09

Systems of Change, Reality and Revelation

Program matters more than we expect!

Sydney presents itself as a vital place offering one thing in particular, alongside the monuments (opera, harbour bridge and museums) - a heightening of senses. As a city with a lively nightlife, various creative scenes and multi-cultural environment, it holds all the tickets admired in cities like New York or London. Sydney as a tourist destination does not just present images; it offers locations, specific urban milieus, and atmospheres representing the nodes within a network of metropolitan conditions.

These atmospheres are hardly readable in an image; they are experienced rather than read. Atmospheres do not succumb to classification, like typologies, functions or characters. They are much more embedded in the urban context and in subtle transformations. Atmospheres appear and fade away as a result of both organised circumstances and things we cannot control. That is their quality.

Atmospheres are strong and sensible, changeable and massive, specific and mobile, impressive - but also transitory. The design of atmospheres could extend the definition of ‘program’ in architecture.

123Architectural program should exploit a place to develop concepts that form extraordinary atmospheres. It can be more than just a functional device.

Modernism used the independent terms ‘form’ and ‘function’. The facts of function often became a primary issue for the production of form. It’s time expand the definition to include the informal and alternate sources for architecture.

Just as narratives or diagrams are clever manipulations of interpreting an existing environment, architectural program has already consistently extended beyond its historic understanding. Away from the form/ function device, program offers a combination of styles and new collective associations in architecture. As a local fragment of a social pattern, program constitutes the matter of architectural form because it alternates between an evocation of arrangements and a transition between contexts.

As the future increasingly becomes alien and new to us, the more we seek continuity and history to take with us. Today’s world heightens both the tempo of innovation and the need to cultivate slowness. On the one hand, more is forgotten and thrown away than ever before, but on the other hand, more is remembered and stored more respectfully than in the past. Globalisation and universalisation are compensated by regionalisation, localisation and individualisation.124

Conversion and conservation should not be understood as just oppositional strategies, but as matching approaches in a rapidly changing global society. This seems to me essential if heritage is to be understood as authentic territory, authentic to our identity. Individualisation, privatisation and ‘auratisation,’1 now shape our relation with the built heritage. More and more frequently the value of a heritage building derives not from its former function or social significance but from its possibilities for individual auratisation and socio-cultural recording. Any kind of heritage can acquire significance today if it is no longer interrogated about its value as a historical artefact, but is used above all as a symbolically charged projection screen for itself or for a specific group.

The fact is that, liberated from the burden of historical knowledge and its fixed codes every heritage today can be interpreted and transformed by anyone as raw material that is available and changeable at will. History has become a very soft location factor, freely open to interpretation. This factor can be highly significant economically on the level of attracting tourists.

ARCHITECTURE OF PLEASURE

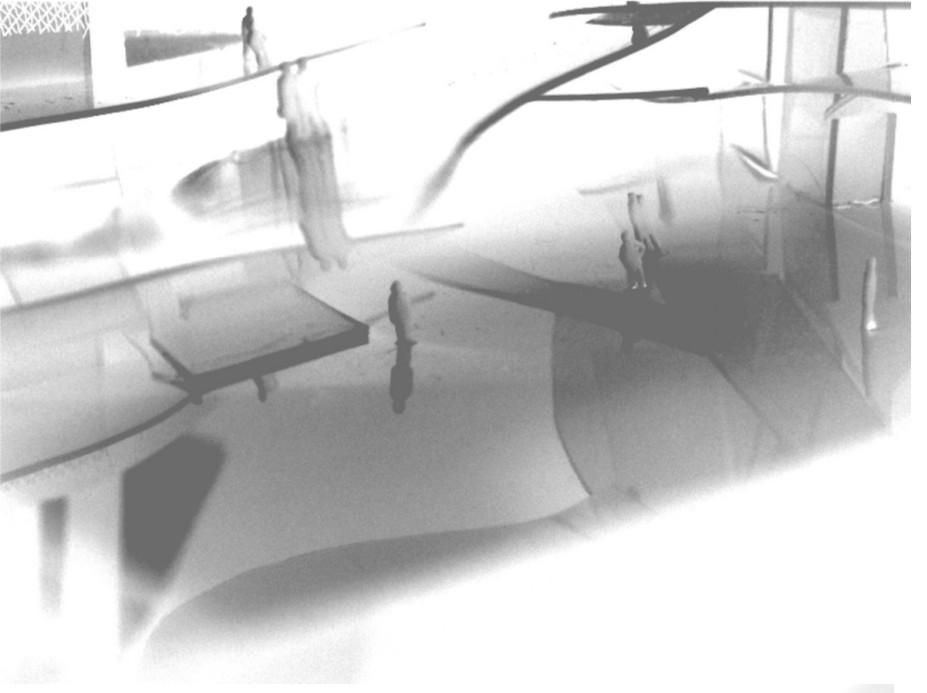

125Cockatoo Island is overloaded with this kind of raw material waiting for interpretation. Once a prison, a reform school and shipyard, the island could be apparently a miniature city that deals with atmospheres, motion and ambient spaces. There could be a breath of a unique urbanism predicated on a future that includes tourist interests. Cockatoo Island could be animated and networked by a strategic system of change, reality and revelation.

1 To create an aura is a process of detecting the particular uniqueness within the context of a place or history. In German this is called ‘auratisation’. It is based on the aesthetic theories of Adorno and Walter Benjamin.