Chapter 15

Transforming learning: using structured online discussions to engage learners

aFaculty of Medicine, bFaculty of Health Sciences

It is widely recognised that the landscape for higher education has undergone rapid change, with increasing pressure to be accountable, perform according to measurable standards, compete for funding and accept a greater diversity and increased number of students. This has necessitated the need to ‘do more with less’ (Ramsden, 2003, p. 4). However in parallel there have also been changes that have fostered innovative teaching and learning practices. These include new possibilities for place, space and mode of learning through the use of technology, increasing student competency in the use of this technology, a greater focus on student learning and the building of collaborative relationships between universities and the professional community (Huber & Morreale, 2002).

Teaching and learning in the health sciences has an added complexity with the expectation that graduating students are ready to practice in an increasingly complex working environment. The knowledge explosion and need for public accountability of professional practice necessitates a shift to equip students with skills to continually evaluate their own practice and provide evidence based clinical practice. There is pressure placed on teachers of health science students to adopt tripartite roles as teachers, researchers and clinical practitioners (Bignold, 2003). Health science education is being further squeezed by the need to educate greater numbers of students in clinical settings that are constrained by the physical environment that places patient safety above opportunities for students to learn professional skills.

The factors described above coupled with the University of Sydney’s adoption of the learning management system Web Course Tools (WebCT) provided the impetus for the authors to explore the use of asynchronous discussion activities in their group of undergraduate students and reduce face-to-face teaching time.

Online asynchronous discussion forums are widely accepted and utilised in tertiary education to promote student engagement and group collaboration. Learners are able to interact by negotiating, debating, reviewing and reflecting upon existing knowledge, thus building a deeper understanding of the course content (Garrison & Anderson, 2003; Palloff & Pratt, 1999). Yet, the potential afforded by a collaborative online environment is often criticised because learners fail to take full advantage of the learning experience, and lecturers become entangled in the time drain required to moderate the ensuing discourse (Spector, 2005).

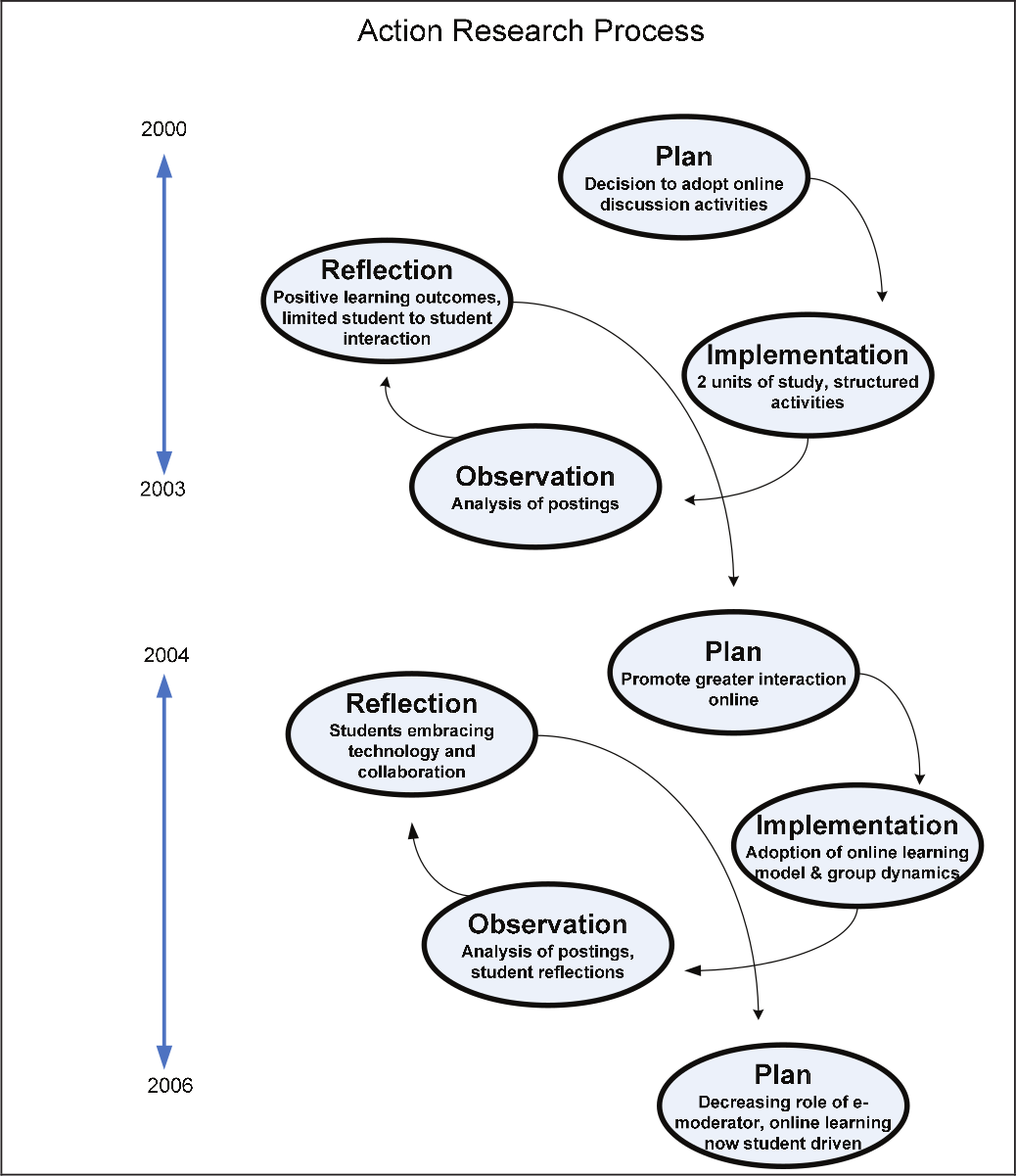

This chapter will draw on the authors’ experiences in and research about facilitating online discussions in the blended learning environment of an undergraduate allied health science course. Action research cycles conducted from 2000 to 2006 will be used to map the development, analysis and modification of the online discussion tasks.

Context

The cohorts of students described in this research were those enrolled in the Bachelor of Applied Science (Orthoptics). The course is a four year undergraduate program which provides students with knowledge and skills of investigating, managing and 164researching disorders of the eye and vision systems. Upon graduation, employment exists in a broad range of clinical, community and corporate environments.

The clinical program forms an integral component of the course and strives to provide an environment which facilitates the transfer of knowledge, skills and attitudes fundamental to the development of a competent beginning orthoptic practitioner. Workplace expectations demand a practitioner who can service a broad patient population including all ages, differing racial backgrounds, and populations with particular needs such as brain injured, developmentally delayed and vision impaired.

The quantitative data analysed for this research was taken from the student cohort enrolled in the third and fourth years during 2003-2005 with an average enrolment of 40-50 students per year. These years were selected as the students spent one semester of third and fourth year off campus completing a full semester clinical unit. Prior to 2000 students had attended regular on-campus tutorials during the clinical semester. These tutorials were transferred to the online environment in 2000 resulting in minimal compulsory on-campus attendance.

Research process

We used an action research framework which brings ‘practice and theory, action and research together’ (Gibbs, 1995, p. 30). It enables lecturers to analyze their practice, make planned changes, reflect on the effect of the changes and plan for additional changes, by carrying out a systematic cycle of action, with both teacher and learner input. Each cycle informs future curriculum design addressing specific problems and leads to improvements in practice. Salmon (2002) also supports the use of action research as an approach to researching online communication as it binds together constructivism with the reflective nature of online discussions. This allowed us to demonstrate how the initial triggers of reduced staff time and increased student numbers led our development in the use of online discussions, which after systematic review and analysis raised further areas of inquiry and questions, requiring modifications, further investigation and evaluation. The direction of the modifications were also influenced by student evaluations, reflections about their learning and informal feedback. Figure 15.1 following, outlines the action research cycles we moved through over a number of years as we developed greater understanding of how to improve student interaction and learning in asynchronous discussion activities.

Adopting an action research approach to our study, demonstrates key aspects of the notion of scholarship of teaching described by Trigwell, Martin, Benjamin and Prosser (2000, p. 156), namely an active process that ‘involves reflection, inquiry, evaluation, documentation and communication’. Critical to this process is focusing the research activity on understanding how the area being studied improves the quality of student learning, by understanding the student experience and participation of students in the research process. As stated by Huber and Morreale (2002, p. 21) ‘what matters in the end is whether…students’ understanding is deepened, their minds and characters strengthened, and their lives and communities enriched’. 165

Figure 15.1. Action research process

Action research conducted from 2000 to 2003

Plan

There were a number of influences which led the authors to adopt the use of asynchronous discussion activities in two units of study in the 3rd and 4th year of the course. Primarily the decision was resource driven: a doubling in the number of students, staff reductions, and a finite number of clinical placements where students could gain clinical exposure to a range of patient conditions, and a new curriculum opportunity with the development of a new unit of study. This coupled with centrally supported WebCT resulted in a low risk of experiencing technology failures while implementing these activities. The authors felt confident that successful face-to-face tutorial experiences could be easily transferred online, and in fact delivery online would improve the repetitive nature of the face-to-face tutorials. It also allowed students equitable access to all tutorials rather than the one they were scheduled to attend on-campus. Using this medium would also enable greater contact with students whilst remote from campus, encourage peer support, a team approach to solving problems, and promote linkage between theory and practice. In summary it was felt that the online discussion activities would enhance and extend the learning opportunities for the students and present the authors with an exciting opportunity to experiment with a new medium for teaching and learning. 166

The theoretical framework that guided our design of online discussion activities, and intended learning outcomes was that of a social-constructivist and experiential learning perspective (Levy, 2006). Students would examine their clinical experiences in light of underpinning knowledge, and derive new understandings through dialogue with their online community consisting of their peers, clinicians and lecturers, who could work collaboratively, share resources and solve clinical problems.

Implementation

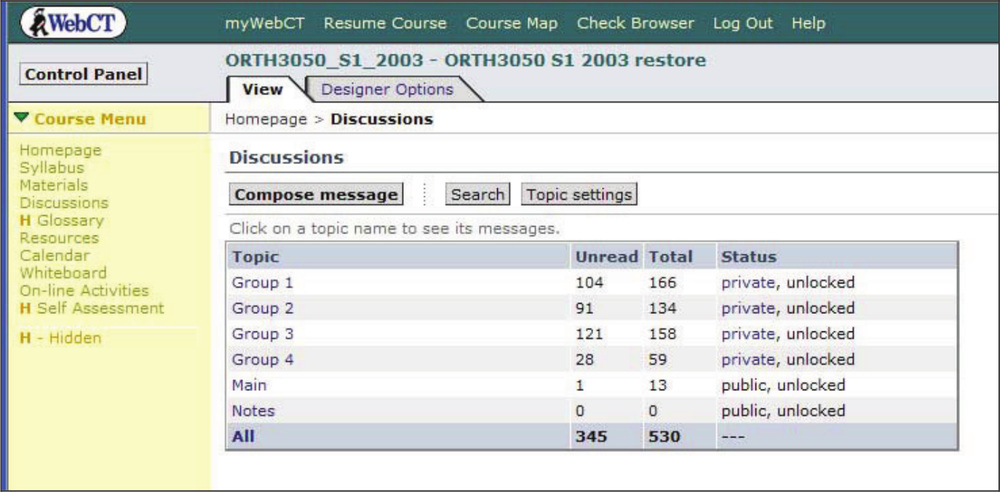

As both the students and authors were new to WebCT an on-campus orientation session was held to assist students navigate through the site and access the discussion activities. Time was spent reviewing the discussion tool and its intended use. Students were introduced to their allocated groups (8-10 per group) and discussion activities were structured around questions and clinical cases. An explanation of student requirements was provided including a minimum of 5 postings (equivalent to students posting 1 message for case) in one unit for students to be eligible to take part in practical exams and an assessment of the quality of student postings. Figure 15.2 shows the set up of the discussion area in WebCT for one unit of study at the end of the semester in 2003.

Figure 15.2. Discussion area appearance in 2003

The role of the e-moderator in the discussions was also explained. Students were shown the instructors’ view of the WebCT site which showed data for each student’s access (first and last access of site), and participation (number of messages read and messages posted). This surprised many students and demonstrated the overall presence of the e-moderator to track participation.

From the beginning of the semester, work in online discussion groups began with groups that completed tasks being rewarded with feedback from the e-moderators at predetermined dates. The authors participated as e-moderators during this time, frequently joining online student discussion, resisting the temptation to ‘teach’ but rather letting discussions evolve and be student-led. There are various styles of e-moderation (Mazzolini & Maddison, 2003), of which our styles most closely resembled that of a ‘guide on the side’. Table 15.1 outlines the format for one of the cases that was discussed by the students, the marking criteria used and an example of feedback provided by the e-moderator. 167

Table 15.1. Sample instructions, case materials and feedback for one case used in 2003

| Instructions given to students for discussion case | |

|---|---|

| The aim of this activity is for you to discuss the clinical findings and reach an appropriate diagnosis and management for your case. You can request further clinical findings from the e-moderator, and if these are available these will be given to your group. | |

| You will then need to decide as a group the diagnosis, differentiate it from other similar conditions, and write a short and long term management plan. | |

| Using the patient details presented in the WebCT discussion section, you should as a group, do the following: | |

| Part A: Due by 8th April | |

| Review the patient details, discuss the case and then request any additional clinical information. | |

| After 8th April no additional information will be provided and the discussion will be closed off for Part A. | |

| Part B: Due by 30th April | |

| Decide as a group, post a suitable diagnosis and construct short and long term management plans, in a step-by-step way. | |

| By 30th April the group should have discussed and posted your entire group’s information, which will then be marked. | |

| Your discussions will be tracked. You should make sure you input into the group discussions and decisions at least three times before each deadline. | |

| Allocation of marks (group responses) | Allocation of Marks (Individual Responses) |

| Diagnosis including differential diagnosis (2) | Individual postings (8) |

| Insight into additional tests & relevance (2) | |

| Short term management (4) | |

| Long term management (4) | |

| Patient data and clinical findings for discussion case | |

| (provided at the commencement of the discussion as a posting by the e-moderator) | |

| Background history information | |

| Orthoptic and Ophthalmic clinical testing results for patient’s 1st visit | |

| Clinical test results for patient’s 2nd visit 2 months later | |

| Sample of feedback provided by e-moderator for one group | |

| General feedback: | |

| Overall, you tackled this case well. The diagnosis was well justified….. | |

| You had good ideas … | |

| Beware of drawing too many conclusions from … | |

| Your ideas for divergence training were interesting …I would agree much more with…. | |

| Your comment about … | |

| I wasn’t quite sure why… | |

| Approach to group work online: | |

| I think you worked fairly well as a group, although it was obvious that some people posted a lot more of the information than others. Remember, even if you come into the site to read, post a message to let the others know if you agreed/disagreed etc. That way, everyone is aware of your presence in the discussion area and students doing a lot of posting and discussion don’t get frustrated with the ones not posting. Please try to do this for your ophthalmic case to make it fairer to everyone in the group. | |

| Lastly, I was happy with how you threaded your messages. Maybe have definite headings for your next case, it might make it easier for people to post into the relevant area. | |

Observation

During the first year of implementing structured online discussion activities students enthusiastically embraced the opportunities that were provided to offer their insights about the cases being discussed. They stated that ‘the feedback (is) excellent’, it is ‘enjoyable conferring with peers’, and it ‘helped thinking outside square’. Tracking data available from WebCT indicated that students were reading the discussion board regularly and posting their ideas; although in the early years participation was limited by lack of access to computers outside the university (students without computers at home would not travel to the university from their distant clinical placements to access the materials).

As 2003 drew to a close the authors examined the discussion data more closely by developing research questions as part of the observation phase of the action research cycle. We were interested to determine if students were sharing ideas, debating opinions and building knowledge and whether their final grades were influenced by the online learning activities.

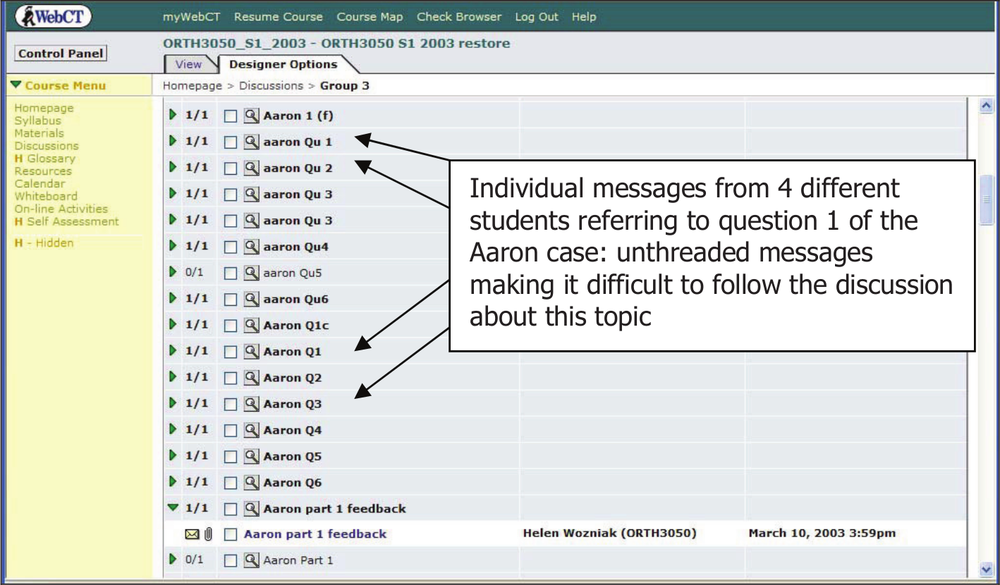

The content of 756 postings from 2003 were analysed using Salmon’s (2000) nine conference analysis categories which consisted of five categories that classified content as indicating individual thinking and four categories which demonstrated interactive thinking. It was found that the content of 93% of students postings were indicative of individual thinking where students tended to post their ideas as single messages rarely responding to contributions of other students by threading and building an online dialogue (Wozniak & Silveira, 2004). Examples of these types of postings are as follows with the category of individual thinking shown in brackets:

After working through the information I came up with the following… have I got this right? (Offering up ideas or resources and inviting a critique of them)

I agree that…, this is backed up by the reasons in previous messages, yes that’s what I got… (Articulating, explaining and supporting positions on issues)

The appearance of the discussion board supported this analysis, its appearance indicative of a long series of single messages with very few extended threads (Figure 15.3). 169

Figure 15.3. Appearance of discussion board in 2003

The influence of the online activities on other assessment results showed variable results. When the individual students’ mark for their online activities was compared with a final summative assessment in similar content areas there was a significant correlation in two out of the three comparisons. The first correlation of rs=0.474 (p<0.05) was found when an online case study mark was compared with a written exam-based case study mark where both assessments were evaluating a student’s understanding and interpretation of a clinically-based case. The second correlation showed a strong relationship between a mark derived from an analysis of a student’s online discussions about an orthoptic case and the mark that the same student gained in a practical, clinic-based examination of a patient with a similar type of ocular condition (rs=0.735 p<0.001, Wozniak & Silveira 2003). Clearly only limited conclusions can be drawn from such data considering the many influences that affect achievement in assessment activities. However these results did support a relationship between active participation online and student performance.

Reflection

Simply providing an online discussion space does not necessarily mean that it will be populated by lively discourse. The data collected above clearly demonstrated that students will not collaborate unless collaboration is structured into the activity, they tended to merely present their information without building on the thoughts of others. Other researchers have noted that full potential of the online discussion activities to promote greater collaboration and interaction between students was not often achieved (Dysthe, 2002).

To more carefully consider these aspects we drew upon other research investigating interaction between learners, teachers and content in both distance education and e-learning contexts. Garrison (1989) argued that an essential element for learning at a distance is dialogue and debate as these elements enable learners to negotiate and formulate their own meaningful knowledge. This has more recently been applied to 170online learning where Garrison, Anderson & Archer (2000) developed a conceptual framework that describes mechanisms for effective learning with computer mediated communication tools. They argue that a quality e-learning experience occurs when an environment is created that supports a community of inquiry through three essential elements; cognitive presence, social presence and teaching presence. We felt that our discussion activities had achieved the latter two attributes through the provision of a comfortable online environment with effective e-moderation. Further development was needed to address cognitive presence and promote collaborative higher order thinking and learning among our students.

This has been borne out in recent literature describing networked learning practices, showing that both the design of the task and the role of the moderator are critical to the success of the asynchronous discussion activity (Dennen, 2005). Goodyear, Laat & Lally (2006) highlight that providing ground rules, clear expectations about the purpose and role of the student and teacher in the activity will increase the likelihood of an active discussion board with relevant contributions made by all members of the group.

We were also influenced by the work of Salmon (2000), who using her experiences in moderating online discussion forums in the United Kingdom, developed a model of online learning and teaching. It describes five stages that the student moves through to become autonomous learners. Learners move through a process of initially accessing the online communication tools, socialising and sharing ideas, to constructing knowledge and finally self regulation and critical appraisal of their online learning. The model also details how the e-moderator should support the student as they move through each stage. It was with this background that we moved to planning our modifications to the discussion activities.

Action research conducted from 2004 onwards

Plan

Prior to the commencement of the 2004 academic year we redesigned the preparation activities to incorporate the ideas and reflections noted above. Salmon’s model was redesigned for an undergraduate student’s perspective and orientation activities were structured to scaffold effective online group participation. A reflection activity was also designed whereby students were surveyed early in the semester about their readiness for online learning which was reviewed and commented on later in the semester. The criteria for assessment of participation were also modified to mirror attributes of effective group collaboration. It included a student reflective report based on self analysis of their development as an online learner using Salmon’s model.

Implementation

In 2004 and 2005 three short orientation sessions were provided to the year 3 students who were new to the online discussion activities (see Wozniak, 2007 for full details). A modified form was also presented to year 4 students. These sessions outlined:

- an introduction to Salmon’s model of e-learning which we modified to show how students could scaffold their process of learning online in a collaborative group

- clarification of the purpose of the asynchronous discussions

- the role and moderation style of the e-moderator, and data available to them to track student participation 171

- the impact that ‘lurkers’ can have on group collaboration

- practice activities where students posted their ideas about a trial case which were then analysed by the students for timing, threading and cognitive level of their postings

- a reflection activity where students were asked to consider their previous online experiences and rate their current level of proficiency on Salmon’s model

- research results from the 2003 cohort showing the correlations between online assessment and exam marks.

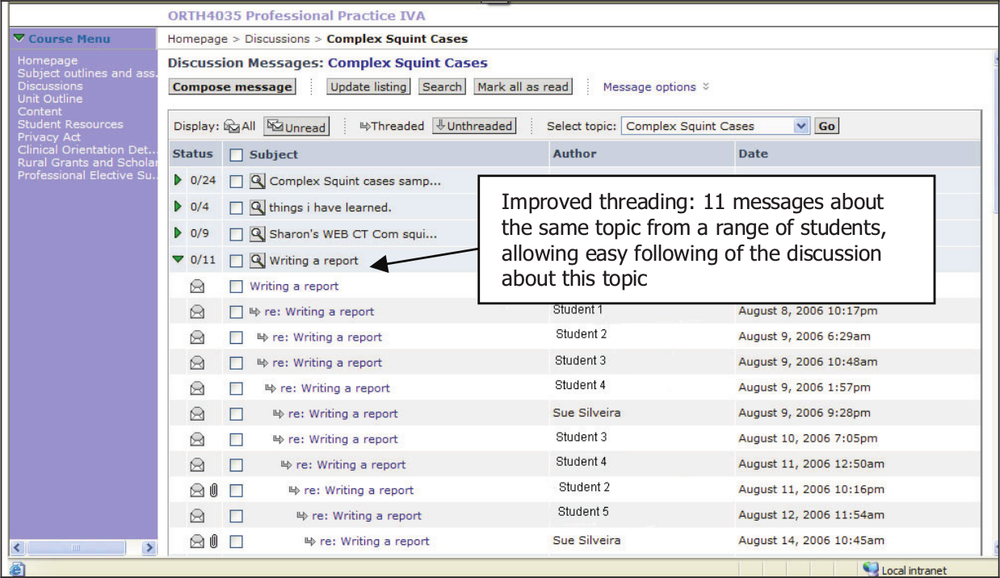

Observation

Since 2004 the discussion board appearance has dramatically changed. The 949 postings made in the first 6 weeks of semester of 2004 were analysed as described earlier and compared to those made in 2003 prior to the changes in preparation activities. Messages now appeared under clearly labeled subject headings with long threads showing multiple contributions from several students (see figure 15.4). A statistically significant difference was noted with 47% of the 2004 postings (as opposed to 7% of the 2003 postings) showing ‘interactive thinking’ where students critique, expand, negotiate meanings, summarise contributions or develop ideas based on their interactions (p<0.001). Examples of messages that illustrate these aspects of interactive thinking are:

Another point to consider is…; I thought Q1 was actually asking for…so maybe you could ask… I agree with your comments so far giving… (Offering a critique, challenging, discussing and expanding ideas of others),

Ok here is the group answers…gathered from what everyone has said and agreed upon, so the general consensus is that we’d use…because… (Summarising and modeling previous contributions).

Figure 15.4. Discussion board appearance in 2006

172With this distinct change in interactivity we decided to look more closely at whether there was a relationship between increased interactivity and other assessment results. Table 15.2 outlines the differences that were noted when the online case marks were analysed and correlated with the level of interaction noted after content analysis of the postings (Silveira, Wozniak & Heard, 2004).

Table 15.2. Changes to the assessment results after modified orientation sessions

| Assessment | Type of change | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Online case 1 |

Mean Mark increased from 2.25/6 in 2003 to 5.19/6 in 2004 | t=5.1, p<0.001 |

| Higher marks associated with more interactive postings | rs=0.76, p<0.01 | |

| Online case 2 |

Mean Mark increased from 3.75/6 in 2003 to 5.81/6 in 2004 | t=3.5, p=0.001 |

| Higher marks associated with more interactive postings | rs=0.69, p<0.01 | |

| Lower marks associated with less interactive postings | rs= -0.47, p<0.01 |

When analysing the student’s reflections about their participation and readiness for online learning using Salmon’s model, it was not surprising that the students’ development as online learners improved significantly over the duration of the semester. There was also a significant correlation between their self reported stage of development and individual online participation mark (rs=0.411, p<0.01; Wozniak, 2006). Students consistently reported that the online discussions were a positive experience encouraged by the timely feedback provided by their peers and e-moderators. A number of other factors may have influenced the changes that were observed in the students’ discussion patterns such as our increased experience in moderating online discourse, the introduction of other communication devices in the students’ daily lives such as SMS, and the fact that the student cohorts were different. Our research results do however, support the notion that online discussion activities have the capacity to improve the learning outcomes of undergraduate students.

We also noted that processes developed as a year 3 student, assisted their approach to online discussion activities in year 4. Students were able to drive the discussions, engage in peer teaching and self correcting behaviours. Another observation was that students who tended not to participate in the face-to-face situation were often the students who posted most frequently online. This behaviour has been noted by others and has been found anecdotally to transfer back to improved confidence in the face-to-face environment (O’Hara, 2004).

Reflection and planning for the future

Action research continues to influence our approach to online learning by revealing new issues and areas ripe for inquiry. Computer access constraints no longer influence student participation in line with overseas experiences (Kirkwood & Price, 2005). Over time we have spent much less time on these issues as a computer culture of online communication pervades the current generation of higher education students. 173

Whenever a new pedagogical strategy is introduced there is natural caution and perhaps a need to control on the teacher’s part. As our students became more exposed to online learning through our units and other units in their course they display willingness to take control, to lead discussions and express concern to the non-participators.

Recently an invitation was extended to clinical educators to join the online discussions, to showcase the environment to those members of the orthoptic profession who were largely responsible for clinical supervision of students. The value of additional professional opinion and experience was recognised and welcomed by the e-moderators. Interesting patterns emerged ranging from clinical educators who declined the offer to those who accessed the site but ‘lurked’ and did not participate, to those who embraced the experience and provided valuable input. This is similar to patterns described by Knowlton (2005) from passive participation to dialogic participation. Clinical educator participation continues and is recognised by students in comments such as:

it’s great for them to see how hard we work at our academic as well as clinical learning. (Year 3 student, 2006)

it really helps to continue my discussion with my clinical educator after hours when we have had an interesting case and we have run out of time to talk about them due to the next patient waiting. My friends also get the benefit of coming in on our discussion online as well. (Year 4 student, 2005)

Encouraging students to share their patient experiences in online discussion provides all students exposure at a more enriched level than purely accessing textbook cases. It can also enable students to express their fears and resolve their feelings through personal reflection about their patient encounters.

Conclusion

Over the past 6 years our journey into online teaching and learning has been challenging and enlightening, moving away from a technology focus to understanding the underlying pedagogy of e-learning. We have left behind the need to ensure student computer literacy and the need to control the learning environment. Our experience has shown that with careful consideration of both the preparation and structure of asynchronous discussion activities student group leaders emerge naturally and the focus of the discussion can reflect higher order learning and team work. We have learned to trust our students, to value and acknowledge their contribution. We now perhaps enter another action research cycle with the focus on how best to manage the information overload generated online in the time available to both our students and ourselves.

Levy (2006) reinforces this notion by stating that:

a key challenge in the networked learning context is the question of how to empower learners to engage actively and productively with the range of pedagogical, social, informational and technological resources that are at their disposal, as well as with a learning approach that may well be unfamiliar to them (p. 227).