5

Participation, young people and the Internet: digital natives in Korea

Introduction

The significance of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) has become critical in every facet of contemporary life and work. The coming of the Internet was no longer than two decades ago, but it has become a vital technology for all generations. Similar to the current trend towards ‘the visual extravaganza’ by newspaper and television (Barnhurst, 1998: 202), the Internet offers and utilises visual effects in an interactive and dynamic fashion. Moreover, individual users of the Internet are greatly empowered by the opportunity to participate interactively in public debate by airing their views online. Such an opportunity has brought about new avenues for citizens to participate in civic activities and influence political affairs and parties. Undoubtedly, the ways people use the Internet vary depending on their socioeconomic status and the generation to which they belong. Furthermore, the increasing penetration of the Internet opens up new avenues for political parties to attract public attention, especially when young people are increasingly losing interest in most news and information media, whilst gaining significant interest in the Internet (Barnhurst, 1998: 204).

In this chapter we examine how the Internet has affected the public and political participation of young people. We present two case studies where groups of secondary school students from South Korea have appealed to their basic human rights in order to influence policy decisions that had the potential to reduce their quality of life at school. The cases are indicative of the kind of opportunities available to develop innovative ways of participating in the political process. It is a common assumption 99that young people’s increasing preoccupation with computers and the Internet has resulted in their loss of interest in social and political affairs. These two case studies, however, from a country that enjoys the most advanced Internet infrastructure in the world, demonstrate that this common perception is an inaccurate generalisation.

In the next section, we review studies on the impacts of computers and the Internet on the political participation of younger generations. This is followed by a description of Korean society characterised as ‘the Internetworked society’. The two case studies are then examined, followed by a discussion of their main implications. We conclude with an assessment of the wider implications for politicians, policy-makers and civil society activists and provide suggestions for further research.

Whither civic participation in the Internet era?

Researchers have questioned whether online communication by the so-called ‘digital generation’ would sustain local networks or develop more distant relationships between people. It is a common perception that technological advancements, in particular computers and the Internet, have led to young people losing interest and initiative in participating in politics and engaging in social activities. For example, at home, the younger members of the family can often be found in their rooms, surfing the Net, and chatting and playing games online. Their preoccupation with ICTs and their close connection with members of the virtual world or cyberspace (i.e. online communities) the argument goes, may have the effect of depriving young people of face-to-face interpersonal skills required for interacting with ‘real’ members of society (i.e. ‘offline’ communities). As a result, young people tend to be complacent within their virtual world and become citizens indifferent to political participation.

Such observations are championed by Robert Putnam (1995, 2000), who blames TV as the main culprit of the marked decline 100in civic engagement in the United States. Putnam (1995: 67) argues that there has been a significant erosion of civic participation – an essential part of the liveliness and robustness of American society – or social capital. In his words, “features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate co-ordination and co-operation for mutual benefit” decrease due to high engagement with TV. This argument could apply equally to the effects of the Internet.

Recent studies, however, show that a decrease in social participation cannot be attributed solely to the prevalent use of the Internet. Livingstone et al (2005) argue that young people are using the Internet for a wide range of activities that could be considered participatory. They suggest that ‘political’ participation be broadly defined to include interests not only in party politics and government policies, but also in civic and social activities to do with the environment, animal rights, anti-globalisation, gay rights and community activism (Livingstone et al, 2005, 288). Adopting this broader definition, many are optimistic about the potential contribution of the Internet to young people’s political participation (Hall & Newbury, 1999; Bentivegna, 2002). The Internet is perceived to be a useful technology for stimulating democratic participation by the masses, enabling citizens to be engaged in political matters (Katz et al, 2001; Rice & Katz, 2004).

Therefore, the popular view that links the consequences of young people’s engagement with the Internet to a decline in their social interactions may be overly simplistic. This view tends to overlook the fact that younger generations brought up with the Internet – often called digital natives (Prensky, 2001) – are different from older generations in the way they interact with other members of society or engage in political activities (Livingstone & Bober, 2005). For example, Livingstone and Bober (2005: 3) found that “54% of 12–19 year olds who use the Internet at least weekly have sought out sites concerned with political or civic issues.” This proportion is significant by any means of measurement.101

Barnhurst (1998: 211) describes how major media outlets like TV can change and mould young people’s views about starving children in poor nations and inform them about the types of political action required to help out. The Internet may readily provide young people with such information too. The Internet facilitates peer-to-peer connection at a low cost – not only financially but also cognitively – by providing the information needed to participate in society. While maintaining this peer-to-peer connection, young people find it necessary to go beyond consuming the content provided for them by others and to seek out, select and judge content, even create content for themselves, as a member of a community. This broader approach stimulates interests that may lead to the pursuit of goals that reflect the traditional political agenda (Livingstone et al, 2005).

However, Livingstone’s study was conducted in the United Kingdom and although the Internet, and more importantly broadband Internet, is widely available in Britain, it is reasonable to assume that the easier the access to fast Internet and the lower the price of Internet service, the easier it is to observe how young people behave in online environments. The following cases in Korea, with its advanced broadband networks, can therefore provide us with important insights into what could happen in the future in the context of advanced communications infrastructures.

The ‘Internetworked’ society: South Korea

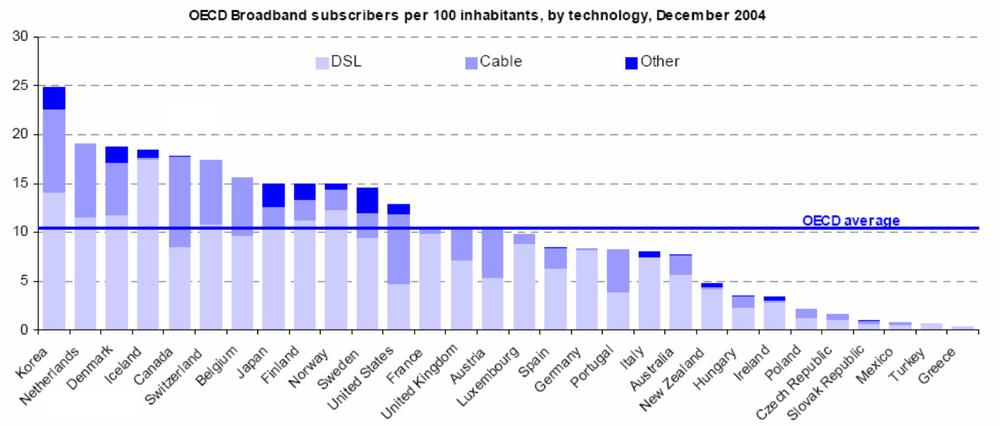

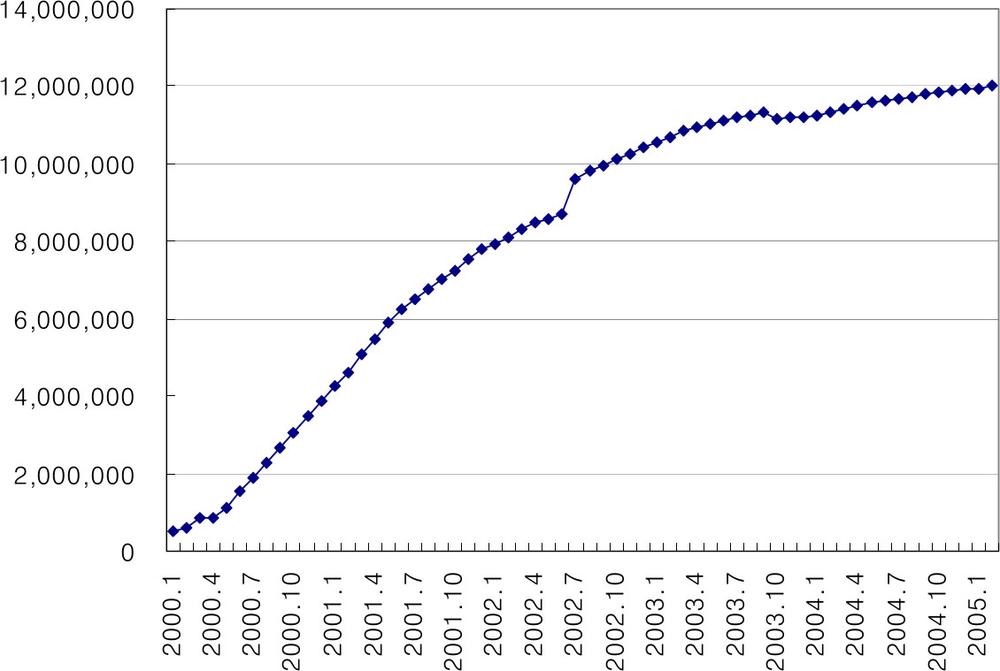

Korea has the highest penetration of broadband in the world (Figure 5.1). The number of broadband subscribers in Korea reached 11 million in mid-2003 (Figure 5.2), with about 77 per cent of 14.3 million homes connected at a speed of over 2 Mbps. What is more astonishing is that all this was achieved in less than four years from the introduction of the first broadband services in July 1998.102

Figure 5.1. Broadband access in OECD countries per 100 inhabitants

Source: OECD, 2005.

The widespread availability of broadband has significantly transformed the way Koreans use the Internet and live their lives (Lee et al, 2003). In terms of the number of Internet users per 100 inhabitants, Korea with 61.07 per cent in 2003 (ITU, 2007) has the third highest ratio after Iceland (67.47) and Sweden (63.00). With broadband Internet deeply embedded in everyday life, Koreans perceive it as a necessity, a facility they take for granted. It has become such a critical part of their lives that the Internet had a decisive impact on the result of the presidential election in 2002 (Guardian, 2003; Kim et al, 2004). Contemporary Korean society is thus characterised by its high connectivity, through broadband Internet and increasingly through mobile Internet. We therefore call it an ‘Internetworked society’.103

Figure 5.2. Number of broadband Internet subscribers in Korea

Source: National Internet Development Agency of Korea, 2006

The rapid roll-out and take-up of broadband services in Korea have been achieved through a combination of several factors: facilities-based competition, government leadership, geography and demographics, the PC Bang1 phenomenon, pricing, and some unique elements of Korean culture.2

104Two case studies: campaigns by young people

In the following section we present two examples where teenagers raised their voices collectively in the cause of human rights and protested against educational policies that would affect their quality of life at high school.

‘No Cut’ campaign

This campaign was concerned with the rigid hairstyle controls imposed in Korean secondary schools. Strict restrictions are placed on the appearance of students’ hair, in particular its length. When a student is discovered with longer hair than allowed, the punishment is embarrassing. A hair razor is applied ruthlessly to create a line, or patch, of short hair through the long hair. Students call it ‘a motorway is open’. Apart from creating an ugly look, it is a humiliating experience.

A group of students raised the haircut issue from a human rights perspective via a community website in May 2000. A further site dedicated to the haircut issue was also established at (http://idoo.net/?menu=nocut&sub=campaign). The ‘No Cut’ campaign grew both in the cyber world, where 1.6 million young people ‘signed on’ in support of the campaign in just three months, and on the street, where demonstrations were successfully organised. In October of that same year, the Ministry of Education announced a recommendation that advised secondary schools to take a flexible approach on the matter (Donga Ilbo, 2000). However, the notorious practices continued; there was a reactionary movement by educators; student leaders and participants in the campaign were expelled from some schools; and the former restrictions were re-established.

In 2005, the ‘No Cut’ campaign was renewed under the banner of the ‘National Network for the Protection of Student Human Rights’ in which not only students but also citizen groups participated. This originally online network also organised offline demonstrations (Donga Ilbo, 2005). In response, the 105Minister of Education met with student representatives. (This is unprecedented in Korea, where secondary school students’ demands are normally ignored along with the cause of university entrance exams. A typical saying is, “Persevere and survive your hellish secondary years, then the heavenly university life will come” – which is related to the second campaign below.) Although there was no tangible outcome from this meeting, it was a pleasing outcome and an achievement for the students who participated in the campaign because the Ministry responded in a serious manner.

Protest against the new university entrance selection scheme

The second case study concerns the protest against a newly introduced policy for university entrance exams. In October 2004 the Ministry of Education announced a new policy for the university entrance selection system which would come into effect for entry in 2008 and which therefore would affect the then Year 10 students at the time of the protest in early 2005.

The major change proposed increased weightings of academic grades across all subjects studied during the three years of high school, compared to the previous system of giving greater weightings to grades in the final year and the results of the national examination (equivalent to Victorian Certificate of Education in Victoria or High School Certificate in New South Wales of Australia).

In Korean society, going to a university, or more accurately speaking, going to a reputable or the ‘best’ university, is a major goal for almost every student. The new policy meant that students would have to work much harder throughout all three years of high school since all activities are assessed and, in theory, contribute to the final university entrance grade. In response to this proposal, many online communities (e.g. café.daum.net/freeHS) emerged, where high school students, mainly in Year 10, discussed and complained about the new policy (Yonhap News, 2005a). Through these online 106communities and SMS messaging, students also organised candlelight demonstrations, which attracted huge attention from the media and the general public (Yonhap News, 2005b).

What should be noted from both of these campaigns is the fact that all activities were initiated and organised through the Internet. Evidently the campaigns emerged because students initially expressed their anger in small online communities, and the presence of the communities was then circulated as a dedicated website. The sites attracted attention and became populated by a huge number of sympathetic students. It was on these sites that spontaneous suggestions for offline demonstrations were made by some community members. Once a suggestion was well received by the community, it was put into action, reflecting an organic form of democracy or cyber citizenship.

Discussion

Politicians in many countries, including Australia, are concerned that young people are increasingly losing interest in politics, civic participation, and social and community activities. However, the examples discussed above show that young people are still willing to participate when participation is in keeping with their virtual or digital activities, and action is in their interests. Undoubtedly the availability of various types of participation, and the opportunities for voices to be heard, are signs of a healthy society, both now and in the future.

As mentioned earlier, there are two opposing views as to whether there is a positive correlation between ICT and young people’s participation in civic affairs. Although it is acknowledged that this area requires further research, three key implications arising from the case studies are discussed below.

First, today’s generation is the first to have grown up with the Internet and mobile technologies. This is the generation Prensky (2001) calls ‘digital natives’, as opposed to ‘digital immigrants’ who are people in their 30s and over who entered 107the new digital age in mid-life. ‘Digital natives’ think and process information fundamentally differently from older generations. They are ‘native speakers’ of the digital language of computers, video games, the Internet and mobile phones. Their ways of expressing themselves, interacting and participating are different from those of ‘digital immigrants’. They should not, therefore, be judged by the standards of ‘digital immigrants’. ‘Digital natives’ may have, or may develop, their own way of participating in social and political activities. Further, the Internet and other information and communication technologies offer the digital natives new ways and motivations in carrying out their tasks (Carpini, 2000: 348). However, ‘digital natives’ as future leaders still need to work with digital immigrants in collaboration in terms of the issues and contexts that are yet to come rather than those of the past (Youniss et al, 2002).

This generation of young people tends to combine participation in social and political affairs with fun (Friedland & Morimoto, 2006). They use parody, humour, wit and caricature to express their feelings and opinions, rather than direct criticism. They may sometimes become ‘flash’ mobs: a demonstration is organised via mobile phone and the Internet; participants gather and display their message in an unusual, notable and often humorous way, just for a while; and then they quickly disperse. We need to find ways to encourage the digital generation’s participation, nurture their political curiosity, and help them engage in social affairs (Coleman, 2004, 2005).

Finally, when we evaluate the social and political effects of technology on young people, we also need to see beyond the immediately obvious in their behaviour. Superficial assessment of young people’s Internet-related behaviour may be less than productive. While they are pursuing fun and pleasure, it seems that they are not considering the broader social and political implications of their actions. However, based on the activities described above, their actions do not occur in a vacuum.108

Their acts, including any type of Internet activities, necessarily involve goods and services, for example, computers, infrastructure and broader service networks. Thus, their engagement in the Internet results in intended or unintended consequence, e.g. support for the service networks and providers, which is closely tied to socio-economic dimensions of a given society. This engagement has political implications in itself, either intended or unintended. Therefore, we suggest that holding the perspective that young people who spend much of their time to the Internet are largely disengaged from politics has the potential to exacerbate any existing disengagement, by systematically dismissing their political opinions and participation and failing to acknowledge any interest. This view is rather simplistic as argued in this paper. To put this differently, individual agents’ thoughts and actions ought to be influenced by or reflect existing social and economic structures. In turn, it is individual actions that transform the social and economic structures (Danermark et al, 1997; Bhaskar, 1989). However, it will take time until we realize the full implications of a new perspective or revolutionary medium such as the Internet on broader society.

Conclusion

There is a popular view that computers and the Internet tend to make young people less responsive to social or political demands of the society in which they live. Some studies (see Carpini, 2000) show however, that if we adopt a broader concept of participation, new media channels can in fact help young people to participate in civil activities by lowering the costs of participation. The two campaigns by young Koreans discussed in this chapter exemplify how the Internet can provide them with avenues to express desires and perspectives, and consequently facilitate their civic participation.

There are some important messages here for politicians, policy-makers and civil society groups. Those who are interested in young people need to consider new and innovative ways to reach 109this and future generations. The commonly proposed distinction between ‘politicised’ or digitally ‘de-politicised’ young people can be seen as an ill-informed and counter-productive perspective. As the significance of the Internet increases, patterns of political participation will continue to change. The era of the Internet has just begun and we still do not know the extent to which it will continue to influence people’s everyday thinking and behaviour as well as broader governance issues. We need to think strategically and understand how to mobilise young people’s creativity in a socially constructive way. This will be an important question for a healthy democratic society in the future.

This chapter is not without its limitations. First of all, this chapter is built on two cases that are anecdotal, but could have been investigated in more detail. Although they are sufficient enough to show a trajectory of the relationship between youth and emerging new media, we still need more documentation of other convincing cases. Related to the first point, the examples we have presented in this chapter are from Korea, which has a unique socio-political context and history. It would be inappropriate to presume that the same level of advanced communication infrastructure in other societies will necessarily lead to a similar level of social participation among both young people and adults. Other societies may explore and encourage new and different ways to participate in social and political activities. For example, Lim Kit Siang, the opposition leader of Malaysia, has managed to attract much more serious interest than in the past from young Malaysians through his blog <http://blog.limkitsiang.com>. Similarly, the Australian Liberal Party launched the site (http://sameoldlabor.com) a parody critical of the opposition party, on the day when their rivals, the Australian Labor Party, elected a new leader; the site features a short and colourful animation which is highly accessible to youth. Moreover, how youth in countries with a long tradition of democracy (e.g. India) or an increasingly strong economic capacity (e.g. China) will express their political interest is yet to 110be seen. Iran is another interesting example. According to recent research (reported in USTODAY.com, 2005): “Although the Internet has not altered the power structure of the government [in Iran], it has transformed campaigning and laid the groundwork for political change.” The report makes specific reference to how young people in Iran actively seek to have their political voice heard.

Further research is required to investigate the effects of emerging media on young people’s social and political engagement in various social, cultural and political milieux. Such research will help provide a deeper understanding of the nature of political participation in the Internet Age. This will also enlighten future directions for so-called ‘digital democracy’ and ‘e-politics’.

111

References

Barnhurst K G, 1998. Politics in the fine meshes: young citizens, power and media. Media, Culture & Society, Vol 20, pp 201–218.

Bentivegna S, 2002. Politics and new media. In Lievrouw L and Livingstone S, eds. The Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Consequences of ICTs. London: Sage. pp 50–61.

Bhaskar R, 1989. Reclaiming Reality: A Critical Introduction to Contemporary Philosophy. London: Verso.

Carpini M X D, 2000. Gen.com: youth, civic engagement, and the new information environment. Political Communication. 17 (4), pp 341–349.

Choudrie J and Lee H, 2004. Broadband development in South Korea: institutional and cultural factors. European Journal of Information Systems, 13 (2), pp 103–114.

Coleman S, 2004. Connecting Parliament to the Public via the Internet: Two Case Studies of Online Consultations. Information, Communication & Society, 7 (1), pp 1–22.

Coleman S, 2005. The network-employed citizen: how people share civic knowledge on line. [Online]. Available from: http://www.ippr.org.uk/uploadedFiles/research/projects/Digital_Society/the_networkempowered_citizen_coleman.pdf [accessed 3 March 2006].

Danermark B, et al, 1997. Explaining Society: Critical Realism in the Social Sciences. London and New York: Routledge.

Donga Ilbo (2000). Easing hair style regulations. 4 October. [online] Available from:

http://news.naver.com/news/read.php?mode=LSD&office_id=020&article_id=0000029139§ion_id=102&menu_id=102 [accessed 5 June 2007].

Donga Ilbo (2005). Demonstration: No cut. 16 May. [online] Available from:

http://news.naver.com/news/read.php?mode=LSD&office_id=020&article_id=0000299142§ion_id=102&menu_id=102 [accessed 5 June 2007].112

Friedland L A and Morimoto S, 2006. The lifeworlds of young people and civic engagement. In P. Levine and J. Youniss, ed. Youth Civic Engagement: An Institutional Turn. College Park, MD: The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement, 2006, pp 37–39.

Guardian (2003). World’s first internet president logs on. 24 Feb. [online] Available from:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/korea/article/0,2763,901445,00.html [accessed 5 June 2007].

Hall R and Newbury D, 1999. What makes you switch on? Young people, the Internet and cultural participation. In Sefton-Green J, ed. Young People, Creativity and New Technologies. London: Routledge. pp 100–110.

ITU – see International Telecommunication Union

International Telecommunication Union, 2007. ICT statistics database. [Online]. Available from: http://www.itu.int/ITUD/icteye/Indicators/Indicators.aspx# [accessed 5 June 2007].

Katz J E et al, 2001. The Internet, 1995-2000: Access, Civic Involvement, and Social Interaction. American Behavioral Scientist, 45 (3), pp 405–419.

Kim H, Moon J and Yang S, 2004. Broadband penetration and participatory politics: South Korea case. Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences.

Lee H and Choudrie J, 2002. Investigating broadband technology deployment in South Korea. Brunel-DTI International Technology Services Mission to South Korea.

Lee H, O’Keefe R M and Yun K, 2003. The Growth of Broadband and Electronic Commerce in South Korea: 113Contributing Factors. The Information Society, 19 (1), pp 81–93.

Livingstone S and Bober M, 2005. Final report 'UK Children Go Online: Final report of key project findings' (published 28 April 2005), London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

Livingstone S, et al, 2005. Active participation or just more information? Young people’s take up of opportunities to act and interact on the Internet. Information, Communication & Society, 8 (3), pp 287–314.

National Internet Development Agency of Korea, 2006. [Online]. Available from http://isis.nida.or.kr/index_unssl.jsp [accessed 5 June 2007].

OECD, 2005. OECD Broadband Statistics, June 2005. [Online]. Available from:

http://www.oecd.org/document/16/0,3343,en_2649_34223_35526608_1_1_1_1,00.html#Graphs2005. [accessed 5 June 2007]

Prensky M, 2001. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, 9 (5), pp 1–6.

Putnam R D, 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Putnam R D, 1995. Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. Journal of Democracy, 6 (1), pp 65–78.

Rice R E and Katz J E, 2004. The Internet and Political Involvement in 1996 and 2000. In Howard, Philip N & Jones S, eds. Society Online: the Internet in Context. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004.

USTODAY.com (2005) Internet boom alters political process in Iran. 6 December. [Online]. Available from:

http://www.usatoday.com/news/world/2005-06-12-iran-election-internet_x.htm [accessed 3 March 2006].114

Yonhap News, 2005a. 2008 university entrance, big bang. 17 April. [Online]. Available from:

http://news.naver.com/news/read.php?mode=LSD&office_id=001&article_id=0000977429§ion_id=100&menu_id=100 [accessed 5 June 2007].

Yonhap News, 2005b. Opposition to the relative assessment of high school grade points. 7 May. Available from:

http://news.naver.com/news/read.php?mode=LSD&office_id=001&article_id=0000996294§ion_id=102&menu_id=102 [accessed 5 June 2007].

Youniss J, et al, 2002. Youth civic engagement in the twenty-first century. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12 (1), pp 121–148.

1 PC Bang (meaning “room” in Korean) is similar to Internet cafés in other countries. However, PC Bangs are perhaps a unique Korean phenomenon in terms of its popularity and impact in early years of broadband diffusion.

2 Discussions of the success factors are beyond the scope of the paper. For details, see Lee and Choudrie (2002), Lee et al (2003), and Choudrie and Lee (2004).