4

Aboriginal fishing rights on the New South Wales South Coast: a Court Case

This paper arises from the prosecution of seven Aboriginal men from the South Coast of New South Wales. The men were arrested in possession of mussels, rock lobsters and between 12 and 1,450 abalone in 1991 and 1992. The Department of Fisheries claimed these to be illegally obtained. They saw the men as poachers—a serious offence with significant penalties, fines, confiscation of diving equipment and possible jail terms. The men claimed their arrest was an infringement of their customary rights. These rights, the men contested, existed and continued to exist regardless of government quota systems and fishing licenses imposed over the last 30 years. There was nothing, they observed, in the Fisheries and Oyster Farms Act (1935)1 that specifically extinguished their rights. The men were, however, prosecuted as criminals and the NSW Land Council sought to defend them and their traditional rights.2

112The case first went to the Magistrates Court, then the Supreme Court and finally the Court of Appeal. The outcome recognised the existence of a traditional right to fish but questioned whether the defendant3 was actually practising that right at the time of his arrest. The case entailed archaeological and ethnographic documentation and complex litigation which at times seemed removed from the traditions in question.

Many of the legal and contextual aspects of the case are, in a sense, beyond the arena of this ethnographic case study but are recounted as they provide a flavour and a sense of the reality of the process of determining traditional rights in court. The legal issues are complex and people have differing views on them.

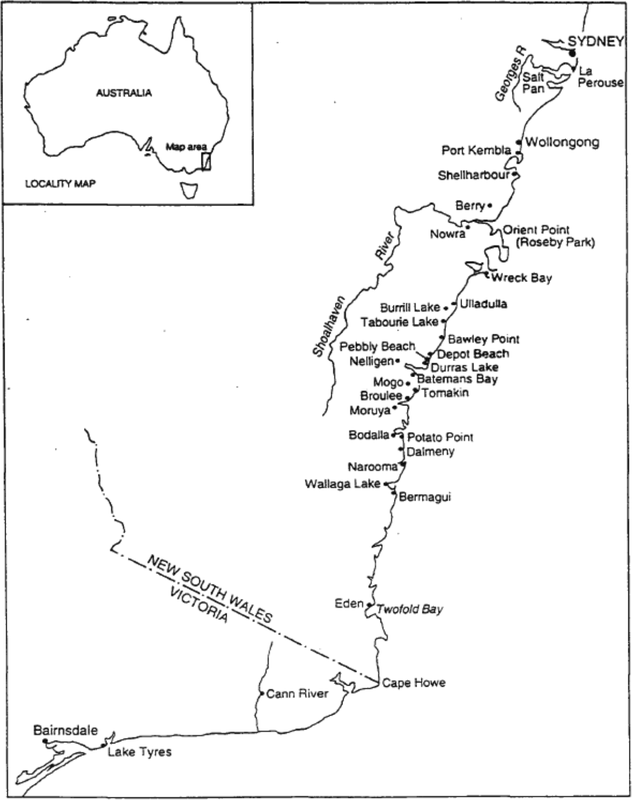

The paper provides a background to the case by outlining the sequence of events leading up to and surrounding the hearings and offers some observations about the legal outcomes. It also summarises the archaeological and ethnographic material presented to the court and comments on the nature of data collection. The original investigation entailed the documentation of genealogical, anecdotal and historical information for over 300 people, in 25 families spread between Sydney and eastern Victoria over the last 140 years (Figure 4:1, Cane 1992 a and b). This was a substantial task which resulted in the production of a linear, and rather frank, historical account of the association amongst the men charged, their ancestors, the sea and the South Coast. The original account of fishing on the South Coast of New South Wales has been condensed and organised so as to outline the family connections amongst the defendants as simply as possible and place them in the broader historical and geographic setting.

113

Figure 4:1 The south coast of New South Wales114

Some background to the investigation

The court cases took place between 1992 and 1994. The seven4 men involved were arrested for poaching on the South Coast of New South Wales, between October 1991 and March 1992 (see Figure 4:2). Those charged were summoned to appear before the Batemans Bay Local Court in April 1992. An adjournment was sought in order to have the hearing transferred to Sydney where the case was resumed in July 1992. The ethnographic and archaeological material was presented at this hearing, but the case was then adjourned until March 1993 to allow time to review the material and to consider the significance of the issues at hand.5 This hearing was lost by the defendant and an appeal was made to the Supreme Court in October 1993. This appeal was also lost and the case was again appealed before the Court of Appeal in August 1994

An investigation was commissioned by the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council in mid-June 1992 to determine the legitimacy of the traditional rights claimed by the defendants. This study was conducted over the course of three weeks between the time of notification and the hearing in the Local Court in Sydney.

It may surprise some readers that such an important case was prepared in such a short time. There may have been a number of reasons for this. The timing of the case was obviously a significant factor, as the men were charged between October 1991 and March 1992, and appeared in the Local Court in July that year. Thus there were only a

115few months separating the charges and the hearing. Cost may also have been a factor, and presumably many of those involved had other commitments which prevented the planning and organisation of the case until quite late in the proceedings.

Figure 4:2: Summary of charges against defendants, October 1991–March 1992

| Defendant | Charge | Defence |

| Brierly | 8 rock lobsters, 1 cm under size | Not intending to keep undersized fish |

| Carriage | 97kg (1,450) abalone | For annual community football barbecue |

| R. Masson | 92 abalone | Only 40 abalone, non-commercial, for family |

| Nye | 12 abalone | Always dived for abalone, can’t get licence |

| Stewart | 17 abalone | To be shared between two divers |

| 39 abalone—33 under size | Unemployed, for wife and 7 family members | |

| Carter | (with Stewart, above) | Accompanying Stewart and Carriage on dive |

| K. Mason | 160 abalone | Charge ‘a lie’, only a small quantity of abalone |

| Threatening an inspector | Inspector threw diving gear off cliff | |

| 77 abalone | ‘A lie’—had one lobster and six abalone | |

| 18 litres of mussels | For family, unaware of legal limit on mussels |

116Preparing the defence for the case commenced with a meeting held at the Regional Land Council in Narooma, NSW at which there was a strong desire to assert and defend what the men perceived as their traditional rights. Several concerns were raised at this meeting.

The first was that the case would be the first traditional fishing rights case in Australia. As such it would be an important case and all involved should be mindful of the responsibility they carried in mounting and participating in it. If the case were a success, the men and others involved would be applauded. If the case failed, then those involved would be criticised and a bad precedent could be set for others with stronger comparable rights. As it turned out, these concerns were unjustified as the legal outcome was ambivalent and the case provided some useful insights, rather than negative precedents.

The second concern related to the fact that only one witness was to be called. The legal advice was that it was safer to call an ‘expert witness’, who might be able to withstand the critical and skilful attack of an opposing Queen’s Council, than to expose a defendant who could unwittingly convict himself. This was a significant strategic decision that was ultimately to backfire. The original intention was to protect the defendants from the adversarial rigour of the court. The defence appeared not to know who might be called so they chose the safest course of defence: use one ‘expert witness’, myself.

There seemed to be no intention on behalf of those representing the defendants to prevent the exposure of some weakness in the defence or to bypass the relationship between each defendant and their espoused traditional right. As no-one knew which of the defendants would be called before the court first there was not (and could not have been) an intentional strategy of protecting one witness as against another or any witness because of any weakness in their claim. Each had varying historical associations with the sea, and each had varying degrees of experience and confidence in court.

Thirdly, it was made clear that I had only stood before a Queen’s Council once, had rarely spoken in Court and was nervous about doing so. It was also noted that I had precious little time to gather whatever 117information was available and consult whoever might be able to speak with authority on the depth and duration of the traditional fishing practices within the indigenous community. There were only three weeks before the case went to court. There were seven key defendants, allowing just three days’ research time per person, ignoring time for travel, organisation, historical research and report writing. It was likely that little could be documented in the available time and it was possible that much would be anecdotal and inadmissible in court.

The legal view seemed to be that something was better than nothing and, given the critical urgency of the cases and the fact that some of the men might go to jail, something had to be done. The defence also believed there was a lack of awareness of the significance of the High Court’s Mabo decision and native title more generally at the time. There seemed to be a view that any evidence presented to the court might be accepted, without opposition, before the implications of the evidence were grasped. It would be something of a surprise attack in which the acceptance of unopposed ethnographic evidence would implicitly verify the existence of a traditional right to fish. It was also assumed that additional information could be submitted later or introduced through cross examination if necessary.

In view of the severe shortage of time a strategy had to be adopted that would maximise the documentation of essential information. There was no time to observe, participate in, document or analyse the ‘ethnographic experience’—or even observe much of the fishing customs of the South Coast people in action. Although fishing activities were occurring throughout the investigation (see below), there was no time to wait on the beach for the tide, the wind and the swell to go fishing. There was no opportunity to participate significantly in fishing activities, document the distribution of collected foods, calculate the nutritional returns, estimate the proportions and determine the commercial and subsistence values of the seafood harvested. We did not have the time for, and questioned the value of, defining the meaning of tradition in this fishing community, nor did we have the opportunity to 118specify the laws and customs that may comprise those traditions. The best evidence one could hope to achieve was a comprehensive historical account of who fished and who did not, an account from which the tradition of fishing and its associated rights would be evident, if it existed. It must be remembered that at this stage of the prosecutions, it was not even clear whether the defendants were from the South Coast, let alone whether they had a history of fishing.

Thus the history of each defendant’s family and their association with the South Coast had to be documented before the alleged traditional fishing right could be ascertained. The presence or absence of a traditional fishing right would become apparent through an historical narrative and the presentation of accurate, unembellished individual historical accounts. If there was a strong and continuous association between a defendant, the South Coast and fishing, then we assumed the tradition of fishing would be shown; the tradition would plainly be seen to have continued through history and into the present. Equally, if there were no historic and geographic links between a defendant, the South Coast and fishing, then it would be clear that there was no tradition of fishing and no traditional right. There would also be situations in which the historic experiences of the defendants would fall between these two extremes. It was difficult to predict how history would present itself until the investigation was complete, but it seemed plain that the courts would have to adjudicate on some cases that were less clear-cut than others. Thus it was obligatory to provide clear and detailed evidence so the courts could make a reasonable assessment of the nature of the traditional right.

With these issues in mind an intense effort was made to research accessible material: reports, journals, church records, old newspapers, regional historic sources and community notes, tape recordings and histories. Interviews were also arranged and undertaken with each of the defendants, their families and elderly community members living in Wallaga Lake, Narooma, Mogo, Batemans Bay, Ulladulla, Jervis Bay and Berri. The names of individuals supplying this information were 119not associated with material in the original reports so as to minimise any repercussions after the hearings.6

Time pressures were such that material was collected during the day, drafted and dictated in the evenings, couriered to Sydney in the morning, returned by fax that night, read and re-faxed that night as other text was dictated and couriered to Sydney. In this way the text was researched and drafted simultaneously—and completed within the time available. Final additions were written into the text at midnight on the day before the first hearing in Sydney.

By the time the hearing was convened historical material had been gathered for five of the seven defendants: Nye, K. Mason, Carriage, Stewart and Carter. No information had been collected for Brierly and R. Mason, the defendant later called before the court. A supplementary investigation was then completed for Brierly and R. Mason and submitted in September 1992. Two other studies were completed at the same time as the ethnographic investigation. One (Colley 1992) examined the archaeological evidence for abalone fishing on the South Coast of NSW and the other, (Egloff 1992a) reported on the significance of coastal maritime resources to Aboriginal communities on the South Coast. Copies of the ethnographic study were circulated to each of the Aboriginal families involved in the case and sent out for review.

The process of review was used as an effective means of verifying and checking the information contained within the original report and insuring against any surprises in court, should the counsel representing the Department of Fisheries also have been getting expert advice. The report was sent to Egloff (1993) and Sutton (1993), both of whom provided excellent, although different, reviews. They pointed to both positive and negative aspects of the study and identified relevant information which had been missed. Foremost amongst these were

120the genealogies and ethnographic notes made by Norman Tindale at Wallaga Lake in the late 1930s. These were held by the South Australian Museum, which kindly copied and sent the relevant family trees a few days before the court hearing in March 1993.

A summary of the material presented to the court

The material presented to the court focused on the prehistoric evidence for abalone collection and the historic evidence for fishing amongst the defendants living on the South Coast of New South Wales. The archaeological evidence demonstrated that abalone consumption was moderately important in precontact coastal societies on the South Coast and that abalone had been harvested for the last 3,000—4,000 years at Currarong and into the historic era at Durras North (Colley 1992:10).

More recent investigations (not presented to the court) of coastal archaeological sites around the nation indicate that abalone collection is a stronger, more dominant feature of the archaeological record in southern New South Wales than anywhere else in the country with the exception of coastal Tasmania and some sites in western Victoria. The earliest evidence for abalone collection comes from the Nullarbor Plain, some 12,000–16,000 years ago (Cane 1995, 1996).

The archaeological evidence from the South Coast also points to a mixed and intensified exploitation of the sea. This contrasts with the situation in northern New South Wales, where marine exploitation was more selective, and in neighbouring Victoria, where marine exploitation appears to have been secondary to the exploitation of the coastal plain (Bailey 1975; McBryde 1982; Gaughwin 1981; Frankel et al. 1989; Cane 1995).

On the South Coast of New South Wales the settlement pattern was semi-nomadic with some movement inland (Poiner 1976:199). Exploitation of the coast intensified over the last 2,000 years with evidence of overexploitation of local shellfish resources in some areas 121(Burrill Lake and Currarong; Lampert 1971:61) and a shift from open shore to estuarine shellfish between 1,200 and 700 years ago (Sullivan 1987:97). This change was accompanied by an increase in the range and quantity of littoral resources exploited (Sullivan 1984).

Primary marine resources included shellfish, fish, seabirds and mammals. The technology used to obtain these food items included shell blades (for prizing shell fish from rocks), canoes, shell fishhooks, spears with bone points, hoop nets, traps and weirs (made of branches), baskets for storage, torch light for night fishing and poisons from various plants (Lawrence 1968; Nicholson and Cane 1994).

A significant aspect of the prehistoric and protohistoric economic record is that fishing generally, as distinct from abalone collection specifically, was the key economic activity in South Coast communities. As mentioned in the original report:

…fishing was an important economic activity in which abalone collection was an integral part … it is illustrative to note that during the two weeks spent collecting information for this paper I observed one family collecting small numbers of abalone for food, yet also observed members of the same family collect two loads of salmon, one three and a half tonnes and the other just over three tonnes. Clearly the difference in magnitude is very great…In this sense the traditional relevance of various components of the fishing economy have not seen drastic change in Aboriginal society. What has changed is European perceptions of a small and now scarce component of that larger economic base (Cane 1992a:2,3).

The earliest historic observations of traditional fishing on the South Coast come from mariners between 1798 and 1826. They speak of the great desire of indigenous people for fish, observed the remain of fish and seals at Aboriginal camps and saw them actively involved in European-like fishing practices, notably netting, a tradition they already practised with their own nets, and which is still active today (Plate 1: Collins 1798; Grant 1801 and D’Urville 1826, quoted in Cane 1987:32, 33; Roseman 1987:61; also Lawrence 1968; White 1987). 122

Land-based settlement after this period—through to the 1840s—brought territorial conflict, warfare, massacre and poisoning of the people on the South Coast. There is reliable evidence that people were successful in maintaining and adapting traditions to the new economic circumstances (Cameron 1987; Rose 1990). Tribal people were recorded assisting the settlement process with traditional skills and resources. A resident in Moruya noted, in 1837, that ‘shortage (of food) was at times acute. Aboriginal people saved the settlement several times from starvation by supplying fish and oysters’ (in Cameron 1987:78). Whether or not these products were bartered or sold is unclear, but it is clear that traditional foods were being sold later in the century: ‘about 50 blacks were camped at Blackfellows Lake, on the Bega River between Bega and Tathra, some of who worked for wages and some sold honey and fish’ (in Cameron 1987:78). The application of Aboriginal fishing traditions to support the European economy seems to have begun shortly after colonisation and survives today, through bartering and direct sale. Many of the defendants have no independent income and regularly trade fish, abalone and crayfish for meat and other goods.

Aboriginal men and women were involved in the European whaling industry from the outset, although it is unknown whether they received money or goods for their labour. Two boats were ‘manned entirely by Aborigines’ at Twofold Bay in 1839 (Letter to Colonial Secretary, quoted in Organ 1990:246) and three Aboriginal crews were working in Eden in 1844. One elderly Aboriginal man in the region adopted the name of the famous artist and whaler Sir Walter Oswald Brierly, and was actively involved in whaling in the 1840s (Mead 1985; Davidson 1986). One of his descendants, Allan Brierly, was a defendant in this case.

Between 1829 and 1846 indigenous people between Wollongong and Broulee were described as selling fish and subsisting ‘from their ordinary pursuits of hunting and fishing’ (Organ 1990:282) and, as access to land diminished in the 1840s through settlement, forestry and pastoral developments, ‘people in the district (Broulee) depend more on the sea than the bush for food’ (Census information for 1846, in Organ 1990:284, 285). 123

A formal request to the New South Wales Government by Aboriginal people for fishing boats occurred in 1876 and, by 1878, people in Roseby Park, Bega, Eden and Moruya were fishing with government boats and equipment. Census information reveals that indigenous people in Moruya were described as ‘remarkably well off and can earn the same wages as Europeans’ with income earned from four fishing boats (Bayley 1975:122; Organ 1990:336, 340, 342).

Between 1885 and 1905, a number of reserves were set up between Milton, Tomakin, Tuross and Wallaga Lake on the South Coast.7 These were ‘intended as a residential base from which to fish’ (Goodall 1982:34, 43). People also began to get seasonal work with farmers, such as small fruit and pea farmers. Others worked in timber mills. Most continued to subsist through fishing and the government provided another 18 boats to South Coast people (Goodall 1982:43, 58).

Life at the end of last century was captured through the eyes of an Aboriginal artist, Mickey the Cripple, at Ulladulla. His painting reflects camp life, ceremonial activity and the getting of traditional foods. The most relevant paintings in the context of this paper feature sailing ships, fish, fishing boats and fishing. The paintings conveys the broad focus of Aboriginal interests and activities at this time, and imply that at least half of their customary interests centred on the sea (see Sayers 1994: colour plates 15,16,17,19,20).

A number of the families of the defendants appear in the historical record during the early years of settlement. The Carter family, for example, were living in the Cobargo district, ‘when white man first came around’8, probably the 1820s. They were also among the first people at Wreck Bay (under the name Hadigadi, see Egloff 1981).

124The Stewart family are first recorded on the South Coast in the mid-1800s. Their children were born at Wallaga Lake in the 1870s9 and lived at Corunna Lake near Narooma in 189210, exactly 100 years before their descendant, Andrew Stewart, was arrested for poaching.

The Carriage family were at Batemans Bay before the 1850s, and family members are recorded in marriage and birth in 1859, 1863, 1869 and 189911. The family did not move from Batemans Bay and Joey Carriage was arrested in the area in 1992.

The early members of the Mason family were living at Bega in 1867 and and eastern Victoria in 1887. At this time the family were recorded ‘getting native food like swans eggs, black fish … and luderick’12 (Pepper 1980:75–77).

During and after the First World War, South Coast families had very little employment opportunities and depended heavily on fishing. Fish were used for subsistence and sold to market. The commercial success of indigenous fisherman was such that between 1914 and 1918, non-Aboriginal fishermen began to protest through the Fisheries Department to the Aboriginal Protectorate Board. Aboriginal people were seen as a threat to non-Aboriginal fishing livelihoods (Goodall 1982:32, 115, 174).

125Pressure was also applied to give land to returned soldiers during this period and 75% of reserve land allocated the previous century was revoked. Eight reserves were revoked on the South Coast. Some near Narooma were still being used as fishing bases (Goodall 1982:227, Plate 3).

The family of the defendant Keith Nye was fishing near Ulladulla and Durras at the turn of the century and at Wreck Bay after the First World War, where they built humpies before the present community was established. The family packed up their boats and nets, and rowed back to Broulee (over 100 km.) as more Aboriginal people came to Wreck Bay.13 The family then settled near Batemans Bay where they lived in a tin humpy at Tomakin. They were known as beach fisherman (fishing for mullet, salmon, flathead and bream). Members of the Carter family were also living in Wreck Bay, and moved between there and Wallaga Lake. Members of the family fished and collected oysters. They married into the Mason family before the Second World War.

Early members of the Mason line were settled at La Perouse (Kevin Mason) and Batemans Bay (Ronald Mason) at the turn of the century and lived around the South Coast in subsequent decades. All were fishermen in those early years. The family of Kevin Mason subsequently became sleeper-cutters and boxers after the First World War. The family of Ron Mason continued to live at Batemans Bay (Nelligan) after the First World War. They made their own boats and nets and were known by the name ‘Katu’ or ‘Katungil’ meaning ‘sea people’ (also Eades 1976:87). The family adopted the name Cooley around this time in recognition of their association with some Chinese people living nearby.

Members of the Cooley family married into the Stewart family. The Stewarts were also living on the South Coast, but farming and working in the wood mills. The family stayed with the land, subsequently becoming more involved in timber milling than fishing. Two members of the Stewart family also married Carriages. The Carriages are recorded at Pebbly Beach in 1899 and 190, where they are remembered fishing with the Nye family. The Carriage family were still living at Pebbly Beach in

1261922 and 1925, when members of the family married Stewarts.14 Four family members were fishing and others had begun working in the mills with the Stewarts.

Throughout this period the Brierly family lived in Eden (and were involved in the moribund whaling industry). In 1922 they moved from Eden to the mouth of the Moruya River, where they remain today. Much of their original land has been resumed to build the Moruya airport, but the local boat ramp is still called Brierly’s Landing. The family house overlooks the river mouth. Family members married into the Mason line and become distant relations to the Masons. All the men of the Brierly family were fishermen and one was drowned at sea.

Thus by the Second World War a number of South Coast family connections had been made. Brierlys had married Masons, Masons had married Stewarts, Stewarts had married Carriages, and Carters had married Masons. Some families were heavily involved in fishing: some were not. As a group, however, fishing remained the dominant community means of subsistence. This communal tradition continued throughout the next four decades and ultimately led to the sequential arrest, prosecution and defence of various family members in 1992.

The social and economic situation of the Depression continued for these families after the Second World War. There was a short period of employment near the close of the war (Long 1970), but then people returned to seasonal work—fruit and pea picking, timber cutting and fishing—as regular employment evaporated. The fishing skills of people living on impoverished South Coast settlements were capitalised on by the government, whose policies encouraged ‘self supporting fishing stations’ like Roseby Park, Wallaga Lake and Wreck Bay.15 Fishing was the most important source of income for people at Wreck Bay. Three people

127owned their own boats. Others were involved in the transportation and selling of fish (Long 1970:59).

By and large, however, fishing activity on the South Coast was informal, geared towards subsistence rather than significant economic returns. Aboriginal people were described as having little part in the South Coast fishing industry and as having difficulty managing, financing and maintaining commercial fishing operations. The fishing industry provided limited employment opportunities with most families involved in the same forms of subsistence activities they had practised since settlement: fishing, vegetable picking and forestry work (Scott 1969).

The Carters were living at Wreck Bay through this era. Fishing continued, but the tradition was changing. Boats were bigger and fishing activities went further afield. Eight of the Brierly children fished, for example, but now moved between Eden and Broulee in pursuit of fish for harvest. One family member worked on a trawler, travelling as far as Newcastle and Bass Strait. The family had their own 45–foot boat, but lost it in a flood on the Moruya River. Another of their children died at sea.

The father of the defendant Kevin Mason married into a family from southern Victoria. He fished, but the Victorian family were mostly pea-pickers. Members of the family of Ron Mason married into the next generation of Stewarts, reinforcing existing family connections amongst the Mason, Stewart, Carter and Carriage families. Four members of the Mason family were fishing.

The Carriage family was still living at Batemans Bay. The aunt of Joey Carriage married into the Nye family in 1948. She was the mother of Keith Nye, another defendant in the fishing case. His parents moved to Jervis Bay, camping and fishing for mullet, before travelling to Ulladulla. All the men of the Nye family fished. The seasonal catch was mullet through February and March, blackfish in April, salmon through winter, ‘travelling fish’ i.e. mullet and salmon, through the spring, and bream at Christmas. 128

The fishermen were apparently paid a penny per pound for salmon and a shilling for big bream. They caught lobster ‘by the bag full’, but only took abalone ‘for a feed’. This generation ‘didn’t touch them, got nothing for them’. The father of the defendant Keith Nye apparently liked to eat abalone. Men who fished in that era described working hard and long hours, often rowing their16–foot boats from Wreck Bay to Ulladulla and East Lynne (over 140 km). The women minded the children, spotted fish, pulled nets, sewed nets and packed boxes of fish.

The Nye family were, by this time, a well established fishing family and lived almost entirely at Barlings Beach, where there was an Aboriginal camp of about eight huts. They spotted fish from a pole and had their own gear and a double ended boat.16 This tradition continues today with the Nyes being one of the few remaining licensed beach fishermen in NSW.17

The father of the defendant Andrew Stewart married one of the Nye family, completing the family connections between all subsequent defendants. All the Stewarts were timber workers at this stage.

The last thirty years have seen increased documentary evidence of Aboriginal life on the South Coast. Local people have collected much of this themselves sporadically between 1965 and 1992.18 This information reveals an attenuated core of language and mythology, but highlights the significance of the sea in that remnant body of original

129knowledge. Twenty-two words survive which are associated with the sea and its exploitable content. Remnant myths are also documented, the most significant of them relate to the sea and the coast (Eades 1976; Rose 1990). Twelve personal histories19 have also been recorded over the last 35 years which portray coastal life, fishing exploits, seasonal movement, school fishing, night fishing, prawning, crabbing (for bait), lobster collection, shellfish collection (pipis, mussels, oysters and abalone), spearfishing, spear construction and identify a variety of fishing spots between Wallaga Lake and Wreck Bay.

These local accounts are supported by more detailed investigations of language, community histories, economic activity, expressions of Aboriginality and cultural heritage. Themes of the sea pervade these accounts (Bell 1965; Scott 1969; Eades 1976; Rose 1976; Attenbrow 1976; Poiner 1976; Carter 1984; Cane 1987). They indicate that fishing remained an important means of subsisting and earning money. Salmon fishing was still a dominant activity with over 100 tonnes being landed in one month during spring in the late 1980s.20 These sold for around $700 a tonne i.e. $70,000 for the monthly haul.

The need to fish and the assumed right to fish continued throughout the period. Members of the South Coast community requested that their customary fishing rights be recognised and in 1980 a Select Committee of the Legislative Assembly recommended legislation be

130enacted to do so (1980:87). Individuals continued to openly breach Crown Law in spite of the cumulative risks. Breaches escalated consistently over the last 20 years. One defendant has been arrested 12 times and has spent 45 days in jail. The regularity with which the offences have occurred says something about individual economic need, resistance to fishing regulations, and the conviction and belief in the community’s historic traditional right to fish. A brief summary of the present situation follows.

The Nyes are recognised by both long-term Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal residents of the South Coast as an established fishing family. All the male members of the family fish. The defendant, Keith Nye, grew up at Barlings Beach, dropped out of school and went fishing. He fished with his father’s gear until his father died. Keith lost interest for a while and his gear was taken over by his first cousin (his ‘brother’ in Aboriginal custom). Keith remained unemployed and returned to free diving21 and line fishing, selling fish for money and trading it for food. He has been diving for 17 of his 35 years. He was arrested with 12 abalone (see Figure 4:2).

Joey Carriage has fished and harvested abalone most of his life. He sold abalone for six pence a pound in his youth. His nickname is Snapper, after his grandfather,22 with whom he fished as a child. His mother is Keith Nye’s aunt and Joey has often fished and cleaned abalone with the Nyes. He was arrested with 97 kg of abalone (possibly worth $10,000 if sold) in the company of Nick Carter and Andrew Stewart.

131Nick Carter was born in Berry and went to school in Jervis Bay. Nick is also a fisherman, having travelled to Darwin to work on the prawn trawlers. He has been unemployed since his return and now fishes between Wreck Bay and Batemans Bay. His wife is the daughter of a fisherman from Roseby Park.

The mother of Andrew Stewart is also a Nye. Andrew works primarily as a timber miller and was arrested with 39 abalone.

Allan Brierly grew up at Moruya and spent most of his life at sea. He could row a boat at the age of three and was taken out of school by his father ‘to work with fishing boats’. He is a licensed fisherman and still lives with and works for his father, under the direction of his eldest brother. The family have their own gear: freezers, boats, vehicles and nets. He was arrested with undersized lobster.

Kevin Mason was also born at Berry. His father described him as ‘mad on mutton fish’ (abalone) as a child. The family were poor and Kevin gathered ‘goanna. porcupine and abalone’ in his childhood. He travelled with his father, fishing between Bermagui and Cape Conran. He then worked in Sydney before returning to the South Coast. He is well known and liked in the region. His nickname is the Phantom because of his elusive and independent personality. He is a well known fisherman, and has a number of legendary fishing exploits attributed to him (shark attacks and the like). Two of his three brothers are fishermen. He was facing seven charges accrued between 1991 and 1992 for over 200 abalone, 18 litres of edible mussels and failing to comply with and threatening a fisheries’ officer.

His nephew is Ron Mason, the defendant whose case was tried in court. Ron was 26 years old at the time. He first dived at the age of five, has worked primarily as a deckhand on fishing boats and now has a Class Five skipper’s ticket. Ron was arrested with 92 abalone. All his gear was taken by the Fisheries Inspector and he was publicly stripped down to his underwear in the main street of town.23

132

The hearings and their outcomes

The hearing for Ronald Mason took place in the Magistrate’s Court in Sydney on 1 March 1993. I found the cross-examination a trying and confusing process, bearing out the fears of the defendants and their legal representatives that the court is a tense, hostile and disempowering environment, draped in ethnocentric bias, shrouded in mystifying technicalities and fortified by adversarial processes.24

The issues addressed in the process of cross-examination related to the area in which the charges took place, whether or not the defendant was a member of the South Coast Aboriginal community of that area, the role of fishing in traditional society, the history of disputation amongst tribal groups in respect of the right to fish, the nature of post-colonial evidence for the assertion of fishing rights to a particular area, the nature of fishing customs and the exclusive nature of those customs.25

Two months later the Magistrate handed down his decision on the evidence and arguments put before him. His key determination was that:

I am satisfied that the following facts have been established. Firstly that the defendant is an aboriginal (sic) and a descendant of the Mason family whose members have inhabited the South Coast area of New South Wales since the eighteen eighties and second that the Mason family, together with a number of other aboriginal families have traditionally fished those coastal waters for abalone as a major source of food, however there is in my view a factual question which arises in this case, namely whether the defendant was in fact exercising

133 a customary or traditional right on 9 October 1991 when he shucked and then possessed 92 abalone. As I have already said the defendant did not give evidence in this case and therefore there is no evidence before me as to the defendant’s intentions in relation to the subject abalone. In other words there is no evidence that the defendant either intended to consume the abalone himself or to make mem available for consumption by the immediate members of his family or to exchange them for other food. Accordingly I am not satisfied that the defendant has established as a matter of fact that he was exercising a customary right to fish for abalone on 9 October 1991 (Clugston 1993:3).

The Magistrate thus accepted the traditional right of the defendant to fish, but was not convinced Mason was practising that right at the time of his arrest. The obvious question that arises from this observation is that if the defendant was not exercising a traditional right, then what right was he exercising? The implicit answer is that the defendant was exercising a commercial right, although there was no evidence before the Magistrate that this was the case either. So the question hangs in the balance. A traditional right appears to exist, but the defendant appears not to have been practising it. Is this a legitimate verdict? Should Mason have taken the stand? What would have been the result if Mason had stated the abalone were for himself and his immediate family? What would have been the Magistrate’s determination if Mason was intending to sell them—as had been the historic practice of his people for the last 150 years?

The Magistrate then went on to consider whether or not the right asserted by the defendant was a land right or usufructuary right recognised by Australian common law. He concluded that ‘a customary right to harvest abalone is not linked to any claim for native title to the submerged lands adjacent to the South Coast of New South Wales’ and that the:

decision of the High Court in Mabo Number 2 does not support the proposition that the common law now recognises customary aboriginal (sic) fishing rights such that a claimed 134right must first be extinguished by legislation before an aboriginal exercising such a right is obliged to comply with legislation effecting that right (Clugston 1993:4).

Mr Justice Young of the New South Wales Supreme Court26 was less sympathetic to Mason’s case than the Magistrate. He compared ‘native peoples’ with a ‘type of primitive company’, contrasted the traditional rights claimed on the South Coast with those of the Cook Islands,27 denied the existence of both proprietary and usufructuary rights, considered the latter to have as much real property value as a ‘title of honour or an advowson’ and indicated that he believed the current legislation did not discriminate against Aboriginal people because it was established to regulate the activities and competing rights of ‘all people’.

His judgment concluded that the evidence presented to the Magistrate’s Court failed to disclose a ‘group of people living in community who had settled rights and privileges under a system of laws and customs which they all respected’ (Chalk 1993:1). Further Mason was not, apparently, a biological descendant or connected with the relevant Aboriginal people who once exercised traditional and customary rights on the South Coast of New South Wales.28

This judgment is also interesting as it raises the issue of the existence of a commercial right to fish as against a traditional right to fish. Justice Young’s assessment was that the expansion of a traditional right to fish for subsistence to a right to fish for commercial gain ‘would be such an expansion of the right as to be a different right’. He admitted the ‘line may be difficult to draw’ but observed ‘it is often easy to recognise when that line has been crossed’ (Young 1993:21,22). He did not say

135when that line might have been crossed, but he obviously believed it had been. A logical inference is that the decisive crossing took place when indigenous people first began selling fish early in the last century, as the South Coast was just being colonised. If so, it is hard to accept that Aboriginal fishing traditions on the South Coast ended before European settlement, let alone European customs, had taken hold in southern New South Wales.

Following the failure of the appeal before the Supreme Court, another appeal was lodged to the Court of Appeal. This appeal centred on the interpretation of usufructuary practices, the existence and nature of native title, the exclusivity of that traditional right, the nature of evidence for traditional fishing, the content of the traditional right and whether or not the appellant was exercising a traditional right (Roberts and Katz 1994).

The Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal due to a lack of evidence.29 The primary deficiency in the evidence appears to have been that the defendant did not give personal testimony as to whether or not he was practising his traditional right at the time of arrest. Justice Kirby (1994:26) develops the point as follows:

Why, I therefore ask myself…did Mr. Mason not give evidence that he was collecting the abalone in question within the ambit of the traditional and long practiced native entitlement which he set out to prove? He went to so much trouble to establish his genealogical legitimacy and the relevant practice of Aboriginal fishing for abalone back to the 1880s. Why would he fail to complete the chain of relevant evidence by the next logical step of bringing himself and his actions within that practice…he left unproved a vital link in respect of which the evidentiary or forensic onus was certainly on him. I cannot believe, in a case otherwise so well prepared and presented, that this was an accident or oversight. The only other inference available is that Mr. Mason’s evidence, if it had been called, could not have supported his claim that

136what he was doing at the time of his apprehension was in exercise of his native title rights as an Aboriginal Australian. For example, that it was for sale of the abalone to the general commercial fish market… That was fatal to the appellant’s attempt to prove his exemption from the operation of the regulation.

This position is the same as that reached by the Magistrate. It is a position that was disputed by the counsel for the appellant who countered that:

If there was a right to take abalone for any purpose…then the appellant’s intentions were irrelevant. If, on the other hand, the traditional right was limited in the way suggested by the Magistrate, then oral evidence by the defendant was not the only way in which his intention could be established. The prosecution evidence itself established that the abalone had been taken for non-commercial purposes: the abalone were shucked on the shore immediately after taking and then transported by the appellant to his residence, the appellant being a member of the group which traditionally took abalone for food (Roberts and Katz 1994:9).

It is clear with hindsight that even if the abalone were collected with commercial intent,30 an argument may have been mounted that this fell within the ambit of contemporary traditional practice. There was, it is now clear, no particular advantage (as the ruling from the Court of Appeal suggests) in hiding the possibility. A commercial right may have been successfully argued and its presentation would certainly have placed the issue on the table for future resolution.

One of the judgments from the Court of Appeal queried the strength of the evidence supporting the broader claim for traditional rights. One judge observed that ‘more needed to be proved to comply with the requirements’ of native title (Priestley 1994:12). As the historical records are scanty and rarely provide enough detailed information to connect a specific family with their traditional and customary activity

137consistently through history in a particular geographic location there may be difficulties in this regard. The evidence for the association of the Mason family with the South Coast and traditional fishing activities was not, in my opinion, the strongest amongst the men charged, but it was reasonably comprehensive nonetheless. This difficulty was identified in Cane (1992b) and recognised in Kirby (1994:19).

Yet not all the judges were of the same opinion as to the strength of the written evidence. Justice Kirby (1994:34) for example, observed:

The appellant, in my view, sufficiently established, by evidence of others, his genealogy as descended from Aboriginal Australia. He sufficiently established that his forebears traditionally fished, including for abalone… (but) held back from giving evidence that the abalone which he himself had been fishing… were within his asserted native title right.

The concern, however, from an ethnographic (if not legal) perspective is that the Magistrate in the Local Court and some of the judges in the Court of Appeal appear to have missed some of the evidence that was put before them. They may thus not have given Mason’s traditional rights the recognition and consideration they were due. Determinations from both courts refer to the Mason line extending back to the 1880s, whereas in fact it extends back to (and beyond) the 1860s. Both refer to R. Mason as follows:

He is a descendant of the Mason family, tracing to Paddy Sims (sic) who originally came from the La Perouse area and who I quote, ‘apparently did a bit of fishing and lived off rations and either lived on or fished at Bear Island’ (sic). The Mason line is coastal with part of the family emerging from the coastal districts of Victoria between the Cann River and Bairnsdale and the rest from the Illawarra Region, Nowra to La Perouse (in Clugston 1993:2; Kirby 1994:17).

This reference is slightly misquoted but, more importantly, refers to the family of K. Mason—another of the defendants—not R. Mason, the defendant before the court. K. Mason is R. Mason’s uncle. K. Mason’s 138brother and R. (Ron) Mason’s father is also called R. (Ron) Mason, so one can understand the confusion. But this hardly excuses a failure to correctly address the evidence.

The family of K. Mason are related to Paddy Simms and spreads from south Sydney to Eastern Victoria (as referred to in the judgments) while the family of R. Mason relates to the Stewart family and concentrates more closely on the South Coast (and not referenced in the judgments). There is an indirect connection between R. Mason (defendant) and Paddy Simms on his father’s side, but this is only part of the story.31 The name Mason is taken from Ron’s grandmother’s first husband. Little is known about him except that he was a sailor, died, and had no relationship to Paddy Simms. Ron’s grandfather then married a Ritchie but all the children kept the name Mason. So some children are actually Ritchie (such as K. Mason) and are descendants of Paddy Simms (about 1880) and others (R. Mason) are not.

More significantly Ron Mason is related, through his mother (Ella), to the Sutton, Cooley, Walker, Kaine and Stewart families, all of which were more involved with the sea and fishing activities than the Ritchie-Simms family line. Thus the failure of the judges and the magistrate to recognise a fishing tradition among the Mason (Simms) line is in error. The judges in the Court of Appeal either missed, misread or failed to refer to the evidence in relation to the key, maternal, side of the family of R. Mason. The presentation of and references to the ethnographic material strongly suggest that the judges (and magistrate) made a determination on evidence for the wrong person.

139

Figure 4:3: Family chronologies as summarised for the Magistrate in 1993

| Period | K. Mason | R. Mason |

| pre 1880 | South Coast, through Stewart (Kaine, Walker, Austin; Narooma area). | |

| 1900 | Simms:32 fisherman, La Perouse. | Ella (English), marries Simms33 (La Peruse). Stewart marries Walker (Wallaga Lake/Narooma). |

| 1920 | Ritchie marries Simms (who marries Ryan, fisherman, La Perouse). Son Ritchie with Mclennan (with Simms; fisherman, La Perouse, then Stewart: part fisherman, Wallaga Lake). | Ella marries Sutton (Roseby Park, Jervis Bay), related to Carter (Ardler (?), Timbery); fishing families from South Coast. |

| 1940 | Ritchie (fisherman) marries Thomas (then Mason, sailor) from Lake Tyres; subsistence and field work Carter; South Coast fishing families; 3 | Ella (Wreck Bay) marries Stewart (Nowra), related to Timbery Cooley (Carriage, Brierly) and Ella’s fishing. |

| Present | Mason; fishing, South Coast, related to Ella (Stewart, Cooley); 3 fishermen Carter, Stewart, Cooley, Brierly, | Mason (Nowra), marries Ella (Wollongong); 6 family members fish, 2 children fish. Related to fishing families; Timbery, Williams. |

Conclusion

Reflecting upon the experiences of this South Coast fishing case, one cannot help but ask how things might have been done differently. What

140can be learnt from the experience? By asking these questions, however, one is implicitly asking how, in other circumstance, might the fishing rights case on the South Coast of New South Wales have been won.

The determinations by the courts indicate that sufficient evidence was provided to have ‘established the ingredients necessary in law to succeed in a claim for native title in respect of a right to fish’ (Kirby 1994:33, his emphasis) although I believe a stronger case could have been made if more time had been available and we had had a better understanding of the requirements for proving native title.

Should I have undertaken the investigation, given the time constraints? One is inclined to say no, but it is one thing to stand on the professional high ground and contemplate what should be done and how others might do it, and it is another to be confronted by seven defiant and tense men who are about to face court and, in at least one case, a possible jail term. Nevertheless, there is a lesson to be learnt for the future. There is a greater advantage in having one’s ethnographic material in order before a case goes to court than in having to prepare it with the date of the court case fixed and imminent.

As it was, of course, none of these considerations may have influenced the outcome of the case greatly. The primary problem for the task of determining the presence or absence of a traditional right to fish was that the defendant ‘failed to provide sufficient evidence to prove that he actually had been exercising such a native title’ at the time of his arrest (Kirby 1994:33 his emphasis). It is absolutely clear that in future the defendants or the applicants must be in the witness box. The second issue is that more attention should have been given to the formal descriptions of the traditions and rights claimed and to the nature of the group that held them, as Kirby’s judgement makes clear.

As a final comment I should say, my original impression of the case was one of suspicion and misgiving with respect to the alleged traditional right to harvest abalone. But after tracing the historical experiences, family connections and geographic association of the families involved in the case, my view changed. One cannot but help being struck by the tenacity with which the tradition of fishing has been 141maintained throughout the historical experiences of the last 150 years on the South Coast. The evidence indicates that, in one of the most settled parts of Australia, with one of the longest histories of European settlement, there is a continutity of Aboriginal fishing practices and traditions traceable back to the earliest historic period.

The traditions and practice today are clearly different to those in existence before contact but moulded by and adapted to, rather than being washed away by, the great changes in social and environmental circumstances.

While many would perceive the process of historic change as considerably weakening, if not destroying the original traditions, I would argue that these historic experiences have in fact given fishing an added significance. They are the very core of present day tradtion and community association with that tradition is as strong today as ever. Further while any exclusive rights associated with the original tradition may have expired, commercial rights associated with the historic tradition have emerged in their place.

In conclusion, the resultant history and associations of people and fishing on the South Coast appears to have broad concurrence with the general propositions of native title (Brennan in Mabo v Queensland (No. 2): 50). The research reported on indicates that the defendants are indigenous people, the biological descendants of an indigenous group who exercised traditional and customary fishing rights on the South Coast of New South Wales. Although the customs of the group have changed over time, the tradition of fishing has not been abandoned.

The local Aboriginal community may find it difficult to understand how a member of a group whose native title rights can be proven in law and who has a demonstrable biological, historical, geographic and cultural association with that group can be acting outside the traditions of that group. The knowledge of their right to fish seems ingrained in the fishing families on the South Coast and contemporary pressures on this right seems to have created a stronger than ever determination to protect it. There appears to be a strong sense of injustice within the Aboriginal community in reaction to European perceptions and regulation of 142that right. The defendants see themselves as victims of a hostile social and commercial environment. They would argue that what was once a prehistoric economic activity (viz. the taking of abalone) and then a necessary historic component of their subsistence economy is now an illegal activity. History will judge: all one can do in the meantime is collect the relevant information as faithfully as possible and let the judicial system make its determination. In the meantime one can almost guarantee that resistance to and infringements of the common law will continue until the traditional right is recognised and steps are taken to accommodate it.

References

Attenbrow, V. 1976. Aboriginal subsistence economy on the far south coast of NSW, Australia. BA (Hons) thesis. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Bailey, G.N. 1975. The role of molluscs in coastal economies and the results of midden analysis in Australia. Journal of Archaeological Science 2: 45–62.

Bayley, W.A. 1965. History of the Shoalhaven. Nowra: Shoalhaven Shire Council.

Bell, J.H. 1956. The economic life of mixed blood Aborigines on the south coast of New South Wales. Oceania 26: 181–189.

Bowdler, S. 1995. Offshore islands and maritime explorations in Australian prehistory. Antiquity 69(266): 945–958.

Brennan, J. 1992. Mabo v the State of Queensland (No.2) June 1992 High Court of Australia, copy of the court’s reasons for judgment prior to formal revision and publication. Canberra: High Court.

Cane, S.B. 1987. An archaeological and anthropological investigation of the armament depot complex in Jervis Bay, NSW. Report to the Department of Housing and Construction, ACT. Canberra: Anutech. 143

1992a. Aboriginal fishing on the south coast of NSW. A report to Blake Dawson and Waldron, and the NSW Land Council.

1992b. Aboriginal fishing on the south coast of NSW: a supplementary report to Blake Dawson and Waldron, and the NSW Land Council.

1995. Nullarbor antiquity: archaeological, luminescent and seismic investigation on the Nullarbor Plain. A report to the National Estate Grants Program, Australian Heritage Commission, ACT.

1996. A coastal heritage, site gazetteer. Draft manuscript to the National Estate Grants Program, Australian Heritage Commission, ACT.

Cameron, S.B. 1987. An investigation of the history of the Aborigines of the far south coast of NSW in the nineteenth century. BLetts thesis, Australian National University.

Carter, J. 1984. Aboriginality: the affirmation of cultural identity in settled Australia. MA thesis, Australian National University.

Chalk, A. 1993. Mason v Triton—south coast fishing rights. Horowitz and Bilinsky, solicitors, Sydney; fax—23 October 1993.

Clugston, R. 1993. New South Wales v R.G. Mason, transcript no 181a/93. Sydney: Local Court Sutherland.

Colley, S. 1992. Archaeological evidence for abalone fishing by Aboriginal people on the NSW south coast. Report to Blake Dawson and Waldron.

Court of Appeal 1994. Mason v Triton, record sheet and determinations by C.J. Gleeson, P. Kirby and J.A. Priestly. File nos. Ca 40620/93: C112048/93.

Davidson, R. 1988. Whalemen of Twofold Bay. Canberra: Pirie Printers.

Dawn Magazine. 1954:3(11).

Eades, D. 1976. The Dharawal and Dhurga languages of the NSW south coast. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. 144

Egloff, B.J. 1981. Wreck Bay: an Aboriginal Fishing Village. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

1992. A draft report on the significance of coastal maritime resources for Aboriginal communities on the south coast of New South Wales to the South Coast Regional Aboriginal Land Council, and Blake Dawson and Waldron.

1993. Aboriginal fishing on the south coast of New South Wales. University of Canberra.

Frankel, D., D. Gaughwin, C. Bird and R. Hall 1989. Coastal archaeology in south Gippsland. Australian Archaeology 28:14–25.

Gaughwin, D. 1981. Sites of archaeological significance in the Westernport catchment. Ministry for Conservation, Victoria.

Goodall, H. 1982. The history of Aboriginal communities in NSW, 1909–1939. PhD thesis. Canberra: Department of History, Australian National Univeristy.

Kailola, P.J., M.J. Williams, P.C. Stewart, R.E. Reichelt, A. McNee, and C. Grieve 1993. Australian fisheries resources. Canberra: Bureau of Resource Science and the Fisheries Research Development Corporation.

Kirby, P. Court of Appeal: Mason v Triton. File nos. Ca 40620/93: C112048/93.

Lampert, R. 1971. Burrill Lake and Currarong: coastal sites in southern New South Wales. Terra Australis, 1. Canberra: Australian National University, ACT.

Lawrence, R. 1968. Aboriginal habitat and economy. Canberra: Department of Geography, Australian National University.

Legislative Assembly 1980. The first report from the select committee of the Legislative Assembly upon Aborigines, Part 1. Government Printer NSW.

Long, J. 1970. Aborigines and settlements: a survey of institutional communities in eastern Australia. Canberra: Australian National University Press. 145

McCallum, A.G. 1993. Dispute resolution mechanisms in the resolution of comprehensive Aboriginal claims: power imbalance between Aboriginal claimants and governments. Master of Laws, York University, Ontario.

McBryde, I. 1982. Coast and estuary: archaeological investigations on the north coast of New South Wales. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Mead, T. 1985. The killers of Eden. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

Nicholson, A. and S.B. Cane 1994. Pre-European settlement and use of the sea. Australian Archaeology 39:108–118.

Organ, M. 1990. A documentary history of the Illawarra and south coast Aborigines, 1770–1850. Aboriginal Education Unit, Wollongong University.

Pepper, P. 1980. You are what you make yourself to be. The story of a Victorian Aboriginal family 1842–1980. Melbourne: Hyland House.

Poiner, G. 1976. The process of the year among Aborigines of the central and south coasts of NSW. APAO 11(3):186–206.

Priestley, J.A. 1994. Court of Appeal: Mason v Triton, File nos. Ca 40620/93: C112048/93.

Read, P. 1988. The Hundred Years War. Canberra: ANU Press.

Roberts, P. and L. Katz 1994. Mason v Triton written submission of appellant for the Court of Appeal.

Rose, L. (ed.) 1976. A quiet revolution in Mogo—an account of an Aboriginal community. Unpublished manuscript.

Rose, D. 1990. Gulaga: a report on the cultural significance of the dreaming to Aboriginal people. Sydney: Forestry Commission, NSW.

Roseman, H. 1957. The voyage to the south seas by Jules S.C. Dumont D’Urville. Translated by Roseman. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. 146

Sayers, A. 1994. Aboriginal artists of the nineteenth century. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Scott, W.D. and Co. 1969. Report on a reconnaissance of means of Aboriginal advancement on the south coast of New South Wales. Sydney: Scott and Company.

Sullivan, M.E. 1984. A shell midden excavation at Pambula Lake on the far south coast of New South Wales. Archaeology in Oceania 19(1):1–15.

1987. The recent prehistoric exploitation of edible mussel in Aboriginal shell middens in southern New South Wales. Archaeology in Oceania 22:97–105.

Sutton, P. 1993. Aboriginal fishing rights on the New South Wales south coast. A review for Horowitz and Bilinsky, solicitors, Sydney, NSW.

Tindale, N. 1939. Field genealogies, held with the South Australian Museum Adelaide.

Thomson, S. 1979. Land alienation and land rights: a preliminary social history of south coast Aboriginal communities. BA (Hons) thesis. Armidale: University of New England.

White, D. 1987. Aboriginal subsistence and environmental history in the Burrill Lakes region, NSW. Unpublished BA (Hons) thesis. Canberra: Australian National University.

Wright, D. 1987. Aboriginal subsistence and environment in the Burrill Lake region, NSW. BA (Hons) thesis. Canberra: Australian National University.

Young, J. 1993. Judgment on Mason v Triton, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Common Law Division. Proceedings number 12048 of 1993.

1 This Act was the earliest regulatory Act referred to in the prosecution and in subsequent hearings. There appear to have been no other regulatory Acts between 1901 and 1980. The Coastal Water (State Powers) and the Coastal Waters (State Titles) Acts (Commonwealth) were enacted in 1980 to empower the States to make laws in relation to the seabed (also the Application of Laws (Coastal Sea) Act 1981). The Fisheries and Oyster Farms Act of 1935 was amended in 1989 (Fisheries Regulation 1989) (Robert and Katz 1994, Court of Appeal record sheet 1994).

2 Their case was argued by Blake Dawson and Waldron and later Horowitz Bilinsky.

3 Only one of the seven men was actually tried—Mason.

4 An eighth man, Clarke Chatfield was also involved. His family came to the South Coast from Dubbo in the 1960s and does not have an established history of fishing on the South Coast of NSW.

5 The issue of native title was virtually unheard of in July 1992. The High Court decision had just been made and copies of the determination could only be obtained from the High Court. There was no Native Title Act yet and there was little political debate about the consequences of native title. Nevertheless, the magistrate appeared troubled following the presentation of the archaeological and ethnographic evidence, suggesting his realisation of the significance of the issue at stake.

6 The Aboriginal people included Jean Carter, Nick Carter, Joanna Lonesborough, Laurel Carriage, Joey Carriage, Phyllis Carriage, Symalene Carriage, Stan Carriage, Jack Carriage, Keith Nye, David Nye, Gladys Nye, Danny Chapman, Kevin Mason, Ron Mason Snr and Jnr, Vivian Mason, Leo Ritchie, Betty Gill, Alan Brierly, Thomas Brierly and John Brierly.

7 Reserves notified on the South Coast included: Dalmeny (1861), Moruya (1875), four at Tuross Lake (1878–1880), Birroul Lake (1877), Tomakin (1884), Wallaga Lake (1891), Tathra (1893), Ulladulla (1892), two at Roseby Park (1900), Batemans Bay (1902), Narooma (1913), Jervis Bay (1917), Wreck Bay (1930s), four at Wallaga Lake (1906,1909,1931,1949) (Thomson 1979).

8 Recorded by N. Tindale at Wallaga Lake, 3/1/1939.

9 K. Stewart was born to ‘Governor’ Stewart and Bessie Kaine in 1872. He married Emily Walker (born 1974) on 15/7/1892 at Wallaga Lake.

10 V. Mason, oral history transcript 1992.

11 The earliest family members were James Pittman and Jane Nicholson, whose child John Pittman was born at Clyde River in 1859 (d. Batemans Bay 1915). Robert McCauley and Margaret Nicken had a daughter Margaret, born in the Shoalhaven in 1863 (d. Batemans Bay 1924). She married John Pittman and their daughter married Christopher Carriage, son of Eliza Spriggs and Christopher Carriage. Christopher and Eliza’s first child was born at Araluen in 1869.

12 Luderick (Paragus auratus) are a school fish that inhabit mangrove lined creeks and estuaries. They are now a commercial fish with an average national annual catch of around 500 tonnes (Kailola et al. 1993).

13 Oral history, A. MacLeod (1992); also Rose (1976).

14 Compilation of births, deaths and marriages by N. Cregan 1981–2, from the Clyde River and Batemans Bay Historical Society.

15 A photograph in DAWN, a magazine for Aboriginal people of NSW shows Reg MacLeod, Archie Moore and Sam Ardler fishing at Wreck Bay in 1954 (vol. 3, series no. 11).

16 A detailed account of the fishing interest and enterprises of the Nye family is given in Rose (1976).

17 Licences to fish became available in the 1940s. At the time, the licenses were valued at the equivalent of $5. Many people fished without a license and many of those with licences lost them as fees increased to $300–$500 through the 1960s. The Nyes maintained licences for four rowing boats and three nets: garfish, prawn and ‘beachfish’ (salmon and mullet).

18 1965: Frank Cooper—Browns Flat; Ernie Andy—Bega, Percy Davis—Batemans Bay; Dave Carpenter—Roseby Park; Walter Davis, Walter Brierly and Des Picalla—Bega. 1966: Arthur Thomas—Wallaga Lake; Percy Mumbulla—Tomerong; Sid Duncan—Nowra.

19 1965: Percy Davis, Batemans Bay; Charlie Parsons, Wallaga Lake; Herbert Chapman, Wreck Bay; Dave Carpenter, Roseby Park.

1990: Col Walker—Nowra.

1991: Amy Williams—Wreck Bay.

1992: Mary Duroux—Moruya; Barbara Roach—Moruya; Muriel Chapman—Batemans Bay; Leo Mason—Narooma; Shirley Foster; Brenda Ardler—Wreck Bay (no date).

20 An undated newspaper clipping reads ‘Salmon are running on the coast… 24 tonnes was netted off North Congo by the Nye and Jessop brothers. They dragged in over 100 tonnes for the last October, 56 tonnes in one haul and the cannery pays $700 a tonne’ (value of 56 tonnes—$39,200).

21 I dived with Keith one afternoon near Rosedale during this study. We both dived while his wife sat on the shore minding three children, observing our progress and being on hand to take any catch. Keith Nye found eight crayfish amongst the weed in a gathering landscape that appeared over fished and barren. He demonstrated excellent water skills, marine knowledge and gathering ability, comparable to the knowledge and skills I have seen in 18 years of working with indigenous people in the Western Desert.

22 Who caught a snapper on a piece of string as a child.

23 See the statement of Ron Mason in relation to Summons (2) before the Downing Street Local Court Thursday 23rd April 1992. page 2. The inspector took his flippers, bootees, wetsuit top and bottom, goggles, snorkel, knife, netbag and weight belt.

24 See McCallum (1993) for a comprehensive account of the power imbalance between Aboriginal claimants and Governments.

25 Transcript: Triton vs R. G. Mason, Downing Centre 1 March 1993.

26 Supreme Court of New South Wales Common Law Division: Mason v Triton: Coram J. Young: Hearing Sept. 1993, judgment Oct. 1993: pages 1–35.

27 The source referred to by Justice Young is quoted as Crocombe’s Land Tenure in the Cook Islands (Oxford University Press 1964).

28 Account of Supreme Court ruling as summarised in Kirby P. Supreme Court of New South Wales, Court of Appeal, Mason v Triton, August 1994:4.

29 Court of Appeal Record Sheet: File no/s: Ca 40620/93; CT 12048/93: Gleeson C. J., Kirby P., and Priestley J. A. August 1994.

30 The abalone were probably worth between $1,000 and $2,000.

31 See section 5. of Cane 1992a for K. Mason and Section 1. of Cane 1992b for the defendant, R. Mason. The relationship was also discussed in cross examination and purposefully summarised for the Local Court (Table 2).

32 Paddy Simms.

33 Tinnie Simms (woman).