1

One Health/EcoHealth/Planetary Health and their evolution

One Health/EcoHealth/Planetary Health and their evolution

Miasmic theory

Recent years have seen an increase in One Health publications, with 276 published in 2016 compared to only three in 1990. The term ‘One Health’ is relatively new but the concept is ancient. Hippocrates, a Greek physician (c. 460–c. 377 BC) theorised in his text ‘On airs, waters and places’ that disease was caused by environmental factors, putting forward the theory that bad air is equivalent to pestilence. Galen expanded the theory, postulating that individuals’ susceptibility to illness is an interplay between the environment and the balance of four humours in the body.

Miasmic theory, a term derived from the Greek word for stain or defilement, has been around for over 2,000 years and was popularised in the 17th century with the publication of Nathaniel Hodges’ treatise on the 1665 plague in London when he described how air has the potential to propagate the plague. Pestilence in the air was thought to be a major cause of the Black Death in 14th-century Europe (Garcia-Ballester 1994).

Giovanni Maria Lancisi, an Italian physician and epidemiologist, was struck by the co-localisation of malarial outbreaks and swampy marshes and noted in his essay ‘On the noxious exhalations of marshes’ that the humid air and presence of insects around marshy areas may be related to the increased incidence of disease (Mitchill and Miller 1810). While the ‘mal aere’ he described and modern-day malaria may not be the same disease, his linking humid, close air and febrile symptoms may represent an early connection with malaria in areas where the vector is potentially present. However, this may not be the earliest record of mosquitoes being blamed for disease: a plate in the Hortus sanitatis displays an unwell man lying under a tree with insects all around him (Figure 1.1 Meydenbach 1485). Putrid marshes have remained a concern in England since Lancisi’s first observations. In 1774 Rev. Dr Priestly wrote to Sir John Pringle expressing unhappiness with Dr Alexander of Edinburgh’s conclusion that ‘there is nothing to be apprehended from the neighbourhood of putrid marshes’, noting in his letter that, when left alone, water turns black with emanating bubbles. These were perhaps the first examples of links made between the environment and human health.

Figure 1.1 Unwell man surrounded by insects (Meydenbach, Hortus sanitatis, 1485). Made available by the Wellcome Trust Wellcome Images collection via Wikimedia Commons (https://bit.ly/2AQppoj).

Hygiene theory

This link between polluted air (miasma) and disease underpinned reforms to sanitary conditions throughout Western Europe during the Victorian period. In the early 1800s, the industrial revolution in the United Kingdom led to an explosion in migration from rural to urban areas to fill the ever-increasing factories, particularly in northern England. This increase in urban population quickly overwhelmed the rudimentary drainage systems, setting up the perfect storm for the second cholera pandemic emerging from the Ganges River delta region of India. By 1830 cholera had reached Orenburg Oblast in Russia’s south-west, close to Kazakhstan (Henze 2010). As miasma theory still dominated thinking about disease at the time, the UK-imposed quarantine orders for ships sailing from Russia. But in December that year, the water-borne disease (Vibrio cholerae) surfaced in Sunderland (UK) via a ship travelling from the Baltic and soon after in the other big port cities of Gateshead and Newcastle. By the end of 1831 over 6,500 people had died in London from the disease; the following summer around 20,000 people died.

The sudden appearance of cholera in Russia and the UK during 1831–32 in the context of poor communication (and understanding) by municipal authorities was of major public concern which was partly fuelled by the scandal of the murders by William Burke and William Hare, who killed 16 people to supply corpses for dissection by Dr Robert Knox in Edinburgh. In 1826, 23 corpses were discovered on the docks of Liverpool waiting to be shipped to Scotland for dissection. Crowds, particularly in Liverpool, were angry with the medical profession and saw cholera as yet another way for people to be removed to hospitals and killed for dissection.

Sir Edwin Chadwick, a lawyer and social reformer, focused attention on sanitation in an attempt to improve the poor laws. His report, The sanitary condition of the labouring population, published in 1842 with a commissioned supplement in 1843, led to the establishment of the Health of Towns Commission which he chaired. A year later branches of the Health of Towns Association were established in Edinburgh, Liverpool and Manchester. Another major outbreak of cholera in England and Wales in 1848 killed 52,000 people, prompting the government to enact the Public Health Act 1848 to bring the supply of water, sewerage and drainage, and environmental health regulations under the control of one local body, with local health boards overseen by the General Board of Health. Public health improved with the spread of activities across England and Wales. Local movements in public health spurred people to think about the health of their communities, as demonstrated by the petition for an inspection in Durham by the city council, cathedral, university and doctors. Local board powers were extensive, covering sewers, street cleaning, public toilets, water supply and burials. A decade later these powers also included fires and fire prevention, removing dangerous buildings and providing public bathing houses (Local Government Act 1858). These two 19th-century acts, in recognising the relationship between poverty and ill health, particularly in urban areas, are the foundations for the recently published Millennium Development and Sustainable Development Goals and the discipline of planetary health.

Cholera is also associated with the birth of microbiology and epidemiology. The third cholera pandemic in the Ganges delta in 1852 led to over a million deaths. Before Louis Pasteur’s work on germ theory, a little-known Italian anatomist Filippo Pacini, who performed autopsies on cholera victims in Florence, noted when he examined the intestinal mucosa under a microscope the presence of small comma-shaped microorganisms which he called Vibrio. Even though the Paris Academy of Sciences published his Microscopical observations and pathological deductions on cholera in 1854, it was 82 years before he was credited with the discovery. This was despite his ‘A treatise on the specific cause of cholera, its pathology and cure’ being reviewed in 1866 in the British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review. But acceptance of the role of vibrio cholerae in transmitting cholera did not happen until it was rediscovered by Robert Koch in 1884.

Miasma theory was ultimately disproved by John Snow when he proved the environmental connection to cholera. Prior to the Broad Street cholera outbreak in 1854, Snow published ‘On the mode of communication of cholera’ in 1849, in which he set out his theory that cholera is spread from person to person, making the connection that the disease ‘is communicated by something that acts directly on the alimentary canal … excretions of the sick at once suggest themselves as containing some material … accidentally swallowed’. He placed the main route of transmission as direct faecal to oral and likened the transmission to recent studies in intestinal worm diseases. He also theorised that cholera could be disseminated by emptying sewers into drinking water, noting the presence of contaminated drinking water and significant cholera outbreaks in the two cities of Dumfries-Maxwelltown and Glasgow. He also gave circumstantial evidence to support his theory based on the epidemiology of cases in London, but it was his 1855 treatise based on the Broad Street cholera outbreak that proved his theory.

The 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak killed 616 people; the disease resurfaced after significant outbreaks in London in 1832 and 1849 killing 14,137 people. Snow was sceptical of William Farr’s theory that the outbreaks were caused by miasmata from the soil of the River Thames. Having pinpointed the source to a public water pump at Broad Street after talking to locals, he persuaded the local authorities to remove the pump handle. He then constructed one of the first Voronoi diagrams used in health by marking all affected houses with a dot. The well had been dug less than 1 metre from an old cesspit that had begun to leak, with the cholera bacterium supplied by the washing of an infected baby’s nappies into the cesspit.

John Snow also performed one of the first double-blind trials on water supplies. He noted that houses adjacent to one another often received their water from different suppliers. He used statistics to demonstrate that fatalities were higher among customers of certain water suppliers. Snow proved that the Southwark and Vauxhall Waterworks Company was taking water from sewage-contaminated sections of the Thames and redistributing it as drinking water. However, as is frequently the case in public health, policy changes were not immediate. With the crisis passing and the urgency resolved, the authorities reinstated the handle on the Broad Street pump. But another 11 years passed before Snow’s theory was accepted. A further 1886 outbreak in Bromley-by-Bow in East London enabled William Farr, previously a proponent of miasma theory, to apply his specialist skills in biostatistics to link the high mortality rates to the Old Ford Reservoir in East London. Local residents were immediately instructed to boil their drinking water. Farr also built on Snow’s work on cholera, coining the term ‘zymotic diseases’ to describe acute infectious diseases. ‘Zymotic disease’ originated from the term ‘microzymas’, proposed by Antoine Béchamp as a potential cause of contagious diseases, and was used until bacteriology was better established in the early 20th century. Farr also identified urbanisation and population density as public health issues.

Beyond germ theory

John Snow’s demonstration that cholera was a water-borne disease was followed by Louis Pasteur’s experiments in 1860–64 to prove that the source of the microorganisms that grew in nutrient broths was environmental and not through spontaneous generation (Ligon 2002). Fourteen years later Pasteur discovered Streptococcus by demonstrating that blood from a woman dying of puerperal fever could be cultured and that it contained the same microorganism that he had previously observed in furuncles (skin abscesses) (Pasteur 1880).

This discovery heralded germ theory and the observation that infectious diseases were caused by an aetiologic agent. Robert Koch, in the late 19th century, made further progress when he created his famous postulates (conditions which must exist before a particular bacteria can be said to cause particular diseases) based on his work on anthrax. This work was critically important for the development of the specialties of microbiology and infectious diseases, and their spin-offs such as asepsis and antisepsis, but unintended was the narrowing of the concept of infections, their causes and prevention. As with most post-19th century science, specialists replaced polymaths. Early public health was resplendent with multidisciplinary ideas and One Health concepts, but these were lost to the greater struggles of diagnoses and treatments of specific conditions.

Rudolf Virchow, practising against the trend towards specialisation, was a polymath physician and pathologist living in Germany in the 19th century. His scientific contributions, in addition to establishing public health in Germany, built on his belief that medicine was both a scientific discipline and a social science. Revered as the father of cellular pathology, he was also widely known for his political views likening individual people to cells and the state to the organism. Curiously, Virchow refuted the idea that infections were caused by microorganisms, believing instead they were a result of cellular abnormalities and wider social situations. Curious because he also described the transmission cycle for Trichinella spiralis, which led to meat inspection. In all respects he was a proponent of microscopic examination and his work on cellular pathology, in particular comparing pathologies between humans and animals, was published as his great work Cellular pathology (Virchow 1859).

Virchow’s focus on comparative pathology led him to establish connections between human and animal diseases, for which he is claimed to have labelled zoonoses, from the Greek for ‘animal’ and ‘sickness’. In the mid-1850s he is believed to have said ‘Between animal and human medicine there are no dividing lines – nor should there be … The object is different but the experience obtained constitutes the basis of all medicine’. The observation of comparative anatomy, physiology and pathology had been made by John Hunter, who co-founded the Royal Veterinary College in London, and Sir Jonathan Hutchinson, who contributed to the idea of animal models of disease.

One Medicine

If Virchow did coin the term zoonosis, he left unclear which diseases he thought were the origin of transmission; he may simply have been referring to his work on trichinellosis (a disease caused by eating raw or undercooked meat infected with the larvae of a worm). Nevertheless his writings influenced physicians such as Sir William Osler, who studied with Virchow for some time in Germany before returning to Canada. Osler’s appointment in the Medical Faculty of McGill University was as a lecturer to medical and veterinary students from the Montreal Veterinary College, which later became affiliated with McGill. This vet college later amalgamated into Osler’s Division of Comparative Medicine but Osler continued to teach medical and vet students in Philadelphia and Johns Hopkins University. Osler is famous for his contributions to the establishment of medical residency and his textbook The principles and practice of medicine. But he has also been credited with coining the term ‘One Medicine’ to describe his interest in comparative pathology. While there is no evidence in his writings for this, the concept was clearly established in his mind.

One Medicine first appeared when Calvin Schwabe, a veterinary epidemiologist at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis), introduced the term in his book Veterinary medicine and human health, 3rd edition (Schwabe 1984). In his earlier edition, he described veterinary medicine as ‘the field of study concerned with the diseases and health of non-human animals. The practice of veterinary medicine is directly related to man’s wellbeing in a number of ways’ (Schwabe 1964).

Schwabe based his idea of One Medicine on his observations of the close relationship, for both good health and ill health, between humans, domestic animals and public health. His ideas were further developed when he established a Master of Preventive Veterinary Medicine at UC Davis, which taught the principles and strategies of mass disease control and prevention in animals. He noted that:

Traditional veterinary medicine is concerned in varying degrees with problems in agriculture, biology and public health. These have been the three natural avenues of development for veterinary medicine. Until recent years, however, progress in extension of organised veterinary interests in public health has been frustrated by ‘accepted beliefs’ – long held in the Western world – on the presumed biological uniqueness of man. These erroneous notions have thwarted a general appreciation of veterinary contributions to the development of a science of general medicine.

James Harlan Steele continued to lead multidisciplinary approaches to health and medicine and today is widely regarded as the father of veterinary public health, earning his doctorate of veterinary medicine from Michigan State University and master of public health from Harvard. During World War II in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands he co-ordinated milk and food sanitation programs to reduce the risk from brucellosis and bovine tuberculosis. After the war, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ( CDC) discussed with him the role of vets in combating zoonotic infections as it was clear they constituted a significant health risk but little attention had been given to surveillance or research. Steele subsequently wrote the seminal report Veterinary public health in 1945, which examined zoonotic disease risks and how medicine may benefit from veterinarian knowledge and advice. This led to a new position of Veterinary Medical Officer in the Public Health Service. Steele, as chief veterinary officer in the CDC, established the veterinary public health program. He initially focused on rabies but later expanded to bovine tuberculosis, brucellosis, Q fever, psittacosis, salmonellosis and other food-borne diseases. He also integrated veterinary public health into the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and later the World Health Organization (WHO). In these ways, he brought One Health into the mainstream, embedding it within health policy and disease prevention and response.

EcoHealth

Ecosystem health, or EcoHealth, is a systems-based approach to promoting health and wellbeing with a focus on social and ecological interactions. Originating in North America, it claims to add to disciplinary knowledge by conducting pre-study meetings with affected communities to include social dimensions in the overall solution. The International Development Research Centre, established in 1970 as a Canadian federal Crown corporation, is a significant investor in international development. Jean Lebel, the current president, has written extensively on ecosystem approaches to health, focusing on the following three principles: transdisciplinary approach, participation and equity.

Strong support came from the EcoHealth Alliance, which began as the international arm of the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust in the Channel Island of Jersey; it is now named the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. Wildlife Preservation Trust International, which started in 1971, became the Wildlife Trust in 1999 and in 2010 changed into the EcoHealth Alliance. During this time, it morphed from an organisation focused on captive breeding of endangered species to one with an environmental health and conservation remit. The main focus of the EcoHealth Alliance is on conservation medicine, defined as an interdisciplinary field focused on the relationships between human and animal health, and the environment.

One of the best-known outputs of the then Wildlife Trust was an examination of the impact of human population growth, latitude, rainfall and wildlife richness on emerging infectious diseases (EIDs). While some of their findings were skewed by the distribution of EID laboratories, vector-borne pathogens tended to be in tropical and subtropical regions and zoonotic pathogens were much more likely to originate from wildlife than from non-wildlife reservoirs.

EcoHealth work is exemplified by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Emerging Pandemic Threats (EPT) program, which was facilitated by the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus and influenza A(H5N1). While USAID previously centred on A(H5N1), the Pandemic Influenza and Other Emerging Threats Unit launched the EPT 2009 program comprising four projects: Predict, Prevent, Identify, and Respond, operating in 20 countries. The EcoHealth Alliance is an implementing partner of the PREDICT project, and focuses on the detection and discovery of zoonotic diseases at the wildlife–human interface. The target countries are strengthening surveillance and laboratory capacity to monitor wildlife and people who have contact with wildlife so potential emerging pathogens can be identified early. The EcoHealth Alliance covers bio surveillance, deforestation, One Health, pandemic prevention and wildlife conservation.

One Health

With comparative medicine driving One Medicine in the veterinary world, the CDC, PAHO, and WHO lead a public health approach within a multidisciplinary framework called One Health. One Health involves collaborating disciplines working towards optimal health for the planet – its people, animals and the environment. This makes it distinct from One Medicine by taking a health rather than curative approach and stepping away from the narrow focus on animals and the environment for the benefit of humans. During the 1980s the concept of sustainable development – for people, animals and ecosystems – required health to be inclusive of these components. One Health describes people and agencies that link human, animal and environmental health through multi-sectoral and transdisciplinary approaches. Together, they tackle global health issues by prioritising the health of both humans and animals, and protecting these populations from infectious diseases and disease spread. Since 2000 One Health has had a pivotal role in health system strengthening, by integrating health services, particularly in hard-to-reach communities. One Health methods were seen as a better way to achieve the Millennium Development Goals following the WHO ministerial summit in Mexico City in 2004.

The 12 Manhattan Principles of One Health were also formulated in 2004 as a result of the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Rockefeller University bringing health experts together in a ‘One World, One Health’ event to discuss current and future emerging diseases, particularly Ebola virus, avian influenza virus and chronic wasting disease. This was followed by an article in Foreign Affairs, supporting the need for multidisciplinarity in approaches to infectious diseases, citing HIV and SARS as examples of emerging zoonotic infections.

Another leap by the One Health movement occurred in 2007, when Roger Mahr, then president of the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), and Ronald Davis, then president of the American Medical Association, discussed how vets and medical doctors can work together. A One Health Initiative Task Force was set up and chaired by Lonnie King, then director of the National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne and Enteric Diseases at the CDC; the US Assistant Surgeon General, William Stokes, was an invited member. This culminated in a report by the task force, which laid much of the groundwork for One Health (King et al. 2008). The recommendation to establish a National One Health Commission (OHC) as a non-profit organisation was implemented in 2008. Its mission was to ‘“educate” and “create” networks to improve health outcomes and wellbeing of humans, animals and plants, and to promote environmental resilience through a collaborative, global One Health approach’. The OHC is training the next generation of One Health leaders.

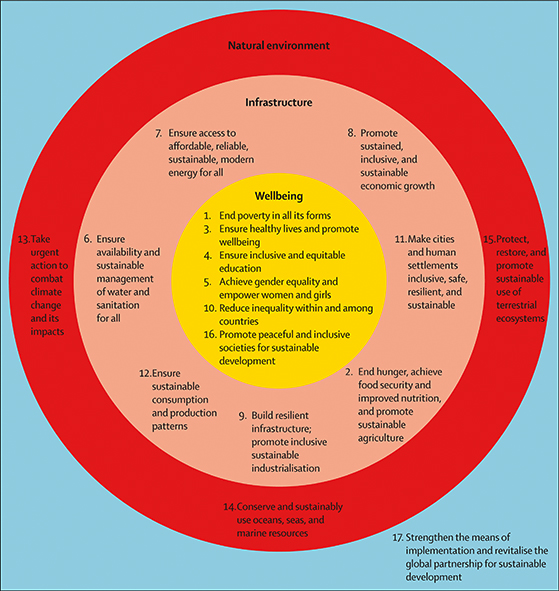

The Roadmap to the OHC One Health Agenda 2030 says the only way to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is through a multidisciplinary One Health approach. This work originated from a European Union funded initiative called the Network for Evaluation of One Health. Of particular note was the adaptation of a previous SDG figure placing the SDGs within a framework of wellbeing, infrastructure and natural environment (Waage et al. 2015) but highlighting some SDGs will naturally come into conflict with others, particularly goals 8, 9 and 12 on economic growth, industrialisation, and production and consumption, respectively (Figure 1.2). The importance of the political opportunity the SDGs represent for embedding a One Health approach – one that integrates the silos of EcoHealth, eco-public health, ecosystems and planetary health (see below) – has been highlighted by Queenan et al. (2017). This incorporates a whole-of-society approach to policy making and integrating One Health actions through health services, diagnostics, surveillance, and so on.

Figure 1.2 Governing the UN Sustainable Development Goals: interactions, infrastructures, and institutions (Waage et al.2015).

Core competency domains for One Health have been developed as a result of three independent initiatives: the Bellagio Working Group (Rockefeller Foundation and the University of Minnesota), the Stone Mountain Meeting Training Workgroup, and the USAID RESPOND initiative. They came together in 2012 in Rome to synthesise the competencies. While the sets of competencies remain separate, they all have overarching themes of management, communication and informatics, values and ethics, leadership, team and collaboration, roles and responsibilities, and systems thinking.

In addition to the OHC, in 2008 a One Health Initiative comprising a website developed by an autonomous team of people began highlighting information and research in One Health. This team originally founded by two physicians and a vet expanded to include public health expertise. This focus brings human and animal health together, although environmental health comes under its umbrella. Similar to the OHC, its main purpose is communication, information and education.

The One Health Platform has its own journal, One Health, which provides a forum for researchers, identifies research gaps and also raises awareness and disseminates information. It also organises the One Health Congress, the fifth of which was held in Saskatoon, Canada, in 2018. In an attempt to reduce the silos among these multidisciplinary initiatives, the 2016 Congress was a joint congress between the One Health Platform congress and the International Association for Ecology and Health.

Box 1.1: Global One Health Day Initiative

The One Health Platform in collaboration with the OHC and the OHI has initiated a Global One Health Day, the first held on 3 November 2016. The goal of One Health Day is to focus the world on One Health interactions and for the world to ‘see them in action’. With multiple self-started activities around the globe, it hopes to give One Health advocates opportunities to join forces in educational activities and events that bring together academicians and health professionals from different backgrounds. The One Health events offer educational programs in both academic and non-academic settings by inviting professionals from a variety of disciplines to discuss One Health topics and share their knowledge and experiences at One Health events.

New kid on the block: planetary health

In 2015 the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health published a series of papers, flagshipped by ‘Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch’ (Whitmee et al. 2015). The commission defined planetary health as

the achievement of the highest attainable standard of health, wellbeing, and equity worldwide through judicious attention to the human systems – political, economic, and social – that shape the future of humanity and the Earth’s natural systems that define the safe environmental limits within which humanity can flourish. Put simply, planetary health is the health of human civilisation and the state of the natural systems on which it depends. (Whitmee et al. 2015)

This commission first met in Bellagio, Italy, in July 2014 and was chaired by Sir Andrew Haines, former director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. It consisted of experts in environmental health, medicine, biodiversity and ecology. The three key challenges were a conceptual need to account for future harms to health and environment, a continuing lack of transdisciplinary research, particularly on the social and environmental drivers of ill health, and issues around global governance. While planetary health has multiple overlapping principles and ideas with both One Health and EcoHealth, it has been put forward by the Lancet as a new science. It is also being touted as the natural successor to public and global health. While global health built upon international health by focusing on the need to improve health through achieving equity, planetary health takes this further by incorporating the foundation upon which we live.

Richard Horton’s manifesto on planetary health has been criticised for excluding One Health but this may be misguided as the way planetary health has been framed is as a co-movement with One Health and EcoHealth. Unlike much of One Health literature, the commission focused more on climate change, ocean acidification, freshwater usage, land use and soil erosion, pollutants and the loss of biodiversity; and less on zoonotic transmission between humans and animals (Whitmee et al. 2015). As well as human effects on the environment, the commission looked at human factors such as consumption, population growth, technology and urbanisation. Like other movements described above, planetary health sees itself as the implementer and integrator of the SDGs. The propositions put forward also go much further than previous movements, with increased focus on public and global policy and less on information and education.

In response to the commission, Harvard University and the Wildlife Conservation Society in 2015 founded the Planetary Health Alliance, which aims to support the development of a ‘rigorous, policy-focused, transdisciplinary field of applied research aimed at understanding and addressing the human health implications of accelerating change in the structure and function of Earth’s natural systems’. The alliance comprises a consortium of over 60 universities and NGOs with a similar purpose to the other multidisciplinary initiatives: to educate, inform, convene meetings, and build networks and best practices.

Where to next?

With lots of players, initiatives and ideas, there appears to be agreement for multi- or transdisciplinary approaches to earth’s current challenges. If the SDGs are to be achieved we need to work differently and avoid the vertical siloed approach that the MDGs often elicited. The approach needs to be systems-based and policy-informing and move far beyond the simple recognition that many emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic to addressing the many challenges as set out by the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission (Whitmee et al. 2015). While it appears that planetary health encapsulates One Health and EcoHealth, these disparate groups need to join to be effective in the policy arena. Irrespective of the name, there needs to be recognition that modern public/global health needs a composite of human, animal and ecological health. This premise was uncontested in the early days of public health. The scientific basis for miasma theory may have been flawed, but the recognition that an ill environment causes illness in people and that root causes need addressing still pertains to modern-day Planetary Health. We have come full-circle from the polymaths of public health with an interest in methodologies and human/animal/environmental health, to the need to bring these disciplines back together and co-ordinate their work.

Works cited

Bathurst, W.L. (1831). London Gazette (18807): 1026–1027.

Burrell, S., and G. Gill (2005). The Liverpool cholera epidemic of 1832 and anatomical dissection – medical mistrust and civil unrest. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 60(4): 478–98.

Byrne, J. (2004). The Black Death. London: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Calman, K. (1998). The 1848 Public Health Act and its relevance to improving public health in England now. BMJ 317(7158): 596–8.

Cardiff, R.D., J.M. Ward, and S.W. Barthold (2007). ‘One medicine – one pathology’: are veterinary and human pathology prepared? Laboratory Investigation 88(1): 18–26.

Chadwick, E. (1843). Report on the sanitary conditions of the labouring population of Great Britain. Beccles, UK: W. Clowes & Sons.

Cook, R.A., W.B. Karesh, and S.A. Osofsky (2004). One World, One Health. http://www.oneworldonehealth.org.

Elsevier (2017). One Health. http://bit.ly/2BWg5kw.

Frankson, R., et al. (2016). One Health core competency domains. Frontiers in Public Health 4(4): 239.

Garcia-Ballester, L. (1994). Practical medicine from Salerno to the Black Death. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Henze, C.E. (2010). Disease, health care and government in late imperial Russia: life and death on the Volga, 1823–1914. London: Taylor & Francis.

Hodges, N. (1720). Loimologia, or, An historical account of the plague in London in 1665: with precautionary directions against the like contagion. London: E. Bell & J. Osborn.

Horton, R. (2013). Planetary health – a new vision for the post-2015 era. Lancet 382(9897):1012.

Horton, R., et al. (2014). From public to planetary health: a manifesto. Lancet 383(9920): 847.

Jones, K.E., et al. (2008). Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451(7181): 990–3.

Jordan, T.E. (1993). The degeneracy crisis and Victorian youth. New York: SUNY Press.

Kahn, L.H., et al. (2014). A manifesto for planetary health. Lancet 383(9927): 1459.

Karesh, W.B., and R.A. Cook (2005). The human–animal link. Foreign Affairs 84(4): 38–46.

Kennedy, E. (1869). Hospitalism and zymotic diseases: as more especially illustrated by puerperal fever, or metria. Also, a reply to the criticisms of seventeen physicians upon this paper. London: Longmans, Green.

King, L.J., et al. (2008). Executive summary of the AVMA One Health Initiative Task Force report. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 233(2): 259–61.

Klauder, J.V. (1958). Interrelations of human and veterinary medicine. New England Journal of Medicine 258(4): 170–7.

Lebel, J. (2003). Health: an ecosystem approach. Ottowa, ON: International Development Research Centre.

Ligon, B.L. (2002). Louis Pasteur: a controversial figure in a debate on scientific ethics. Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases 13(2): 134–41.

Mackenbach, J.P. (2009). Politics is nothing but medicine at a larger scale: reflections on public health’s biggest idea. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 63(3): 181–4.

Mackenzie, J.S., M. McKinnon, and M. Jeggo (2014). One Health: from concept to practice. In Confronting emerging zoonoses: the One Health paradigm, A. Yamada, L.H. Khan, B. Kaplan, T.P. Monath, J. Woodall, and L. Conti, eds., 163–189. Berlin: Springer.

Meydenbach, J. (1485). Hortus sanitatis. Mainz, Germany: J. Meydenbach.

Mitchill, S.L., and E. Miller (1810). The medical repository, comprehending original essays and intelligence relative to medicine, chemistry, natural history, agriculture, geography and the arts; more especially as they are cultivated in America; and a review of American publications on medicine and the auxiliary branches of science, 3rd edn. New York: Collins & Perkins.

Nolan, R.S. (2013). LEGENDS: the accidental epidemiologist. http://bit.ly/2L1N0Hs.

One Health Commission (2017). Mission/Goals. http://bit.ly/2L0g0PG.

One Health Initiative (2017). One Health Initiative will unite human and veterinary medicine. http://bit.ly/2RAvOuN.

One Health Platform (2016). The 4th International One Health Congress & the 6th Biennal Conference of the International Association for Ecology and Health. http://oheh2016.org/.

Pacini, F. (1866). A treatise on the specific cause of cholera, its pathology and cure. British & Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review 38: 167–8.

Pacini, F. (1854). Osservazioni microscopiche e deduzioni patologiche sul cholera asiatico. Florence: F. Bencini.

Pasteur, L. (1880). On the Extension of the Germ Theory to the Etiology of Certain Common Diseases. Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, xc: 1033–44.

Planetary Health Alliance (2017). Planetary Health Alliance. http://bit.ly/2RAuEzr.

Priestley, J. (1774). On the noxious quality of the effluvia of putrid marshes. A letter from the Rev. Dr Priestley to Sir John Pringle. Philosophical Transactions 64: 90–5.

Queenan, K., et al. (2017). Roadmap to a One Health agenda 2030. CAB Reviews 12(014): 1–17.

Schultz, M.G. (2008). Rudolf Virchow. Emerging Infectious Diseases 14(9): 1480–1.

Schultz, M.G. (2014). In Memoriam: James Harlan Steele (1913–2013). Emerging Infectious Diseases 20(3): 514–5.

Schwabe, C. (1964). Veterinary medicine and human health, 1st edn. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Schwabe, C. (1984). Veterinary medicine and human health, 3rd edn. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Singer, M. (2009). Introduction to syndemics. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Snow, J. (1849). On the mode of communication of cholera. London: Wilson & Ogilvy.

United States Agency for International Development. Emerging pandemic threats. http://bit.ly/2RFS7PV.

Virchow, R. (1848). Der armenarzt. Medicinische Reform 18: 125–7.

Virchow, R. (1859). Die cellularpathologie in ihrer begründung auf physiologische und pathologische gewebelehre. Berlin: August Hirschwald.

Virchow, R. (1860). Uber Trichina spiralis. Virchows Arch. Pathol. Anat. 18(3–4): 330–46.

Waage, J., et al. (2015). Governing sustainable development goals: interactions, infrastructures, and institutions. In Thinking beyond sectors for sustainable development, J. Waage and C. Yap, eds., 79–88. London: Ubiquity Press.

Walker, L., H. LeVine, and M. Jucker (2006). Koch’s postulates and infectious proteins. Acta Neuropathologica 112(1): 1–4.

Whitmee, S., et al. (2015). Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health. Lancet 386(10007): 1973–2028.

Zinsstag, J., E. Schelling, K. Wyss, and M.B. Mahamat (2005). Potential of cooperation between human and animal health to strengthen health systems. Lancet 366(9503): 2142–5.