Introduction

Since 1 December 2012 all tobacco products sold in Australia – cigarettes, hand-rolling tobacco, cigars and pipe tobacco – have been required to be sold in standard ‘plain’ packs. The only features of the pack that now differentiate one brand from another are the mandatory brand and ‘variant’ names (for example Dunhill – the brand name – and Premier Red – a variant of the Dunhill brand). The tobacco manufacturing and importing companies are required to comply with graphic health warning legislation, put their name and address on the side of the pack, and have a unique bar code, which means nothing to any smoker. Other than these differences, all packs look the same, aside from the variations induced by having one of 14 graphic health warnings.

But there is nothing plain about Australia’s plain packs. They are anything but plain white or drab boxes. The plain packaging legislation was accompanied by new regulations about cigarette pack warnings requiring that the graphic (picture) warnings that had appeared on all Australian packs since 2006 be increased to 75% of the front of the pack. The size of the combined text and graphic warning must take up 90% of the back of the pack.

World first

Australia’s plain packaging legislation was the first time anywhere in the world that a government had mandated what the entire appearance of packaging for any product must look like. There are many categories of consumer goods where governments require mandatory inclusions on packaging or apply standards to the products themselves. Ingredient labelling on foods, warning labels on dangerous household or garden products like cleaning agents, pesticides or flammable goods, and pharmaceutical product information about dosage and contra-indications, are all examples where such requirements are common. Many governments also require that certain consumer goods must meet safety standards and that advertising claims for them should not be misleading.

But nowhere has there been any example of the entire packaging of a product been prescribed. The Australian legislation was therefore globally historic, unique and made the statement that tobacco products were, in every respect, exceptional items of commerce.

Australia joined the front line of global tobacco control 30 years ago when it became one of the first nations to start banning tobacco advertising (direct advertising of cigarettes was banned on radio and television from September 1976). Since that time, successive Australian governments at state and federal levels have incrementally progressed their commitment toward a comprehensive approach to tobacco control. Components of Australia’s approaches to tobacco control include the following:1

- Taxing tobacco to increase its cost to smokers or potential smokers, thereby putting a brake on consumption and stimulating cessation. After Norway, Australia has the most expensive cigarettes in the world. (3)

- Mass reach anti-smoking media campaigns, well-funded in Australia by most global standards. (4)

- Smokefree workplace and public spaces legislation which prevents smoking inside all public places including all forms of public transport, restaurants, cafes, bars and pubs, theatres, cinemas, public halls and, increasingly, sports stadiums and some outdoor dining areas.

- Large, graphic pack warnings.

- Bans on the retail display and point-of-sale promotion of tobacco products.

- A prohibition on the use of the deceptive cigarette descriptors ‘light’ and ‘mild’ (5)

- Limits on duty-free imports (only 50 cigarettes) per adult.

- Government subsidy of evidence-based smoking cessation medications and Quitline funding.

- Specific focus programs such as the Tackling Indigenous smoking initiative.

Plain packaging is the latest change in a long series of encroachments onto the pack that commenced with the first tiny warning at the base of packs that appeared from 1973. The tobacco industry strongly resisted all of these in Australia, as elsewhere around the world. A British American Tobacco (BAT) official wrote to its German branch office in 1978: ‘Obviously the group policy should be to avoid health warnings on all tobacco products for just as long as we can.’ Over the next decades Big Tobacco sought to defeat, dilute and delay even the most modest changes to pack warnings (see a history of this in Australia here (6)).

The industry threw everything it could at the effort to stop plain packaging: millions of dollars in hysterical TV and other advertising, a forlorn High Court challenge that was rejected by all but one of the seven judges, intense public relations activity, a conga-line of melodramatic political threats and bluster from industry allies, including often obscure US trade and commerce groups. The slippery slope metaphor was given its biggest ever workout: life as we know it would surely soon collapse entirely into dreary North Korean conformity when anything posing even the smallest risk to health was treated in the same way as tobacco.

Between us, we have worked in tobacco control for a combined total of 50 years, as researchers and advocates for policy change in several different countries. Neither of us ever experienced anything remotely as intense and as sustained as the tobacco industry’s push back against the impending introduction of plain packaging. As we discuss in the final chapter, plain packaging has already begun to spread to other nations. Because the stakes are so large and the potential impacts so devastating to the tobacco industry, we would expect similar resistance there to such developments. This is already happening in Great Britain, Ireland and New Zealand, using a template that was tried and failed miserably in Australia.

There is probably no more telling illustration of how much the tobacco industry fears plain packaging than a comment made to a parliamentary committee in August 2011 by the chief executive of British American Tobacco Australia (BATA), David Crow. Crow almost begged the politicians to keep on raising tobacco tax instead of introducing plain packs. He said:

What I do believe is that . . . if the objective is to reduce consumption then you would move towards areas which have been evidence-based not only in this country but in others around the world – things like education, which have been proven to work and have been the focus of many studies across the world. They have been proven to work very, very well. We have great examples in this country not only on tobacco but on things like skin cancer and drink driving laws, where they have changed consumer behaviour. We have seen that being effective not only here but elsewhere. There should be more, more and more on that. We need uniformity on pricing; we need to get pricing right and excise regimes right. We understand that the price going up when the excise goes up reduces consumption. We saw that last year very effectively with the increase in excise. There was a 25 per cent increase in the excise and we saw the volumes go down by about 10.2 per cent; there was about a 10.2 per cent reduction in the industry last year in Australia. So there are ways of achieving the objectives that do not infringe on the property rights, do not breach the laws and the international commitments and do not mean that the Australian government would have to compensate people. (7) [our emphases]

Paul Grogan, head of advocacy for Cancer Council Australia, was incredulous at Crow’s candour here, in underscoring the sheer desperation of the industry to offer up even another significant tax rise in lieu of plain packs:

I was at a hearing where he was fronting the industry presentation and he effectively said ‘we need to increase tobacco excise’. And I was thinking, really great! Because we know that really works. That really struck a chord with a few members of the committee who were informed enough to know that [tax] really does work. So they were saying ‘how desperate is this guy, if he’s putting up as an alternative something that has been proven to work over 30 years of evidence? Maybe this thing [plain packaging] will work even better.’ It was a very strange kind of desperation.

Why plain packs?

Why is tobacco so ‘like no other product’ that it warrants this treatment? Globally, tobacco claims more than five million deaths a year. Many smokers suffer for years from wretched diseases like emphysema which eventually makes taking a few steps a major effort. Thousands of previously private internal tobacco industry documents read like recipe books from crack cocaine labs, detailing how the cigarette can be better engineered as a nicotine delivery device to ‘make it harder for existing smokers to leave the product.’ (8)

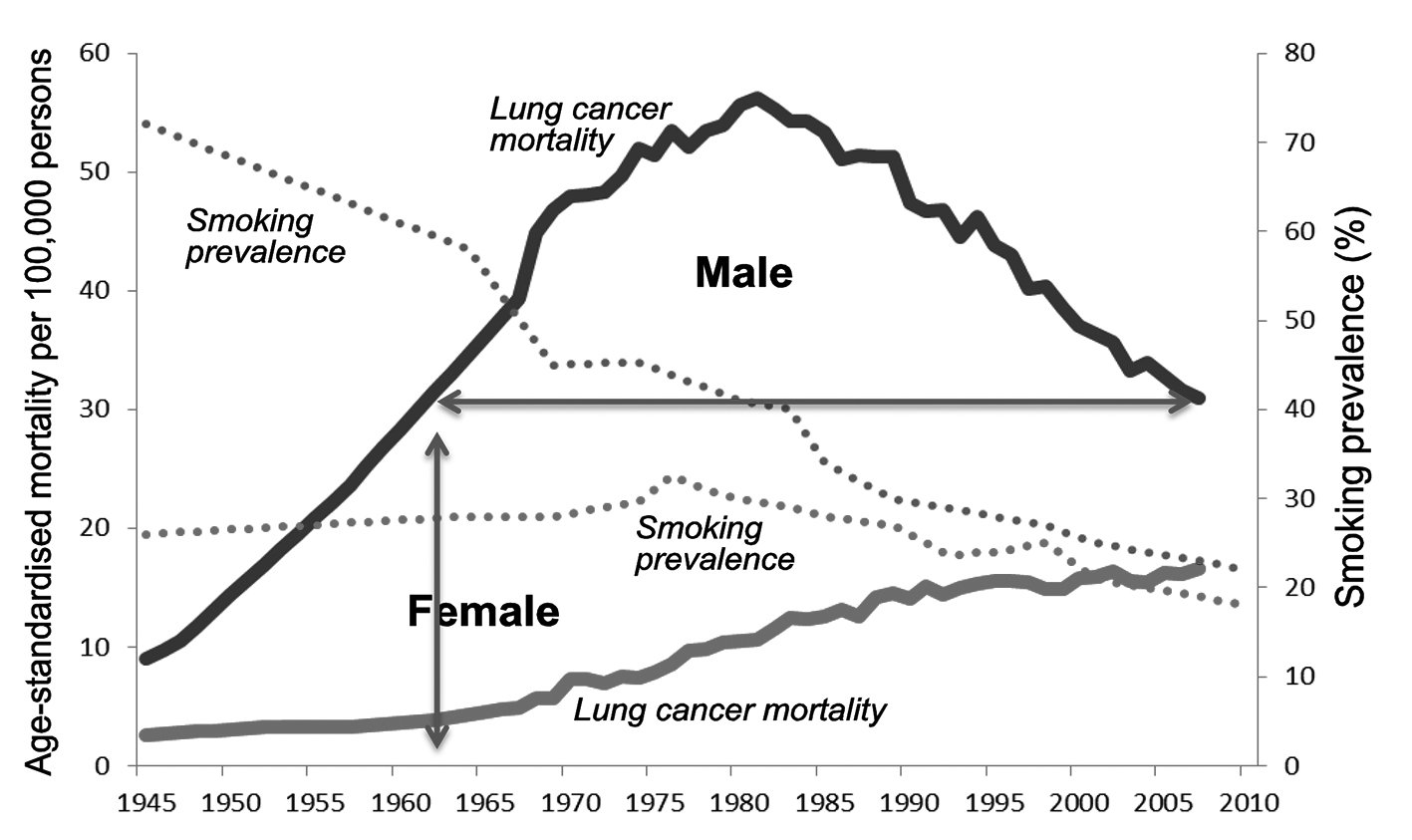

Lung cancer is a disease that was rarely seen before the mid-1930s. (9) Thanks to cheap cigarettes that flowed from the mechanisation of cigarette manufacture, today lung cancer is the world’s leading cause of cancer death, way ahead of breast, prostate and all other cancers which often attract massive community and political support. Lung cancer in males has been falling every year in Australia since 1982, and female lung cancer rates will probably never reach even half the heights experienced by men (Figure 1), thanks to successive governments taking incremental action to curtail the industry since 1973 when health warnings first appeared. By 2004, the male lung cancer rate had fallen to that last seen in 1963. In 50 years from now, lung cancer may once again be ‘history’.

Figure 1 Male lung cancer rates per 100,000 as low as they were in 1963. Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Mortality Database

The Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin famously said that ‘a single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic’. And in tobacco control, there are statistics to die for. Tobacco caused about 100 million deaths last century. But a projected one billion people will die from tobacco-caused disease this century if present trends continue. (10)

The average smoker takes 12.7 puffs per cigarette. (11) A person who starts smoking at age 15, and smokes 20 cigarettes a day for 40 years, will baste the delicate pink linings of their mouth, throat and lungs with a cocktail of 69 carcinogens (12) some 3,710,940 times by the time they reach just 55 years of age.

Half of long-term smokers die early from a tobacco-caused disease, taking an average of 10 years off the normal life expectancy. (13) Consider the case of former Beatle George Harrison, who died of lung cancer at just 58. At the time of his death, British life expectancy for men was 75 years. So he lost 17 years that we can assume he might otherwise have lived. If we assume Harrison started smoking late – at 18 years – he smoked for 40 years. A cigarette takes about six minutes to smoke. So for every cigarette that Harrison smoked, he lost more than five times the time it took to smoke them all, off his normal life expectancy (14).

On and on it goes. But even stratospheric statistics on tobacco deaths have become banal for many. (10) People rationalise that life’s a jungle of risks, and that feeling fine or seeing longevity in a relative who smokes means that they are bulletproof. People cling to self-exempting beliefs (15, 16) such as that air pollution causes most lung cancer, or that putting on some weight if you quit is more dangerous than smoking.

What is so often missing from these reflections about smoking is any real appreciation of the suffering and greatly diminished quality of life in the years that people can spend living with smoking caused disease.

On many occasions across our careers we have received unsolicited letters, calls and email from people living with tobacco-caused disease. Two in particular stand out.

An articulate 52-year-old woman called me a few years ago. Give the ‘smoking kills’ line a rest, she urged:

I’ve smoked for 30 years. I have emphysema. I am virtually housebound. I get exhausted walking more than a few metres. I have urinary incontinence, and because I can’t move quickly to the toilet, I wet myself and smell. I can’t bear the embarrassment, so I stay isolated at home. Smoking has ruined my life. You should start telling people about the living hell smoking causes while you’re still alive, not just that it kills you.

Then early this year, amid publicity on the 50th anniversary of the first historic United States Surgeon General’s report on smoking, an amazingly brave woman, Karen, wrote to me about her experiences with cancer of the mouth. Smoking tobacco causes around 70% of oral cancer in men, and around 55% in women. (17) In 2009, 3031 Australian were diagnosed with various head and neck cancers, and in 2010, 1045 died. (18)

Here are Karen’s words, used with her permission.

Karen’s story

This cancer is brutal! Treatments are cruel! Daily for six to eight weeks during radiotherapy treatments our head and face is covered with a tight mask and bolted to a slab while radiotherapy is blasted at our mouth, teeth, jaw, face and neck. Damage during and after this treatment is horrendous. Many of us will never speak clearly, swallow or function normally again.

Patients endure tracheotomies inserted in their wind pipe because we cannot breathe naturally through our mouth and nose due to swelling and other side effects.

Many people are left with PEG [percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy] feeding tubes shoved in their stomach for the rest of their lives because they will never swallow normal food via their mouth again. I had a PEG tube for three and a half years. A tube hanging from our stomach is sickening and depressing. Think about never eating another meal or swallowing again! You can’t imagine the never ending physical and emotional hell this particular disease causes.

I was diagnosed in 2007 at 46 years of age. Yes, I smoked for several years. I have endured 12 surgeries since 2007 trying to improve my quality of life.

Almost all my entire tongue, lower jaw, gums and beautiful teeth have been removed and reconstructed because of treatments to remove cancer. Bone was taken from my hip to reconstruct my jaw. Normal function is gone. Permanently. My perfect face is now disfigured.

I have not sat down to a normal meal with friends or family in almost seven years. Those pleasures of socialising, eating at restaurants and dinner parties that everyone regularly attends are history for us. I struggle to control saliva because of oral cavity nerve damage and facial trauma. Sometimes I dribble when I try to speak. I will never kiss again.

My life has been destroyed by this cancer, as has many other wonderful people around Australia. We lose our careers. Relationships fall apart.

We can’t make appointments over the telephone or ask for something over a counter. No one can understand us! We write down questions during appointments because we can’t speak and doctors don’t understand what we’re saying. That doesn’t work! This is frustrating, humiliating and extremely upsetting.

The aftermath from this disease is debilitating and permanent. Dental issues are painful and relentless, yet the previous federal government abolished the Enhanced Care Dental Scheme. This is shameful!

We can’t just pick up from where we left off. We can’t ‘do coffee’ with friends and chat about our issues like most other cancer patients because we can’t speak or drink as normal. We can’t cover our mouth with a piece of clothing and get on with it. Our face is our identity!

Many smokers say things like ‘oh well, I’m going to die anyway’ or ‘I could get hit by a bus tomorrow’. Well, from my experience I can honestly say dying immediately would be much easier than the long slow suffering this disease puts patients through. In 2007 while in hospital I had a cardiac arrest because the tracheotomy blocked. Once resuscitated, little did I know I had years and years of pain, ongoing treatments and loss of normal function ahead of me! It’s devastating!

My lower face and mouth has been cut and shut many times. My neck/throat has been dissected twice ear to ear. It’s been a long difficult road! I’ve undergone six surgeries in the past three years trying to improve mouth function and facial appearance. More than likely there’s a few more down the track. I have a wonderful plastic surgeon who genuinely cares!

Karen’s hopes are for more resources to be given to care and support for people in her situation. We hope her story stimulates far greater attention to the impact of cancer on people’s lives.

But with so much potential for head and neck cancers to be prevented, we hope too that her unforgettable words will be passed along to anyone still smoking. It is stories like Karen’s which explain why tobacco control is so important.

Plain packaging is the latest strategy in a suite of policies and awareness campaigns that have been driving smoking down in nations like Australia over the past three to four decades. It is difficult to overstate the global importance of Australia’s leadership: the new tobacco packaging law makes an exceptional statement about tobacco, lifting it into a league above all other health risks.

There is one parallel: prescribed drugs, which are designed to save lives and enhance health, but are heavily restricted because of misuse concerns. Unlike cigarettes, antibiotics, oral contraceptives and cholesterol-controlling drugs are not sold in pretty, highly market-researched boxes, but in plain packs with the name and dosage instructions.

The tobacco industry has been stripped of its ability to call its carcinogenic products ‘mild’ or ‘light’; banished from all above-the-line advertising and all sponsorship; told by all major political parties in Australia, except the Nationals and Liberal Democrats, that its political donations are unwanted; uniquely excluded from giving research money to universities; rejected as an investment option by an increasing number of superannuation funds; (19) and ensconced in the public’s mind as the index case example of corporate mendacity.

The new Australian pack law sets a catastrophic precedent for the global tobacco industry because it rips the very heart out of its ability to dress the pack to make a killing. Tobacco packaging is now devoid of any graphic feature – including colours and special scripts on the cigarette itself – that conveys any associations other than harm. Just as no Australian aged 22 or under has today ever seen a football match sponsored by tobacco or a cigarette advertisement in any Australian publication or on television, the next generation of kids will grow up having no sense of what the totally image-driven difference is between Brand X or Brand Y, and how they might select a brand to distract from some aspect of a fragile personality. The new law has effectively put an end to this lethal corporate pied piper’s promotional tune that has led many millions to early deaths. The emperor of cancer now has no clothes in Australia.

In public health and medicine, we venerate milestones like public sanitation, the discovery of anaesthesia, the introduction of vaccination, and the development of antibiotics and contraception. With chronic diseases like cancer, heart and respiratory disease dominating global disease profiles, governments with the courage to tackle corporations whose goals are antithetical to public health deserve a similar place in history. This law, combined with the significant tax rises, is as big as it gets.

We have written this book principally for those in other countries wanting to make the best case for plain packaging and to defend it from the inevitable attacks that will follow. We also wanted to produce a history of how such a major step in the history of tobacco control occurred, how it was resisted and how it prevailed. So often, such histories in public health exist as oral histories only, so we wanted to capture as much of it as we could.

1 The best single reference for very detailed information on all aspects of tobacco control in Australia is www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.