9

The Western Australian New Music Archive: performing as remembering

The Western Australian New Music Archive

‘New music’ refers to experimental, exploratory music. The definition adopted for the Western Australian New Music Archive (WANMA) is that used by the Australian Music Centre to define ‘composition in sound’. It includes notated composition, electroacoustic music, improvised music (including contemporary jazz), electronica, sound art, installation sound, multimedia, web and film sound, and related genres and techniques.1 The curation of WANMA is guided by, and confronts the challenges presented by, such a broad definition, with a focus on constructing a representative canon of Western Australian new music history from 1970 to the present day. A drawback of the Western Australian music collection at the State Library of Western Australia (SLWA), and indeed of many other Australian music collections (such as that at the Australian Music Centre and UWA’s Callaway Collection) is the limited nature of the music genres and artefacts included. In the past, archives and libraries have cultivated paper scores and, in some cases, analogue recordings of performances of these scores. Music has moved beyond these paradigms and into areas of improvisation (non-notated music), electronic music, installation (which has physical and visual elements as well as sonic aspects) and applied music (for dance, film and on the internet). WANMA includes materials that reflect contemporary recognition of improvisation and sound art as composition, and therefore the role of recordings as an alternative score, and video as an important documentation device for sound art. As with other contemporary information, WANMA reflects the increasing movement of information into the digital realm, either as digitised or born-digital materials, and seeks to provide both digitisation and digital preservation of materials, allowing for both ongoing availability and access.

Figure 9.1 Western Australian composer and performer Cathie Travers, circa 1992. Photo by Chris Ha.

Western Australia has had a vibrant new music scene for many years, having long contributed to the wider Australian musical context by producing some of Australia’s most important musical figures. These include internationally renowned sound artist Alan Lamb, composer and declared National Treasure Roger Smalley, and composers Ross Bolleter, Jonathan Mustard, Cathie Travers (see Figure 9.1) and Lindsay Vickery, to name a few. And, since its establishment in the mid-1980s, Perth organisation Tura has played a central role in supporting new and exploratory musical endeavours in Western Australia. This takes the form of organising performances by local and international artists, securing funding, assisting with promotion, and supporting the creation, development, presentation and distribution of new music for its artists, organisations and audiences. However, despite the intense level of activity in Western Australia, the wealth of national archival information on new music and its creators is currently based around artists from other states. There is a general lack of awareness of the range of activity in Western Australia, and the future launch of the WANMA will make this activity far more visible and accessible.

A curated collection

There are issues of artistic as well as historical judgement in the determination of the authenticity and reliability of materials archived that make WANMA a curated collection. Chief Investigator Dr Cat Hope (Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts) and Partner Investigator Tos Mahoney (Tura) act as curators, having a detailed knowledge of Western Australian new music practice, and have led the WANMA research since a pilot project was established in 2009. This was when Tura made its entire collection of materials available for an archival analysis and digitisation project, along with its extensive database of Western Australian composers and sound artists. The WANMA will initially incorporate this body of material, which includes audio, video, scans of documents, album covers, newspaper clippings and other ephemera. Once this is completed, the project staff will scope possibilities for other materials to be included as the project progresses. Mahoney’s interest in and ongoing support for regional agendas for new music has also been vital for maintaining WANMA as a truly state-based collection, as opposed to a collection from the city of Perth and its surrounds.

One of the many challenges for the WANMA project has been the definition of ‘Western Australian’. Although it applies largely to printed matter, the policy governing the collection of heritage materials by the SLWA has applications for our decision-making process. Those criteria are:

- A significant proportion of the content is about Western Australia.

- The work was:

- Written or created by a person born in Western Australia and/or who has spent a significant amount of time living in Western Australia;

- Published or created in Western Australia;

- Written or created by a corporate body identified as primarily Western Australian;

- Produced in or about the Indian Ocean Territories.

It is immediately apparent that there is a degree of discretion inherent in these criteria – ‘significant proportion’, ‘significant amount of time’, ‘primarily Western Australian’ – and that those curating the archive must make decisions about what constitutes ‘significant’ to Western Australia, Western Australians and music practice in general.

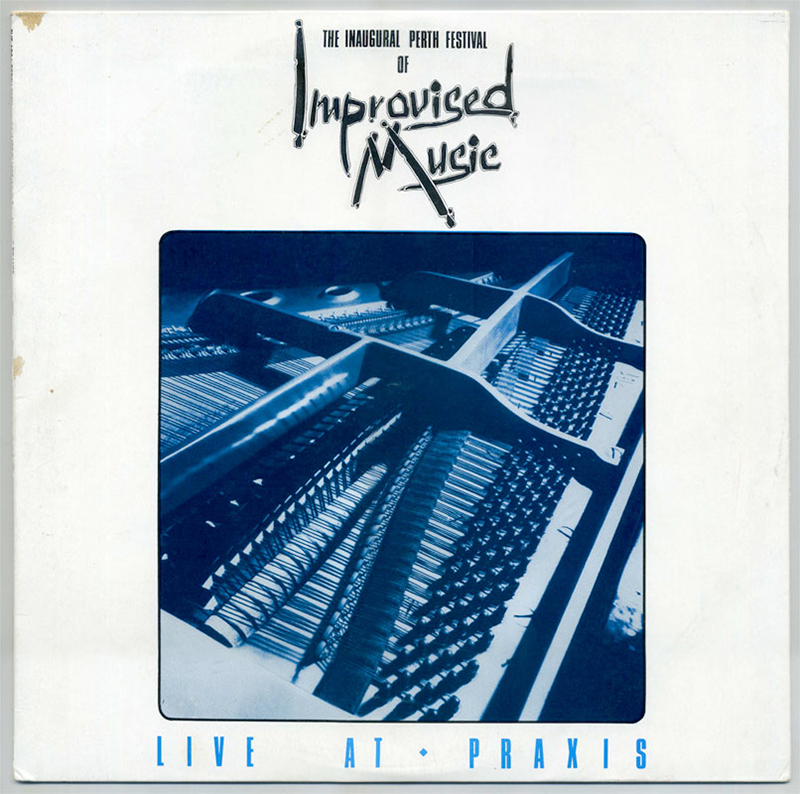

There are arguments for including material for which there is a less obvious Western Australian component – for instance, recordings or ephemera relating to Western Australian premieres of international works, and significant performances by international and interstate composers and performers, particularly if local artists were on the bill or collaborating in some way. A good example of this is provided by Jon Rose, an extremely prolific experimental violinist from Sydney whose work is included in the body of material digitised by Tura. Jon Rose was (perhaps inadvertently) instrumental in the formation of Tura, a process which began when Perth flautist and improviser Tos Mahoney attended and performed at Jon Rose’s Relative Band Festival (a festival of experimental music) in Sydney in 1984 (White 1991, 8). Using this event as a model, Mahoney organised the inaugural Perth Festival of Improvised Music at the Praxis Gallery, Fremantle, in April, 1985. This festival brought together local, interstate and international experimental musicians for a series of public performances and workshops – many captured on an LP released shortly afterward (see Figure 9.2). After a successful second festival in 1986, Mahoney founded Evos Music, an organisation named to reflect and support the idea of music as a constantly evolving art form (Mitchell 1998, 9). In 1997, in conjunction with the inaugural Totally Huge New Music Festival, Evos Music evolved into Tura, which remains the peak body for experimental music in Western Australia. Jon Rose has performed in Perth for Tura on many occasions, most recently in 2010 for the Sounds Outback Festival at Wogarno in regional Western Australia. So, although Rose has never lived in WA, and his recordings are not, for want of a better way to put it, ‘Western Australian themed’, his work, performances, and involvement in experimental music networks have certainly had an impact on the development of new music in Western Australia.

Initial work on curating the archive began with meetings of Hope, Mahoney and the SLWA WANMA project officer. Together, they will sort through the materials in the Tura pilot archive and select items of significance for inclusion in WANMA based on their local knowledge and experience. It is hoped that this process will provide training for the library project officer that will go on to benefit WANMA after the conclusion of the Australian Research Council funding supporting the project at the end of 2015. This is a pivotal factor for the preservation of WANMA, as the project is funded only for a fixed three years (2013–15). However, there is also the danger that the collection will not be curated beyond the period of the project. In an attempt to reduce this danger, the current project officer is working with SLWA’s Liaison, Acquisition and Development section to formulate a collection development policy. This will ensure that, at the end of three years, systems are securely locked in place to guarantee the continued development and progress of the archive. We hope that these policies may also be of use to other institutional projects funded by competitive grants for finite periods.

Figure 9.2 The cover of the LP Live at Praxis, a recording of highlights from the inaugural Perth Festival of Improvised Music, released by Impro Records, Perth, 1985.

A community of practice

The community of practice which frames the composition, performance and consumption of Western Australian new music is of critical importance to the delivery and design of WANMA. Discussing communities of practice in the creative industries in Italy, Marco Bettiol and Silvia Sedita argue that communities of practice develop:

... a pool of skilled people within which it is feasible to develop projects. Communities of practice improve knowledge sharing and help the development of a common identity and social relationships. It is not just a matter of knowhow but also of who knows what that is at the heart of a community of practice. In our perspective, this role [of knowing about others’ work] is necessary to select and further involve qualified people in the project. Projects do not develop in [a] vacuum but within a social structure. (Bettiol and Sedita 2011, 468)

Our archive is designed to be sufficiently nuanced to allow for investigation of the influence of key events and performances upon the genesis of artworks that follow. It is hoped that this will enable explorations of the rich inter-relationships and communication channels between creators, performers, events, genres, venues and organisations in Western Australia’s musical heritage. For example, the wide range of materials in the Tura archive includes more than music and scores; there are also planning documents, contracts, invoices and curricula vitae. The importance of such supporting materials has been highlighted by the National Archives of the UK in their Archiving the Arts project (The National Archives [UK] 2014). In some cases, these items will enable the curators to find contributors of specific materials. For example, the recording engineer who was paid to record a concert is likely to be identified by way of invoices, rather than by any information on the recorded materials in Tura’s collection. This is important as there is often copyright held in the recording of a musical work by the recording engineer and/or publisher, in addition to the rights of composers and performers (Australian Copyright Council 2012).

A performing archive

An important element of WANMA has been the close link of archival materials to actual performances that have taken place in Perth, a characteristic reflected in the nature of Tura’s collection used in the pilot study. This element will continue to mark part of the WANMA project into the future, by actually fuelling future growth. With the involvement of the ABC Classic FM team of producers, audio engineers and presenters in the forthcoming phase of the archive’s implementation, an ongoing commitment to recording and broadcasting new concerts of Western Australian works – new or newly rediscovered – feeding them back into the archive and incorporating linkages to related performers, composers, venues and other associated data is innovative in conception and serves as a model for future ‘living’ archives. In addition, Tura’s ongoing involvement will ensure public awareness of the project, through the organisation’s marketing and production support. In the past, ABC Classic FM’s Australian Music Unit has had something of an ad hoc approach to choosing Western Australian content to record for its broadcasts. Their partnership in this project will also provide curatorial advice as to the most valuable and relevant Western Australian materials to record, both as part of WANMA, and in their programming generally. As public awareness increases, and there are more communications around WANMA and its mission, so there are increased opportunities for holders of collections to learn about the project, and to use the archive and come forward, thus expanding the content in WANMA (Marres 2011).

Another aspect of community involvement WANMA plans to explore is crowdsourcing. Unlike the National Library of Australia’s (NLA) spectacularly successful newspaper correction program (the Australian Newspapers Digitisation Program), for WANMA this would likely focus more on the inclusion, rather than correction, of materials. This could include the addition of links to photographs, posters, flyers, newspaper and magazine reviews, ‘bootleg’ recordings and other ephemera relating to a performance of a particular work in the archive. It could also be an extremely valuable aid to identification of personnel in materials where this is unknown, through the use of techniques like the ‘tagging’ technology available to social media. The SLWA has successfully implemented a pilot project of a similar nature with ‘Storylines’, a central access point for digitised heritage collections relating to Aboriginal history in WA.2 The project uses the Ara Irititja software, a purpose-built platform developed in South Australia for the project of the same name, which allows the tagging and linking of a variety of materials including video and audio, as well as public uploading. ‘Storylines’ will be consulted as a model for future crowdsourcing of materials once the curation of Tura’s pilot collection has been finalised and entered into the catalogue.

Digitisation and digital preservation

Digitisation for preservation and digital preservation are closely related, ‘but the underlying standards, processes, technologies, costs, and organisational challenges are quite distinct’ (Conway 2010). Digitisation (whether for preservation or access purposes) implies that the original material is in a non-digital form, while digital preservation is the act of preserving materials that were created digitally – these may ultimately include digitised materials, but it is the born-digital content that presents the greater challenges, including interactive and multimedia works.

This project will initially produce digitised content from analogue source materials, with outputs of digital content in formats suitable for both online access and for preservation. Looking ahead, WANMA seeks to work with the community of Western Australian composers and performers to develop ways for their digital works to be taken into the collection and for preservation activities to commence early in the lifecycle of the material. This reflects recent changes to the legal transfer times (that is, the time after which material deemed to have archival value must be transferred to an archive) for archival material in government, including in Australia in 2011 (Commonwealth of Australia 1983), and brings the archival material closer to the concept of the ‘living archive’. It acknowledges the Australian concept of Records Continuum Theory (McKemmish 2001) in information management. Records Continuum Theory suggests that records are simultaneously contemporary and historical from the moment they are created: ‘By definition they are frozen in time, fixed in a documentary form and linked to their context of creation. They are thus time and space bound, perpetually connected to events in the past. Yet they are also disembedded, carried forward into new circumstances where they [are] re-presented and used’ (John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library, 2004). This will also bring otherwise fragile digital materials into a managed environment that provides for their long-term sustainability and access, without blocking but in fact further encouraging their re-use in the current time, and linking materials to a wide cultural heritage while they are still contemporary. This future work will develop a unique collection and portal to a history as it is created.

Early communications of the archive

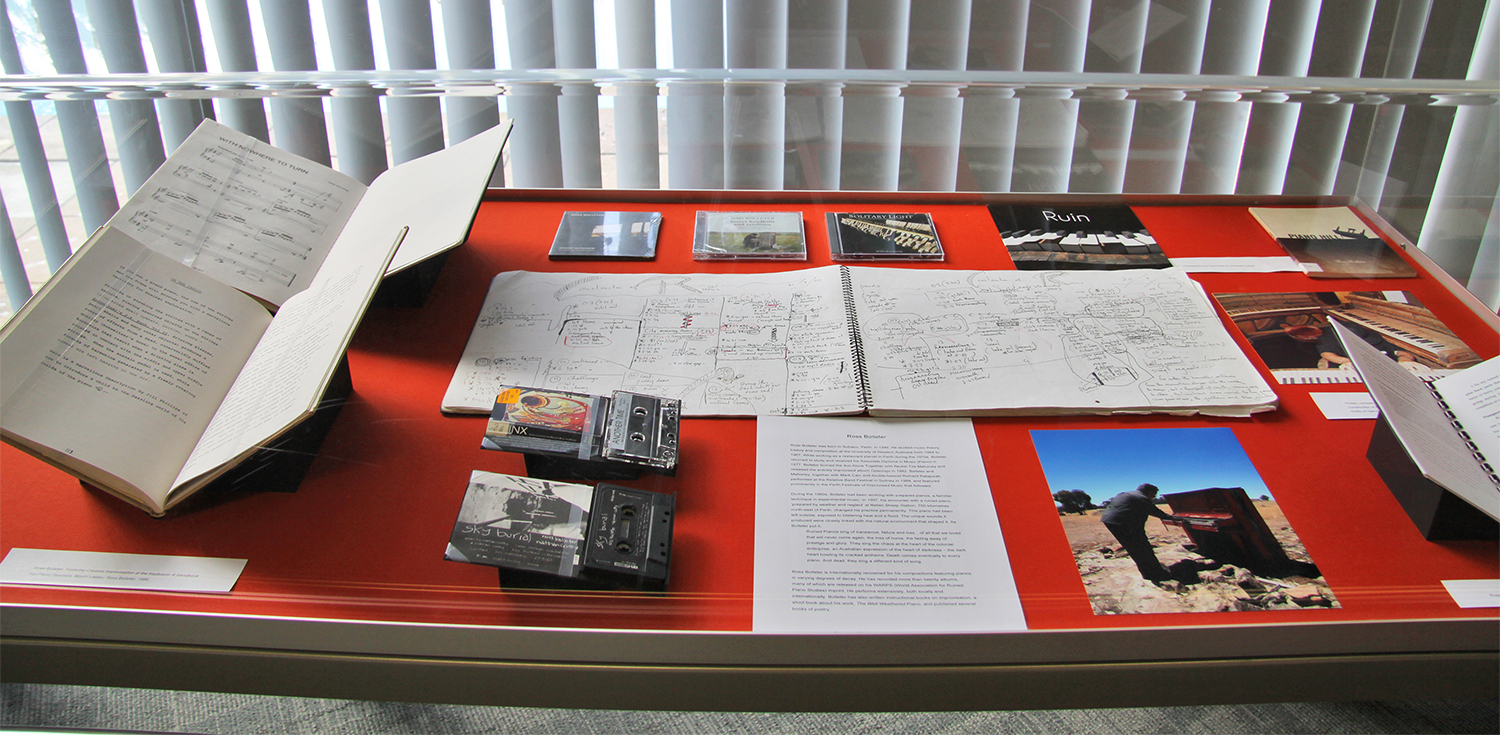

One of the earliest WANMA ‘communications’ was the staging of a small exhibition at the SLWA to coincide with the Totally Huge New Music Festival, which also incorporated the International Computer Music Conference, in August 2013 (see Figure 9.3). Lisa MacKinney had recently commenced a temporary role as project officer for WANMA, and one of the early tasks required was determining what materials in the State Library’s collection might qualify for inclusion in digital form as part of WANMA. Posters of historical interest, some of which were uncatalogued, were located in the library. We asked a number of local composers to lend us material and they were positive about their possible participation and thought it a worthwhile contribution. As word spread, other offers were forthcoming, including a mid-1990s computer with music-composing software that we were able to have running as part of the exhibition. The variety of materials presented – such as computer software programs on floppy disc, diaries, posters, cassettes and a range of audio and video formats – point to the upcoming challenges of digitising new music practices and the ephemera surrounding them. This is not a new phenomenon, as evidenced by Rothenberg’s observation in 1995 that ‘digital information lasts forever – or five years, whichever comes first’ (Rothenberg 1995); however, the project acknowledges this, and seeks not only to digitise materials in analogue format, but also to develop early-intervention digital preservation practices, such as the movement of digital materials from their creation format into a format likely to survive more than one generation of computing technology, for born-digital, interactive materials. These may be in formats such as Adobe Flash or MaxMSP code, which form a large part of the contemporary music landscape today, but, based on the experience of previous popular software formats such as Macromedia Director, are unlikely to be able to still be read in as little as 20 years’ time.

Figure 9.3 Some items from the Western Australian New Music Archive on display at the State Library of Western Australia during the International Computer Music Conference in August 2013. Photograph by Dana Tonello-Scott.

In acknowledging the differences between digitisation and digital preservation, we are hopeful that the composers who lent us material might agree in the future to allow it to be preserved for inclusion in the digital archive. In this manner, the WANMA exhibition was an important investment in the future of the archive, as well as valuable promotion for it. It is also hoped, in later stages of the project, that composers and performers will contribute their interactive works as they are being developed, potentially allowing a better preservation outcome for these materials. Before we can approach composers and performers to contribute, we will need to be confident that we have a full collection policy as well as copyright and contractual clearances in place.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation is an important partner for WANMA as the national flagship for the kind of music WANMA represents. As the area of the ABC most closely aligned with the project, ABC Classic FM’s Australian Music Unit will also be making its own archive of Western Australian recordings (which are currently not publically accessible) available to WANMA for digitisation and inclusion in the archive though a connection with their Classic Amp/Rewind project – an example of some of their work is seen in Figure 9.4. In this way, WANMA will access ABC material while supporting the ABC’s goal of getting more archival content recorded and available online, as well as increasing Western Australian performance content for their broadcasts.

Figure 9.4 A screenshot from the ABC Classic FM ‘Rewind’ webage for a work by Western Australian composer David Pye, performed by Western Australian artists, created by the Australian Music Unit at ABC Classic FM.

Intellectual property and ownership

The collection and long-term preservation of digital content poses challenges to formal intellectual property agreements. Original hardcopy materials will not be gathered by the project; rather, the database will point to their location and availability. The integration of an intellectual property framework within the archive to manage the complex rights inherent in musical works and related materials is a vital part of the research, as it is crucial to achieve an appropriate balance between copyright owners, the music community and WANMA users. This is a topic of ongoing debate in legal and policy circles, and our research also contributes to debates around copyright, copyleft (Free Software Foundation 2014), and Creative Commons approaches to artworks.3 The purpose of an archive, its subject matter, the manner in which it will acquire copies, as well as who will have access to the archive, from where, and under what conditions, all come with copyright implications that are critical to determine. We are currently in the process of engaging a digital copyright consultant to guide us through these complex processes, particularly in light of changes to Australia’s copyright laws (Commonwealth of Australia 2006) that make some special provisions for libraries and collecting institutions, and the recent inquiry into further proposed changes to the Act (Senator the Hon. George Brandis QC 2014).

One response to these challenges will be the use of high-speed scalable storage and network infrastructure that can support streaming video and sound so that materials are experienced direct from the archive, rather than requiring downloading; they will thus meet exemptions made to the Australian Copyright Act in 2006 for the storage of temporary copies in computer memory. But these issues are further complicated for WANMA by the fact that, although the archive will be accessible through the SLWA’s catalogue and website, only copies of hard-copy materials will be in the library collection. The copyright clearance for and ownership of such materials has been an ongoing and delicate process of negotiation with the library that has required an understanding of other collections of digital materials, such as photographs and the oral history recordings made for the Oral History Record Rescue project. The digital copies that make up WANMA will belong to the library and reside digitally in its Heritage Collection even if the original ‘hard copy’ resides elsewhere. This is enabled through a process known as the ‘deed of gift’, an agreement entered into by both the SLWA and the donor. The ‘deed of gift’ arrangement enables WANMA and the SLWA to provide digital access copies for research purposes. In this way, the WANMA materials reside in the SLWA, enabling the preservation processes already in place in the library to be extended to WANMA materials.

As the WANMA materials will appear in the SLWA catalogue, they will in turn feed into the NLA’s TROVE catalogue. They are also searchable in a unique web portal for WANMA, through the use of a specially constructed application programming interface (API). In addition, the WANMA portal will connect directly to other partners, such as Tura, the ABC, as well as to the public through the development of other APIs. The benefit of a standalone interface in addition to the SLWA catalogue is that it enables WANMA to have its own unique presence and identification, and to operate as a place where all WANMA activities, such as new additions, recordings and performances, can be promoted and shared.

The pilot study discovered that the primary users of WANMA would be artists and musicology and intermedia researchers, and that there would be accessibility benefits flowing on to a global and general audience. We plan to make WANMA an open access archive, as is the current full SLWA catalogue, implementing similar deeds and contracts to facilitate this. More user-experience research will be undertaken in order to determine more precisely the manner in which access to the archive will operate, and what capabilities the software should include. But it was also determined that this flow-on would only be possible with knowledge of international bibliographic standards and a requirement that WANMA be interoperable with Australia’s national bibliographic infrastructure. We have begun discussions with the NLA, ABC Classic FM and, in an advisory capacity, the Australian Music Centre, who recently digitised their extensive collection of scores and recordings, to discuss ways to enable this.

Conclusion

WANMA addresses manifest gaps in national and international collections of new music. As these have been developed over the years they have failed to include Western Australian new music at the depth and breadth required to understand and investigate the many interconnections between people, place, artworks and shared experiences.

The archive is more than a historical repository of new music and its supportive and peripheral elements, however. It is a curated collection with the capacity to influence the present and the future through a commitment to performative research. As a result of this aspect of the project, new compositions and recovered artworks will be produced by research partner ABC Classic FM, informing the future direction of new music while at the same time building WANMA’s collection.

Communication is at the heart of this project, which we hope will form a core for the existence of a community of practice, and for the continuation and development of such a community over time. Relevant communication extends beyond the spoken and the written to the experiential – shared non-verbal communication arising out of artistic engagement between new music audience members and participants, composers and musicians. This project has the further benefit of making Western Australian new music visible and according it appropriate importance, creating a dynamic which will attract the interest of people as yet unknown who will be moved to engage with the archive and, possibly, donate materials as yet unidentified. Although WANMA is in its early days and is not yet publicly accessible, it has already raised a range of issues around copyright and definitions of relevance. New music is a complex and evolving artform and WANMA recognises and celebrates this in its conception and ongoing construction.

Works cited

Archives Act 1983 (Cth).

Australian Copyright Council (2014). Music and Copyright Information Sheet G012v14. http://tiny.cc/acc-g012v14.

Australian Law Reform Commission (2014). Copyright and the Digital Economy (Final Report). Sydney: Commonwealth of Australia. http://alrc.gov.au/publications/copyright-report-122.

Australian Music Centre (2015). ‘Artist representation.’ http://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/about/representation.

Bettiol, Marco and Silvia Rita Sedita (2011). ‘The role of community of practice in developing creative industry projects.’ International Journal of Project Management, 29(4): 468–79.

Conway, Paul (2010). ‘Preservation in the age of Google: Digitization, digital preservation and the dilemmas.’ Library Quarterly 80(1): 61–79.

Copyright Amendment Act 2006 (Cth).

Creative Commons (2015). ‘About the licenses.’ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/.

Free Software Foundation (2015). ‘What is Copyleft?’ http://www.gnu.org/copyleft.

Haunton, Melinda (2014). ‘Talking “Archiving the Arts”’. Blog. The National Archives. http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/talking-archiving-arts.

John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library (2004). ‘Australian contributions to recordkeeping.’ Understanding Society Through Its Records. http://john.curtin.edu.au/society/australia.

McKemmish, Sue (2001). ‘Placing records continuum theory and practice.’ Archival Science 1(4): 333–59.

Marres, Noortje (2011). ‘The costs of public involvement: Everyday devices of carbon accounting and the materialization of participation.’ Economy and Society 40(4): 510–33.

Mitchell, Lynne (1998). ‘ABC attitude to Australian and contemporary music is absolutely pathetic.’ Music Maker 6(5): 9.

National Library of Australia (2015). ‘Australian Newspaper Digitisation Program.’ http://www.nla.gov.au/content/newspaper-digitisation-program.

Pye, David, composer and creative director (2004). Karakamia. Audio. Perth: Australian Broadcasting Commission. http://tiny.cc/2004-pye-karakamia.

Rothenberg, Jeff (1995). ‘Ensuring the longevity of digital documents.’ Scientific American 272(1): 42–47.

State Library of Western Australia (2013a). ‘Collection profile for music.’ http://tiny.cc/2013-slwa-music.

State Library of Western Australia (2013b). ‘Oral histories.’ http://www.slwa.wa.gov.au/find/wa_collections/oral_history.

State Library of Western Australia (2014). ‘Collecting profile – J. S. Battye Library of West Australian History.’ http://tiny.cc/2014-slwa-battye.

State Library of Western Australia (2015). ‘Storylines.’ http://www.slwa.wa.gov.au/for/indigenous_australians/storylines.

White, Terry-Ann (1991). ‘Testing the tensions.’ Fremantle Arts Review 6(4): 8–9.

1 Australian Music Centre. Artist Representation. http://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/about/representation.

2 State Library of Western Australia. Storylines. http://www.slwa.wa.gov.au/for/indigenous_australians/storylines.

3 Creative Commons. ‘About the Licenses’. http://creativecommons.org/licenses.