PARADISEC: its history and future

In 2002, linguists and musicologists at the Universities of Sydney and Melbourne and the Australian National University formulated a grant application with a view to establishing a digital archive.1 Most of the researchers had accumulated field recordings of language and culture from the Pacific region and South-East Asia, near neighbours of Australia. While the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) caters for recordings and materials originating in Australia, there was no local repository for the research materials of Australian researchers who collected materials beyond Australia’s borders. The group set about learning what were the best ways to digitise the audio and what metadata should be used to describe it, and undertook a stocktake of known relevant collections and a digitisation trial at the University of Sydney in 2002. We sought advice from relevant agencies (in particular from the National Library of Australia and the National Film and Sound Archive). This advice was particularly valuable in allowing us to determine appropriate metadata standards (we use Dublin Core and Open Archives Initiative metadata terms as a subset of our catalogue’s metadata) and for the more hands-on requirements of cleaning and repairing mouldy or damaged analogue tapes.

Having designed the system, we applied for Australian Research Council (ARC) funding to buy a Quadriga workstation and associated equipment (playback machines, a vacuum oven for treating tapes) and to fund staff to begin digitising the several hundred tapes that had been part of our first survey of such material. The newly funded Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC) began in 2003 by digitising collections of audio recordings made since the early 1960s by Australian National University (ANU) researchers, and also took in recordings from the Universities of Sydney and Melbourne digitised as part of the 2002 trial. We designed a metadata system and built a metadata catalogue, initially written in FileMakerPro, then, after a couple of years, moved to an online SQL/PHP system. With a further round of Linkage Infrastructure, Equipment and Facilities (LIEF) funding in 2011, we built our own online system (called Nabu) that manages the ingestion, description and curation of our repository.

The design of PARADISEC from its inception was for a long-term, secure storage facility for the precious materials gathered by fieldworkers, and one which would not only keep the materials safe, but would make them ultimately accessible to the communities from which they came, as well as to future researchers. In this chapter, we explore the evolution of PARADISEC as a digital archive aspiring to long-term sustainability in a funding environment based around short-term project funding models. We also describe the changing face of PARADISEC, and document attempts to make the materials within the archive more widely accessible, while still safeguarding the privacy of those whose words and ideas have been recorded.

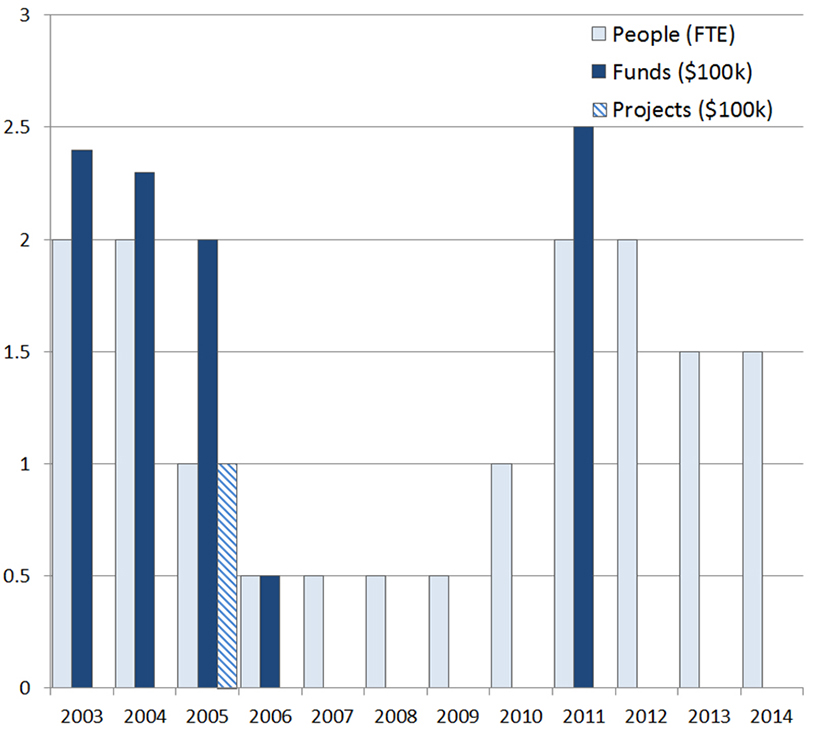

As can be seen in Figure 1, funding over the past decade has been sporadic. In only four years (2003, 2004, 2005 and 2011) were we successful in obtaining infrastructure funding, despite several additional applications to the ARC’s LIEF program. To keep staff employed between grants, we have been supported by our host institutions and have also been able to attract paid work digitising audio collections for other parts of our universities and for relevant external bodies.

Figure 1 Funding and staffing history of the PARADISEC repository.

Over the ten years of PARADISEC’s operation, the repository has grown to represent over 860 languages from across the world (see Table 1). While initially the archive was confined to cultural materials from the Pacific region and South-East Asia, demand for a suitable repository for research materials led to an expansion of scope. A smaller number of materials from North America, Africa and Europe now form part of the archive. As of September 2015 the repository holds 94,500 files, of which 14,200 are WAV audio files, amounting to over 5100 hours of audio. In 2011 we initiated an online survey2 to locate further endangered analogue collections and to work with their custodians to find funds to digitise and curate them before they are lost.

What is in the PARADISEC repository?

PARADISEC collections range in size and scope from hundreds of recordings on a particular language made in the course of extensive fieldwork, through to small opportunistic compilations of a few short examples recorded in a given language. Record types range from narratives through to sung, chanted and spoken performances as well as instrumental music. The collections from the 1960s and 1970s typically represent the work of deceased or retired scholars so there is usually limited contextual information to include in the catalogue. Occasionally there are handwritten transcripts of these recordings which we have included as scanned TIF or PDF files.

PARADISEC makes information available in an ethically appropriate way and we have established working relationships with agencies in our region such as the Vanuatu Cultural Centre, Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies, University of French Polynesia, and the University of New Caledonia, among others (Thieberger and Barwick 2012). In 2014 we received funding to digitise some hundreds of tapes held by the Solomon Islands Museum in Honiara. We have started a crowdfunding campaign to try to raise the funds necessary to do this work and to locate more endangered collections of analogue recordings.3

The value and potential for ongoing enrichment of the archive by making it as discoverable as possible was made clear when we had a request from Diana Looser, then a PhD candidate in Theatre at Cornell University in the USA, who was writing a dissertation on Oceanic theatre and drama. She needed access to a play that was listed in our catalogue but existed nowhere else that she could find. In his collection TD1, the linguist Tom Dutton had included a tape of playwright Albert Toro’s Sugarcane Days recorded from Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Radio Port Moresby.4 Looser transcribed the tapes and prepared the only extant version of the script, which she then redeposited in the collection. This re-use of research material in new ways can only be achieved if that material is stored in accessible locations with licences for use in place and with a catalogue that provides sufficient information to allow it to be located.

Technicalities

We began by installing a Quadriga analogue-to-digital workstation and developing a system architecture that included data storage and backup, naming conventions, a metadata schema, a workflow for identifying eligible recordings (by assessing their physical state and contents), deposit and access conditions and a catalogue. This catalogue presents a set of metadata elements to the user with dropdown menus to enforce standard forms, in particular for terms that are exposed to external harvesting tools to allow remote searching of the catalogue. These terms include country names (ISO 3166-1), language names (ISO 639-3), and datatypes, among other elements.

The online catalogue (Nabu5) has been redeveloped over time in response to users’ comments. It currently exports a feed that is harvested by the Open Archives Initiative, the Open Language Archives Community, and the Australian National Data Service, all of which helps make items in the archive more discoverable. Each item in the archive has its own deposit conditions and over half (some 5500 items out of 9800) can be seen or listened to online by registered users – that is, those who have agreed to the conditions of use and registered their email addresses. The remaining items require some kind of permission from the depositor, but we are working with depositors to reduce the number of items in that category.

The structured metadata requirements of our catalogue oblige the depositor to provide rather basic information that they may not previously have compiled, including, for each item, a title, date of creation, language spoken, and country in which the item was recorded. Further information can include: the role of participants; the language name as it is known locally (which may vary from the standard form); the type of information (lexicon, song, narrative and so on); geographic location (given by a bounding box on a map); and a free text description of the item which can be as rich as the depositor wants. All of this can be improved on by subsequent researchers who may re-use the data in their own projects (as we saw above with the item from Tom Dutton’s collection).

Research uses of PARADISEC

An example of the research use that a citable archival repository like PARADISEC offers is the work done by Åshild Næss (2006) on the nature of the languages of the Reefs-Santa Cruz (RSC) (Solomon Islands). The late Professor Stephen Wurm (of the ANU) had a considerable number of recordings from these languages in his house and office when he died. Næss was based in Norway and unable to get copies of the recordings, most of which were uncatalogued and known to her only by oblique references in Wurm’s work. As she notes, ‘Although Wurm published a number of papers on RSC, the actual data cited in these publications is limited to word lists and a few handfuls of frequently repeated example sentences. This makes it difficult to determine to what extent the structural claims, in particular, are actually supported by the data. Being able to evaluate and analyse Wurm’s primary data will be of invaluable help in the effort to resolve the question of the origins of the RSC languages’ (Næss 2006, 159).

Such recordings are important for researchers, and we present them as playable objects in our online repository for users to access. An important additional functionality we have developed to make it easier to present interlinked text and media corpora is the Ethnographic E-Research Online Presentation System (EOPAS),6 which takes the media outputs of linguistic fieldwork together with texts7 that are time-aligned to the source media and presents them online. EOPAS provides information about a text that satisfies several different needs at the same time. It gives the casual web user information about a text, showing grammatical and morphological complexity, but also allowing that complexity to be hidden via a toggle switch if desired. It allows a corpus of any number of texts in a language to be presented and searched, with a keyword-in-context view of any given word or morpheme (parts smaller than a word), all resolving via a mouse click to the context of the morpheme.

Community access to PARADISEC

A key aspect of the creation of digital repositories like PARADISEC is that they can provide access to primary material for any authorised user. This is essential in the current archiving environment where cultural heritage communities have become increasingly active users of digitised archival material originating in their communities (Barwick 2004). Digitised collections of primary data are now easily findable, but people also expect to be able to access them (Landau and Fargion 2012, 128). In Australia, the increasing involvement of Indigenous people in decision-making for archives and their collections means that objects are no longer removed from their creators and preserved in distant locations. The return of historical and archival materials in digital forms has become central to discussions of technology in Indigenous Australia, as evidenced by the outcomes of recent conferences: the AIATSIS National Indigenous Studies Conference (2009) and the Information Technologies and Indigenous Communities Symposium (2010). In Ormond-Parker et al.’s summary of these discussions, the group calls for ‘increased support for programs which support the return to community-based archives of digitised heritage objects, including photographs, audiovisual recordings and manuscripts from national repositories’ (2013, xii).

The accessibility of archival collections is essential to their long-term sustainability, and the solutions offered by digital distribution make it possible for a digitised recording to be held in a central location and yet be accessible from any other location in the world. This means that digital recording archives are able to circumvent some of the problems faced by museums and archives of physical objects. Several Indigenous scholars have noted that careful decisions about making materials accessible are essential for Indigenous people to consent to the ongoing curation of their cultural materials (O’Sullivan 2013; Aird 2002). PARADISEC’s access conditions allow for restrictions to be placed on access so that online digital objects are both easily accessible to individuals with the correct permissions, but also able to be hidden from others. Cultural restrictions notwithstanding, in the long-term, the aim is to make the repository as openly accessible as possible.

Authorisation for access to most material is obtained by supplying a valid email address. Delivery of media allows for web or mobile phone access, and, in cases where there is not yet easy internet or mobile coverage, we have also trialled simpler solutions, like making CDs or creating iTunes installations for school computer systems, as author Nick Thieberger did in Erakor village in central Vanuatu. Each time he visited his fieldsite, he was asked for copies of photos or recordings, and he realised the need for these to be available when he was not present. When he first visited Erakor village there was intermittent electricity available, usually, in the house he lived in, only in the evenings. CD players were common enough, so he was able to make audio CDs with tracks made up of various villagers telling stories or singing songs, or the choir singing hymns. These and the liner notes came out fairly readily from his text/media corpus; creating the template CD took about two hours and burning multiple copies was then a simple matter. Over the years the electricity supply has become more reliable, and the school was given a set of ten computers by their sister school in Australia. Having heard about Linda Barwick’s experience (Barwick and Thieberger 2006) in establishing an iTunes installation at Wadeye,8 he decided to do the same thing at Erakor school. With time-aligned transcripts, it is not a large task to locate the parts needed to create a set of stories told by elders, which become tracks in iTunes. Users can then establish favourites and burn their selection to a CD for their use at home.

The change in access to archives has also had a significant impact on archiving practice itself. While PARADISEC was originally designed to house digitised but born-analogue recordings, now it is being inundated with born-digital material. These collections are created from the outset in formats that can be deposited in the archive directly from the field or soon after researchers’ return from fieldwork. In this way researchers have a safe copy of their primary records, and are able to cite those records with the persistent identification provided by an archive. Archiving before the analysis makes the research grounded and replicable and turns on its head the more traditional approach of archiving primary recordings at the end of one’s research career (Barwick 2004). Through publications and numerous training workshops, over the years PARADISEC has also provided information to assist researchers and cultural heritage community members to plan their fieldwork so as to create recordings that are archivable from the outset.

Transcription

While many cultural heritage communities find access to the original recordings made by fieldworkers far more valuable than what has been written about those recordings by foreign researchers (Seeger and Chaudhuri 2004), a media recording with a transcript is more useful than a recording on its own. A transcript that is time-aligned to the media it transcribes is more useful again, providing the possibility for linking the text (utterances or words) directly to the position that they occur in the media. Current field methods include the use of tools like ELAN9 for creating such transcripts, but emerging methods for automated alignment of a transcript and media (e.g., WebMAUS10) promise to speed up this otherwise time-consuming process and can, as a first step, identify segments in the recording according to acoustic characteristics. Many legacy items in the PARADISEC repository have little metadata and no transcripts and would benefit from having a simple description of their content as a first step towards creating more detailed descriptions. In this way it may be possible to automatically identify different speakers, varying performance types, and spoken tape identification at the beginning of the recording, all in order to improve the description of their contents.

Some PARADISEC collections, on the other hand, are heavily annotated and will allow re-use and re-analysis in future research projects, and can also be presented in online services representing languages of the world. Over 860 languages are represented in PARADISEC with a variety of styles, including songs, narratives and elicitation. Given this rich reserve of material, there are great possibilities for re-use of these collections (subject of course to deposit conditions). It may be possible, for example, to establish crowd-sourced annotation of legacy material, either at the level of simply identifying parts of a recording or – where suitably skilled transcribers are available – to provide transcripts. We are also developing methods for delivery of the catalogue and files via mobile devices.

Citing primary research records

As mentioned above, we are particularly interested in providing advice and training for researchers so that their records (be they recordings, photographs, transcripts or more analytical work like corpora, dictionaries or grammars) will be archivable and re-usable by others in future, emphasising the importance of linguistic data management (Thieberger and Berez 2012) and based on the principles established by Bird and Simons (2003) for the portability of research material. It is obvious from this training that the more a researcher knows and implements methods for creating good archival forms of their data, the easier it is for an archive to accession that material. The researcher’s own research materials will also be easier for them to access in the future.

PARADISEC has a blog11 that often provides examples of new methods or summaries of projects using innovative approaches. We also helped to establish the Resource Network for Linguistic Diversity12 which has a mailing list and FAQ page on relevant topics aimed at supporting many aspects of language documentation and language revitalisation.

Recognition

We have created nine terabytes of curated records that, without our work, would otherwise be only uncatalogued analogue material. As a result, PARADISEC was cited as an exemplary system for audiovisual archiving using digital mass storage systems by the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives13 and was also included as an exemplary case study in the Australian government’s Strategic Roadmap for Australian Research Infrastructure.14 In 2008 we won the Victorian eResearch Strategic Initiative (VeRSI) eResearch Prize (Humnities, Arts and Social Sciences category). In the words of the judges: ‘PARADISEC is an outstanding application of ICT tools in the humanities and social sciences domain that harnesses the work of scholars to store and preserve endangered language and music materials from the Asia-Pacific region and creates an online resource to make these available.’

We are rated at five stars (the maximum rating) in the Open Language Archives Community15 for the quality of our metadata. In 2012 PARADISEC was awarded a European Data Seal of Approval16 and, in 2013, PARADISEC’s collections were inscribed in the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World program.

About this volume

This publication commemorates the first ten years of PARADISEC with a selection of papers that originated in a conference held in December 2013.17 As a reflection on the ways that the archive has developed over the last decade, the chapters included here come not only from the archive itself but from collaborations between archivists, users and researchers depositing materials in the archive.

The volume is divided into three parts, each of which deals with a different aspect of PARADISEC’s archiving legacy. The first part considers how archiving practices feed into broader methods of research practice. Daniela Kaleva applies models of performativity to questions of research quality and impact in assessing the contribution of archival collections in research outputs. Andrea Berez shows how approaches to teaching can be informed by a long-term view, which compels students to practice archiving even at the beginning of their collection of field data. David Nathan seeks to define the reach of digital archives in the current context, exploring how audiences discover, access and interact with modern archives.

In the second part of the volume, the focus is on how archives themselves can be enriched. Peter Withers demonstrates KinOath, a program enabling the documentation and preservation of kinship data across diverse cultural contexts. Catherine Bow, Michael Christie and Brian Devlin then take the archive back to communities, demonstrating how archival materials can be mobilised by creating interactive materials for the use of current community members. Jennifer Post considers how archives can enrich musical instrument data so that it is contextualised by practices, recordings, images and experiences of music.

The focus of the third part is on communities and the way the products of the archive feed back into community practice. Andrea Emberly considers some of the ethical dilemmas inherent in dealing with archival materials that depict children. Sally Treloyn and Rona Googninda Charles show how community interactions with ethnomusicological archival collections can lead to innovative contemporary practices in endangered dance-song traditions.

As a postscript to the issues of reach, community and access for ethnographic archives explored in the main body of the volume, we end with Lisa MacKinney, Cat Hope, Lelia Green and Tos Mahoney’s introduction of the Western Australian New Music Archive and its objective to create a lasting repository of new music performance.

Conclusion

Archiving of research outputs is central to language documentation and to the preservation of recorded oral tradition. Researchers have to ensure that speakers are able to locate records made with them or with their ancestors; properly constructed repositories can provide that function. From a research perspective, the provision of carefully curated scholarly material provides the basis for further research, and for validation of the research that motivated the collection of the material in the first place. PARADISEC aims to be as responsive as possible (given our shoestring budget) to the individual needs of researchers, in particular those located in isolated and remote communities who will be the main beneficiaries of the digitised set of materials we have produced over the past decade.

Works cited

Aird, Michael (2002). ‘Developments in the repatriation of human remains and other cultural items in Queensland, Australia.’ In The Dead and Their Possessions: Repatriation in Principle, Policy and Practice, edited by Cressida Fforde, Jane Hubert and Paul Turnbull, 302–11. London: Routledge.

Barwick, Linda (2004). ‘Turning it all upside down … Imagining a distributed digital audiovisual archive.’ Literary and Linguistic Computing 19(3): 253–63.

Barwick, Linda, and Nicholas Thieberger (2006). ‘Cybraries in paradise: New technologies and ethnographic repositories.’ Libr@ries: Changing Information Space and Practice, edited by Cushla Kapitzke and Bertram C. Bruce, 133–49. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum. http://repository.unimelb.edu.au/10187/1672.

Bird, Steven, and Gary Simons (2003). ‘Seven dimensions of portability for language documentation and description.’ Language 79: 557–82. http://tiny.cc/2003-7dim-birdsimons.

Landau, Carolyn, and Janet Topp Fargion (2012). ‘We’re all archivists now: Towards a more equitable ethnomusicology.’ Ethnomusicology Forum 21(20): 125–40.

Næss, Aashild (2006). ‘Past, present and future in Reefs-Santa Cruz research.’ In Sustainable Data from Digital Fieldwork: From Creation to Archive and Back, edited by Linda Barwick and Nicholas Thieberger, 157–62. Sydney: Sydney University Press. http://hdl.handle.net/2123/1299.

Ormond-Parker, Lyndon, Aaron Corn, Cressida Fforde, Kazuko Obata, and Sandy O’Sullivan, eds (2013). Information Technology and Indigenous Communities. Canberra: AIATSIS Research Publications.

O’Sullivan, Sandy (2013). ‘Reversing the gaze: Considering Indigenous perspectives on museums, cultural representation and the equivocal digital remnant.’ In Information Technology and Indigenous Communities, edited by Lyndon Ormond-Parker et al., 139–49. Canberra: AIATSIS Research Publications.

Seeger, Anthony, and Shubha Chaudhuri, eds (2004). Archives for the Future: Global Perspectives on Audiovisual Archives in the 21st Century. Calcutta: Seagull Books.

Thieberger, Nicholas and Andrea Berez (2012). ‘Linguistic data management.’ In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Fieldwork, edited by Nicholas Thieberger, 90–118. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thieberger, Nicholas and Linda Barwick (2012). ‘Keeping records of language diversity in Melanesia, the Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC).’ In Melanesian Languages on the Edge of Asia: Challenges for the 21st Century, LD&C Special Publication No. 5, edited by Nicholas Evans and Marian Klamer, 239–53. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4567.

1 Chief investigators on the first application (Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Infrastructure, Equipment and Facilities (LIEF) program grant LE0346848) included Allan Marett, William Foley, Jane Simpson, Linda Barwick, David Nathan (all University of Sydney), Peter Austin, Nicholas Evans, Janet Fletcher, John Hajek, Catherine Falk, Steven Bird, Alexander Adelaar (University of Melbourne) and Andrew Pawley and John Bowden (ANU). Subsequent LIEF applications funded were LE0453247, LE0560711 and LE110100142.

2 http://www.paradisec.org.au/PDSCSurvey.html.

3 http://paradisec.org.au/sponsorship.htm.

4 Registered users can hear the first of the audio files of this performance here: http://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/TD1/items/P02179/essences/1019890.

5 http://catalog.paradisec.org.au – the open source code of the catalogue software is available at https://github.com/nabu-catalog/nabu.

7 Actually interlinear text, that is, text with translations at the word or smaller level.

8 See also http://paradisec.org.au/blog/2006/08/indexing-and-managing-song-recordings-for-e-publication.

9 http://tla.mpi.nl/tools/tla-tools/elan.

10 http://phonetik.uni-muenchen.de/BASWebServices.

11 http://paradisec.org.au/blog.

13 International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives (2004). Guidelines on the Production and Preservation of Digital Audio Objects (IASA-TC04). Aarhus: International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives (IASA), p. 51.

14 http://www.nectar.org.au/sites/default/files/Strategic_Roadmap_Aug_2008.pdf, p.42 (viewed 26 March 2014)

15 http://www.language-archives.org/metrics/paradisec.org.au.

16 https://assessment.datasealofapproval.org/assessment_75/seal/html.