12

The current status and future challenges of social work education in South Korea

Social work education in South Korea

The growth in the number of social workers in the past six decades has been accompanied by a dramatic shift in social work education in South Korea. However, the quality of social work education was not fully considered. Thus, this chapter sets out the history and current status of social work education in South Korea, and discusses the contemporary challenges and the future of social work education in South Korea. First, current status and issues regarding academic programs, curricula, field education, and the social work licensure system are addressed. The challenges for social work education in South Korea are then discussed. The areas of accreditation reviews to verify each program, course development beyond the licensure examination, the improvement in the quality of field education, and efforts to improve social work competencies are all then examined.

A social work education program was first established at Ewha Womans University in the middle of the 20th century with a limited number of classes in casework (Hong, Kim, Lee & Ha 2011). Since then, social work and welfare in South Korea has grown rapidly. According to the Korean social work statistical yearbook (Korea Association of Social Workers 2012), there were 556 graduate and 482 undergraduate programs in social work and social welfare, and 505 vocational schools offered a specialised program in social work in 2010. Recently, web-based social work education as well as continuing education programs have been expanding. Approximately 57 web-based ‘cyber colleges’ and 66 continuing education centres offer social work education. Nationally, there is a significant number of general social service agencies, as well as social welfare agencies for specific populations (i.e. people with disabilities, the elderly); these agencies have a significant role in a variety of settings within the social work educational field. These programs produced 492 social work educators (faculty members), and a total of 110,082 licensed social workers who hold a level 1 social work certification in 2013. Of these licensed social workers, 751 mental health social workers, 666 medical social workers, and some school social workers are working toward obtaining additional certificates in specific settings.

In accordance with the current numbers of academic programs, field education settings, educators, and licensed social workers, there are numerous issues and challenges for social work education in South Korea. These challenges may be a consequence of social work scholars’ concerns about the rising number of social work education programs and the concurrent changes in social welfare policy and social problems in South Korea. Koreans in the social work profession have made short- and long-term commitments to manage the diverse social problems in Korea; thus, the social work profession can be said to be in a development phase. At the same time, social work education is expected to expand continuously to address diverse learning needs and to provide high-quality educational opportunities. The recognition of recent changes and challenges in social work education as well as the attempts to improve social work education in South Korea may help to establish the legitimacy of the field in terms of official educational standards. The purpose of this chapter is to describe the history and current status of social work education in South Korea and to discuss the contemporary challenges and the future of its social work education. Issues related to academic programs, curricula, field education, and the social work licensure system will be addressed.

The history of Korean social work education

The first social work education program began at the Ewha Womans University in 1947. Since then, several universities in South Korea (e.g. Kangnam University, Seoul National University) have established departments of social work. Social work education in South Korea has been modified to respond to education reforms, but the underlying values and functions of social work undergo gradual changes. Generally, Korean social work education can be categorised into three stages: (1) the Department of Social Work era (1950–1960); (2) the Department of Social Welfare era (1970–1980); and (3) the Department of Family, Society, and Welfare era (1990–current).

The Department of Social Work era

An important trait of Korean social work education is that the department of social work was created before social welfare policies and standards of clinical practice were established. This characteristic differentiates South Korea from other nations, such as the United States or Japan, where the principles of social work practice and social work education were established before social work education was implemented. Lee and Nam (2005) argue that Koreans simply imported the social work education system of the United States, as if they were transplanting an organ, without considering how the clinical experiences, experiments and research, philosophies and social movements would apply in a South Korean context. However, the system was also imported for a practical reason: during the first stage of social work education, many Korean educators obtained doctoral degrees in the United States and were then hired at universities in South Korea. Their employment at universities stimulated the development of a new social work education system that was based on the missions of schools of social work in the United States. Thus, courses on the traditional social work practices, ethics and values in the United States have been included in the social work curriculum. For example, casework, group work, community-based organisation, human rights and social justice were required topics in social work education during this stage. However, there were limitations on the ability to practice social work skills and values in the South Korean cultural context: social services in the public and private sectors were not linked to social work education, and people in social work service agencies did not fully understand the social work service delivery systems or social work education.

The Department of Social Welfare era

In the 1970s, South Korea made significant efforts to achieve economic growth, and the South Korean Government prioritised the economic development of poor communities. In response, social work students focused on volunteer activities to promote development in poor communities, which is one aspect of social work practice. While social work education programs in the United States focused on integrative social work methods in the 1970s, the core content in social work education programs in South Korea continued to include traditional social work practices, such as individual, group, and community-based organisational practices. This trend continued until the middle of the 1990s, and many Korean educators learned through trial and error (Lee & Jung 2012). When politics and values in South Korea gradually shifted toward supporting the welfare society, several social work educators began discussing their educational identities. During this stage, the number of social work programs in South Korea increased rapidly, and social work education in the United States emphasised the interaction between micro and macro social work practices. In colleges and universities in South Korea, departments of social work became departments of social ‘welfare’.

The Department of Family, Society, and Welfare: the globalisation era

As the open education movement grows in South Korea, new education systems have emerged, including the school system (called ‘hack-boo-jae’ in Korean), the double-major system, and minimum-grade-for-credit system. During this stage, the number of private universities has increased significantly as higher education has been popularised in South Korea. While social work education in the United States has been implemented at the master’s level, social work education in South Korea has primarily focused on undergraduate programs that are based on the school system and the minimum-grade-for-credit system. Consequently, one challenge has been to effectively provide social work knowledge, skills, and abilities that balance micro and macro practical approaches, theory and practice, and science and skills with an education that includes social work values, philosophies and ethics. This situation has caused confusion regarding the identities and professionalism of social work and welfare academics and education programs; thus, diverse changes have been made in social work policies and the new licensure system which embrace status-related and organisational tactics. That is, according to the Social Welfare Service Act, the social work licensing examination has been administered by the government since 2003. With the diverse changes in social work education, the number of programs has increased to more than 550 graduate and 480 undergraduate programs in social work and social welfare. These programs have produced more than 70,000 social workers who work in diverse areas of social work practice, including the micro, mezzo, and macro sectors.

The current status of social work education in South Korea

Academic programs

There are several types of social work education programs in South Korea. At the bachelor’s level, four-year and two-year colleges provide social work education. At the master’s level, professional graduate programs, general graduate programs, and special graduate programs offer social work and welfare courses for professional or academic social workers. As another vehicle of social work education, web-based educational institutes, which are known as ‘cyber colleges’, deliver academic programs completely online. Continuing education programs offer a broad spectrum of post-secondary learning activities, and programs provide social work education to non-traditional students who require non-degree career training, workforce training, or formal personal enrichment courses. Because each program has a different mission and different goals and values, the quality of the academic courses, field practices, educators and students varies. For example, social work programs that are provided by two-year colleges, cyber colleges and continuing education institutions are designed to produce personnel who can work in general social service agencies. These programs tend to provide social work education so that students can meet the minimum academic requirements to obtain a level 2 social work certification. Although the duties performed by social workers holding a level 2 social work certification are similar to those of social workers holding a level 1 social work certification (e.g. counselling, referral, program development, policy proposals, etc.), social workers holding a level 2 social work certification do not have opportunities such as higher-level promotions, higher salaries, management/supervision, and establishment of social work agencies. Thus, because the missions and values of social work education programs differ, the quality of social work education depends on the educational setting.

Table 12.1 shows the numbers of academic programs that provided social work education in 2007 and 2010. According to the Korean social work statistical yearbook (2012), the number of departments of social welfare increased to 31 in 2010, and the number of departments that are similar to social welfare increased to 242. The number of social welfare educational agencies increased by 130% from 2007 to 2010. While the quality of social work education differs according to the type of academic setting or program, the significant increases in the number of social work education programs indicate that social work has been integrated into Korean culture, and social work education is continuing to expand in South Korea.

Social work curriculum

The Korean Council on Social Welfare Education (KCSWE) currently attempts to standardise the social work curriculum, as the official educational standards did not appropriately guide the social work curricula in colleges and universities. For example, in many social work programs, the link between theory and practice is weak, and there is often no attempt to combine academic education with field education. In fact, one responsibility of the KCSWE is to evaluate and accredit undergraduate and graduate social work and welfare programs; however, the KCSWE is not currently conducting accreditation reviews to verify that each program is appropriate.

Nevertheless, the KCSWE recommended 35 courses for achieving the required competencies for the social work profession. The recommendations serve as a resource for social work educators in curriculum development. In addition, the 35 courses help students who are enrolled in a minor in social work or who are interested in obtaining a social work degree through a continuing education program to obtain the eligibility requirements for a level 2 social work certification. Generally, the courses are categorised into four domains: (1) required courses that prepare students for the social work licensure examination, (2) required courses with material that is not included on the social work licensure examination, (3) elective courses, and (4) optional courses. The first domain refers to the required courses that are included in the social work licensure examination as eligibility requirements for a level 1 social work certification (e.g. Human Behavior and Social Environment, Social Work Practice, etc.). The second domain refers to courses that are required for credits but are not included in the social work licensure examination, but students who would like to obtain a level 2 social work certification are encouraged to take these courses (e.g. Introduction to Social Welfare and Social Work Field Instruction). The third domain includes elective courses that should be taken for credits to obtain a level 2 social work certification, and students are required to take at least four courses (e.g. Family Welfare, Social Work Practice for the Elderly, etc.). Finally, there are several optional courses that are neither required nor elective. Certain social work programs offer these courses based on students’ needs and national and international trends (e.g. Family Therapy, Poverty, etc.). Courses categorised into each domain are detailed in Table 12.2.

Field education

Field education is an integral part of the social work and welfare programs in South Korea. According to section 2.1 of the Enforcement Ordinance of Social Welfare Service Act, corporations, institutes, agencies and groups that are related to social work and welfare are used as field instruction sites. To qualify as a field supervisor, social workers should (1) hold a level 1 social work certification and have at least three years of social work experience or (2) hold a level 2 social work certification and have at least five years of social work experience. A minimum of 120 hours of field experience is required, and a maximum of three credits can be earned for one field placement. Generally, students can decide whether to complete the field placement during the summer/winter vacation or during an academic period (spring/fall). If the students are engaged in the field placement during an academic period, they are required to work eight hours per week and can complete their placement after a minimum of 120 hours. If students are in the field during a vacation, they are required to work eight hours per day and five days per week to complete the minimum 120 hours (Korea Association of Social Workers 2010).

The field education standards for social work and welfare programs are that field settings should provide social work education from qualified field supervisors. The basic field supervisor qualification is a level 1 social work certification. Field supervisors with a master’s degree are required to have taken the field practice course at least one time during their academic program. Additionally, field supervisors should have at least 5 years of post-master’s social work experience and should have supervisory experience. Field supervisors with a doctoral degree are required to have taken the field practice course at least one time during their academic program and should have at least one year of post-master’s social work experience that included supervisory experience.

Generally, the field practice experience begins with the basic tasks of field experience and clinical practice, including orientation and administrative tasks. The orientation includes an introduction to agencies and regions, client-related practices, the attitudes and roles of students, the overall schedule, and assignments. In addition, the preparation and submission of case and daily reports are reviewed. The administrative tasks are associated with the management and preparation of agency operations and budgets as well as decision-making processes. Next, the students are engaged in diverse activities, including case management, individual and group therapy and programs, community-based social work practice and organisation, and social development. The content of social work field practices is dependent on students’ preferences and on the needs of social service agencies. Students may be actively involved in individual counselling, family counselling and therapy, social surveys, or community-based approaches. During the field experience, students are required to submit progress notes for case interventions and daily activity notes. Table 12.3 indicates the number of students who were engaged in field experiences in 2012.

Social work licensure system

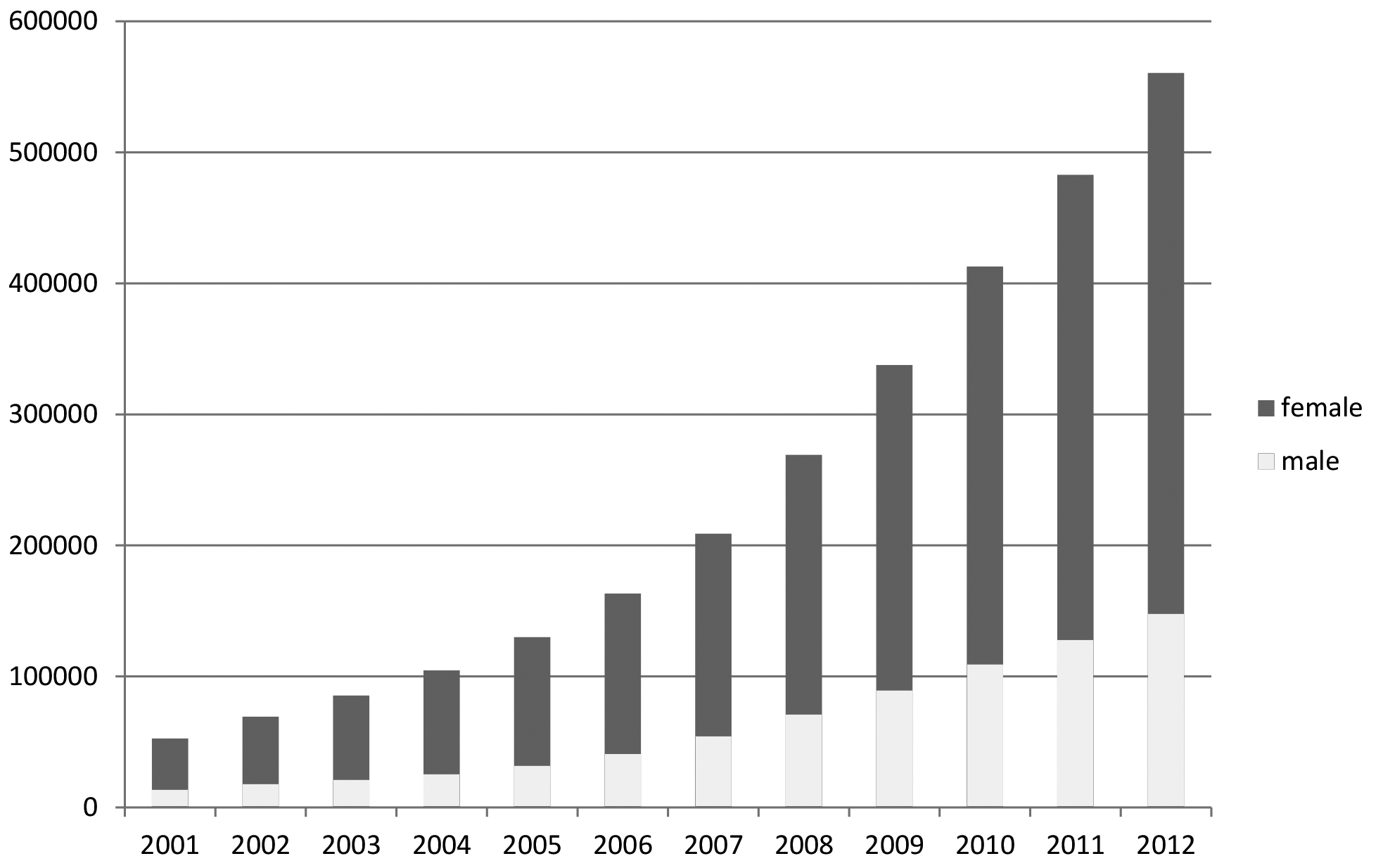

The major focus of social work education in South Korea has been to prepare students for the social work licensure examination (Hong et al. 2011). According to section 11.3 of the Enforcement Ordinance of Social Welfare Service Act, the Korean Government requires that people take a national examination to obtain a level 1 social work certification. For a level 2 social work certification, undergraduate students take at least 10 required courses and four elective courses related to social work and welfare, which is the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree. Graduate students must major in social welfare or social work (other majors are not allowed) and take six required courses and two elective courses, and they must complete one social work field experience; this coursework is equivalent to a master’s or doctoral degree. The required courses for the social work licensure examination are grouped into three categories: (1) basic social welfare (i.e. Human Behavior and Social Environment/ Research Methods for Social Welfare); (2) social work practices (i.e. Social Work Practice, Skills & Techniques for Social Work Practice, Community-based Social Services and Practices); and (3) social welfare policy (i.e. Social Welfare Policy, Social Welfare Administration, Introduction to Social Welfare Law). The Social Welfare Service Act in South Korea requires that social workers receive at least eight social work continuing education credits per year to maintain the social work certification. The continuing education system caters to professionals at different levels and in different careers. Figure 12.1 indicates the number of licensed social workers in South Korea.

With the general social work licensure examination, several specialties, such as mental health social workers, medical social workers, and school social workers, have established their own certification and training programs. For example, to obtain the level 2 mental health social work certification, the Korean Association of Mental Health Social Workers (KAMHSW) requires that students receive at least one year of training in mental health education agencies after passing the social work licensure examination. In the training agencies that are assigned by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the trainees should receive a total of 1000 hours of training, including 150 hours for theoretical education, 830 hours for practical education, and 20 hours for academic activities. The level 1 mental health social workers should hold at least a master’s degree in social work/welfare and must be trained by mental health professional agencies for at least 3 years. After obtaining a level 2 certification, trainees should receive at least five years of training in mental health agencies, a mental health centre, social rehabilitation facilities, long-term mental health facilities, an alcohol counselling centre, or other counselling centres. Trainees should also obtain more than 20 points related to mental health academic activities and pass the qualification test of the Korean Association of Mental Health.

In 2008, the Korean Association of Medical Social Workers (KAMSW) established a certification system for the purposes of enhancing the professionalism of social workers in health care settings, providing differentiated health care services, and managing the quality of health care services. In addition, the KAMSW organises the training system for trainees who want to work in medical care settings.

School social workers have received school social work education and training in addition to field experiences in school social work settings, but the Korean Government does not provide any qualification regulations for school social workers. As a private section, the qualification committee in school social work permits people who have trained at least 20 hours per year to commit to being a school social worker.

Associations for social work education

Three associations represent social work education: (1) the Korean Council on Social Welfare Education (KCSWE), (2) the Korea National Council on Social Welfare (KNCSW), and (3) the Korea Association of Social Workers (KASW). Each association has a different mission and plays a different role in improving the quality of social work education in South Korea. We will briefly introduce the major activities and primary roles of each association.

The Korean Council on Social Welfare Education (KCSWE)

The KCSWE was established in 1966 for the purposes of improving networks with international agencies and developing social work education. The major activities include conducting research on social work education curriculum, releasing publications related to social work education, and coordinating curricula among national and global social work agencies. The KCSWE is composed of the following seven committees: general affairs, education, international, external cooperation, evaluation and accreditation, editing, and credentials and membership. Beyond the responsibilities and duties of each committee, the KCSWE disseminates guidelines for social work courses, holds annual meetings with the committee chairs, and evaluates social work education programs.

Korea National Council on Social Welfare (KNCSW)

As a public organisation that was established by the Social Service Act, the KNCSW’s diverse activities contribute to the development of social welfare in South Korea, such as coordinating and consulting on efforts to promote the private sector of social welfare, developing policy, conducting surveys and research, providing education and training, performing volunteer activities, conducting informational business, and implementing activities for economically disadvantaged and underserved populations. The KNCSW’s major functions and responsibilities include the following: (1) developing social work research and surveys, (2) preparing policy-related proposals, (3) educating and training social workers, (4) promoting social welfare, (5) engaging in fundraising for social services and research, (6) creating publications, (7) supporting and collaborating with city and provincial social welfare agencies, (8) coordinating with internal social work agencies, (9) promoting volunteer activities, (10) developing social work services and resources, (11) developing informational projects, and (12) conducting other social work services that are assigned by the Ministry of Health and Welfare. Since the revision of the Social Service Act in 1998, all social welfare agencies are required to be evaluated and accredited at least once every three years; thus, the KNCSW is responsible for reviewing and evaluating the qualifications of all social work agencies. In addition, the KNCSW operates the Volunteer Management System, operates the food bank, and manages under-served populations.

Korea Association of Social Workers (KASW)

According to the Social Service Act section 46, the KASW is the support organisation for social workers. The KASW develops and disseminates professional knowledge and skills, provides social work education and training for quality improvement, and increases the welfare of social workers. The major activities include developing and disseminating professional knowledge and skills for social work and welfare, providing education and training for social workers’ professional practices, conducting surveys and research related to social welfare, creating publications, and providing educational opportunities and collaborations with national and international social work professionals. The KASW comprises 16 associations for social workers in cities or provinces. In addition, the KAMSW, KAMHSW, and Korean Society of School Social Work are members of the KASW. The KASW manages a continuing education centre that administers the level 1 certification test and provides over 8 hours of continuing education per year for social workers. To maintain their qualifications, social workers are required to enrol in courses on social welfare ethics and values, social work practices, social welfare policy and laws, social welfare administration, and research methods in social welfare.

Contemporary challenges and the future of social work education in South Korea

The growth in the number of social workers in the past 6 decades has been accompanied by a dramatic shift in social work education in South Korea. Given that many people were interested in becoming social work professionals and were motivated to attend social work programs for different reasons, professional social workers must be successfully and continuously trained to meet their professional goals. Although social work education in South Korea has been growing at a fast rate, the quality of social work education (i.e. academic programs, curriculum, field education, and the social work licensure examination), which should align with an increase in the quantity of programs, was not fully considered. In fact, social work education in South Korea should consider two issues related to educational and social welfare policy goals. First, social work and welfare programs at colleges and universities are generally designed to prepare professional social workers for different types of clients. Second, social workers can be employed by several types of social service agencies that all depend on social welfare policies to satisfy the needs of their consumers and providers (Lee & Nam 2005). Given that social welfare policy in South Korea currently requires social workers to play diverse roles and to serve diverse functions in social service agencies, a vision is necessary to improve the quality of services and to develop systems of social work education in South Korea.

First, there are many different types of social work education programs in South Korea, and each type has a unique educational mission and set of objectives. The KCSWE recently announced that only 77 schools were registered in the KCSWE, which indicates that only 16% of the schools are registered KCSWE members. Given that the KCSWE disseminates guidelines for social work and welfare courses and evaluates social work education programs, all schools should register with the KCSWE so that they can provide appropriate and systematic social work education. The KCSW should also initiate and conduct accreditation reviews to verify each program.

Second, most of the social work and welfare curriculum is based on the social work licensure examination; courses that are not included in the licensure examination are rarely considered. Furthermore, courses are still based on the content and culture of the United States, and the course content does not always consider the South Korean context (Hong & Han 2013). To improve students’ competencies, the social work and welfare curriculum should reflect current social problems and international changes. For example, issues related to multiculturalism and diversity have been raised as a result of the rising rate of immigration in South Korea; thus, courses related to international social work and cultural diversity should be included in the social work and welfare curriculum.

Koreans also face other diverse issues that have not been considered. For example, foreign workers, women immigrants by marriage, mixed race children, and people who have relocated from North Korea (known as ‘sae-ter-min’ in Korean) are becoming clients. Professional social workers need to provide diverse social services that can help these clients adjust in new social environments. Meanwhile, the international standard for social work education requires that social work education address diversity (Han & Kim 2006). A number of social work programs at colleges and universities in South Korea include courses related to international and multicultural social work in their curricula. For example, the graduate school of social welfare at Ewha Womans University offers classes such as International Social Work and Cultural Diversity and Social Work Practice (Hong et al. 2011). The underlying purpose of the current curricula on multiculturalism is to educate the future generation of social workers about the importance of social development and joint collaborations with other countries, particularly underdeveloped countries. To achieve this purpose, courses should be developed to enhance cultural competency through joint collaboration and partnership between social workers and social service agencies for ethnic minorities and immigrants in South Korea. Beyond the social work licensure examination, the following courses on social changes and trends may be valuable: Human Sexuality and Social Work Practice, Unification and Social Welfare, Understanding Social Enterprise in Theory and Practice, Military Social Work, Cultural Diversity and Social Work Practice, International Social Work, International Cooperation for Regional Development, and Regional Study and International Volunteerism.

Third, the qualification standards for field experience supervisors in South Korea are insufficient for providing the appropriate practical skills and competencies to students. Specifically, to be an academic supervisor, the qualification standards require at least one year of practical social work experience under the supervision of an individual with a doctoral degree; these academic supervisors do not have enough practical social work experience to provide student supervision. Furthermore, the field supervisors in the field tend to provide practice-focused supervision only, which does not appropriately link the experience with academic knowledge and skills. For two-year colleges and cyber colleges, the field education is not long enough to be regulated by a systematic and organised manual.

Currently, the minimum required time for field education is 120 hours. In fact, that amount of time is relatively and absolutely limited to applying academic knowledge and skills to field settings, acquiring experiences related to social work values, and practicing concrete skills with clients. Most social work programs in the United States require approximately 1000 hours for two-year master’s programs. Consequently, additional hours should be required to provide experience in social work skills and values.

In addition to increasing the qualifications of supervisors and the amount of time in the field, the core content of field education should be enhanced to improve the quality of field education. During the orientation, academic supervisors at schools and universities should address the goals, attitudes, ethics, expectations and emotional feelings of students in relation to their field placements. The KASW recently standardised the process of obtaining field supervisor and academic supervisor certifications. To obtain the certifications, courses on the theory of supervision, field administration, writing proposals for field supervision, attitudes and roles for field supervisors, case management, program development and evaluation, resource development in non-profit organisations, organisation management and administration, and regulation for financial accounting are offered. Supervision-related continuing education programs should enhance the capabilities of field supervisors (Jang 2011). In addition, each agency should support supervisors who require additional attitude, skill and knowledge development.

Fourth, the KCSWE recently redefined courses to standardise social work education in South Korea, and courses to pass the social work licensure examination were established. This development implies that the minimum requirements for social work education were standardised to follow the regulations of the Social Work Act in South Korea. For example, to be a certified medical social worker or mental health social worker, students are required to receive training in field settings for a certain time period before entering the actual field. General social workers who are employed in general social service agencies must also receive annual continuing education. While regulations regarding social work and welfare have been established, efforts to address the working conditions of social workers, such as salary, conflicts and the environment, are relatively undeveloped. Indeed, compared to other professionals, the salaries of social workers are lower and their rate of leaving the profession is higher. Furthermore, everyone who passes the social work licensure examination automatically receives the level 1 certification, which allows individuals to work in a social work setting without receiving additional training in social work practices. To improve both social work competencies and job satisfaction in the social work field, people should be sufficiently educated to apply their knowledge and skills to clients. Consequently, additional professional training after obtaining the certification may be necessary to improve workers’ individual competencies and to translate their skills into real-life practice. Furthermore, a positive relationship between the schools and social service agencies will be helpful to enhance the quality of social work education, increase skills and knowledge that can be applied to practice, better understand social changes, and maximise the engagement of students in field settings.

Conclusions

This chapter addresses many of the efforts to enhance social work education in South Korea and the challenges in this process. These efforts reflect the growth in social work education in South Korea. However, these efforts do not always reflect the true gaps and challenges in the goals of social work education in South Korea. Nonetheless, the challenges do suggest further areas for increased attention, including variation in the quality of academic programs; the need for curriculum development within bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral education programs; content on working with new clients; differentiating skills and practice preparation; barriers to interactions between students and faculty; faculty development; collaborative efforts between schools and field sites; the quality of the social work licensure examination; continuing education for licensed social workers; and engagement in global issues. We hope that this chapter promotes the improvement of social work education in South Korea and challenges us to think about the similarities and differences in social work education between South Korea and other countries.

References

Han, I.Y. & Kim, Y.J. (2006). Case of diversity education in Korea. Korean Journal of Social Welfare Education, 2(1): 105–20.

Hong, J.S. & Han, I.Y. (2013). Call for incorporating cultural competency in South Korean social work education. In C. Noble, M. Henrickson & I. Y. Han (eds), Social work education: voices from the Asia Pacific (pp. 3–28). Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Hong, J.S., Kim, Y.S., Lee, N.Y. & Ha, J.W. (2011). Understanding social welfare in South Korea. In S.B.C.L. Furuto (ed.), Social welfare in East Asia and the Pacific (pp. 41–66). NY: Columbia University Press.

Jang, S.M. (2011). Collaboration between field education faculty and field supervisor in Korea. In C. Noble & M. Henrickson (eds), Social work field education and supervision across Asia Pacific (pp. 45–63). Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Korea Association of Social Workers (2012). Korean social work statistical yearbook. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare.

Korea Association of Social Workers (2010). Social work field practice: survey and guideline. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare.

Lee, H. S. & Jung, F. R. (2012). Social work practice. Seoul: Chungminsa Publishing.

Lee, H.K. & Nam, C.S. (2005). Fifty years’ history of social welfare education in Korea – in the context of institutionalisation of social welfare and universalisation of higher education. Korean Journal of Social Welfare Education, 1(1): 69–95.