2

The advent of noise and health complaints

Modern windfarms have operated since the early 1980s, and noise complaints from a small number of families concerning one turbine in North Carolina are on record from around that time.1 Details of this episode appear to have escaped the attention of the anti-windfarm movement for nearly 30 years, until a report resurfaced in 20132 and began to attract excitement on anti-windfarm websites as evidence both that the noise problem had been around for a long time and that the wind sector, government and NASA had conspired to suppress the information in the intervening years, despite the turbine being an experimental ‘downwind’ design that is not representative of current technology turbines. But with that one exception, there were no documented noise or health complaints throughout the late 1980s and 1990s. Noise and health concerns began to emerge in 2003, as we shall shortly describe. As we summarised in Chapter 1, early opposition to windfarms in Australia and elsewhere concentrated almost entirely on NIMBYist ‘we don’t like the sight of them’ concerns, ideological recoil by climate-science deniers (for whom turbines were totemic reminders of green values), and confected alarm about the deaths of even small numbers of non-endangered birds and bats.

Health concerns were either non-existent or entirely marginal in these early years. We looked in vain for any pre-2004 Australian references to health and noise concerns in the parliamentary submissions and blog posts of anti-wind groups. There were 37 windfarms operating in Australia in 2010 when Peter Mitchell set up the Waubra Foundation (see Chapter 6) and began to spread alarm about health issues. At only two of these farms were there any previous records of complaints about noise or health: at Toora in 2004, which we describe in detail below, and at Windy Hill in far north Queensland, which received a complaint from one person in 2001. If there had been more complaints in this era, anti-windfarm advocates would surely have done all they could to amplify these early examples in an effort to stress that noise had been an issue for residents living near windfarms for many years.

A list of 78 international ‘professionals’ who have made statements about their concerns about windfarms appears to confirm this pattern. The list, reproduced on several anti-windfarm websites around the world, shows the year in which each of the 78 first voiced their concerns.3 The earliest dates on the list are Amanda Harry and David Iser (see below), who first expressed concern about wind turbines in, respectively, 2002 and 2004. Of the 78 professionals, 69 (88.5 percent) are from English-speaking nations (Canada, the USA, New Zealand, Ireland and the UK), with the remainder being from six European nations. Wind turbines and health issues have apparently drawn little interest in nations that don’t speak English (see more on this in Chapter 3).

The Harry report

An unpublished report written by an English doctor, Amanda Harry, is frequently described by wind turbine opponents as the first known report of health ill-effects from wind turbines. The report describes data gathered in 2003 on self-reported symptoms in 39 residents living near unnamed English windfarms. Curiously, the report does not appear to have been produced until 2007, four years after the data were collected.4 The Daylesford and Districts Landscape Guardians in Victoria were then quick off the mark, referring to Harry’s report in a 2007 submission opposing a windfarm at Leonards Hill.5 It is unsurprising that this abject report was never published. It has nothing even resembling a study design that would reach even the lowest standard of evidence acceptable in science. Harry’s description of her research methods consists of this simple statement:

All people involved in this survey were contacted either by phone or in writing. Questionnaires were completed for all cases. Questionnaires were sent to people already known to be suffering from problems which they felt was due to their proximity to wind turbines. The identity of the people questioned has been withheld in order to maintain confidentiality. The respondents were from a number of sites in the UK – Wales, Cornwall and the north of England.

The report then consists of tables listing the subjects’ responses to a simple questionnaire. Eighty-one percent of her sample reported health problems that they attributed to the turbines. The most frequently reported health problems were migraine (26 percent), depression (24 percent), tinnitus (22 percent), hearing loss (18 percent), and palpitations (16 percent). As we will discuss in Chapter 5, each of these problems is very common in all communities, regardless of whether they are located near a windfarm or not.

We are told nothing about how Harry located her informants, but can only assume that there must have been some network of people opposed to windfarms that she accessed or perhaps may have been affiliated with herself. She gives no explanation of what motivated or stimulated her to write her report. She did not interview any comparison group of people living near windfarms who did not attribute common problems like hearing loss or sleep disturbance to wind turbines, nor did she interview people who did not live anywhere near a windfarm to assess the prevalence of these conditions among them. These elementary omissions prevent any speculation about whether her respondents had a higher prevalence of the named health problems than others.

In a remarkable ‘pot calling a kettle black’ statement, Harry wrote in her conclusion that:

acoustic experts have made statements categorically saying that the low frequency noise from turbines does not have an effect on health. I feel that these comments are made outside their area of expertise and should be ignored.

Harry, a general practitioner with no acoustic expertise, wrote this statement just one paragraph after stating categorically, ‘I think it is clearly evident from these cases that there are people living near turbines who are genuinely suffering from health effects from the noise produced by wind turbines.’

The Waubra Foundation website headlines Harry’s report as ‘ground-breaking’, a word windfarm opponents are very fond of using.

The Toora report

In Australia, David Iser, a doctor practising in the Foster-Toora district east of Melbourne, produced an unpublished report6 in April 2004 after distributing 25 questionnaires to households within two kilometres of the local 12-turbine, 21 MW Toora windfarm, which had commenced operation in October 2002. Nineteen questionnaires were returned, with 11 respondents reporting no health problems. Iser’s report consists of just two paragraphs and three dot points summarising his findings. Three respondents reported what Iser classified as ‘major health problems, including sleep disturbances, stress and dizziness’. The remaining five reported what Iser categorised as ‘mild problems’, which included the decidedly unorthodox health problem of ‘concern about property values’. Iser forwarded copies of his report to the local shire council and to several Victorian politicians.

Like that of Harry, Iser’s report provides no details as to how the sample was selected, whether written or verbal information accompanying the delivery of the questionnaire may have primed respondents to make a connection between the wind turbines and health issues, whether those who reported ill effects had previous histories of the reported health problems, nor whether the self-reported prevalence of these common problems was different from that which would be found in any age-matched population in a similar rural community nowhere near a windfarm.

In the ten years between the commencement of operation of the first Esperance windfarm in Western Australia and the end of 2003, when the Harry and Toora reports began to be highlighted by windfarm opposition groups, 12 more windfarms commenced operation in Australia. In that decade, besides the two complainants from Toora, we are aware of only one other person, living near the north Queensland Windy Hill windfarm, who complained of noise and later health problems soon after operation commenced in 2000. Importantly in that decade, five large-turbine windfarms at Albany, Challicum Hills, Codrington, Starfish Hill and Woollnorth Bluff Point commenced operation but never received any complaints. An aside in a press report from September 2004 noted that ‘some objectors [to windfarms] have done themselves few favours by playing up dubious claims about reflecting sunlight, mental health effects and stress to cattle.’7 In 2006, a windfarm in Wonthaggi, Victoria, received some ten complaints (but has received none since). With these exceptions, all other health and noise complainants (n=116) first complained after March 2009. As we will discuss in Chapter 5, the nocebo and ‘communicated disease’ hypotheses would predict this changed pattern and ‘contagion’ of complaints, driven by increasing community concern. Sixty-nine percent of windfarms began operating before 2009, yet the majority of complaints (90 percent) until 2013 were recorded after this date. So what happened from 2009 to make noise and health complaints escalate?

Nina Pierpont declares ‘wind turbine syndrome’

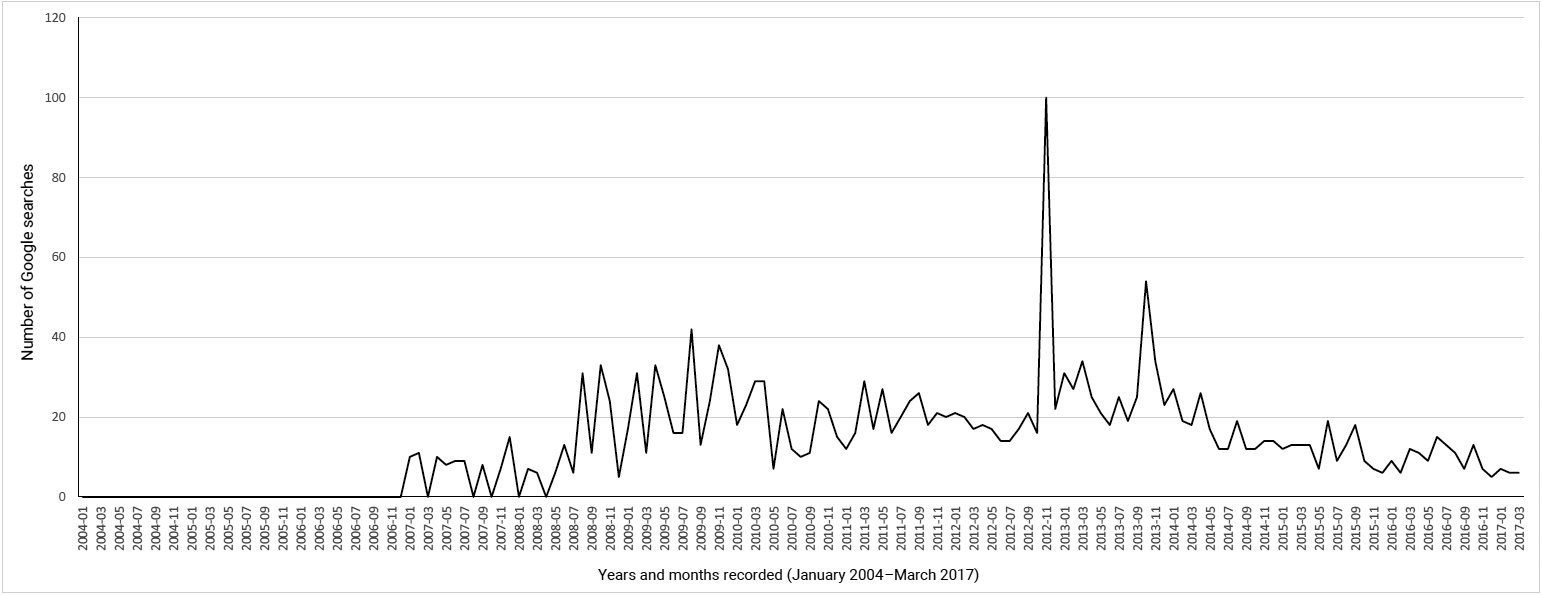

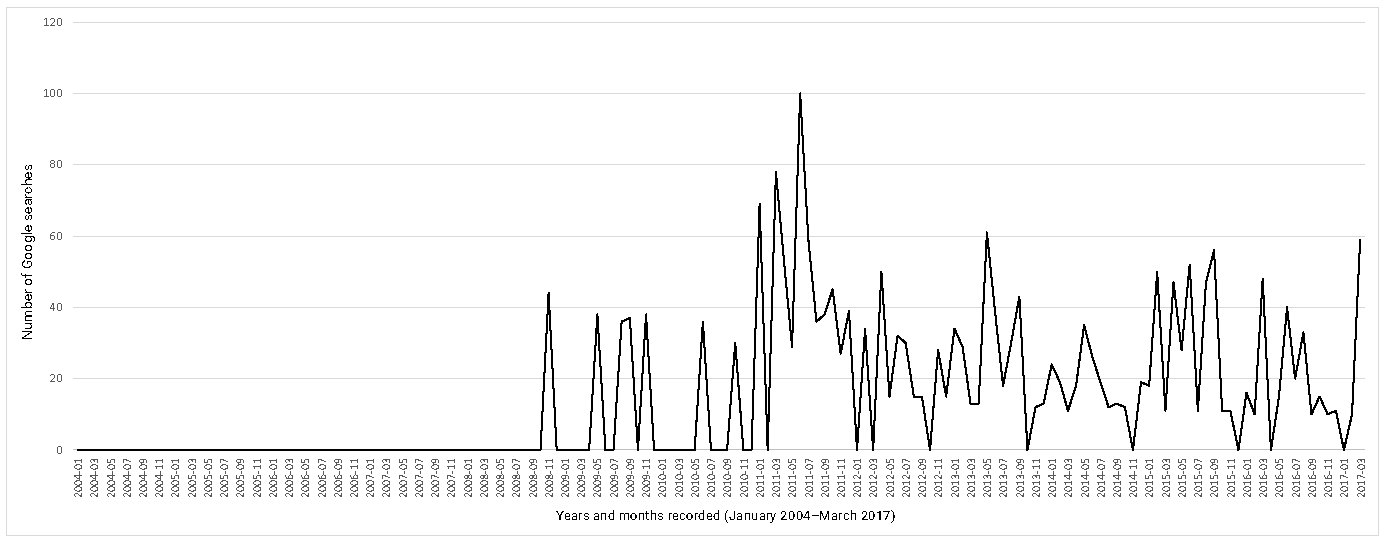

The increase from 2009 (see Figure 2.1) in internet mentions of ‘wind turbine syndrome’ followed publicity given to a self-published book titled Wind turbine syndrome: a report on a natural experiment by a US paediatrician, Nina Pierpont. The book was published by K-Selected Books, a vanity press run by Pierpont and her husband, Calvin Luther Martin (see below), who edited the book.8 K-Selected Books appears to have only two other titles in its stable, both of them by Martin.9

Pierpont and Martin had generated publicity for the alleged effects of wind turbines prior to her book being published. In August 2005 a local newspaper in upstate New York reported that the Noble Environmental Power Company was complaining that Pierpont and Martin were misleading the public. The pair had addressed a meeting at which they had made statements about low frequency noise being linked to mad cow disease (i.e. bovine spongiform encephalopathy or BSE). BSE is caused by cattle being fed a protein supplement made from meat and bone meal. They were also publicising the claims of a Wisconsin farmer who alleged that ‘stray voltage’ from a windfarm was killing his cattle. Martin told the reporter, ‘within five or six months of the wind turbine coming in, 14 cows died of cancer. Autopsies showed they had black livers … heifers were born with monstrous heads and no eyes … his neighbour lost 350 cows’.10

Pierpont’s reputation among her followers as an authority on ‘wind turbine syndrome’ derives from her book, in which she describes wind turbine syndrome as including:

sleep disturbance, headache, tinnitus, ear pressure, dizziness, vertigo, nausea, visual blurring, tachycardia, irritability, problems with concentration and memory, and panic episodes associated with sensations of internal pulsation or quivering when awake or asleep.11

It is not clear whether a person needs to experience all of these symptoms, most of them, or only some to be a candidate for the condition.

Pierpont describes the health problems of just ten families (38 people, including 21 adults and 17 children) living in five different countries who once lived near wind turbines and who were convinced the turbines had made them ill. She interviewed 23 of these people, who provided proxy reports for those in their families whom she did not interview. With approximately 314,000 turbines12 worldwide today and uncounted hundreds of thousands of people living around these, her sample is tiny, before we even get to the many elementary problems with how she selected them and how she conducted her research.

So what are some of the problems with her research that any even basically competent independent reviewer would raise? First, there’s the glaring problem of subject selection bias. Pierpont says nothing in the book about how the families she interviewed were selected. She writes, ‘I chose a cluster of the most severely affected and most articulate subjects I could find’. So how were these people found? Were they obtained via networks of anti-wind groups that already blamed windfarms for their health problems? We are not told.

Figure 2.1a Google Trend worldwide data ‘wind turbine syndrome’, 8 March 2017.

Figure 2.1b Google Trend Australian data for‘wind turbine syndrome’, 8 March 2017.

However, we know that Pierpont spread word about her study through anti-windfarm websites, where she advertised specifically for people who attributed their health problems to windfarms. This meant that her informants were self-selected people who were seeking out and perhaps actively participating in online anti-windfarm forums. They were people who already believed that they were being harmed by wind turbines and so would understandably have had antipathy toward them.

Moreover, her recruitment notice let them know that she was conducting the study with a foregone conclusion in mind: ‘one of the purposes of the study is to influence public policy, around the world, to ensure the proper medically responsible siting of wind turbines.’ Her study was never going to report anything other than the voices of people who knew that the symptoms they experienced were all down to living near windfarms.

Laughably, the notice stated that her study ‘will be published in a leading clinical journal in the next 12 months’. No paper from her study has ever been published in any ‘leading’ journal, nor, as far as we have been able to tell, in any journal.

Why did she choose ‘articulate’, self-nominating subjects and not randomly selected residents living near windfarms? More fundamentally, why did she not make any attempt to investigate controls (people also living near turbines who do not report any illness or symptoms they attribute to turbines, and others experiencing similar symptoms who did not live anywhere near a windfarm)?

Amazingly, she interviewed all her informants by phone and so did not medically examine any of them. Only four families provided medical records for some of their members. However, these are not explicitly referenced in her book. When family members gave proxy reports about others in their family, she does not explain which family members she interviewed, nor consider questions of accuracy in the accounts given by highly motivated informants who were opposed to windfarms. Indeed, she blithely notes that she rejected one informant because she suspected the person of having an ulterior motive for doubting the negative effects of wind turbines (‘In other families, excluded from the analysis, one spouse was clearly committed to staying in the house and minimized what the other spouse said.’) Only those singing from the same song sheet were included, apparently.

Pierpont provides pages of information on her informants’ claims about their own and their families’ health while living near turbines. She also provides summaries of the prevalence of various health problems in these families prior to the arrival of the turbines. These are revealing. A third of the adults had current or past mental illness and a quarter had pre-existing migraine and/or permanent hearing impairment. Six had pre-existing continuous tinnitus. Eighteen had a history of motion sickness. One even had Alzheimer’s disease, in addition to an unspecified mental illness.

All this suggests an absence of even the most rudimentary understanding of the design of disease-investigation studies. Her ‘study’ purports to be a scientific report on human subjects. Nowhere in her book is there any mention of her work having been reviewed or accredited by any human ethics committee. Any researcher in an accredited academic institution doing what she did without such authorisation would be disciplined and probably dismissed. No respectable research journal would ever consider publishing a study without such ethics authorisation.

In summary, her entire ‘study’ was based on accounts provided to an investigator who was already committed to the view that wind turbine exposure caused health problems. She interviewed aggravated informants selected by an unknown process, and excluded at least one respondent who ‘minimized’ accounts of symptoms given by another in their family. Her informants were firmly convinced that wind turbines were harming them, speaking to a researcher who was of the same view.

Her book states that her research was peer-reviewed. We discover that this means she sent her manuscript to people she selected and then published some of their responses in the book, including a four-word ‘review’ by the University of Oxford’s Lord Robert May (‘Impressive. Interesting. And important.’).13 May’s subsequent public silence on the issue may suggest he had second thoughts afterwards. Predictably, all of the quoted reviewers said her study was important (one tends not to publish negative reviews in a self-published book). But as a ‘peer review’ process this is frankly laughable. It is peer review in the way that publishers add selected glowing snippets about a book to the back-cover blurb. If only independent peer review was simply a matter of authors selecting their own reviewers and publishing those that were most complimentary!

Calvin Luther Martin

Pierpont’s husband, Calvin Luther Martin, is a former academic historian who is aggressively opposed to windfarms, to put it mildly. In an outline for a planned book on fighting the wind industry published five months before Pierpont’s own book, he extolled the tactics of Martin Luther King, Jr.14 Martin never seems to have written the book he outlined, but the lengthy document provides many extraordinary insights into his disposition. He commences by stating, ‘I’ve been fighting the wind bastards well over four years. Four years devoted to almost nothing else.’ Far from being detached observers and analysts, the Pierpont-Martin household was a hotbed of seething contempt for wind turbines and the industry.

Martin continues:

I am no longer an academic. I’m a writer. Writers write to convey something in the most appropriate language for the matter at hand. For wind energy, the most appropriate language is profanity, vulgarity, and obscenity. The louder the better. These are not honourable people. Wind energy is not an honourable enterprise. Big Wind is obscene, profane, and vulgar.

A couple of chapter outlines give a good sense of his disposition:

Chapter 3. Real evidence doesn’t work. The wind sharks fabricate their own, using whorish little companies to perform noise measurements and do environmental impact studies, including bird and bat studies. Companies often consisting of four guys with sweaty balls and BS degrees from nondescript bullshit state colleges, from which they graduated three years ago. But they’ve got a website and stationery and PO Box – and they’re rarin’ to get those permits for Big Wind. Give me a break! …

Chapter 7: Wind energy is bullshit. Nitwits who begin their case by telling the local newspaper, ‘Well, Gee, we fully support renewable energy, including wind energy, and we feel wind turbines are marvellous so long as they’re placed in the right spot’ – nitwits who start off their campaign with this are doomed. Wind energy, folks, is horseshit. From beginning to end. Fairy Godmother economics. Right up there with the Easter Bunny. This is 4.5 years of reading thousands of documents, yes, much of it on the physics and economics of wind energy. (By the way, my BA is in science and I did several years of graduate training in hard-core science. Science doesn’t scare me.) Wind energy, when subjected to Physics 101, falls apart. It’s laughable. Buy a textbook in introductory physics. Start reading.

Eight years after the publication of Pierpont’s book, her concocted ‘disease’ has received no recognition in international medicine. It has never been recognised by any authoritative health or medical agency. It appears nowhere in the International Classification of Diseases and, most tellingly, there appear to be no examples of case reports of the alleged syndrome in any reputable indexed, peer-reviewed medical journal (see Chapter 3).

‘Vibroacoustic disease’

After wind turbine syndrome, ‘vibroacoustic disease’ (or VAD) is probably a very close silver medallist in the race for the weakest evidence. Like wind turbine syndrome and ‘visceral vibratory vestibular disturbance’ (what Pierpont describes as ‘a sensation of internal quivering, vibration, or pulsation accompanied by agitation, anxiety, alarm, irritability, rapid heartbeat, nausea, and sleep disturbance’), VAD is not recognised by any accredited or reputable global health agency and is nowhere to be found in the International Classification of Diseases.

But if you go hunting in cyberspace for VAD, you will find plenty of anxiety-provoking material. In 2012 when I was researching the issue for a paper described below,15 Google returned 24,700 hits for ‘VAD and wind turbines’. There is also a small scientific literature on the topic, overwhelmingly dominated by the work of a small Lisbon-based research group. Two of these authors describe vibroacoustic disease as ‘a whole-body, systemic pathology, characterized by the abnormal proliferation of extra-cellular matrices, and caused by excessive exposure to low frequency noise.’16 The group argues that VAD is found in occupations routinely exposed to low frequency noise such as aircraft technicians, commercial and military pilots and cabin crewmembers, ship machinists, restaurant workers, and disc jockeys.

In the research paper I wrote with my colleague Alexis St George, we investigated the extent to which vibroacoustic disease and its alleged association with wind turbine exposure had received scientific attention, the quality of that association, and how the claimed association gained traction among windfarm opponents.17 Our search of the scientific literature located 35 research papers on VAD, with precisely – wait for it – none of them reporting on any association between VAD and wind turbines. Of the 35 papers we located at the time on VAD, 34 had a first author from the same Portuguese research group. Seventy-four percent of citations of these papers were self-citations (where the members of the research team re-cited their own work over and over again). Citing one’s own work is acceptable and often important and unavoidable in science. But average self-citation rates in science are around 7 percent of a paper’s references. So the ‘disease’ of VAD has received virtually no scientific recognition beyond the group who coined and promoted the concept. With none of the papers containing any reference to wind turbines, we then set out to hunt down the origins of the claim. We found it had first been asserted in a May 2007 press release by the same Lisbon group about a conference paper they were to give at a conference in Istanbul that month. So what was the evidence they produced?

The Lisbon researchers wrote about a 12-year-old boy who lived (along with many others in the vicinity) near a windfarm and who had ‘memory and attention skill’ problems in school and ‘tiredness’ during physical education activities. These are of course both very common problems in school children the world over. They are problems which may be caused by a very wide variety of factors. The measured infrasound levels in the boy’s house were said to be high. The authors concluded unequivocally that the boy’s family ‘will also develop VAD should they continue to remain in their home.’ Their press release stated that their findings ‘irrefutably demonstrate that wind turbines in the proximity of residential areas produce acoustical environments that can lead to the development of VAD in nearby home-dwellers’ (our emphasis).

It is impossible to understate the abject quality of this unpublished ‘study’, which was delivered at a conference but has never surfaced in a peer-reviewed journal. There was no control group, just one ‘sick’ subject, no apparent medical examination of the boy, and no consideration given to any other possible cause of his tiredness.

Factoids are questionable or spurious statements presented as facts, but which have no veracity. They attain popular acceptance as facts because of their repetition, not because of their truth. With some 24,700 mentions in cyberspace, the connection between VAD and wind turbines went viral and stoked the confirmation biases of those utterly committed to the view that turbines are harmful. VAD is now commonly included in submissions to governments by anti-windfarm activists. The term ‘vibroacoustic disease’ resonates with a portentousness that may foment nocebo effects (see Chapter 5) among those who hear about it and assume it to be an established disease classification acknowledged by medicine. The relationship between VAD and wind-turbine exposure is thus a classic example of a contemporary health factoid, unleashed by a press release on the basis of an uncontrolled case study, then megaphoned through cyberspace. By naming and publicising such questionable ‘diseases’, windfarm opponents seek to pull what are often extremely common symptoms, such as fatigue, inattention, sleeping problems, high blood pressure and mental health problems, into a memorable, quasi-scientific-sounding ‘non-disease’. Vibroacoustic disease is a prime example.18

In October 2016, the Sydney radio broadcaster Alan Jones (see Chapter 6) interviewed one of the Portuguese group, Dr Mariana Alves-Pereira, about her work on VAD and wind turbines.19 Jones commented of her research papers that ‘none of them have been disputed’, to which Alves-Pereira rapidly concurred, ‘No, they haven’t,’ and stated that her findings were ‘indisputable’. Perhaps she had forgotten our critique20 and those of others. We cited some of the latter when we replied21 to a letter defending her work that she co-authored in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health,22 which had published our original critique of VAD. For example, in his review of their work, Geoff Leventhall wrote: ‘The evidence which has been offered [by the Lisbon group] is so weak that a prudent researcher would not have made it public’23; H.E. von Gierke observed that: ‘“vibroacoustic disease” remains an unproven theory belonging to a small group of authors and has not found acceptance in the medical literature’24; and the UK’s Health Protection Agency noted that the ‘disease itself has not gained clinical recognition’.25

Leventhall concluded his review thus:

One is left with a very uncomfortable feeling that the work of the VAD group, as related to the effects of low levels of infrasound and low frequency noise exposure, is on an extremely shaky basis and not yet ready for dissemination. The work has been severely criticised when it has been presented at conferences. It is not backed by peer reviewed publications and is available only as conference papers which have not been independently evaluated prior to presentation.26

One more try?

We’ve described the lack of recognition that wind turbine syndrome and vibroacoustic disease have been met with since their advocates began pushing for their recognition. Apparently undeterred, two activists against windfarms have attempted to have another high falutin’, scientific-sounding name adopted for the same phenomenon: ‘adverse health effects in the environs of industrial wind turbines’, or AHE/IWT.

Two doyens of the anti-windfarm movement, Robert McMurtry and Carmen Krogh, have attempted valiantly to promote diagnostic criteria for AHE/IWT, first in a non-indexed journal in 201127 and twice again in 2014.28 As of 6 May 2017, interest in McMurtry’s 2011 paper had generated a whole nine downloads in the 68 months since it was published (see Figure 3.6).

Their sweeping ‘catch-all’ criteria have been severely criticised by others.29 The case definition allows at least 3264 and up to 400,000 possibilities for meeting second- and third-order criteria, once the limited first-order criteria are met. Institute of Medicine guidelines for clinical case definitions were not followed. The case definition has virtually no specificity and lacks scientific support from peer-reviewed literature. If applied as proposed, its application will lead to substantial potential for false-positive assessments and missed diagnoses. Virtually any new illness that develops or any prevalent illness that worsens after the installation of wind turbines within 10 kilometres of a residence could be considered AHE/IWT if the patient feels better away from home.

Silent and sickening? Infrasound

No medically plausible link or pathway has been found between infrasound exposure and any of the 200-plus illnesses claimed. The elephant in the room is that the level of infrasonic exposure in ship engine rooms, driving a car with the windows down, or living near a surf beach are vastly greater, yet there is no ‘surf coast syndrome’. In other words, the claimed dose / response makes no sense at all. This is homeopathy come to acoustics.—Roly Roper30

As we wrote in the Introduction, if you have ever been up close to a windfarm and you have not already taken a dislike to them, the sound they emit is neither significant nor offensive. Anyone without an anti-windfarm agenda who has been near a windfarm or single turbine will have found the sound utterly unremarkable. In an amateur video made by a German girl for a school project, we have an elegantly simple demonstration of the sound of a wind turbine compared with sounds she encounters every day in her township.31 When compared with the range of noises most of us encounter every day of our lives, audible windfarm noise is an utter non-event. If someone said to you, ‘Hear the sound of that wind turbine? It’s unbearable. It’s infuriating. It’s impossibly loud,’ you would think you were in the presence of a very precious petal. Indeed, in Chapter 5 we describe research that shows that those who complain about even micro wind turbines tend to have ‘negative’, complaining personalities. If they react this way to the gentle, barely noticeable whoosh-whoosh of a turbine, how would they react if they lived, as do billions of the world’s population, surrounded by the ever-present din of a city, or to the soundscape of the many occupations in which the noise levels make those near windfarms sound like the silence of a library reading room? However, while anti-windfarm writings frequently refer to the intolerable audible sound of wind turbines (see Chapter 3 for examples of some of the florid language commonly used), they more often demonise sub-audible infrasound as the silently sickening factor responsible for the tsunami of symptoms and diseases set out in Appendix 1.

These efforts find fertile ground in a long history in popular culture and science of animating examples of the dangers of unusual sounds. Steve Goodman’s 2012 book Sonic warfare: sound, affect, and the ecology of fear catalogues many examples of how sound has been used to create sonic ‘weapons’. As the publisher’s blurb states:

Sound can be deployed to produce discomfort, express a threat, or create an ambience of fear or dread – to produce a bad vibe. Sonic weapons of this sort include the ‘psychoacoustic correction’ aimed at Panama’s Manuel Noriega by the US Army and at the Branch Davidians in Waco by the FBI, sonic booms (or ‘sound bombs’) over the Gaza Strip, and high-frequency rat repellents used against teenagers in malls.

The idea that something you can’t hear, constructed by avaricious faceless transnational corporations, is silently eroding your health ticks many boxes for those bewildered by the pace of modern life. Fragments of half-remembered news about the ability of infrasound to terrorise exposed crowds and shake buildings feeds the idea that infrasound from windfarms may well do the same thing.

Infrasound (the ‘infra’ prefix means ‘below’, so here indicates sound below audible levels) generated as turbine blades turn in the wind is at the centre of the allegations about windfarms. It is therefore important to understand what it is and the claims being made about it.

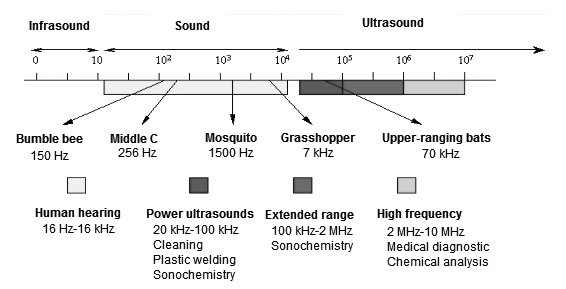

Figure 2.2 Spectrum of sound by frequency (Hz to kHz). Source: Atav 2013.

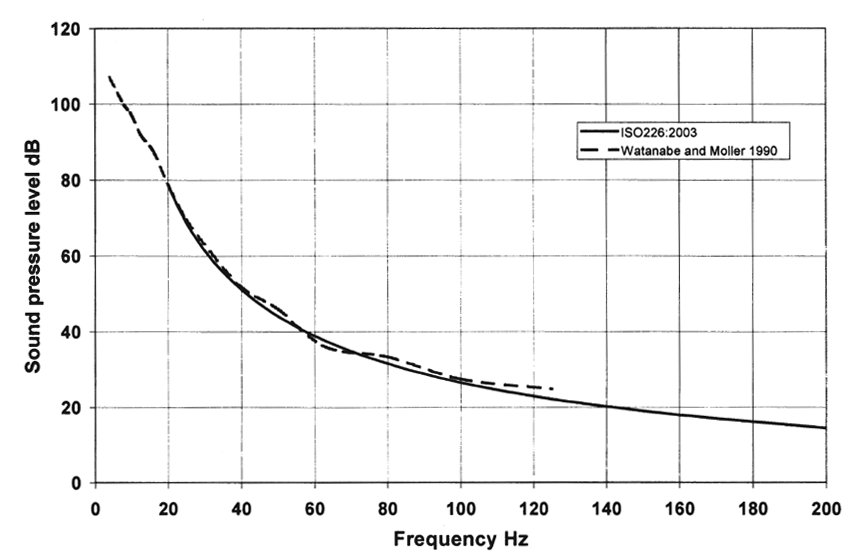

Figure 2.3 Hearing thresholds for a young adult. Source: Leventhall 2009.

Decibels and hertz

First, a brief summary of how acousticians talk about sound. Two terms are always found in discussions about sound: decibels (dB) and hertz (Hz). Decibel numbers refer to the loudness (or pressure) of sounds: the higher the decibel, the louder the sound. A whisper is around 30 dB while a loud motorbike can be between 100 and 110 dB. You can download free decibel-meter apps for mobile phones and tablets that will allow you to measure the decibel levels of any sound in your environment. As I type this, I am listening to music being played softly on my desk which is between 60 and 70 dB. If I turn the volume up to its maximum, my decibel meter shows 110 dB, which is unpleasant except when I might purposefully seek it out, such as at a rock venue. In a silent kitchen, my refrigerator rates between 45 and 50 dB when its motor switches on to stabilise its temperature.

All sounds also have a certain pitch or frequency. This is measured by the number of waves or cycles that a sound makes per second (cps), measured in hertz (Hz). Figure 2.2 shows the spectrum of sound, showing human inaudible infra- and ultra-sound at either end of the scale, with the sound range audible to humans in-between. Figure 2.3 shows hearing thresholds (standardised for a young adult).

Infrasound is sound between 1 and 20 Hz, which as can be seen from Figure 2.2 is inaudible except at very high volume. People would very rarely be exposed to infrasound at such volume (exceptions might include a volcanic eruption, a violent electrical storm, or at very close exposure to a very loud engine). Infrasound is generated by a variety of mechanical sources, of which wind turbines are just one. Others include power stations, industry generally, motor vehicle and other engines, compressors, aircraft, ventilation and air-conditioning units, and loudspeaker systems.32 Everyone living in an urban environment is bathed in infrasound daily for most of their lives. Typically, urban residents are exposed to 50 to 65 dB(G) of infrasound most of the time due to traffic, air conditioning, heating fans, subways and air traffic. If they live near airports, they can be exposed to far more. As I sit at my inner-Sydney desk writing this book I’m exposed to both audible noise and infrasound from the planes that pass some 200 to 300 metres over my house, sometimes many times an hour, on their way in and out of Sydney’s airport; the sound of passing road traffic on a quite busy road 100 metres from our house; the sounds of trains passing some 200 metres further than the road; and the sub-woofer in the music system I listen to as I write.

Infrasound is also generated by natural phenomena. Human heartbeat, breathing and coughing produce infrasound,33 so we all live through every day of our lives constantly exposed to it. Other natural sources include rare occurrences like volcanoes and earthquakes that most of us will never experience, but also very common sources like ocean waves, surf and air turbulence (i.e. wind itself) that countless millions, if not billions, are exposed to on most days. Anyone living close to the sea is subjected to constant infrasound from ocean waves. Surf sounds 75 metres from the beach are about 75 dB(G), yet tens of millions of residents living near the sea do not experience symptoms of illness from this exposure. Indeed, many deliberately holiday near beaches partly for the love of the sound of the sea at night. Coastal real estate trades at a premium worldwide. Riding in a car with the windows down exposes occupants to infrasound, and a child on a swing may experience infrasound around 0.5 Hz at 110 dB.34 This level is much higher than that emitted by wind turbines. Table 2.1 shows a range of data published by the Ministry for the Environment, Climate and Energy of the German state of Baden-Württemberg collected between 2013 and 2016 on low frequency noise and infrasound from six different wind turbines and other commonly encountered noise sources. It can be seen that many common, everyday sounds are comparable and sometimes greater than those recorded for wind turbines (e.g. street noise heard from a balcony, the interiors of cars, and beaches).

| Source/situation | G-weighted (audible sound) level in dB(G)* | Infrasound 3rd octave level 20 Hz in dB* | Low-frequency 3rd octave levels 25-80 Hz in dB* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind turbines | Wind turbine on/off | Wind turbine on | Wind turbine off |

| WT1 | 700 m: 55–75/50–75 150 m: 65–75/50–70 | 150 m: 55–70 | 150 m: 50–55 |

| WT2 | 240 m: 60–75/60–75 120 m: 60–80/60–75 | 120 m: 60–75 | 120 m: 50–55 |

| WT3 | 300 m: 55–80/50–75 180 m: 55–75/50–75 | 180 m: 50–70 | 180 m: 45–50 |

| WT4 | 650 m: 50–65/50–65 180 m: 55–65/50–65 | 180 m: 45–55 | 180 m:40–45 |

| WT5 | 650 m: 60–70/55–65 185 m: 60–70/55–65 | 185 m: 50–65 | 185 m: 45–50 |

| WT6 | 705 m: 55–65/55–60 192 m:60–75/55–65 | 192 m: 55–65 | 192 m: 45–50 |

| Road traffic | |||

| Würzburg urban balcony | 50–75 | 35–65 | 55–75 |

| Würzburg urban living room | 40–65 | 20–55 | 35–55 |

| Motorway A5, 80 m |

75 | 55–60 | 60–70 |

| Motorway A5, 260 m |

70 | 55–60 | 55–60 |

| Interior car, 130 km/h |

105 | 90–95 | 75–95 |

| Interior minibus, 130 km/h |

100 | 85–90 | 80–90 |

| Urban background | |||

| Museum roof | 50–65 | 35–55 | Up to 60 |

| Friedrichsplatz | 50–65 | 35–50 | Up to 60 |

| Interior | 45–60 | 20–45 | Up to 55 |

| Residences | |||

| Washing machine | 50–85 | 25–75 | 10–75 |

| Heating (oil & gas) |

60–70 | 40–70 | 25v60 |

| Refrigerator | 60 | 30–50 | 15–35 |

| Rural with wind 6 m and 10 m per second | |||

| Open field, 130 m from forest |

50–65 / 55–65 | 40–70 / 45–75 | 35–40 / 40–45 |

| Edge of forest | 50–60 / 50–60 | 35–50 / 45–75 | 35–40 / 40–45 |

|

Forest |

50–60 / 50–60 | 35–50 / 40–45 |

35–50 / 35–40 |

|

Sea surf | |||

| Beach, 25 m away |

75 | 55–70 | Not reported |

| Rock cliff, 250 m away |

70 | 55–65 | Not reported |

Table 2.1 Wind turbine and other sources of infrasound and low frequency noise. Source: Landesanstalt für Umwelt, 2016. *G-weighting measures infrasound, and A-weighting measures audible sound. The G-weighted level is that given by a sound level meter with a G-weighting filter in it.

The fact that wind itself generates infrasound is of particular significance to claims made that infrasound generated by wind turbines is noxious. In a Polish research paper published in 2014, the authors set out to measure infrasound from wind turbines and to compare that with naturally occurring infrasound from wind in trees near houses and from the sound of the sea in and around a house near the seaside.35 The researchers used the average G-weighted level(LGeq) over the measurement period. This is the standardised measurement of infrasound and approximately follows the hearing threshold below 20 Hz and cuts off sharply above 20 Hz. The infrasound levels recorded near 25 100-metre high wind turbines ranged from 66.9 to 88.8 LGeq across different recordings, while those recording infrasound in noise from wind in a forest near houses ranged from 59.1 to 87.8 LGeq and the recordings of sea noise near seaside houses ranged from 64.3 to 89.1 LGeq . Infrasound levels were thus very similar across the three locations. The peak 88.8 LGeq was recorded very close to the turbines – virtually directly under the blades. The lower 66.9 LGeq was 500 metres away, which is more like the distances experienced by the nearest residences to turbines. Similarly, for the other sources of infrasound, the highest levels were recorded nearest to the source.

Wind is of course a prerequisite for wind turbines to turn. Here, the Polish authors noted that ‘natural noise sources … always accompany the work of wind turbines and in such cases, they constitute an acoustic background, impossible to eliminate during noise measurement of wind turbines.’ This is a fundamentally important point: wherever there are wind turbines generating infrasound, there is also wind itself generating infrasound, and it is impossible to disentangle the two. Indeed, every time I’ve been near wind turbines, easily the most dominant sound has been that of the wind buffeting my ears.

A South Australian study reported that infrasound measured near the ears of a person walking was ‘similar in dominant frequency to that measured at the houses near wind farms’.36 The infrasound near the walker’s ears was ‘significantly higher in level, with levels measured to be 10 dB higher than the highest levels measured near windfarms at 1.5 kilometres away where residences may be located.’ In 2013, the South Australian government’s Environmental Protection Authority and Resonate Acoustics measured infrasound in a variety of urban and rural settings. The latter included locations near and well away from windfarms. They reported that in urban settings, measured infrasound ranged between 60 and 70 dB. In fact, at two locations, the EPA’s own offices and an office with a low frequency noise complaint, building air-conditioning systems were identified as significant sources of infrasound. These locations exhibited some of the highest levels of infrasound measured during the study.

The authors concluded:

This study concludes that the level of infrasound at houses near the wind turbines assessed is no greater than that experienced in other urban and rural environments, and that the contribution of wind turbines to the measured infrasound levels is insignificant in comparison with the background level of infrasound in the environment.37

To summarise, while prolonged exposure to extreme levels of infrasound can have deleterious effects on humans when it is very loud and very prolonged, wind turbines generate far less than other sources are known to make. The evidence remains the same: some people near wind turbines find the audible noise annoying, some of them find it stressful, and some of them lose sleep due to stress.

247 symptoms and diseases, and counting

While it went nowhere fast in the health and medical fields, Pierpont’s book precipitated an avalanche of claims about symptoms and diseases being caused or aggravated by wind turbines. From the time I first became interested in this phenomenon, I began to notice a wide variety of such claims on the internet. I was curious to see how many I could find and in January 2012 I set out to compile a list, including sources, most of which were the websites of opponents of windfarms and submissions they had made to governments. Within an hour or two of searching I had found nearly 50 and today the number has grown to an astonishing 247, which are listed in Appendix 1.

The Australian cartoonist ‘First Dog on the Moon’ found the list the perfect stimulation for a giant cartoon illustrating 244 of these horrors.38 He then wrote and recited an ode to them for his then weekly radio slot on ABC Radio National.39 Opponents of wind turbines, however, have reacted badly to the list, which as of September 2017 had been viewed 5700 times on the University of Sydney’s eScholarship repository. These opponents argue that by publishing the list and regularly updating it with new claims as they are found, I am ‘ridiculing’ people who say they are ill. This is a peculiar charge, as it suggests that those who actively publicise these alleged problems want to have it both ways. They continue to publicise the allegations because they wish to promote awareness about the supposed harms being caused. Yet they say that it is disgraceful to compile a list of these complaints as I have done, because it invites ridicule. However, the list is simply a compendium of claims made by others: it is not a list I have somehow ‘made up’. When you read it, you may ask whether you can recall a more diverse collection of threats to humanity. Old Testament accounts of pestilence and plague seem mild compared to the manifold problems attributed to wind turbines. Almost every conceivable health problem has been attributed to windfarms at one time or another – yet many European countries have numerous windfarms without experiencing an epidemic of these symptoms.

Curiously, many of the symptoms on the list are common to similar lists promoted by victims of other highly questionable non-diseases. For example, an article on the frequently described non-disease ‘pyroluria’ lists 72 symptoms including difficulty remembering dreams, inability to think clearly, emotional instability and ‘severe inner tension’, with the author noting that most symptoms are ‘vague, ambiguous and non-descript and could be attributed to virtually any trivial or serious illness’.40 Wi-fi phobics and self-identifying ‘electrosensitives’ also promote very similar symptom lists, with cognitive decline, fatigue, heart palpitations, sleep problems and headaches commonly mentioned.41 What many of these symptoms have in common is that they are common expressions of anxiety. We explore this further in Chapter 5. Of all the doomsday claims we’ve heard about the consequences of living near windfarms, an October 2012 submission by the Buddhist Tharpaland International Retreat Centre in Scotland to the Australian Senate committee convened by John Madigan must take first prize.42 It spells out the full extent of the apocalypse that the authors believe threatens any nation embracing wind power:

- A decline in general public health and wellbeing, including a major increase in cancer, heart disease and immune-deficiency related diseases, entailing illness, suicide and violent crime, adding a further burden on the health system.

- A decline in standards throughout the educational system, due to a degeneration of learning ability, which depends upon the ability to develop concentration.

- The main economic sector within the Scottish economy – tourism – could be wiped out.

- Spiritual centres and communities could be forced to close and disperse.

I do not believe I have ever read a more all-inclusive statement of the alleged perils of windfarms to the very fabric of a nation. I have worked in public health since the mid 1970s. In all this time, I have never encountered anything in the history of disease across the millennia that has been said to cause even a fraction of the problems attributed to windfarms. Other than perhaps the aftermath of a nuclear blast, there is nothing known to medicine that comes close to the morbid apocalypse described by anti-wind groups. Wind power is blamed for ‘numerous serious illnesses and, yes, many deaths, mainly from unusual cancers’,43 which have oddly enough never come to the attention of any coroner. Did you know that wind turbines can cause lung cancer, leukaemia, diabetes, herpes, ‘electromagnetic spasms in the skull’, infertility and the ghastly sounding ‘loss of bowels’? Any very common problem known to affect literally millions if not billions of people across the world (sleep problems, high blood pressure, lack of concentration, forgetfulness, poor performance at school, nosebleeds, muscle twitches) can be explained by exposure to wind turbines. But there are some benefits, too. Those who are overweight can lose kilograms through exposure to wind turbines – while the excessively slim can gain weight! Is this magic? All of these claims can be found in Appendix 1. As my collecting efforts rolled on, I amused myself by googling random health problems. One day I entered ‘haemorrhoids’, and sure enough, there it was too.

People living near wind turbines have been shown to suffer from VAD [vibroacoustic disease] as a result of their exposure to the noise. Stage III is severe and occurs with over 10 years of exposure to LFN. It causes psychiatric disturbances, haemorrhages of nasal, digestive and conjunctive mucosa, nose bleeds, varicose veins and haemorrhoids, duodenal ulcers, spastic colitis, decrease in visual acuity, headaches, severe joint pain, intense muscular pain, and neurological disturbances.44

Animals too

It’s not just humans that are affected. The ever-expanding collection of diseases and symptoms attributed to wind turbines (see Appendix 1) includes many affecting domestic and wild animals. Almost every known malformation in birds and farm animals has been laid at the feet of wind turbines by their critics.

Did you know that ‘seagulls no longer follow the plough in areas near wind turbines … the seagulls have learned that the worms have all been driven away … They must go elsewhere for their food.’ This can happen as far as 18 kilometres from a turbine! Whales have their sonar systems disrupted, chickens won’t lay, and sheep’s wool is poorer in quality. Tragically, a ‘peahen refused to go near a peacock’ and dogs ‘stare blankly at walls’, ignoring their owners.

Other more interesting reports include the extinction of bees; a farmer opining that echidnas (Australia’s iconic spiked monotreme) are disoriented by turbines, causing them to ‘dig up more soil looking for food than before’, and that they could ‘pinpoint the location of their food source much more accurately back then [before turbines were installed]’; and the death in 2009 of ‘more than 400 goats’ from ‘exhaustion’ on an unnamed, outlying Taiwanese island45 – a report still unquestioningly displayed today on the Waubra Foundation website. Four hundred is a nice big round number for dead goats and, oddly enough, it’s the same big round number of goats that allegedly also ‘dropped dead’ in New Zealand.46

In 2013 in Nova Scotia, the Canadian Atlantic province where midwinter temperatures fall to -20 degrees Celsius, a small emu farm closed down. There’s nothing unusual about this. Investment in emu farming was an ill-fated get-rich-quick bubble that burst in Canada over a decade ago. It has been described as a ‘failed industry’.47 But what made this sad story even sadder was that the husband and wife team behind it blamed the closure on wind turbines, saying they had seen many of their birds lose weight and die of ‘stress’. Tellingly, no necropsies were performed on the 20 birds that died, prompting one commenter to write, ‘So they didn’t have necropsies performed on any of the animals? That is extremely irresponsible farming. The department of Agriculture should be called in to inspect for animal cruelty.’48 In emus’ native home of Australia, they don’t tend to be kept in pens and fed on pellets. The birds roam freely around turbines, among sheep and cattle, and never in -20 degrees Celsius weather. Anti-windfarm websites are awash with these astonishing claims that seem to have escaped the relevant authorities. Such catastrophic events would always attract huge attention from government authorities concerned about the possibility of a serious disease outbreak that might threaten a nation’s livestock. As anyone with even a passing familiarity with farming knows, mass or unusual deaths in livestock are of intense interest to governments because of concerns about infectious diseases with the potential to devastate the farming sector, export trade or even animal to human transmission. Concern about diseases like brucellosis, avian influenza and the Hendra virus see authorities swiftly isolate farms and destroy all remaining stock. Massive publicity follows. But when 400 goats unaccountably ‘drop dead’ or a farmer reports decimation of their flock of emus, these same government authorities are nowhere to be seen. Try to find news about government action on such incidents and instead you will only find unverified anecdotes. Try searching for any official corroboration and you’ll be looking for a long time. It must be an international conspiracy of silence, engineered by the wind industry!

‘Wind turbine syndrome’ symptoms are common in all communities

All of the human health problems windfarm opponents attribute to wind turbines occur in every community, regardless of whether they are near windfarms or not. Forty-five percent of people report symptoms of insomnia at least once a week.49 Anxiety and depression are widespread. Getting old? Is your hair turning grey or receding? Perhaps your eyesight, hearing, or balance problems are increasing with age? Are you gaining or losing weight? As we saw earlier (and in Appendix 1), all of these very common ‘problems’ are among those said to be caused by wind turbines. Many of the claims about animals fall into the same category. Yolkless eggs and those without shells are phenomena known to every bird breeder.50 But when such eggs are laid by chickens belonging to someone who doesn’t like windfarms, they can only have been caused by the dastardly turbines. Dogs, horses, sheep or cattle getting listless, skittish, off their food … or anything, really: wind turbines are to blame if you don’t like windfarms. Every day in every country, thousands of people are diagnosed for the first time with one of countless health problems. Most live nowhere near a windfarm. They weren’t having the symptoms that drove them to the doctor a few months ago, and once they have a diagnosis, they start thinking about what might have caused it. If they don’t like the look of windfarms, or if they have been exposed to scary tales about all the things that wind turbines can do, and if they happen to live near a windfarm, then the post hoc ergo propter hoc (‘after therefore because of’) fallacy can powerfully kick in to make sense of their new problem. We explore this further in Chapter 5.

Florid language

Clues about the likely veracity of the claims being made by windfarm opponents can be found in the words they use to describe their experiences. As one wades through claims about the alleged harms caused by wind turbines, it is impossible not to be struck by the propensity of opponents to use language that immediately makes you say, ‘Uh-oh, what’s going on here?’ Let’s consider some examples.

How loud?

If you have a spare couple of hours and the fortitude to watch all 117 minutes of Pandora’s pinwheels, the 2011 home movie made by the open opponent of windfarms Lilli-Anne Green, who gave evidence to the 2015 Senate inquiry about her ‘research’ on windfarms,51 you will hear many truly bizarre statements. The film includes interviews with windfarm opponents in New Zealand and the Waubra district of Victoria. Nobody interviewed has a good word to say about wind energy. There are endless examples of florid language, such as:

‘It was continually like a 737 [jet] about to take off and [it] never did and [it] went on for hour after hour after hour.’

‘Like a train going over a bridge.’

‘A plane that won’t go away.’

‘Someone hiding a bumble bee in your ear.’

‘Sometimes it’s like a jet plane has parked itself above.’

‘Windfarms are tuning forks glued to a hill … they vibrate the ground.’

A witness who gave evidence to the Senate inquiry on 19 June 2015, Charles Barber, stated: ‘I visited them on a very, very windy day; I was out of the car, and within half an hour I felt like I had been at the Rolling Stones for four hours.’52 I spoke with Mr Barber outside the Senate hearings at Sydney’s Parliament House on 29 June 2015 and told him I was curious about his Rolling Stones comparison, as I’d seen them three times, including once from the mosh pit of their February 2003 gig at Sydney’s 2200-capacity art deco Enmore Theatre.

‘Have you ever been to a Rolling Stones gig?’ I asked him. He confirmed he had. But he was unshifting in his comparison. I smiled at him, giving him permission to confess he had used a little rhetorical licence in his testimony. But Mr Barber was not for turning. Having been to hundreds of rock gigs, and having sung in a loud covers band myself for ten years, it was hard for me to know where to go next in such a conversation.

How painful?

Ann Gardner, a prominent opponent living near the AGL-owned Macarthur windfarm in Victoria, drew on some unique experiences to explain how painful the effects of wind turbines can be. She has apparently experienced being inside a microwave oven when it is turned on: she told radio broadcaster Alan Jones on 21 August 2015, ‘I feel like my body’s been cooked in a microwave.’53 Meanwhile her husband apparently knows what it feels like to be repeatedly hit in the head with an axe (‘All of sudden he’s hit by this bolt of pressure as if someone’s chopping him in the back of the head with an axe’).54

Jan Hetherington, another prominent windfarm objector from Victoria, also seems to have had some very violent experiences that she can draw on in describing the sensation.

Alan Jones: You said to me early this morning, ‘I woke up at 4.35 with a very sharp ice pick stabbing on the top of my head …’

Jan Hetherington: Oh yes.

Alan Jones: ‘… behind my right ear.’

Jan Hetherington: Yes.

Alan Jones: ‘This was followed by vibration running through my body, then came the headache in my right temple and right eye. I just had to get out of bed. Unfortunately, there’s no running away from this infrasound. Nothing can stop it.’

Jan Hetherington: That’s right, that’s right, it is terrible … oh it’s hard to talk about it because it’s so, it’s so real, it happens.55

Heartfelt testimonies like these from people claiming to be suffering health problems can never be a substitute for evidence-based assessment of their claims. These accounts can only be an important start to the process of assessing what is going on. And for all the fervour of these personal accounts, one very inconvenient problem quickly emerges. There is no body of case reports – not even a small one – to be found in the medical research literature (see Chapter 3).

We have all at one time or another suspected or believed that a particular symptom is likely to have been caused by something we have eaten or been exposed to, or by some activity we have engaged in. But we are often mistaken. The history of medicine is littered with sometimes highly entrenched, widely accepted beliefs about the cause of particular symptoms that were subsequently discarded when alternative explanations arose from new evidence. When someone tells you passionately and in great detail that they are ill, the social expectation is that we should be empathic, sympathetic, and accept their account. If their account raises doubts or questions, we may be reluctant to forcefully or even tactfully try to repudiate their beliefs about the cause of their illness. Medical sociologists have for decades noted that adopting the ‘sick role’ can confer social advantages on those who say that they are ill.56 These can range from being treated with extra consideration and care by those around you to being exempted from normal family, social and work obligations and even receiving compensation.

When we see people making often highly emotional statements in the media about how much they are suffering, it can be awkward to publicly question whether the accounts they give should be taken at face value. It is bad manners to cast doubt on whether an alleged victim is indeed ill. Questioning a person’s claim that they are being made ill by windfarms is likely to be taken as an affront. They may get angry and claim that they are not being ‘respected’. But concern about being considered insensitive should never cause such questioning to be abandoned. Claims by individuals that they are being made ill from windfarms can be considered from two perspectives. First, we can ask whether those making the claims are genuinely suffering the symptoms they say they are suffering. Second, if we are satisfied that they are, we can ask how reasonable is their explanation that their symptoms are caused by exposure to wind turbines.

In the next chapters, we consider the evidence – or lack of it – for the claims made by windfarm opponents, and look at what the most recent major review of the evidence on windfarms and health says.

1Kelley et al. 1985.

2Martin 2013.

3European Platform Against Wind Farms n.d.

4Harry 2007.

5Wild 2007.

6Iser 2004.

7van Tiggelen 2004.

8Pierpont 2009a.

10Raymo 2005.

11Pierpont 2009a, 18.

12Global Wind Energy Council 2016.

13Pierpont 2009a.

14Martin 2009.

15Chapman and St George 2013. This section has been adapted from this 2013 paper.

16Branco and Alves-Pereira 2004.

17Chapman and St George 2013.

18Smith 2002.

19Jones 2016b.

20Chapman and St George 2013.

21Chapman 2014a.

22Alves-Pereira and Branco 2014.

23Leventhall 2009b.

24von Gierke 2002.

25Health Protection Agency 2010.

26Leventhall 2009b.

27McMurtry 2011.

28Jeffery, Krogh and Horner 2014; McMurtry and Krogh 2014.

29McCunney, Morfeld, Colby and Mundt 2015.

30Roper 2015.

31See player.vimeo.com/video/63965931.

32Berglund, Hassmen and Job 1996.

33Salt and Hullar 2010.

34Leventhall 2007.

35Ingielewicz and Zagubień 2014.

36Stead, Cooper and Evans 2014.

37Evans, Cooper and Lenchine 2013.

38First Dog on the Moon 2015a.

39First Dog on the Moon 2015b.

40Sakula 2016.

41Johnson n.d.

42Tharpaland International Retreat Centre 2012.

43Whisson 2011.

44Noisegirl 2014.

45Anon. 2009.

46Raferty 2012.

47Turvey and Sparling 2002.

48Canadian Broadcasting Corporation 2013.

49Wilsmore et al. 2013

50See for example https://www.beautyofbirds.com/eggproblems.html.

51Green 2015.

52Commonwealth of Australia 2015b.

53Sky News 2015.

54Fair Dinkum Radio 2014.

55Stop These Things 2015a.

56Mechanic and Volkart 1961.