6

“My Wretched Dragon Is Perplexed”: Scenes of Submission and Response

6 “My Wretched Dragon Is Perplexed”: Scenes of Submission and Response

“How, in the most general terms, do we respond to what we read and hear?” asks Bruce Gardiner at the beginning of his brilliant essay, “Christ’s Parable of the Sower: Intellectual Property Rights in Gossip and Testimony”, published in Literature and Aesthetics in 2018.1 Less courageous and capable than Bruce, I limit what follows to how we respond to what we read and hear in terms of instruction, grading and feedback; Bruce’s legendary responses to student papers provide the grist I will mill. Copious, trenchant and eloquent, with nary a cross-out or erasure, the page of handwritten commentary that met students on their papers’ returns indicate Bruce’s generosity, which takes seriously an encounter, or even a fight, between reading selves. This chapter reflects on these scenes of reading by framing them in terms of submission and response, where influence is both enacted and explicitly interrogated. I follow Bruce by taking seriously – but also fondly and playfully – the paratextual elements to and by which student essays are directed, returning to institutional documents that govern the production and reception of these essays, and I consider the question of pedagogical influence, whether that be, among other things, amanuentic, disciplinary, intellectual, maieutic, resisted or unrecognised.

This return is also, of course, a return to the position of a student, a position that is at once eternal and left behind as, for example, I graduated from being an Honours and PhD student in English at the University of Sydney to later take up a faculty position alongside whom Bruce dazzled undergraduates (and me) with virtuosic readings of Walt Whitman and Harriet Jacobs in an American Studies course I coordinated. To make these returns, I unearth a personal archive by re-reading several undergraduate essays written for Bruce and reproducing and re-attending to the feedback.2 I parse these encounters as models of instruction, care, and literary production against the subjects of the essays and in response to “Theaetetus’s Complaint, or Sadomasochism and Your Supervisor”, a “Select Bibliography” and an accompanying handout of excerpts, titled “UNDER INSTRUCTION”,3 which Bruce curated for first-year PhD students that supplemented a seminar on the supervisor–supervisee relationship.

* * *

That is the decisive difference; and yet, whatever kind of movement it may be which the New Testament writings introduced into phenomenal observation, the essential point is this: the deep subsurface layers, which were static for the observers of classical antiquity, began to move.4

Erich Auerbach, Mimesis

Before moving to my commentary on Bruce’s feedback and his discussion of testimony and gossip, I will offer an account of “Theaetetus’s Complaint” in order to trace the historical, generic, international and modal depth to Bruce’s pedagogy. Bruce’s selection from Plato’s Theaetetus finds Theaetetus complaining about the confusion and uncertainty he feels about knowledge and truth. Socrates asks him what he believes knowledge to be. Theaetetus struggles to provide a clear and satisfactory definition. Throughout the dialogue, Theaetetus expresses frustration with his inability to arrive at a solid understanding of knowledge. He grants that he has been taught different definitions by various philosophers, but none of them seem to capture fully its essence. He suggests that knowledge is perception, but Socrates points out the flaws in this idea; perception can be deceptive. Theaetetus bemoans “battling with shadows” (2) in his quest for understanding. Despite Theaetetus’ protests, Socrates encourages him to continue seeking knowledge and understanding.

As I re-read my student essays, it becomes apparent that I had something against allegory and analogy. (It is clear that I have gotten over whatever this was!) Nonetheless, it is tempting to make the connection, or even analogy, to Theaetetus struggling with the field of knowledge and its political economy – its production, its distribution, its affirmation – and my undergraduate years, where Bruce enters the scene. I majored in Biology and Psychology as well as Film Studies and English, dabbled in Mathematics until it became too difficult, failed at Sociology. Who or where or how – my undergraduate itinerary moans – to believe, to know? My discipline hopping betrays a similar epistemological dissatisfaction to Theaetetus’ but, nonetheless, I attempted to instrumentalise these hops to the advantage of my WAM (weighted average mark). I used a definition from my BIOL1001 textbook in an “evolution of language” essay for Bruce, even dictating the process of DNA transcription – an amanuensis pretending to maieusis – where the subject matter – it strikes me now, and likely then – wants to add factitious weight to the performance. I even pondered epigenetic heritability. The intended reader was not, however, bamboozled.

The section of Theaetetus that has informed much of my thinking here, and that explains my references to maieusis (and from there, perhaps by contrived visual similarity and Greekness, to amanuensis), follows next. Bruce’s selection offers an image of Socrates as a self-proclaimed midwife (and the son of a midwife), who explains that midwives have had children (experience required!) but are past child-bearing age (and so resemble Artemis, the childless patroness of birth). They are the best at detecting a pregnancy. With their “drugs and incantations” they can bring on the pains of childbirth, allay them, or even abort a pregnancy. Socrates notes further that midwives are the most skilled at pairing mates to produce the best offspring.

In a striking pairing with Plato, Gardiner’s “Theaetetus’s Complaint” begins with a 1972 newspaper cartoon from Bruce Petty that depicts Christopher Columbus getting kicked out of class for breaking the rules. “I don’t care where you go,” yells the teacher in the final cell, “so long as it’s as far away as possible!” (1). I once posted a picture of Columbus’ Tomb in the Seville Cathedral as what I captioned the “Tomb of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and past president of the American Studies Association, Christopher Columbus”. While Gardiner adduces across antiquity, Asia, Albion, the Americas and The Age, I merely hear America singing. The easy grab here (and I will take it) is to the method and wide-ranging archive of Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, and it is there that Benjamin declares “Literature submits to montage in the feuilleton”.5 I have gone on to a career in American Studies (a submission to montage, or the feuilleton, or both?), and while the New World existed long before its newness, and it is a long way from the Potomac to Acheron and from the Theatre of Dionysus to Broadway, the cursory, curious and continual responses I had and have to Bruce’s selections map onto the combination or montage of art, literature, critical reviews, and impressions of the city that irked writers such as Karl Krauss and Hermann Hesse when they looked at the kind of Reader’s Digest versions of the modern and modernist city created by the feuilleton sections of newspapers. An interdiscipline, a transdiscipline, even an antidiscipline, I have found American Studies demands a willingness to forge historical and geographical bridges, to interrogate and undo borders, to ford aesthetic and generic boundaries, and to attend to scenes of cultural and spiritual discord.

From Socrates the midwife, “Theaetetus’s Complaint” jumps two millennia to James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), where Bruce excerpts a Platonic dialogue between the Dean of Studies, a Jesuit, and Stephen Daedalus, the artist, a young man, on what is beautiful and good, over the practical work of lighting a fire. Remaining in Joyce’s homeland, William Butler Yeats invokes Irish mythology in his poem “Michael Robartes and the Dancer” (1918). Telling a story of a knight, a lady and a dragon (the wretched and perplexed dragon that titles this chapter) that he derives from images on an altar-piece, Robartes interprets the dragon as a figuration of the Dancer’s thoughts, her self-knowledge. He laments that there is something hidden in this figuration, which does not contain a transcriptive fidelity because it is not directed to a mirror but to and by a mythical beast. Robartes wishes her to turn to the mirror so that he himself “would grow wise” (4) in the apprehension of apprehension.

Reproduced on the same page as the poem by Yeats, Ezra Pound’s “Canto XIII” (1924) offers unique access to East Asia. As in Theaetetus, various interlocutors offer critiques and counterviews to the subject under discussion. Kung (Confucius) renders an image that reflects the reading list I will discuss below, an imaginary or fantastic private ledger, a pliant placeholder, where slots are set aside or given over to others to enter into a field of instruction and authority.

And even I can remember

A day when historians left blanks in their writings,

I mean for things they didn’t know,

But that time seems to be passing. (4)6

The final line vibrates with the functionalisation of contemporary pedagogy, where less and less time is given over to dialogue between student and teacher. The generous and transformative feedback that Bruce delivers resists this instrumentalisation. Even when the technology of submission and response changed, Bruce used a workaround. When online, soft-copy assessment submission was introduced, Bruce printed out each student essay, produced his customary handwritten feedback, scanned the handwritten pages, and uploaded them to each student. These responses, despite these extra layers of production and reproduction, become even more intimate and direct because they stand starkly against the software-generated, generic streamlining of efficiency-focused feedback. Bruce’s distinctive penmanship and what it pens reminds the student that in this pedagogical scene of submission and response they are led and judged by a human intelligence and not (only) an institutional machine of credentialing.

Before roving from north-eastern China to South Asia, with images of pedagogical inter-penetration in “A Teacher’s Prayer” from the Upanishads, we leap epochs and technologies to analogous images from Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), where Keyes (Edward G. Robinson) describes the job of an insurance claims officer to a dubious Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray):

To me a claims man is a surgeon, and that desk is an operating table, and those pencils are scalpels and bone chisels. And those papers are not just form and statistics and claims for compensation. They’re alive, they’re packed with drama, with twisted hopes and crooked dreams. A claims man, Walter, is a doctor and a bloodhound and a cop and a judge and a jury and a father confessor, all in one. (5)

In other words: claims man as Socratic midwife.

The movement from mythology, religion and antiquity is completed by a poem by Randall Jarrell, written in response to a letter sent to him from the English Office at the University of Texas, Austin, remonstrating that students cannot find him for office hour consultation.

Learn for yourself (if you are made to learn)

That you must haunt an hourless, nameless door

Before you find – not me, but anything. (5a)7

Plays provide scenes of the erotic charges of pedagogy. Eugene Ionesco’s La Leçon (1951) humorously depicts a bumbling, middle-aged male professor faced with a dull, lovely, rich female pupil, while David Mamet’s Oleanna (1992) finds the student schooling the professor in the changing norms and consequences of intimacy and solicitation in the institutional scene of pedagogy that is described in the selection from (Bruce’s future colleague) John Frow’s “Discipline and Discipleship”:

The master-disciple relation, whether in a focused or a diffuse form, is a mechanism – archaic and clumsy – for investing the process of transmission of knowledge with a productive intensity. It is a politically fraught mechanism; and it remains, directly or indirectly, the horizon of all our disciplinary transactions. (8)8

The allowance of a dialogue between the student and teacher is emphasised by the inclusion of Shoshana Felman’s Jacques Lacan and the Adventure of Insight. She claims that ignorance is “an integral part of the very structure of knowledge” (7) – it is not simply opposed to knowledge. Noting that Freud was taught by his patients, by their dreams, and by his dreams, she writes:

Unlike Hegelian philosophy, which believes it knows all there is to know; unlike Socratic (or contemporary post-Nietzschean philosophy), which believes it knows it does not know – literature, for its part, knows it knows but does not know the meaning of its knowledge, does not know what it knows. (7, emphasis original.)9

Rather than hiding among the discourses of other disciplines, separated by degree award programs, learning spaces, and their different means of making claims about the world, Bruce’s feedback becomes not only Socratic but, I have come to see, a catalyst that transforms the student essay into a kind of parabasis. Often used in ancient Greek drama, where the chorus or one of the actors steps out of character to address the audience directly, parabasis is used to convey the playwright’s personal opinions or to remark on current events. It offers direct commentary to the audience, and it is up to the audience whether they simply leave it at that, use it to inform their understanding of the play in which the parabasis takes place, or remove it from its contiguous context and place it against, for example, other works or parabases by the playwright or works or parabases by other playwrights.

* * *

Pedagogic side of this undertaking: “To educate the image-making medium within us, raising it to a stereoscopic and dimensional seeing into the depths of historical shadows.” The words are Rudolf Borchardt’s in Epilegomena zu Dante, vol. 1 (Berlin, 1923), pp. 56–57.10

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project.

“I define gossip and testimony as follows,” declares Bruce in “Christ’s Parable of the Sower”:

If a message would bear the same interest for those party to it had another sender sent it, then that message is the basic unit of gossip. If it could not bear the same interest for those party to it had another sent it, then it is the basic unit of testimony. The salient distinction is whether one sender serves as well as another. If one does, then the message betokens the representative standing of the sender, but if one does not, it betokens the difference of that sender from all others. … Gossip generates and sustains our indiscriminate sociability, testimony our irreducible autonomy.11

Bruce’s feedback functions as testimony – it would not bear the same value for the student had another scholar sent it. But this value is only obvious after the student reads Bruce’s feedback (at least the first time). While one could easily imagine a rote response that uses standard phrases (phrases that may even await the grader in a software program ready to be dragged-and-dropped into a comment box) and judges submissions on criteria plainly articulated by a rubric (to which the student may direct their essay), and can thus be categorised as gossip, one grader serving as well as another, this image is supplanted by Bruce’s singular response, a singularity that exists at the level of form and content, and the materiality of the message. The effortless effort of Bruce’s handwriting – sometimes difficult to discern – prompts more: more reading, more ideas, more thought, more time.

To return to this chapter’s opening query, how, then, do we respond to guidance, feedback and criticism? To begin at an end, if we exclude the page number, journal title, issue number and year of publication for Bruce’s “Christ’s Parable of the Sower”, the final two words of the document, in a footnote Bruce uses to “thank all who offered me such excellent advice when I asked them for it”, are my name.12 I must admit my surprise at coming across this paratextual cameo as I re-read Bruce’s essay despite reading drafts and offering whatever feedback I could, knowing Bruce’s propriety in all matters (my name is the last because of Bruce’s alphabetical ordering of influence), and, most pertinently, reading the finished article in this very form soon after its publication.

It is precisely these moments of overlooking and all-too-humanness that Bruce makes apparent and delights in, what he turns over in his essay, working through the different versions of the parable across the Gospels, where Christ “wonders … how some of us can ignore or forget the very words that others recognise as of world transforming import”.13 Analysing Christ’s parable in terms of intellectual property, Bruce draws a distinction between two kinds of listener, “those who take the message to heart and those who do not” – that is, those who cast or broadcast the message as testimony or as gossip.14 This distinction seems most apposite for Festschriften, where testimony – Bruce’s “Christ’s Parable of the Sower” and the reproductions of “Theaetetus’s Complaint” – and gossip – my “behind-the-scenes” and “after-the-fact” commentary – mingle as the influence of the honoured scholar is celebrated. The response to feedback, it seems, is not linear, but follows organic or peripatetic patterns of development, dormancy and regression, where, in line with Felman’s argument, forgetting and ignorance nonetheless provide a shape and structure for knowledge.

* * *

Even a private xerographic copy can be a primary record if a person who used it becomes a subject of historical inquiry – or, of course, if one’s topic is the history of reproductions.15

G. Thomas Tanselle, Literature and Artifacts.

The generous reader does not necessarily award high marks. Indeed, when I look at my English Honours record, the mark I received for Bruce’s “The Learned and the Literary” seminar was the lowest of my six grades that year. High marks are what the student seeks in their submissions, but Bruce’s responses, his reading, demonstrate that those high marks are desired merely “among other things”, things that his responses bring to light or – to begin the archival exploration – midwife, like Socrates, or germinate, like Christ as the Sower, for the student.

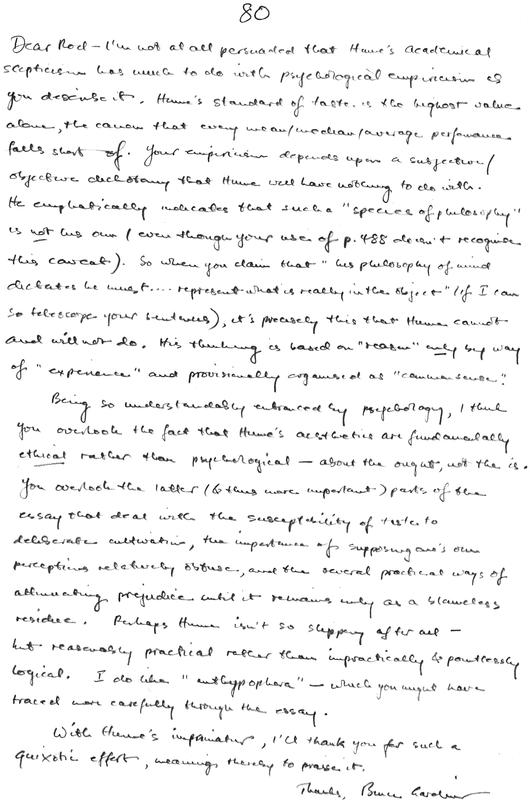

It is rather bracing to re-read my essay on “Hume’s ‘Of the Standard of Taste’” and the judgement it was given. Reproducing here Bruce’s least impressed feedback returns me to a position somewhere between amanuensis and maieusis. Where the former refers to dictation or transcription and thus some mimetic capacity to record and perhaps disseminate the thoughts, words and ideas of another person, the latter bespeaks a vital hand in the process of creation and reproduction. Rather than regurgitating whatever I thought I might have gleaned from lectures and tutorial discussion, I attempted to demonstrate originality by adducing an unexpected regime of knowledge. This more creative or productive practice is described by Bruce as my “being so understandably entranced by psychology” (see Figure 6.1). This entrancement fails not so much because it was my own entrancement with the discipline – I abandoned Psychology in favour of English when deciding upon which Honours program to take after completing a BSc and a BA – but, rather, in my attempt to entrance the reader by venturing what I assumed was far afield. Surely, I suspect I reasoned to myself, references to p-values and the Central Limit Theorem will convince Dr Gardiner that I am offering something new and superior about Hume’s standard – or obfuscate my incomprehension.16 But “Hume’s aesthetics are fundamentally ethical rather than psychological – about the ought, not the is”. My contrived punning on standard reaps shrivelled fruit. “With Hume’s imprimatur, I’ll thank you for such a quixotic effort, meaning thereby to praise it” (see Figure 6.1). I fundamentally mistook Hume’s argument. Or at least Dr Gardiner said so, and I believe him, still.

The next encounter is that between Bruce and an essay I titled grandiloquently, “Darwin and Müller and the meaning of life”. Again, I turned away from English and to the history and philosophy of science, though at least here the two subjects of inquiry justify adducing this field. And I can re-invoke the practice and figure of amanuensis because it appears in the production of Charles Darwin’s work, as he often relied on amanuenses throughout his life of chronic ill health. He employed several people to assist him in transcribing his work, quite often his wife, Emma, and his two daughters. Darwin’s use of amanuenses indicates that it is never a matter of simple transcription and perfect reproduction.

Utterly devoted to his interests, she [Emma Darwin] created and preserved the orderly, quiet, entirely domestic environment Darwin desperately craved for his work and health … Emma was ready to read aloud to him during his periods of rest on the indispensable sofa, write letters at his dictation … She helped proof the Origin; transcribed many of Darwin’s notes, manuscripts, and letters; and, along with their children and servants, dutifully watched over his experiments.17

These relations of wife, mother and offspring reveal that amanuensis is not merely a mimetic copy of the thoughts and words divorced from the social scene of writing and reading; the practice and very presence of the amanuensis brings – even births – the thoughts and words into the world.

Figure 6.3 Feedback from Gardiner on my student essay titled “Of what consequence is a theory of the evolution of language to a theory of the nature of language?” (2003).

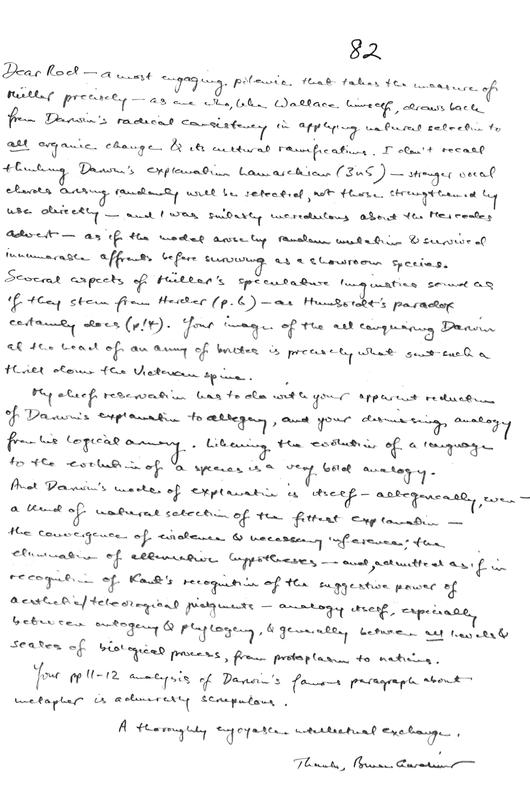

Similarly, maieusis is important in the work of Friedrich Max Müller, the philologist and Orientalist whom we read historiographically for his contributions to the study of linguistics and to the history of religion at a time when Darwin’s work was being published, and for Müller’s critiques of Darwin’s theories. Müller believed that the study of language was a key to understanding the development of human culture and thought. He argued that the emergence of new languages and new forms of expression was a process of maieusis, in which new ideas and concepts were brought into the world through dialogue and mixture, but without a governing mechanism such as natural selection. I garner this summary from reading my essay, and I stick with it, because Bruce says I “take the measure of Müller precisely” (see Figure 6.2).

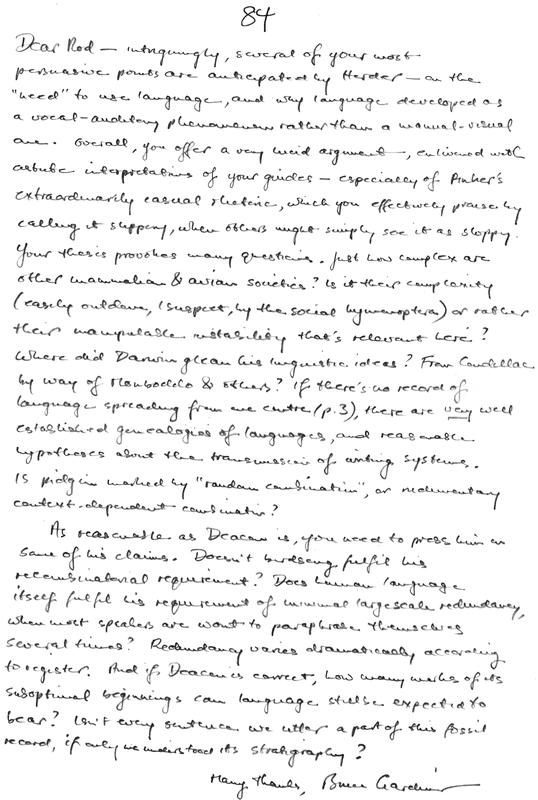

In Bruce’s response to an essay, “Of what consequence is a theory of the evolution of language to a theory of the nature of language?” one might infer the suggestion that I cribbed Herder: “Dear Rod, intriguingly, several of your most persuasive points are anticipated by Herder” (see Figure 6.3). But I was not informed enough to know to pilfer Herder’s writings, so the possibly inflammatory suggestion instead becomes high praise once I worked out Herder’s status and placed the suggestion within the gestalt: “Overall, you offer a very lucid argument, enlivened with astute interpretations of your guides” (see Figure 6.3). While I suggest that Bruce’s feedback functions in the realm of testimony, it has the intellectually enlivening effect of turning the student’s work into gossip. The student wishes to distinguish themselves from their peers, chasing credit and distinction, by demonstrating, among other things, a novel approach and original mentation, but Bruce places the student and their work into a centuries- and even millennia-long intellectual discourse, which, like the matrimonial, convalescent, loving and parturitional scenes of Darwin’s work, has a necessarily social dimension, full of coincidence, history, accommodation, jealousy, rivalry and ignorance. The student comes to operate among Herder, Müller, Darwin and Hume; each sender serves as well as another. But rather than a diminution of some notion of individuality or the realisation of some unique potential, the student is lofted, “sharing intellectual property that is everyone’s generally, no one’s particularly, and anyone’s representatively”.18

While the becoming-gossip of student submissions generated by Bruce’s responses indicates that amanuensis is always maieutic, amanuentic tics endure. In years past, I would emulate Bruce’s page of feedback with my own word-processed response. While my ugly penmanship was one reason for choosing to type and print my feedback instead of writing it directly on the reverse of the final page, the main reason was to allow myself the best chance of producing a pellucid comment; I could delete and modify as much as I wanted as I approached the Gardinerian ideal of my own undergraduate years. I have frequent recourse to “My chief reservation …” (see Figure 6.2) in my own grading. I also sign off “Thanks” or “Many thanks”, the more emphatic emerging in response to when I suspect the submitter has given the piece of writing a lot of time and thought, no matter the final, numerical grade. I have adopted Bruce’s “Dear ___,” in my email correspondence with students, and I smile when it is adopted by my correspondents.

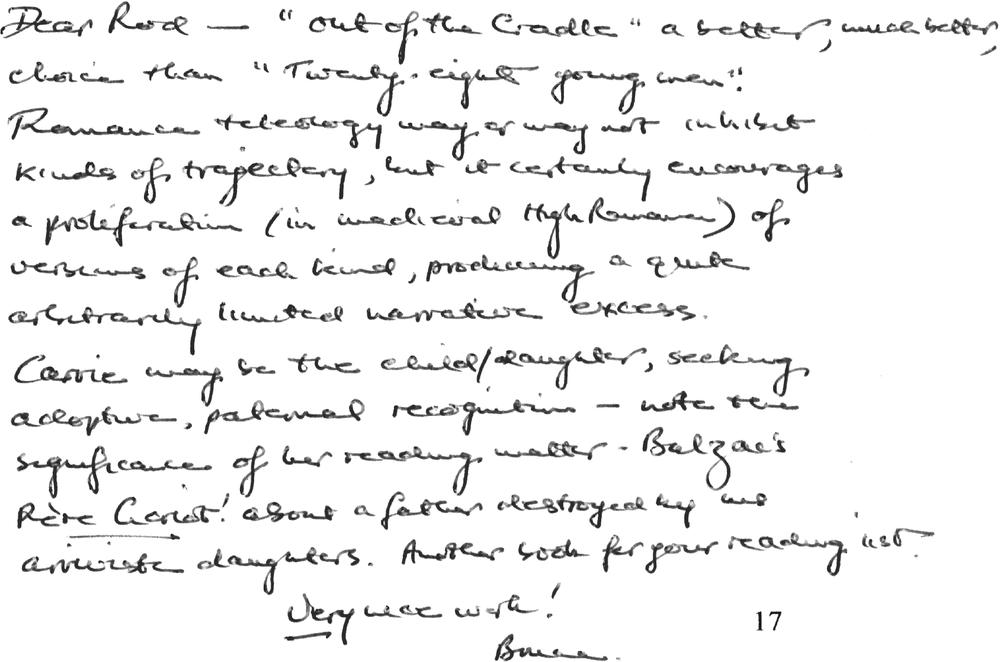

Bruce delivered the courteously condensed comment of Figure 6.4 when acting as second marker for a seminar called “American Romance”. Shorter but not attenuated, it manages to capture the implications of the argument, correct or guide them, draw in medieval High Romance, offer a psychoanalytic interpretation, and add another book for my reading list (see Figure 6.4).

Figure 6.4 Feedback from Gardiner on my student essay titled “‘The Bygone Heroine of Romance’: Sister Carrie and The Awakening” (2004).

What, finally, is this reading list? A powerful, ongoing placeholder – recall Kung’s “day when historians left blanks in their writings” from the selection from Ezra Pound – it contains books read and not read, and, most importantly in this context, books read by others. It is also a list to which Bruce’s feedback gives the student entrée, admitting them into this realm where their work converses with that of others, a kind of intellectual gossip, akin to the seeds scattered in Christ’s Parable of the Sower. While the different probabilities, imperatives and motivations of the brothers for trying to germinate the seeds in their different situations are instructive, here it is merely presenting the seeds themselves that is most significant. Once the student is made aware of them, it takes a strong act of wilful, antisocial forgetting to undo or refuse the introduction. But this is not to say that the student and intellectual conversation is only one of gossip. Its ongoingness betokens a temporality that asks, even demands, that the student testify, that they exercise their intelligence for, to and against the reading list to which Bruce admits.

In the end, I take succour that the handout that accompanies “Theaetetus’s Complaint, or Sadomasochism and Your Supervisor” is given the temporally indeterminate or at least ongoing title, “UNDER INSTRUCTION”. I hope it is clear that Bruce has remained an important interlocutor and guide, and that this chapter has added some small measure of testimony to Bruce’s influence. It is precisely his conversance with a wide domain of knowledge production, comfortable enough in many disciplines to articulate his discomfort with many of their claims, which has continued to allow me to pose questions in my own scholarship, for these questions to be answered (both insufficiently and sufficiently), to be ignored for stretches of time, to be worried, to be repressed, to be ever-present.

Bibliography

Auerbach, Erich. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Trans. Willard R. Trask. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Trans. Howard Eiland, and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Felman, Shoshana. Jacques Lacan and the Adventure of Insight. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Frow, John. Discipline and discipleship. Textual Practice, 2(3), (1988). 307–323.

ttps://doi.org/10.1080/09502368808582038.

Gardiner, Bruce. “UNDER INSTRUCTION.” Ten-page photocopied document, University of Sydney. Received by the author, March 2005.

Gardiner, Bruce. “Christ’s Parable of the Sower: Intellectual Property Rights in Gossip and Testimony.” Literature & Aesthetics 28 (2018): 193–220.

Jarrell, Randall. “Office Hours 10-11”, Complete Poems, (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1969).

Pound, Ezra. Canto XIII, The Cantos of Ezra Pound, New York: New Directions, 1972.

Richards, Evelleen. Darwin and the Making of Sexual Selection. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Tanselle, G. Thomas. Literature and Artifacts. Charlottesville: Bibliographic Society of the University of Virginia, 1998.

1 Bruce Gardiner, “Christ’s Parable of the Sower: Intellectual Property Rights in Gossip and Testimony”, Literature & Aesthetics 28 (2018): 193.

2 I also adhere to the word limit of those essays.

3 Bruce Gardiner, “UNDER INSTRUCTION”, ten-page photocopied document, University of Sydney, received by the author, March 2005. Future references to this document are to this manuscript, and will be cited parenthetically by page number, unless quoted directly, in which case the reference to the original source is also provided.

4 Erich Auerbach, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, trans. Willard R. Trask (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003), 45.

5 Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 13.

6 Ezra Pound, Canto XIII, The Cantos of Ezra Pound, (New York: New Directions, 1972), 60.

7 Randall Jarrell, “Office Hours 10-11”, Complete Poems, (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1969), 463.

8 John Frow, “Discipline and discipleship”, Textual Practice, 2(3), 1988. 321.

9 Shoshana Felman, Jacques Lacan and the Adventure of Insight. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987), 92.

10 Benjamin, Walter. “From N [On the Theory of Knowledge, Theory of Progress]”, The Arcades Project, 458.

11 Gardiner, “Christ’s Parable of the Sower”, 194.

12 Gardiner, “Christ’s Parable of the Sower”, 222, fn 72. Literature and Aesthetics does not require a bibliography; footnotes suffice.

13 Gardiner, “Christ’s Parable of the Sower”, 193.

14 Gardiner, “Christ’s Parable of the Sower”, 194.

15 G. Thomas Tanselle, Literature and Artifacts (Charlottesville: Bibliographic Society of the University of Virginia, 1998), 100.

16 Revising this chapter, I remember that I have “developed”, in one of my recent lectures, a “Central Limit Theorem of Humour”.

17 Evelleen Richards, Darwin and the Making of Sexual Selection (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 47.

18 Gardiner, “Christ’s Parable of the Sower”, 194.