6

Who steers the canoe? Community-led field archaeology in Vanuatu

J.L. Flexner (2021). Who steers the canoe? Community-led field archaeology in Vanuatu. In V. Rawlings, J. Flexner & L. Riley (Eds.), Community-Led Research: Walking new pathways together. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

The notion of ‘community archaeology’ has been around since at least the 1990s, though the idea that archaeology can and should involve people from living communities has been around for much longer than that (Marshall, 2002). Definitions and actual practices vary to some degree. ‘Community’ is often implicitly framed as something well defined and cohesive, while in practice community can be amorphous, fractious, and will mean different things to different people. Relationships with community vary as well, from consultations, sometimes seen as cynical ‘tick-box’ exercises (La Salle & Hutchings, 2018), to serious, long-term collaborations aimed at building real capacity for marginalised people (e.g. Gonzalez, Kretzler & Edwards, 2018).

In the Australasian region, community archaeology has been a robust part of the discipline (Marshall, 2002, p. 214), with leading scholars coming from Australia (e.g. Greer, 2010) and New Zealand (e.g. Allen et al., 2002) particularly. Here too the idea of community-based research is not without its critics, especially when regarding developer-led commercial archaeology (Zorzin, 2014). Nonetheless, there has been significant goodwill among archaeologists to work closely with communities, particularly Indigenous communities, since at least the 1990s. In the Pacific Islands, where many archaeologists based in Australasian institutions do their work, community-oriented projects can be quite important (e.g. Crosby, 2002), though much of this potential has yet to be realised (Kawelu & Pakele, 2014).

In this chapter, I reflect on my work in Vanuatu since 2011, what it might offer in terms of our understanding of how a community-led archaeology can work, and what its limitations are. I want to challenge the notion of a ‘decolonising’ potential for community-led archaeology in light of the very real differences in power and wealth between local people, archaeologists, and the bodies that fund international research projects. Decolonising research is a concept that largely derives from Tuhiwai Smith’s (2012) critique of research and re-articulation of an Indigenous research agenda. The idea of decolonising archaeology has been proposed in the Aboriginal Australian context (e.g. Smith & Jackson, 2006), and globally there has been a more general turn towards postcolonial archaeologies (e.g. Lydon & Rizvi, 2010). However, the optimism of a decade ago is increasingly challenged as in practice the promises of postcolonial or decolonising archaeology fail to live up to the theoretical possibilities (see Schmidt & Pikirayi, 2018). What I argue here is that archaeology can’t necessarily escape its colonial past, but the knowledge we produce has a mostly unrealised decolonising potential only once that knowledge has been removed from the control of archaeologists and placed in the hands of communities.

Community-oriented or community-led?

I am going to distinguish between two types of community archaeology: community-oriented and community-led. I argue that most self-identified community archaeology is community-oriented. The archaeologist goes and lives or works within a community, however defined, and because everyone gets along and feels good about the project, it is considered a community archaeology project. This statement is not meant as a critique; it is a perfectly fine way to do archaeology. But in most cases, for a variety of reasons, the archaeologists ultimately set the agenda, albeit often with a sensitivity for community concerns and interests.

These types of relationships are particularly complicated in developer-led contract archaeology (Gnecco & Dias, 2015). Contract archaeology is the largest employer of professional archaeologists globally, originally emerging as a response to heritage legislation in wealthy countries in North America and Europe, but increasingly a global occupation (Shepherd, 2015). In many cases there is sincere will from the archaeologists to do some good by a community, particularly when working with Indigenous peoples, but the nature of developer-driven practice often places the archaeologist in a position of conflict of interest. The developer pays their salary and has certain requirements, which may or may not fit community desires or values. There can also be a tension where local communities in fact want development to go ahead, and the archaeology is perceived as a hindrance holding back a new road, building project, or industrial operation that people believe will create jobs. There is of course a larger critical discussion to be had about archaeology and its place within a capitalist order, but this is slightly beyond the scope of this chapter (Hutchings & La Salle, 2015; Zorzin, 2015).

In standard community-oriented projects, archaeologists give community some control over the archaeological process but ultimately it is the archaeological expert(s) who make the final decisions and control the design, the doing of the project, and the outputs. Community-led projects, in contrast, offer communities the ultimate decision-making power at all stages of the process. This includes the option to go back and revisit elements of the research design, and even the option to walk away from the project altogether if the community are not satisfied with how things are proceeding or if they feel the researcher is not delivering what was agreed upon. At the moment, truly community-led archaeology projects are extremely rare (Gonzalez et al., 2018 provide one example). The reasons for this include the development orientation of contract archaeology, and the ‘fast-science’, output-oriented approach to academic archaeology, which rewards results rather than the building of real relationships within a research setting (for a proposed alternative, see Cunningham & MacEachern, 2016).

In my own research in Vanuatu, I recognise elements of Community-Led Research (CLR); however, there is still much work to be done, and I am experimenting with how far a Community-led approach can be pushed within institutional limitations in current projects (see Robinson, Flexner & Miller, this volume). Cultural research was politicised in post-independence Vanuatu in a way that requires community leadership (discussed below). However, there are still very real differences in terms of wealth, access to resources, and access to information between Vanuatu and the neighbouring countries that fund research, including Australia. These differences can in some cases create a power differential between researchers and local people. That said, in my experience Vanuatu does tend to strike a reasonably good balance when giving communities the upper hand in cultural research.

Archaeological research in Vanuatu

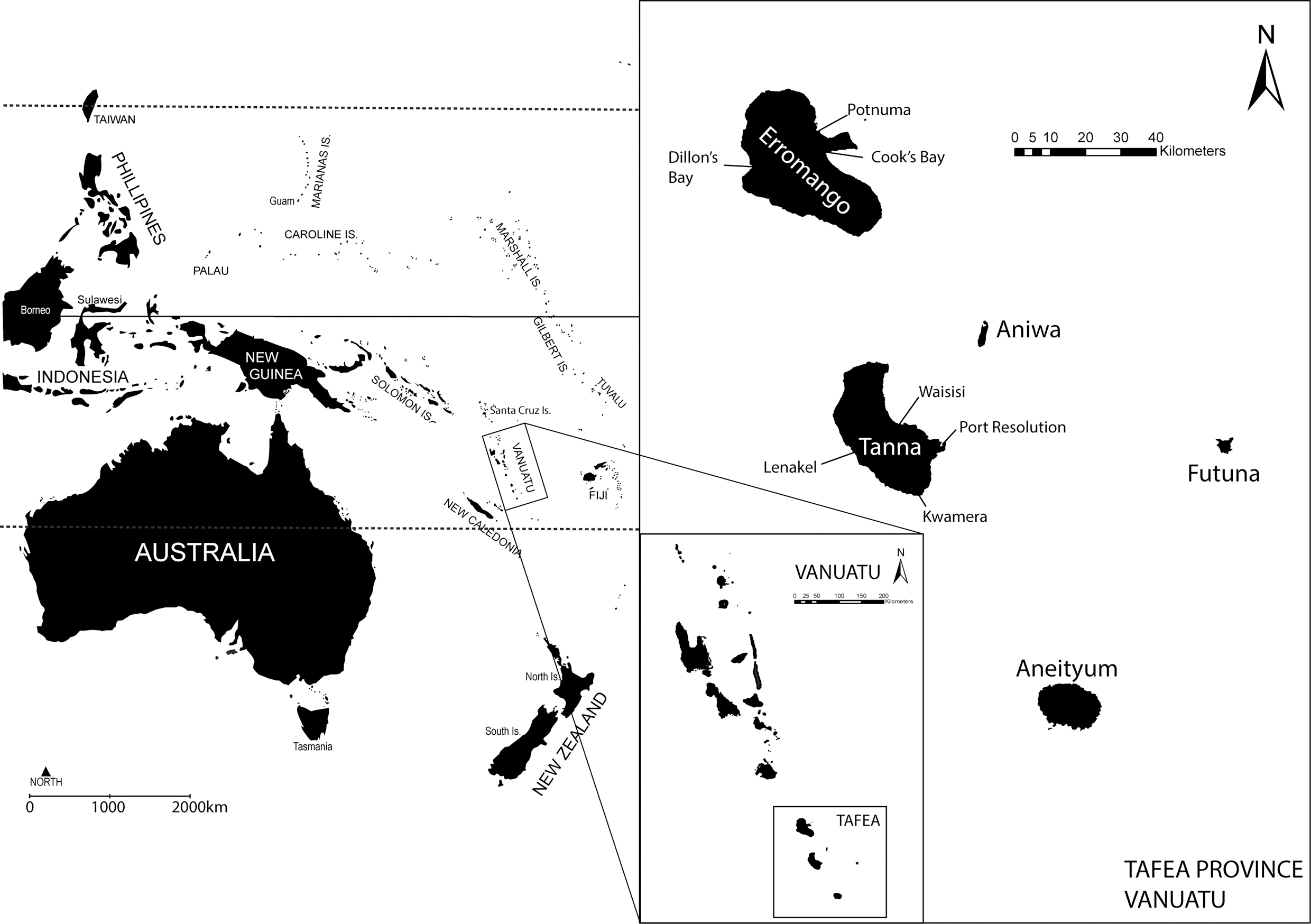

Vanuatu (Figure 6.1) is a small island nation in the western Pacific, located about 2000 km east from Cape York Peninsula in north-eastern Australia. It sits at the crossroads between the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia and Fiji, and has for 3000 years been a major hub of human settlement and interaction (Bedford 2006; Bedford & Spriggs, 2014). The archipelago’s current population of about 280,000 features some of the highest linguistic diversity in the world, with estimates ranging at 80 to 100 languages (Crowley, 2000; François, 2012), probably more before Europeans arrived beginning in the 1770s.

Figure 6.1 Map of Vanuatu and its context in the western Pacific, including detail of southern islands and locations mentioned in the text. (Flexner, adapted from Vanuatu Department of Lands basemaps)

In terms of its colonial history, Vanuatu (called the New Hebrides from 1774–1980) saw its first major incursions of missionaries and other colonisers beginning in the 1840s (Flexner, 2016; Shineberg, 1966). Formal colonial status was not established until the 1880s, when an Anglo-French naval protectorate was established, formally transformed into a ‘Condominium’ government in 1906 (Jacomb, 1914). Colonialism wrought major changes in Vanuatu, from significant demographic upheaval due to introduced disease (McArthur, 1981) to dispossession and transformation of relationships to land (Van Trease, 1987). Vanuatu achieved independence in 1980, though not before significant conflict and struggle (Jolly, 1992).

Vanuatu’s colonial and independence histories are relevant because these experiences shaped the post-independence attitude to research. The New Hebrides had a history as an anthropologists’ playground (Adams, 1987), where many researchers from overseas would come, spend time ‘studying’ local communities, and then disappear over the horizon, never to be heard from again, though of course many other anthropologists also developed deep and real personal relationships with their hosts. Nonetheless, an independent Vanuatu sought better outcomes and better relationships. Beginning shortly after independence in 1980, there was a ‘moratorium’ on cultural research, which was lifted in 1994 with the Vanuatu Kaljoral Senta (Vanuatu Cultural Centre, hereafter VKS) placed as the primary mediator between communities and outside researchers (Taylor & Thieberger, 2011).

Cultural research as well as documentary filmmaking in Vanuatu now require a special permit from VKS. Significantly, the permit’s conditions rely on the notion that a host community has a specific interest in the proposed research project, and that the project’s outcomes will benefit the community in some way. How this is defined is dependent on conversations between researcher and community, usually mediated through the national network of filwokas (fieldworkers), usually community-appointed liaisons associated with VKS. Filwokas are indispensable cultural knowledge-holders, speakers of local languages, and usually the first point of contact between communities and researcher, or vice versa.

There is a long history of community-oriented archaeological research in Vanuatu, arguably stretching back to José Garanger’s pathbreaking work in the 1960s (Garanger, 1996). The establishment of the Vanuatu Cultural and Historical Sites Survey in 1990, a few years before the lifting of the research moratorium, importantly aimed not only to document and conserve historical sites, but also to train Indigenous Ni-Vanuatu as cultural researchers to manage their own heritage. Subsequent workshops and training exercises have further developed the archaeological capabilities of various Ni-Vanuatu individuals and communities, particularly among the filwokas (see Bedford, Spriggs, Regenvanu & Yona, 2011; Willie 2019). Today archaeology in Vanuatu is to some degree community-led, although as will be explored below, the realities of differential access to resources and information maintain some degree of inequality that should prevent us feeling too comfortable about the situation.

From lecture hall to nakamal

It was in this collaborative archaeological research environment that I first encountered Vanuatu in 2011. My PhD from Berkeley (Flexner, 2010) focused on Hawai‘ian archaeology, and I had a general idea that community was important, although it was something I’d only vaguely developed in my graduate research. As a fresh-faced young researcher, I was invited by Australian academics, speaking for filwokas and jifs (chiefs) in the southern islands of Tanna and Erromango, to begin a project exploring the archaeology of mission sites dating from the 1850s onwards (Flexner, 2016). With funding from the university in the US where I was teaching at the time, I booked a plane ticket and, knowing little about what to expect, off I flew to Vanuatu. That first season was a classic misadventure, involving lost luggage, cultural misunderstanding, and linguistic confusion (Flexner, 2018), but it was an important experience in shaping my perspectives on what community-led can mean in a decolonising Pacific.

I arrived initially in the capital, Port Vila, in June 2011. After spending a few days getting oriented and organising things like local currency and a few last-minute supplies I’d forgotten to pack, I boarded the small plane to Erromango. As the crew offloaded the luggage, I was alarmed to find that my bags, including the one I had accidentally packed my mobile phone in, had not come with me. Worse, the filwoka who I was told would meet me was nowhere to be found. Thus it was with some nervousness that I watched the plane depart the small grass strip, not scheduled to return for another five days. Having been in the country only a few days, my Bislama (the local pidgin language) was non-existent. Luckily there was a self-identified ‘chief’ from Ipota, at the time the only airport on the island, who spoke enough English to figure out who I was and what I wanted. White visitors to Erromango were, and are, fairly rare, and Americans even rarer. It took a bit of explaining that I was not, in fact, a Peace Corps volunteer, and that I was there on a research permit from VKS.

Eventually, Jerry Taki, the senior filwoka for Erromango, did arrive. We used his mobile to contact colleagues in Port Vila to try to track down my bags, which did, eventually, appear a week later. That settled, as the sun began to set in Ipota, Jerry told me he wanted to do a ‘ceremony’ to welcome me to the island. As we sat on the grass just behind the airport terminal building, he got out what appeared to be a stick of some sort and started chewing. Eventually a masticated wad of fibre was spat onto a leaf. This was strained with fresh water through a cloth, which looked clean enough, into a coconut shell, and was offered to me to … drink. At this stage I basically realised I was either going to drink the shell or I wouldn’t make it in Vanuatu. So, I obliged and politely smiled after downing the greyish, metallic tasting liquid.

What Jerry had offered me was my first shell of truly traditional kava, an intoxicating beverage made from the Piper methysticum plant, which is essential to male sociality throughout Vanuatu (Brunton, 1989; Siméoni & Lebot, 2014). It is, in hindsight, quite likely that Jerry had been late to meet me at the airport because he had dug up this root from his own garden, which was several hours’ walk from Ipota. This fairly simple gesture is a classic example of establishing a relationship of reciprocity (Mauss, 1990), one which would last for many years during and beyond this particular project. It also established Jerry as the instigator of the relationship, representing the community on Erromango. In other words, the welcome involving a shell of kava, something I have subsequently experienced in nearly every village I’ve visited in the five islands of south Vanuatu, puts the outside researcher in a position of obligation to the local people from the outset.

The following day, I paid for a charter boat, the typical seven-metre fibreglass model with outboard motor used throughout Vanuatu, to take us around to the west coast of the island and the village of Williams’ Bay (formerly Dillon’s Bay, renamed after the London Missionary Society missionary who was killed at that place in 1839). On the way, we trawled with a lure behind the boat and caught a large wahoo. Once again, this was a significant catch, as upon our arrival the fish was divided up, with the chiefs (Fan lo) in Dillon’s Bay taking the best portions. We also kept a portion for ourselves which we cooked with ‘local curry’ (bush spices) and ate for lunch that day. These simple principles of reciprocity and conviviality, sharing of resources and of meals, are critical elements of community-led work in Vanuatu, as I’m sure they are in many parts of the world. They are the building blocks for developing trust and common ground, which are a foundation to doing CLR.

I had been invited to Dillon’s Bay to document the historical archaeology of John Williams, and the subsequent Presbyterian missionaries George Gordon and H. A. Robertson. As it turned out, my baggage being taken to the wrong island had been a blessing. I arrived with a basic GPS for recording site locations, a notebook and little else as my equipment was in my other bags. What this meant was that rather than launching straight into the technical aspects of my work, I spent my first five days in Dillon’s Bay simply walking around with Jerry and local chiefs and elders from the Presbyterian church (Figure 6.2). This was instrumental to my understanding of how local people perceived the landscape in Dillon’s Bay, and I used the same approach to documenting other sites in this project (Flexner, 2014). I did my best to put community perspectives as I understood them first, then considered what kinds of archaeological techniques would be appropriate to reflect and complement those perspectives. The result was ultimately probably richer and more interesting than if I had simply followed the orthodox, technical approach to archaeological survey.

Figure 6.2 Clearing a memorial enclosure near Dillon’s Bay during archaeological survey. From left to right, Jerry Taki, Manuel Naling, Malon Lovo and Thomas Poki.

Community-led or spectator sport?

A few years after my initial fieldwork trip in Vanuatu, I experienced another illustrative episode of the way CLR works in the country. By 2013, I had shifted to Australia through a postdoctoral fellowship awarded by the Australian Research Council to expand on my mission archaeology work. That year, I was in Kwamera, a remote village in the far south of Tanna Island, excavating an 1880s mission house that had been inhabited by William and Agnes Watt (Flexner, 2016, pp. 98–107). Unexpectedly, we began uncovering fragments of human bone from beneath the front step of the mission house.

In Hawai‘i, iwi kūpuna (ancestral remains) are highly sacred, and how they are handled by archaeologists is a major concern for kanaka māoli (Native Hawai‘ians), who would generally prefer that human remains simply be left to rest (Kawelu, 2007, pp. 99–111). With my previous experience in Hawai‘i, I therefore expected this would be the point where I was told by the community that I was no longer welcome. I was quite surprised then when the local people I was working with suggested the opposite. They wanted to see the bones, understand who was buried there, and how long ago. I explained that at that point, I in fact didn’t have the right equipment to excavate a burial, but could stop excavations, backfill the trench, and return the following year to investigate further.

The community assented, and in 2014 I returned, this time with Indigenous VKS archaeologist Edson Willie, who had just completed a degree in archaeology from the University of Papua New Guinea. Edson and I, prepared this time for what we would encounter, began carefully uncovering the skeleton. The only caveat the community had was that if we had to leave excavations open overnight, we should cover the bones with some dirt to prevent the ierehma (spirit) of the deceased from walking around and potentially causing harm. We did this, and over a few days we uncovered a single individual who was buried in an extended, supine position but whose bones had fairly badly deteriorated in the black beach sands. The burial turned out to be roughly 800 years old, and offers material to reflect on an interesting story about where missionaries were placed by local people when setting up the house and church (Flexner & Willie, 2015).

At one point during our excavation, one of the student volunteers took a photograph of our work in action that is a fairly typical scene in Vanuatu archaeology (Figure 6.3), though we perhaps had a bigger crowd than usual for the skeleton excavation on the church ground just outside the main village. But normally archaeology in Vanuatu is very much a public event. We hire local people to excavate with us, and often curious passers-by will stop for a few minutes or even a few hours to watch what we’re doing, ask questions, tell stories, and make small-talk. The filwokas are usually well known and respected members of the community where the work is taking place, so will have close personal connections to the people around us. Everyone from adults walking to and from gardens, to children on their way to or from school, will stop for a chat. In some cases, we even put them to work. Particularly for students, I make a point of making sure that if they’re hanging around the trench, they’re also learning something (whether they actually pay attention to me is another story).

Figure 6.3 A big crowd gathers to watch Edson Willie and me excavating, Kwamera, Tanna.

People are curious about this exotic way of digging a hole very slowly with small hand tools punctuated by many stops to record notes, take photographs, and draw. It is also an opportunity for villagers to meet people from overseas, and many who have been abroad (usually to work as farm labourers) will proudly tell you about their adventures in Australia and New Zealand. The point here is that what people take away from CLR is not necessarily what the research itself is about. In some cases, the people who stop to talk to us are not really that interested in archaeology or the past at all. Rather, it’s an opportunity to see something novel and talk to some people who they don’t normally interact with. As researchers, we should be fine with this. Not everyone is necessarily interested in the particular niche fields we find so fascinating, and we can’t force them to be. But building those kinds of personal, friendly relationships is another foundational element of CLR in Vanuatu, and in some cases, what begins as a simple friendship might develop into a more profound interest in the topic(s) at hand.

Making the most of a ruined church

As a final vignette in community-led archaeology in Vanuatu, I turn to a church building from Lenakel, on the west coast of Tanna. The church was a prefabricated kit, imported from Australia by the Presbyterian Mission and erected in 1912 (Flexner et al., 2015). This was a key site in my initial work on Tanna. The community of Lenakel were rightly concerned about the building, which had deteriorated through a combination of damage from termites and tropical rainstorms to the point that it had to be officially closed after New Year’s Eve, 2000.

Over two years, under the tutelage of Martin Jones, an expert standing buildings archaeologist from New Zealand, we documented the Lenakel church intensively, to the point that it’s probably the most well-recorded colonial building of its type in Melanesia. We prepared a Statement of Significance for the Presbyterian Church, and were in the process of figuring out how to find resources for a restoration project when Tropical Cyclone Pam ripped through Vanuatu in March 2015, featuring sustained winds of over 280 km/h. The Lenakel church was completely destroyed in this event.

I was in Vanuatu a few months later, in July 2015, and made a trip to Lenakel partly to check in with friends on Tanna to see how they were doing after the cyclone, and partly to see how the site looked after the storm. I had some trepidation about facing the local community. Would they blame me for the lack of action to restore the church before the cyclone? How could I explain that my research grant didn’t include funding for this type of activity, and that finding a funding source that would support such work was a time-consuming process? I did feel a bit guilty about not doing more on this front, but academic demands mean one can only spend time on so many projects. To my great relief, there was no such feeling among the community and I was welcomed warmly and with open arms to west Tanna as usual.

If anything, people remained optimistic that something could be done with the site. In part, this is a reflection of the intangible heritage of the place, which I’ve argued is more important than the ‘authentic’ built fabric of the old church, now largely destroyed and dispersed (Flexner et al., 2016). From a community-led perspective, I also wonder if part of the work we did added to the prestige of the site. After all, people came from all over the world to work on this particular building in Lenakel, and so it is doing its work as an important kastom place, bringing together the traditional and the modern. One of the local chiefly titles is Nikiatu, which is the name for the beam that connects the outrigger to the main canoe hull. It is, among other things, a metaphor for those who bring Tanna together with the outside world. Perhaps the church served a similar purpose in local people’s minds. That it was still getting attention as a ruin reflected the fact that the place and its stories remained important, even if the building itself was gone.

Another element of CLR is not to put too much pressure on ourselves as researchers to do everything the community might ask of us. Having largely left behind my work on the Tanna church, it is no longer up to me to decide what happens to the site going forward. In fact, it never was. Rather, the people of Lenakel can and should decide how to ‘manage’ their heritage, particularly as Tanna changes rapidly in the face of ongoing development (Flexner et al., 2018).

Can archaeology decolonise?

In southern Vanuatu, the land divisions on most islands are referred to as ‘canoes’ (Erromango lo; Tanna neteta, niko; Aneityum nelcau). One chiefly role in these spaces is to ‘steer’, to direct the people living in the territory in a way that maintains consensus and harmony. As an outsider entering such spaces, my role is to temper my interests against an understanding of what direction the community want to take, how the canoe should be steered in other words, largely negotiated through the filwokas, chiefs and elders. It is by no means a perfect system, but it offers some sense of shared power in shaping a research process.

Vanuatu, through the leadership of the VKS, provides one example of how to beneficially balance community-led interests against those of foreign researchers. Generally, communities are given the upper hand, and empowered through the filwokas to find people to work on projects that they perceive as beneficial in some way. However, I don’t want to paint too rosy a portrait of these relationships. While I’ve offered some generally positive vignettes to illustrate how things work overall, there have certainly been plenty of tense moments and complicated negotiations in my nine years working in Vanuatu’s southern islands.

One of the ongoing problems in attempting to do community-led work in Vanuatu is the fact that there are still very real differences in the level of wealth between ‘there’ and ‘here’. The Australian Research Council has, over the years, funded Vanuatu archaeology to the tune of millions of dollars, and significant amounts of this money go to paying for local room and board and hiring local workers, including the filwokas, all of whom work for a tiny fraction of what is considered minimum wage in Australia. This problem of hiring local labour has been a topic of discussion in archaeology for some time (e.g. Matsuda, 1998) and I don’t want to dwell on it too much other than for what it means for CLR. Hiring local people is appropriate for a number of reasons, but is a site of negotiation. It is also a source of tension in communities, and in my experience the best cases are those where local chiefs and families decide who is to work on the project, often selecting people to rotate so there’s a sense that the work has been shared fairly throughout the village.

This still leaves a power differential with which I am not entirely comfortable. If I’m paying people as labourers, how much will they really tell me what they do and don’t want me to do? Nonetheless, I also wouldn’t want to simply bring in groups of students to dig without having local people alongside them in the trenches, and if locals are working, they should be paid for their time. It’s an intractable problem, and as noted above, probably one of those irresolvable contradictions inherent to capitalism. I think it is telling in terms of CLR that there is nonetheless an element of reciprocal exchange to these interactions. Yes, I often find myself handing out what for local people are relatively large sums of cash at the end of a project. But on the other side are usually local goods such as woven pandanus baskets or shell necklaces, and of course a feast involving many shells of kava to close things on a happy note (Flexner, 2019).

This is still where I think we hit the limits of what is possible in terms of decolonising archaeology. Ironically, the apparent wealth differentials are to some degree a result of extractive industry during the colonial era. One period account records the equivalent of approximately £19,000,000 worth of sandalwood in contemporary currency removed from Erromango between the 1850s and the early 1900s (Robertson, 1902, p. 34). The Erromangans were paid in cheap trade goods, if at all, with most of that wealth concentrating in Australia and Britain. There is simply too much of the old colonial order in the contemporary distribution of wealth.

Then there is the production and distribution of knowledge. I sit typing on my laptop in a Sydney suburb, with near-instantaneous access through a major university library to most of the world’s academic research. While people in Vanuatu increasingly have access to the internet through mobile phones and tablets, the ability to access reliable information, and to understand the notion of research, remains highly limited. Formal education is, somewhat ironically, very expensive for many people as public education in Vanuatu requires parents to pay annual school fees. Few people complete a secondary education, an even smaller number attend university, and currently there are three Indigenous Ni-Vanuatu with any formal tertiary education for archaeology specifically.

We carry too much colonial baggage to be able to claim archaeology is a truly decolonising discipline. The discipline itself still can’t completely escape its aim of documenting and ordering past human activities and accomplishments according to systematic, rigorous standards, and this ordering is itself, arguably, a reflection of a somewhat colonial mindset. If we really want to have a decolonising archaeology, we have to let go of the information we produce and place it in the hands of the communities we work with, and even then there’s a long way to go. We can start with things like open-access publications, and offering programs in local schools (although this is complicated; Bezzerra, 2015). Ultimately, we are also going to have to start pushing against, and probably dismantling, the world order that shapes what is possible in a variety of small and probably much bigger ways, a conversation that will have to happen in far more radical ways than the small seeds of a community-led archaeology examined here.

Acknowledgements

I have so many people to thank for this research. For this particular paper I’d like to thank specifically Matthew Spriggs, who got me to Vanuatu in the first place, the late Jerry Taki, who introduced me to Erromango and was a valuable colleague and mentor, the late Jacob Kapere, an instrumental filwoka from Tanna and scholar in his own right, Samson Ieru and Robert Steven in Kwamera, and Chief Peter Marshall and Iavis Nikiatu from Lenakel.

References

Adams, R. (1987). Homo anthropologicus and Man-Tanna: Jean Guiart and the anthropological attempt to understand the Tannese. Journal of Pacific History, 22(1), pp. 3–14.

Allen, H., Johns, D., Phillips, C., Day, K., O'Brien, T., & Mutunga, N. (2002). Wahi Ngaro (the lost portion): Strengthening relationships between people and wetlands in North Taranaki, New Zealand. World Archaeology, 34(2), pp. 315–329.

Bedford, S. (2006). Pieces of the Vanuatu puzzle: Archaeology of the north, south, and centre. Canberra: ANU Press.

Bedford, S., Spriggs, M., Regenvanu, R. & Yona, S. (2011). Olfala histri we i stap andanit long graon. Archaeological training workshops in Vanuatu: A profile, the benefits, spin-offs, and extraordinary discoveries. In J. Taylor & N. Thieberger (Eds.), Working together in Vanuatu: Research histories, collaborations, projects and reflections, pp. 191–213. Canberra: ANU Press.

Bedford, S. & Spriggs, M. (2014). The archaeology of Vanuatu: 3000 years of history across islands of ash and coral. In E. Cochrane & T. Hunt (Eds.), Oxford handbook of prehistoric Oceania, pp. 1–17. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bezerra, M. (2015). At that edge: Archaeology, heritage education, and human rights in the Brazilian Amazon. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 19(4), pp. 822–831.

Brunton, Ron. (1989). The abandoned narcotic: Kava and cultural instability in Melanesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crosby, A. (2002). Archaeology and vanua development in Fiji. World Archaeology, 34(2), pp. 363–378.

Crowley, T. (2000). The language situation in Vanuatu. Current Issues in Language Planning, 1(1), pp. 47–132.

Cunningham, J. J. & MacEachern, S. (2016). Ethnoarchaeology as slow science. World Archaeology, 48(5), pp. 628–641. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2016.1260046.

Flexner, J. L. (2010). Archaeology of the recent past at Kalawao: Landscape, place, and power in a Hawai‘ian Leprosarium (doctoral dissertation). Berkely: University of California, Berkeley.

Flexner, J. L. (2014). Mapping local perspectives in the historical archaeology of Vanuatu mission landscapes. Asian Perspectives, 53(1), pp. 2–28.

Flexner, J. L. (2016). An archaeology of early christianity in Vanuatu: Kastom and religious change on Tanna and Erromango, 1839–1920. Canberra: ANU Press.

Flexner, J. L. (2018). Doing archaeology in non-state space. Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 5(2), pp. 254–259.

Flexner, J. L. (2019). ‘With the consent of the tribe’: Marking lands on Tanna and Erromango, New Hebrides. History and Anthropology. doi: 10.1080/02757206.2019.1607732.

Flexner, J. L., Jones, M. J. & Evans, P. D. (2015). ‘Because it is a holy house of God’: Buildings archaeology, globalization, and community heritage in a Tanna church. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 19(2), pp. 262–288.

Flexner, J. L., Jones, M. J. & Evans, P. D. (2016). Destruction of the 1912 Lenakel church (Tanna, Vanuatu) and thoughts for the future of the site. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 20(2), pp. 463–469. doi: 10.1007/s10761-015-0304-7.

Flexner, J. L., Lindstrom, L., Hickey, F. R. & Kapere, J. (2018). Kaio, kapwier, nepek, and nuk: Human and non-human agency, and ‘conservation’ on Tanna, Vanuatu. In B. Verschuuren & S. Brown (Eds.), Cultural and spiritual significance of nature in protected areas: Governance, management and policy, pp. 253–265. London: Routledge.

Flexner, J. L. & Willie, E. (2015). Under the mission steps: An 800 year-old human burial from south Tanna, Vanuatu. Journal of Pacific Archaeology, 6(2), pp. 49–55.

François, A. (2012). The dynamics of linguistic diversity: Egalitarian multilingualism and power imbalance among northern Vanuatu languages. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 214, pp. 85–110.

Garanger, J. (1996). Tongoa, Mangaasi and Retoka: History of a prehistory. In J. Bonnemaison, K. Huffman, C. Kaufmann & D. Tryon (Eds.), Arts of Vanuatu, pp. 66–73. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Gnecco, C. & Dias, A. S. (2015). On contract archaeology. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 19(4), pp. 687–698.

Gonzalez, S. L., Kretzler, I. & Edwards, B. (2018). Imagining Indigenous and archaeological futures: Building capacity with the Federated Tribes of Grande Ronde. Archaeologies, 14(1), pp. 85–114.

Greer, S. (2010). Heritage and empowerment: Community-based Indigenous cultural heritage in northern Australia. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 16(1–2), pp. 45–58.

Hutchings, R. & La Salle, M. (2015). Archaeology as disaster capitalism. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 19(4), pp. 699–720.

Jacomb, E. (1914). France and England in the New Hebrides. Melbourne: George Robertson.

Jolly, M. (1992). Custom and the way of the land: Past and present in Vanuatu and Fiji. Oceania, 62(4), pp. 330–354.

Kawelu, K. L. (2007). A sociopolitical history of Hawai‘ian archaeology: Kuleana and commitment (doctoral dissertation). Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley.

Kawelu, K. L, & Pakele, D. (2014). Community-based research: The next step in Hawai‘ian archaeology. Journal of Pacific Archaeology, 5(2), pp. 62–71.

La Salle, M. & Hutchings, R. (2018). ‘What could be more reasonable?’ Collaboration in colonial contexts. In A. M. Labrador & N. A. Silberman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public erhitage theory and practice, pp. 223-¬37. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lydon, J. & Rizvi, U. (Eds.) (2010). Handbook of postcolonial archaeology. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Matsuda, D. (1998). The ethics of archaeology, subsistence digging, and artifact looting in Latin America: Point muted counterpoint. International Journal of Cultural Property, 7(1), pp. 87–97.

Marshall, Y. (2002). What is community archaeology? World Archaeology, 34(2), pp. 211–219.

Mauss, M. (1990). The gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies (W. D. Halls, Trans.). London: Routledge.

McArthur, N. (1981). New Hebrides population 1840–1967: A re-interpretation. Noumea: South Pacific Commission.

Robertson, H. A. (1902). Erromanga: The martyr isle. Toronto: The Westminster Company.

Schmidt, P. R. & Pikirayi, I. (2018). Will historical archaeology escape its Western prejudices to become relevant to Africa? Archaeologies, 14(3), pp. 443–471. doi: 10.1007/s11759–018–9342–1.

Shepherd, N. (2015). Contract archaeology in South Africa: Traveling theory, local memory, and global designs. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 19(4), pp. 748–763.

Shineberg, D. (1966). The sandalwood trade in Melanesian economics, 1841–1865. Journal of Pacific History, 1(1), pp. 129–146.

Siméoni, P & Lebot, V. (2014). Buveurs de kava. Port Vila: Éditions Géo-Consulte.

Smith, C. & Jackson, G. (2006). Decolonizing Indigenous archaeology: Developments from Down Under. In American Indian Quarterly, 30(3–4), pp. 311–349.

Taylor, J. & Thieberger, N. (Eds.) (2011). Working together in Vanuatu: Research histories, collaborations, projects and reflections. Canberra: ANU Press.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). New York: Zed Books.

Van Trease, H. (1987). The politics of land in Vanuatu. Suva: University of the South Pacific Press.

Willie, E. (2019). A Melanesian view of archaeology in Vanuatu. In M. Leclerc & J. Flexner (Eds.), Archaeologies of Island Melanesia: Current approaches to landscapes, exchange, and practice. pp. 211–214. Canberra: ANU Press.

Zorzin, N. (2014). Heritage management and Aboriginal Australians: Relations in a global, neoliberal economy – a contemporary case study from Victoria. Archaeologies, 10(2), pp. 132–167.

Zorzin, N. (2015). Archaeology and capitalism: Successful relationship or economic and ethical alienation? In C. Gnecco & D. Lippert (Eds.), Ethics and archaeological praxis, pp. 115–139. New York: Springer.