4

Outsourcing of elder care services in Sweden: effects on work environment and political legitimacy

In Sweden, as in other parts of the world, a number of market-inspired institutional and organisational changes in welfare services are taking place.1 These developments are often summarised in the concept New Public Management (NPM), and involve shifts in both the way services and work are organised (praxis) and represented (discourse) (Hood 1998; Pollitt & Boucaert 2000). NPM has been compared to a ‘shopping basket’ in which the important ingredients are competition, contracts, freedom of choice and cost control (Pollitt 1995); and Swedish elder care2 is definitely affected by these trends.

Debate about the impact of NPM in Swedish elder care has focused on quality and efficiency: do these policies improve the quality of care and contain costs? We seek to raise two other issues central to the provision of elder care as a welfare service: working conditions and democratic control. This approach highlights the perspectives of careworkers (both as employees and citizens) and the roles of politicians (both as public employers and decision-makers) in the evolution of elder care in Sweden.

Our approach is informed by a theoretical perspective that recognises differences in the goals and dynamics of public and private

82organisations. Public employers do not own their organisations. They operate on behalf of vote-holding citizens who collectively own the buildings and other assets used to provide services. In Sweden, many of those entitled to vote are also public employees in various types of welfare services. Welfare services personnel, then, participate in the election of their own employers. This means that the power of public employers is democratically delegated and, therefore, conditional. Private employers, by contrast, operate on behalf of shareholders within the framework of private ownership rights. Thus, private employers who obtain contracts to provide welfare services must serve two masters: on the one hand, they serve the politicians who steer their operations to meet social targets on behalf of citizens, and on the other, they serve their shareholders, for whom they are required to pursue financial profit.

The institutional history of the public sector as an employer is, no doubt, a marginal and rare topic in social and historical research in Sweden and elsewhere (Kolberg 1991; Gustafsson 2000). There has been, for instance, very limited interest in the fact that municipal and county council politicians are the employers of almost a quarter of the total Swedish labour force, among them the vast majority of the elder care personnel. This has probably contributed to the lack of theoretical perspectives that could further an analysis of differences in the socio-political roles of public and private employers.

Inspired by Michael Mann (2006, p. 59), we raise the issue of conceiving elder care as a part of the local state’s infrastructural power and we examine perspectives that, to date, have not received much attention in either public discourse or research. Our research foci have evolved through the merging of three perspectives that are usually treated in theoretical and empirical isolation from each other. This article presents a broad empirical investigation into the outsourcing of publicly financed elder care services in Sweden. Specifically, we consider:

- how the careworkers in both private and public elder care in Sweden assess their work environment; 83

- how the careworkers in both private and public elder care experience the influence of local politicians;

- and whether, in turn, these two aspects have any connection with the careworkers’ opinions for or against continued outsourcing of elder care.

The context of the study

Care of elderly people occupies a central position within the Swedish welfare model. In Sweden, unlike many countries of continental Europe, adult children have no legal obligation to provide care or financial support for their parents (Millar & Warman 1996). Formal responsibility lies with municipal governments, which have a statutory duty to meet the needs of elderly people. From an international perspective, Swedish (and in fact all Scandinavian) elder care is usually labelled ‘universal’ and is characterised by comprehensive, high quality services. The same services are directed towards, and used by, all social groups (Sipilä 1997; Anttonen 2002). Services are almost entirely publicly financed: about 85 per cent of the cost for elder care services is covered by municipal taxes, 10 per cent by national taxes (state grants) and only 5 per cent by user fees (National Board of Health and Welfare 2007a). Until recently services were also almost entirely publicly provided. During the postwar expansion of tax-financed elder care, the welfare state not only acted as the financer of welfare services, but also as employer of all the personnel.

A high degree of autonomy of the local vis-à-vis central government (including the right to levy taxes locally) is typical in Scandinavian municipalities. Within the limits prescribed by legislation, locally elected politicians set income tax rates and decide on budgets, and thus also decide on the priority given to elder care in relation to other services. More specifically, they also decide on local guidelines for the organisation of elder care work. Not surprisingly, there are large municipal differences in the coverage and organisation of elder 84care. Using a concept from Kröger (1997), it has been argued that when it comes to care of the elderly it is more appropriate to talk of many different ‘welfare municipalities’ than one uniform welfare state (Trydegård 2000).

Sweden is a big welfare spender (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2005), but in spite of the rising proportion of older people in the population, the amount of public funds allocated to elder care on a per capita basis has been falling. Public resources for elder care in relation to the proportion of persons in the population 80 years and older was 15 per cent lower in fixed prices in 2000 than it was in 1990 (SOU 2004:68, p. 147). Further, declining resources are targeted to the neediest, while those with less extensive care needs are increasingly left without public support. Between 1980 and 2006, the share of Swedish older persons (80 years or older) receiving publicly financed elder care has decreased from 62 to 37 per cent (Szebehely 2009).

New public management in Swedish elder care

In 1992, a new Local Government Act in Sweden increased the latitude of local politicians to explore the institutional and organisational changes typical of the NPM. The new Act allowed municipalities to enter contracts with private providers—even for-profit companies—which had earlier been explicitly forbidden by law. These ‘alternative actors’ are allowed to organise and run the publicly financed elder care services on their own terms, provided that content and costs stay within the framework of the locally established contracts and the law. The Local Government Act allows municipalities two possibilities when relinquishing responsibility for these services to private organisations. They can either outsource services to external providers after a process of competitive tendering, or develop a system of ‘consumer choice’ to allow elderly citizens to choose the organisation, public or private, from which they receive publicly subsidised services.

It should be noted that, in the 1990s, public discourse in Sweden on 85the future of the welfare state was markedly ideological, and came to be labelled ‘the system shift debate’. This debate was particularly intense during the time the right-wing parties held government from 1991–94. The prevailing side in the debate criticised bureaucratic organisations as inflexible and authoritarian. Competition was supposed to bring about creative entrepreneurship and thus revitalise the field (Antman 1994; Gustafsson 1996; see also Vabø 2006).

Arguments for different purchaser-provider models—which were a central theme in a debate where only shifts of nuance could be observed between the Social Democratic and the right-wing positions—all included an appeal for individual choice in order to improve the quality of services. Under a choice model, ‘consumers’ would be able to vote with their feet, complementing their voices as citizens who choose elected representatives to the municipal councils. A subsidiary theme was the promise of an improved work environment for elder care personnel. In strained municipal economies, however, opening elderly care to competition increasingly led to demands for inproved productivity and cost effectiveness.

Since the introduction of the Local Government Act, the purchaser-provider model of outsourcing has been applied widely. In 1993, 10 per cent of Swedish municipalities used this model; by 2003, the share had grown to 82 per cent (National Board of Health and Welfare 2004a). Private employers’ share of publicly financed elder care services has also increased steadily and almost continuously. According to the latest official statistics, in 2005 almost 15 per cent of all employees working with care of the elderly and the disabled had private employers: 11 per cent worked in for-profit establishments (mostly for large international companies) and 3.5 per cent worked in non-profit organisations (Szebehely & Trydegård 2007). This means a fourfold increase nationally since 1993, although inter-municipal variation is great. Some municipalities around Stockholm have more than half their elder care in private hands, compared to less than one per cent in around one-third of all Swedish municipalities (National Board of Health and Welfare 2007b). 86

The majority of privately run elder care is in the form of outsourcing although the number of municipalities that have introduced a consumer-choice model has increased from 10 in the year 2003 to 27 in 2006 (of a total of 290 municipalities in Sweden) (National Board of Health and Welfare 2007a).3

A common feature of organisational changes in Swedish welfare services during the 1990s has been the lack of follow-up and empirical research on the impact of changes on service and job quality (Palme et al. 2003). A review of the limited research shows, however, that there is probably little difference in the quality of care between the privately and publicly run establishments (National Board of Health and Welfare 2004b). Further, there are indications that opening elder care to competition has led to higher, rather than lower, municipal costs (National Board of Health and Welfare 2004b). When it comes to the working environment in elder care, research has not established whether privatisation has led to advantages or disadvantages for elder care personnel (this applies also to health care services in general, see further Blomqvist 2005; Gustafsson 2005). In the Nordic region generally, there is a lack of systematic research on the working conditions of elder care personnel under public versus private operation (Trydegård 2005).4 One aim of this chapter is to contribute some empirical research on this question.

Social infrastructure and public employers

One central line of reasoning among Swedish 87advocates for purchaser-provider models during the 1990s was that new and possibly more efficient (private) providers should be invited to participate in competitive tendering. At the same time, the discretion and power of local politicians should be preserved, and even strengthened, in their new purchasing role. Inherent in this line of reasoning is the assumption that the relationship between employers and employees is similar in the public and in the private sectors (du Gay 2000). Yet history shows that politically appointed employers in the field of ‘welfare production’ answer to different constituencies and are responsible for different tasks, compared with private employers.

One important difference between private and public employers is that the latter often have more or less explicit mandates to change either the society they govern, or some individuals therein. This applies particularly to welfare services; examples are improvements in the levels of education, public health, democracy and social integration. Private employers, historically speaking, have not had such responsibilities (even if some have done so) and must be subjected to political regulation if this is to be the norm. If such regulation is implemented, it has to work alongside the priorities chosen by the shareholders, within the framework of market conditions.

Most welfare service work involves creating and maintaining relationships between at least four parties: employer, employee, the welfare service recipients, and their next of kin. Further, in practical terms, all these actors are also members of the same political community, which means that their civil and social rights are connected to their political rights as voting citizens. Thus welfare services are something more than, and different from, work and service in the established senses of the words. A service provided under the Schools Act in Sweden is not only aimed at ensuring an 88economically efficient transfer of knowledge from teachers to pupils under the control of an employer, but also at creating a democratic mindset in future citizens. In elder care services, ageing Muslims, Mosaics, Lutherans or atheists, whether rich or poor, are to meet frailty, dependency and finally death with equal dignity.

Achieving these goals requires a complex interaction in the social network around the employer (the local politician), the employee (the teacher, the caregiver) and the citizen (the pupil, the parents, the elderly). This unique characteristic of welfare work makes particular demands on the public employer. Welfare services have a moral, political and cultural content, and can thus be conceptualised as the social infrastructure of a society. Many of the intangible benefits created by welfare services have effects that transcend time and space. Some of the children in publicly funded child care will perhaps, in 30 or 40 years, be candidates for the post of UN Secretary-General; others will perhaps be international criminals. If the 50-year-olds of today begin to worry about what will happen to elder care services in 25–30 years (or to their parents’ elder care today), their own work and consumption patterns, as well as gender relations, will be affected.

All this means that the public employer faces a problem of democratic legitimacy private employers do not. This becomes clear when we distinguish between the external and internal legitimacy of welfare systems. The external legitimacy of welfare systems—that is, the strength of political support among the citizens and taxpayers—has been the object of considerable empirical research in Sweden (Svallfors 2003). Compared with citizens of other countries, Swedes tend to favour the public financing of welfare systems and to accept high taxes. The internal legitimacy of the welfare system refers to corresponding issues in the inner life of the welfare-service producing organisations. The internal legitimacy of welfare policy builds on—or is undermined by—the views and perspectives of welfare services personnel on the political control of their own working conditions. In light of the ongoing outsourcing movement, 89we ought to differentiate between direct internal legitimacy issues (concerning the majority of elder care provision that is still run by public employers), and the indirect internal legitimacy that is at stake when private providers are contracted. This has seldom been discussed, and applies not only to financing, but also to organisational matters. Who makes decisions for whom? How are the rewards and burdens of the work distributed? How do careworkers experience the influence of local politicians? These are the questions we address in our empirical study.

Working in Swedish elder care: a case study

In this section, we present a case study that aims to deepen understanding of the recent changes in the organisation and political regulation of Swedish elder care. The empirical base is a mail questionnaire carried out in the autumn of 2003, which surveyed all categories of care personnel and local politicians in eight Swedish municipalities. We received just over 5,800 responses to questions about working conditions, internal organisational relationships, and views of elder care. The response rate was 66 per cent among careworkers and 72 per cent among politicians (for further information, see Gustafsson & Szebehely 2005). In this chapter, we analyse only the answers from the largest group of personnel, those involved in elder care services (n=3,522). This group includes skilled and unskilled careworkers in home-based and residential elder care. We refer to these personnel throughout as careworkers.

The choice of eight municipalities was mainly dictated by our ambition to include both those municipalities where all elder care was still in public hands, and those with a relatively large share of outsourced elder care (none, however, had adopted a consumer-choice model). Of the careworkers in our study, 14 per cent had private employers; the share varied from 0 per cent in four municipalities to between 10 and 50 per cent in the other four municipalities. Almost the entire group of the privately employed 90careworkers worked in for-profit companies; only a few were employed by non-profit organisations. The eight municipalities in the study are, taken together, representative of elder care services in Sweden in terms of the occupational distribution, forms of employment, part-time/full-time, age and gender (see Gustafsson & Szebehely 2005).

In what follows, we compare the views of publicly and privately employed careworkers on their work environments, the role of local politicians, and the outsourcing of elder care.

Private and public employment and the psychosocial work environment

Previous studies of elder care have shown that, generally, the work environment has deteriorated since outsourcing was introduced. Above all, the workload has grown (Bäckman 2001; Gustafsson & Szebehely 2005). However, these studies do not allow us to ascertain the extent to which deteriorating working conditions are caused by outsourcing alone, or by simultaneous cutbacks in financing and other (possible) interacting factors. In contrast, our survey allows us to analyse possible differences between the work experiences of publicly employed careworkers and the experiences of privately employed (outsourced) careworkers, in tax-financed Swedish elder care today.

Earlier research has found that elder careworkers experience their work as meaningful and rewarding, but also as physically and mentally demanding. Given the complexity of the work, it is important to capture both positive and negative dimensions of the work environment. We designed questionnaire items to assess:

1) Relations with management (‘Do you have a good working relationship with your supervisor(s)?’);

2) Control (‘Can you affect your working conditions so that, for example, you can work at your own pace?’);91

3) Job content (‘Are your work tasks varied enough?’ and ‘Do you find your work interesting and stimulating?’);

4) Workload (‘Do you feel you have too much to do at work?’);

5) Relations with care recipients (‘Do you feel inadequate because the care recipients do not get the help they need?’).5

All these dimensions seem to be important for health and wellbeing according to previous research on the work environment in general and in elder care in particular (Dellve 2003).

Along with these indicators of the careworkers’ evaluations of their work environment, we were also interested in their experiences of physical and mental fatigue. These feelings are clearly related to the work environment, even if exhaustion may have causes other than working conditions. Questions were formulated as follows: ‘Do you feel mentally exhausted after your working day?’ and ‘Do you feel physically exhausted after your working day?’6

It is obvious from our own research and from other studies that the work environments in residential and home-based care services are rather different. The two care settings differ in terms of workload and relations with both supervisors and care recipients. In most respects, work in residential care is more arduous than work in home-based care (Gustafsson & Szebehely 2005; Trydegård 2005). To take these differences into account, therefore, we analyse the two care settings separately.7

Table 4.1 shows the percentages of publicly and privately employed careworkers in the two care settings who answered ‘Yes, most often’ to each of the eight indicators. The data show that there are only minor differences between the perceptions of publicly and privately employed careworkers on most dimensions of their working conditions. We also see that the few statistically significant differences between public and private employment in residential care and home-based care point in opposite directions. In some respects the work environment is perceived to be slightly better among privately employed careworkers in residential care (compared to careworkers in publicly run residential care). In home-based care, by contrast, publicly employed careworkers find their work environment to be slightly better in some respects, compared with careworkers in privately run home-based care.

92

Table 4.1: Careworkers’ assessment of their work environment and experience of fatigue8

| Residential care | Home-based care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shares answering ‘Yes, most often’ (%) | Publicly run (n≥2142) |

Privately run (n≥362) |

Publicly run (n≥860) |

Privately run (n≥101) |

| Can affect working conditions, e.g. pace of work | 31.7 | 31.9 | 26.5 | 25.7 |

| Have good contact with supervisors | 50.1 | 60.1 *** | 54.9 | 43.6 * |

| Find work sufficiently varied | 36.8 | 36.9 | 46.4 | 43.6 |

| Find work interesting and stimulating | 52.4 | 57.0 | 60.3 | 50.5 |

| Have too much to do | 37.0 | 39.8 | 29.5 | 26.7 |

| Feel inadequate because recipients do not get the help they need | 33.1 | 26.5 * | 23.8 | 26.7 |

| Physically exhausted after a working day | 29.4 | 27.2 | 20.6 | 26.5 |

| Mentally exhausted after a working day | 17.8 | 14.7 | 10.6 | 18.6 * |

* p<0.05; *** p<0.001

93To check whether the pattern found is related to the form of operation (public vs. private employment), or to possible differences in the composition of the care workforce in the two settings, we used multivariate analysis (logistic regression). In that analysis, we controlled for differences between the privately and the publicly employed careworkers in five respects: age, gender, part-time/full-time, length of employment, and locality (that is, the municipality where the careworker is working), see Appendix. This analysis shows that when we take into account variations in age, gender, work time, length of employment and locality, there remain even fewer differences between the privately and the publicly employed careworkers’ evaluations of their work environment. The public employees working in residential elder care run a 41 per cent higher ‘risk’ (odds) of feeling inadequate in relation to the needs of the care receivers. In home-based care, on the other hand, the public employees have almost twice the ‘chance’ (odds) of having good relations with their supervisors.

Our results suggest, then, that outsourcing has had different consequences for careworkers in home-based and residential care services. At the same time, it is important to note that differences between public and private employees’ experiences turn out to be small (and often less than the differences between home-based and residential care, see Table 4.1). We find only marginal differences on 94such important work environment issues as workload, control over working conditions, and how varied the work is. To sum up, the results indicate that there are no systematic or substantial differences between publicly and privately employed careworkers’ evaluations of their work environments that can be linked to the form of operations (public or private).

However, there are differences between the municipalities in the study. These are far greater than any differences between public and private employment. A clear—if simplified—conclusion, therefore, is that careworkers looking to improve their lot would be better served by seeking employment in the right municipality than by considering the pros and cons of publicly versus privately run elder care.

Perceptions of local politicians in purchaser-provider systems

A fundamental and explicit idea behind the outsourcing of care services in Sweden is that politicians should have less to say about the details of how things should be run, in order to be free to concentrate on overall policy, prioritise resources, and focus on their role as consumers’ advocates (Montin & Elander 1995). With the introduction of purchaser-provider models in elder care, local politicians’ direct control over private employees’ work environment has been deliberately reduced (Gustafsson & Szebehely 2002). The question now is how the careworkers view this reduced political control.

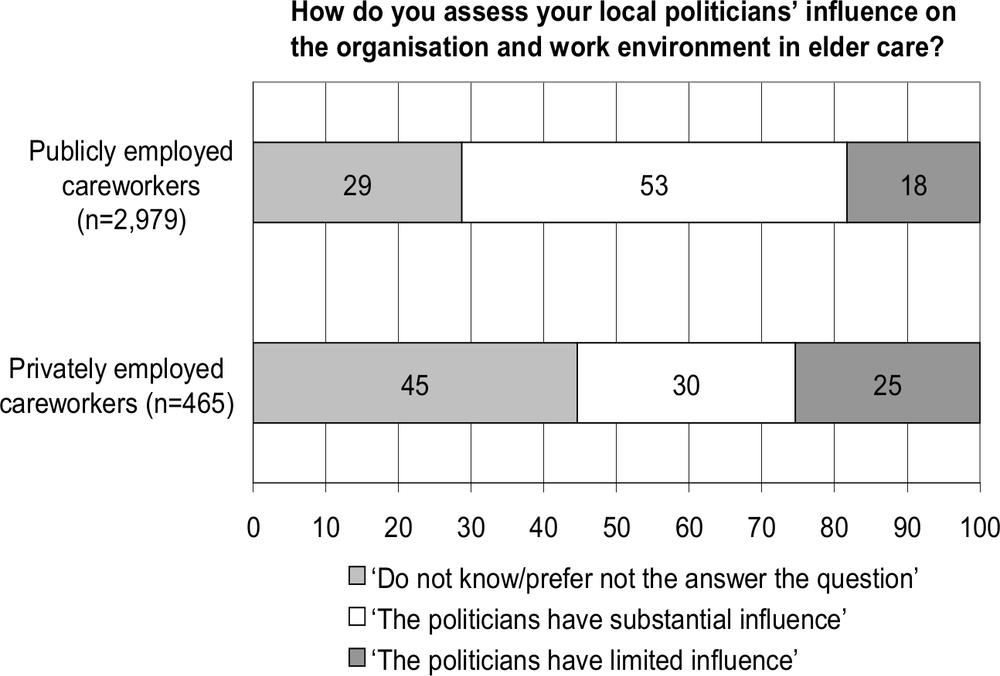

Figure 4.1: Careworkers’ assessment of local politicians’ influence on organisation/work environment in elder care9

Figure 4.1 shows the careworkers’ responses to the question ‘how do you assess your local politicians’ influence on the organisation and working environment in elder care?’ A clear pattern emerges: within publicly managed elder care the dominant response is that politicians have substantial influence over working conditions (53 per cent compared with 30 per cent of the privately employed). A reasonable interpretation is that this is a reflection of the true nature of things, namely that local politicians, having relinquished 95control of services to private companies, no longer have employer responsibility for those privately employed. The figure also shows that the most common response among the privately employed is ‘do not know/prefer not to answer the question’. The significantly higher share of uncertainty among the privately employed (45 per cent compared with 29 per cent among public employees) can be interpreted to mean that private employees experience the role of local politicians as more diffuse and the relations as more ‘distant’. This interpretation is supported by the response pattern shown in Figure 4.2.

96

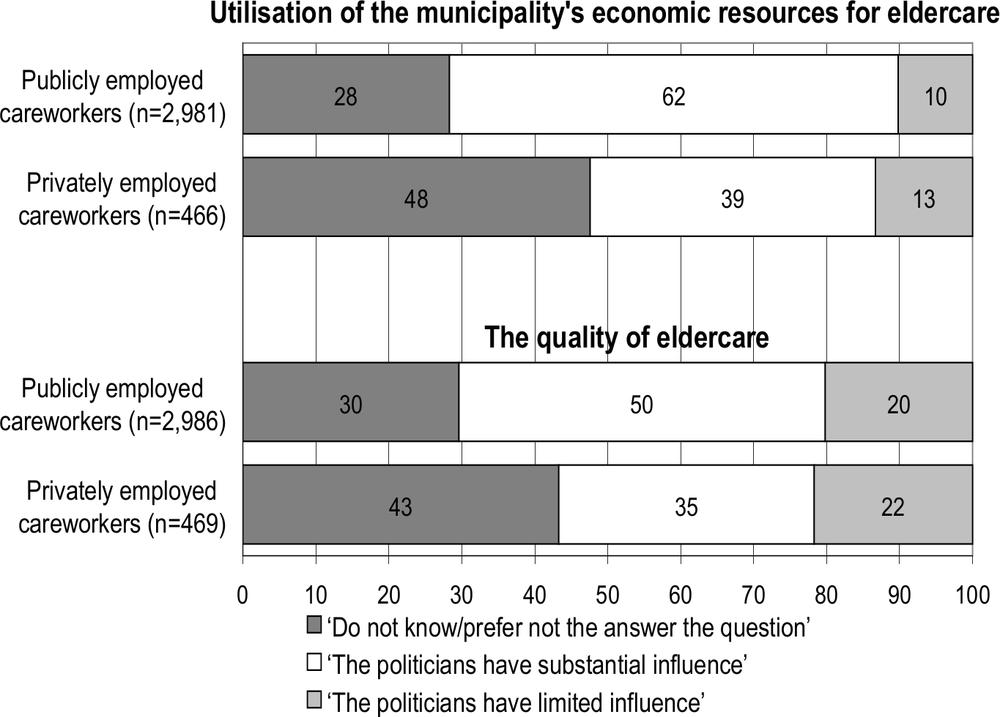

Figure 4.2: Careworkers’ assessment of local politicians’ influence on economic and quality issues in elder care10

Figure 4.2 shows careworkers’ responses to the questions ‘how do you assess your local politicians’ influence on the utilisation of the municipality’s economic resources’ and on ‘the quality of elder care’.

97We can see that a significantly larger share of the private employees (compared with public employees) is uncertain even in the matter of local politicians’ influence over the economy and quality of elder care.

We can also see that private employees are much less inclined to attribute any degree of influence to local politicians.11 This pattern applies even to areas where—according to the advocates of purchaser-provider models—outsourcing is not intended to reduce political influence. All in all, this suggests that careworkers’ relations with local politicians tend to be experienced as more diffuse when mediated by a private entrepreneur, as is the case with outsourced elder care.

Who wants more outsourced elder care?

One important factor for the future development of elder care that has been largely ignored in research and public debate is careworkers’ opinions for or against a market orientation in elder care. Our study has been able to ascertain that local politicians and senior civil servants have much more positive views towards outsourcing than the average careworker (Gustafsson & Szebehely 2002; 2005). In the following, we analyse opinions for and against outsourcing of elder care services in relation to the careworkers’ assessments of their own work environments and in relation to their estimations of the local politicians’ influence over the work environment. We begin with an overall description of the state of opinion.

Our point of departure is the following question in the survey: ‘The

98following proposals have appeared in the political debate. What is your opinion of each proposal?’ Here we analyse the proposal: ‘More elder care should be run under private management’.12 Of the publicly employed careworkers, 21 per cent considered this to be a very good or good idea, 52 per cent that it was a bad or very bad idea, while 28 per cent were neither for nor against. Thus among the public employees there were significantly more who were negative than positive towards expanding privately run elder care. Their balance of opinion can thus be stated as –31 (the percentage of those positive minus the percentage of those against). Of the privately employed careworkers, 38 per cent pronounced this a very good or good idea, 33 per cent a bad or very bad idea, while 30 per cent were neither for nor against, giving a balance of opinion of +5. In summary, the dominant attitude among the public employees was clearly sceptical, while among the private employees there was a weak tendency towards support for the proposal.

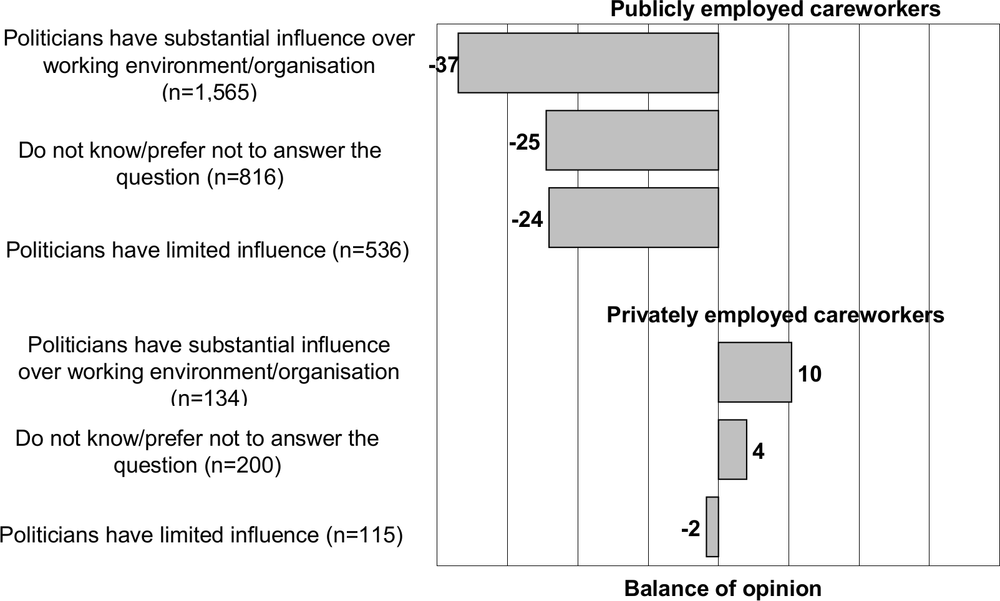

We shall now consider a possible connection between careworkers’ opinions about market orientation and their assessments of the extent of political influence over the work environment (that is, the item that produced the response pattern shown in Figure 4.1). Figure 4.3 clearly shows that the dominant attitude to further outsourcing is negative among public employees, irrespective of how they assess local politicians’ influence over their work environment (balance of opinion between –37 and –24), while the privately employed have a neutral to slightly positive balance of opinion (between –2 and +10).13

99

Figure 4.3: Attitudes to further outsourcing of elder care (balance of opinion) among careworkers with different assessments of local politicians’ influence over work environment and the organisation of elder care

100Among the public employees, however, we also see that the most negative attitudes are held by those who judge the local politicians to have a considerable influence over their work environment (balance of opinion –37). According to Figure 4.3, even private employees have different attitudes to further outsourcing depending on their views of political influence over the work environment. These differences—which point in the opposite direction—are not, however, statistically significant.

These findings indicate that the perception of the local politicians’ role is of differing importance for publicly and privately employed careworkers’ views on outsourcing. We draw the conclusion that for public employees, there is a connection between scepticism towards outsourcing and perceived political influence over the work environment, while this connection does not exist among the private employees.

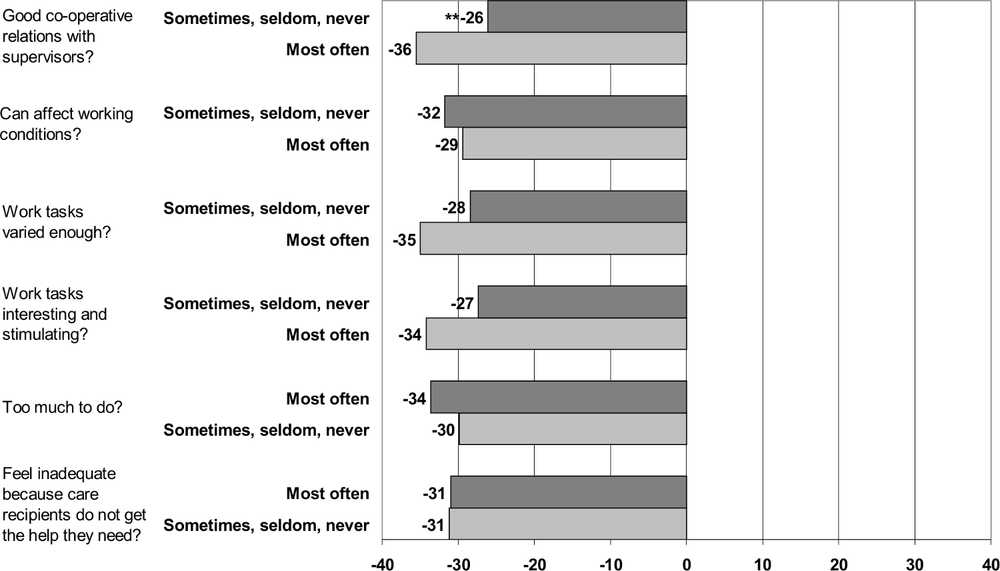

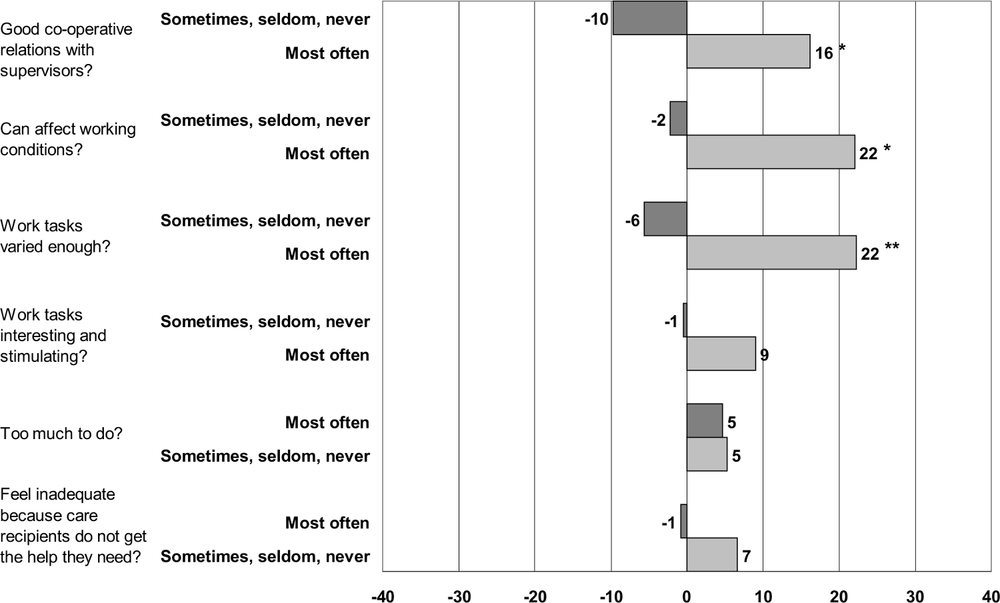

How important, then, are evaluations of the work environment for attitudes to market orientation? Figure 4.4a depicts a predominantly negative attitude to market orientation among the public employees, irrespective of their views on their own work environment (balance of opinion from –26 to –36).14 It also shows that differences in the balance of opinion are small between those who gave a positive evaluation (lighter bars) compared to those who gave a negative evaluation (darker bars) of their work environment. There is only one statistically significant correlation between work environment and balance of opinion on outsourcing: public employees who most often have good contact with their supervisors are more negative towards outsourcing (balance of opinion –36) than those who ‘sometimes’, ‘seldom’ or ‘never’ experience good relations (balance of opinion –26). However, when controlled for other differences between the groups, this correlation is not significant (see note 14). There are, then, no statistically significant correlations between public employees’ evaluations of their work environments and their attitudes to outsourcing. To stress the point, one can say that publicly employed careworkers tend to be sceptical of the market approach, even when they report a bad work environment in their own non-outsourced elder care. Later we discuss how this somewhat surprising result can be interpreted.

101

Figure 4.4a: Attitudes to outsourcing of elder care (balance of opinion) among public careworkers by evaluation of work environment, per cent

102

Figure 4.4b: Attitudes to outsourcing of elder care (balance of opinion) among private careworkers by evaluation of work environment, per cent

103Figure 4.4b shows that there are greater differences in the balance of opinion towards outsourcing between the private employees who consider themselves to have a ‘good’ work environment and those who report a ‘bad’ work environment. The most positive towards market orientation are those who ‘most often’ can affect their own working conditions (balance of opinion +22), who experience the work as varied (balance of opinion +22) and who experience their relations with supervisors as good (balance of opinion +16). The most negative (balance of opinion –2 to –10) are those who responded ‘sometimes’, ‘seldom’, or ‘never’ to these three work environment questions. The difference in response pattern between the private employees with ‘good’ and ‘bad’ work environment respectively is statistically significant, and remains so even when controlled for other differences in group make-up (see note 14). Other work environment indicators have no correlation with the view of market orientation, however.

Is there an underlying logic that explains these response patterns? At first sight, it might seem natural to point to the work environment itself. Even if there are no clear, large or systematic differences between privately and publicly run elder care in how careworkers overall evaluate their work environments, there are workplaces with ‘good’ or ‘bad’ work environments within both forms of operation. 104

An anomaly in the results is that the public employees seem to apply a different logic from that of private employees, since public employees make no specific connections between their own work environments and the outsourcing of elder care. Among the private employees, by contrast, there is such a connection; a good work environment is coupled with a positive view on outsourcing, while those with less satisfactory work environments tend to have negative views. Both the private and the public employees’ response patterns become comprehensible, however, if the ongoing outsourcing trend is seen as a process affecting careworkers’ relations to local politicians.

Within publicly managed elder care we have established a strong negative balance of opinion against outsourcing, especially among those careworkers who estimate that the politicians have an extensive influence over the work environment (Figure 4.3). Since these careworkers’ assessments of their own work environments have little impact on their views of market orientation in the publicly run elder care, it seems reasonable to conclude that few publicly employed careworkers see outsourcing as a way to improve their work environments; not even among those with negative work environment experiences do we find a positive balance of opinion for outsourcing (Figure 4.4a). Our tentative conclusion, therefore, is that publicly employed careworkers see local politicians’ influence over their work environment as—at least partly—a positive force, or in any case as a protective factor.

On the other hand, within outsourced elder care—that is, in a context where careworkers estimate that political influence over the work environment is limited—we have established several connections between assessment of the work environment and attitude to outsourcing. Our interpretation here is that private employees who have a positive evaluation of their own work environment attribute this, at least partly, to outsourcing. 105

Summary and conclusions

In this article we have attempted to give a broad empirical analysis of the experience of, and attitudes to, outsourcing of elder care in Sweden among careworkers. The main results—which build on more than 3,500 careworkers’ questionnaire responses in eight Swedish municipalities in 2003—can be summarised as follows.

Work environment

When we isolated the differences in the work environment that could be directly connected to the form of operation (that is, public or private), only a few statistically significant correlations could be established. We have not found any systematic, unequivocal, or large differences between public and private employees’ evaluations of their work environments. All in all, the results must be interpreted to mean that the ‘public-private management’ variable cannot be coupled with work environment as a decisive factor.

Variations between municipalities play a far more important role in this connection. Exactly what, in turn, determines these municipal differences we have not been able to establish, but we surmise that local variation is shaped by the interplay of contextual factors such as personnel policy, the level and allocation of economic resources for elder care, and the way competitive tendering is handled. Different municipalities and companies operate under different conditions and policies. Thus, to estimate the specific and probably minor importance of forms of operation for the work environment, further research is needed, mainly in the form of case studies. Further studies are also needed to ascertain whether outsourcing has different effects on the work environment in home-based and residential care, respectively. This is also true of other possible ‘outcome variables’ that have emerged in the Swedish debate, not least the quality of elder care and its cost effectiveness. 106

Political control

Our study directs attention to previously unresearched differences between private and public elder care employees in terms of their perceptions of local political control. For private employees, the local politicians’ role appears substantially more diffuse and of less importance than for public employees. In this area, it turns out, there are systematic and large differences that can be linked to the public-private employment variable: private employees are far less inclined than public employees to attribute a significant degree of influence to local politicians over the organisation/work environment, the quality of care and even the use of taxpayers’ economic resources.

Opinions for and against outsourcing

Most public employees have negative attitudes towards outsourcing (irrespective of how they assess their own work environment), while the private employees are in general more positive towards continued outsourcing (especially if they perceive their own work environment in positive terms).

Since we have established that outsourcing has no clear ‘winners’ or ‘losers’ on the aggregate level, we suggest that opinion for or against outsourcing is conditioned by different perceptions of the role of the local politicians. Private employees who, by their own evaluation, have a relatively good work environment—those who may consider themselves ‘the work environment winners of outsourcing’—see no danger in ‘freeing’ their work environment from local political influence. And vice versa: those publicly employed careworkers who can be considered ‘the work environment losers of public management’, and who generally appear to be more interested in local politics than the private employees, seem to be hanging on to a hope that the local politicians will come to take more responsibility for work environments.

The private elder care employees’ response pattern might be interpreted as an expression of a more individualistic stance, where one’s own work environment experiences laid the ground for opinion on 107outsourcing. The public employees, on the other hand, can be seen as more publicly or collectively oriented. Public elder care employees are usually more negative towards outsourcing—and more knowledgeable about and positive towards political influence over the work environment—even when they assess their own work environment as unsatisfactory.

Considered together, our results indicate that outsourcing is a process that severely weakens careworkers’ relations to local politicians, which in turn colours their general attitude to political control, rather than a process that improves quality of care, reduces costs or, for that matter, changes working conditions for the better or for the worse. In our interpretation the outsourcing trend signifies a crucial change concerning the internal legitimacy of the political steering of the elder care services. Outsourcing is connected to a diminishing visibility of, interest in, and possibly belief in the positive role of local government among privately employed careworkers, especially those who happen to be ‘work-environment winners’. This more diffuse view on political influence through locally elected representatives applies, somewhat surprisingly, even to matters that are formally kept under political influence in outsourced elder care, that is, ‘the utilisation of the municipality’s economic resources for elder care’ and the local politician’s influence on ‘the quality of elder care’.

Internal legitimacy and social infrastructure

Our article should be seen as an empirically based attempt to expand welfare policy analysis: elder care personnel and managements do not only produce help for the elderly. Elder care is also a part of society’s social infrastructure. Opinions and attitudes of relevance for the long-run democratic development of society are created in the interaction between politics, management and care work.

If the tendencies we have demonstrated among the private elder care employees in our study were to become a general trend in Swedish elder care—and we can see no reason why this should not be the case 108in the wake of a continued expansion of outsourcing—this may erode the legitimacy of the welfare state as a part of the social infrastructure of a political democracy. Local politicians who pursue a market policy—because they believe in competition, because they hope to reduce costs, because they wish to promote individual choice, or because they believe and hope that the quality of care and possibly the work environment will improve—risk undermining careworkers’ belief in a positive role of politics and its accountability.

References

Antman, P. 1994, ‘Vägen till systemskiftet—den offentliga sektorn i politiken 1970–1992’ [The road to the system shift: the public sector in politics 1970–1992] in Köp och sälj, var god och svälj? Vårdens nya ekonomistyr-ningssystem i ett arbetsmiljöperspektiv [A Work Environment Perspective on New Economic Management in Care Services], ed. R. Å. Gustafsson. Arbetsmiljöfonden, Stockholm, pp. 19–66.

Anttonen, A. 2002, ‘Universalism and social policy: A Nordic-feminist revaluation’, NORA: Nordic Journal of Women’s Studies, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 71–80.

Blomqvist, P. 2005, ‘Privatisering av sjukvård: politisk lösning eller komplikation?’ [Privatisation of health care: A political solution or complication?] Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, no. 2–3, pp. 169–89.

Bäckman, O. 2001, ‘Med välfärdsstaten som arbetsgivare’ [The welfare state as employer], in Välfärdstjänster i omvandling [Welfare Services in Transition], ed. M. Szebehely, SOU 2001:52, Research Volume, Government Report, The Welfare Commission, Stockholm, pp. 189–238.

Dellve, L. 2003, Explaining Occupational Disorders and Work Ability among Home Care Workers (PhD thesis), The Sahlgrenska Academy, Göteborg University.

du Gay, P. 2000, In Praise of Bureaucracy, Sage, London.

Gustafsson, R. Å. 1996, ‘Freedom of choice and competition in the public sector—A conceptual analysis’, in Health Care in Europe: Competition or 109Solidarity? eds S. Iliffe & H.U. Deppe, Verlag für Akademische Schriften, Frankfurt-Bockenheim.

Gustafsson, R. Å. 2000, Välfärdstjänstearbetet: Dragkampen mellan offentligt och privat i ett historie-sociologiskt perspektiv. [Welfare Work: Struggles for Public and Private from the Perspective of Historical Sociology], Daidalos, Göteborg.

Gustafsson, R. Å. 2005, ‘The welfare of the welfare services’, in Worklife and Health in Sweden 2004, eds R. Å. Gustafsson & I. Lundberg, National Institute for Working Life, Stockholm.

Gustafsson, R. Å. & Szebehely, M. 2002, ‘Skilda perspektiv på politikerrollen inom äldreomsorgen—om beställar-utförarmodeller i praktiken’ [Differing perspectives on the role of politicians in elder care: the purchaser-provider split in practice], Tidskrift for Velferdsforskning, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 68–84.

Gustafsson, R. Å. & Szebehely, M. 2005, Arbetsvillkor och styrning i äldreomsorgens hierarki—en enkätstudie bland personal och politiker [Working Conditions and Steering in the Hierarchy of Elder Care. A Survey Study among Employees and Politicians], Department of Social Work, Stockholm University.

Gustafsson, R. Å. & Szebehely, M. 2007, ‘Privat och offentlig äldreomsorg—svenska omsorgsarbetares syn på arbetsmiljö och politisk styrning’ [Private and public elder care: Swedish careworkers’ opinions on their work environment and local government], Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 47–66.

Hood, C. 1998, The Art of the State—Culture, Rhetoric and Public Management, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Kolberg, J. E. (ed.) 1991, The Welfare State as Employer, Sharpe, Armonk, N.Y.

Kröger, T. 1997, ‘The dilemma of municipalities: Scandinavian approaches to child day-care provision’, Journal of Social Policy, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 485–508.

Mann, M. 2006 [1993], The Sources of Social Power. The Rise of Classes and Nation-States 1760–1914, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 110

Millar, J. & Warman, A. 1996, Family Obligations in Europe, Family Policy Studies Centre, London.

Ministry of Health and Social Affairs 2007, ‘Care of the Elderly in Sweden’, Fact Sheet, September, Government Offices of Sweden.

Montin, S. & Elander, I. 1995, ‘Citizenship, consumerism and local government in Sweden’, Scandinavian Political Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 25–51.

National Board of Health and Welfare 2004a, Konkurrensutsättningen inom äldreomsorgen. [Competitive Tendering in Care of the Elderly], National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen), Stockholm.

National Board of Health and Welfare 2004b, Konkurrensutsättning och entreprenader inom äldreomsorgen. Utvecklingsläget 2003 [Competitive Tendering and Outsourcing in Care of the Elderly. Report of the Situtation 2003], National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen), Stockholm.

National Board of Health and Welfare 2007a, Current Developments in Care of the Elderly in Sweden, National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen), Stockholm.

National Board of Health and Welfare 2007b, Lika olika socialtjänst? Kommunala skillnader i prioritering, kostnader och verksamhet [Similar or Different Social Services? Municipal Differences in Priorities, Expenditure and Services], National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen), Stockholm.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2005, Long Term Care for Older People, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

Palme, J., Bergmark, Å., Bäckman, O., Estrada, F., Fritzell, J., Lundberg, O., Sjöberg, O., Sommestad, L. & Szebehely, M. 2003, ‘A welfare balance sheet for the 1990s. Final report of the Swedish Welfare Commission’, Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, Supplement 60, pp. 7–143.

Pollitt, C. 1995, ‘Justification by works or by faith: Evaluating New Public Management’, Evaluation, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 133–54.

Pollitt, C. & Boucaert, G. 2000, Public Management Reform—A Comparative Analysis, Oxford University Press, Oxford. 111

Rosenau, P. & Linder, S. H. 2003, ‘Two decades of research comparing for-profit and non-profit health provider performance in the United States’, Social Science Quarterly, vol. 84, no. 2, pp. 219–41.

Sipilä, J. (ed.) 1997, Social Care Services: The Key to the Scandinavian Welfare Model, Avebury, Aldershot.

SOU, 2004:68 Sammanhållen hemvård [Integrated home care], Government Report, Stockholm.

Svallfors, S. 2003, ‘Welfare regimes and welfare opinions: a comparison of eight Western countries’, Social Indicators Research, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 495–520.

Szebehely, M. 2009, ‘Are there lessons to learn from Sweden?’, in A Place to Call Home: Long-term Care in Canada, eds P. Armstrong, M. Boscoe, B. Clow, K. Grant, M. Haworth-Brockman, B. Jackson, A. Pederson, M. Seeley & J. Springer, Fernwood Books, Toronto.

Szebehely, M. & Trydegård, G.-B. 2007, ‘Omsorgstjänster för äldre och funktionshindrade: skilda villkor, skilda trender?’ [Services for elderly and for disabled persons: different trends, different conditions?], Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, vol. 14, nos. 2–3, 197–219.

Trydegård, G.-B. 2000, Tradition, Change and Variation. Past and Present Trends in Public Old Age Care (PhD Thesis). Department of Social Work, Stockholm University.

Trydegård, G.-B. 2005, ‘Äldreomsorgspersonalens arbetsvillkor i Norden—en forskningsöversikt’ [The working conditions of elder care staff in the Nordic countries: A research overview], in Äldreomsorgsforskning i Norden. En kunskapsöversikt [Nordic Elder Care Research. An Overview], ed. M. Szebehely, Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen, pp. 143–95.

Vabø, M. 2005, ‘New Public Management i nordisk eldreomsorg—hva forskes det på?’ [New Public Management in Nordic elder care: what do researchers focus on?] in Äldreomsorgsforskning i Norden. En kunskapsöversikt [Nordic Elder Care Research. An Overview], ed. M. Szebehely, Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen, pp. 73–111.

Vabø, M. 2006, ‘Caring for people or caring for proxy consumers?’ European Societies, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 403–22. 112

Appendix

Careworkers’ assessments of their work environments and experience of fatigue. Logistic regression. Odds ratios comparing publicly and privately employed careworkers controlling for age, gender, full-time/part-time, length of employment with present employer and municipality.

| Residential care (n≥2367) |

Home-based care (n≥915) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publicly run |

Privately run |

Publicly run |

Privately run | |

| Have good contact with supervisors (most often) | 1 | 1.14 | 1 | 0.51 *** |

| Can affect working conditions, e.g. working pace (most often) | 1 | 0.92 | 1 | 1.08 |

| Find work sufficiently varied (most often) | 1 | 1.29 | 1 | 0.82 |

| Find work interesting and stimulating (most often) | 1 | 1.26 | 1 | 0.66 |

| Have too much to do (most often) | 1 | 0.93 | 1 | 0.76 |

| Feel inadequate because care receivers do not get the help they should (most often) | 1 | 0.71 * | 1 | 1.08 |

| Physically exhausted after a working day (most often) | 1 | 0.83 | 1 | 1.17 |

| Mentally exhausted after a working day (most often) | 1 | 0.71 | 1 | 1.31 |

*** p<0.001; * p<0.05

1 This chapter presents findings previously discussed in Gustafsson and Szebehely (2007).

2 Editors’ note: we have maintained the authors’ use of the term ‘elder care’, rather than standardising usage to the typical Australian expression ‘aged care’.

3 Since the re-election of a centre-right coalition in 2006, there is an increasing state-initiated push towards more consumer-choice models in Swedish elder care (Ministry of Health and Social Affairs 2007). So far, however, the Swedish municipalities still possess self-government in this matter, whereas a purchaser-provider split combined with a consumer-choice model in home-care services is mandatory, by legislation, in all Danish municipalities since 2003 (Vabø 2005).

4 There is extensive research on private forms of care in the international literature. The most wide-ranging overviews that we are aware of indicate a number of negative experiences of privately run or privately financed care; see further Rosenau and Linder (2003). However, this research is difficult to relate to Swedish conditions since labour legislation and social policies in Sweden differ in many ways from those in the countries where these studies have been conducted.

5 Each item has four response alternatives: ‘Yes, most often’; ‘Yes, sometimes’; ‘No, seldom’; and ‘No, never’.

6 The response categories for both questions on fatigue were: ‘Yes, most often’; ‘Yes, quite often’; ‘Yes, sometimes’; ‘No, seldom’; and ‘No, almost never’.

7 Residential care in this context includes both traditional institutions such as nursing homes and old people’s homes, and different forms of sheltered accommodation.

8 Note that a higher percentage in the four questions above the dotted line in Table 4.1 indicates a better work environment, while a higher percentage in the four questions below the line indicates that the work environment is worse.

9 A χ2 test shows the difference to be significant: p=0.000. Concerning the issues discussed in Figure 4.1 and the rest of the article, there were only marginal differences found between home-based careworkers and those working with residential care. We do not, therefore, make any separation in the following. We have consistently conducted analyses (multinominal logistic regressions) where we have controlled for differences between public and private employees regarding age, gender, work time, length of employment, locality and home-based or residential workplace. The difference between public and private employees in their assessment of local politicians’ influence over work environment/organisation in Figure 4.1 is statistically significant (p=0.000) even after controlling for these factors.

10 A χ2 test shows the difference to be significant: p=0.000. Multinominal logistic regression (see note 9) shows that the difference between public and private employees’ opinions of local politicians’ influence over economic resources (p=0.028) and elder care quality (p=0.003) is statistically significant.

11 It is important to note that it is only in their relation to politicians that the ‘don’t know’ response is higher among the privately than the publicly employed. While 51 per cent of public employees and 64 per cent of private employees stated they did not know whether their work was appreciated by local politicians, on the questions of whether they felt appreciated by supervisors and by workmates, the percentage of ‘don’t know’ responses did not vary with public vs. private employment—6 per cent and 7 per cent respectively (supervisors) and 3 per cent and 4 per cent (workmates). The percentages were also significantly less. Therefore, this is not about a general tendency towards more uncertain responses among the privately employed.

12 Response alternatives were as follows: ‘A very good idea’; ‘A good idea’; ‘Neither good nor bad’; ‘A bad idea’ and ‘A very bad idea’.

13 Bivariate analysis (χ2) shows that the difference in attitudes to further outsourcing between groups with different views of politicians’ influence is significant (p=0.000) among the publicly employed but not among the privately employed. Separate multinominal logistic regressions for both public and private employees (controlled for the variables listed in note 9) show the pattern to be constant: among private employees there is no statistically significant correlation between view of politicians’ influence and view of market orientation, while the correlation is significant among public employees (p=0.000).

14 This note refers to both figures 4.4a and 4.4b. χ2 test: ** p<0.01; * p<0.05. Multivariate analysis (see note 9) shows that among the public employees no work environment indicators have any statistically significant correlations with view of outsourcing when controlled for differences in group make-up with regard to age, gender, locality, et cetera, while among the private employees the three correlations between own work environment and view of outsourcing that are significant in Figure 4.4b remain; (p=0.005, p=0.016 and p=0.001 respectively).