PREFACE

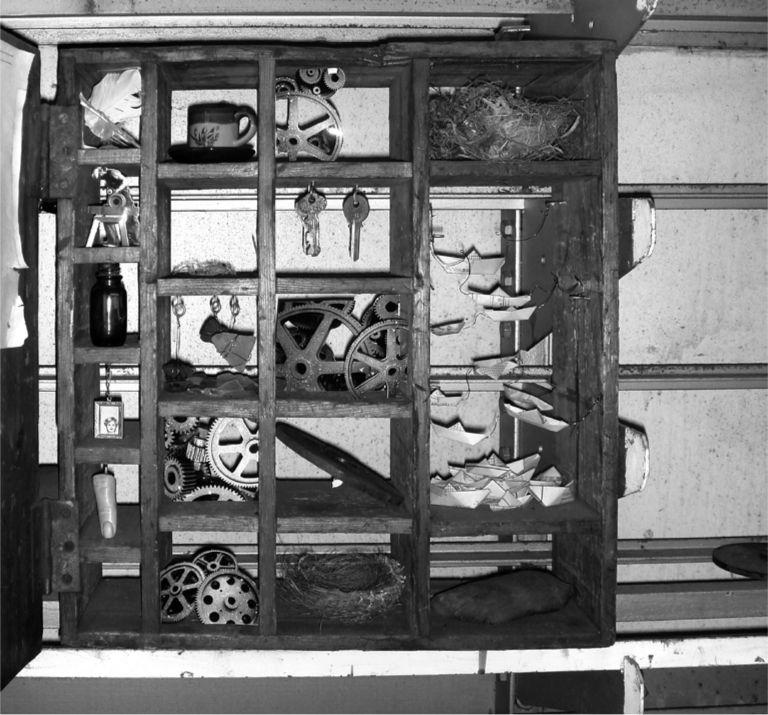

Describing Cockatoo Island as a post-industrial site is a little like examining a Joseph Cornell box and not noticing its contents. Without taking the analogy too far, for many Cockatoo Island stands as an empty shell, an echoing reminder of old uses, whether as a convict prison or shipbuilding yard.

Take a look inside the box and your imagination takes flight.

Cockatoo Island is all the things described in the Trust’s comprehensive plan: Sydney Harbour’s largest island, formed by natural forces long ago, occupied by Aboriginal people for thousands of years and over the past two centuries dramatically adapted by the colonial masters of New South Wales and later the Commonwealth Government.

The history of the island is undoubtedly part of its attraction. A more potent force in imagining its future is the possibility of creating something truly unique.

What’s the goal? Nothing less than a site as emblematic of the city as the Sydney Harbour Bridge and the Opera House. Being an island in one of the world’s great inhabited harbours is a good start. What else? Free public access is a must. So too an eclectic array of businesses from maritime operations to artists’ studios to form the island’s population base. And people, tours and events daily to sweep the aprons, docks and precincts with colour and life. Park benches. Camping. Night life. Stories. Noise.

The glue, however, is the indefinable, unorchestrated collaboration between what’s there and what’s in people’s heads; the interplay between expectations and experience exceeding expectations. A day at work and a day full of surprises.xv

A SMALL BOX OF CURIOSITIES FOUND ON COCKATOOISL AND SUGGESTS THE CREATIVE PASTIMES OF ITS SHIPPING WORKERS

The Trust’s plan for Cockatoo Island refers to step by step re-occupation. This is simply good sense and wise management. There are limited resources with which to upgrade infrastructure and remediate the building stock. At the same time, there is scope for risk taking and trial and error; the opportunity to seed exciting initiatives in business and the arts; to explore partnerships with the city’s cultural institutions; to think big and to think under the radar.

The research articles and design projects in this book consider how post-industrial sites may be used as templates for new ways of energising cities with cultural activity. The Urban Islands Project on Cockatoo Island is a pointer to the possibilities.

GEOFF BAILEY

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, SYDNEY HARBOUR FEDERATION TRUST