15

Social work education in the United Kingdom

Social work education in the United Kingdom

This chapter examines key areas in social work education theory, practice, and research in the UK, including the main methods used and the client groups with whom social workers engage.

The chapter sketches the origins and development of social work education and identifies key features currently framing social work education (SWE). The latter include factors associated with higher education systems and policies as well as those specific to social work in its organisational frameworks and as a profession. The staffing of social work programs and the role of research in relation to theory and practice development are discussed. A major section presents the predominant practice models, methods, theories and perspectives and their associated histories and epistemological challenges. Mention is made of contributing disciplines (e.g. sociology and law) and the key teaching and learning strategies utilised, including in relation to issues of cultural relativism and understanding, and international influences. Conclusions are drawn regarding the health of the discipline in the UK.

Social work as a recognised activity dates back to the late 19th century in the UK and social work education (SWE) has had a long and somewhat chequered history. One purpose of this chapter is to describe the context within which SWE has developed, with an emphasis on current contextual influences. More importantly, the chapter aims to analyse the contemporary features of social work, both as a discipline within higher education, and as a form of professional education with a primary task of preparing students for a variety of roles in ‘real world’ social work. The main organisational features of SWE are described, as are the regulatory frameworks and professional goals and ethics influencing the design and delivery of programs at a range of academic and professional ‘levels’. It should be mentioned here that different factors have impacted on social work in Scotland and Northern Ireland in the relatively recent past and some of these have had implications for SWE. This chapter therefore relates specifically to England, although generic programs are the norm throughout the UK and a first degree (BA or BSc) in social work is currently the nationally accepted qualification.

A wide range of ‘external factors’ impact on social work and therefore on SWE. These include political direction and economic factors affecting the funding of social work agencies and education programs. In addition, the needs of service users; expectations of other professional groups and the wider public; and media pressures also influence professional and educational developments. Internally, debates reflect ambivalence about the purpose of SWE and the form it should take, raising questions about ‘who teaches social work’ as well as content and pedagogical approaches. Similarly, there are varied understandings of the role of research and therefore its form and focus. A major section presents the predominant practice models, methods, theories and perspectives and their associated histories and epistemological challenges. Mention is also made of contributing disciplines (e.g. sociology and law) and the key teaching and learning strategies utilised, including in relation to issues of cultural relativism and understanding; anti-oppressive strategies; and international influences.

Significant features of SWE in the UK have been expectations about the roles that social work employers (initially) and then service users would play in the structure and delivery of SWE, creating distinctive requirements on social work for close working relationships between university staff and social service agencies and those with whom they work. The major factors impacting on social work practice learning are identified and consideration is given as to how well students are prepared for practice. In addition, the special needs of newly qualified social workers and staff moving into specialist areas of work have been recognised leading to the establishment of various forms of post-qualifying and postgraduate education and training.

Following a section summarising the major trends in the development of SWE and its organisational context, this chapter focuses on the content of programs and their relationship to regulatory frameworks and ‘readiness to practice’ drivers. A further section discusses staffing and research issues as well as mentioning some new initiatives which may impact on social work in higher education. The chapter concludes with a consideration of the current state of SWE in England.

British social work education: history and organisational context

The first training opportunities for ‘social workers’ were afforded by a voluntary agency, the Charity Organisation Society (COS), in the late 19th century, and, by the early years of the 20th century, social work training had gained a place in various universities, notably in London, Birmingham, Liverpool and Glasgow. These were all cities with high rates of poverty with associated problems of squalid living conditions and ill health; and SWE included community work, allied to the earlier establishment of ‘settlements’ (forerunners of community centres) in the poorest parts of many cities. Some of the notable figures in the development of social work had their earliest experiences in the Settlement houses and subsequently made significant contributions to social work organisation and policy developments as well as education. One such person was Eileen Younghusband who, later in the 20th century, also contributed to international developments in SWE (Lyons 2008).

One outcome of World War 1 (1914–18) was an increase in interest in psychiatric conditions and treatments, and by the 1930s there had been significant growth in psychiatric (including psychoanalytical) services (as well as the beginnings of psychology as a discipline). These changes were reflected in SWE in the ‘psychiatric deluge’ (Payne 2005). On many courses this meant less concern about policies and interventions appropriate to the social conditions of poor people, relative to a greater emphasis on intra- and inter-personal relationships. This emphasis shifted again in the post-World War 2 period (1939–45) when a raft of welfare legislation laid the basis for the development of services and provisions broadly termed ‘the welfare state’. One result of this was that sociologists and social policy analysts began to examine the outcomes of policies and programs aimed at general improvements in living standards and individual life chances, only to find, by the late 1960s, that old social divisions had resurfaced and new forms of social inequality had taken hold. Research had resulted in ‘the rediscovery of poverty’, a condition thought by many to have been eradicated, though it was now framed as a relative rather than absolute condition (Townsend 1979). As in previous eras, SWE was expected to mirror the shifts in political concerns and policy direction, although at this stage social work itself was being carried out in a range of agencies relating to different ‘client groups’ and courses tended to reflect the fragmentation of the field and provide ‘training’ in specialised fields.

In organisational terms, the earliest social work courses were established at postgraduate level in universities. These were usually allied to ‘social studies’ awards, constituting a continuous thread (with modifications) through to current forms of social work education and awards at master’s level. The possibility of being awarded a professional qualification at two different academic levels has led to anomalies and complications in most recent organisational changes in the structure of SWE (see later). SWE has often recruited mature students but, apart from occasional efforts to adapt course length and attendance requirements to recognise this and the gendered nature of social work, gaining a professional qualification normally required attending a full-time course (at whatever academic level) until late in the 20th century.

From the 1970s, following the expansion in higher education through the establishment of a large number of polytechnics (similar to German Fachhochschulen), the majority of students qualified at Diploma in Social Work (DipSW) level, awarded by the academic institution after two years of study at undergraduate level, with the Certificate of Qualification in Social Work (CQSW) being awarded concurrently by the professional regulatory body, the Central Council for Education and Training in Social Work (CCETSW 1979–2001). Some universities continued to offer postgraduate courses to people who had gained undergraduate degrees in ‘relevant subjects’, affording some a postgraduate award in conjunction with a basic (rather than advanced) professional qualification. Organisational changes which took place in 1970, notably the establishment of unified Social Service Departments offering services across a wide range of client/user groups (with the exception of School Welfare and Probation Services), also resulted in shifts in the focus and content of social work courses which were now primarily ‘generic’. A national division of responsibilities for youth and community services and for social services, between the Departments of Education and of Health respectively (and reflected at local authority and institutional levels), supported moves to establish separate courses and awards for youth and community workers. By the early 1980s the few remaining joint awards were ended with the establishment of separate bodies to regulate such courses and approve awards; and units or modules on CQSW courses equipping students for community work (and also often for group work) were largely discontinued. However, changes also reflected a moral panic about child abuse – most specifically, public concern about the deaths of children at the hands of their parents or primary care givers, particularly if these families were already under the supervision of social workers (Parton et al., 1997). Thus, there was an increased emphasis in many courses on work with individuals and families, including teaching and assignments aimed at developing skills in child observation and communicating with children.

Apart from a trend towards skills training rather than theoretical developments in social work education in the latter decades of the 20th century, there were also other shifts in course content. The first was related to developing racism awareness, equal opportunities and, eventually, anti-oppressive strategies, while the second laid an increased emphasis on teaching about the law. Anti-racism teaching and learning was required by CCETSW from the 1980s and inputs to courses were often first provided as short courses on anti-racism, add-ons to the main structure and content of programs. Subsequently, they were usually incorporated into mainstream teaching and extended into units or modules to address other forms of inequality and discrimination, e.g. based on gender, sexuality or disability.

In relation to the legal content of social work programs, a series of studies in the 1990s demonstrated that about 80% of students leaving social work education programs gained employment in local authority Social Service Departments, a statutory agency where legal requirements predominated in terms of the provision of services and the style of practice. Preventive work increasingly became a thing of the past or the responsibility of other agencies (including in the voluntary sector) and occupational groups. Many social workers complained that, in an increasingly managerialist environment, there was decreasing scope for relationship-based work and interventions beyond the assessment stage. It seemed as if what social work educators aimed to equip social workers to do was out of step with what they might be expected to do in practice.

The passing of the National Health Service and Community Care Act (1990) had signalled national moves to a mixed economy of care and increased emphasis on care management roles. This led in turn to the establishment of a parallel, employment-based route to a different qualification, Certificate in Social Services (CSS), which was offered in conjunction with some further and higher education institutions for about a decade. In addition, the government decided that changes should be made in the work of the Probation Service requiring the introduction of different training for Probation Officers and its complete separation from SWE. Thus, by the end of the 20th century, a more diverse range of awards existed in what might be called the ‘social professions’ and an increase in the modes of delivery was becoming apparent.

By the 21st century the government concluded that neither SWE nor its regulatory body were ‘fit for purpose’: approval was finally given for the replacement of the two year diploma/CQSW award by a three year degree, with provision for postgraduate conversion courses to continue as two-year masters’ programs. These programs were to be regulated by a new agency, the General Social Care Council (GSCC, one each for England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales 2001–12): this agency would not make a separate award but would require successful students to register in order to take up any post labelled as social work. Thus, social work finally achieved what many (including educators) had long argued for – provision of three-year educational programs and qualification at degree level (in line with many other countries in Europe and around the world) and restriction of use of the title social worker to those holding a professional qualification. However, the story does not end there since, by 2013, there have been further organisational changes in higher education and externally; several social work courses or departments have closed since the 1990s; SWE as a whole is in 2013 once again under review; the agency responsible for regulation has changed; and a new form of fast track training is being initiated, as we discuss later.

Course content, regulatory frameworks and readiness for practice

As indicated above, and in contrast to SWE in many other European countries, the content of British SWE courses has for some time been prescribed by regulations set out by government and its agencies. In 2010 the Social Work Reform Board was established as a government response to a child’s death that raised severe doubts about the competence of social workers in protecting children already known to be at risk of abuse. Its purpose was to set out an agenda for social work and social work qualifying education and recommendations were made in 2012. Meanwhile, in 2011, a new body was established by government, the College of Social Work (with the aim of raising standards in social work and SWE. (It is intended that this should become a self-funding body, independent of government). The college has no regulatory powers, but its Professional Capabilities Framework (PCF, see later) and its standards are taken into account by the current regulatory body, the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) when validating programs (see later).

One stream of the Reform Board’s work (of which one of the authors was part) focused on the ‘Calibre of Entrants’. Traditionally social work courses have accepted some mature students with ‘life experience’ who may, however, lack good academic qualifications. Concerns were raised about how to assess at entry stage empathy for and understanding of service user issues and the potential to learn about and carry out the complex tasks of social workers, while also raising the academic standards on courses. The result was that academic entry requirements have been made more stringent, but concerns persist about both the suitability of students and the direction in which SWE is being pushed, i.e. to a more elite form of training (see also later) and away from a previous commitment to open access, providing opportunities to a wide range of applicants. The responsibility for driving this and other aspects of the agenda passed to the College of Social Work in England from 2012.

At the same time as the drive to raise academic standards, a key debate continues to be whether social work theory is sufficiently related to practice and, indeed, how much theory is needed to prepare students to become qualified social workers. The government’s influence on the content and processes of SWE is now exercised through the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) which took over most of the responsibilities of the GSCC in 2012. As mentioned above, courses have increasingly phased out approaches such as casework (based on psychodynamic ideas) and community work, since they do not fit with government priorities, nor with the requirements of most employers. As with the GSCC before it, the HCPC stipulates that employers should have a substantial say in the development and ongoing review of courses.

The HCPC Standards of Proficiency for social workers in England

Approaches and focus: social workers must be able to

- understand the need to promote the best interests of service users and carers at all times

- understand the need to protect, safeguard and promote the wellbeing of children, young people and vulnerable adults

- understand the need to address practices which present a risk to or from service users and carers, or others

- be able to use practice to challenge and address the impact of discrimination, disadvantage and oppression

- be able to support service users’ and carers’ rights to control their lives and make informed choices about the services they receive.

Teaching and learning methods used to enable students to meet these requirements include lectures; seminars; small group and individual tutorials; problem-based learning; case studies and group exercises; visits to students on practice placements (‘three-way meetings’ between the student, practice educator and tutor); and, increasingly, online learning with the use of exercises, quizzes, online group discussions, etc.

One of the recommendations of the Social Work Reform Board was that there should be more emphasis on skills development, so, as from 2013, courses must include 30 days of skills training (assessed) before students can start practice placements. Considerable emphasis is placed on assessed practice learning in placements provided by social work agencies which are supported financially by the government’s Department of Health (agencies get a daily fee for taking a student). Students usually undertake two or three assessed placements in different settings and these must total 200 days. A professional award cannot be made to anyone who fails a placement.

Practice learning therefore has a high priority in the assessment of students and great emphasis is placed by universities and the HCPC on the development and support of both placements and practice educators so that these are ‘fit for purpose’. Panels have been established comprising university and agency staff and often also service users and/or carers to assess reports from the practice educators, who may be challenged to provide further evidence as the basis for decisions about passing or failing a placement. Prior to placements, practice educators are required to have undertaken training (provided by the universities) for their role. Guidance is issued for students and practice educators on the processes and regulations governing placements and these are monitored and supported through three-way meetings (usually two or three per placement) as well as workshops for the practice educators.

The main areas to be addressed in course content include:

- sociological ideas

- social policy

- psychology (e.g. human growth and development, mental health and learning disabilities)

- anti-oppressive practice

- law

- ethics teaching – this is variable, and often subsumed into the discussion of professional behaviour and regulation.

Key areas of policy and practice currently influencing SWE are individualisation; personalisation and individualised packages of care (with a new emphasis on ‘re-enablement’); adult and child safeguarding; inspection and regulation; legal aspects; interagency and inter-professional working (Wilson et al. 2011; Littlechild & Smith 2013), and risk assessment and management (Littlechild 2008; Littlechild & Hawley 2010).

The HCPC also takes into account the provisions of the College of Social Work; the central government’s Department of Health; and the education sector’s Quality Assurance Agency (QAA). The last body sets the academic descriptors of program levels for the BA/BSc in Social Work as well as for the master’s degree which enables students with a relevant first degree to gain a professional qualification after two years. The HCPC validates social work qualifying courses which satisfy its Standards for Education and Training; its Standards of Proficiency (as described above); and also the Professional Capabilities Framework (PCF) issued by the College of Social Work. On qualifying, people wishing to work in social work designated posts must register with the HCPC, which also has powers to strike off social workers who are judged to have failed to meet its Standards of Proficiency and its ethical statement.

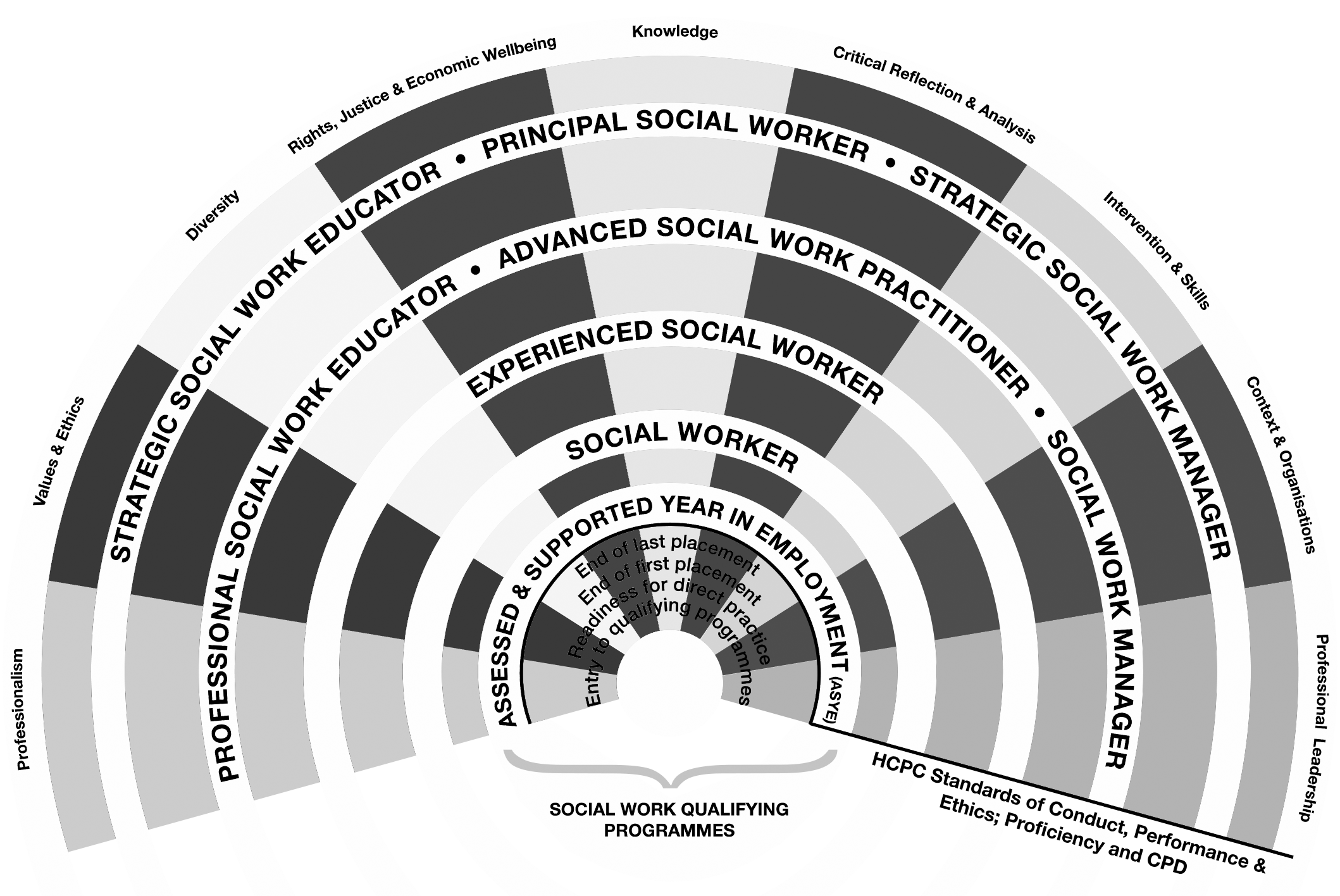

With regard to the Professional Capabilities Framework (PCF), this was developed by the Social Work Reform Board, but is now ‘owned’ by the College of Social Work. It was framed with the intention of moving SWE away from previous requirements regarding competences to a more rounded focus on capability. This reflects a move from a mechanistic tick box approach to a more holistic approach (The College of Social Work 2012b). The PCF sets out nine domains of social work, and how those entering the profession and then progressing through it attain those domains. Whilst not technically regulatory, this framework is being used extensively by the HCPC, social work agencies and qualifying social work courses (Figure 15.1).

Figure 15.1 Professional capabilities framework for social workers (The College of Social Work 2012a).

Social work courses have to demonstrate to the HCPC that they are meeting the HCPC requirements for a qualifying course by having to map their learning outcomes to the elements of the PCF, and the HCPC’s own Standards of Proficiency. For example, students should be enabled to:

Demonstrate a critical understanding of the application to social work of research, theory and knowledge from sociology, social policy, psychology and health. (Knowledge 5.1)

Demonstrate a critical knowledge of the range of theories and models for social work intervention with individuals, families, groups and communities, and the methods derived from them. (Knowledge 5.8)

Understand the inter-agency, multi-disciplinary and inter-professional dimensions to practice and demonstrate effective partnership working. (Contexts and Organisations 8.7)

In order for universities to be approved to run social work qualifying programs, they have to ensure that their students are able to ‘meet all the standards of proficiency to register with us and meet the standards relevant to your scope of practice to stay registered with us’.

The following selection of a few key points from HCPC Standards for validating social work courses gives a flavour of the emphasis placed on different areas by them:

4.7 The delivery of the program must encourage evidence-based practice.

5.1 Practice placements must be integral to the program.

6.1 The assessment strategy and design must ensure that the student who successfully completes the program has met the standards of proficiency for their part of the Register.

The main aim of social work qualifying education from the HCPC’s perspective is to prepare students at the point of qualification to be able to meet its Standards of Proficiency (see HCPC Standards for Education and Training 2012).

As a result of the policies and laws set out above, the new roles and skills for social workers have become the planning of care packages and services; resource allocation; assessment; and care management functions. Setting and reviewing performance indicators and outcomes based on the achievement of measurable objectives within predetermined procedures and resource allocation decisions based on government guidance and regulation have assumed greater importance than direct work with service users, with inevitable implications for the content of courses.

Earlier theories which emphasised social beings as members of social systems and the relationship between social problems and social and political systems have been discarded in the face of a general climate which places responsibility on individuals for their own behaviour and wellbeing (including income or lack of it). The individualisation of social problems has led to the teaching of theories and methods that are now focused on work with individuals and families, and formal organisations, at the expense of therapeutic, community and emancipatory approaches. The key elements of methods and models are individualised approaches, such as ‘process’ casework, often now focused on assessments for services, and referring on to other agencies, i.e. care management. Methods taught tend to be short term and time limited approaches; for example, task-centred work; crisis intervention; cognitive behavioural approaches; and targeted programs. Family therapy was popular in social work practice some 15 or so years ago, but the focus has moved to training-based work, such as in parenting programs. Solution-focused models based on strengths rather than deficits are examined in some courses. In summary, there has been a general move away from group and community work (seen by some as more likely to raise questions about and pose challenges to government policies) and from therapeutic work with individuals and families, in favour of more conservative and functional approaches. However, some have identified a renewed interest in direct work with children and also in relationship-based work (e.g. Wilson et al. 2011).

Staffing, research and new developments

Alongside the external pressures on SWE to move in particular directions, there have also been issues of visibility and identity within higher education, with implications for the staffing and research roles of social work educators themselves. Is it an academic discipline or a form of professional education (or even training)? Such debates are partly related to the alliances and organisational bases of social work courses – which have rarely been located in departments labelled Social Work. In the 1990s more than 50% of respondents to a survey described their alliances as primarily with staff in academic subject areas while the remainder were more allied with professional educators (Lyons 1999). Developments over the past decade or so, including the need for universities to cut their costs, suggest that possibly more programs are now located in professional departments and students may increasingly be taught some of their modules alongside other students in related fields for example, health or youth and community work.

With regard to staffing, for many years practice experience tended to be prized over academic qualifications in the appointment of staff, which, together with the responsibilities associated with the social work educator role (e.g. including placement visits), perpetuated a state in which theory and practice were divided; and the creation of new knowledge through research was not seen as the responsibility of social work educators themselves. Around 2000, a shift in this situation occurred, partly as a result of a series of seminars (initiated by social work academics with funding from the Economic and Social Research Council, ESRC) aimed at improving the theoretical base of social work and the research activities of staff. Further impetus was given by a national Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) in which social work educators from a minority of universities were amongst those whose work was included, resulting in specific funding for further research (to some institutions) and also the award of other funding for capacity building for research in social work. One outcome of this raised profile was what some hoped, and others feared, an increased academisation of social work education, with increased recognition given to the academic qualifications of newly appointed staff and increased expectations regarding their research activities.

In a demographic review of the UK social sciences, Mills et al. (2006) identified social work education as having high retirement and appointment rates and that 47% of the staff were aged 50 and over. In a subsequent research project into the implications of generational change in the social work academic workforce, Lyons and Maglajlic (2010) received 41 responses to a survey of 76 out of 100 programs in the UK (54% response rate, covering 479 staff). Data indicated that 10% of staff had retired in the past three years, that one in six were planning to retire in the next five years and that 60% of posts created by retirement were filled by first-time academics. Of the newly appointed staff, half came direct from social work practice, with 20% coming from research posts and the remainder mainly from other posts in social services (e.g. managers, training officers); 20% of the new entrants already held a PhD while 40% were undertaking – or intending to undertake – doctoral research. The findings also showed an increase in the proportion of women staff (already high) and a decrease in the numbers of staff from black and ethnic minorities (already low). A related analysis of 44 advertisements for social work posts identified that only three-quarters stated that a social work qualification was essential and this, with other anecdotal evidence, suggests that social work posts in some universities are open to colleagues from neighbouring disciplines. This is turn raises concerns about the implications for the development of professional identity in students at a time when social work in the field has been undergoing significant changes and a narrowing of its remit.

The situation regarding research has also changed over the past decade with the expectations of, and opportunities for, staff partly mirroring a continuing split between the old universities (established prior to 1992) and the new ones (based on the granting of university status to polytechnics in that year). Despite some notable exceptions, there has continued to be an emphasis on research in the old university sector while many new universities see themselves as primarily teaching institutions. In parallel, the competition for research funding from the main funding body (ESRC) and various charities has increased in anticipation of further rounds of national assessment exercises (e.g. the REF due in 2014), with the promise of further funding for the winners. This has led to a clearer concentration of a minority of social work staff in research centres and/or engaged in multi-disciplinary research teams (mainly in the old university sector), with staff in the new universities, whatever their inclinations, finding it increasingly hard to gain access to research funding and/or to undertake individual (unfunded) research programs (including for doctoral purposes). Sabbaticals, previously already rare in the new university sector, are now virtually unheard of and current anecdotal evidence of difficulties recruiting to social work posts (at various levels, up to and including professors) further reduces the time available for staff to undertake research.

The current staffing difficulties perhaps partly relate to the lack of a strong research culture in the profession as a whole and the lack of value placed on research in the wider political and policy context. However, a recent emphasis on evidence-based practice has pushed social work educators and those researching social work to reconsider the design of research projects (not least if they wish to win funding). The preferred mode of much social work research in the past has been in the qualitative paradigm, including the development of evaluative studies and approaches involving service users (e.g. Shaw 2012), but more emphasis has been given recently to adopting positivistic designs and quantitative methods (e.g. randomised control trials). This may put social work educators at a further disadvantage since few have had the necessary training in research skills and most do not include such teaching in their own qualifying and post-qualifying programs. However, some see this challenge as an indication of the maturing of social work into a proper discipline, gradually building the capacity to create its own knowledge base, for use in social work education and the wider professional field.

However, the regulatory developments described above suggest less valuing of research and staff development opportunities. For instance, there is now no regulatory framework for post qualifying continuing professional development (as previously existed in the provisions of the GSCC). Every three years, social workers need to demonstrate to the HCPC how they have kept up to date with their continuing professional development (CPD) but there are no specific links required in relation to research or academic awards. In addition, CPD is no longer one of the items included in government targets for local authority employers to meet and, given cuts in spending, there has been a decrease in support for CPD programs (including those provided by universities). Against this, in line with the government objective of raising the status and standards of the social work profession, two new training initiatives have recently been established, Step-up to Social Work (www.education.gov.uk/b00200996/step-up) and Frontline (www.education.gov.uk/a00225213/frontline). These are both intensive employer-led programs at master’s level, that set out to attract academically high-achieving students, who may, if they continue in the profession, be more inclined towards research.

Finally, another recent external change which may impact adversely on university-based social work education is the reduction in the amount of money to be paid in bursaries to students gaining places on social work undergraduate and postgraduate degrees. These awards were introduced in the early 2000s following a fall in the number of recruits to SWE and calls for parity with other shortage occupations (including nursing and teaching). Bursaries have been effective in raising recruitment levels but it seems as if funding of the new initiatives mentioned above has now taken priority over maintaining traditional recruitment patterns.

Conclusions

SWE in England illustrates a number of points which may or may not resonate with readers outside the UK. A significant one is the extent to which it reflects national characteristics, culture and concerns in a particular time and place. Over a history spanning more than a century, social work has become a unified and apparently stronger profession, but, as with some other professions, it has also become increasingly subject to government expectations and requirements. These in turn are also reflected in other aspects of welfare changes which require individuals to take increasing responsibility for themselves, their relatives and neighbours (so-called ‘care in the community’), only drawing on (or being referred for) public funding and/or social work services when a crisis is reached and/or the behaviour of individuals or families falls outside the tolerated norms. A culture of surveillance and regulation extends to the professionals who work with people in distress and social workers have found themselves increasingly subject to bureaucratic procedures and restrictions.

Similar drivers have been evident in government interventions and regulation of SWE which now shows some contradictory trends. On the one hand, there is an increased recognition of the need for developments in theory and research as these relate to practice, while on the other hand, students are required to spend more time on skills training and in practice placements and the money available to fund practice-related research is scarce. There is an increased recognition of the need for interprofessional cooperation, which theoretically could be achieved through increases in joint education, but the economies of scale required of universities usually mean delivery of generic courses to large groups without the opportunity to explore what the term might mean for different occupational groups in practice. There is also a recognition in some quarters that we live in an interconnected world where economics and migration are defining features of many societies – yet these topics are rarely addressed in the English SWE system due to crowded timetables and prescriptive guidance as to content relevant to a narrow form of social work – and perhaps the assumption that there is little to be gained from comparative or international study. Finally, the values of social work are compromised in a situation where policies aimed at extending opportunities to people who might otherwise not qualify for higher education – but who might make very good social workers – are overtaken by policies which emphasise academic qualities.

In all of this, the costs of SWE in England, the pressures on staff which prevent full engagement in research activities, and the various points of conflict which arise between institutions and professional bodies (e.g. around assessment) undoubtedly place SWE in a vulnerable position within the university sector – as demonstrated by the periodic loss of courses when universities seek to cut their costs and/or raise their research ratings. In parallel, the pressures and initiatives to increase the power of employers in relation to social work training and qualification suggest a future in which occupational standards prevail over critical thinking and professional practice and values. While we do not think that social work as a profession has been eroded to a point of no return in England nor that SWE is about to cease in universities, the situation with regards to future developments is, to say the least, uncertain.

References

Littlechild, B. (2008). Child protection social work: risks of fears and fears of risks – impossible tasks from impossible goals? Social Policy & Administration, 47(6): 662–75.

Littlechild, B. & Hawley, C. (2010). Risk assessments for mental health service users: ethical, valid and reliable? Journal of Social Work, 10(2): 211–29.

Littlechild, B. & Smith, R. (eds) (2013). A handbook for interprofessional practice in the human services: learning to work together. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Lyons, K. & Magajlic, R. (2010). Professional identity: generational change in social work academic workforce. Paper presented at Global Conference, Hong Kong, 13 June.

Lyons, K. (2008). Eileen Younghusband, 1961–1968. In F. Seibel (ed.), Global leaders for social work education: the IASSW presidents 1928–2008. Boskovice, Czech Republic: Albert.

Lyons, K. (1999). Social work in higher education: demise or development. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

Mills, D., Jepson, A., Coxon, T., Easterby-Smith, M., Hawkins, P. & Spencer, J. (2006). Demographic review of the UK social sciences. Swindon: Economic and Social Research Council.

Parton, N., Thorpe, D. & Wattam, C. (1997). Child Protection, risk and the moral order. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Payne, M. (2005). The origins of social work: continuity and change. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Shaw, I. (2012). Practice and research. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

The College of Social Work (2012a). Reform resources. Retrieved on 11 June 2014 from www.tcsw.org.uk/uploadedFiles/TheCollege/_CollegeLibrary/Reform_resources/PCFfancolour.pdf.

The College of Social Work (2012b). Reforming social work qualifying education: the social work degree. London: The College of Social Work.

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom. London: Allen Lane and Penguin Books.

Wilson, K., Ruch, G., Lymbery, M. & Cooper, A. (eds) (2011). Social work: an introduction to contemporary practice (2nd edn). London: Pearson Education.