10

Gapu Dhulway, Gapu Maramba: conceptualisation and ownership of saltwater among the Burarra and Yan-nhangu peoples of northeast Arnhem Land

Although a considerable body of literature now exists on aspects of customary marine tenure and/resource usage in the Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region of northeast Arnhem Land,1 little has been written about the ways in which the local Burarra and Yan-nhangu peoples actually conceptualise saltwater and articulate concomitant relations of sea ownership. Ultimately, and perhaps inevitably, this lack of focus upon indigenous conceptions of saltwater has resulted in the promulgation and uncritical acceptance of certain ethnographically inaccurate representations of regional sea tenure patterns and principles. Foremost among these (mis)representations is the widely held view that traditional patterns of land and sea tenure in this region are, to all practical intents and purposes, identical (cf. Davis 1984a; Davis and Prescott 1992; Cooke 1995:9–10; Keen 1984–85:433; see also Northern Land Council 1992:1, 1995:2,4–5). Deriving from this perspective are the equally erroneous, if often less explicitly articulated, assumptions to the

248effect that saltwater elements of local estates constitute little more than spatially contiguous offshore projections of relatively well-defined land areas and, further, that for the purposes of estate ownership and delineation, saltwater is indistinguishable from other contiguously located marine features such as sites and seabed.2

In order both to counter such views and to contribute to the development of a more comprehensive ethnographic base for future work on customary marine tenure in this region, the current paper presents the first detailed account of Burarra and Yan-nhangu concepts of saltwater and its ownership.3

Burarra and Yan-nhangu

The Burarra and Yan-nhangu peoples4 traditionally own adjoining territories on and near the Arafura Sea coast of northeast Arnhem Land. Broadly speaking, Burarra territory extends inland for varying distances from points west of the Blyth River to Cape Stewart and nearby islands in the east, while Yan-nhangu country encompasses most of the Crocodile Islands group (Figure 10:1). Despite marked differences in language and social organisation—Burarra speak a prefixing non-Pama-Nyungan language (cf. Glasgow and Glasgow 1985) and subscribe to an Aranda-like system of kin classification (Hiatt 1965), whereas

249Yan-nhangu speak a dialect of the suffixing Pama-Nyungan Yolngumatha language (Zorc 1986) and classify kin asymmetrically (Keen 1994)—the two peoples characterise themselves as ‘close’ (B: yi-gurrepa; Y: galki)5 and maintain high levels of sociocultural interaction (including intermarriage).

Local estates (B: rrawa; Y: wanggala) within both domains (Stanner 1965) are identified with, and owned by; small, exogamous patrifilial groups (Bagshaw 1991c, 1995a; Keen 1994). Called yakarrarra by Burarra and baparru by Yan-nhangu,6 each such group bears a proper name and is affiliated to one or another of two named, exogamous patri-moieties (B: Yirrchinga and Jowunga; Y: Yirritja and Dhuwa). In all cases, estates and their associated religious resources (madayin)7 are believed to have been created by, and inherited from, eternal, moiety-specific supernatural entities known as wangarr, who shaped the world in the far distant past (baman). Consubstantial identification with a particular wangarr, or group of wangarr, and possession of related sacra (cf. Hiatt 1982:14) constitute the principal ontological

250and material bases of estate ownership. Collectively, the members of each yakarrarra or baparru are referred to as ‘country leaders’ (B: rrawa walang) or ‘country holders’ (Y: wanggala watangu) in respect of their estates.

Complex ritual connections based on the journeys and activities of wangarr link different estates and estate-owning groups within and between domains (Hiatt 1965; Keen 1978, 1994; Davis 1984a). Variously expressed in terms of shared madayin and concomitant notions of shared identity, and/or immutable kinship relations between estates (e.g. sibling, spouse and MM-fDC/ZDC relationships), such mythologically inscribed linkages confer a range of collectively held rights and interests in the estates of other groups (see Bagshaw 1995a:11–12 for details).

Significant individual rights and interests in other estates are also conferred by actual kinship relations. For Burarra and Yan-nhangu alike, the most important kintypes in this regard are ZC and ZDC, with persons in the former category being termed ‘breast-related group’ (B: ngamanbananga) or ‘breast possessors’ (Y: ngamani watangu) and those in the latter ‘MM-related group’ (B: aburr-mari) or ‘MM possessors’ (Y: wayirri watangu). Among other things, initiated males in both categories are charged with the custodial care of their maternal and MM estates and the performance of associated ceremonial duties (Hiatt 1965; Keen 1991; 1994, Bagshaw 1995a).8

251

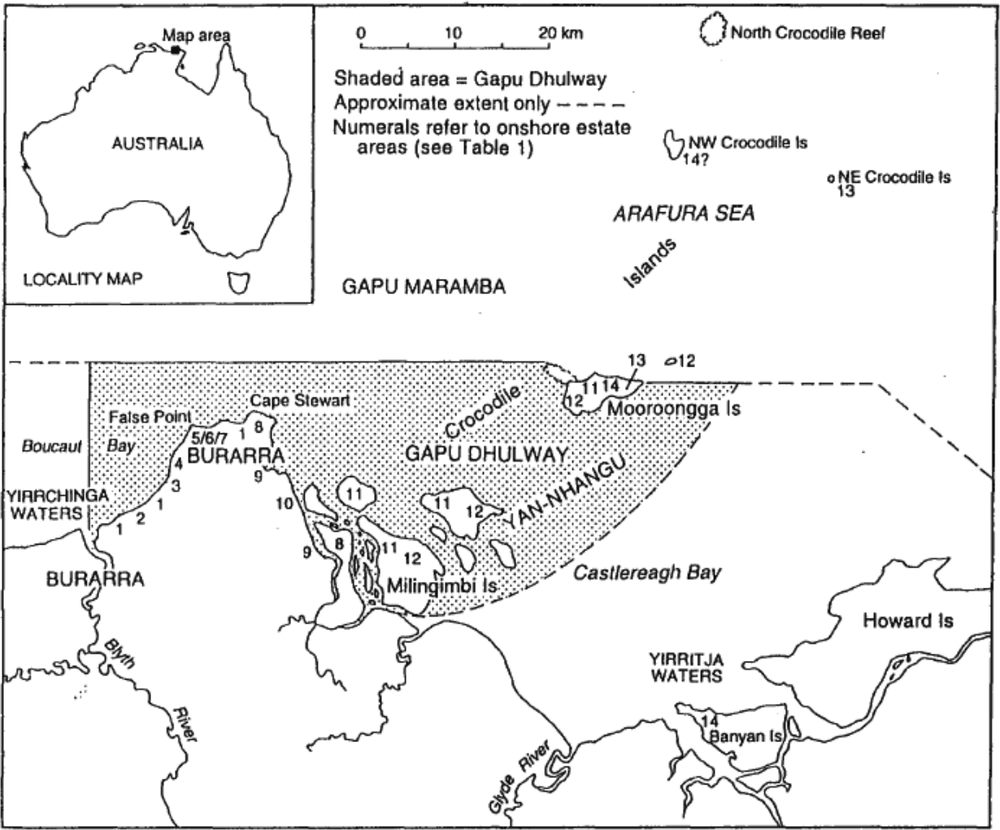

Figure 10:1 Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region

Coastal estates

Some eleven Burarra yakarrarra and four Yan-nhangu baparru are identified with coastal estates in the immediate Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region.9 Of these, three Burarra groups (or two, according to

252at least one of my principal informants) are often considered to jointly own a single estate, while another is extinct.10 Like the latter, all of the remaining yakarrarra and baparru are identified with distinct estates. The general locations of their onshore territories are shown on Figure 10:1. The proper names of the relevant estate-owning patrifilial groups, together with their patri-moiety affiliations, approximate populations and socio-linguistic affiliations are set out in Figure 10:2.

Burarra and Yan-nhangu coastal estates incorporate both onshore and offshore areas.11 In the Burarra domain, onshore estate areas usually consist of a single mainland tract (sometimes with adjacent small islands) encompassing numerous named sites (B: rrawa).12

In contrast, all of the island-centred Yan-nhangu estates consist of two or more geographically disparate tracts and associated sites

253(Y: wanggala).13 In both domains, tracts identified with neighbouring coastal estates are usually partially demarcated by environmental ‘boundary markers’ (B: rrawa gu-gorndiya [‘country it-cut self’]; Y: wanggala gulthana [‘country cut’]) such as vegetation, beaches and gradients (cf. Davis 1984a:60–4; Keen:1994:105). and are generally (but not invariably) owned by yakarrarra or baparru affiliated to opposite patri-moieties. The latter circumstance has prompted some observers to speak of a ‘checkerboard’ (Davis 1984a:43; Williams 1986:77) pattern of alternating moiety affiliations among estates on the coast of northeast Arnhem Land. Quantitative data compiled by Davis (1984:106–10) indicate that the majority of Burarra and Yan-nhangu coastal estates in the immediate Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region have total land areas (i.e. land above high-water mark) of between 13 and 53 sq.km.14 Offshore estate areas in the Burarra and Yan-nhangu domains consist either of permanently submerged or tidally exposed sites and adjacent seabed, on the one hand, or, on the other, of sites, seabed and the surrounding saltwater. As described in greater detail later in the chapter, this previously unrecorded distinction in the constitution of coastal estates (i.e. inclusive or exclusive of saltwater) is closely linked to local conceptions of the sea as two separate bodies of water, that is, as physically and mythologically distinct zones of inshore and open sea water.

Marine sites (B: rrawa gu-bugula; Y: wanggala gapunga) include specific topographic features such as rocks, reefs, sandbars and mudbanks, all of which are explicitly construed as ‘land’. Like onshore sites, these features are differentially associated with a variety of wangarr and are interpreted as focal points of noumenal activity and/or presence (cf. Keen 1984:433). Whilst some marine sites can be approached by persons irrespective of age or gender, others are only accessible to initiated men.

254

Figure 10:2 Burarra yakarrarra and Yan-nhangu baparru with coastal estates

| No.1 | Name | Patri-moiety | Population2 | Affililiation |

| 1 | Gamal | Yirrchinga | 91 | Burarra/Yan-nhangu |

| 2 | Guwowura | Jowunga | 11 | Burarra |

| 3 | Yemara | Jowunga | 4 | Burarra |

| 4 | Bindararr | Yirrchinga | 10 | Burarra/Yan-nhangu |

| 5 | Maljikarra3 | Jowunga | 114 | Burarra |

| 6 | Marrawundi | Jowunga | Burarra | |

| 7 | Balwarra | Jowunga | 12 | Burarra |

| 8 | Barlaytjina | Yirrchinga | 10 | Burarra |

| 9 | Warrawarra | Yirrchngga | 60+ | Burarra |

| 10 | Gaburrburr | Jowunga | 0 | Burarra |

| 11 | Gurryindi5 | Dhuwa | 36+ | Yan-nhangu |

| 12 | Ngurruwula | Yirritja | 6 | Yan-nhangu |

| 13 | Malarra | Dhuwa | 34 | Yan-nhangu |

| 14 | Gamalangga | Dhuwa | 34+ | Yan-nhangu |

Notes to Table

1. Numerals refer to onshore estate areas; see Figure 10:1.

2. Approximate 1996 population.

3. The Maljikarra, Marrawundi and Balwarra yakarrarra are generally considered to be joint owners of a single estate.

4. Combined 5 and 6.

5. Although Gurryindi is a Dhuwa moiety baparru, many of its members are personally affiliated to the Yirritja moiety as a consequence of intra-moiety marriages.

255Others still, are regarded as extremely dangerous (B: gun-bachirra; Y: mardangarrangarr or rrathangu) and are carefully avoided. Details of numerous marine sites in the Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region have been recorded in the course of sea-closure and /or site-protection research (see Bagshaw 1979, 1991a, 1991b; Davis 1981; Dreyfus and Dhulumburrk 1980; and Meehan 1983).

Seabed, which is locally referred to as ‘earth’ (B: jel; Y: munhatanga), primarily includes all tidally exposed areas around and between marine sites. As previous authors have noted, such areas are also explicitly regarded as ‘land’, with the Lowest Astronomical Tide (LAT) level effectively delineating the exploitable limits thereof (cf. Davis 1984a:78; Davis and Prescott 1992:50). Although such ‘land’ is also generally thought to underlie continuously inundated inshore areas, Burarra and Yan-nhangu have no elaborated concept of permanently submerged seabed in deep water zones.

According to Davis (1984a:60–7; Davis and Prescott 1992:46), estate-specific offshore areas in this region are demarcated in much the same ways as, and often with reference to, onshore areas. Watersheds, river channels and onshore vegetation are said to be of particular significance in this regard (Davis 1984a). While my own data partly confirm this observation, they also clearly show that whereas an estate’s marine sites and seabed are usually contiguous with its onshore area(s) and are generally interpreted as spatial extensions thereof, saltwater elements invariably extend well beyond the lateral onshore boundaries of the relevant estates (see section on saltwater ownership and moiety-specificity for further details).

With respect to the northern (i.e. seaward) extent of marine sites and seabed, one of my principal informants unequivocally maintains that Burarra estates do not incorporate such elements beyond the recognised junction of the two bodies of inshore and open sea water referred to above. (Specific details of this junction are given in the following section). This observation is fully consistent with the marine site survey work I have undertaken in and around the Boucaut Bay—Cape Stewart area since 1979 (see Bagshaw 1979, 1991a, 1991b). Within 256the Yan-nhangu domain, however, at least three (and possibly four) estates include sites and/or seabed beyond the recognised confluence of inshore and open sea waters.15 It should be added that the results of a recent aerial survey of major marine sites to the north of Murrungga (Mooroongga Island) strongly suggest that no estate-specific Yannhangu sites and seabed are located beyond the outermost reefs of Gunumba [1] (North Crocodile Reef).16

In their concerns to represent the regional marine environment as a locus of diverse, site-specific wangarr activity and/or a key resource base most previous studies have perfunctorily conflated sites and seabed with saltwater, construing all three as indivisible elements of ‘sea country’ (cf. Northern Land Council 1992; Cooke 1995) Whilst undoubtedly justified at a broad socio-ecological level, this conflation has nevertheless consistently (if unwittingly) obscured the distinctive cultural status of saltwater, both in metaphysical terms17 and in terms of its traditional ownership. I shall therefore devote much of the balance of the paper to a detailed consideration of this status.

257

Gapu dhulway, gapu maramba

Burarra and Yan-nhangu view the Arafura Sea in the immediate Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region as two distinct bodies of saltwater (B: bugula gunbachirra [‘water bitter’]; Y: ganitjirri rrathangu [‘water bitter’]). Commonly termed gapu dhulway and gapu maramba (gapu being a wider Yolngu-matha noun for water18 which is also used in this particular context by Burarra and Yan-nhangu), these two bodies of saltwater respectively comprise all shallow (B: gun-delipa; Y: gulkurungu), turbid (B: burul; Y: ritji) inshore waters within the region and all deep (B: gu-lupa; Y: dhulupurr), clear (B: rrewarrga; Y: garkuluk) waters of the open sea.19

Like other mythologically related waters to the east (see below), gapu dhulway and gapu maramba are both construed as moiety-specific noumenal entities (wangarr) endowed with creative power (marr) and active agency—attributes which are deemed to be manifest in their movement, sound and changing form (cf. Davis and Prescott 1992:52).20 Such natural phenomena are, in fact, themselves interpreted as quintessential aspects of the two wangarr and are accorded highly specific ritual names known as bundurr (see below). At a more colloquial (and also more general) level, the dynamic form and nature of the gapu dhulway and gapu maramba wangarr are underscored and affirmed

258through the use of anatomical referents for various saltwater features.21 Examples of such usages include ‘knees’ (B: menama gu-jirra; Y: bun) for waves, ‘teeth’ (B: rrirra gu-jirra)22 or ‘mouth’ (B: ngana gu-jirra; Y: dha) for the shoreline edge of the sea, ‘abdomen’ (B: gochila gu-jirra; Y: gulun) for moderately distant waters [i.e. relative to land]), ‘chest’ (B: gumbach gu-jirra; Y: miriki) for distant sea and ‘lower back’ (B: barra gu-jirra; Y: mundaka) for far distant waters. In a similar conceptual and linguistic vein, the constant crashing of beach surf and of inshore waves is described as saltwater ‘habitually speaking’ (B: gu-weya gu-workiya; Y: bayngu wanga). In like manner, the more distant (and therefore less clearly audible) waters of the open sea are said to perpetually ‘rumble’ or ‘growl’ (B: gumurrijinga gu-workiya; Y: bayngu murriyun).23 Finally, laterally flowing bodies of saltwater (see below) are usually described as ‘habitually walking’ (B: gu-bamburda guworkiya; Y: bayngu garama).

The designations dhulway and maramba are locally characterised as baparru names (cf. Shapiro 1981, Williams 1986; Keen 1994, 1995), meaning (in this context at least) that they are regional-level appellations connoting both the geographical horizons and distinctive cosmological identities (including patri-moiety affiliations) of the two saltwater wangarr. To the extent that gapu dhulway is exclusively identified with the Yirritja (called Yirrchinga in Burarra) patri-moiety and gapu maramba with the Dhuwa (called Jowunga in Burarra) patri-moiety, the appellations dhulway and maramba appear to correspond to the broad, moiety-specific names manbuynga and rulyapa as used in respect of the same and other similarly classified waters by peoples in the Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island) region (cf. Ginytjirrang Mala/ADVYZ 1994; Northern Land Council 1995).24 Although versions of these

259latter names (i.e. manbuyma and/or manbuynga and ruljaparr) are also employed by Burarra and Yan-nhangu, their meanings and usages are generally more restricted (see below).

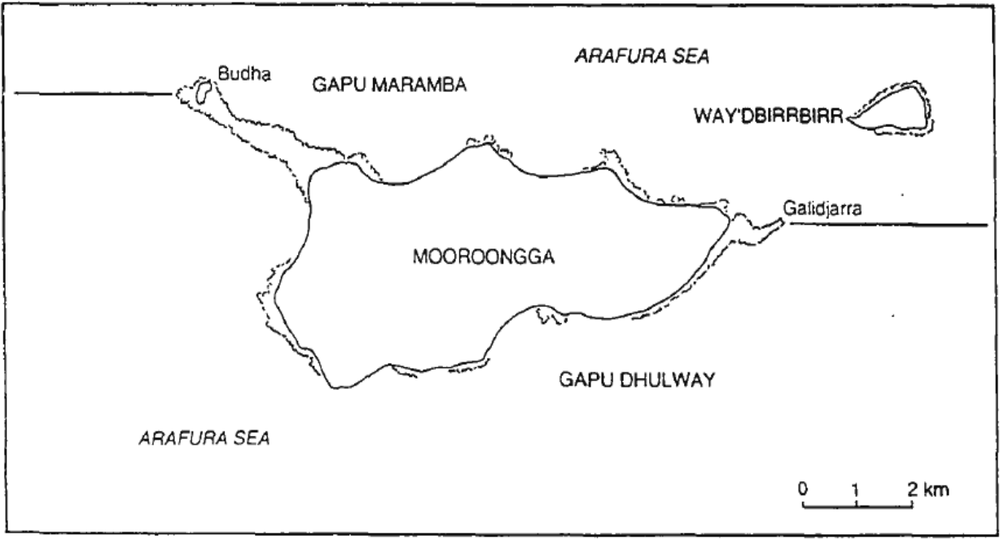

Gapu dhulway is held to flow on an east-west axis from points in the general vicinities of Mooroonga Island (Murrungga; to the northeast) and the mouth of Darbilla Creek (southeast) to the mid-channel of the mouth of the Blyth River (Angartcha wana ‘big river’, west). Surface bubbles (B: mun-janajana; Y: dhangngurr or mulmul) in or near the Blyth River mouth are said to indicate the western limit of this body of water.25 Despite marked seasonal fluctuations in the degree and extent of inshore turbidity, its permanent seaward limit—and thus also its boundary with gapu maramba—is defined as a conceptual line projecting east and west from two mythologically inscribed locations in the immediate vicinity of Murrungga. These locations are Galidjarra reef (east) at co-ordinates 11.55.45S, 135.07.43E and Budha reef (west) at co-ordinates 11.54.34S, 135.01.46E (see Figure 10:3). The physical junction of the two bodies of water along this plane is characterised in Burarra as bugula galamurrpa gubirri-gataji (‘water[s] / meeting / they two to it-there standing in line’) and in Yan-nhangu as balaytjini dhamanarpana ganitjirri (‘they two/ together/ water[s]’). All saltwater north of this recognised confluence is construed as gapu maramba.

260

Figure 10.3 Junction of gapu dhul way and gapu maramba at Mooroongga Island

Gapu maramba (which is also colloquially known in Yan-nhangu as gapu mundaka ‘lower back of the water’; i.e. distant sea) is believed to commence at an unspecified location far to the west of the Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region and to flow east to Gukurda, a reef near Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island) owned by the now extinct Gunbirridji baparru. Still further to the east the same body of water becomes known as wulamba and is primarily identified with the Djapu baparru (cf. Berndt 1951, 1955; Williams 1986).26 From a Burarra and Yan-nhangu perspective, the western waters of gapu maramba include seas in the vicinity of the Goulburn Islands (175km WNW of Murrungga) and Croker Island (270km WNW of Murrungga). The far distant northern waters of gapu maramba, which are also variously termed wulan, gurri and dhawal,

261are said to extend to the shores of the island of New Guinea, known to Burarra and Yan-nhangu as Bapua (cf. Ginytjirrang Mala/ADVYZ 1994:5). The approximate horizons of gapu dhulway and gapu maramba within the immediate Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region are shown on Figure 10:3.

In both cases, important mythological linkages are held to exist with other waters to the east. These latter are, in fact, explicitly construed as direct physical and metaphysical extensions of gapu dhulway and gapu maramba and, as such, are often respectively characterised as ‘one water’ (B: bugula gu-ngardapa; Y: ganhaman gapu). Gapu dhulway is thus connected to Yirritja moiety inshore waters in the vicinities of Darbilla Creek (Mildjingi baparru), Howard Island (Wobulkarra baparru) and Cape Arnhem (Wangurri) baparru),27 while gapu maramba is, as previously indicated, similarly connected to Dhuwa moiety open sea waters near Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island, Gunbirridji baparru) and the Yirrkala region (Djapu baparru).28 In effect, therefore, local yakarrarra and baparru identified with either gapu dhulway or gapu maramba form part of two much wider, moiety-specific sets of saltwater-owning groups. At the broadest social and geographical levels, it is these maximally inclusive sets which collectively hold what may be termed ‘communal title’ in respect of Yirritja and Dhuwa waters (cf. Ginytjirrang Mala/ADVYZ 1994; see also below).

Gapu maramba is further characterised as the mother’s brother (B: jachacha; Y: gaykay) of inshore waters around Howard Island, to which

262(according to local mythology) it carries rrambala, the mangrove-wood wangarr most closely identified with the latter area. Although mutual kinship statuses are less commonly ascribed to gapu maramba and gapu dhulway (but see Addendum), the two are certainly believed to interact—most notably in the context of tidal action, which is thought to result (in part at least) from both entities ‘knocking’ each other forward (incoming tide) and back (outgoing tide).29

Like other wangarr in the Burarra and Yan-nhangu cosmos, each body of water is also associated with a set of more specific ritual names (bundurr) connoting its distinctive features and/or characteristics (cf. Keen 1994:103–4). Jawurrjawurr (sound of inshore water), bulurrbulurr (fast, tumbling waves), nyirdawuku (mid-section of waves), manbuyma (high waves also pronounced manbuynga), gularri (rough, bubbling sea), gulaynyingga (whitecaps) and makalama (cold sea breeze) are among the many bundurr associated with gapu dhulway. Some of the bundurr associated with gapu maramba bundurr include dhawunuwunu (far distant sea), balawurru (high waves), mirikindi (sea horizon), ruljaparr (distant open sea), jingamurriyun (sound of distant sea) and dhangarrngarr (sea ‘biting’ land).

Publicly invoked in certain ceremonial contexts,30 saltwater bundurr names figure in ‘coastal’ (as distinct from the ‘hinterland’) verses of song-cycles (manikay) such as Wulumungu (associated with gapu dhulway) and Murrungun (also called Malarra after the baparru of the same name; associated with gapu maramba).31 Like the related designs

263depicted in sacred and secular art, these names and song cycles constitute some of the basic religious resources (madayin) of the various patrifilial groups (B: yakarrarra; Y: baparru) most widely considered to own either gapu dhulway or gapu maramba. Indeed, identification with, and possession of, such resources (particularly the relevant bundurr) is locally construed as a primary index of saltwater ownership.

Consubstantial identification and associated possessory rights in saltwater

For Burarra and Yan-nhangu, the customary ownership32 of gapu dhulway, gapu maramba and associated madayin is primarily predicated upon consubstantial identification with the relevant saltwater wangarr. Articulated at both the individual level and the level of the yakarrarra or baparru, such identification is principally mediated by patrifiliation.33 In this connection, members of most of the yakarrarra and baparru generally considered to own either gapu dhulway or gapu maramba explicitly state that they were begotten by, inter alia, their human genitors (B: ngun-anya nguna-bokamarra ‘to me-father / to me-begat’; Y: ngarrana walkur milaynha ‘to me / male line / begotten-procreated’) and the body of water which forms part of their respective estates (B: bugula nguna-bokamarra ‘water / to me-begat’; Y: gapu ngarrana bukmana ‘water / to me / begat’).34 Thus designated as ‘rightful holders’ of the relevant

264saltwater wangarr (B: wangarr an-/jin-gurrimapa; Y: wangarr watangu) and its associated ritual names, such individuals are sometimes given saltwater bundurr (see above) as personal names and may be addressed or referred to as ‘(salt)water’ (B: ‘bugula’; Y: ‘gapu’).35

For the persons and groups so related, consubstantial identification confers a particular range of inalienable possessory rights in gapu dhulway or gapu maramba. Collectively constituting the indicia of customary ownership, these rights are corporately held, though for the most part individually exercised, by the members of each of the appropriate yakarrarra and baparru. In cases where more than one yakarrarra or baparru are consubstantially identified with the same body of water, the relevant possessory rights are jointly held (i.e. held in common) by all of the patrifilial groups concerned.

Although, as previously indicated, other groups to the east of the Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region also hold similar rights in saltwater and thus form part of wider constellations of ‘title holders’ in respect either of Yirritja and Dhuwa waters, it is only the members of the relevant Burarra and Yan-nhangu patrifilial groups who are considered to hold and exercise all local-level possessory rights in gapu dhulway and gapu maramba within the area under consideration.

Following Sutton (1996 and pers.comm.), I group local-level possessory rights in gapu dhulway and gapu maramba into three broad categories: (1) identification and representation, (2) access and (3) use.

265In that same author’s (slightly amended) terms, the rights within each category include:

(1)(a) The right to publicly assert that the body of water concerned is part of one’s own estate.

(b) The right to speak for and about that body of water (and its associated religious resources) as property (i.e. to represent it in both senses).

(c) The right to hold, assert and concretely exercise responsibility for the spiritual and physical welfare of that body of water.

(d) The right to perform (as distinct from merely participate in) rituals related to that body of water.

(2)(a) The right to be asked for permission to enter the specified body of water.

(b) The right to control movement within or around that body of water.36

(c) The right to enjoy unfettered access to that body of water (subject to the observance of customary restrictions upon gender, site avoidance, etc.).

(3)The right to hunt (turtle, dugong, rays, etc.) and fish on and in that body of water.

While many of the rights enumerated here (notably 1c, 1d, 2b, 2c and 3) are also extended to persons who are not themselves members of the yakarrarra and baparru considered to own saltwater (see above), it is only the latter who possess the full complement.37 This is most clearly

266apparent in relation to those rights (e.g. 1a, 1b and 2a) which expressly allude to the ontological basis of identification with saltwater (i.e. consubstantiality). Apart from certain very limited exceptions (as in 1c, 1d, and 2b), such rights are the exclusive preserve of the owning yakarrarra and baparru.38

Full possessory rights may also be claimed or asserted by members of patrifilial groups other than those considered to be consubstantially identified with the relevant saltwater wangarr. In one such case discussed later in the paper, a senior Yan-nhangu man asserts that his own baparru holds exclusive rights of ownership in respect of gapu maramba as a result both of its identification with certain non-saltwater religious resources (madayin) believed to be shared with a now extinct group of saltwater owners and the fact that further mythological connections link its estate to particular sites located within gapu maramba. This claim, and the bases on which it is made, are, however, vigorously

267contested by members of another patrifilial group who maintain (with general public concurrence) that they themselves are the sole owners of gapu maramba by virtue of consubstantial identification.

It may also be the case that joint ownership of a sea-specific song-cycle (i.e. of a song-cycle which is also owned by consubstantially identified groups), together with a direct identification with other closely related wangarr and the possession of a land estate directly abutting the relevant body of water, are regarded as sufficient conditions for the members of a non-consubstantially identified patrifilial group to hold and exercise full possessory rights in saltwater. I say ‘may’ because it is not entirely clear to me whether one of the groups generally recognised as a co-owner of gapu dhulway is consubstantially identified with that body of water or whether it is merely associated with inshore water on the terms just described (see below for further details).

Saltwater ownership and moiety-specificity

Earlier in the paper I observed that gapu dhulway is exclusively identified with the Yirritja (called Yirrchinga in Burarra) patri-moiety and gapu maramba with the Dhuwa (called Jowunga in Burarra) patri-moiety. Consistent with the totalising logic of moiety affiliation and differentiation which informs all aspects of Burarra and Yan-nhangu social, local and religious organisation, each body of water is owned by correspondingly identified yakarrarra and/or baparru (i.e. gapu dhulway is owned by Yirritja moiety patrifilial groups and gapu maramba by Dhuwa moiety groups [or rather, as I indicate below, a single Dhuwa moiety group]).

It follows from this moiety-specific pattern of ownership that no Yirritja patrifilial groups own the open sea water (i.e. gapu maramba) abutting their terrestrial estates and no Dhuwa groups own similarly situated inshore water (i.e. gapu dhulway). In actual terms, the former situation applies only to the Ngurruwula bapurru, the sole Yirritja moiety group with an estate tract north of the confluence of gapu 268dhulway and gapu maramba (see above, also Figure 10:1). The latter situation, however, variously applies to the An-mujolgawa Guwowura, Yemarra, Maljikarra, Marrawundi, Balwarra and Gaburrburr yakarrarra, all of which possess land estates directly abutting inshore water. It also partially applies to the Gurryindi, Gamalangga and Malarra baparru, being groups with some estate tracts abutting gapu dhulway and others adjoining gapu maramba (see Figure 10:1).39 Contrary to much of the literature, therefore, the so-called ‘checkerboard’ pattern of alternating moiety affiliations typically associated with neighbouring onshore estate areas (Davis 1984a, Williams 1986) is not transposed onto saltwater.40 Instead, a much broader, regional-level moiety dichotomy is used to define and distinguish two physically and metaphysically discrete bodies of water.

Moreover, since gapu dhulway and gapu maramba are both conceived of as discrete, spatially continuous regional entities (see above), the fact that they are differentially identified with yakarrarra and/or baparru of a single (i.e. corresponding) moiety only means that the saltwater associated with each such group’s estate invariably extends well beyond the lateral horizons of its (i.e. the group’s) ‘land’ territories. This is because the water concerned also abuts or covers the land and seabed owned by neighbouring (or at least proximate) groups of the opposite moiety. The immediate question, then, is: which patrifilial groups are identified with either gapu dhulway or gapu maramba?

Saltwater yakarrarra and baparru gapu dhulway

Although some individuals broadly characterise gapu dhulway as ‘shared (or common) water’ (B: bugula gun-ganawa; Y: gapu dhamanar)

269conjointly owned by all Yirritja moiety groups within the region, the most detailed local exegeses I have recorded indicate that this body of water is specifically identified with, and exclusively owned by, certain patrifilial groups which also jointly own the Wulumungu manikay, the regional song-cycle most closely associated with inshore water (see above).41

Respectively named Gamal, Bindararr, and Ngurruwula, these ‘common manikay’ (B: manikay mun-ganawa; Y: manikay dhamanar) groups variously hold onshore territories in the Burarra (Gamal and Bindararr) and Yan-nhangu (Ngurruwula) domains. (By way of acknowledging their joint ownership of the Wulumungu manikay and, indeed, the language in which this song-cycle is phrased, members of the Gamal and Bindararr yakarrarra often describe themselves as Yannhangu-speakers.) Since the three groups are also collectively known as Walamangu (a semantically related near-homophone of Wulumungu [Sutton pers.comm.]),42 the inshore water with which they are identified is often referred to as ‘Walamangu water’ (B: Walamangu gun-nika bugula; Y: nhan’kubi Walamangu gapu).

270There appears to me, however, to be some uncertainty as to whether members of the Bindararr yakarrarra are consubstantially identified with that body of water, or whether their status as co-owners of inshore water actually derives from a combination of other factors such as their joint possession of the Wulumungu manikay, their identification with certain wangarr deemed to be closely associated with saltwater43 and the physical location of their offshore ‘land’, which both adjoins Gamal territory and is overlain by gapu dhulway.44 (In this last connection, the Bindararr group and its ‘land’ holdings [including onshore terrtitory] are typically described as being situated in the immediate vicinity of saltwater or, to be more precise, on the ‘flank of the land/coast’ [B: rrawa gerlk gu-jirra; Y: gali gurridhay]—a description which is also applied to the Gamal and Ngurruwula groups and their respective terrestrial estates). At the local level, though, the issue of Bindararr consubstantiality with saltwater seems to be rarely canvassed or even considered. It is certainly not a source of evident contention among the Walamangu groups.

271Walamangu (and, in particular, Gamal and Ngurruwula) identification with gapu dhulway is explicitly enunciated in saltwater verses of the Wulumungu manikay. In one such verse, for example, inshore waters in the vicinities of Milinginbi (i.e. Milingimbi; Ngurruwula baparru) and Bunbuwa (Gamal yakarrarra)45—that is to say, waters at or near the eastern and western extremities of gapu dhulway—speak as localised aspects of a single wangarr, variously and inclusively identifying themselves as Gulalay (a regional-level appellation applied only to Ngurruwula and Gamal), as Mandjikay (a much broader, predominantly Yolngu totemic aggregate to which Ngurruwula and Gamal belong) and as Walamangu.46 As the following excerpt47 from this particular verse illustrates, the two waters also specify some of their bundurr names which are indicated by asterisks.

Transcription

272

[…] gulalay / mandjiridjirra / ngalipi / walamangu

Gulalay / Mandjikay / we two / Walamangu /

‘mangrove-pod group’/ ‘sandfly group’/ inclusive

manbika / nyirdawuku* / gulaynyingga* / bulurrbulurr* /

high waves / mid-section of waves / whitecaps / fast, tumbling waves /

stylised form of manbuynga*

djalnyirr* / galkalmiyangu / milinginbi / bunbuwa /

lines of foam bubbles / waves heaping shells / Milinginbi area/ Bunbuwa area /

i.e. Milingimbi)

galarrawuya* / dhalarrbunungu.

I halt here / (sea) breaking on shore.

Translation

‘(We are) Gulalay and Mandjikay, we are both Walamangu. (Our) rough waves heap beach shells in the Milinginbi area and the Bunbuwa area, where my (i.e, the Bunbuwa area) waters terminate, breaking onto the shore’.

While localised stretches of gapu dhulway (cf. references to Milingimbi and Bunbuwa area waters in the Wulumungu verse just quoted) are ultimately conceptualised as aspects of a single, spatially continuous and collectively owned entity, the fact that such geographically disparate waters are differentially associated (be it mythologically and/or physically) with particular Gamal, Bindararr and Ngurruwula sites and/or areas means that they are also frequently characterised as distinct, estate-specific features. Accordingly, saltwater in the general area called Bunbuwa (common name) or Dhawukula (bundurr name) is typically identified with the Gamal yakarrarra, while inshore waters in the Munungurrumba (common name) or Marrambirpirl (bundurr name) area and the Walamarrana (common name) or Girrkirra (bundurr name) area are usually respectively identified with the Bindararr yakarrarra and the Ngurruwula baparru.48 Available evidence suggests

273that there may, in fact, be some environmentally-referenced delineation of the waters associated with such estate-specific areas. In this regard, at least one Burarra individual has told me that frothy surface bubbles (B: mun-janajana; dhangngurr or mulmul) mark the junction of waters overlying the Gamal and Bindararr offshore areas.

Saltwater yakarrarra and baparru gapu maramba

According to my principal Yan-nhangu and Burarra informants (a Malarra man and his Gamal wife), gapu maramba is directly identified with, and currently solely owned by, Malarra, a Yan-nhangu Dhuwa moiety baparru which possesses the Murrungun (also known as Malarra) song-cycle associated with the open sea (see above). Although additional Jinang and Burarra groups also share the same manikay,49 the fact that none of them possess territory directly abutting (or even close to) gapu maramba (cf. the Bindararr estate vis-a-vis gapu dhulway; see above) means that the sea-specific references within the Murrungun song-cycle are invariably and exclusively associated with the Malarra estate.50 As far as I can discern, it is for this reason that my informants do not regard the former groups as co-owners of gapu maramba.

The same informants also maintain that this body of water was once jointly owned by the Yan-nhangu-speaking Mukarr or

274Gurrmirringu—the semi-mythical Dhuwa moiety inhabitants of Gurriba (northwest Crocodile Island) who are said to have been annihilated by warriors from Murrungga and other locations. With their demise, it seems, sole ownership of gapu maramba passed to the Malarra baparru.

This latter perspective is, however, challenged by a senior male member of the Yan-nhangu-speaking Gamalangga baparru, who asserts that his own Dhuwa moiety group holds exclusive ownership rights in respect of the open sea.51 His assertion appears to be largely based on the conviction that Gamalangga members shared (or perhaps inherited) certain religious resources (notably the rrirakay or clapstick madayin) with (or from) the now extinct Mukarr inhabitants of Gurriba (northwest Crocodile Island) and Gunumba [1] (North Crocodile Reef), and that as such, responsibility for the latter’s land and sea territory is now legitimately held and exercised by the Gamalangga baparru. At the same time he also emphasises connections to the general gapu maramba area via the mulunda (booby) wangarr which links Gamalangga territory at Manbengur on Banyan Island (Garuma) with the important Gurryindi reef site at Ngaliya, some distance offshore from Murrungga, and the yerrpany (wild honey) wangarr which links sites on Banyan Island and Murrungga. To the best of my knowledge, though, he does not assert that Gamalangga members are consubstantially identified with the open sea, as Malarra people and the deceased Mukarr beings are (or were) generally held to be. In this last connection, his reasons for overlooking (or at least failing to acknowledge) the Malarra group as joint owners of gapu maramba are not entirely clear to me, although I suspect that they may well pertain to a long-standing territorial dispute (centred mainly on Gurryindi land and sites) between Malarra and Gamalangga members (see also Davis and Prescott 1992:51–2).

Whatever the case may be, the Gamalangga claim—and the apparent bases on which it is made—are categorically rejected by my main

275Malarra and Gamal informants. As I understand their objections, they variously maintain that the open sea is not a Gamalangga wangarr, that the Gamalangga song-cycle (called Djambidj) does not specifically refer to the open sea itself (i.e. in the sense of citing the actual bundurr names of gapu maramba), that assertions of connectedness to particular sites cannot be legitimately extended to include saltwater itself and, finally, that the person making the claim to gapu maramba is ‘coming from [a] long way’ (i.e. from Banyan Island [Garuma], approximately 34km SSE of Murrungga and 57km S of Gurriba), both in physical and metaphysical terms. As Keen (1994:124–25) indicates, differences of this sort are not uncommon in estate-related matters.52

Since limitations of space preclude any sustained analysis of this particular situation, I round off the present discussion with the general observation that in contexts where competing and mutually exclusive claims to the ownership of saltwater arise or, more precisely, are openly asserted, it is the claims of persons who are widely regarded as being consubstantially identified with saltwater that are, irrespective of any other social and political considerations,53 the ones most likely to be

276acknowledged by the majority of the Burarra and Yan-nhangu jural public. This is because it is that same modality of identification which constitutes and expresses the most fundamental basis of relatedness to country for all Burarra and Yan-nhangu people.

Summary

To close the paper I will briefly summarise its key findings. In my own view, these findings collectively provide an essential frame of reference for any future ethnographic work on customary marine tenure in the Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region. They may also be of some assistance in the conduct of similar work elsewhere in northeast Arnhem Land and perhaps (albeit in a far more general way) in other parts of coastal Aboriginal Australia as well.

Burarra and Yan-nhangu people conceptualise saltwater within the region as two distinct, moiety-specific noumenal entities (wangarr). Respectively termed gapu dhulway and gapu maramba, these entities are considered to be physically manifest as separate bodies of inshore water and open sea water. Gapu dhulway is exclusively affiliated to the Yirritja (called Yirrchinga in Burarra) patri-moiety and gapu maramba is exclusively affiliated to the Dhuwa (called Jowunga in Burarra) patri-moiety.

All coastal estates in the region incorporate marine elements such as sites and/or seabed. Only certain estates, however, are said to incorporate saltwater. Where this occurs, the saltwater elements of an estate invariably extend well beyond the lateral horizons of the estate’s onshore, site and seabed territory. For the purposes of estate delineation, therefore, saltwater is distinguishable from both onshore elements and other marine elements.

No Yirritja moiety estates incorporate open sea water (gapu maramba) and no Dhuwa moiety estates incorporate inshore water (gapu dhulway). As such, regional sea tenure patterns differ markedly 277from the alternating pattern of moiety affiliations often associated with neighbouring onshore estate areas.

Saltwater in the region is most clearly identified with and owned by four patrifilial groups (B: yakarrarra; Y: baparru). The inshore water of gapu dhulway is thus identified with the Gamal, Bindararr and Ngurruwula groups (collectively known as Walamangu), while the open sea water of gapu maramba is identified with the Malarra group. In each case consubstantial identification and/or (cf. the Bindararr group’s possible status in relation to gapu dhulway) the ownership of sea-specific religious resources (madayin) are locally cited as the principal criteria for such connectedness.

It is also the case that the onshore estates of the groups most closely identified with either gapu dhulway or gapu maramba directly abut the relevant body of saltwater.

Claims to the ownership of saltwater may also be made on other grounds, including estate-succession and mythological connections to sites and land in or near the relevant body of saltwater. Such claims, however, tend to lack the ontological force of claims made by consubstantially identified persons and groups and may well be contested by the latter. A case in point is the claim made to the ownership of gapu maramba by members of the Gamalangga baparru.

Consubstantial identification with saltwater is primarily mediated by patrifiliation, and is articulated at both the individual level and the level of the yakarrarra/baparru. As the principal basis of customary ownership, such identification confers upon the members of relevant yakarrarra and baparru a particular range of inalienable, local-level possessory rights in the particular body of saltwater with which they are identified. While many of these rights are also extended to other members of Burarra and Yan-nhangu societies, whether on the basis of kinship relations or of cosmologically inscribed connections between patrifilial groups, it is only the owning groups which possess the full range thereof.

The Burarra and Yan-nhangu patrifilial groups identified with either gapu dhulway or gapu maramba also form part of more extensive, 278moiety-specific constellations of ‘title holders’ in respect of saltwater. In both social and geographical terms, these constellations extend well beyond (i.e. to the east of) the immediate Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region. It is, however, only members of the relevant Burarra and Yan-nhangu groups who can speak with authority in relation to the local waters of gapu dhulway and gapu maramba.

Addendum

I have since learned that Burarra and Yan-nhangu also regard gapu dhulway and gapu maramba as gendered bodies of saltwater, with the former construed as female (B: gun-gama; Y: munhkangu) and the latter as male (B: gun-guchula; Y: marlaway).54 Moreover, the two stand in a mutual spouse relationship (B: awurri-berrkuwa; Y: galay’manydji) which effectively demarcates them from other, mythologically related, waters further east.55

The Burrara-speaking An-mujolgawa yakarrarra has been inadvertantly omitted from the lists of coastal estate-owning units. A Jowunga moiety yakarrarra (population 4), Anmujolga’s territory includes at least one onshore coastal site located 1–2 miles east of the Blyth river and bordered on either side by on either side by Ganmal yakarrarra territory.

Notes

This chapter is partly based on a report prepared for the Northern Land Council on regional marine native title rights and interests (Bagshaw

2791995a). I thank Diane Bell, Peter Sutton and James Weiner for their comments on an earlier draft of the present document. I am also especially indebted to Lily Garambara and her late husband RR, to Kevin Jawunygurr and to Michael Marragalbiyana for the provision of much of the information recorded here. The paper itself is dedicated to the memory of RR.

References

Aboriginal Land Commissioner 1981. Closure of seas: Milingimbi, Crocodile Islands and Glyde River area. Darwin: NT Government Printer.

1988. Closure of seas: Castlereagh Bay / Howard Island region of Arnhem Land. Darwin: NT Government Printer.

Bagshaw, G. 1979. Coastal sites: Blyth River Cape Stewart. Report to Northern Land Council. Darwin: Northern Land Council.

1991a. Report to the [Northern Territory] Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority on the registration of marine sacred sites at Wumila and Mirragaltja near Milingimbi Island. Confidential report. Darwin: Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority.

1991b. Report to the [Northern Territory] Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority on the registration of marine sacred sites in the eastern Boucaut Bay site complex. Confidential report. Darwin: Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority.

1991c. Burarra country: the socio-cultural context of sites in the Blyth River estuary. Unpublished ms. Darwin: Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority.

1995a. Preliminary report on sea tenure and native title in the Blyth River Crocodile Islands region. Report to Northern Land Council.

1995b. Comments on S. Davis’ map. In Country: Aboriginal boundaries and land ownership in Australia (ed.) P. Sutton. Canberra: Aboriginal History Monograph 3. Pp. 122–124. 280

Berndt, R.M. 1951. Kunapipi: a study of an Australian religious cult. New York: International Universities Press.

1955. ‘Murngin’ (Wulamba) social organization. American Anthropologist 57:84–106.

Clunies Ross, M. 1990. Some Anbarra songs. In The honey-ant men’s love song and other Aboriginal song poems (eds) R.M.W. Dixon and Martin Duwell. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press. Pp. 70–103.

Cooke, P. n.d.(a). A draft literature review concerning Aboriginal interests in submerged lands in the eastern Arafura Sea. Report. Darwin: Northern Land Council.

n.d.(b). Ethnographic pilot eastern Arafura Sea. Report. Darwin: Northern Land Council.

1995. Literature-based view of Yolngu marine interests. Report. Darwin: Northern Land Council.

Davis, S. 1981. A report on Aboriginal sites of significance in north eastern Arnhem Land [Sections 1 and 2]. Confidential report. Darwin: Aboriginal Sacred Sites Protection Authority [NT].

1984a. Aboriginal tenure and use of the coast and sea in northern Arnhem Land. MA thesis: Melbourne: University of Melbourne.

1984b. Aboriginal tenure of the sea in northern Arnhem Land. In Workshop on traditional knowledge of the marine environment in northern Australia. Series No.8, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

Davis, S.L. and J.V.R. Prescott 1992. Aboriginal frontiers and boundaries in Australia. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

Dreyfus, M. and M. Dhulumburrk 1980. Submission to Aboriginal Land Commissioner regarding control of entry onto seas adjoining Aboriginal land in the Milingimbi, Crocodile Islands and Glyde River area. Unpublished Report. Darwin:Northland Land Council. 281

Ginytjirrang Mala/ADVYZ 1994. An indigenous marine protection strategy for the Arafura Sea. Report to Northern Land Council and Ocean Rescue 2000.

Glasgow, K. and D. Glasgow 1985. Burarra to English bilingual dictionary. Darwin: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Hiatt, L.R. 1965. Kinship and conflict: a study of an Aboriginal community in northern Arnhem Land. Canberra: Australian National University.

1982. Traditional attitudes to land resources. In Aboriginal sites, rights and resource development (ed.) R.M. Berndt. Perth: University of Western Australia. Pp. 13–26.

1986. Rom in Arnhem Land. In Rom: an Aboriginal ritual of diplomacy (ed.) Stephen A. Wild. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. Pp.3–13.

Keen, I. 1977. Contemporary significance of coastal waters in the spiritual and economic life of the Aborigines. Submission to the Australian parliamentary joint select committee on Aboriginal land rights in the Northern Territory. Official Hansard Report, Tuesday 3 May 1977.

1978. One ceremony, one song: an economy of religious knowledge among the Yolngu of north-east Arnhem Land. PhD thesis. Canberra: Australian National University.

1981. Report [to Aboriginal Land Commissioner] on the Milingimbi closure of seas hearing. Typescript.

1983. Report [to Aboriginal Land Commissioner] on the application to close the seas adjoining Aboriginal land in the Castlereagh Bay Howard Island region of Arnhem Land. Typescript.

1984–5. Aboriginal tenure and use of the foreshore and seas: an anthropological evaluation of the Northern Territory’s legislation providing for the closure of seas adjacent to Aboriginal land. Anthropological Forum 5(3):421–439. 282

1991. Yolngu religious property. In Hunters and gatherers: [Volume 2] property, power and ideology (eds.) Tim Ingold, David Riches and James Woodburn. New York/Oxford: Berg. Pp. 272–291.

1994. Knowledge and secrecy in an Aboriginal religion. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

1995. Metaphor and the meta-language: ‘groups’ in northeast Arnhem Land. American Ethnologist 22(3):502–527.

Meehan, B. 1977. Submission to parliamentary joint select committee on Aboriginal land rights in the Northern Territory. Typescript.

1982. Shellbed to shell midden. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

1983. Sites of significance at the mouth of An-gatja Wana (Big River) or the Blyth River in Arnhem Land. Confidential report. Darwin: Aboriginal Sacred Sites Protection Authority [NT].

McIntosh, I. 1994. The whale and the cross: conversations with David Burrumarra MBE. Darwin: Historical Society of the Northern Territory.

Northern Land Council 1992. Submission to the Resource Assessment Commission Coastal Zone Inquiry, June 1992. Darwin: Northern Land Council.

1995. Marine protected areas: a strategy for Manbuynga ga Rulyapa. Unpublished report.

Palmer, K. 1984–5. Ownership and use of the seas: the Yolngu of northeast Arnhem Land. Anthropological Forum: 448–455.

Ritchie, D. 1987. An-gatja Wana site complex: attempts by Aboriginal custodians to protect the area from intruders. Report to Aboriginal Sacred Sites Protection Authority [NT].

Shapiro, W. 1981. Miwuyt marriage: the cultural anthropology of affinity in northeast Arnhem Land. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues. 283

Stanner, W.E.H. 1965. Aboriginal territorial organization: estate, range domain and regime. Oceania 36(1):1–26.

Sutton, P. 1996. The robustness of customary Aboriginal title under Australian pastoral leases. Draft paper, version 13 May 1996.

Verdon, M. and P. Jorion 1981. The hordes of discord: Australian Aboriginal social organisation reconsidered. Man (N.S.) 16(1):90–107.

Warner, W.L. 1937. A black civilization: a study of an Australian tribe. New York: Harper.

Wild, S.A. (ed) 1986. Rom: an Aboriginal ritual of diplomacy. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Williams, N.M. 1986. The Yolngu and their land: a system of land tenure and the fight for its recognition. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Zorc, R.D. 1986. Yolngu-Matha dictionary. Batchelor NT: School of Australian Linguistics284

1 See, for example, Aboriginal Land Commissioner (1981); Bagshaw (1979, 1991a, 1991b, 1991c, 1995a); Cooke (n.d.[a], n.d.[b], 1995); Davis (1981, 1984a, 1984b); Davis and Prescott (1992); Dreyfus and Dhulumburrk (1980); Keen (1977, 1981, 1984–85); Meehan (1977a, 1977b, 1977c, 1982, 1983); and Ritchie (1987). Similar material from neighbouring parts of Arnhem Land can be found in Aboriginal Land Commissioner (1988); Davis (1981, 1982); Ginytjirrang Mala/ADVYZ (1994); Hiatt (1982); Keen (1982, 1983); Northern Land Council (1992, 1995); and Palmer (1984–85).

2 Both assumptions clearly inform Davis’ mapping of local estates (see Davis 1984a:89–90).

3 Being an initial ethnographic statement the paper does not attempt to explore the complex theoretical issues (e.g. the logic of moiety classification, the constitution of patrifilial groups, the relationship between patrifiliation and consubstantial identification with country, competing claims of sea ownership and trans-regional ‘communal title’) to which it sometimes refers. It is hoped that at least some of these issues will be the foci of future studies.

4 Burarra and Yan-nhangu are locally employed sociolinguistic designations. The Burarra are also called Gidjingali by Hiatt (1965)

5 Burarra terms are rendered here according to the standard Glasgow and Glasgow (1985) orthography. Yan-nhangu terms are based on the Zorc (1986) orthography. Certain terms (e.g. wangarr, madayin) are common to both languages.

6 Baparru is a polysemic term which also refers to several other types of social formations and metaphysical categories (cf. Shapiro 1981, Williams 1986, Keen 1994, 1995). Although variations of the same term (e.g. baparrurr and baparru) are also used by Burarra-speakers (cf. Hiatt 1965), the term yakarrarra more precisely designates the patrifilial estate-owning group. Partly as a result of their relatively small size and partly as a result of the fact that all but one of them possess a single onshore estate tract, Burarra yakarrarra appear to be much less labile in terms of their constitution and estate identification than the Yolngu baparru recently described by Keen (1995).

7 As other observers have pointed out, madayin variously connotes ‘greatest value [… and …] beauty’ (Williams 1986:243), ‘sacred law’ (Morphy 1991:170) and ‘sacra, [a] category of things and events associated with wangarr ancestors, [including] sacred objects’ (Keen 1994:308).

8 Persons in the former category in particular are sometimes referred to as ‘guardians’ (B: jaga an-gugana; Y: jagay) of the relevant estates and associated madayin. Keen (1991, 1994) notes that in the Yolngu region (of which the Yan-nhangu domain is generally considered to form a part) waku-watangu or ‘MMM-related group’ also have significant rights and interests in their MMM estates.

9 Owing to the fact that they share major religious resources with a Yannhangu baparru, the members of two predominantly Burarra-speaking yakarrarra also identify themselves as Yan-nhangu speakers (see also main text below). In addition to their proper names, most of the of the patrifilial groups referred to here are identified by broad, and in some cases moiety-specific, designations which expressly denote the coastal setting of their estates. Among these ‘district’ designations are Gurridhay (‘coast’; both moieties), Gulala or Gulalay (‘mangrove pod’; Yirritja moiety only) and Maringa (‘coast’; Dhuwa moiety only). Such terms are common to both the Burarra and Yan-nhangu languages. Additional Burarra estates are located on the coast west of the Blyth River mouth (see Hiatt 1965:18, 1982). However, like the two Dhuwa moiety Jinang estates (Gangal, Manharrngu) and the two Yirritja moiety Wulaki estates (Mildjingi, Baytjimurrungu) in and around the Crocodile Islands, these are not considered here.

10 The Jowunga moiety Maljikarra, Marrawundi and Balwarra yakarrarra are often considered to be joint owners of a single estate in the vicinity of Inanganduwa (False Point). I have, however, also recorded information which indicates that each group may be primarily identified with distinct, albeit adjoining, sites and territories. One of my principal informants alternatively maintains that Maljikarra and Marrawundi are one and the same yakarrarra. The Jowunga moiety Gaburrburr yakarrarra is extinct. Its estate is variously managed by the Liralira (Burarra, Jowunga moiety), Gamalangga (Yan-nhangu, Dhuwa moiety) and Warrawarra (Burarra, Yirrchinga moiety) groups (cf. Davis 1984a:52). Liralira, Gamalangga and Gaburrburr share the same principal madayin, while Warrawarra owns a neighbouring estate defined as ‘spouse country’.

11 I include all permanently exposed islands (B: bamara; Y: dhakal) in the former category.

12 The sole exception to this pattern is the Gamal estate, which includes discontinuous tracts in the vicinities of Boucaut Bay and Cape Stewart.

13 Estate-specific tracts in both the Burarra and Yan-nhangu domains are generally named after prominent sites therein (i.e. each tract is known by a single ‘big’ place name, cf Davis 1984a:57–8; Keen 1994:104).

14 The figures referred to here exclude the 222sq.km of Gamalangga territory on Banyan Island (Garuma) to the south and south-east of the Crocodile Islands (Davis 1984a:107).

15 Relevant estates include those of the Gurryindi, Malarra and Ngurruwulu baparru. Members of the Gamalangga baparru also claim to have such interests in this area (see also main text below).

16 I conducted this survey in August 1995 with a now deceased senior male member of the Malarra baparru.

17 A limited exception is the Ginytjirrang Mala/ADVYZ (1994) document (see also footnote 25 below). Typically, even among those who, like the Aboriginal Land Commissioner in the Castlereagh Bay/Howard Island sea closure case, acknowledge that ‘[t]he land and water of an estate is conceived of as the substance of the ancestral beings (‘wangarr’), which inhabit it’ (1988:3), there is no clear recognition of saltwater itself as such a being or beings. In the instance just cited, saltwater (i.e. ‘water’) appears to be interpreted as a medium that is somehow consubstantial with the other wangarr ‘which inhabit it’. It should also be noted that in all of their extensive writings on customary marine tenure in and around the Crocodile Islands (see footnote 2 above), neither Keen nor Davis makes mention of the fact that saltwater itself is accorded wangarr status.

18 Zorc 1986:122.

19 Gapu dhulway is said to contain or flow over mud (B: gapurra; Y: djudum). It is also explicitly associated with floating mangrove leaf debris (gaylinjil). Gapu maramba, on the other hand, is said to flow over rock reefs (B: gun-gurrema; Y: dhungupal) and is associated with floating seaweed (B: gapalma; Y: jiwul).

20 Constant movement of water (B: bugula gu-gakiya gu-workiya; Y: gapu bayngu walngan), constant sound of water (B: bugula gu-weya gu-workiya; Y: gapu bayngu wanga), constantly changing form of water (B: bugula gu-ngukurdanyjiya gu-workiya; Y: gapu bayngu bilyun). The Yan-nhangu term bayngu ‘habitually’ should not be confused with the identical Yolngu-matha word for ‘none / nothing’.

21 The use of anatomical referents is a basic feature of Burarra and Yan-nhangu modes of classifying form and space. Terms of the this kind are also applied, inter alia, to onshore topographic features and material goods.

22 I am told that there is no equivalent Yan-nhangu expression.

23 See also footnote 32 below.

24 According to Ginytjirrang Mala/ADVYZ, however: Our names for the seas off our homelands are Manbuynga and Rulyapa. Manbuynga ga Rulyapa are the names of the two elemental forces or currents in the Arafura Sea. These are the most important names for the sea and Yolngu law arises from their journey. There are also named waters which arise in the bays and elsewhere along our coast. But those names stop in inshore areas. All water ends up as Manbuynga ga Rulyapa. Only these two names extend out into deep water (1994:3).

25 Although inshore waters immediately to the west of the Blyth are also identified with the Burarra Yirrchinga patri-moiety, they are considered to be mythologically unrelated. Further research is needed to fully establish the eastern limits of gapu dhulway. In view of the posited mythological relationship between gapu maramba and separately owned Yirritja moiety waters located near Howard Island to the SSE of Murrungga (see main text below), it is likely that gapu dhulway does not extend very far beyond the eastern tip of Murrungga.

26 According to Williams (1986:67–8): Balamumu and the contextually linked term Wulamba are names that refer to specific characteristics of waters off the shores of Blue Mud Bay in the Gulf of Carpentaria: rough water and foaming white caps as the strong trade winds … come from myth-related lands to the south and lash these waters. Balamumu is a name in the categorybaparru names that belongs to the Djapu clan, and a number of other groups of the Dhuwa moiety may symbolise their relationship to the Djapu through the Balamumu (or Wulamba) baparru.

27 Similar connections may also exist with waters in the vicinities of Gananggarngur Island (Baytjimurrungu baparru) and the mainland near Elcho Island (Guyamirrilili baparru).

28 Contrary to the trans-regional dichotomy of Yirritja moiety inshore waters and Dhuwa moiety open sea assayed here, McIntosh (1994:129) refers to a line from a ‘camp song’ associated with the Yirritja moiety Warramiri baparru from the Wessel Islands in which it is stated: ‘Ngayum Djangu Golula. I am the open sea’. As Palmer (1984–85) further refers to both Dhuwa and Yirritja land and sea estates in the Wessel Islands area, it may well be the case that patterns of sea tenure in the Wessel Islands differ substantially from those in the Burarra and Yan-nhangu region.

29 Tidal action is also the subject of more highly elaborated mythologies. Owing to their culturally restricted nature, however, these mythologies will not be discussed here.

30 E.g. mortuary rites and circumcision rituals.

31 Other regional manikay also contain references to saltwater (see also footnote 42 below). In performances of the Wulumungu and Murrungun manikay, the sounds and relative distances of gapu dhulway and gapu maramba are evoked through particular styles of singing: the inshore water verses of the Wulumungu manikay are clearly articulated and sung ‘with the mouth’ (B: ngana aburr-jirra; Y: dha dhana bayngu milama), whereas Murrungun verses pertaining to the more distant waters of gapu maramba are deliberately muffled and sung ‘with the throat’ [B: gu-lorr aburr-jirra; Y: gurak dhana bayngu milama).

32 By ‘customary ownership’ I mean that certain yakarrarra and baparru traditionally hold a specific and inalienable set of possessory rights in respect of either gapu dhulway or gapu maramba (see also main text below).

33 Adoption into a relevant yakarrarra or baparru may also confer de facto consubstantial status.

34 Similar statements are also made in relation to the totality of a person’s estate (i.e. including the land component). In the Burarra context, the concept of actively engendering phenomenal existence (i.e. ‘begetting’) is further elaborated to include a notion of reciprocal begetting (-bokamarrachichiyana) between members of the same yakarrarra. However expressed, the concept of begetting invariably connotes an equivalence of identity between the begetter(s) and the begotten. Among the Burarra and Yan-nhangu groups most widely identified with saltwater, the only one which is sometimes not regarded as being consubstantial with saltwater is Bindararr (for further details see main text and footnote 44 below).

35 Saltwater bundurr may also be used as personal names by second-descending generation matrifiliates (B: aburr-mari; Y: wayirri watangu) and their offspring.

36 Matrifiliates may control movement within or around a body of water. Ideally, however, only members of the owning yakarrarra and/or baparru may give permission to enter that body of water (i.e. to persons other than matrifiliates in the first or second descending generations).

37 The former, non-exclusive, rights in saltwater are perhaps most appropriately termed rights of possession or association. Davis (1984a:78–84), variously characterises such rights as complementary or subsidiary rights and goes on to point out that a number of authors have distinguished between ‘primary and secondary rights’ (Peterson et al 1977) or ‘primary [/] presumptive and subsidiary rights (Williams 1983:103).

38 Aside from the members of the owning yakarrarra and baparru, the only persons at the local-level who formally hold rights 1c, 1d and 2b are matrifiliates in the first and second descending generations. It is possible (but not yet firmly established by my research) that members of other patrifilial groups identified with saltwater in areas to the east of the Blyth River—Crocodile Islands region may also be entitled to exercise right 1d. The argument of Verdon and Jorion (1981) concerning the relationship between ‘ontological distance’ from an ancestral being and degrees—or, as they put it, the ‘intensity’ of land ownership—is highly relevant here. According to these authors: ‘[the] ontological distance which governs access to the various levels of religious knowledge is also used as a scale to measure a ‘gradient of rights of ownership’ which stem, to a certain degree, from occupancy and use of the land surrounding the totems […] all who exploit the land ‘own’ it, in the sense that they enjoy a privileged access to it, but some own it more than others. Those who own it the most with respect to the criterion of occupancy are, at the same time, those ontologically closest to the ancestor whose sites are located on that land, and who can therefore claim to have occupied the the land since its creation.’ (1981:100). Unlike these authors, however, I maintain that, in this area at least, there are indeed specific, identifiable estates and corporately held rights therein. In this last respect, I also differ from Keen (1995).

39 Available evidence suggests that one of the latter tracts which is presently claimed by the Gamalangga baparru is, in fact, Gurryindi territory.

40 Keen (1994:105) contests the notion of alternating patrimoiety estates along the coast. In my own view, such patterning constitutes a general, though by no means universal, feature of local territorial organisation.

41 The more general characterisation of gapu dhulway as shared Yirritja moiety water may be related to the fact that most, if not all, Yirritja moiety patrifilial groups also have saltwater verses in their respective manikay. As I understand it, however, the saltwater bundurr (ritual names) within these latter manikay directly refer to, and are exclusively identified with, the estates of patrifilial groups which own the Wulumungu manikay. Accordingly, only these latter are actually considered to own the relevant bundurr.

42 As I have pointed out elsewhere (Bagshaw 1995b:123), Walamangu is often mistakenly given as the name of a single baparru (Warner 1937:51; Davis 1984a:110; Davis and Prescott 1992:57; Keen 1978:24). The Gamal and Ngurruwula groups and estates are held to exist in a permanent, totemically defined sibling relationship. The Gamal and Bindararr groups and estates are, however, respectively defined as MM/MMB-fDC/ZDC. Surprisingly, therefore, the Ngurruwula and Bindararr groups and estates are also defined as siblings.

43 The Bindararr yakararra is directly identified with the dingo (B: gulukula; Y: wartu) and northeast wind (lunggurrma) wangarr. Both are held to be intimately associated with the incoming tidal movement of inshore water. Only the latter wangarr, however, is common to all Walamangu groups.

44 One of my principal Gamal informants contends that the saltwater verses of the Wulumungu manikay exclusively identify gapu dhulway with Gamal and Ngurruwula and, that as such, the Bindararr group is only linked to this body of water by virtue of its co-ownership of the manikay as whole, rather than by way of direct, consubstantial identification with the relevant saltwater wangarr. The Bindararr connection to gapu dhulway is thus said to be purely ‘song-based’ (B: manikay wupa; Y: manikay bam). Although I cannot say how widely this opinion is shared by other Burarra and Yan-nhangu people, it does appear that, for all practical purposes at least, the group concerned is generally regarded as a legitimate co-owner of inshore water (see also footnote 49 below). Since the death of the most senior Bindararr man at Milingimbi in August 1995, I have not had the opportunity to obtain any Bindararr perspective on the matter.

45 The principal focus of the complete verse is upon the waters in the Bunbuwa area.

46 Variously referred to as a ‘phratry’ (Warner 1937) or ‘clan-aggregate’ (Keen 1978), Mandjikay is a Yirritja moiety ‘totemic union’ (Shapiro 1981:23) based on common identification with rock and mangrove wood wangarr. According to Keen (ibid:24–5), its constituent groups include: Gulalay/Gamal, Walamangu/Ngurruwulu, Wangurri, Lamilami, Golumala, Wobulkarra, and Ngurruwula also form part of a much broader totemic aggregation called Mandjikay. Guyamrirrilili/Galngdhuma/Liyalanmirri. McIntosh (1994:98) also refers to ‘a Mandjikay clan from Howard Island [called] Golpa’. This latter group may be the same as Wobulkarra. Keen (1995:515) adds that ‘perspectives on which Yirritja moiety groups were Manydjikay [sic] people, linked by the journeys of Rock and Mangrove Log ancestors along the coast, differ’.

47 My transcription of this excerpt omits certain stylised features such as extra and/or extended final syllables in some words. The excerpt itself constitutes less than half of a single saltwater verse.

48 The Bunbuwa / Dhawukula and Munungurrumba / Marrambirlpirl areas are both on the east coast of Boucaut Bay. The Walamarrana / Girrkirra area is situated on the east coast of Rapuma (Yabooma Island). Several other named sites and areas are either directly or indirectly linked to gapu dhulway. Of those mentioned here, only the Marrambirlpirl / Munungurrumba appears to have no explicit connection to saltwater in the Wulumungu manikay (cf. footnote 45 above) It should be noted, however, that the bundurr name Marrambirlpirl—which also features in the Wulumungu manikay—primarily denotes an area of tidally exposed flats and is thus indirectly connected to inshore water.

49 Other patrifilial groups said to share this manikay include Bargatgat (Jinang), Gangal (Jinang), Maljikarra (Burarra), Yemara (Burarra) and Guwowura (Burarra).

50 The Murrungun or Malarra manikay appears to be the same song-cycle as that called Goyulan by Hiatt and Wild (in Wild ed. 1986) and Clunies Ross (in Dixon and Duwell eds. 1990). Several of the ‘Goyulan’ themes mentioned by these authors directly refer to Malarra-owned territory in the Crocodile Islands.

51 As he put it to me in a mixture of Burarra and English: ‘Yi-gurrepa Bapua blue sea, still gun-ngaypa … Gamalangga gun-nika, ngika company’: ‘The open sea close to [i.e up to] New Guinea is still mine … it belongs to Gamalangga, it’s not jointly owned’.

52 According to Keen (1994:124–25), people in this general region: ‘argued about at least four aspects of relations to land and waters: the extent of a group’s country, the group identity of a particular place, the ranking of groups who possessed the songs and ceremonies about a place and succession to a deceased or dying group’s country’.

53 Cf. Keen (1994:129): ‘Certain matters were widely agreed. The general location of named places and their spiritual significance were widely known, although there were disagreements and variation in the depth of knowledge about details. Under many circumstances such matters could remain ambiguous. Where they had to be resolved, what counted was being able to act on one’s version of ownership; to enact the prerogatives due to a land-holder or dja:gamirri (one who ‘looks after’), which include control of access to the … land and use of the country, such as to establish an outstation, and performance of the related ceremonies. The size of the group was important for such abilities, but so was one’s place of residence. Those who lived at or near a disputed country, who had the more detailed knowledge of it, and could muster the most support, were at an advantage. Sheer physical force, related to group size and demographic structure may also have been a factor’.

54 54 I am grateful to Fiona Macgowan for suggesting this line of inquiry to me.

55 I have not yet ascertained whether the mixing of inshore and open sea water is metaphorically associated with sexual reproduction in the way that the intermingling of fresh and saltwater reportedly is among the ‘Yolngu’ (Keen 1994:211).