2

“I’ll show you that manyardi”:

Memory and lived experience in the performance of public ceremony in Western Arnhem Land

“I’ll show you that manyardi”

Download chapter 2 (PDF 4.5Mb)

Introduction

This chapter examines the role of archival recordings as an aid to revive and maintain song and dance practices and connections to ancestry and Country associated with the living performance tradition manyardi in the region of Western Arnhem Land, Australia. Specifically, it addresses the questions: How do performance traditions such as manyardi from Western Arnhem Land materialise ancestral connections in the present? And how do archival recordings of songs inform and sustain the practice of manyardi and composition of new songs?

In 2012, the co-authors of this chapter, musicologist Reuben Brown and songman Solomon Nangamu, travelled to Warruwi, South Goulburn Island, to make a trip with a group of dancers, singers and didjeridu players (see Figure 2.2). The trip arose from discussions Brown and Nangamu held while working together with Bininj at Gunbalanya (south of Warruwi on the mainland in Arnhem Land) and listening to a collection of archival recordings of manyardi, including Nangamu’s Mirrijpu (seagull) songset.1 As Nangamu puts it, “that song I sing, it’s got meaning for all that sacred site around the island – those two islands, south and north”.2 “I follow all that song from my, like my own sacred … thing – sacred site, that’s where I sing. I sing about the sea, about mother nature. The sacred site, the crow that did cut that two islands – split it in half.”3 Nangamu suggested he accompany Brown to his ancestral Country of Goulburn Island, not only to make a recording of manyardi with countrymen there for future generations, but also to show Brown his songs, by going to the sacred site from where the songs emerged and where ancestral spirits reside.

Figure 2.1 Warruwi, South Goulburn Island. Photo by Reuben Brown.

The chapter draws together ideas about the performative power of manyardi. Firstly, through Nangamu’s reflections about how the old people composed songs in order to capture the essence of things that sustain them, such as cockle, oyster and fish. Secondly, through the idea in anthropological and musicological literature that elements of the Dreaming can be conjured up in the here and now. In Western Arnhem Land, legacy song recordings are often used as an aid to revive songs for apprentice songmen, where an established arawirr (didjeridu) player and songman with expert knowledge are present to help guide their performance.4 Brown compares the melodic sequences of the Marrwakara (M: goanna)5 and Mirrijpu (M: seagull) songsets performed by the group in 2012 with legacy recordings made by Ronald Berndt of the same songs performed back in the 1960s by male relatives of the singers, analysing how manyardi is connected to the memory of performance events and particular singers, rather than learned from “authoritative” archival recordings. Nangamu demonstrates knowledge of how manyardi is passed on and sustained, with insights about kinship and song inheritance, song conception, vocal style, song text and the ancestral genesis of his own manyardi. Insights by participants assembled for the performance in 2012 at Amartjitpalk also reveal how performing manyardi at Goulburn Island is undertaken to conjure up connections between people, historical events, and ancestors in the Country, making Arrarrkpi and the Country feel alive and happy.

Figure 2.2 The group at Amartjitpalk performing manyardi, Goulburn Island, 2012. From left to right: Brendan Marrgam, Sam Wees, Russell Agalara, Maurice Gawayaku and his son, Micky Yalbarr (didjeridu), Solomon Nangamu, Harold Warrabin. Photo by Reuben Brown.

Memories of connection: The wurakak (M: crow) story

Arrarrkpi (M: Indigenous people) tell a story that has been handed down over many generations of a time before Arrarrkpi (M: humans), when the north and south islands were joined as one. Nangamu led a retelling of this story at Amartjitpalk, by way of explaining how his inherited songset named Mirrijpu (M: seagull)6 came into existence. The mirrijpu was once Arrarrkpi, as were all the other birds that can be found on Goulburn Island. Korroko (K: long ago), during the period of the ancestors, they were spending their time on Weyirra (North Goulburn Island) fishing, when they had unwelcome company in the form of a waak waak/wurakak (K/M: black crow). Here is a version of the story Nangamu recorded prior to our trip:

Yoh [yes] that mayhmayh, a long time [ago], that seagull he was like human too, like, long time. They used to see crow used to come, just asking around. The black crow, he was a Bininj (K: human) too. They used to tell him “no, you go, don’t come here!” He was scratching around for a scrape of tucker. But they didn’t even give it to him. They said, “nah, we’ll give you little rubbish” – bone or whatever. He said “alright”, and that island it was only one big island, South Goulburn. So that crow went and got his axe, that big stone axe. Long time. And [he] split that island in two – North and South, but he’s in the middle. That’s my sacred site. Under the sea – that’s the big stone axe inside. In the middle – South Goulburn and North Goulburn, but it’s in the middle. You see that reef there – that’s him there … he talks too – at full tide he go “waak!” – you can listen. That one’s from Mirrijpu now [that story]. They were too greedy for tucker, they never give him [any], and he told them all, “I’ll teach you a lesson, so you’ll be sitting separate, island to island.” So, he made all of my [Manangkardi-speaking] tribe, all that Mirrijpu.7

Nangamu and others in the group including Russell Agalara and Harold Warrabin discussed how Mawng people’s djang (K: sacred sites) are located not only on the islands, but also underneath the sea, where the trunk of a large paperbark tree that once stood on the united Goulburn Island fell, after the crow chopped it down. When the water is calm, a whirlpool forms in between the islands, indicating the presence of the tree still growing at the bottom of the ocean floor:

RA: They seen that satellite, that yemed [K: thing], leaf growing in the middle of that water, it’s growing.

SN: Underneath.

RA: Yeah, that tree is still there.

SN: Maybe it’s going to connect those two islands?

HW: Coming up, yoh growing.

RA: They saw it with a computer, them scientist mob, they find a tree growing right in the middle.8

Linda Barwick observes how the practices of song, dance and visual art that make up Indigenous Australian performance traditions represent “interdependent parts of a complex whole”, which are linked together through one’s ancestral Country.9 Understanding of this interconnectedness stems from the knowledge that individual songs, dances and designs drawn in the sand, painted on rock and on the body, were handed down first by creation spirits that shaped the Country, then carried on by ancestors over thousands of generations. For Arrarrkpi and Indigenous people elsewhere in Australia, the act of performing songs and dances that have been handed down expresses links between people and their ancestral Country. Through our reflection and analysis of the event at Amartjitpalk, we suggest that when Arrarrkpi perform manyardi at specific sites of significance on Goulburn Island, they re-activate their memories and regenerate their spiritual connections to ancestral Country.

The “interdependent parts” that made up this performance include: the memory of those people who passed on the songs to the current-day singers and their traditional Country and languages; the ancestral stories that link the Country and the songs together, and the feelings and associations that were conjured up during the performance. We analyse how two musically distinct songsets – Marrwakara/Mularrik (M: goanna/green frog) and Mirrijpu (M: seagull) – linked through Manangkardi traditional Country and language, were paired together in performance, and how this pairing reflects an awareness of “the complex whole”.

Regenerating ancestral connections by performing manyardi

Any living thing they was eating, like kobah-kohbanj [K: old people], like korroko [K: a long time ago] – oyster, cockle, anything that lived in that sea – seafood, people who lived on this island, long time. They said, “ah, we can’t just go eat food? How ’bout we make song about this tucker? Bush tucker.” So, they made all this song now, that we’re singing now. They talk about land, they talk about the seaside, any living creature that God made, and kobah-kohbanj they got that thing, and they passed it to me, and I try and pass it to my new generation …10 (Nangamu)

Nangamu’s explanation as to how it was that his manyardi came about – offered during a discussion over lunch while the group took a break from singing and dancing at Amartjitpalk – suggests that kobah-kohbanj were keeping alive the very things that they treasured and that sustained them by putting them into a song. As Nangamu suggests, “they got that thing” – that inspiration or life-force that has its origins in the Dreaming – and fashioned it in musical form, and then they passed it on so that it could continue to be nurtured. Nangamu alludes to the richness of the manyardi tradition and the many named songsets that have been performed by various songmen over the generations, all of which pay homage to various “living creatures” of Western Arnhem Land. His reference to God as creator reveals the way in which the Methodists’ teachings of Christianity have been incorporated into Arrarrkpi people’s spiritual beliefs and understandings about the Dreaming.

Nangamu’s insights also resonate with the observations on the performative nature of the Dreaming by scholars such as Ronald Berndt, Fred Myers and William Stanner. Stanner argued that stories from the Dreaming do not provide a literal meaning, nor a definition or truth, but rather a “poetic key to Reality” or a “key of Truth”:11

The active philosophy of Aboriginal life transforms this “key”, which is expressed in the idiom of poetry, drama and symbolism, into a principle that the Dreaming determines not only what life is but also what it can be. Life, so to speak, is a one-possibility thing, and what this is, is the “meaning” of the Dreaming.12

The Dreaming which shaped the Country that people inhabit, and to which people are linked through their ancestors who had lived on that Country since time immemorial, manifests itself in the here and now in various forms. Living phenomena such as birds (a crow or seagull) and the sea (the appearance of a whirlpool) are interpreted as manifestations of the ongoing presence and power of the Dreaming. Songs, dances and ceremony passed on from ancestral spirits that still dwell in the Country of Western Arnhem Land such as mimih (K: stone Country spirits) or warra ngurrijakurr (M: mangrove-dwelling spirits or “little people”) – are thought to “follow up the Dreaming”, and re-enact its presence.13 Fred Myers argues that it is precisely through the activities performed in the present that gives meaning to the Dreaming, and enables Aboriginal people to “hold” their particular ancestral Country:

The meaning of these places, their value, must be understood as constructed – not by the application of some pure cultural model to blank nature … but in activities that constitute relationships within a system of social life that structures difference and similarity among persons.14

Ronald Berndt argues that artists (i.e. songmen such as Nangamu) play a vital role in this interpretation of the Dreaming, as re-activators of the spirits, “reviving the spiritual” through the paintings, songs, dance, carvings etc. that they create.15 Berndt suggests that through metaphoric and symbolic meaning, Western Arnhem Land songs “guide us toward an intellectual appreciation of the world about us”.16 Discussing Marrwakara/Mularrik songs which are the focus of this chapter, he contends that by anthropomorphising natural species in song – investing them with “human characteristics” – Arrarrkpi perceive these animals not just as food, but understand their place within a broader ecology.17

Archival recordings of manyardi

The performance and recording of Marrwakara/Mularrik and Mirrijpu songs by the group at Amartjitpalk with Brown in 2012 followed a historical precedent. For many years, Arrarrkpi songmen have hosted and performed manyardi for other musicologists, linguists and anthropologists from outside their community. Many of the songmen recorded by Colin Simpson with the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land at Oenpelli/Gunbalanya in 1948 were Arrarrkpi from Goulburn Island.18 In 1961 and 1964, anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt recorded Harold Warrabin’s father – Joseph Gamulgiri (see Table 2.1) – performing songs from the Marrwakara/Mularrik songset with songman John Guwadbu19 “No. 2” at Warruwi. Gamulgiri, who was also the brother of Nangamu’s father,20 was one of many Arrarrkpi who assisted Berndt with his research, from the time of Berndt’s first visit to the island in 1947.21 To complete this intergenerational picture, Phillip Magulnir22 – the brother of John Guwadbu and father of current manyardi didjeridu player Alfred Gawaraidji – also played didjeridu for Guwadbu, Gamulgiri and others during this time.23 As Nangamu explained:

old man John, and his brother that Alfred [Gawaraidji], his father – old Philip Magulnir – he was didj man, he was number one, he played different kind of manyardi like for them, that old fella. That’s why you see Alfred he go play didjeridu anywhere!24

Another songman – Nanguluminy25 – was also recorded singing Marrwakara by Sandra Le Brun Holmes in 1964.

Figure 2.3 Photo of Joseph Gamulgiri (left) and his son Harold Warrabin (right). Photo of Gamulgiri held by Martpalk Arts and Crafts (original photographer and date unknown); photo of Harold Warrabin by Martin Thomas, 2012.

In his 1987 article, Ronald Berndt transcribes the Marrwakara/Mularrik songs he recorded with Gamulgiri and Guwadbu, and sets out a narrative that explains the songs, based on interviews with the singers elicited after the recording.26 In 2006–7, Linda Barwick and Isabel O’Keeffe made a series of recordings of Warrabin and Nangamu singing two Marrwakara/Mularrik songs and Mirrijpusongs at Warruwi, including didjeridu accompaniment by Micky Yalbarr, Alfred Gawaraidji and Nangamu (see Table 2.1).27 Based on discussions with contemporary consultants, Linda Barwick, Isabel O’Keeffe and Ruth Singer examine the “dilemmas of interpretation” in Berndt’s original transcriptions (most of which were remarkably accurate) and his narrative for the Marrwakara/Mularrik songset, and transliterate Berndt’s transcriptions into Mawng orthography.28 In July 2012, some months prior to the recording at Amartjitpalk, Nangamu and Gawaraidji also made a recording with Brown of Warrabin singing at Gunbalanya (2012d in Table 2.1). The presence of Nangamu, Gawaraidji and Brown as recordist (a student of previous recordist Barwick) once again provided the singers with an opportunity to revisit the songs and regenerate their memories of their fathers who taught them the songs when they were growing up.

| Year | Songset(s) | Songs | Recordist | Performers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1961 |

Marrwakara/Mularrik |

12 |

Berndt |

John Guwadbu (“No. 2”) |

|

1965 |

Marrwakara |

1 |

Le Brun- Holmes |

Nungolomin [Nanguluminy], |

|

2006a |

Mirrijpu |

4 |

O’Keeffe |

Solomon Ganawa, |

|

2006d |

Marrwakara/Mularrik |

2,7 |

O’Keeffe |

Harold Warrabin |

|

2007 |

Mirrijpu |

8 |

Barwick |

Solomon Nangamu |

|

2011a |

Mirrijpu |

4 |

Brown |

Solomon Nangamu, |

|

2012a |

Mirrijpu |

7 |

Brown |

Solomon Nangamu, Russell Agalara |

|

2012d |

Marrwakara/Mularrik |

2 |

Brown |

Solomon Nangamu, Russell Agalara |

Table 2.1 Summary of recordings of Marrwakara/Mularrik (M: goanna/green frog) and Mirrijpu (M: seagull) at Goulburn Island and Gunbalanya.

Manyardi and memory

The performance of manyardi relies on a select group of expert musicians who are familiar with one another’s repertories. Performing engages the collective memory, and part of the joy of performing is allowing the songs to evoke memories of people and Country, including memories of previous occasions when the musicians came together to perform the songs. On both occasions at Gunbalanya and Amartjitpalk in 2012, Nangamu practised the songs with Warrabin first to help him remember the songs. As the songmen were remembering how the tune went, Nangamu announced that he would “change” his voice, to sound like the old men who used to sing the song (Guwadbu No. 2 and Gamulgiri).29 He sang with a soft legato-like quality, imitating Guwadbu’s voice on Berndt’s recording, which features on the cassette Songs of Aboriginal Australia that accompanies an edited volume of the same name.30 Warrabin’s voice, by contrast, has a rougher, more strained timbre, perhaps following the vocal style of his father (“second singer” Gamulgiri).31

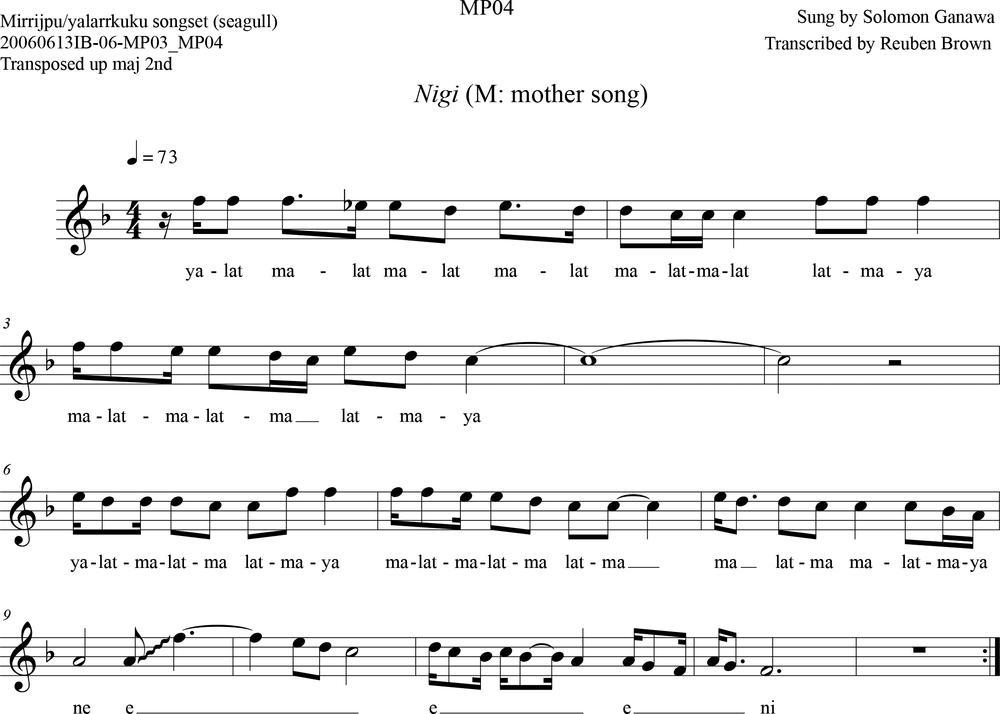

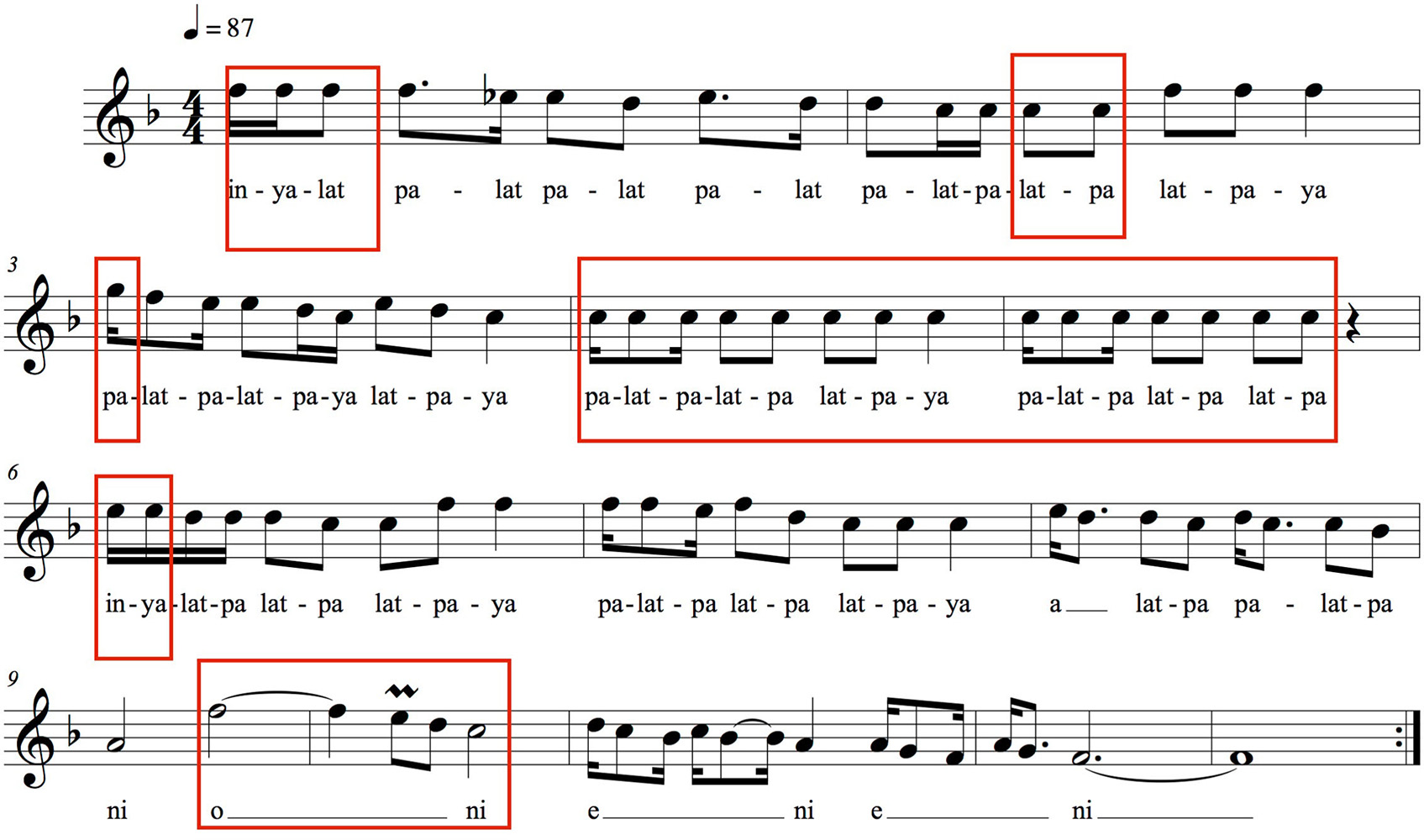

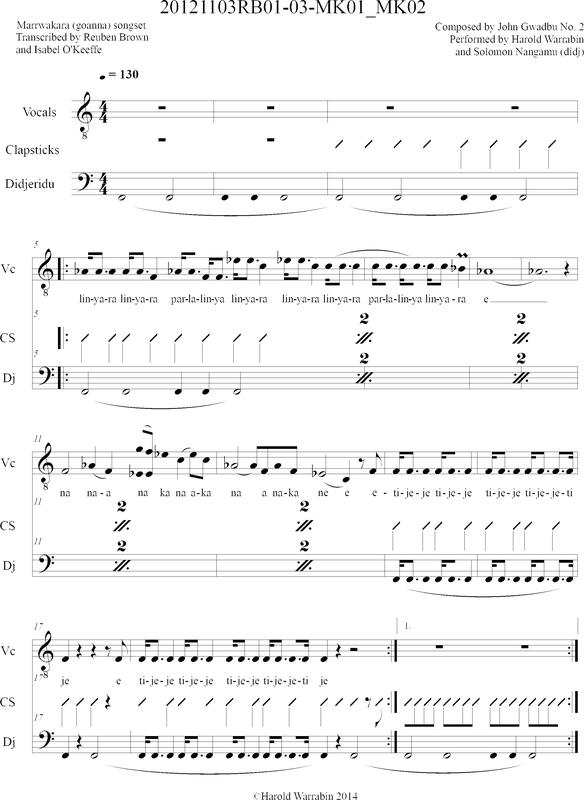

In preparation for the performance at Amartjitpalk, Nangamu and Warrabin requested that Brown burn them a copy of Berndt’s recordings of Guwadbu and Gamulgiri singing Marrwakara/Mularrik, so that they could listen to the old people, and refresh their memory of the songs.32 Interestingly, these recordings are by no means identical to contemporary versions performed by Warrabin: the former includes a number of Marrwakara/Mularrik songs that Warrabin no longer sings.33 Warrabin’s current repertory consists of two songs: MK01 – which can be performed on its own – and MK02, which is sometimes joined on (i.e. the didjeridu accompaniment continues uninterrupted) to song MK01 as one song item. While MK01 remains relatively true to the Berndt recording, there are several differences in contemporary versions of MK02, including subtle variations in the melody and the way that the song text (Figure 2.4) is pieced together. The three different recorded versions of MK02 are transcribed in Figure 2.5, Figure 2.6 and Figure 2.7 (listen to SAA-B-06-MK02.mp3, 20061013IB02-05-MK02.mp3 and RB2-20121103-RB_01_03_MK01_MK02.wav).34

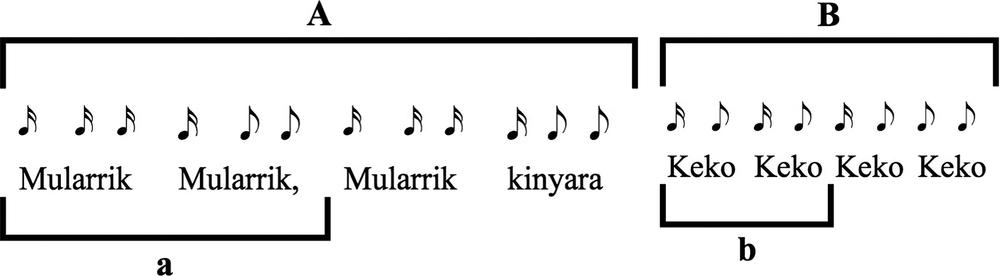

Figure 2.4 Song text of MK02.

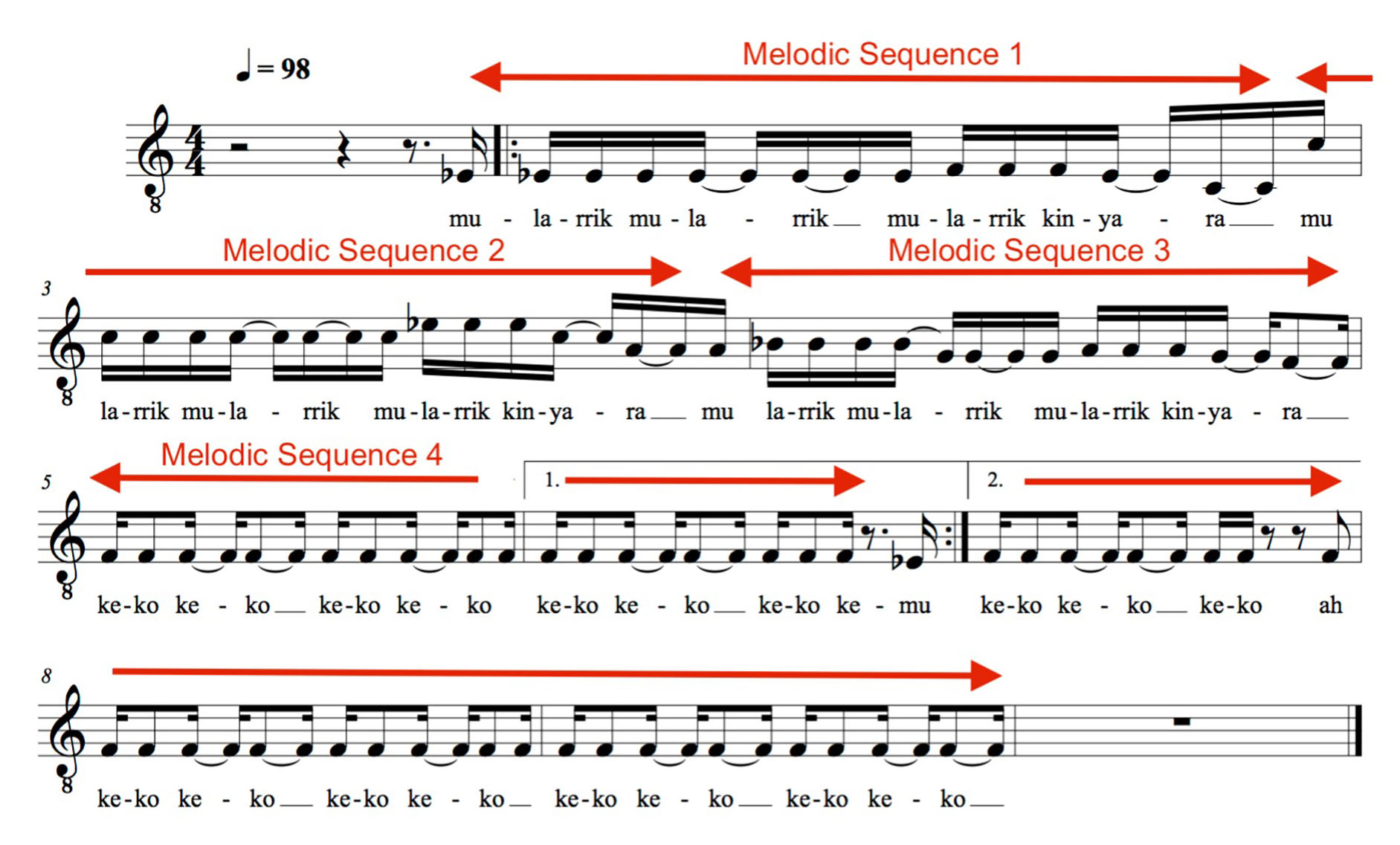

Figure 2.5 Music transcription of vocal part of MK02, performed by John Guwadbu “No. 2” and Joseph Gamulgiri in 1964 SAA-B-06-MK02.mp3. (Recorded by Ronald Berndt in 1964. Transcribed by Reuben Brown, based on rhythmic transcription by Isabel O’Keeffe.)

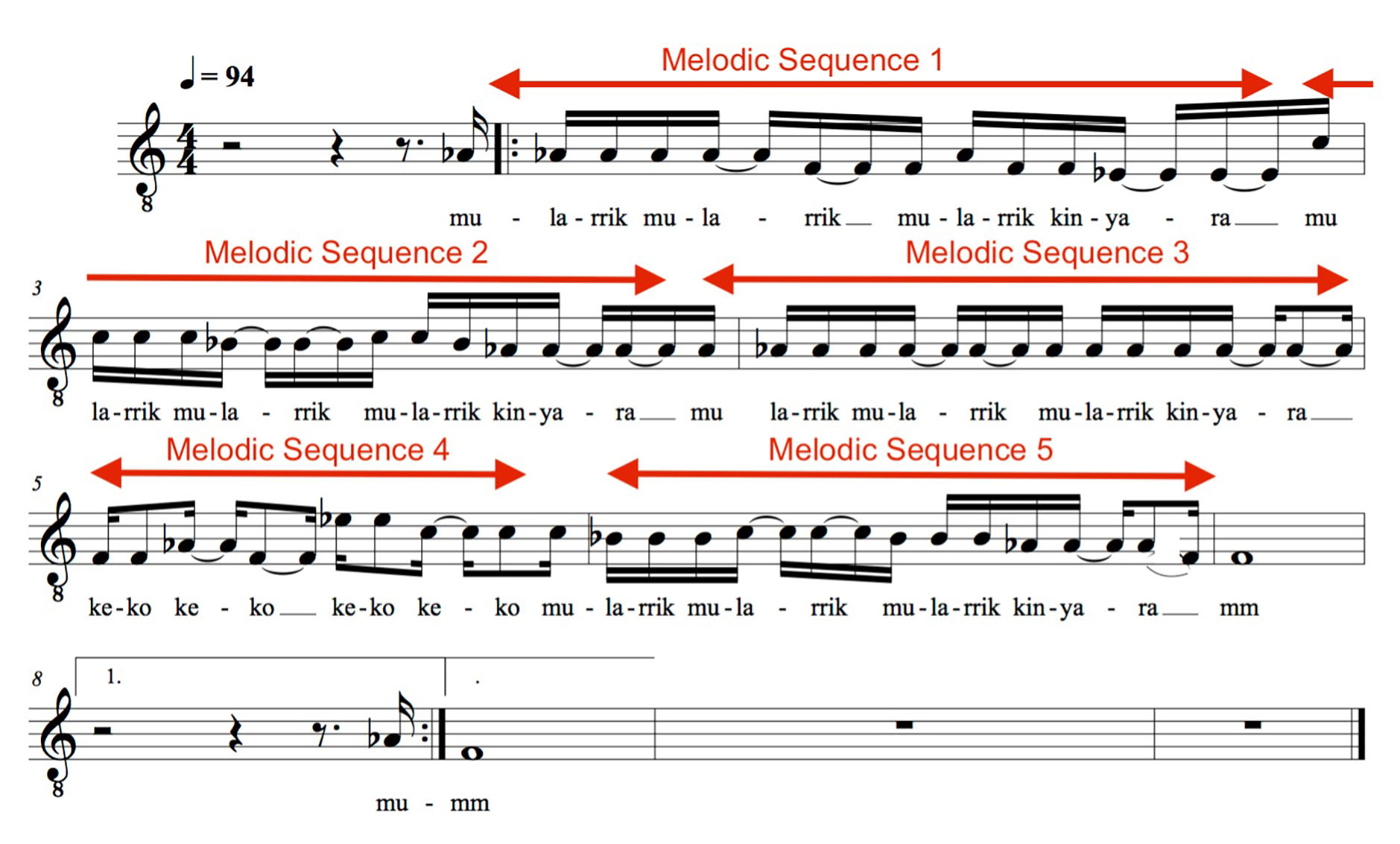

Figure 2.6 Music transcription of vocal part of MK02, performed by Harold Warrabin and Solomon Nangamu in 2006, transposed down a major 2nd from G to F (20061013IB02-05-MK02.mp3). (Recorded by Isabel O’Keeffe in 2006 20061013IB02-05-MK02 in Linda Barwick, Allan Marett, Nicholas Evans, Murray Garde, Isabel O’Keeffe, and Bruce Birch (2012). Western Arnhem Land Song Project data collection. The University of Sydney. http://elar.soas.ac.uk/deposit/arnhemland-135103).

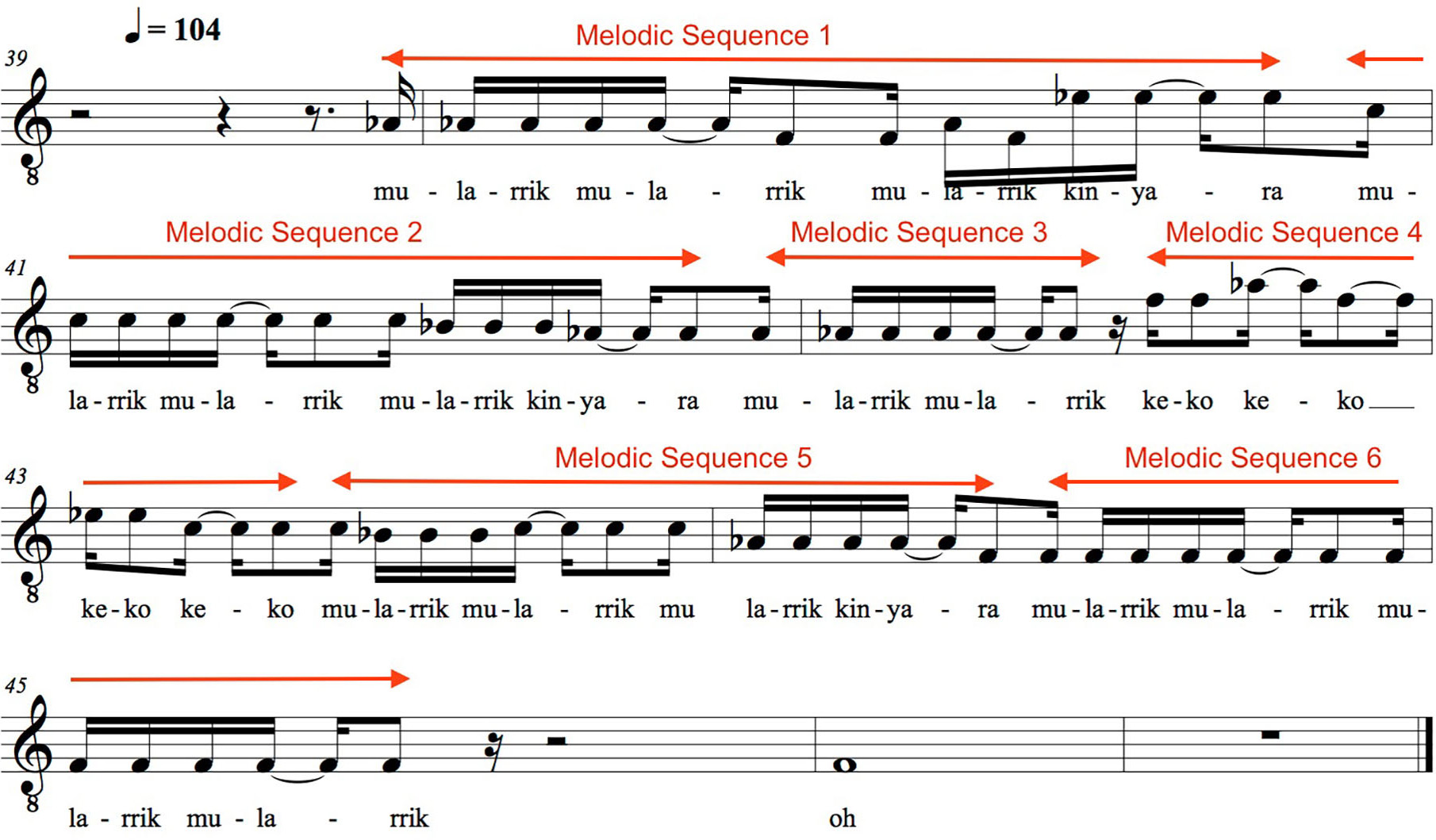

Figure 2.7 Music transcription of vocal part of MK02, performed by Warrabin and Nangamu in 2012 (RB2-20121103-RB_01_03_MK01_MK02.wav). (Recorded by Reuben Brown in 2012, https://bit.ly/3AxjrYl.)

Stable and adapted aspects of manyardi

A comparison of recordings of MK02 performed by Guwadbu and Gamulgiri in 1964 with versions performed by Warrabin and Nangamu in 2006 and in 2012 reveals the extent to which aspects of a song are adapted while others remain stable over time, as it is passed on to different songmen (see Table 2.2). While the basic song text and melodic contour remain stable, aspects such as the text configuration, tempo and melody vary, and have been adapted or reinterpreted over time. The main difference between Guwadbu’s and Warrabin’s versions relates to the melodic contour and melodic mode. Whereas Melodic Sequence 1 (MS1) in the 1964 version begins on a flattened 7th degree of the scale, the 2006 and 2012 versions start on a flattened 3rd degree of the scale, followed by an ascending Dorian sequence. The song text is also realised differently in all three versions, in particular Text Phrase B (the vocables: “keko keko, keko keko” – which imitate the sound of the mularrik [M: frog]). In the 1964 version Gamulgiri repeats Text Phrase A three times, followed by two repeats of the vocables (BB) and three repeats in the final version (BBB), sung on the 1st scale degree. In the 2006 version (AAAbA) the vocables are sung to a rising and falling melodic contour – MS4 (based on MS1 in the 1964 version) – and joined with Text Phrase A – MS5 (based on MS3 in the 1964 version). The 2012 version follows the 2006 version, but adds another section of song text A (truncated) at the end (AAabAa). Finally, whereas the 1964 version remains on the 1st degree of the scale during the vocables (B) section, the contemporary versions sing the vocables to a different melodic sequence (MS4) 1-3b-1-7-5, which also features in song MK01 (see Figure 2.11).

| 1964 | SAA-B-06-MK02 |

MS1 7b-1-7b-5 A |

MS2 5-7b-5-3 A |

MS3 4-2-3-2-1. A |

MS4 (1.) 1_____. BB |

MS4 (2.) 1_____. BBB |

|

| 2006 | 20061013IB02-05 -MK02 |

MS1 3b-1-3b-1-7b A |

MS2 5-4-5-4-3b A |

MS3 3b______ A |

MS4 1-3b-1-7-5 b |

MS5 4-5-4-3b-1 A |

|

| 2012 | RB2-20121103RB _01_03_MK01_MK02 |

MS1 3b-1-3b-1-7b A |

MS2 5-4-3b A |

MS3 3b______ a |

MS4 1-3b-1-7-5 b |

MS5 5-4-3b-1 A |

MS6 1______. a |

Table 2.2 Comparison of the three recordings of MK02. Table shows Melodic Sequence (MS) number, scale degrees of the melodic sequence and corresponding Text Phrase (A, a, B, b, etc.).

There are a number of possibilities that may explain the above variations: Warrabin’s 2006 and 2012 versions of MK02 may well be based on his understanding of song MK01, which shares the same melodic sequence. It is also possible that the contemporary version of MK02 is based on a version/versions of the song sung by Gamulgiri (rather than Guwadbu) that were not recorded by Berndt. In any event, the variations demonstrate that kun-borrk/manyardi songmen take a creative approach to song identity. In spite of the availability of older recordings in this instance, and their usefulness as an aid to manyardi performance – the song is ultimately held in the memory of the current songman, who inherits it and makes it his own through constant reinterpretation in performance.

Vocal quality and realisation of song text

Returning to Nangamu’s imitation of Guwadbu’s voice in 2012, it appears this was not a one-off, but rather a convention observed of kun-borrk/manyardi and some wangga repertories, to imitate or retain the vocal timbre and style of the songman who composed the songs in the songset.35 This fits with the degree of agency that singers attribute to past songmen, who continue to give them new compositions in their dreams. The imitation of voices ensures that even once the main songman dies, those who were familiar with his voice would still hear the spirit of the songman singing through the current singer/composer.36 At the same time, the more frequently that current songmen sing songs from their repertory, and the more widely they perform their songs, the more they are likely to establish themselves as the “number one” singer of that songset and newly conceived songs, which may deviate slightly in vocal style and timbre or in the realisation of the melody and tempo, compared with previous versions performed by former songmen.

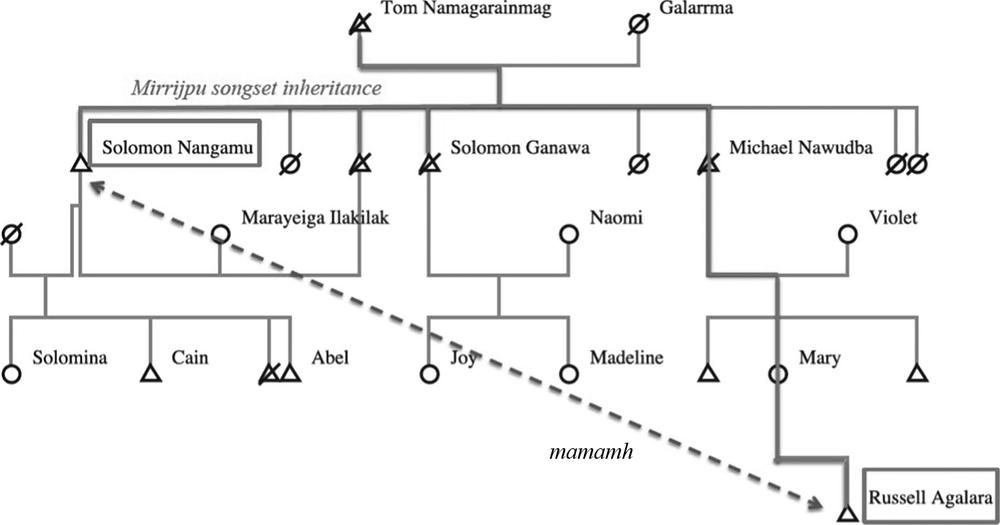

This is the case with the Mirrijpu songset, which was led by Nangamu’s brother, Solomon Ganawa, until 2006 when he passed away, not long after Isabel O’Keeffe and Linda Barwick recorded Ganawa singing at Warruwi. After a period of one year in which the songs were not performed, Nangamu took over as the “number one” songman and has been a prolific performer of the songset, recording Mirrijpu on nine separate occasions, each time performing a variety of songs, including new songs he has since received in his dreams. As a result, Nangamu’s recordings of Mirrijpu and his style of singing are now very well known in Western Arnhem Land, particularly among Bininj/Arrarrkpi living at Gunbalanya and Goulburn Island. Comparing recordings made by Nangamu in 2007 – the first time the songset was performed after the death of Ganawa – with recordings made by Ganawa in 2006, one hears minimal variation in tempo, and a similar realisation of the melody. For recordings of Nangamu made some years later in 2011 and 2012, however, notable differences can be observed in tempi (Nangamu’s preferred tempo is slightly faster),37 melody (Nangamu’s realisation of the melody is more embellished compared with Ganawa’s) and vocal style (while Ganawa slides into the notes, Nangamu pitches the notes more precisely). A comparison of the Mirrijpu nigi “mother song” performed by Ganawa in 2006 (Figure 2.8) with a version performed by Nangamu in 2011 (Figure 2.9) neatly illustrates these differences. Nangamu’s tempo (87 bpm) is faster than Ganawa’s (73 bpm) and there are added notes in Nangamu’s melody (highlighted in box outlines) compared with Ganawa’s. In measure 9, where Ganawa slides from A to F while singing the vocables, Nangamu instead pitches the note F precisely; his realisation of the song text and vocables is also slightly different (“latpa” rather than “latma”; “o” rather than “e”; extra syllable “inyalat” rather than “yalat”, etc.).

Figure 2.8 Music transcription of vocal melody of MP04 (nigi), performed by Solomon Ganawa in 2006, transposed up major 2nd from 20060613IB-06-MP03_MP04 in Linda Barwick, Allan Marett, Nicholas Evans, Murray Garde, Isabel O’Keeffe and Bruce Birch (2012) Western Arnhem Land Song Project data collection. The University of Sydney. http://elar.soas.ac.uk/deposit/arnhemland-135103. (Brown’s musical transcriptions here and elsewhere in the chapter were based on listening to the recordings.)

Figure 2.9 Music transcription of Solomon Nangamu’s version of MP04nigi (RB2-20110719-RB_04_06_MP19_MP04.wav, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/KXKQ-X317).

The conservatism of melodic contour from one generation to the next accords with observations in the literature about North-East Arnhem Land manikay. Peter Toner, analysing the correlation between melody and social structure and the way in which singers articulate connections to Country through their choice of melody in performance, observes that:

Yolngu singers use melody as a key means of constructing their identities as the outcome of the interaction of their social theory and social practice. Dhalwangu singers go into ritual musical performances with a diverse set of ideas about what it is to be Dhalwangu. These ideas, different (but probably overlapping) for every Dhalwangu person, are based on what an individual knows about cosmology, land tenure, genealogy – traditional grist for the anthropological mill – but also idiosyncratic personal and family histories, friendships, the events of everyday life and what they remember about previous ceremonies and musical performances.38

Many kun-borrk/manyardi repertories, such as Mirrijpu, Inyjalarrku and Karrbarda, have been passed down to several male relatives of the same generation. As discussed earlier, certain versions of a song remain associated with previous songmen even after these songmen pass away, particularly the versions that were conceived by those individuals. Figure 2.10 shows inheritance of the Mirrijpu songset across four generations, from Tom Namagarainmag to his sons Michael Nawudba, Solomon Ganawa and Solomon Nangamu, and from Nawudba to his daughter, Mary, to her son, Russell Agalara (thus, inheritance is not strictly patrilineal). Agalara is the “second singer” for the Mirrijpu songset, in the sense that he is still apprenticing Nangamu, but he has already commenced leading the ceremony in Nangamu’s absence. Agalara learned the songs from his mother’s father, Michael Nawudba (Nangamu’s older brother, now deceased), and recalls sitting with Nawudba as a toddler and listening to the songs. This means that although Agalara is younger than Nangamu, he is still familiar with the “old” songs from the repertory that Nawudba used to sing, and his interpretation of those songs is influenced by his memory of Nawudba’s singing style and performance. Agalara and Nangamu call each other mamamh, which is a reciprocal kinship term for one’s mother’s (classificatory) father or mother’s father’s sister and conversely, one’s daughter’s daughter or daughter’s son. (In the kinship system of Western Arnhem Land, one’s father’s brothers are all considered “father”, and one’s mother’s sisters considered “mother”.) Nangamu and Agalara therefore also refer to one another using the English terms “grandson” and “granddad”.

Figure 2.10 Solomon Nangamu and Russell Agalara’s inheritance of the Mirrijpu songset. Figure represents song inheritance with black line, while dotted line shows mamamh relationship between Nangamu and Agalara. Names used with permission.

Manyardi and Country

The juxtaposition of Mirrijpu and Marrwakara/Mularrik songs in the performance at Amartjitpalk brought up connections not only with people in living memory (i.e. Gamulgiri, Guwadbu) but also with Country and ancestors. After the group warmed up, Nangamu began blowing a slower-tempo rhythm on the didjeridu and Agalara led the singing of a Mirrijpu song with Warrabin and Yalbarr backing. They repeated the song three times, finding a meeting point with one another’s voices. When this song had finished, Nangamu asked us if we had heard that “sweet sound”, and the other musicians nodded in agreement. It was as though the sound that came out of their mouths, blended with the arawirr (M: didjeridu) and the nganangka (M: clapsticks), was not entirely of their making, but a part of the environment around them, which was also making the music and responding to their performance. Later on, while listening back over the recording, Nangamu commented that he felt “nice and good” to sing, as though a “whole orchestra” were backing him up.39 At another stage of the performance after the men had got up to dance, Yalbarr remarked that the waves had swelled, to which Nangamu responded: “kunak-apa hapi kangmin … (the land/Country is happy …)” and Marrgam added, “eh hapi kangmin (yes it’s happy) – on the right track!”40

After playing the didjeridu for the first Mirrijpu song, Micky Yalbarr pointed across the sea to North Goulburn Island, and told us that the song reminded him of a hunting area where he would go fishing and catch “trevally, skinny fish, any kind”.41 Nangamu then explained that both the Marrwakara and Mirrijpu song texts refer to this place, which belongs to the Country of Manangkardi-speaking people of the Majakurdu clan:

Any song [with] “Inyalatpa” … that’s one for us, like all the manyardi – “Linya” too … Same like Marrwakara [songset], “Linya”. And Mirrijpu [songset] too, we go same, “Linya” … That’s kunred (K: Country/home) – “Linya”.42

It’s in … Marrwakara, it’s in Mirrijpu – in Yalarrkuku – Milyarryarr and Manbam [songsets] – one. We talk about that one kunred (K: home).43

Nangamu explained that Linya is the “short name” for the place name “Parlalinya” – a Dreaming site on Weyirra associated with the lightning ancestral spirit called Namarrkon in Kunwinjku, who today assumes the form of a grasshopper. Place names such as these are significant because they are the same both in the spoken language (of Madjukurdu clan Manangkardi speakers who lived on Weyirra) and the spirit language (originally named by the spirit ancestors). As Nangamu explained to Brown: “we can record it, but the word [in the song] is like spiritual language, from the dead people to us then we pass it to a new generation and it goes on and on”.44

The singers also explained that the Marrwakara/Mularrik songs (MK01 and MK02) “go together” because the goanna Dreaming and the green frog Dreaming are connected by Mularrik Mularrik Creek on Goulburn Island, which runs through the town of Warruwi.45 The pair of songs is contrasting in tempo and rhythmic mode (listen to RB2-20121103-RB_01_03_MK01_MK02.wav, where MK02 begins at 01:10).46 The songs are also contrasting in the way they mix languages: MK01 is in Manangkardi spirit language and has the Manangkardi place name Parlalinya; MK02 is in Mawng and has the song text: “mularrik mularrik, mularrik, mularrik k-i[ny-a]ja-ka” [sung as kinyara], translated as “Frog, she keeps calling out”. (See Figure 2.11.)47

Figure 2.11 Music transcription of Marrwakara songs MK01 and MK02 “joined together”, performed by Harold Warrabin at Amartjitpalk, 2012 (RB2-20121103-RB_01_03_MK01_MK02.wav, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/G9SR-AX36). (Transcriptions of didjeridu rhythms are to be taken as indicative; the aim here is to show how the clapstick, didjeridu and vocal parts interact and how the music is organised, rather than provide a detailed musical transcription of the recording for performance.)

Conclusion

The performance, discussion and insights from manyardi songmen and dancers at Amartjitpalk illustrate that to perform kun-borrk/manyardi is not merely to sing songs, but also to make connections to recent, historical and ancestral events, significant places, previous songmen etc., and to sustain these connections by involving everyone in the performance. Experienced and expert songmen such as Solomon Nangamu play an important role in leading the performance of kun-borrk/manyardi, and yet the success of the performance relies on the equal participation of members of the group, rather than the efforts of any one individual.

Perhaps contrary to expectations, the existence of older recordings of both the Mirrijpu and Marrwakara songsets has not resulted in a homogeneity of vocal or musical style in the performance of these songsets, based around the qualities of one songman. Rather, current songmen look to old recordings to assist their memory of manyardi, and, in the case of Nangamu’s Mirrijpu songset, consciously make new and different versions of the songs that they record in order to leave another permanent record for the next generation. Singers nevertheless recognise the musical authorship of the songs that they have learned from their male relatives. Analysis of the same song item in a songset realised by two different singers reveals both innovation and stable elements such as conservatism of melodic contour, song text and rhythmic mode. The current generation of manyardi songmen pays tribute to previous songmen by juxtaposing recently dream-conceived songs with the songs they have inherited, following the principles the old people taught them relating to song order and tempi, and continuing to teach the didjeridu accompaniment and song-leading to younger performers.

Rather than relying purely on the recording then, manyardi is collectively remembered, re-created and passed on through performance by a group of expert songmen and countrymen. Country also plays an active role in the process of refreshing memories of the old songs and conceiving new ones. Nangamu sums up this relationship with an anecdote about receiving a new song upon returning from his ancestral Country of Goulburn Island to Gunbalanya:

Myself, I can listen to that clapstick. Somebody watch me, but they sing it for me. They give me that song [in a dream] and I sing that song. I got a couple of new songs now, when I was living there [in Goulburn Island]. And I got it in my dream, my ancestors they talked to me, and I listen, that they’re going to give me something – a present, like a gift. Then I have that song and I pass it to my son and my grandchildren, pass it on to them, and on and on.48

References

Barwick, Linda. “Song as an Indigenous Art”. In The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, eds Sylvia Kleinert and Margo Neale. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2000: 328–35.

Barwick, Linda. “Tempo Bands, Metre and Rhythmic Mode in Marri Ngarr ‘Church Lirrga’ Songs”. Australasian Music Research 7 (2002): 67–83.

Barwick, Linda. “Performance, aesthetics, experience: thoughts on Yawulyu Mungamunga songs”. In Aesthetics and Experience in Music Performance, eds Elizabeth MacKinlay, Denis Collins and Samantha Owens. Newcastle UK: Cambridge Scholars, 2005: 1–18.

Barwick, Linda, Bruce Birch and Nicholas Evans. “Iwaidja Jurtbirrk Songs: Bringing Language and Music Together”. Australian Aboriginal Studies no. 2 (2007): 6–34.

Barwick, Linda, Isabel O’Keeffe and Ruth Singer. “Dilemmas in Interpretation: Contemporary Perspectives on Berndt’s Goulburn Island Song Documentation”. In Little Paintings, Big Stories: Gossip Songs of Western Arnhem Land, ed John Stanton. Nedlands: University of Western Australia, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, 2013: 46–71.

Berndt, Ronald. Letter to Alf Ellison, 15 January 1948, Item 4.3.6. NTRS 38, Location 142/2/4, Northern Territory Archives.

Berndt, Ronald, ed. Australian Aboriginal Art. Sydney: Ure Smith, 1964.

Berndt, Ronald. “Other Creatures in Human Guise and Vice Versa: A Dilemma in Understanding”. In Songs of Aboriginal Australia, eds Margaret Clunies Ross, Tamsin Donaldson and Stephen Aubrey Wild. Sydney: University of Sydney, 1987: 169–91.

Berndt, Ronald. SAA-B-06-MK02 (1964), in Stephen Wild (1990). Songs of Aboriginal Australia [audio cassette] Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, AIAS 17.

Brown, Reuben Jay [recordist]. RB2-20121103-RB_01_03_MK01_MK02.wav (2012) at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/RB2/items/20121103/essences/1364365.

Brown, Reuben Jay. “Following Footsteps: The Kun-borrk/Manyardi Song Tradition and its Role in Western Arnhem Land Society”. PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2016.

Marett, Allan. “Ghostly Voices: Some Observations on Song-Creation, Ceremony and Being in North Western Australia”. Oceania 71, no. 1 (2000): 18–29.

Marett, Allan, Linda Barwick and Lysbeth Ford. For the Sake of a Song: Wangga Songmen and Their Repertories. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2013.

Marrgam, Brendan, Solomon Nangamu and Micky Yalbarr. RB2-20121103-RB_03.wav 00:24:49–00:25:44 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/RB2/items/20121103/essences/1364706.

Myers, Fred. “Ways of Place-Making”. La Ricerca Folklorica, no. 45 (2002): 101–19.

Nangamu, Solomon. RB2-20110825-RB_02.wav. 26:37–27:06 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/RB2/items/20110825/essences/1357033.

Nangamu, Solomon. RB2-20120609-RB_v01.mp4 08:46–10:56 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/RB2/items/20120609/essences/1360639.

Nangamu, Solomon. RB2-20120609-RBv_02. 08:39–09:01 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/RB2/items/20120609/essences/1360602.

Nangamu, Solomon. RB2-20120729-RB_09_edit.wav. 09:57.850–10:12.950 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/RB2/items/20120729/essences/1364600.

Nangamu, Solomon. RB2-20121103-RB_01_edit.wav. 07:23.200–07:48.200 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/RB2/items/20121103/essences/1364620.

Nangamu, Solomon. RB2-20121103-RB_02_edit.wav 42:52–44:24 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/RB2/items/20121103/essences/1364708.

Nangamu, Solomon. RB2-20121104-RB_01_XX_edit.wav. 00:05:20–00:05:30 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/RB2/items/20121104/essences/1365978.

O’Keeffe, Isabel [recordist]. [20061013IB02-05-MK02], (2006) in Linda Barwick, Allan Marett, Nicholas Evans, Murray Garde, Isabel O’Keeffe and Bruce Birch (2012) Western Arnhem Land Song Project data collection. The University of Sydney. http://elar.soas.ac.uk/deposit/arnhemland-135103.

O’Keeffe, Isabel. “Kaddikkaddik Ka-wokdjanganj ‘Kaddikkaddik Spoke’: Language and Music of the Kun-Barlang Kaddikkaddik Songs from Western Arnhem Land”. Australian Journal of Linguistics 30, no. 1 (2010): 35–51.

Ross, Margaret Clunies, Tamsin Donaldson and Stephen Aubrey Wild, eds. Songs of Aboriginal Australia. Sydney: University of Sydney, 1987.

Singer, Ruth. “Agreement in Mawng: Productive and Lexicalised Uses of Agreement in an Australian Language”. PhD thesis, The University of Melbourne, 2006.

Stanner, William Edward Henry. “The Dreaming”. In The Dreaming and Other Essays. Victoria: Black Inc. Agenda, 1953: 57–73.

Toner, Peter. “Melody and the Musical Articulation of Yolngu Identities”. Yearbook for Traditional Music 35 (2003): 69–95.

Treloyn, Sally. “‘When Everybody There Together … Then I Call That One’: Song Order in the Kimberley”. Context 32 (2007): 105–21.

Treloyn, Sally, Matthew Dembal Martin and Rona Goonginda Charles. “Moving Songs: Repatriating Audiovisual Recordings of Aboriginal Australian Dance and Song (Kimberley Region, Northwestern Australia)”. In The Oxford Handbook of Musical Repatriation, eds Frank Gunderson, Robert Lancefield and Bret Woods. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019: 591–607.

Warrabin, Harold. RB2-20121103-RB_01_03_MK01_MK02.wav at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/RB2/items/20121103/essences/1364365.

1 Following previous scholarship of Western Arnhem Land public ceremony, in this chapter we use the term “songset” to describe the named repertories of songs handed down to songmen. See Reuben Brown, “Following Footsteps: the kun-borrk/manyardi song tradition and its role in Western Arnhem Land society” (PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2016); Linda Barwick, Bruce Birch and Nicholas Evans, “Iwaidja Jurtbirrk Songs: Bringing Language and Music Together”, Australian Aboriginal Studies, no. 2 (2007), 6–34.

2 Solomon Nangamu, RB2-20120609RB_v02.mp4 08:39-09:01, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/FP7X-X254.

3 Solomon Nangamu, RB2-20110825-RB_02_edit.wav 26:37–27:06, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/R4FY-AR35.

4 Repatriation or archival recordings is a common methodology in applied ethnomusicology, and examples of song and dance revival from Australia and elsewhere abound. For a description of the process of return of archival recordings and images to the Kimberley and their use by ceremony leaders to revive dormant song and dance repertories of junba, see Sally Treloyn, Matthew Dembal Martin and Rona Goonginda Charles, “Moving Songs: Repatriating Audiovisual Recordings of Aboriginal Australian Dance and Song (Kimberley Region, Northwestern Australia)”, in The Oxford Handbook of Musical Repatriation, eds Frank Gunderson, Robert Lancefield and Bret Woods (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019). See also Bracknell, this volume.

5 Throughout this chapter words in Kunwinjku (K) and Mawng (M) are indicated and English translations are glossed in brackets the first time the word appears in the text. Standard orthographies are used. The authors have chosen to include these words and translations to show how manyardi singers included both words from their first language Mawng and lingua franca Kunwinjku (which their interlocutor Reuben Brown could speak at conversational level). The Mawng term “Arrarrkpi” has a number of senses including “Indigenous”, “human” and “male”.

6 Mirrijpu in Mawng means both “seagull” in the broader sense and silver gull (Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae). Nangamu also identified the species of seagull after which his song is named as the roseate tern (Sterna dougallii).

7 Solomon Nangamu, RB2-20120609-RB_v01.mp4 08:46–10:56, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/98XR-A024. For a longer version of the story, see Ruth Singer, “Agreement in Mawng: Productive and Lexicalised Uses of Agreement in an Australian Language” (PhD thesis, The University of Melbourne, 2006), 333.

8 Solomon Nangamu, Russell Agalara and Harold Warrabin, RB2-20121103-RB_01_edit.wav 16:20–16:47, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/6C8F-4737. The research referenced is unknown to the authors.

9 Linda Barwick, “Song as an Indigenous Art”, in The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, eds Sylvia Kleinert and Margo Neale (South Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press, 2000), 328.

10 Solomon Nangamu, RB2-20121103-RB_02_edit.wav 42:52–44:24, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/TSRV-YY61.

11 William Edward Hanley Stanner, “The Dreaming”, in The Dreaming and Other Essays (Collingwood, Victoria: Black Inc. Agenda, 1953), 61–62.

12 Stanner, “The Dreaming”.

13 Stanner, “The Dreaming”.

14 Fred Myers, “Ways of Place-Making”, La Ricerca Folklorica 45 (2002), 106.

15 Ronald Berndt, ed, Australian Aboriginal Art (Sydney: Ure Smith, 1964), 24.

16 Ronald Berndt, “Other Creatures in Human Guise and Vice Versa: A Dilemma in Understanding”, in Songs of Aboriginal Australia, eds Margaret Clunies Ross, Tamsin Donaldson and Stephen Aubrey Wild (Sydney: University of Sydney, 1987), 189.

17 Berndt, “Other Creatures in Human Guise and Vice Versa: A Dilemma in Understanding”.

18 This included Nakangila Tommy Madjalkaidj (senior), a Mawng speaker who came from the Mandjurngudj clan, who plays didjeridu on “cut 7” of the Simpson recordings at Oenpelli/Gunbalanya and Nabulanj Namunurr from North Goulburn Island, who sings on “cut 1”. For further discussion, see Brown, “Following Footsteps”, 246–50.

19 Sometimes spelled “Gwadbu”.

20 Solomon Nangamu, RB2-20120729-RB_09_edit.wav, 09:57.850–10:12.950, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/QDQH-P258.

21 In January 1948, a year after his visit to Goulburn Island, Ronald Berndt wrote to the superintendent at Warruwi, Reverend Alf Ellison, requesting portraits of a number of Mawng men and women with whom he had collaborated, including “Gamulgiri”, to incorporate in his 1951 publication. Ronald Berndt, Letter to Alf Ellison, 15 January 1948, Item 4.3.6. NTRS 38, Location 142/2/4, Northern Territory Archives.

22 Spelled elsewhere as “Mankowirr”.

23 Solomon Nangamu and Harold Warrabin, RB2-20121103-RB_01_edit.wav, 07:23–07:48, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/6C8F-4737.

24 Solomon Nangamu and Harold Warrabin, RB2-20121103-RB_01_edit.wav, 07:23–07:48, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/6C8F-4737.

25 Spelled elsewhere as “Nanguluminj” and “Nangolmin”.

26 Berndt, “Other Creatures in Human Guise”.

27 For further details of Marrwakara and Mirrijpu recordings made by Berndt, Barwick, O’Keeffe and others referenced in Table 2.1, see Appendix 1.2. in Brown, “Following Footsteps”.

28 See Linda Barwick, Isabel O’Keeffe and Ruth Singer, “Dilemmas in Interpretation: Contemporary Perspectives on Berndt’s Goulburn Island Song Documentation”, in Little Paintings, Big Stories: Gossip Songs of Western Arnhem Land, ed. John Stanton (Nedlands: University of Western Australia, Berndt Museum of Anthropology, 2013).

29 RB2-20121103-RB_02_12_MK01_practice.wav. https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/2Q12-MW41.

30 Margaret Clunies Ross, Tamsin Donaldson and Stephen Aubrey Wild, eds, Songs of Aboriginal Australia (Sydney: University of Sydney, 1987).

31 Western Arnhem Land songmen often make the distinction between the current composer and “main” singer of a songset who directs the performance in ceremony (“number one” singer) and other male relatives/singers who are considered apprentices to the main singer (the “second” singer/s).

32 For details, see recording sessions 19610301MK and 19640224MK detailed in Appendix 1.2. of Brown, “Following Footsteps”.

33 It is not uncommon for certain songs to be left out of a songset over the passage of time; sometimes entire songsets are no longer performed when the main songman passes away and male relatives cannot or do not wish to carry on singing the songs. For example, the wardde-ken songset Kurri (blue-tongue lizard) was performed as part of an elicited recording in 2006 by Simon Bidari for recordist Isabel O’Keeffe, but was no longer being performed during Brown’s fieldwork at Gunbalanya during the period of 2011–15.

34 For the music transcription analysis Brown referred to the following recordings: SAA-B-06-MK02 (1964) in Stephen Wild (1990). Songs of Aboriginal Australia [audio cassette] Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, AIAS 17; 20061013IB01-04-MK02, 20061013IB01-05-MK02, 20061013IB02-04-MK02, 20061013IB02-05-MK02 (2006) in Linda Barwick, Allan Marett, Nicholas Evans, Murray Garde, Isabel O’Keeffe and Bruce Birch (2012). Western Arnhem Land Song Project data collection. The University of Sydney. http://elar.soas.ac.uk/deposit/arnhemland-135103; RB2-20121103-RB_01_03-MK01_MK02.wav, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/G9SR-AX36; RB2-20121103-RB_02_07_MK01_MK02.wav (2012), https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/ABMD-3N38. In 2006, the singers “practise” the song for the first two recordings, as Nangamu helps Warrabin to sketch out the melodic contour. The melody then takes shape in the third and fourth recordings of the song, which forms the basis of the 2006 transcription. See Appendix 1.1 and Appendix 1.2 of Brown, “Following Footsteps” for further details of these recording sessions. Thanks to Linda Barwick who assisted with the analysis in Table 2.2.

35 O’Keeffe comments that Kun-barlang, Mawng and Kunwinjku people identify Kaddikkaddik songs in archival recordings “by recognizing the timbre of the voice of the Kaddikkaddik songman Frank ‘Kaddikkaddik’ Namarnangmarnang”. Isabel O’Keeffe, “Kaddikkaddik Ka-wokdjanganj ‘Kaddikkaddik Spoke’: Language and Music of the Kun-Barlang Kaddikkaddik Songs from Western Arnhem Land”, Australian Journal of Linguistics 30, no. 1 (2010), 59. Of course, this convention is not culturally unique to Western Arnhem Land.

36 For a detailed discussion of the significance of imitating the voice quality of earlier, often deceased singers in wangga repertories, see Allan Marett, Songs, Dreamings, and Ghosts: The Wangga of North Australia (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2005); Allan Marett, “Ghostly Voices: Some Observations on Song-Creation, Ceremony and Being in North Western Australia”, Oceania 71, no. 1 (2000), 24; Allan Marett, Linda Barwick and Lysbeth Ford, For the Sake of a Song: Wangga Songmen and Their Repertories (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2013), 56.

37 Whereas Ganawa’s preferred tempo for moderate rhythmic mode songs is 105–109 bpm, Nangamu’s is 105–131 bpm. See Appendix 3 in Brown, “Following Footsteps”.

38 Peter Toner, “Melody and the Musical Articulation of Yolngu Identities”, Yearbook for Traditional Music 35 (2003), 89, https://doi.org/10.2307/4149322.

39 Solomon Nangamu, conversation with the author. See recording session https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/E1CZ-4E20.

40 Brendan Marrgam, Solomon Nangamu and Micky Yalbarr, RB2-20121103-RB_03_edit_01.wav, 00:24:49–00:25:44, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/64HC-GZ26.

41 Micky Yalbarr, RB2-20121103-RB_01_edit.wav, 11:04, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/6C8F-4737.

42 Solomon Nangamu, RB2-20121103-RB_02_edit.wav 36:40–37:14, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/93HZ-H861. It was not clear from our discussion whether “Inyalatpa” is a specific place name in Manangkardi, or a Manangkardi term for “home/county”, which Nangamu suggests through his translation using the Kunwinjku word kunred. “Inyalatpa” also resembles another Mawng place name “Inyalatparo” on South Goulburn Island.

43 Solomon Nangamu, RB2-20121104-RB_01_XX_edit.wav, 00:05:20–00:05:30, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/1TQK-Z450.

44 Solomon Nangamu, RB2-20110825-RB_02_edit.wav 28:37–29:00, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/R4FY-AR35.

45 Solomon Nangamu and Harold Warrabin, RB2-20121103-RB_02_edit.wav, 26:10, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/93HZ-H861.

46 https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/G9SR-AX36. The pairing of fast and slow songs that are thematically linked is a feature of Aboriginal music which has been discussed in relation to junba music from the Kimberley and yawulyu/awelye (women’s ceremony) music of Central Australia, and in relation to lirrga from the Daly region. See Treloyn’s discussion of song “mates” in Scotty Martin’s junba repertory. Sally Treloyn, “‘When Everybody There Together … Then I Call That One’: Song Order in the Kimberley”, Context 32 (2007), 116. See also Linda Barwick’s discussion on the paralleling of slow and fast Mangamunga songs: Linda Barwick, “Performance, Aesthetics, Experience: Thoughts on Yawulyu Mungamunga songs”, in Aesthetics and Experience in Music Performance, eds Elizabeth MacKinlay, Denis Collins and Samantha Owens (Newcastle UK: Cambridge Scholars, 2005), 8, and her analysis of paired items in lirrga, Linda Barwick, “Tempo Bands, Metre and Rhythmic Mode in Marri Ngarr ‘Church Lirrga’ Songs”, Australasian Music Research 7 (2002), 81–83. Brown’s analysis of five contemporary kun-borrk/manyardi performance events found that songmen performed more than two song items with similar tempo or the same rhythmic mode in sequence, starting from slow tempo songs and moving to fast, then returning to slow at the end of the performance. See Brown, “Following Footsteps”, 315.

47 This song text transcription is based on discussions with Harold Warrabin and Solomon Nangamu and on previous transcriptions informed by the singers discussed in Barwick, O’Keeffe and Singer, “Dilemmas in Interpretation”, 55.

48 Solomon Nangamu, RB2-20120609-RB_v02.mp4, 00:00–01:50, https://dx.doi.org/10.26278/FP7X-X254.