Chapter 11

RECOVERY OF THE SOUL: SUSTAINABLE REBUILDING IN POST-KATRINA NEW ORLEANS

Although the notion of sustainable development is usually associated with the design and building of new settlements, this chapter illustrates how this notion can also be used to undergird the recovery strategies to rebuild a city struck by a natural disaster. The chapter shows how a sustainable development approach in post-Katrina New Orleans has helped frame post-disaster recovery efforts by applying the following five sustainability concepts: community participation in deciding best strategies for recovery to continue the healing; public safety and security for all neighbourhoods; 100-plus-year time-horizon infrastructure planning; a diverse economy; and sustainable settlement pattern.

Spates of new books and journal articles have attempted to capture the highs and lows of the Hurricane Katrina catastrophe. Some of this work has examined the physical characteristics of New Orleans and asked if the city was built in the wrong place (Vale and Campenella, 2005). Is it now time to rectify this accident of geography? In essence is New Orleans sustainable or can it be made sustainable?. Other work has examined New Orleans as a cultural icon where the forces of good and evil have shaped a unique culture which is under threat from the potential of modern rebuilding paradigms that might disturb the crucible from which the rich music and art spring (Sublette, 2007).

Some work reflects the real pathos of New Orleans with a seemingly intractable set of social problems co-existing in a fragile environment, especially John Barry’s epic volume Rising Tide (1997). All of these emerge from different partially correct prisms from which one can assess this great old city in its time of crisis. But in essence, they miss the real New Orleans which is often described as the Soul of America (Soul City). It is a city with a magnetic past and a character and charm that is unique. Everyone in the world has some form of exposure to New 239Orleans through the countless jazz, rhythm and blues, Cajun and other music that emanates from this cultural capital of the United States.

On August 29, 2005, New Orleans suffered from over exposure. As Hurricane Katrina hit, a new image of New Orleans was broadcast around the world. This was not the image most of the world held of Soul City. What the world saw projected, and to some extent exaggerated, was a City of disorder, racial inequality and poverty along with inadequate national responses to the disaster caused in large measure by the failure of federally built and maintained levees. So, the magic of New Orleans was challenged by the reality of the situation that was presented to the world. Two years have passed since the New Orleans tragedy. In those two years the issues of planning and re-planning have become central to the discourse on New Orleans. This article addresses the dimensions of the planning process and products that are underway, and the many complicated issues associated with trying to put New Orleans back together again. The future of New Orleans rests with its special past without denying its desperate reality if it has any hope of a real recovery.

What is a sustainable plan – New Orleans style?

Almost immediately after Katrina, a planning contest emerged between various New Orleans factions that felt strongly about what New Orleans was and what it should and could be. On one side were the traditional landed plantationists who still owned considerable assets in the form of real estate and business. In the middle were the local neighbourhood activists who viewed the city entirely from what happened in their neighbourhoods. Finally, there were African Americans of all classes who felt disenfranchised and acted as a group to develop and maintain political power.

Planning or re-planning New Orleans challenged the notion that the past is the only foundation for the future. Community interest groups who felt they owned the past; artists, African Americans, and preservationists were challenged by architects and planners who were shaping a new city form to meet the challenges of a new century. This chapter looks at sustainable planning through the prisms of contestants who use it as a vehicle to gain recognition, shape debates and move their agendas forward. It examines how they understand the meaning and 240opportunities for plans to garner an improved position for themselves. What will become evident is that planning and planning tools will shape the future of New Orleans in ways the residents never anticipated (Birch and Wachter, 2006).

Plan as a sustainable problem identification

There is a rich planning tradition of finding problems as the basis for planning (Baer, 1997). This tradition emerges from the systems theory literature. It is based in the concept that if the city, or whatever is being planned for, can be properly diagnosed then good data can be applied to find the correct course(s) of action. In New Orleans, the way one described the problem became a central component in shaping the discourse.

New Orleans had deep problems prior to Katrina. The city pre- and post-Katrina had one of the nation’s highest poverty rates with 23.2% against 12.7% nationally. Moreover, the city segregated large portions of the black low income population in public housing or very substandard private government subsidised (HUD section 8) rental accommodations. The New Orleans median household income of US$27,000 compared to a national median of US$41,000 is among the lowest for major metropolitan areas in the nation. Homeownership rates also fall well below the national median at 45.6% versus the nation at 67.9%. Poverty, low wages and lack of housing are universally associated with crime and social issues in New Orleans. In the decade of the 1990s, New Orleans ranked at or near the top of the murder rate per 1000 with a murder rate 7.54 times the national average and comparable to some of the nation’s largest cities (Earth Day Network, 2005).

All of these problems are compounded by the fact that the New Orleans City schools were taken over by the state of Louisiana because of constant low performance combined with administrative incompetence. One striking feature of New Orleans is that it has an illiteracy rate of 39% among the New Orleans Parish adult low income population (Earth Day Network, 2005). Many of these under skilled and illiterates are products of New Orleans Public Schools. New Orleans public housing authority is in federal receivership by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). 241

The combination of poor schools, crime and low incomes in the city core has pushed both whites and blacks into the suburbs and private education over the last three decades leaving as many as 40,000 vacant lots or abandoned residential properties. The city has one of the nation’s worst violent crime rates averaging over 200 murders per year for the last decade (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2002). This blight depresses home values in all but the most exclusive neighbourhoods as well as acting as a magnet and safe haven for drug consumption and dealing. Moreover, New Orleans had the worst school test scores by grade in Louisiana, a state with one of the nation’s lowest school performance rates (Earth Day Network, 2005).

Overlaying and contributing to the malaise of poverty, residential deterioration and socioeconomic disruption is a fragmented governmental system. At the time of Katrina, there were five different levee boards, which have since reduced to two. The small Orleans Parish of under 500,000 people had 7 tax assessors which will be reduced to one in 2009. There are a myriad of boards of commissions governing the delivery of public services from libraries to water and sewer and even public parks. Even the famous Superdome that graces the city skyline as a premier sporting facility is owned and operated by the state and not the city.

Sustainable planning theorists would immediately suggest that no plan can be formed that merely addressed the flood damage. Yet, some of the earliest approaches to recovering the city such as the Bring Back New Orleans Plan barely recognised these issues and the strong emotional weight that these problems carried for any attempt to deal with the future of the city (Nossiter, 2007).

There is little doubt that the problems of New Orleans have to be acknowledged as a first step in formulating a response to the recovery efforts. To do this, the Office of Recovery Management formed in January 2007, some 18 months after the crisis and headed by the author, offered a 5 point diagnostic framework as the basis for assessing the sustainable challenges from which the city needed to recover (Office of Recovery Management, 2007).

- Continue the healing – recognises that the deep underlying trauma of Katrina started well before the disaster and lay in the deep division 242across race and class. Healing the chasms across the community is an ongoing exercise that the Recovery Office has to play a central role in designing and carrying out. This process, including meetings of all city employees and community groups, is going on as part of the recovery efforts.

- Public safety and security for all neighbourhoods – The depth of fear of crime in the lowest income communities is impeding the return of residents to these areas. Crime is, however, a citywide contagion affecting all areas, so incorporating both crime prevention and crime stopping has become a critical element of the recovery. There are a host of programs including citywide crime cameras along with more community and neighbourhood policing strategies to engage young people in positive social and recreational pursuits. In addition, good schools near home are an important security issue for every parent. Schools are now the community core facilities, with libraries, to act as anchors and form more public open space, dense housing patterns and walkable communities. Finally, good hospitals and clinics are required to deal with both mental and physical health issues. Therefore, a core element of the strategy is to provide every community with access to better health facilities than in pre-Katrina New Orleans.

- Infrastructure for the 21st and 22nd century – Like many American cities, New Orleans has under-invested in the city’s primary infrastructure such as sewers and water as well as other basics. This infrastructure is the bedrock for any new industries and balances the needs of all communities across income groups, as well as meeting the needs of emerging enterprises for better, cheaper and greener technologies.

- Diversify the economy – New Orleans’ economy is based on tourism, energy and retail services. The largest job producers are in low wage service sectors. To combat crime and generate a healthy social economy, new jobs related to the city’s future have to be sought in areas such as bio-medicine, advanced transportation and media.

- Sustainable settlement pattern – is the foundation of any good city. Cities with good neighbourhoods attract people and jobs. While some quarrel with aspects of Richard Florida’s (2002) concepts, the basic message is correct. So, New Orleans has a special burden in 243crafting a re-settlement program that avoids the hazards of the past and builds new communities that are less segregated by income as well as being environmentally and socially sustainable.

These five sustainability concepts act as the problem reference points for taking all of the issues and data and articulating them in a clear way that is both compelling and accurate. In this way, the re-building program will emerge from a process of constructive engagement which the city has been undertaking for nearly two years.

Sustainable direction for planning

To some planning advocates, the process is the plan. How people are engaged in this process ranges from therapy to control (Arnstein, 1969). Engaging citizens with professionals and stakeholders is the core of planning. This engagement in itself has many positive aspects such as creating a collective consciousness as to what the future is and how to get to it. The New Orleans City Council began the planning process in some frustration as a release or therapy for citizen discontent. The Council engaged Lambert and Associates from Florida, a firm well grounded in citizen engagement process post disasters, to assist community groups in the re-planning process. The process planning orientation embedded in the Lambert approach orientation has many inherent problems such as who has a voice in the process. Do bigots have a right to control the outcomes of the process and thus the plan? Is this a consensus approach or do the most votes win? How and what information can be used as the process unfolds? All of these issues surfaced in New Orleans.

At the outset, citizen groups on their own started planning all over the city for their own neighbourhoods or districts. This was problematic in many ways. Firstly, how could these citizens speak for people who were still scattered over 37 states? Secondly, what was the planning goal? With governmental or other frameworks, citizen planning can and was Balkanising the city since each group set its own targets for the planning outcome they preferred with no reference to any other larger citywide goals or visions. The Lambert plans established a very good process of engagement but left open the need to find a customer or client other than each neighbourhood for the plans. 244

Sustainability discourse

Bent Flyvberg noted that: ‘If you want more civic reciprocity in political affairs, you work for civic virtues becoming worthy of praise and others becoming undesirable’ (1998, p. 121). Enter the Rockefeller Foundation with some urging from community leaders offering the city resources and a new set of planners to weave the Lambert and other work into a strategic tapestry to craft new civic virtue called ‘The Unified New Orleans Plan’ (UNOP) (Nossiter, 2007). The UNOP process took a very broad consultation and outreach approach that engaged New Orleanians across the nation. UNOP organised and prioritised citizen input into a wider and deeper document addressing physical, economic and social requirements for recovery. UNOP became the new sustainability discourse/civic virtue setting mechanism for people in all walks of life an opportunity to share their needs, frustrations and visions of what the city might be.

The UNOP process was crafted outside the formal city bureaucracy. In some ways, this was a good idea since bureaucrats tend to narrow agendas. On the other hand, it meant no one in the city government had ownership of it or accepted it as a mandate for recovery. As a result, UNOP became a stalking horse for funding priorities and not a plan for recovery from the Katrina natural disaster. UNOP shaped the discourse about what was needed to be actionable but not the steps to action.

Sustainable action planning

Good plans form good projects. However, we know from many studies that there can be a disconnection between what is planned and what actually happens. In many cases, this is not the fault of the planners or the plan but the decision makers (Innes and Booher, 2004). In the case of New Orleans, plans became an end in themselves. Plan after plan was rolled out by various groups that seldom showed what steps would be taken to implement them (Nossiter, 2007). In most cases, the plans were actually demands on resources rather than actionable problem solving. After nearly two years, there was no direct approach to implementation of any of the previously discussed plans – ‘Bring Back New Orleans’, Lambert, UNOP and others. In order to move beyond this conundrum, the newly formed Office of Recovery Management was tasked by Mayor C. Ray Nagin to pull visible actions in places from all of the documents 245that emerged over the nearly two years of planning at every level including Chamber of Commerce, Philanthropy, Education and a host of other plans by neighbourhood groups like Acorn. Good information and good ideas were contained in all of these plans but the task of organising was daunting.

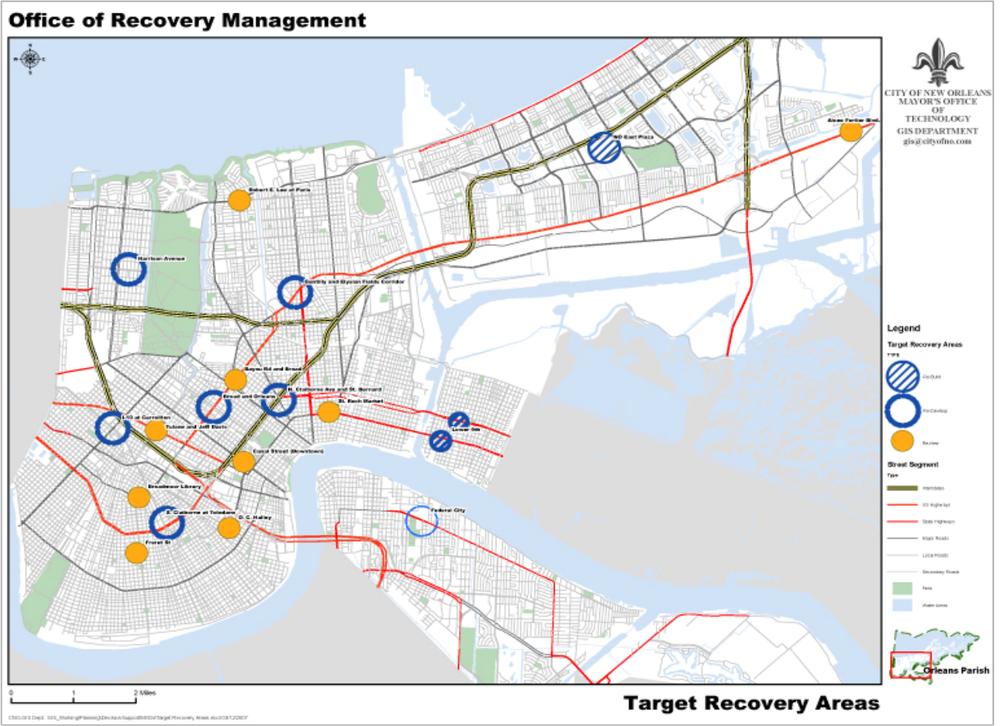

Figure 73: New Orleans recovery areas

Source: Office of Recovery Management (2007)

The approach adopted by the Office of Recovery Management (ORM) was to take the plans from all the different groups and overlay them as problems and/or opportunities on the city geography. In essence, the staff took all of the plans to see where projects and places came together. While this was hard for some plans that did not identify specific implementation geography such as crime reduction of literacy and skill level improvements, each of these issues had a place or geographic node where the problem was more manifest or the 246opportunities for intervention were more coherent. From this data bank, the ORM staff produced a map of places that could be intervention platforms of three logical Target Area types (see Figure 73).

- Rebuild – places heavily damaged by flooding with massive destruction that will require rebuilding from the ground up.

- Redevelop – areas that were blighted pre-Katrina and needed substantial revitalisation of both commercial and retail stocks.

- Renew – communities that were lightly damaged with good housing stock and other infrastructures but only require improvements in civic facilities such as schools, parks, and libraries with small incentives for business revitalisations in commercial corridors or strips.

This approach was vetted with planners and community activists and civic leaders to ensure that it met the spirit as well as the goals of the recovery effort. The Target Areas approach has been well received and is being used as the action plan.

Toward a sustainable future

Plans in the case of disaster need to embody a new sustainable future orientation that people gravitate to because they can identify with this future. In the case of New Orleans, this is a must. New Orleanians are very much in love with their past glory, although few of the current residents have seen or shared much of that glory. Nonetheless, this is the story. A substitute story has to feel good and look good too. In some ways, New Orleans has to recapture the imagination of the American people who have seen the old New Orleans as a parody of its past.

To create a new face and new space, in addition to the sustainable redevelopment strategies outlined above, the city is promoting a sustainable economic recovery by attracting new industries and new transportation technologies that are more modern and contribute to a sustainable economy that is non-polluting. The new New Orleans is one based on Media Technology – the Hollywood South with film studios growing in the old warehouse district; Broadway South based on the use of the central city large old art deco theatres and the strong working performing artists backdrop; biomedicine looking to the new opportunities 247in chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease and maladies related to local and increasingly international lifestyles; transport technologies oriented to the increasing freight – air, sea, rail and ship – moving between Latin America, Africa and China (with the wider Panama Channel) with New Orleans strategically located for this trade with a river, air and seaport connected to six rail roads. So, the new New Orleans is a Sustainable Phoenix rising out of the water to create a new future and a new sustainable dream.

248

References

Arnstein, S. R. (1969) ‘A ladder of citizen participation.’ Journal of the American Institute of Planners. 35(4): pp. 216–224.

Baer, W. (1997) ‘General plan evaluation: an approach to making better plans.’ Journal of the American Planning Association. 63(3): pp. 329–344.

Barry, J. (1997) Rising Tide. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Birch, E. and Wachter, S. (2006) Rebuilding urban places after disaster: lessons from Katrina. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Earth Day Network (2005) Website of Earth Day Network 2005: www.earthday.net (consulted 28th May 2008).

Federal Bureau of Investigation (2002) Uniform Crime Reports.

Florida, R. (2002) The rise of the creative class. New York: Basic Books.

Flyvberg, B (1998) Rationality and power: democracy in practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Innes, J. E. and Booher, D. E. (2004) ‘Reframing public participation: strategies for the 21st century.’ Planning Theory. 5(4): pp 419–436.

Nossiter, A. (2007) ‘New Orleans plans to invest in 17 target areas.’ New York Times, March 30th 2007, p. B1.

Office of Recovery Management (2007) Strategic Plan of the Office of Recovery Management, City of New Orleans, 2007.

Sublette, N. (2007) The world that made New Orleans: from silver to Congo Square. New York: Lawrence Hill Books.

Vale, L. and Campanella, T. (eds.) (2005) The resilient city: how modern cities recover from disaster. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.