Governance of the COVID-19 crisis in Australia: public policy during crisis

Key terms/names

Australian Health Protection Principal Committee, COVID-19, Communicable Diseases Network Australia, Council of Australian Governments, crisis, crisis preparation, crisis prevention, crisis recovery and learning, crisis response, Department of Health, JobKeeper, governance, lockdown, federalism, public health, vaccination

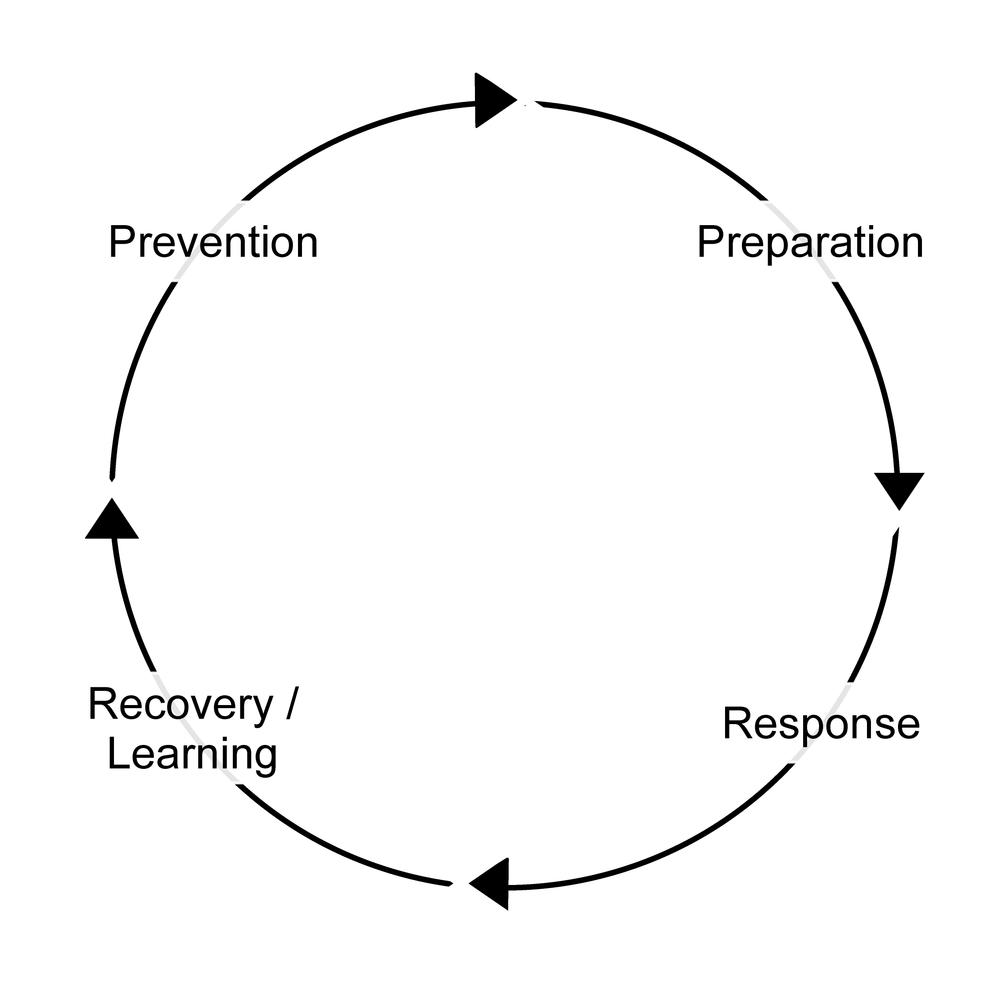

COVID-19, a coronavirus emerging in late 2019, quickly snowballed into a global public health crisis of scale not seen in generations. Crisis, ‘a set of circumstances in which individuals, institutions or societies face threats beyond the norms of routine day-to-day functioning’,1 is a situation that governments must face as both an objective fact and subjective perception. These dual dynamics of fact and perception have shaped the responses of Australian governments to COVID-19 at both the federal and state level. Whilst there are many ways we can examine the policy process (see Weible and Sabatier’s Theories of the policy process for an excellent introduction),2 a relevant introductory method to examine the governance of COVID-19 in Australia is the crisis management cycle, illustrated in Figure 1.3 This applies the cycle of prevention, preparation, response, and recovery and learning, and points to the role of actors, institutions and policy design, and tools in crisis management across these stages. The chapter demonstrates that crisis evaluation is a tricky and political activity characterised by contested perceptions and complicating evidence.4

Figure 1 The crisis management cycle.5

The crisis management context

It is important to understand the context of Australia’s COVID-19 governance response. Of particular significance are institutions, actors and dominant modes of governance that inform policy design. This section briefly introduces these factors as situating contexts that need to be considered when assessing Australia’s response to COVID-19.

The first point to consider is Australia’s institutional context. Australia is a settler society, established by the British and imposed violently upon Indigenous peoples. Australia adopted the Westminster tradition of responsible government ‘with a fused executive and legislature, ministerial responsibility, and a separate public service’6 but also adopted elements of the American system with federalism, the constitutionally enshrined division of power between a central government and sub-national governments.7 The politics, contestation and bargaining that these institutional structures produce across layers of government must be incorporated into our assessment.

These institutions are populated by actors in positions of decision-making power. Whilst the institutional context provides a decision-making matrix that actors must operate within, their approaches and strategies matter too.8 Federalism, and the sharing of governance responsibilities across layers of government, multiplies the number of actors that need to be incorporated into the decision-making process – cabinets of ministers at federal and state levels, and the attendant ministerial portfolio public servants – and complicates the co-ordination of a crisis response.

Finally, governance itself needs to be assessed. Governance is the trend in recent decades away from top-down, state-led decision making and policy implementation. Instead, governments have tended to retain the ultimate say over policy decision making and implementation, whilst also accommodating less hierarchical decision making and policy delivery, involving a greater plurality of actors within governments, markets and the third sector.9 Modes of governance refer to the different emphases of governance and policy delivery, with state-led governance, market-oriented governance, and networked and third-sector governance.10 These government, market and network/third-sector modes of governance have all been mobilised by Australian governments during the pandemic and offer the final contextual factor under consideration.

In sum, institutions of responsible government and federalism provide a framework that multiple actors must operate within. These actors, at various levels of government, still retain choices regarding policy decision making and adopt modes of governance according to situational appropriateness and ideological preference.

Crisis prevention

Crisis prevention can be achieved if potential risks are first identified, evaluated and managed, but this may not always be possible. For instance, whilst the popular meaning of risk may operate as a synonym for danger, Wilkinson argues that we should think about risk in probabilistic terms – ‘a mode of thinking in which the costs and benefits of specific actions and discrete events are weighed in the balance.’11 On this basis, policy makers may well identify risks related to an action, assess them and identify that the risks they pose are tolerable. An example might be weighing the benefits of a hazard reduction burn in a remote location versus the low probability posed by a bushfire in this remote location impacting infrastructure or posing a danger to human life. In these circumstances, governments often conclude that the risk posed by a fire is present, but tolerable, and choose not to do a hazard reduction burn.

In other circumstances, we may have the means to avoid the risks associated with crises and the means to achieve this. These kinds of risks are usually associated with a form of human behaviour that can be controlled or mitigated. An example might be introducing financial laws that regulate the risky loans practices by lenders to borrowers that could not afford the repayments, ultimately contributing to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2007–08. But ‘pure’ risks, like natural disasters or pandemics, are usually inherent and unavoidable and consequently need to be controlled or contained, rather than tolerated or completely avoided.12

The federal Australian government assessed pandemics to fall into this ‘unavoidable’ category, recognising prior to the COVID-19 pandemic that ‘it is inevitable that the world will face another influenza pandemic. While there is no certainty about where or when the next one will occur, Australia must be prepared.’13 As such, the prevention measure in place prior to the outbreak of COVID-19 was a surveillance program to monitor for communicable disease and pandemic influenza outbreaks. Reflecting Australia’s federal system, the Commonwealth was responsible for monitoring for communicable diseases domestically and internationally and liaising diplomatically with neighbour nation-states regarding this monitoring. The states and territories were responsible for collecting influenza data from their health systems to contribute to the national picture of pandemic preparedness. The Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) peak body, and its Communicable Diseases Network Australia (CDNA) sub-committee were responsible for co-ordinating this surveillance across Australia’s system of federalism.14 Notably, more authoritative COVID-19 management policy tools, like ‘enhanced border measures’ were conceptualised as pandemic response measures, rather as pandemic prevention measures in the Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (2019) plan.

The surveillance and prevention stage was short lived during the COVID-19 crisis. The World Health Organisation (WHO) received notification of ‘pneumonia of an unknown cause’ from the Chinese government in late 2019 and notified all member states, including Australia, in early January 2020.15 Australian authorities acknowledged the potential risk posed by COVID-19 and quickly shifted to the response stage. On 19 January, the Australian Chief Medical Officer publicly acknowledged COVID-19, the National Incident Room in the Health Department was activated on 20 January and ‘human coronavirus with pandemic potential’ was added to the Biosecurity (Listed Human Diseases) Determination (2016) on 21 January.16 These acts triggered several pandemic mitigation measures that had been planned. This contingency planning is considered below.

Crisis preparation

Crisis planning is both an objective process and one of perception and evaluation. As above, assessing and planning for risk involves an assessment of the nature and likely impact of the crisis, both of which are uncertain and based upon probabilistic reasoning. Evidence may be incomplete or based upon models underpinned by partial consideration of potential variables, and is weighed against more political considerations of competing priorities and limited resources.17

Nonetheless, an imperfect crisis plan is better than no crisis plan.18 Crisis planning should integrate all key institutions in a ‘whole of government’ approach that joins up the key actors and organisations in government and connects them to relevant market and third-sector organisations and actors outside of government. Kamradt-Scott argues that an influenza pandemic’s ability to disrupt national and global society and economy means that a response cannot be limited to dedicated emergency agencies.19 This notion is reflected in both Australia’s pandemic and disaster standing plans and arrangements, which dedicated considerable effort into whole-of-government and joined-up planning across Australia’s system of federalism.

Significant contingency planning for disasters, crises and pandemics had been completed by the Commonwealth government prior to the outbreak of COVID-19. Co-ordination of influenza pandemic planning across Australia’s federal layers of Commonwealth, state and territory governments has been in place since 1999. The last major update was in 2014, incorporating lessons from H1H1 ‘swine flu’ pandemic of 2009, and a minor update to Australia’s pandemic planning was delivered in August 2019: Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (AHMPPI). Whole-of-government language was emphasised throughout the plan and the logic was explained as: ‘Maintaining essential services may require a whole-of-government response, incorporating agencies at the Australian Government and state and territory government level’.20

The key documents in Australia’s standing pandemic plans and related health and crisis management documents are summarised in Table 1.

But plans are only part of the preparedness mix. Also important is the testing and simulation of crisis responses. Australia was something of a world leader in pandemic planning and preparation during the 2000s, initiating the governance frameworks outlined above and running full-scale simulations of pandemic scenarios. But a combination of changing priorities and austerity after the GFC, combined with the relative mildness of H1N1 in 2009, saw a de-prioritisation of this scenario training, a situation some have identified as contributing to confusion over responsibilities between layers of government during the early months of the COVID-19 crisis in Australia.21 Nonetheless, the 2019 Global Health Security Index, which benchmarked the health security and related capabilities of states, ranked Australia fourth out of 195 countries in terms of preparedness for pandemics and their consequences prior to the crisis.22 So, whilst pandemic preparedness had evidently needed to compete with other government priorities in Australia prior to COVID-19’s emergence, comprehensive planning and (dated) testing of that plan was in place.

Crisis response

Crises vary in their length and impact, which in turn affects the nature of the acute phase of the crisis response. For instance, the acute phase of crisis events like an earthquake or a terror attack may be over quickly and limited to localised spaces. In these instances, the crisis response stage may be largely limited to securing the area and managing casualties, before shifting promptly to recovery. In other ‘pure’ crises, like fires, floods and pandemics, the crisis and its effect may continue for weeks, months, or in the case of COVID-19, years. In these circumstances, when control over events is limited and precarious, crisis management becomes a process of ‘coping through’ as unharmed as possible.23 The crisis context, improvisation of plans and responses, response leadership, and knowing when to act, and by how much, all influence the outcome of crisis management. Australia’s response to the acute phase of the COVID-19 crisis is evaluated against these factors below.

The acute stage of the COVID-19 crisis in Australia, and its response, is here defined as the ‘pure’ stage of the crisis, the 12-month period from the emergence of COVID-19 in January 2020 to February 2021, when the Sydney Northern Beaches cluster began to dissipate and COVID-19 vaccines could reasonably have been expected to have become available to mitigate the crisis and move the response into the recovery and learning stage. The context of the crisis was Australia encountering COVID-19 at the tail-end of the Black Summer bushfire crisis, an event that saw the most widespread and destructive fires in Australian recorded history and widespread criticism of the federal Coalition government’s handling of this disaster.24

Despite this context, Australia quickly responded to the COVID-19 crisis and activated several pandemic arrangements, adopting (after some contestation) an ‘aggressive suppression’ strategy of COVID-19 management. The January 2020 activation of the National Incident Room in the Health Department and adding of COVID-19 to the Biosecurity (Listed Human Diseases) Determination triggered a number of pandemic arrangements, ‘including daily meetings of the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) and meetings of federal, state and territory health ministers. On 25 February, the Australian government activated the National Communicable Disease Plan, and two days later, the COVID-19 Plan was agreed upon and activated by the National Security Committee of Cabinet.’25 Australian governments also quickly adapted their crisis and pandemic planning to the COVID-19 crisis. This initial adaptation is summarised in the response documents in Table 2.

What this adaptation reflects is negotiation of Australia’s federal institutional features and whole-of-government mode of crisis governance to suit the leadership styles and political preferences of Australia’s federal, state and territory leaders. Whilst Prime Minister Morrison demonstrated a masculine and semi-presidential leadership style, he has also had to negotiate with state counterparts, who brought their own leadership styles and party allegiances (five state and territory governments were Labor-controlled and three Liberal- or Liberal/National-controlled).26

The National Cabinet was one forum for the co-operative and combative relations of federal, state and territory relations to play out. The National Cabinet was perceived to streamline intergovernmental relations, replacing the Council of Australian Governments (COAG). National Cabinet was seen as a less bureaucratic and more personalised forum, free from the more formal agenda and process constraints of COAG. Whilst not a true cabinet,27 it was argued that this adaption of institutional arrangements was necessary given the complexities of sustained and ongoing crisis co-ordination across diverse Commonwealth, state and territory jurisdictions and leaderships. National Cabinet largely worked well during the acute phase of the crisis ‘effectively managing the “flattening of the curve” and engendering public trust in the intergovernmental response’28 via mostly co-operative federal relations, despite prominent tensions with Victoria during their second wave outbreak from June to October 2020, which saw 112 days of lockdown and a four-month closure of the border with NSW. This outbreak saw some of the most stringent lockdown regulations and enforcement in the country up until that point, perhaps most controversially including a ‘hard lockdown’ of 3,000 residents in nine public housing towers that was imposed without notice and prevented residents from leaving. The Victorian Ombudsman later found the public housing lockdown’s timing was not based on health advice and violated Victorian human rights laws.29

Arrangements were also developed to incorporate market and third-sector actors into the governance of the acute phase of the crisis response. For example, the National COVID-19 Coordination Commission (NCCC) (subsequently renamed the National COVID-19 Commission (Advisory Board) (NCC)) was created to incorporate business and government leaders into an advisory forum. The NCC initially mobilised the networks and experience of the committee members to troubleshoot personal protective equipment, supply chain, and freight and transport issues, as well as connect laid-off workers to emerging labour shortage needs. As restrictions began to ease, the NCC switched focus to providing support and information for businesses as they reopened and to providing an advisory role to government regarding the long-term economic recovery from COVID-19. Here it attracted controversy by advocating for a ‘gas-led recovery’ from the economic downturn caused by COVID-19 and the potential conflicts of interest this posed for NCC members.

Another example was the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group on COVID-19, who developed and delivered the MPATSI (see Table 2). The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group on COVID-19 incorporated Indigenous public sector and third sector stakeholders and public health experts. The group recommended policies co-designed with Indigenous peoples, including legislative changes to minimise travel to remote and vulnerable communities, culturally specific health promotion materials, infectious disease modelling, epidemiological tracking, rapid testing, and infrastructure and workforce preparations.30 As evidence of the success of these efforts during the acute phase of the crisis response, as of 28 February 2021, there had only been 150 cases of COVID-19 amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, representing 0.5% of total cases.31

Other prominent COVID-19 policies centred on the plethora of authoritative policy tools adopted by the Commonwealth and states and territories to deal with case numbers. The Commonwealth introduced border controls which limited or banned travel to and from the country and two-week quarantine periods for returned travellers. State and territories introduced various levels of stay-at-home orders, which limited visitation and movement of people within states and, more controversially, closed borders between states. This massive use of state power was also augmented with test, trace and isolate policies that sought to identify positive cases through mass public testing, track their movements in the community and order them to stay at home while infectious.

Finally, this acute period of the crisis also saw the Commonwealth, states and territories introduce various payments to businesses and individuals affected by lockdown orders. This prominently included the Commonwealth JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments that aimed to ameliorate the economic impacts of the crisis. JobKeeper provided funds to businesses to keep employees on, rather than to lay them off, and JobSeeker doubled unemployment benefits for those that found themselves out of work.32

These measures proved to be quite effective when assessed against the aims of the ‘aggressive suppression’ strategy, with only 64 COVID-19 cases in the country in the fortnight leading up to 28 February 2021 and no deaths, and with the cumulative case count being 28,937 with 909 deaths. We can compare this with some of the most hard-hit countries during February 2021:

The highest number of new cases in the past four weeks was in the United States of America (2,498,366; 7,527 new cases per 1 million population), followed by Brazil (1,337,117; 6,290 new cases per 1 million population), France (544,857; 8,078 new cases per 1 million population), the Russian Federation (395,640; 2,743 new cases per 1 million population), and the United Kingdom (374,431; 5,569 new cases per 1 million population). The highest number of deaths from COVID-19 in the last four weeks was reported in the United States of America (73,587), followed by Brazil (31,169), Mexico (27,895), the United Kingdom (17,134) and Germany (13,100).33

Unsurprisingly, given this comparative picture, there is evidence that Australian public opinion largely agreed with these measures and was satisfied with their level of effectiveness, with trust in government and the government response increasing during this acute phase of the crisis.34 In sum, the governments of Australia had managed to ‘cope through’ the acute phase of the COVID-19 crisis quite effectively, keeping case numbers and deaths comparatively low and sustaining a high level of trust in their COVID-19 management policies.

But what does Australia’s COVID-19 management success during this acute phase look like when assessed against other policy outcomes? The top-line focus on Australia’s success in managing case numbers and deaths masks the controversies and contestation evident during this acute phase of the crisis, especially surrounding the use of state power and authority. For instance, international border restrictions limited both the ability of Australian citizens and residents to arrive in the country, and unusually, banned leaving the country without approval. This had the effect of stranding citizens and residents overseas and prevented others from leaving Australia to see overseas family and loved ones – a massive curtailment of the right to freedom of movement. Similar border closures were evident internally too, and ‘some main points of inter-jurisdictional or bureaucratic tensions were between states over border controls (particularly New South Wales and Queensland, and later with Western Australia) and in the blame games over who authorised (notably, NSW Health or the Australian Border Force) 2,671 passengers, including 110–120 sick passengers and crew, to disembark from the cruise ship Ruby Princess.’35 The states and Commonwealth also disagreed amongst themselves regarding responsibility for quarantine arrangements and the form those arrangements should take, notably regarding the use of hotels to quarantine returning travellers. National cabinet operated as a forum for contestation over these competing preferences and perceptions, and points to the differing aims, priorities, and accountabilities that existed between the states, and between the states and the Commonwealth, that can complicate a crisis evaluation.

As the acute phase came to an end, the focus shifted to vaccine procurement and distribution – the means to shift to the crisis recovery and learning phase of crisis management. The relative slowness of the vaccine rollout precipitated the challenges Australia faced as the Delta COVID-19 variant emerged in mid-2021. These developments demonstrate the precariousness of crisis management success and the caution we should exercise when attributing success to crisis governance.36

Crisis recovery and learning

At the time of writing (October 2021), the author finds himself emerging from the three-month-long Sydney Delta lockdown. This complicates any evaluation of the recovery and learning stage of the COVID-19 crisis – put simply, we are still in it. What is offered here is a conceptual outline of the difficulties of crisis evaluation and some initial impressions of the final stages of the COVID-19 crisis response in Australia. The recovery stage of the COVID-19 crisis is here defined as the period from late February 2021, when the means for COVID-19 recovery – vaccines – first began to be administered.

McConnell argues that crisis evaluation is inherently political, in that the questions we ask, and lens we adopt to answer them, are informed by the competing interests and agendas of the actors involved.37 McConnell develops a list of questions that any crisis evaluation must answer, a process that cannot avoid these inherently political judgments:

- Where do we set the boundaries of evaluation? Crises inherently draw in multiple actors, across layers of government, political parties, bureaucracies, and non-governmental actors in business and the third sector. Choosing to focus on only some of these actors and institutions will sharpen the focus of an evaluation, but will inevitably insulate some actors from accountability, too.

- What success benchmarks do we use and how do we weigh outcomes? Benchmarks for crisis management, and evaluation of success and failure against them, are difficult to establish objectively and may vary across time or place. Regarding COVID-19, the ‘aggressive suppression’ strategy in Australia has seen the focus on suppressing case numbers as a key measure of success. But others might point to the massive economic and social costs of achieving these low case numbers by lockdowns as a sign of failure. Another example is Victoria’s second wave, which may be viewed as a failure for getting out of hand or conversely as a successful suppression of an outbreak. The choice of which benchmark and outcome to use is informed by the perceptions, values and ideologies of the evaluator.

- How much weight do we give to shortfalls? Crisis management is rarely, if ever, completely successful on all possible measures. Crises lead to people being harmed or dying, test institutions and management processes to the extreme, and frequently cause mass inconvenience for the public. Weighing these shortcomings is another example of the inherently normative and political choices necessary to crisis evaluation.

- How do we address lack of evidence? Crisis evaluations rely on evidence to establish ‘hard facts’, but that evidence may be unavailable, contested, or partial. For example, cabinet confidentiality has prevented scrutiny of the health advice given by health officials to the NSW state government during the Delta outbreak of 2021. As such, we simply do not know if the NSW government acted fully or promptly on this expert health advice or not, complicating the response evaluation.

- Success for whom? Crisis, and crisis responses, have uneven social impacts. For example, there has been ample evidence from the Victorian second wave and Sydney Delta outbreaks that there was an outsized spread of COVID-19 cases, and more punitive lockdowns restrictions and policing, in locations with higher prevalence of socio-economic disadvantage.

- What period of time to evaluate? The COVID-19 response in Australia neatly demonstrates the difficulty of assessing crisis management across time. Australia was remarkably successful at managing COVID-19 in 2020 and the first half of 2021. As discussed below, the vaccine rollout and the emergence of the Delta variant has complicated that assessment of overall crisis management success.

As crisis evaluators, our answers to these six questions will be inevitably informed by our own values, ideologies, and perceptions, leading to a particular and political assessment. That does not mean our evaluations have no value, simply that we should be aware of the potentially hugely consequential outcomes of our assessments and the ways they can inform or limit policy learning. While it may be relatively easy to identify ‘first-order’ causes of crisis, like faulty parts that cause a train crash or an illegal gathering attended by COVID-19 positive cases that create a super-spreader incident in a city, it is rarely satisfactory to a public that demands fulsome answers and accountability.38 But an examination of ‘second-order’ causes, for example leadership decisions, organisational culture, failure to communicate, or budget cuts, is prone to the contestation and politics identified above. As such, learning from crisis may only provide the basis for a wider political debate about how to manage crises, rather than clear-cut answers about who to hold to account and how to respond to similar events in future.39

Australia’s vaccine rollout: what went right and what went wrong?

I here attempt a brief and preliminary evaluation of Australia’s vaccine rollout, a part of the crisis recovery and learning stage. Australian COVID-19 management success in 2020 can be explained by Australian federal, state and territory governments’ willingness to use authoritative policy tools (lockdowns, restrictions, enforcement) and people's trust in, and willingness to comply with, this response. Why has this broken down with the vaccine rollout in 2021? I contend that there has been a shift in the necessary policy tools – from authoritative tools that have proven to be less successful against the Delta variant, to organisational tools (putting in place the government and non-government institutions and procedures to deliver vaccines into arms across Australia’s system of federalism) and information tools (political communication from governments about the vital necessity of vaccine in press conferences and advertisement campaigns).40

The primary first-order difficulty has stemmed from the vaccine rollout design, heavily reliant as it was on a relatively narrow range of vaccines, and especially the prioritising of local manufacturing of AstraZeneca as the cornerstone vaccine. There were prudent reasons behind the choice of AstraZeneca: it was comparatively cheap, could be easily transported and stored in standard medical fridges, and local manufacture was possible. mRNA vaccines like Pfizer’s, on the other hand, were more expensive, required specialised storage and Australia lacked the ability to manufacture them locally. But what may have been prudent at the time has faced challenges, centring on the perceived efficacy and safety of AstraZeneca and the delivery of vaccines to priority communities, and then the populace at large. Under this picture, the Commonwealth government’s vaccine acquisition design was the primary cause of the difficulties with the vaccine rollout.

But consideration of second-order causes of the vaccine rollout challenges complicates this simple picture of causality. There were issues with crisis communication, with the federal government promising AstraZeneca numbers it could not access due to the difficulties with accessing AstraZeneca from Europe, and before local manufacture had begun, in early 2021. There was the Commonwealth’s amplification of the risks of AstraZeneca, based on ATAGI advice, over the need to get vaccinated. State leaders and chief health officers also talked down AstraZeneca publicly and influenced National Cabinet decision making about the age rules surrounding AstraZeneca access, which had the effect of restricting vaccine access for younger people. All this helped sow AstraZeneca hesitancy and ultimately contributed to a large portion of the population waiting for Pfizer vaccines that were not initially available.

Organisational tools to deliver the vaccines were more successful, as demonstrated by the rapid vaccination of the population in the second half of 2021. But significant shortfalls have also existed, with this uptake being slow to start and gaps in vaccine coverage amongst vulnerable and prioritised populations, like the elderly, the disabled, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. These delays and gaps had an outsized effect on the vulnerable during the Delta outbreak.

Other contextual factors further complicate this evaluation. Public figures, media reporting and international discourse (especially from European Union countries), played a role in sowing AstraZeneca hesitancy too. Vaccine supply in the early stages was also largely out of the hands of Australian governments, though perhaps the Commonwealth could have moved more quickly to secure supply in 2020. We might speculate that in future, the rapid rollout of vaccines during the Delta outbreak in 2021 may overwhelm memories of the leisurely pace of vaccinations in the first half of 2021. On the other hand, Australian governments have made mistakes and misjudgements when communicating the efficacy, safety and necessity of AstraZeneca, the cornerstone of the policy design. Vaccine distribution and relations between the Commonwealth, states and territories became notably more fractious, and blame games emerged, as Delta spread in NSW, and to other states and territories, prominently Victoria and the ACT. The federal government could have hedged by ordering a greater variety of vaccines or could have done more to salvage the situation with an AstraZeneca-centred rollout based upon effective communication and incentives from governments. This brief consideration of second-order causes demonstrates the difficulties in ascribing causality, facilitating learning and demanding accountability for a crisis response.

What the governments of Australia might learn from the vaccine rollout is that authoritative policy tools like lockdowns, restrictions and enforcements may work as temporary means to limit the spread of disease. But delivering a positive pandemic measure, like a vaccine rollout, is unlikely to be achievable via authoritative regulation and coercion in a liberal-democratic context and instead requires greater engagement with crisis communication and whole-of-government organisational delivery. This finding might be useful in future debates about the design of Australian crisis responses.

Conclusion

This chapter has highlighted several factors that need to be considered in crisis evaluation and applied them to Australia’s COVID-19 crisis response. It has argued that crisis evaluation is a difficult and inherently political activity, characterised by objective facts and subjective perceptions. It has applied these ideas via the crisis management cycle of prevention, preparation, response, and recovery and learning, and has demonstrated the role of actors, institutions and policy design, and tools in crisis management across these stages.

Australia was successful in planning for, preparing for, and managing, COVID-19 during 2020 and the first half of 2021, if the metric of success was achieving ‘aggressive suppression’ and comparatively low case numbers and deaths. Australia has been less successful in managing the vaccine rollout in the recovery stage of the COVID-19 crisis, if measured against the ‘aggressive suppression’ strategy and the metric of low case numbers and deaths, plus the aim of rapid deployment of vaccines. However, Australia did rapidly increase the vaccine rollout in response to the Delta outbreak from mid-2021 and case numbers and deaths remained low in comparison to other countries. This picture of conflicting evidence will complicate the calls to hold leaders and institutions to account and will likely blunt attempts to reform policies and processes to improve crisis responses in future. Students of crisis responses and evaluations should be aware of these dynamics when performing their own evaluations of the Australian COVID-19 response or crises more generally.

References

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group on COVID-19, COVID-19 National Incident Room Surveillance Team, and Indigenous and Remote COVID-19 Policy and Implementation Branch (2021). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander epidemiology report on COVID-19, 28 February 2021. Communicable Diseases Intelligence 45(May). https://doi.org/10.33321/cdi.2021.45.27

Bell, Stephen, and Andrew Hindmoor (2009). Rethinking governance: the centrality of the state in modern society. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511814617

Boin, Arjen, Allan McConnell and Paul ’t Hart, eds 2008. Governing after crisis: the politics of investigation, accountability and learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511756122

Bromfield, Nicholas, and Allan McConnell (2021). Two routes to precarious success: Australia, New Zealand, COVID-19 and the politics of crisis governance. International Review of Administrative Sciences 87(3): 518–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852320972465

Bromfield, Nicholas, Alexander Page and Kurt Sengul (2021). Rhetoric, culture, and climate wars: a discursive analysis of Australian political leaders’ responses to the Black Summer bushfire crisis. In Ofer Feldman, ed. When politicians talk, 149–67. Singapore: Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-3579-3_9

COVID-19 National Incident Room Surveillance Team (2021). COVID-19 Australia: epidemiology report 36: reporting period ending 28 February 2021. Communicable Diseases Intelligence 45(March). https://doi.org/10.33321/cdi.2021.45.14

Crooks, Kristy, Dawn Casey and James S. Ward (2020). First Nations people leading the way in COVID-19 pandemic planning, response and management. The Medical Journal of Australia Preprint (April): 1. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50704

Department of Health, Australian Government Department of Health (2019). Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (AHMPPI). Australian Government Department of Health. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-ahmppi.htm

Drennan, Lynn T., Allan McConnell and Alastair Stark (2015). Risk and crisis management in the public sector, 2nd edn. Routledge Masters in Public Management. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315816456

Eriksson, Kerstin, and Allan McConnell (2011). Contingency planning for crisis management: recipe for success or political fantasy? Policy and Society 30(2): 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2011.03.004

Goldfinch, Shaun, Ross Taplin and Robin Gauld (2021). Trust in government increased during the Covid‐19 pandemic in Australia and New Zealand. Australian Journal of Public Administration 80(1): 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12459

Hood, Christopher (1986). The tools of government. Chatham: Chatham House.

McConnell, Allan (2020). Evaluating success and failure in crisis management. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1633

Patrick and Secretary, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (Freedom of Information) (2021). Administrative Appeals Tribunal of Australia.

Pollitt, Christopher, and Geert Bouckaert (2017). Public management reform: a comparative analysis – into the age of austerity, 4th edn. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ramia, Gaby, and Lisa Perrone (2021). Crisis management, policy reform, and institutions: the social policy response to COVID-19 in Australia. Social Policy and Society (October): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746421000427

Smith, Rodney, Ariadne Vromen and Ian Cook (2006). Keywords in Australian politics. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139168519

The Global Health Security Index (2019). GHS Index. https://www.ghsindex.org/

Van Hecke, Steven, Harald Fuhr, and Wouter Wolfs (2021). The politics of crisis management by regional and international organizations in fighting against a global pandemic: the member states at a crossroads. International Review of Administrative Sciences 87(3): 672–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852320984516

Victoria Ombudsman (2020). Investigation into the detention and treatment of public housing residents arising from a COVIID-19 ‘hard lockdown’ in July 2020. https://www.ombudsman.vic.gov.au/our-impact/investigation-reports/investigation-into-the-detention-and-treatment-of-public-housing-residents-arising-from-a-covid-19-hard-lockdown-in-july-2020/

Weible, Christopher M., and Paul A. Sabatier (2018). Theories of the policy process. New York: Routledge.

Welch, Dylan, and Alexandra Blucher (2020). Australia ran its last national pandemic drill the year the iPhone launched. did that harm our coronavirus response? ABC News, 19 April. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-20/coronavirus-australia-ran-its-last-pandemic-exercise-in-2008/12157916

Wilkinson, Iain (2010). Risk, vulnerability and everyday life. The New Sociology. London; New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203030585

About the author

Nicholas Bromfield is a lecturer in public policy with the Department of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney, Australia. His recent research projects have focused on Australia and New Zealand and the COVID-19 crisis, with interests in crisis administration, policy evidence, and civil society and third sector participation. He also researches issues of Australian identity and their effect on policy and rhetoric.

1 Drennan, McConnell, and Stark 2015, 2.

2 Weible and Sabatier 2018.

3 Drennan, McConnell, and Stark 2015, 30–32.

4 McConnell 2020.

5 Drennan, McConnell and Stark 2015, 31.

6 Bromfield and McConnell 2021, 520.

7 Smith, Vromen, and Cook 2006, 67.

8 Bromfield and McConnell 2021.

9 Bell and Hindmoor 2009, 1–2.

10 Pollitt and Bouckaert 2017.

11 Wilkinson 2010, 8–9.

12 Drennan, McConnell, and Stark 2015, 103–108.

13 Department of Health 2019, 3.

14 Department of Health 2019.

15 Van Hecke, Fuhr and Wolfs 2021.

16 Bromfield and McConnell 2021, 524.

17 Drennan, McConnell and Stark 2015; Eriksson and McConnell 2011.

18 Bromfield and McConnell 2021.

19 Kamradt-Scott 2014.

20 Department of Health 2019, 35.

21 Welch and Blucher 2020.

22 The Global Health Security Index 2019.

23 Drennan, McConnell and Stark 2015, 163.

24 Bromfield, Page and Sengul 2021.

25 Bromfield and McConnell 2021, 524.

26 Bromfield and McConnell 2021.

27 Patrick and Secretary, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (Freedom of Information) 2021.

28 Bromfield and McConnell 2021, 524.

29 Victoria Ombudsman 2020.

30 Crooks, Casey, and Ward 2020.

31 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group on COVID-19, COVID-19 National Incident Room Surveillance Team, and Indigenous and Remote COVID-19 Policy and Implementation Branch 2021.

32 Ramia and Perrone 2021.

33 COVID-19 National Incident Room Surveillance Team 2021.

34 Goldfinch, Taplin and Gauld 2021.

35 Bromfield and McConnell 2021, 527.

36 Bromfield and McConnell 2021.

37 McConnell 2020.

38 Boin, McConnell and Hart 2008, 309–312.

39 Boin, McConnell and Hart 2008, 312.

40 See Hood 1986 for the NATO typology of policy tools.