5

Indigenism and Australian social work

Indigenism and Australian social work

Indigenism is a concept that has emerged over the last 20 years as a result of the engagement of Indigenous academics with research. It is a way of claiming a space within research for Aboriginal knowledge systems and ways of knowing, being and doing. However, in Australia, Indigenism and Indigenist theory and practice have not been confined to research alone, it has been embedded within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work for a number of decades. This chapter will introduce Indigenism and Indigenist theory and practice in social work, as it was developed in the Australian setting in the 1970s, identify how it has evolved and illustrate how it has impacted on both Australian social work and national policies and practices. The chapter will then move on to explore how Indigenism and Indigenist theory can inform social work theory and practice into the future.

Researchers position themselves in their research projects to reveal aspects of their own tacit world, to challenge their own assumptions, to locate themselves through the eye of the ‘other’, and to observe themselves observing. This lens shifts the observer’s gaze inward toward the self as a site for interpreting cultural experience. The approach is person-centred, unapologetically subjective, and gives voice to those who have often been silenced. (Settee 2007, 117)

The citation above by Settee helps to set the framework for what will follow in this chapter. While Settee is speaking about research, her words also have meaning within the education and practice setting. Indigenism is an unapologetically subjective perspective and practice by indigenous researchers and academics, that opens the indigenous worldview and knowledge systems to non-indigenous practitioners and researchers. This chapter is a small step in introducing how indigenism has been developed and is being progressed in Australian social work today and how it might progress in the future.

The theories and concepts known as indigenist ideology, indigenism and indigenist theory have been developed by indigenous academics and researchers around the world in the margins of the disciplines of social work, education, science, law and many others for a number of years. These theories and concepts acted as a means of incorporating Aboriginal ways of knowing, being, and doing (Arbon 2008; Churchill 1996; DiNova 2005; Martin 2008; Rigney 1997, 2001; Ramsden 2002; Sinclair et al. 2009; Smith 1999, 2012; West 2000) within these disciplines to claim a space, and place for practice and research methodologies that privileged indigenous knowledges.

This chapter introduces, defines and examines what is meant by an indigenist ideology, indigenism, and indigenist theory and then explores how they have already been included into social work education, theory, practice and research in Australia and how these practices might be extended and strengthened into the future. To set the scene, a number of stepping-stones are positioned to allow us to move to the point where the concepts identified above can be introduced and discussed.

The stepping-stones begin with a brief re-visit to the historical beginnings of social work in Britain and America and the ideology that supported it. A second stepping- stone is the identification of two American women who had a lasting impact on social work throughout the world. The third stepping-stone is a brief introduction to how social work began in Australia. This section will include an identification of the different imperatives that informed the beginnings of indigenous social work practice as it contrasted to the practice of non-indigenous social workers.

The chapter then seeks to answer a number of questions. Firstly, why did indigenous academics and researchers believe it was necessary to develop indigenist theory and praxis? Secondly, what has been achieved through this movement? Thirdly, how might this information be incorporated into the schools of social work, guide the development of theories of the south, and inform social work practice and research into the future, while still maintaining its unique indigenist ontology, epistemology, axiology, methods and methodology?

Furthermore, in introducing indigenism and indigenist theory into social work education, a major consideration must be the need to identify ways to prevent the mining and colonisation of indigenous ontologies and epistemologies. This form of practice has been and continues to be condemned, both nationally and internationally (Bin-Sallik 2003; Bishop 2005; Fejo-King 2013; Foley 2002, 2003; King 2011; Martin 2008; Smith 1999, 2012; Rigney 1999). These concerns continue today as raised at the recent 2nd International Indigenous Social Work Conference (July 2013) in Winnipeg, Canada.

Placing some stepping stones

Before moving forward it would be helpful to define what is meant by the terms ontology, epistemology, theory, and working in the margins as they relate to this chapter. An ontology can be described as ‘the theory of the nature of existence, or the nature of reality’ (Wilson 2008, 33). The central question embedded within ontology is ‘What is real?’ This is an interesting question, as reality can be different for each person or groups of people, as we all experience and interpret the world differently. Some different ontologies that have been identified in the literature include the Western, Eastern, and indigenous; however, there are many others.

An epistemology is ‘the study of the nature of thinking or knowing. It involves the theory of how we come to have knowledge’ (Wilson 2008, 33). Often an epistemology is developed without conscious thought; it can be influenced by our standpoint (gender, economic position, ethnicity, culture, lived experience, religious background and/or political perspective) and is intrinsically connected to our ontology. It is often unmarked and un-named, it is just there in the background, used every day as a litmus test against which we measure everything we come into contact with as it causes us to ask, ‘How do I know what is real’ (Wilson 2008, 33).

A theory is a short way of naming a group or set of knowledge systems about a specific topic. Anzaldúa made the following insightful comments about theory:

What is considered theory in the dominant academic community is not necessarily what counts as theory for women of colour. Theory produces effects that change people and the way they perceive the world. Thus we need theories that will enable us to interpret what happens in the world, that will explain how and why we relate to certain people in specific ways, that will reflect what goes on between inner, outer and peripheral ‘I’s within a person and between the personal I’s and the collective ‘we’ of our ethnic communities. (Anzaldúa cited in Pattanayak 2013, 87)

Working in the margins can be understood to be work happening on the outside of the main text or dominant discourse and/or social work context. It is similar to when you read a book and make notes in the margins. These comments can be cross-references, comments of agreement or disagreement, or they can be different ways of achieving the same goal using particular ontologies and epistemologies that may not have been considered by the author. They may also be comments of support for what has been written, or expand upon them.

The beginnings of social work

In their book Unfaithful angels: how social work has abandoned its mission, Specht and Courtney (1994) examined the roots of social work and explained that for the Western world, the forerunners of social work were patronage, piety, the Poor Laws, and philanthropy. Each of these concepts formed the basis of a different strategy to address poverty, initially in Britain and later in America. These concepts became so embedded within social work education, theory and practice that elements of each can still be found today in social work around the world.

In the 1980s, two very influential American women, with diametrically opposite ideologies, also had a lasting impact on social work. These women were Jane Addams and Mary Richmond. Jane Addams is often viewed as ‘the mother of structural social work’. She focused on changing society through the use of existing structures and strengths of the community. To achieve this goal she examined the systems that resulted in poverty and utilised social change mechanisms, such as women’s suffrage and child labour laws, to bring about positive change (Margolin 1997).

Mary Richmond on the other hand is often viewed as ‘the mother of casework’, which included surveillance and the keeping of detailed case-notes. This is also viewed as the beginning of individual social work (Margolin 1997). Margolin highlights the influence of these women when he states, ‘social workers may claim Jane Addams as their source of inspiration, but they do Mary Richmond’ (4).

Apart from the issues of structural versus individual social work, another tension within social work has to do with care versus control. Specht and Courtney (1994) also highlighted that there is a dilemma for social workers, who are often called upon to enact state and government policies of social control, with regard to the protection of children and particular groups of adults.

This issue can sometimes be viewed as a dilemma because this role can conflict with the social justice aspirations of social work and can create an increased risk of burnout for social workers (Margolin 1997). The other risk for social workers is that the people they are working with can come to view them as ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ type characters (Fejo-King 2013). This means that social workers might say to people that they are trying to help them, whilst at the same time enforcing policies that the people see as biased, cruel or evil (Blackstock 2009). This affects the way clients view social workers and, therefore, the ability of the social worker to build relationships of trust with the client or client group (Calma & Priday 2011).

Social work was imported to Australia as a mature profession from Britain and America and first taught at the University of Sydney in 1940. Qualifying graduates were employed either as social service workers in a hospital setting, or as child welfare officers (Camilleri 2005; University of Sydney 2012). This identifies the roots of Australian social work as being firmly embedded in the West and within the Richmond framework.

The beginnings of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work

Due to past government policies and restrictions, very few Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were able to access tertiary education until the 1970’s, when Australian Government policies changed and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had access to tertiary education for the first time. The South Australian Institute of Technology (SAIT) became the first educational institution to take Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students in large numbers, from around the country. These students moved to Adelaide and began their learning journey. Initially, two courses were offered – Community Development and/or Social Work – with exit points being at the certificate or associate diploma level. A social work degree was not offered.

The lack of degree-level studies did not act as a barrier to the students gaining employment. However, it meant that none of the social work graduates of SAIT were eligible for membership with the Australian Association of Social Work (AASW). It also meant that these students were not the decision makers and team leaders in the areas they were working in. Leadership of these positions were held by non-indigenous social workers, psychologists and other professionals with a degree as a base line entry.

These practices bought about critical reflection on the part of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers, resulting in the development and progressing of Aboriginal Terms of Reference (ATR) (Kickett 1992). I use this terminology because in the 1970’s the terms indigenist, indigenism, and indigenist theory and practice, had not yet been named. Further information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work in Australia and the way in which it was embedded within indigenist ideology, indigenism, indigenist theory and practice will be discussed later in the chapter. The next section will focus on defining these concepts.

An indigenist ideology, indigenism, and indigenist theory and practice

Indigenism has been the way in which indigenous researchers and academics have claimed a space for Aboriginal knowledge systems within research over the last twenty years. This section unpacks what is meant by an indigenous theory and identifies two major theorists, the first from the United States of America, and the second from Australia.

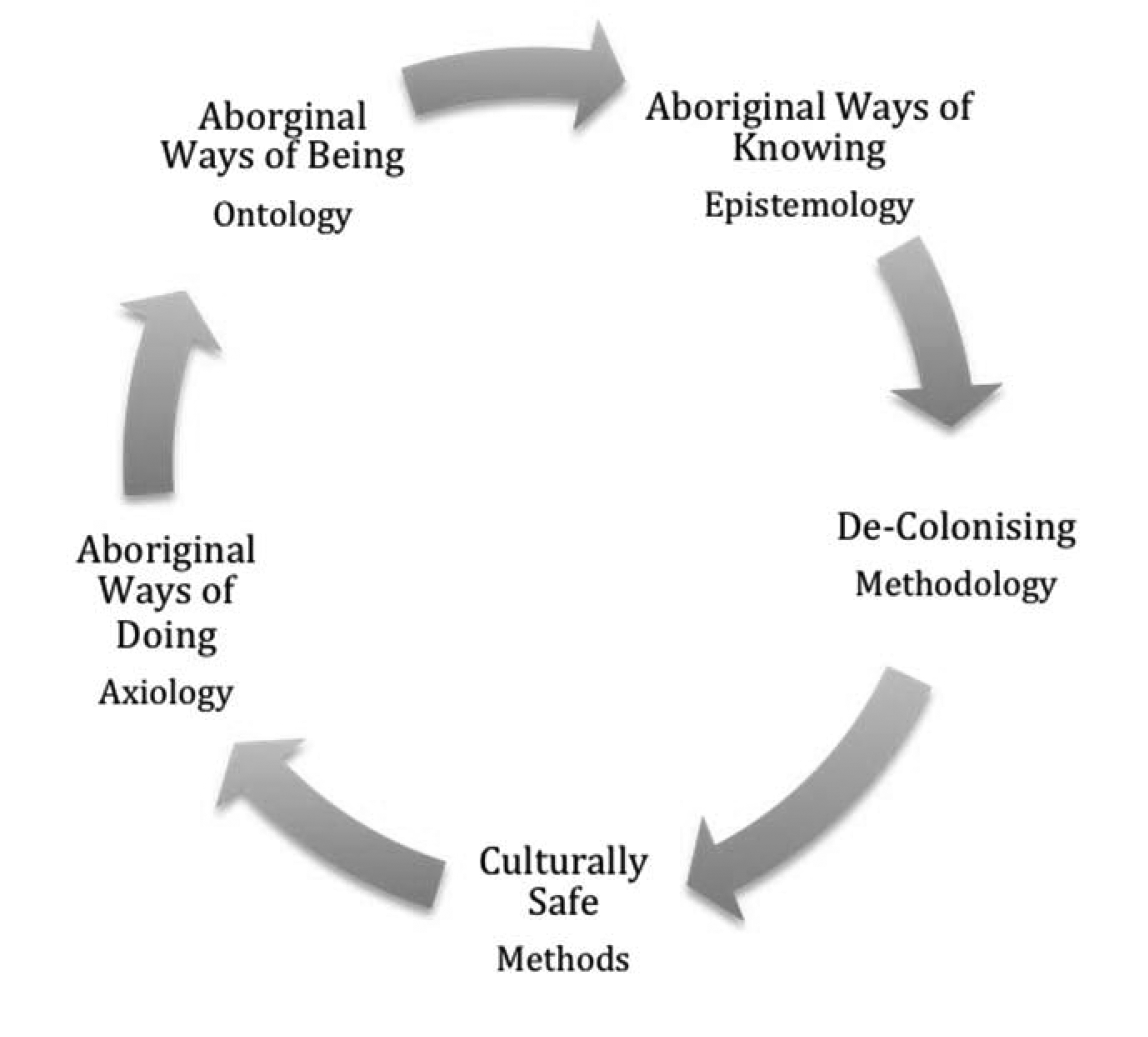

By exploring what is meant by an indigenist ideology, we are able to identify who could be considered an indigenist, and then address what is meant by indigenism, indigenist theory and practice. Figure 5.1 is a beginning point to understanding these concepts, offering some insights around how each of these concepts flow, connect and interact.

Figure 5.1 Origins of indigenism: contributing factors.

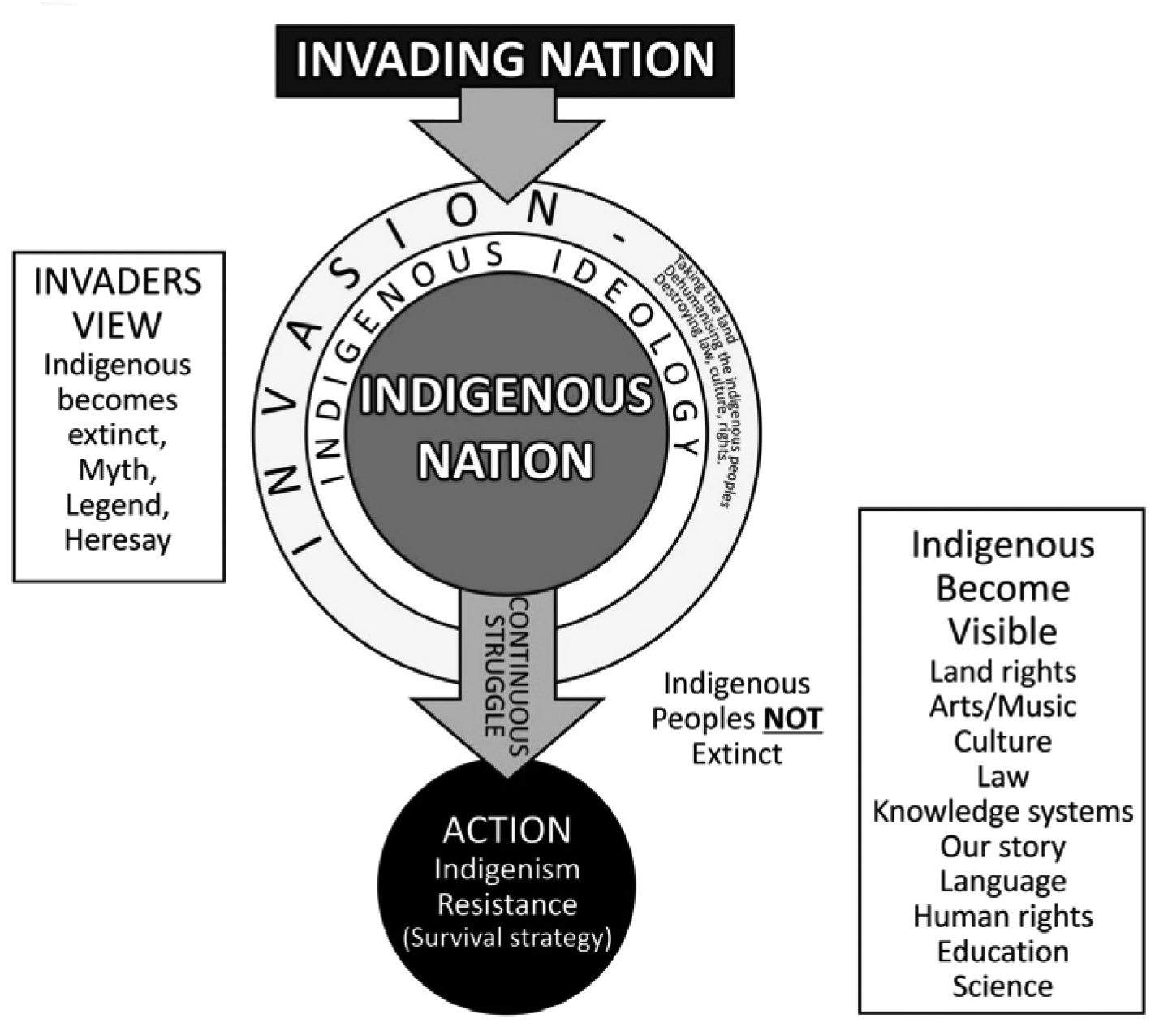

From this diagram, it becomes clear that an indigenist ideology is developed as a result of the invasion of an indigenous nation or land mass by another nation; in the case of Australia, the invading nation was Britain. The major reason for invading and colonising another group’s homeland has throughout history been connected to one country needing or wanting more land or access to the natural resources of another group (LaRocque 2010).

In the process of the invasion and colonisation of Australia there were numerous instances of genocide, ethnic cleansing, murder and the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (Haebich 2000; King 2013; Moses 2004). These practices were not confined to Australia alone – the indigenous peoples of the United States of America and Canada also shared similar experiences (Churchill 1997; King 2011; Sinclair 2007). It is in response to these and other atrocities that an indigenist ideology is developed.

Ward Churchill (1996), a controversial native American academic and enrolled member of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee, First Nations Peoples of the United States of America, refers to an indigenous ideology when he says, ‘very often in many of my writings and lectures, I have identified myself as being “indigenist” in outlook’(509). In the context of indigenism, what Churchill refers to as an ‘outlook’ I refer to as an indigenous ideology. It is a way of thinking that is based on a particular worldview, and the lived experiences and values of colonised indigenous peoples. It calls for action that seeks the recognition of their sovereignty and human rights in order to achieve social justice and self-determination. The indigenous person or activist who employs these tactics is then identified by Churchill as being an indigenist.

Using Churchill’s description of himself, pulling it apart and examining each statement in detail offers great insights that support the notion that an indigenist is an Indigenous person whose:

highest priority . . . is the rights of their people and to achieve this goal they draw on the traditions, knowledge and values of indigenous peoples from around the world. (Churchill 1996, 509)

According to Churchill, the indigenist uses the knowledge gained through these traditions, values and ways of knowing, being and doing in order to ‘advance critiques of, . . . conceptualise alternatives to, the present social, political, economic, and philosophical status quo’ (Churchill 1996, 509).

Lester-Irabinna Rigney, an Aboriginal educator from South Australia adds depth to Churchill’s work by asserting that Indigenism is, ‘multi-disciplinary with the essential criteria being the identity and colonising experience’ of the Indigenous writer (Rigney 2001, 1). Using the insights offered by both Churchill and Rigney, it becomes clear that indigenous theory and practice is developed and informed by the struggle for the rights of indigenous peoples. This struggle then becomes the highest priority in the political life of an indigenist, often emerging as activism. Further, it is this body of knowledge – the ontologies and epistemologies of indigenous peoples of the world, rather than the ontology and epistemology of the dominant non-indigenous world – that guides the thoughts and actions of the indigenist.

What is Indigenist theory and practice?

Indigenist theory is one of emancipation and empowerment, developed by indigenous academics and researchers both nationally and internationally, which works toward a paradigm shift that privileges indigenous knowledges. To illustrate how indigenist theory works in practice, two examples are shared here around validating indigenism and indigenist theory.

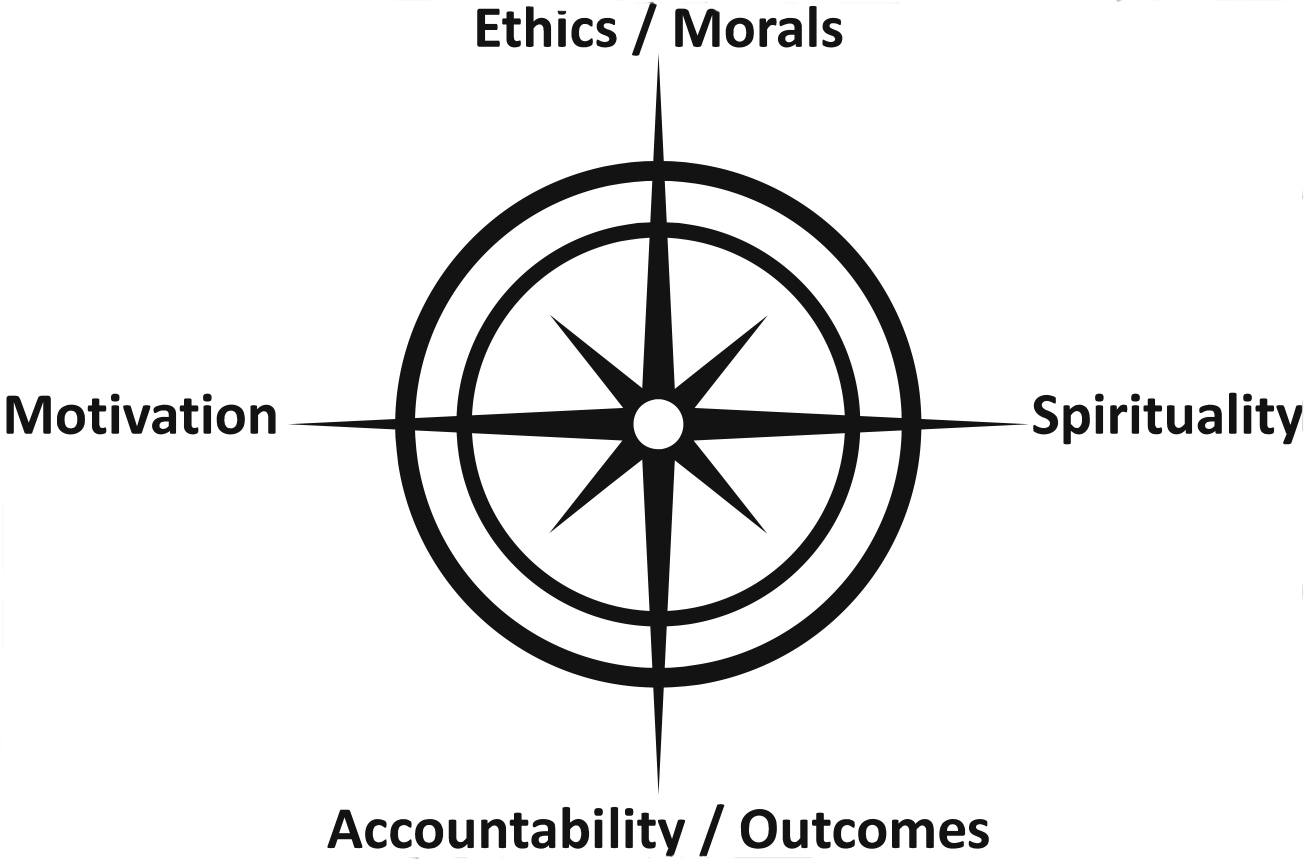

Example 1: Developing a moral compass

This example deals with the research process of my PhD journey and is found in the paper, ‘Decolonising research from an Australian Indigenous research perspective’ (King 2005). At that time I was not aware of the developing indigenist theory. However, on analysing what was written in that article with regard to the inward moral search that I undertook, through the questions I asked myself and what emerged through this process, it can be clearly identified as being grounded in an indigenist ideology that resulted in indigenist theory in practice. What assisted me in getting to this point was the theoretical frame within which the questions I asked of myself were placed.

These questions were, firstly, was it appropriate for me as an Aboriginal woman to undertake research that would be fully focused upon my people? Secondly, what was the motivation behind my wanting to undertake this research? Thirdly, what if any benefits would flow on to my family, communities and nations in particular, and what if any benefits might also flow on to other Australian Indigenous peoples? Fourthly, what foundations might my research be built upon? In other words, what ideology would frame my research? (2).

These questions were used to develop the moral compass shown in Figure 5.2, which I drew up and kept in a prominent position in my study so that I would see it each time I sat down to work. It then guided my research process (Fejo-King 2013). Over time, the moral compass was refined to its current depiction as shown below.

Figure 5.2 My moral compass.

Example 2: Validating Indigenism and Indigenist theory

In order to find the connections between my use of stories, learning circles, the connection of all things, and to find a way to describe how this connection works and what it meant for me, I undertook a search, not knowing in advance where I would be led. The search was undertaken over a period of four weeks and began with the word ‘metaphor’. However, I found this this was too narrow and constricting to describe the phenomena that I was focused on. I then moved on to analogy, allegory, epic, grand theory, cosmos, unity and finally to cosmology which is described as being the ‘science or theory of the universe’ (Collins Australian Concise Dictionary 2001).

On locating this word I felt that it warranted further investigation, so I did a Google search, but added the word ‘indigenous’ before cosmology. It was encouraging to find that many other First Nations scholars had also found their way to this definition and contributed to it.

Sinclair included in indigenous cosmology concepts such as ceremonies, and ‘All my relations’, which she viewed as one of the most significant symbols of indigenous cosmology. Translated to English from different indigenous languages, the term means the same thing and is used in the same context. For Sinclair, the concept of ‘All my relations’ captured the essence of Indigenous spirituality. She offered the following quote to illustrate what this concept meant for her and in doing so adds depth to this chapter. King (1990) as cited by Sinclair (2007) states that:

‘All my relations’ is first a reminder of who we are and our relationship with both our family and our relatives. It also reminds us of the extended relationship we share with all human beings. But the relationships that Native people see goes further, the web of kinship extending to the animals, to the birds, to the fish, to the plants, to all the animate and inanimate forms that can be seen or imagined. More than that, ‘all my relations’ is an encouragement for us to accept the responsibilities we have within this universal family by living our lives in a harmonious and moral manner. (King 1990, 1 cited in Sinclair 2007, 89)

Bringing the indigenist view as shared by King and Sinclair into Australian social work would mean that there needs to be a clear understanding by the schools of social work and social work educators, that an indigenist ideology and indigenism are embedded within the hearts, minds and hands (Kelly & Sewell 2001) of indigenous social work students, academics and educators. These then equate to practice and guide and shape what we do, just as it did for Churchill, Rigney, King and Sinclair.

This practice of the heart, learned through lived experiences and gained over many lifetimes of our ancestors, is then reflected in the knowledge and understandings indigenous students bring with them to the education system and which is often not validated (Baikie 2009; Fejo-King 2013). It is also reflected in the way that indigenous academics teach, the theorists introduced and studied, and the strategies and tactics indigenous practitioners advocate, the types of struggles they support and the nature of the alliances they enter into (Churchill 1996, 509).

This then raises two major questions: the first being how can an indigenous ideology, indigenism, and indigenist theory be successfully integrated into Australian social work education? The second is what are the challenges to including, developing and delivering these ways of knowing, being and doing (Arbon 2008; Martin 2008), within a social work setting when the majority of the educators are not indigenous?

Are Indigenism and Indigenist education, theory and practice new to Australian social work?

In addressing the first question, I do not believe or support the assertion that these concepts are new to Australian social work. Rather, they can be seen as an example of an instance of theory catching up to practice, as shown by within an Australian context, the inception of Aboriginal organisations such as Aboriginal Health Services (AHS) and the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO), the Secretariat for National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC), the Link Up services and Aboriginal legal services and land councils. Even the inquiry into the removal of Aboriginal children from their families, more commonly known as the ‘Stolen Generations’, is grounded in indigenism and indigenist theory in practice; when comparing them to the definitions provided by Rigney and Churchill, the connections are clear. However, the social work that contributed to the development of the services identified above pre-date the naming of the terms and practices described as indigenism, indigenist theory and practice.

Indigenism, indigenist theory, practice and research are ‘new’ buzz-words within Australian social work and are being treated as though they are new concepts within Australian social work. As clearly illustrated throughout this chapter, I argue that this is not the case. I assert that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers developed education, theory and practice from within this framework in the 1970s and perhaps even earlier, as the impetus for their practice, which was very different to the dominant form of social work being practised in this country. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers the focus, aim and objectives of their practice was indigenist because it was founded on and informed by these ideological perspectives, but undertaken by ‘unqualified’ indigenous social workers and so was pushed to the margins of Australian social work.

To treat this form of practice as though it is the new wonder kid on the block that should be embraced by all is, I believe, illustrative of the arrogance of whiteness within Australian social work and the continued marginalisation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers, who have been engaged in this form of practice for decades as already noted throughout this chapter. To help put things into perspective, it is well worth remembering the following view:

By not looking at where [we’ve] come from, [we] cannot know where [we] are going, or where it is [we] should go. It follows that [we] cannot understand what it is [we] are to do or why. In [our] confusion, [we] identify with the wrong people, the wrong things, the wrong tradition. [We] therefore inevitably pursue the wrong goals and objectives, putting last things first and often forgetting the first things altogether, perpetuating the very structures of oppression and degradation [we] think to oppose. (Churchill 1996, 510)

I suggest that it is within social work research that indigenous ideologies, theories and practices are new. This is as a direct result of the engagement of indigenous social work academics in this very Western activity and that these concepts have been introduced to social work theory, education and practice, as a means of ensuring cultural safety for the indigenous researchers and indigenous groups involved in the research.

Further, it is asserted that, in the 1970s, indigenist theory and practice in the form of Aboriginal Terms of Reference (ATR) were developed in Australian social work as a critical response by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers to the cultural abuse experienced by our peoples.

These theories and practices emerged from the desperate needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to access services that were not being delivered, to challenge dominant systems of oppression, to achieve social justice and self-determination. This focus on systematic change also places the social work developed and practised by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers at that time firmly within the Addams tradition.

Muriel Bamblett of the Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care Agency (SNAICC) defined cultural abuse as being:

when the culture of a people is ignored, denigrated, or worse, intentionally attacked. It is abuse because it strikes at the very identity and soul of the people it is aimed at; it attacks their sense of self-esteem, it attacks their connectedness to their family and community. (Bamblett 2007)

The question that must be asked here is, ‘Does Bamblett’s definition of cultural abuse fit what has and is being done to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers through the discounting of their work, their self-esteem and their achievements in the rush by the broader social work community to embrace the terms indigenism, indigenist theory and practice today?’ If the word culture is replaced in the quote above with the word ‘practice’, it raises a whole different perspective, therefore different considerations of social workers credibility and achievements and could well be viewed as lateral violence in an Australian social work setting.

The challenges of including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ontology and epistemology into the Australian social work curriculum

Indigenism, indigenist theory and practice are about indigenous peoples, acting for indigenous peoples, using indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing (Arbon 2008; Martin 2008) to achieve the best possible outcome for their peoples. It is about insider knowledge being applied politically, socially, economically, ethically and morally. It is also about indigenous leadership. This being the case, it is essential that any social work research, discussion, books or programs about indigenist ideology, indigenism, indigenist education, theory and practice in social work in Australia, be developed and led by indigenous researchers, academics and practitioners. The practices advocated here fit within an indigenist ideology, Aboriginal terms of reference, and culturally congruent practices that ensure cultural safety as shown in Figure 5.3 below.

Therefore, this ensures that this initiative does not become an exercise in mining and stripping of Indigenous knowledge systems, and the discounting of the work of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers for an extended period. Ensuring that indigenism and indigenist theory and practice are not taught by non-indigenous researchers and academics, or practised by non-indigenous social workers, will certainly be a major concern for indigenous Elders, communities, academics, researchers and social workers.

This is a huge challenge given that there is such a small number of Indigenous academics currently employed within the schools of social work. This then bring us to another vital question: ‘Where does that leave non-indigenous social workers?’ I propose that it is as allies, which will be introduced and discussed next.

The role of non-indigenous social work allies

The term ally was used during the 2nd International Indigenous Social Work Conference held in Winnipeg, Canada (July 2013), to describe non-indigenous social workers and others who support the goals, aspirations, ways of knowing, being and doing (Arbon 2008; Martin 2008), and cultural protocols of indigenous peoples of the world. The support offered by allies included mentoring, support, talking for, working shoulder to shoulder with, and ensuring that indigenous knowledges were not colonised, misused or misinterpreted. Allies acknowledged at each point the leadership, expertise and value of the lived experience of their indigenous peers and were guided by them around how best to work within indigenous contexts, to achieve the empowerment and social justice goals of these groups.

From the example just shared, it is proposed that the role of allies can be progressed in similar ways in the Australian setting. However, some more specific ally support could be offered through the following five points. These points are: first, recognising the work undertaken by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers from the 1970s onward, as the practice of these social workers was firmly placed within the Addams approach to social work and has achieved outcomes that have changed the Australian political and social environment, to meet the social justice needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

Second, social workers examine and learn from what has been happening in the margins of social work in Australia and document this practice and include it into the history of social work in Australia. This will enrich social work in this country, and reveal hidden knowledge and strengths within social work practice that have existed in the margins for over 40 years.

Third, that in the search for ‘getting it right’, we do not ‘get it wrong’, by not making the connections between Aboriginal Terms of Reference and what has been happening in the margins of dominant social work in Australia for the past 40 years. Our allies should be working to empower the indigenous social work that began in the 1970s and that continues today. This will bring about and enhance reconciliation rather than causing further marginalisation.

Fourth, that the Reconciliation Action Plan that was initiated by the AASW be updated, concluded, launched and rolled out across all states and territories, with the role of allies being added.

Fifth, understanding the role of allies and working from that position, rather than as colonisers mining indigenous knowledges. Working as allies will enable non-indigenous social workers to participate in indigenism and indigenist theories and practices in a positive way.

Conclusions

This chapter not only introduces the concepts of indigenism and indigenist theory and practice, it calls for the recognition of the work undertaken by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers in the margins of Australian social work for the past 40 years. It also calls for the recognition of Aboriginal Terms of Reference (ATR) as the forerunner of the terms indigenism and indigenist theory in Australian social work.

A number of questions were raised and answered throughout the chapter around what is an indigenist ideology, who is an indigenist and how can indigenism and indigenist theory be taught within the schools of social work and in practice settings. Examples of indigenism and validating indigenist theory and practice were shared within the chapter, as a means of illustrating different uses of these theories.

The chapter also provided insights into how non-indigenous social work academics and researchers can participate in indigenist education, theory and practice as allies. Examples of how allies worked and were spoken about at the recent 2nd International Indigenous Social Work Conference in Winnipeg, Canada, were shared to provide insights and paths to the future. Additionally five points have been identified that would allow Australian social workers to immediately take up the role of allies in the Australian context.

Importantly, a number of challenges and cautions have been raised about not forgetting where we have come from, in an effort to prevent terms that could discount the practice of many indigenous social workers of the past 40 years, who have worked in the margins of dominant social work in Australia. It should be remembered that it was these social workers who, through their efforts and the efforts of their allies of the time, changed the landscape of Australian politics and policies through activism and structural change very successfully in the past.

References

Arbon, V. (2008). Arlathirnda Ngurkarnda Ityirnda: being – knowing – doing: de-colonising Indigenous tertiary education. Teneriffe, QLD: Post Pressed.

Baikie, G. (2009). Theorising a social work way-of-being. In R. Sinclair, M.A. Hart & G. Bruyere (eds), Wícihitowin: Aboriginal social work in Canada. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing.

Bamblett, M. (2007). Presentation at the ATSIS Out of Home Care, Conference. Canberra.

Bin-Sallik, M. (2003). Cultural safety: let’s name it! The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 32: 21–28.

Bishop, R. (2005). Freeing ourselves from neocolonial domination in research: a Kaupapa Māori approach to creating knowledge. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (eds), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Blackstock, C. (2009). The occasional evil of angels: learning from the experiences of Aboriginal peoples and social work. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 4(1): 28–37.

Calma, T. & Priday, E. (2011). Putting Indigenous human rights into social work practice. Australian Social Work, special issue, Australian Indigenous Social Work and Social Policy, 64(2): 147–55.

Camilleri, P. (2005). Social work education in Australia: at the ‘crossroads’. Retrieved on 22 April 2014 from hdl.handle.net/10272/245.

Churchill, W. (1997). A little matter of genocide: holocaust and denial in the Americas 1492 to the present. San Francisco: City Lights Books.

Churchill, W. (1996). From a native son: selected essays on Indigenism 1985–1995. Boston, MA: South End Press.

Collins Australian Concise Dictionary (2001). 5th edn. Bath: William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., Bath Press.

DiNova, J.R. (2005). Spiraling webs of relation: movements towards an Indigenist criticism. NY: Routledge.

Fejo-King, C. (2013). Let’s talk kinship: innovating Australian social work education, theory, research and practice through Aboriginal knowledge. Canberra, ACT: Christine Fejo-King Consulting.

Foley, D. (2003). Indigenous epistemology and Indigenous standpoint theory. Social Alternatives, 22(1): 44–52.

Foley, D. (2002). Indigenous standpoint theory. Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues, 5(3): 3–13.

Haebich, A. (2000). Broken circles: fragmenting Indigenous families 1800–2000. Fremantle, WA: Fremantle Arts Centre.

Kelly, A. & Sewell, S. (2001). With head heart and hand: dimensions of community building (4th edn). Brisbane, QLD: Boolarong Press.

Kickett, D. (1992). Aboriginal terms of reference: a paradigm for the future. Perth, WA: Curtin University.

King, C. (2011). How understanding the Aboriginal kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory. PhD thesis, Australian Catholic University, Canberra.

King, C. (2005). Decolonising research from an Australian Indigenous research perspective. Presentation for the 7th Indigenous Researchers Forum, Cairns, QLD.

King, T. (ed.) (1990). All my relations: an anthology of contemporary Canadian native fiction. Toronto, Canada: McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

LaRocque, E. (2010). When the other is me: native resistance discourse 1850–1990. Winnipeg, Canada: University of Manitoba.

Margolin, L. (1997). Under the cover of kindness: the invention of social work. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Martin, K.L. (2008). Please knock before you enter: Aboriginal regulation of outsiders and the implications for researchers. Teneriffe, QLD: Post Pressed.

Moses, A.D. (ed.) (2004). Genocide and settler society: frontier violence and stolen Indigenous children in Australian history. NY: Berghahn.

Pattanayak, S. (2013). Social work practice in India: the challenge of working with diversity. In H.K. Ling, J. Martin & R. Ow (eds), Cross-cultural social work: local and global (pp. 87–100). Yarra, VIC: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ramsden, I.M. (2002). Cultural security and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu, PhD thesis, Victoria University, Wellington. Retrieved on 6 March 2006 from culturalsafety.massey.ac.nz.

Rigney, L.I. (2001). A first perspective of Indigenous Australian participation in science: framing Indigenous research towards Indigenous Australian intellectual sovereignty. Kaurna Higher Education Journal, 7: 1–13.

Rigney, L.I. (1999). The first perspective: culturally safe research practices on or with Indigenous peoples. Paper presented at the Chacmool Conference, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada.

Rigney, L.I. (1997). Internationalisation of an Indigenous anti-colonial cultural critique of research methodologies: a guide to Indigenist research methodology and its principles. In Research and development in higher education: advancing international perspectives, vol. 20), pp. 626–29. Milperra, NSW: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA).

Settee, P. (2007). Pimatisiwin: Indigenous knowledge systems, our time has come, PhD Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada. Retrieved on 22 April 2014.

Sinclair, R. (2007). All my relations – native transracial adoption: a critical case study of cultural identity, PhD thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada.

Sinclair, R., Hart, M.A. & Bruyere, G. (eds) (2009). Wichihitowin: Aboriginal social work in Canada. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing.

Smith, L.T. (2012). Decolonising methodologies: research and Indigenous peoples (2nd edn). NY: Zed.

Smith, L.T. (1999). Decolonising methodologies: research and Indigenous peoples (1st edn). NY: Zed.

Specht, H. & Courtney, M.E. (1994). Unfaithful angels: how social work has abandoned its mission. NY: Free Press.

University of Sydney (2012). Social work at the University of Sydney: seven decades of distinction. Retrieved on 22 April 2014 from sydney.edu.au/education_social_work/about/history/social_work.shtml.

West, E. (2000). An alternative to existing Australian research and teaching models. The Japanangka teaching and research paradigm: an Australian Aboriginal model, PhD thesis, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing.