>meta name="googlebot" content="noindex, nofollow, noarchive" />

10

Civilising nature: museums and the environment

Abstract

Interpreting the natural environment in the cultural context of a museum is common practice in the early 21st century. It was also quite common in the 19th century. This chapter considers some of the key discourses in natural history and science museums to reveal a rich legacy of engagement with the environment. It begins with a review of a contemporary film that portrays the wonders of the museum at night when its history and politics come alive. Museum history demonstrates that, far from being a mausoleum, museums are crucial sites for environmental education and research. This paper argues that museums shape and reflect environmental attitudes. Using Australia’s oldest museum, the Australian Museum located in Sydney, the chapter demonstrates the complex connections between museum cultures of collection and display, and research and environmental issues.

Introduction

In a popular comedy movie released in 2006, a natural history museum in a large American city mysteriously comes to life at night when there are no visitors. The corollary, and the trope that contributes to the film’s success, is that the museum is dead during the day. The museum is a mausoleum – a dead boring place. It is a challenge experienced by many people associated with museums. While museum curators and educators promote the concept of the museum as being alive in the minds of visitors, whether by responding to social changes or technological changes in the form of interactive displays that engage new audiences, the idea of museums as being places of old, decrepit and dead things is a 320difficult stereotype to overturn. Yet it is this very stereotypical characteristic that the new night watchman in the film Night at the museum, soon realises is indeed untrue: the natural history museum is in fact abundant with history, discoveries, unresolved problems and questions. Unable to be contained by the museum, the exhibits escape and are seen on the streets of Manhattan. This generates a news item that in turn brings in the curious tens of thousands, in the film and in reality. Such is the mythical status of the museum and its work.

One sector of museum activity burdened by the ‘museum as a mausoleum stereotype’ is that of relationships between museums and ‘the environment’. The stereotype of large generalist museums and natural history museums filled with skeletons and the labour of taxidermists does not do justice to the complex relationships between museums and the environment, nor does it reflect the controversies inherent in knowledge creation and dissemination. As we demonstrate in this chapter, far from being mausoleums, or even focused on the past, museums are playing important roles in shaping, documenting, cataloguing and reflecting our relationship with nature.

There are three aims of this chapter. The first is to identify how museums are positioned in relation to the environment. The second is to analyse how this positioning has changed over time due to changing environmental conditions and discourses, and changes in museum practice and context. The third is to identify how museums can engage with environmental issues in the 21st century.

The chapter begins with an overview of museum history, particularly in relation to the development of environmental thought and concern. It then looks at how three Australian museums have constructed the environment, or mediated the environment and presented it to audiences, through examples of temporary and permanent exhibitions. It is important to remember that these examples reflect thinking in specific places at particular points in time. The chapter then looks in more detail at the Australian Museum in Sydney, and demonstrates how it engages with environmental thought and concerns, and how this engagement has changed over time. The chapter concludes that museums have important 321roles to play in engaging with nature in ways that are educational, participatory, scientific, ethical and sometimes controversial.

Museums and the evolution of environmental thought

The development of museums and natural history museums

The word ‘museum’ is a Latin word from the Greek word ‘mouseoin’ (Alexander 1979). The term initially meant “the abode of the muses; these abodes were groves on Mounts Parnassus and Helicon” (Dixson 1919, p. 3). They later became temples, then universities with many colleges. Some of the earliest museums were located in cities such as Alexandria, Athens and Rome. They were associated with knowledge creation and dissemination similar to the role of modern universities, or were devoted to displaying captured treasures. With the destruction of the city of Alexandria, the term “museum” was virtually unheard, “and was only revived with the arts and sciences about the middle of the 17th century” (Dixson 1919, p. 3). While the art collections of royalty and wealthy buyers were the forerunners of public art galleries, and the royal menageries became the ancestors of modern zoological gardens, the museum emerged from the private ‘cabinet of curiosities’ to become the public collection of history, anthropology, geography and technology. The first university museum opened in Basel in 1671, with the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford being established as the first public natural history museum in 1683 (Alexander 1979).

By the middle of the 19th century, museums were vital in the industrialisation and colonial processes. Museums catalogued and presented socio-economic and technological change in particular ways to their audiences. The major imperial museums displayed the wealth and curiosities of the dominions to the imperial core of the various European empires. Museums displayed the ‘riches’ of the colonies to citizens in the important cities of empire – London, Paris, Berlin – and in doing so had various and often profound environmental and cultural impacts in the colonies and territories.

322The emergence of natural history museums in London, New York and other major cities during the 19th century was related to notions of civilisation and the perceived separation of humans from nature. The growth of the cities often led to nostalgia for rural and non-urban environments, partly because of the squalid character of many parts of the industrial cities. Nature was generally perceived as those areas outside the city. In the USA, a frontier mentality reinforced this construct of urban-civilisation versus nature-wilderness (Luke 2002). Natural history museums, in particular, were conduits for both places and time. The natural history museums connected the urban dweller with nature that existed beyond the frontier of civilisation, in much the same way as exotic displays of tribal art, clothing and weaponry connected urban Australians with inland communities. The natural history museums also connected the urban dweller with the former character of their now-urban region. In the USA this selective recalling of the past was important in the nineteenth century because of the rate of change in population, landscape modification and technological and cultural development.

There was a rapid and unprecedented growth in the number of museums during the nineteenth century. Focusing only on natural history museums, by 1900 there were 150 museums of natural history in Germany, 250 in Britain, 300 in France and 250 in the United States (Sheets-Pyenson 1988). Speaking at the Australian Museum in 1919, Thomas Storie Dixson noted that in 1903 there were 31 natural history museums in New York state (population 7 million), 10 such museums in California (population 1.5 million) and only one such museum in New South Wales in 1919, despite the state having a population of 2 million people (Dixson 1919). Dixson qualified this last remark by noting the existence of the Macleay Museum at the University of Sydney, “which the public can hardly be said to know of” (Dixson 1919, p. 8).

The growth in the number of museums throughout the world resulted from the confluence of technological progress and ideas about civilised societies. The technological progress of the 18th and 19th centuries enabled various countries in western Europe to explore and colonise distant lands. The display of objects from these colonies in the largest cities of the imperial power not only showed the citizens of the imperial 323country what they possessed, how they were changing it, but was also following the earlier ideas of leading scientists, such as Francis Bacon, to broaden knowledge and challenge the intellect. According to Bacon, “… we should no longer dance around within small Circles (as if we were enchanted by a Spell) but should equalize the Circumference of the World in our Circuits” (Bacon 1670, p. 4; also cited in Parrish 2006, p. 71). The orderly display of objects, perusal and the resultant education of the viewer, was intended to engender a fascination with the world, and a respect for authority, particularly from the working classes.

The museums, along with various organisations, such as the Royal Society in London, were responsible for promoting scientific and cultural advancement, and were influential in the promulgation of ideas about nature. Museum curators taught at universities, and museums were involved in research activity to elucidate knowledge about the world (Yanni 1999). The 19th century witnessed profound changes in our understanding of the world. The natural history museums generally built on the new knowledge of this period, particularly the work of Charles Darwin on evolutionary theory and the development of the new science of geology (Asma 2001; Sheets-Pyenson 1988). The knowledge was developed through the principles of scientific inquiry – systematic observation, experimentation, development of laws, the ability to replicate. Over time, scientific inquiry came to replace gentlemen naturalists, with profound impacts on the relationships between science, religion and various concepts of nature.

The intellectual foundations of natural history museums

The 19th century was also important for the changes in museum culture and display practices with regard to, amongst other things, nature. The idea of collecting and displaying natural history is a humanist concept that is much older – “Natural history was invented in the Renaissance” in western Europe in the 16th century (Ogilvie 2006, p. 1). The natural historians were often young men who could travel, initially within Europe, but increasingly by the eighteenth century to more remote places and for longer periods. This idea of constant motion, as Ogilvie (2006, p. 141) wrote of the sixteenth century naturalist – “motion between the library, the cabinet, the salon (or dinner table and printers’ shop), the garden, the wharf, and the countryside” highlights the 324relationships between the texts about nature (the library), the museum (the cabinet of curiosities) and the collecting practices. Another crucial change in the eighteenth century is the classification of objects. The earlier forms of classification included alphabetisation, but this became impractical as curiosity cabinets expanded. Various scientific systems of classification were developed as disciplines, such as biology and geology produced new knowledge and re-ordered existing knowledge.

There was also a major change in the way displays were arranged, and for whom they were arranged. In the cabinet of curiosities, displays were comprehensive in the sense that virtually everything collected was displayed. The criteria for collection and display of material were often based on qualities of uniqueness, distance between the location of its collection and display, and the individual or sometimes the aesthetic properties of the object. In the 19th century, displays in many major museums became selective. Sir William Flower, Director of the Natural History Museum in London, was an advocate of displaying fewer objects in the public exhibition so that the lay visitor could gain a general understanding and appreciation of nature (Flower 1898; Sheets-Pyenson 1988). The increasing quantity of objects held by the major museums could be kept in storage drawers and cabinets for specialist research purposes. Despite this separation of the research and exhibition functions of museums, natural history museums may still be perceived as “eccentric treasure chests of weirdness [which] with their displays of the exotic and the rare, have always existed at the frontier of credulity and wonder” (Asma 2007, p. 27).

The notion of ecosystems was not available to 19th century museum curators, so the individual objects were displayed like stamp collections (as in the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford), or in easily observable habitats and relationships, as in many dioramas of predator-prey relationships. From inception there was a division between zoos and natural history museums. In zoos, the animals were alive and often placed in unsympathetic settings to experience social isolation from the herd (although this critique has led to improvements in zoological practice over the years). In natural history museums, the dead animals were made life-like by skilled taxidermists and placed in contrived settings to highlight the natural environment and particular traits of the animals. In 325the museum, the fox’s jaws remain open forever – the fox never catches the rabbit and the frightened rabbit is never safe from the predator.

Nature, science and religion

The will of Sir Hans Sloane, who died in 1753 and whose massive private collection became the basis for the establishment of the British Museum, provides an interesting insight into the relationships between nature, science and religion. The will stated that Sloane had made the collection for “the manifestation of the glory of God, the confutation of atheism and its consequences, the use and improvement of physic and other arts and sciences, and benefit of mankind” (Alexander 1979, p. 45).

In the 19th century, the growth in the number of natural history museums, and expansion of individual museums, both reflected and shaped a concern with nature and questions about human existence. The rise of scientific inquiry led to new understandings of nature, but these understandings were, generally, intended to demonstrate through science the greatness of God. It was in the latter half of the 19th century, and particularly through the work of T H Huxley in promoting Charles Darwin’s version of evolution, that the potential for conflict between religious and scientific explanations of the world was realised (Yanni 1999). This was important not just in ascribing credit for creation or evolution, but also in situating humans in the world in relation to other species. Collections were no longer amassed primarily to show the manifestation of the glory of God and to confute atheism, but increasingly to further scientific understandings of nature. The exploration and collecting were “galvanized by Darwin’s theories of evolution, and the world’s naturalists were busily reconstructing the tree of life” (Hennes 2007, p. 90). According to Griffin (1992 p. 3), “natural history collections provided a three dimensional map on which the course of evolution could be charted”. The 19th century natural history museum was a “cathedral of science” (Sheets-Pyenson 1988). Central to this cathedral was the concept of evolution, which was heretical to many devout religious people, because it challenged the position of God as the Creator of the universe and all that was in it.

326This conflict between science and religion was addressed by Sir William Flower, Director of the Natural History Museum in London, in a paper read at the Church Congress in Reading on 2 October 1883. Flower (1898 p. 134) noted that while science was increasingly discovering “the processes or methods by which the world in which we dwell has been brought into its present condition”, this did not take away the mystery of Creation. Science, according to Flower, was discovering explanations for “the succession of small miracles, formerly supposed to regulate the operations of nature”, but it could not explain the origin of the world and that it was inconceivable that the world “could have originated without the intervention of some power external to itself” (Flower 1898, p. 134).

It is apparent that since the late 19th century, natural history museums have evolved to incorporate new scientific understandings in areas such as biodiversity and climate change (Griffin 1996). Concepts, such as ecosystem, have been incorporated into research and exhibitions in these museums. Evolutionary thought, and the classification systems that were developed in the 19th century, are now so normal in contemporary natural history museums that they are almost invisible. One of the significant challenges today is how natural history museums show or represent the significant research and development they continue to undertake (Krishtalka & Humphrey 2000; Suarez & Tsutsui 2004; Worts 2006). However, the role of scientific evidence in informing the display of objects, and in the process of creating new knowledge through museum-based research, has recently been called into question by the opening of a new museum in Petersburg, Kentucky, that challenges the 19th century scientific basis of natural history museums.

The Creation Museum is a ‘rebuttal museum’ to these natural history museums, with its critique that “almost all natural history museums proclaim an evolutionary, humanistic world view. For example, they will typically place dinosaurs on an evolutionary timeline millions of years before man” (Asma 2007, p. 26). The Creation Museum is designed to “proclaim the accuracy of the Bible from genesis to Revelation, … show that there is a creator, and that this creator is Jesus Christ …” (Asma 2007, p. 26). This museum highlights the diversity of thought about nature/environment/ecology/Creation. While it is only one Christian 327perspective on the environment (see Gatta 2004; Leal 2006; Rue 2006) it calls into question the roles of science and faith in knowledge creation and dissemination. It shows that museums are engaged in the politics of knowledge, whether this be natural history museums, anthropologically oriented museums or art museums. It also shows that what is at stake is which knowledge is valid and which is invalid.

Australian museums and environmental thought

Contemporary museum displays about the environment are informed by different environmental knowledge from that in the 19th century. This does not mean that contemporary museums focus on similar environmental themes, or have a common understanding of how to present environmental issues. While not exhaustive of all possibilities, the following three snapshots highlight the diversity of environmental constructions and representations in contemporary museum practice in Australia.

The Australian Museum - Biodiversity

Until very recently the exhibition Biodiversity at the Australian Museum in Sydney integrated science and popular environmental concerns. The theme of the exhibition would not have been possible in the 19th century. It was not until the environment was repackaged as biodiversity, and biodiversity was valued in some form, that this theme could exist and attract visitors.

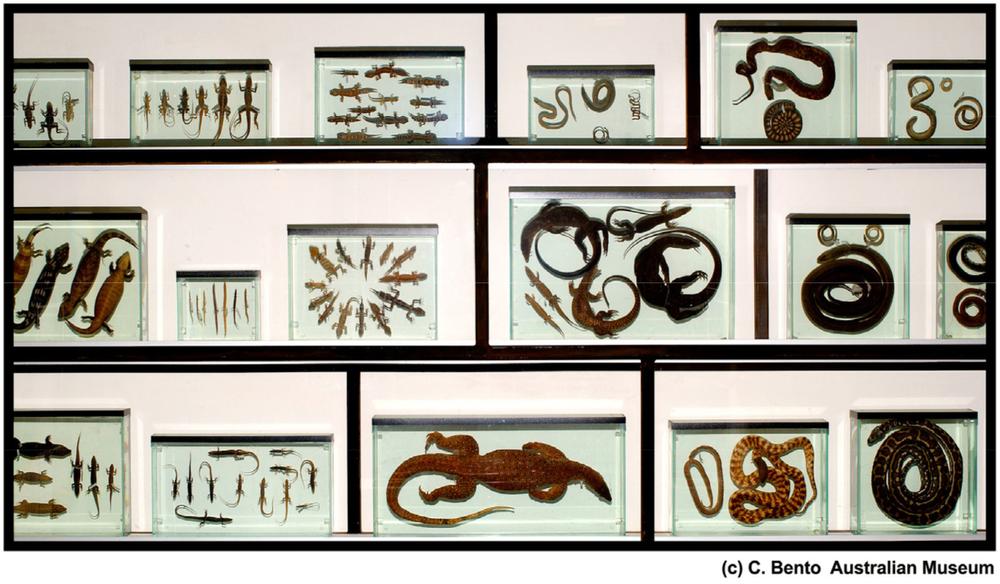

This display (Image 10.1) was not simply a collection of biodiversity to show as a curiosity, it also embodied four of the dominant discourses in contemporary environmental thought: the sense of loss, the sense of ongoing vulnerability, and the urgency of a race against time to both slow the rate of loss and to repair damaged environments. Visitors to the biodiversity display had generally seen other environmental displays in the museum – including dinosaurs, skeletons and the collections of stuffed birds, pinned butterflies and dead insects that represent earlier understandings of ‘the environment’ before they encountered Biodiversity, which included live baby crocodiles. This display was a departure from 328the other displays because it was based on the principles of scientific ecology (rather than biology) and incorporated concern about the importance of biodiversity, the vulnerability of biodiversity and the loss of biodiversity in various parts of the world.

Figure 10.1 Biodiversity Gallery: specimens. Photo by Carl Bento, copyright Australian Museum, no date

With the current forty million dollar renewal and refurbishment project of the Australian Museum and its galleries, the associated collections and program on biodiversity will be dispersed throughout the museum and the concepts of biodiversity will be addressed in the new Surviving Australia Gallery, opening in 2008. This gallery will focus on the diversity of Australia’s habitat, its unique species and their evolution. On a practical level, the subject of biodiversity is also explored in Search and Discover, the ‘hands on’ education centre of the museum (see Image 10.2). Kidspace (formerly Kid’s Island) is also a place in the museum where children can explore the themes of biodiversity. 329

Figure 10.2 Search and Discover (education centre). Photo by Carl Bento, copyright Australian Museum, no date

The Powerhouse Museum – EcoLogic: creating a sustainable future

The exhibition, EcoLogic at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney includes, among other things, displays and information about sustainable living. It recreates a ‘sustainable house’ and presents “new ideas and technologies that can reduce our individual and collective impact on the planet” (www.powerhousemuseum.com/exhibitions/ecologic.asp). The exhibition is concerned with “the way we use the world” (see Image 10.3). The environment is presented not as surroundings, or as a collection of curiosities from a distant place, but as something that is part of the daily lives of people in their domestic space.330

Figure 10.3 Visitors to EcoLogic can calculate the cost of different hot water systems, both in dollars and CO2 emissions. Photo: Jean-Francois Lanzarone, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, 2001

EcoLogic also highlights the importance of consumption (see Image 10.4) – whether this is at the stage of purchasing decisions, the environmental performance of fittings and appliances in dwellings, or the disposal of packaging and unwanted items as waste. In this exhibition, people are connected to nature through their lifestyles, and the interactive displays on issues such as hot water provision in the dwelling are clearly advocacy-oriented in informing people of more sustainable options. The exhibition also includes a population counter, reflecting the concerns of many people that the biggest threat to the environment is the growth in world population (currently at approximately 6.7 billion people). 331

Figure 10.4 A crushed car at the entrance to EcoLogic surprises viewers and raises awareness of our material consumption. The population clock nearby ticks over at an alarming rate. Photo: Jean-Francois Lanzarone, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, 2001

The web presence of the exhibition is important and is linked to relevant resources. It includes teacher’s exhibition notes and, in this sense, the exhibition and associated research is made available for the public to view and use, potentially for further research.

The National Museum of Australia

The environmental displays at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra are less advocacy oriented, but are important in emphasising the concept of the environment as being connected with people. The rotating audio-visual display Circa has the theme of “land, nation, people” and, as indicated by the title, changes over time. Key themes in this display include the variation in Australian environments, the 332diversity of environmental ideas and beliefs and the heterogeneity of the Australian population. Other crucial themes include human reliance on the environment, the belief that the actions of environmentalists are preserving the environment for future generations, and that by showing respect for animals people are respecting themselves. Amongst other important displays is the Biological avalanche in the Old New Land Gallery (previously Tangled Destinies) (see Images 10.5 & 10.6). It comprises an electronic shape of Australia, where red lights highlight the spread of the red fox, European wild rabbit, starling, cattle tick and the European Carp at different times. The display shows the dynamic and spatial aspects of invasion. Other displays include photographs, objects, text, visual and audio recordings of various engagements with the land by men, women, Indigenous people, newly arrived settlers, and so on. Different forms of environmental knowledge are highlighted, including Indigenous knowledge, scientific knowledge, popular culture and various lived experiences.

These displays are notable for their relative impartiality towards ideas, activities and people who could easily be praised or condemned depending on how they are viewed by adherents of different environmental philosophies. There is no blaming of environmental vandals. This appearance of impartiality may be expected in such a museum, but from the perspective of radical environmentalists of various persuasions, the impartiality could be interpreted as political pandering to the vested interests of those who are, in many cases, continuing the activities that are questioned in the displays. If the environment is of such importance, displays that fail to highlight the causes of environmental damage and, where necessary, blame the catalysts of such damage, may be perceived as doing a disservice to environmental concerns. Alternatively, learning from the past and using this to guide future practice may be interpreted as a responsible action by a national museum. For example, there are warnings in the displays that extinctions have occurred, both high profile extinctions (such as the thylacine) and extinctions that have gone virtually unnoticed (birds in the wheatbelt regions of Australia), and that extinction is still possible. The idea of learning from the past, to avoid repeating mistakes, to contain rather than being able to eliminate certain environmental threats, and to be cautious about the introduction of non-endemic species, are all 333important points made at the National Museum of Australia in relation to the environment.

Figure 10.5 Biological avalanche. Photo: National Museum of Australia (c. 2002) 334

Figure 10.6 Old New Land Gallery. Photo: Dean Golja, National Museum of Australia (c.2002)

Complexities of museum–nature interactions

The above three snapshots of the changing relationship between museums and nature over time, and the differing approaches of contemporary museums in Australia, highlight the complexities of museum-nature interactions. As a number of natural history museum directors in the United States noted in a special issue of Museum News in 3351997, there is no single correct answer as to the form of this engagement (various, 1997). More recently Hennes (2007) revisits the question: What is the role and character of natural history museums in the 21st century? He identifies that museums are no longer part of an “ontologically-driven study representing an ordered natural world we sought to master” but are part of a “more interdisciplinary study of a disordered, self organizing natural world in which our species is but one of many codependent actors” (Hennes 2007, p.91).

The opportunities, and the obligations, to address environmental issues are not restricted to natural history museums. Davis (1996) discusses the opportunities for all museums to become “environmentally friendly”, emphasising the importance of environmental audits and highlighting the need for museums to sell products that minimise environmental impacts, to reduce energy consumption and to place environmental policy in a central position in the organisation. The relationships between museums and the environment are negotiated processes and outcomes that are influenced by ideas, individuals, the mandate of the museum, perceptions of audience desires, museum culture, politics and other factors that vary between institutions and through time.

Part of this negotiation involves the museums engaging with museum educators and others in the annual Museums Australia conference, the theme of which in 2007 was sustainable development. This theme alone highlights the changing character of museum-environment engagements, as the term ‘sustainable development’ was not coined until 1980 and was not popularised until the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) report in 1987 (WCED, 1987). How does such a global discourse, which emerged out of the United Nations’ organisation, translate into museum culture in Australia and into the practices of individual museums on a day-to-day basis? As part of this quest, in the next section of this chapter we explore in more detail the changes in museum–environment relationships in one particular august institution, the Australian Museum. 336

Figure 10.7 Bird Gallery, first floor, west wing, about 1950. Copyright Australian Museum Archives

Changes in environmental understandings at the Australian Museum

The Australian Museum was founded in 1827, following the demise of the short-lived museum established by the Philosophical Society in 1821 (van Leeuwin 1995). According to van Leeuwin, “the achievements of the Philosophical Society and its Museum, while modest, do demonstrate the awakening of colonial science in New South Wales” (1995 p. 45). By 1827, the idea of a new natural history museum had “resulted in a collection of objects, apparently chiefly of birds” (Dixson 1919, p. 4) which formed the foundation collection for the museum (see Image 10.7 for a 1950s version.) The Australian Museum was established through the auspices of various people, but the role of the Colonial Secretary, Alexander Macleay, was crucial. Macleay was a Fellow of the Linnean Society (from 1794 and its Secretary from 1798) 337and a Fellow of the Royal Society as of 1808 (van Leeuwin 1995). He was keen to promote scientific endeavours in the colony, and intended to keep the best local specimens in this new museum and to export duplicates to England (to go to a hierarchy of institutions – the Linnean Society Museum, then the British Museum, followed by the College of Surgeons, and fourthly the English, Scottish and Irish universities) (van Leeuwin 1995).

The early role of the museum was the scientific understanding of nature and the promotion of interest in nature. This was achieved through display practices, but also through public lectures. The South Wing of the museum, for which construction started in the late 19th century but was not completed until 1910, had attached to it:

a lecture hall, which had proved itself a necessity because of the large numbers of the public desirous of attending the lecturettes or lecture demonstrations given by the Scientific Staff. These had been begun in 1905, but relatively few persons could be admitted to them because of the scanty space available between the cases of exhibits amidst which these lecturettes were delivered. (Dixson 1919, p. 7)

The printed lecture delivered by Dixson in 1919 is also important in highlighting the perceived progress of the Australian Museum at that time in relation to other national and international museums. Dixon was impressed by some museums in the United States, particularly in “their methods of adapting their museums to the education of children” (Dixson 1919, p. 17). The Washington National Museum was cited for its child-friendly displays, while the Field Museum in Chicago was praised for its extension to schools: although only commenced in 1914, by 1916 it was servicing 250 000 children and included “476 cases of specimens being specially prepared for public schools” (Dixson 1919, p. 18). Dixson’s first recommendation for the future of the Australian Museum was to “expand our work in connection with schools … as regards loan collections, more extensive lecturing, and a children’s science library, all modified to suit local requirements and possibilities” (Dixson 1919, p. 24).

338Given this early vision, it is perhaps not surprising that, when we explore changes in the values and practice of the Australian Museum through an analysis of its annual report at ten year intervals, we see that one notable activity of the museum over many years has been to bring nature alive in the hearts and minds of children. The purpose and practice of annual reporting needs to be considered when employing this research method, which does highlight particular aims of the museum, changing environmental thought, the centrality of science in environmental discourse and engagement, and the continuities and changes in community relationships with the museum.

The 1962–3 report of the Trustees of the Australian Museum highlights the importance of quantification in terms of visitor numbers, the size of various collections, the number of new acquisitions of various items, and so on. It also emphasises the scientific research activity of museum staff, and the school service that involved 19,021 children attending museum classes for the year 1963, 803 people attending school vacation films and a children’s room that was open during three school vacations and included special exhibits for children around themes such as ‘Animals in your garden’ and ‘Australian minerals’ (Trustees of the Australian Museum 1963).

By 1972–3 there was a strong emphasis on the Australian Museum and its community, including discussion on the formation of the Australian Museum Society in 1972. Talbot (1973 p. 11) noted that “there is agitation overseas that museums are not getting out to the people, that they need to develop travelling museums, neighbourhood museums, and temporary displays away from the city”. In NSW, the links between the Australian Museum and other organisations, such as the National Parks and Wildlife Service and the Royal Botanical Gardens, were highlighted, as was the pioneering work in undertaking ecological surveys of Lord Howe Island for the Lord Howe Island Board (Talbot 1973, p. 11). These efforts “yield new species to the Museum’s collections, solve specific problems for instrumentalities, and add further information to our understanding of our flora and fauna” (Talbot 1973, p. 11). The ongoing engagement with school children now saw 26,503 children attending museum classes, with approximately 62,000 children in 1,550 classes attending the museum without an appointment. 339

In 1982–83 the annual report included the “Aims of the Australian Museums”, which were:

![]() to increase and disseminate knowledge of our natural environment and cultural heritage; and

to increase and disseminate knowledge of our natural environment and cultural heritage; and

![]() to increase our understanding and appreciation of these things.

to increase our understanding and appreciation of these things.

It was also noted that, “in achieving these aims the Museum gives special emphasis to the Australian region” (Australian Museum 1983, p. 5). There were four functions of the Museum: a scientific function, an interpretive function, a service function and one of a public responsibility (which involved good public relations and promotional activities). The Australian Museum, responding to concerns about the need for travelling museums, and so on, had initiated a Museum Train, which in the previous five years had stopped at 111 country centres, had been visited by 336,000 people (including 159,000 students in school classes) and generated an average attendance of 42.4 per cent of a town’s population. Along with existing activities, such as school loan cases, school holiday activities, and so on, it is evident that the Australian Museum was both engaging different communities and performing an important educational role for children.

The 1992–93 annual report shows a more corporatised museum, with a mission statement to “increase understanding of our natural environment and cultural heritage and to be a catalyst in changing public attitudes and actions. Research and the maintenance and improvement of collections are central to the achievement of the mission” (Australian Museum 1993, p. 13). The focus is still on the Australian region and, despite the importance given to engaging in public debates about the natural environment and cultural heritage, the final paragraph of the statement resonates nicely with the film, Night at the Museum: “we want the Museum to be an exciting and rewarding place to visit and work in … and it should be fun” (ibid. p. 13). There is recognition, in the section on scientific achievements, of growing concern about environmental issues: “There is a sense of urgency developing about the scientific work of institutions like the Australian Museum. Each year, the natural world faces increasing threats from the technologies and spread of the human population.” (Ibid. p. 19). This was seen as leading to a shift in 340“the public image of natural history museums and their perceived role. More and more, they are being seen as informed representatives of community attitudes and welcomed as pivotal players in environmental debate.” (Ibid. p. 19).

The Australian Museum is constructed as a natural history and cultural heritage museum for the Australasian region maintaining extensive collections for research purposes, but is also important in educating people about environmental matters. It does this through the application of scientific research to environmental issues, but also increasingly through its role as a respected institution cast as an informed representative of community attitudes. This is a challenging and important role because, as understandings of nature change and are continuously contested, being a representative of community attitudes, while maintaining scientific standards involves the balance of tensions within daily practice. As such, the Australian Museum continues to evolve as part of museum practice generally; evolving from 19th century cabinets of curiosities to public displays of exotic objects through to recent conservation practices that are commensurate with a vision of nature as relatively fragile and threatened by more powerful forces of technology (Australian Museum 2007). In the 21st century the cultural context of the museum’s work is being used to enhance the museum’s engagement with the public. Engagements with contemporary environmental issues, such as the loss of biodiversity (itself a fraught construct given that science has not classified and described about 90 per cent of the world’s species) and climate change, highlight the need for visionary practice that builds on tradition, but departs from antiquated ideas and practices where appropriate.

Conclusion

Museums do not come alive only at night when all the visitors have gone home. Museums are not mausoleums for dead nature. They perform important roles in engaging with nature in ways that are educational, participatory, scientific, ethical and, possibly, controversial. These engagements are about representing and examining the past, and sometimes challenging stereotypes about history, but they are also about connecting people to the world today and facilitating thought and action 341that is oriented towards developing a better future. Whilst we have focussed on the institutional history and cited some recent exhibitions, vital work is being undertaken with the cultural aspect of collections that concern our understanding of the environment.

The challenge it seems, as museums in Australia become increasingly pressured by government to communicate to the public in new ways, is how to make the everyday significance of their research and ongoing programs more visible. Governments, and the public more generally, need to see that museums are pivotal sites of engagement for understanding and communicating about our changing environment in urban and rural Australia. If museums are accepted as sites of mediation with substantial collections that contain vital information about our environment and ways of understanding it, then the relevant identifiable communities need also to be involved in the process of sustaining the work of the museum.

Constructing museums as mausoleums makes invisible the diverse work being undertaken by many museums in relation to the environment. Even more importantly, it limits the potential for museums to engage in vital work in the future. It limits people’s imagination about the potential partnerships. People who care about the environment and about museums will appreciate the importance of representing current work accurately to acknowledge the work being done now, and to enable appropriate environmental engagements to thrive in the future.

Acknowledgements

We’d like to thank the following people for their assistance: Janet Carding, Sophie Masters and Michelle Britton at the Australian Museum; Denis French and Kylie King at the National Museum of Australia, Des Griffin and Gavin Birch. 342

References

Alexander E P, 1979. Museums in motion: An introduction to the history and functions of museums, American Association for State and Local History, Nashville.

Asma S, 2001. Stuffed animals and pickled heads: the culture and evolution of natural history museums, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Asma S, 2007. ‘Natural history Spun with a young-earth doctrine’, Higher Education Supplement, The Australian, 18 July, pp. 26–7.

Australian Museum, 1983. Annual Report of the Australian Museum, The Australian Museum, Sydney.

Australian Museum, 1993. Corporate Report of The Australian Museum, The Australian Museum, Sydney.

Australian Museum, 2007. Australian Museum science research strategy 2007–2012, The Australian Museum, Sydney.

Bacon F, 1670. A Preparatory to the history natural and experimental. Printed by Sarah Griffing and Ben Griffing, for William Lee, London.

Davis P, 1996. Museums and the natural environment: the role of natural history museums in biological conservation, Leicester University Press, New York.

Dixson T S, 1919. Australian Museum, Sydney: lecture on its origin, growth and work, printed copy of a lecture delivered on 10 June 1919, The Australian Museum, Sydney.

Flower W, 1898 (reprinted 1972). Essays on museums (and other subjects connected with natural history), Books for Libraries Press, Freeport, New York.

Gatta J, 2004. Making nature sacred: literature, religion and environment in America from the puritans to the present, Oxford University Press, New York.

Griffin D, 1992. ‘Natural History Museums, the Natural Environment and the 21st Century: Planning for the 21st Century and Preparing for the Next 5000 years’. Paper presented to the International Symposium and First World Congress on the Preservation and Conservation of Natural History Collections, Madrid Spain, May 1992. Available at: http://desgriffin.com/publications-list/environment21, accessed 30 July 2007. 343

Griffin D, 1996: ‘Natural History Collections: A Resource for the Future’, Paper presented to the Second World Congress on the Conservation and Preservation of Natural History Collections, Cambridge, England, August 1996. Available at: http://desgriffin.com/publications-list/nhc-future/, accessed 30 July 2007.

Hennes T, 2007. ‘Hyperconnection: natural history museums, knowledge and the evolving ecology of community’, Curator: The Museum Journal, vol. 50, no. 1, January, pp. 87–108.

Krishtalka L & Humphrey P S, 2000. ‘Can natural history museums capture the future?’, BioScience, vol.50, no. 7, pp. 611–617.

Leal R B, 2006. Through ecological eyes: reflections on christianity’s environmental credentials, St. Pauls Publication, Sydney.

Luke T, 2002. Museum politics: power plays at the exhibition, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Ogilvie B, 2006. The science of describing: natural history in renaissance Europe, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Parrish S, 2006. American curiosity: cultures of natural history in the colonial British Atlantic world, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Rue C, 2006. Catholics and nature: two hundred years of environmental attitudes in Australia, Australian Catholic Social Justice Council, Sydney.

Sheets-Pyenson S, 1988. Cathedrals of science: the development of colonial natural history museums during the late nineteenth century, McGill-Queens University Press, Kingston and Montreal.

Suarez A V, and Tsutsui N D, 2004. ‘The Value of Museum Collections for Research and Society’, BioScience, January 2004, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 66–74.

Talbot F H, 1973. ‘The museum and the community’, Trustees of The Australian Museum, 1973, Report of the Trustees of The Australian Museum for the year ended 30th June, 1973. The Australian Museum, Sydney, pp. 11–12.

Trustees of the Australian Museum, 1963. Report of the Trustees of The Australian Museum for the year ended 30th June, 1963, The Australian Museum, Sydney.

Trustees of the Australian Museum, 1973. Report of the Trustees of The Australian Museum for the year ended 30th June, 1973, The Australian Museum, Sydney. 344

van Leeuwin M, 1995. the origin and growth of New South Wales museums 1821–1880. MA (Hons) thesis, School of History, Philosophy and Politics, Macquarie University, Sydney.

Various, 1997. ‘Toward a natural history museum for 21st century’, Museum News, vol. 76, no. 6, pp. 38–49.

World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), 1987. Our Common Future, Oxford University Press, New York.

Worts D, 2006: ‘Fostering a Culture of Sustainability’, Museums and Social Issues, vol. 1, no. 2, Fall, pp. 151–172.

Yanni C, 1999. Nature’s museums: Victorian science and the architecture of display, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.