1

Reading places: creative and critical literacies for now and the future

Barbara Comber

School of Education

Hawke Research Institute for Sustainable Societies

University of South Australia

Introduction

This paper explores the productive literacy learning possibilities inherent in young people reading and writing about the environment. It draws on two projects where young people have had opportunities to develop new knowledge about their local places and to become involved in communication about the care of, and the improvement of, those places. Urban renewal from the inside out involved primary school children working with architects to redesign and remake an area of the school grounds into the Grove Gardens. River literacies involved teachers and young people from schools around the Murray-Darling Basin studying and representing their local environment in various media. Developing future directions in literacy education, the theme of this collection of papers, is contingent upon us on learning from our pasts, getting beyond professional bandwagons (which have characterised literacy education) and exploring the affordance of various media.

If we are to educate for the present and the future, today’s young people need access to the rich cultural resources of their varied histories, the best in the contemporary cultural landscape, and dispositions towards inventing and appropriating new ways with words and images. The kinds of communicative resources young people need to develop for the future should include traditional literacies and new emergent forms of literate practices. It is not about either/or. Indeed as Dyson (1989, 1993) showed many years ago now, if and when the curriculum is permeable, children are able to skilfully appropriate and work with the resources of school, peer and home worlds in order to make meaning and represent 6their thinking. The table below (Table 1.1) displays just a few of the literate practices in which young people and their teachers were engaged during the projects which I go on to describe. The point I wish to make here is quite simply that teachers work cumulatively with a range of genres and repertoires of practices which suit the particular purposes of the learning for which they are aiming. With reference to bringing placebased pedagogies and critical literacy together I will discuss several instances of how and why it makes sense for teachers to work across a continuum of literate practices developed in different eras.

| Traditional school literacies | Emergent school literacies |

| literature | radio broadcasts and talk-back |

| diaries | web-pages |

| surveys | computer aided design |

| formal speeches | community announcements |

| cards and letters | film production |

| alphabet books | spatial literacies |

| anthologies | installations |

| debates |

Table 1.1: Traditional and emergent school literacies

A number of writers have indicated important differences between in-school and out-of-school literacies (Hull & Schultz, 2001; Pahl & Rowsell, 2005), the pervasive tendency for policy to demand limited forms of literate practices (Luke & Luke, 2001; Marsh, 2007), the need for teachers to allow young people to articulate their out-of-school literate practices and pedagogies with those of the school (Moje, 2000), and increasingly, scholars write of new literacies (Lankshear & Knobel, 2006, 2007; Marsh, 2007). Contrasting in- and out-of-school literate practices has been useful in highlighting what is missing from a typical authorised school literacy curriculum. Pahl and Rowsell (2005, p6) ask “Why does identity breathe life into literacy?” Indeed the rationale for articulating out-of-school literate practices more closely with those of schooling recognises that literate practices involve identity work and that for some young people the literacies of schooling may be alienating or undesirable. Whilst Hull and Schultz (2001, p577) contrast what goes on 7in school with young people’s out-of-school literate practices, they also point out that “contexts are not sealed tight or boarded off … one should expect to find … movement from one context to another”. The school as an institutional context does not necessarily determine that classroom literacy practices will be inauthentic or purposeless or indeed new or old. I do not wish to contest the notion of new literacies, per se; indeed there is considerable evidence of the material differences between emergent digital literacies and traditional print literacies (see Merchant, 2007 for a useful review).

School literacies cannot be taken for granted. As our longitudinal case studies indicate there is considerable variation from classroom to classroom, school to school and even between children in the same classroom (Comber, Badger, Barnett, Nixon & Pitt, 2002). Young people’s portfolios of products and performances will vary hugely by the end of a school year, not to mention the end of a school career. Our studies suggest that young people are acquiring very different repertoires of practices and they also show that what teachers do matters greatly. School literacy practices are not the same everywhere. Indeed we can ask what might happen if in-school literacies were more social, goal-directed, participatory, consequential, communicative and aesthetically satisfying. In the context of this paper, what might happen if young people’s literate endeavours were at least in part designed to connect with, represent and even work towards enhancing local environments? The content of students’ reading and writing is very important in terms of motivation to tackle the challenges of literate work. The content of school literacy tasks needs to respect young people’s intelligence and recognise their potential for understanding and acting in the world as citizens here and now as well as into the future. Place-based pedagogies offer new possibilities for rethinking curriculum and pedagogy in productive ways in these times.

Place-based pedagogies are needed so that the education of citizens might have some direct bearing on the well-being of the social and ecological places people actually inhabit (Gruenewald, 2003 p3).

8We now face major new challenges for a sustainable future – an ailing global environment, escalating wealth/poverty divides, and increasing threats to peace. We need to educate young people to live in a world of our making with all of its complexities and potential. I go on now to illustrate how different teachers are grappling with these challenges and at the same time creating engaging, inclusive classroom cultures and producing high quality student artefacts incorporating both traditional school literacies, though critically inflected, and emergent school literacies. In the projects I discuss below, teachers brought together their knowledge and practices about critical literacy, creative arts, place-based pedagogies, environmental science and multi-media communication in order to design meaningful and motivating curriculum for middle and upper primary children.

Urban renewal: A context and landscape for learning

Whilst educators and educational researchers may understand differences between children in terms of class, race, gender and poverty and occasionally in terms of locality (e.g. Gregory & Williams, 2000; Hicks, 2002) – urban, rural, remote and so on – rarely is the spatial nature of literate practice, nor the relationships between textuality and space made central in research (see Jones, 2006; Leander & Sheehy, 2004). Place and indeed spatial elements of literate practices are often seen as static, contextual backdrops to other identity markers. We have come to be more conscious of place and space as constitutive, and central, as our work is consistently located in high poverty areas, which brings us back to particular places – neighbourhoods, suburbs and regions, and to groups of people who are subject to poverty. One such project was conducted in the western suburbs of Adelaide in an area undergoing urban regeneration. This community is one of the poorest in Australia with an extremely diverse population, including many refugee and immigrant families, who have moved to Australia seeking a better life.

Westwood, the largest urban renewal project in Australia, is a $600 million joint development between the South Australian Housing Trust, Adelaide-based real estate developer Urban Pacific Limited, and the local government City of Port 9Adelaide Enfield that covers an area of six square kilometres and encompasses five suburbs. (Westwood, 2007, see www.westwoodsa.com.au, accessed 6 December 2007)

We had already developed a co-researcher relationship with Marg Wells, a primary teacher and her school principal, Frank Cairns when they were at Ferryden Park Primary School, one of the first inner western suburb precincts to be ‘renewed’. Marg Wells has taught for over 25 years. She has a strong personal and professional commitment to western suburbs, having grown up in the area and living nearby in her adult life. Over an extended period she has assisted young children to develop an analysis of the neighbourhood and other social spaces. We have documented that work elsewhere (Comber, Thomson & Wells, 2001; Comber & Nixon, 2005; Janks & Comber, 2006), here I briefly draw attention to positive identity work done through literacy practices focussing on place, before turning explicitly to the Urban renewal project.

Significantly Wells’ pedagogical repertoire included traditional print-based literacies and classroom pedagogies such as studying and making of a class alphabet book and a picture book, wider community literacies such as conducting and analysing surveys, as well as more contemporary emerging literate practices such as the use of digital photography of the neighbourhood and Kid Pix. The point to note here is that the design of the literacy curriculum and the associated tasks were contingent upon what the teacher was attempting to accomplish – in this instance, understanding and agency with respect to urban renewal. In other words, Wells wanted the children to understand what urban renewal meant and how they might take active roles in contributing to new public and school places, not simply be the passive observers of the development of an improved suburb for other people’s children. In terms of the classroom literacy practices, new literacies were not included for the sake of trendiness, nor traditional literacies as a retreat to the supposed safety of a bygone era. Rather the pedagogical program was based on what might be productive for these young people learning to represent themselves and their places (real and imagined) in a variety of media for different audiences. Importantly, in this curriculum the young people were variously positioned as researchers, analysts, 10designers and producers of texts, each time taking an agentive position with respect to textual practices.

A is for Arndale: Alphabet book revisited

If we consider briefly just one task based on children’s literature we can see the powerful way in which Wells positions her students with respect to place and identity. A consistent feature of her pedagogy is her innovation on the basis of existing published texts in order to produce class-made shared books – a traditional strategy in early childhood literacy classrooms. However, her approach is inflected with her knowledge of critical literacy and place-based pedagogies. In the one case she took a post-colonial approach to the alphabet book genre (Russell, 2000) and in another, she developed a class-made picture book drawing from the work of an architect, Indigenous studies, and author Jeannie Baker (2002), around the concept of belonging places. As a result two child-produced class texts were created, entitled A is for Arndale and Windows which allow children to represent complex and changing relationships between people and places.

Wells began by having her Grade Three/Four class closely study Elaine Russell’s A is for Aunty (2000). This alphabet book works as a counternarrative, in that it tells a different history of Australia and life in the bush from the perspective of a female Aboriginal artist and writer. Without being didactic, Russell cleverly conveys insights about the Stolen Generation into her alphabet book for children. In direct contrast with many alphabet books which were produced in the colonial fashion portraying Aboriginal people in tokenistic and stereotypical poses, Russell narrates and illustrates compelling stories of her childhood places and practices. In reading contrastive versions of alphabet books children can begin to see the ways in which texts enshrine certain times, places and ways of life; to understand the kinds of narrative they tell about the past; and note the different representations of cultural groups they portray.

When Wells’ class started to create their own version of an alphabet book, A is for Arndale, (Arndale being the local shopping mall) based on Russell’s book, to send to children in Atteridgeville, a township settlement in Pretoria South Africa, they had to make decisions as 11writers and artists about how to represent their lives and places. It is in taking up the position of producers (having first analysed a range of texts in the selected genre) that children’s understandings of textual resources become evident. The letters of the alphabet allowed for a range of stories to be told about place and the young people’s experience of that place. The relationships between critical and creative literacies, between deconstructive and productive literacy practices and the affordances of place-based literacies for meaning-making require further study and are beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, it is important to note here that particular textual practices may have distinctive pedagogical affordances.

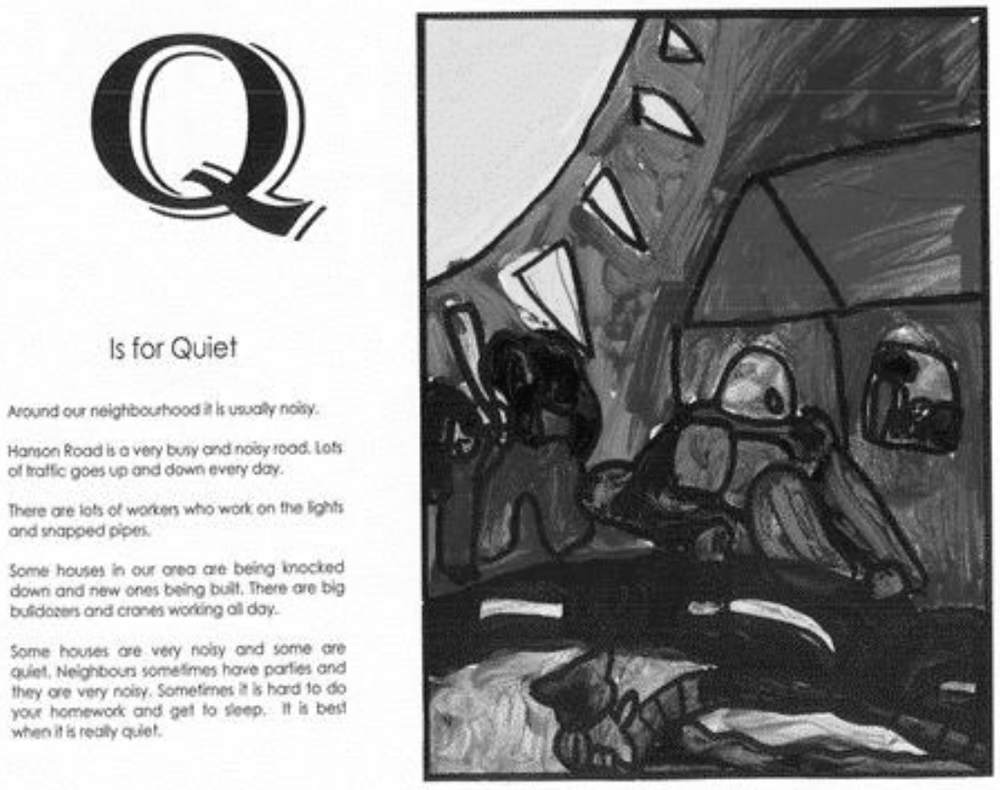

Figure 1.1. Q is for Quiet

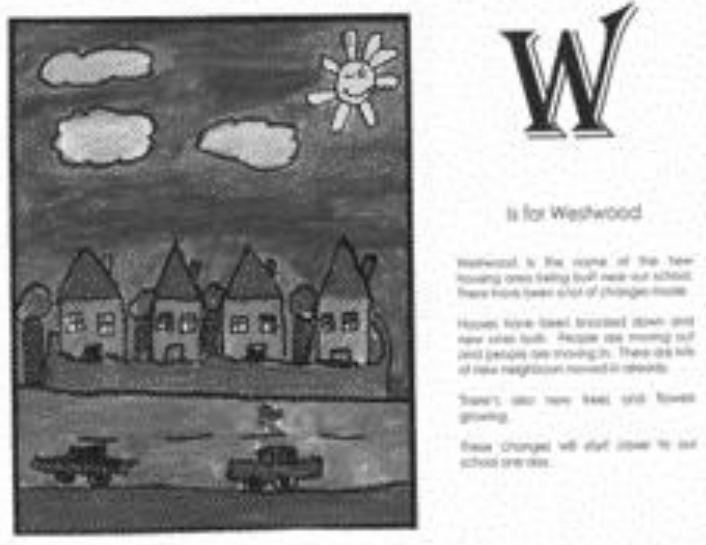

With the help of their teacher concerning overall aesthetics of the design, the young people in this Grade Three/Four classroom produced 12a very high standard of art and writing. The artworks for each letter of the alphabet, inspired by Elaine Russell, were the products of many hours of thought, sketching and careful crafting. The written text entries were revised many times to achieve a high degree of clarity and reader-friendliness for their South African peers. In this instance the reappropriation of the alphabet book allows children to portray their perceptions about place within the landscape of urban renewal. Their entries and illustrations their awareness of their changing places, from the trauma of busy traffic to the order of the neat picket fences surrounding the new houses (see Figs. 1.1 and 1.2).

Figure 1.2. W is for Westwood

Hence in planning literacy curriculum, it is not just a question of whether certain genres are, or are not, suitable for schoolwork, or how they might be modified to engage young people, it is important to think about the pedagogical affordances of introducing children to a range of particular textual practices in order to accomplish particular social and pedagogical goals.

Grove Gardens: Redesigning and remaking places

Having documented Wells’ early innovative curriculum about urban renewal, we developed a project entitled Urban renewal from the inside-out: 13Students and community involvement in re-designing and reconstructing school spaces in a poor neighbourhood1 (which was funded by the Myer Foundation 2004–20052). The project was designed to have primary school children become place-makers and designers, as well as text-makers. The specific brief was to redesign and develop the empty space between the primary school and the preschool. The educational brief was to explore and develop a repertoire of spatial literacies, aiming to:

![]() explore the constructedness of space

explore the constructedness of space

![]() explore the social nature of space

explore the social nature of space

![]() imagine and represent new spaces and their place in relation to them

imagine and represent new spaces and their place in relation to them

![]() explore potential relationships between spatial, imaginary and material worlds

explore potential relationships between spatial, imaginary and material worlds

![]() expand their repertoires of literacy practices

expand their repertoires of literacy practices

The basic idea of the project was to work with architecture students and academics, journalism students and academics, and student teachers and educational researchers to redesign and remake a part of the school grounds, and to closely document that process of change in a variety of media and genres. Together the architect and the collaborating teachers Marg Wells and Ruth Trimboli introduced children to the languages and

14practices of spatial literacies including map-making, architecture and specifically to notions of belonging spaces. Stephen Loo, the architect leading the design aspects of the project, presented a PowerPoint showing unusual buildings and asked questions like:

![]() What kinds of buildings are these?

What kinds of buildings are these?

![]() What might happen in them?

What might happen in them?

![]() Who might use them? How?

Who might use them? How?

Wells’ and Trimboli’s classes (Grades Three/Four and Five/Six) visited the architecture studio and worked with architecture students to learn ways of representing spatial relations in different media, from drawing to model-making. They also visited new public garden areas which had been developed as part of the wider urban renewal project. Below is one child’s response to his visit to the nearby Vietnamese garden.

![]() What design elements did you notice?

What design elements did you notice?

I noticed shelter, water features, seating, grass, platforms.

![]() What did you like about it?

What did you like about it?

I liked the shelter best because it is a design of a hat that people wear in Vietnam.

![]() Did you feel a sense of belonging here?

Did you feel a sense of belonging here?

Yes I did because I felt like I’ve been to Vietnam.

In this short framed reflection we can see the way Wells builds upon the language introduced by the architects, namely design elements, even as she seeks personal response.

Back at the school, Trimboli’s students were involved in range of research activities – such as a PMI (positive, minus, interesting) analysis of their school grounds – not often the kind of task assigned to school children. The children conducted their research, analysed their findings, displayed the results and presented at a school assembly. Involving these young people in research about their school grounds and the surrounding suburb led to the design and exploration of a range of research and spatial literacies that were new to the teachers and their students and which afforded different insights on place and space.15

Wells’ class was invited to think about current dwellings and possible dwellings.

![]() Do you like living in the house you are in?

Do you like living in the house you are in?

![]() What do you like about your house?

What do you like about your house?

![]() What is your favourite place in the house?

What is your favourite place in the house?

![]() What do you like to do there?

What do you like to do there?

![]() Where do you go when you want to be on your own?

Where do you go when you want to be on your own?

![]() Would you like to live in this house? Or a new house?

Would you like to live in this house? Or a new house?

In making the impending urban change the object of classroom study, Wells recognises that children are competent citizens, with complex opinions, hopes and fears, who benefit from discussion. However Wells also encourages a playfulness with respect to re-imagining dwellings. They were invited to choose an interesting building from Stephen Loo’s PowerPoint or from the architecture magazines with which we had flooded the classroom and to imagine life from the perspective of a selected window.

Windows: Becoming place-conscious

Based on Window by Jeannie Baker, Wells developed a class picture book, entitled Windows. In pairs students selected and photocopied a picture of a window (from a magazine or newspaper), taken from the outside looking in. The selection of windows across the class ranged from port-holes to windows in castles, skyscrapers, lighthouses and aeroplanes. Students were asked to imagine themselves inside that window looking out and to write about their imagined space, what they might be doing there and what they could see out of the window. Students also drew the inside of the window and then what they imagined they could see outside the window.

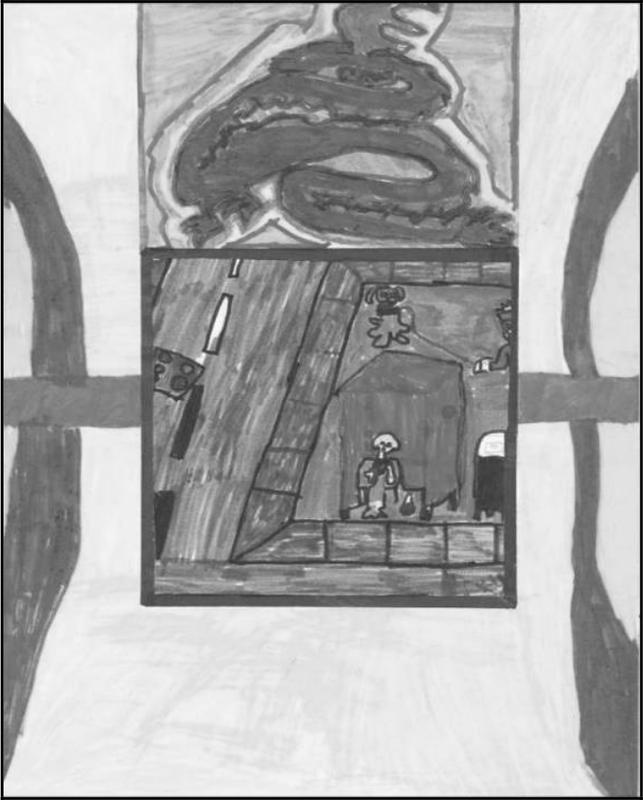

Taking just one example produced by two boys, I note that the writing about the inside space displays a strong sense of ownership (my bed, my bag, my room, my cat), belonging (warmth, sitting by the fire, talking to my dad), social history (toys that I had for my birthday, my photos, awards; dad and his memories) (see Appendix 1 for the written text). It represented how the inside space was configured, their feeling of belonging in it, and how it operated as a social space. Visually they have made the bedroom window a frame. The yellow and red curtaining is 16reminiscent of a coat of arms. A poster immediately above the window depicts a red dragon arranged in a maze-like shape. Through the window in the expanded view we can see a blond-haired woman waiting at a bus stop at a busy intersection (see Figs. 1.3 and 1.4).

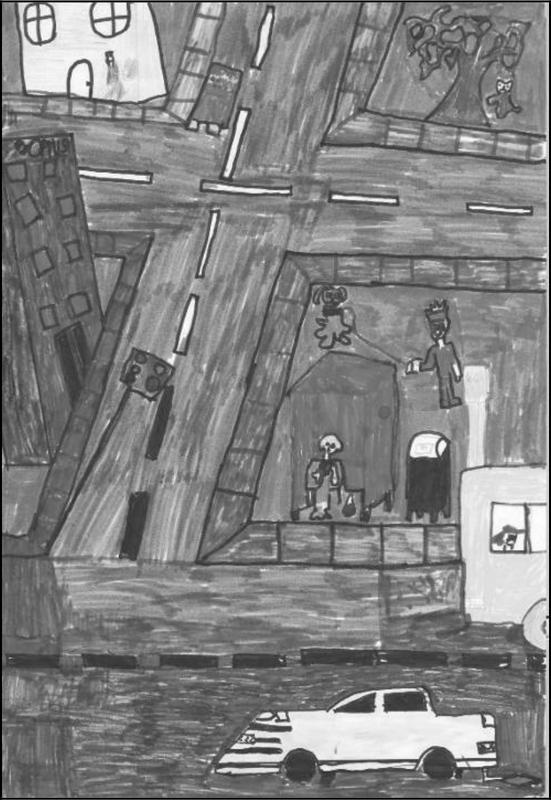

The writing about the outside space displays a strong sense of their ability to imagine possible socio-spatial scenarios (a fancy car, a bus carrying children, mum waiting for the bus); their awareness of the material nature of neighbourhood places (old rubbish bin, new pathway, new traffic light); their capacities for inventing of possible futures and imaginary worlds (potential new neighbours, favourite tree complete with squirrels). Working pairs with the props of the photocopied windows, children were able to draw on their knowledge developed over time to construct complex narratives of people, place and time. These tasks allowed children to imagine figured social worlds (Holland, Lachicotte, Skinner & Cain, 1998) inhabited by themselves and others using a range of semiotic resources – word, image and layout – to represent what it was like to inhabit spaces behind, and outside of, a particular window.

Figure 1.3 Window Frame and View17

Figure 1.4 View through the window

As children wrote and drew about their experiences of their belonging spaces, they called on both material and virtual realities, and like the architecture students they had visited and worked with, they began to present their ideas for the re-imagined Grove Gardens in various media and forms. The teachers put together their collected designs into a laminated book which was circulated around the school and wider community for feedback. A two page text from one pair of Grade Three/Four boys indicates the ways in which students drew on different resources to make a case for their design (see Figs. 1.5 and 1.6).18

| What I would like to see in the area? | ||

| A big maze with some switches | ||

| Why? | ||

| So kids who are waiting can play in it while they are waiting for their mum and dad to pick them up and kids can get tricked because they won’t know which is the beginning and which is the end | ||

| What would it look like? Describe: | ||

| The walls around the maze are made of cement and painted in gold. It will be 10 metres high and it will have traps inside it. You have to find a key to get out and you have to take a friend with you. | ||

| Adrian and Tan | ||

Figure 1.5 Adrian and Tan’s text from Consultation book

Figure 1.6 Adrian and Tan’s image from Consultation book

The boys’ verbal text and their design both indicate the ways they are taking up various insights from the architects in terms of concepts, language and spatial literacies in their repertoires, including walls, height, materials, and surfaces. In addition they indicate their awareness of the social nature of space as they populate the garden and its features with 19children of different ages and waiting parents. Moreover they take up the invitation from Stephen Loo and their teachers to be imaginative as they draw on their experiences with game-playing to imagine the space as a maze with switches.

Thus far, I have tried to show that urban renewal can provide a rich landscape for young people to study their places, and further, that as they investigate and represent their places that this in turn provides meaningful material for literacy curriculum. In addition, I have argued that teachers can and should draw on a range of literate practices in order to engage with the affordances of place-based pedagogies. In this case young people worked across media and genres to explore and portray their understandings of place and space. These necessarily included old (model-making) and new technologies (CAD) and traditional (alphabet books, picture books) and new emergent school literacies (digital photographs, PowerPoint and so on). Young people need inclusive repertoires of literate practices in order to be powerful and productive citizens. I turn now to the second project, River literacies, to illustrate how the environment more broadly conceived can become the object of literacy in primary classrooms.

River literacies: environmental communication in primary schools

In considering the River literacies project I wish to reiterate some of the arguments made for place-based pedagogy through the example the urban school above, but at the same time to show that a wider understanding of place involves an appreciation of the complex relationships between people and places, between humans and nonhuman inhabitants, between land and water. These relationships are ecological, political, cultural, social and geographic and significantly these are captured largely through semiotic resources which in various ways inform policy and practice at local sites. In the past few years Australians have had to learn the hard way what inattention to environment might mean – lack of water, increasing carbon emissions, extinction of many species of flora and fauna, destruction of coral reefs and so on. The impact of climate change is now beginning to hit and it is impacting differently on communities located in different bio-regions and 20economies. We are now beginning to realise that the long dry period we are experiencing is not simply a drought. As Tim Flannery recently argued:

I believe Australians need to stop worrying about ‘the drought’ – which is transient – and start talking about the new climate. (Tim Flannery, Wetter north only temporary. AAP, http://newsninemsn.com.au/article.aspx?id=273233&print=true, accessed 16/06/07)

Some 15 years ago now the Murray-Darling Basin Commission must have had an inkling of where we were headed when it engaged the Primary English Teaching Association to develop a program called Special Forever, where young people attending schools located in the Murray-Darling Basin bio-region were invited to represent their special places in art and writing. As it describes itself, Special Forever aims to:

![]() involve students in becoming critically aware of their environments locally, and across the Murray-Darling Basin;

involve students in becoming critically aware of their environments locally, and across the Murray-Darling Basin;

![]() assist teachers in developing programs that enable students to communicate their understanding of environmental issues effectively; and

assist teachers in developing programs that enable students to communicate their understanding of environmental issues effectively; and

![]() produce and publish a range of student texts focusing on local environmental issues for a range of audiences. (www.peta.edu.au/PETA_projects/Special_Forever/page__1253.aspx, accessed 6/12/2007)

produce and publish a range of student texts focusing on local environmental issues for a range of audiences. (www.peta.edu.au/PETA_projects/Special_Forever/page__1253.aspx, accessed 6/12/2007)

I will not go into the history of Special Forever here (but see Comber, Nixon & Reid, 2007; Green, Cormack & Nixon 2007).

My aim is to provide brief vignettes which show how primary school teachers are working creatively and critically to educate young people about the environment and some of the complex issues they grapple with. I consider two sites from our field trips around the Murray-Darling Basin. I sketch these practices somewhat broadly as details of the practices are outlined in a collection of chapters by the teacher-researchers themselves (see Comber et al., 2007).21

Fighting for survival

When we visited Kingston-on-Murray we realised just how small the school is and how close it is to the Murray River itself (literally a stone’s throw) and the nearby wine producing and eco-tourism centre Banrock Station. The school has been actively involved in the wetlands and bilby habitat rejuvenation programs. The school needs to recruit more students in order to keep its doors open. Its involvement with environmental education may offer one possibility for its survival. In the meantime it is getting a reputation for the way it engages young people in learning about, caring for and communicating about the river. Students produce fliers for city peers who might only visit Banrock for a day; they broadcast on ABC local radio weekly reporting their data on salinity and turbidity in that part of the river; they produce posters voicing their objections to poor treatment of the riverbanks by visiting weekend boaties; they produce photo-stories on local endangered animals; they work at Banrock Station by helping to produce bat-boxes and detecting the tracks of feral animals. These young people are literally learning to read the landscape. As well they get explicit instruction from their teachers about science, from their grandparents about the history of the place, and an appreciation of local crafts from Indigenous elders and artists.

The literacy and communication curriculum here is very much designed around the affordances and complexities of the place. Yet there is no attempt to protect the young people from complex and contested issues – the politics of water rights, the risks and contributions of the tourist industry for the environment and the economy, the fencing off of protected areas of the river – are considered appropriate for these young people to research and discuss. They learn that it is the tourists who are keeping the local deli open with their healthy weekend trading. They learn that whilst they can study the environment at Banrock itself, they cannot access its websites about its sponsorship of research into endangered animals internationally due to its status as a wine producer and exporter. The politics and representation of places is open to discussion.22

Searching for balance

Tongala is famous for Nestlé’s condensed milk and the Golden Cow. Recently the dairy factory operation has been down-sized significantly. A snack bar complete with special milkshakes and souvenirs remains, as well as a small educational centre. It’s one way a rural town keeps itself going in the face of changing conditions. The impact of climate change and the costs of water have already resulted in many services in the town being reduced as the farming community and employment in related industry begin to shrink. Many dairy farmers have already sold up; others are selling their water. Some struggle on. Meanwhile Pam Davis, a Special Forever Coordinator and teacher, long committed to environmental education, tries to help her middle school Grade Five/Six Class to understand what’s going on and how to act ethically. She explains her priorities.

I think one of the main things in our community is for them to see the issue of balance; that because we live in a farming community, in particular, that they have to see that we have to look after the environment and the people, and I think … that’s perhaps a really huge issue. Water of course is a major issue in our community, and again the balance or the sharing of water … during this unit it’s been the balance between humans and the natural world.

Davis wanted young people not only to gather information, but to become advocates for the environment. In an extended project where they researched local endangered animals children became articulate about what they had learned:

That we need to save these animals because like when you think about it, there is 12 in our area, and that’s only Tongala in Victoria … There’s 12 main animals in Tongala, and that’s only Tongala, it’s tiny, so imagine how many there are in Australia, it’s quite sad.

Each student decided on a particular endangered animal for which they wanted to become an advocate. Then Davis and class carried out extensive research using newspapers (local, state and national), websites, children’s literature, informational books and encyclopaedia, local experts, field trips, research at home. Davis built a folio of information to avoid students printing out copious amounts of paper. The overall 23objective was to be able to persuade their peers and members of the local community what needed to be done to save their animal. Her aim was:

to get the children to be advocates for the animals, so more … to go beyond just knowledge [long pause] so we went beyond engagement to, yeah, just what do I need to do to get them to have that real understanding and that real desire to make a difference, and real desire to care…

Davis made time for students to rehearse and get feedback. Their presentations were videotaped so that they could review them and try again. Over the course of the study the students engaged in complex forms of reading, research and communication using a variety of media and genres which Davis judged would help them to develop an understanding of balance at the same time as it would assist them in becoming persuasive advocates whose research might inform others. This meant working with the best models of textual practices that could be accessed about specific content and taking particular points of view into account. Once again a combination of creative and critical, new and traditional literacies was brought together in order to assemble the desired dispositions, knowledge and communication repertoires needed for the task at hand. Inspired by her students’ commitment and capacities to work on such a project Davis went on to successfully bid for the development of an environmental centre in her school.

Conclusion

It is a perennial part of the role of education and educational science to make the world-as-it-has-come-to-be interpretable, understandable, and thus prepare rising generations to address their inheritance of challenges to our present and their future. (Kemmis, 2006, p465)

Across these urban and rural school sites I have show the ways in which teachers are designing new literacy curriculum around an ethics of caring for places. As Kemmis argues above, education does has a critical role in helping young people make meaning of the world, not simply to train them in pre-given basics. As I have discussed place-based curriculum offers some tangible and highly motivating reasons for reading, writing, 24designing, public speaking and communicating more broadly. We need to engage young people in these projects for their immediate and future health and well-being, yet this cannot be taken for granted.

Not only may there be less nature to access, but children’s access of what remains may be increasingly sporadic … Just as they need good nutrition and adequate sleep, children may very well need contact with nature. (Taylor & Kuo, 2006. p124, p136)

In analysing and synthesising what these teachers do we have found the following commonalities in their literacy education practices. Teachers committed to place-based literacy pedagogies:

![]() start with research about subjects that matter to students and their community

start with research about subjects that matter to students and their community

![]() build conceptual and knowledge resources over an extended period of time

build conceptual and knowledge resources over an extended period of time

![]() work in the ‘field’ and document those experiences

work in the ‘field’ and document those experiences

![]() introduce students to a range of genres, media and communication technologies

introduce students to a range of genres, media and communication technologies

![]() ensure time for the production and dissemination of high quality student-produced texts for real or imagined audiences (Comber, Reid & Nixon, 2007).

ensure time for the production and dissemination of high quality student-produced texts for real or imagined audiences (Comber, Reid & Nixon, 2007).

In undertaking this work they draw on all their and their students’ critical and creative resources for tackling complex problems and imagining better futures. More expansive interpretations of literacy in contemporary policy would allow teachers more room to design and enact the kinds of innovative pedagogy that are now needed.25

References

Baker J (2002). Window. London: Walker Books.

Comber B, Nixon H, Ashmore L, Loo S, Cook J (2006). Urban Renewal from the Inside Out: Spatial and Critical Literacies in a Low Socioeconomic School Community. Mind, Culture and Activity, 13(3): 228–246.

Comber B, Nixon H (2005). Children re-read and re-write their neighbourhoods: critical literacies and identity work. In J Evans (Ed), Literacy moves on: Using popular culture, new technologies and critical literacy in the primary classroom (pp127–148). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Comber B, Nixon H, Reid J (Eds) (2007). Literacies in place: Teaching environmental communication. Newtown: Primary English Teaching Association.

Comber B, Thomson P, with Wells M, (2001). Critical literacy finds a ‘place’: Writing and social action in a neighborhood school, Elementary School Journal, 101(4): 451–464

Comber B, Badger L, Barnett J, Nixon H, Pitt J (2002). Literacy after the early years: A longitudinal study, Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 25(2): 9–23

Davis P (2005). Environmental Communication. PEN 147. Sydney: Primary English Teaching Association.

Davis P (2007). From knowledge to action: A pedagogy of hope. In B Comber, H Nixon & J Reid (Eds) Literacies in place: Teaching environmental communication (pp96–110). Newtown: Primary English Teaching Association.

Dyson A (1989). Multiple Worlds of Child Writers: Friends Learning to Write. New York: Teachers College Press.

Dyson A (1993). Social Worlds of Children Learning to Write in an Urban Primary School. New York: Teachers College Press.

Green B, Cormack P, Nixon H (2007). Introduction: Literacy, place, environment. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 30(2): 77–81.26

Gregory E, Williams A (2000). City Literacies: Learning to read across generations and cultures. London & New York: Routledge.

Gruenewald D (2003). The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educational Researcher, 32(4): 3–12.

Hicks D (2002). Reading lives: Working-class children and literacy learning. New York: Teachers College Press.

Holland D, Lachiotte W, Skinner D, Cain C (1998). Identity and agency in cultural and social worlds. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Hull G, Schultz K (2001). Literacy and learning out of school: A review of theory and research. Review of Educational Research, 71(4): 575–611.

Janks H, Comber B (2006). Critical literacy across continents. In K Pahl & J Rowsell (Eds). Travel notes from the New Literacy Studies: Instances of Practice (pp95–117). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Jones S (2006). Girls, social class & literacy: What teachers can do to make a difference. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Kemmis S (2006). Participatory action research and the public sphere. Educational Action Research, 14(4): 459–476.

Lankshear C, Knobel M (2007). Researching New Literacies: Web 2.0 practices and insider perspectives, E-Learning, 4(3): 224–240. http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/elea.2007.4.3.224

Lankshear C, Knobel M (2006). New literacies: Everyday Practices and classroom learning, 2nd Edn. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Leander K, Sheehy M (2004). Spatializing literacy research. New York: Peter Lang.

Luke A, Luke C (2001). Adolescence lost/childhood regained: On early intervention and the emergence of the techno-subject. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 1(1): 91–120.

Marsh J (2007). New literacies and old pedagogies: recontextualizing rules and practices. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11(3): 267–281.27

Merchant G (2007). Writing the future in the digital age. Literacy 41(3): 118–128.

Moje E (2000). “To be part of the story”: The literacy practices of “gangsta” adolescents. Teachers College Record, 102(3): 651–690.

Nixon H (2007). Expanding the semiotic repertoire: Environmental communications in the primary school. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 30(2): 102–117.

Pahl K, Rowsell J (2005). Literacy and education: Understanding the New Literacy Studies in the Classroom. London: Paul Chapman Publishing

Reid J (2007). Literacy and environmental communications: Towards a ‘pedagogy of responsibility’. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 30(2): 118–133.

Russell E (2000). A is for Aunty. Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

Taylor A F, Kuo F E (2006). Is contact with nature important for healthy child development? State of evidence. In C Spencer & M Blades (Eds) Children and their environments (pp124–140). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.28

Appendix 1

My Window

In my room I can see the clothes that my mum bought me, my bag and a closet that I put my clothes in. There is a TV by the fireplace and my cat is sitting by the fire. My bed is done so I don’t have to do it. I can see my poster hanging up on the wall. I am sitting by the fire talking to my dad. He’s telling me about the time when he was young. I can see toys that I had for my birthday and I can also see my drawers. On top of my drawers there is a telephone, my photos, awards and a radio.

Outside my room I can see a fancy car. I can see a bus carrying children. I think they’re going to swimming because they have got their bathers. Outside I can see my mum waiting for the bus. I hope she doesn’t have to wait long out there. I can see a rubbish bin that’s very old. I think the workers are going to break that down and build a new one because that bin has been there since we moved in. I can see they have built a new pathway because the other one was very hard to walk on and it was old. They also put up a new traffic light. This one is very clean but the old one was old and broken. I can see the Optus building. My dad bought his mobile phone from there. My friend is moving to a different house. I hope out new neighbours are very friendly. I see our new neighbours coming to their new house. I hope they have some kids so I can play with them. I can see my favourite autumn tree. I always go and play on that tree with my friends. I can see some squirrels in that tree. I hope they’re not cold over there. Oh, it’s five o’clock. It is time for me to go to maths school. I will see you after maths school.

1 The project was conducted by Barbara Comber, Helen Nixon & Louise Ashmore from the Centre for Studies in Literacy, Policy and Learning Cultures, Stephen Loo, Louis Laybourne School of Architecture and Design and Jackie Cook, School of Information, Communication and New Media, University of South Australia with teachers Marg Wells and Ruth Trimboli and young people from Ridley Grove R-7 School, Woodville Gardens, South Australia. See the Myer Foundation website at www.myerfoundation.org.au/main.asp. It describes its mission in the following way: “The Myer Foundation works to build a fair, just, creative and caring society by supporting initiatives that promote positive change in Australia, and in relation to its regional setting.” The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors only and do not necessarily represent those of the Myer Foundation.

2 River Literacies is the plain language title for ‘Literacy and the environment: A situated study of multi-mediated literacy, sustainability, local knowledges and educational change’, an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage project (No. LP0455537) between academic researchers at the University of South Australia and Charles Sturt University, and The Primary English Teaching Association, as the Industry Partner. Chief Investigators are Barbara Comber, Phil Cormack, Bill Green, Helen Nixon and Jo-Anne Reid.