07

A COLLAGE OF YEARNINGS

Cockatoo Island splices together ‘place’ and ‘space’ (the specific and the general), intimate and panoramic scales; the ‘force of action’ and the ‘repose of the sublime’; and (of course), ‘man’ and ‘nature.’ All of which inform the polar twins of memory and anticipation.

The lawns and the tennis court of the veranda-ed Overseer’s villa speak of a remembered distant Motherland, and of an affinity with that mother’s other far-flung colonial outposts – which could be reached, and defended from enemies, only by ships of the type pieced together in the vast industrial sheds overseen (but not overlooked) from this idyllic bungalow. This juxtaposition of these very different structures - the quaint villa and the immense Heavy-Workshops – is an eloquent expression of the simultaneity of the overwhelming, world-spanning sea-power of Britannia, and the romantic nostalgia of her imaginary, carefree, long afternoons of summer.

Opposition to Britannia’s expansion, in the case of this distant southern place, included not only the native people, but also the native land. The new townships of Australia were slashed into the harsh landscape – the natural vigour of which required savage subjugation. The lessons of the voyage to Australia – cutting through the worst seas of the world as they rounded Cape Horn – were applied to this equally turbulent inland. It was cut. Sliced. Carved.

Cockatoo Island was cut for the making of ‘cutters’ – the warships of the Empire. Cut, again and again, to make docks, and graving-docks, and dry-docks, and space for fabrication sheds, the island has been consistently treated as a ‘raw material’ 98to be re-composed at will. Throughout its post-settlement history it has been in a state of transition, bearing traces of all its pasts but having no specifically envisaged future or terminal ‘state of being.’ It has been permanently in ‘a state of becoming.’

In such a ‘genius loci,’ the only possible architectural response is that of indeterminacy – an architecture which, through its incompleteness, joins with the island in its yearning for ‘closure.’

However, almost by definition, architecture resists indeterminacy. The Classical languages of form and proportion on which both traditional and modern architecture have been based and have derived their meaning, have required adherence to rules, or codes. Even Mannerism, in both its historic and contemporary versions, has involved the breaking and/or distortion of codes, or their incompleteness – in which the codes are given emphasised importance by the fact of their absence. This void of this calculated incompleteness, in effect, ‘completed’ the composition.

Nor is there actual indeterminacy in that which might be considered the inverse of the formal concepts of architecture – the computer-generated ‘blob’ architecture of Greg Lynn,1 Kas Oosterhuis2 and others, which is generated from equally subjective and very specific algorithms (i.e. codes) which, essentially, differ from the codes of traditional classical architecture only in their results.

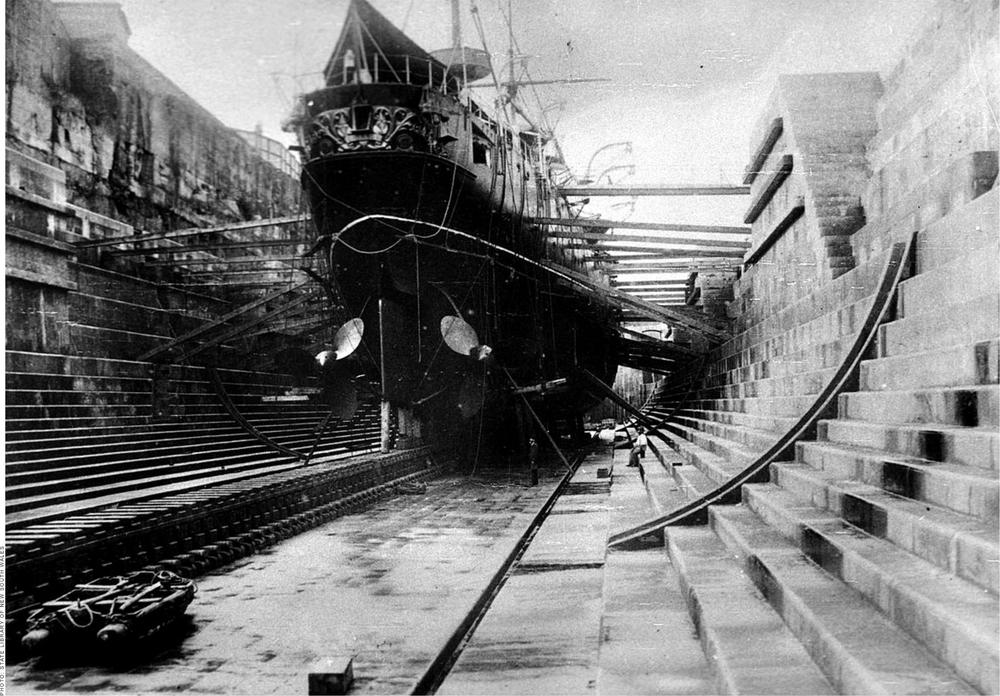

Interestingly, the form and fabrication of the ship hulls, seen in old photographs of the shipyards at Cockatoo Island, follow another determined language of code where “… the abstract space of design is imbued with the properties of flow, turbulence, viscosity and drag.”3 The hull curvatures were determined in response to the natural forces of the hydraulics with which the ships were obliged to contend. These ship-shapes resulted from the then current understanding of natural forces - forces beyond human will, beyond process, beyond aesthetic judgements and all notions of physical beauty. These forms were the products of the non-negotiable laws of nature, and - unlike those of blob architecture - were determined by human analysis but not by human intervention. Inherent in all 99design interventions is an at least partially envisaged state of completeness. These hulls, however, find completeness only in the partner for which they yearn and whose forces have given them their form – the sea. But, this relationship has ambiguity – do the hulls carve their form and volume into the surface of the sea, or do the forces of the sea – at least conceptually - carve the hull’s shape out of a generic block-form primitive?

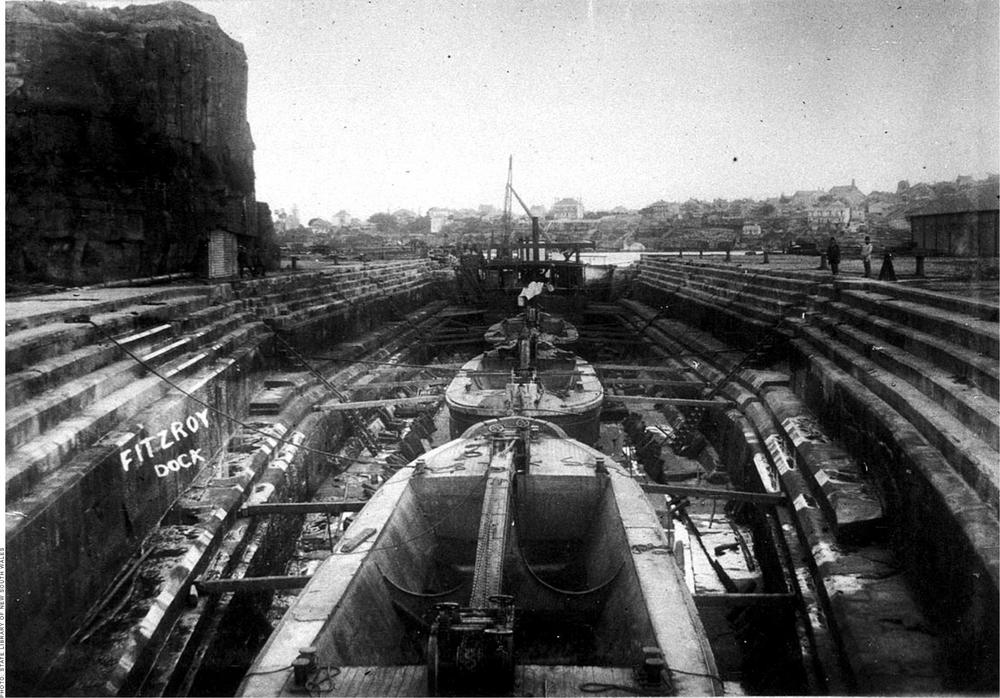

One finds a similar sense of reciprocity when considering the present landform of the island – which differs in all respects from its pre-settlement ‘whole.’ There is a reciprocity between the cutter and that which is cut. While the Sydney sandstone is of extreme softness, allowing the creation of vast geometrical incisions - such as the Cahill Expressway loop at Observatory Hill, which have the incomprehensible, almost metaphysical wonder of corn-circles – there is the question of whether the exploitation of the malleable characteristics of the rock is the acknowledgement and emphasis of its natural character, or the destruction of it. The cutting of the rock brings encounters with differing strengths and folds of rock strata, which require diversions and which make the planned locations and forms of all workings provisional. All the man-made cuts, in a sense, are the products of negotiations with the island’s physicality.

The future of the island must continue to result from negotiations with its physicality and with the many physical and programmatic evolutions of its past. As Crown land, and as a piece of working terrain valued only for its ease of use and for its isolation – not for its beauty or for the romance of its location – the island has always been, of necessity, subservient – and therefore immediately responsive - to changing needs, without regard for questions of design. The island has been, inadvertently, a graphic demonstration of Non-Plan – the superficially absurdist, but strictly serious theory of urbanism proposed in England in 1969 by the architect Cedric Price, the planner Peter Hall, the critic Rayner Banham and Paul Barker, editor of New Society, the journal in which Non-Plan was proposed, under the title An Experiment in Freedom.4

The argument of Non-Plan was that the segregation of civic, work, residential and entertainment districts which was – and essentially remains - fundamental 100to urban planning theory, resulted in a stultifying blandness of urban experience and the destruction of any sense of ‘civis,’ and the communal estate. The 1933 Athens Charter of the Congres Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), influenced by Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse project of the same year, committed CIAM to rigid functional cities, with citizens housed in high, widely-spaced apartment blocks, with green belts separating each zone of the city. It was a powerful vision, immensely influential on post-war urban planning. Against this, Price, et al, argued for the removal of all planning controls. As demonstrations, they conducted a ‘Non-Plan Test’ in which each took a section of the British countryside and re-visioned it blanketed with a low-density sprawl driven by automobility, with results that were clearly in no way worse than what had happened in equivalent districts developed under the usual planning controls. Non-Plan could, unsettlingly, be read, ambiguously, as anarchism or hard laissez-faire capitalism, but the lessons were profound, and led subsequently to the enterprise zones that were adopted at the London Docklands, and which led to the almost unimaginably rapid transformation of these abandoned areas.

HMAS ORLANDO IN SUTHERLAND DOCK, COCKATOO ISLAND, C.1870102

FITZROY DOCK, COCKATOO ISLAND, C.1888

104As a check to all things ‘planned’ or ‘structured’ or ‘logical’ and ‘commercially viable’ in the contemporary city, Cockatoo Island offers the potential for continued indeterminacy and variable response. Given the immense differences of terrain that exist cheek-by-jowl in such a small plot of land, the new architecture of the island can never be complete, uniform or coherent. It can only ever be contingent, and essentially provisional. Consequently, the island offers the unique possibility of a permanently-transitional urban prototype.

“The fundamental characteristics of Futurist Architecture will be obsolescence and transience,” wrote Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1914 in the Manifesto of Futurist Architecture, “Each generation will have to build its own city.”5 This was a notion extended in extremis by Yona Friedman in his 1957 proposition for a Program of Mobile Urbanism in which all institutions founded on eternal norms would be subject to periodic renewal – including marriage, every five years, and property rights every ten years. “The concepts determining life in society are in perpetual transformation,” wrote Friedman, and consequently:105

… the following are required: techniques which permit construction of temporary urban clusters conceived in terms of their periodic regrouping, according to necessity…techniques which permit movement of networks of water and energy supply, sewers and circulation routes…(and) these techniques must lead to utilisation of cheaper elements, simple to assemble and to demount, easy to transport, and ready to be reutilised.6

The Inter-Action Centre, in central London, built by Cedric Price in 1971 as an example, in miniature, of Non-Plan, examined the same idea as Friedman, being constructed as a system of structures, services and enclosures which could be endlessly re-arranged to provide for whatever functions and ways of use were wished by the local community. It had neither prescribed use nor meaning. And, in the 1990s, when attempts were made to place the Inter-Action Centre on the Heritage Register, for permanent preservation, the original idea was denounced by Price, himself, who argued that a building which is intended to be responsive to changing ways of use must accept its own demolition when it can no longer provide for the patterns of use of a changed society. Similarly conceived were the works of Price’s contemporaries and occasional colleagues, the Archigram group, who speculated in their Instant City project of 1970 on a prosaic, generic ‘Anytown,’ above which, one day, arrives an airship from which drops down ‘infonets,’ tent-roofs, seating and projection screens to transform the small municipality – instantly and temporarily – into a media-mediated virtual urban environment of the type which now, 40 years later, seems such a current conversation. In their international-competition-winning, un-constructed Features Monte Carlo project of 1969, Archigram conceived a vast underground chamber which, along with the open spaces above and around it, was to be ‘seeded’ with almost limitless possibilities by the provision of transformative mobile mechanisms and services – again, echoes of Friedman - the possibilities and purpose being limited only by the wit of the ‘imagineer.’ There were no rules, other than that there must be a state of constant change.

Such an embrace of the provisional is a challenge to the ‘order’ which is embodied in our notion of civilisation, and our ‘civilising’ of a place by our overcoming of its natural disorder - rendering it ordered, and therefore beautiful. A counter-argument 106 is found in Jean-Francois Lyotard’s interpretation of the ideas of the eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant, where it is argued that it is impossible for man to create beauty by his/her actions. Kant proposed that we can only consider truly, and purely aesthetic an artefact which may have a purposeful structure, but which has no practical purpose whatever.7 Consequently, since all things man-made, including art-works, have in them non-aesthetic practical aspirations, or embody ideas, or conventional or anti-conventional stylistic decisions, which are unrelated to aesthetics, only the beauty of nature – which has no additional agenda – can be considered aesthetic. As Remko Scha has written:

In the course of the twentieth century, the challenge (of Kant’s theory) has been taken up by many artists. Several artistic traditions have developed art-generating processes of some sort – processes which are initiated by an artist who does not try to control the final result that will emerge. Indifferently chosen readymades, chance art, ecriture automatique, physical experiments, mathematical algorithms, biological processes… artists imitating the blind mechanism of natural processes.8

As Sol LeWitt wrote, “The artist’s will is secondary to the process he initiates from idea to completion…the process is mechanical and should not be tampered with. It should run its course.”9 In other words, it is in the provisional and unreservedly responsive systematic incompleteness of the Inter-Action Centre, and of the island, that pure aesthetics – beauty – can be found.

The implications of change to a former, now-disused, industrial complex such as that of Cockatoo Island, and its potential relevance to the contemporary society, have been outlined by Peter Buchanan, who argues that the rush in every city to construct new cultural facilities such as the Tate Modern is part of the transition to the post-industrial city, and that this “… is inescapably obvious because so many are converted industrial premises, factories, power stations that are now museums and concert halls, or the headquarters of media corporations (producing intangible content rather than physical product.)”10 As factories were vacated because of the move of manufacturing to lower cost workforces in the developing world, ‘First World’ cities converted these factories to house services, the ‘creative industries’ 107and culture. Buchanan argues:

With globalisation First-World cities must compete for investment, skills and tourists by offering a high quality of life, including lavish cultural provision… Now globalisation is entering a new phase. Following manufacturing’s move to the developing world, an exodus is beginning of computer-aided mental work – software development, accounts and administration, call centres, even legal matters and medical diagnosis – all of them linear sequential (left-brained) skills. So, in the First World, the industrial and then the first post-industrial age – the information age – are already being followed by what has been called the Conceptual Age.11 This prioritises quintessentially human skills that the machine or computer cannot replicate, those involving such things as creativity, pattern recognition, meaning making, aesthetic discrimination, emotional responses and empathy, all part of and honed by what we commonly think of as culture.12

The current city of doing, Buchanan argues, “… is one of discrete and discontinuous functions dispersed in different locations (home, workplace, sports field) requiring different modes of behaviour (parent, employee, athlete or fan) dispersed in a spatial and experiential void.”13 The city of the Athens Charter, he argues, “… with its zones of monofunctional buildings, free-standing in a void of fluid space and connected only by vehicular roads,”14 was “… a machine for avoiding the chance encounters, complexities and contradictions that lead to self knowledge and psychological maturation.”15 In the emerging city of being, however, “… there is an emerging concern with the subjective, experiential and meaning-seeking dimensions of being that were downplayed by modern planning and its utilitarian architecture. In short (there is an emerging concern with) making cities better places in which to be and become.”16

As a place that has been permanently ‘in a state of becoming,’ the Island anticipates the city that Buchanan foresees. The island has never been zoned, and is an example of myriad contrasting functional and spatial characteristics, histories and architectural types – that which is burrowed and that which is assembled – which Gottfried Semper describes, respectively, as stereotomic and tectonic space17 – the two fundamental material methods of creating space in architecture.18 In contrast 108to such as the Museo Guggenheim Bilbao – an architecture which seeks to suggest the casualness of naturally-occurring organisms or mineral outcrops, the sandstone of Cockatoo Island has been carved into explicitly man-made forms, and no clear lines have been drawn between that which is artificial (man-made) and that which is naturally-formed, or between that which is permanent and that which is temporary. It is a hybrid. Appropriate as a test-bed for a future which Bucanan, above, suggests will be essentially hybrid. It is a ‘terrain vague’ – a place whose purpose is ambiguous or undefined, described by Kate Fielding as:

… forgotten, waiting, off-limits, these sites mark the ‘wildness’ within an urban setting, which spasms with new construction and development. Such sites are wild not because they are ‘untouched’, but because they fall outside the definition of metropolis as productive, industrial and expanding. They are important for their potential — not in the property-development sense — but as available space for the possible dreams and activities of people who would never get (or necessarily want) the chance to own and develop space in a conventional way… Most advocates of the terrain vague, academic and otherwise, point to the crucial function of these wild places as spaces for the imagination, for roaming, for exploration.19

Cockatoo Island is simultaneously a place of memory and anticipation, issuing a provocation to the metropolis that surrounds it – challenging its stability, its ambitions, its values and relevance.

1 Lynn, G: 1999, Animate Form, Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

2 Oosterhuis, K: 2002, Architecture Goes Wild, 010 Publishers, Rotterdam.

3 Op cit. P.

4 Barker, P (ed), Price, C, Hall, P and Banham, R: 1969, Non-Plan – An Experiment in Freedom, New Society, 20 March 1969. See also: Barker, P, 1999: Non-Plan Revisited : Or the Real Way Cities Grow, Journal of Design History, 12(2) Summer 1999). And in: Hughes, J and Sadler, S: 2000, Non-Plan : Essays on Freedom, Participation and Change in Modern Architecture and Urbanism, Architectural Press, Oxford.

5 Marinetti, FT: 1914, Manifesto of Futurist Architecture. Quoted in Ockman, J (ed):1993, Architecture Culture 1943-1968, Rizzoli, New York.109

6 Friedman, Y: 1993, Quoted in Ockman, J (ed), Architecture Culture 1943-1968, Rizzoli, New York, pp. 274.

7 Jean-François Lyotard, JF: 1989, Die Erhabenheit ist das Unkonsumierbare. Ein Gespräch mit Christine Pries am 6.5.1988., Kunstforum International, 100 (April/May), pp. 355-356.

8 Scha, R: 1992, Towards an Architecture of Chance. On-line: http://iaaa.nl/rs/wiederhaE.html (accessed 4/12/2006)

9 Sol LeWitt, S: 1969, Sentences on Conceptual Art, Art-Language, 1(1) (May 1969). Reprinted in: Meyer, U (ed): 1972, Conceptual Art, Dutton, New York, pp. 174-175.

10 Buchanan, P: 2006, From Doing to Being, Architectural Review, 220 (1316), pp. 44.

11 Pink, DH: 2005, A Whole New Mind: how to thrive in the new conceptual age, Cyan Books, London. Referenced by Buchanan.

12 Buchanan, P: 2006, From Doing to Being, Architectural Review, 220 (1316), pp. 44.

13 Ibid. pp. 45.

14 Ibid. pp. 44.

15 Ibid. pp. 45.

16 Ibid. pp. 45.

17 Fielding, K: 2003, Spinach, 7(1), http://www.spinach7.com/magissue01/story-exploring-the-terrain-vague.html (accessed 4/12/2006).

18 van de Ven, C: 1978, Space in Architecture, Van Gorcum Assen, Amsterdam, pp.5.

19 Fielding, K: 2003, Spinach, 7(1), http://www.spinach7.com/magissue01/story-exploring-the-terrain-vague.html (accessed 4/12/2006).