14

A BRIEF, AN ISLAND AND A CHANCE TO ENHANCE DESIGN CULTURE

The obsession with patrimony, the conservation of a few scattered centres, some monuments and museographic remains, are just such attempts to compensate for the loss of social representation in urban architecture. Nonetheless they are all still in vain. These efforts do not make memory; in fact they have nothing to do with the subtle art of memory. What remains are merely the stereotypical signs of the city, a global signal system consumed by tourists.1

MARC GUILLAUME

1995

The fence was high then, high with barbed wire and large intimidating signs warning KEEP OUT. Cockatoo Island, a former convict gaol, had now become a prisoner. The Commonwealth Government had deemed the island unsafe, so they kept it packed up and out of reach; private not public. Deals were hatched behind those fences. Rumours that the Commonwealth Government was planning to sell Cockatoo Island circulated and gained currency. The possibility that a real estate developer driven proposal—the kind that was already transforming magnificent harbour sites into mundane generic housing—could be realised on Cockatoo Island became our motivating factor. How could a balance between public and private, commercial and community interests be achieved whilst maintaining the integrity of the island’s maritime past and the continuing working harbour?156

In 1995, in response to this condition, landscape architecture students from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) proposed an international design competition to elicit ideas from around the world about ways that the island could become part of Sydney’s public domain. This competition was part of a larger initiative by landscape architecture students: it sat within the Big Sky - Landscape on the Pacific Edge conference, a four-day event in Sydney that examined the role of landscape architecture within the region. Practitioners and academics from key centres around the Pacific rim - George Hargreaves — USA, Cristina Felsenhardt — Chile, Richard Goodwin — Australia and Kazuyo Sejima — Japan, were invited to give keynote addresses, delivering perspectives on design practices and cultural influences on their design processes.2

At the time, the School of Landscape Architecture at UNSW was undergoing change. The new structure saw the individual, autonomous Schools become Programs, which in turn formed the Faculty, many bodies sharing one brain. ‘Centralised’ was the term and greater efficiency and unity was the aim. The fires that had started were now being fanned by this student run initiative. It drew support from some staff, was watched with suspicion by others, and seen as an inconvenience to the rest. We were taken away from our studies, pursuing the cause with passion and explosiveness of incendiary devices.

Along the way, our cause attracted allies in Richard Leplastrier and Roderick Simpson, prominent Sydney architects; former Labor Party minister, Tom Uren, the man so beset upon by causes, and Jack Mundey, the man behind the green bans that rocked the building industry and helped preserve large parcels of Sydney’s public domain. We started to probe and discovered the Friends of Cockatoo Island.3 We attended meetings and gave presentations, heard stories and discovered historians collecting histories. We made covert trips in small boats to photograph, feel and see this place up close. Each visit made security guards on the island more vigilant. A letter from the Commonwealth Department of Defence informed us that “security has been doubled; more guards and more guard dogs.” We were onto something. The interest started to grow.157

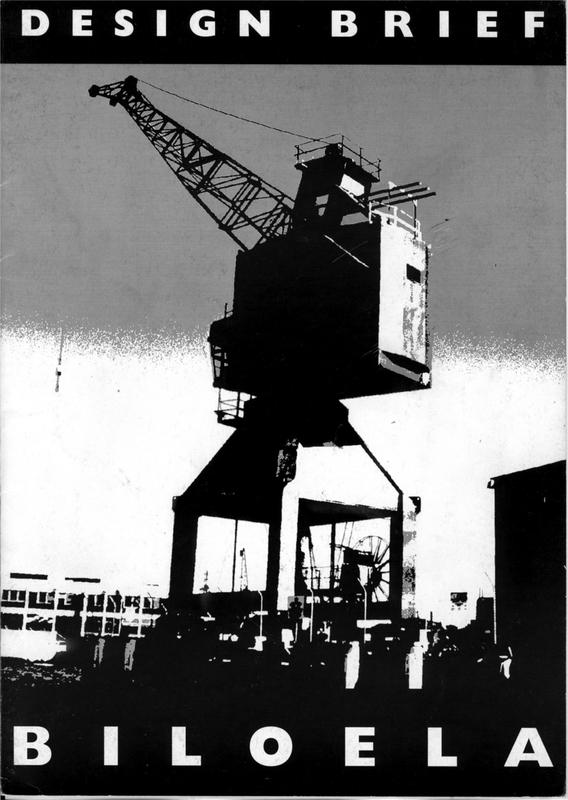

FIGURE 1B: FRONT OF BILOELA COMPETITION BRIEF158

BILOELA

An Island in a state of entropy – the spoils of an industrial age.4

The competition brief used the Aboriginal word for cockatoo, Biloela, the name used for the island in 1871 (Figure 1). It called for visionary urban design ideas: to consider the island’s history from servitude to shipbuilding, its contemporary state of industrial decay and its future role in the public domain. Primarily, it called for alternatives to selling Cockatoo into private hands. The agenda, in addition to returning the island to the public, was to highlight the dealings that the government was trying to keep invisible. The brief questioned the role of public space in the city. Sydney was being frantically redesigned in the run up to the 2000 Olympic Games. We asked: ‘What will become of Cockatoo Island?’

The Biloela competition was unique because it was run in its entirety, from conception to publication, by students. It sought to raise public awareness of the issues surrounding not only Cockatoo Island, but also other post-industrial sites along Sydney Harbour. Increasingly, predominantly real estate driven development pressures are infringing these sites, as they become the only vacant parcels of land available in Sydney’s urban centres. The prospect of a ‘new suburb,’ fuelling the already rampant privatisation of Sydney Harbour’s water edge seems, as Roderick Simpson notes, “…plausibly inevitable because it is so consistent with current urban consolidation policies for redundant industrial sites and with the chaotic but pragmatic shifts in use that have been Cockatoo’s history to date.”5

The competition attracted over 92 entries from Australia and around the world - including; Finland, Thailand, Mexico, Germany, Spain, Chile, USA and Singapore. The stage was set and the interest continued to grow. The jury was chaired by Richard Francis-Jones and included a Big Sky international speaker, Cristina Felsenhardt from Chile, keynote speaker from Sydney, Richard Goodwin and local landscape architects and academics Catherine Rush and Tom (Vladimir) Sitta. After deliberating the jury awarded the following:159

- First: Ross Ramus and 14 students from RMIT, Melbourne

- Second: James McGrath, Sydney

- Third: Mathis and Michael Güller and Markus Schaefer, Bern (Switzerland)

- Commendations: Jason McNamee, Melbourne & Richard Weller, Perth

The student conference, The Big Sky: Landscape on the Pacific Edge, provided the focus and the perfect forum for announcing the winners and providing debate. The jury formed a live panel in a packed auditorium, creating a sense of theatre (Figure 2). They announced and discussed the short listed schemes, via slides and then spoke to the schemes that they championed individually—a live critique—as they made their way to the winning scheme. The session also included talks about Sydney the Harbour City, by Sydney based architect Roderick Simpson and Professor James Weirick of the University of New South Wales.

FIGURE 2

THE JURY DEBATE ENTRIES OF THE BILOELA COMPETITION LEFT TO RIGHT: FELSENHARDT, SITTA, FRANCIS-JONES, GOODWIN, RUSH

The exhibition of the entries formed an important part of the competition 160process and the ensuing debate. It was staged as a three-fold event. First, and most importantly, all entries were exhibited as a complete set, anonymous and without any indication of the jury’s selected designs. Here the entire body of work produced in response to the brief could be viewed, unaffected by the jurors’ preferences.

The second showing occurred after the lectures by Roderick Simpson and Professor James Weirick, and the judges’ announcement of the finalists. It opened with the selected schemes brought to the front of the exhibition space with all names revealed. There is no doubt that this set a very different tone. More than just the celebratory nature and a sense of fait accompli for the competitors, one automatically viewed the other schemes differently, for now there was an ‘other’ — those that did not win. This provided a point of comparison and debate.

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly Wilderness

Surround that hill.

The Wilderness rose up to it,

and sprawled around,

No longer wild.6

WALLACE STEVENS

The schemes around the selected few seemed to differ. The worth, in qualitative terms, of the unordered pre-judgement showing of the entries of any design competition, lies in their purity. They hinted at the collective creative efforts of a cross-section (hopefully generous, though not necessarily representative) of the design community’s response to a design issue at a given time.161

The second showing, with the winning schemes set upon their pedestals, initiated the next equally, if not more potent phase of the competition process, as the masses attempted to either rock or re-affirm those pedestals through critical debate. This debate kept the essence of the Biloela competition alive long after the competition was judged and has since been produced in various magazines as well as internationally via the Internet and recorded on video, for posterity and educational purposes.

The first two showings were held on the UNSW campus, both on and for the duration of one day, primarily attended by The Big Sky conference delegates. For this reason, I decided to stage a third showing, more accessible to the public, over a longer period and at a more central public venue. The Lend Lease Group donated a space at the MLC Centre in Sydney as part of their commitment to urban design. Here, a showing of the short listed schemes and the finalists were mounted, along with the remaining entries on twin slide projectors.7 I felt it was important for the public to view all of the schemes, not just the selected few. This was a sign of the competition’s integrity, as it showed respect to all those who entered.

Approximately 300 people viewed, questioned and engaged with the displayed designs. Because of the controversial history of Cockatoo Island, particularly during the union action of the late 1980s and the incensed public reaction to the island’s closure in 1989, the debate was dynamic. Magazines took the stories and newspapers became interested. This was looking like a raw nerve for Sydney and for State and Commonwealth politics. The comments that were recorded reflect a range of responses from ‘Save the island – beautiful conceptual ideas’, to ‘Not realistic enough to convince the government or private sector for any practical actions.’ These comments are a vital element of the on-going debate.

Those people who viewed the schemes not only saw drawings for Cockatoo Island, but also became aware of the wider implications of development and privatisation of Sydney’s post-industrial landscape and harbour foreshore.162

ENHANCING DESIGN CULTURE

Biloela achieved many benefits of the type that enhance design culture through competitions. It had a very public profile: John Mant, the Head of the Premier’s Urban Design Task Force in NSW, announced the prizes. Other political party members attended, including the now retired Tom Uren, a staunch ally. Members of the media were present, so too were eminent designers, such as Richard Le Plastrier along with students and educators from around Australia and overseas.

The competition presented a strong duality. As an ideas competition, the unbuilt nature became an issue of content as the polemic nature of the island’s history and political pressures became more evident; Cockatoo Island was the typical hot potato. This condition is recognised by Richard Francis-Jones, the jury’s Chair, in the judges’ report, which reads:

The ideas competition for Cockatoo Island provided a great challenge to both entrants and judges, poised as it is between formal, theoretical investigation on one hand and the social, cultural, and political reality on the other hand. Bridging this gap is the powerful physicality of this carved and scarred rock at the heart of Sydney Harbour.

It is the classic duality of the ideas competition which at once provides an important opportunity for open theoretical investigation while also putting forward realistic propositions that challenge the political orthodoxy and positively contribute to the public debate over the future of a city.

Given this inherent duality, the judges regard the selected Prize Winning schemes as a ‘set,’ which taken together represent an outstanding response to the competition and for which the five Prize Winners are sincerely congratulated by the Jury.8

Roderick Simpson writes in the journal ‘Architecture Australia’:

As with all competitions, it is the elegance of an idea and its resolution that wins the day. Rarely are complex or ambivalent statements chosen. Instead the many directions available are represented through the curatorial selection of the jury.163

The five premiated schemes, which the jury considered as “a set,” literally, though unintentionally scoped Cockatoo’s history – with different phases providing different starting points for the various schemes’ trajectories: Weller, nature; McNamee, prison; McGrath, institution; Ramus, work place and Güller and Schaefer, the emerald city on the Hollywood axis.9

In ideas competitions, commonality of purpose, which produces vagaries in design approach, is what fuels the debate. This enhances design culture through vital discourse, and gives the specific issues longevity.

A competition system facilitates the lifeblood of a design culture in so far as it provides a regular forum for design work. It allows new people with various approaches to the problems of design to speak out and be heard.10

The 19th century philosopher, Kierkegaard, poignantly points out: “People hardly ever make use of the freedom they have, such as freedom of thought, and instead they demand freedom of speech.”11 The environment that encourages and provides the freedom to really ‘think’ is embodied in the intention of design competitions.

CREATIVE THINKING

Creative thinking is probably one of the most important skills a designer can have. It is the ability, as Edward de Bono describes, “… to visualise the path of thinking that you travel and to take off at any time to explore tangents, but still arrive back on that path if the tangent proves fruitless.”12

One of the most important aspects of creative thinking is the ability to understand, interpret and think about problems in different ways, not to be limited by our preconceived ideas of how we think things are or should be.13 Often a faculty of the young, creative thinking becomes harder to achieve as one works longer and longer in a bureaucratic system whose foundations lie in order, efficiency and a firm notion of ‘the way things should be.’ Boden describes creative thinking:164

To be creative is not enough for an idea to be unusual, not even if it is valuable, too. Nor is it enough to be a mere novelty, something that has never happened before. Genuinely creative ideas are surprising in a deeper way…our surprise at a creative idea recognises that the world has turned out differently not just from the way we thought it would, but even from the way we thought it could.14

Design competitions genuinely encourage creative thinking. Often briefs call for ‘visionary ideas’ and ideas that ‘challenge our perceptions.’ Individuals and groups who work on competitions in this environment of reinventing and challenging preconceived ideas will ultimately be more ‘switched-on’ and able to view a new perspective on design matters. Such fresh vitality and approaches will flow back through the office or school, influencing their peers and enhance design culture, both intellectually and through built projects.

POST BILOELA

Building on the debate initiated by the Biloela competition, we continued to use the body of work to gain public support. Activities, including lobbying the government, continued months after the competition. A petition was circulated which asked that Cockatoo Island not be sold into private ownership, but become part of Sydney’s public realm, with provision for commercial activity, and that the ideas generated by the International Design Competition, Biloela, be seen as valid future directions. In July 1995, Senator Vicky Bourne for the Australian Democrats questioned Senator Faulkner in a sitting of Federal Parliament about the present state of the Island. In November of that year, as a direct result of the Biloela competition and the subsequent lobbying, four design journal articles, radio interviews including a news item on ABC Radio National and public exhibitions, Australian Democrats senator Elisabeth Kirkby MLC presented an adjournment speech which raised the question of “the government’s intended sale of Cockatoo Island” and brought to the attention of Parliament the efforts of “the Friends of Cockatoo Island and the International Design competition run by the students of landscape architecture, UNSW.”

The influence of Biloela and the ensuing events on the government’s decision 165to return Cockatoo Island to the public realm and reverse their decision to sell, is not clear. Nevertheless, the pleasure of sitting in old timber drying sheds on Cockatoo Island’s uppermost plateau, with the sun streaming in, during the 2005 Easter Festival - 10 years and 6 months after the Biloela competition, with old allies Richard Leplastrier and Roderick Simpson, was something very special. The public had access to the island for the first time since 1992, and they flocked to it over that long weekend (Figures 3, 4 & 5).

A place like Cockatoo Island needs people and people need a place like Cockatoo.

The fences have now gone.

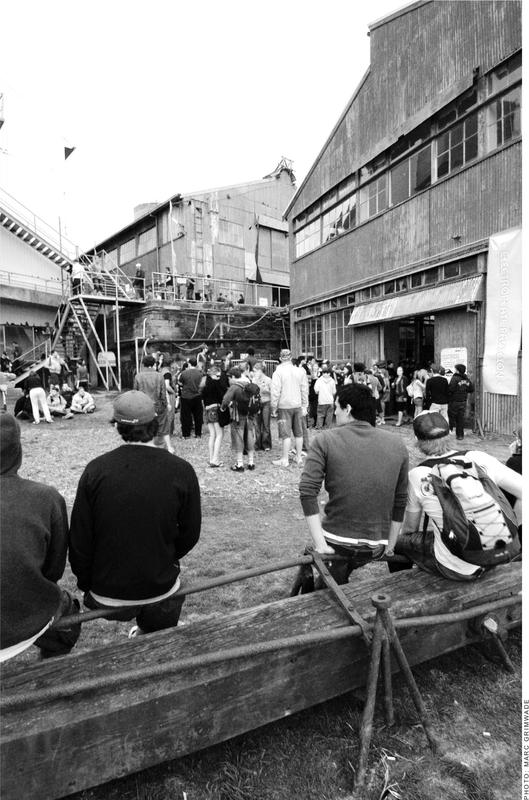

FIGURE 3

SPECTATORS ENJOY A PERFORMANCE AT THE COCKATOO ISLAND FESTIVAL IN 2005166

FIGURE 4: OUTSIDE THE ELECTROPLATE PAVILLION AT COCKATOO ISLAND FESTIVAL 2005167

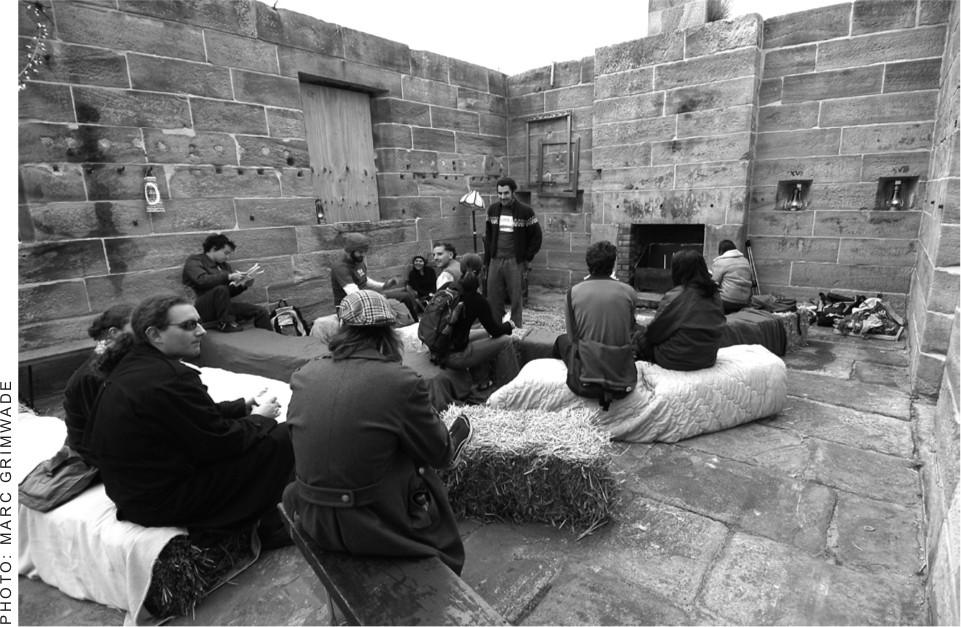

FIGURE 5

THE SPOKEN WORD AND STORYTELLING THEATRE AT THE COCKATOO ISLAND FESTIVAL 2005

1 Guillaume, M: 1986, L’Etat des Sciences Sociales en France, La Découverte, Paris.

2 The Big Sky: Landscape on the Pacific Edge conference continued a tradition of student run landscape architecture conferences established at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in 1992 with the Culture of Landscape Architecture: Edge Too Conference. At this time, the author was a student of Landscape Architecture at the University of New South Wales and organiser of the documented competition.

3 The Friends of Cockatoo was a community body formed to fight the privatisation of Cockatoo Island and bring it back to the public.

4 Biloela design competition brief for Cockatoo Island, 1995.

5 Simpson, R.: 1996, Edge Conditions, Architecture Australia, 85 (1), p.70.

6 Cited in Dixon, J.: 1991, The Garden as Cult Object, in Wrede, S. and Adams, W: 1991, Denatured Visions: Landscape and Culture in the 20th Century, Museum of Modern Art, New York, p. 19.

8 Francis-Jones, R: 1995, Biloela, Monument, 11, pp. 102.

9 Simpson, R: 1996, Cockatoo Island, Architecture Australia, 85(1), pp. 70.

10 Weller, R: 1996, Making Australia a Better Place in which to Live? Landscape Australia, 18 (2), p. 37.

11 www.wisdomquotes.com/cat_freedom.html

12 De Bono, E: 1993, Serious Creativity: The Power of Lateral Thinking to Create New Ideas, Harper Collins, London.

13 Moore, K: 1993, The Art of Design, Landscape Design, No.217, pp. 30.

14 Boden, M: 1990, The Creative Mind, Myth and Mechanism, Basic Books, New York.