Chapter 9

Students’ experiences of learning in the operating theatre

Faculty of Medicine

The research reported in this chapter draws on the work for my PhD (Lyon, 2001) completed whilst I was working in the Discipline of Surgery within the Faculty of Medicine. Employed as an educationalist, my role was to advise on effective teaching and learning strategies in clinical education. As part of their surgical studies, students rotate through a series of hospital attachments related to various specialties where they assist and observe the team management of patients, on wards, in clinics and in operating theatres. This is common practice in surgical education in medical programs around the world, and is founded on the apprenticeship model of learning. The emphasis, for the most part, is on learning the principles of surgery through involvement in patient care and the clinical activities of the specialty, supported by clinical tutorials. Students attend the operating theatre with their patient to observe the procedure when an operation is the chosen management option. They learn about the principles of management and postoperative care. They are not expected to have a thorough understanding of the technical details of surgery nor to develop technical skills in the operative procedure itself.

In my role as educationalist I was keen to find out how the surgical attachments were perceived by the students. I saw my role as assisting clinical teachers to focus on and interpret their students’ experiences as part of the process of developing their teaching, as suggested by Prosser and Trigwell (1999). Through understanding the students’ perspectives we are ‘… better placed to make sense of their engagement with and reactions to educational settings’ (Taylor, 1994, p. 71). Data from student feedback questionnaires had indicated positive ratings for most features of the surgical program but mixed ratings on items relating to the operating theatre. Theatres offer considerable potential for medical students to construct a ‘clinical memory’ (Cox, 1996) by integrating tactile sensations of live pathology with visual images and verbal learning. They present an opportunity to observe real clinical problems and surgical decision making, to begin to appreciate what surgery means to patients, and to gain important insights into multi-professional teamwork. Despite its potential, the students had very mixed opinions on its value for their learning. I arranged a student focus group to explore the issue. I had allowed one hour but 1.5 hours later we were still talking. A rich story began to unfold as students described the challenges for the learner in the complex and highly charged workplace of theatres.

A search of the published literature for educational studies in this setting provided little guidance on best practice. Whilst surgical educators have written at length about the characteristics of surgical attachments, the focus, for the most part, has been on curriculum content and objectives; assessment; and effective teaching at the bedside, on ward rounds and in clinics. In terms of reported studies we know the least about teaching in the operating theatre (Dunnington, DaRosa & Kolm, 1993, p. 523). What literature does exist is largely normative in character and focuses on teachers’ perspectives with surgeons emphasising the potential of the operating theatre and its under-utilisation for clinical teaching. The small number of published empirical studies are also largely teacher focused, with the aim of identifying appropriate content and effective teaching behaviours to inform faculty development (Cox & Swanson, 2002; 96Dunnington et al., 1993; Hauge, Wanzek & Godellas, 2001; Lockwood, Goldman & McManus, 1986; Scallon, Fairholm, Cochrane & Taylor, 1992; Schwind et al., 2004).

The literature on effective teaching and learning in higher education assumes that the teacher has the capacity to change the learning milieu to meet the learner’s needs (see for example, Ramsden, 2003) but the operating theatre is a workplace where patients’ needs, and not the needs of students, come first. When medical students attend the theatre they become ‘peripheral participants’ in what Lave and Wenger (1991) describe as a ‘community of practice’. In this context they need to be able to make the most of their experiences. Managing their learning in the complex and unpredictable reality of the operating theatre is more akin to strategies used in workplace learning than in other contexts in higher education. It is the literature on learning in work-based settings that proved to be the most relevant in the analysis and interpretation of the findings reported here.

Methods

This study is focused around two main research questions: How do students learn in the operating theatre? and; How can students be helped to make the most of their learning in the operating theatre? The research consists of an interpretive case study using multiple methods including observations in the operating theatre on 12 separate occasions, two group interviews with 7 students, 15 in-depth student interviews, and 10 in-depth interviews with surgeons. Students were selected randomly for the in-depth interviews, but the more personal approach of snowball sampling (Merriam, 1998) was adopted for the surgeons. The interviews were unstructured and relied on the technique of ‘funneling’ (Minichiello, Aroni, Timewell & Alexander, 1995, p. 84). This involved starting the interview with an open-ended invitation to the surgeon or student, for example, ‘Tell me about your experiences of teaching/learning in the operating theatre’, and then guiding them, as necessary, towards specific issues. Theatres were selected to represent the main surgical attachments in the medical program.

Qualitative methods were chosen to uncover the students’ perceptions of their experiences of learning in theatres, ‘to gain access to the motives, meanings, actions, and reactions of people in the context of their daily lives’ (Minichiello et al., 1995). These were combined with a questionnaire administered to one cohort of 197 out of 237 students (i.e. a response rate of 83%). The questionnaire was designed to locate the students I had interviewed, within the larger student cohort. Questionnaire items were derived from the analysis of data from the focus groups and in-depth interviews.

Typed transcripts of the interviews together with the field notes from the observations were coded and retrieved using computer software to manage non-numerical unstructured data. The data were analysed using the ‘immersion/crystallisation’ approach (Miller & Crabtree, 1992, p. 19). The aim was to identify the themes that characterised the case. Conceptual labels were developed using the constant comparative method (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The questionnaire data were analysed using SPSS for Windows (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences).

Managing learning across three domains

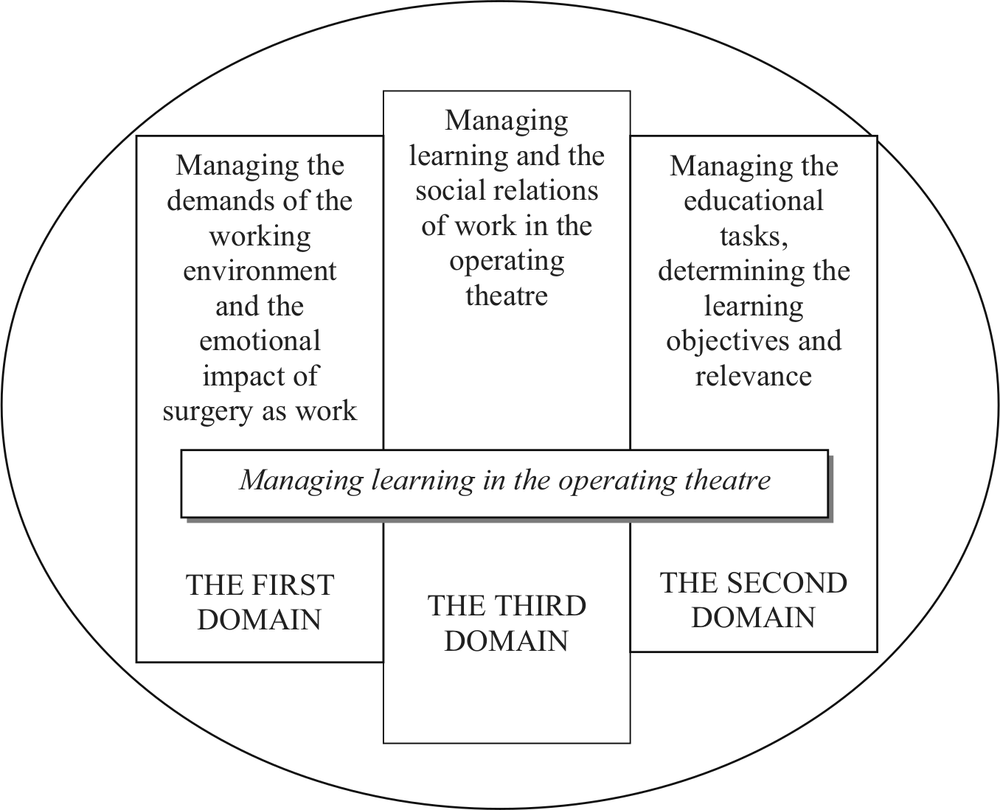

The ‘core category’ (Strauss & Corbin, 1990, p. 121) derived from data analysis, which illuminates what the data were essentially about, was that of ‘managing learning’ in the operating theatre. In the early years of the medical program students acquire skills in managing their learning in traditional teaching sessions, at lectures, seminars and 97tutorials. They know how to make the most of these learning opportunities. The operating theatre represents a new and unique challenge. It is a professional workplace setting where the surgeon performs surgical procedures working with a team of highly trained anaesthetists and nurses. In order to make the most of this experience, students need to find ways to manage their learning across three related ‘domains’ (Lyon, 2003) each with its own challenges (see Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1. Managing learning across three domains

The first domain: Managing the demands of the workplace environment

The operating theatre is a noisy, busy and sometimes tense working environment. Students have to learn to negotiate the physical environment of the operating theatre with its designated spaces, some sterile, some non-sterile, each designed for a specific function; to learn the many theatre protocols; and to familiarise themselves with the culture. It can be intimidating. This is in part, because of the fear of doing something wrong and adversely affecting the patient outcome. In part, it is the fear of appearing foolish in front of a team of experienced professionals. More than 70% of students indicated their agreement with the questionnaire item, ‘It’s easy to be made to look a fool in theatre’. One student at interview commented:

You can make a fool of yourself if you make a bold statement and you really didn’t have a clue … So, You’ll say, ‘Would that be the …?,’ this is what I was saying before, you’ve got to be fairly sure you’re right if you’re going to ask them to explain the anatomy to you because you don’t want to be made a fool of … You can make a fool of yourself if you don’t know the 98anatomy of the operation. You can make a fool of yourself if you don’t know the etiquette of green, and you don’t know the etiquette of sterile fields. Initially when you haven’t scrubbed much you’re reticent to ask to scrub just simply because it is a ritual you’re unfamiliar with and everybody’s going to be watching you and you don’t want to look clumsy. That’s something that you’ve got to overcome, … and you just keep on doing it and doing it and OK you might have to make a fool of yourself, ten, twenty times maybe, you know, before it’s absolutely down pat. (Student 5)

Students have to learn to cope with the emotional impact of surgical procedures and the tensions that arise amongst the various players in the theatre when complications arise. Thirty-eight per cent of students indicated that they found the tension ‘disturbing’ in half or more than half of the theatre sessions they attended. Surgeons are mindful of this tension and the effect on the student:

You [the student] are faced with a series of things that are really quite alarming. To see the first operation, … it is a fairly disturbing thing for most people. … In general it’s frightening, and, … if you are watching something major, the amount of tension and emotion that is generated, is also very disturbing. You come to feel that this emotion must mean that there is something going wrong, and all this display of temper means that you’ll never get out of this situation. (Surgeon 1)

Over the course of time, members from the three professional groups (anaesthetic, nursing, and surgery) in any particular theatre come to share a common history, a team culture with shared norms, routines, ground rules and humour. Students, rostered for four weeks at a time to the various surgical attachments enter this setting as a newcomer with no clearly defined role to play in the team. In response to the questionnaire item, ‘I have no clear part to play in the team’, 48% of students indicated it was the case in all or most of the theatre sessions they had attended with a further 22% finding it to be the case in about half of the sessions they attended. For students the experience is often one of being a nuisance, an outsider, and of getting in the way.

You stand around a lot – you know you really feel very out of place and just like a nuisance more than anything else. You have learning needs but you aren’t actually useful in any way … you just feel unnecessary. (Student 2)

I was just going home in tears at the end of the day because I was just feeling like I didn’t know why I was meant to be there. (Focus Group 1)

[Descriptive note] The student tells me that the registrar had said to them earlier that they should be useful if they come to theatre but ‘What can we do?’ asks the student. He says the registrar had told them not to be ‘parasites’ and not to get in the way. (Observation 7)

The extent to which students are able to manage these challenges has a significant effect on what they learn from their experiences. 99

The second domain: Managing the educational tasks

Students who reported useful learning experiences came to the operating theatre well prepared with a positive intent to learn and were able at interview to clearly articulate the learning objectives as they saw them, and the relevance of going to theatre, whilst attending to the assessment requirements. At the time of the study the learning objectives were not clearly spelt out in any of the curricular documents, yet the majority of students could see the relevance of attending theatres.

Statistical analysis of the survey data indicated a significant correlation (P<0.01) between students’ perception of the importance of understanding what happens during surgery, and their perception of the usefulness of time spent in theatre. Interestingly, students who had no intention of pursuing a surgical career could nevertheless see value in attending theatres. Those planning to be general practitioners or planning a career in medicine could see its value as preparation for internship, and for their later professional practice, when they will need to explain surgical procedures to patients:

I don’t ever imagine I’ll be a surgeon … but knowing how they actually do an operation is useful because patients always ask you how they’re going to do it. And you can only tell them if you’ve seen it. So I think that’s very useful to know. [Patients ask] how long is it going to take and what position am I going to be in and all those things, they just don’t appear in textbooks, you have to have seen it. (Student 2)

At the time of the study, students were required to complete various assessments including case histories based on patients they had studied. (With the introduction of the new graduate-entry medical program students are no longer required to submit case histories.) Students were critical of the workload and time involved in relation to the small percentage of marks allocated to these in the overall assessment scheme. Students were conscious of using time efficiently given their perception of what was needed to pass the final examinations. Learning from the operating theatre requires time: the time it takes to get changed and find the right theatre; the time it takes waiting for one’s patient to arrive; and the time waiting between operations:

The only problem with learning in theatres is that it takes so much more time, because you have to spend all that time waiting around, scrubbing up, and I think you do most of your learning in the first half of the operation … but you have to stay on to watch all the stitching and everything … (Student 14)

… a lot of people would prefer to do that [studying from a textbook]. [It’s] not that they’re not interested but simply because at the end of the year comes the exams and the way the exams are structured it’s much more beneficial to do this [than go to theatre]. (Focus group 1)

Students at interview were able to articulate their own learning goals when prompted which suggests that it is up to the student to define the objectives in relation to what they want to learn from the operating theatre, but given the unpredictability of their experiences, they need to be able make the most of their experiences whether positive or negative. 100

The third domain: Managing learning and the social relations of work

Medical students are at the end of the training queue in large teaching hospitals, behind interns, residents, registrars and surgical fellows. Whilst some surgeons will promote the medical student in the queue, as and when appropriate, ‘sponsoring’ the student and inviting him/her to scrub up and stand at the operating table, most students find they have to promote themselves, to earn a place in the team. Students who report getting the most out of their experiences learn to negotiate the social relations of work in theatre, to participate in the community of practice (Wenger, 1998) constituted by the operating theatre and its personnel. Students ‘size-up’ the learning milieu. They engage in a reflective process ‘in which what is perceived is processed by learners and becomes the basis of new knowledge and further action’ (Boud & Walker, 1991, p. 19). They reflect on the cues in the learning milieu of the theatre as they see them, sizing up the opportunities and challenges and making choices about their learning behaviours. This reflective process, which Boud and Walker refer to as reflection-in-action is the key to understanding experience-based learning. Central to the reflective process, they suggest, are two important aspects of the learning experience; noticing and intervening.

In one sense noticing is a central objective of the student’s experience of attending theatre, where noticing is defined narrowly to refer to learning through observation of the surgical procedure and management of the patient. The operating theatre affords all students the opportunity to learn from observing the procedures, more or less, depending on their view of the operating field. Some students exploit the opportunities further. They notice not only the procedure but what is happening in and around them. They take stock, sussing out the responsiveness of the surgeon. They take note of the attitude of the nursing staff; the emotional climate; the busyness of the theatre; the norms of the team with respect to rules of dress, etiquette and infection control; and the likelihood of a place at the table. They notice and reflect on how the surgeon treats other more senior surgical trainees. They are looking for ‘student-oriented’ theatres with surgeons who are willing to teach and sponsor them for a place in the team.

Where and when they consider it ‘safe’ and appropriate, they initiate interaction. They use a number of strategies or interventions (Boud & Walker, 1990) to influence their experience. These may include going forward and introducing themselves confidently, explaining why they are there and their interest in the case; assisting with the patient preparation without being prompted; asking directly to scrub in and assist; asking intelligent questions about the radiology; behaving professionally and presenting themselves as a legitimate learners worthy of a training place. They intervene, tailoring their approach to the demands of the particular theatre and its personnel, becoming ‘active co-constructors’ of their opportunities to learn (Taylor, 1996, p. 235).

I do think you have to be quite assertive. You really have to go up to the surgeon and say, ‘Hi, I’m so and so, and I am really interested in this. I would like to assist if you can possibly let me. I really want to see this or that’. And that, they respond usually quite well to. The student who goes into theatre and doesn’t say anything and stands in the corner generally doesn’t get very much out of it. (Focus Group 2)

Students who come to theatre with a positive intent to learn promote their presence as learners ‘earning points’ (Surgeon 10) by showing interest, preparedness, 101motivation, or prior experience, by behaving professionally and having the confidence to initiate interaction:

(I questioned the student about whether she asks to scrub in or waits to be invited.)

I guess I’d ask, … as long as I was in a situation where I was … had enough credibility to ask, I’d seen the patient before and knew something about what’s happening and it was an appropriate operation to scrub in on.

(I asked her how she establishes ‘credibility’.)

You see the patient beforehand, you know all about their story and physical signs (for when you’re asked), maybe you’ve seen the surgeon before in unit meetings or on ward rounds. Perhaps the surgeon knows you by name and you’ve turned up on time, behaved professionally, told them who you are and they trust you (Student 3)

If the student is successful in achieving legitimacy, and if the surgeon trusts and has confidence in the student’s ability to assist, he/she will act as a sponsor or advocate, when the situation is appropriate, creating a legitimate role for the student to play as a ‘peripheral participant’ (Lave & Wenger, 1991) with the potential for positive learning outcomes:

… after my orthopaedic experience [overseas elective], when I did orthopaedics back here and I showed interest in it they actually let me participate in it … I mentioned to him that I did a bit of orthopaedics previously … and basically … it came out that I had some theatre experience … He showed me a couple first and when he felt comfortable that I knew what I was doing, and he was able to supervise me in case something went wrong, he let me in, allowed me to do it and it was pretty good. (Student 9)

Establishing credibility, negotiating a role to play, and having that participation supported and acknowledged as legitimate, is crucial to student learning in theatres. Survey data lend additional support to the analysis of data from observations and interviews, showing a significant correlation between questionnaire items indicative of students negotiating a role in the team, the willingness of surgeons to teach, and students’ perception of the usefulness of time spent in theatres.

Strategies to promote effective learning in theatres

Models of learning from experience share a focus on reflection that they owe to David Kolb who provided the groundwork for modern experiential learning theory with his experiential learning cycle (1984). For Kolb, learning was grounded in experience and reflection on that experience. In the research reported in this chapter it is the students’ capacity to reflect on their experiences of the operating theatre and act on the basis of that reflection that crucially affects their learning (Lyon & Brew, 2003). The model of learning from experience and of reflection in learning developed by Boud and colleagues (Boud, Keogh & Walker, 1985; Boud & Walker, 1991) from their research on work-based learning situations, was selected for its relevance in understanding students’ responses to the operating theatre as a workplace, as well as for suggesting ways in which learning in professional contexts such as the operating theatre can be enhanced. 102

In their model they identify three stages of reflection associated with experiential learning activities: preparation for the event where the focus is on the learner and the learning milieu and the development of skills and strategies for reflection; reflection during the event with a focus on noticing and intervening; and subsequent reflection after the event (Boud & Walker, 1991). Curricular initiatives which have been tried, planned and suggested in relation to these three stages will be described (see also Lyon, 2004).

Preparation for the event

Here the focus is on preparing the student for what the event has to offer which includes equipping them with strategies to assist them with their own reflection-in-action, i.e. strategies to help them to notice what will be occurring in the event, what situations they are likely to encounter, appropriate modes of dress and behaviour, what opportunities are likely to be found and in particular how to intervene usefully to make the most of the opportunities.

Three initiatives have been introduced to help medical students to prepare for theatres: a session in the hospital orientation program designed to alert students to the complexity of the workplace, to point out the relevance and potential of learning from the theatre and to show how previous students have intervened to use the opportunities, drawing on data collected for the research reported here; a half-day interactive teaching session conducted in the theatre suite which includes handwashing, gowning and gloving, theatre protocols, basic surgical instruments, and an overview of the steps typically involved in an operation; and a new section of text in the student handbook outlining the learning objectives together with a list of ‘must see’ operations.

Reflection during the event

Here the focus is on helping students in theatre to engage with the learning experience, to notice and to intervene to promote their own learning. Sometimes in theatre a senior registrar would be conducting the operation under the supervision of the senior surgeon who, when the operation was running smoothly would be free to direct students to notice things that might have otherwise have gone unnoticed, to assist the interaction between the learners and the learning milieu. In one particular interview a student recalled an occasion where the surgeon, alert to the learners’ feelings, changed the learning milieu from within by limiting the aggression of another member of the team, assisting the learner to resolve negative emotions which inhibit noticing.

So the surgical and nursing staff have a role to play to help students make the most of their experiences. The findings from the research reported here have been presented at departmental meetings at various faculty committee meetings, to clinicians and allied health staff participating in the Master of Medical Education Program, at University of Sydney College of Health Sciences conferences, and more widely at medical education conferences, with interactive sessions to help clinical educators think about how to engage students more fully with the learning experience.

The student handbook, mentioned earlier, now includes an intervention to assist students to monitor and reflect on their learning in action. It includes a template to help them make a written record to capture the learning event and is designed for students to take with them to theatres, to help them focus their attentions and to remain focused. 103

An additional way to enhance students’ reflection in action is to help them to understand the model of reflection itself. This can be a useful way for them to extend their repertoire of responses in the operating theatre. So teaching the model to students is a suggested way of highlighting to them the importance of reflection as a way of helping them to manage their learning more effectively. Students who can apply Boud and colleagues’ models of reflection and learning from experience to their own practice will be better able to manage their learning in complex settings.

Subsequent reflection on the event

Here the focus is to help students to process their experiences and to extract, consciously, learning outcomes from them. Three elements have been identified as helpful: returning to the experience, attending to feelings, and re-evaluation (Boud, Keogh & Walker, 1985). It did seem that the medical students in the study reported here had given some thought to their experiences, in respect of the first two elements, prior to attending the interview, maybe in preparation, and some said they had talked through their experiences with their peers. Some recalled times when surgeons had used the time in the lunch room to engage the student in reflecting on the morning’s theatre session, or the next day on the ward or in a follow up tutorial.

Whilst the individual learner can work through the three elements alone, trained facilitators bring a range of techniques to help learners deal with challenging situations. A facilitator can assist students to deal with negative experiences which distract from further learning by helping them to express these feelings and then by discharging or transforming the feelings. Boud and colleagues argue that some of the benefits of reflection may be lost if they are not linked to action. In the new graduate-entry medical program students write a reflective portfolio, often revealing strong feelings about clinical events they have witnessed or been a part of, including experiences in the theatres. Follow up portfolio interviews conducted by faculty staff provide a formal opportunity for all students to re-evaluate their experiences and to make a commitment of some kind on the basis of their learning, in preparation for new experiences. Interactive personal and professional development workshops have been introduced to help students develop skills to deal with challenging clinical environments. In addition, interprofessional learning projects have been developed where medical students work in the clinical setting with students from nursing and the allied health professions to help them develop effective team skills.

Implications for practice

It is useful to think of a spectrum of learning behaviours in theatres. At the one end of the spectrum are behaviours which demonstrate little or no attempt to engage in learning. These behaviours are indicated when students take up a passive role as unscrubbed observer standing back against the wall, making no attempt to extend or test their knowledge, looking bored and seemingly uninterested in anything but being seen by the surgeon to have their attendance recorded. At the other end are more active or more adaptive learning behaviours – best indicated by students who engage in a reflective process, successfully managing their learning across the three domains identified earlier in this chapter. They engage in a cycle of noticing, reflecting, intervening, noticing and reflecting. They size-up the learning milieu noticing the attitude of the staff, the emotional climate, and the opportunities to scrub up and assist. They use various strategies or interventions to maximise the learning outcomes. They 104recognise the need to promote themselves, to gain the surgeon’s trust and to gain legitimacy. They present themselves as deserving students, showing interest and intent, motivation, professional behaviour and respect. They seek out ‘student-friendly’ surgeons they, in turn, can trust, surgeons who acknowledge their role as a teacher and are willing to act as an advocate for the medical students, inviting them to participate in the practice of the operating theatre. All other parts of the spectrum represent varying degrees of engagement with the learning milieu.

Learning behaviours are not fixed. The active approach can be thwarted by an ‘unsympathetic milieu’ (Boud & Walker, 1991, p. 17), on the other hand a particularly favourable mix of variables in the milieu can draw out more active behaviours in a student who would routinely respond more passively. Curricular initiatives have been developed to provide students with formal opportunities to actively prepare for the event, to help them to engage more fully with a challenging learning milieu during theatre sessions, and to reflect on their experiences. These open up the opportunities for all students to make the most of the operating theatre, extending their learning by creating new and useful integrated experiences.

In the operating theatre patient care is paramount and non-negotiable: the first responsibility of all team members is to the patient. All surgical procedures are serious work and all have an element of risk. Unlike conventional teaching situations the surgical teacher has very limited opportunities to change the environment to promote effective student learning. The operating theatre is more like work-based learning situations where it is too dangerous for novices to engage fully in the actual tasks being performed, for example, learning to manage a nuclear power station or a chemical plant. Boud and colleagues’ (1985) model of reflection and Boud and Walker’s (1990 & 1991) model of learning from experience provide the educator with a practical approach to helping students to manage their learning in these complex multidimensional workplaces. The findings from the research reported in this chapter have implications beyond surgical education, to other work-based learning situations which present an equally challenging learning environment. Educators can engage the learners in these situations by promoting the cycle of noticing, reflecting, intervening, noticing and reflecting, and extend them by providing the learners with formal opportunities to actively prepare for the experience, to engage in reflection during and after the experience and to understand the nature of the reflexive process itself.