Chapter 5

THE IMPORTANCE OF ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE IN BUILDING A SUSTAINABLE NONPROFIT HOUSING SECTOR

Affordable housing is considered one of the main pillars of sustainable urban development, providing shelter close to the place of employment of key support workers on modest incomes. With the recent announcement of the National Rental Affordability Scheme to build 100,000 affordable homes over the next decade, there is a concerted effort to increase housing supply (Australian Government, 2008a, 2008b). Many of these new rental units will be built and managed by non-profit housing organisations. The sector covers a wide range of institutions, from small community-based welfare charities to large professionally managed non-profit developers and arms-length branches of government. To its supporters, non-profit managed housing is responsive to tenants’ needs, locally grounded, preserves affordable housing stock in the long term and can ‘contribute to wider social policy outcomes, like building stronger communities, enhancing employment opportunities and contributing to social cohesion’ (CHFA, 2001: p. 3). Less supportive commentators tend not to criticise non-profit housing’s social outcomes but doubt whether the sector will be sustainable in the medium term due to a shortage of robust organisations and skilled staff.

This chapter reviews the limited research on organisational typologies in countries with similar liberal welfare regimes, focusing on examples from England and Australia. It provides an understanding of the emerging types of non-profit housing organisations using the management theories of new institutionalism, networks, and global convergence. Finally, the chapter proposes a new typology for non-profit housing organisations and suggests how this might assist policy makers create a sustainable non-profit housing sector. Strong non-profit organisations have the ability to produce more sustainable outcomes than private developers by improving social cohesion and reducing commute times. 102

Introduction

The recent growth of the non-profit housing sector in Europe and North America has been spectacular. In England, the Housing Corporation claims housing associations complete one new affordable home every three minutes (Housing Corporation, 2007). After a decade of hesitant and patchy progress in Australia, 2007 appeared to mark a watershed year for non-profit housing providers. New South Wales (NSW) issued a consultation paper in March calling for a ten-year increase of community housing from 13,000 to 30,000 (NSW Department of Housing, 2007). This will be achieved by innovations in asset ownership, stock transfers, commercial financing, public-private partnerships and an initial $120m state grant. On the 1st May 2007 Western Australia announced that out of $376m spending over four years on social housing, $210m would be for non-profit providers – a five-fold increase (Government of Western Australia, 2007). Continuing the largesse, the next day Victoria announced a $510m housing budget with non-profits allocated $300m to build 1550 affordable homes (State Government of Victoria, 2007).

Additional public funding for the non-profit sector is only the first step towards increasing affordable housing supply. Delivery of new homes relies on the skills of the myriad non-profit organisations that manage specific building projects. These organisations have been described in Australia as ‘eclectic and diverse’ (National Community Housing Forum, 2004: p. 10) and in England as ‘extremely complex’ (Mullins and Murie, 2006: p. 207). Given the importance of understanding the types and capacities of non-profit housing providers, this chapter follows new institutional theory (Powell and DiMaggio, 1991) by bringing organisations rather than policy to the centre of the affordable housing debate.

This chapter seeks to provide a clearer though not definitive approach to categorising non-profit housing providers to help track and conceptualise organisational developments in the sector. Building on frameworks developed in organisational theory, a heuristic typology is developed for conceptualising the wide range of institutional vehicles used to deliver affordable housing. Using examples from the non-profit housing sector in England and Australia, four typological questions are addressed. These are: what range of organisations operate in the sector? Where are the sector boundaries and how permeable are they? Are non-profit 103housing providers becoming more similar? Finally, what typologies have previously been used to describe the sector and could a new model provide helpful insights? The chapter aims to stimulate debate in Australia and encourage further cross-national comparison.

Context

The rise of the non-profit housing sector has been at a time when market mechanisms have been used to increase the supply and the range of housing, particularly in countries characterised by Esping-Andersen (1999) as liberal welfare regimes. Expansion of public housing is uncommon and responsibility for supplying new affordable housing has shifted in varying degrees towards non-profit providers. The sector is characterised by ‘innovation and dynamism, the spread of business perspectives, the emergence of hybrid organisations and inter-sectoral partnerships’ (Paton, 2003: p. 1). However, there is a feeling that ‘housing research has not yet critically addressed this changing world’ (Mullins et al., 2001a: p. 621). In particular at the organisational level there has been limited analysis of housing non-profits, restricted to a few countries: England (Mullins and Riseborough, 2000), the Netherlands (van Bortel and Elsinga, 2007), Australia (Milligan et al., 2004; Bissett and Milligan, 2004; NSW Department of Housing, 2007), and Ireland (Mullins et al., 2001b; Rhodes, 2007).

There are a number of drivers for the growth of the non-profit housing sector. Public sector reform has accelerated in many countries since the early 1980s based on the popularity of ‘new public management’ bringing competition and commercialisation within the public sector (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2004). This led to a move from formal structures such as public housing towards greater public funding of non-profit and for-profit organisations which are coordinated with less hierarchical relationships. Described as a move from government to governance, the new policies are ‘characterised by inter-dependence, resource exchange, rule of the game and significant autonomy from the state’ (Rhodes, 1997: p. 15). Non-profits are considered good at catering for groups with specific housing needs such as the elderly, disabled and immigrants. Their properties, constructed over the last two decades, tend to be more spatially and socially dispersed in neighbourhoods, unlike traditionally clustered single-tenure public housing estates (Wood, 2003). By 104involving tenants and local people in decision making, it is claimed that non-profits can better respond to neighbourhood needs and build social capital through strong community networks. Non-profit housing organisations often enjoy wide support across the political spectrum.

While there are certain common trends in affordable housing provision between England and Australia, four important differences need highlighting. First, England continues to have a considerably larger social housing sector with around 2,000 housing associations managing 1.8m homes, some 8% of the total housing stock in 2004 (Hills, 2007: p. 43). In Australia, the community housing sector managed 44,000 properties in 2003, equivalent to 9% of all houses (National Community Housing Forum, 2004: p. 10). Second, the transformation of housing non-profits has been more rapid and started earlier in England, from the Housing Act of 1974 which introduced public funding to the 1988 Act which tilted the balance away from local councils (Malpass, 2000; Cope, 1999). In Australia, the major impetus was the National Housing Strategy of 1991–2 endorsing community housing as a valid social housing delivery model and funding sector capacity building (Bissett and Milligan, 2004). Third, Australia’s housing non-profits are more dependent on direct government assistance than in England as many do not own the properties they manage, and there is a lower level of rent subsidy. Finally, England is a unitary state with a centrally coordinated housing policy even if implementation is localised and shared between local councils and non-profits (Berry et al., 2006). In contrast, there was no Australian Housing Minister from 1996–2007.

Organisational types

The range of affordable housing organisations is broad in terms of their legal constitution, size, date formed, historical development, charitable status, group structure, clients served, property types managed, delegation of decision making, diversification of activities, management style, finance sources, use of volunteers, institutional capacity, religious affiliation, social mission, urban/rural location and involvement of tenants. Several housing non-profits are run like commercial companies although most remain modest in ambition, size and capacity (Light, 2002). Figure 23 provides a broad comparison of non-profit housing organisation types in England and Australia: 105

Figure 23: English and Australian housing non-profit types

| Type | England | Australia |

| [1] Traditional charitable |

Date back to 12th century providing charity for the poor. Sometimes religious links. Most are now in category [2] by having become more commercial and/or merging. |

Most important category in Australia by number of organisations. Generally small, tenancy management rather than new property development. Some 17% managed by church groups. |

| [2] Commercial charitable |

Most important category in England by number of organisations. Normally retain charitable/community status but can raise private finance for new development after the Housing Act 1988. |

Fewer have shifted from category [1] than in England. Some such as City Housing Perth and Port Phillip Housing Association have raised external private finance. Port Phillip retains strong local government links. |

| [3] Government established |

- No examples of establishing new companies for building new homes although government instrumental in establishing categories [4]-[6]. |

Popular for new schemes. Similar to [2] but with more government control (board members or shares). E.g., City West, Sydney (1994); Brisbane Housing Co. (2002) |

| [4] Stock transfer |

Large scale voluntary transfer (LSVT) of public housing estates after Housing Act 1988. Over one million homes transferred, mainly to category [2]. Refurbishment may involve PPP. |

- Under development: e.g., NSW agreed in 2006 to transfer 2,500 properties by 2008. Bonnyrigg (see [5]) will be both a stock transfer and PPP. Stock transfers part of NSW Community Housing Strategy 2007–2012. |

| [5] Publicprivate partnership (PPP) |

Some use for student and key-worker housing. Main use is with councils for public housing refurbishment to meet ‘Decent Homes’ standard by 2010 using Private Finance Initiative (PFI). |

Have been used for break-up/refurbishment of larger public housing estates, e.g., Westwood in Adelaide and a large $500m scheme at Bonnyrigg in NSW. Category [2] normally used for longer term asset holding. 106 |

| [6] Arms-length management (ALMOs) |

Transfer of public housing from direct council control permitted from 2001. Greater tenant involvement and usually funding refurbishment through PFI. 52 ALMOs with 800,000 homes to 2006. |

- No examples. |

| [7] Cooperative and tenant union |

Mainly 19th century growth. Still some existing but generally not expanded as fast as [2] so remain relatively small. |

Tenant managed cooperatives are relatively important although rarely own properties and small (average 9 properties each in NSW). |

| [8] For-profit companies |

Private companies allowed to bid for £137m Housing Corporation funds (Housing Act 2004): first award to Barrett Homes in Jun-06. First private company Pinnacle accredited as a housing manager in Jan-07. |

- No direct examples except involvement in PPPs in category [5], as in England. Occasional joint working with private developers, e.g., Community House Canberra. CSHA 2003 called for greater role for the private sector. |

Source: Housing Corporation (2008); Clough et al. (2002); Milligan et al. (2004); National Community Housing Forum (2004); NSW Department of Housing (2007).

![]() indicates relative importance of organisation type in each country.

indicates relative importance of organisation type in each country.

There are two tentative conclusions from Figure 23. First, government decisions on the future of public housing will have a major impact on the growth of the non-profit housing sector. While England has a wider range of affordable housing providers than Australia, most organisational innovation over the last two decades has resulted from changes to the boundary between public housing and non-profits/commercial companies. Direct property transfers from the public to non-profit sector of nearly 900,000 homes between 1990 and 1072006 (Housing Corporation, 2007: p. 27) allowed the sector to achieve critical mass and source cheap bank finance (Berry et al., 2004). Unlike the stock transfers and semi-independence of much of what remains of public housing in England, Australia’s public housing has remained largely under state control. However, the modest pace of transfers may be set to accelerate, especially in NSW where they form a major component in expanding the non-profit sector to 2017 (NSW Department of Housing, 2006; 2007).

Second, England spent nearly two decades commercialising its traditional housing charities by allowing private finance, encouraging mergers, governance reforms and leveraging developer contributions through the planning system. The English housing non-profit sector therefore grew in size by a combination of stock transfers and organic growth (Bissett and Milligan, 2004). In comparison, the pace of Australian non-profit commercialisation has been modest and traditional charities and cooperatives, with a few important exceptions, continue to concentrate on tenancy management (Barbato et al., 2003). The exceptions include a small number of traditional organisations favoured by state governments for growth such as St George Community Housing, formed in 1986 and part of a consortium awarded the A$500m public-private partnership to redevelop the Bonnyrigg public housing estate in western Sydney in 2006 (St. George Community Housing, 2007). Whilst the 2003–2008 Commonwealth State Housing Agreement (CSHA) called for ‘innovative approaches to leverage additional resources into Social Housing through community, private sector and other partnerships’ (Commonwealth of Australia, 2003: p. 4), much commercialisation bypassed traditional non-profits altogether. New non-profit companies established by governments, such as Brisbane Housing Company, resemble housing non-profits in organisational structure but have often adopted more entrepreneurial business models.

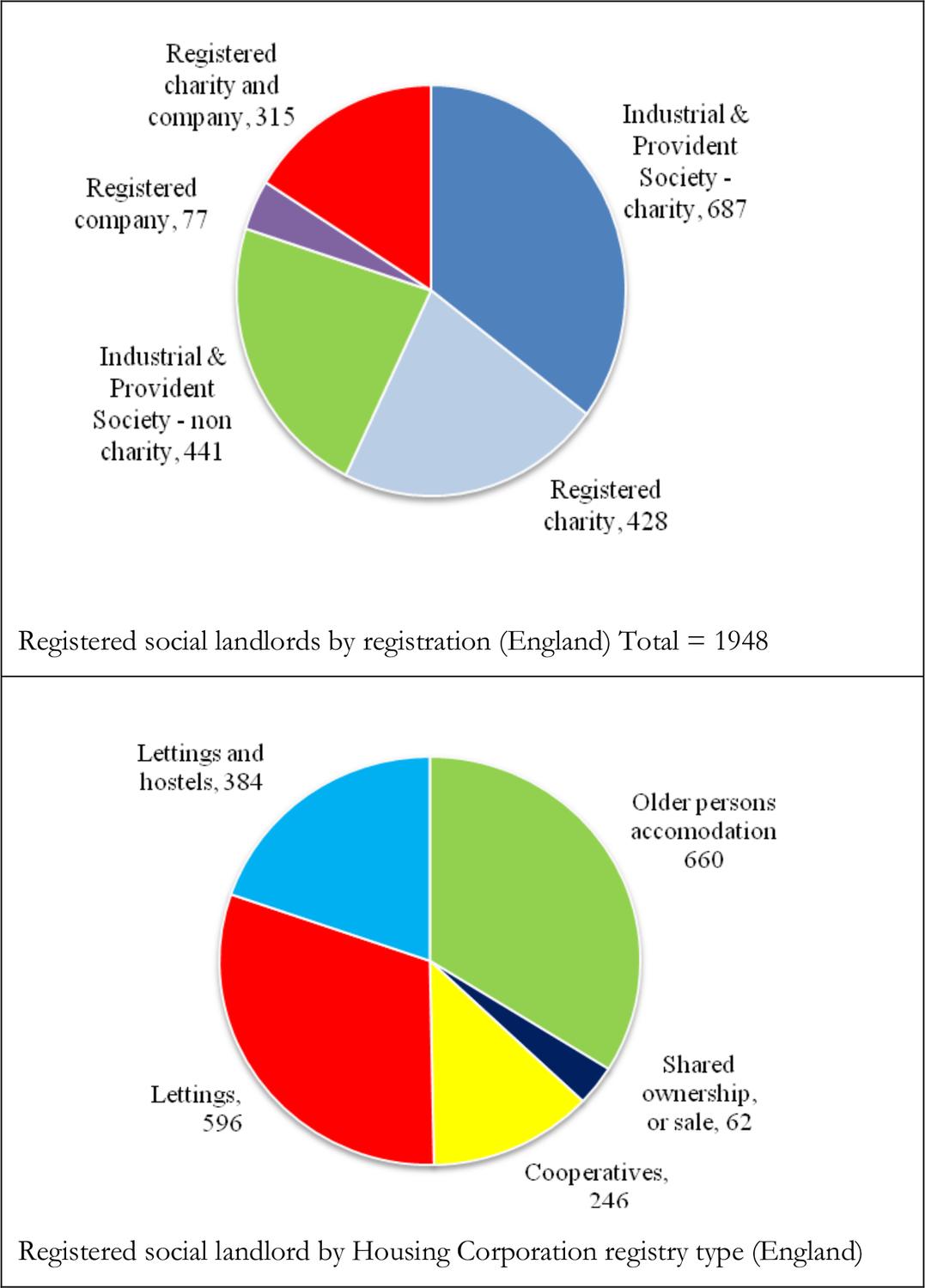

More detailed analysis is available for England’s non-profit sector due to the rich data collected by the Housing Corporation. Figure 24 shows organisational diversity in 2005: 108

Figure 24: England’s housing associations, 2005

Source: Data from Housing Corporation (2006: p. 33) as at 31st March 2005 109

The most popular legal form in Figure 24 is as an Industrial and Provident Society (58%) followed by registration under the Companies Act (20%). Only three quarters of the 1948 registered social landlords have charitable status, with the remainder presumably paying tax on profits. Just under 67% of organisations managed fewer than 250 properties with 92% managing fewer than 5,000 properties. Using Housing Corporation categories, there are a number of niche organisations: 34% cater for older people, 20% provide some hostel accommodation and 3% assist low to moderate income earners to buy affordable homes. The figure for housing cooperatives (13%) is higher than expected given their relatively low profile. During the previous twelve months, there had been a modest net decrease of 36 housing associations, or 1.8% of the total (Housing Corporation, 2006: p. 34).

Australian housing non-profit statistics are in short supply, hard to benchmark across states and problematic to compare with the larger, more mature English housing associations. A survey in 2002–3 documented 1229 CHSA funded community housing organisations in Australia, with most in Queensland (28%), followed by Western Australia, Victoria and NSW (16%). The average dwellings per organisation ranged from under six in the Northern Territory to around 48 in NSW and the ACT although this data excludes organisations unfunded by CHSA which would reduce average size (Bissett and Milligan, 2004: p. 16). The difference in size distribution of housing non-profits between England and Australia is due to a tail-end of very small organisations in Australia and the absence of very large organisations with over 2500 properties. However, Australia may be more comparable with other countries: there are fewer differences if NSW (population 6.7m, 2006 Census) is compared to Ireland (population 4.2m, 2006 official data). Both states have 10% of their social housing managed by non-profits and average organisation size is 33 properties in NSW compared to 35–40 in Ireland (NSW Department of Housing, 2007; Mullins et al., 2003).

Is the diversity of non-profit housing providers described in this chapter so great it renders meaningless an international comparison of organisational types? From Figure 23, there is evidence of policy convergence, for example the diffusion of stock transfer ideas from England to Australia and the expansion of affordable housing through a 110favoured commercialised housing association model rather than tenant cooperatives. The recent NSW draft plan acknowledges ‘Europe, North America and the UK … [and] other Australian states and territories are considering a broader role for community housing … [and the NSW policy] reflects these national and international directions’ (NSW Department of Housing, 2007: p. 6). The state will grow the non-profit sector by an expansion of ‘a limited number of providers – those who are high performing’ (NSW Department of Housing, 2007: p. 5). These are the ‘growth housing providers’ (Bissett and Milligan, 2004: p. 50), comparable in relative size to the ‘super league’ which Mullins and Murie (2006: p. 194) observed in England from the 1990s. In Australia these growth providers are set to take an increasing proportion of properties controlled by the sector. The next section looks at how organisational theory can shed light on these changes.

Understanding boundaries

In this chapter, there is an assumption that there is validity in the social construct of a ‘housing non-profit sector’ and that it has determinable boundaries with other sectors into which housing organisations could be grouped. Constructivist writers argue that housing sector definitions will be deeply embedded in power relationships such as the emergence of housing managers as a profession, the expansion of university and private sector housing research and the political legitimation of the move to market-based housing systems (Jacobs et al., 2004). The housing non-profit sector can also be seen through the perspective of organisational theory which is dynamic, moving from Weber’s rational-bureaucratic ‘iron cage’ through the 1960s behavioural science vogue to contemporary ‘new institutionalism’ (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). New institutional writers have brought back the importance of organisations as it is through them that broader political and global economic forces are mediated (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2004; Ingram and Silverman, 2002). However, unlike with Weber, they place organisations in a broader, more complex and connected setting: ‘the core institutionalist contribution is to see environments and organisational settings as highly interpenetrated’ (Jefferson and Meyer, 1991: p. 205).

In organisational and network theory, the term ‘sector’ has given way to the more nuanced ‘organisational field’, described as comprising ‘those 111organisations that, in the aggregate, constitute a recognisable area of institutional life’ (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983: p. 148). Sectors can be defined by economic or social outputs, whereas organisational fields are understood by the strength of networks and the forces of institutionalisation. For example, a ‘housing supply sector’ could be defined, comprising public, private and non-profit organisations that build homes. However, the lack of networks sharing information and an absence of common professional associations spanning private and social house builders suggest the ‘housing supply sector’ does not constitute an organisational field. Sectors are often defined by government statistics and organisations are either ‘in’ or ‘out’: fields can be more or less institutionalised depending on the extent of interaction and information flow between organisations, and the awareness of organisations and the media that the organisations are involved in a common set of activities. Common regulation, funding, legal structures and professional accreditation can all contribute towards building organisational fields in housing (Mullins, 2002).

In England, there have been moves to define a broader ‘social housing field’ encompassing the variety of housing associations, ALMOs etc. shown in Figure 23 together with the remaining public housing providers and occasional private companies receiving subsidies. English government policy has defined a ‘social housing sector’ by legislation, data collection, deliberate network support, and careful language management such as the use of ‘social housing’ and building local ‘partnerships’ (ODPM, 2005). Mullins (2001a) agrees that there is an emerging social housing field in England but notes that it is relatively weak, whereas the subfield comprising housing associations has become stronger and more institutionalised. Therefore, in England ‘cross-sectoral policy communities and networks operate best at subsectoral, rather than at sectoral, level’ (Mullins et al., 2001a: p. 610).

In contrast, Australia does not have a well defined social housing sector or social housing field. There are modest signs of change, for example a Housing Institute founded in 2001 describes itself as ‘the professional association of people working and volunteering in the multi-disciplinary social housing industry’ (Australasian Housing Institute, 2006: p. 6). Broader field definition is not helped by legislative fragmentation and lack of staff transfer between the public and non-profit sector. Greater 112institutionalisation has been occurring at the field (or subfield) of Australian community housing with the emergence of peak bodies: the NSW Federation of Housing Associations in 1993 and the Community Housing Federation of Australia in 1996. National Community Housing Conferences were first held in 1990 and 1994 (Bissett and Milligan, 2004), and since 2004 there have been calls for a National Affordable Housing Agreement to be delivered through the community housing and private sectors (National Affordable Housing Forum, 2006).

If the previous section of this chapter gave a snapshot of the diversity of non-profit housing providers, the idea of organisational fields has made the process dynamic by highlighting how boundary definition is deeply contested, and changes over time and location (Mullins and Rhodes, 2007). This complexity is a strong argument in favour of a typological approach which will be discussed after first addressing the issue of whether non-profit organisations are become more or less similar in structure and delivery systems.

Same or different?

An important tenet of new institutional theory is ‘institutional isomorphism’, the tendency of organisations operating in the same organisational field to adopt similar business practices, and not just for efficiency benefits: ‘organisations compete not just for resources and customers, but for political power and institutional legitimacy, for social as well as economic fitness’ (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). Isomorphism will only take place once an organisational field has become sufficiently established, therefore the arguments about field definition in the last section are crucial to understanding which organisations could be expected to become more similar, and when.

The three mechanisms contributing to isomorphism identified by DiMaggio and Powell (1983) are shown in Figure 25, illustrated with examples from the non-profit housing sector. Countries such as England and Australia have a regulated non-profit housing sector and coercive isomorphism is important, more so in Australia where there is greater reliance on public funding. Mimetic isomorphism is encouraged in Australia where state governments use limited resources to develop a small number of well publicised demonstration projects. 113

Figure 25: Mechanisms of isomorphism for non-profit organisations

| Description | Examples | |

| Coercive | Dependency on resources (such as funding) from a small number of actors prompts organisations to behave in a way seen as appropriate by the resource provider. Hence the need to seek legitimacy. Coercive isomorphism can be both by force (e.g., legal sanctions) and by persuasion. | State funding will require organisations to have skilled board members, submit regulatory returns etc. In England a non-performing housing association can be taken over by the Housing Corporation. Bank lenders will require management accounts, a financial controller, outside auditors etc. |

| Mimetic | Emergence of organisations seen to be leaders in their field which other organisations seek to emulate. Role model organisations are particularly valued at times of uncertainty and sectoral change (Jefferson and Meyer, 1991). Knowledge can be transmitted through staff movements. | Bridge Housing in California and Brisbane Housing Company in Australia are seen to be ‘leaders’. Executives of both organisations are asked to present at housing conferences. Through the Internet, other organisations can mimic their mission statements, board structures and tenancy management policies. |

| Normative | Common set of assumptions established through professional training, career structure and networking. It is important to know how complete the ‘professionalisation process’ is within a field (i.e. proportion of total staff who belong to a professional institute). | Professional associations, university housing researchers (including AHURI in Australia), conferences, job secondments and trade magazines are all important. Staff have moved into affordable housing (including as non-exec directors) from the private sector, bringing a more commercial/less welfare outlook. |

There are limits to isomorphism, both in theory and practice. With coercive isomorphism, organisations are not simply passive actors unquestioningly absorbing influences from the wider environment. For example, Greer and Hoggett (1999) described a housing association that manipulated its regulatory returns to avoid Housing Corporation demands to extend geographical coverage of its housing provision from 114its core inner-city base. In a study on the introduction of private sector management techniques to American non-profit organisations, Lindenberg (2001) found Michael Porter’s ‘five forces’ business model was thought useful by senior managers but was rejected in the organisation by staff who considered they worked in a social environment. Similarly, when non-profits produce housing data, ‘performance indicators have an important ritual quality. Their reverential status implies that the practice is to a large extent a symbolic one’ (Jacobs and Manzi, 2000: p. 90). Hence organisations may appear to be isomorphing, but appearances can be deceptive. Erlingsdóttir and Lindberg (2005) coined the term isonymism when organisations use the same names but practices remain different. Coercive isomorphism may lead to similar organisational practice but on a superficial level, much weaker than Weber’s ‘iron cage’ of control (Paton, 2003).

Mimetic and normative isomorphism rely on networks to transmit ideas about preferred business practice. Network forms of governance are now common in housing, unlike the hierarchical relationships in the past between governments and housing providers based on a principal/agent relationship with an active/passive power balance (Reid, 1995; Rhodes, 1997; van Bortel and Elsinga, 2007). In England from the late 1980s there was a move away from both local authorities and publicly funded housing associations acting in the integrated roles of direct provider, distributer and manager of social housing: ‘the assumption that all of these roles automatically belong together had given way to a widening range of diverse organisational arrangements’ (Mullins et al., 2001a: p. 601). Partnerships and collaboration were actively encouraged in English social housing by outsourcing to housing associations, compulsory competitive tendering of council services and the involvement of service users through the 1991 Citizen’s Charter and the 1999 Tenant’s Compact (Mullins and Rhodes, 2007). Organisational responses to this more networked environment in England have included mergers, shared services, diversification into wider social service provision and partnership agreements with local councils.

It remains unclear whether there is a causal relationship between stronger non-profit housing networks and a trend to organisational isomorphism. Networks have developed further and faster in England than Australia over the last two decades whereas English housing 115associations have probably become more diverse, and Australian more similar. One explanation is that, despite the increased importance (and knowledge of) networks, they do not fully explain organisational relationships. Reid (1995) identified three types of coordination within a policy field: hierarchies involving clear roles and responsibilities, markets based on competition, and networks of individuals and organisations acting more in cooperation than competition. The three approaches are not mutually exclusive and exist in simultaneously in social housing (Mullins et al., 2001a). For example, the relationship between an English housing association and the Housing Corporation is hierarchical; the association may compete in the market for land yet be part of a network sharing news of best practice tenancy management. Whichever technique works best will be used to achieve particular outcomes. Networks have become part of the governance tool-kit, not replaced it.

In England, housing associations have always been diverse, but their heterogeneity has increased since the early 1990s (Mullins et al., 2001a). Housing associations diversified their social mission into building communities, not just homes, and by raising commercial finance they moved to a new economic mission. Both trends favoured employing staff with general rather than housing skills which weakened the professions, reducing normative isomorphism. The new ‘super league’ of very large associations with over 10,000 properties contrasts with traditional community non-profits hence ‘the trend towards even bigger housing associations driven by development ambitions is diluting commitment by community involvement that was the hallmark of good management. Many smaller organisations perform better on this front, but funding drifts to large scale organisations’ (Rogers, 2005: p. 11). The fear is that professionalisation of larger non-profits, coupled with complex group structures, may lead to them becoming more remote to the communities they serve.

The emergence of the English non-profit ‘super league’ and the Australian ‘growth sector’ raises an interesting question: do organisations such as these in a number of counties form part of a new housing subfield within which individual non-profits will start isomorphing towards a similar organisational type? There is growing evidence of organisational learning, policy transfer and mimetic isomorphism through international ‘ideal type’ affordable housing companies such as 116Bridge Housing in California. New thinking on housing spreads through networks between countries in a similar way to within countries. Comparative housing research is popular, and often didactic: a survey published in Australia contrasting financing affordable housing noted: ‘Australian policy debates could also benefit from the much broader discussions in the UK concerning key worker and employer provided affordable housing … both countries might usefully look to the United States in relation to use of tax incentives to encourage the greater involvement of institutional investors in affordable housing provision’ (Berry et al., 2004: p. 86).

International housing networks are helped by the Internet which allows researchers and policy makers to track success with overseas housing companies and policy innovations. Housing academics form a relatively strong international network transferring ideas through conferences and overseas study: the three key-note speakers at the 2005 National Affordable Housing Conference in Sydney were Christine Whitehead from the UK, Dr Michael Stegman formerly of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, and Carol Galante of Bridge Housing in California. Network connectivity is strongest where countries are close together geographically, for example the European Network of Housing Researchers and CECODHAS, the European Liaison Committee for Social Housing (Czischke, 2007). Network limitations are from the domestic focus of most professional associations and the framing of housing policy at country level, even in the European Union. If a new housing subfield is emerging, then to date it is relatively weak.

Typologies

The possible emergence of a ‘super league’ of growth non-profits described in the previous section reinforces the need for a clear framework in which to place and compare individual housing providers which may be located in different countries. Typologies can be useful tools for classifying related items, particularly those existing in complex and fast changing environments. They can help correct misconceptions and organise knowledge by defining organisational field and subfield boundaries (Tiryakian, 1968; Allmendinger, 2002). Typologies are popular in the social sciences, and are used particularly by organisational and management theorists (e.g. Mintzberg, 1979; Porter, 1980). Rather 117than acting as passive classification systems, typologies assist inductive theory building (Doty and Glick, 1994). With their focus on ideal type organisations, they can allow researchers to identify organisational forms that may be more effective than any currently existing.

Given the strengths of a typological approach, it has been used surprisingly few times to map the non-profit housing sector and studies have concentrated on a single or neighbouring pair of countries. The most comprehensive research to date has suggested size, location, origins and service provision as ‘key dimensions for understanding the different subgroups’ in Ireland (Mullins et al., 2003: p. 87). The qualitative study used the Delphi Method, but with no mapping of individual organisations within categories, nor suggestion of how ‘size’ should be delineated. In earlier research using similar methods for English housing associations Mullins and Riseborough (2000) defined organisations as small with under 250 properties, medium with 250–5000, and large with over 5,000. Newcombe (2000) defined medium as 250–2500 properties. For the Housing Corporation, small housing associations manage up to 250 properties and very large over 10,000. However, the main typology used by the Housing Corporation is not based on size but on the distinction between ‘traditional’ and ‘stock transfer’ associations (Housing Corporation, 2007).

Figure 26 summarises six possible typologies which could be used to classify non-profit housing organisations. Descriptors [1] to [4] are from the study by Mullins et al. (2003: pp. 84–86) and category [5] is based on the approach used in Figure 23 of this chapter. The least helpful descriptors in Figure 26 are [2], [3] and [4] as they are tied to particular factors which help differentiate organisations in Ireland. They allow an analytical categorisation of organisations by geography, history etc. but were not intended to be a comprehensive typology. Descriptor [1] is a powerful tool to categorise organisations but there are major national variations: a large housing non-profit in England or the Netherlands might have over 10,000 properties, in Scotland or Northern Ireland over 1000, and in Australia or the Republic of Ireland over 250. Traditional descriptors such as legal status [5] are popular but do not capture the organisation’s values, nor help identify sector innovators. Therefore, descriptor [6] has been adopted for further testing: 118

Figure 26: Possible non-profit housing typologies

| Criterion | Basis | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| [1] Size |

Rank organisations by properties held, e.g., up to 250; 250–5,000; over 5000 | [a] Straightforward, with data easy to obtain [b] Used before in studies and familiar to researchers |

[a] Typical organisation size varies markedly between countries [b] Size not a good descriptor of how organisations function |

| [2] Location |

Based on urban or rural location | [a] Worked in survey of Irish housing non-profits | [a] Hard to define urban and rural. Does urban include suburban? [b] Fast growth organisations tend to be urban based |

| [3] Origins and formation |

Date of formation, possibly grouped by decade | [a] Worked in survey of Irish housing nonprofits [b] Data easy to obtain |

[a] Not possible to compare across countries as timing different [b] Only meaningful if linked to other attribute, eg ethos |

| [4] Service provision |

Differentiate between housing and mixed service providers | [a] Worked in survey of Irish housing nonprofits [b] Captures important diversification trend |

[a] Country specific, e.g., would work for Ireland but not for England. [b] Hard to measure the degree of diversification |

| [5] Organisation form |

Similar to Figure 23, e.g., cooperative, housing association, ALMOs etc. | [a] Straightforward approach based on legal form [b] Used by England’s Housing Corporation |

[a] Too much based on national legislation and regulation [b] Legal structure gives no clues about values, functioning etc. |

| [6] Ethos and values |

Community, state or business values – see Figure 27 | [a] Designed to work on trans-national case studies [b] Better at capturing growth sector of market |

[a] Based on qualitative ideas so hard to classify organisations [b] Not yet tested by research thus still a conceptual model 119 |

A typology based more on ethos than organisational characteristics was proposed by Gruis and Nieboer (2004) for a national social housing system categorisation along a spectrum from strategic/market-orientated to operational/task-orientated. This was later developed into a market-orientated versus government-regulation split for the management of social housing assets (Gruis and Nieboer, 2007). Whilst their model is helpful in supporting a qualitative, flexible approach, the typology characteristics proposed in Figure 27 are based on a tripartite model of business, public and third (i.e. non-profit) sector popularised by the Johns Hopkins Comparative Non-profit Sector Project (Salamon, 2002; Salamon et al., 2003). The categories in Figure 27 are orientated towards ethos not organisational form.

Figure 27: Typology characteristics based on ethos and values

| Community-centric | State-centric | Business-centric | |

| Values | Voluntary Local Flexible Participatory |

Equitable Bureaucratic Fixed Consultative |

Entrepreneurial Strategic Flexible Customer-driven |

| History | Normally longer-established, social needs-driven in specific local area | Often set up by the state, possibly stock transfer from public housing | More recently established with clear economic and social mission |

| Finances | Reliant on the state for ongoing funding using supply and demand levers. May receive donations | Often set up with public funding then potentially becoming more self-financing from income | Often cross-subsidy of market/social activities: finances are ‘cutting edge’. Debt financing common |

| Scale | Often small and local, sometimes part of larger group. Slower growth | Often large if based on stock transfers or arms length management. | Varies, sometimes only a demonstration project. Normally fast growing |

| Example shown in Figure 29 | Longer established non-profit, e.g., an English housing association (A) | Stock transfer of public housing to a non-profit organisation (B) | Non-profit with initial public funding then uses market techniques (C) 120 |

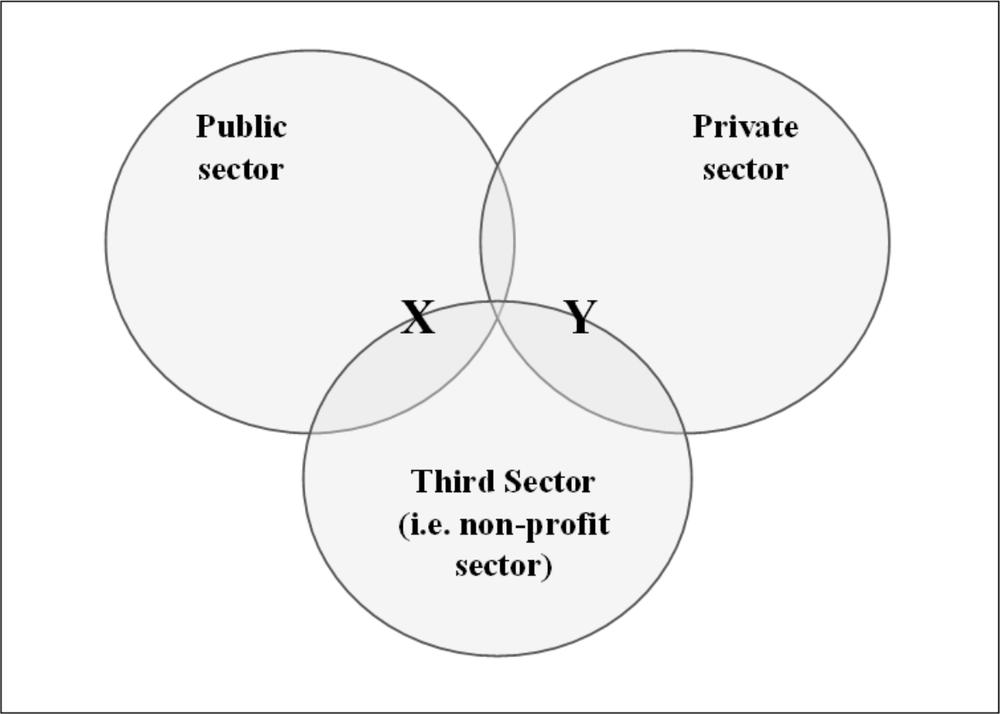

The typology developed in Figure 27 does not capture the full complexity of the housing non-profit sector with many organisations having a mix of community, state and business attributes. Sector boundaries are becoming less well defined as business becomes more socially responsible and governments and non-profits more commercialised. A conceptual solution, shown below in Figure 28, was developed by Mullins and Riseborough (2000) to show the transformation of English housing associations from 1974–1989 (marked X) to their position after 1989 (marked Y). This helps capture the interrelatedness between the public, private and third sectors and shows change over time:

Figure 28: Locating English housing associations

Source: Mullins and Riseborough (2000: p. 5)

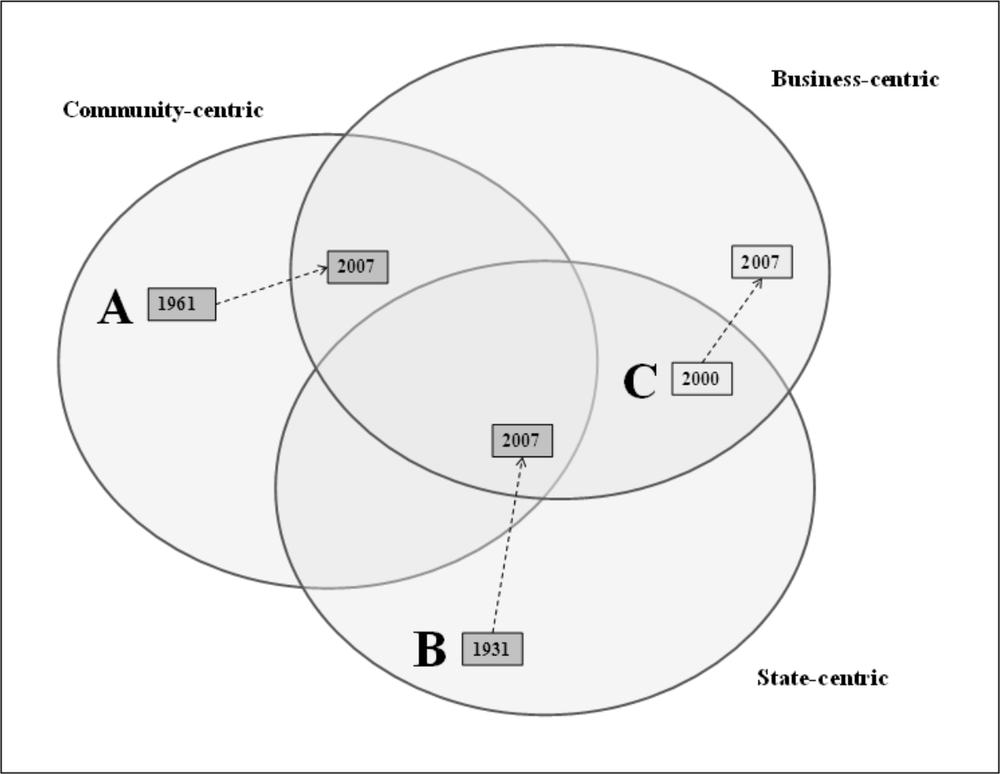

The approach shown in Figure 28 provided the conceptual basis for the proposed typological model in Figure 29. Deliberately, there is greater overlap in Figure 29 reflecting the recent convergence of business, public and third sector organisational values: 121

Figure 29: Proposed non-profit housing typology, with examples

The thinking behind Figure 29 is that whilst an organisation can be summarised as representing a single typological category, it may still have lesser characteristics from other categories. For example, the traditional housing association (A) has moved from being a purely community organisation in 1961 towards adopting business practices but remaining, overall, community-centric. This is shown by it being closer to the centre of the circle representing the ‘community-centric’ typology than to the centre of the circles representing ‘business-centric’ or ‘state-centric’. Stock-transfer company (B) has changed from being purely state-centric in 1931 when it was in the public sector to a position in 2007 where, whilst its dominant values are state-centric, it has some community values as tenants sit on the board and business characteristics having raised external bank finance. Non-profit organisation (C) was established by the state but has moved to cross-subsidising market rate and affordable housing. 122

The Venn diagram allows a representation of the rate at which an organisation has changed over time (shown by the length of the dotted arrow) and can also be used to highlight whether organisations are developing in a common direction, for example whether they are all becoming more business-centric. However, at this stage the typology is a tentative hypothesis which needs to be tested by case study research and practitioner discussions. It has been designed as a framework for debate rather than a definitive solution, thereby avoiding the problem where ‘the very success and acceptance of a typological classification may … freeze the level of explanation’ (Tiryakian, 1968: p. 179).

Conclusions

The key to building a sustainable non-profit affordable housing sector is to ensure that the organisations in that sector are robustly structured, well managed and have proper governance. Organisational and network theories are important tools in understanding the changes currently taking place, although they often tend to be overlooked in housing policy. On the one hand, there is an increasing diversity of organisational types, affordable housing delivery models, and management value systems. On the other, the commercial and partnership approach is being replicated in a number of countries. A proposal advanced in this chapter is for a convergence amongst a ‘super league’ of growth affordable housing providers in a number of countries which may mark the emergence of a new housing subfield. This subfield, supported by rich global knowledge networks, has the potential once it becomes more institutionalised to lead to an isomorphing of organisational structure. This may be a necessary precursor to bringing in new forms of institutional investment which, in the case of Australia, are probably necessary to sustain the sector’s independence from government.

There remains considerable debate over where field and subfield boundaries should be drawn in the housing sector, and complexity is increasing as new forms of governance make the boundaries more permeable. Despite having traditional legal structures, non-profits are adapting to a changing environment by moving from hierarchical to networked structures and mixing community, public and business values. A tried and tested way to observe these changes is through a typological lens, particularly one that can accommodate both the interrelatedness of 123the different values systems and the dynamics of change over time. New institutionalism rightly puts organisations back to the centre of the housing debate as it is only through their capabilities that a sustainable non-profit affordable housing sector will be built.

Notes

This chapter is based on a paper Same or different? Towards a typology of non-profit housing organisations presented at the 2nd Australasian Housing Researchers Conference, Brisbane Australia, 20th–22nd June 2007.

124

References

Allmendinger, P. (2002) ‘Towards a post-positivist typology of planning theory.’ Planning Theory. 1(1). March 2002. pp. 77–99.

Australasian Housing Institute (2006) Supporting our profession: business plan 2006–2009. Cobargo, NSW: Australasian Housing Institute.

Australian Government (2008a) Making housing affordable again. Canberra: Australian Government.

Australian Government (2008b) National rental affordability scheme: technical discussion paper. Canberra: Australian Government.

Barbato, C., Clough, R., Farrar, A. and Phibbs, P. (2003) Stakeholder requirements for enabling regulatory arrangements for community housing in Australia. Final Report. Sydney: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), Sydney Research Centre.

Berry, M., Whitehead, C., Williams, P. and Yates, J. (2004) Financing affordable housing: a critical comparative review of the United Kingdom and Australia. Sydney: AHURI Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling and Sydney Research Centre.

Berry, M., Whitehead, C. and Yates, J. (2006) ‘Involving the private sector in affordable housing provision: can Australia learn from the United Kingdom?’ Urban Policy and Research. 24(3). September 2006. pp. 307–323.

Bissett, H. and Milligan, V. (2004) Risk management in community housing: managing the challenges posed by growth in the provision of affordable housing. Sydney: National Community Housing Forum.

Clough, R., Barbato, C., Farrar, A. and Phibbs, P. (2002) Stakeholder requirements for enabling regulatory arrangements for community housing in Australia. Positioning Paper. Sydney: AHURI Sydney Research Centre.

Commonwealth of Australia (2003) 2003 Commonwealth state housing agreement. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Community Housing Federation of Australia (CHFA) (2001) Community housing: building on success. Policy directions for community housing in Australia. Canberra: Community Housing Federation of Australia (CHFA).

Cope, H. F. (1999) Housing associations: the policy and practice of registered social landlords. Houndsmill, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. 125

Czischke, D. (2007) ‘A policy network perspective on social housing provision in the European Union: the case of CECODHAS.’ Housing, Theory and Society. 24(1). March 2007. pp. 63–87.

DiMaggio, P. J. and Powell, W. W. (1983) ‘The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organisational fields.’ American Sociological Review. 48(2): pp. 147–160.

Doty, D. H. and Glick, W. H. (1994) ‘Typologies as a unique form of theory building: toward improved understanding and modelling.’ Academy of Management Review. 19(2): pp. 230–251.

Erlingsdóttir, G. and Lindberg, K. (2005). ‘Isomorphism, isopraxism, and isonymism: complementary or competing processes?’ in B. Czarniawska and G. Sévon (eds.) How ideas, objects and practices travel in the global economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1999) Social foundations of postindustrial economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Government of Western Australia (2007) Premier announces multi-million dollar package to boost housing affordability. Media statement dated 1st May 2007. Available at website of Government of Western Australia: www.mediastatements.wa.gov.au.

Greer, A. and Hoggett, P. (1999) ‘Public policies, private strategies and local public spending bodies.’ Public Administration. 77(2): pp. 235–256.

Gruis, V. and Nieboer, N. (eds.) (2004) Asset management in the social rented sector, policy and practice in Europe and Australia. Dortrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Gruis, V. and Nieboer, N. (2007) ‘Government regulation and market orientation in the management of social housing assets: limitations and opportunities for European and Australian landlords.’ European Journal of Housing Policy. 7(1): pp. 45–62.

Hills, J. (2007) Ends and means: the future roles of social housing in England. London: London School of Economics – Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion.

Housing Corporation (2006) Our stories: Housing Corporation annual report and accounts 2005–06. London: The Housing Corporation.

Housing Corporation (2007) Global accounts of housing associations 2006. London: The Housing Corporation.

Housing Corporation (2008) Web site, www.housingcorp.gov.uk (consulted 20th July 2008). 126

Ingram, P. and Silverman, B. S. (eds.) (2002) The new institutionalism in strategic management. Advances in Strategic Management. Volume 19. Amsterdam: JAI.

Jacobs, K., Kemeny, J. and Manzi, T. (eds.) (2004) Social constructionism in housing research. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Jacobs, K. and Manzi, T. (2000) ‘Performance indicators and social constructivism: conflict and control in housing management.’ Critical Social Policy. 20(1): pp. 85–103.

Jefferson, R. L. and Meyer, J. W. (1991). ‘The public order and the construction of formal organization,’ in W. W. Powell and P. J. DiMaggio (eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 204–231.

Light, P. C. (2002) Pathways to non-profit excellence. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Lindenberg, M. (2001) ‘Are we at the cutting edge or the blunt edge?’ Non-profit Management & Leadership. 11(3): pp. 247–271.

Malpass, P. (2000) Housing associations and housing policy: a historical perspective. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Milligan, V. (2003) How different?: comparing housing policies and housing affordability consequences for low income households in Australia and the Netherlands. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Milligan, V., Phibbs, P., Fagan, K. and Gurran, N. (2004) A practical framework for expanding affordable housing services in Australia: learning from experience. Sydney: AHURI Sydney Research Centre.

Mintzberg, H. (1979) The structuring of organizations: a synthesis of the research. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Mullins, D. (2002) Organisational fields: towards a framework for comparative analysis of non-profit organisations in social housing systems. Paper presented at ENHR conference in Vienna, 1st–5th July 2002. Workshop on Institutional and Organisational Change in Social Housing Organisations in Europe. Unpublished. Copy obtained from author.

Mullins, D. and Murie, A. (2006) Housing policy in the UK. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mullins, D., Reid, B. and Walker, R. M. (2001a) ‘Modernization and change in social housing: the case for an organisational perspective.’ Public Administration. 79(3): pp. 599–623.

Mullins, D. and Rhodes, M. L. (2007) ‘Special issue on network theory and social housing.’ Housing, Theory and Society. 24(1): pp. 1–13. 127

Mullins, D., Rhodes, M. L. and Williamson, A. (2001b) ‘Organizational fields and third sector housing in Ireland, North and South.’ Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Non-profit Organizations. 12(3): pp. 257–278.

Mullins, D., Rhodes, M. L. and Williamson, A. (2003) Non-profit housing organisations in Ireland, North and South: changing forms and challenging futures. Belfast: The Northern Ireland Housing Executive.

Mullins, D. and Riseborough, M. (2000) What are housing associations becoming? Birmingham: School of Public Policy, University of Birmingham.

National Affordable Housing Forum (2006) A summary of the forum: achieving a new national affordable housing agreement: 24–25 July, Old Parliament House, Canberra. Canberra: National Community Housing Forum.

National Community Housing Forum (2004) National strategic framework for community housing 2004–2008 and community housing snapshot. Sydney: National Community Housing Forum.

Newcombe, R. (2000). ‘Strategies for medium-sized housing associations,’ in S. Monk and C. Whitehead (eds.) Restructuring social housing systems: from social to affordable housing. York: York Publishing Services, pp. 160–167.

NSW Department of Housing (2006) Stock transfer program: fact sheet, September 2006. Ashfield, Sydney: NSW Department of Housing.

NSW Department of Housing (2007) NSW planning for the future: community housing. Five year strategy for growth and sustainability 2007–2012, consultation draft. Ashfield, Sydney: NSW Department of Housing.

Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM) (2005) Sustainable communities: people, places and prosperity: a five year plan from the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. Norwich: HMSO.

Paton, R. (2003) Managing and measuring social enterprises. London: Sage Publications.

Pollitt, C. and Bouckaert, G. (2004) Public management reform: a comparative analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Porter, M. E. (1980) Competitive strategy: techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York: Free Press.

Powell, W. W. and DiMaggio, P. J. (eds.) (1991) The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 128

Reid, B. (1995) ‘Inter-organisational networks and the delivery of social housing.’ Housing Studies. 10(2). September 2001. pp. 133–149.

Rhodes, M. L. (2007) ‘Strategic choice in the Irish housing system: taming complexity.’ Housing, Theory and Society. 24(1): pp. 14–31.

Rhodes, R. A. W. (1997) Understanding governance: policy networks, governance, reflexivity, and accountability. Buckingham, Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Rogers, R. (2005) Towards a strong urban renaissance: an independent report by members of the Urban Task Force. London: Urban Task Force.

St. George Community Housing (2007) Website, www.sgch.com.au (consulted 12th May 2007).

Salamon, L. M. (ed.) (2002) The State of Non-profit America. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Salamon, L. M., Sokolowski, S. W. and List, R. (2003) Global civil society: an overview. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Institute for Policy Studies, Center for Civil Society Studies.

State Government of Victoria (2007) Record $510 million for public and social housing. Department of Human Services, press release dated 2nd May 2007. Available at the website of the State Government of Victoria: www.dhs.vic.gov.

Tiryakian, E. A. (1968). ‘Typologies,’ in D. L. Sills (ed.) International encyclopaedia of the social sciences. New York: Macmillan. pp. 177–186.

van Bortel, G. and Elsinga, M. (2007) ‘A network perspective on the organization of social housing in the Netherlands: the case of urban renewal in The Hague.’ Housing, Theory and Society. 24(1): pp. 32–48.

Wood, M. (2003) ‘A balancing act? Tenure diversification in Australia and the UK.’ Urban Policy and Research. 21(1): pp. 45–56.