Health policy

Key terms/names

acute/chronic conditions, ‘Baumol effect’ on public expenditure, casemix funding, community rating/risk rating, cost-shifting, cost–benefit analysis, fee-for-service health care, health insurance/single-payer health insurance, moral hazard, muddling through, out-of-pocket costs and co-payments, primary care, public health, Rawls’ ‘original position’, social determinants of health, technical and allocative efficiency

A fundamental concern of governments is the health of their citizens, and all governments have policies directed to, or having an effect on, people’s health. Most policy concern is with health care – that is, the provision of services, ranging from general practitioner (GP) consultations through to high-intensity care for those suffering severe accidents or life-threatening diseases such as cancer.

But in terms of health outcomes – the capacity of people to enjoy many years of healthy life – provision of health care is only one factor. Governments have programs promoting healthy lifestyles to reduce the need for health care, and almost all government policies contribute to or detract from people’s health directly or indirectly.

Health care, however, tends to dominate policy considerations. For reasons to do with social equity and failures of market mechanisms to deliver health care, governments of all persuasions, ‘left’ or ‘right’, are heavily involved in health care, which commands a large and growing proportion of government budgets. In Australia one-fifth of government outlays are for health care.

Governments and the health of nations

Public health

Many government interventions that contribute to (or detract from) people’s health take place in areas other than the health portfolio. Regulations such as those applying to firearms, food safety, air quality and use of seat belts all have an effect on health. So too do provision of infrastructure such as clean water and sewerage, and town planning (do our cities encourage walking, are there enough playing fields?). Policies to do with slowing the rate of climate change or mitigating its effects may seem to be distant from health policy, but climate change can have profound effects on the incidence of heat stress, food supply, the spread of diseases, air quality, natural disasters and dislocation of entire populations.1

Then there are specific measures that are generally described as ‘public health’. These include vaccinations, and campaigns on safe sex, discouragement of smoking and on responsible use of alcohol. The reach of a government’s ‘health’ portfolio varies between states or other divisions within nations: governments may, for example, include sport in the health portfolio.

Social determinants of health – unsung but effective policies

Sound health and socio-economic conditions are strongly correlated. Those who enjoy connections to the community, well-paid and meaningful work, social support and control over their lives enjoy better health than those who don’t. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) points out that ‘people in lower socio-economic groups are at greater risk of poor health, have higher rates of illness, disability and death, and live shorter lives than those in higher socio-economic groups’.2

Correlation does not prove causation: those who suffer poor health cannot easily find well-paid employment, for example. But there is strong evidence that there is also causation in the other direction: people’s health over their lifetimes is influenced by their socio-economic conditions. Among what are known as the ‘social determinants of health’ are early childhood development, education attainment, people’s occupation (those with more control over their work enjoy better health), job and financial security, and people’s degree of social integration.3

There is also evidence that those who live in societies with more economic inequality, regardless of their individual income or wealth, have poorer health than those in more equal societies.4 Therefore policies relating to early childhood education, employment, and income distribution, which may be distant from the health portfolio, can have a profound effect on people’s physical and mental health.

There is also evidence that once countries reach a high level of prosperity, and have been able to afford significant spending on health care, additional spending has diminishing returns. Figure 1, derived from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data for 43 middle- and high-income countries, shows the relation between health spending per capita (predominantly health care) and life expectancy, with certain countries, including Australia, marked. Apart from the USA, all countries in the right-hand two-thirds of that graph have much the same life expectancy, even though spending varies by a factor of about two to one. The USA, it can be seen, does not appear to have achieved good value-for-money spent on health care – an ongoing issue with dysfunctions in its private health insurance model.

Figure 1 Life expectancy at birth and health spending per capita, 43 countries. Source: data from OECD 2017, data as for chart 3.3, page 49, excluding South Africa.

This is not to underplay the importance of devoting resources – government or private – to health care, but it is a reminder that while policies to do with health care command attention in the political arena, in high-income countries like Australia people’s health is influenced by many policies other than those within the health portfolio.

Australia’s health

By world standards Australians enjoy good health, but so do those who live in other high-income ‘developed’ countries. Australians’ life expectancy at birth, a key indicator of a nation’s health, is close to the highest in the world.5

An important factor contributing to Australia’s good health is its young population. Most high-income countries have an aged population, but in Australia’s case a sustained high rate of immigration has kept our population comparatively young. In 2018 the median age of Australians was 39; by contrast the median age of Italians, Japanese and Germans was above 45.6 Our comparatively young population has kept demand for expenditure on health care under control. Also, because immigration policies are selective, immigrants tend to be healthier than the Australian-born population.

Nationwide indicators such as life expectancy can mask significant variations within population groups, however. Indicators of ‘disease burden’ show that people living in non-metropolitan regions have significantly poorer health and die younger than those in cities. Indigenous Australians have around 10 years lower life expectancy than other Australians (although the gap is closing) and they experience high rates of child mortality (twice the national average).

In terms of health risk factors Australia scores well on smoking but poorly on obesity (28 per cent of Australians aged 15 and over are obese), and our alcohol consumption is high by international standards.7

Mental health has become an area of increasing policy concern in recent years. According to the AIHW almost half of Australians between the ages of 16 and 85 ‘will experience a mental disorder such as depression, anxiety or substance use disorder at some stage in their life’.8

Mental health disorders tend to peak in late teenage years, but for almost all other conditions the prevalence of poor health is strongly correlated with age. Readers of this textbook are probably among those least likely to have more than occasional first-hand experience with health care services. Figure 2 shows the incidence of Medicare services (consultations with GPs and specialists, operations, and certain services provided by other health professionals) by age.

Figure 2 Medicare services per capita by age group, 2011–12. Source: data from Department of Health 2019, Medicare statistics 2011–12.

Government involvement in health care

Within health portfolios governments’ main concerns are generally about the funding of health care – either through public budgets (such as Australia’s Medicare) or through private insurance, which is generally subject to regulation, tax concessions or direct subsidies. Also in some cases, most notably state government-owned public hospitals, governments are involved in delivering health care. It is notable that what passes for public debate on health care often confuses governments’ roles in funding and providing health care.

There are two broad principles driving government involvement. First, people seek some mechanism to share their outlays for health care through insurance, public or private. And second, there are reasons why there would be socially and economically unacceptable outcomes if health care were left to private markets.

Community-rated health insurance

In times long past, those who could not afford health care went without, or depended on the meagre offerings of charities. Colonial governments financed services to provide care ‘for the hospital care or indigent class of the community’, but such services provided in public hospitals were basic.9 Also medical practitioners would see it as a noblesse oblige (the paternalistic idea that those with means had an unwritten obligation to help the less fortunate) to provide care for the poor.

There has been a slow transition in health care from a ‘charity’ model, whereby the poor or those with high needs had to rely on religious or similar charitable institutions, to one of community sharing, whereby through contributions to insurance-type arrangements, or through taxes, communities share all or part of their health care expenses. The first mutual benefit societies developed in New South Wales in the 1830s, but they covered only a minority of the population. It wasn’t until the period after 1945 that mechanisms for widespread sharing of health care costs were developed with increasing levels of government involvement.

Worldwide the development was along two paths. One path, in Britain and the Nordic countries, was for governments to take the prime role in funding, and in some cases providing, tax-financed health care for all. Many other European countries relied more on mutual benefit societies, which slowly extended their reach to become not-for-profit health insurers. The USA, by contrast, relied on insurance provided by for-profit companies. Some countries’ policies were guided by the principle that whatever one’s means, health care would be accessible to everyone on the same terms (‘universalism’) while others directed health care funding more at the poor or indigent, using means tests.

Much is written on the difference between these funding systems. There are, indeed, important differences: in particular America’s reliance on for-profit insurance has resulted in that country having high-cost health care and in many people being uncovered. (As a proportion of GDP, America’s total health care costs, private and government, are the highest of all OECD countries, and almost double the OECD average.10) But there are also important similarities in different countries’ policies, the strongest being people’s choice, generally backed through political processes, to share health care costs with one another, through some form of insurance, private or public.

Whatever our ‘left’ or ‘right’ political orientation, our acceptance or otherwise of the outcomes of competitive markets, and whatever our general norms on sharing, for health care we tend to be communal in our values, and we seek mechanisms of sharing and redistribution.

Individuals may believe that because they have good education and the reserves of accumulated savings they can weather most economic contingencies, but when it comes to health care most people have little knowledge of their risks. No matter how fit we are, life-changing illness or accident can occur at any time.

For our health care needs we are in what philosopher John Rawls calls an ‘original position’.11 When people are asked to choose the rules which should govern the distribution of wealth and income in a society, but when they don’t know what place they will occupy in that society, they are in an ‘original position’. In such situations people tend to favour rules that result in some degree of levelling – a redistribution from the well-off to the not so well-off.

At first sight there seems to be a simple way to fill this need: if people seek to share their health care costs with one another, then they should be free to do so through private insurance or through mutual societies. But such laissez faire arrangements fail to meet community needs.

In the comparatively unregulated markets of general insurance, where we insure our houses and cars, markets can work reasonably well. Insurance firms, using indicators of risk, charge according to those indicators. Someone with a safe driving record pays a lower premium than someone with a string of accidents and offences. This practice is known as ‘risk rating’.

But risk rating for health insurance would be extremely difficult because for many high-cost contingencies there are no clear risk indicators: debilitating conditions such as cancer can occur without any prior indicators.

The other main problem with risk-rated health insurance is political unacceptability. Private insurers would set prohibitively high premiums for older people, and could refuse to cover people who have pre-existing chronic conditions, who work in hazardous occupations or who have known risk factors. This would be unacceptable by most people’s norms of social justice, remembering that the poor are often those with highest health care needs.

Therefore, through political processes that override market mechanisms, governments generally intervene to achieve what is known as ‘community rating’ for health insurance. That is a system where there is partial or complete equalisation of insurance premiums across the community, or even forms of subsidies from those with low needs to those with high needs.

Government-financed ‘single-payer’ systems, such as those in the Nordic countries, the UK and Canada, achieve community rating through their taxation systems. In terms of administrative costs these are by far the most efficient systems, because they tap into the scale economies and powers of compulsion of the taxation system, and to the extent that their taxation systems are progressive they achieve an equitable distribution of health care financing.

Achieving community rating through private insurance is more difficult. Private insurers incur high administrative costs, including the costs of competing for customers, and the regulations that are designed to achieve community rating are complex, often leading to perverse incentives.

Public or private insurance

It may seem odd that many governments should choose to use private insurance to do what the tax and public expenditure system, with all its controls and accountability, can do more efficiently and equitably. When private health insurance is compulsory (as in Japan and the Netherlands), or highly subsidised and incentivised (as in Australia), it can be considered as a ‘privatised tax’. In terms of the impact on people’s pockets, there is little difference between a tax collected by a body such as the Australian Taxation Office and a compulsory or near-compulsory payment to a health insurer: a cut in official taxes may be more than offset by a rise in private health insurance premiums.

The explanation lies partially in the politics of public accounting. Governments are often driven by a simplistic agenda of keeping taxes (official taxes as revealed in public budgets) low, and politically it is easier to blame private insurers for high and rising premiums.

But even in countries ideologically committed to private mechanisms, governments still become involved in at least partially funding health care. Table 1 shows how health care is funded in high-income ‘developed’ countries.

|

|

|

Government schemes |

Compulsory health insurance |

Voluntary health insurance |

Out-of-pocket |

Other |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Denmark |

84 |

0 |

2 |

14 |

0 |

100 |

|

2 |

Sweden |

84 |

0 |

1 |

15 |

1 |

100 |

|

3 |

UK |

80 |

0 |

3 |

15 |

2 |

100 |

|

4 |

Norway |

74 |

11 |

0 |

14 |

0 |

100 |

|

5 |

New Zealand |

71 |

9 |

5 |

13 |

3 |

100 |

|

6 |

Ireland |

70 |

0 |

12 |

15 |

3 |

100 |

|

7 |

Canada |

69 |

1 |

13 |

15 |

2 |

100 |

|

8 |

Australia |

67 |

0 |

10 |

20 |

4 |

100 |

|

9 |

Finland |

61 |

13 |

3 |

20 |

3 |

100 |

|

10 |

Iceland |

52 |

29 |

0 |

17 |

2 |

100 |

|

11 |

Austria |

31 |

45 |

5 |

18 |

2 |

100 |

|

12 |

USA |

27 |

23 |

35 |

11 |

4 |

100 |

|

13 |

Switzerland |

22 |

42 |

7 |

28 |

1 |

100 |

|

14 |

Belgium |

18 |

59 |

5 |

18 |

0 |

100 |

|

15 |

Netherlands |

9 |

71 |

6 |

12 |

1 |

100 |

|

16 |

Luxembourg |

9 |

73 |

6 |

11 |

1 |

100 |

|

17 |

Japan |

9 |

75 |

2 |

13 |

1 |

100 |

|

18 |

Germany |

7 |

78 |

1 |

13 |

2 |

100 |

|

19 |

France |

4 |

75 |

14 |

7 |

1 |

100 |

Table 1 Health care funding by source of funds (%), 2015. Source: OECD Health Statistics (http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm), data for high income OECD countries (GDP per capita > $US $40 000 in 2017 at PPP).

Whatever form insurance takes, those seeking health care usually have to make some out-of-pocket outlays. Such payments may be in the form of a fixed partial contribution (as with pharmaceuticals in Australia) or in the form of payments that accumulate before the insurer, usually a government insurer, covers all or a large part of further expenses. In high-income ‘developed’ countries, including Australia, out-of-pocket expenses are generally around one-fifth of total health care expenditure, although they can vary tremendously between different services.

Market failures in health care

Government involvement in health care isn’t just about achieving some form of equity through community rating. There are also ‘market failures’ in the provision of health care. In the economists’ model of well-functioning competitive markets there are many conditions to be satisfied, including easy and free exchange of information between suppliers and customers, and the absence of monopolisation or concentration of market power. Markets for clothes and fresh fruit come close to the ideal competitive model, but health care is far removed from it in three important ways.

First it is almost impossible for consumers to judge the quality of services on offer. Although there is no shortage of websites with health advice, in health care the consumer is generally in a position where he or she must place a high degree of trust in the professional judgement, education and expertise of the medical practitioners or other health professionals providing services. Economists refer to this as a situation of ‘information asymmetry’.

Second, there is the potential for service providers, particularly medical specialists with highly specific skills, to exert a high degree of market power. We expect medical specialists to be well qualified, with tough university admission requirements and many years of rigorous training. This, in itself, makes for scarce supply, and when the professional bodies themselves have some power over accreditation they can restrict supply even further. Such supply limitations give service providers the power to set high prices.

Similarly for pharmaceuticals there is an inbuilt degree of market power enjoyed by large corporations. Bringing a new pharmaceutical to market involves large outlays on science and discovery and on clinical trials, easily running into hundreds of millions of dollars. In order to encourage firms to make such investments, governments offer pharmaceutical firms patent protection – usually in the order of 20 years. Without patent protection there would be little incentive for development of new medicines, but with patent protection pharmaceutical firms would be able to use their market power to charge very high prices for pharmaceuticals. Therefore as a quid pro quo for patent protection governments generally intervene to control prices pharmaceutical firms can charge.

Third, when transactions are covered by insurance – public insurance such as Medicare or private health insurance through commercial or mutual bodies – there are incentives for both users and providers for overuse. When a service is free or heavily subsidised at the point of provision, the price signals which act as rationing mechanisms in most markets are absent. Economists refer to this phenomenon by the quaint term ‘moral hazard’.

Health economists argue about the extent of moral hazard in health care. Most (but not all) health care procedures involve some pain or discomfort, which tends to rule out frivolous demand on the consumer side. And there is evidence that even modest prices can deter people from using therapeutically necessary services.12

An enduring debate among health economists has been about the appropriateness of what is known as ‘fee-for-service’ health care. Fee-for-service care is a familiar and established system of payment, particularly for outpatient services. In Australia Medicare pays medical practitioners fixed fees for defined items of service. A common such service is ‘Item 23’ on the Medicare benefits schedule – a GP consultation of less than 20 minutes.

Some argue that fee-for-service encourages overservicing by practitioners and overdependence on health care by patients, suggesting in their place that other forms of payment should be used, such as what is known as ‘capitation’, where a medical practitioner or health clinic is paid according to the number of people in their catchment area (adjusted for age and known risk factors). Unsurprisingly critics of capitation argue that it can provide incentives for under-servicing.

Drivers of health care expenditure

Whichever measure is used – real expenditure per capita or expenditure as a proportion of GDP – health care expenditure is rising in almost all countries. During 2003 to 2016 real per-capita health care expenditure growth in OECD countries averaged 2.4 per cent a year, a rate that would see a doubling every 30 years.13 Australia’s growth in health care expenditure has been only a little lower.14 Because governments directly fund a large proportion of health care, and try to control the prices charged by regulated insurers and by those with market power, rising health care expenditure is a significant political concern.

The main driver of expenditure growth is usage, rather than the cost per service. So long as services are free or heavily subsidised at the point of delivery, there will be some pressure for overuse.

Unless there is an increase in the supply of resources dedicated to providing health care, the result of unmet demand will be ‘queuing’. People will find they cannot make an immediate GP appointment and people with non-urgent needs will be put on to hospital waiting lists while more important cases are attended to. Although waiting times command media attention and political criticism (the media often confuse queue lengths with waiting times), a health care system in which everyone could be attended to immediately is neither practical nor affordable. A waiting list allows scarce and expensive resources (medical specialists, nurses, diagnostic equipment) to be allocated to those who benefit the most. If there were so much spare capacity and those resources were underutilised for want of demand, that would be wasteful.

As we age we use more health care, and Australia’s population, although young by world standards, is ageing. Over the long term Australians are having fewer babies, immigration as a proportion of the population is falling, and we are living longer. It should be noted, however, that older Australians now are much healthier than they were a generation or two ago. Some health care costs, such as those associated with treatment of cancer, tend to be concentrated in the last few years of life, and if we live longer those costs are deferred.

Another driver of health care costs, often mentioned, is new technology. In most industries new technologies result in unit cost reduction, and it is certainly the case in health care, as in other industries, that information and communication technologies have helped reduce administrative costs. But there is also a flow of expensive technologies that offer new opportunities to diagnose or cure diseases or to ameliorate their effect, particularly pharmaceuticals. Technologies based on genetic manipulation and bespoke treatment for individuals are just emerging.

Some technologies that have developed and been refined in recent years, such as magnetic resource imaging (MRI), allow for earlier detection of conditions than would have been possible in times past. Early detection of conditions can save lives, allowing for timely and low-cost interventions (such as the removal of small cancerous growths) or can promote changes in lifestyle. But such diagnostic improvements can also lead to excess treatment of conditions that pose little threat in themselves, such as slow-growing tumours that would be overtaken by other causes of death.

Achieving value-for-money in health care

Both in their own role in funding health care, and in their broader role in helping people make well-informed decisions with their individual resources (a consumer protection function), governments are concerned with achieving value-for-money in health care.

A prime concern is to ensure that health care interventions – pharmaceuticals, operations – are effective. Do they achieve what they are intended to achieve? Clinical trials of pharmaceuticals are about establishing a new drug’s effectiveness, including detection of unexpected or undesirable side-effects. Similarly, there can be evaluations of operations to find which surgical procedures are most effective or whether pharmaceutical treatments can substitute for surgery, for example.

As a general rule, governments seek evidence on the effectiveness of health care interventions. The gold standard, as in other areas of public administration, is ‘evidence-based policy’. But it is a tough standard in health care. Research is difficult and expensive, in part because there are not standard conditions and there are not standard procedures. And there are ethical considerations in experiments involving people: is it ethical to conduct control experiments in which some patients are given one form of operation while others are given another form?

Even when the effectiveness of a form of treatment is established, the question of value-for-money arises. A new pharmaceutical may be very effective in prolonging the life of cancer sufferers, but if the drug is very expensive, and if the prolongation of life is only short, could scarce public money be better directed to where more health benefits could be enjoyed?

Such considerations concern the basis of policy-makers’ job assignment in a democracy. In the regulations they design or implement, or in the advice they give governments, can they differentiate between the needs of different people? Can they make hard and cold evaluations that would lead to a certain person being denied a life-extending pharmaceutical so that a limited budget can be spent on suicide prevention for adolescents for example?

In one frame, such considerations involve the policy maker having to say one life is worth more than another. In another frame, however, it is simply a question of the best allocation of scarce resources. A road authority with a limited budget and a brief to make roads safer would be remiss if that money were not spent on areas where the best outcomes could be achieved. Similarly, in evaluating health interventions, policy makers strive to find value-for-money in terms of outcomes. Such is the essence of cost–benefit analysis, a basic technique in the policy maker’s toolbox.

What therapies give the best outcomes and what do they cost? One measure is to consider how many extra years of life, on average, result from a therapy with a given cost. A more refined analysis is to apply some weighting based on the quality of those life-years. One such metric is the health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE) – the average time an individual can live without disease or injury.15 Another is the quality-adjusted life year (QALY), where a weight between 0 (death) and 1 (ideal health) is assigned, and yet another is the disability-adjusted life year (DALY).

While such metrics implicitly put a value on life, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) qualifies the use of such metrics with the statement: ‘However, the use of health state preferences and DALY or QALY measures to quantify loss of health or health gain carries no implication that society will necessarily choose the maximisation of health gain as the main or only goal for the health system.’16

Whatever form of evaluation is used, it is probable that in coming years, as techniques of data capture and analysis improve, more evaluative material will become available in the health systems.

The changing nature of health care – from acute conditions to chronic conditions

Partly as a result of changed lifestyles, and partly as a result of new therapies, the nature of health care has been changing over the long term.

Over most of the 20th century health care was mainly about curing what are known as ‘acute’ conditions, such as infections and injuries. As new pharmaceuticals became available, and as regimes of treatment improved, conditions which were once fatal became curable, or at least manageable. For example, in the 50 years to 2017, the cardiovascular disease death rate in Australia has fallen by 82 per cent.17 Some of this improvement is because of lifestyle improvement, some is because of early detection, and some is because of clinical management of people with heart disease or risk factors.

This means that many more people, particularly as they age, are living with conditions that in earlier periods would not have been survivable. Much of the task of health care has been a shift from curing acute conditions to management of ‘chronic’ conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and dementia.

As people live longer with manageable chronic conditions, the boundary between health care and care of the aged becomes less clear. This blurring of boundaries is described by a former head of the Health Department as a ‘major shift in demand underway because of Australia’s ageing population, with chronic illness and the frail aged now dominating the burden of disease’.18 In high-income countries, while heart disease and stroke remain the leading eventual causes of death, the incidence of death from Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and other dementia has trebled over 20 years.19

The political economy of health care

Australia’s set of health care arrangements is complex – so complex that it would be inaccurate to call it a ‘system’. The term ‘system’ implies a degree of deliberate design to ensure that all the parts come together and that they operate according to the same principles. But Australia’s health care arrangements are fragmented, each of the main parts having its own provenance.

These arrangements have been shaped by competing ideologies, competing interest groups, the inertia of established practices, historical division of Commonwealth–state responsibilities, and constraints imposed by interpretations of the Australian Constitution.

Civil conscription and the British Medical Association

Although the Commonwealth had been involved in public health and in health care for soldiers and veterans, it was in the postwar years that it was to become strongly involved in health care. Well before the Pacific War ended, the federal government had been planning a comprehensive national welfare scheme that was to include health services, a basic feature of which was provision for a salaried (rather than fee-for-service) medical service, similar in ways to Britain’s National Health Service.

Such an extension of Commonwealth powers met with fierce opposition from the British Medical Association (BMA), the organisation representing Australia’s medical practitioners. Calling on the emotionally charged conflicts about military conscription in the 1914–18 war, the BMA presented the idea of a UK-style single-payer national scheme as a form of ‘civil conscription’.

Partly to buy peace from the BMA, and partly to consolidate its authority, following a High Court disallowance of the Commonwealth’s authority to make laws on certain social services, the Chifley Labor government put forward a constitutional amendment to give the Commonwealth powers to make laws for ‘the provision of maternity allowances, widows’ pensions, child endowment, unemployment, pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, medical and dental services (but not so as to authorise any form of civil conscription), benefits to students and family allowances’. The amendment, with its ‘no conscription’ carve-out, was easily passed.

At the same time the Menzies Liberal opposition was strongly opposed to any tax-funded scheme, preferring a contributory scheme for health insurance.

Hence were established the ideological and interest-group divisions which frame health policy to the present.

The other constraint on coherent policy has been division of Commonwealth– state responsibilities, because long before the Commonwealth even existed the states were involved in funding and providing public hospitals.

So rather than a coherent, integrated health system, with all components working together under the same design principles, Australia has a set of arrangements, some private sector, some government, some Commonwealth, some state, some free at the point of delivery, some with out-of-pocket expenses, some universal, some means-tested. They come together in a process that health economist Sidney Sax called ‘a strife of interests’.20

Seventy years of muddling through

Charles Lindblom coined the term ‘muddling through’ to describe a policy development process whereby policy makers build on what has gone before, even if the resulting policy does not align with what they have designed from a blank slate.21 It’s analogous to the way a series of additions may be made to an old house, in preference to pulling it down and starting from scratch.

While the Chifley government was thwarted in its attempts to develop a universal tax-funded health system, in 1948 it managed to introduce the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), initially providing a limited number of free life-saving and disease-preventing drugs, using the purchasing power of government to secure reasonable prices. The Menzies (Liberal–Country Party Coalition) government, elected in 1949, pragmatically retained and extended the PBS, and, apart from the introduction of a co-payment in 1959, the essential architecture of the PBS remains largely unchanged.

An important provision of the PBS is the use of cost–benefit analysis to decide the price at which pharmaceuticals will be listed and therefore subsidised. If the supplier cannot meet the Commonwealth’s price, the drug does not become listed. Because the manufacturing cost of most drugs is low, most companies agree to listing at the Commonwealth price. Pharmaceuticals are similar to computer software, in that almost all of the cost is in development, while the per-unit cost is very low.

This is the only case of the Commonwealth using its purchasing power to set prices and to regulate what will and will not be paid for or subsidised. Politically it’s easier to take on the largely foreign pharmaceutical firms rather than the local medical lobby.

The next major initiative was by the Whitlam (Labor) government, in office from 1972 to 1975. It introduced a universal tax-funded scheme known as ‘Medibank’ (not to be confused with the private insurance firm of the same name). Its main elements were free access to public hospitals and a range of other services, most notably free or heavily subsidised access to medical services. Medical practitioners would be paid on a fee-for-service basis, and would remain in private practice, thus avoiding the ‘no conscription’ constraint. Hospitals and their funding remained under state control, with funding negotiated in a series of agreements between the Commonwealth and the states.

When it was introduced to parliament Medibank met with furious opposition, from the medical lobbies, the private health insurers and the Coalition opposition who effectively controlled the numbers in the Senate. Medibank became law only in 1974 following a double dissolution election and a joint sitting of parliament.

The Fraser (Coalition) government, in office from 1975 to 1983, demolished Medibank in a series of small steps, and by 1979 health funding had essentially reverted to the pre-1974 model, relying on private insurance. Publicly funded medical benefits were reduced, free access to public hospitals was restricted to those meeting means tests, and an income tax rebate of 32 per cent was introduced for people with private health insurance.

The Hawke–Keating (Labor) government, elected in 1983, reintroduced Medibank under the name ‘Medicare’, and eliminated subsidies for private health insurance. Private health insurance had achieved 68 per cent coverage under the previous government’s incentives. By the time the Hawke–Keating government lost office in 1996, coverage had fallen to 33 per cent.

The Howard (Coalition) government set about restoring a raft of incentives to support private health insurance, many of which were designed to entice younger people to take insurance to subsidise older members. Almost straight away coverage rose to 45 per cent of the population and it peaked at 47 per cent in 2015 before starting to fall back. The Howard government’s reversal of Labor’s policy was less severe than the reversal that had occurred under the Fraser government: notably it did not apply a means test to access public hospitals, which remained free, but there was a subtle expectation, encouraged by taxation incentives, that the better-off would use private insurance to buy private care in private hospitals. Ideologically it was a partial shift from health care as a universal service, to a service for the needy, sometimes referred to as a ‘two-tier’ system.

The Rudd–Gillard (Labor) government, in office from 2007 to 2013, maintained support for private insurance and the Abbott–Turnbull–Morrison (Coalition) government essentially maintained the status quo. The election of 2016 had seen the retention of Medicare as a major issue.

Labor governments are inclined to stress universalism as a principle underpinning health care policy. That is, the idea that all should have access to health care, regardless of means, and that clinical need rather than income or wealth should determine allocation of scarce resources. Coalition governments tend to stress ‘choice’, and the idea that government services should be more directed to those in need. Some policy analysts tend to classify health care policy as ‘social expenditure’, evaluating it in terms of equity outcomes, while others tend to see health care in terms of correcting market failure, assessing it on economic criteria.

The muddle

While in most high-income ‘developed’ countries there is a degree of stability in health care financing, that is not the case in Australia. A series of policy reversals, modifying but not redesigning existing policies, has left Australia with a patchwork and complex set of arrangements.

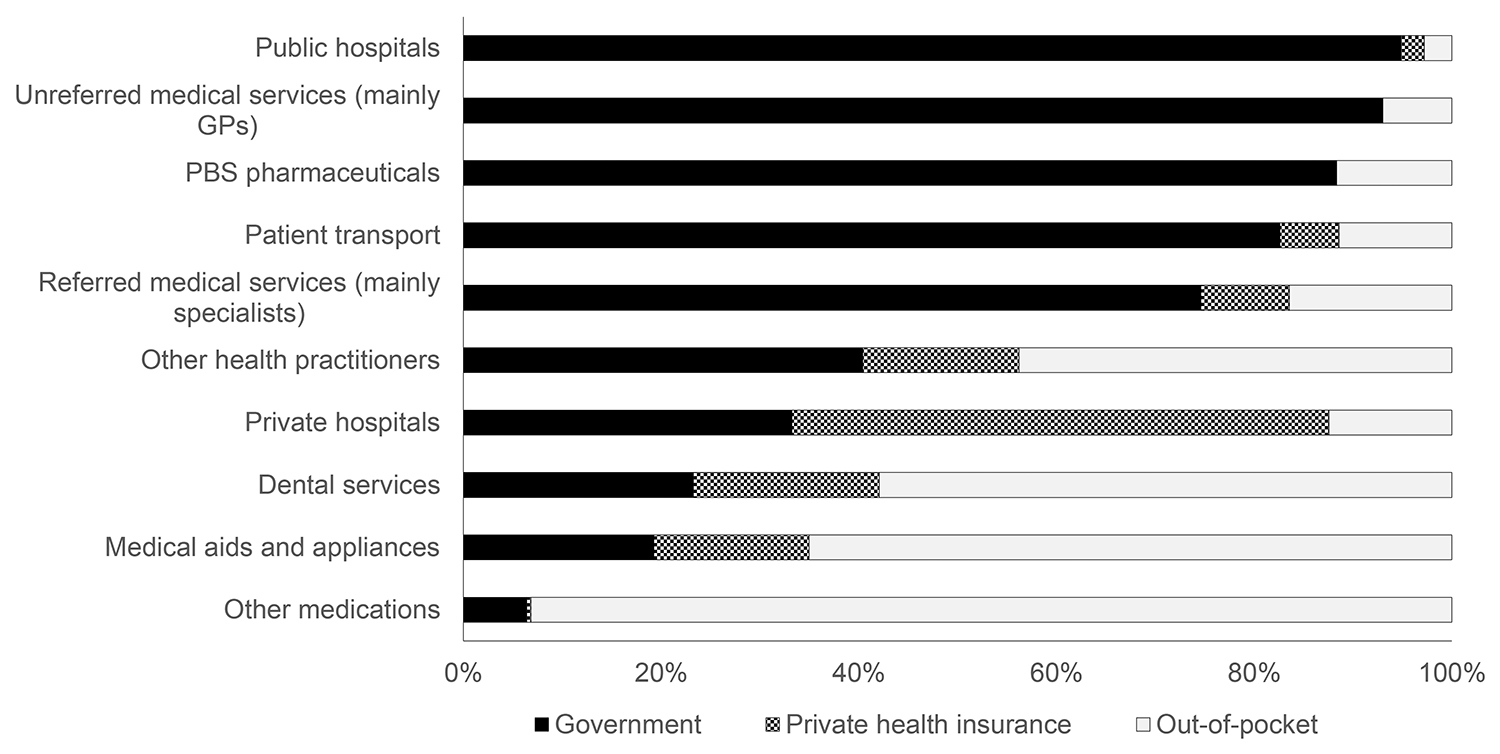

Figure 3 shows one face of this complexity – the ways different health care programs are funded. In aggregate terms Australians draw on governments, mainly the Commonwealth, for about 70 per cent of their health care costs, private insurers for another 10 per cent, and their own pockets for the remaining 20 per cent. But this varies tremendously between programs. Public hospitals are essentially free, funded through joint Commonwealth–state agreements. For pharmaceuticals, patients must make a capped co-payment, with the co-payments varying according to patients’ means. For dental services, most of the payment is from patients’ own funds, with some through subsidised private insurance and programs for targeted groups. Private hospitals are funded mainly through private insurance, the Commonwealth contribution a set of subsidies which make up about a third of the net cost.

Figure 3 Health expenditure by source of funds, 2016–17. Source: data from AIHW 2018b, table A3. Recurrent expenditure only, not including research, administration, public health and funding from other sources comprising 3% of expenditure.

Such complexity inevitably leads to duplicated bureaucracies and high transaction costs. It leads to gaming and perverse incentives when different government agencies (sometimes in different tiers of government) try to meet their own financial targets by shifting costs to different programs. For example, payments for pharmaceuticals come out of state budgets for patients in state hospitals, but out of the Commonwealth-funded PBS for others. And it probably leads to people seeking some care from services that are free or low-cost at the point of delivery (either through Medicare or private insurance), when other services with higher out-of-pocket costs would be more efficient in terms of overall costs and benefits.

Further, a lack of system integration means that people do not receive the timely attention. The Productivity Commission reported in 2015 an opportunity to get far more out of our health system through better use of measures that come into play before people become involved in expensive hospitalisation.22 Effective promotion of healthy lifestyles can reduce the overall demands on health care. Similarly, well-designed primary care – particularly care by GPs – can avoid some hospitalisations.23

Then there are problems in defining ‘health care’ and therefore what procedures are to be eligible for public subsidy. Should dietary supplements be included? Gyms? Acupuncture? Should some presently subsidised procedures be excluded? The boundary enclosing ‘health care’ can never be well defined, because it is determined not only by cost–benefit considerations, but also by community values.

Each part of our health care arrangements may be working well, but the concern of the Productivity Commission and of many health economists is whether these arrangements are coming together in the best way.

Those who are familiar with economic concepts would recognise the issue as one of the difference between technical efficiency and allocative efficiency. Each part may be operating in the most cost-effective way possible – that is, they may be achieving technical efficiency – but there could possibly be better outcomes overall if there were some reallocation of resources to achieve better performance from an overall perspective. That would be an improvement in allocative efficiency.

For example, there have been great strides in use of what are known as ‘diagnostic related group’ or ‘casemix’ payments in the way governments pay for public hospital services. Although the staff themselves may be salaried, the relevant state government pays a set amount for each defined procedure – so much for surgical treatment of a heart attack, so much for a caesarean section, and so on. It’s a form of ‘output-based funding’, aimed at making sure hospitals achieve best value-for-money or technical efficiency.

But even if public hospitals are doing as well as they can in terms of technical efficiency, it is still possible that there could be better health outcomes if more resources could be put into primary care or into promotion and prevention. Managerialist techniques concerned with efficiency in individual parts of a system can distract attention from the need to attend to the performance of the entire system, can lead to cost-shifting, and can often lead to a sub-optimal allocation of resources.

Improvements in technical efficiency will probably proceed with uptake of administrative technologies (where the health care sector still has some need for catch-up), such as electronic health records and better use of data, but there will always be constraints imposed by privacy concerns and the need for individual attention. Some aspects of health care, particularly where health care merges into aged care, will remain labour intensive, which means that as other sectors become lower-cost through labour-replacing technology, the cost of health care may rise faster than costs in other sectors of the economy, with implications for funding. Economists know this phenomenon as the ‘Baumol effect’.24

Conclusions

Despite inconsistencies, boundary problems and messy funding, Australians achieve good health outcomes. In an evaluation of the health care arrangements in 11 high-income countries, the Commonwealth Fund gave Australia fourth place – behind the UK, Switzerland and Sweden. Australia scores well on quality of care, but comparatively poorly on access. The access problems in Australia relate mainly to costs and difficulties paying medical bills, particularly relating to co-payments in private insurance.25

Many decades of incrementalism have delivered Australia a set of arrangements which work, but which, by most measures, could work better if the parts could be brought together as an integrated system, particularly in terms of Commonwealth– state divisions and in developing more coherent and equitable funding arrangements.

The adjustment of our arrangements from a focus on acute care to one based on chronic care is ongoing. Also there is still a slow transition from what once was a labour-intensive set of individual professional practices to a more technology-intensive service industry model, which will still have to meet community expectations of high-quality individual care and compassion. Some emerging technologies, based on genetic manipulation, could have profound effects on our health care arrangements, as well as opening up new ethical questions.

There may be scope for those with means to contribute more from their own pockets to their own health care. This is a normative question, which needs to be put to the community. Australians may opt for more sharing, or they may opt to pay more from their own pockets.

Whatever the outcome of such deliberations, there will almost certainly be a need to provide more collective funding for those with high needs or limited means. If governments are determined to pursue a ‘small government’ policy, they will probably try to achieve this collective funding through private health insurance, in spite of its costs and difficulties in achieving community rating, cost control and administrative efficiency. Otherwise the most equitable and efficient means of funding growing health care expenditure is through higher taxes.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2018a). Australia’s health 2018. Canberra: AIHW.

—— (2018b) Health expenditure Australia 2016–17. Canberra: AIHW.

—— (2017a). Health-adjusted life expectancy in Australia: expected years lived in full health 2011. Canberra: AIHW.

—— (2017b). Trends in cardiovascular deaths. Bulletin 141. Canberra: AIHW.

Baumol, William J., and William G. Bowen (1966). Performing arts, the economic dilemma: a study of problems common to theater, opera, music, and dance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Caiden, Naomi (2008). A new perspective on budgetary reform. Australian Journal of Public Administration 48(1): 53–60. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8500.1989.tb02195.x

Corscadden, Lisa, Jean-Frederic Levesque, Virginia Lewis, Mylaine Breton, Kim Sutherland, Jan-Willem Weenink, Jeannie Haggerty and Grant Russell (2017). Barriers to accessing primary health care: comparing Australian experiences internationally. Australian Journal of Primary Health 23(3): 223–8. DOI: 10.1071/PY16093

Davis, Karen, Kristof Stremikis, David Squires and Cathy Schoen (2014). Mirror, mirror on the wall: how the performance of the U.S. health care system compares internationally. Washington DC: Commonwealth Fund.

Department of Health (2019). Annual Medicare statistics. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/Annual-Medicare-Statistics

Lindblom, Charles E. (1959). The science of ‘muddling through’. Public Administration Review, 19(2): 79–88. DOI: 10.2307/973677

Mathers, Colin, Theo Vos and Chris Stevenson (1999). The burden of disease and injury in Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

McMichael, Anthony J. (2017). Climate change and the health of nations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2017). Health at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/health-at-a-glance-19991312.htm

Podger, Andrew (2018). Government–market mixes for health care. In Mark Fabian and Robert Breunig, eds. Hybrid public policy innovations: contemporary policy beyond ideology, 185–203. New York: Routledge.

Productivity Commission (2015). Efficiency in health. Commission Research Paper. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

Rawls, John (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sax, Sidney (1984). A strife of interests: politics and policies on Australian health services. Sydney: George Allen & Unwin.

Starfield, Barbra (2005). Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Millbank Quarterly 83(3): 457–502. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

Wilkinson, Richard, and Michael Marmot, eds (2003). Social determinants of health: the solid facts. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Wilkinson, Richard, and Kate Pickett (2009). The spirit level: why greater equality makes societies stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2018). Global Health Estimates 2016: deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2016. Geneva: WHO.

World Population Review (2018). Countries by median age 2018. http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/median-age/

About the author

Ian McAuley is a retired lecturer in public finance, University of Canberra. Because of the prominence of health care in government finance, he has taken a strong interest in the way Australia and other countries finance health care – their mix of direct payments, public insurance and private insurance. He has delivered several conference papers on health funding and is the author, with Miriam Lyons, of Governomics: can we afford small government? (2015).

1 McMichael 2017.

2 AIHW 2018a, 256.

3 Wilkinson and Marmot 2003.

4 Wilkinson and Pickett 2009.

5 OECD 2017.

6 World Population Review 2018.

7 AIHW 2018a.

8 AIHW 2018a, 83.

9 Sax 1984, 25.

10 OECD 2017.

11 Rawls 1971.

12 Corscadden et al. 2017.

13 OECD 2017.

14 AIHW 2018b.

15 AIHW 2017a.

16 Mathers, Vos and Stevenson 1999, 12.

17 AIHW 2017b.

18 Podger 2018, 197.

19 WHO 2018.

20 Sax 1984.

21 Lindblom 1959.

22 Productivity Commission 2015.

23 Starfield 2005.

24 Baumol and Bowen 1966.

25 Davis et al. 2014.