6

Examining the range of strategies mothers use to cope when caring for a child with an intellectual disability.

Introduction

The functions of a family, including reproduction, care of the individual and education can be disturbed in a family that has a member with a disability or special education needs. In such families there are reports of heightened levels of stress (Mulroy, Robertson, Aiberti, Leonard, & Bower, 2008) and, at the same time, a need to acquire strategies for coping with stress (Twoy, Connolly, & Novak, 2007). While there may be a number of variables that may contribute to heightened levels of stress in these families (e.g. socio-economic status, marital harmony) this paper is primarily concerned with the stresses identified in caring for a child with a disability.

A number of studies highlight the stress factors influencing the functioning and the well-being of families of children with an intellectual disability (e.g. Baker, Blacher, Crnic & Edelbrock, 2002; Emerson, Hatton, Llewellyn, Blacher, & Graham, 2006; Mulroy et al., 2008; Margalit & Kleitman, 2006; Oelofsen & Richardson, 2006). The coping strategies developed by families to overcome or manage these stressors are not always clearly articulated due to the type of research methodology (e.g. use of surveys, questionnaires) and depth of analysis. The use of a more open-ended interview based methodology may assist in realising, to a greater extent, the stressors families face, and the coping strategies they develop.

The purpose of this paper is to identify those variables that create stress in the lives of mothers caring for children aged five to 13 years with an intellectual disability, and examine the range and type of coping strategies 142reported by mothers to address these stressors. In conducting this study, parents were selected by a mediating service (i.e. the school), evidence of stress was established through more than one source of data (i.e. survey, interview) and stressors and coping strategies identified through analysis of interview data. Concluding commentary will focus on future research being conducted into coping and stress in families raising a child with an intellectual disability.

Literature Review

There are a number of models that conceptualise the stress and coping process in families of children with an intellectual disability. The general model of transactional stress posed by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) indicates, ‘an individual’s response to a potential stressor is determined by a two-stage process of appraisal’ (Oelofsen & Richardson, 2006, p. 1). An assessment is undertaken of the current stressor and the existing resources are thus examined in light of their suitability in coping with the potentially stressful situation. Coping, in this model, as within a number of models, is defined as the manner in which the person engages or interacts with their environment in order to deal with the stressor. This interaction could differ from one occasion to another, depending on personal resources (e.g. well-being), and other events that may mediate the interaction (e.g. drawing on external services).

The ‘Process Model of Coping’ by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) continues to be the foundation of research in the area. It articulates two groups of coping strategies, emotion-focused coping strategies (e.g. relaxation, religion, avoidance of stressful situations, releasing emotions by crying/laughing, adopting the ‘one day at a time’ approach to life, developing further as a person) and problem-focused coping strategies are also cited. The problem-solving coping strategies are further divided in relation to those that are directed at an external source of stress (e.g. learning a new skill, asking for social support for practical help, believing in improvement in terms of their children’s abilities, searching for information) and those directed at an internal source of stress (e.g. cognitive reappraisal, reminding oneself how much worse the situation could be, drawing on strategies learned from professional support).

143The model posed by Lazarus and colleagues (e.g. Lazarus, 1996, 2000; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) to conceptualise the stress and coping process has been the basis for other models. The Double ABCX model of family stress and coping developed by McCubbin and Patterson (1983), for example, draws from the model by Lazarus and Folkman (1984). The adjusted model posed by McCubbin and Patterson includes two key variables important for intervention in families when supporting adaptation to stress. These are (a) use of family resources and (b) perception of stressful events (Orr, Cameron, & Day, 1991). While this model retains the first part of the model proposed by Lazarus and Folkman (i.e. the assessment stage), it places an emphasis on time and situation (e.g. number of demands being placed on the parent), and ‘the mediating influence of adaptive resources … on parental coping’ (Oelofsen & Richardson, 2006, p. 2). These resources complement those identified by Folkman, Schaefer and Lazarus (1979) which included (a) general and specific beliefs, (b) health/energy/morale and (c) utilitarian resources (e.g., money, tools, training programs).

The purpose of this study is to (1) investigate the level and sources of stress experienced by mothers of children with an intellectual disability and (2) to examine the coping strategies used by the mothers to resolve or minimise the impact of these stressors.

Methodology

The presented research focused on the life experiences of mothers of school-aged children with an intellectual disability, with the aim of gaining a deeper understanding of the stressors in the families and the coping strategies the families adopted in order to cope with the stressors. As the researchers were aware of the complexity of the social context of their research, they decided to incorporate both quantitative and qualitative techniques of research. As stated by Morse (2002; in Mertens & McLaughlin, 2004), ‘by using more than one method within a research study, we are able to obtain a more complete picture of human behaviour and experience’ (p. 113).

For the purpose of this research, the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form (PSI-SF) was used to identify the level of stress within families. This measure has been used in previous studies examining stress and coping in 144families caring for a child with an intellectual disabilities (e.g., Most, Fidler, Laforce-Booth, & Kelly, 2006; Shin, Nhan, Crittenden, Flory, & Ladinsky, 2006). This measure has robust technical adequacy and overcomes the short comings of not having a strong measure of mothers well-being identified in previous studies (Emerson et al., 2006)

A semi-structured interview was designed to follow the life history of the family with a focus on bringing up their child with an intellectual disability. This approach allowed for an open-ended approach, ensuring that mothers experiences were not limited. The life history approach allowed greater insight into ‘the life experiences of individuals from the perspective of how these individuals interpret and understand the world around them’ (Gall, Borg, & Gall, 1996, p. 604).

The life history approach allowed the researchers to ‘examine how [mothers] talk about and retell their experiences and perceptions of the social contexts they inhabit.’ (Goodson & Sikes, 2001, p. 1). This approach permitted the relationship between the mother, their child and family, as well as their community to be explored over a period of time. It also allowed for the development of coping strategies to be examined over time, and whether they changed as a result of time.

Participants

Participants were drawn from two schools in metropolitan Sydney catering for students with special education needs. The primary diagnosis of each child in these two schools was a mild to moderate intellectual disability. Students in a number of cases had secondary diagnoses (e.g. autism, sensory disability, mental health issues). The education programs formulated for each student were based on the aims and the priorities that had been identified through an individual planning process.

Each of the two schools had more than 60 students enrolled with intellectual disabilities; these students were in classes from Kindergarten to Year 12. The schools were located in middle-class socio-economic areas of metropolitan Sydney. Students participated in their educational programs in classes comprised of six to eight students led by a qualified teacher, who was assisted by a teacher’s aide. One of the schools had a strong religious base, and this influenced their education programs, and the way that students, staff and parents engaged in school programs.

145A total of 13 mothers were interviewed as part of the study reported in this paper. One participant did not have English as a first language, and therefore questions required careful articulation and wording. Another mother undertook the interview based on her experiences of having two children who had been identified with special education needs.

The 13 mothers ranged in age from 36 to 52 years, with a mean age of 42.2 years. All but two mothers designated that they worked at home; two mothers were involved in full-time work that fitted in with their child’s school hours, while two mothers stated that they saw their role at home as their primary employment, but undertook part-time paid employment. From the group, 10 of the mothers were in a relationship (i.e. married or a long term partnership), the remaining three mothers being separated or divorced after the birth of their child with a disability.

The children with disabilities came from thirteen families. The mean age of these children (10 male, four female) was 10.2 years (range: 5.1 to 13.5 years). In 11 families there was more than one child (including the family with two children with a disability). In four families the child with a disability was the oldest, while in eight families the child with a disability was the youngest member of the family. The remaining two children were the only children in the family.

Procedure

Mothers involved in this study were drawn from two schools, schools with which the second author had professional links. Within these schools, staff was seeking to understand more about the needs of families in their school (e.g. stresses they faced, how the school may assist). Hence, this study was undertaken as part of work by the authors, while providing independent information to the school executive and community. Information was provided on those variables that parents found stressful, what strategies they were using to overcome these stressors, and how to formulate a way forward for addressing these stressors in the future.

Parents of children involved were sent a participant information letter to outline the project. The letter was delivered to parents via directors of those schools involved. On return of a signed consent form, signed in all cases by the mother of the family, a member of the school executive contacted mothers to arrange a time for them to visit the school and participate 146in an interview conducted by the second author. Across the two schools, four days were set aside to conduct the 13 interviews.

When mothers attended the interview, they were welcomed to the school by a member of the school administrative staff. The second author conducted interviews in the room allocated to the school counsellor. This room was typically quiet, and provided privacy for the interviews. The participating mothers were reassured that the interview would be confidential, that the interview would be audio-taped, and they could withdraw from the interview and study at any time. The interview followed a semi-structured interview protocol, which guided the mothers through a history of experiences related to their child. The interview questions covered general information (e.g. age, marital status, mother’s educational background). The questions posed also asked for details in regards to the diagnosis of the child’s disability. Other areas of focus, which were reflected in the interview questions, were: (1) the impact of the disability on the relationship of the parents, (2) their experiences with accessing services and schooling, (3) coping strategies adopted by the family in regards to stressors that arose as a result of having the child with a disability, and (4) the mother’s expectations for their child’s future.

The second author, who was experienced in conducting interviews with mothers of children with a disability and sensitive to their needs, conducted the interviews. The first author, and a research assistant, transcribed the interviews verbatim. Transcripts were checked by both authors for accuracy of transcriptions, then analysed by the second author. This strategy for preparing the data allowed the researchers to become familiar with the interviews, and interpretations of voice tone and interview behaviour.

At the conclusion of the interview, mothers were asked to complete the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form (PSI-SF) (Abidin, 1995). This measure had been used in previous research investigating stress and ways of coping (e.g. Hassall, Rose, & McDonald, 2005; Kersh, Hedvat, Hauser-Cram, & Warfield, 2006) and provided a general indication of the level of stress that mothers were experiencing. Mothers responded to 36 items of the PSI, using a five point rating scale of ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree’. The measure comprises a Defensive subscale, three subscales and a total. The mothers were encouraged to question the researcher in case they did not understand the items.147

Results

Parental Stress Index – Short Form

The administration of the PSI-SF permitted a standardised, and well recognised instrument to confirm that mothers were experiencing stressors in their life, and that this stress was higher than typically found in the general community. An examination of the Defensive Response (DR) subscale, an indication of how defensive mothers were in completing the PSI-SF, showed that in general mothers may not have been open in their responses, or may have attempted ‘to present the most favorable impression’ of themselves (Abidin, 1995, p. 55).

The total score on the PSI-SF across the group showed that ten mothers recorded ‘clinically significant levels of stress’ (Abidin, 1995, p. 55). Two mothers reported moderate levels of stress, while one mother was found to be at the 10th percentile. This latter result must be examined with caution when considered in regards to the Defensive Response outcome of 10 (below the recommended minimum of 24). Generally, it was established that the group of mothers interviewed for this study were experiencing significant levels of stress. The following discussion of interview data will be used to establish whether this stress was related to raising a child with a disability, what were some of the major sources of stress, and what strategies mothers used to cope with these stressors.

Interviews with parents

The interview data were analysed using the constant comparative analytic approach to establish themes and patterns within the data relating to stress and coping (Bryman, 2004). Transcripts of the audio-taped interviews were read a number of times by the second author who identified the key words and sentences connected with the purpose of the research (i.e. identification of stressors in the lives of mothers, identification of coping strategies to meet the demands of these stressors).

In the following steps the emerging themes connected with coping strategies were identified and arranged into a synoptic figure. The results were then forwarded to the first researcher who confirmed or questioned interpretations. The penultimate phase was an important part of the analysis process, as both researchers removed themselves from the data for a period 148of three months. The time distance allowed them to see the results with ‘fresh eyes’ and complete necessary adjustments.

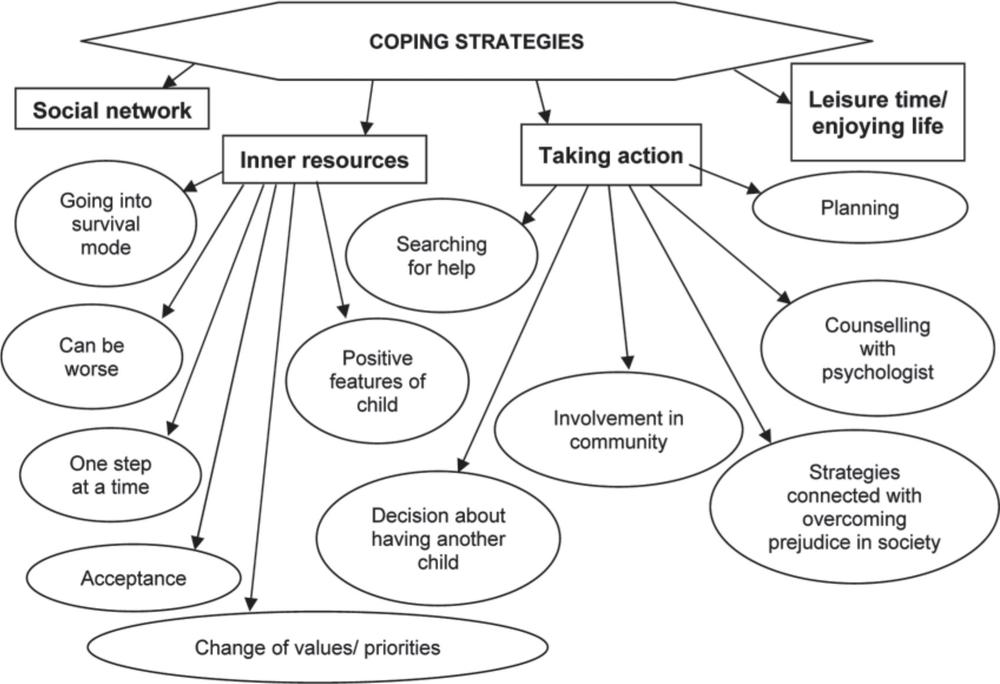

In conclusion, a model of coping strategies used in respective families was formulated and is shown in Figure 1. The major coping strategies developed by mothers of school-aged children with intellectual disability are: (a) building/using social networks, (b) using inner resources, (c) taking action, and (d) being able to enjoy life or to make use of their leisure time. In the following section, each of these coping strategies will be highlighted in the context of stressors identified by mothers.

Building/using social networks. Social networks (i.e. friendship for emotional, physical and social support) with partners/husbands and friends were an important avenue for mothers in developing coping mechanisms in the face of stressful events or processes. These partnerships were, in some cases, themselves the casualties of stressors arising from caring for a child with an intellectual disability. The impact of a child with an intellectual disability on marriage/partnerships of parents was emphasised by a number of mothers.

In the case of those mothers in this study, the financial impact of accessing services to meet the needs of their child with a disability was highlighted.

I would say we were lucky that we never separated the first two years. Definitely … under lots of pressure. Under financial pressure because ABA was very expensive … So, the natural therapies were expensive, ABA was expensive, I wasn’t working, I was at home with a child – with the children, as there wasn’t much difference between both. My husband was working in X, and used to come home at weekends. So I was doing it on my own. I would say that we were very lucky that we survived. (Mother 14)

Though the demands of raising a child with an intellectual disability placed stress on partnerships, it did not necessarily mean that families were dysfunctional (Beckman, 1991) as other factors play an important role in terms of stability of the partnership. For example, one of the mothers noted that past experiences, including the way parents themselves had been raised, played an important part in keeping relationships intact.149

Figure 1. Model of coping strategies in families of children with an intellectual disability.

150The role of the child’s father in caring for the child was addressed in the interviews. The manner in which fathers coped with the stresses of raising a child with an intellectual disability was varied and impacted on the type and quality of the relationship between parents. In the words of one mother:

He wasn’t really supportive; I had to really support him … Because the fathers think, ah, that they are the provider of the family. I’ve done this. This is all my fault. You know, that’s what they think. And I’m like, don’t be stupid. This is just … you, know, they really feel guilty like it is their fault. It was really hard for him. (Mother 12)

It could be interpreted in some cases that fathers found a coping strategy in their employment, resulting in mothers feeling lonely and isolated.

I think it was a lot harder for him and I don’t think he accepted it for a long time, for years, probably, well it took a while anyway and so he would work really long hours and travelled a lot so he wasn’t here for a lot of the early years. (Mother 9)

While mothers were sometimes critical about the support from their husband/partner, when asked whether there was anything was missing from her partner in terms of support, one mother responded in the following way: ‘No, he was probably missing from me. I probably gave everything into my son, and put him by the wayside for a little while’ (Mother 14).

Using inner resources. Coping strategies coded from the interviews as inner resources indicated that mothers relied on resources from within to address the impact of stressful events. Mothers, for example, mentioned the ‘one step at a time’ approach.

We just get over one thing at a time. At first I would try and think, you know, about all of her life. But then you can’t do it. You stress out. One thing at a time, get over this hurdle, then we get over the next. (Mother 12)

Some mothers highlighted an approach that was seen as going into survival mode. In the following example, this ‘survival mode’ impacted negatively on the opportunity to draw support from social networks.

… school holidays, the Christmas holidays, the six week ones, are really hard and I just tend to stop and I tend to go into survival mode, and I just stop ringing friends and stop going 151anywhere because it’s just too hard, so I think that’s just a coping mechanism. (Mother 9)

An important inner resource for mothers when coping was focus on the positive features of the child. Most mothers mentioned the loving and empathic personality of their child with an intellectual disability. In the words of a mother of five children:

She’s loving, she’s different than the other kids. She will come … she asks me all the time, ‘Mum, but are you okay?’ You know, like it’s different, you know. They’ve got a different personality, they are loving, and they want cuddles, yeah, yeah. She always tells me that she loves me. The other kids do too, some don’t … a couple of them don’t. (Mother 12)

The mothers were also able to reflect on the way that parenting a child with an intellectual disability had changed them in terms of their values, priorities and personality. In reflecting on the impact on their lives, mothers were also aware of how they had become stronger. Many mothers mentioned patience, humility and being a better advocate for their child as the most important areas in which they had changed.

… it made me see what’s important. And it taught me a lot of things. It taught me patience, like I’ve always been a pretty patient person, but it taught me to have much more patience … Humility, I suppose, I don’t know, but … special children teach you a lot. [That’s true.] Because they have to go through so much … that other people take for granted, and even like their parents take for granted, it just, it knocks, it just knocks you over. The respect and the love you have for them. (Mother 13)

I think … in the beginning you don’t think it makes you better, no, you hate God. You know, my husband disbelieved everything. I think now over the years, it does make you a better person over all, yeah, it does. (Mother 12)

While mothers reflected on the positive impact of their child on them personally, they were also open about how they sometimes consider less positive feelings. One mother, for example, indicated that having a child with intellectual disability changed her in a negative way: ‘…you sort of 152lose yourself, you become a disability mother and you forget who you are’ (Mother 11). This negative state seemed to be linked, however, to where parents were in their acceptance of their child strengths:

I think when we were trying to do all the things to cure him, that’s when the family was under the most stress. I think once we actually accepted the fact that this is it, this is what we have got, we can make him better but can’t change the fact that he has got autism. Then the family settled down. (Mother 14)

Taking action. In contrast to the use of inner resources, taking action strategies involved parents undertaking overt actions in advocating for their child. A common ‘taking action’ approach was to regularly seek medical advice for themselves and/or their child (e.g. psychologist or psychiatrist), and actively looking for help from within educational, community services, or health systems to help meet the needs of their child.

In a number of cases, however, these services were the source of considerable stress (e.g. waiting lists for therapy services that extended beyond 18 months, services where staff were not appropriately trained to meet the needs of a child with a disability, limited access to early intervention services). Mothers in a number of cases felt they were helpless in overcoming these obstacles, despite their actions of requesting access to services and putting their child’s names down on waiting lists. These significant obstacles were a source of significant stress that in more than one case reduced mothers to tears.

A number of mothers reported their actions of seeking out alternate services for their child. This was a typical action in the early stages of identifying whether their child was having difficulties in their development, as early intervention services were often slow to come available:

… we tried alternative medicine before we tried traditional treatments. We have never tried drugs with him. We tried all the natural treatments, and we have done a lot of ABA, you know the … We have done the Lovas program, we done Lovas for about two and half/three years. (Mother 14)

Accessing early intervention services was an action taken by all families involved in this study. The number of services available was reported by mothers to be insufficient, and this created considerable stress. The bureaucratic 153nature of accessing services was found to be bewildering and puzzling, while in some cases the annual nature of funding left families unsure about continuity of services. In these cases families took action, and sought out alternate services (e.g. diet, herbal therapies). This action is in line with findings from a recent study by Roberts and colleagues (2007), where some families with a child with autism reported to have accessed more than twenty therapies and services for their child.

As a group, mothers were worried about the future of their child, especially what would happen once they, as parents, were no longer there. As a result, families were involved in a range of problem solving actions in regards to future planning for their child. Mothers outlined strategies that included making financial arrangements for their child, envisioning siblings of the child with an intellectual disability to be prospective caregivers, or building support networks with other parents/friends or relatives to ensure life-long care for their child.

I’m quite at peace with the fact that my oldest son will probably always need somebody to make decisions for him or sign things for his welfare. And, ultimately that responsibility will fall to his siblings because my birth family is not up to that and I’m perfectly aware of that. So, I … my thinking was that God gave us my youngest child so that the burden would be shared, not all squarely on my second born son’s shoulder because it is a big job. And as his mother who loves him the most, I am perfectly aware how much of a right it is. Look I know about caring for him later on, but I’m quite at peace with the idea that my son will be with me until the day I die. And then, they look after caring for him, but it will still be on their shoulders. It will still be up to them, so they have got each other then, which gives them not only feedback but somebody else to … burden, share the load with. Because it is, it’s a huge load. (Mother 18)

In another instance, the mother was pregnant with a second child, with an expectation this child would provide support to their brother with a disability in adulthood.

I would also hope that a sibling would help. Absolutely, that’s … whether a child has special needs or not, that’s a duty as a family member, like I look after my mother who lives nearby, 154and that’s a welcome duty. So, that’s also the other contributing reason for having, pursuing a sibling, for my son. (Mother 7)

When mothers were asked to make a wish about what they would like from life, in many cases their wishes focused around ongoing, and safe care for their child with a disability. The mother of a child who required long term care stated:

For her health, to make sure that her health would be good. And then also for her to look more like one of us. I suppose, if they could get her the best they can get her. And then … I don’t know … support for … her brothers to keep an eye on her all through life, you know. (Mother 12)

In other cases, mothers highlighted plans that involved considerable financial planning within the family in order to overcome the concern about what would happen to their child with a disability once they were unable to care for them. One mother stated that, ‘Financially I have set him up with shares. Security wise he will have the house that my husband and I have when it is our time to pass away’ (Mother 7).

Other mothers indicated they had undertaken substantial plans for their child using a combination of financial resources, and network supports they had developed. For example, one mother stated:

We have got another three friends who have got children with disabilities, and what we are hoping to do is eventually buy somewhere between the four of us and try and get the children in there. And to get the government to provide a full time carer, but for there to always to be one parent or one sibling as a carer so there is always somebody from the inside. (Mother 14)

A source of stress for some mothers was evident around the way people in their environment reacted to their child. Despite the general climate toward people with an intellectual disability changing over the last two decades, the reactions of some people to a child’s disability appeared to be negative. One of the mothers admitted her anger about ongoing comments made by people in public about the behaviour of her son, and her action was to withdraw from going into some public domains.

I actually physically stopped going to our mall for like eight months because I just was not in the place where I could not, 155not say anything anymore. I actually nearly slapped a woman, it was only that I had my son with me that stopped me. And because, honestly … it was somebody my own age. That’s what horrified me most. That’s somebody who is as educated as I am in the … because no person that age isn’t educated in Australia in this day and age. A well dressed woman, with children of her own, obviously, you know, just a normal person. Having somebody my own age behaving in that way was just horrifying to me. (Mother 18)

Some mothers gave up on efforts to explain to the public their position, and coped by way of silent ‘resignation’ or an ‘acceptance of the status quo’.

Like people look at her. There is something different about her and they look at her. In the beginning it used to annoy me. A couple of times, a couple of old people … when she didn’t have her fingers released, they used to say, ‘Look at that, look at her fingers.’ They used to go, ‘It looks like she has got mittens on.’ In the beginning, it used to annoy you a little bit, but then it never used to. You used to, like, want to educate people like it’s … it didn’t worry me. (Mother 12)

A major source of stress for mothers was centred on making a decision whether to have another child, with the knowledge that they already had a child with a disability. In 10 of the families represented in this study, the child with a disability was the only or the youngest child in the family.

I was scared … if it wasn’t for her pediatrician, suggesting for me to have more kids. It would be good, it’ll be good for her, you know. And I did, I did … but having the one after her was very scary, because we didn’t have that feeling, it’s all scary. And then when I pushed him out, I wouldn’t open my eyes. But has he got eyes, are his lips all right? Has he got a nose? I was so scared. My husband was going, ‘Open your eyes, he’s alright’. (Mother 12)

Mothers who gave birth to another child after the birth of their child with a disability articulated their anxiety about the possibility of having another child with a disability. While celebrating the arrival of each child, and identifying the valuable learning experience that surrounded raising her some with a disability, one mother echoed this anxiety:156

Because I am terrified, I am absolutely terrified and won’t be happy until he is two. Oh, look it’s just as much as you reconcile yourself during pregnancy that it’s a risk, because I had every test known to man this time … and you say that you are okay with it. I am still very anxious. And, we are actually involved in a few programs so that I can have professional feedback along the way to make sure, because, I am anxious and once it’s in your family there are chances. And him being male scares me, because my second son is okay but, it’s the higher incidence of males being affected that scares me. But, having said that I am much more capable and educated this time about play and the sort of play to look out for and what changes ..and just by being insistent you get to know lots of things. (Mother 18)

In the words of one mother, giving birth to a healthy son following the diagnosis of her first son with a disability was a defining moment in her life.

I was already pregnant before my son’s problems had started to show. They are actually only 21 months apart. So, having the second son come through okay was also a defining moment because it meant that I didn’t just make broken babies. (Mother 18)

Being able to enjoy life or to make use of the leisure time. Mothers were aware of the necessity to relax and take opportunities to enjoy life, however, they often lacked the chance to do so. The ability to relax is also dictated to a degree by the age of the child. Mothers participating in this study often mentioned that, during the first years of parenting a child with an intellectual disability, constant care of the child was required. As time passed, the feeling of being exhausted became apparent for these mothers and they realised the need to relax.

The most common ways of relaxation were: reading, sporting activities, taking the opportunity to sleep or visit friends.

I really like to walk, so of a morning I always try and get up before everyone gets up. I go for a walk, and plan the day. That relaxes me, and gets me ready for the day. And I always feel that no matter how stressed out I am at the end of the day I always feel better if I have been for that walk in the morning. Because I know that I have my time, that time for myself. And 157I have to say it, I like a glass of wine when my daughter goes to bed. I go out into the backyard, and sit out the back and have a glass of wine, in the cool, whatever, watch the news or something, and I enjoy that. I do that most nights. I have a glass of wine, and just try and unwind a little bit. (Mother 13)

Finding time to relax was also achieved through accessing respite care services. Gaining access to this service was a source of great stress to a number of mothers, with the perception that government services, or the support of respite care, was being reduced or eliminated. In the case of one mother, who claimed that support networks had broken down from stress arising from issues related to caring for her child with a significant intellectual disability with severe behaviour difficulties, to access respite services on a regular basis was a major source of stress. In this case, the coping mechanism adopted was based on drawing from inner resources, as taking action was ineffectual with government agencies with limited resources. She also resigned herself to meeting the needs of her child through her own skills and knowledge as she did not have the financial resources to fund respite and therapy herself.

Discussion

The study reported in this paper investigated the level and sources of stress amongst 13 families with a child with an intellectual disability and the strategies that the mothers used to cope with these stressors. Using an interview protocol, this study reported the coping strategies that mothers and families used to respond to various stressors they linked to raising a child with an intellectual disability.

The mothers in this study showed, through scores reported on the PSISF, evidence of stress levels that were higher than the general population of parents. This outcome supported findings of previous studies (e.g. Margalit & Kleitman, 2006; Oelofsen & Richardson, 2006; Twoy et al., 2007), those families raising a child with an intellectual disability report higher levels of stress than those families who are not raising a child with a disability. This observation should not be taken as making a specific or causal link between to the two areas, but mothers in this study were clear in reporting that caring for a child with a disability was challenging and rewarding, but at times stressful.

158Participants provided evidence of a number of sources of stress related to raising a child with an intellectual disability. Common sources of stress were connected with negative attitudes of some people in their environment towards their child, and service provision. Provision of services during the early stages, when establishing the nature and severity of a disability, was a particular source of stress for mothers, followed by difficulty in accessing sufficient, quality early intervention services. As children reached school age, stress focused around locating an appropriate education setting and program, and sufficient respite care to allow families to manage demands of life, relationships and other children.

The strategies for dealing with service agencies were mixed. Mothers generally reported that if they were able to access services, the quality of it was sound. Stress arose in terms of accessing a sufficient quantity of services. A couple of families reported they had spent large amounts of money in purchasing alternate, non-government services. These services provided in excess of 20 hours of therapy per week, the recommended minimum number of hours of early intervention for students with autism (Roberts & Prior, 2006). As a result, mothers made changes to their lives and the priorities they had for themselves and the family.

The value of providing services to families in order to cater for a child with a disability was considered essential by families, yet appears to be discounted by governments and services at most parts of the journey that parents in this study had traveled. Health services, for example, are often responsible for delivering the news to parents that their child has a diagnosed disability. This task is not an easy one, yet is essential to assist parents to access services. Mothers in some cases (e.g. where a disability was clearly evident at birth or in the first months) reported how these services were immediately available and supportive. However, a number of mothers reported, in very emotional terms, stories of having to fight for service provision (i.e. taking action or advocating for their child), or for acknowledgement of their concerns about their child, because health services were reluctant to make a definitive decision that a child had a special need or disability. The results of this study found that the indecision in responding to parental concerns about their child’s significant difficulties was a stressor for parents. The results of this study point to a need for a review of how children are identified as being eligible for early intervention 159services. That is, provision of assistance to access services in cases where a child is not reaching typical milestones, but has yet to be given a recognised diagnosis (e.g. intellectual disability).

The results of this study, supported by other researchers (e.g. Turnbull, 1985; Behr, 1990; Stainton & Besser, 1998), highlight the need to bring the positive aspects of parenting a child with a disability to the attention of professionals, and to use these findings when working with families (e.g. support groups facilitated by professionals who can help parents to address stressors that may be linked to caring for a child with a disability). This study, for example, uncovered positive stories about support agencies, with schools rated by parents as being sensitive to their needs.

An underlying source of stress from mothers was the long-term wellbeing of their child with a disability. In some cases mothers had adjusted their life priorities and accepted that they would be responsible in some way for the care of their child until their death. Mothers also made it evident that they had considered alternate plans leading up to this time, and beyond. This included expectations that siblings would care for the child, financial arrangements for ongoing professional care, and the use of support networks (e.g. joining forces with others families with a child with a disability to establish a community house with part care provisions). This finding is supported in part by research by Taunt and Hastings (2002), who reported that while some families were anxious about the long-term future of their child with a developmental disability, in general families had positive perceptions about their child’s well-being.

Mothers in this study were found to have developed, over time, considerable inner strength in regards to advocating for their child with a disability. In some cases they felt they needed to deal with the stress of people in the community making judgments about them and their child by taking action (e.g. reacting to comments, explaining to people their child’s condition). On other occasions, it would appear that mothers felt that taking a deep breath, or drawing on some inner source of strength (e.g. ‘one step at a time’, going into survival mode) would allow them to cope with stressful events. The one strategy that was not apparent in this study, but had been found in previous research, was the reliance on spiritual or religious beliefs (Bayat, 2007; Taunt & Hastings, 2002).

160Mothers and families drew strength from, or considered there to be a positive impact of, raising a child with a disability (e.g. greater compassion, greater confidence in themselves). These results concur to some extent with work by Scorgie and Sobsey (2000) who reported that some families went through similar personal transformations as those in the study when raising a child with a disability. These authors reported findings that were not found in this study to the same degree. That is, some parents went through personal transformations (e.g. advocacy for their child, changed role in their community from being in a community to being part of a community), relational transformations (e.g. stronger marriage, expanded friendship network) and perspective transformations (e.g. a feeling of serving others).

The interview data in this study were analysed to identify a number of stressors and the coping strategies used by mothers to manage the demands of these stressors. The analysis of data identified a number of coping strategies that were organised around the variables in Figure 1. An examination of these strategies provides ongoing evidence to support the Process Model of Coping posed by Lazarus and Folkman (1984). The interview data shows that emotion-focused and problem-focused problem solving strategies are predominant, linked, and are interdependent on each other (Lazarus, 2000). In this study, mothers who were stressed when dealing with agencies (e.g. lack of respite care) often drew on inner resources to cope with this stressful event (e.g. ‘one day at a time’, focusing their energies around the variables that they could manage).

This study reported the outcomes from thirteen mothers raising a child with an intellectual disability. MacDonald, Fitzsimons and Walsh (2006) reported that female caregivers tended to use problem solving coping strategies more than male caregivers. While this comparison was not possible to confirm in this study, the results correspond with our study in that mothers were perceived as more efficient when developing problem solving strategies of either an active (i.e. taking action approach) or passive (i.e. inner resources) nature. The general perception of fathers, or partners, by the mothers in this study was that they found it difficult to cope with the stress of raising a child with a disability. This perception does not match the outcomes reported by Trute, Hiebert-Murphy and Levine (2007) who found there to be no gender difference in regards parental appraisal of the impact of a child with a developmental disability.

161While the failure to include fathers is a limitation of this study, it provides fertile ground for future research in the area. The authors of the study are also aware that they interviewed a small number of mothers, from two schools, in a middle class area of Sydney. While caution is required in interpreting the results of this study, a number of findings support the work of previous research in the area. However, the life history approach to collecting interview data allowed for a differing perspective to be taken on the experiences of mothers caring for a child with a disability. Further studies could advance the use of this methodology, while also addressing the limitations listed above.

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to examine the stresses parents faced in raising a child with an intellectual disability, and the strategies that they have developed in order to cope with these stresses. The mothers in this study had developed a wide range of coping strategies, including the use of support systems offered within their social network, how they viewed and advocated for their child, and using inner resources to explore ways of enjoying life and relaxing. The knowledge of different – and undoubtedly very individual – coping strategies might help professionals working with children with intellectual disabilities and their families to answer their needs in a more appropriate way.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the mothers who participated for their readiness to share their life experiences in regard to parenting a child with an intellectual disability. We would also like to express our thanks to directors of schools who supported us by allowing us to approach these families.

References

Abidin, R. (1995). Parenting stress index (3rd edn). Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Baker, B., Blacher, J., Crnic, K., & Edelbrock, C. (2002). Behavior problems and parenting stress in families of three-year-old children with and without developmental delays. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 107(6), 433–444.162

Bayat, M. (2007). Evidence of resilience in families of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51(9), 702–714.

Beckman, P. (1991). Comparison of mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of the effect of young children with and without disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 95(5), 585–595.

Behr, S. (1990). Positive contributions of persons with disabilities to their families: literature review. Lawrence: Beach Centre on Families and Disability.

Bryman, A. (2004). Social research methods. 2nd Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Emerson, E., Hatton, C., Llewellyn, G., Blacher, J., & Graham, H. (2006). Socio-economic position, household composition, health status and indicators of the well-being of mothers of children with and without intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(12), 862–873.

Erwin, E., & Soodak, L. (1995). I never knew I could stand up to the system: Families perspectives on pursuing inclusive education. Journal of the Association of Persons with Severe Handicaps, 20, 136–146.

Folkman, S., Schaefer, C., & Lazarus, R. (1979). Cognitive processes as mediators of stress and coping. In V. Hamilton & D. Warburton (Eds), Human stress and cognition: an information-processing approach (pp. 265–298). London: Wiley.

Gall, M., Borg, W., & Gall, J. (1996). Educational research. An introduction. 6th Edition. USA: Longman.

Goodson, I., & Sikes, P. (2001). Life history research in educational settings: learning from lives. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Gray, D. (2006). Coping over time: the parents of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(12), 970–976.

Hassall, R., Rose, J., & McDonald, J. (2005). Parenting stress in mothers of children with an intellectual disability: the effects of parental cognitions in relation to child characteristics and family support. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(6), 405–418.

Kelso, T., French, D., & Fernandez, M. (2005). Stress and coping in primary caregivers of children with a disability: a qualitative study using the Lazarus and Folkman Process Model of Coping. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 5(1), 3–10. 163

Kersh, J., Hedvat, T., Hauser-Cram, P., & Warfield, M. (2006). The contribution of marital quality to the parents of children with development disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(12), 883–893.

Kirmayer, P., & Pinnes, N. (Eds). (1997). Adult education in Israel II-III. Jerusalem: Publications Department, Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport.

Krauss, M., & Seltzer, M. (1993). Current well-being and future plans of older care giving mothers. The Irish Journal of Psychology, 14(1), 48–63.

Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Coping and adaptations. In W. Gentry (Ed.), Handbook of behavioural medicine (pp. 282–325). New York: Guildford Press.

Lazarus, R. (1999). Stress and emotion: a new synthesis. New York: Springer.

Lazarus, R. (2000). Towards better research on stress and coping. American Psychologist, 55(6), 665–673.

Lustig, D. (2002). Family coping in families with a child with a disability. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 37(1), 14–22.

MacDonald, E., Fitzsimons, E., & Walsh, P. (2006). Use of respite care and coping strategies among Irish families of children with intellectual disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35, 62–68.

Margalit, M., & Kleitman, T. (2006). Mother’s stress, resilience and early intervention. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 31(3), 269–283.

Mertens, D., & McLaughlin, J. (2004). Research and evaluation methods in special education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Most, D., Fidler, D., LaForce-Booth, C., & Kelly, J. (2006). Stress trajectories in mothers of young children with Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(6), 501–514.

Mulroy, S., Robertson, L., Aiberti, K., Leonard, H., & Bower, C. (2008). The impact of having a sibling with an intellectual disability: parental perspectives in two disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52(2), 216–229.

Oelofsen, N., & Richardson, P. (2006). Sense of coherence and parenting stress in mothers and fathers of preschoolchildren with developmental disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 31(1), 1–12.

Orr, R., Cameron, S., & Day, D. (1991). Coping with stress in families with children who have mental retardation: an evaluation of the double ABCX model. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 95(4), 444–450. 164

Prior, M., & Roberts, J. (2006). Early interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders: guidelines for best practice. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing.

Roberts, J., Dodd, S., Parmenter, T., Evans, D., Carter, M., Silove, N., Williams, K., Clark, T., Warren, A., & Pierce, E. (2007). Evaluation of outcomes of early intervention programs for children with autism and their families. Paper presented at European Autism Conference, Oslo.

Roberts, J., & Prior, M. (2006). A review of the research to identify the most effective models of practice in early intervention of children with autism spectrum disorders. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing.

Scorgie, K., & Sobsey, D. (2000). Transforming outcomes associated with parenting children who have disabilities. Mental Retardation, 38(3), 195–206.

Shin, J., Nhan, N., Crittenden, K., Flory, H., & Ladinsky, J. (2006). Parenting stress of mothers and father of young children with cognitive delays in Vietnam. Journals of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(10), 748–760.

Stainton, T., & Besser, H. (1998). The positive impact of children with an intellectual disability on the family. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 23(1), 57–70.

Taunt, H., & Hastings, R. (2002). Positive impact of children with developmental disabilities on their families: a preliminary study. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 37(4), 410–420.

Trute, B., Hiebert-Murphy, D., & Levine, K. (2007). Parental appraisal of the family impact of childhood developmental disability: times of sadness of times of joy. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 32(4), 1–9.

Turnbull, A. (1985). Positive contributions that members with disabilities make to their families. Paper presented to the AAMD 109th Annual Meeting, Philadelphia.

Twoy, R., Connolly, P., & Novak, J. (2007). Coping strategies used by parents of children with autism. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 19(5), 251–260.