about the research?

This undertaking first required speaking informally to various Aboriginal agencies in the community and members of the local Aboriginal community and wider region – to see who thinks the research is worthy and who would want to be involved. Additionally, statewide or regional consultation may also be required if the research falls under the parameters of any regional or statewide organisation.

Stage 2: Informal and formal notification

Local Aboriginal community organisers were recognised as valid and were needed to be seen as neutral within the Aboriginal community; able to speak across and for a wide cross-section of the community; and have reliable access to resources to assist in the research project.

Stage 2 occurred following the university’s formal notification of the grant and ethics approval and prior to the research being conducted. This also involved building research relationships and providing a research training session for community members, looking at issues such as: what research ethics processes are, how and why the research is being run, the importance of the community being involved and their role in the project. This helped create a formalised plan while being mindful to build the local community’s capacities in what formal research is and ensuring additional time for discussions to understand academic research and the ethics processes involved. This meant that people in the community gained a more in-depth knowledge of academic research, which they could use should any research proposals be put to their community in the future.

Stage 3: Familiarisation with ethical research processes

Familiarise the Aboriginal community with the academic ethics process and how this influenced the collection of the research data. The following steps were undertaken:

i. Interviewing process: Ethics process. A workshop was held for the Aboriginal community to provide an oral explanation and an information sheet on university ethics processes, aligned with their involvement to ascertain their expectations of and objectives for the research. This meant all stakeholders had a clear understanding of their roles and who they could go to if any problems arose during the research.

ii. Interviewing process: Data collection. A workshop was held to discuss the data collection process with local community research assistants. These discussions covered issues such as: ethics, identifying participants for interviews, the type of information sought, and the types of questions we could ask participants.

Stage 4: Formalising the process with the local community

i. Finalising the research: Formal and informal. Continuous phone and email contact be seen as keeping the process on track, but must not be seen as harassing participants; it is imperative for ongoing relationships, that face-to-face follow-up visits from the academic team be made regularly in the interview process and research completion; and in turn include participants in the evaluation and how the reports will be written, such as, what the language style will be, for example, Plain English.

ii. Follow-up: Formal and informal. Hold a survey of the community interviewers who accumulated the data and collect their perspectives on the strengths and problems with the research process.

iii. Dissemination: Formal and informal. Determine with the community how the research results should be disseminated, debrief how they thought the project went, and gather ideas for improvements. Always ensure provision of a verbal report, which will also include a demonstration of material collected, followed by the written report.

iv. Production of the final report. Produce a final report detailing the research: aims, approach, methodology; and the impact and evaluation of the project. Include community input from surveys and/or oral comments from community feedback sessions.

Western research – Aboriginal community engagement

As stated by Mooney, Riley and Howard-Wagner (2016, p. 27), a key concern in any Western research which aims to have strong community engagement is:

When carrying out research with Aboriginal people and in Aboriginal communities, there is often tension between Western approaches – how the university and ethics tell you it must be done and how Aboriginal people view the research being carried out. The role of the researchers, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, is to ensure that while the ethical processes are adhered to, Aboriginal people and their communities feel engaged and know that the researchers aren’t in control of them. Hence it is vital that researchers understand how to conduct research with Aboriginal people and their communities. If researchers are not culturally competent, it may mean that Aboriginal communities have a ‘bad’ experience or could be ‘harmed in some way’ (see Sherwood, 2010, cited in Mooney, Riley & Howard-Wagner, 2016) and not wish to be engaged in future research projects, thus creating difficulties into the future.

Therefore, it is imperative to be clear on what we mean by community participation in research and how this influences academics in the use of community-led approaches in research, to ensure Indigenous voices and directions for research are privileged.

Debates and directions

Debates surrounding Indigenous peoples’ level of engagement in research and their rights in research have been substantial. Early declarations of support for Indigenous people have been published by a range of organisations, most particularly in relation to work with linguistics and the research undertaken on Indigenous languages, such as that released by the Australian Linguistic Society (1982, n.p.), which stated that:

In any dealings between a community and linguists, the community has the following rights:

1. To finalize clear and firm negotiations to the community’s satisfaction before the linguistic fieldwork is undertaken.

2. To know and understand what their work involves, their obligations to the community and the restrictions they must observe using a paid local interpreter at all times if the community so requests.

3. To request a trial period before giving full permission for the research to continue.

4. To control research if the community wishes and also to request the linguist to consult with relevant community organizations where appropriate.

5. To ask for their help in language matters, training and other ways.

6. To receive regular summaries and results of the linguist’s work written and presented in a way that the community can understand.

7. To privacy and secrecy with respect to person’s names, confidential information, secret/sacred material and publication.

8. To approve the content of material before publication.

9. To see its members adequately paid in cash or otherwise for their services, and properly acknowledged in publications.

10. To negotiate for a share of royalties from any publications.

11. To be advised and receive a copy of any subsequent publications related to the research.

From these basic tenets, which are concerned with negotiated participation, other agencies have published their support of these rights, such as: Federation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages (2004); NSW Board of Studies (2008); Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (2012); and National Health and Medical Research Council (2018; 2003). The key concern is to what extent have these guidelines been understood in research, adhered to and actioned? If these current guidelines were to be followed by all researchers or agencies working with Indigenous communities, community-led approaches would be seen as central and an imperative in all research that might be considered, planned or undertaken.

Within these tenets are the ways in which Indigenous knowledge is given authority and authenticity, as often Western processes within systems such as universities are often valued more highly than Indigenous peoples’ knowledge systems and ways of doing business (Moore, Pybus, Rolls & Moltow, 2017). In such cases we need to assess the research sources and ask what is seen as being provided with more priority and/or authority and what is seen as more authentic, such as:

Elders or archives?

- What source is given more prominence or validity?

Language recording and revival – speakers or linguists?

- Who is considered a valued speaker and by whom?

Expert rhetoric

- Who is considered an expert in research and by whom?

Discourses of death and sleep – where often non-Indigenous sources proclaim that there is no knowledge or it is ‘dead’, yet for Indigenous people it is seen as ‘hidden’ or asleep’ and just waiting to be re-woken.

Who has the cultural knowledge and expertise?

- Often Indigenous people may be hesitant to volunteer their cultural knowledge, due to past historical negative policies and punishment for this knowledge. As such, who has knowledge and who is willing to provide this can change, as Indigenous people feel more valued and respected and have developed a relationship of trust with researchers.

Language ‘engineering’

- Whose language is being used to record material and how material is translated to ensure it reflects Indigenous peoples’ knowledge and it isn’t being ‘Westernised’.

Protocols, power and control

- The benefits of gatekeeping and/or who are the gatekeepers and why is this control used?

Sources, veracity and usefulness of the material collected

- Who gets to ascertain this? Westerners or Indigenous people who have direct kinship relationships to the area and knowledge?

Access

- Who can speak, learn and teach the material being given and researched?

Collaboration or competition?

- Is there a clear understanding of who has the right to veto or acquiesce to the material collected?

Collective responsibility

- Is there a clear agreement on a collective responsibility for who has the rights to be the person who has the cultural knowledge and where does this come from?

These issues listed above need to be openly challenged and debated to ensure Indigenous voices are privileged in research undertaken.

A key question we need to ask as researchers, particularly in our roles within universities, is: How do we, as Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal researchers, undertake Indigenous or Indigenous-focused research and meet the requirements of the university and Aboriginal communities?

This is particularly important as we need to understand, within the university context, the overall purpose of research we are asked to undertake. In answering this question, we need to explore what methodologies we are using, whose voice it privileges, and how can we ensure Indigenous peoples are able to lead the research?

Methodologies

Is assessing these issue raised above, we need to be aware of the range of Indigenous academics who are challenging and utilising Indigenous methodologies in research (Moore, Pybus, Rolls & Moltow, 2017). Below are some Indigenous researchers and methodologies demonstrating research methodologies incorporating Indigenous ways or knowing, being and doing.

Internationally – First Nations academics in Canada, USA, Aotearoa (New Zealand). Nationally – Indigenous academics in Australia who have been influencing methodological reform. These lists are preliminary lists and not limited to these Indigenous academics. Take the time to look at the work being done by these influencers, and ask how they might shape your own work as an academic.

|

International Indigenous influencers | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Linda Tuhiwai Smith |

Decolonising Research & Culturally Appropriate Research |

|

Graham Smith |

Maori Theorising & Indigenising Education |

|

Fiona Cram |

Constructive Conversations |

|

Jo-ann Archibald |

Story Work |

|

Margaret Kovach |

Relational Research |

|

Suzanne SooHoo |

Culturally Responsive Research Methodologies |

|

Mere Berryman |

Culturally Responsive Research Methodologies |

|

Anne Nevin |

Culturally Responsive Research Methodologies |

|

Shawn Wilson |

Research is Ceremony & Building Knowledges for Community |

|

Gregory Cajete |

Ethobotany – Culturally Based Science/Indigenous Perspectives in Science |

| Australian Indigenous influencers | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Aileen Moreton-Robinson |

Indigenous Women’s Standpoint Theory |

|

Tyson Yunkaporta |

8 Ways & Protocols in Working with Community |

|

Nerida Blair |

Lilyology |

|

Karen Martin |

Booran Mirraboopa – Ways of Knowing, Being & Doing |

|

Bronwyn Fredericks |

Indigenous Engagement in Research |

|

Lester-Irabinna Rigney |

Reforming Indigenous Research – defined and controlled by Aboriginal people |

|

Dawn Bessarab |

Yarning |

|

Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann |

Deep Listening |

|

Mark Rose |

Practitioners Blindspot & Reflection |

|

Wendy Baarda |

Cultural Difference |

To understand and utilise community-led approaches requires being aware of how to best use and acknowledge Indigenous people’s methodological approaches.

What’s working?

In working with Indigenous peoples it is important to understand what methodological approach is working and which communities it works in, as not all approaches will work with all Indigenous communities for a range of reasons, such as:

- History of contact and interrelationships developed in the community between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people – this is linked closely to experiences of racism in the community.

- Academic levels of education of Indigenous people in communities and their previous experiences – positive and negative – in education.

- Social levels – health, economic position, that is, poverty level, availability of work in the community, and housing access; these factors are all tied into one another and will influence Indigenous peoples’ engagement with academics.

As an academic, being aware of and understanding these influences for Indigenous peoples assists in determining the best approaches that work for different Indigenous communities (see Welsh & Burgess this volume).

Influences on Indigenous research and purposes of the research?

It is essential when developing research approaches and engagement with Indigenous peoples that there is an understanding of what Indigenous peoples expect to gain from the research (Webster, Hill, Hall & See, this volume), such as that elucidated by Rigney (2003, p. 39):

- Resistance as the emancipatory imperative in Indigenist research

- The political integrity of Indigenist research

- Privileging Indigenous voices in Indigenist research:

Rigney (2003) is highlighting first, that Indigenous people are often resistant to research that does not benefit them and that this is often proved to them by their many past experiences of being researched, with no benefit to them or their communities. This establishes their right to refuse any research and it is in their interests to do so – without prior and informed information and proof of how the research will benefit them and their communities. Second, that research has often been tied to political agendas of control and disempowerment, taking Indigenous people’s resources and excluding them from mainstream processes – enforcing them as marginal citizens within their nation states. Third, that research must ensure Indigenous voices are privileged and are seen as the first voice in determining what research needs to be undertaken, how it will be undertaken, how the data will be analysed and by whom, and how the data will be written and distributed. It is only when these three research issues are openly addressed and resolved that Indigenous people should enter into any research proposal.

Indigenous research teaching and learning

What academics should be aiming to achieve in their research for Indigenous peoples is to:

- Build knowledge of pre-contact culture, colonial violence and intergenerational legacies.

- De-mythicise pre-contact culture.

- Equip academics to practise in more culturally sensitive, appropriate and safe ways for Indigenous people.

- Reduce ethnocentric and class biases, and accommodate differing social and cultural backgrounds.

- Change past representations of Aboriginality, based on stereotyping, racialised narratives and negative representations that sought to inferiorise Indigenous peoples and their cultures.

- Contribute to a society inclusive of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as equal citizens, without the requirement to abandon their cultural heritage.

These aims should be clearly articulated in all research proposals in relation to Indigenous peoples.

Communication, consultation and interaction

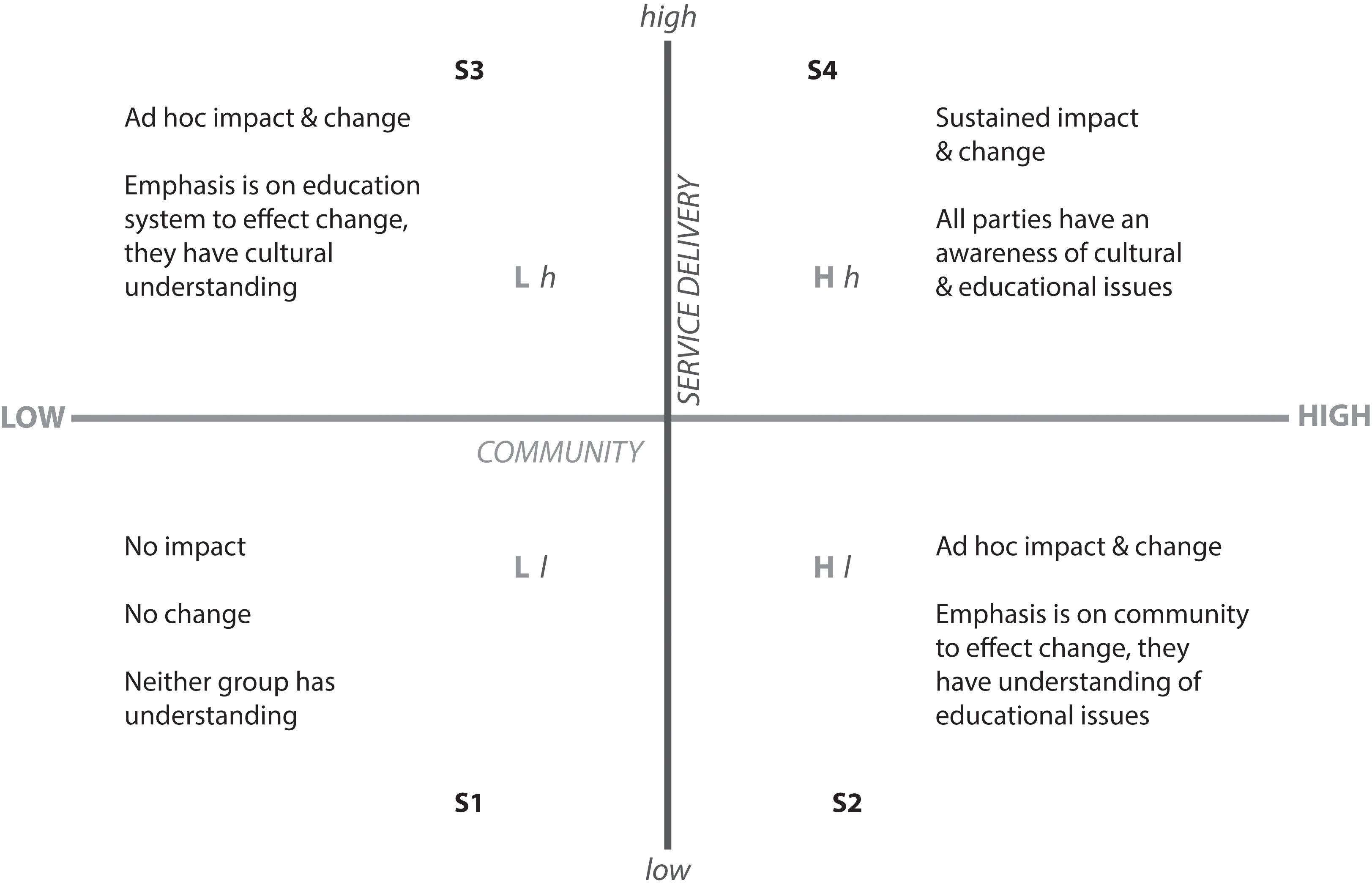

The key to research and outcomes which lead to sustainable change for communities is the level of communication, consultation and communication that exists (Welsh & Burgess, this volume), aligned with knowledge of each other, such as for service delivery agencies, knowledge of Indigenous peoples’ culture, cultural operations and protocols; and for Indigenous people, it is knowledge of the service delivery agency’s operations, systems, processes and strategies for achieving aims, goals and practice. If these do not coincide, or are one-sided, then sustainability will not be created. Figure 1.3 outlines the interaction between communities and service delivery agencies for sustainable practices to occur through communication, consultation and interaction.

Community – understanding of institutional processes

Institution – understanding of Indigenous history, culture and interrelations

Figure 1.3 Communication, Consultation and Interaction (Riley-Mundine, 2007).

Figure 1.3 presents the interaction of the community – on the horizontal line – who may have a low or high understanding of service delivery agencies. The vertical line represents the service delivery agencies’ understanding and knowledge of Indigenous communities, cultures and histories, which is either low or high. The intersection of these will create either no change, ad hoc change or sustainable and ongoing changes, as outlined below:

Scenario 1 (S1): Indicates that neither the Indigenous community nor the service delivery agency have any knowledge of one another. This means that there is no communication between the groups and that no change will occur to operations for the community. It may also indicate that active racism is occuring in this community, which will impact on the interactions between parties.

Senario 2 (S2): Indicates that the community has knowledge and understanding of the organisation, but that the agency have little to no understandng of the community. In such a scenario, much of the work for change is coming from the community and this is a one-sided effort. This may lead to ad hoc change; but this may cease when community members cannot sustain the effort.

Scenario 3 (S3): Is where the agency is leading the change process. This may indicate the effort is again one-sided and may be placed on the shoulders of a small number of individuals, who have knowledge of the community’s histories and cultural processes; but that the community have no knowledge of the organisation. This will produce ad hoc change whilst the service delivery personnel are engaged; but when they leave, the change may not continue and is not sustained.

Scenario 4 (S4): This is the optimum scenario and indicates that the community and service delivery agency are fully aware of one another, are engaged and have open and regular communication. This will lead to growth and sustainable change for all parties.

A question to ask in any proposed research is which of these scenarios applies to the academic, the Indigenous communities and the organisations they are working through? Understanding where agencies and Indigenous communities fit in these scenarios enables strategies to be built so that ongoing work leads to positive and sustainable practice.

Community-Led Research – when should it be done?

A key issue in relation to determining when and how community-led approaches and research should be undertaken revolves around when is CLR considered important or necessary? Often community-led options are as a result of ongoing crises in the community (see Sampson, Katrak, Rawsthorne & Howard, this volume) and the government ‘giving up’ trying to restore order or control the community situation. They then make contact with key community members and offer to allow them to take control, that is, take on board a community-led approach (Kar & Chambers, 2008; see McMahon & McKnight this volume; Sampson, Katrak, Rawsthorne & Howard, this volume). In this scenario, the ideology behind CLR is that the authority feels they have nothing to lose and they will let Indigenous peoples have a go. An example in education is a project undertaken at Cherbourg Primary School – a primarily Aboriginal school, located on an old Aboriginal Reserve in Queensland. In this case, an Indigenous teacher, Chris Sarra (2012), was given the position at the school as the principal, as the alternative was to close the school, due to the high failure rates and non-attendance of the students.

Chris Sarra turned the school around by incorporating strong educational expectations and Aboriginal protocols. The key issue here was that Chris Sarra did not use strategies that had not been discussed, written about or petitioned for, before this incident. These strategies were simply made possible when the authorities gave up and allowed the school to become community-led.

CLR has been proven to work, but depends on the combination of two key strategies:

(i) Attitudes and behaviours of facilitators – where what is required is a ‘combination of boldness, empathy, humour and fun … to enable people to confront their unpalatable realities’ (Kar & Chambers, 2008, p. 9); and

(ii) Sensitive support of institutions – where there is ‘consistent flexible support’ (Kar & Chambers, 2008, p. 9), not an ad hoc program (as highlighted in Figure 1.3) or test-like approaches, which change dependent on the particular mindset of the institution’s personnel and who are in control at any given time.

When these two strategies combine, we see sustainable practice occurring with sound achievable outcomes. As academics we need to be very clear about our role in CLR. Be aware of the purpose of the research and where the research will leave the community.

A table entitled ‘Basics: The Key Attitudes and Behaviours in Community-Led Research’, created by Kar and Chambers (2008, pp. 10–11) in their community-led projects for improving sanitation in Indian communities, provides a clear list of ways academics should and shouldn’t interact with community members they are seeking to engage with in community-led approaches for projects.

These are essential steps in creating open and ongoing communication with community groups for research and projects.

Kar and Chambers (2008) go on to discuss the sequence of steps required in ensuring a community-led approach drives research and projects. These are:

Pre-triggering: what establishes the need for any research or project to be created?

- Community selection: is this based on ongoing community crises and needs to solve or resolve a local community issue?

- Introductions and building rapport: who instigates the research or project; ensure appropriate cultural protocols are adhered to; and that interrelationships and rapport are built before any plans are created.

Triggering: who are the stakeholders involved, and what roles will be required of them for the research/project?

- Participatory profile analysis: who needs to be involved in the research/project; build a profile of stakeholders and what their role may be in the research/project.

- Ignition moment: what instigates the moment the research/project must commence and who are the stakeholders in this process?

Post-triggering: how will the research/project be carried out with clearly articulated benefits for the community?

- Action planning by the community: ensure that community stakeholders have a privileged and controlling voice in the planning of the research: what it entails, how it will be carried out, and who the key stakeholders will be. Ensure that the time frame of the work to be undertaken and when is clearly articulated, so that all stakeholders understand their roles.

Scaling up and going beyond the project: when the research or project is completed, what are future plans?

- Determine a future beyond the immediate research/project to ensure ongoing sustainability of the research/project outcomes and relationships.

Planning is the key to all research and projects; the key issue in community-led is the significance given to the stakeholders involved at the community level and the manner in which they are privileged and have control of research and projects.

Conclusion

This chapter has sought to provide an overview of who has been influential in research approaches and the impact of that research on Indigenous Australians; how research has often viewed Indigenous Australians as subjects or excluded them from how research is planned, carried out and analysed. In recognising research approaches undertaken we must acknowledge and use Indigenous protocols, ethics and methodologies of research collection to ensure Indigenous voices are privileged; and as academics we must be clear about what CLR entails, to ensure that as facilitators of research we enable improved outcomes in research that benefits Indigenous communities.

References

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (2012). Guidelines for ethical research in Australian Indigenous studies. AIATSIS: Canberra.

Australian Linguistic Association (1984). Linguistic rights of Aboriginal and Islander communities. In The Australian Linguistic Society Newsletter 84(4), October 1984.

Byrne, D. R. & Nugent, M. (2004). Mapping attachment: A spatial approach to Aboriginal post-contact heritage. Hurstville, NSW: NSW Department of Environment and Conservation.

Cowlishaw, G. (2013). Australian Aboriginal studies: The anthropologists’ accounts. Canberra: AIATSIS.

Driese, T. & Mazurski, E. (2018). Weaving knowledges. Sydney: NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs.

Federation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages (2004). FATSIL guide to community protocols for Indigenous language projects. Sydney: FATSIL.

Hart, V. G. & Whatman, S. L. (1998). Decolonising the concept of knowledge. In HERDSA: Annual International Conference, July 1998, 7–10 July 1998, Auckland, New Zealand.

Kar, K. & Chambers, R. (2008). Handbook on community-led total sanitation. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex and Plan UK.

McMahon, S. & McKnight, A. (2020). It’s right, wrong, easy and difficult: Learning how to be thoughtful and inclusive of community in research. This volume.

Mooney, J., Riley, L. & Howard-Wagner, D. (2017). Indigenous online cultural teaching and sharing: Kinship project. University of Sydney.

Moore, T., Pybus, C., Rolls, M. & Moltow, D. (2017). Australian Indigenous studies: Research and practice. Bern: Peter Lang, AG International Academic Publishers.

National Health & Medical Research Council (2003). Values and ethics: Guidelines for ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

National Health & Medical Research Council (2018). Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: Guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra.

National Library of Australia (n.d) Secret instructions given to Cook. https://bit.ly/3bnqVlo and https://www.nla.gov.au/content/secret.

NSW Board of Studies (2008). Working with Aboriginal communities. Sydney: NSW Board of Studies.

Office of Indigenous Strategy (n.d.) Aboriginal cultural protocols. Sydney: Macquarie University.

Popay, J., Escorel, S., Hernandez, M., Johnston, H., Mathieson, J. & Rispel, L. (2008). Understanding and tackling social exclusion. World Health Organisation. http://bit.ly/3sZr0S9.

Pascoe, B. (2018). Dark emu. Broome: Magabala Books.

Rigney, L-R. (2003). Indigenous Australian views on knowledge production and Indigenist research. Canberra: ANU. https://bit.ly/30sLh6d.

Riley-Mundine, L. (2007). Untapping resources for Indigenous students. In Knipe, S. (Ed.) (2007). Middle years schooling. Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Education Australia.

Sampson, D., Katrak, M., Rawsthorne, M. & Howard, A. (2020). Way more than a town hall meeting: Connecting with what people care about in community-led disaster planning. This volume.

Sarra, C. (2012). Good morning Mr Sarra. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Smith, V. (2010). Intimate strangers: Friendship, exchange and Pacific encounters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sommerville, M. (2013). Singing the coast: Writing place and identity in Australia. In Johnson, T. & Larsen, S. C. (Eds.). A deeper sense of place: Stories and journeys of Indigenous–academic collaboration. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press.

Webster, E., Hill, Y., Hall, A. & See, C. (2020). The Killer Boomerang and other lessons learnt on the journey to undertaking community-led research. This volume.

Welsh, J. & Burgess, C. (2020). Trepidation, trust, and time: Working with Aboriginal communities. This volume.

World Health Organization (2019). The social determinants of health: Social exclusion. https://bit.ly/3sZr0S9.