9

Mermaids and cockle shells: Innovation and tradition in the “Diyama” song of Arnhem Land

Mermaids and cockle shells

Download chapter 9 (PDF 2.8Mb)

Introduction

In the Western Arnhem Land community of Maningrida, 500 kilometres east of Darwin, the recent creative expression of the all-female Ripple Effect Band has reignited interest in the origins of the “Diyama” song. As the first women in their community to take up instruments and form a band, their innovative musical practices have prompted recollection and discussion of cultural practices among women of the region, particularly An-barra family members of band member Stephanie Maxwell James. Their perspective provides new knowledge that contests the descriptions of song practice in archives and historical records. The new interpretations of the “Diyama” song and its origin story challenge the fixity of archival objects, recognising the law held in oral traditions and the prerogative of song custodians to respond creatively to changing contexts over time.

“Diyama” is a song written by Stephanie Maxwell James.1 Sung in the Burarra language, it is named after the cockle shells that are found in the surrounding coastal regions. The song tells the story of the mermaids that inhabit the waters of the An-barra homeland of Gupanga, 40 kilometres east of Maningrida. Stephanie is among the few women from the region to compose and perform songs in public, as a member of the Ripple Effect Band. She is also part of a lineage of An-barra musicians who have performed versions of this song over three generations.

The title “Diyama” is shared with a songset of the traditional kun-borrk genre,2 an Indigenous song style known across Western Arnhem Land. The kun-borrk called “Diyama” is attributed to the creative powers of mermaid spirits as received in a dream, which is typical of kun-borrk songs across Western Arnhem Land.3 In 1960, anthropologist Lester Hiatt made the first recording of “Diyama” sung by Stephanie’s grandfather, Mulumbuk, with a description of how Mulumbuk first received the song.4 The recordings and liner notes are held in the archive of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS).

In 2017, An-barra Elder Mary Dadbalag gave an alternative account of the origins of the “Diyama” kun-borrk, explaining that it was her eldest sister who saw the ancestral spirits come out of the water and sing and dance “Diyama”, instructing her to pass the songset to her younger brothers, Harry Mulumbuk and Barney Geridruwanga. In the 1960s, it was very unusual for a woman to receive kun-borrk and this may have directed non-Indigenous researchers away from asking women about the song’s origins. Men are responsible for singing and playing the musical accompaniment of kun-borrk and therefore other aspects of song knowledge discharged by women, such as dance instruction, correcting the singers and providing authoritative accounts of song origins and meanings, were arguably overlooked. It was also a time of social change and there may have been other circumstances that prevented women from claiming ownership of the song.

This chapter contends that a multiplicity of truths and narratives can exist in archives, oral stories and historical narratives, and examines how reinterpretations of stories and songs can be used to construct identity. We suggest that at the time the origins of the “Diyama” song were recorded, there were social factors contributing to the dominance of the male perspective. Drawing upon archival theory that questions the permanence of historical storytelling and archival objects, we take into consideration the perspectives of An-barra women, who are responding to and reinterpreting the story of “Diyama” in narrative and in song.

This chapter arose out of conversations between An-barra educator Cindy Jinmarabynana and Ripple Effect Band member Jodie Kell. It will focus on two cases of engagement with the 1960 audio recording and accompanying written notes of the “Diyama” song; an alternative version of the origins of the song recorded in an interview in 2017 and the reinterpretation of the song in a contemporary setting by a descendant and her band.

Cindy Jinmarabynana is an An-barra woman currently living in Maningrida and teaching at the Maningrida school. Her patrilineal clan group is Marrarrich/Anagawbama and her homeland, Ji-bena, stretches across the floodplains to the south-east of Maningrida. Cindy is a junggay (B: cultural manager)5 for the An-barra estate of Gupanga on the mouth of the Blyth River, where she grew up, learning from her Elders in a traditional way.

When I hear the “Diyama” song, it makes me cry. It makes me cry because, the way I see it, I have knowledge from when I was a little kid in Blyth River, in my own mother’s country. That’s where I got my knowledge by sitting down and listening to the old people. Especially the old man Frank Gurrmanamana, Betty’s father. He taught me that knowledge.6

Jodie Kell is a non-Indigenous woman who grew up on Darramuragal Country, part of the Eora Nation, in the north of Sydney. She worked as a teacher at Maningrida College from 2002 to 2006, starting a long connection with the people of the Maningrida region. She currently manages and performs in the Ripple Effect Band. She has accompanied Cindy and her family to her estate of Ji-bena, hunting in the rich fertile floodplains as far as Gupanga, learning about the culture and stories connected to the An-barra clan and Country.

Jodie collated this chapter, reviewing literature and archival recordings and working with Cindy to conduct interviews, discuss issues of archives, and research and document knowledge of the “Diyama” song and story for future generations. We wanted to record and publish Cindy’s mother’s story of the song’s origin, being aware of the power of the written word and archival objects, such as the recording of “Diyama” on the 1966 album. We hope that this story will shed light on the changing social structures for women in relation to kun-borrk and music-making in Maningrida, and the history of the “Diyama” song which led to the Ripple Effect Band’s song about the mermaids who inhabit the waters of the An-barra homelands. By analysing a recent performance and recording of this song, we seek to demonstrate how the history of the “Diyama” song is interwoven in the Ripple Effect Band’s popular music performance. We will examine how these contemporary iterations are both influenced by and depart from the version held in the archive. We will comment on how this pertains to the negotiation of agency and construction of identity, particularly from the standpoint of women.

We also hope to add to the existing archival recordings, song recordings and writing about the “Diyama” song, with Cindy, as a junggay (B: cultural manager), wanting to document important knowledge about the “Diyama” story and song for the future of the An-barra clan.

I want to bring that evidence back. That evidence tells us who we are, what is our clan and where we come from.7

An-barra people

The An-barra people are part of the Burarra-speaking language group that also includes the Martay people to the east. Their language is closely related to Gun-nartpa from the inland floodplains, and they are close relatives of their western neighbours the Na-kara.

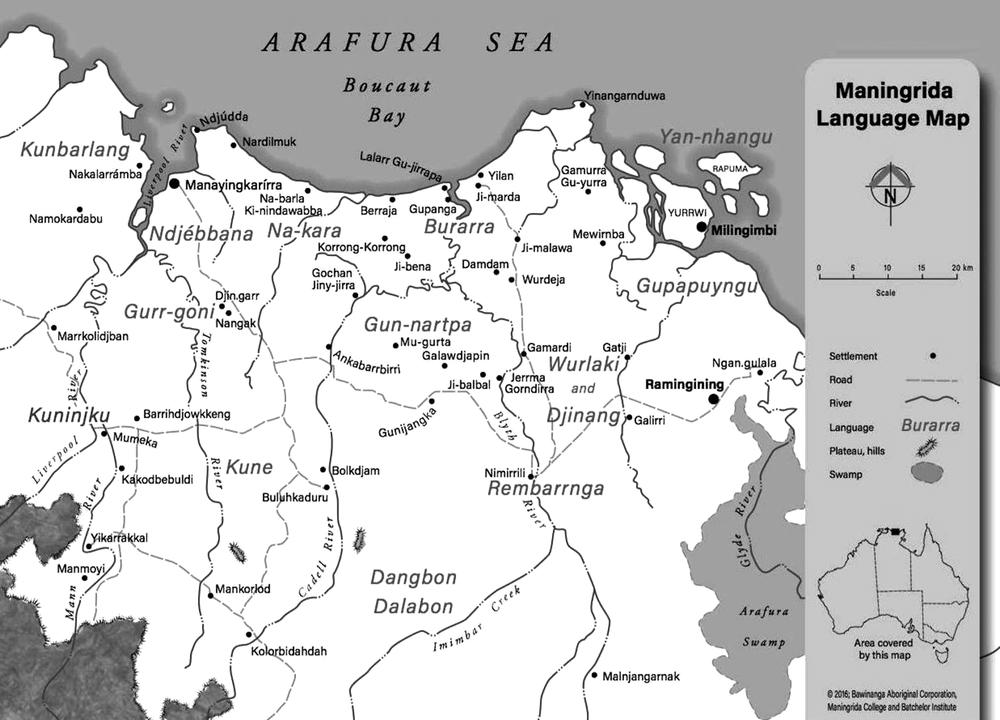

The Burarra estates lie to the east of Maningrida as marked on the Maningrida Language Map (Figure 9.1). The Blyth River, called An-gatja Wana (B: Big River), runs through the heart of Burarra territory, starting in the sandstone plateau country to the south through eucalyptus forest, until it reaches the saltwater fringed by mangroves and many small creeks from the floodplains that exit past the sand spit at Lalarr Gu-jirrapa.

Figure 9.1 Language map of the Manayingkarírra (Maningrida) region (2016). Courtesy of Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation, Maningrida College and Batchelor Institute. Map by Brenda Thornley.

The An-barra estate is situated along the coast and the mouth of the river, and An-barra people refer to themselves as Saltwater people (see Figure 9.2). Anthropologist Lester Hiatt explains that the estate boundaries are not fixed; rather, the differentiation of estate land is based around important sites.8 The “Diyama” song refers to two sites, Gupanga on the western bank and Lalarr Gu-jirrapa at the mouth of the river, and it is in the waters between the two sites at the river mouth where the mermaids are found.

Figure 9.2 Map of An-barra significant sites. The map shows the Burarra language groups An-barra, Martay and Marawuraba (these two groups tend to call themselves Martay), and Maringa (also known as Gulula). This map is based on conversations and travels with Cindy Jinmarabynana and An-barra Burarra people, and maps by Lester Hiatt, Kinship and Conflict, 1–19 and Betty Meehan, Shell Bed to Shell Midden (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1982).

In more recent times, An-barra and Burarra people have moved to live in the community of Maningrida. Originally set up as a government trading post in the 1950s, Maningrida is now home to one of the most linguistically diverse communities in the world, with 15 languages spoken or signed every day among only a few thousand people.9 Living away from their homelands has intensified a sense of longing and nostalgia for their Country which has become a focus for musical expression among An-barra and neighbouring Na-kara musicians.

Like other groups across Arnhem Land, An-barra people divide the world into two patrifilial moieties, Yirrchinga and Jowunga. People, animals, plants and places belong to one of these moieties. This is the basis for the kinship system that dictates how people relate to each other, to Country, and to ancestral stories, songs and dances. The two moieties are exogamous and the kinship system that binds them, called the skin system, regulates whom people can or cannot marry and governs social interaction based on eight classificatory subsections. People inherit their bapururr (B: clan) from their father and they are seen as responsible for their mother-clan’s Country, songs and stories. There are about a dozen An-barra patrilineal clans, with the Ana-wulja clan central to the story of the “Diyama” song.

Diyama

The song title, “Diyama”, refers to the striped cockle shellfish, tapes hiantina, which stands out as a prolific food source for Burarra people and other groups of the region, both in quantity and consistency throughout the year. The shellfish are collected in the sandy river mouths along the coast, where hunters stand in the shallow saltwater and dig into the sandy bed to a depth of between 1 and 15 centimetres. The diyama tend to aggregate, so each dig reveals a handful of the shells. These are then cooked either in the coals of a fire or boiled in water, or they can be kept alive in damp cool storage for days.

Figure 9.3 Diyama shells (Tapes hiantina) of the marrambai or “black duck” pattern with radiating dark bars across the shell. This is differentiated from the an-gedjidimiya or “whistle duck” pattern. Photo by Jodie Kell.

In the 1970s, anthropologist Betty Meehan lived with the An-barra people and documented details of their shellfish harvest between July 1972 and July 1973. She noted that, over the year, the An-barra community of around 34 people collected at least 6,700 kilograms of shellfish. Out of the 29 different species collected, Meehan rated diyama as the most important because it was collected consistently throughout the year and made just over 60 per cent of the total annual yield.10

Figure 9.4 Members of the Ripple Effect Band and families hunting for diyama on the Na-kara estate of Na-meyarra. From left to right: Rona Lawrence, Marita Wilton, Zara Wilton and Tara Rostron. Photo by Jodie Kell.

For the An-barra people, the abundance of the diyama shellfish is associated with a unique origin story about werrgepa (B: mermaids), who dig underwater diyama beds in the mouth of the Blyth River.11 Their song has the ancestral power to put flesh inside the shells. While diyama are not found at Gupanga itself, it is there that the mermaids live and assure a bountiful supply through their song. Cindy describes how diyama are formed through a metaphysical connection to the An-barra estate of Gupanga, where white clay is found. Rrakal (B) is white pipeclay used for ritual body paintings and bark paintings. Given by the original ancestors, this substance of ceremonial significance is an intrinsic part of the Diyama story.

This diyama comes from white clay. They call it rrakal. It is the rrakal that junggay (B: cultural managers), like me or my sisters, spread out and say the name of the country to form that diyama. Towards the end of the dry, when the rain is forming, then the rrakal spreads and forms into diyama. When it forms, we hear this dilartila (B: Australian magpie lark). It’s a black and white bird Dreaming. Our totem, dilartila, who says “dill, dill”. Every year, from the ending of the dry season to the starting of the rain, the junggay will get the clay and say the name of the country – for example, Lalarr Gu-jirripa or Djunawunya – and by spreading that clay, they form the diyama from the song line.12

This story is connected to the practice of dalkarra (G: the singing out of called names of sacred sites by ceremonial leaders of public ceremonies).13 In Eastern Arnhem Land, the singing of place or clan names is an important part of mortuary and other public ceremonies.14 In this case, the clay is a physical embodiment of the metaphysical power of creation, where the calling out of names of Country causes the proliferation of diyama seashells in the underwater beds. It also relates to the story of the mermaids, who appeared in a dream, singing the name of the diyama shellfish, ensuring their continued harvest.

Where did the “Diyama” song come from?

The origins of the “Diyama” song date back to the 1950s, when a new kun-borrk emerged from the An-barra homelands on the mouth of the Blyth River. The singer was Mulumbuk, also known as Harry Diyama.15 Lester Hiatt described Mulumbuk as a major figure in the establishment of the Maningrida community in the 1950s.16 He later featured in the 1980 ethnographic film by Hiatt and Kim McKenzie called Waiting for Harry that documented a funeral ceremony on the An-barra estate of Djunawunya.17

In 1960, Hiatt recorded Mulumbuk singing a kun-borrk style song that was later included on the 1966 Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies vinyl record,18 Songs from Arnhem Land.19 Side A of the album consists of songs in the Eastern Arnhem Land style called manikay (B). Side B consists of Western Arnhem Land kun-borrk-style songs, and the opening kun-borrk song is sung by Mulumbuk. As is usual for songs of the kun-borrk genre, Mulumbuk told Hiatt that he learned the songs from the spirits of the deceased:

One night during a dream his deceased brother took him to the bottom of the Blyth River, and there they heard spirits of the dead singing it.20

Nearly 60 years later, another version of the origin story has emerged. In 2017, we sat in Cindy’s daughter’s yard in Maningrida and recorded her mother, An-barra Elder Mary Dadbalag, the last of the generation to have lived at Gupanga when “Diyama” was first performed. Unlike the story recorded by Hiatt, she asserts that it was her mother’s sister, Elizabeth, instead of Mulumbuk, who learned the songs from ancestral spirits in a dream.

One of her [Mary’s mother’s] eldest sisters, Elizabeth, had a dream. All these people came out from the river, and it was low tide at night. They came up with strings and dilly-bags full of diyama, and they were talking to her. They said to her, “Hey, wake up sister. Wake up. We’re full of diyama here. We’ve got diyama clay here. You tell our kids that they’re the ones who are responsible for this diyama. They’re the ones who will say the names of the places and spread that diyama like junggay.”21

According to this story, rather than the dreamer being taken to the bottom of the river, the mermaids came out of the water wearing ceremonial objects such as rrawka (B: ceremonial feathered armbands), and they sang and danced the song for Elizabeth, telling her to pass it on to her younger brothers, Harry Mulumbuk and Barney Geridruwanga. “She had to give [it to] them because, if she would have been a man, she would have been taking over singing this song.”22 As women are not allowed to sing kun-borrk songs, Cindy explained that Elizabeth needed to give the song to her male relatives.

She told my two uncles – that is, David Maxwell’s father, old man Harry Mulumbuk and my uncle Barney Geridruwanga – “I’m the eldest sister. You two sit down. I had a dream.” They sat down next to the fire and she started to sing that song, “Diyama”. She said, “Our ancestors of the Ana-wulja clan, An-barra people, I had a dream and they gave me this song, so I’ll pass it on.”

That was what they had told her to do. She was singing at the same time she told those two boys to get the clapsticks and they started to sing, and they were starting to sing what she told them to sing, “Aa-aa-aa an-diyama,” like that and they picked it up really quickly. They were aburr-delipa (B: small children), ten or eleven years old.23

It is significant that a woman received a song in a dream, as there are very few accounts of the transmission of songs from women to men in this region. One example is the wangga song “Yendili No. 2”, which was received in a dream by Marri Ngarr woman Maudie Attaying Dumoo, who gave it to her husband, Wagon Dumoo, to perform.24 Musicologist Allan Marett described the song as “almost unique among the various wangga repertoires in that it was composed by a woman”.25

Figure 9.5 Mary Dadbalag (left) and her daughter, Cindy Jinmarabynana, discussing the story of “Diyama”. Photo by Jodie Kell.

Mary’s memory of the origin of the song, as told to her, tells a story of women as composers, sharing their dreams and the songs heard in them, so they could be performed in public. Her perspective sheds light on the role of women in the composition and transmission of this region’s music in the past and the present. The story documented by Hiatt suggests a sense of the dreamer, Mulumbuk, looking upon the mermaids and hearing their song and then taking it back and singing it himself. Mary’s version describes a more active role for the mermaid spirits who came out of the water to wake the dreamer and give her the song, directing her to pass it on to her family members, while also demonstrating and passing on its associated dances.

The ancestor spirits, they came out from that water, walking on the beach. But that other one she saw is like a mermaid with arm band around her – you know, like traditional costume. In that dream, my mum said to my sisters, “In dream dje! Awurr-bony diyama, awurr-banyjinga (B: they have gone to get diyama shells under the water).” They already put that [flesh inside the] diyama, the spirit people, and that slow dance – you know, the one when we dig and dance and then we put it on our head swinging. What we are putting on our head is string bags full of diyama.26

While Mulumbuk is undisputed as the first person to sing this song in public, Dadbalag’s version of events raises questions about its origins. Rather than seeing these stories as conflicted, it is useful to explore what these different perspectives tell us about how historical events are remembered and recorded. In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, the transmission of knowledge is enacted orally through songs and stories, and visually through dance and painting. This leads to multiple narratives that shape collective memory, influencing the construction of community and individual identity. This origin story paints a picture of women actively involved in communication with ancestral spirits, and its recent emergence suggests that women are ready to share their stories to strengthen the right of women to compose and perform songs.

Archivists such as Eric Ketelaar and Terry Cook question the relative fixity of historical understanding. Ketelaar comments that subsequent events, new interpretations and sources of history are all valid and have the effect of changing the view and reopening historical cases.27 Cook states that many historians are now seeing that:

identity in the past is shaped by common or shared or collective memory animating invented traditions and that such identities, once formed or embraced, are not fixed, but very fluid, contingent on time, space, and circumstances, ever being re-invented to suit the present, continually being re-imagined.28

The omission of a woman’s perspective on the “Diyama” song could be in part because of the status of women at the time. As women did not sing or perform music in public, researchers may not have thought to ask them about this song, or perhaps women themselves did not feel empowered to tell the story of a woman receiving a men’s song in a dream. The 1960s were a time when the recordist was seen as a guardian protecting the static archival object, suggesting one “truth”. This dominance of the documented narrative tended to reflect the gender bias embedded in society, with archives becoming “active sites where social power is negotiated, contested and confirmed”.29

When Jodie asked Cindy why she thought this story had not surfaced before, Cindy said:

Well, Betty and Les [Hiatt], they don’t know that story. Those women, they hid that story. Les only knew the song and story when Harry sang it. He didn’t know the history about the song. Because I heard that story when my grandmother told me, when I was age … six or seven. I took that story in my heart when this old lady told me the story, because she had been carrying that story from her sister.30

Our approach seeks to allow for the possibility of multiple narratives and perspectives through recognising a diversity of sources of knowledge. Faulkhead et al. see this as “acknowledging Indigenous frameworks of knowledge, memory and evidence”.31 This brings us back to Cindy’s desire to share her mother’s story and document it as evidence before it is too late. Her mother had been carrying this story and now it is recorded as part of the archival corroboration of the “Diyama” song, adding to a rich and complex history documented through oral storytelling and song that continues to this day.

Transmission, re-creation and innovation

The impetus for the recording of the “Diyama” origin story came about because of the Ripple Effect Band’s new iteration of the “Diyama” song. The Ripple Effect Band are an all-women’s rockband that emerged out of Maningrida in 2017, singing in five Aboriginal languages of the region.

Figure 9.6 The Ripple Effect Band performing “Diyama” at the Darwin Festival in 2020. From left to right: Jodie Kell, Jolene Lawrence, Marita Wilton, Lakita Taylor (Stephanie’s daughter) and Stephanie Maxwell James. Photo by Benjamin Warlngundu Bayliss.

When Stephanie Maxwell James, an An-barra woman of the Ana-wulja clan, composed “Diyama” and performed it with the band, this was the first time in living memory that a group of women was singing about the mermaids that live in the waters off Gupanga. Following our debut performances at Maningrida, the Bak’bididi Festival in Ramingining and the Milingimbi Gatjirrk Cultural Festival, the band recorded the song as part of the Wárrwarra (Ndj: the sun) EP released in 2018.32

While distinctive, this new version of the song is one of many reinterpretations of the “Diyama” song over three generations as shown in Table 9.1. Popular bands such as the Letterstick Band and Wildwater preceded the Ripple Effect Band with recordings and performances of songs that directly reference the “Diyama” kun-borrk. Many of these songs can be found on CDs or online streaming services. As well as this, copies of the original 1960 recording circulate around the community as people Bluetooth the songs from phone to phone, listening to the kun-borrk as readily as more contemporary versions of the song.

Listening to archival objects, such as heritage recordings, enables engagement with knowledge held in cultural performance and song and can lead to the reinvigoration of contemporary performance practices. There are many examples across Australia, such as the work of the Wirlomin Noongar Language and Stories Project in Western Australia documented by Clint Bracknell and the collaboration between a team of researchers and the Manmurulu family of the Arrarrkpi (Mawng-speaking people) of the Northern Territory.33 In discussing the repatriation of junba songs of the Kimberley region of north-west Australia, Matthew Denbal Martin sees the value of the recordings for teaching and learning. He comments that the recordings hold the spirits of the old people whose voices are heard in the recordings:

Listening to the songs reminded me of all the old people and it was like they were in me. They were sitting beside me, you know. And I picked them songs up. It was like they was telling me “that way. Sing this song that way”. It was like they were telling me which way to sing.34

This form of engagement is apparent in re-creations of the song of the mermaids through an inherited lineage of An-barra musicians, leading to the proliferation of the song in a range of media.

Musical innovation is an integral aspect of the story of the “Diyama” song, starting back at the emergence of the kun-borrk from the An-barra homelands. Betty and Lester Hiatt describe “Diyama” as the “easternmost example of the borg [kun-borrk] style” and claim Mulumbuk as the only Burarra person who sang a kun-borrk-style song.35 Usually, the more easterly Burarra-speaking groups would own and sing manikay (B: clan songs).36 They go on to suggest that:

[b]ecause of marriage irregularities in the previous generations, Mulumbuk and several other members of his clan have changed their moiety affiliations in order to bring their own marriages into conformity with the rule of moiety exogamy. This has entailed a serious disturbance of their ritual status, including loss of recognition as joint owners of any mortuary song.37

Mulumbuk was a Yirrchinga man. Gupanga is a Jowunga estate and so he would not have been able to sing the associated manikay due to the rules of exogamous moieties. Using the medium of kun-borrk enabled him to own and compose original songs, receiving them in dreams and passing them on to his descendants. Expressing direct communication with ancestral spirits, the song strengthened his rights to the Gupanga estate. He subsequently gained status travelling to other clan estates across the region as a jalakan (B: song leader) with a ceremonial troupe to perform the “Diyama” kun-borrk and associated bunggul (B: dances).38

Table 9.1 Documented representations of the “Diyama” song and/or story. This does not include many informal and unrecorded ceremonial performances such as the opening of the local health clinic, school concerts and festivals. (See References for further information on the recordings in this table.)

| Song/film title | Singer/performer | Year | Style | Media format (Publisher) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Diyama” | Mulumbuk | 1966 | borrk | Songs of Arnhem Land (AIAS) vinyl |

| Waiting for Harry | Mulumbuk | 1979 | documentary film | AIAS, film |

| “An-barra Clan” | Letterstick Band | 1994 | borrk sung over reggae | (CAAMA Music) CD |

| “Rrawa” | Letterstick Band | 1995 | reggae | Demurru Hits CD |

| “Bartpa” | Letterstick Band | 1995 | Demurru Hits CD | |

| “Diyama” | David Maxwell and others | 1997 | ||

| “Diyama” | David Maxwell | 2004 | borrk | Diyama CD |

| “Diyama/Mimi” | David Maxwell and Crusoe Kurrtal | 2004 | borrk with samples and synthesiser | Diyama CD |

| “Gupanga” | Letterstick Band | 2004 | reggae | Diyama CD |

| “Blyth River” | Letterstick Band | 2004 | country rock | Diyama CD |

| Soundtracks of Maningrida | Letterstick Band | 2004 | documentary film | (CAAMA Music) film |

| “Ngarnji Mamurrng” | David Maxwell and others | 2006 | borrk | Mamurrng ceremony, live |

| “Rrawa” | Wild Water | 2007 | reggae | Rrawa CD |

| “Maningrida Diyama” | Wild Water | 2007 | borrk sung over reggae | Rrawa CD |

| “Make it Through” | Elston Maxwell, Djolpa Mackenzie, Cindy Jinmarabynana, Marita Wilton, Patricia Gibson | 2016 | hip-hop | Indigenous Hip Hop Projects film clip |

| “Blyth River” | Ripple Effect Band | 2017 | country rock with borrk | Live performance at Ramingining Festival |

| “Diyama” | Ripple Effect Band | 2017 | country rock with borrk | Wárrwarra EP |

| “Jarracharra” | Ripple Effect Band with Bábbarra Women’s Centre Jess Gunjul Phillips |

2019 | sound installation | Exhibition at the Australian Embassy, Paris |

As well as adopting an atypical song genre, Mulumbuk recorded the song with Lester Hiatt on a battery-powered tape recorder in 1960, demonstrating his ability to utilise new technologies and extrinsic knowledge to create an enduring record of his singing that can be played again and again after his passing. Ethnomusicologist Paul Greene comments that modern recording technologies have opened up “new directions for musical expressions and evolution, inspiring new logics of music creation and empowering local cultural and expressive values”.39 The innovative development of creating a permanent audio record of the “Diyama” kun-borrk has contributed to the continuation of realisations of the “Diyama” narrative as told in song.

Sustained engagement with the “Diyama” kun-borrk and the 1960 recording has contributed to a proliferation of the song and its themes among the subsequent generations of An-barra and Na-kara musicians. After Mulumbuk passed away, his sons, David and Colin Maxwell, followed in their father’s footsteps, taking on responsibility for the performance of the “Diyama” ceremony and travelling across Arnhem Land to perform at ceremonial events. Like their father, they also adopted new technologies in the expression of their An-barra identity. They formed the Letterstick Band, playing a distinctive style of rock-reggae, fusing elements of their inherited kun-borrk song series with globalised popular music styles.

In her article about music technology at Wadeye, Linda Barwick proposes that the emerging non-traditional musical forms and their dissemination through digital means “continue to develop a strategic assertion of cultural and territorial autonomy and identity through song that was and is also fundamental to traditional musical forms in the area”.40 This “strategic blend of traditionalism and innovation”41 is a feature of the Letterstick Band, as they used contemporary music practices and documentary film-making to assert clan affiliation and continue the innovative legacy of their father.

The many different versions of this song over time are an example of what is called intertextuality. Burns and Lacasse define intertextuality as “a network of songs, styles, artists and consumers influenced, directly or indirectly, by the music and artists that came before”.42 This can be applied to the intricate network of relationships that link An-barra musicians and their estates to the “Diyama” song and its association with Gupanga. Linguist Ken Hale used the phrase “the persistence of entities through transformation”43 in his article on song as re-creation. Cindy comments that the range of styles that encompass performances of “Diyama” has contributed to the lasting popularity of this kun-borrk:

Everybody sings it now. They all enjoy with our young people. This is one other thing we get to see growing, you know. We have passed that song up to our future generations.44

This song that was originally accompanied by only two traditional instruments, the an-gujaparndiya (B: clapsticks) and ngorla (B: didjeridu), can still be heard today in kun-borrk style, but also with contemporary instrumentation and mixed media. Musicians like David Maxwell from the Letterstick Band, and now his daughter Stephanie, have followed in the footsteps of Mulumbuk, adopting new technologies and musical practices to reinterpret the song of the mermaids in different forms. In so doing, they assert their cultural identity in the changing social structures of modernity.

A new performance of “Diyama”

I do a lot of dance: Black Crow, Shark and Crocodile dance, and Diyama. I have traditional and then play in a band. Because my dads,45 you know, they played in a band, so I am following in their footsteps.46

My daughter wrote a song for the mermaids. It’s my dreaming. We call it werrgapa “mermaid” (B), the spirit and the land for the An-barra people staying in one place called Gupanga on the Blyth River.47

Figure 9.7 David Maxwell (left) on stage with his daughter, Stephanie Maxwell James (right), at the Bak’bididi Festival in Ramingining in 2017. Behind is Rona Lawrence on bass guitar and Tara Rostron on electric guitar. Photo by Eve Pawley.

The performance at the Bak’bididi Festival in Ramingining in 2017 was the first public performance of the song by the Ripple Effect Band outside of the Maningrida community. We were joined by David Maxwell on stage. This was the first time any kun-borrk song had been sung by a man accompanied by a group of women. The contrast between his vocal style and that of his daughter brought great excitement to the crowd and across Arnhem Land, as social media enabled the spread of this historic moment. Through his participation, he confirmed his daughter’s cultural identity and bestowed authority on the changing social structures that are now allowing women to perform music in public.

Writing about the Letterstick Band’s setting of Mulumbuk’s “Diyama” kun-borrk in “An-barra Clan”, Aaron Corn says that brothers David and Colin Maxwell were able to balance the “continuity of musical traditions against creative engagement with new musical media and technology”.48 Similarly, the use of contemporary instrumentation can be seen to bypass some of the gendered restrictions and allow women to play instruments and accompany a senior songman singing traditional songs. In this extraordinary moment, a song re-created and performed by father and daughter was made possible by the context of its contemporary musical setting.

The subsequent recording of the “Diyama” song by the Ripple Effect Band included the voice of David Maxwell.49 In the middle of the song and at its ending, he sings the “Diyama” kun-borrk. This was recorded in the Wiwa Music and Media studio in Maningrida on a Zoom H6 audio recorder when he sang two iterations of this kun-borrk, one for the middle section and one for the ending of the recorded song. As will be shown later in our analysis of this song, David based his song on the 1960 recording, re-creating the melodies and phrasing of his father.

David passed away before he could hear the final recording of the song. But when we placed the audio recording of his kun-borrk song over the tracks, it fitted and it felt like he was there in the room with us. By allowing us to include his voice in both live and recorded performances of the song, David was reinforcing his daughter’s legitimacy and endorsing a new modality of women’s singing in a way that was as innovative as the Letterstick Band was in the 1990s or Mulumbuk in singing kun-borrk in 1960. The Ripple Effect Band’s rendering of the “Diyama” song enables a new voice, a female voice, and a new expression of tradition.

In recording these songs, we have also enabled the creation of new archival artefacts in the form of audio and film recordings of song and performance that can enhance the oral histories, heritage recordings, and accounts of song and dance performance by An-barra people and surrounding communities.

Music analysis

In this section, musical analysis of the 2018 recording from the Wárrwarra EP shows how Stephanie and her father allude to Mulumbuk’s song, using contemporary production techniques to bring new perspectives to the “Diyama” song.

| “Diyama” (Transcription by Stephanie Maxwell James, Jodie Kell and Margaret Carew.) |

Stephanie Maxwell James, David Maxwell and Jodie Kell |

|---|---|

| VERSE 1 | |

| Ana-munya gaba ng-garlmana | I got up in the morning |

| Ngi-jarl ngu-bamana | I hurried along |

| Nga-nana bartpa | I saw the waves |

| Gu-buna gu-jinyja | The waves were hitting the shore |

| Lika warrgugu ngu-ni | I couldn’t stop thinking about my country |

| Nga-nana Lalarr Gu-jirrapa | I saw the place, Lalarr Gu-jirrapa |

| Gu-nachichiya gu-jinyjirra rrawa Gupanga | Facing across from my country, Gupanga |

|

CHORUS | |

| Aa Diyama | Ah Diyama |

| Aa Diyama | Ah Diyama |

| Aa Diyama | Ah Diyama |

| VERSE 2 | |

| Jungurda a-wena apula | My grandfather told me |

| Awurr-merdawa yerrcha | About the mermaid spirits |

| Ana-munya gu-nirra | At night time |

| Jina-beya jina-workiya | They always come out |

| Gala ngu-yinmiya ng-galiya | I can’t hear them |

| Ngu-marngi awurr-gatiya | I know they are there |

| Ya Gupanga rrawa gun-molamola | In my beautiful country, Gupanga |

| CHORUS | |

| Aa Diyama | Ah Diyama |

| Aa Diyama | Ah Diyama |

| Aa Diyama | Ah Diyama |

| VERSE 2 | |

| Jungurda a-wena apula | My grandfather told me |

| Awurr-merdawa yerrcha | About the mermaid spirits |

| Ana-munya gu-nirra | At night time |

| Jina-beya jina-workiya | They always come out |

| Gala ngu-yinmiya ng-galiya | I can’t hear them |

| Ngu-marngi awurr-gatiya | I know they are there |

| Ya Gupanga rrawa gun-molamola | In my beautiful country, Gupanga |

Table 9.2 “Diyama” (Transcription by Stephanie Maxwell James, Jodie Kell and Margaret Carew).

The use of spirit language is common to the kun-borrk songs of Western Arnhem Land.50 In the 1960 recording of “Diyama”, Betty and Les Hiatt describe how Mulumbuk sings in the spirit language of the mermaids:51

The only sounds to which Mulumbuk attributes meaning are the initial “Aa” suggesting the ebb and flow of the tide, “andiya mara [an-diyama rra] (shellfish sowing)” – the magical words used by spirits of the dead to put flesh inside the diyama shells, “aa aa aa, ee ee ee” signifying the movements of the spirits as they rake the shells into localised beds and the final “Aa” expressing nostalgia amongst the spirits as they think of their living kinsfolk.52

David Maxwell also sang the words of the spirits inherited from his father, both in ceremonial performances and with popular bands accompanied by contemporary instrumentation in songs such as “An-barra Clan”. Stephanie’s version of the song has no spirit language in its verses and offers a more narrative perspective than the original kun-borrk. It is the chorus that imitates the mermaids’ song, using the sustained “Aa” vocable that is a prominent feature of the “Diyama” kun-borrk. This communicates nostalgia and sorrow for the spirits of the deceased. Vocables are units of non-translatable language that are commonly found across different song genres. Their usage can contribute to a sense of solidarity. As part of ritual language, they serve as a means of connection and spirituality.53

Linguist Murray Garde, in writing about the music of Western Arnhem Land, comments that the ability to compose songs, perform your father’s songs and receive songs from supernatural beings establishes authority over song repertoires and raises the status of songmen.54 In the case of the “Diyama” song, the use of vocables indicates communication with ancestral spirits, reinforcing Stephanie’s hereditary rights to sing “Diyama”.

The sustained “Aa” vocable is followed by calling out the name “Diyama”. Originally, Stephanie had called the song “Blyth River” and we sang this in the chorus at our performance at the Bak’bididi Festival. After her father’s death, she changed the chorus and the name of the song in a deliberate declaration of her inherited rights to the “Diyama” kun-borrk. Singing diyama in the chorus associates the song with the An-barra tradition of calling out the name of the shellfish, diyama, in order for the diyama ancestors to form themselves across the land.55

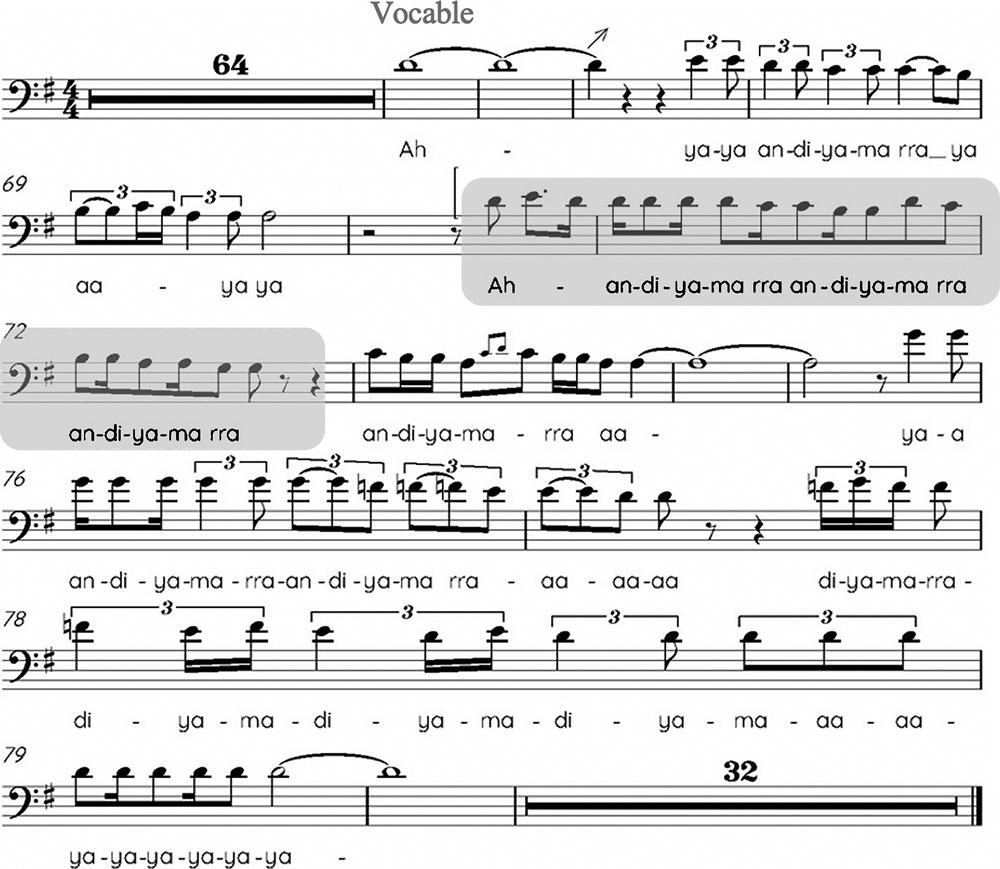

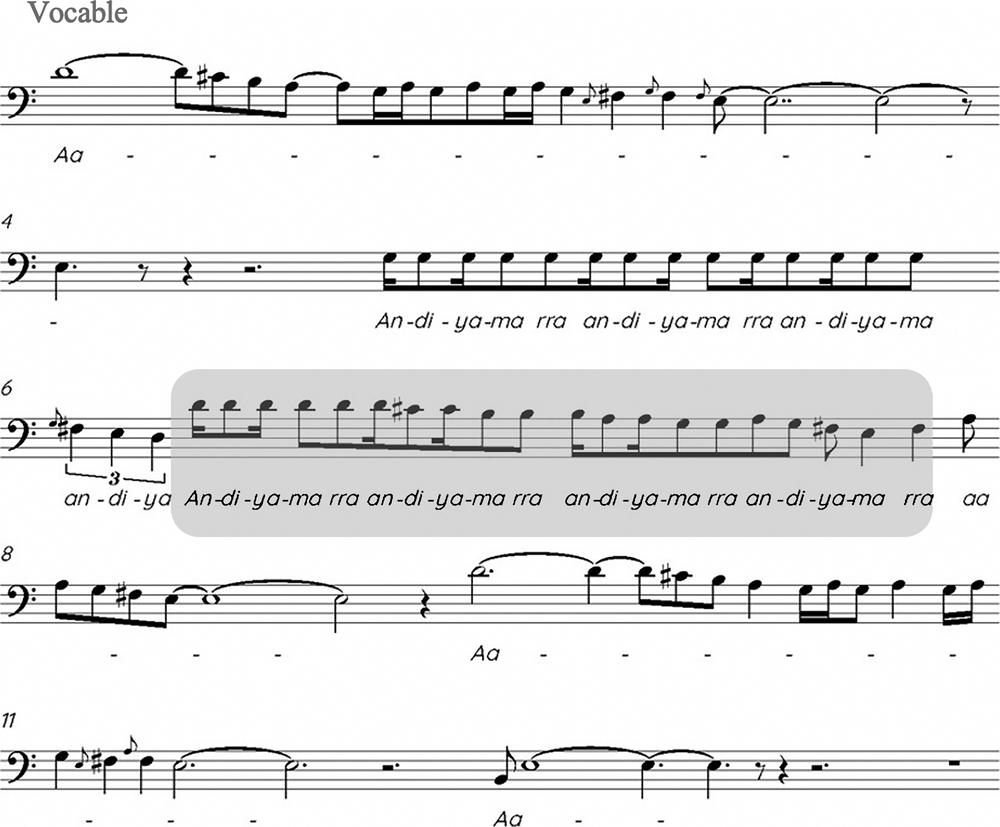

The synthesis of different iterations of this song are apparent in the kun-borrk that David sings over the song’s middle section and coda. Drawing upon his father’s interpretation of the mermaids’ song, he reinterprets its melodic phrasing. Figures 9.8 and 9.9 are transcriptions of father and son singing “Diyama” kun-borrk. In the part recorded for Stephanie’s song, even though David contributes his own slightly differentiated rhythms, he mimics his father’s rhythmic motif as highlighted in the transcriptions. They also show that both men start with the “Aa” declamatory vocable that calls out to the spirits and announces the singers’ presence. This intertextuality of songs within songs links three generations of singers as echoes of Mulumbuk’s song are heard in the iterations sung by his son and embedded in a recording made by his granddaughter.

When Stephanie’s father enters singing “Diyama” kun-borrk after the second chorus, the intermusicality apparent in this over-layering of two very different musical cultures creates an intensification increased by his vigorous singing. As David sings the song of the werrgepa (B: mermaids), we the listeners are asked to suspend our judgement and believe we are hearing their voices. His vocal mastery plays into the surprise audiences feel when they first hear a women’s band accompanying his expression of ancestral beings.

Figure 9.8 David’s vocals (highlighted) in the middle section of the Ripple Effect Band’s recording of “Diyama”. Transcription by Jodie Kell.

Production elements of the song reinforce this effect with long organ chords and backing vocalists intensifying the texture into the chorus. Throughout the song, Stephanie’s vocals have been doubled with a more natural track using reverb and a chorused track that suggests a spirit’s vocal quality. As the song draws to a close, the rhythmic pulse drops out, leaving only a sustained organ note and vocals singing the “Diyama” kun-borrk song. This change in rhythmic density and musical timbre creates an intensification that combines with the intermusicality of the incorporation of the kun-borrk song to evoke an emotional response, “taking it to another level”.56 Over the tremulous organ elongated through a slow delay and extended sustain, David Maxwell sings his last kun-borrk. His vocals convey a sense of longing for the past, for people and place, directly referencing the song recorded by his father Mulumbuk in 1960, but also marking his own place in the history of the “Diyama” song.

Figure 9.9 Mulumbuk’s original “Diyama” song recorded in 1960. Transcription by Jodie Kell, based on transcription by Aaron Corn. (Aaron Corn, “Dreamtime Wisdom, Modern-time Vision: Tradition and Innovation in the Popular Band Movement of Arnhem Land, Australia” (PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 2002), 125–26.)

Conclusion

Analysis of the “Diyama” song and its associated musical practices demonstrates how musical innovation enables song custodians to respond to changing contexts. We have examined how three generations of An-barra musicians have transformed the expression of ancestral spirits using new musical forms and utilising music technology. Stephanie’s grandfather, Mulumbuk, recorded a Western Arnhem Land kun-borrk. His sons incorporated his song into popular music forms in the Letterstick Band, influenced by the archival recording. In recent times, Stephanie and the members of the Ripple Effect Band are the first women to compose and sing their own version of the song, using popular music practice to negotiate agency as women musicians. Including Stephanie’s interpretation of the original kun-borrk in their recording gives authority to the new expression of the mermaid song by women musicians and affirms Stephanie’s An-barra heritage.

We have presented new knowledge that challenges the descriptions of cultural practices in archival recordings and written texts. Cindy’s mother told her version of the origins of the “Diyama” song as a narrative of a woman visited by mermaids in a dream who taught her the song and the dance associated with the diyama seashells. The possibility that a woman composed the well-known An-barra song will now coincide with the historical account recorded in the 1960s that places a man as the receiver of the dream. We have suggested that the status of women at the time prevented the recording of the women’s story and now Cindy feels strongly that it is time to document her mother’s story and rebalance the dominant narrative. By including both stories, we acknowledge archival theories that question the invariability of archival objects and historical accounts. This comes from an understanding that collective or shared memories are not fixed but are fluid and contingent on changing social structures that shape notions of identity.

The story of the “Diyama” song demonstrates how a historical recording can contribute to the sustaining of cultural practices. At the same time, its reinterpretation contains elements of innovation that both reflect and influence changing social structures and the construction of identity. In composing a new version of the song, performed by women musicians, Stephanie Maxwell James has rekindled interest in the origins of the song, opening up possibilities for the inclusion of women’s perspectives in the expression of An-barra culture.

References

Barwick, Linda. “Keepsakes and Surrogates: Hijacking Music Technology at Wadeye (Northwest Australia)”. In Music, Indigeneity, Digital Media, eds Thomas Hilder, Shzr Ee Tan and Henry Stobart. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2017: 156–75.

Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation. Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation Annual Report, 2016–2017. Maningrida 2017, accessed January 2021, https://www.bawinanga.cm/wp-content/uploads/sites/26/Bawinanga_Annual_Report_201617_Web.pdf.

Bracknell, Clint. “Connecting Indigenous Song Archives to Kin, Country and Language”. Journal of Colonialism & Colonial History 20, no. 2 (2019). DOI: 10.1353/cch.2019.0016.

Brown, Reuben. “The Role of Songs in Connecting the Living and the Dead: A Funeral Ceremony for Nakodjok in Western Arnhem Land”. In Circulating Cultures: Exchanges of Australian Indigenous Music, Dance and Media, ed. Amanda Harris. Canberra: ANU Press, 2014: 169–202.

Brown, Reuben, David Manmurulu, Jenny Manmurulu and Isabel O’Keeffe. “Dialogues with the Archives: Arrarrkpi Responses to Recordings as Part of the Living Song Tradition of Manyardi”. Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture 47, no. 3 (2018): 102–14.

Burns, Lori and Serge Lacasse. “Introduction”. In The Pop Palimpsest: Intertextuality in Recorded Popular Music, eds Lori Burns and Serge Lacasse. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018: 1–5.

Cook, Terry. “Evidence, Memory, Identity, and Community: Four Shifting Archival Paradigms”. Archival Science, 13, no. 2–3 (2012): 95–120.

Cook, Terry and Joan M. Schwartz. “Archives, Records and Power: From (Postmodern) Theory to (Archival) Performance”. Archival Science 2, (2002): 171–85.

Corn, Aaron. “Dreamtime Wisdom, Modern-time Vision: Tradition and Innovation in the Popular Band Movement of Arnhem Land, Australia”. PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 2002.

Corn, Aaron. “Burr-Gi Wargugu ngu-Ninya Rrawa: Expressions of Ancestry and Country in Songs by the Letterstick Band”. Musicology Australia 25, no. 1 (2002): 76–101.

Dadbalag, Mary. Interview by Cindy Jinmarabynana, 14 October 2017. Interview available as JK1-DY003-01 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY003.

Dadbalag, Mary. English interpretation of JK1-DY003-01 by Cindy Jinmarabynana, 14 October 2017. Interview available as JK1-DY003-03 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY003.

Djimarr, Kevin. Wurrurrumi Kun-Borrk: Songs from Western Arnhem Land, the Indigenous Music of Australia. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2008.

England, Crusoe Batara, Patrick Muchana Litchfield, Raymond Walanggay England and Margaret Carew. Gun-Ngaypa Rrawa: My Country. Batchelor, NT: Batchelor Press, 2014.

Faulkhead, Shannon, Livia Iacovino, Sue McKemmish and Kirsten Thorpe. “Australian Indigenous Knowledge and the Archives: Embracing Multiple Ways of Knowing and Keeping”. Archives and Manuscripts 38, no. 1 (2010): 27–50.

Garde, Murray. “The Language of Kun-borrk in Western Arnhem Land”. Musicology Australia 28, no. 1 (2005): 59–89.

Glasgow, Kathy. Burarra – Gun-Nartpa Dictionary: With English Finder List. Darwin: Summer Institute of Linguistics, Australian Aborigines and Islanders Branch, 1994.

Greene, Paul. “Introduction: Wired Sound and Sonic Culture”. In Wired for Sound: Engineering and Technologies in Sonic Culture, eds Paul Greene and Thomas Porcello. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2005: 1–22.

Hale, Ken. “Remarks on Creativity in Aboriginal Verse”. In Problems and Solutions: Occasional Essays in Musicology Presented to Alice M. Moyle, eds Jamie C. Kassler and Jill Stubington. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1984: 254–62.

Hiatt, Betty and Lester Hiatt. “Notes on Songs of Arnhem Land”. Canberra, ACT: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1966.

Hiatt, Betty and Lester Hiatt. Songs from Arnhem Land. Canberra, ACT: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1966.

Hiatt, Lester. Kinship and Conflict: A Study of an Aboriginal Community in Northern Arnhem Land. Canberra: Australian National University, 1965.

Hiatt, Lester and Kim McKenzie. Waiting for Harry: Tensions Behind the Scenes of a Ritual Event in Central Arnhem Land, Northern Territory [film]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 1980.

Hinton, Leanne. Havasupai Songs: A Linguistic Perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1984.

Indigenous Hip Hop Projects. Make it Through [music video], 2016. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T85KkTms-XE&ab_channel=IndigenousHipHopProjects, accessed 30 March 2021.

James, Stephanie Maxwell. “Diyama” [song], Wárrwarra [album] Ripple Effect Band, 2018. Sydney Conservatorium of Music. Independent Release, https://spoti.fi/3Da9mmW.

James, Stephanie Maxwell, Jodie Kell, Jolene Lawrence, Rona Lawrence, Patricia Gibson, Rachel Thomas and Tara Rostron. Interview by Spotify at Barunga Festival, 3 June 2018. Interview and transcript available as JK1-NG003 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/NG003.

Jinmarabynana, Cindy. Interview by Jodie Kell, 18 May 2020. Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY006 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY006.

Jinmarabynana, Cindy. Interview by Jodie Kell, 14 October 2017. Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY003-04 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY003.

Keen, Ian. Knowledge and Secrecy in an Aboriginal Religion. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994.

Kell, Jodie, Janet Marawarr, Deborah Wurrkidj and Jennifer Wurrkidj. “Jarracharra” recorded 2019, exhibited with Bábbarra Women’s Centre at Jarracharra exhibition, Australian Embassy, Paris, France, 2019–20, https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/J001, accessed 9 July 2021.

Ketelaar, Eric. “Archives as Spaces of Memory”. Journal of the Society of Archivists 29, no. 1 (2008): 9–27.

Letterstick Band. An-barra Clan [album]. Alice Springs: CAAMA Music, 2004. Available at https://caamamusic.com.au/caama-music-artists/letterstick-band/, accessed 14 March 2021.

Letterstick Band. Diyama [album]. Alice Springs: CAAMA Music, 2003. Available at https://caamamusic.com.au/caama-music-artists/letterstick-band/, accessed 14 March 2021.

Letterstick Band, Sunrize Band, Wildwater. Demurru Hits. Maningrida, NT: Maningrida Arts, 1995.

Marett, Allan. Songs, Dreamings, and Ghosts: The Wangga of North Australia. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2005.

Marett, Allan, Linda Barwick and Lysbeth Julie Ford. For the Sake of a Song: Wangga Songmen and Their Repertories. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2012.

Maxwell, David. Interview by Jodie Kell, 28 October 2017. Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY002 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY002.

Meehan, Betty. Shell Bed to Shell Midden. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1982.

Monson, Ingrid. Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Murphy, Allen, dir. Diyama: Soundtracks of Maningrida [film]. Alice Springs: Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA) Productions Pty Ltd, 2003.

O’Keeffe, Isabel. “Multilingual Manyardi/Kun-borrk: Manifestations of Multilingualism in the Manyardi/Kun-borrk Song Traditions of Western Arnhem Land”. PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 2016.

Ripple Effect Band. Wárrwarra [album]. Sydney: Ripple Effect Band, 2018. Available at https://www.ripple-effect-band.com, accessed 14 March 2021.

Ross, Margaret Clunies. “The Aesthetics and Politics of an Arnhem Land Ritual”. TDR: Drama Review 33, no. 4 (1989): 107–27.

Treloyn, Sally, Matthew Dembal Martin and Rona Goonginda Charles. “Moving Songs: Repatriating Audiovisual Recordings of Aboriginal Australian Dance and Song (Kimberley Region, Northwestern Australia)”. In The Oxford Handbook of Musical Repatriation, 1st edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Vaughn, Jill. “Meet the Remote Indigenous Community Where a Few Thousand People Use 15 Different Languages”. Conversation, 5 December 2018, accessed 9 July 2021. https://bit.ly/3uwDMuF.

Vogler, Dalton. “Is Pop Music Addicted to Hand Clapping?” Cue point, 31 August 2016, accessed 9 July 2021. https://bit.ly/3Q22sD0.

Wildwater. Rrawa [album]. Darwin, NT: Wildwater, 2007.

Wildwater. Bartpa [album]. Darwin, NT: Wildwater, 1996.

1 Stephanie Maxwell James, “Diyama” [song], recorded June 2018 on Wárrwarra (Ripple Effect Band), streaming audio accessed 9 July 2021, https://open.spotify.com/track/0YZ7618tj3ZZUNfztpC0cT?si=9f9a4194faeb44af.

2 Kun-borrk is a genre of individually owned songs accompanied by didjeridu and clapsticks, with associated public ceremonial dances. They are called manyardi in Mawng and Iwaidja and sometimes referred to as borrk. Unlike totemic songs of many other Arnhem Land song styles, kun-borrk focus on gossip and human emotion though they can also be concerned with ancestral spirits. They commonly use a haiku-like sparse lyrical poetry. See Murray Garde, “The Language of Kun-borrk in Western Arnhem Land”, Musicology Australia 28, no. 1 (2005), 59–89.

3 See Allan Marett, Songs, Dreamings, and Ghosts: The Wangga of North Australia (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2005); Reuben Brown, “The Role of Songs in Connecting the Living and the Dead: A Funeral Ceremony for Nakodjok in Western Arnhem Land”, in Circulating Cultures: Exchanges of Australian Indigenous Music, Dance and Media, ed. Amanda Harris (Canberra: ANU Press, 2014), 169–202.

4 The “Diyama” song appears as “Borg Song” performed by Mulumbug on the vinyl LP; Betty Hiatt and L.R. Hiatt, Songs from Arnhem Land (Canberra, ACT: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1966). The story appears in the accompanying booklet, “Notes on Songs of Arnhem Land”.

5 This study uses a range of languages from the Maningrida region, using the specific language relevant to the context. Words in language are followed by an English translation and the language group in brackets. The languages used are Burarra (B), Yolngu Matha (Y), Ndjébbana (Ndj) and Gun-nartpa (G).

6 Cindy Jinmarabynana, interview by Jodie Kell, Maningrida, 18 May 2020. (Available as JK1-DY006 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY006, 15:12.)

7 Jinmarabynana, interview, 2020. (Available as JK1-DY006 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY006, 00:05.)

8 Lester Hiatt, Kinship and Conflict: A Study of an Aboriginal Community in Northern Arnhem Land (Canberra: Australian National University, 1965), 27–28.

9 Jill Vaughn, “Meet the Remote Indigenous Community Where A Few Thousand People Use 15 Different Languages”, Conversation, 5 December 2018, accessed 9 July 2021, https://bit.ly/3uwDMuF.

10 Betty Meehan, Shell Bed to Shell Midden (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1982) 69–74.

11 Betty Hiatt and Lester Hiatt, “Notes on Songs of Arnhem Land”, companion booklet to disc (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1966), 13–14.

12 Cindy Jinmarabynana. Interview by Jodie Kell, 14 October 2017. (Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY003-04 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY003, 14:39.)

13 Crusoe Batara England et al., Gun-Ngaypa Rrawa : My Country (Batchelor, NT: Batchelor Press, 2014).

14 Margaret Clunies Ross, “The Aesthetics and Politics of an Arnhem Land Ritual”, TDR: Drama Review 33, no. 4 (1989), 124.

15 Betty Hiatt and Lester Hiatt spelled this name as Diama. Here, we are using the current orthography convention of Diyama.

16 Hiatt, Kinship and Conflict, 148–54.

17 Lester Hiatt and Kim McKenzie, Waiting for Harry (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Islander Studies, 1980).

18 Now known as the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS).

19 Betty and Lester Hiatt, Songs from Arnhem Land (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1966).

20 Hiatt and Hiatt, “Notes on Songs of Arnhem Land”, 14.

21 Jinmarabynana, interview, 2017. (Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY003-04 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY003, 06:11.) In this interview, Cindy interpreted the stories and words of Mary Dadbalag whom she had just interviewed.

22 Jinmarabynana, interview, 2020. (Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY006 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY006, 03:41.)

23 Jinmarabynana, interview, 2017. (Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY003-04 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY003, 08:43.)

24 See Allan Marett, Linda Barwick and Lysbeth Julie Ford, For the Sake of a Song: Wangga Songmen and Their Repertories (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2012); Marett, Songs, Dreamings, and Ghosts.

25 Marett, Songs, Dreamings, and Ghosts, 66.

26 Jinmarabynana, interview, 2020. (Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY006 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY006, 09:10.)

27 Eric Ketelaar, “Archives as Spaces of Memory”, Journal of the Society of Archivists 29, no. 1 (2008), 11.

28 Terry Cook, “Evidence, Memory, Identity, and Community: Four Shifting Archival Paradigms”, Archival Science 13 (2–3) (2012), 96.

29 Terry Cook and Joan Schwartz, “Archives, Records and Power: From (Postmodern) Theory to (Archival) Performance”, Archival Science 2 (2002), 172.

30 Jinmarabynana, interview, 2020. (Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY006 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY006, 00:10.)

31 Shannon Faulkhead, Livia Iacovino, Sue McKemmish and Kirsten Thorpe, “Australian Indigenous Knowledge and the Archives: Embracing Multiple Ways of Knowing and Keeping”, Archives and Manuscripts 38, no. 1 (2010), 29.

32 Ripple Effect Band, Wárrwarra. Sydney: Ripple Effect Band, 2018. Available at https://www.ripple-effect-band.com/music, accessed 14 March 2021. Recorded at Sydney Conservatorium of Music, produced by Paul Mac, Clint Bracknell and Jodie Kell, the four-track EP Wárrwarra was independently released in July 2018. It features four songs in four languages, Burarra, Kune, Ndjébbana and Na-kara.

33 Clint Bracknell, “Connecting Indigenous Song Archives to Kin, Country and Language”, Journal of Colonialism & Colonial History 20, no. 2 (2019), DOI: 10.1353/cch.2019.0016; Reuben Brown, David Manmurulu, Jenny Manmurulu and Isabel O’Keeffe, “Dialogues with the Archives: Arrarrkpi Responses to Recordings as Part of the Living Song Tradition of Manyardi”, Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture 47, no. 3 (2018), 102–14.

34 Sally Treloyn, Matthew Dembal Martin and Rona Goonginda Charles, “Moving Songs: Repatriating Audiovisual Recordings of Aboriginal Australian Dance and Song (Kimberley Region, Northwestern Australia)”, in The Oxford Handbook of Musical Repatriation, 1st edn. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 10.

35 Hiatt and Hiatt, “Notes on Songs of Arnhem Land”, 14.

36 Betty and Les Hiatt use the spelling manakay, but we use the orthography of Yolngu-matha language.

37 Hiatt and Hiatt, “Notes on Songs of Arnhem Land”, 14.

38 Aaron Corn, “Burr-Gi Wargugu ngu-Ninya Rrawa: Expressions of Ancestry and Country in Songs by the Letterstick Band”, Musicology Australia 25, no. 1 (2002), 166; Jinmarabynana, interview, 2020.

39 Paul Greene, “Introduction: Wired Sound and Sonic Culture”, in Wired for Sound: Engineering and Technologies in Sonic Culture, eds Paul D. Greene and Thomas Porcello (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2005), 3.

40 Linda Barwick, “Keepsakes and Surrogates: Hijacking Music Technology at Wadeye (Northwest Australia)”, in Music, Indigeneity, Digital Media, eds Thomas Hilder, Shzr Ee Tan and Henry Stobart (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2017), 156.

41 Barwick, “Keepsakes and Surrogates: Hijacking Music Technology at Wadeye (Northwest Australia)”, 157.

42 Lori Burns and Serge Lacasse, “Introduction”, in The Pop Palimpsest: Intertextuality in Recorded Popular Music, eds Lori Burns and Serge Lacasse (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018), 4.

43 Ken Hale, “Remarks on Creativity in Aboriginal Verse”, in Problems and Solutions: Occasional Essays in Musicology Presented to Alice M. Moyle, eds Jamie C. Kassler and Jill Stubington (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1984), 260.

44 Jinmarabynana, interview, 2020. (Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY006 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY006, 11:34.)

45 In the Maningrida region kinship systems, a person’s father’s brother is also called their “father”.

46 Stephanie Maxwell James et al. Interview by Spotify at Barunga Festival, 3 June 2018. (Interview and transcript available as JK1-NG003 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/NG003, 18:33.)

47 David Maxwell. Interview by Jodie Kell, 28 October 2017. (Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY002 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY002, 02:34.)

48 Corn, “Burr-Gi Wargugu ngu-Ninya Rrawa”, 76.

49 James, “Diyama”.

50 See Murray Garde, 2005; Kevin Djimarr, 2008; Reuben Brown, 2014; Isabel O’Keeffe, 2016.

51 Hiatt and Hiatt, “Notes on Songs of Arnhem Land”, 13–14.

52 Hiatt and Hiatt, “Notes on Songs of Arnhem Land”, 13.

53 Leanne Hinton, Havasupai Songs: A Linguistic Perspective (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1984).

54 Garde, “The Language of Kun-borrk in Western Arnhem Land”, 86.

55 Jinmarabynana, interview, 2017. (Audio interview and transcript available as JK1-DY003-04 at https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/JK1/items/DY003, 07:46.)

56 Ingrid Monson, Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 39.