I

The Lineaments of Sacrifice

1. Introduction

One of the elementary forms of the religious life which Émile Durkheim did not analyse completely in his classical study of the Aborigines is that of sacrifice. Its lineaments show plainly through the cultus of the bullroarer among the north-western tribes.

The authorities whom Durkheim consulted were not familiar with this region and in any case were not always of the best. Their information was very uneven and much of it had been collected under the influence of ideas which now seem mistaken. Moreover, there are very considerable institutional differences between Central Australia and North Australia, of which he could have known little.

In this article I shall show that there are some very striking resemblances between the form of a bullroarer ceremony and the form of sacrificial ceremonies in more developed religion. The resemblances are not simply those of analogy. The two types are homomorphic and in a deeper sense, which I do not explore, may be isomorphic as well. To reveal the resemblances one must abstract more severely than is perhaps the rule, and also with reference to somewhat different conceptions from those which Durkheim used. The plan I follow is to isolate the operations which the Aboriginal celebrants perform on things, including persons, in the ceremony and to compare the operations, in a general way, with those which are most plain in sacrifice.

Inquiries which I have made into the cultus that surrounds the bullroarer among the Aboriginal peoples of the north-western part of the Northern Territory lead me to believe that what I have found to be the case there may equally well have been so in other regions. If 66the contention can be substantiated then an extensive re-study of the religious institutions of the Aborigines might well be made. A tradition of study which is of course a good deal older than Durkheim, but which was given by him a formulation of immense influence, would then invite a reconsideration.

It is possible to study the structure of sacrifice as a type of activity from two points of view. First, one may try to find the parts or elements which are organised into a system of activity conceived in terms of human duties: in short, as a system of role-enactments from positions in a social structure. Second, one may try to find the parts or elements conceived as human operations on things, including persons. The two viewpoints are of course connected but may be kept analytically distinct. It is from the second viewpoint that this article is written. The first is a more ‘sociological’ point of view: an inquiry connected closely with a formed theory about the general character of human society. The second is more akin, at least to begin with, to a natural philosophy or natural history of a type of human conduct.

At the level of natural history the main problems are those of clear description and fruitful classification. In Section 2 I have tried to give as compact a description as possible of the bullroarer ceremony known as Karwadi (its secret name) or Punj (its public name) among the Murinbata people. But description and classification are not really separable, and classification is or is not fruitful for a theoretical intention. The description offered in Section 2 has therefore been made up with the idea of isolating, as clearly as possible; the operations on things, including persons, which may be seen to take place in the ceremonies, or which the Aborigines say take place. One discovery comes very quickly: things are done—i.e. operations are carried out—which the Aborigines perceive only dimly, if at all, since they can offer no explanation of any kind as to the intention of the acts. In such circumstances there seem to be only two legitimate courses: to give a just-so account of what occurs, or to compare the facts with some well-known or at least better-known model of human conduct to which analytical attention has been given. It is obviously absurd to try to relate what is not yet classified 67to a total system of life—say, to the ‘culture’ or ‘social structure’ of the Murinbata—for part of that total system is the very conduct to which not even a good name can yet be given. It was in the search for a well-known or better-known model that, after a good deal of experiment, I found the model of sacrificial conduct most suitable.

Now, the Karwadi ceremonies are very clearly initiations, and the Aborigines themselves describe them as such, though in their own words. But the idea of initiation belongs to a family of conceptions by which I do not wish to be limited. It has to do with the socialisation of persons, and while that is certainly a true description of Karwadi, the ceremony is not only an initiation. It also seemed to me to make for much difficulty in dealing with those features of the ceremony of cryptic or implicit intention. The Aborigines say that the intent of Karwadi is to make the young men ‘understand’. My problem lay with the features which the instructors themselves did not understand, and thus could not teach. I found that the type of conduct which best fitted all the features were that of sacrificial activity.

When the institutions of sacrifice, bloody or unbloody, are examined the empirical elements may be described as follows. (a) Something of positive value, but of such a substance and nature that it is judged inherently acceptable to its receiver, a spiritual personage, is set aside to an end beyond the common ends of life in such a way that one may speak of its sacralisation or consecration to that end. Something, that is, is made sacred by men. (b) The sacrifice, the thing to be sacrificed, is offered direct or after symbolistical activities have been carried out in such a way that the substance but not the nature of the sacrifice is transformed. One may speak of this as the immolation or destruction, or both, of the sacrificial object. (c) The sacrifice, having been received, or being supposed to have been received, is returned to the offerers with its nature now transformed, and (d) as yield or fruit of sacrifice it is then shared between those who sustained the loss of the sacrificial object. That loss has been requited by a gain, but of an unlike kind, the margin of gain being a motive of the total act.68

Such seems to be the kind of core around which the institutions of sacrifice arise, cloaking the core with a rich covering of metaphor, symbolism and metaphysical interpretation. The spiritual insights and æsthetic capacities of impassioned human natures then glorify the cloak. But it is with the core-elements, the basic operations, that I am concerned. The setting aside, the offering, the return, and the sharing are all in some sense the observable acts of actual persons. If these can be found in that order within a well-unified total activity, and if to them can be added an intelligible account of some kind of transformation which is conceived to occur, then a not unpersuasive correspondence has been shown with what is ordinarily called ‘sacrifice’. But the extreme unsuitability of that word and its idea should be clear. What it denotes is a gainful transaction between men and their divinities. The word ‘sacrifice’ mainly denotes what men lose and but vaguely connotes what they gain, and in so doing it puts men’s conduct in a better light in their own eyes. But that is perhaps only Gresham’s Law at work in the field of connotations.

It is my contention that the Karwadi ceremony conforms generically to the operational character of sacrifice as I have sketched it. I do not maintain that there is an exact congruence, but a likeness which cannot be dismissed out of hand and can in fact be shown to be homologous. The fundamental operations, while undoubtedly there, are caught up as a core within a very different cover, and the pattern woven into the cover is an unaccustomed one. Nevertheless, there is an homology.

The Karwadi ceremony may be described as a liturgical transaction, within a totemic idiom of symbolism, between men and a spiritual being on whom they conceive themselves to be dependent. The motive of gain is the continuation of a plan of life, given once-for-all in The Dreaming, but in continuous danger of corruption by those who in the course of nature must carry it on. I put this forward as an irresistible interpretation of the symbolism which is enacted day by day in the ceremony. It is this which the older Aborigines try to make youth understand.

The facts of the ceremony are dense with meanings. In this article I can make only a general approach to some of them. The facts are 69objective enough but they have to be constructed in a certain fashion in order to be understood. Part of the article is therefore given over to the question of the arrangement of the facts for interpretation.

2. The Ceremony of Punj or Karwadi

The Karwadi ceremony is extremely sacred and secret. It centres on the showing and presentation of bullroarers to young men who have been circumcised some years before. The bullroarers (ŋawuru) have the higher degree of sacredness which we may call sacrosanctity. The word Karwadi is the secret name of a provenant spirit also described as The Mother of All or as The Old Woman. The doctrine about her is neither clear nor well-evolved, but the attitude towards her may well be called one of holy dread. She is thought to exercise a rather frightening care of men. The bullroarer is her emblem; the sound it makes when swung is the sign of her real presence; and the emblem is at the same time a vehicle on which complex symbolical conceptions of her are projected.

Ceremonies of the kind are well known in the Australian literature. Some of them have been referred to as fertility cults, but I prefer to describe them as cults of mystery. There is some warrant for such a description in the way in which the Aborigines themselves speak of them: as things they do not really understand but believe in deeply. The Aboriginal doctrine may be summed up in two statements which are accepted as great truths: in the beginning of things, life and death, and all things connected with them, took on the characters they now have because of marvellous events which took place once-for-all; living men should, indeed must, commemorate those events, and keep in touch with the consequences, by acts to signify and symbolise what happened and, somehow, keeps on happening. By such means men ‘follow up The Dreaming’ through a repeated memorial of it.

Each celebration of the ceremony, which used to occur annually, took from one to two months to complete, depending on the will of the 70ritual leader (kirman), on the number of candidates for admission to the secrets, and on a range of circumstances of a practical kind. There were both secret and public activities. In those which were secret there were due parts allotted to the ritual leader, to senior assistants, to a chorus of singers and instrumentalists, to a body of dancers and actors, and to the initiates. Much the same parts were observed in the public or external activities, but then the women and children—rigidly excluded from the secret phases on pain of the most severe sanctions—were given the somewhat negative duties of an audience.

It was customary for all clans over a large neighbourhood to attend each Punj, and thus members of both patrilineal moieties. However, it would not be accurate to speak of ‘tribal’ gatherings for, in a region of many small tribes, Punj might be celebrated by adjacent clans speaking distinct languages. Visitors from distant clans were frequent and welcome. But the two moieties were always represented, members of each having duties towards the other. Unless both moieties were present activities absolutely necessary to Punj could not be carried out.

The proceedings had a well-standardised form which I shall now set out. The only terms which need be explained are the following:

ŋudanu: the public name of the ceremonial ground. There is no secret name.

Kirman: the ritual leader. The word is of Djamindjuŋ origin but has been taken over by the Murinbata.

Merkenu: the original Murinbata term for the ritual leader.

Wanangal: wise men with mystical and healing powers who were looked on by their enemies as warlocks.

Da mambana: a hidden place near ŋudanu where initiates were secreted.

Kadu Punj: men who have been fully initiated.

Mada ŋanaŋur: the centre of a formally-arranged camp, which has a circular or horse-shoe shape.

The following account may be understood as (a) a narrative of things taking place in the order indicated, (b) my own division of 71them into phases which are actually observable and, where indicated, recognised or named by the Aborigines themselves, and (c) a minimum of explanatory comment.

1. A few years after circumcision when youths are—in the eyes of mature men—egotistical and refractory because they do not yet understand the restraints of adult life, and do not listen to the prudent counsel of age, they are asked to submit themselves to the disciplines of Punj and to learn its secrets. No force is used as at circumcision and pre-pubertal initiation. The youths are offered a discipline which is at the same time a privilege and a means of acquiring status. But acceptance of the discipline is a virtual necessity, for there is a background of mystical as well as human threat.

Secret discussions take place between the older men, including the ritual leaders, and the father of any youth of appropriate age. With parental consent, an older man, usually a classificatory father, having asked the youths if they wish to come, takes them to ŋudanu on an afternoon of secret appointment. Here they find all the adult men, known as kadu punj (lit. ‘persons’, ‘secret, forbidden, dangerous affairs’) already assembled. The youths are gathered together into a tight circle of men who sit, facing inward, while a secret song is sung. The song, repeated many times until sundown, closes with an exclamatory cry—Karwadi, yoi! It is the first occasion on which the youths have heard the secret name of The Mother of All. The yoi! is an expletive which is untranslatable. It seems to have the character of salutation, perhaps invocation.

At sundown the men and youths return to the main camp which, because of the presence of many clans, takes a formal arrangement as a huge circle of nuclear families divided by fires. The youths are placed within the circle in a position known as mada ŋanaŋur. They are not permitted to speak to their patrikin or matrikin, and are required to act quietly and modestly. They eat by themselves, and are handed their needs by old Kadu Punj.

When the morning star appears, they are wakened noiselessly by their escort, and are led to ŋudanu as dawn is breaking. From now on 72until the Karwadi ceremony is completed they are not spoken to or if at all avoidable even seen by anyone disbarred from ŋudanu.

2. The proceedings now assume a somewhat different form. The singing starts as soon as all are assembled but a custom known as Tjirmumuk goes on at the same time. It is a kind of horseplay between the moieties or, rather, between individuals in them. Men who stand to each other as cross-cousins, wife’s brothers, wife’s fathers, and mother’s brothers, push and jostle one another, snatch away small personal possessions, pluck at each others’ genitals, and in laughing voice shout things which would ordinarily be obscene, embarrassing, and hurtful.1 The custom is akin to but not the same as murin tjiwititj (lit. ‘words’, ‘teasing’), a joking relationship which is a well-marked feature of the regional culture. The initiates watch but do not take part.

When everyone tires of Tjirmumuk the men gather the youths within their circle and, without further interruption, sing the song of yesterday. At about mid-afternoon a pretext is made that food is needed and the initiates’ escort takes them away to look for it. When ŋudanu is out of eyeshot but within hailing distance he commands them to wait. He tells them that they are now at da mambana, a hidden and secret place to which they are to be restricted until told to leave.

From this time on their personal names are not used. Anyone who speaks to or about them calls them ku were (lit. ‘flesh’, ‘wild dog’). Any flesh which is ku cannot be that of persons or kadu. The youths are not only made nameless but are symbolically no longer human either. More, their personal ornaments are taken from them, and they are required to be naked. All the external marks or signs of social humanity are thus taken away.

3. Meanwhile at ŋudanu the initiated men are preparing the next phase of the ceremony.

73The youths have been told that they will be swallowed alive by Karwadi and then vomited up. As they wait they are told nothing of what is actually in store for them. At a signal from ŋudanu, when all is ready, the escort orders them to stand, to form a line with hands clasped behind their backs, to look fixedly at the ground with heads bent, and to follow him. At least outwardly humbled and often intensely frightened, they make their way to the company of Kadu Punj.

Here they find all the initiated men crouched in a circular excavation in the ground. The men, barely recognisable under their cosmetic ochres and bodily decorations of feathers, down and fire-dried leaves, form a close cluster, all facing inwards. They alternately bend until their heads touch—each man being upon his knees—and then sit erect to quiver their shoulders in a quick rhythmic unison. When they bend they make minute restless movements, giving out all the while a low murmurous hum. When they rise the violence of their movements shakes off a small cloud of dried ochre and fragments of their decorations. The youths are taken into the centre of the circle, told to kneel, and to imitate the actions of the others.

This is the mime of the blowfly, with which the proceedings start every day, for the whole duration of the celebration, after the custom of Tjirmumuk has been observed. The esoteric symbolism is not explained to the initiates, for no one seems able to interpret it. All that is known, or is now discoverable, is that the proceedings must start every day with Karaŋuk, the mime of the blowfly, which goes to rotting flesh.

The singing of a song has been carried on meanwhile by a small group of singers, who also use tapping-sticks. When the mime has been repeated several times the singing stops abruptly. The circle breaks up.

4. The escort commands the youths to stand up in front of men—in relationship their naŋgun or potential wives’ brothers—who have containers of blood. As yet the initiates do not know that the blood has been drawn by right and duty from their naŋgun. They are allowed to suppose that it is the blood of The Mother. The naŋgun smear them from head to foot with the blood: eyes, ears, nostrils, lips and nose are 74all liberally covered, but no special attention is paid to any organ or region except, perhaps, the head.

While this is done the assembled men break into a rhythmic chorus of sound, somewhat reminiscent of birdsong and animal noise. As soon as the blood has been applied fully the youths are told to stand in the heat and smoke of a fire until they are dry. The singing is resumed and goes on for some time.

The sun now being near the horizon, the whole assembly returns with loud cries to the main camp. The naked, blood-caked initiates are kept at a distance, where they cannot see or be seen, while the initiated men leap over the heads of people at the circle of fires and, in the centre, once again act out the custom of Tjirmumuk. On this occasion all the former scenes of horseplay are repeated but are dominated by the snatching of food from the classes of affines already mentioned. The aim is to take their food, gobble it with animalian sounds and gestures, and to prevent them if possible from doing the same. The noise and turbulence are extreme, but good-fellowship is nevertheless in evidence, and the bystanders laugh heartily throughout.

The camp settles down eventually. Later at night when the women and children are asleep or at least pretend to be, the escort brings the initiates to their position in the centre of the circle. The initiated men surround them in a cluster and sing over them for some time. With the morning star they are again led to ŋudanu.

5. The proceedings come to a climax of tension on this, the third day of the celebration.

Everything follows the pattern of the second day until the time of the anointing with blood. As this starts men in hiding nearby begin to sound bullroarers. The chorus of cries is maintained and, as the roar comes ever nearer, many of the older men, with shouts of well-simulated fear, cry ‘Karwadi! Karwadi! The Old Woman is calling’.2

75The secret of the supposed voice of Karwadi is made known when the men with the bullroarers spring suddenly to view. The youths then learn also the true source of the blood. At this point the naŋgun come forward, each with a new-made bullroarer as a gift of right and duty. Each man rubs a bullroarer on the breast and across the loins of the initiate marked with his, the gift-giver’s, blood and then thrusts it between the youth’s thighs so that it stands up like an erect penis.

6. The tension over, the character of the celebration undergoes a certain alteration. The disciplines are not relaxed in any way; the youths are still ku were; they stay naked and unadorned and nameless; they go apart each day while the preparations for mime and dance are made; at night they wait outside the main camp until Tjirmumuk is over; they are escorted in to be sung over and, unspoken to by anyone but their escort, to sleep unwashed and caked with the blood of many anointings, and to leave again before the camp stirs. But now no attempts are made to put them in fear. They are treated rather more as equal fellows within an accepted restraint—and perhaps a mystery—of life. When they go to da mambana they take with them their bullroarers to hold across their loins while they wait for the summons to return.

Each day the opening Tjirmumuk and the mime of the blowfly are repeated, but are followed by a long series of totemistic mime-dances which have an invariant order. The atmosphere of fear and mystery gives way to one of joyousness in which dancers, singers and painters seem almost to vie with one another for an æsthetic triumph.

7. When the time comes for the ceremony to come to an end—the decision is the kirman’s—the penultimate day is marked by a very wild demonstration of Tjirmumuk at ŋudanu and a dance of notable beauty. Again at the main camp the Tjirmumuk reaches an unusual vigour.

Early next morning the youths are taken a short distance away, not to ŋudanu itself, but to a place which is still considered da mambana. There they are blooded and, when they are dry, are given each (again by naŋgun) a forehead band, a hairbelt, a necklace and a genital covering. At this point they are judged to be no longer ku were but yuŋuana.76

I have not found it possible to translate the term yuŋuana or even to decide as to its morphemes. It is used in direct address and also as a status-title, equivalent to and in many circumstances interchangeable with Kadu Punj. It is an absolute signification of mature male status, and is used of and about initiated men until they are of middle age.3

At the main camp, which is known in this context as mununuk (which connotes ‘waiting, with gifts prepared’), the female kin and affines of the youths form an arcuate, seated cluster. The initiated men stand in two lines (one for each patrilineal moiety), with backs turned to mununuk. An old man stands at the end of each line farthest from the women and screens the scene with leafy bushes. The youths are ushered towards the old men who, on a signal, throw the leaves to one side. The lined men stand with legs apart and the youths, on hands and knees, crawl towards mununuk between the legs of the opposite moiety. Thus humbled, they make their way to their mothers: the conception that it is to the mothers they are going is explicit. As each youth emerges he sits momentarily in front of his mother, with his back to her, but not touching or touched by her, while all the women wail and lacerate their heads to draw blood. As soon as each yuŋuana has done so they return together between the legs of the immobile men and, when all have emerged at the other ends of the lines, all men rush together with loud shouts to da mambana.

No word has passed between the youths and any females since before Punj began, and none may pass for at least a week from the day of first return. The yuŋuana continue to stay outside the camp by day and to enter late at night, less escorted now than accompanied by older men. They sleep under the discipline of elders and between a stylised arrangement of fires.

77When a week has elapsed they are taken to bathe for the first time since Punj began. The last traces of blood are removed, and they are then brightly adorned with cosmetic ochres and charcoal according to a traditional design in which representations of the bullroarer are incorporated, but the import of this motif is (or is said to be) unknown to the women.

Thus marked by the insignia of their new state and position of life they return to the main camp. From now on they are free of it at all times except that they must stay only in their central place, and may not go near their mothers’ fires. They may hunt where they will but must not visit other encampments. On their return from bathing, food and comforts are given them—with some show of formality, and with an exchange of set phrases—by their own and their classificatory parents.

After a lapse of two years they are judged ready to marry, but in the meantime have been able to gain experience of sexual intercourse by being allowed to avail themselves of the wives of older clan brothers.

I used earlier of this ceremony the phrase ‘dense with meanings’, and I do not imagine that many will dissent from its truth. There are thus very many aspects under any of which the facts might be raised for study. After I had worked methodically through a number of these, the question of the interpretation of the symbolistical activities, which seemed to me to have been left far too tacit but at the same time to have been drawn upon in a sidelong way, became unavoidable. It seemed to me possible and desirable to reverse the emphasis: that is, to allow the aspects of social structure, function and organisation, as they are ordinarily understood, to remain tacit, and to concentrate on the aspect of operations in the sense already given. The conceptions needed in this approach are dealt with later.

The construction which may then be put on the Karwadi ceremony is as follows.

The Aborigines conceive existence and being to be mysteries. The ancestors evidently understood them, but living men do not. Nevertheless, the mysteries are veritable, but men have only such information about them as the ancestors handed down in the tradition. 78Part of the tradition concerns how things came to be as they are, and part concerns what living men must do to control a life so constituted.

In Aboriginal eyes all being, animal and human, corporeal and spiritual, has some sort of unity, but it is a unity of opposites and antitheses. At almost every point men’s lives are in touch with this fact. There are both visible and invisible things of power. The invisible things, not less real or less powerful for their invisibility, continually irrupt into the familiar reality of life. At the same time men’s this-worldly life is always at risk of disruption by the things men do in the ordinary course of living. Similar things were done by the ancestors with whom there is an unbroken continuity.

The continuity is historical, essential, substantial, and moral. These hills and waters of these names were made by this ancestor. These children were born through the action of spirits placed in the waters by that ancestor. The physical bodies of these men and these birds and animals have some kind of substantial identity which is timelessly true of all members of a totemic class constituted by events mentioned in the tradition. The relevance which one thing bears to another was thus instituted and made known. The plan of life constituted in this way has been maintained over time. Its continued maintenance is the guarantee of a social life in which relevances are understood, that is, of a moral order. The highest good of living men lies in the perpetuation of what has been found to be the guarantee.

The ancestors taught, and fathers from time out of mind have instructed their sons, that certain actions of living are to be carried out in certain ways. Among them are the acts or operations towards the invisible spiritual powers or personages on whom men depend and with whom they are genetically linked. The occasions of such operations arise when youth, because it possesses a nature continuous with that of the first men, is mindful to rebel against the moral system which the first men instituted, though why they did so is the mystery which the Aborigines say they believe but do not understand.

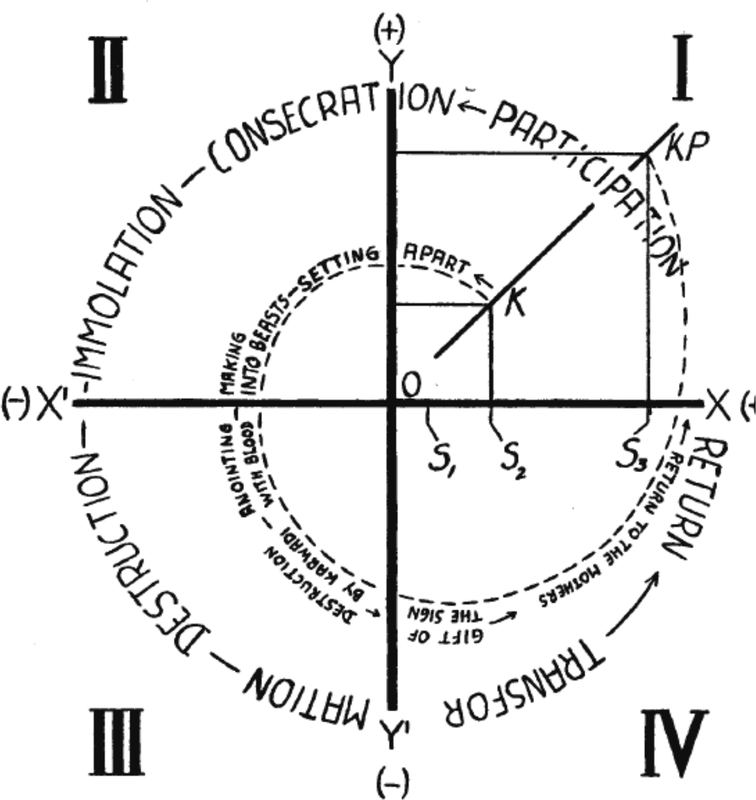

The metaphysic of life which is thus enacted is far from contemptible, and needs only words to evoke the meanings beneath the symbolisms. 79The subject will be treated separately in a later article. The immediate problem is to present for interpretation, material which is intrinsically symbolical without mutilating it in the process. I have tried to do so in as neutral a way as I can devise by the use of a diagram (Fig. 1) with explanatory notes. The imagery is geometric but in many ways this seems an advantage.

The conventions of the figure are given in the accompanying notes, but one or two further comments may be made.

The four quadrants are logical divisions of the systems of coordinates and conceptual divisions of the operations, which are all—except for one, the fourth—actual happenings that may be seen. What results is an outline sketch of a model after reality, the reality being drastically simplified.

A time-sequence, a process or task which is assumed and completed, is transposed into a spatial sequence. The principal feature is the path or course of operations which it traces. Along this path older men who have authority to do so move young men from one locus and status to another.

The empirical study, the narrative, shows that certain constituent features of locus and status are changed by the operations in what seems an orderly way. The orderliness reveals the rationale of the operations, which are in a serial or end-to-end relation, a continuous purposive connection. The diagram, it is hoped, condenses the orderliness in such a way that the rationale is made more clear. The broad comparison with the elements of sacrifice is not a theory but an arrangement in the development of a theory.

Now, it will be noted that in the narrative there are eight sections, each representing a phase of the total ceremony. Only six operations are listed. This may seem to some an unhappy discrepancy. There is a very real difficulty on which I should like to comment.

In dealing with such a mass of particulars it is not easy to decide what to include or exclude. I do not think there is any significance in the figures eight and six. Evidently it is not possible to make the number of phases less than eight, and I would not contend a view that my own 80material shows that there are more than eight. That number seems to me a convenient division of the temporal sequence. I would concede, too, that there are probably many more than six operations. Those listed struck me as central and decisive. The Aborigines have an explicit formulation of all of them. As far as possible I have allowed myself to be guided by their conception. But consider the following problem.

After being made nameless and naked, and thus constituted as ‘wild flesh’, the youths are taken to the place where The Mother is said to manifest herself. They have a lively dread that they will actually be swallowed and vomited.4 Now, when those with power force the powerless to go near a superior being, it is—at least in psycho-social terms—the making of a kind of offer. Is one then justified in constructing the facts to the shape of a precious offering? I have no evidence that any such idea is present to the conscious minds of the Aborigines and, for my own part, would say that the construction is quite unjustified. But the same issue arises in half a dozen other parts of the ceremony. I think the point is that we are dealing with a deposit or stock of intuitions only in part revealed by external acts and formed ideas. And of that part which is drawn upon a still smaller part is made explicit. I have tried to cling to the operations which are sharply formulated by the Aborigines themselves, but it is not possible to watch the ceremony without becoming aware of the loom of others. The phases and operations as I represent them are thus not congruent or equalised and, in my understanding, do not have to be.

81

Figure 1. A Comparison of Punj with Sacrifice

Fig. 1 is an attempt to use visual means to compare the Punj ceremony with the operational structure of sacrifice, no particular sacrifice or tradition being specified.

The Punj ceremony is reduced by severe abstraction to two features: (a) a prominent sequence of acts or operations, and (b) a class of external signs exhibited by initiates before, during, and after the ceremony. The acts and the signs are real or objective features in phenomenal association. The invariance, or apparent invariance, of the association suggests a functional 82interdependence. The use of coordinate systems is thus justified. To use more than two-dimensional coordinate systems is impracticable at present.

From general knowledge it is known that the external signs signify status, and that one of the primary objects of the ceremony is the initiation of youths into a higher status. The coordinates allow us to study, at least with a certain visual clarity, the sign-variation which takes place when transitive operations are set in course with the object of moving youths to a higher social status. We may think of status as a locus in a system of life with associated powers, privileges, duties and a given magnitude of social value. The figure, if logically constructed from clear concepts, should also allow us to look for types of facts which otherwise may not suggest themselves, and to be sharply aware of the need of true connectivity between facts and concepts.

In Fig. 1 the OX axis is used to mark off imaginary positions to each of which corresponds one status-degree and one only. OX is thus a status-scale, reading from O to X. Any point between O and X corresponds to a positive status. The three positions marked S1, S2, S3 correspond in that order to the status achieved at pre-pubertal, pubertal and Punj initiation. The facts of Punj show that the Aborigines conceive of negative status, though their only formulation is symbolical. OX is therefore extended to X´. The hypothetic scale of negative status thus reads from O to X´, in the direction opposite to the positive scale. No negative positions are marked on OX´ in the figure since they are unnecessary for my purpose, but it is possible to do so with warranty of fact.

The OY axis is used to mark off positions to each of which corresponds a given cluster of external signs of status. OY is thus a sign-scale, such that all the Aboriginal world knows immediately, by seeing or otherwise apprehending such a cluster that it signifies a man of a given status and of no other status. In order not to overcrowd the diagram I have not made any entries on OY. The text, I hope, will have made their character sufficiently clear. OY is extended to OY´ in order to provide for the fact of negative signs, so that its hypothetical scale reads from O to Y´. The negative scale is left empty for the same reason, and with the same rider, as in OX´.

There are thus four quadrants (I, II, III, IV) of the plane of the figure. Any position in any of the quadrants can be given sets of coordinates within the postulates used, and each set will differ from every other set, and have one of four sets of characteristics: in I (+ +), in II (– +), in III (– –) and in IV (+ –). The two points K and KP in quadrant I denote the locus in the Murinbata system of life (to the extent to which status and signs of status characterise 83it) of circumcised boys and of men initiated into Punj. The coordinates of each locus or position, made in the usual way by ordinate and abscissa in each case, in part define each locus and in part describe it.

The dotted line drawn anti-clockwise from K to KP is the continuous course of acts or operations, indicated by the script, in the actual order in which they occur, but here somewhat arbitrarily named. To move, within the conventions of the figure, from K to KP, and to pass through all the other quadrants, implies logically certain correlated changes of sign and status. Any utility the figure has rests on the correspondence which can be shown to exist between such logical requirements and empirical changes which occur in the course of the ceremony. It is my impression that there is a high correspondence.

I have found the coordinate-type of arrangement of much use in field-situations when, sometimes from over-familiarity with certain facts, and sometimes from their novelty, the puzzles arise which are so inseparable from the nature of the task. With few books and no colleagues at hand, one’s mind stales and loses sharpness. The coordinates do not and cannot explain anything but they allow data to be arranged so that one sees more clearly the locus and nature of the puzzles.

The high rationality of Aboriginal customs can be shown by such means. Customs of license, avoidance and joking (which are of mixed characteristics) and of divination and warlockry (which are of negative characteristics) respond interestingly to changed coordinates.

There are four steps in constructing this type of analysis. (a) A frame of reference is set up, in this case the general conception of a system of operations by persons on things, including persons, with objects in view. (b) The development of concepts which fit the frame and conception, in this case the ideas of signed-conduct, of transitive and intransitive operations, and of institutional events as transactions over things. (c) The abstraction of institutional events to prominent features, in this case the two associated features of external signs and operations which can be identified. (d) The application of the concepts to the features so that the connections are made clear, in this case by the use of visual means made up of a geometric imagery.

There is no significance in the fact that the course of the operations is counter-clockwise. It must be so under the conventions of the figure. Curiously, many of the dances which accompany the actual operations trace out circles by movements from right to left.

84Between phases 1 and 2 of the celebration, the youths who are to be taught what is only half-comprehended by even the wisest men, are separated physically from all but their teachers. They are then set apart even from these. All the external signs of their former position in life and their state of life are changed in the course of these operations. Their status also becomes negative. I shall say that this is generically an act of consecrating and making sacred.

In phase 3, already changed in locus and state of being, they are brought to the holy and dangerous place where they are to meet Karwadi. I shall say, again speaking generically, that they are immolated by blood and offered to The Mother of All. In phases 4 and 5 they are—or at least are conceived or reputed to be—destroyed by The Mother and then returned to life with a changed nature. But they have yet to be given a new state and position of life recognisable by external signs. These operations are distributed between phases 6, 7 and 8. When all is done the youths display on their bodies signs by which all the world knows that here are no longer boys but men, in a new state and locus of life, and with a higher social value. By virtue of the signs they are free to participate in the adult life and bring to it, while sharing, the good of their transformation.

Aboriginal thought is profoundly analogical, and for this reason they are much given to a rude simile and metaphor. Much of the symbolism of Punj can be traced to analogies, which seem to the Aborigines vivid and meaningful, between human and cosmic life. Intellectual conceptions are raised by symbolisation on these analogies. This of course is the essential symbol-function. But the development of the conceptions has taken an æsthetic rather than an intellectual course. The Aborigines sing, dance, mime and paint symbolistical conceptions of mysteries brought to their minds by analogical speculation. The living of a tradition is always a kind of essay on both principle and circumstance. Apparently a constant circumstance of life for them has been the absence of a specialised intellectual activity. Not that they are incapable of it: the high abstraction of the sub-section system is a convincing answer. But the absence of a class of thinkers has allowed the 85laws of æsthetic development to take their course guided perhaps only by the intuitive fitting of a symbolistical form to a mystery, which in the first place is perceived through an analogy. I shall deal with this process in a later paper, but a brief illustration is in place here.

In the Murinbata tradition the origin of life as such is not dealt with imaginatively. Life already was in The Dreaming. The fact is taken as a datum. To a certain extent the great split of the pristine unity into human and animal kingdoms is explored in mythology, but we are entitled to say that the mystery of life is its perpetuation or continuity after that event rather than the origin or schism.

The bearers of non-corporeal life are child-spirits. They feature in the tradition in a particular way—always as members of classes of pairs. That is, they are paired with (a) fresh water, more especially spring-water, (b) animal fat, and (c) green leaves. The Aborigines see likeness between the members of each pair such that the members are in inseparable connection whenever the context of thought or discourse is the perpetuation or continuity of human life. This seems to be fundamentally an analogical process of thought. A large number of similar classes exist in which natural and social phenomena are paired.

The child-spirits are the object or significatum of which water, fat and leaves are the signs. But the signs are not only indicative: they are efficacious as well. That is, the relation between sign and object is a productive relation. Power over the signs is productive of their objects. A large part of Aboriginal religion is concerned with the rightful possession and dutiful use of the efficacious signs.

What one encounters in the normal course of study is the symbolistical formulation of this and similar facts. That is, the deepening and the refining of the analogical perception. It is the essential function of symbol-systems to do so. Among the Murinbata the raw material of study presents itself in a complex and involuted form. Myth, song, dance, mime, social organisation and institutional practice all lie like so many veils between observer and that mystery which is phrased analogically. These acts in many cases are of unknown intent but they are carried on in love and loyalty. They are ancient things, and 86for this reason are venerated; they are good things, of which the oldest men are the witnesses; they are mysterious things and beautiful too; and, being enacted in a spirit which has in it something of piety, the intellectual veil over them deepens rather than shallows their meaning. At the same time, however, one cannot be unaware of a consistency which runs throughout. There is some kind of intuitive fitting together of the primary conceptions and their expression through complex symbolistical forms.

An interpretation of all this is inescapably metaphorical: we translate one system of metaphor into another. Perhaps, then, Fig. 1 has merit in that it interposes as few words as possible between things one can see or hear in Punj and their translation to paper in an ordered way.

When this is done the likeness between Punj and sacrifice, not only in the general fit of act to act and in the sequence of the acts, but also in the outcome, is such that it is not lightly to be brushed aside. The character of the problem then enlarges. I may perhaps avoid misunderstanding by saying first what I do not mean.

I do not mean or imply that there is any historical connection between the institutions. Or that a prime form existed anywhere in history or exists anywhere now. Or that the idea of sacrifice was ever explicit in Aboriginal culture. Or that such an idea is present in the Aboriginal unconscious. The comparison is an elementary one between the known and the unknown, between the named and the unnamed. I have no doubt that an Aboriginal anthropologist would write a paper with the title ‘The Lineaments of Punj in Sacrifice’.

The two institutions are similar in form but not identical, and belong to different types of system. The respect in which they are homomorphic is an operational one. At the same time there seems to be an isomorphism of a more fundamental kind. This is in the sense in which they both exhibit three classes of conduct. There is a productive activity, an exchange activity, and a distributive activity. In the first, something of value is taken for an end which requires its transformation, all productive activities being transformative. In the second, the transformed object is replaced, or held to be replaced, 87through a transaction—in this case what we might call a heavenly transaction—by another thing of another nature and greater worth. There is then a distributive activity: the replacement or counter-good of higher worth is shared between those who sustained the original loss.

To assimilate the comparison to an economic model is in no sense to give an ‘economic’ interpretation. It is simply to avail ourselves of an academic fact: that a very objective, meaningful, and universal model of conduct exists, by the perceptiveness of one discipline, which has some utility in the problems of another. The model has its counterpart in anthropology: the cousinly (and somewhat countrified) paradigm by which Radcliffe-Brown derived his concept of ‘social value’. The essence of the difficulties is that, although there has been some growth of the techniques of comparison, they do not allow us to extend this model—which is plainly, if remotely, applicable—to the problem in hand. The main reason is that the standing frames of reference of anthropology—structure, function, organisation—require only loose rather than exact comparisons. The exact comparisons require precise analyses of features and operations, which have been attempted only here and there, so that when two or more institutions show some kind of homomorphism we know the properties of the features and operations for which they are homomorphic. The apparent isomorphism of Punj and sacrifice—their construction after the same fashion as any joint human activity towards an object of value—illustrates the extent to which a strict comparison might be taken.

3. Structure or Operations?

A certain anxiety exists in modern anthropology lest interpretations should not give clear pictures of human persons at the business of life. To the extent to which the anxiety is justified, there seem to me to be three probable sources. One is the use of unsuitable metaphors of interpretation. A second is the use of abstract conceptions of unsuitable logical structure. The third is the habit of abstraction which issues in a 88virtualistic account, that is, a rough but somewhat misleading approximation, of what is under study. When such trends become orthodox approaches, it is difficult to counter them.

The imageries used in interpretation—like the symbolisms of Punj—tend to take on a life of their own. For example, we start with ‘structure’ and before long are dealing with ‘tension’ and ‘stress’ and ‘centrifugal and centripetal forces’. A praiseworthy effort to use consistently a useful idea leads to the growth of an interpretative system of metaphors of a physical-mechanistical kind about things which have another nature. The constructions are then projected. There will probably always be two kinds of anthropologists: those who say ‘social structures exist’, and those who say ‘let us construct them’. I shall not deny the first, but say only that the mode of existence is not observable. Radcliffe-Brown, at times a moderate, at others an exaggerated realist, set up the mystical doctrine of ‘real structure’, but the two aspects of his thought never lay well together. It is ironical that those who assert most firmly the reality of social structure seem to be those who maintain most firmly (as Radcliffe-Brown did not) that belief, including mystical belief, is causal in action. For if the activities which have or are a structure depend on belief there is then no real structure. Its mode of existence is mental.

A second source—the logical character of certain abstract conceptions—has deeply ensnared the discipline. Ideas like ‘culture’, ‘social structure’, ‘social organisation’ and others have little analytic utility, not because they are abstract, but because they are general and collective. Everything collected under them is culture, or has structure, or shows organisation. But to the syntheses which they represent the things which definitively mark off one class from another send no illumination. The attempts to make the ideas analytic are of an additive nature: we may thus emerge with perhaps one hundred varying statements of what culture is, each variant introducing a new class of features conceptually connected with different leading ideas and frames of reference. We meet culture, structure and organisation wherever we turn inquiry because we have pre-arranged that we shall do so, but we may be none the wiser how conflict relates to culture, or the rate of 89interest to social structure, or a trend in art to social organisation. For such reasons it is still difficult to find in anthropology two divisions of inquiry which relate to one another with anything like the clarity which connects, say, the theory of employment and the theory of investment in economics. However, in spite of its immensely broader field, we have in anthropology what few would attempt in economics: a mystical sociology of relations of association ranged in structures of structures; of general organismic functions within complex, compound systems of many interrelated institutions in varying states; and of the total organisation of activities of choice and decision.

A third source is the suppression, or virtual suppression, of the natural triad of person-object-person in favour of person-person relational study. If in the total-system approach the fact of individual persons is made somewhat epiphenomenal, in detailed relational-study the objects of activity become somewhat epiphenomenal. They are illustrative to, rather than integral, in role-and-position analyses.

The abstractly collective and dubiously, if not falsely, concrete ideas like structure, culture and organisation meet, in the same system of interpretative thought, the narrowly analytic and deficiently concrete ideas like role, choice and decision. One must make what one can of this through the veil of metaphor. The structure of anthropological interpretation clearly requires a detached examination if the discipline’s wealth of hard-won fact is to have the impact which it merits.

The institution of Punj is a notable concentration of well-articulated forms. The aspects which I have left tacit, rightly or wrongly, may be said to illustrate in a remarkably clear way how some well-known principles, or what are taken to be principles—the assimilation of alternate generations, the opposition of interdependent moieties, the dualism of affinity—provide a kind of framework even for religious life. On the level of symbolism, The Mother of All is a kind of equipoise of the Patriarchal Father. Much of the kind might be cited, and with a certain justification. But the intrinsic ex post reasoning should be clear. The ‘principles’ are not principles but descriptions of necessary and enabling conditions of social conduct. The conduct is not consequent upon them 90so much as that they are part and parcel of the totality of conduct. It is a condition of an act of exchange in a monetary economy that there be a buyer and a seller, but the principles of exchange are something very different. Economics would be a different discipline indeed if, while ignoring the principles of exchange—all the considerations which determine price-quantities of specified classes of goods, both in general and here-and-now—it elaborated an economic structure comparable with the anthropologist’s social structure. What reality the conception of social structure has is the reality of its content, and this comes in its entirety from our knowledge of social operations. But that knowledge is partial and uneven for reasons which I have in part indicated. The active search, of which we may see many signs, for a set of conceptions to complement that of social structure is in one sense mistaken: not a complement is required, but something which will make it possible, logically sound, and concretely persuasive. If there is a system of social life then it is probably in the first place a system of operations, and if the structure of the system can be abstracted then we shall best do so by developing conceptions adequate for the study of the operations. At the moment I do not consider that we possess them.

4. Transitive and Intransitive Conduct

I have found some advantages in using the idea of a transaction in place of the less concrete ‘interaction’, which is again collective and general. The idea of a transaction compels one to deal at all times with what I have called the natural triad of person-object-person. Social life is intrinsically though not exclusively transactional. The ennui of this knowledge is possibly the source of the mime of the blowfly in Punj, for the Aborigines have a good sense of the two-sidedness of human dealings. Fire, which is for them one of the symbols of sociality, serves and burns. Some of the deepest bitternesses of Murinbata life lie between brothers, who should not transact but share, forced into competitiveness by defections.91

In one of its aspects—and that, the sacrificial—Punj is, like the Melanesian cargo cults, a one-sided transaction. Men have to deal with a heavenly or spiritual partner. Here we encounter the difficulty of distinguishing ‘functional’ conduct from the ‘symbolical’ conduct with which it is usually contrasted. I believe the distinction can be made in a clearer way which is also more widely serviceable. The distinction is between transitive and intransitive conduct. More correctly, between transitive and intransitive operations.

Where activities are made up of transitive operations human intentions are actually transferred, and can be shown to be transferred, to the objects of the activities. The activities we call ‘technical’ are functional because the operations are transitive. We plant crops to grow food: to eat the yield is the proof and demonstration of transitivity. But there are innumerable objects of life—among them sometimes the most longed-for and highly-prized—of which no proof or demonstration of the outcome of our best efforts is, or seems, possible. If we pursue such objects then we have to proceed in hope, belief or faith. Activities in which the operations, as far as human knowledge goes, are intransitive make up a very large part of anthropology’s subject-matter. We describe them as ‘symbolical’ and often say that they ‘depend on mystical beliefs’. Some of the problems of symbolism will be dealt with in a later paper, but I shall say at this point that the second assertion states the relation incorrectly. Symbolical activities attract rather than depend on mystical beliefs, which express human longings and valuations rather than an illusion of technical competence.

Many of the activities of Punj really do ‘make the young men understand’, and can be shown to do so. In this respect they are technical, functional and transitive. But the transfers of other intentions, if real, have to be simulated. I maintain that the simulation occurs because there is suspicion or knowledge that transitivity is not attainable. That is, symbolical or as if activity may be carried out in hope but not necessarily with intention of transitivity, and it may well persist in the certain knowledge that there is no basis for hope. The symbolistical operations of the Karwadi though intransitive are not therefore less rational or 92functional than those which are transitive, for their intentions, while obviously complex, belong to an order which is being misunderstood and misrepresented if assimilated to the class of ‘technical’ intentions.

The symbolistical activities do not manipulate objects of life but express the valuations placed on them, and the desires for them. In this respect they are as rational as any other conduct towards objects of life, in being in logical accord with the perceived nature and value of the objects. Insofar as they impress clear conceptions of the objects on the minds of celebrants and endue them with a lasting sense of the values concerned then, in this secondary sense, the activities are transitive as well. These symbol-functions are indeed carried out with high efficiency by the choice of symbol-vehicles: truly brilliant combinations of mime, song, dance and stylised movements make what seems an indelible impression on those who see them. So much is this the case that there might well be neural or cortical changes as an outcome.

The Karwadi ceremony is the third initiation to which youths of the region are subjected.5 The first takes place at a tender age, usually when boys are between 8 and 10; the second at puberty; and the third at any age from 16 onwards. Each is a variation on the theme of withdrawal, transformation and return. The disciplines are severe and the emotional stresses are high and sustained. In the first ceremony the most obvious intent is to strike fear—of the unknown, of men, and of life—into the hearts of growing boys. The intent of the second is rather to implant in them self-respect, endurance of privation and pain, and a knowledge of their dependence on others. The third has been sufficiently described. The psychology which is applied throughout is highly effective: at the time of fear, there is a protector at hand; at the time of privation and pain, a warm companionship is always there; and, when the youths are most humbled, and perhaps most in fear, the proud things of acknowledged manhood are known to be not far off in time. At each stage the Aboriginal genius for music, song, mime and dance is applied with skill

93and passion. I have found little evidence of abstract, explicit teaching, and what there is seems obvious and banal, but the affective outcome is most marked. Personality may almost be seen to change under one’s eyes. It is not without reason that missionaries of long experience have found boys far less teachable, though not less tractable, after passing through the ceremonies. One suspects a redintegrative effect: responses to given stimuli have become so deeply settled that an Aborigine finds true interest, spiritual ease, and intellectual satisfaction only in that system of life which the stimuli connote. Initiated men learn to live with Europeanism, and even to manipulate it skilfully, but I have met none—except those whose traditional world had utterly collapsed—who were happy with it. It is not difficult to see why.

The symbolical accompaniments of the ceremonies become loved, not for their recondite import, but for their own sake. Many of the songs have no meaning, and the fact signifies nothing: but they are sung not less lovingly. The mimes and dances contain elements one may see in tribes 1,000 miles away in other contexts, of somewhat different meaning, and none the wiser. Even in adjacent tribes the myths associated with Karwadi vary considerably. Many of the Aborigines, especially the old, and most especially the wanaŋgal or wise men, are aware of and will discuss the more profound aspects of what is done, but a sustained intellectual detachment is rare, and only now and then do the cryptic or implicit elements of the ceremony come under discussion. The vivid symbolism of the blowfly and the wild licence of Tjirmumuk persist with almost no doctrine to sustain or explain them. The fact is that Punj is something to do rather than to talk about. And it is something to do joyfully: there is no mistaking the rapt participation. In no other circumstances does one see Aborigines so absorbed in a task. If it is a religious task—and, were there nothing else to go upon, the liturgical complexity and lavish symbolism would assure us that it is—here is one instance in which the old jest of the opus dei and the onus diei is meaningless.

It would be possible, and in many ways desirable, to relate the entire culture and organised life of the region to this single ceremony. In later 94papers in this series I shall trace at least some of the connections. My concern in this article has been to do two things. The first is to show that what is cryptic or implicit at the ontological level of Aboriginal culture responds at least interestingly to an act of comparison. The second is to show that a study of acts as operations has a useful place in an empirical and comparative anthropology. Indeed, it is perhaps only by such a method that we can bridge those awkward crossing-places which have caused so much difficulty. I refer here to the problems of making a logical and conceptual connection in our interpretations of the explicit and non-explicit elements of culture, and of transitive and intransitive conduct.

In the course of these papers I shall draw extensively on the work of both Durkheim and Radcliffe-Brown and at the same time depart widely from their viewpoints. In particular, I have found it impossible to make sense of Aboriginal life in terms of Durkheim’s well-known dichotomy ‘the sacred’ and ‘the profane’. The question will be examined in another paper, with special relation to the custom of Tjirmumuk. My narrative will have made plain that the custom, while being an integral part of Punj, is in many ways the reverse of which the main ceremony is the obverse. If, with reason, we describe the main ceremony as sacred, or concerned with sacred things, we are obliged by Durkheim’s scheme to say that Tjirmumuk is an act of profanation. In Aboriginal eyes it most assuredly is not. The native testimony is that it ‘belongs to Karwadi’.

I have sought to describe Punj, or at least its central events, as a liturgical ceremony because it is a kind of work reverential to, though not worshipful of, Karwadi, and because it is conducted with the highest formality. It is also a rite because it conforms to a set formulary perennially followed without important variation. We must thus inquire, if Durkheim’s dichotomy is valid, in what circumstances a sacred or religious rite can contain its own contrary or opposite as part of itself.

An operational study can of course be as broad or as detailed as one wishes. The gross operations I have mentioned here resolve into constituents, and these too are transitive and intransitive. I leave this question for separate study in relation to the magical content of the ceremony.

1 I should here explain that close affines are not attacked in these ways. Men direct their attentions to more distant classificatory relations. There is an unwillingness to risk offending men intimately linked by actual marriages.

2 One man told me that during the blooding he used to feel weak with fear of the unknown, and that his emotional stress was nearly unbearable when the bullroarers began to sound. It is not unknown for timid youths to lose control of their sphincter muscles.

3 I was myself inducted into the status of yuŋguana by the Nangiomeri, a neighbouring people of the same general culture, in 1934–35. I was addressed and referred to by the term until a few years ago when the subsection term Djaŋnari, which can also be used as a name, was substituted for it. About the same age-limitation applies to Kadu Punj when used as a term of address or reference.

4 Even when they learn that their fear is groundless many youths—at least many have told me so—go on for days or weeks feeling that they may have been lulled into a false security. Several I know could not bring themselves to believe that The Mother did not exist. Full knowledge brought immense relief but I saw no signs of the cynicism one might have expected. Evidently the interior life is so deepened that the inculcation of fear comes to seem to them just and wise.

5 All three were discontinued after the war. I disregard a fourth ceremony which is quite well remembered though abandoned perhaps half a century ago. It preceded the three others.