13

Eyes in the back of our heads: reading futures for literacy teaching

Jo-Anne Reid

Faculty of Education, Charles Sturt University

In this presentation, I want to challenge you – on the last day of this conference called Future Directions in Literacy – to think back over the past few days and to review and consider what you have heard. I ask you to reflect on the key messages you have taken from the presentations you have listened to, the interactive sessions you have participated in, and the discussions you have had with your friends and colleagues who have shared this experience. I want to provoke you a little, to think, to consider what it all means, this talk about literacy directions into the future, and the challenges that Leonie Rowan, Barbara Comber, Peter Freebody and Jackie Marsh have thrown to you in this slot each morning in what has indeed been an international conversation about literacy and literacy teaching.

I base my argument on a claim that the work we do as teaching professionals is work that is captured in the textual practices of our profession. In particular, I believe that the work we do in planning and programming what we want to happen in our classrooms – each day, each week, each term and over the whole year that we spend with a particular group of children in our care – is key to who we are as teachers. Our programs are the realisation – the traces – in print, or diagram or scribbled notes, of our intended practice – the best that we can aspire to. They are the means by which we represent ourselves to ourselves – either as the sorts of professional subjects who take up prescribed curriculum and adapt it to the needs of the particular children in our classes, or the type of teachers who teach to a syllabus that was not designed for any single one of them. We use them to think through what we want to do with literacy with our students, and how we might do them in particular ways. The nature of the things we plan to do and the ways we plan to do them, changes from year to year, group to group, day to day, but it is usually informed by current theories about what is 235good literacy practice at any particular time. And this is the argument I make here: that what we currently understand as literacy teaching is different from what teachers understood as literacy ten or a hundred years ago, but that it is not totally different, and that in some ways it is not very much different at all from what we have been doing in the past. And so, given that, how do we see our future directions? In particular, as I started by saying, how do we work with the ideas presented by key literacy researchers to divine the directions that will be best for the children we teach?

These are key words for me in this presentation: ‘seeing the future’, ‘divining the directions that are best to take’ for teaching children the things they need at the present time to be literate social subjects. By this I mean that we are teaching them to be able to function effectively in the multimodal literacies that characterise our daily formal, social and business interactions. A literate social subject is a person literate in a range of these media and able to use them for pleasure and creative expression. Even more importantly, as we face an uncertain future in relation to climate change and economic instability, we want our students to be literate in terms of being able to access the knowledge, thinking and artistry of our fellow human beings through our use of these media. Just like me, you may find that words like ‘seeing the future’ bring to mind the distinctly unscholarly activity of fortune telling – and indeed my plan for today’s talk is built upon the discourse structures that this particular form of ‘telling the future’ provides. I want to use the thinking of the Tarot – not as a mystic or arcane ritual, but rather as a scaffold for thinking, and a technology for planning future directions in literacy. I want to use it to highlight the things that teachers of literacy might well consider for our practice as literacy professionals in primary and secondary schools.

The history of the Tarot card is not agreed upon by everyone, but it seems that use of this deck of 78 playing cards was first recorded in the north of Italy in the 15th century where it was used to play a game similar to that we now know as Bridge. The designs on the sets of cards that were taken to other European countries inspired people there to add social narratives to these images, and allowed the element of chance (inherent in all understandings of playing cards), to transform the Tarot 236into something else than just a game. In the hands of mystics and storytellers, it became used as a system of telling fortunes. This was done by means of the drawing of cards, ‘by chance’ in response to particular sets of scaffolding questions that were deemed to suit the needs of those who seek assistance in making decisions in their lives.

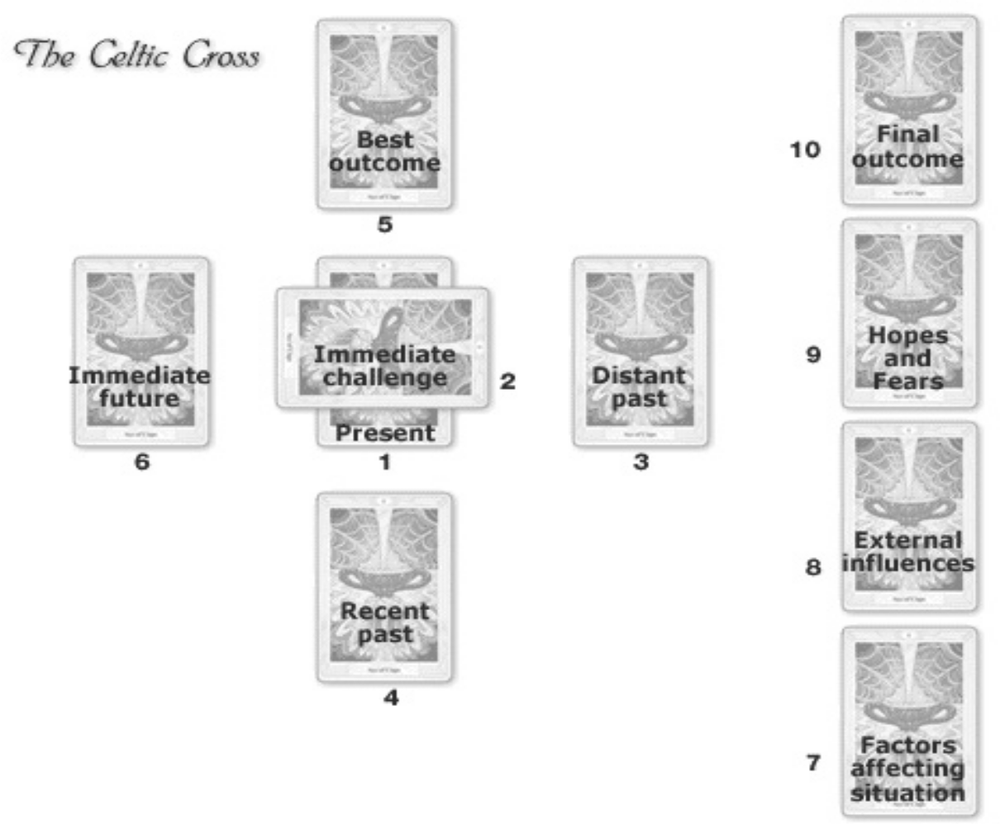

The Tarot pack can be laid out in any one of a range of ritual structures in order for a fortune teller to ‘read’ the story in the cards – the only requirement is that the layout is seen as a guide only. Where a clear meaning is not apparent either to the fortune-teller or to the ‘Querent’, the person whose quest it is to find an answer and a guide for the directions they will take for the future, other cards may be used as needed, to amplify and extend the story that unfolds. For my purposes here today I will use the heuristic structure that Tarot readers call the ‘Celtic Cross’. The nature of the cards themselves, and their particular symbolic meanings, is neither necessary nor important for my purposes here – as I am not here to engage in telling the future, of course.

I am using the Tarot simply as a technology, to make the argument that this structure for thinking is a useful heuristic for giving careful consideration to important questions like literacy education – simply because it provides a structure that requires us to look back as well as forward – to our history as well as our future. And this is what I want to argue – that we will not change directions in literacy teaching unless we move forward with a clear sense of what we are changing from, and how, and why we need to change. I could have used the Aristotelian Table of Invention, for instance, to lay out the boundaries of this question, but here, today, because I want you to remember, I am telling our future direction in literacy in this way.

Here (below) is the layout of the Tarot reading we are about to make, as we seek an answer to what it is we should be doing as we go about the teaching of literacy for the rest of this term, or this year. We only ask the Tarot to foretell the future to give us this sort of structure – to support us in our decision to act in a particular way. If we already know that we are on the right path, of course, and we already know all there is to be known about what is the best literacy instruction for the children in our 237care, we probably wouldn’t need to read this Tarot – and we certainly wouldn’t need to come to a conference such as this.

Here is what the Tarot asks us – to lay out, on the table, the situation under consideration as it relates to ourselves as Querent, in search of this answer. The very first card that is laid down represents ‘the present’ – the situation at hand, and where we must always begin. The reading as a whole is made in terms of this card in relation to all the others, setting out the conditions for ‘foretelling’ or understanding future practice – what will, or may, happen. In this way, the Tarot layout can be seen as a scaffold for planning – for programming the work that will happen on our classrooms, and for understanding the directions that we will take in the next few years as a profession. This of course means that it can help us plan the sorts of conversations we will need to have and the support we may need to provide to our colleagues and student teachers over this time as well. It can help us – in short – predict the future directions in literacy that will be the most productive in achieving fair, just and equitable access to all. That is the question we bring to this particular Tarot reading (adapted from Angel Paths Tarot, www.angelpaths.com), and of course it is the ‘big’ question we bring to the act of programming each time we set out to plan a program of work for a group of learners.

Card 1: The present.

Bill Green argues that thinking historically about English teaching is “easier said than done”, as it always means “reassessing our present, as an always-already problematic form of presence, and it also means thinking about and speculating on the future, as a space of difference and danger, promise and impossibility” (Green, 2003, p139).

This first step in our Tarot reading for the future asks us to be mindful of where we are, who we are working with, what are their, our own, needs and strengths. It asks us to open our thinking to the associated considerations that immediately complicate this present and make it far less simple and understandable. Starting here in the present means looking closely at our ‘situation of practice’ in all its complexities. As I understand it, the project of histories of the present is to make the present a “strange rather than a familiar landscape” and unsettle the things we take for granted (Green & Reid, 2002, p37).238

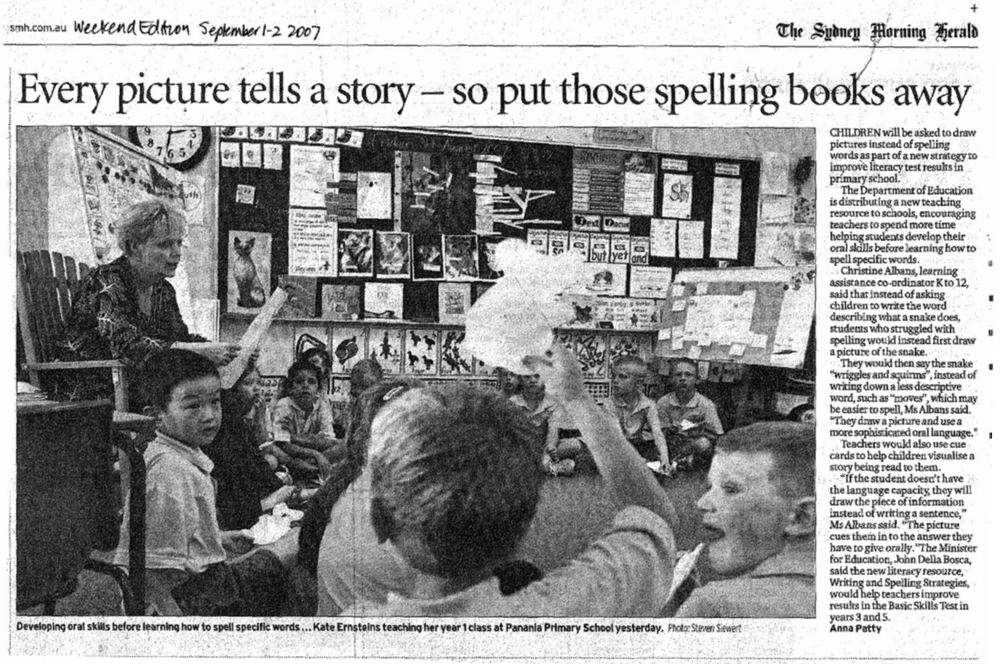

For instance, just this weekend, the following article appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald:

239Here is a present depicted. The story begins with the words, “Children will be asked to draw pictures instead of spelling words as part of a new strategy to improve literacy test results in primary school”. It goes on to note that “[t]he Department of Education is distributing a new teaching resource to schools, encouraging teachers to spend more time helping students develop their oral skills before learning how to spell specific words” (Patty, 2007, p11).

This is a ‘present’ for literacy teaching that contrasts greatly with the ‘presents’ I have witnessed in many of the classrooms visited in the course of my research. I have increasingly become concerned about the nature of some present-day literacy experience on offer to children in some classrooms during a study that evaluated the effects of bi-dialectal language use in classrooms with high numbers of Aboriginal children for the DET (Reid & Owens, 2005). In an interview with an eight-year-old, the following conversation took place:

| I: | What sort of story would you write? Do you go fishing, or what do you do? | |

| L: | I caught … I’m a dropper. You’ve got to get on your boat and then tie this thing on a real big … if there’s a willow tree then tie it around it. And I wanted to put on the egg, and then the next morning on the dropper I got a six-, seventeen pound cod and then Onna, my dad’s friend, went in and got it and put it in the boat. | |

| I: | Do you ever write stories like that in the classroom? | |

| L: | Yeah, we have sometimes. | |

| I: | When you write your stories in class, have a little think – what’s the first thing you do when you write a story? | |

| L: | I can’t do it. | |

| I: | Before you even start writing, do you think about things in your head first? | |

| L: | Yeah, what I’m going to write. | |

| I: | You think about things you’re going to write? And what about the ARA; what about Nan, did she help you think about things? | |

| L: | Yes, she says, “Oh, we’ve got to put that in” or “You should have put this”, and then she says it. | |

| L: | And what does she say things like?240 | |

| I: | Like … | |

| I: | Say you were writing a story about catching a seventeen pound cod, what would she tell you to write? | |

| L: | That I should say … write, “who caught the fish”. |

Here, eight-year-old Lyall, a Wiradjuri boy from the Murray-Darling Basin is showing a Wiradjuri researcher his writing, and talking about how he goes about writing in his classroom. There, spelling the words correctly is important, and the work he is talking about bears no relation to either his lived experience or the richness of the world he inhabits outside of it. My concern is that the text these two are discussing, the writing Lyall is asked to do now that he is in Year 3 and needs to be spelling, punctuating, making language choices appropriate to the texttype he is producing, is actually as follows:

| BOO. My monster is a hairy, green, spotty, good monster. He is named BOO and he has lots of spiky fur. He scares big, ugly people. He is my best friend. |

Here, in Lyall’s final copy, which is his fourth draft of this text, worked on for over a week, and carefully typed up on Friday, we see evidence of what I think might be pretty toxic literacy practices for Lyall. Is it significant that he hasn’t ‘bothered’ to put his name on this text? What is this text doing? What is it for, except to practise adjectives, commas, and formal constructions of English grammar such as the passive formulation of ‘is named’. This seems a very strange construction – and it places the relationship between Lyall and ‘his’ monster at some considerable distance, in fact removing Lyall from his sentence altogether. Lyall’s writing, his literacy, has been made safe.

The will to safety in literacy teaching characterises our present, I am afraid. We have been convinced by the rhetorics of science, and the documents that tell us we must drill the children in phonics and text-types before they can tell their stories, and that some stories have more value than others, and some should not be told in the classroom at all. In the end, we have come to a present where many teachers are afraid to 241take risks, or take a chance, because we are not sure what will happen. Perhaps if we continue the Tarot we will find out.

Card 2: The immediate challenge

This step asks us to interpret and articulate (to ‘lay on the table’) what it is that we see to be the immediate challenge as we see it, and as we set out to take the action we want to take. This challenge might not be an issue directly related to the question, of course, it might be something that impacts on our ability to move quickly, or to do the things we want to do in our classroom. It may be the need to ask permission from the Principal to try something different, for instance, and to establish a different relationship with the AEA, or to address my own lack of skill in online media production – but this challenge will need to be addressed, as it will not go away. Knowing that it is there allows us to proceed with this knowledge in our consciousness, and to ensure we plan to address it as part of this process.

On the other hand, though, facing these challenges, small as they may seem when the size of a Tarot card, means stepping out of our safety zone – and of course this means that very often we put them off, leave them till later, once we have started our journey – and ‘planning to address them’ does not mean that they are addressed. It is easier not to challenge often, particularly when your colleagues, your school, the media you use over breakfast or in the car on the way to work, all indicate that you need evidence to show that what you are feeling you might want to do is sound and worthwhile literacy practice.

In her critical account of research which claims to prove that knowledge of sounds, or phonemic awareness, is the foundational building block of early literacy, and which is the ‘evidence’ upon which whole systems have based information for teachers, Denny Taylor writes:

In positivistic research there is a total lack of recognition that literacy […] is embedded in everyday activities, or that the use of complex symbolic systems is an everyday phenomenon constitutive of and grounded in the everyday lives of young children and their families (Taylor, 1998, p223).

242Lyall does not get to embed his literacy in his life experience. He already knows how to select adjectives (and modify them, according to his social purpose of impressing his listener) very well in his oral language, in the story he tells about his fishing prowess. Allowing him to learn to write or communicate his enthusiasm and excitement in a range of modes may be more successful – may help his teacher achieve the goal of improving literacy outcomes for Lyall just as much as other children.

Changing the literacy program in Lyall’s classroom will need us to talk to the Principal, and of course that will require us to explain WHY we want to make the changes we are suggesting. And that, of course, will require us to be able to argue a rationale for our case, one that is based on evidence and experience, from our own professional knowledge base as literacy teachers.

In Michael Singh’s (1992) paper on the work of Sylvia Ashton-Warner, he makes the argument that her practice is more clearly ‘professional’ practice than that of teachers who simply follow the rules and syllabus set down by their employers without consideration of their situation of practice. He suggests that there are three “closely-related criteria [that] are normally employed to distinguish a professional from a nonprofessional occupation”:

First, the methods and procedures employed by members of a profession are based on research and a body of theoretical knowledge. Second, members of a profession have an overriding commitment to the well being of their clients. Third, to ensure that they can always act in the interests of their clients, a professional community reserves the right to make relatively autonomous judgements free from external, non-professional controls and constraints (Singh, 1992, p273).

It is to consideration of the basis on which we make our professional judgments that the Tarot takes us next.243

Card 3: The distant past, the foundation or root of the subject matter of the question.

This is an important card, and those of you more familiar with psychology than Tarot may see the strategy implicit in asking us to speak and interpret our history in this way. Here, when we remember the question we are investigating as literacy educators, we are asked by the Tarot to remember our history, and call it into being as we think about our present and our possible futures.

Indeed, as Singh (1992, p273) notes: “There is a need for teachers to recover and reconstruct knowledge that allows them to more fully understand their own histories in order to be able to interrogate and analyse views of their professionalism”. He goes on:

If there is to be any chance for teachers to make changes which improve literacy education, it is important for them to have an understanding of the conflicts surrounding the genesis and evolution of ideas, practices and organisational modes presently taken for granted (Singh, 1992, p274).

Fifteen years ago, Viv Nicoll-Hatton wrote a PEN for PETA that focussed on the work of Don Holdaway, an international (New Zealand) literacy scholar, whose 1979 book The Foundations of Literacy highlighted the centrality of oral language for literacy learning in young children, and introduced the formal concept of ‘shared book experience’ into the practice repertoires of early literacy teachers. Nicoll-Hatton noted there something that I still find very telling in terms of teachers’ awareness of our professional history: “Many teachers who successfully use the shared book approach in their classrooms may never have had cause to read Holdaway’s The Foundations of Literacy, since his ideas have been incorporated into most state curriculum documents, teacher education courses, and inservice courses …” (Nicoll-Hatton, 1992, p1). And for this reason, as she continued, many teachers:

(for instance those who learned of the procedure ‘second-hand’ through teaching manuals) are not aware of the thinking and research that lie behind what appears to be a very simple classroom routine (Nicoll-Hatton, 1992, p1).

244Later in this interview, Holdaway explained the rationale for the use of big books in the classroom, and in these reasons we find the traces of many of the challenges to formal, structured pedagogical approaches to literacy learning, the ‘synthetic phonics’ that Jackie Marsh referred to yesterday, that have continued ever since. Holdaway said:

For one thing, we wanted a style of teaching which allowed all children to enjoy and cope with a challenging, ungraded, open literature at the centre of their instruction, [with] repetition producing ‘favourite texts’ suggested by the emergent literacy research.

For another, we wanted print itself to be the focus of attention, and for this attention to be universal and under the control of the teacher. We wanted to teach phonics in context.

We wanted a situation which was cooperative and supportive rather than competitive and corrective.

We wanted to build a culture of trust and desire for written texts, a ‘literacy club’ from which no child was excluded.

We wanted to use a literature so powerful that it would generate writing and every other form of real literate activity, including genuine publishing and book-making.

We wanted every child to have an extensive inventory of text so familiar and loved that it would be a lifetime resource for all manner of literate preoccupations (Holdaway in Nicoll- Hatton, 1992, p2–3).

Now, while Holdaway’s work is not actually the distant past for me, it is for my students – many of whom, perhaps like many of you, would never have read or would never make connections between the work of Holdaway, the work of James Gee in the United States, and that of leaders like Brian Cambourne, who worked with the idea of literacy acquisition in the Australian context. It may surprise you to know, too, that for many of the young teachers graduating and entering schools today, the really important and relatively recent writing of Alan Luke and Peter Freebody is similarly ‘distant’, and their notion of ‘the Four Roles of the Reader’ has become orthodox knowledge – and the principles behind it taken for granted – so that, unless we make use of heuristics 245like this to remind ourselves of them, they are rendered less important and less powerful as teaching methodologies.

I used this concern in a recent chapter for Robyn Ewing’s new book the Beyond the Reading Wars (2006) where I described a particular reading method that was developed, quite brilliantly, by a creative teacher, George Jones, after his appointment to a little one-teacher school at ‘Bundarra on the Gwydir’ in north west NSW. Mr Jones quickly worked out that there was a huge range of literacy experience and capacity among the children in his classroom, and that he could not make best instructional use of the time they had in school if all the instruction needed to come through him. He worked out a system of phonics that would allow the children to remember the sounds that correspond to the symbols of print, and therefore to be able to self-correct using a form of kinaesthetic mnemonic (‘auto feedback’) as their body automatically moved to the position they had learned in correspondence with the sound.

As Holdaway (in Nicoll-Hatton, 1992) reminds us, the concept of learner self-correction is a key aspect of Marie Clay’s historic contribution to our professional knowledge as literacy teachers. Her approach moves from the assumption that learning happens when we make mistakes, and then use our tentative strategies and insecure knowledge to take a risk and self correct – thus confirming and strengthening our knowledge of how print (and other semiotic forms) work.

The ‘Jones method’ for teaching reading, while employed successfully for over 20 years in Bundarra, and while it enjoyed nearly 10 years additional success in the classrooms of NSW teachers who were ‘inserviced’ by Jones, started to lose its potency once he wrote and sold the manual, and it was placed on the reading list for teachers training colleges in NSW and Victoria – and once the teachers who took it up lost touch with the ‘theory’ and meaning – the situated professional knowledge, on which it was based.

Remembering our pasts, then, is crucial for successful change in literacy education. But we always teach in a closer relation to yesterday than last 246week, last year, or last century – and so it is no surprise that the Tarot asks us to think about this too. It is difficult work, and as Davies et al. (2007, p31) write, about their work with a group of teachers who were not interested in reading the material the researchers provided for them. They rejected accounts of an historical reality because, it seemed, “[t]here was […] no way of understanding discourse at work, except through what was happening now”. To understand this phenomenon, they have drawn on the idea of “[t]he neoliberal drive for what is new, as it is only the ‘new’ that can take us into the future” (Davies et al., 2007, p31). The Tarot reading considers this point as well.

Card 4: More recent past, including events taking place, not necessarily directly connected to the question.

Here we consider the constraints and circumstances that have had recent impact on our work – the policies and syllabi that are in place in our schools and systems; the political influences that require us to behave in certain ways: the rules or mores of our particular school or institution – timetables, staffing arrangements, and so on. We need to be clear about these issues – we have to stand somewhere in the present – we cannot pretend that the public media arguments and disputes over literacy and the best way to teach literacy are not our business. They are.

I used Denny Taylor’s (1998) argument above to talk about the problems many teachers find with synthetic literacy programs and large number of required learning outcomes that are focussed on content delivery rather than the circumstances of delivery and the reception they may get. Even when teachers appreciate the regularity, security and safety of these scientifically-proven programs, they often report that the programs ‘get in the way’ of them knowing the children they are paid to teach.

In this regard, Taylor argues that when teachers are caught up in the rhetoric of the need to rely only on scientific ‘evidence-based’ research to guide their practice, the relationship between teachers and children is changed, so that the teacher’s practice is no longer driven by the children in her classroom.247

Developing phonemic awareness in reading and writing classrooms in which teachers and children form literate communities has different social, cultural and intellectual significance than developing phonemic awareness in classrooms in which instruction takes the form of predetermined lesson plans that are given to children and used to control their learning (Taylor, 1998, p226).

But there are other influences that impact on our decisions as literacy teachers – as the discussion question posed at this stage of the Tarot Reading suggests, these do not necessarily have to be explicitly connected to the question. Here again, chance plays a hand. You might have just read a wonderful new book short-listed for the Children’s Book Awards for instance; I am currently engrossed in an old, dog-eared copy Sylvia Ashton Warner’s (1958) novel Spinster; a young teacher, Jemma Gascoyne, with whom I have worked on the River Literacies Project over the last couple of years (Comber, Nixon, Reid, 2007) found that her ability to remain committed to environmental action in her practice was assured when she discovered that her new colleague in the room next door was just as passionate about environmental issues as she was. These events will influence what we do, what direction we will take, and how we feel about what we are doing as teachers of literacy. They temper, sometimes, the ambitions that we may have – but at other times they extend and enrich them far beyond what we might originally have envisaged.

Card 5: The best that can be achieved. This is directly related to the question.

Here we are asked again to think about how fair, just and equitable access to literacy for all children can be achieved and what it will look like for the classrooms in which we work. In other words, and in the way that Boomer (1982) and Metcalfe and Game (2006) talk about the importance of ‘imagining’ what an action goal will look and feel like in its realisation, our planning is creative – it is a story we tell ourselves about what we and the other people who are implicated in our question will be doing, saying, producing and learning.248

In a Tarot reading, of course there is an exciting element of beating chance, of risk, that knowing a potential future will give us an inside running as we make our way along the pathway towards a solution to the question we have put to ourselves (or to the cards). In a classroom there is just this same element of risk. The element of chance is always with us, and even when we plan something to the last detail there is always a large chance that something will ‘happen’ (an interesting word, by the way – which is related to ‘happy’, ‘mishap’ and ‘happenstance’, through the root word ‘hap’ which means ‘chance’, or ‘good fortune’ [Onions, 1966, p427]).

Sylvia Ashton Warner worked for years to achieve her educational dreams for the ‘little ones’ she taught in her New Zealand bush school. More than any other educational literature I have read, her account of her practice illustrates the importance of resilience and ‘not giving up’ until the best that can be achieved is achieved – even if not permanently. And in Teacher, Ashton-Warner (1963) shows poignantly how fleeting even the most hard-fought success can be. When she returns to the school where her methods were developed and honed over time, and where her ‘little ones’ grew up with a faith in education instilled through their earliest contact with the school system, she sees the way that her success has been cheapened and ‘made safe’ as it was adapted as orthodoxy in the school system. Her response, with those “sparkling five-year-old tears on an autumnal face” (Ashton-Warner, 1963, p224) – surely the most moving closing image of any body’s book – is one that is shared by many who see their thinking mistaken, their work only half understood, and their achievements diminished.

Card 6: The Immediate Future. This indicates events in the next few days or week(s). This reading does not cover months.

At this point the Tarot provides an opportunity to interpret our sense of what could happen – remembering that we are not asked to consider this over the long term, but rather to think around and through the events we want to initiate in the next few days or weeks. This is the crunch of what we normally do as ‘programming’ – often without consideration of all the other factors that surround, underpin, and sometimes constrain our plans.249

As teachers we are among the few professionals who see the mapping out of their immediate future as a key part (a required duty) of their practice. Garth Boomer, a key figure in the history of Australian curriculum studies, internationally known for his work on Negotiating the Curriculum (Boomer, 1982) argues there against an instrumental view of programming – and planning – that is not rooted strongly in the ongoing flow of classroom interactions, relationships and real events in the lives of children. In that book, Boomer outlines what he saw as a planning model that challenged me as a younger teacher to think differently about programming, simply because what he called “Justification of content” is included as a key concern for every program:

This is where we justify the content chosen and make hypotheses about what things may be learnt.

Aim – To decide what they already know and then to introduce new perspectives.

Key question – This is where we outline the key questions that we think will be addressed. They may not be specifically ‘treated’ by the children, but they will be beneath all that is done.

Note – The quality of the question will affect the quality of learning. The key question offers the teacher a philosophical framework which will give purpose, direction and shape to the learning activities. It will almost certainly imply a value stance (Boomer, 1982, p156–157).

For me, this requirement of us as teachers is a deeply professional requirement – to justify the things that go on in the time and space that we control. It is the only link I have found in the literature of school programming and planning in Australia, to the European notion of ‘pedagogiek’, which basically means ‘upbringing’, and which implies that all the work done by all the adults who interact in and on the life of a child, are implicated in a values-based project of induction and introduction of a new member of the social group. It requires us to make our values explicit, and if those values are actually centered around social justice, then they need to be foregrounded in our practice – and if they are centered around neoliberal individualism, then we need to be 250explicit about that too. For Boomer, there is no quality where we do not know what we are doing and why.

Card 7: The factors or inner feelings affecting the situation.

Here’s something quite disconcerting for the non-mystic planner: the request to lay out for in(tro)spection our personal feelings as teachers about our working situation. The Principal’s commitment to improving the BST scores among boys in the school, for instance, and your resentment that the ‘boys’ who are in focus here actually seem only to be some of them; my lifetime fear of singing out of tune in public (which began in the Year 4 Choir at South Girls and Infants State School, Toowoomba), which always seems to limit some of my larger creative plans; or the whole school’s concern with addressing a growing problem with bullying, that needs to be dealt with on a number of levels.

Most of the time, as Sylvia Ashton-Warner (1958) says in the opening pages of her novel Spinster, “The thing about teaching is that while you are doing it no yesterday has a chance” (1958, p8). Once we are caught up in the passion and pleasure of the act and art of teaching little children, we often forget that we can’t sing, or that the child who is reading the words and reading ahead as we all sing along together is the same child who failed again to sound out his reading correctly yesterday, as his fear of ridicule and teasing overcame all other feelings in that event. Paying attention to these inner feelings (both our own and those of our students) in this simple way is worthwhile in that while the Tarot asks us simply to note them, in so doing we acknowledge and respect them – and do not overlook or ignore them.

In reflecting on her work as a researcher of children at work in her classroom, Vivian Gussin Paley also bears strong witness to the importance of this sort of acknowledgement:

The act of teaching became a daily search for the child’s point of view accompanied by the sometimes unwelcome disclosure of my hidden attitudes. The search was what mattered – only later did someone tell me it was research – and it provided an open-ended script from which to observe, interpret, and integrate the living drama of the classroom.251

I began using the tape recorder to try to figure out why the children were lively and imaginative in certain discussions, yet fidgety and distracted in others […] wanting to return quickly to their interrupted play. As I transcribed the daily tapes, several phenomena emerged. Whenever the discussion touched on fantasy, fairness, or friendship (“the three Fs”, I began to call them), participation zoomed upward (Gussin Paley, 2007, p154).

This work points us clearly (back) to the need to concern ourselves with children’s lives outside of the classroom, argued by Ashton-Warner (1963) as a way to ensure that literacy is both meaningful and relevant in those lives.

Card 8: External influences. People, energies or events which will affect the outcome of the question and are beyond the Querent’s control.

Here we are able to consider those things that will thwart or even possibly support us in our imagined changes – the time of the year and the school calendar come to mind immediately as factors that will impact on what it is that we plan and start to do. There may be other influences that emerge from the action as it unfolds, such as information about the skills or interests of a parent or grandparent, a travelling exhibition or a major news event. Some of these are things we cannot always work with if unpredictable, but by asking us to consider them in the planning process, the Tarot asks us to be open to opportunity and hence flexible – this is the meaning of this stage of the reading.

Card 9: Hopes or fears around the situation.

There are always great hopes for any statement of goal or quest. What would be the best that can befall us if we set out on a pathway to improve all children’s literacy experiences in our classrooms? That they will all love me for having helped them earn the gift of reading? That their parents will write to the Principal about the wonderful things happening in my classroom? That I will catch Kane Edwards reading in the book corner instead of spitting into the giraffe’s ears? That they will all achieve brilliant results on the tests and they will make a movie about them, starring Naomi Watts as me?252

The instructions that are provided in the Tarot manual note here that we should “always bear in mind that hopes and fears are closely intertwined, therefore that which we hope for may also be that which we fear, and so may fail to happen” (Angel Paths Tarot). Indeed, as Cormack (2006, p130) says: “if history is any guide, we will experience a long period of experiment and change, with the old existing alongside the new, as teachers respond to the impact of changes in the materials they work with.”

Card 10: Final outcome. This is a fairly self explanatory card.

We should remember the stoic advice of Antonio Gramsci to aim for what he described as an “optimism of the intellect, pessimism of the will”, in relation to the final outcome of our planning and teaching for literacy – remembering, just as with the Tarot, the classroom plan is always subject to chance.

As Sylvia Ashton-Warner (1958) says: “The days happen along in their inadvertent way …”

I plan, but this is the surest way not to do a thing. Some other deeper mysterious plan takes over. I look for it sometimes, thinking I might submit my own will to it, thinking it would prove easier, if only I could put my finger on it beforehand. But I never can. […]

Yet I still plan in my wan way. I find some element of security in seeing ahead of me in a definite arrangement. It’s a framework that amounts to a spacious shelter, and even though little eventuated that I have thought out first, I still do it. And as fast as my deliberations come to no fruition I make them again … (Ashton-Warner, 1958, p31).

The Tarot provides its own advice here too: However it is worth saying that if the card comes up somewhat ambiguous, once again it may be worth drawing three extra cards to clarify.253

Conclusion

In summary then, I have used the structure of one means of telling the future, the Tarot, to lay out a reading of our pasts, or some of them, and the sorts of considerations that I believe all of us need to reflect on, as teachers, as we plan the learning pathways for our own future directions in literacy teaching. A couple of years ago now, Bill Green (2003) asked a similar sort of Janus question in relation to English teaching – and as Jackie Marsh very usefully reminded us yesterday, our English teaching colleagues are in a very similar state of flux about the status of their subject:

Where are we now? Where have we come from? Where are we going? These are questions arguably fundamental to English teaching, as a distinctive curriculum practice and a longstanding feature of schooling. They might seem removed from the immediate hurly-burly of English teachers’ work […] But such considerations are relevant and vital nonetheless, I suggest, and indeed central if we are truly to understand what English teachers do and what they are … (Green, 2003, p135).

With eyes in the back of our heads, then, let us hope that we can move forwards into the future, treading strongly in our shared professional knowledge, and able to face the future knowing that we can support our ‘little ones’ to make mistakes, to learn from their errors, and to be supported in their efforts to communicate, enjoy and learn from the literate practices in which we allow them all to be fully engaged.

References

Angel Paths Tarot (retrieved 1 September 2007) Tarot Spread, www.angelpaths.com/spreads3.html.

Ashton-Warner S (1958). Spinster. London and Auckland: Heinemann.

Ashton-Warner S (1963). Teacher. London: Virago.254

Boomer G (1982). Curriculum composing and Evaluating. In G Boomer [Ed], Negotiating the Curriculum, (pp150–163). Sydney: Ashton Scholastic.

Comber B, Nixon H, Reid J (Eds) (2007). Literacies in place: Teaching environmental communication. Newtown: Primary English Teaching Association.

Cormack P (2006). Reading in the primary English curriculum: An historical account. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 29(2): 115–131.

Davies B, Edwards J, Gannon S, Laws K (2007). Neo-liberal subjectivities and the limits of social change in University-Community Partnerships. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 35(1): 27–40.

Ewing R (2006). Beyond the Reading Wars: A balanced approach to helping children learn to read. Newtown: PETA.

Green B (2003). (Un)changing English: Past, present future?. In B Doecke, D Homer & H Nixon [Eds], English teachers at work: Narratives. counter narratives and arguments, (pp135–148). Kent Town, SA: Wakefield Press & AATE.

Green B, Reid J (2002). Constructing the teacher and schooling the nation. History of Education Review, 31(2): 30–44.

Gussin Paley V (2007). On listening to what the children say. Harvard Educational Review, 77(2): 152–163.

Metcalfe A, Game A (2006). Teachers who change lives. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Nicoll-Hatton V (1992). Big books revisited: An interview with Don Holdaway, PEN 86. Newtown: Primary English Teaching Association of NSW

Onions C T [Ed, with G W S Friedrichsen & R W Burchfield] (1966). The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Patty A (2007). Every picture tells a story: So put those spelling books away. Sydney Morning Herald, 1 September 2007, p11.255

Reid J (2006). Reading stories: Understanding our professional history as teachers. In R Ewing [Ed] Beyond the Reading Wars: A balanced approach to helping children learn to read, (pp16–25). Newtown: PETA.

Reid J, Green B (2003). A new teacher for a new nation? Teacher education, national identity and English in Australia (1901–1938). Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Conference, Edinburgh.

Reid J, Owens K (2005) The bidialectal approach to teaching standard Australian English, evaluation report prepared for Aboriginal Programs Branch, Sydney: NSW Department of Education and Training.

Singh M G (1992). The literacy teacher as a professional: Insights from the work of Sylvia Ashton-Warner. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 15(4): 273–286.

Taylor D (1998). Beginning to read and the Spin Doctors of Science: An excerpt. Language Arts, 76(3): 217–231.