04

SOFT ARCHITECTURE / SOFT URBANISM

THE PARADIGM SHIFT IN ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN DESIGN CAUSED BY MEDIA TECHNOLOGY

I would like to discuss here again the relationship between architecture and urban design. During the Modern movement, architecture was considered to be part of urban design. Urbanism was proposed as a general theory, applicable to several different scales and architecture was considered one of them. Buildings and cities have in common the fact that they are both physically built, resulting in a continuous space. A number of theories were possible based on this approach, framing the way urbanism was proposed by both urban designers and a number of architects. Architects usually experience designing buildings first, before designing cities. But Modern architects often found it necessary to explain even their smallest works within the context of a certain urban theory. For them, architecture as ‘part’ always predicted the ‘whole,’ that is, the urban condition that would derive from it. In this way, they imagined scenarios where ideal cities could become reality through the widespread application of their proposed architectural systems. ‘Architecture as part / urbanism as a whole’ was the typical relationship between architecture and urbanism established by Modern architects, closely linking them, in theory. Both could be built through ‘planning,’ and the planning of architecture / urbanism was presented as a way to materialize the continuous spaces of buildings and cities.

In this way, the failure of the Modern movement has been frequently linked to the limitations posed by functionalism in architecture. But in reality, weren’t the urban theories, so closely linked to architecture, also a failure? Most of the ideas presented by Modernist urban designers were conceptual ‘planning’ proposals of 44ideal cities. The real cities charged with real problems lay just in front of them, but as a separate entity. However cleverly stated, the idealistic urban theories could not fit into the real city and were in fact rarely realized. This resulted in many gaps between the remaining pre-modernist buildings within the city. We could call them ‘Modern urbanism gaps,’ which can still be observed in several cities around the world. They were the result of the collapse of Modern urbanism, which was in turn caused by the belief that architecture and cities could be continuously planned, and in following, the failed attempt to realise this concept. It was the collapse of the concept of planning.

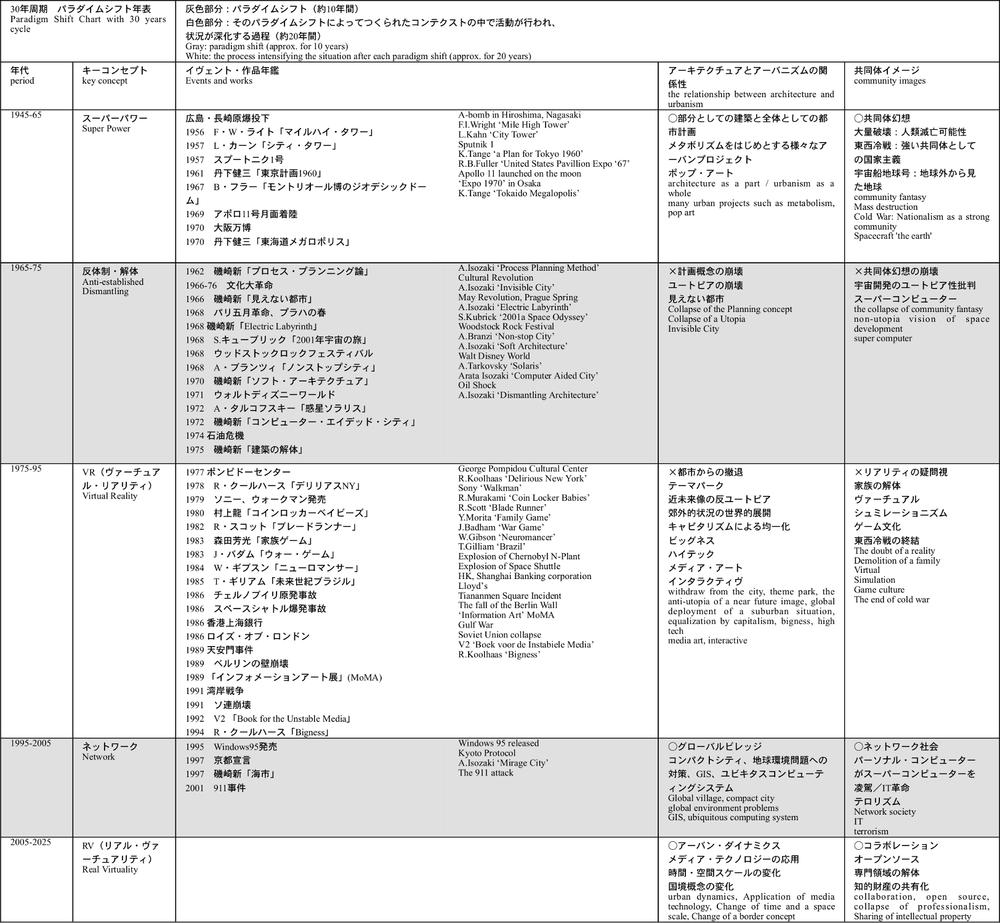

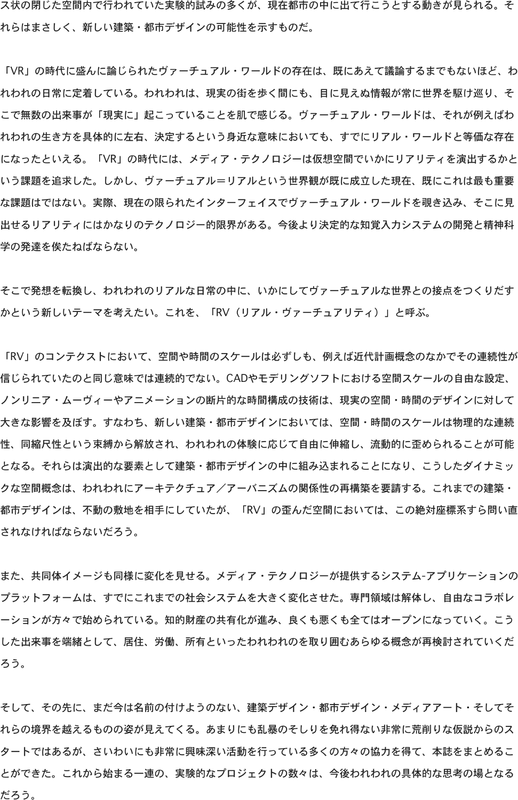

45Architecture and urbanism are profoundly linked to the collective images of their societies. The chronological table that follows (Table 1) establishes the relationship between architecture and urbanism, with collective images represented in key words, for determined periods of time. The grey sections represent periods of paradigm shifts, which can be estimated to have lasted for about ten years each time. The white sections show the activities exercised within the context built by the preceding paradigm shift periods, and the process of intensification of the conditions previously set. These periods lasted for about twenty years until the next paradigm shift happened. Therefore in a span of thirty years, shifts from one paradigm to the next occurred, greatly changing the conditions of architecture and urbanism. It is within this perspective that I would like to continue the present discussion. Some events and works listed could not fit exactly within the ten-year-shift period, therefore they were placed according to their meanings and resulting impacts.

The abovementioned ‘collapse of the concept of planning’ can be confirmed in the period of 1965-75, which I call the ‘anti-establishment/dismantling’ period. When the notion of planning collapsed, the changing conditions caused the rejection of old collective images, for example the idea of nationality. In other words, the concept of planning collapsed simultaneously with the destruction of an old, single, collective illusion. Roughly speaking, the anti-establishment - dismantling period of 1965-75 marks the increasing distance between architecture and urbanism. The planning concept in use until that time was destroyed and the number of proposals based on the idea of buildings and cities as one unique body 46 radically decreased. In Japan, according to architect Arata Isozaki, architects were inclined to adopt a ‘withdraw from the city’ attitude,1 while in urbanism the ‘invisible city,’ which can exist without traditional notions of planning, was the basic concept of the period.

TABLE 1

CRONOLOGICAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ARCHITECTURE AND URBANISM48

49Then at least until the period of 1975-95, from the point of view of the relationship between architecture and urbanism, and of collective images, most architectural production took place within the paradigm established during the anti-establishment/dismantling period. For the present discussion, I will call this period ‘VR’ (virtual reality). During this period, the distance between architecture and urbanism increased. Following capitalist trends, suburban developments and theme parks with no relation to their surroundings became widespread in cities around the world. Theories on Manhattan such as Delirious New York2 or Bigness3 pointed out the fact that the act of designing architecture and cities was powerless within the capitalism system. Nevertheless, they were irresistibly persuasive as writings that so well acknowledged the period’s situation. The collective image of this period - the break up of the family concept, the realities of the individual existence, the problem of identity, etc. (all characteristics of the anti-establishment/dismantling period) - became even stronger. Questions like invisible communities of invisible cities, or how the individual who lost his/her identity within the giant metropolises should exist, were more frequently asked.

Nevertheless, for the present discussion I would like to focus on the last paradigm shift, from 1995 to 2005, which corresponds to a new movement that might be happening just at the present moment. To start with, I will call it the ‘network’ period. With the release of Windows 95 providing the necessary momentum, social systems became more dependent on the Internet and networks, with the personal computer as their main tool. In addition, most developed countries faced a new social condition with an overall economic slowdown, low birth rates, ageing societies, and environmental problems – all demanding solutions. This led me to think that the relationship between architecture and urbanism might become questionable again, together with the search for a new collective image order; this is the hypothesis I propose here, or in other words, that a new paradigm shift is happening.50

51I would like to go back now and explain the meaning of the title soft architecture/soft urbanism. Soft architecture is a concept presented by Arata Isozaki in 1970.4 Soft urbanism was probably presented as an equivalent theory in the field of urban design by Hajime Yatsuka in the 1990s. Both concepts emphasized the necessity of incorporating ‘software’ into the future city, in addition to the ‘hardware’ or constructed elements that were more easily identifiable with architecture and city design practices. These ideas tried to revolutionize the former concept of architecture and city planning and can be summarized as follows:

In other words, the incorporation of software in architecture will increase the proportion of its intangible aspects, and activities will be carried out according to the new environments determined by the media. Moreover, the spread of these activities around the whole city would make architecture and city become one single entity, architecture dissolving itself within the city. In other words it will be possible to say that architecture will become the city and the city will become architecture. The great challenge will be planning and designing this new environment city = architecture.5

ARATA ISOZAKI

The computer systems at that time still used perforated cards as recording media, which are unimaginable and primitive nowadays. Of course these systems were insufficient as the technology to support his theory, therefore making Isozaki’s foresight all the more impressive. In fact, the futuristic image of a computer at that time was a giant super computer and in the Computer Aided City project6 proposed by Isozaki, computers were absolutely necessary elements connecting the city. Unfortunately, as a consequence of this media technology delay, the soft architecture theory could not be developed and given a concrete form by Isozaki. However, by going back to this theory we are now able to see that it applies concepts from Isozaki’s Process Planning Theory7 and Invisible City8 and that it probably had good chances to develop into a design theory not detached from reality.

Kumamoto Artpolis9 is a concrete, practical example of soft urbanism in which the concept is perhaps too dominant; although it set out to discuss soft urbanism and soft architecture simultaneously, it simply ends up dropping the relationship.52

53There is a reason why I keep bringing back these two phrases - soft architecture, soft urbanism - to the present discussion. As a consequence of the paradigm shift occurring in the network period, the once distanced position between architecture and urbanism seems to be closing in once again, prompting me to revisit the question of their present relationship.

In contemporary times, thanks to media technology, the possibilities in architecture and urban design have greatly improved. We are part of a generation provided with unprecedented individual and group frameworks, integrated by means of information transmission and speed, capable of operating and organizing many elements all at once, and supported by rapidly improving media technologies, which all allow us to aspire to a new freedom for the city as a living organism.

Thematically and technically, architecture and urban design have usually been considered as academic activities, but recently they have been naturally attracting professionals from several areas, indicating some important changes to be carried out from this field. In arts and science, experiments that previously took place within box-shaped, enclosed spaces like laboratories, galleries and theatres have recently been occurring in city spaces, in a growing trend. This fact represents precisely the new possibilities for architecture and urban design that I am talking about.

During the VR period, discussions about the existence of a virtual world were frequent, but nowadays this virtual world has become so much part of our daily life that it makes no sense to talk about it anymore. While we walk around the real city, information that can’t be seen with our eyes is continually running around the world and at the same time there are countless ‘real’ things happening that can be sensed physically. If this virtual world can concretely influence our lives, such as on a simple personal decision to go left or right, then we can say that it is already equivalent in importance to the real world. In the VR period, the main challenge posed to media technology was how to produce reality in virtual spaces. But in a world where virtual = real, as we have it in the present, this is not an important question anymore. In fact, we now look at the virtual world through limited interfaces and therefore the reality we find there presents some 54considerable limitations in terms of technology. From now on we can only look forward to decisive innovations in interface systems and new developments in the cognitive sciences.

In this way, we could change our way of thinking and somehow start to create links between our daily lives and the virtual world. This is the new subject I want to think about. I call it ‘RV’ (real virtuality).

For example, within the RV context, the continuity of time and space that was adopted in Modern planning has no correspondence in contemporary circumstances. The freedom of space and scale offered by CAD and modelling software and the fragmented time structures of non-linear movies and computer animations, has strongly influenced the design of real space and time. That is, new architectural and urban designs can be freely imagined; released from the physical restrictions of the conventional time and space structure. It is now possible to stretch and twist them freely in a fluid manner according to our personal experiences. As they are incorporated into architecture and urban designs as fundamental elements, the resulting dynamic spaces make us reconsider the relationship between architecture and urbanism. Until now, architecture and urban design used to deal with immovable, real sites. However in the space deformed by RV even the use of these types of absolute coordinates should be questioned.

Likewise, changes can also be seen in the collective image of this period. The system applications platform supplied by media technology has already caused numerous changes in the present social system. The technological domain has been reorganized and collaborations have started taking place freely. Intellectual property has been increasingly shared and for good or bad, everything has become open. Starting from these events, all our usual concepts of residence, work, property, etc., might be re-examined as well.

Then, we can start to see something we cannot name yet, something that is beyond architectural design, urban design or media art. I have started from a very rough hypothesis, which may well attract criticism, but fortunately, with 55the collaboration of numerous people, the emergence of projects and discussions within this undefined space is generating increasing momentum.

SOFT ARCHITECTURE, INSTALLATION BY RESPONSIVE ENVIRONMENT

1 From a discussion with Arata Isozaki in 2002.

2 Koolhaas, R: 1978, Delirious New York : a retroactive manifesto for Manhattan, Oxford University Press, New York.

3 Koolhaas, R and Mau, B: 1995, SMLXL, 010 Publishers, Rotterdam.

4 Isozaki, A: 1970, Soft Architecture as Responsive Environment, Kenchiku Bunka (Architecture Culture), January 1970.

5 Ibid.

6 Isozaki, A: 1972, Information Space, Kenchiku Bunka (Architecture Culture), August.

7 Isozaki, A: 1963, Process Planning Theory, Kenchiku Bunka (Architecture Culture), March.

8 Isozaki, A:1967, Invisible City, Tenbo (Prospect), November. http://www.pref.kumamoto.jp/traffic/artpolis/english/links/artpolis.html (accessed 1/12/2006)

9 1996, Soft Urbanism: 15 Projects, Inax Publishers, Tokyo.