21

Social work education as a catalyst for social change and social development: case study of a Master of Social Work Program in China

Social work education as a catalyst for social change and social development

In response to the urgent need for professionally trained social workers to help in alleviating emerging social problems in China after the introduction of the market economy, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the Peking University launched a Master of Social Work (China) Program for social work educators in 2000, with the aim of developing a critical mass of social work educators to take up the future leadership in developing social work and social work education in China. To date, seven cohorts of over 230 students consisting of social work educators, NGO and government officials have been admitted to the program, and graduates of the program are playing a pivotal role in spearheading the development of social work education and fostering social development through the process. In this paper, the authors will present the vision and mission of the Master of Social Work (MSW) Program, the teaching and learning strategies adopted, and the ways in which the program has facilitated social change and social development through its educational process.

China is undergoing rapid social and economic transformation as a result of the introduction of the Open Door Economic Policy since the late 1970s. As a measure for alleviating emerging social problems, the Chinese Government has re-introduced social work education programs to the universities since the late 1980s after a lapse of over 30 years. In view of the acute need to train social work educators, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and Peking University launched a MSW (China) Program in 2000, with the aim of developing a critical mass of social work educators to take up the future leadership in developing social work and social work education in China. Moreover, it is also expected that the program will help in bringing about social change and social development through its educational process.

In addition to the academic contents of the program, fieldwork practicums have been developed in different locations in China, partly to provide sites for fieldwork training and partly to facilitate the generation of indigenous practice models and theories relevant to the Chinese context. The numerous practicum projects developed by the MSW Program have played a catalyst role in impacting on positive social change in the local communities concerned and in facilitating social service development in the country. Moreover, graduates of the program have worked zealously in their different capacities to spearhead major breakthroughs in social policy initiatives and to institute social work as a profession in China. In this paper, the authors will first provide a snapshot of the development of social work education in China and will highlight the vision and mission of the MSW (China) Program and illustrate with examples the catalyst functions of social work education in facilitating social change and development in the Chinese context.

The re-emergence of social work education in China

Social work training programs were first introduced to the most prestigious universities in China in the 1920s, but they were all eliminated in the 1950s because of the belief that socialist China had no social problems and therefore had no need for social work education (Lei & Shiu 1991). The introduction of China’s ‘Open Door’ economic reform in 1978 by reformists within the Communist Party of China led by Deng Xiaoping steered China away from a welfare state model towards the neoliberal welfare model, based mainly on economic efficiency and aimed at providing only basic welfare benefits to maintain social stability. It was anticipated that there would be a significant re-emergence of social inequality and class division (Leung & Nann 1995; Preston & Haacke 2003). In view of the escalation of social problems, the Chinese Government searched for ways to resolve these problems and to maintain social stability. After the re-introduction of sociology as a discipline to the universities in 1979, some leading academic and political leaders who were previously trained in social work and applied sociology, such as Lei Jieqiong and Fei Xiaotong (Lei & Shui 1991), fervently advocated the reintroduction of social work as a discipline into the university curriculum. In 1989, Peking University started to launch its social work program at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels and was gradually followed by other universities and cadre training colleges in China.

During the 1990s, the development of social work education in China was confronted with a host of problems, including the lack of public recognition of the social work profession; unclear role distinction between the social work professionals and government cadres; lack of career prospects for social work graduates; direct borrowing of Western concepts; lack of practice experience to facilitate theory building; shortage of professionally trained social work teachers to help in the development of social work programs; and the lack of support from the government (Yuen-Tsang 1996). The number of social work programs remained limited during this period and the expansion was slow.

But, since 1999, the number of social work programs expanded dramatically because of the massive expansion in higher education in China and the rising demand for professional social workers to help in developing the rapidly expanding social service provisions in China. The number of universities offering social work programs suddenly surged to over 200 in the early 2000s, though the majority of the teachers of these programs had not received any professional training. It was in such a context and in response to the acute need to develop the capacity for social work educators to take up the future leadership to develop social work in China that the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the Peking University decided to join hands to launch the first MSW Program in China in 2000.

The social work profession was given a major boost in 2006 when the Chinese Government formally announced its intention to ‘build up a strong team of social workers to help in the development of the harmonious society’. Numerous measures were also introduced to support this national policy, including the establishment of pilot social work schemes in different parts of China; the establishment of social work positions in different pilot cities; and the introduction of the professional examination system for social workers. Realising the need to develop high level professional training programs for social workers, the Ministry of Education of China has, in early 2009, endorsed the proposal to introduce China’s own Master of Social Work (MSW) Program in Chinese universities. This is one of very few professional master’s programs endorsed by the Ministry of Education. In 2012, 61 major universities in China were selected to launch the MSW programs. In view of the introduction of China’s local MSW Program and the gradual maturing of the social work profession in China, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the Peking University decided not to continue our joint MSW Program beyond the seventh cohort, but rather, to focus our effort on building the capacity of universities in China to develop their own MSW Programs. In this connection, the ‘Peking University-Hong Kong Polytechnic University China Social Work Research Centre’ was established in 2008 with the mission to provide a national platform for dialogue, exchange, research and learning pertaining to the continuing advancement of social work in China.

Vision and mission of the MSW (China) Program of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and Peking University

In 2000, the Department of Applied Social Sciences of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, in collaboration with the Sociology Department of the Peking University, decided to launch a MSW (China) Program in China with the aim ‘to develop a critical mass of committed, competent, reflective and culturally sensitive social work educators to take up the future leadership in developing social work and social work education in China’. Moreover, the program endeavours ‘to develop indigenous social work theories and practice appropriate to the Chinese context’ and ‘to make positive impact on social work, social services, social policy and social development in China’.

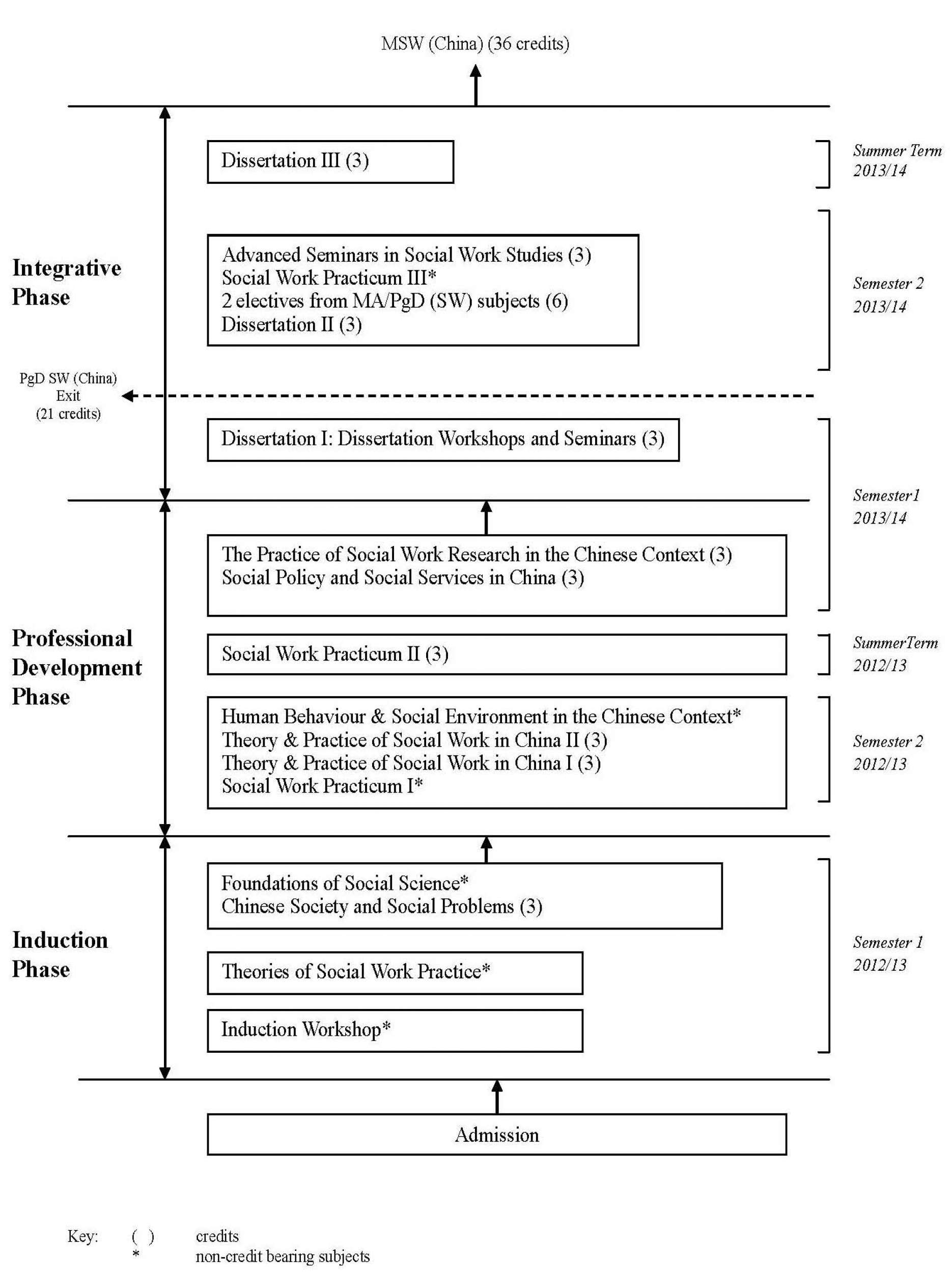

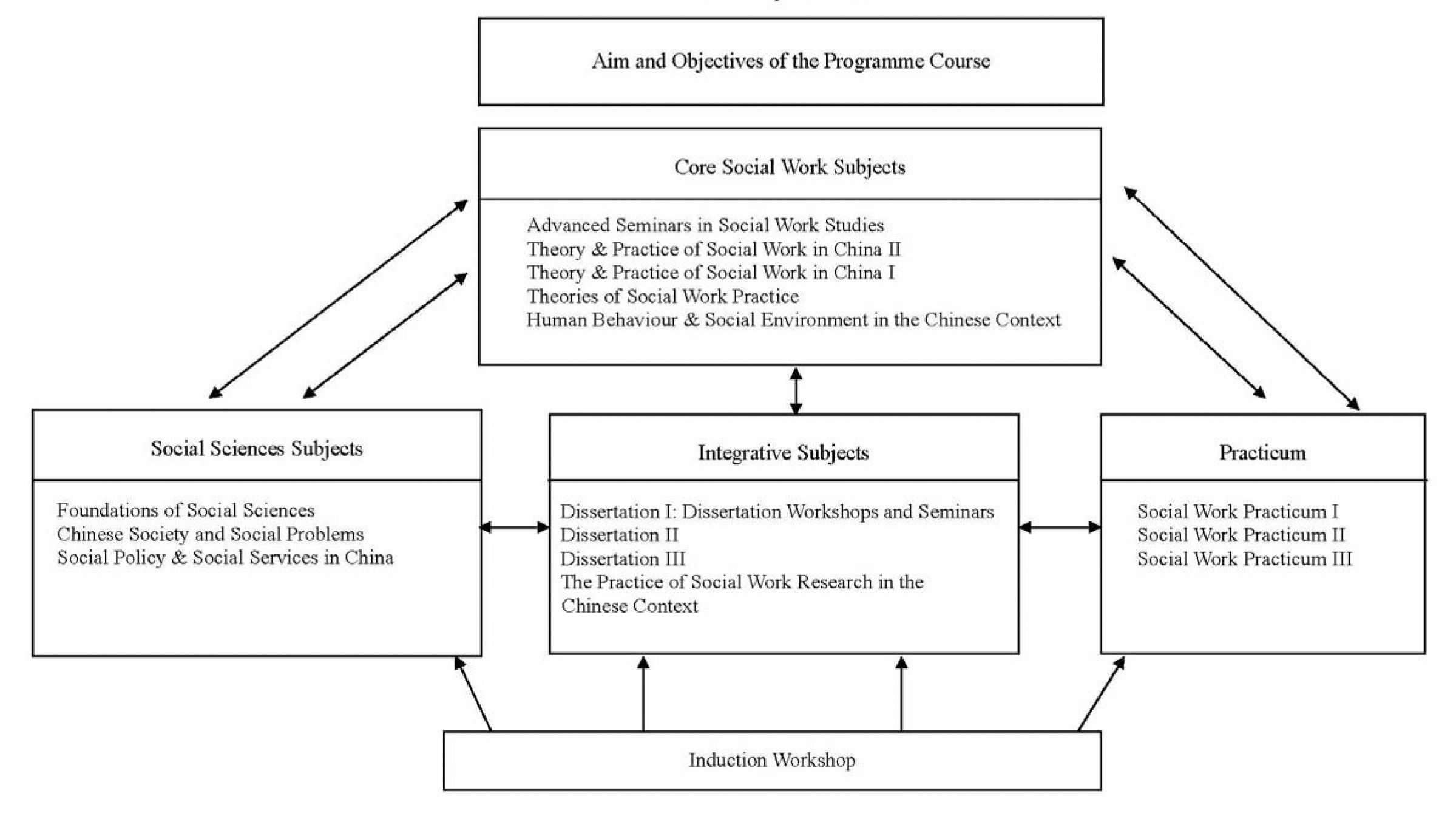

The program is basically a ‘training of trainers’ program which is designed primarily for experienced social work educators and is being offered on a three-year part-time basis so as to allow the students to stay in their jobs while pursuing their studies. The curriculum is characterised on the one hand by its insistence to adhere to international standards, and on the other hand by its emphasis on the need to contextualise and indigenise social work theory and practice in the Chinese context. Students are required to take 18 subjects, including ten required subjects, two elective subjects, three social work practicums, and a three-staged social work dissertation (see Figures 21.1 and 21.2 for details of the curriculum and the conceptual framework of the program). Though most of our students are experienced social work educators with impressive credentials and most of them will not be involved in direct practice after graduation, we insist that all of them have to undergo three rigorous supervised fieldwork practicums so as to develop their capacity for theory–practice integration and to cultivate their commitment to serving the needy and the vulnerable groups at the grassroots. Most of the subjects and practicums are carried out in the Chinese mainland using an intensive block-mode. Students will spend their last semester at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University so as to engage in a period of intensive full-time study and to gain direct practice experience in social work organisations in Hong Kong. The majority of the professional subjects, including the practicums, are taught by professors and instructors from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, while Peking University professors are primarily responsible for teaching subjects relating to social science and policy issues and provide co-supervision in dissertations.

Figure 21.1 Program structure of the MSW (China).

Figure 21.2 Curriculum of the MSW (China) program: a conceptual model.

In line with our social development mission, deliberate efforts have been made to enhance university–community collaboration and to link the curriculum to the social realities of contemporary China. Both the academic staff and students are encouraged to develop ‘scholarship of engagement’ (Boyer 1990) through combining teaching, research and professional service to the community to address social issues and to foster social betterment.

The planning team of the program has adopted a social developmental perspective which endeavours to improve the welfare of the population as a whole through integrated social and economic development initiatives emphasising capacity building of individuals, families and communities (Hall & Midgley 2004; Midgley and Livermore 1997; Xiong 1999). We believe that the integrated and comprehensive nature of the social developmental perspective in social work education provides a viable way to tackle the massive poverty, deprivation and inequality experienced by the Chinese population. Moreover, this perspective provides opportunities for capacity building, and promotes social and economic change that produces improvements in standards of living, social wellbeing and citizen participation (Hall & Midgley 2004).

Transferring these beliefs to social work education in the Chinese context, our team strongly believes that all students should be the key actors in their own learning processes, and that strengthening the capacity of students to make policy and practice decisions in their local contexts guided by social work values and to be able to carry out their interventions in a professionally competent and critically reflective manner is the core concern of our teaching endeavour. Moreover, we encourage our students to actively engage their service-users and to strengthen the capacity of their service users in their service-delivery process, so that the service-users will become partners and key actors and in social change and development processes in their own communities.

Fostering social change and social development through the education process

In order to achieve the intended objectives of the program and to foster social change and social development through the education process, the curriculum design, fieldwork practicum, as well as teaching and learning strategies have been diligently designed to reflect our concerns and commitments. The following are some of the key strategies adopted by our program.

Educating reflective practitioners as change agents

We believe that it is impossible to foster social change and social development without first changing the mindset of the change agents themselves. As social problems are becoming more and more complicated in contemporary society, conventional skills of social work practitioners are found to be increasingly inadequate for dealing with complex social issues and problems. Social work practitioners need to be competent, flexible, versatile and reflective and be able to respond proactively to the changing socioeconomic environment.

We do not expect our graduates to directly apply technical-rational solutions acquired from textbooks to resolve practical problems since there are few standard formulae for solving real life problems. Instead, we endeavour to develop among our students critical awareness towards issues and problems which they confront, and their capacity to relate these issues to a holistic understanding of social work practice.

In the program, we emphasise critical thinking and self-reflection and we help students to examine values and attitudes which are embedded within their social and cultural structures. We encourage students to deepen their understanding about how their beliefs and knowledge may affect their practice, and we encourage them to engage in critical dialogue with their teachers and service users throughout their learning process. Students are encouraged to develop a contextual understanding of social work practice in contemporary China and to engage in critical reflections on the competing values and ethical dimensions underlying these practices, so that they will become active learners who are able to develop their own personal perspective of and approach to social work practice in the Chinese context (Ku et al. 2005). We hope that our students will be aided through these processes to develop their capacity as independent and active learners who are able to construct, deconstruct and reconstruct their professional practice in the Chinese context through critical reflection. It is only when they become reflective practitioners that they could become effective change agents.

Participatory action research as pedagogy for change

In order to facilitate our students to become reflective practitioners and effective change agents, we have adopted the participatory action research model as our education pedagogy. In particular, the ‘reciprocal-reflection theory’ developed by Schön (1983, 1987), which offers an alternative way to understand and explain the processes through which a novice develops professional scholarship through reflective practice. It was used as the guiding framework for our practicum.

In the past few decades, an increasing number of social science theorists and human service practitioners have become dissatisfied with traditional models of integrating theory and practice. The ‘applied model’, as a dominant approach, is primarily based on technical rationality and derived from positivist philosophy (Schön 1983, 1987) and it stresses the professionals as instrumental problem-solvers whose competences rest on the skilful application of ‘objective, consensual, cumulative and convergent’ theories into practice (McCartt Hess & Mullen 1995; Schön 1983, 1987). Because of the dissatisfaction with the dominant models, social science theorists and human service practitioners have actively sought alternative models. In recent years, participatory action research is increasingly being recognised as a viable approach to deal with the problem of the theory–practice gap because it enables practitioners to integrate research with practice and to generate practice theories from the ground (Greenwood 1991; Lanzara 1991; Pace & Argona 1991; Oja & Smulyan 1989; Sarri & Sarri 1992; Sung-Chan 2000; Yuen-Tsang & Sung-Chan 2002; Whyte 1991). Participatory action research involves change experiments on real problems in actual practice contexts and involves interactive cycles of identifying, planning, acting and evaluating a problem through rigorous reciprocal-reflection-in-action processes between educators and students (Sung-Chan 2000; Yuen-Tsang & Sung-Chan 2002).

With the above understanding, we have developed practicum sites in different parts of China using the participatory action research model. We strive to cultivate among our students a strong sense of commitment to theory–practice integration and a keen interest to generate indigenous practice theories from the ground. We believe that it is only when our students have developed the passion to serve the vulnerable and deprived in real-life contexts that they could become effective change agents to bring about constructive social change and social development.

Partnering with local communities to effect change

Universities worldwide have a long tradition of community participation and social involvement. The Settlement House Movement at the beginning of the 20th century is an early example of community participation. According to this model, social engagement, actively addressing the pressing social, political, economic and moral ills of society, is an integral part of higher education (Marullo & Edwards 2000; Mayfield et al. 1999). However, the strong link between higher education and community has gradually weakened as academics increasingly assumed a pose of scientific objectivity and focused on the creation of new knowledge within the academy, thus detaching themselves from direct involvement in reform and activism. The dominance of the paradigm of scientific objectivity in universities has been reinforced by the emergence of reward and incentive systems, selective recruitment, disciplinary evolution, and institutional structures that emphasise the discovery and pursuit of academic knowledge. Academics are thus increasingly divorced from social reality and have lost their early aspiration to become pillars of social justice and vehicles for social change (Harkavy & Puckett 1994).

During the last decade, there has been renewed discussion of the need for universities to exercise their social responsibility through revitalising links with communities (Boyer 1990; Gronski & Pigg 2000; Weinberg 1999; Wang 2003; Yuen-Tsang & Tsien 2004). Boyer (1990) advocates a broader interpretation of scholarship and advises an application of knowledge that moves towards social engagement. He argues that universities need to adopt a model of ‘scholarship of engagement’ and that both faculty and students, in collaboration with community residents, should apply their knowledge to the solution of social issues and problems. Boyer maintains that it is only through the pursuit of ‘scholarship of engagement’ that the learning experiences of students and faculty are enhanced and revitalised.

It is based on the above values and beliefs that the both the academic and the practicum curriculum have been planned and developed. Deliberate efforts have been made to develop collaborate relationship with community stakeholders, including local government departments, universities, NGOs, community leaders and residents throughout the planning and implementation processes of the action projects related to each of the practicum sites developed by the program. Through university–community partnership, we hope to foster a strong sense of ownership of the projects among community stakeholders. The partnership relationship has not only facilitated our easy entry into the community and the smooth implementation of our projects, but it has also helped in fostering community participation and cultivating a support among local stakeholders towards the sustained development of these projects.

Networking among students, graduates and stakeholders to sustain change

A total of 238 students have been admitted to the MSW (China) Program in the seven cohorts. There are 15 graduates in the first cohort, 22 graduates in the second cohort, and around 40 students in the third to seventh cohorts. These students come from 150 universities, 81 NGOs and 28 provinces from all over China. These graduates are dispersed in different parts of the country, and it is extremely difficult for them to maintain close contacts among each other. Moreover, since many of them are located at rather isolated locations where the social work profession is relatively undeveloped, it is essential that measures are introduced to provide support for our graduates so that they could sustain their commitment to the furtherance of social work practice and social development.

We understand that social networks are powerful instruments to connect people and to sustain relationships. Social networks can also play important supportive functions and can facilitate the exchange and transmission of resources among network members. In order to provide continuing support for our students and graduates and to sustain the change efforts made, the curriculum team has therefore developed a networking strategy which aims to link the students, graduates and stakeholders in the social work education and social welfare sector in a supportive network and to facilitate them to become a reflective learning community to promote social change and social development through collaborative efforts.

In view of the urgent need to establish a strong supportive network among the students and graduates and to sustain their commitment to social change and social development, an alumni association was formed in 2005 consisting of all graduates of the program. They hold regular functions and maintain close contacts through participation in national and regional social work education functions. Moreover, a China Social Work Research Centre has been established jointly by the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the Peking University, housed in a beautiful courtyard within the Peking University campus since 2008 to facilitate joint research projects among network members, to organise seminars and provide continuing education opportunities for graduates, and to provide a forum for dialogue among social work educators, students, practitioners and government officials on issues relating to social policy and social work practice. Members of the network can participate in research projects and training activities initiated either by the Centre or by network members. The centre has become a hub not only for our graduates but also for other interested social work educators and practitioners both from China and overseas to interact, to provide support and consultation for each other, and to activate social change and social development initiatives for social betterment.

Fieldwork practicum as contexts for social change and social development

Fieldwork practicum provides excellent contexts for the students to develop their practice competence, to engage in critical reflection, to integrate theory with practice, and to nurture their commitment to social change and social development. The second practicum takes place in the summer of their second year of study, during which the students have to engage in an eight-week block placement where they will live and work together in a practicum site of their choice in China. Since 2000, we have developed many practicum sites in different parts of China, using participatory action research as our pedagogy.

Each practicum site is carefully selected, developed and sustained through the joint effort of our teaching team, students and local stakeholders. In each practicum site, we usually focus on one area of emerging social need and we use the participatory action research model in demonstration projects through the joint effort of students, teachers, service-users, and sometimes involving local government officials. In order to ensure that the demonstration projects could be continued and sustained, we usually involve a local university (where at least one of our MSW students to be placed in the practicum comes from) as our partner, so that the practicum site will be used by the respective university as a future practicum site for their own social work students. Usually a cluster of at least five students will be placed at one site and they will be supervised by the same supervisor so that they can form a learning community and can provide mutual support for each other throughout the practicum process. Moreover, it is expected that the different cohorts of students taking part in the same practicum site, together with the strategic partners involved in the process, can form a critical mass to further develop the model of practice that they have evolved and can help in spearheading the development of the practice model in China.

During the past 13 years, the MSW (China) Program has developed numerous practicum sites in different parts of China and many of these have now become common models of practice in the country through the powerful demonstration of the effect of the projects, and the zealous effort of our graduates to campaign for these models of practice through teaching, research and policy advocacy. These include:

- strength-based mentorship project to support the social integration of migrant children in Beijing

- home–school–community integrated service project on delinquency prevention in Shanghai

- community-based social inclusion projects to foster social integration of deprived families in Wuhan and Xiamen

- holistic elder care projects in institutions for senior citizens to enhance active ageing in Hangzhou and Beijing

- community-based rehabilitation project to promote community care for physically disabled persons in rural villages in Hunan

- community-based mental health project to build social support networks for persons with mental health challenges in Kunming

- rural capacity-building projects to build community solidarity and reduce rural poverty in Yunnan and Sichuan

- rural–urban alliance projects to promote eco-farming and fair trade through social enterprises in Guangdong and Sichuan

- occupational social work project to foster labour welfare and industrial harmony in Harbin

- asset-building projects to foster post-disaster social reconstruction in Sichuan.

Case illustration: the Yunnan Rural Capacity-building Project

The curriculum team has made diligent efforts to plan and develop the fieldwork practicums as contexts for social change and social development. The following case study on our rural social work development project in Yunnan illustrates the typical process in which our practicums are being implemented and how our social development goals are being realised.

Stage I: Mapping of existing indigenous practice approaches through the use of oral history

One of the foremost social problems haunting China is rural poverty. Poverty in rural villages has been accelerated by market globalisation and China’s entry to the World Trade Organization. In 2012, there are a reported 167 million migrant workers who have been pushed from their villages because of rural poverty to take up low-paying jobs in urban cities. As a consequence of rural–urban migration, many rural villages are left with only children, the elderly and the disabled, and this has created acute social disintegration and social problems. Moreover, increasing incidences of popular resistance and loss of authority of rural cadres have further weakened the social fabric and long-standing social control mechanisms and has threatened the stability and harmony of the vast rural population in China.

While the Chinese Government has already launched macro-level anti-poverty programs to combat rural poverty and has made impressive progress in rural poverty reduction, most of the efforts are directed towards economic development and income generation, and relatively little attention has been devoted to social and community development using social work approaches. As such, the curriculum team of the MSW (China) Program decided to experiment on a rural social work project in the Yunnan Province through the development of a practicum site, using the capacity-building model as a guiding theme. The chosen field site for this practicum is located in the Wu Township in the northern part of Yunnan and the area is an officially designated poor township by the government. The aim of the project is to enhance the capacity of local villagers and stakeholders through integrated community development.

The Yunnan project started in the summer of 2000 and has been used as a site for participatory action research and for providing practicum opportunities for our MSW (China) students and social work students from Yunnan University. During each practicum, a cluster of at least five MSW students together with one experienced social work supervisor and one assistant supervisor from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University resided in the village for a period of eight weeks. Social workers cum researchers graduating from the Yunnan University had been employed to take charge of the development of the project on a full-time basis. The participatory action research method was used to guide the development of the practicum project.

The focus of the first stage of development was to listen to the voices of local villagers, to understand their concerns and problems, and to identify their capacity for development. The teachers and students did not come with preconceived ideas and a fixed agenda for intervention prior to their entry to the village. Instead, they partnered together to discover the needs of the people, to map the existing approaches that were being used by local villagers to deal with their problems, and to reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of existing local practices, using the reciprocal-reflection-in-action approach in the process.

As the students did not understand the local dialect, they partnered with young villagers who spoke Putonghua (the national language) to collect oral histories and these young villagers became the interviewers, translators and partners in the process. Guided by the basic principles of the reciprocal-reflection-in-action approach, the teachers, students and the villagers collaborated in a mutual process in analysing and reflecting on the oral history testimonies collected. The teachers, students and some active villagers developed into a learning community of independent and active learners who were able to construct, deconstruct and reconstruct their social work practice in the local context through critical reflection.

In this stage, the students were able to build trust and rapport with the local villagers, discover the needs and problems of the local community, and map the existing practice approaches used by local villagers. They were also encouraged to discover their own strengths and weaknesses as learners and practitioners through the reciprocal-reflection-in-action process. While the learning process was often painful for most of the students because they were more used to the authoritative teaching and learning approach, most of them were elated at the end because of the sense of joy which they experienced in the process of discovery and growth.

Stage II: Constructing a rural capacity- building practice framework through community participation and partnership

The teachers, students and researchers developed a critical understanding of local needs and existing practices in the local community through the reciprocal-reflection-in-action process. The next step was to organise some sharing sessions and analyse the oral histories with local villagers who participated in the oral history collection process. This was a deliberate process to involve the active local villagers in community analysis so as to build their capacity for critical reflection and for future leadership.

The students were then divided into different teams and each team consisted of one student and a few selected active villagers. Each team was responsible for one village and they visited local villagers, local cadres and stakeholders and discussed with them issues of concern identified through analysis of the oral history testimonies. Attempts were made to facilitate the villagers to discuss their vision of their desired community and their suggestions on preliminary steps to achieve their goals through realistic community involvement projects. The villagers participated enthusiastically in the discussions and developed a strong sense of ownership of the problems identified and the concrete suggestions made. Different small groups gradually emerged through the process, including youth groups, women’s groups, senior citizens’ groups and local leaders’ groups. The small groups started to propose and plan concrete community-based social development projects such as the generation of methane gas, adult education programs, income-generating handicraft projects, and the building of a community centre.

In the process, the students employed a capacity-building approach, and took the role of facilitators rather than experts in community development. They modelled after their supervisors who had assumed non-expert roles in the teaching and learning process and had partnered with them throughout the process of discovery. They learned to internalise social work values and ethical principles and had also developed a sense of passion towards the plight of the local villagers and became committed to the cause of poverty alleviation and social development in China.

Stage III: Implementing the rural capacity-building practice framework

After having developed the rural capacity-building practice framework, the framework was implemented through the use of the participatory action research approach. The students facilitated the villagers to work on the ideas that they had proposed in the previous stage and helped them to actualise their plans through group work and community organisation strategies. Concrete projects were carefully deliberated on and subsequently implemented, taking into consideration the realities and constraints of the local context. Projects that were finally chosen for implementation include: the generation of methane gas for fuel; the formation of support groups for women and the elderly; the provision of adult education programs for the illiterate; leadership training for young villagers; training programs for children and young people on ethnic songs and dances by elderly villagers in order to preserve the cultural heritage; constructing a local museum on ethnic history and culture; and the development of income-generating handicraft projects. All these projects were being discussed, planned and implemented collectively by involving the practicum students, teachers, researchers, villagers and local stakeholders concerned. The local people also proposed to build an integrated community service centre to serve as a hub for local villagers to meet and to engage in communal activities. With funding for the building materials raised in Hong Kong, the community centre was planned, designed and built by villagers.

Many of the villagers had been transformed by their experience in the project. Many of them were very passive and pessimistic in the past and they felt hopeless in view of the grave poverty in their village. In the past, their only way out was to go outside of their villages and to seek jobs in urban factories. With the development of the rural capacity-building project, many of them realised that they could find ways to enhance their social and economic wellbeing through collective efforts. Moreover, instead of despising their traditional ethnic culture, many of them began to discover the richness of their cultural heritage and were keen to preserve and transmit it to their future generations.

The major challenge of our students in this stage was to make a shift from their familiar expert-oriented approach to the collaborative and facilitative approach. This problem became more apparent in this stage of development when they had to work closely with the villagers to develop concrete plans for action. The students were used to providing consultation and giving expert ideas in their normal roles as university professors and researchers. They had great difficulty in holding back their suggestions in a directive manner in order to listen to the voices of the people in a humble and empathetic manner. But they were alerted to their lack of awareness of this through continuous reciprocal-reflection-in-action processes.

The students discovered that the villagers were actually full of ideas and had great capacity for development despite their lack of education, resources and exposure. Given the opportunities and encouragement, the villagers could become highly motivated and could join together to do amazing things to improve the quality of life not only for themselves and their families, but also for the collective good of their community. Moreover, the students also experienced the thrill of actually being involved in the real-life process of conceptualising, planning and implementing social change and social development. The experience greatly inspired them and transformed their conception of social change and how social change could be actualised in the Chinese context.

Stage IV: Reflecting on the experimentation and ensuring sustainability of change efforts

Besides the engagement in continuous reciprocal-reflection-in-action throughout the entire action research process, a major evaluation was carried out in the summer of 2005 to reflect on the whole project since its inception in 2000. The purpose of the evaluation was to reflect on past experiences, to identify the gaps and limitations of the approach, to refine and improve the rural capacity-building practice framework and to ensure the long-term sustainability of the project. Students, teachers and researchers involved in the project during the period were invited to attend the meeting and to share their views about the project.

The most critical problem confronting us in the process was the difficulty to change the mindset of people. Even though the project emphasised social development and had adopted a capacity-building approach to the process, most of the teachers and students involved in the project found it extremely difficult to practise their values and beliefs in the real-life context. While they advocated for equity, justice and fairness, they found that they were often the ones who violated such principles and asserted their power and domination in the decision-making processes. While they were educating the villagers to exercise gender equality, some of the male students and teachers exhibited chauvinistic behaviours towards their female colleagues which had caused much embarrassment and unhappiness. While they themselves were zealously promoting social change and social development, they could be using methods and strategies which, though seemingly efficient and effective, were contradictory to the core beliefs of social development. Fortunately, the use of the reciprocal-reflection-in-action paradigm had helped in minimising these problems, sharpening critical reflection, and creating an environment for open dialogue and mutual support among key players involved in the project.

Another issue of concern was the sustainability of the change efforts. The project had started many worthwhile initiatives at the community level, but it was not at all easy to sustain these initiatives on a long-term basis. While it was relatively easy to sustain the interest of the villagers in the various interest groups and support groups, it was extremely difficult to sustain the momentum of the income-generating projects. For instance, the handicraft project was developed with a view to help local women to generate income through production of local handicrafts and cloths. But the project was not too successful and could only provide minimal supplementary income for a few families because of reasons such as the difficulty to market the products, the low quality and unattractive design of the products, the lack of resources to buy raw materials, and the difficulty to evenly distribute the income generated from the project. The team reflected on the underlying causes of the problems and discussed ways to enhance the sustainability of the income-generating projects. The core issue was again related to the mindset of the people. It was felt that the women involved in the project were only concerned about generating income from the project to improve their own household income and were not concerned about improvement of the collective good and social development. The team reflected that they had not done enough preparation to enhance local villagers’ knowledge and understanding about social development before the commencement of the project. It was therefore suggested that more efforts have to be made not only to enhance the capacity of the participants in income generation, but, more importantly, the capacity to promote collective good through mutual support. Moreover, it was suggested that efforts have to be made to involve the local and provincial officials as partners of the projects so that government resources and support could be drawn upon to help the local villagers. The team also suggested that we had been over-emphasising the ‘social’ aspect of development, and not paying adequate attention to the ‘economic’ and other related aspects of development. As such, it was suggested that we should strengthen our team by drawing upon the help of economists, designers, health professionals and others so that we could provide a holistic and inter-disciplinary approach to social development. All these insights generated through the reflection process have been used to guide the further improvement of the rural capacity-building project in its subsequent stage of development.

Finally, the team also deliberated on issues related to knowledge building and knowledge dissemination. During the previous years the project staff accumulated a host of experience and data collected through the action research process. We have been illuminated by our experience and especially by the insights gained through the participatory action research process. We have generated ideas on rural social work practice through our project and have gradually evolved an indigenous rural capacity-building model for the Chinese context. In order to share our experience and ideas with fellow social workers in China, we have developed a series of workshops and training programs so as to popularise the rural capacity-building model in other parts of China. A Rural Social Work Research Centre has subsequently been established at Yunnan University in 2007 to further our work on rural social work development. The centre has now become a national hub for social workers and other related practitioners and researchers to meet, to have dialogue, to promote the rural capacity-building model, and to advocate for social change and social development in rural China.

Conclusions

The MSW (China) Program is committed to the development of social work and social work education in China and to the furtherance of social change and social development. We position ourselves as catalysts for social development through our numerous curriculum initiatives and especially through our active engagement in participatory action research projects in connection with our fieldwork practicums. Through these action research projects, our students have been facilitated to actively engage in initiatives to foster social change and social development. Efforts have been made to address critical social issues in contemporary China such as poverty, unemployment, marital breakdown, population ageing, street children, mental illness, and social exclusion. Through personal involvement in these action research projects, our students have gradually gained the awareness and confidence that social work education can become a powerful catalyst for social change and development. It is indeed our hope and aspiration that more social work educators in China could take up the social responsibility and the mission to promote social change and social development in China to enhance the quality of life of the Chinese people.

References

Boyer, E.L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: priorities of the professoriate. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Greenwood, D.J. (1991). Collective reflective practice through participatory action research: a case study from the fagor cooperatives of mondragon. In D.A. Schön (ed.), The reflective turn: case studies in and on educational practice (pp. 84–108). NY: Teachers College Press.

Gronski, R. & Pigg, K. (2000). University and community collaboration. The American Behavioral Scientist, 43(5): 781–92.

Hall, A. & Midgley, J. (2004). Social policy for development. London: SAGE Publications.

Harkavy, I. & Puckett, J.L. (1994). Lessons from Hull House for the contemporary urban university. Social Science Review, 68(3): 299–321.

Ku, H.B., Yeung, S.C. & Sung, P. (2005). Searching for a capacity-building model in social work education. Social Work Education, 24(2): 213–33.

Lanzara, G.F. (1991). Shifting stories: learning from a reflective experiment in a design process. In D.A. Schön (ed.), The reflective turn: case studies in and on educational practice (pp. 285–320). NY: Teachers College Press.

Lei, J.Z. & Shui, Z.Z. (1991). The thirty years of the social work programme of Yenjing University. In N. Chow et.al. (eds), Status quo, challenge and prospect: collected works of the seminar of the Asian-Pacific region social work education (pp. 10–16). Beijing: Peking University Press.

Leung, J.C.B. & Nann, R. (1995). Authority and benevolence: social welfare in China. Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

Marullo, S. & Edwards, B. (2000). From charity to justice. The American Behavioral Scientist, 43(5): 895–912.

Mayfield, L., Hellwig, M. & Banks, B. (1999). The Chicago response to urban problems: building university–community collaborations. The American Behavioral Scientist, 42(5): 863–75.

McCartt Hess, P. & Mullen, E.J. (eds) (1995). Practitioner–researcher partnerships: building knowledge from, in, and for practice. Washington, DC: NASW Press.

Midgley, J. & Livermore, M. (1997). The developmental perspective in social work: educational implications for a new century. Journal of Social Work Education, 33(3): 573–85.

Oja, S.N. & Smulyan, L. (1989). Collaborative action research: a developmental approach. NY: Falmer Press.

Pace, L.A. & Argona, D.R. (1991). Participatory action research: a view from Xerox. In W.F. Whyte (ed.), Participatory action research (pp. 56–69). London: SAGE Publications.

Preston, P.W. & Haacke, J. (2003). Change in contemporary China. In P.W. Preston & J. Haacke (eds), Contemporary China: the dynamics of change at the start of the new millennium. London: Routledge Curzon.

Sarri, R.C. & Sarri, C.M. (l992). Organizational and community change through participatory action research. In D. Bargal & H. Schmid (eds), Organisation change and development in human service organisations, administration in social work (pp. 99–122). NY: Haworth Press.

Schön, D.A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schön, D.A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. NY: Basic Books.

Sung-Chan, P. L. (2000). Learning from an action experiment: putting Schön’s reciprocal-reflection theory into practice. Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 7(2–3): 17–30.

Wang, S.B. (2003). The social responsibility of social work in a changing society. In S. Wang et al. (eds), China's social work in transition: essays from 2001 annual symposium of China Association for Social Work Education (pp. 3–12). Shanghai: East China University of Science and Technology Press.

Weinberg, A.S. (1999). The university and the hamlets: revitalising low-income communities through university outreach and community visioning exercises. The American Behavioral Scientist, 42(5): 800–13.

Whyte, W.F. (ed.) (1991). Participatory action research. London: SAGE Publications.

Xiong, Y.G. (1999). Problems and challenges confronting the development of social work education in the 21st century. In Journal of China Youth College for Political Sciences, special issue, Reflections, Choices and Development: Special Issue on Social Work Education (pp. 32–37).

Yuen-Tsang, W.K.A. (1996). Social work education in China: constraints, opportunities, and challenges. In J. Cheng & T.W. Lo (eds), Social welfare development in China: constraints and challenges (pp. 85–100). Chicago: Imprint Publications.

Yuen-Tsang, W.K.A. & Tsien, T. (2004). Universities and civic responsibility: actualising the university–community partnership model through the anti-SARS project in Hong Kong. The Asian and Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 14(1): 19–32.

Yuen-Tsang, W.K.A & Sung-Chan, P.P.L. (2002). Capacity building through networking: integrating professional knowledge with indigenous practice. In N.T. Tan & I. Dodds (eds), Social Work around the world, vol 2, Agenda for global social work in the 21st century (pp. 111–22). Berne: IFSW Press.