Chapter 13

Participatory action research in an arts transition program

Faculty of Arts

Background and context

The transition process for students commencing an undergraduate arts degree at the University of Sydney can be impersonal and overwhelming. The university has total student enrolments of 45,000 and a staff of over 6,500. The Faculty of Arts is one of the largest in Australia, with more than 7000 students, almost 6000 of whom are enrolled at the undergraduate level.

‘Arts students’ are defined not by the subjects they study, but by the degree program they enroll in. When students enroll at the University of Sydney, they enroll in the faculty that offers the degree program they wish to complete. This faculty is responsible for them throughout their candidature—for the administration of their degree program, for their retention and progression, for their completion of the requirements of the degree and for their overall learning experience.

The Arts Faculty prides itself on the outstanding breadth of choice we offer our students when it comes to selecting subjects and majors both within and beyond the faculty, and on the many opportunities we provide for interdisciplinary learning. These features are also highly valued by students. In feedback from both current students and recent graduates, respondents often mention the range of choice available as one of the most positive aspects of their degree in arts.

However, this flexibility does not come without a price. The Bachelor of Arts, in which over half of our undergraduates are enrolled, has no core subjects at all, and so provides candidates with no shared learning experience. Students in our fourteen other degree programs may share core units in one subject area, but have even more choice than Bachelor of Arts students when it comes to their other subject areas, and often complete majors offered by one or even two other faculties.

It is hardly surprising, in this context, that our students have little natural sense of belonging to a cohort, nor a strong sense of identity with their degree program or with the faculty. Focus groups held in 2001 indicated that even students in relatively small arts degree programs such as the Bachelor of Arts (Informatics) and the Bachelor of Social Sciences lacked a sense of belonging and felt out of touch with others in the same program. In follow-up focus groups conducted in 2002, we asked students to describe their experiences in the first few weeks of their first year. The vocabulary they used left us in no doubt about the depth and significance of their feelings: ‘Nightmare’, ‘LOST LOST LOST’, ‘stressed out’, ‘awkward’, ‘isolating’, ‘impersonal’, ‘fearful’, ‘scary’, ‘confusing’, ‘extremely sucky, hellish, and bollocks’. (Jarkey, 2004, p. 188). Even after studying in the faculty for a year or more, many students report that they are still quite overwhelmed and unsure about how to get the support they need.

The scholarly literature on the tertiary transition experience has much to say about the issues we face. Academic and social integration are well recognised as crucial elements in ensuring a smooth transition to tertiary learning (Beasley & Pearson, 1999; Peat, Dalziel & Grant, 2001; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991). This integration can, to a certain extent at least, take place naturally in smaller faculties, and in those in which students have a higher number of ‘core’ or compulsory subjects and a narrower range of choice. 142Students meet each other frequently in classes and share many common learning experiences. They have similar timetables with common free time, which they can spend together in shared recreational spaces. In this environment, most soon develop friendships and supportive academic and social networks. Our focus groups revealed that this was certainly not happening naturally for arts students at Sydney—not surprising given the very different context they found themselves in during their first year.

Transition and mentoring programs have been found to assist by integrating new students with the learning community and engaging them with the university. McInnis, James and Hartley (2000, p. 53) point out that these programs are important for all students, but particularly those who experience problems. The research of these authors (2000, p. 55) further reveals the value of developing different approaches in addressing the varying needs of students depending on their area of study. What works in the context of one faculty may not be effective in another.

For these reasons, in 2002, we began to organise a program to support the first first year experience in arts, and to help our commencing students value and benefit from the opportunities that come hand-in-hand with the potential challenges of studying in the context of our faculty. This program invites senior student volunteers to help welcome first years to the faculty at enrolment time, to participate in organising ‘Arty Starty Day’, a transition workshop for initial orientation and networking, and to provide ongoing support and encouragement through a peer-mentoring program.

Aim of the investigation

The investigation reported in this chapter is an ongoing one; it commenced, as the program did, in 2002 and has since become an integral part of the program itself. This investigation was initially motivated by the fact that, although our students were telling us that they needed a sense of identity and belonging in our faculty, and the literature was advising us that a mentoring program would help, we did not have a clear sense of just what such a program would look like if it were to successfully contribute to meeting our students’ needs.

Thus, the central question for our investigation was, and continues to be: ‘What are the key features of a mentoring program that will help first year students to develop a sense of identity and belonging in the context of our faculty?’ The aim of the investigation is to use the understandings we gain in response to this question to develop a mentoring program that really does make a difference to our first year students’ sense of identity and belonging, and so, ultimately, to the quality of their learning experience in their arts degree program at the University of Sydney.

The Arts Network Mentoring Program is just one part of a suite of initiatives we have developed in the faculty over the last few years to try to address our students’ needs. However, the outcomes of our investigation to date suggest that it is rapidly becoming a key element in a positive transition experience for our students, and their sense of being valued members of the faculty learning community.

Theoretical approaches that inform the investigation

The fundamental theoretical approach we have come to adopt to inform our investigation is that of critical social theory, an approach that focuses on integrating theoretical understandings with practical outcomes involving social change. Within this broad domain, our approach can be characterised as ‘critical educational science’, 143which Carr and Kemmis (1986, p. 155) describe as ‘a form of research which is not research about education but research for education’.

Our research methodology is participatory action research. The rationale for adopting this methodology is threefold. Firstly, firmly in the tradition of critical social theory, action research is not only about creating understanding and knowledge, it is also about creating change (Seymour-Rolls & Hughes, 1995; Hughes, 2004). This is precisely our goal: first to understand how to foster a sense of identity and belonging amongst our students, and then to actually do so. Secondly, and again in the tradition of critical theory, when action research is participatory it is about negotiating processes and sharing decision making in ways that are empowering to all those involved. We cannot, and would not wish to impose a ready-made, faculty identity on our students; what we can do is foster a context that invites them to be active participants in creating a shared sense of identity. Our third rationale for the methodology we have adopted is that participatory action research addresses shared concerns by drawing on the collective resources of all stakeholders in a collaborative process. This process involves four, interdependent, cyclical elements: planning, acting, observing and reflecting (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1988). It is this action research process, and the generous involvement of our students and staff in it, that we see as crucial to the outcome of positive change in our program, in our faculty, and in the transition experience of our students.

It is important to acknowledge limitations on the extent to which we can realise the ideals of our theoretical approach and research methodology in the context of our program. As pointed out by Ospina, Dodge, Godsoe, Minieri, Reza & Schall (2004, p. 48):

Just as the ideal of democracy animates political life but is often not fully realised, the democratic aspirations behind action research are much harder to achieve in practice than in theory.

While our student participants are actively involved in most key decisions in the program, staff participants do retain ultimate power over decisions related to significant financial commitment and to university policy. Furthermore, we would not wish to pretend that staff participants manage, in all other respects, to overcome the deeply rooted power imbalance embedded in our interactions with students, in particular in relation to language and discourse (Foucault, 1980). Nevertheless, we take heart in the vision of Paulo Freire (1970):

The core of Freire’s approach is to realise the liberating potential of reflection plus action. The combination of theory and practice in a single process (praxis) has potential to overcome the oppressive structures that can result from the alienating duality of mind and body (theory and practice, reflection and action). This is a powerful idea for cultural change. (Hughes, 2004)

Methods of investigation: The participatory action research cycle

The cycle of investigation – planning, acting, observing and reflecting – is an integrated and continuous one. Nevertheless, in some sense we think of the cycle as ‘beginning afresh’ in Semester Two each year, when we invite students who participated in the program in Semester One to join general and academic staff to reflect on what we have learnt from the previous year’s program and to plan for the following one. Those students who join staff in this reflection and planning session are primarily either first 144year participants who are intending to become mentors, or previous mentors who are looking forward to participating as mentors again.

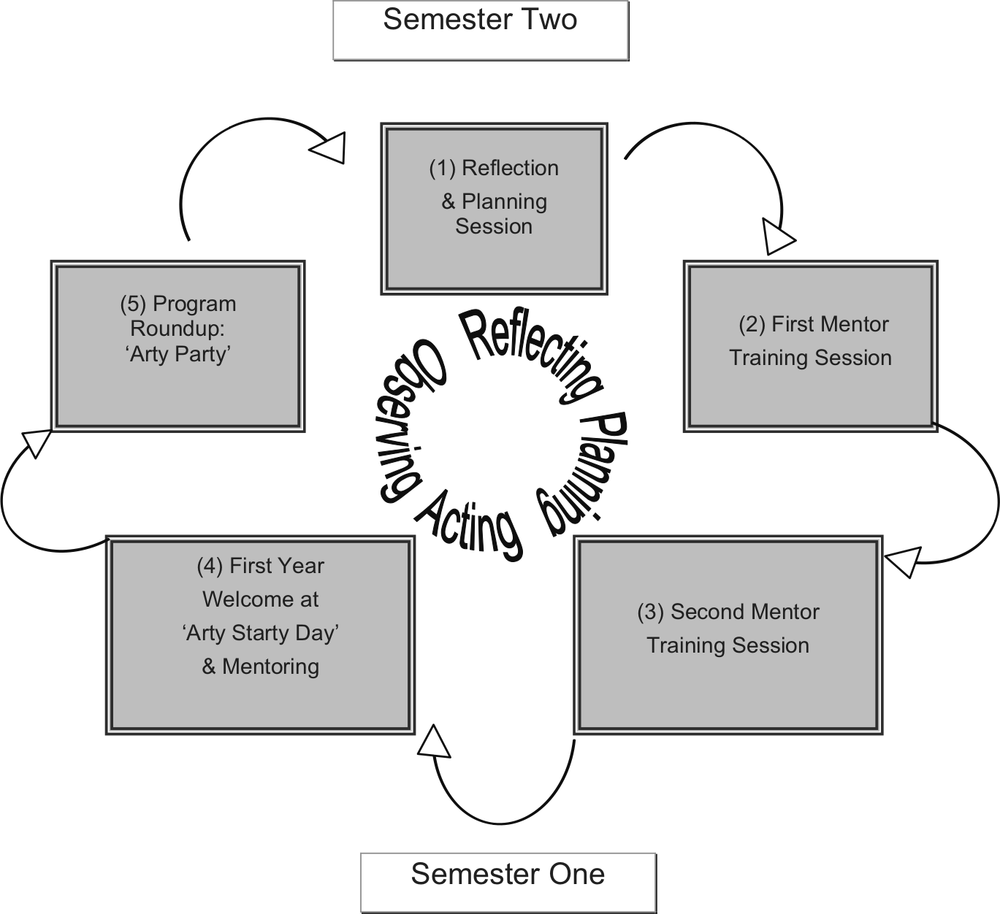

The data we use to facilitate this planning come from two sources. First are the observations we have collected from the previous cycle. Second are our own reflections on these observations and on our own experiences, from our current perspective of temporal distance from the experiences and actions observed, and from our current role as planners for the next cycle. This stage of the cycle is represented as (1) in Figure 13.1.

Figure 13.1. The participatory action research cycle

The stages of reflecting and planning continue as the ‘acting’ stage of the cycle begins, with the first mentor training session at the end of Semester Two - represented as (2) in Figure 13.1. We take this opportunity to ensure that new participants are aware of the changes and innovations we have made to the program as a result of the input of past participants, and of any further changes and innovations we are considering for this iteration. Of course, we invite the new participants to contribute to refining and to realising these innovations. This is particularly important, as it fosters a sense of ownership and involvement in the cyclical action research process with all members of 145the new team, not only those who were able to attend the initial reflection and planning session.

Understandably, those new to the team often do not contribute quite as freely as the more established members in this first face-to-face encounter together. However, many soon find their voice in our online discussion board, through which we keep in virtual contact over the summer break between the first training session and the second. The fact that mentors themselves often initiate discussion threads on topics related to program planning and evaluation tells us that they feel that their input is genuinely valued. In the 2005-2006 program, for example, a ‘Cool Activities’ thread was launched by a new mentor the day after our first training session, and elicited twenty one postings from ten contributors, seven of whom were new mentors.

The cycle progresses very clearly from a focus on planning to a focus on acting, as we meet face-to-face again at the second mentor training session (shown as (3) in Figure 13.1) to make final preparations for welcoming the new first year students on ‘Arty Starty Day’ at the beginning of Semester One and for mentoring them over their first few crucial weeks at university (shown as (4)). Throughout these acting stages, we continue to observe in a variety of ways. At face-to-face events such as the training and welcome sessions we use brief feedback surveys, and complement these with informal, post-event ‘debriefings’. Our online discussion board, in which the first years as well as the mentors now have a voice, continues to be a fertile shared ground for ongoing observation and reflection. And the official ‘round-up’ to our program—‘Arty Party’ (represented as (5) in Figure 13.1)—along with longer online surveys administered later in the semester, are chances to elicit responses to the program as a whole and to its value in the broader context of the transition experience.

Before the cycle ‘begins’ again in Semester Two, the feedback we have received from participating mentors and first years is further contextualised by input from faculty staff who have participated in various program events, and from colleagues in other faculties and at other institutions who are responsible for similar programs. Finally, the scholarly literature continues to be another valuable ‘lens’ through which further observations can be made and understandings facilitated (Brookfield, 1995, pp. 36-39).

Findings of the investigation and resultant changes to the program

The basic findings outlined here may well have been revealed to some extent through an alternative research methodology. However, the level of our understanding of their significance to our student participants, and the nature of the changes made as a result, are shown below to be attributable to the participation of all stakeholders in the research process and its outcomes.

The importance of relationships

When asked to reflect at the end of the program on the aspect that they find most valuable, around two thirds of first years (66% in 2006) and an even higher proportion of mentors (70% in 2006) identify making friends with others in their course and building and participating in supportive networks as key aspects for them. The following is typical of the kind of comments we often receive from first years:

[The most valuable part of the program was] meeting people who are doing the same course as me. We are all still really good friends and we see each other all the time. It was a good chance (and one of the few opportunities) 146to spend a prolonged period of time getting to know people in your course. (Online survey of First Years, June, 2006)

The fact that first year students build social networks through mentoring programs, and the fact that they value these networks highly, came as no surprise to us; this was precisely what the literature had led us to expect (e.g., Peat, Dalziel & Grant, 2001) and was one of our strongest motivations for establishing the program in the first place. However, there were two findings about the importance of relationships that we had not anticipated.

The first of these was the extent to which not only first years, but also mentors found the program helped them expand their own networks and sense of identity within the faculty:

[The most valuable part of the program was] the opportunity to meet so many other great mentors and mentees – it makes you feel like you are significant and play an important role in the Arts Faculty. The Arts Faculty is so huge, sometimes it can feel quite anonymous: mentoring makes the faculty seem much smaller and more friendly. (Online survey of Mentors, June, 2006)

The sense of being leaders in a movement for change in the faculty – a movement that is based on interpersonal relationships and shared experience – is something that often emerges in our reflection and planning sessions as the element of the program in which mentors feel most pride.

A second finding that we had not expected was the extent to which students’ desire to build meaningful and ongoing relationships extended to relationships with faculty staff and program facilitators. This understanding emerged, for example, through the mentors’ reflections on the training sessions run for the 2003 and 2004 programs, when we were planning for 2005.

In both 2003 and 2004, we had invited professional trainers to lead the training sessions. While mentors had responded very positively to these sessions in on-the-spot feedback, when they reflected on the experience in the context of the whole program and in their role as collaborators in program planning, their preference clearly emerged for training to be facilitated ‘in house’, by those with whom they would have a continuing relationship.

Although considerably less polished and professional, our training sessions are now far more focused on building skills in the context of building relationships. They are fully facilitated by faculty staff who have an ongoing commitment to the program, in close collaboration with our most experienced mentors.

The importance of creativity

As noted, the literature suggests that faculty-specific approaches are ideal in addressing the varying needs of students depending on their area of study (McInnis, James & Hartley, 2000, p. 55). Accordingly, we have always utilised talents and strengths characteristic of Arts Faculty students, staff and alumni in ongoing program development. In particular, the Arts Network Program has always been distinctive in its use of creativity and humour, and has always facilitated involvement and participation through this creativity.

One example of this kind of activity in our program is an interactive role-play on Arty Starty Day, facilitated by faculty staff from Performance Studies, Paul Dwyer and 147Ian Maxwell. After an initial performance of a play about the challenging life of a first year student, audience members participate actively in recreating some of the scenes with a view to finding ways of dealing with some of the challenges. Another example of collaborative creativity is an interactive drumming performance we held in Orientation Week in 2006, in which everyone who came had a drum or percussion instrument, and so was simultaneously an audience member and a performer.

However, it has only been through the reflection and input of mentors in the program, through our action research cycle, that we have come to appreciate the importance of facilitating program participants to take more responsibility for this creativity themselves. This understanding emerged during mentors’ reflective input to planning for our ‘Arty Party’ program round-up events in 2004 and 2005. Staff were keen to involve our alumni in these events, and, in consultation with mentors, invited Adam Spencer (University of Sydney Alumnus and then host of the Australian Broadcasting Commission radio show The Triple J Morning Show) and Charles Firth and Andrew Hanson (Arts Alumni and stars of the Australian Broadcasting Commission television show CNNNN and The Chaser News Team) to join us for the 2004 and 2005 events respectively.

Mentors, however, made it clear that, while they very much valued the input of these well-known and well-loved former students, they also wanted to be responsible for some of the creative action themselves. Resultant highlights were Yellow Maple Leaf and Two Chopsticks: a light operetta on the joys of life at the University of Sydney (Arty Party 2004)4, Mentor Mayhem: the musical (Arty Party 2005)5, and the hilarious and most memorable Great Quadrangle Tutu Run of the Century (Closing Ceremony, 2004).

Perhaps even more significant in terms of broad participation and collaborative creativity have been the introduction of the Arts Network Photographic Scavenger Hunt (since 2004) and the Arts Network Theatre Sports Spectacular (since 2006). These activities have come about as the result of mentors’ reflections on how to engage first years as actively as possible in the program, and are largely planned and facilitated by the mentors themselves. They provide enticing and supportive opportunities for both mentors and first years to assert their individual and collective identities as Faculty of Arts students.

In the Photographic Scavenger Hunt, which takes place on the afternoon of Arty Starty Day, each mentor group (one mentor and six to eight first years) is given a disposable camera and invited to create a series of challenging and interesting photographic tableaus as they explore the campus together. These pictures are then shared on the program website and at the end-of-program Arty Party.

Theatre Sports is an activity that has more recently found its home at the Arty Party. The mentors enlist the help of other senior students in the faculty who are experienced in facilitating this activity. However the mentors themselves choose the nature of the

148games, keeping in mind the fact that they will be a new experience for many first years. What a joy it is to see the first years, who are often extremely nervous and hesitant when they first join us at the beginning of semester, throwing themselves without reservation into these highly interactive and amusing games just a few short weeks later.

The importance of image

Not only are the Program activities a lot more collaborative and fun as a result of the creative input of our student participants, but the whole image of the program is significantly more ‘funky’. The more we have engaged in critical reflection with our mentors and first years, the more apparent it has become that ‘funkiness’ is a crucial component of the identity they wish to construct for themselves.

In the early days of the program, for example, our students explained that they found considerable difficulty in feeling a sense of ownership over events with names like ‘Transition Workshop’ (now ‘Arty Starty Day’) and ‘Program Roundup’ (now ‘Arty Party’). Mentors also alerted us to the fact that the original program name, ‘The Faculty of Arts Transition and Peer Support Program’ was likely to evoke memories of High School buddy programs amongst prospective first year participants. They were instrumental in changing the name to ‘Arts Network Mentoring Program’, which not only emphasises the network-building aspect of our activities, but also seems decidedly more attractive to first years.

We have found evidence for the value of our funky new image, along with our interactive and creative activities, in two places. Firstly, in each year since the program started, our participant numbers have grown significantly. In 2003, approximately one fifth of commencing Arts students registered for the program. By 2004, the proportion had increased to one in four, and in 2006 well over one third of our new first years signed up to be involved. Further evidence emerged last year in the major online forum for students in the final year of high school, the ‘Bored of Studies’ Student Community Forum (Bored of Studies, 2006):

Hi, Anyone going to be joining the Arts Network Mentoring and Transition program? (http://www2.arts.usyd.edu.au/ArtsNetwork/index.cfm) I’ve been looking at the website and reading it, I think I’ll sign up. (Manifestation, 19 Jan 2006, 10:20 PM)

Hmm. This sounds quite handy. I’ll probably sign up. Thanks for the tip-off. (Seryn, 19 Jan 2006, 10:34 PM)

I like how on the site it says ‘A highlight of our program is the ‘Arty Starty’ Day’, they really won me over with the ‘arty starty’ lol [laugh out loud] this is so the faculty for me. (DeepDarkRose, 19 Jan 2006, 11:35 PM)

I know I cracked up at that too, it sounds good. I just hope some lovely people/s will befriend me or I will befriend someone/people. See you there. (Manifestation, 20 Jan 2006, 1:13 AM)

yeah apparently there’s a photo hunt that we have to do to bond or something… i can’t think of a better way to start uni than to run around like crazy taking photos of people stuck up trees, adulthood, here we come! (DeepDarkRose, 20 Jan 2006, 11:50 PM) 149

Haha… it is fun, I went last year. And this year I’m a mentor, so you might end up stuck with me! (Beanbag with Legs, 21 Jan 2006, 12:21 PM)

Conclusion

Fostering a sense of cohesion has proven challenging in a faculty as large and diverse as the Faculty of Arts at the University of Sydney. However, as one of our mentors so aptly put it, ‘Because of the sheer size of the Arts Faculty and all the disparate majors we can do, it’s wise to instill a sense of network and community early on.’6 The importance of this sense of network and community is clearly stressed in the literature on tertiary transition, as is the value of mentoring programs and the need for faculty-specific approaches in achieving this goal. Just what constituted an appropriate approach in the context of our faculty was the question we needed to answer as we commenced our transition and mentoring program in 2002.

Through a process of participatory action research over five program cycles, we have gained understandings about some of the key features of a mentoring program that can help our first years to develop as sense of identity and belonging in our faculty community, and we have refined our program accordingly. The key features we have uncovered to date as most relevant to students in establishing a sense of identity and belonging in our context are the importance of relationships, the importance of creativity, and the importance of image. In each of these three areas, we have needed to pay careful attention to our students’ voices to determine the breadth of the relationships they seek, the kind of creative activities they are motivated to be involved in, and the nature of the image they wish to establish for themselves. In this way we have been able to support them in creating their own communal identity as arts students, rather than asking them to conform to an imposed or received sense of what an arts student is. Our students’ positive responses to the changes we have made in our program strongly support the suggestions we found in the literature regarding the value of initiatives that are sensitive to context, rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all approach.

While more traditional forms of evaluation, such as on-the-spot feedback questionnaires, do continue to give us valuable information about the response of our participants to various program events, it is the collaborative and integrative dimensions of the whole participatory action research cycle that provide us with the deepest understandings about our students and our program, and lead to the most meaningful change.

150

4 Appropriation, abridgement and contortion of lyrics by Arts Network Mentor Sikeli Neil Ratu; Original score by Divers Dead White Males with particular apologies to Edward Elgar, W.S. Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan, Vic Mizzy, Warner Bros, Tim Rice and Lord Lloyd-Webber; performed by Melanie Cariola, Katharine Sampford, Louise Harris, Rachel Hardy, Amanda Setiadi, Christine Janssen (Mentors) and Nerida Jarkey (Program Director); narration by Ian Maxwell (Performance Studies); musical support by Mami Iwashita (Japanese Studies).

5 Music and words adapted by Arts Network Mentor Rachel Hardy from Avenue Q: The Musical by Robert Lopez and Jeff Marx; performed by Tom Tramby, Trieste Corby and Rachel Hardy (Mentors), accompanied by Elise Hopkins on piano (Mentor).

6 Mentor comment on Web CT discussion board, 10 November 2005 (quoted with permission).