11

Applying multiple literacies in Australian and Canadian contexts

Diana Masny

University of Ottawa

David R Cole

University of Tasmania

As human beings we marvel at a dance performance, a musical recording, a novel, a film. For instance, take pieces of metal that come together to form a free-standing sculpture. Metal, as in music, dance or film, is a free-flow matter (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). As it stands there, what does metal do? It takes on expressiveness. Similarly, multiple literacies that involve reading the world, word and self take on expressiveness. Words on paper, musical notes on a staff take on sense, expressiveness.

Light, colour, sounds, lines and textures are powers that allow us to perceive worlds but each one is perceived through connections. As Colebrook states (2006, p103), we have colours because of the force of light and sensations that encounter each other just as we have the texture of a canvas through the encounters of light with depth and thickness. Similarly, literacies, through the encounters of letters and words with paper or with a computer, and encounters of notes on a musical staff or sounds that come together, are powers that allow us to perceive/read the world, word and self. It is from continuous investments with these connections that literate individuals are effected. Through a multiple literacies theory such as the one presented in this article, there is potential to release literacy from its privileged position as the printed word by not allowing it to govern all other literacies. In this way, literacies open themselves to what is not already given.

In this article, we foreground Masny’s Multiple Literacies Theory (MLT). Within this perspective, literacies are processes and from investment in 191literacies as processes, transformations occur and becoming other is effected. There are, however, other perspectives on literacies that have been foregrounded, namely New Literacies Studies and Multiliteracies. First, this article is devoted to a brief overview of the New Literacies Studies. Second, the Multiple Literacies Theory developed by Masny (2001) is presented. Third, MLT is linked to Australian education in language and literacies. It includes a discussion of the differences between Multiliteracies (Cope and Kalantzis, 2000) and MLT. Fourth, a case study application of MLT in research in Australia is provided. Fifth, MLT is applied to policy, teaching and research in Canada. Sixth, Masny reconceptualises MLT. Concepts developed within MLT are paradigmatically derived from Deleuze (1990, and 1995) and Deleuze and Guattari (1987, 1994) and presented. Seventh, a case study application of MLT in research in Canada follows. The final section is open to possibilities for lines of flight to create and transform experiences, thereby becoming other than through reading of the world, word and self, i.e. multiple literacies.

New literacy studies (NLS)

Before presenting the Multiple Literacies Theory (MLT), we want to point out that in the research on literacy, important contributions have been advanced by many. I want to focus on the New Literacy Studies (NLS) in order to argue that the paradigmatic position held by NLS is different from the paradigm espoused by MLT. Then, I will present MLT.

The New Literacy studies (Barton, Hamilton and Ivanič, 2002; Gee, 1996; Kim, 2003; Street, 1984, 2003), propose a definition of literacy that takes into account participants’ cultural models of literacy events, social interactional aspects of literacy events, text production and interpretation, ideologies, discourses and institutions (Baynham, 2002). The term ‘event’ within NLS is adapted from Heath (1983) and ethnography of communication. An event refers to any occasion in which engagement with a written text is integral to participants’ interactions and interactive processes (Heath 1983, p93). Texts that involve the interaction between verbal and visual are to be understood as multimodal (New London Group, 1996). The terms, events and texts, 192have been highlighted so as to understand how they are used within NLS.

While there might be surface similarities, in terms of their approaches to the study of literacies (in the plural) from an ideological perspective that sees them as situated historically and socially, they are distinctive in a number of important ways. As you will see shortly, these distinctions are not so much superficial differences between the NLS’s ideological model and MLT, rather they arise in deeper paradigmatic questions that underlie these two perspectives – this point will be raised again in MLT in the Australian context.

Conceptualising multiple literacies theory (MLT) 1997–2002

MLT was devised with a more critical perspective for social justice (Masny and Ghahremani-Ghajar, 1999). In this version, the concept of literacies refers to literacies as a social construct. As such, literacies are context-specific. They are operationalised or actualised in situ. They take on meaning according to the way a sociocultural group appropriates them. Literacies of a social group are taken up as visual, oral and written. They constitute texts, in a broad sense, that interweave with religion, gender, race, ideology and power.

An individual engages literacies as s/he reads the world, reads the word and reads her/himself. Accordingly, when an individual talks, reads, writes, and values, construction of meaning takes place within a particular context. This act of meaning construction that qualifies as literate is not only culturally driven but also is shaped by sociopolitical and sociohistorical productions of a society and its institutions.

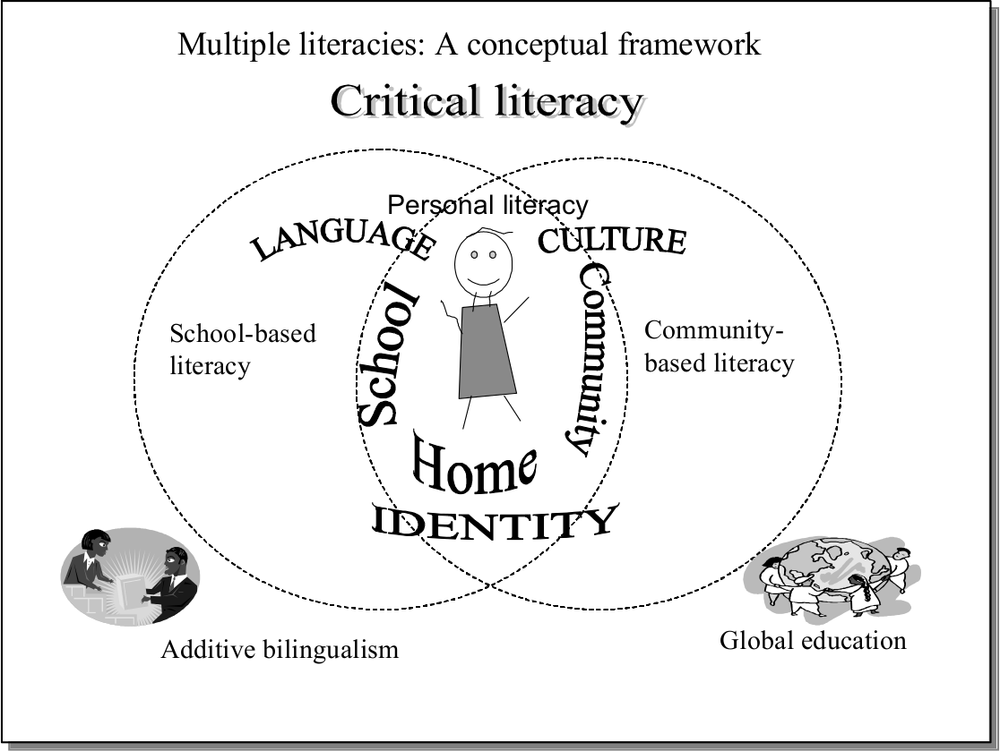

Figure 11.1 presents several literacies which are described below. They are community-based, school-based, personal and critical literacies (Masny, 2005).193

Figure 11.1 Multiple literacies: a conceptual framework

Multiple literacies

In this conceptual framework, the individual is reading the world, the word and self in the context of the home, school and community (local, national and international). This entails on the part of the individual a personal as well as a critical reading.

- Personal literacy. This framework for multiple literacies corresponds to a worldview in which the individual is immersed in different societal settings (school, home and community) shaped by social, political and historical contexts within that society. Personal literacy focuses on reading oneself as one reads the world and the word. It is within that perspective that personal literacy contributes to the shaping of one’s worldview. It is a way of ‘being’, based on construction of meaning that is always in movement, always in transition. When personal literacy contributes to a way of becoming, it involves fluidness and ruptures within and across differing literacies. S/he who reads the world and the word is in a process of becoming, that is, the person creates and gives meaning to that process of becoming in relation to texts. Text is assigned a broad 194meaning to include visual oral, written and possibly tactile forms (Masny, 2001).

- Critical literacy. No reading of the world, the word or oneself could take place in any significant manner without a critical reading or reading that calls on reflections (of texts). For many researchers, the work of Freire (Freire & Macedo, 1987) comes to mind when referring to reading the world and the word. His work has inspired many researchers. As well, there have been conceptual frameworks that are linked to critical literacy such as critical theory and critical feminist theory. The concept of critical literacy espoused by Freire is paradigm specific. The conceptual framework is situated within modernity. His theory of critical literacy is a theory of practice that serves to liberate and transform individuals by attending to a sense of betterment of the individual. Central to Freire’s notion of critical literacy is that socio-economic structures are poised to mainstream OR marginalise individuals. In creating links with critical theory, Friere’s concept of critical literacy creates a context for conscious examination of power relationship based on historical, political and social conditions at a particular time and space (within a particular community).

- Community literacy. Community-based literacy refers to an individual’s reading of literate practices of a community.

- School-based literacy. School-based literacy refers to the process of interpretation and communication in reading the world, the word and self in the context of school. It also includes social adaptation to the school milieu, its rites and rituals. School-based literacy emphasises conceptual readings that are critical to school success. Such literacies are mathematics, science, social sciences, technologies and multimedia.

MLT in the Australian context

In Australia since the 1990s, the social literacy movement of Multiliteracies has been steadily gaining increased leverage and power (Unsworth, 2001). Whilst MLT does share many similarities with multiliteracies as a set of organising principles for literacy provision, it also has major differences that we shall explore here. Unsworth’s (2001) and the New London Group’s (1996) models of multiliteracies have 195been consistent enough to drive the implementation of multiliteracies in Australia, and they act as comparative devices to MLT for this section:

- Multiliteracies are philosophically based in phenomenology (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000), whilst MLT is based in transcendental materialism (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). Whilst this philosophical difference between the two approaches may seem to be trivial at the coal-face of literacy work, it has profound effects for both systems. The multiliteracies camp argues that the social agenda for literacy should be in experience. MLT would counter that the social agenda of literacy is in the many aspects of life that flow through the subject and constitute memories, desire and the mind. As such, experience is extremely difficult to render as a stable category when examining exactly which aspects of life determine literacy learning according to MLT. The philosophy of multiliteracies maintains the stable category of experience, especially when contrasting its construction of literacy with respect to previous iterations of literacy that relied heavily on print literacy practices. It says that the new literacy learning experiences are dominated by the media, which should be replicated in our design of literacy curricula.

- Technology is of fundamental importance in multiliteracies, whereas it is of equal importance with every other contemporary literacy practice in MLT. The use of multiliteracies encourages literacy teachers to engage with technology in every aspect of the literacy learning program, as it prepares students for the technological and global workplace (Cope & Kalantzis, 1995). MLT will use technology wherever necessary, but does not allow its use to be a dominant or overriding narrative with respect to contemporary literacy.

- Power is distributed differently in the MLT and multiliteracies models of literate behaviour. In MLT the emphasis is very much on local interactions causing changes and micro-systems that directed power from the bottom-up. In multiliteracies, the focus on intelligent design spreads as a system property that guides all participants to work towards the globalisation of literate behaviours and ultimately the power of corporations.

- Multiliteracies encourage communities of learners, whereas MLT promotes action in 196learning. This action may come together in terms of a specified community, yet the actions that MLT produces are disparate and complex, and not defined by any preconceived agenda. The meaning that one may take from MLT action learning is invariably communal (Goodchild, 1996); however, these meanings are not fixed in a standard democratic or civil direction, as is the case with multiliteracies.

- Creativity takes on a fundamentally different orientation in MLT and multiliteracies. MLT relies on the random collisions of effects (Parisi, 2004), whereas multiliteracies prioritise organised and structured projects. Multiliteracies use interdisciplinary curriculum methods to encourage students to think holistically and to link knowledge areas. MLT works through local knowledge to produce moments of inspiration and art (Deleuze, 1995).

- Otherness, strangeness and alienation are included parts of the MLT system, as they may be explored through personal literacy (Fiumara, 2001) and affect; whilst multiliteracies will tend to shut out such considerations through communities of practice working towards pre-defined social goals.

The combined difference of MLT as opposed to multiliteracies as a basis for Australian literacy is that it is a starting point that works multiplicity fully into the system. This means that it has direct consequences for immigrants, indigenous populations or any marginalised community. It transforms the ways in which the mainstream works, as it tends to bring the random forces that are in play in the system into the centre. For example, the continued controversies that surround boys and literacy would be resolved through MLT by constructing units of work that inculcate boys’ desire into the machinery of the literate practices. This does not mean excluding girls’ desire from study, but works to preserve male affect in the classroom to help the boys build their literacy. This is against a backdrop of girls often being more articulate and expressive in their language usage when it comes to emotion and empathy than their young male counterparts (Graham, 2007).197

Case studies using MLT: Australia

Tasmanian self-recorded literacy videos

During 2006, students in northern Tasmania from grades 7–9 (age 11–14) were asked to take part in literacy research. The four schools that accepted the invitation to join in with the research were public institutions from an Australian country town environment. The students were asked to reflect on their literacy learning and make videos articulating their understanding of their literacy progress (n=45). They have used cameras attached to computers in a variety of environments, ranging from a computer at the front of the class, to a computer in a quiet room next to the library. The preliminary results from this research may be analysed using the Deleuze & Guattari empirical framework (Deleuze, 1995), which is an analysis of the sensible and non-sensible aspects of research, the integrated use of experimentation above and beyond the fixed terms of pre-defined categories. This analysis represents a playful and multilayered representation of the self-recorded literacy videos of the students. It is related to MLT through the construction of cam-capture literacy (Cole, 2007) and the following categories are unstable and interlinked cam-capture middle school zones:

- Boredom. The videos have elicited the deeply felt emotion of boredom – it permeates the whole of the literacy practices in all of the schools as the students see them. Boredom is not a superficial surface effect of education, but exists on every level of their life at school. It could be said that it is vital to them as an organising and originating principle for the type of literacy that they do at school.

- Time. The pace of the videos differs dramatically from student to student. Some rush through their pre-prepared speech at such a rate of knots that their words are barely audible. Others speak so slowly and deliberately that the videos seem to be recorded at half-speed. Few students are able to talk naturally and directly at the camera.

- Face. Many of the students had prepared their images in advance before the video shoot. The girls had put on make-up, boys brushed their hair. The videos only frame the face and shoulders of the students, so they have concentrated on these parts of their bodies to represent themselves. Students preferred to be framed in profile by tilting their heads to one side of the camera as they thought that this looks cooler.198

- Inarticulation. This research has proved that teenagers have great difficulty in articulating their literacy learning practices. If given direct questions to answer such as: What helps me to get better at literacy? They were left speechless. If they were asked: What am I good at in literacy? They would say reading or writing. Some would follow-up their comments with – I’m bad at spelling!! Very few had the ability to critically analyse their abilities in literacy in any depth.

- Teacher intervention. Several teachers, who thought that the students were not taking the research seriously enough, sat by the computers and quizzed their best literacy students about what they had just been studying in literacy. These videos resemble reading comprehension sequences, with the students mechanically responding to prompts. The students register noticeable relief and satisfaction if they think that the teacher is pleased with their performance.

- Chaos. There are videos taken by students during recess. These involve tapes of dancing; making shapes on camera with their bodies; moving the camera to look around the room quickly or in rhythmic bursts; laughing at other students in the room whilst filming them; and random filming with a disconnected narrative from a student off-camera.

- Self-consciousness. Whether speaking about how repetitive they thought their literacy lessons were, or how they could get better at writing, the students all displayed self-consciousness. This means that they were worried about how the video would come out, and aware that somebody was going to view it – namely the researcher!

MLT doesn’t give us a magic wand to make these students all suddenly value their literacy lessons! It does give us a perspective whereby these ideas may be listened to and understood. Furthermore, MLT is an organising principle that shows us ways of using these student reactions to literacy practices as starting points for learning (Doecke & McClenaghan, 2004). For example, the exploration of boredom as the bedrock of school literacy should act as a springboard to act otherwise and engage ways to articulate the tenets of boredom in every aspect of life.199

MLT in the Canadian context

- Policy. Masny elaborated a conceptual framework of multiple literacies that was adapted as a literacies model for the actualisation of French so that through its educational system, Alberta’s French language community could thrive. The rationale for adopting a curriculum that took up multiple literacies was that, at the time, the curriculum promoted mostly school-based literacy and provided little opportunities for legitimating other literacies (e.g. personal and community literacies). Examples are the kindergarten programs both in immersion (1999b) and in French First Language (1999a) developed by the Alberta Ministry of Education, and the kindergarten immersion program in the social sciences developed by the Manitoba Ministry of Education (2003). In addition, multiple literacies also became a foundational element for Affirming Francophone Education in Alberta (2001).

- Teaching practice. In 2003, the Canadian Council of Ministers of Education developed a Pan-Canadian project for French language schools. The training kit assists teachers from Kindergarten to Grade 2 in demonstrating the importance of being proficient in French in order to develop multiple literacies in French: personal, critical, school and community. In a French-minority language setting in Canada, only in a minority of homes will you find both parents speaking French with their children. Most times, both languages (French and English) are spoken. Sometimes, no French is spoken at all. Yet, parents who attended a French-language elementary school are considered rights holders of Section 23 of the Canadian Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms. As such, they have the right to send their children to French language schools. More recently (2006), the Canadian Federation for adult literacy in French has developed an intervention program for family literacy. The foundation for this program is based on developing multiple literacies (personal, school and community).

- Research. Most recently a four-day workshop funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Official Languages Program focused on presenting theoretical and applied research conducted in French Canada using Masny’s Multiple Literacies framework in relation to the arts (music), science, mathematics, children’s literature, early childhood, family literacy, 200and health, in the context of the home, school, and community. The purpose of the workshop was to establish a community dialogue between Canadian university and community researchers, and government (federal, provincial, school boards) and community agencies (national and regional) on the role of Multiple Literacies in policy making, program and curriculum development in governmental and non governmental institutions. The proceedings will be published in 2008.

Conceptualising MLT 2002–

The framework is a constant becoming – indeterminate and not fixed. The MLT framework underwent transformation to one mainly influenced by Deleuze (1990, 1995) and Deleuze and Guattari (1987, 1994), in particular as multiple literacies tie into such concepts as desire, subjectivity, difference, investment, reading and deterritorialisation. Each concept will be briefly described in the next section.

Accordingly, Masny’s MLT refers to literacies as texts that take on multiple meanings conveyed through words, gestures, attitudes, ways of speaking, writing, valuing and are taken up as visual, oral, written, and tactile. They constitute texts, in a broad sense (for example, a musical score, a sculpture, a mathematical equation) that fuse with religion, gender, race, culture, and power, and that produce speakers, writers, artists, communities. It is how literacies are coded. These contexts are not static. They are fluid and transform literacies that produce speakers, writers, artists, communities. The meaning of literacy is actualised according to a particular context in time and in space in which it operates. In short, through reading the world, the word and self as texts, literacies constitute ways of becoming with the world. The framework allows for multiple literacies to become other than and consider moving beyond, extending, transforming and creating different and differing perspectives of literacies (Dufresne & Masny, 2005). It is interested in the flow of experiences of life and events from which individuals are formed as literate.

In MLT, by placing the emphasis on how, the focus is on the nature of literacies as processes. Current theories on literacies examine literacies as an endpoint, a product. While MLT acknowledges that books, Internet, 201equations, and buildings are objects, sense emerges when relating experiences of life to reading the world, word and self as texts. Accordingly, an important aspect of MLT is focusing on how literacies intersect in becoming. This is what MLT produces: becoming, that is, from continuous investments in literacies literate individuals are formed.

Conceptual framework Conceptual glossary

Deleuzean epistemology and

- … the subject. Most research in education and in literacy learning operates within modernity and on the assumption of the autonomous thinking subject. The grounding of language, thought and representation originates with a rational human being who is often referred to as the centered subject in a world that can be subjectively constructed. Deleuze (1987) moves away from the foundation of the subject who thinks and represents. Rather, it is the subject who is the product of events in life. As a result, such reversal about the subject forces a change in discourse structure and conceptualisation about the subject. In short, “the subject becomes an effect of events in life” (Masny, 2006, p2). The subject is not in subject position actively controlling. The mind, one mode of becoming, is a site that connects and transforms the individual, thereby becoming other than.

- … investment and events. Investment is another term that is associated to other paradigms as well. In MLT, investment refers to connections of events stemming from experiences of life. Within Multiple Literacies Theory (MLT), events refer to “creations…selected and assessed according to their power to act and intervene rather than to be interpreted” (Colebrook, 2002a, pxliv). An event, according to Deleuze (1990), refers to life that produces lines of flight, moments that create ruptures and differences that allow creativity to take off along various planes, similar to a rhizome. It is from the continuous investment in literacies that individuals are formed as literate.

- … reading. Reading is about sense. Sense is not about interpretation; sense is an event that emerges (Colebrook, 2002). Sense is virtual. It is activated when words, notes and ad icons are actualised in situ and in interested ways. Take an example of the 202smell of coffee and it is four o’clock. The coming together of the smell of coffee and 4 o’clock disrupts (reading intensively) and brings on the thought of vacation (reading immanently). Sense expresses not what something is but its power to become.

- … becoming and difference. How do literacies work in becoming? Becoming implies indeterminacy, you might say that becoming is a product continuously producing while literacies are processes that form and shape becoming. The concept of becoming is central to MLT. Becoming is the effect of experience that connects and intersects. Transformations are continuous. What it once was is no longer. It is different. It is through transformation that becoming happens.

- … desire. Desire is an assemblage of experiences that connect and are constructed. Take for example, the smell of coffee at 4 o’clock. It could be the thought of a coffee break. It could be the thought of another vacation. For Deleuze (1987) desire is an effect of experiences in life that come together. The actual coming together, an assemblage of experiences creates a virtual experience which then could be actualised such as the coffee break or the vacation. The clock has both an actual dimension and a virtual one.

Case studies using MLT: Canada

Acquiring literacies involve different writing systems and create an environment for worldviews to collide because of the sociocultural, political and historical situatedness of learning literacies. Worldviews collide when different values and beliefs about language – about literacies – are introduced as a result of encounters with other literacies. Learning literacies does not take place in a progressive linear fashion. In a Deleuzian way, it happens in response to problems and events that occur in life experiences. Literacies are not merely about language codes to be learned. Learning literacies is about desire, about transformation, becoming other than through continuous investment in reading the world, the word and self as texts in multiple environments (e.g. home, school, community).

Methodology

The multiple literacies framework is the lens used to examine how competing writing systems in learning a second literacy transform 203children and become other than. Furthermore, putting a line through methodology indicates that the concept and the term are being deterritorialised and reterritorialised as a rhizomatic process that does not engage in methodological considerations in a conventional way. It resists temptations to interpret and ascribe meaning; it avoids conclusions.

The case study involves a 7-year-old girl, Cristelle, in Grade 2 attending a French language school in west Ottawa1. Her family lives in a mainly English-speaking middle class community with a predominance of technology companies. Cristelle’s father is unilingual English while her mother is bilingual, French and English. At home, French is used mostly around school work. Most of the time, the family speaks English. Cristelle was filmed during a French period. An interview followed based on the videotaping that was done earlier. Next, videotaping took place at home during meal time or play time and during reading and writing activities. An interview followed with the family.

Vignettes

Do not look to these vignettes as data and seek to find concrete proof of transformation. Data in the more traditional way is about empirical data. Deleuze and Guattari (1994) have moved away from empiricism because it supposes a foundation grounded on human beings who seek to fix categories and themes. They call upon transcendental empiricism. It transcends experience (immanence). It deals with perceptions and the thought of experience creating connections and becoming other than.

The analyses presented at the end of each vignette are informed by the MLT framework 2002. Square brackets indicate that the utterances are translated from French.

Vignette 1

| M | Euh, usually after school we’ll start off with French, to do the homework, euh I notice that we switch, I go back and forth and like I’m trying to keep it all in one language. But eum, when I go pick her up at the daycare she doesn’t want to speak French anymore. So I try and continue on in French. So right after school, going into homework exercise. (…) Eum, I when I remember I try to speak to her in French, if she answers me in English, like today we were at the grocery store, I just kept talking her in French, she’ll speak to me English, sometimes ‘cause I’ve noticed she’ll say a sentence like: «aujourd’hui [today] we were at the», like she writes it all up, so she does half and half, and I want her to, like she’d start a sentence. | |

| Cr | Who cares? | |

| M | And she switches to English. I’ll say: «continue en français [continue in French].» ‘Cause I don’t want her to give up. I want her to to continue so, if if I remember, I do, mostly right after school [***] morning [***]. | |

| R | … would you say for Cristelle, when it comes to both languages, she uses more of one than the other. | |

| M | Ya, definitely English. (Home 13 March 06) |

In the preceeding vignette, Cristelle’s comment is somewhat revealing. Is it an instance of wanting to unhinge the un/familiar, or perhaps deterritorialise what has been territorialised? Mother’s comments reveal tensions between wanting to have a sound base in French and yet recognising that one language, English, is used more often. From these language and literacy events in a family/community context, the parents and Cristelle are formed as literate and in this process transformed and becoming other than.

Vignette 2

Since this study focuses on perceptions of writing systems, Cristelle shares her views regarding writing.

| R | [what do you think about your story?] | |

| Cr | [that it’s a bit funny, and the drawing is funny] | |

| R | [it’s your drawing that’s funny. Yes, but your story, how do you find it?] | |

| Cr | [not so funny, because there aren’t many things that are funny]205 | |

| R | [what would need to be done for your story to be funny?] | |

| Cr | [funny drawings] | |

| R | [you would want funny drawings all over?] | |

| Cr | [yes!! (with great glee)] | |

| R | [but then there isn’t any writing. Is that what you want?] | |

| Cr | [yes] | |

| R | [you don’t want to write?] | |

| Cr | [I don’t want to write] | |

| (Class French activity 12 December 05) |

What reading of self is taking place? How is writing and drawing regulated in the classroom? It would seem that deterritorialisation of drawing has been reterritorialised as writing. The boundaries for Cristelle are no longer blurred.

Vignette 3

The reading of self seems to resonate with the perceptions that her mother has regarding Cristelle’s writing. [laugh]

| P | «Why does salad exist?» | |

| Cr | «Why does salad exist?» | |

| M | [why does salad exist?] | |

| Cr | [Mama is a birdhead.] | |

| M | [Mother is a birdhead. It was for interrogative sentences and she wrote, why salad exists and then when I corrected, she didn’t like it. She said, you want me to redo my homework. Because she is frustrated. I am ready to help her.] | |

| R | [Is she frustrated because she has errors or?] | |

| M | [She is frustrated, she wants to do the sentence in French and she uses oral English borrowings to do it.] | |

| M | So, I would say, I put you know: « d’où vient la salade »[where does salad come from], and she goes: «no, you have to write où», où avec le ‘u’ avec. [Then I say it doesn’t work that way. So then gets frustrated] | |

| M | J’ai dit: « non ça fonctionne pas comme ça »[I said it doesn’t work that way], so then she gets frustrated. I know it’s it’s partially me, it’s partially her, but I find that she gives up really easily when when she does writing exercises. [And at the moment it doesn’t really interest her.] (Home 13 March 06) |

206Are events and experiences resisting the normative flow and colliding? Are such events wanting to go beyond constituted forms? Thinking is only thinking when it is creative. “Life’s power is best expressed not in the normative but in the perverse, singular and aberrant” (Colebrook, 2006, p20). Is it from these events that Cristelle becomes and multiple literacies are the processes through which becoming happens?

Vignette 4

When an individual learns to read/write, the boundaries between what is acceptable and appropriate seem blurred. In the following vignette, Cristelle learns to write. Certain aspects of learning to read/write are connected with previous learning experiences. Other aspects are connected with associations that do not necessarily relate to the writing system or the conventional norm.

| R | [last time you had a discussion with Danielle the research assistant and you said you like funny things. What do you mean?] | |||||

| Cr | [I like to write like a see a big space] | |||||

| R | [would you show me how you wrote this?] video clip | |||||

| [h | m | C | ||||

| e | i | a | ||||

| l | s | l | ||||

| l | t | l | ||||

| o | e | o | ||||

| r | u] | |||||

| Cr | [I had one word here and then another there and I continued.] | |||||

| R | [what were you trying to say] | |||||

| Cr | [hello, my name is Callou] | |||||

| R | [and you chose to do it in this way] | |||||

| Cr | [because I told Anne, her classmate, to look and Anne said, Cristelle, this not the way to write.] | |||||

| R | [and you chose to write this way.] | |||||

| Cr | [yes and then after I erased it.]207 | |||||

| R | [why did you want to write this way?] | |||||

| Cr | [because I like to be funny.] | |||||

| R | [what made you change your mind like this and after you erased] | |||||

| Cr | [because Mrs Soneau (the teacher) was coming over to see me.] | |||||

| R | [when she comes to see you, what do you do?] | |||||

| Cr | [she comes to correct] | |||||

| R | [she comes to correct and … ] | |||||

| Cr | [she looks at my paper] | |||||

| R | [and what should you be doing?] | |||||

| Cr | [write a story, I mean you need to put the words together, stuck together] | |||||

| R | [and so this is what you have to do when she comes. And you don’t like to do that. What do you like to do?] | |||||

| Cr | [the same thing as that (pointing to the video clip)] | |||||

| R | [do you often do stories like this?] | |||||

| Cr | [no]. | |||||

| (Class – French activity 12 December 05) | ||||||

Is this also an instance of reading the world, word and self, in terms of flow of experiences? What more could Cristelle do given an opportunity? What creativity could unfold? Deleuze states that to create is to resist (1994, p110). Cristelle is creating through the responses of resistance (directionality in writing). Can such events become lines of flight? Colebrook (2002, pxliv) says that events, according to Deleuze, “are seen as creations that need to be selected and assessed according to their power to act and intervene”. As worldviews collide, it is out of multiple literacies that the learner is effected, that some literacy creations/experiences are foregrounded while others are eclipsed.

Where to …?

There are several questions with regard to literacy practices that permeate the research in Canada and Australia. In the Canadian study which focuses on how writing systems operate, the mother has her views and so does Cristelle and these views seem to be on a collision track. The mother’s worldviews in relation to writing could be aligned with normativity. The thought of colliding with Cristelle’s worldviews creates openings or the ‘inbetweenness’ that the mother speaks of (that is, the 208necessity of learning one language first well, and then the realisation that while French is tremendously important, much of what goes on in the house takes place in English). On the other hand, the resistance from Cristelle to writing is apparent. Cristelle’s vignettes provide the thought of worldviews colliding with normativity. These are experiences that transform and becoming other in untimely and unpredictable ways. Writing needs to be fun and amusing, and to mesh with her worldviews. While these experiences are connecting with each other, at times, there is resistance. Cristelle’s resistance is also about creating (hello mister Callou) (for more on resistance, see Dufresne, 2006).

In the Australian case study, like Cristelle, the students do not seem interested in literacy practices, or at least not school-based ones. Can boredom be a form of resistance, boredom as a response to normativity? Worldviews, that of the students, are colliding with the worldview related to school-based literacy. The video became many tools – some connected to making videos about their understanding of literacy, the others took them to an untimely place; tapes of dancing, making shapes with their bodies and using the camera to imitate rhythmic bursts. Was this an instance of seeking stability in their world? Would literacy practices legitimated in school constitute destabilisation? Was this in response to a problem in the making? They connected these sessions with their reading of the world and self. They became texts through the body shapes and rhythm. From investment in these forms of literacy, they are formed and transformed.

In both case studies, there are links to creativity. Thinking is only thinking when it is creative and going beyond already constituted forms. How do such investments create possibilities for becoming since investment in languages and literacies is an investment in difference, in becoming other than? Is it the thought of the blurred boundaries that are challenging views on acquiring multiple languages and multiple literacies?

The multiple literacies theory retained in this article becomes a way to examine how out of complexity and multiplicity, in untimely ways, differences are continuously transforming in becoming other than. In the words of Deleuze and Guattari (1994, p169): “We are not in the world. We become with the world”. In the context of this article, we become with reading the world, the word and self – multiple literacies. 209

References

Barton D, Hamilton M, Ivanič R (Eds) (2002). Situated Literacies. London: Routledge.

Baynham M (2002).Taking the social turn: The New Literacy Studies and SLA. Ways of Knowing Journal, 2: 43–68.

Canadian Council of Ministers of Education (2003). Pan-Canadian French as a First Language Project: La trousse de francisation [French actualization kit for teachers from Kindergarten to Grade 2]. Toronto www.cmec.ca/else/francisation/cd-rom/inc/info/litteraties.htm

Canadian Federation for Adult Literacy in French (2006). Foundations for the intervention in Family literacy: the case for developing multiple literacies. Ottawa.

Cole D R (2007). Cam-Capture: An Eye on Teaching and Learning. In J Sigafoos and V Green (Eds), Technology & Teaching: A Casebook for Educators, (pp55–68). New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Colebrook C (2002). Deleuze. New York: Routledge.

Colebrook C (2006). Deleuze: A Guide for the Perplexed. London: Continuum.

Cope B, Kalantzis M (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. South Yarra: Macmillan Publishers.

Cope B, Kalantzis M (1995). Productive Diversity: Organisational Life in the Age of Civic Pluralism and Total Globalisation. Sydney: Harper Collins.

Deleuze G (1990). The Logic of Sense. (M Lister, Trans. with C Stivale). New York: Columbia University Press.

Deleuze G (1995). Negotiations 1972–1990 (M Joughin, Trans.). New York: Columbia University Press.

Deleuze G, Guattari F (1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism & Schizophrenia Part II (B Massumi, Trans.). London: Athlone Press.

Deleuze G, Guattari F (1994). What is philosophy? (H Tomlinson & G Burchell, Trans.). New York: Columbia University Press.210

Doecke B, McClenaghan D (2004). Reconceptualising experience – growth pedagogy and youth culture. In W Sawyer & E Gold (Eds), Reviewing English in the 21st century, (pp51–60). Sydney: Phoenix Education.

Dufresne D (2006). Exploring the processes in becoming biliterate. International Journal of Learning, 12(8): 347–354.

Dufresne T & Masny D (2005). Different and differing views on conceptualizing writing system research and education. In V Cook et B Bassetti (Eds), Second Language Writing Systems. Clevedon, Buffalo: Multilingual Matters.

Fiumara G C (2001). The mind’s affective life; a psychoanalytic and philosophical inquiry. Hove: Brunner-Routledge.

Freire P, Macedo D (1987). Literacy. Westport, Conn: Bergin &Garvey.

Gee J P (1996). Social linguistics and literacies: ideology in discourses, 2nd Edn. London: Taylor & Francis.

Graham L (2007). Done in by discourse … or the problem/s with labelling. In M Keefe & S Carrington (Eds), Schools and Diversity, 2nd Edition, (pp46–65). Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Education Australia.

Goodchild P (1996). Deleuze and Guattari: An Introduction to the Politics of Desire. London: Sage Publications.

Heath S B (1983). Ways with words: language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kim J (2003). Challenges to NLS – Response to “What’s ‘new’ in New Literacy Studies” [Electronic version]. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 5. www.tc.columbia.edu/cice/articles/jk152.htm

Kress G, van Leuwen T (2001). Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Meia of Contemporary Communication. London: Hodder Arnold Publication.

Masny D, Ghahremani-Ghajar S S (1999). Weaving multiple literacies: Somali children and their teachers in the context of school culture. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 12(1): 72–93.211

Masny D (2001). Pour une pédagogie axée sur les littératies [Toward a pedagogy based on literacies]. In D Masny (ed), La culture de l’écrit: les défis à l’école et au foyer, (pp15–26). Montréal: les éditions Logiques.

Masny D (2005). Multiple literacies: An alternative OR beyond Friere. In J Anderson, T Rogers, M Kendrick & S Smythe (eds), Portraits of literacy across families, communities, and schools: Intersections and tensions (p71–84). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Masny D (2006). Learning and Creative processes: a Poststructural Perspective on Language and Multiple Literacies. International Journal of Learning, 12(5): 147–155.

Ministry of Education (Alberta). (1999a). Kindergarten French First Language programme www.education.gov.ab.ca/french/maternelle/francophone/fr_mat.pdf

Ministry of Education (Alberta). (1999b). Kindergarten immersion programme. Edmonton http://ednet.edc.gov.ab.ca/french/Maternelle/immersion/intro.pdf

Ministry of Education (Alberta) (2001) Affirming Francophone Education: Foundations and Direction. Edmonton. www.education.gov.ab.ca/french/m_12/franco/affirmer/CadreENG.pdf

Ministry of Education (Manitoba) (2003). Immersion Kindergarten Social Sciences curriculum. Manitoba. www.edu.gov.mb.ca/frpub/ped/sh/dmoimm_1re/introduction.pdf

New London Group (1996). A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1): 60–92.

Parisi L (2004). Abstract Sex: Philosophy, Bio-technology and the mutations of desire. London: Continuum Books.

Street B (1984). Literacy in theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Street B (2003). What’s new in the New Literacy Studies? Critical approaches to literacy in theory and practice. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 5(2): 77–91. www.tc.columbia.edu/cice/Archives/5.2/52street.pdf

Unsworth L (2001). Teaching multiliteracies across the curriculum: Changing contexts of text and image in classroom practice. Buckingham: Open University Press.

1 This study was funded through a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and the Official Languages Dissemination Program.204