1

History

This chapter provides a short history of the relationship between humans and animals in Australia. The history of this area is significant in shaping the conditions participants in the policy process face today: this includes the material conditions of animal production systems, the industrial mix and structure of animal industries, cultural expectations about what is normal and appropriate, and policy paradigms and legal frameworks. From a social-constructivist perspective, this history conditions the expectations and understanding of participants in the policy process. From a rational-actor viewpoint, historical forces shape the distribution of politically relevant resources. From an institutional point of view, history ties particular forms of politics to particular parts of the constitutional-legal system (Stewart et al. 2008, 44). This chapter will demonstrate that our current ‘naturalised’ relations with animals are the product of cultural factors and policy decisions made by successive governments, and that the current ‘advocacy explosion’ around human–animal relations is not unique in the history of modern Australia.1

Human and animal relations in Australia

Before Europeans

While it is extremely difficult to generalise about Indigenous cultures, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – as established hunters and gatherers in a landscape of which they had very detailed and local knowledge – maintained a view of their physical environments as a complex set of inter-related connections between animal, human, plant and geological features. In this animals played a role in social and spiritual life as food, as companions, and as totemic signifiers.

Crook (2008, 4) considers it unlikely that Australia’s Aboriginal people engaged in vegetarianism, and so the use of animals is likely to have been a social and cultural norm in what is now Australia. While European-style farming practices were not established in Australia until the start European occupation (with the exception of the Gunditijmara people, who engaged in eel farming in natural and artificial waterways) (McNiven and Bell 2010), animal-use practices included extensive fishing in mainland coastal areas and wetlands, hunting, and fire-stick agriculture associated with ecological management. As in contemporary Australian society, the production and consumption of meat was gendered. Farrer (2005) argues that women’s gathering contributed the majority of Aboriginal diets. This means that Aboriginal people probably consumed considerably less meat per capita than the first European arrivals.

This said, it is likely that Aboriginal people had a less utilitarian or instrumentalist view of animals than did Europeans at the end of the 18th century: animals were not valued simply in terms of their contribution of meat and skin to humans. As long-term managers of the environment, Aboriginal people had an interest in ensuring that plants and animals used as food and medicine, and as part of spiritual practices, were sustained. This was part of a wider duty to country that informed cultural knowledge and beliefs. This knowledge included an understanding of animal behaviour, as well as limits on animal exploitation to ensure sustainability (the maintenance of ‘good country’; Rose 2011, 26).

As part of this complex system of practical knowledge and spiritual beliefs, Indigenous people adhered to a range of prohibitions regarding animals, including specific restrictions on the consumption of personal totem animals, as well as generalised restrictions on hunting and foraging in areas of spiritual importance. Attributing life to a wide range of environmental elements, Indigenous people recognised the consciousness of plants and animals, even if human physical needs required their use as food, clothing and tools (Rose 1996, 8–9, 23). Animals were considered to have a high level of consciousness and even human characteristics (humour, greed, etc.), reflecting cross-species kinship.

Farm politics after 1788

With the colonisation of Australia, European attitudes to animals were transplanted. The settlers were largely uninterested in local understandings of the environment beyond identifying water supplies and potential farmland. The immediate concern of the new arrivals was to ensure enough food and muscle power to survive in an alien environment, one that appeared quite unsympathetic to their established agricultural production practices (the first stock animals brought to the colony, cattle and sheep, were lost or died, requiring a number of further attempts to establish productive herds; Henzell 2007). Colonial government policy (both domestically and in Britain) focused on the establishment of self-sustaining colonies, both to provide sustenance for the new inhabitants and to raise capital to pay for colonisation.

The most obvious example of this initial policy focus was the development of the Australian wool industry from the 1820s (Davidson 1981, 6–7), which, unlike meat (which at the time could not be exported), would find a market in England. Herding of sheep (for wool export and for domestic consumption) and cattle was significant in facilitating the expansion of colonial land occupation away from the points of initial settlement, as these animals were ‘portable larders’. In a country where crops were initially difficult to grow, where horse-power and labour were limited, and where there was only a small regional market for exports, herding in the large savannah-like areas west of the Dividing Range made commercial and political sense.

The role of government in encouraging animal agriculture in colonial Australia, therefore, tended to focus on fostering pastoralism and the distribution of lands. Land distribution shaped agricultural practices and colonial politics. Attempts at the monopolisation of lands around the initial settlements further encouraged outward expansion and pastoralism (Pearson et al. 2010). While those with extensive landholdings were often politically powerful (the ‘squattocracy’), the comparative shortage of labour in the colonies tended to mitigate against the power of landholders after the end of transportation mid-century. The most obvious example of this was the political preference for ‘closer settlement’ (from about 1860 in New South Wales, Queensland, and Victoria): policies aimed at the creation of smaller blocks leased by yeoman farmers (Pearson et al. 2010; similar attempts were undertaken in the early 20th century with various ‘soldier-settler’ farming schemes).2 The development of the labour movement in the late 19th century from within the shearing workforce demonstrated the comparative power of labour when compared with its European counterparts.

Other areas of state investment supported new agricultural practices. Local governments were involved in setting up slaughter-houses to supply local meat and to create jobs. Dairying received a considerable boost following investment in road and rail transport with the prosperity of the late 19th century (Peel 1973, 55). Dairying was also seen as an effective way to produce smaller family-focused farms in line with the closer settlement movement; this is one of the reasons why deregulation occurred in dairying later than in other agricultural sectors. With federation, state-sponsored agricultural research fell under the remit of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIRO, established in 1926), with an emphasis on animal breeding for local conditions, new food production practices, and pest control. This was not without resistance from state-based authorities, but the need to ensure the supply of safe and reliable foodstuffs during the Second World War assisted in promoting the role of the national applied-research organisation’s involvement in agriculture and food technology (Farrer 2005).

Meat and the new Australian identity

While a taste for meat eating was inherited from the British (regarded in the 18th and 19th centuries as among the largest consumers of meat and alcohol in Europe; Santich 1995), the consumption of meat was a formative part of the Australian experience. New settlements were highly regulated by the government, and the provision of a basic ration including regular meat encouraged meat production and established the expectation of meat in a working man’s diet (a norm that can be seen in the 1931 ‘Beef Riot’ in Adelaide, prompted by the substitution of mutton for beef in the unemployment ration). Meat was both plentiful and cheap when compared with England. This, plus the relative scarcity of other foodstuffs such as vegetables and processed foods, meant meat and simple breads made up the backbone of the diets of people working on sheep and cattle stations. Meat was commonly eaten at every meal in the colony, compared with once or less per day by labourers in the home country (Santich 1995).

The bountiful supply of meat among all classes in the colonies was observed by travellers, and became a selling point for inbound migration following the end of convict transportation, using slogans such as ‘Meat three times a day’ (1847; Ankeny 2008, 20). In colonial Australia, meat could be cheaper than bread. Attempts to moderate this monotonous meat diet were encouraged from the 1850s, but this was mitigated against by the high cost of fruit and vegetables, by cultural preferences (still seen today in the tradition of the summer Christmas roast), and by dietary theories that muscle output (labouring) required muscle input (meat). This remains a popular trope in advertising.

Farm policy after the Second World War: protection to free trade

The development of an effective agricultural sector that could both meet the needs of Australians and provide material for export was part of a long process of nation building from the colonial era into the 20th century. With federation in 1901 the new Commonwealth government found itself with limited constitutional powers to act systematically to produce agricultural policy. State and territory-based policy-making had produced a raft of initiatives governing land distribution and allocation, with the most significant policies developed around the management of animal diseases. This included the formalisation of stock routes and disease districts to control and prevent the spread of illnesses, including the use of some levies for disease mitigation.

The Second World War significantly altered the involvement of the Commonwealth in farm policy. First, the introduction of price and export controls, as well as rationing, saw the elevation of farming from a means of national development to one of national survival. The impact of the war on global production and trade had implications that lasted into the 1950s and beyond, and successive Australian governments attempted to manage the anticipated demand surge and input scarcity that had been observed following the First World War (Hefford 1985).

Under the Liberal–Country governments of the 1950s and 1960s, this led to the development of a complex array of farm policies that encouraged investment through favourable tax concessions and direct subsidies for inputs (particularly chemical fertilisers and fuel; Godden 2006: 154), built infrastructure (irrigation and the ‘beef roads’ of the 1960s), provided disaster and drought assistance (Botterill 2003), established marketing assistance and export control, supported industry rationalisation through exit grants, and implemented price-control mechanisms in a number of farm sectors (wheat, dairy and wool).

From the 1970s this type of ‘protection all round’ policy began to give way to the language of economic rationalism: policies became increasingly subject to formalised review based on strict application of market efficiency (Botterill 2005). In addition, government support had been subject to considerable ad hoc decision-making, creating political problems in managing the agricultural portfolio. While this shift in policy orientation elicited political resistance from some in protected agricultural sectors, the declining size of the agricultural industry (both in terms of the number of jobs involved, and as a proportion of GDP) reduced its political power (Martin et al. 1989, 7–9). This period coincides with the formation of the National Farmers’ Federation, a recognition that the Country/National Party and the political class as a whole could no longer be relied on to automatically ensure the interests of farming industries.

While the wool and dairy industries retained – for a time – some degree of pre-1970s protectionism, minimum price guarantees for wool ended in the early 1990s and dairy followed a decade later. Today, industry support is less explicitly protectionist: direct industry support is provided in the form of public–private research funding through the Co-operative Research Centres (CRC) program (Godden 2006). CRCs are not, however, unique to the agriculture sector. More specific support can be found in ongoing biosecurity measures that limit the import of some animals and animal products, ostensibly because of the risk of importing disease. Under these arrangements, import permits are required for food products, with a range of restrictions based on the type of import, its source and its processing prior to arrival. Thus, chicken meat can be imported only from New Zealand, whereas there are fewer restrictions on pork. While these controls are presented as being purely for quarantine purposes, their commercial impact on producers and in international trade negotiations makes the overarching regulatory process, as well as the determination of individual cases, highly political at times.

Agricultural policy has thus shifted away from being a ‘gift’ bestowed on industry by policy-makers, and towards administrative standardisation and parity with other welfare programs. While farming remains to some extent a special and politically sensitive area due to the remaining influence of the National Party, agriculture has been subject to a move to standardise treatment across and between different sectors. While farming organisations, like many producer groups in pluralist democracies, have the advantage of access to policy-makers, we can see a narrowing of focus in agricultural policy-making over recent decades, and deliberate attempts to structure relations between the state and industry through a narrower range of representative bodies. This has implications for the political capacity of agricultural industry groups: they face a trade-off between achieving ‘insider’ status and accepting a narrower canvas on which to develop policy (Walmsley 1993, 46–7).

In defence of animals: animal protectionism in Australia

The last two centuries have thus seen major and ongoing changes in animal-related industries. During the same period, Australians’ attitudes to the animal world have undergone a revolution. Croft (1991), for example, demonstrates how settlers attempted to grapple with native animals’ place in their biological and social schema while at the same time reproducing agricultural norms and practices from ‘home’. Animals such as the kangaroo have variously been food, scientific curiosities, sporting trophies, economic commodities, pests, national emblems and subjects of conservation by settlers and settler governments. What the new arrivals did not endeavour to do, however, was to systematically emulate the pre-existing patterns of food production and consumption of Indigenous people (Farrer 2005).

It would be a mistake to assume, however, that the Australian animal protection movement is a wholly new phenomenon. Attempts to change our attitudes to animals can be found less than 50 years after the arrival of the First Fleet, in the passage of the first animal welfare legislation in Tasmania in 1837. Overall, however, the development of assertive animal protection organisations (APOs) came quite late in the colonial era, and the subsequent history of animal protection politics is marked by an interesting abeyance or slowdown of activity for at least 40 years, between the 1920s and the 1960s.

Early influences from afar

One of the key influences in the formation of formal animal protection laws in pre-federation Australia was the Royal Society for the Protection of Animals (RSPCA) in England. It was not the first organisation of its kind, but the lack of enabling legislation to permit prosecutions had led to the rapid demise of earlier groups and societies. Established in 1824, the RSPCA was formed in response to the passage of Richard Martin’s Cruel Treatment of Cattle Act two years before. This legislation prohibited the cruel and improper treatment of ‘Horses, Mares, Gelding, Mules, Asses, Cows, Heifers, Steers, Oxen, Sheep, and other Cattle’. This provided the foundation for the expansion of anti-cruelty laws in the United Kingdom, particularly against animal fighting and baiting, which were added to the legislation in 1835 (Kalof 2007, 137–8). Legislation for the regulation of knackeries followed in 1843, and the licensing of vivisection in 1876. It was also significant in placing animal welfare within the paradigm of the criminal code. At first, the laws were personally prosecuted by Martin, who hired investigators to bring charges against offenders (Fairholme and Pain 1924, 30–40). The RSPCA assisted, but its capacity was limited, and the state was soon drafted into assisting with policing. London metropolitan police and military personnel, for example, were deployed to suppress bull-running (a type of baiting) in 1838. (It is important to note that these laws only applied to non-owners. As in other areas, there was a tendency for early anti-cruelty laws to focus, explicitly or implicitly, on the regulation of working-class people.)

It is interesting that legislation was promoted by individuals rather than associations prior to 1822, demonstrating the difficulty of advancing a legislative agenda for the protection of animals from cruel and unusual treatment (such as attempts to ban bull-baiting at the turn of the century, and more general-purpose legislation in the early 19th century, proposed by Lord Erskine). While welfare legislation in the English-speaking world predates Martin’s Act (following Proverbs 12:10, the Massachusetts Puritans formally prohibited ‘Tiranny or crueltie’ against domesticated animals in 1641, although like Martin’s Act this reflected practical and economic concerns, rather than a blanket concern for non-human animals), the passage of this legislation in the ‘mother of parliaments’ served as a model that was influential in the passage of similar legislation and the emergence of similar organisations in Australia.

Colonial activists

The development of animal welfare activism in Australia has a number of interesting sources. The first is the transfer of ideas from the United Kingdom to Australia by informed locals keeping up with news from home, and by ‘new chums’. The first APO was the Victorian Society for the Protection of Animals (VSPCA), established in Melbourne in 1871, some six years after the introduction of specific anti-cruelty laws in that colony. This group was quickly followed by similar associations in the other colonies, demonstrating the spread of these ideas across the continent at this time.

While the SPCAs in Australia were formally independent, other activist organisations had a direct relationship with groups and movements in the home country. The British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV) is a good example of the type of international organisation active during the 19th century. British anti-vivisection had an international focus from its beginnings. As Murrie (2013, 259) notes, early concerns in England focused on vivisection by French scientists, who were leaders of the practice. Concerned about the rapid expansion of vivisection among scientists, the BUAV engaged in public debate about protection laws and helped to spread information about issues and legal developments around the world. It remained active in Australia through to the 1980s, and still exists in a small form today.

While these specific abolitionist and welfare groups tended to focus on the reduction of animal suffering, their origins lie in an array of religious social reformist organisations active during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Christian temperance and abstinence groups (the largest social movement of the 19th century; Allen 2013, 150) came together with a range of nonconformist denominations (Christian Spiritualists, Theosophists, Seventh-Day Adventists and others) in the promotion of dietary reform. This reform often focused on the advocacy of vegetarianism, albeit largely for the urban classes, removed as they were from manual labour. Rejecting the conservative notion of ‘the fall’ in favour of a view of human progress and perfectibility through personal discipline (Smith 1965) and (for some) scientific inquiry, they were active proselytisers of alternative diets and progressive social causes including early feminism and expanded democratic participation.

The role of nonconformist religious groups is important in pre-federation Australian animal history as they drew inspiration from a wide range of countries (including Germany, the United States and India) and included influential figures willing to advocate publicly for their causes. The VSPCA, for example, was promoted by the future prime minister Alfred Deakin when he was in colonial parliament. Part of the appeal of the movement to political elites was its focus on the conduct and discipline of the working classes (particularly regarding alcohol use, but also in the promotion of healthy living more broadly), therein supporting the development of a disciplined and sober workforce suitable for a modern, industrialising economy (Allen 2013, 153). Like the temperance movement, these movements were also significant for their inclusion of women as founders and in senior leadership roles.

Declining concern for animals

While the SPCAs would continue their work to the present day, the outbreak of the First World War marked the start of the decline of many groups within the movement. The high-water mark of the temperance movement was the introduction of 6pm closing of hotel bars and pubs in 1916 (coinciding with the need for social discipline during wartime; Allen 2013, 162). However, while it might be possible to blame the two wars and interwar depression for the waning of interest in social-improvement organisations, there appear to be more complex reasons for the decline of these groups (Guither 1998, 4–5).

The movements that supported dietary reform in Australia appear to have fallen in popularity by about 1908, with all of the Australian vegetarian societies (formed in the last decades of the 19th century) having wound up by that year (Crook 2008). In part, these groups were victims of their own internal inconsistencies: Spiritualism – one of Deakin’s keen interests – also promoted rationalism via scientific inquiry, and thereby encouraged the scientific debunking of the very frauds it featured in many of its public performances (Smith 1965, 259). While these groups were active promoters of dietary reform, this too came under challenge from the medical profession and state departments of health, who had by now established a greater claim to scientific authority. In addition, Thompson (2002, 57) argues that nonconformist churches suffered considerably with the rise of British patriotism in the lead-up to war. Many Protestants shifted towards the more socially conservative and politically acceptable Church of England as an expression of patriotic Christianity.

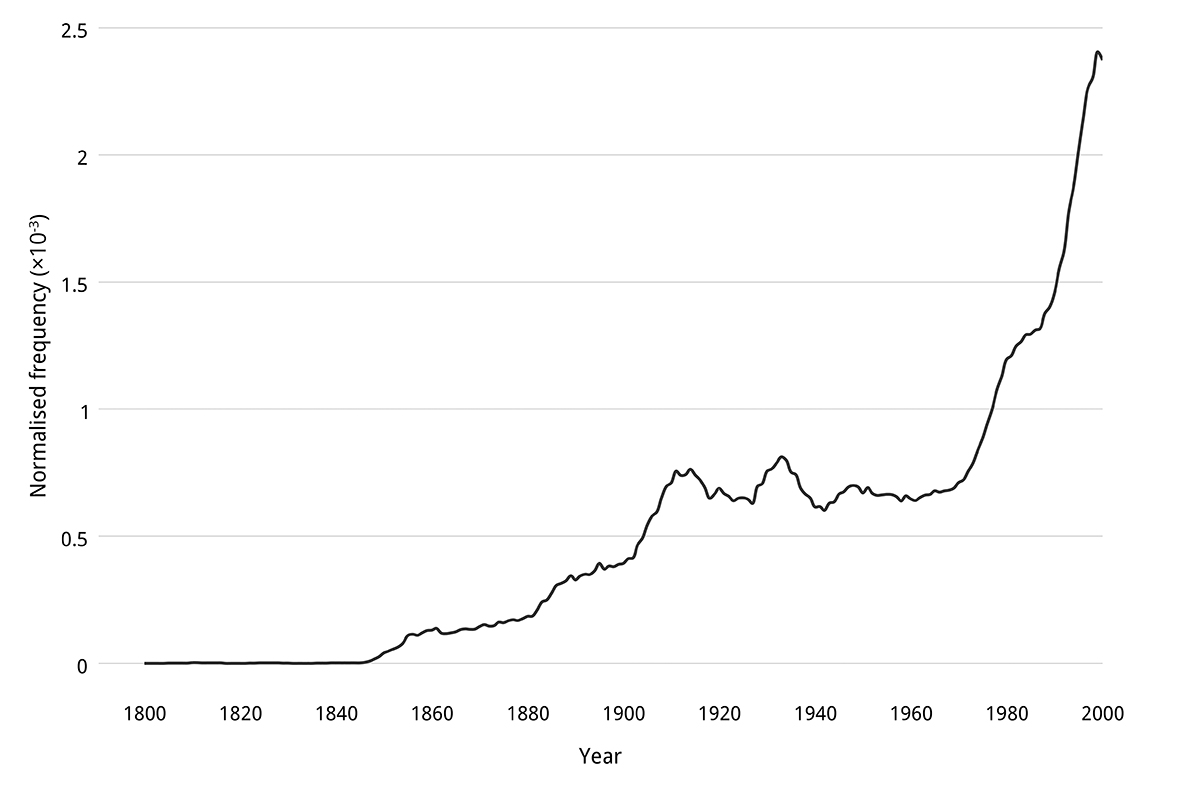

After the First World War health promotion moved firmly into the hands of the expanding health departments. Following the establishment of a national dietary survey in the late 1930s, the first comprehensive diet for ‘national survival’ was published, aiming to address perceived deficiencies both in total caloric intake and in the consumption of milk and eggs specifically.3 These guidelines became entrenched through rationing during the Second World War, further moving the regulation of diet into the hands of the state (Santich 1995). Importantly, this type of dietary advice was influenced by eugenics thinking at the time, which, in Australia, had a strongly racialised component. This has significance in later debates over live export and issues of national identity, as we will see in coming chapters. Overall, it appears that a wide range of factors external to, as well as within, the 19th-century food reform movement led to its rapid decline in the early 20th century, and to its failure to revitalise significantly until the late 1960s. As Figure 1.1 illustrates, in the first era of popularised diet alternatives, published book references to ‘vegetarian’ rose rapidly in the last quarter of the 19th century before flattening out after the First World War. They did not begin to increase significantly again until the 1980s. Given the international nature of the movement from the 19th century, it is not surprising that this is not a uniquely Australian phenomenon.

Figure 1.1. Frequency of ‘vegetarian’ in English-language books published in Britain, 1800–2000. Drawn from data provided by the Google Ngram Viewer (books.google.com/ngram). US publications (not shown) reveal a very similar trend.

During the intervening period, animal protection issues remained largely the preserve of the various state-based SPCAs and smaller, specialised bodies. Competing welfare organisations formed during this period at times placed pressure on the SPCAs over their service provision and lobbying efforts (Pertzel 2006). Over time, these organisations shifted the balance of their attention towards companion rather than industrial animals. This shift had structural and cultural origins. Structurally, the start of the 20th century saw the bifurcation of animal welfare regulation. Through the introduction of specific exemptions from cruelty laws for particular farming practices, animal welfare regulation was effectively divided into two types: the decriminalisation of farming practices seen as necessary for production, and the ongoing application of general anti-cruelty criminal law to non-farmed animals (White 2008). Culturally, Australia was becoming increasingly urbanised and animal organisations followed this trend. With a tendency to attract patronage from social and political elites, these organisations developed into the acceptable face of animal welfare promotion (their designation as royal societies from the 1930s considerably assisted in cementing these organisations’ social respectability; Budd 1988, 94), working with governments and benefactors to build infrastructure and slowly increase their levels of staffing. Nevertheless, an affinity between the increasingly respectable RSPCAs and the more radical abolitionist anti-vivisectors remained. White’s 1937 volume on the history of the RSPCA in Queensland praises ‘the extremists’ (120) of the BUAV and others just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, even as it tends to focus on more incremental reforms in Australia, such as the adoption of more humane slaughter technologies. This period saw the slow consolidation of legislation focused on the prosecution of cruelty, with an emphasis on the provision of services to animals in need and on resolving social problems, such as an excess of stray companion animals, through the operation of pound services and various dog and horse ‘homes’.

A ‘second wave’?

While the persistence of anti-vivisection activism during the mid-20th century demonstrates that more radical views about animal treatment never completely vanished, the 1960s and 1970s saw a renewed interest in animal politics, challenging the primacy of humans. Between the first and second waves, working animals largely disappeared from city streets across Australia, as developments in automotive technology flowed through from the war to the peace-time economy (Budd 1988, 20). Tractors outnumbered horses by 1946, demonstrating the rapidity of this transition.

Significantly, the direct visibility of the ill-treatment of horses by working-class men (particularly the infliction of exhaustion through overloading) served as a primary driver of urban mobilisation in the 19th and early 20th century. A typical account appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald on 27 March 1887:

An ‘Eye-witness’ writes to say that a disgraceful scene of cruelty took place in Palmer Street, Wooloomooloo, on Saturday night, lasting from half-past 11pm till quite half-past 12. A drunken man in charge of a butcher’s cart and horse most fearfully ill-used the poor animal, which was to all appearance thoroughly tired out, felling the poor beast to the ground four different times, and beating it with the butt-end of the whip. There were two other men with him, evidently his companions, who stood and yelled, and seemed to glory in the scene.

After the Second World War, city-dwellers’ exposure to animals shifted considerably towards companion animals and animals exhibited in shows and zoos.

The re-emergence of the movement in the 1960s and 1970s tends to be associated with other ‘liberation’ movements attacking social orthodoxies (black liberation, women’s liberation, gay liberation) (Townend 1981). As Sandøe and Christiansen (2008) argue, this mirrors the association of Richard Martin’s Act with the abolition of slavery in the UK in the 19th century. As we will see in Chapter 6, while it is possible to identify two distinct ‘waves’ when looking at the formation of new groups and the mobilisation of public opinion, a clear distinction between them as ‘welfare’ and ‘rights’ movements is quite false. Certainly, however, this period did see the creation of new, distinctive groups who increasingly used the language of animal ‘rights’.

While the direct catalyst for the new liberation organisations in Australia was the publication of the Australian academic Peter Singer’s Animal liberation (1975), this was just one example of a new literature on the industrial production of animals in post-war agriculture. The start of renewed interest in animal welfare issues by the wider public was associated with the publication of an exposé of intensive agricultural production by Ruth Harrison in Animal machines (1964). Reflecting a social norm that had seen wide-scale automation and de-population of agricultural industry, Harrison’s work (introducing the term ‘factory farming’ into the animal rights lexicon) appraised readers of the reality of modern farming practices and the implications of the adoption of scientific management in agricultural production (1964). Animal machines informed Singer’s writing, and the 1970s saw the formation of organisations in NSW (1976) and Victoria (1979) that took their names directly from Singer’s book.

The significance of these small organisations lay less in their initial influence than in the introduction of a radical ethical challenge to the treatment of animals. The second wave was not simply an increase in political organisation around animal protection and welfare issues, but a challenge to the basic premise on which Australian animal welfare laws rested.4 Importantly, it was at this time that the specific exemptions to cruelty charges enjoyed by rural producers since the early 20th century were transformed into generic exemptions for ‘accepted farm practices’, a change that reflected wider policy-making trends and served to reduce the impact of the new radical groups (see Chapter 8).

Conclusion

The history of human–animal relations in Australia is a political one. The capacity of the emerging Australian state to impose its will on the continent has been shaped by environmental realities, as well as by the political economy of the new colony. The British colonial project needed animals to survive and to form a microcosm of the agricultural system found in England. The colonists’ willingness to ignore or discount all that had come before reflected a political desire to deny a human history to the new continent. As the Australian system of state-sponsored agricultural development emerged, the use of animals became crucial to national development and to the establishment of family-based farms as a core economic unit. This history remains inscribed on the landscape of Australia, both physical and political. Animal agriculture was key to establishing the success of the new nation as a self-sustaining colonial enterprise. This provided regional and rural interests with political influence and enabled them to promote and protect agriculture. Even once farming was no longer the primary source of Australian wealth, this history was retained in the institutionalisation of agricultural interests in government departments, and in the wide range of private interest groups and associations active in policy debates.

The history of animal welfare and protection policy has similarly been shaped by Australia’s willingness to import ideas from overseas. The migration of political radicals, free-thinkers and social dissenters to the colony served to more rapidly distribute some of the new challenges to the status quo. In the end, however, the economic and geopolitical realities of the emerging nation came to dominate. It is interesting, therefore, that the second wave of dissenters emerged from the work of an Australian (albeit heavily influenced by thought in the UK) during a time when the dominance of traditional agricultural practices was subject to considerable economic and political upheaval. This political opportunity allowed a radical challenge to the status quo and a new critique of conventional practices. With the traditional power of rural voices in decline, these political currents were not shut down in the way that they had been 70 years prior, when an expanding state–agricultural partnership had been able to dominate public discourse more effectively. This second wave has led to the intensification of challenges to the status quo, with the activism of the 1970s giving way to a greater diversity of ethical challenges to established patterns of human and animal interaction. In the next chapter, I examine a range of perspectives on the ethics of humans’ relationship with animals.

1 A timeline of human–animal relations in Australia is provided in Appendix E.

2 These policies were resisted through a variety of means both legal (e.g. political lobbying) and illegal (e.g. the ‘dummying’ and ‘peacocking’ of smaller licences by established landholders).

3 This difference between and emphasis on dietary advice and other aspects of animal use within the wider movement may explain the longer lifespan of the BUAV, which peaked in the 1940s (when measured in terms of the number of active branches internationally).

4 The distinction may be less significant than some have argued. Certainly parts of the anti-vivisection movement were abolitionist in their objectives in the late 19th century. However, the anti-vivisection movement tended to focus on scientific practices, rather than seeking a more universal application of their moral concerns.