7

Animal-using industry

In this chapter we examine the relationship between animal welfare and protection policy and organisations that use animals – directly or indirectly – largely for commercial purposes. Unlike the animal protection organisations (APOs) discussed in Chapter 6, these organisations fit clearly into the interest-group model introduced at the start of that chapter. They are predominantly formally constituted organisations, largely designed to represent the interests of business and professionals externally, with the primary objective of producing an environment favourable to the production of ‘private goods’. Because of this, animal-using industry organisations (AIOs) may be seen as more homogeneous than APOs. However, this is not necessarily the case. While their profit-making objective is straightforward, this group of organisations is complex compared with other sectors of the economy. Partially, this is an artefact of the convergence of two policy concerns – animal welfare and economic protection – but it also relates to the extremely long history of some AIOs and variations in the industries that they represent.

This chapter begins by discussing the structure of AIOs as a collective group, before examining how animal welfare policy is made. It argues that policy-making is predominantly undertaken within the comparatively closed and close policy networks of animal-using industries in a regularised set of relationships with government organisations. Importantly, while animal welfare has increased in significance for AIOs over the last 40 years, the issue remains a comparatively minor – if increasing – problem from the perspective of AIO executives. They face a ‘grassfire war’ in which slow, consistent policy processes tend to be disrupted by APOs in a recurrent but unpredictable manner. Because of this, the later part of the chapter discusses how AIOs have, individually and collectively, responded to the challenge of APOs, and the pressures that this demonstrates within this community.

Who are they?

In looking at animal welfare, in Chapter 3 we identified the wide range of contexts in which humans have instrumental and commercial relations with animals. Thus, in describing AIOs, our net is wide, incorporating industries and quasi-industries1 that use animals as commodities; transform animals into other products such as food and clothing; transport and retail animals and animal products; and employ animals as labour and as research and teaching tools. As noted, there are about 500 organisations theoretically involved in the animal protection and welfare domain in Australia. Of this, about half are the APOs and related organisations discussed in Chapter 6. The remaining 250 or so are organisations involved in the use of animals for instrumental purposes.

This necessitates the observation that, as with Australian APOs, the large number is potentially misleading. It may give rise to the image of an army of lobbyists and organisations active in the policy space at any one time, but this is not the case: as with APOs, while some organisations are purely advocacy groups, many others have little or no role in direct political advocacy (Halpin 2005a). Instead, they may be focused on the provision of services within their membership group or sector, or engaged in some other type of activity, such as marketing. Some are ‘potential’ actors – that is, groups that are rarely called upon for policy expertise, but that may take action when called upon or in response to a threat or challenge; Schudson 1998, 310–1). Others play a policy role that is outside the remit of the state, such as in the regulation of pure-breed standards, or are only marginally ‘industrial’.

With this in mind, it is possible to divide Australian AIOs into eight general types:

- Farmers’ organisations: Australia’s agricultural history produced a range of organisations representing farmers and farming. Some of these developed as generalist bodies, others from specific sectors within agriculture. Over time these have tended to coalesce into a set of organisations in each state and territory. State Farming Organisations (SFOs) generally have direct, individual membership2 and long-term, very stable relations with political elites and public servants (Zhou 2013, 56–7). From the late 1970s, these organisations were joined by a national body, the National Farmers’ Federation (NFF) of which most but not all SFOs are organisational members.

- Commodity councils or groups: In addition to organisations representing farmers, the historical pattern of agricultural assistance led to the development of commodity councils. Commodity councils represent the interests of particular agricultural sectors, such as the beef, chicken meat, eggs, goat, pork and dairy primary production sectors, but also some secondary industries such as meat processing and lot feeding. Because of the history of localised industry support, some commodity councils in established sectors are federated (dairying, for example, has a national body as well as state-based representative groups), whereas newer or more marginal sectors may have only a few or one commodity council representing them. Commodity councils have varying relationships with the NFF and SFOs, with some ‘integrated’ into farming organisations and others independent.

- Service organisations: Agriculture’s specific policy history in Australia has also produced a range of service organisations (sometimes called marketing organisations, operational organisations, or rural research and development corporations). While some of these organisations rely on volunteers, most are supported by compulsory industry levies to fund services such as research.3 Similarly, most are owned collectively by their industry and have enabling legislation that spells out their objectives and gives them levy revenue.4 These organisations tend to focus on service provision, but their research role can be significant in considerations of welfare and they have a strong relationship with the more advocacy-focused commodity councils they support. This does not, however, mean that they are ‘creatures’ of specific commodity councils.5 The role of legislation in creating and prescribing their activities is a constraint on their freedom of action, and some have service relationships with multiple commodity councils (Meat and Livestock Australia, for example, services the goat, cattle, sheep and feed lot commodity councils), which can constrain their activities where there is a potential for conflict between commodity councils.6

- Industry sector organisations: Outside of primary production, any industry with significant enough revenue is also represented by one or more industry organisations. These trade organisations have a range of structures, from federated national peak bodies to membership-based associations. They also range from broad sectoral organisations (e.g. the Pet Industry Association of Australia) to bodies representing specific parts of an industry supply chain. While commodity councils are essentially industry sector organisations, in that other areas of primary production are ‘arbitrarily’ excluded from one category and put into another (e.g. the Australian Association of Dog Breeders), there is a real cultural difference between commodity councils and other organisations, a difference that can be attributed to Australia’s history of farming practice, the valorisation of some forms of animal rearing over others, and the more formal legislative integration of commodity councils into the state.

- Individual actors: While many industry actors choose to rely on their representative organisations, some are large enough, or consider their interests unique enough, to engage directly as policy actors. Previously cited examples included major international fast-food companies and domestic grocery chains, but others may include major agribusiness corporations (e.g. Elders).

- Industry governing bodies: Another set of organisations comprises those that oversee the conduct of their industry as governing bodies. Of these, many have a statutory basis, making them official regulators with legislative backing. The most significant examples of these are the national and state-based horse and dog racing bodies. Established from the 1990s onwards, these organisations were split from horse racing clubs so as to separate administration from regulation. Acting under their enabling legislation, they maintain and police the Australian Rules of Racing (by agreement) and their local rules (by law), which focus on the integrity of the gambling system, human safety and animal welfare. A similar organisation – that is, one that regulates its own competition, with rules that include animal protection standards – is the Australian Professional Rodeo Association (APRA). Unlike the racing organisations, however, APRA has not achieved a statutory basis (which it would prefer to have, in order to rationalise the rodeo industry; interview: S. Bradshaw, 5 May 2014).

- Breed societies: A more eclectic group of organisations consists of the various breed societies and regulating bodies. Focused either on specific species or subspecies (such as pure-breed animals) these organisations include fancier groups, breed standards and stud registering bodies, animal showing and competition groups, and others. Of all the organisational types, this group is most ambiguous with regards to its ‘industrial’ status, and commercial activities included in this area may be minor or secondary to the generation of individual utility. They can, however, play a significant role in animal protection issues through their breed certification requirements.7

- Professional associations: The final set of organisations comprises those bodies that represent professionals who work with animals. The largest and most significant of these is the Australian Veterinarians Association, which includes state and local branches and an internal set of interest groups, but a range of groups exists in this category. These organisations have split interests: they aim to promote their profession, regulate entry and professional standards, and police and promote their members’ duty of care or professional ethics in a way that makes professional associations different from unions.

This organisational breakdown, while lacking the sharpness of true typology, provides a good overview of the diversity of relevant actors who are, have been, or could be engaged with the domain. As with APOs, these organisations are diverse and, as with the Animal Welfare Leagues (AWLs) and RSPCAs, some have enabling legislation that governs some of their functions and provides a direct interface with the public sector. Where they differ is in their considerable financial and human resources, their presence throughout Australia, and their long-standing relationships with policy-makers. This means that the state (whether regularly or occasionally) has an interest in engaging with these groups to advance its policy objectives. A map of the AIOs and their relationship with state policy-makers is provided in Appendix D.

Industrial relationships surrounding protection and welfare

The diverse range of organisations across the domain mitigates against a coherent and consistent set of organisational responses to issues. Significant institutional actors in the policy network are commodity councils and industry sector organisations dealing with specific issues seen as unique to their sector. The main interlocutors of these organisations are state governments and major APOs. There is limited horizontal interaction across industry. What horizontal interaction exists tends to focus on those organisations most similar in structural, cultural and historical terms. This results in a de facto fire-breaking, for example, of agricultural organisations from those engaged in companion-animal policy debates.

The significance of state agencies as primary sites of policy development and consultation is an important part of this story, reducing the role of national peak representative bodies like the NFF as potential co-ordinating bridges, but also defining the policy paradigm in which organisational participation is interpreted and anticipated. Further, while this is exacerbated by the abolition of bridging structures like the Australian Animal Welfare Strategy (AAWS) (Chapter 8), even these structures tended to include selective industry representation within their specific code development processes, ‘siloing’ policy-making to a large extent. Because of this, commodity councils tended to see the AAWS process as comparatively clear, while cross-sectoral industry representatives reported the process as opaque.

Within some communities of AIOs, there has been discussion of less disaggregated ways to engage in industry advocacy. In 2015, the NFF and some SFOs engaged in a national strategic conversation about the structure of agricultural advocacy in Australia overall.8 This included calls to further consolidate the relationship between farmers as individuals, commodity councils and national representative structures. The argument underpinning this proposal was that, while individual organisations may be effective, the somewhat ad hoc development of the representative system undermined efficiency and effectiveness (Bettles 2014). This is a broader political project, which would involve a significant reduction in organisational overlap but also the resolution of explicit and underlying tensions between competing organisations and views about agricultural policy.9 Thus the scale of this proposed change cannot be underestimated.

Specific attempts have been made to develop formal structures to address cross-sector animal protection activism. Many of these have not been successful, or have not been sustained. For example, the NFF established the short-lived Livestock Industry Group in 1983 to provide a determinant, holistic, cross-sector working group on animal welfare activism (Graham 1983). At the state and commodity council level, the value of a co-ordinating role for animal protection issues is recognised by smaller AIOs. Peak organisations can be referred issues that cross either jurisdictional or sectoral boundaries. In this view, issues can be identified locally, then ‘filtered up’ to peak structures (interview: CEO, Queensland Farmers’ Federation, 16 April 2013). This can only occur, however, where industry segments maintain a strategic and longer-term ‘horizon view of things’ (interview: general manager [policy], NFF, 14 November 2014).

This has not always occurred. Even when issues have been identified well in advance, some commodity councils are loath to intrude on others’ remit. This can be to their own detriment. In the 2011 management of live exports, excessive deference to other commodity councils’ sphere of control led the Cattle Council of Australia (CCA) to:

deal with that in a reactive way, unfortunately, and make such a mess with things we’d really have to get boots and all involved very quickly . . . Now, the live exporters have their own big council, Australian Live Export Council. And in a normal set of circumstances you left them to drive those sorts of issue. It’s their bailiwick. That’s where we’ve got these nice little boxes – but this really genuinely is a crossover issue, [it] crosses over to the producers and the live exporters. So, through [peak red-meat commodity council] the Red Meat Advisory Council, a lot of debate [went] on, and it seemed that the Cattle Council’s constituents’ interest [was] to get this sorted because it affects our members that rely on live-export trade for income. Some areas, there’s no other choice. (Interview: J. Toohey, 4 July 2014)

Thus, effective co-ordination of animal welfare and protection policy appears to have eluded the sector. The NFF in 2013 admitted to failing in its attempts to address animal protection issues in a unified way, conceding ‘a history of sectoral response to animal welfare issues’ (Sefton & Associates 2013, 43).

Why the sectoral response?

In addition to structural siloisation, a number of factors contribute to this lack of co-ordination between industry actors.

The first barrier to effective collaboration is the disparate state of environmental awareness amongst the public, especially regarding animal protection issues. Commodity councils from the chicken and pork sectors, for example, report occasional use of systematic surveying (interview: a representative of the chicken industry, 31 January 2014) and focus groups (interview: A. Spencer, 23 June 2014) on this topic.10 Others have less structured environmental scanning practices (interview: E. Forbes, 9 April 2014). This may be problematic, as public opinion can be fast-moving. But it also stems from the difficulty of establishing a truly informative set of measures in an area where industry considers public opinion to be unstructured and volatile (interview: J. Toohey, 4 July 2014; E. Forbes, 9 April 2014). Where high-welfare products exist, retailers (interview: a representative of the retail industry, 22 April 2014) and highly integrated industries (particularly eggs) are best placed to measure the conversion rate of concern into high-welfare product options, but the movement of this type of information across the sector can be limited by the desire of retailers to ensure they have better intelligence than their suppliers.

Second, relationships can be very pragmatic and groups may not support related enterprises where both welfare standards and the economic value of the practice are low. A good example of this is jumps (hurdle and steeple) racing in South Australia. With low levels of participation (O’Sullivan 2015a) and a comparatively high injury rate to horses (Ruse et al. 2015),11 the South Australian Jockey Club has pushed for the sport to be wound up by the state government (ABC News 2015). While this may be thought to reflect the susceptibility of marginal enterprises with ‘poor’ welfare records to legislative bans, this is not strictly the case.12 In this example the opportunity cost of using racing facilities for jumps compares unfavourably to thoroughbred racing, making this a pragmatic decision by the jockey club to push out the last of the jumps competitors (in comparison, a temporary suspension in Victoria in 2010 was lifted by Racing Victoria; McManus et al. 2012). This argument about industry size and susceptibility to regulation is born out in a counter example: the comparative unwillingness of political elites to entertain blanket prohibitions on exotic circuses (Browne 2012). In the latter case, neither opportunity cost nor direct competition with zoos exists.

Third, breakages between different economic sectors produce barriers to industrial collaboration. Some of these are simply related to the social and/or other distance between industries that might otherwise have strong grounds for collaboration. Wool producers and laboratory researchers, for example, face similar campaigns (international secondary boycotts), by similar APOs (PETA [USA]), over similar issues (inherent practices in their use of animals). Other breakages are related to conflicting stakeholder interests. This can produce conflict between industrial actors over what appear to be symbolic slights but are in fact more significant in nature.

An example of this is the 2013 Coles–Animals Australia ‘Make it possible’ campaign. In this in-store promotion, Coles sold Animals Australia–branded shopping bags, in line with the positioning of Coles as a supplier of certified high-welfare products (free-range, RSPCA-approved and grass-fed). The promotion, similar in structure to the retailer’s cross-promotion with Landcare Australia, was not received well by the agricultural sector. Farmers threatened to boycott Coles and its parent company, and to refuse to supply them. In this case Coles significantly misjudged the sensitivity of farming communities towards Animals Australia (Clark 2013), and the role of downstream industries in pushing for increased animal welfare standards that primary producers see as antithetical to their profitability. But this shows how these two groups have very different sets of stakeholder relationships that drive their commercial concerns. Importantly, while the NFF was successful in getting Coles to withdraw from the promotion,13 the channelling of displeasure through the federation (FarmOnline 2013) illustrates the weakness of suppliers relative to retailers. Using their representative body to engage with Coles presented fewer long-term risks in confronting one of the two major grocery retailers in Australia, one with massive market power over individual suppliers.

Finally, as this demonstrates, mediating structures or organisations are rarely able to broker agreements between APOs and AIOs. The ongoing dominance of issue management by individual commodity councils means that organisations with a history of dealing with cross-cutting and social issues are not seen as natural solutions to welfare issues. This has been observed nationally, but also among SFOs:

I think that’s one of the challenges for the policy environment, and my observation of industry bodies and how they’ll react to it, is there isn’t any real proactive discussion going on with . . . those people who believe that animal welfare standards are too low . . . [The policy domain] still has very strong camps and polarised debates . . . and therefore that’s a very difficult environment for someone like our organisation to sort of try and put our hand up and say, ‘We’d like to broker a better relationship here,’ as we would do in environmental issues. (Interview: CEO, QFF, 16 April 2013)

Here the disconnect between APOs and the environmental movement is significant: the integration of environmental pressure groups into negotiated processes in other areas of policy-making has not been mirrored in the animal domain.

Animal welfare: significance and meaning

The comparatively scattered response to animal welfare and protection policy reflects a comparatively low salience of the issue to AIOs in Australia over many years. This, however, has been changing. Respondents report that the importance of these issues for AIOs has been increasing steadily in recent years, across a range of organisations (interview: general manager [policy], NFF, 14 November 2014). For the dairy industry, animal welfare has become a far more salient issue in the last decade and is now a ‘top five’ issue (interview: W. Judd, 19 April 2013), up from a mid-level issue just five years ago (Queensland Dairyfarmers’ Organisation 2009). This shift has coincided with Voiceless focusing on dairy welfare as a neglected ecological niche among APOs. Similar, if less dramatic, changes in significance were reported by the other commodity councils and industry organisations interviewed for this volume.

Responses to this shift have also included the institutionalisation of new structures designed specifically to embed welfare policy development in organisational activity. Racing includes regular board items on welfare (interview: E. Forbes, 9 April 2014). The Cattle Council of Australia, in establishing a subcommittee system in recent years, formed an Animal Health subcommittee with explicit remit to work on animal protection issues. The NFF has set up a taskforce to consider welfare issues.14 In 2010 the Australian Professional Rodeo Association appointed an animal welfare representative to drive policy development and training. For many respondents, this reflected a desire to become ‘proactive’ on the issue:

My attitude has always been that . . . if we see our own issues in association or as a federation, we need to be addressing them. Because we say, ‘We love the animals, and we look after animals’, if there’s anything that we see because we’re the experts, we should be addressing it ourselves and not waiting for someone else to address it for us. It must be proactive and primarily for the benefit of the animals. (Interview: S. Bradshaw, 5 May 2014)

Proactivity here includes an acceptance that APOs have been driving welfare debates during the last decade.

Thus, we need to ask the question: if AIOs see animal welfare as increasingly important – internally and externally – how do they perceive the issue? That is, following on from our discussion of what cruelty means for the Australian public in Chapter 3, what does welfare mean for those involved in animal industry?

The first meaning was introduced in our previous consideration of ‘husbandry’ and animal-rearing. When interviewed, many industry representatives suggested that there is a direct relationship between effective industry practice and good welfare. Whether it involves primary production or entertainment, this argument can be summarised as: it is in our industrial or commercial interest to maintain the highest standards, because otherwise productivity (however it is measured) will decline. This notion that ‘good husbandry equals good welfare’ allows their industrial or commercial productivity to act as a measure of good animal protection practices.

As we will see below, in this model the ideal level of welfare is reached just before the point at which productivity begins to decline. In this formulation, animal welfare depends on an economic trade-off between competing interests and their ‘utility’. These interests include:

- the value to the producer (measured in productivity or profit) in working their animals as ‘hard’ as possible

- the wellbeing of the animals involved (their welfare, however measured, but excluding any intrinsic value to the animals themselves)

- the ‘public good’ of having an animal industry that is ‘not cruel’.

This view of welfare considers it as a series of economic trade-offs.

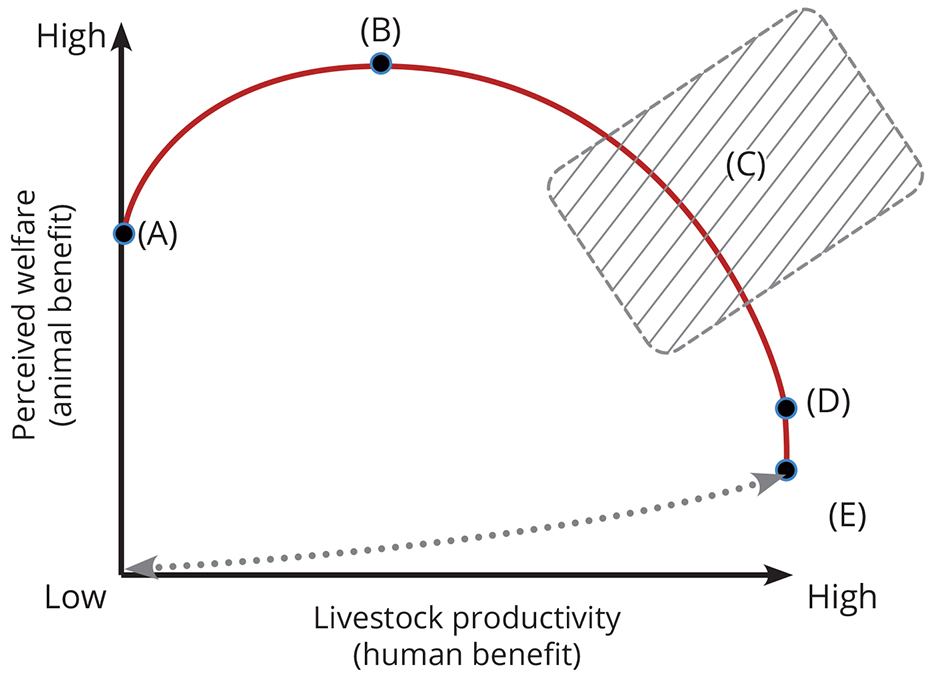

McInerney (2004) argues that, contrary to the ‘good husbandry’ argument, welfare improvement in commercial settings is non-linear. As we can see in Figure 7.1, human intervention produces a more positive relationship than that which animals might experience ‘in the wild’ (point A, at which there is no human intervention in the animal’s health), rising to a point of maximal welfare (B, at which there is a positive intervention). However, for further productivity to be gained from animals beyond this point, society must accept declining levels of animal welfare (negative utility for the animal, with the possibility of negative externality to society if they ‘care’). In extremis, productivity can reach a point of negative value (point E), where both productivity and welfare rapidly decline (for example, working an animal past exhaustion; this point is indicated in the figure by the dotted arrow). In this type of economic analysis, welfare debates exist in the shaded area of zone C, where productivity and welfare are economic trade-offs necessitating a political rather than technical debate. The debate is political in nature because it is about the authoritative allocation of utility to different groups due to the increased costs of production.

Figure 7.1. McInerney’s ‘conflicts between animal welfare and productivity’ model (adapted). (A) ‘natural’ welfare/non-intervention, (B) ‘maximal welfare’, (C) ‘desired/appropriate’ welfare range, (D) ‘minimal welfare’ and (E) system collapse. Simplified and annotated from McInerney (2004, 18).

As an abstraction this model overplays similarities between sectors. There is no simple ‘unit of welfare’ comparable to monetary costs and profits, and so welfare is measured in different ways for different types of animals and in different contexts. The value of this model lies in its demonstration of two factors. First, and most simply, the model shows how economic value is privileged in the shaping of welfare policies. Thus, in a discussion of hot-iron cattle branding – an activity largely abandoned in most of Australia because it can be replaced with other, less painful stock management and identification systems – the welfare calculus follows this exact formulation:

You go to any property, particularly the big ones up north where they’ve got hundreds of thousands head of cattle – whatever we bring in, they need to maintain viability . . . They have welfare in mind . . . it’s in their interest to look after the welfare of the animals or else they’ll not make as much money as they would otherwise. But at the moment, particularly with the drought and bits and pieces, they are really doing it tough and so it’s a balancing act for them. (Interview: J. Toohey, 4 July 2014)

Second, it shows that signals about value can be complex. Wells et al. (2010; 2011) researched wool producers’ decisions about abandoning mulesing following the PETA (USA) campaign, during the period in which the industry had committed to phase out the practice by 2010. In their research, they found that decision-making included:

- a recognition by producers that they could ignore the voluntary commitment (non-compulsion)

- an assessment of the costs and practicality of alternative practices (generally high)

- an assessment of the comparative welfare impacts of mulesing versus breech (fly) strike in probabilistic terms (unfavourable to change)

- an assessment of the probability that consumer interest would translate into a demand for alternative products (low, given low levels of public understanding and therefore low willingness to pay for alternatives).15

In addition, Wells et al. identify that interaction with farmers who had already voluntarily phased out mulesing was significant in shaping the decisions of others to adopt above-minima welfare practices. The willingness of some producers to abandon the practice voluntarily demonstrates that decision-making using strict cost–benefit analysis is moderated by a range of factors associated with local norms and expectations, as well as the practical capacity for improved welfare.16 Additionally, the value of this model becomes less informative as we move away from strictly economically rational sectors.17

Overall, animal welfare policy and protection campaigns have become significant for industry, but are largely only seen through an economic lens. In addition, while producers in theory might be expected to have no preference about where they sit on the animal welfare curve provided any lost productivity can be recouped from their buyers, this does not appear to be the case. AIO constituents do not perceive a willingness by the public to accept higher retail costs in exchange for welfare gains. The NFF has reported that many primary producers see animal protection primarily as a threat to their major concern: profitability. Where activist campaigns move other AIOs to adopt standards that are enforced upstream, their limited market power relative to retailers does not always provide producers the opportunity to add value (Sefton & Associates 2013, 53).18 Utility, in this model, can be generated at a different point of the value chain, with cost being shifted to producers.

For some, activist campaigns represent more than simply a risk of increased production costs. These organisations are cognisant of the risk of reaching a ‘tipping point’. While the general community may have little interest in animal welfare, this lack of interest is sustained by a general sense of trust in industry. As the CEO of Australian Pork Limited observed, his consumers would switch from pork to another meat should they lose confidence in the industry’s ability to provide appropriate welfare:

They are not fickle about that switch, but they are definite about it . . . if they see a systemic problem with our industry, over time they will make that shift . . . They don’t change their mind quickly. But if they get piece[s] of evidence one after the other, they will make the shift. (Interview: A. Spencer, 23 June 2014)

This points to an additional concern in some sectors: that their members are not as motivated about animal protection – as a risk – as are sector leaders, making mobilisation and response less effective.

The Victorian Farmers’ Federation, for example, lists animal welfare as a primary threat to farming in its promotional materials (Victorian Farmers’ Federation 2014), and SFOs have referred to the need to counter activist campaigns when raising funds for industry advocacy. However, in 2014, the agricultural sector overall saw more basic economic issues as far more important than activist campaigns (see Table 7.1), although industries more recently targeted by activist campaigns reported higher levels of concern. This has implications for attempts to mobilise these constituents against activists, and reveals a perceived disconnect between profits (A), supply-chain power (B), and activist campaigns (C).

| Issue | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Profitability (A) | 45 |

| Costs / supermarket duopoly (B) | 33 |

| Production costs | 29 |

| Regulation | 22 |

| Drought | 11 |

| Minority groups and activities (C) | 10 |

| Labour shortages | 9 |

Table 7.1. Primary issues affecting farmers (respondents could select more than one); n = 1,002; annotated. Guthrie and Akindoyeni (2014).

The inside track: welfare as a policy routine

Having a largely passive membership on these issues, AIOs have been forced to pursue insider strategies to negotiate and manage policies involving the treatment of animals. Thus all major, and most minor, AIOs retain regular and enduring relationships with policy-makers and regulators, such as key public servants, enforcement personnel, and (depending on the stature of the industry) politicians. These relationships are exchange-based: industry organisations tend to offer information and program implementation capacity (they are large ‘delivery agencies’ of industry programs, directly or through their service organisations), in exchange for favoured access to key decision-makers. They may not always achieve their policy objectives, but AIOs always anticipate getting a ‘hearing’. As discussed above, these interactions are partitioned into various industry-segment silos, with these silos commonly reproduced in each jurisdiction where the industry has a significant basis of operations. Where policy is pushed up to the national level, SFOs, the NFF, and only the largest commodity councils tend to have enduring and regularised relationships with policy-makers.

To some extent this suits a close, closed policy-making style that tends to keep policy development out of the public eye, and, as Halpin (2005b, 145) has observed, often out of the gaze of parliaments, by keeping policy in the administrative space where possible. This is the source of a common belief that AIOs have ‘captured’ the public sector.

Capture or captives?

A popular explanation by many APOs for the perceived gap between public expectations about animal production in industrial contexts (Chapter 3) and industrial or regulatory practice is regulatory capture. Regulatory capture is one of a range of principal–agent problems in democratic practice where the complexity of the state, and the disproportionate power of some interests (commonly economic), subvert regulation, either to negate its effect (by declawing the regulator) or to provide advantages (for instance, by preventing market entry with high regulatory barriers in order to create a mono- or oligopoly; Croley 2008). This view is promoted by animal protectionists, as well as by scholars (Goodfellow 2012). A number of hypotheses are promoted:

- Following a political-economy analysis, economic interests are seen to receive favoured access to policy-makers, giving them greater influence to shape policy and/or to prevent issues from coming onto the political agenda.

- The operational closeness of regulators and industry creates shared cultural norms and distorts regulation.

- The inherent design of regulation, largely focused on state departmental inspector models, results in regulatory capture owing to the orientation of government departments towards ‘pro-growth’ economic objectives rather than public interest or animal welfare (this can be described as the ‘conflict of interest’ argument).

The latter is at the heart of calls for independent animal-welfare regulatory offices (see Chapter 8).

The question of capture is a complex one. Agricultural interests, in particular, have a strong historical and structural position relative to their state interlocutors for a variety of reasons. These include history and path dependency. The significance of the agricultural sector to the Australian economy previously provided the sector with direct political influence through rural constituencies. This was entrenched in a series of closed policy networks – ‘iron triangles’ – focused on specific production segments in the form of the various marketing bodies that focused on ensuring minimum prices for commodities before the 1970s. While the relative significance of agriculture to the overall economy declined after the Second World War, the sector’s interface with government – through state and Commonwealth agriculture departments – provides the sector with an enduring key ministry with whom it is engaged. Second, while rural population decline and urbanisation have increased the overall number of non-rural seats in parliament, rural seats have a tendency towards smaller population sizes. This leads rural interests to have higher numbers of MPs than a strict one-vote-one-value model would produce (Robinson 2003). Third, the sector has developed stable and enduring peak political structures, providing greater capacity for relationship building and maintenance with bureaucrats and political elites.

On the other hand, the past 50 years have seen the dramatic dismantling of the type of policy networks that were the most prone to capture: the marketing boards. What remains is a closeness between peak bodies and agricultural policy-makers, but not the interleaved relationships that once existed in each commodity area. This residual closeness can be mistaken for capture (Botterill 2005). In considering relationships with agricultural policy-makers, Marsh and Pannell (2000) identify how the adoption of neo-liberal economic policy has shifted the role of government agencies from service provision to client-driven approaches that are based on stricter cost-recovery models. Greater accounting for the bottom line requires a willingness of producer groups to pay for government services, and for state service providers to pay greater attention to the public interest in co-investment in services.

Further, the micro-economic reform agenda since the 1980s forces policy-makers to consider interests from across the economy. This gives the representatives of other economic interests, such as importers, wholesalers and retailers, a metaphorical ‘seat at the table’. Policy-makers may need to consider the wider implications of any support for industry through the lens of public interests and public goods, and/or to consider free-trade arguments. This is one reason why governments have yet to substantially respond to producers’ concerns about concentration at the retail end.

The wider implication is that agricultural interests have, through the disciplining effect of free markets and neo-liberalism, a significantly smaller array of policy options to draw upon, while at the same time having their policy representations channelled towards agriculture departments and rural political representatives. This is evidence of a declining structural power-base in policy networks, if not at the level of regularised interactions with bureaucrats. These enduring relationships are strongest at the state and territory level, where regionalised programs and activities are commonly generated and co-managed, but their influence has declined over the last decade. The non-prioritisation of ‘producers’ (including primary industries and manufacturing) in post-Keynesian economic thought has given transporters, wholesalers and retailers greater influence, particularly when it comes to competition policy at the national level. Overall, argue Cockfield and Botterill (2013), the policy-making process relevant to rural and regional industry tends to be one of long periods of incrementalism based on an overarching policy model (first protectionism, then adjustment, now global free markets). Within this framework, agricultural interests have a favoured seat at the policy-making table, but only to the extent to which this input fits into the dominant policy model of the day.

The implication for policy-making around animal welfare and protection issues is clear. The bias towards incrementalism is a strong one and provides stability for producers in dealing with regulatory change. Agricultural interests will retain a strong capacity to influence the design and implementation of regulation given their close relationships with policy-makers in this area. However, this tight control is limited to a very focused subset of the policy-making landscape, and is subject to external shocks. As Cockfield and Botterill (2013) argue, this incrementalism has been subject to considerable and radical punctuations to which the whole of Australian agriculture has tended to eventually succumb, albeit with a willingness by the state to help with adjustment to the new state of affairs. We have seen this model in the ACT, where cage-free production was not simply regulated out of existence; instead, the territory government paid adjustment payments to producers. The industry did not ‘win’ this conflict, but its losses were moderated and paid out.

New relationships: legitimisation?

Halpin’s observation that the policy role played by AIOs is often sub-parliamentary may reflect a waning capacity or desire to win ‘big fights’ in the public arena. As Ian Randles observed:

We’re prisoners here of our own rhetoric, in some respects. We often say, ‘This is an industry that Australia can’t do without. This is an industry that the whole pastoral economy revolves around. The Kimberley will fall over for instance, or northern Queensland, if we don’t have this industry.’ Maybe it will, maybe it won’t. I don’t know. Once you start that, then you’re suggesting you’ve got more capacity than you really have. (Interview: 30 September 2013)

By ‘digging in’ to retain relevance and influence, in Halpin’s words, and by their reluctance to fight policy debates in public, AIOs have lost much of their political legitimacy and thereby their political capacity. This is reflected in the suspicion evident in some APO criticisms of industry – insider politics can be seen as illegitimate because it is shielded from popular participation (Tham 2010, 251).

This has led a variety of organisations to experiment with the formation of new types of relationship to address the issue of legitimacy and the allegations of capture. The most tentative has been at the level of ad hoc meetings between key AIOs and APOs. In some cases, this produces positive interactions that are marked by genuine information exchange (interview: R. Cox, 2 October 2013); in others, outcomes are less positive. The latter often results from the proximity of interactions to activist campaigns; meetings that take place during or close to the start of a campaign provide little perceived value to AIOs (interview: A. Spencer, 23 June 2014). One industry representative described hosting a visit with an APO that produced few enduring results and little trust, ‘just so they can say they’ve been on a chicken farm’ (interview: a representative of the chicken industry, 31 January 2014).

Better initial meetings may lead to enduring and regular if unstructured interactions between organisations (interview: W. Judd, 19 April 2013). These may produce useful levels of trust that result in information exchange and the resolution of concerns in informal ways that, in more hostile contexts, might ‘blow up’ (interview: CEO, QFF, 16 April 2013). For some organisations, this may lead to ‘backchannels’ of communication that reduce conflict, or are necessary where organisational stakeholders would be intolerant of meetings with ‘enemy’ organisations (some AIOs will not meet with organisations they perceive as an existential threat, but some will). Trust between organisations of this type, however, takes time to build, and negative interactions may limit potential relationships for long periods of time (interview: an animal welfare advocate, 5 September 2014). In some cases, this allows AIOs to ‘shop’ for preferred APOs with whom to form partnerships, demonstrating the value of mutual exchange in cross-validating organisational legitimacy.

Some of these exchanges are formalised. The most significant and amenable APOs willing to do this are the RSPCAs. The RSPCAs’ relationships with industry are complex, and include purely informal information exchange, representation in organisational policy-making, shared committee memberships, and formal commercial or cost-recovery relationships. Of the latter, RSPCA-branded standards processes have been discussed in detail, but the society’s formal relationships with AIOs also include programs like the PIAA’s ‘Dogs Lifetime Guarantee Policy on Traceability and Rehoming’. This program sees dogs purchased from PIAA members provided a guarantee of rehoming should they become abandoned or unwanted at any time. This is an interesting program because – on paper – it extends a lifelong duty of care over companion animals by the industry body. More significantly, it does not really seem necessary: PIAA members sell around 65,000 dogs a year nationally. Given the number of rehomed dogs to date remains small, the organisation’s membership would appear to have ample capacity to place these animals themselves. But the PIAA has utilised the agreement with the RSPCA for other internal and external reasons. Internally, the decision to outsource re-homing reflects an unwillingness by industry members to accept the cost and responsibility of the program (what if an animal cannot be homed?). Thus the industry body has socialised the cost of the program across its members.19 Externally, the program gives the comparatively unknown industry association stronger legitimacy through association with the strong welfare brand. This was on display in 2015, when the organisation used the program in making a case to retain industrial-scale pet breeding and retail sales in NSW, even in the face of opposition to these practices from the RSPCA itself (Joint Select Committee on Companion Animal Breeding Practices in NSW 2015).

Constantly conflicted? Veterinarians and welfare officers

Within AIOs, a special category of industrial workers exists: veterinarians (and their associated support staff) and laboratory animal officers. Both are professional groups of workers, in that they have a duty to their clients, the wider public, and their profession. This category of animal workers has ethical codes of conduct regulated by legislation, organisational governance systems and convention. Strong adherence to these codes is necessary to protect the welfare of the animals with whom they work, but these workers are usually employed or paid by animal owners (although some are employed by APOs or by the state). Unlike many other professional groups (Cribb and Gewirtz 2015), veterinarians and animal-welfare officers have two clients, whose interests may not coincide – or, from a strong rights or abolitionist perspective, may be fundamentally at odds. This tension is recognised within the professions.

As Williams, observes, this often leads to veterinarians playing a mediating role between the interests of animal owners and wider community standards in the course of their working day:

We live in countries with agriculturally based economies, where human use of animals is accepted by the majority of the population – including, quite obviously, the veterinary profession. So, in accepting such use, and given the competitive and global nature of the agricultural business of today, it’s inevitable that farmers’ aims are constantly to improve efficiency of production so as to be able to keep costs as low as possible. However, the line between increasing productivity and animal welfare cost is a fine one. A combination of a greater understanding of the effects of stress on animals as well as increasing scrutiny from society in general means that there is a continuing shift – that may be incremental but is also persistent – as to where that line is drawn. (2002, 2)

The formal policy of the Australian Veterinary Association (AVA) is to encourage its members to get involved with local animal welfare societies (Australian Veterinary Association 1997).

Some have suggested that negotiating this conflict places considerable moral stress on people in these professions. Fawcett (2013, 213–4) has argued that the considerably higher than average rate of suicide among vets results from pressures associated with their unavoidable involvement in activities that disproportionately prioritise non-animal interests. She cites the example of the practice of euthanasing animals purely for reasons of convenience (such as when the owners of a pet move house). This may be the case, and certainly it appears that proximity to regular euthanasia lowers inhibitions around suicide. However, in a recent analysis of data from 2002–2012 in Australia, Milner et al. (2015) argue that a variety of factors are at play in the profession’s suicide rates, including moral stress unique to the profession, but also issues that affect other professionals (such as high self-expectations and workload) and other rural workers (isolation), and having access to an easy means of death.20

Depression and burnout appear to be spread across the spectrum of veterinary practice, although small-animal practice (i.e. those treating companion animals) seems to involve additional stress. As Hatch et al. (2011, 465) argue, this is likely caused by the higher intensity of relationships between clients and their animals in non-industrial settings, combined with unrealistic expectations of veterinary intervention, but it may also be associated with the fact that individuals from rural backgrounds are more likely to work in large-animal practice (such as industrial veterinarians). As we saw in Chapter 3, those with rural backgrounds score lower on the Animal Attitude Scale, and so may suffer reduced moral stress.

Certainly tensions are evident between the reasons why people enter the profession and the practical realities of their work. In a survey of university veterinary students in Queensland, Verrinder and Phillips (2014) identified the motivations of young people coming into the profession. In their analysis, students are primarily and overwhelmingly motivated by care for animals over an interest in animal industry or personal rewards (Table 7.2). Over time, a clearer understanding of the realities of the profession are associated with stress and some disenchantment, which, as noted, is more common among those without prior exposure to animal industry (Heath 2002).

| Reason for studying veterinary science | Primary motivator |

In the top three |

|---|---|---|

| Enjoyment in working with animals | 57 | 117 |

| Helping sick and injured animals | 50 | 101 |

| Improving how animals are treated | 10 | 55 |

| Interest in science | 7 | 49 |

| Using practical, hands-on skills | 5 | 48 |

| Becoming part of a valued profession | 3 | 21 |

| Wanting a physical, outdoor job | 3 | 18 |

| Farming background | 2 | 9 |

| Developing a profitable animal industry | 2 | 3 |

| Good job security | 2 | 5 |

| One of the hardest programs to get into | 1 | 4 |

| Other | 2 | 7 |

| Family or friends work with animals | 0 | 5 |

| Financially rewarding job | 0 | 3 |

Table 7.2: Primary reason for studying veterinary science (n = 144). Verrinder and Phillips (2014).

But this ethical tension is also important in shifting the internal regulatory norms of professional organisations like the AVA. The significant role played by students in highlighting ethical challenges to the status quo is seen in their advocacy for enhanced welfare standards on campuses across Australia (O’Sullivan 2015a). As Verrinder and Phillips (2014) have found:

The majority of students were concerned about animal ethics issues and had experienced moral distress in relation to the treatment of animals. Most believed that veterinarians should address the wider social issues of animal protection and that veterinary medicine should require a commitment to animals’ interests over owners’/caregivers’ interests.

Key figures in the animal welfare movement such as Dr Andrew Knight, for example, emerged from this very type of ethical conflict in the teaching of veterinary practices, and the issues that motivated his move from practice to advocacy still exist in veterinary teaching institutions.

These issues include the refusal of some universities to provide a mechanism for conscientious objection to performing some types of medical practices on live animals, the use of ‘waste’ animals from racing (both live and dead) (O’Brien 2014), the use and handling of animals in education (interview: E. Hill, 20 August 2013) and the under-performance of universities in adopting the ‘three Rs’ of animal use in teaching and research (interview: S. Watson, 25 June 2014):

- replacement of methods that use animals

- reduction of the number of animals used

- refinement of practices to increase welfare.

Some trends run against the overarching assumption that this type of regulatory environment will reduce animal use. The development of genetically modified animals (a form of refinement and replacement) that provide better ‘models’ for particularly human diseases, for example, is one area where increased sophistication will increase the quantum of animals used in research. Similarly, there are concerns that structural issues that drive unnecessary use (such as funding cultures that privilege programs with animal models over non-animal methodologies; H. Marston, 23 September 2013) are actively ignored by university management because animal facilities provide higher research-funding yields.

This type of institutional gap is demonstrated in survey data from animal-welfare officers (AWOs) at Australian universities. In Table 7.3 we see that welfare personnel remain in tension with managers and those they regulate in advancing the three Rs. Thus, even in these sites of increased friction, the establishment of professional oversight of animal use has not produced a ‘regulatory revolution’ since the 1980s.

| Supporting actor | Average | Median | s.d. |

|---|---|---|---|

| University management | 4.61 | 4.5 | 2.35 |

| Researchers working with animal models | 4.5 | 5 | 2.04 |

| Animal ethics committee members | 3.22 | 3 | 1.22 |

Table 7.3. Animal welfare officers in Australian universities: reported support received on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 = extreme hostility to the role, 5 = neutral (neither support nor hostility), and 10 = maximum support for the role (n = 18).

Universities have, however, been particularly significant places for activism due to their comparatively open governance structures and the diversity of members on ethics committees. Activists have been able to see the impact of their work in changes to teaching practices, particularly around the sourcing of animals for veterinary training and the use of highly invasive and/or destructive teaching practices (interview: M. France, 19 May 2014). Because of the presence of scientists, veterinarians, welfare organisations and laypersons on these committees, they also serve as a communicative bridge between different ethical and technical perspectives (Scott and Carter 1996), within a framework that still privileges human interests. More recently there has been a move towards the institutionalisation of interest groups pushing for changes in veterinary standards based on arguments about enhanced welfare more familiar to mainstream APOs than to industry. Sentient, aka the Veterinary Institute for Animal Ethics, emerged from this type of campus activism in the mid-2000s as an interest group within veterinary medicine. This group forms another bridge between APOs and the animal-using industry, thanks to the presence of veterinary professionals working both for animal welfare organisations and in animal industry.

Both veterinarians and animal-welfare research staff have interactions with a wider set of stakeholders through various formal structures intended to ensure professional ethical integrity and calibration to social norms. The formalisation of these relationships, however, is variable. As the largest recognised professional group in animal welfare, veterinarians – both individually and through the AVA – have an automatic place in consultative and decision-making structures of government pertaining to animal welfare, as well as in other institutions and as a direct member of many AIOs (for example, the NFF and the Australian Companion Animal Council), while laboratory and teaching animal professionals have both institutionally based (the Australian and New Zealand Council for the Care of Animals in Research and Teaching, or ANZCCART, and individually based (the Australian and New Zealand Laboratory Animal Association, or ANZLAA) organisations that provide a locus for the consideration of animal welfare practices in lab and teaching contexts. These organisations have reacted, in different ways, to challenges from activists (ANZCCART through organisational inclusion, ANZLAA via dialogue).

While much of this exists in the insider world of local policy and administration, the nexus between science and public visibility is significant in considering the treatment of animals in public laboratories, as well as in zoos and circuses. We can consider these three animal-use industries on a continuum from ‘pure’21 science (public labs), to a mixture of education and entertainment (zoos), to pure entertainment (circuses). Significantly in these three settings, concerns about animal welfare have focused disproportionately on particular classes of animals, predominantly companion-animal species (particularly in veterinary education), primates (in labs and zoos), and exotic animals (zoos and circuses).

Circuses have been subject to considerable pressure to abandon the use of animals as entertainers, but the most effective campaigns have centred on their use of particular exotic animals, as opposed to animal use in general (Tait and Farrell 2010). Public laboratories have seen a decrease in activism around their use of animals in general, and an increase in campaigns targeting primates in particular. This has followed the introduction of improved welfare standards. Zoos, on the other hand, are subject both to the norms of ‘welfare-focused conservationism’ (Kazarov 2008) and to an intense public gaze. It is clearly easier to justify the use of animals for science and education than it is for entertainment. Nevertheless Australian zoos have had to invest significantly in the creation of high-welfare environments and treatment programs for a range of animals (particularly apes and elephants) to ensure that keeping these animals in captivity remains socially acceptable (Tribe 2009).

Responding to external challenge

AIOs are increasingly proactive in addressing the increased interest in welfare among consumers and the wider public, as well as some of the campaigns of APOs that aggressively target industry practice. On one level this is reflected in the quantity of policy development in animal welfare undertaken in the closed and private policy world of the inside track, where multiple stakeholders are engaged in negotiating acceptable practices incrementally. This can often take the appearance of ‘running dead’ on an issue: resisting change or making minimal adjustments based on a view that external pressure is inconstant and may abate. Often, this is a very effective strategy, as seen in the case of mulesing, where the cost of changes to welfare standards was spread out over a longer timeframe than activists demanded, with individual organisations leading change based on their own sense of the market.

This, however, provides an overly saccharine view of adjustment that misremembers the sense of ‘ambush’ experienced by industry actors, and underplays the frustration felt by more established APOs when their long-running campaigns and warnings were not heeded. The ongoing salience gap between individual industry actors and their more attentive representative AIOs raises a question: can industry effectively and proactively manage animal protection advocacy in the long term? While some issues remain largely consistent over time, in that APOs have maintained a core set of concerns over a long period, some industry actors are concerned that other industry members can be obtuse in recognising repeated warnings about welfare issues that present a significant risk (interview: I. Randles, 30 September 2013). Following the 2003 controversy over live-export deaths at sea, the chief executive of the peak live-export organisation compared the incident to an aircraft crash for the airline industry (AAP 2004): that is, an unfortunate but predictable event that necessitated a review of procedures, would have a negative effect on popular opinion, but would soon pass out of the public’s memory. Such complacency significantly contributed to the conditions that led to crisis in 2011.

In addition, the ‘hit and run’ nature of some recent campaigns (Bang 2004), as well as switching activist tactics, present challenges for industries that have adopted a static position on welfare issues. Some AIOs describe a ‘grassfire’ of activism: constantly burning but springing up in new locations unpredictably (interview: CEO, QFF, 16 April 2013). Owing in part to this, the response to external pressure often swings between adoption of new welfare paradigms and active resistance to change. These types of responses tend to occur in the more public political space, either because they happen in the context of well-publicised campaigns, or because the decision to change requires political legitimacy that can only be won in the public domain. In the following final section I will examine the range of responses to external pressures, from collaboration to conflict.

Getting on board: retail standards

Major retailers are sensitive to consumer mobilisation by advocacy organisations. Data about spikes in customer inquiries filters up from individual stores to head offices (J. Healing, Coles, in Clark 2013). This has led to the adoption of third-party standards or to retailers developing their own standards where none exist, or where they prefer (usually for cost reasons) to devise their own. However, the connection between consumer advocacy and changes in the supply chain is neither linear nor straightforward. A number of factors are at play.

The first is that consumer mobilisation has the capacity to signal initial shifts in consumer sentiment (by early adopters) in advance of more wide-spread changes. Active monitoring of these by retailers can be a first step towards adapting supply chains to provide higher-welfare products. This can be a medium-term process, where welfare concerns require considerable investment in new plants and equipment. On the other hand, if consumer mobilisation produces only quick ‘spikes’ that subside once APO public campaigns end, they may reinforce retailers’ belief that consumer commitment levels are weak and unlikely to translate into a long-term willingness to pay higher prices. Further, where demand cannot be met easily and quickly, retailers and producers may adopt changes that have more to do with branding than with any significant modification of their systems and infrastructure. If this effectively allays consumer concerns, the welfare shift may be largely symbolic, although retailers are aware that this can run the risk of being seen as ‘welfare-washing’, which can itself prompt activist mobilisation and affect the retailer’s brand.

A second factor is that consumer mobilisation is strongly moderated by analysis from retailers’ own information-management systems. While APOs that mobilise consumer activism online are able to determine the success of their campaigns more actively than ever (for example, by using online petitioning systems or analysing data from their own websites), retailers employ aggregated sales data. An APO, therefore, may see a campaign as successful if it results in a high level of mobilisation (interview: L. White, 24 September 2014), whereas retailers are looking at changes in sales volume and conversion rates on a more granular level (A. Dubs, Australian Chicken Meat Federation, in Clark 2013). The exception to this, of course, is the RSPCA, which captures sales data through its RSPCA-approved product system.

Finally, behaviour can be a prisoner of expectation. Major Australian retailers are international in their orientation, following global trends closely through their environmental scanning processes, employing transnational advertising and marketing firms (which both generate new ideas and resell them into different markets), and with an international movement of management personnel. Thus one interesting explanation for the responsiveness of major Australian retailers to consumer mobilisation is that they were forewarned by the experiences of retailers overseas. Australian welfare standards, and retailers’ capitalisation of welfare to promote brand loyalty and product differentiation (particularly in the face of new, low-cost international providers such as the German retailer Aldi), has been identified as lagging behind comparative markets overseas (interview: a representative of the retail industry, 22 April 2014). Thus when Australian APOs became more active in consumer mobilisation, major retailers recognised that this was in line with the experience of their international peers, and had already prepared responses.

Overall, the ability and willingness of retailers and producers to adopt higher welfare standards depends on a number of factors:

- Is there measurable consumer demand?

- Is there expectation of future demand?

- Does this provide value to the retailer and if so what type (overall ‘brand value’, demand value for a specific product, or a reduction in the risk of future consumer campaigns)?

- Can a downstream actor control or coerce compliance upstream?

- Is an authoritative or legitimate standard or standard-making body available?

- Could a less expensive standard be used to achieve the same result? For example, both Coles and Woolworths introduced pasture-fed certifications into their beef supply programs in 2014. Woolworths adopted the CCA’s Pasture-Fed Certified Assurance System (CPAS) with annual inspection, while Coles adopted an in-house standard with random inspection (McKillop 2014a, 2014b). It is likely Coles thereby negated any competitive advantage of Woolworths’ adoption of CPAS, but at a lower cost.

Based on this we can compare retail – the most frequent adopter of third-party standards – with other segments of the animal industry to explain the level of pressure to respond, and the capacity and likelihood of industry to do so (Table 7.4).

| Industry | Consumer demand for voluntary standards | Future demand | Do voluntary standards add value? |

Can the industry coerce or control actors further up the supply chain? |

Is there a voluntary standard available? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grocery retail |

Medium | Increasing | Yes (brand equivalence or competition) | Yes | Yes |

| Companion animals | High | Static | Yes (trust) | No | Potentially |

| Dog racing | Low | Uncertain | Uncertain | Yes | Potentially |

| Horse racing |

Medium | Increasing | Risk of death of some ‘stars’ | Yes | Potentially |

| Research animals, pest species | Low | Low | Uncertain, risk* | Yes | Yes |

| Research animals, privileged species | Medium | Static | |||

| Display animals, general |

Low | Static | Uncertain, risk if negative event | No | Potentially |

| Display animals, privileged species |

Medium | Static | Yes (animal ‘stars’ can be marketed) | No | Potentially |

Table 7.4. Animal-using industries’ relationship with voluntary standards. *The majority of Australian welfare officers (66 percent) do not think implementation of the three Rs leads to improved research outcomes (using publishing as the ‘standard’ measure of research value presently dominating university performance metrics), while some perceive it as a risk because of the higher costs it would entail.

Marketing and counter-framing

This emphasis on community perception, trust and branding highlights another key area of AIOs’ response to welfare issues and protectionism campaigns: strategic communication. In this area the media landscape has significantly changed over the last two decades. As we have seen in Chapter 4, in recent years APOs have been able to achieve increasingly regular ‘breakthrough’ campaigns with high levels of media attention. These have tended to shift media coverage of animal protection issues away from police procedurals involving offences against companion animals towards greater reporting of systematic issues about animals in production systems. This follows a deliberate strategy of lobbying with a view to changing popular opinion about the significance of animals, their treatment, and the responsibility of producers and retailers for improving welfare standards.

This success may seem surprising given the seemingly natural advantages of industry when it comes to media access and agenda setting. Industry has vastly greater financial resources for promotion. Less obviously but importantly, key animal-using industries also enjoy significant cultural privilege. As we saw in Chapter 4, these two elements – cash and culture – are connected. As Botterill (2006) argues, Australian agriculture has benefited from a deep fondness for rural life and rural people in the Australia psyche: farming is a noble profession, farmers are practical and straightforward people, rural life is healthy and wholesome, and rural communities are strong and resilient. These ideas are reproduced in the marketing language of producers and retailers. This demonstrates how farming, wrapped up as it is in history, nationalism, mythology and a politics of nostalgia, has not fully negotiated the transformation, begun in the 1970s, from privileged sector to a business just like any other.

Botterill observes that rural communities often perceive ignorance and anti-farming bias in the dominant city-based media. She argues, however, that while the accusation of ignorance is correct, that of bias is not. Farming and farmers generally receive extremely positive coverage in the Australian media, which often reproduce a nostalgic pastoral idyll. This has provided political advantages for the sector, as well as concealing some issues from wider debate. For the rural sector, however, this reliance on a reservoir of good will is problematic, based as it is on Baudrillard’s (1994) simulacrum: a self-referential media image rather than an accurate portrayal of the world. While this has obvious advantages for farming, it also presents challenges. The distance between the real and the representational heightens the risk that if reality fails to match expectations, a cognitive shock can occur. As seen with the impact of activists’ footage, this heightens the emotional response of viewers and affects trust.

The power of this myth is clear when we consider how practices that are in effect ‘farming’ are not cognitively included in this category. The clearest example is the supply of animals for laboratories and as companion animals (so-called puppy farms). These commercial breeders do not have an established commodity council, nor the symbolic respect of being ‘real farmers’. This lack of cultural deference has made it easier for these sectors to be brought into regulatory dialogues and to be subject to state intervention. In Victoria and NSW, governments have openly entertained regulations that would scale down the size of production facilities, something that would be unthinkable in ‘real farming’.22

Attempts by farming organisations to acquaint citizens with conventional farm practices have struggled. Partially this is because the message is not controlled by farming organisations, but produced as commercial advertising by secondary processors and retailers. Advertising’s power lies in the reactivation of latent or pre-existing attitudes (Bullo 2014). Thus, while farmers may want to update how they are perceived to reflect modern agricultural realities, they are effectively counter-messaged and outspent by retailers and producers who are invested in more sentimental tropes.

In addition, reframing can be complex because animal welfare is complex. In work done for the chicken industry in 2012, market researchers found that communicating stocking densities as a ratio per square metre elicited a more favourable consumer response than per hectare (because of the smaller absolute numbers involved), but that attempting to create euphemisms for beak clipping (‘beak treatment’) only elicited negative responses from focus groups, presumably because it alerted consumers to practices they prefer not to consider (Brand Story 2012). The complexities of educating consumers are beyond the capacity of many AIOs, and some fear that engagement with the topic will raise the salience of the issue while not actually improving community knowledge.

This assumes that industry would win a pure ‘war of ideas’ if only consumers had the full picture, an assumption that is contestable. Since the 1980s, some industry groups have pushed for animal protection and welfare in closed, technical review processes as a means to combat the emergence of the second wave of protectionists. This was based on a belief that industry had the superior knowledge of animal welfare. The Livestock and Grain Producers’ Association of NSW,23 for example, published a report in 1980 calling for the formation of an inter-jurisdictional mechanism to review and resolve welfare concerns (Brown 1980). In describing the politics of animal welfare as ‘objectivity versus emotionalism’ (5, emphasis in original), the report clearly put industry in the first category, and dismissed APOs as having little more than lay expertise:

The diagnosis of animal health/welfare problems – mental or physical – by untrained or unqualified personnel is no more valid than the opinion of a person in the street on human medical issues. (23)

Industry has since invested money in third-party animal welfare research. In Queensland, for example, AgForce (as the Cattlemen’s Union) played a role in establishing a chair in animal welfare at the University of Queensland in the 1990s, from which the Centre for Animal Welfare and Ethics later emerged. This is not without problems, however, particularly where research outcomes clash with established practices. In these cases, the reliance on pure evidence-based policy-making is often moderated in such a way as to undermine the basis of industry’s claim to dominate knowledge. As a Western Australian SFO officer observed:

Typically the refrain you will hear is, ‘We want animal welfare decisions based on science, evidence-based’ (brackets: ‘but only if they suit us’) . . . A classic example is teeth grinding for sheep . . . So, what [farmers] do is grind [sheep’s] teeth so they don’t fall out so they can continue to graze properly and they have a longer productive life. However . . . they use an angle grinder. They put a gag in the sheep’s mouth. If you’ve ever seen it, it’s pretty confronting. And it’s commonly done because it’s considered to be prolonging the productive life of the animal . . . In Victoria, they did a substantial survey a number of years ago, I believe on 30,000 sheep with their control group, and there are no nutritional benefits for the sheep [in] grinding their teeth.24 So, these [results] are fact, science, evidence-based, okay? So, teeth grinding in the new standards would have been illegal. However, we still had people in WA saying, ‘I’ve got to grind those sheep’s teeth, otherwise they won’t be able to put on condition, I’ll have to send them to abattoir.’ But the science has been there for a number of years, so: what do you do there? A very difficult situation. And the way we did it was, we said, ‘Why don’t you just let us grind the teeth on the sheep we think need it – not all of them? Make it illegal on a flock basis.’ Because people used to do it on age basis, and we said, ‘Let’s not do that. Let’s satisfy these guys who still believe [it has] some practical basis.’ (Interview: I. Randles, 30 September 2013)

In some areas this has led industries to back away from supporting welfare research that may challenge current practices (interview: a former animal welfare officer, 1 August 2014).

Because of the overwhelming focus on production efficiency, much of the established research on production systems has failed to provide industry with useful data on welfare outcomes (interview: R. Cox, 2 October 2013). Thus, calls for the use of evidence-based policy can be less effective in smaller industry segments where research investment around welfare has not been a priority. Further, the connection between science and implementation can be problematic in those industries with large variations in operator size (interview: CEO, QFF, 16 April 2013). Thus we can see a difference between, for example, cattle on the one hand, and chicken production on the other, and connect the latter’s tighter industry integration and generally higher scale of operations to the greater capacity to develop an evidence base from that industry.

While many APOs may have been largely or completely dominated by laypeople in the 1980s, their capacity has changed considerably. The RSPCAs have always taken pride in advocating for evidence-based policy (interview: M. Mercurio, 4 June 2013). But this varies across species, locations and contexts. To some extent this is consciously managed by the RSPCAs’ willingness to engage in some issues more deeply than others. As their national CEO observed:

So, companion animals get obviously much more expertise in state and territory societies than there is on some of the nuances of farm animals or transport or wild animals. It’s not always the case but . . . [most societies] feel very confident talking about companion animals. (Interview: 24 June 2014)