9

‘Caution Children Crossing Ahead’: Child protection education with pre-service teachers using a strengths approach

Introduction

This paper discusses the early stages and findings of research that explores the use of the Strengths Approach (McCashen, 2005) in child protection education with a cohort of pre-service teachers in Queensland.1 Although widely used in social work, the Strengths Approach is relatively unknown within the education sector although cross sector possibilities with the approach have been identified (Scott & O’Neil, 2003, p. xv). The research arose from the author’s experience working in child protection and education as well as from literature questioning the knowledge and confidence of pre-service teachers working with children at risk, experiencing or recovering from child abuse (Briggs & Potter, 2004, pp. 339–355; Sachs & Mellor, 2005, pp. 125–140; Singh & McWilliam, 2005, pp. 115–134.). The research presented in this paper aims to explore the potential of the application of the Strengths Approach to child protection education.

The paper first briefly explores key terms and findings from the literature review that was conducted as part of the data collection to inform the whole research project on the current context of child protection education and previous research in this area. The next sections examine, in more detail, the literature pertinent to the Strengths Approach and how this was used to develop the Strengths Approach child protection module used for Phase 1 of the research. Strengths principles and the use of The

212Column Approach (McCashen, 2005, p. 48) are explored in these sections. A methodology section follows, explaining the particulars of the research data collection methods (including the literature review method) and shows how the Strengths Approach influenced the way the research was to be conducted as well as being the subject of the research. Finally the early data from Phase 1 is analysed in terms of the potential of the Strengths Approach to child protection education.

Literature Review

Terms and approach

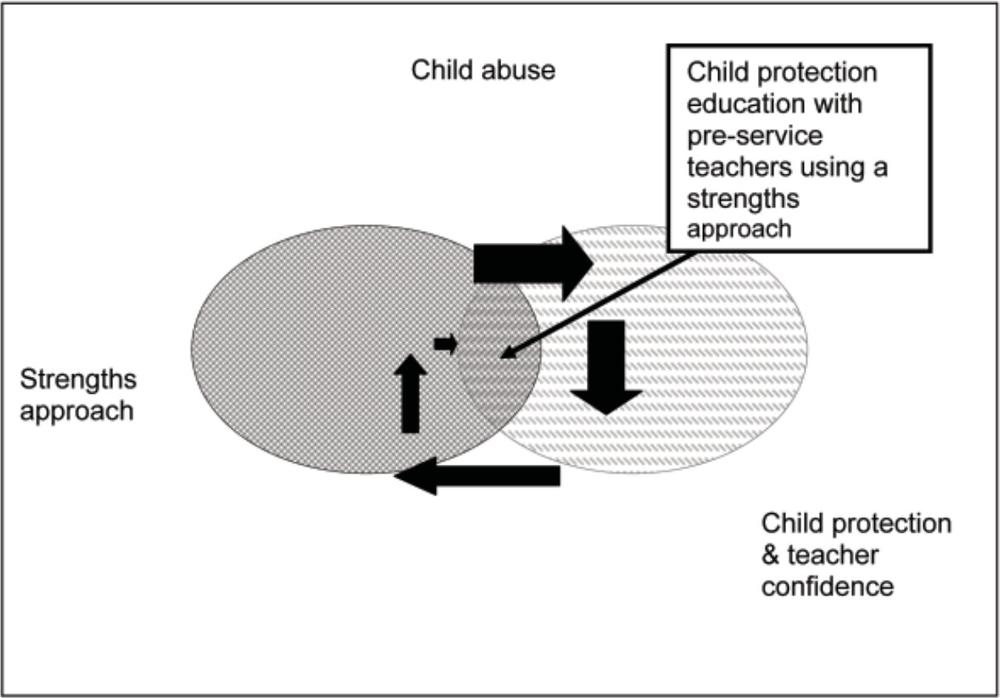

Figure 1 shows the key terms used for the whole research literature review. The decreasing arrow sizes indicate the decreasing amount of literature available in the search circle cateogories. An early finding was that there was a mass of literature recording the instances and associated problems of child abuse, but less literature formally charting or reviewing successful child protection interventions and even less detailing Strengths Approaches (Higgins, Adams, Bromfield, Richardson & Aldana, 2005). There is no current, refereed information that focuses specifically on the junction of all three spheres, which provided the opportunity to explore this unique area as a research project. The Strengths Approach focus of the research has also influenced the development of the literature review process. This involved the researcher positively acknowledging and viewing the literature available as a resource (a strength) for the purpose of assisting change (enhancing child protection education). Although necessarily critical, the review also aimed to funnel all positive implications derived from the literature into the research. The goal of the review was to assist as well as inform the research.

Figure 1. Literature review key search terms

Findings

The significant quantity of data that was available in the area of child abuse confirmed not only the scope and effects of child abuse globally but also in Australia and specifically, for the context of this project, in Queensland (Kalichman, 1999, pp. 20–45; Keatsdale, 2003, pp. ix-4; ISPCAN, 2006, p. 1–5; Landgren, 2004). The United Nations (UN) Secretary-General’s Study on Violence against Children global study highlights that ‘150 million girls and 73 million boys under 18 experienced forced sexual intercourse or 213other forms of sexual violence during 2002’. (Section II. B., pp. 9–10) The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) report from the 2005–2006 financial year indicates there were ‘266,745 child protection notifications in Australia’ (2007, p. 1) during this period and specifically for Queensland ‘notifications numbered 33,612’. (2007, p. 2) Child abuse is recognised as the single most important factor in the success or failure of children to ‘thrive’ (McIntosh & Phillips, 2002, p. 1) and in response child protection reforms have been initiated worldwide (Hopper, 2006, pp. 1–55; Education Queensland, 2004, p. 1). Aimed at improving safety for children they have consequently, however, raised debates regarding the preparation of teachers and prospective teachers for dealing with the impact of child abuse (McWilliam & Jones, 2005, pp. 109–120; Walsh, Schweitzer, Bridgestock & Farrell, 2005, pp. 1–94). Lindsay (1999, p. 3) noted that ‘fear, retribution and even repression’ can be ‘undesirable consequences in a professional community’ of ‘well intentioned legal reform’. Even though initial teacher training programs are expected to prepare 214pre-service teachers for this area of the curriculum (Kesner & Robinson, 2002, pp. 222–231) research by MacBlain (2006, p. 187) confirms that ‘while teachers took their responsibility towards the protection of children in schools seriously, few felt informed and prepared to deal with a child abuse and neglect issue’.

Teachers in Queensland have a number of roles in regard to child protection. They are required to report to their principal any reasonable suspicion of abuse of students by employees or other students at the school (sexual abuse allegations or allegations involving a principal must be made directly in writing to the Executive Director of Education). If teachers suspect abuse outside of the school environment, they are to keep records and report to the principal any concerns. Teachers must obtain a positive suitability notice from the Commission for Children and Young People and immediately notify them of any criminal charge against them and ‘undertake training in student protection procedures’ (Education Queensland, 2006; Queensland Catholic Education Commission, 2006). The type and length of required training is not specified, however service training within schools is regularly offered and varies from online/DVD resources to ‘face to face’ one day workshops run by Education Queensland trainers. Generalised statements are made within Education policy documents as to the role of teachers in ‘providing a safe and supportive learning environment, and preventing and responding to harm or risk of harm for all students’ (Education Queensland, 2006) and ‘working to develop proactive approaches to student protection’ (Queensland Catholic Education Commission, 2006).

Research by Watts and Laskey (1997, pp. 171–176) more than a decade ago found that Australian teacher preparation in child protection was ‘minimal’ and Whiteside (2001, p. 31) more recently found that child protection programs were still ‘spasmodic and selective’. In the United Kingdom, over three quarters of degree programs gave less than 3 hours of child protection training (Baginsky & Macpherson, 2005, p. 318) and the situation is similar in Australia (Laskey, 2004, p. 2). Most degree programs offer a child safety lecture as part of an education subject or separate workshops on the topic (often by an external child protection training provider). McCallum (2001, pp. 1–17; 2002) found that even after such mandatory reporting, training pre-service teachers were still ill-prepared 215to fulfil their teaching responsibilities. Hodgkinson and Baginsky (2000, pp. 269–279) conclude that the lack of time apportioned to the subject of child protection results in teacher preparation being limited to a superficial coverage of the topic. Baginsky’s further research (2003) calls for child protection to be integrated throughout initial teacher training rather than as an adjunct, ‘one off ’ workshop arguing that the approach used in child protection is crucial for affecting the self assurance of prospective teachers. MacIntyre and Carr (2000, pp. 183–199) formally reviewed over thirty (mainly American) programs and while they concluded overwhelmingly that ‘child abuse prevention programmes can lead to significant gains in children’s, parents’ and teachers’ safety knowledge and skills’, the time required to fully explore these programs was beyond the scope of the average workshop timeframe. McCallum (2003, pp. 1–13) received positive participant feedback in a trial using ‘mentored learning’ for child protection. Scenarios featuring children, teachers and families were explored by pre-service teachers with guidance provided by a professional. Baginsky, (2003) surveyed newly qualified teachers in regard to their needs in child protection training and confirmed that ‘case studies which emphasised… good practice’ were viewed as very useful along with general abuse information and reporting mechanisms. In social services, the Strengths Approach (McCashen, 2005) uses a similar ‘one on one’ approach to work with actual child protection cases with the additional emphasis, however, on using the skills of all involved to find solutions. McCashen (2005, p. 186) claims the approach can be successfully applied to a variety of situations in child protection and promotes the time saving and empowering use of the existing strengths of the group (resources, processes and skills) as opposed to the ‘expert’ prescribing new ones be learnt. McCashen promotes, therefore, the ‘value adding’ action of assisting people to build upon methods, processes skills and resources that have been previously successful (perhaps in other contexts). In conjunction with this, however, he acknowledges the need to build upon existing and develop new strengths, but is specific that articulation of foundational strengths is a priority in progressing through the Strengths Approach. Scott and O’Neil (2003, p. xv) have found success in using the approach across a whole child protection organisation and indicate that a Strengths Approach may have a wider application and be valuable for cross sector practice. While 216the adaptation of the Strengths Approach may appear possible for education, a translation of the approach into child protection educational theory or practice is yet to be formally researched or fully explored. This research seeks to explore the potential transfer of the Strengths Approach to child protection education with pre-service teachers.

The Strengths Approach

The Strengths Approach has gained prominence over the last decade in social services. However, the approach is relatively unknown in education perhaps because rather than being a new Child protection program, specific published resource or even a new theory, the Strengths Approach has developed from the social service sector as a new way of addressing issues using existing programs, resources and theory. As a development in individual and organisational practice, it largely emanates from a positive psychology background and refers to the approaches labelled as ‘strength’ or ‘strengths-based’ practice, models or frameworks (Beilharz, 2002, pp. 1–10) now common within the field of social work and therapeutic intervention work. Connected to and influenced by a wide variety of pre-existing social service approaches, strengths approaches are particularly aligned to narrative and family therapy as well as solution focussed and community capacity building approaches (McCashen, 2005, pp. 2–4; Hodges & Clifton, 2006, pp. 361–376).

The Strengths Approach has arisen in reaction to ‘deficit models’ of practice, explains Seligman (1996). Scott and O’Neil (2003, pp. 22–41) highlight the danger of lingering in a deficit mentality that focuses solely on the ‘problems’ of social issues such as domestic violence, drug and child abuse and concentrates attention and efforts on what is wrong with children and families. A deficit approach, they claim, risks disengaging practitioners and families from solution focussed outcomes. Children experiencing child abuse for example are frequently portrayed as victims, sufferers and patronisingly responded to as ‘poor things’ in need of rescuing by experts. This not only places the social worker in a place of power as the rescuer but it also simultaneously disempowers and denigrates the child to being portrayed as a long term victim and sufferer, helpless and hopeless in the public vision (Scott & O’Neil, 2003, pp. 22–41). Within the limited time available for child protection education in degree programs, 217content is often limited to a deficits model where teachers are given the negative facts, figures and symptoms of child abuse and expected to follow the rescuer role. There may be little exploration of the teacher’s role beyond mandatory reporting.

Wayne McCashen (2005) defines the Strengths Approach as an alternative ‘approach to people that is primarily dependent upon positive attitudes about people’s dignity, capacities, rights, uniqueness and commonalities’. (p. v) In the social service setting, the client rather than the social worker is responsible for the process of change (McCashen, 2005, p. 9). This would transcribe into an education context by viewing the child as being able to action change for themselves with the teacher available as a human resource (a Strength in the process) for facilitating this change process as opposed to making the changes for the child. The approach is characterised by social justice principles of ‘power with’ (rather than over), respect and ‘ownership’ (McCashen, 2005, p. 19–29). Critics of the Strengths Approach (Clabaugh, 2005, pp. 166–170; Saleeby, 1992, p. 302) note that in the ‘evangelical’ enthusiasm of the Strengths Based approaches, practitioners should not forget the approach still expects them to be responsible for facilitating the process of change and that this still constitutes a power dynamic that the approach claims to be trying to avoid. Clabaugh claims this can make the Strengths Approach difficult to implement and that it often lacks clear instructions. He concludes, however, ‘Does that mean it isn’t worth a try? No, the obstacles noted above stand in the way of all meaningful improvements. So let’s investigate and learn more about the limits and possibilities of strengths-based education. But we should also remember the importance of doing no harm as we experiment’ (2005, p. 170).

The Strengths Approach explains the principle of ‘power with’ as utilising power for positive progression together on an issue. ‘Power with’ actions and interactions therefore require transparency on the part of the practitioner, self-determination for those experiencing the issue (i.e. abuse) and the sharing of resources, skills and knowledge of all involved to focus on solutions (McCashen, 2005, pp. 31–42). In child protection education using a Strengths Approach, the pre-service teacher then would learn to be able to identify and enable their own and children’s strengths and resources as a way of addressing child protection issues. This may involve sourcing information on the type of abuse involved and appropriate reporting procedures but would dedicate more time to exploring the feelings of the 218children, considering how to build resilience and self-esteem as well as using the approach to collaboratively design practical strategies to prevent or address child protection situations. The sense of fear and lack of knowledge of pre-service teachers regarding child protection (McBlain, 2006, p. 187; Watts & Laskey, 1997, pp. 171–176) may be escalated by the use of a deficits approach (focussing on the statistics of child abuse) and lessened when concentrating on practical child protection strategies studied within an education subject.

Table 1. Capacity Building from a Strengths Approach’*

| Deficit/Pathology (Structuralist) Models | Strengths (Post Structuralist) Models |

| The focus is on problems and causes | The focus is on solutions, possibilities and alternative stories |

| The client is viewed as someone who is damaged or broken by the problem | The client is viewed as someone who is using their strengths and resources to struggle against the problem |

| The worker (professional) is the expert | Both the worker and client bring expertise |

| The process is driven by the worker | The process is driven/directed by the client |

| The goal is to reduce the symptoms or problem | The goal is to increase the client’s sense of empowerment and connection to the people and resources around them |

| The focus is on insight/awareness | The focus is on the ‘first step’ to change |

| The resources for change are primarily available through the worker | The resources for change are the strengths and capacities of the client and their environment |

* © David Lees, 2004, Lighthouse Resources, Brisbane. Qld.

219David Lees (2004, p. 3) presents a useful table (see Table 1) showing the comparison between strengths based and deficits models which also help to more finely describe the Strengths Approach. The Structuralist and Poststructuralist (Barry, 2002) labels are perhaps an unnecessary binary, due to the format, but do serve to date the theoretical emergence of the approach nevertheless. To assist in the translation of the approach to education the substitution of the word ‘child’ for that of ‘client’ and ‘teacher’ for that of ‘worker’ when reading the table is suggested.

With the alternative terms substituted, the potential for using the approach in education starts to become tangible almost immediately. Lees’ table shows the Strengths Approach as a model of practice that is grounded in a specific way of viewing the world and valuing the child as opposed to espousing a specific knowledge base to be taught (2004, p. 3). The Strengths Approach is therefore presented as a standpoint on how to address issues and while recognising that this in itself constitutes a specific knowledge base, the practical application of the approach is wide so that individuals with differing philosophical or political persuasions could adopt it as a practice without conflict. The Strengths Approach builds on a value base and directs to a specific way of working that complements to many philosophical beliefs. The exploration and actualisation of strengths by teachers and children together in order to find solutions to issues is therefore recommended, rather than the exposing of the problem and weaknesses by the expert teacher conducting their own needs analysis. Collaborative recognition of issues and negotiated plans rather than authoritarian determined changes and imposed outcomes are in essence the practical differences between the Strengths and ‘deficits’ or ‘pathological’ approaches (Lees, 2004, p. 3).

McCashen (2005, p. 48) suggests progressing to solutions by the use of ‘The Column Approach’. Five steps are presented in a table format which the worker (or in this case teacher) can fill in as they progress through working on an issue. The steps act as a guide for using the Strengths Approach to an issue. McCashen (2005, p. 91) points out that variations to the names and number of headings are encouraged so that the general principles and process of the approach are clear to all involved and the process personalised. While remaining flexible therefore, the process should still include:

- Outlining the issues (or stories) from the perspectives of all involved, i.e. the child, family, teacher/school and protection agency 220

- Creating a picture of the future or visioning what would be a good outcome to the issue

- Recognising the strengths (skills, resources, personal characteristics) of the people involved in the issues and times when the issue has been resolved or the situation improved

- The availability of other resources to assist

- Planning and designing steps and strategies to reach the solution or goals.

A range of resources will be important to assist with the implementation of The Column Approach. Picture prompt cards, journaling tools, children’s story books and adult reference books are practical tools with flexible ideas for use with adults and children. For example, Bear cards (St. Lukes & Veeken, 1997) and Strengths cards (St. Lukes & Veeken, 1999) may be used to help children identify their own feelings and emotions as well as skills and resources (strengths) through guided interaction with these resources. Children are encouraged to explore pictures of bears with a variety of expressions of pictures depicting strengths such as kindness or curiosity for example. The aim of identifying strengths is to positively raise self-awareness, self esteem and resilience to assist in problem solving, including assertive protective behaviours. The resources, that are user friendly with open ended use, underline the Strengths Approach belief that tools for change should be accessible to all literacy levels and respect and value input from adults and children on issues. Behind the seemingly simplistic resources is the assertion that it is crucial to hear and value the perspectives of children and that child appropriate resources therefore are vital in providing the means to explore, record and use the strengths of the child in addressing child protection issues. More than just a set of stickers and cards, such resources are important prompts that promote engagement with an approach that is inclusive and personalised.

A Strengths Approach Child Protection Education Module

The resources, Column Approach and principles of the Strengths Approach were foundational to the development of the Strengths Approach Child Protection Module for the research. This module is the ‘site’ for 221the research. The child protection education module was designed with findings from the literature review in mind. A thirteen week module was integrated throughout an existing Early Childhood Education subject and taught ‘face to face’ over a semester. The Strengths Approach, as a theoretical framework for teaching and addressing moral and ethical issues such as child abuse, was explained gradually over the course of the module. The Strengths Approach by Wayne McCashen (2005) was used as the recommended text for the subject. The module included exploration and practice using the Column Approach with education based scenarios.

The module included a mixture of whole group formal lecture presentations, small group and individual tutorials and workshop sessions supported with texts, readings, a subject web site and discussion board. Students kept a portfolio of subject materials which included a personal journal entry each week as part of the formal subject requirements. Additional discussion board entries were encouraged (although not compulsory) and were organised into topics of discussion including child protection and the Strengths Approach. Formal presentations firstly outlined child abuse statistics, types of abuse, indicators and signs of abuse, mandatory reporting and policy requirements (a common feature of most adjunct child protection training formats). Smaller group sessions explored the pre-service teachers own perspectives and understandings of child abuse and protection. Child abuse and child protection literature was discussed, real life scenarios were used and presentation content was debriefed. The cohort was encouraged to use the online discussion board or place a journal entry in their subject portfolio regarding their own information, stories and perspectives on the issue of child protection to add to the formal subject materials. Pre-service teachers examined this information as part of the first step of the column approach, that of exploring the issue of child protection.

To assist with visioning and planning for positive outcomes (step two of the Column Approach) students were introduced to the Strengths Approach resources which included journaling tools and The scaling kit (St.Lukes, 2007) that can be used to record progression in an issue or to set goals and aims. In addressing the scenarios presented, pre-service teachers were encouraged to use the Column Approach to start to vision how child protection situations might be different if issues were resolved. The cohort was encouraged to do this verbally in discussion as well in written responses to a set scenario and finally by online discussion once issues had been discussed.

222In week seven of the module the pre-service teachers used the Bear and Strengths cards and stickers (St.Lukes, 1997; 1999) to identify their own strengths verbally and in a poster format. This aligned with column three of the Column Approach (identification of strengths). They discussed their strengths with a partner and subsequently entered a summary of these into the column template when addressing written scenarios. The process was debriefed with emphasis on learning how to use the resources with children to help them to identify their own strengths and to raise self-awareness, self esteem and resilience.

Regulatory information from the Queensland Commission of Children and Young People and Education Queensland (2004) as well as sources of additional child protection, resources and strategies from organisations such as the Abused Child Trust (2003), National Association for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (2005) were presented to the pre-service teachers. Students explored available resources such as story books, computer programs and a variety of personal safety programs being used in schools and were encouraged to share with each other resources they had accessed and found useful. This links directly to the fourth column of The Column Approach (other resources).

A main point of difference with the Strengths Approach Child Protection Module and the more traditional, adjunct workshop was the inclusion of suggested child protection strategies for working with children (column 5 of the Column Approach). Strategies to help raise resilience and self-esteem by the identification and use of teacher and child strengths were introduced. The use of stories, music, art and drama were demonstrated in the module as ways of encouraging children to express emotions and feelings (a child protection strategy to help with the identification of issues). Pre-service teachers listened to a range of stories written for use with children explaining the topic of child abuse and discussed their use in the classroom. Dolls, puppets and picture prompt cards were used in demonstrations to model practice in identifying expressions, role-play situations and examining personal strengths with children.

Methodology

The primary aim of the research was to document and analyse pre-service teacher responses to the implementation of the module outlined above, 223with a focus on the use and potential of the Strengths Approach for child protection education. Additionally, a Strengths Approach research methodology was explored. The research consists of three phases. The phases were designed to gather feedback during the module implementation after a school practicum and approximately twelve months after implementation. Data was collected by recorded, ‘face to face’ individual interviews, focus groups and by the use of an electronic discussion board that allows anonymous postings.

Participants and researcher

The cohort for the research was a small group of nineteen pre-service teachers who agreed to be research participants. All pre-service teachers completing the subject agreed to be participants in the research. All have participated in the Strengths Approach Child Protection Education module within an Early Childhood Education, semester long, subject. The researcher (author) developed and taught the module and also planned and conducted the research. The combined role of the researcher and teacher has particular ethical and methodological implications, particularly as students are being assessed during the subject. As part of the ethical clearance for the research a suitably qualified assessment moderator (separate from the research project) was available to participants. This was to allow a review of student assessment to take place should any participant feel disadvantaged in the subject assessment by participating and commenting (or not) in the research project. The moderator was not used by any participants in the project.

Data collection

The aim of matching research methodology with the research topic was challenging given the absence of a visible Strengths Approach to research (Mackenzie & Knipe, 2006, pp. 1–11). It presented the opportunity, however, to develop and adapt research techniques with a Strengths Approach to data collection and analysis.

An ‘Open View’ rather than ‘interview’ method was developed to collect ‘face to face’ responses from individual participants. A semi-structured interview, using a conversational style, was adapted to increase the opportunity for collaboration between researcher and participants (crucial in a 224Strengths Approach). The ‘Open View’ uses the Strengths resources such as picture and word prompt cards and scaling sheets to initiate and record responses. Participants are included as ‘co-searchers’ and they make decisions as to the method of recording, setting and structure of the ‘Open View’ as well as choosing the Strengths tools they wish to use.

The focus groups lasted approximately thirty minutes with six to eight participants and the researcher as facilitator and were very similar in style to traditional focus groups. As with the ‘Open Views’, however, the groups were also collaboratively organised, (one group chose to meet at a local café, another wished to utilise a tutorial time) and strengths tools were available if needed by the group. One focus group chose to use the scaling sheets, for example, to demonstrate their growing knowledge of the Strengths Approach when it arose in the group discussion. The sessions were introduced as informal conversations (facilitated by the researcher) around the central themes of ‘child abuse’, ‘child protection’, ‘teaching’ and ‘The Strengths Approach’. This contrasts to the more traditional focus group using predetermined and ordered questions set and asked by the researcher. The issues discussed in the focus groups ranged from a group that discussed a case of a local teacher aide dismissed for child pornography allegations and how the teachers had to address the issue with children and parents. Another group debriefed the ‘identifying your own strengths’ session from the child protection module and talked about how this felt and if this could be adapted for use with children.

Data analysis

The Column Approach is used as an interpretive framework allowing the researcher to organise preliminary data and articulate connections in the data to the Strengths Approach. The column headings provide the categories for analysis i.e. responses that explored the issue, responses that visioned solutions, responses that explored strengths, responses that referred to other resources and responses that referred to strategies. The broad column categories guide the collating of data into manageable sections and allow the researcher to draw upon their own strengths (practitioner knowledge, experience and critical reflection and interpretation) in relation to each section when analysing the research participants responses to the electronic discussion board entries, focus groups discussions or 225‘Open Views’. It allows the researcher to chart participants’ engagement with and views of the various stages of the Strengths Approach. The researcher therefore is role modelling the use of The Column Approach as a Strengths Approach practitioner, using it as a tool to address an issue of concern to them personally. In this case The Column Approach is not used to address a child protection issue but rather to find a solution to analysing research data authentically.

Responses are analysed to note the extent that participants used particular sections of The Column Approach. Sub-groupings also emerge within the sections (column headings) in respect to common interests or concerns expressed, i.e. responses to particular resources or responses relating to the same ‘story’. The reasons, implications and significance of the use of particular sections and subgroupings will be explored further in subsequent phases of the research by both the researcher and participants.

The preliminary findings from and discussion of Phase 1 data is the focus of the following section of this paper. Phase 2 will record and analyse discussion board and interview responses from the cohort following a school practicum and will focus on the application of the module into a practical situation. Phase 3 will also gather responses from the cohort a year after the module implementation and aim to record any changes or additions to the earlier data collected after this period of time.

Findings: Pre-Service Teachers’ Engagement in Child Protection Education

The Phase 1 findings and discussion reported here are limited to data collected from the research participants’ electronic discussion board and focus groups. Although all of the participants have chosen to identify themselves in their postings, their quotes and excerpts have been numbered rather than named in this document. Columns 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 refer to The Column Approach (McCashen, 2005, p. 48) as outlined previously.

Exploring the issue (Column 1)

For pre-service teachers who are working, or about to work, in Queensland schools and early childhood settings, the contemplation of encountering children who have experienced child abuse appears to be daunting 226to an extent that it discourages action or engagement with the issue in the classroom. Participants explained in initial discussion board entries (after learning of abuse figures):

I do not feel confident in teaching ‘child protection’. I have taught my own children, probably frightened the daylights out of them, but not sure how I would approach this issue in a classroom. (Participant 1, discussion board)

I don’t really feel comfortable with teaching and addressing child protection. I guess that for a lot of people it would be a very sensitive issue and sometimes easier to just ‘not go there’. (Participant 8)

I don’t know how to handle that situation either. Are we at some stage thoroughly trained and taught how to handle the situation? I think my hair would stand on end having to think of what to say and then do. Where do we as pre-service teachers (and eventually teachers) learn to deal with these matters? (Participant 15)

All participants expressed concerns with the issue of child protection and most also expressed a sense of being ‘overwhelmed’ (Participant 6, focus group) by the child abuse statistics. Baginsky and Macpherson (2005, pp. 317–330) received similar feedback from pre-service teachers before completing various types of ‘traditional’ (non-Strengths based) child protection training. Confidence was shown to have increased after training and again after teaching practice but ‘there was (still) a significant number of respondents expressing some anxiety and confusion, even among those who had indicated that they were confident’ (p. 320). An opportunity exists in this research to add to Baginsky and Macpherson’s work (2005, pp. 317–330) by recording and comparing responses from participants in this project before and after teaching practicum and additionally charting the effects of using a particular type of child protection training (Strengths Approach) and the relationship of this to teacher confidence. Gathering data from the use of a new model of child protection development may add weight to and, importantly, add possible solutions to the hypothesis put forward by McCallum (2002, p.15) that ‘current (traditional) models of teacher professional development … are ineffective in the preparation of teachers to implement the conditions set down by the Rights of the Child’.

227Participants responded to abuse statistics and information (United Nations, 2006, Section II. B., pp. 9–10; AIHW, 2007, pp. 1–2) presented in the module. Responses to informal information from philanthropic, church and charity groups’ publications (The Abused Child Trust, 2003) were more detailed than those in respect to the more formal reports detailing global and national statistics. Participants often made connections between the informal information and their own experiences whereas responses to the larger statistics were limited to comments such as ‘Oh that’s a lot isn’t it?’ (Participant 10, focus group). In particular, pre-service teachers commented on case studies featured on web sites which translated statistics into a more immediate format. Focused information and recommendations specifically related to education were far more successful at engendering interest and a willingness to engage in discussion about child protection. For example, the Abused Child Trust (2003) presents information that ‘a child is abused every fifteen minutes’ and that investigations translate ‘as approximately 1 child in every 2 classrooms’. Participants commented emotively on these figures – Participant 14 for instance turned to another student in a focus group and commented ‘wow and that’s just the investigations too, not everyone gets investigated, just do the maths!’ – which initiated a detailed discussion of the investigation procedure. Initial analysis suggests that the large scale figures of child abuse may be difficult to relate to on a personal level and may be a factor in the disengagement expressed earlier by participants. Workshops limited to only outlining abuse figures and reporting procedures may therefore risk disengaging pre-service teachers from action in child protection. Preliminary analysis also confirms ‘teacher vulnerability’ (McWilliam & Jones, 2005, pp. 109–120) towards child abuse statistics as presented in the child protection module and highlights the need for continued research to examine the critical factors influencing teachers actions (and inaction) in relation to child abuse (Walsh, Schweitzer, Bridgestock & Farrell, 2005, pp. 1–94). Specifically, it appears that, unlike the broader statistics, informal case studies which translate statistics into more immediate timeframes and personalised contexts need to be used in training as they enable engagement with the prevalence of abuse for pre-service teachers on a personal level and connect the figures with the prospective role of a teacher more successfully.

The group discussion prompted some participants to describe on the electronic discussion board their own experiences, perspectives and knowledge 228in relation to child abuse and teaching. There were six responses in this section and considering that the pre-service teachers are yet to complete their final practicum and their formal teaching time is limited, this was a larger than expected number. All the responses reflected a sense of distress at the situations described, wanting (or feeling obliged) to assist but unsure as how to proceed.

A couple of years ago, I had to work one on one with a year two girl. The teacher told me that the girl’s dad had abused her and to watch and listen if she says or does anything different. I must say I felt extremely uncomfortable being alone with that child. I kept thinking ‘oh the poor thing’, and wanted to tell her she would be okay, that there was help for her. But as far as I know no allegation of abuse was substantiated with evidence. I wish the teacher had not put me in that position. (Participant 7, discussion board)

On my last prac however, there were a number of students who suffer from neglect. In particular, many students had come from broken families, terrible living conditions and horrifying home lives. (Participant 12, discussion board)

While I was on one prac the teacher told me that a child in the class had recently stated to her mother that she had been sexually abused by a family member. As I reflect upon the situation, I realise that I tried to deny that this child had been abused. It was not a case of not believing the child, but I just did not know how to react to this child anymore. Also, I did not want to think of the horrible experience and the negative impact it would have, and had already had, on that child’s life. (Participant 7, discussion board)

These unexpected number of experiences mirrored findings by Baginsky and Davies (2000) who also found a ‘small but significant number of them [pre-service teachers] experience direct involvement with a child protection case while on placement in school’. An implication arising from these findings may be that child protection training should be included early in the degree program before major practicum blocks.

These entries as well as the case studies prompted many of the pre-service teachers to explore their own feelings in depth in relation to the case studies 229and to identify and examine personal child protection issues of their own. Some entries, however, were limited (particularly in early weeks of the module) to comments such as feeling ‘uncomfortable’ or ‘fearful’ with examining child protection issues (Participant 8, discussion board). The findings confirmed previous research findings of teachers feeling inadequately prepared to deal with child protection issues (Whiteside, 2001, p. 32) and additionally elaborated that although the feelings were common among the group the reasons for these feelings differed for each individual and depended largely on their experiences of child abuse or protection. The complexity of issues expressed relating to child protection for teachers validated the need to explore child protection over a period of time longer than a one-off workshop. This aligns with work by Laskey (2004, p. 2) that criticises initial training of two hours as ‘manifestly inadequate, considering the complexity and emotional impact of child maltreatment’ and that teachers’ personal needs should be recognised in any child protection training design. The cumulative sharing of individual experiences and listening to others each week allowed the pre-service teachers in this project to more fully explore the issue of child protection (column 1 of The Column approach) rather than limiting discussion to the number of abuse cases. Personal experiences and case study information seem to make it harder for pre-service teachers to ignore the likelihood of encountering children in situations of abuse in their careers or to have thoughts of ignoring the issue as irrelevant for their practice. The project may eventually be able to add weight to the findings of McIntyre and Carr (2000, pp. 183–199) that longer programs are more successful in changing teachers’ behaviour and be able to test claims by Laskey (2004, p. 18) that what is required for child protection education is a ‘program extending over one semester in pre-service teacher education’.

Participants further responded in focus groups to general child protection issues and responses were both personal experiences and responses to cases reported in the media. All participants made at least one comment during the focus group sessions as opposed to only one or two student responses to the large group session examining child abuse statistics (a common feature of adjunct child protection workshops). The three responses below are examples of comments that initiated extended conversations within focus groups.230

One of my male cousins was accused of ‘molesting’ his four year old daughter. (Participant 11, focus group)

He was taken (adopted brother) into the custody of family services and placed for adoption at a few months of age. He was neglected when my parents were asked if they would care for him, however his mother had 12 months to get him back if she showed a change of ways or then my parents could adopt him. Even though I was quite young (2) the day we picked him up, I can still remember the mass of rashes he had, and how sick he was. (Participant 2, focus group)

I read that the boy had a broken arm and nose and had 271 bruises, some quite old. (Participant 9, focus group)

Responses tended to focus on the negative effects of child abuse, particularly in respect to cases reported in the media. Although participants expressed a common sense of despair in respect to cases, this did not seem to be to the extent that Sachs and Mellor (2005, pp. 125–140) describe as ‘child panic and the media’. Nevertheless, the extended participant conversations indicated that Sachs and Mellor are correct when they conclude that in respect to child protection issues and teachers ‘low morale affects teaching practice’ (p. 36), or at least the preparation for it.

Visioning solutions (Column 2)

Some discussion board entries appeared to be operating within column two of The Column Approach where participants describe a goal or start to vision what a good outcome to an issue may be. These entries occurred after the extended discussion of child protection issues, module activities on goal setting and during weeks six and seven of the module.

… (I am) passionate about helping children who have endured such cruel experiences, however, now perhaps (after researching the issue further for my negotiated learning project) I am more concerned and aware of how I will help them. (Participant 2)

As adults, and especially parents and teachers, it is our responsibility to ensure the safety of those children in our care. These children look to the adults in their lives for nurturance, guidance, support, protection and most of all love. (Participant 9)231

I think it is such an important issue that it cannot be ignored and that no matter how uncomfortable and fearful I may be about addressing it in the future (in my classroom), it would be negligent not to. At the same time, I think that it’s important to get all the facts right before jumping to conclusions. (Participant 13)

After extended discussion many pre-service teachers were able to express their hopes for child protection even when some of their initial responses had expressed disengagement with child protection issues. These later responses reflected a personal connection and an acknowledgement by all the participants of their responsibility to protect children despite concerns or negative experiences expressed in earlier responses. The responses add to findings by Webb and Vulliamy (2001, p.73) that despite the difficulties of child protection issues, practising teachers believe it is their responsibility to address these issues as they ‘are concerned about the well-being of the whole child’. From initial findings in this research it seems that pre-service teachers also share this view.

Participants demonstrated extended exploration of child protection issues and practiced goal setting in their entries (column 2 of the Column Approach). They showed the positive psychology attributes of ‘goal directed determination, and pathways, or planning ways to meet goals’ (Hodges & Clifton, 2006, p. 15) which appeared to work well in moving participants beyond exploring the issue of child abuse and into planning solutions. The use of goal setting in this educational setting mirrors success using the strategy in social work settings of The Strengths Approach (Hodges & Clifton, 2006, pp. 361–376; McCashen, 2005; Scott & O’Neil, 2003; Beilharz, 2002). The inclusion of personal goal setting in child protection education training, which appears to be missing in most traditional adjunct workshops, would seem therefore to be an important factor in moving pre-service teachers towards a solution focussed outlook on child protection.

Exploring strengths (Column 3)

While many responses described the negative issue of child abuse, noted by all was the concern for the children and adults associated with abuse incidences. This could be considered as a Strength (column three of The Column Approach) in dealing with the issue of child protection. The acknowledgement 332by pre-service teachers that child protection is an issue they need to be aware of, and their expressed caution with child abuse cases, could also be taken as positive strengths.

More explicitly responses about strengths were also recorded following the module session on identifying and enabling personal strengths. Participant 3 in a discussion board entry notes ‘my strengths are that I am a kind and caring person, I am a good listener, I have a positive outlook on life and always try to find a funny side to lighten the moment’. All students have been able to identify personal strengths in the session although some of the group expressed that this was slightly uncomfortable or that they ‘are not the kind of person who likes to talk about myself a lot so sometimes I find it a little difficult’. (Participant 3) The need to define and clarify the whole Strengths Approach was also a recurring theme in Phase 1 for participants. Comments, early in the module, such as ‘I know you’ve mentioned it a few times, but I’m still not sure exactly what it means’ (Participant 4, focus group) articulated the need to continue to explain and explore the Strengths Approach and its application throughout the later weeks of the module. In addition to understanding generic key definitional terms and the underlying theoretical principles of the Strengths Approach, the Column method may be applied as a particular way of thinking and working through issues. As solutions can vary immensely in the Strengths Approach depending on the issue and people involved as well as the complexity of issues, strengths and perspectives of those involved practitioners must be accounted for in addressing situations. Additionally the range of Strengths Approach resources and strategies must be introduced carefully so that they are used, as intended, as additional tools rather than as constituting the only way to implement the approach in practice (McCashen, 2005). The depth of the Strengths Approach required it to be explained to participants in the project in multiple layers over a period of time. The module progressed from brief definitions of the approach and role modelling the approach to real examples of Strengths Practice, identifying individual strengths and resources before attempting to address scenarios using the Strengths Approach. For the successful implementation of a Strengths Approach to child protection training in the future an extended period of time for teaching and learning would seem necessary and would help to address the criticism that the approach often lacks clear instructions (Clabaugh, 2005, pp. 166–170).333

Resources and strategies (Columns 4 and 5)

Some participant responses outline particular resources and strategies for working with child protection issues in a teaching context including the human resources of children’s families and other teachers.

I believe that it is for this reason that teachers need to know the students in their classrooms and the families that they come from in order to attend to children’s needs. By developing relationships with both families and students, teachers can gain insights into backgrounds of the families to find out what they value and the way the family works. If children’s needs in the home are not being met, the teacher needs to know this to ensure that the students time in school is one that is safe, supportive and protected. (Participant 14, discussion board)

Similar to many responses to the St. Lukes resources (and strategies involved in using them), Participant 5 comments ‘I like the cards and the book (The Strengths Approach) it is easy to understand and I could actually see myself using the cards a lot with kids’.

Some responses explored strategies implicitly whilst expressing child protection concerns.

I understand it is important to watch for signs of abuse and diligently report any concerns. But on the other hand it is important not to spread ‘gossip’ about something that has not been proven. (Participant 7, discussion board)

I had to be careful how I handled situations which involved these students, especially with the manner in which I spoke to them or how they were disciplined. I believe that it will always be a challenge to teach students who have been abused or neglected as each student is different and their circumstances are always different. (Participant 17, discussion board)

These type of responses were often at the end of discussion board ‘conversations’ with other pre-service teachers exploring issues and appeared to take into account other participants responses. The module would seem to allow the pre-service teachers the opportunity and time to explore not only different perspectives on child protection but to also ‘think out’ and adapt their own plans of dealing with child protection issues. Whiteside 334(2001, p. 35) puts forward the need to include training ‘that will help adults deal with disclosures … as well as discussions about mandatory notification’ which has also been confirmed as useful in this project. In addition, however, the findings appear to point out the value of using case studies and scenarios to enhance pre-services exploration of perspectives, strategies and resources with these issues and highlights the call from Laskey (2004, p. 18) that these should be ‘core components’ of child protection training and from Whiteside (2001, p. 36) that ‘training needs to include practical, hands on activities … as well as strategies that will enable them to feel confident in dealing with disclosures’.

Conclusion

The translation of the Strengths Approach from a social service context to child protection education has been the main focus of phase one of this research. A new Strengths Approach child protection module was designed and implemented by the researcher and research participants’ responses were recorded and analysed. Initial findings of the research have included the need to continue to clarify the theoretical underpinnings of the Strengths Approach both in respect to pedagogy and research methodology throughout the subject. The Column Approach (McCashen, 2005, p. 48) was used both in the child protection teaching module and in the analysis of pre-service teacher responses.

Although some participants found the identification of strengths a little uncomfortable and the definitions of the approach needed elaboration throughout the module, participants explored the issue of child protection in depth and responded to child abuse case studies and fellow pre-service teachers’ experiences. Participants were able to set goals for child protection and responded positively to the Strengths resources used in the module, as well as being able to develop strategies for dealing with child protection situations. Initially, the participant responses to child abuse and protection mirrored those found in the literature in this field such as ‘heightened anxiety’ and ‘fear’ (Singh & McWilliam, 2005, pp. 115–134; Watts, 1997; McCallum, 2001, pp. 1–17). After completing more of the module, however, participant responses appear to indicate that the opportunity to vision, explore strengths, resources and strategies in child protection (missing from more traditional, adjunct child protection workshops) 335is valuable for increasing pre-service teacher awareness and confidence in child protection education.

Phases 2 and 3 of the research (following teaching practice) are still to be completed but early findings would indicate that the claim by Hodges and Clifton (2006, pp. 361–376) that using a Strengths-Based framework has potential beyond the social service sector that is just beginning to be realised seems to be correct. The Strengths Approach may indeed be an encouraging new way to increase confidence for teachers especially in fulfilling their child protection role in schools. Encouragingly, the Strengths Approach appears to be helpful, at the very least, to pre-service teachers in the much needed area of child protection education. Participant 19 (discussion board) explains:

I think that the strengths based approach offers a way of thinking about how we react to certain situations and how these situations make us feel … The thing that I like the most about what I have learnt so far is the idea of changing the frame. Through changing the frame, it gives us a whole different way of thinking about who we are and what is possible for us.

References

Australian Government, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2007). Child protection figures. 1–2. Retrieved February 2007, from http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/cws/cpa)1-02/index.html

Baginsky, M. (2003). Newly qualified teachers and child protection. United Kingdom: National Society of the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Baginsky, M., & Macpherson, P. (2005). Training teachers to safeguard children: developing a consistent approach. Child Abuse Review, 14, 317–330.

Barry, P. (2002). Beginning theory: an introduction to literary and cultural theory. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Beilharz, L. (2002). Building community: the shared action experience. Victoria: St. Lukes Innovative Resources.

Briggs, F., & Potter, G. (2004). Singaporean early childhood teachers’ responses to myths about child abuse. Early Child Development and Care,174(4), 339–355. 336

Clabaugh, G. (2005). Strengths based education: Probing its limits. Educational Horizons, 83(3), 166–170.

Education Queensland. (2007). Student protection. Retrieved March, 2008 from http://education.qld.gov.au/strategic/eppr/students/smspr012/

Education Queensland. (2004). Child protection information. Retrieved August 2006 from http://education.qld.gov.au

Higgins, D. J., Adams, R. M., Bromfield, L. M., Richardson, N., & Aldana, M. S. (2005). National audit of Australian child protection research 1995–2004. Canberra: Australian Institute of Family Studies, National Child Protection Clearinghouse.

Hodges, T., & Clifton, D. (2006). Strengths-based development in practice. In A. Linley and S. Joseph. (Eds.) Handbook of positive psychology in practice, (pp. 361–376). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons.

Hodgkinson, K., & Baginsky, M. (2000). Child protection training in school-based initial teacher training: A survey of school-centred initial teacher training courses and their trainees. Educational Studies, 26(3), 269–279.

Hopper, J. (2006). Child abuse statistics, research, and resources. Data File retrieved November 11, 2006 from http://www.jimhopper.com/abstats

International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (ISPCAN). (2006). World perspectives on child abuse: an international resource book. (7th Ed.). Australia: ISPCAN.

Kalichman, S.C. (1999). Mandated reporting of suspected child abuse: Ethics, law, and policy, (2nd Ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Keatsdale, (2003). Report into the cost of child abuse and neglect in Australia. Tugun, Queensland: Keatsdale Pty. Ltd.

Kesner, J. E. & Robinson, M. (2002). Teachers as mandated reporters of child maltreatment: comparison with legal, medical and social services reporters. Children and Schools, 24(4), 222–231.

Landgren, K. (2004). Creating a protective environment for children: a framework for action. UNICEF.

Laskey, L. (2004). Educating teachers in child protection: lessons from research. In AARE 2004 Conference Papers (paper presented at Conference of the Australian Association for Research Education, 2004).

Lees, D. (2004). Capacity building from a Strengths Approach. Inclusion support 337facilitators’ workshop booklet. Brisbane: Lighthouse Resources.

Lindsay, K. (1999). The new children’s protection legislation in New South Wales: implications for educational professionals. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Law and Education, 4(1), 3–22.

McBlain, S. (2006). The curriculum: confronting neglect and abuse. Academic Exchange Quarterly, 10(2), 187–192.

McCallum, F. (2001). Cracks in the concrete: the demise of the teacher’s role in reporting child abuse and neglect. In AARE 2001 Conference Papers (Conference of the Australian Association for Research Education, 2–6 December 2001) compiled by P. L. Jeffrey. (pp. 1–17). Melbourne: AARE.

McCallum, F. (2002). Law, policy, practice: is it working for teachers in child protection? In AARE 2002 Conference Papers compiled by P. L. Jeffrey, Melbourne: AARE.

McCallum, F. (2003). Using mentored learning to support pre-service teachers in child protection. In Educational research, risks and dilemmas. NZARE/AARE Conference 2003 November 29 – December 3, Auckland, New Zealand: New Zealand Association for Research in Education, 1–13.

McCashen, W. (2005). The Strengths Approach. Bendigo: St. Lukes Innovative Resources.

McIntosh, G., & Phillips, J. (2002). Who’s looking after the kids? An overview of child abuse and child protection in Australia. Retrieved January 2006 from http://www.aph.gov.au/library/intguide/SP/Child-Abuse.htm

MacIntyre, D., & Carr, A. (2000). Prevention of child sexual abuse: implications of programme evaluation research. Child Abuse Review, 9, 183–199.

Mackenzie, N.. & Knipe, S. (2006). Research dilemmas: paradigms, methods and methodology. Issues in Educational Research, 16, 1–11.

McWilliam, E., & Jones, A. (2005). An unprotected species? On teachers as risky subjects. British Educational Research Journal, 31(1), 109–120.

National Association for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (NAPCAN). (2007). Child protection week kit. NSW: NAPCAN.

Queensland Catholic Education Commission. (2007). Student protection. Retrieved March 2007 from http://www.qcec.qld.catholic.edu.au/asp/index.asp?pgid=10652&cid=5257&id=126

Sachs, J., & Mellor, L. (2005). ‘Child panic’, risk and child protection: an 338examination of policies from New South Wales and Queensland. Journal of Education Policy, 20(2), 125–140.

Saleeby, D. (1992). The Strengths Perspective in social work practice: extensions and cautions. United States: Addison Wesley Educational Publishers Inc.

Seligman, M. (1996). The optimistic child: proven program to safeguard children from depression & build lifelong resilience. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Scott, D., & O’Neil, D. (2003). Beyond child rescue developing family-centred practice at St. Luke’s. Victoria: Solutions Press.

Singh, P., & McWilliam, E. (2005). Negotiating pedagogies of care/protection in a risk society. Asia Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 33, 115–134.

St. Lukes, & Veeken, J. (1997). The bears (cards). Bendigo: St. Lukes Innovative Resources.

St. Lukes & Veeken, J. (1999). Strengths cards for kids. Bendigo: St. Lukes Innovative Resources.

St. Lukes. (2007). The scaling kit. Masman, K. (Ed.). Bendigo: St. Lukes Innovative Resources.

The Abused Child Trust. (2003). Statistics on child abuse and neglect – Queensland data. Retrieved February 2007 from http://www.abusedchildtrust.com.au/index.htm

United Nations. (2006). The state of the world’s children 2003. UN Secretary-General’s Study on Violence against Children. USA: UNICEF Publications.

Walsh, K., Schweitzer, R., Bridgestock., & Farrell, A. (2005). Critical factors in teachers’ detecting and reporting child abuse and neglect: Implications for practice. Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology.

Watts, V. (1997). Responding to child abuse: a handbook for teachers. Rockhampton, Qld: Central Queensland University Press.

Watts, V., & Laskey, L. (1997). Where have all the flowers gone? Child protection education for pre-service teachers in Australian universities. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 25(2), 171–176.

Webb, R., & Vulliamy, G. (2001). The primary teacher’s role in child protection. British Educational Research Journal, 27(1), 59–77.

Whiteside, S. (2001). Personal safety curriculum in junior primary classrooms: are teachers teaching it? Children Australia, 26(2), 31–36.

1 The term Strengths Approach can be used both as the name of the approach as developed by St. Lukes (McCashen, 2005) or as a descriptive term for related practices. Where I use it in the first sense, I use capitals, in the second sense, lower case.