2

The political economy of for-profit paid care: theory and evidence

In recent decades, for-profit provision of social care—care for children, the elderly and people with disabilities—has increased, particularly in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States.1 This growth has precipitated much debate about the role of for-profit organisations in providing care, because for-profit provision of care seems to involve a clash of images, values and interests. The pursuit of ‘fat-trimming’ cost efficiency by self-interested shareholders seems to fit ill with the image of care as other-oriented service to those in need. That said, the rising cost of and demand for social care services does seem to demand mechanisms that contain costs and promote innovation—mechanisms many economists and policy-makers believe that markets best supply. This paper explores theoretical debates about the compatibility of profits and care, to document the potential strengths and weaknesses of for-profit provision of care. A brief survey of evidence from several social care fields attempts to establish the actual strengths and weaknesses of care as enterprise.

Two main policies have facilitated growth in for-profit provision of social care services in OECD countries in recent years: vouchers or

14rebates to individuals seeking care services, and government contracting (Gilbert 2005). These policy changes have taken place in the context of expanding demand for paid care and an ideological backlash against public provision, particularly in liberal welfare states.

Policies that allocate cash, vouchers or rebates to individuals bolster consumers’ purchasing power and choice, in turn creating opportunities for (subsidised) profit that attract private providers of social care services. In Australian child care, for example, the extension of fee relief to users in the early 1990s allowed the number of child care places and the for-profit sector to expand, with for-profit growth compounded by the removal of operating subsidies for competing non-profit, community-based long day care centres in 1996 (Brennan 2007). Similarly in the United States, tax credits combined with reduced federal regulation in the 1980s stimulated growth in for-profit child care. Chain-affiliated for-profits targeted the middle and upper income families benefiting from tax credits, while obtaining advantages by lowering staff-child ratios and salaries in response to deregulation (Tuominen 1991, p. 461).

For-profit provision of social care services has also been stimulated by government contracting, as governments have sought either to privatise public services or to expand service provision without expanding the public sector. The typical mode of contracting in the social care field is purchaser-provider arrangements, which aim to create arms-length market-type relations by separating public funding from service provision. Under these arrangements public purchasing decisions are based on provider performance, and so are, ideally, neutral to ownership or providers’ organisational form. In the United Kingdom, for example, the NHS and Community Act (1990) facilitated both growth in domiciliary care and growth in for-profit providers, as local authorities increasingly contracted with private organisations (Scourfield 2006). In the United States, the sweeping reforms to income support programs under the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act 1996 included 15provisions that made for-profits eligible to contract for an expanded range of associated services, including welfare case management, children’s services, mental health, and residential or outpatient care (Dias & Maynard-Moody 2006; Gibelman & Demone 2002).

Mapping the territory

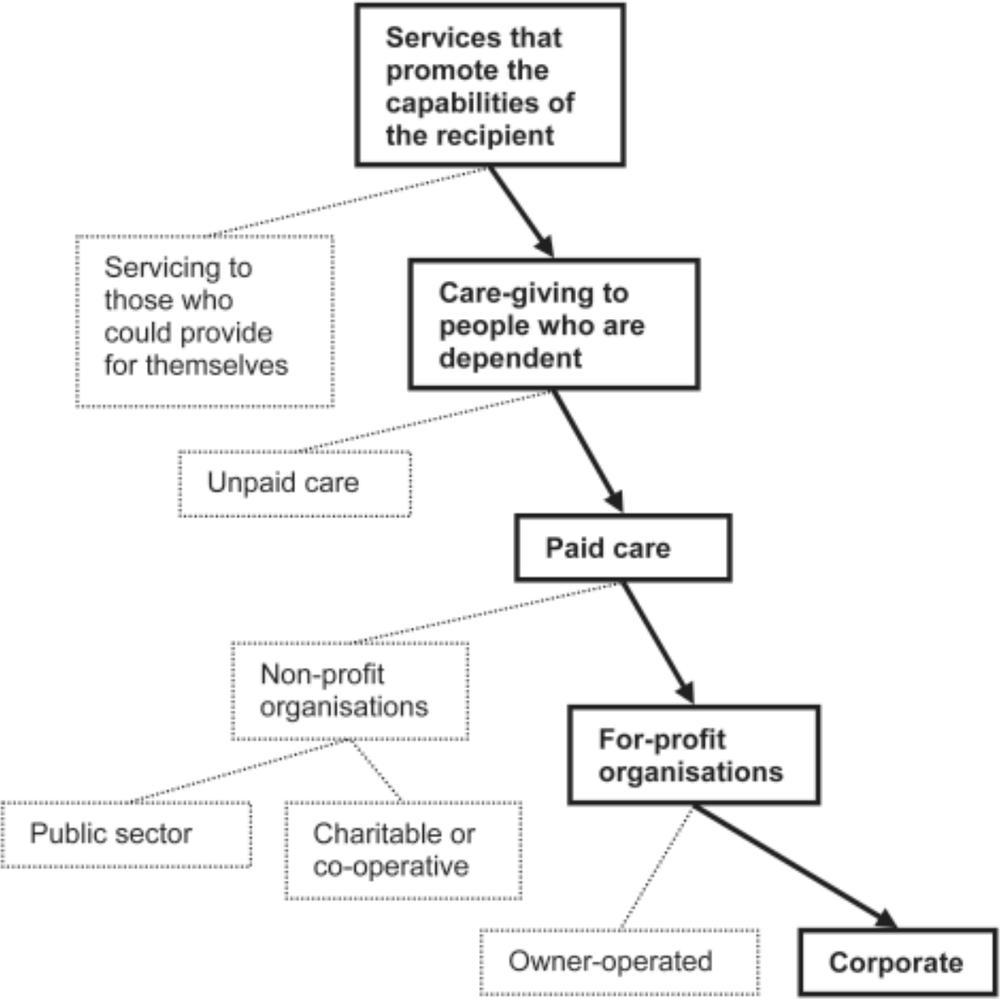

Our aim is to investigate what might be specific about the dynamics and consequences of care delivered in particular relationships and institutional settings, namely care provided by paid workers employed by for-profit organisations. Before we begin to examine the arguments and evidence about for-profit paid care, we need to define our focus by establishing some key conceptual distinctions (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: For-profit paid care: mapping the territory

16First, as many theorists of care and care work have noted, the concept of care is complex. One reason is its diverse meanings in ordinary language, as a noun to denote both activities (such as nurturance) and feelings (such as worry and affection), and as the related verbs to care for (one’s hair, spouse, friends) and to care about (one’s appearance, children, students, or world poverty). Researchers on care work usually define care more narrowly; England and colleagues, for example, define it as ‘a face-to-face service that develops the capabilities of the recipient’ (2002, p. 455). But even on this more narrow definition, which clearly excludes the personal toilette and political commitments, social policy analysts need to distinguish ‘care-giving’ to people who are dependent, from ‘servicing’ those who could otherwise perform the relevant activities themselves (see Wærness 1984). Our focus is on care, defined as services that promote the capabilities of recipients who are unable to provide those services for themselves.

Complexities remain. The kind of care we focus on is practised in a range of relationships, including natural (parent and child), chosen (friend and friend), professional (teacher and student), commercial (employee and customer), or mandated (statutory social worker and foster child). In all of these relationships, money may or may not change hands between the carer and cared-for2 so we need to make some further distinctions, of which the first is between unpaid and

17paid care. Although unpaid and paid care share many features (see Himmelweit 1999), they also differ (Meagher 2006), and our interest is in paid care. Theorists of paid care have debated whether paying for care will ‘crowd out’ carers’ altruistic motivation (England 2005; Folbre & Nelson 2000; Nelson 1999). One persuasive claim to emerge from this debate is that the effect of payment on motivation depends on whether payment is perceived as controlling or acknowledging careworkers’ intrinsic orientation towards care. Writing about nurses, Nelson and Folbre argue that, in the first case, ‘overly regimented work and payment structures … can, indeed, lead to reduced feeling of vocation’ (2006, p. 129). In the second, they argue, ‘If high pay is given in such a way that nurses feel respected and rewarded for their care and professionalism, feelings of vocation can be reinforced and expanded’ (2006, p. 129).

These arguments are about how individuals respond to payments, but they make clear reference to the impact of institutional or organisational arrangements on how payment affects carer motivation. And care work takes place in many institutional settings, including families, community networks, non-profit agencies, fee-for-service arrangements, corporations, and public institutions. It is reasonable to conjecture that the impact of institutional structure and practice on the organisation, experience and practice of care might differ systematically between these institutions. We are particularly interested in any difference that for-profit institutional structure and practice might make to the quality and experience of care for both workers and recipients.

Defining precisely what we mean by ‘for-profit’ is important, because all sorts of arrangements in which money changes hands for care have been labelled as ‘commodification’ or ‘marketisation’ of care (see, for example, Ungerson 1997), and these terms easily blur with the more specific concept of for-profit provision. Production for profit involves the systematic creation of a revenue stream from private capital ownership. This revenue is distributed to capital owners, 18who have an interest in the revenue being as large as is sustainable.3 In competitive markets, private firms stay profitable by using the resources they have at their disposal, including labour, in the most productive ways possible. As we shall see in the following section, both its champions and critics respectively emphasise what they see as the benefits and risks of the dynamic process of production for profit. For-profit organisations take two primary forms—owner-operated firms, typically on a small scale; and corporations, in which ownership and management are separated, and ownership may be dispersed among many shareholders. Some evidence suggests that in the social care field, at least, these two types of for-profit organisations may operate quite differently (Morris 1999).

A final distinction we need to make is one between actual for-profit organisations (firms), and the extension of the discourses and practices of for-profit organisations into the public and third sectors, without necessarily changing their ownership structures. This extension has been a key element of the ‘New Public Management’, along with actual privatisation and the growth of a for-profit social care sector. Our focus is on actual private sector organisations—although as we shall see, there is debate about whether it really makes a difference if organisations are ‘actual’ or ‘discursive’ private businesses.

Profit and care: arguments for and against

Arguments for for-profit paid care

Both moral and economic arguments for private, for-profit provision of paid care exist, and both kinds of arguments share an assumption that care is like any other good or service, best—or at least not harmed by being—produced and distributed through markets.

19Proponents of the moral value of markets see anonymous, profit-motivated market exchanges to have ‘civilising’ potential, as they encourage the moral virtues of efficiency and enterprise, and promote social order through cooperation among strangers (Fourcade & Healy 2007, p. 304). From this perspective, the pursuit of profit is an intrinsic human freedom, with private exchanges perceived to offer autonomy and choice to both producers and consumers (Dowding & John n.d.).

More commonly, proponents of for-profit provision draw arguments from economic rather than moral theory. Arguments about the economic benefits of for-profit care focus on three areas: for-profits’ incentives to efficiency, innovation and growth; the responsiveness and sustainability of private investment compared with government borrowing or charitable donations; and the capacity of for-profits to complement non-profit and government activity.

First, orthodox theories of the market treat profit as the reward for efficient and effective production. Competition for profit share is thought to filter out inefficient or low quality providers and drive costs down. The pursuit of profit can also be argued to promote innovation, with competition requiring providers to specialise in response to consumer preferences (Le Grand 1998). Further, profit can provide incentives for growth, with growth leading to further cost advantages (and benefits for consumers) through economies of scale like collective purchasing and flexible deployment of resources (including labour) across sites (Davis 1993; Holden 2005).

Second, for-profit provision can be argued to overcome constraints on government and non-profit performance and resourcing. Unlike public providers, for-profits operate at arms length from political processes, so can focus completely on cost and quality (Le Grand 1998). For-profits also have freer access to sources of investment. Private investment is argued to be more sustainable and responsive than government borrowing, private donation or sponsorship, offering a way to reduce the cost of government where this is a political goal (Le Grand 1998; Pearson & Martin 2005). 20

A third set of economic arguments highlight roles for private providers in mixed markets, on the basis that for-profits can supplement and complement government and non-profit activity. For-profits may play a supplementary or ‘gap filling’ role, by offering different products to non-profits, and operating in separate market niches (Abzug & Webb 1999). For-profits may also play a complementary role, comfortably co-existing with (or even enhancing) government or non-profit agencies, where they are operated as subsidiaries and can subsidise their ‘parent’ organisations’ social missions (Salaman 1999). Alternatively, for-profits may comfortably co-exist with other organisations under quasi-market arrangements, by competing with non-profits to deliver services on behalf of governments, and complying with government regulation (Le Grand 1998).

Arguments against for-profit paid care

Unlike arguments for for-profits, which treat care as a generic product, critics frame care as a social good with general benefits for the economy and society, and focus on the relational characteristics that differentiate care from other activities and products. As well as the physical activities of ‘caring for’, care work involves ways of feeling and regarding another, with human virtues of affection, commitment, intimacy, and attentiveness argued to produce a sense of support and wellbeing in others (Lynch 2007; Stone 2005). As we noted above, critics argue that marketisation has a corrosive impact on these moral and emotional dimensions of care, seen as essential for human flourishing. A subset of arguments against marketisation or commodification relates specifically to the impact of for-profit provision on the organisation, practice and experience of care services. In many of these arguments, moral and economic dimensions are inextricably linked.

Objections to for-profits highlight problems of inefficiency, poorer quality, inequity and lack of accountability. First, profit is seen as a poor economic incentive for achieving social goals. Care is a public 21good, better produced and distributed according to human need than skewed by investors’ self-interest (Schmid 2001). Critics raise concerns that because for-profits are controlled by owners of capital, provision will be guided by expectations of investment returns, so will be ‘auctioned to the highest bidder’ rather than guided by social needs or priorities. For-profits will gravitate to the most profitable end of the market, the impact being to ‘cream’ the least disadvantaged clients, to divert resources from the neediest needy people to (not needy) shareholders, and to crowd out the pursuit of collective goals (Gibelman & Demone 2002). In addition, for-profits may routinely under-serve or maintain ‘excess demand’ to stabilise high occupancy or placement rates, and to elevate prices and profits (Davis 1993). Second, it is not clear that, in the end, private provision is actually efficient, since governments often need to offer citizens significant fiscal incentives to take up private services, and the cost of these incentives may be so large as to eliminate the fiscal gains of reducing direct expenditure in the first place (Pearson & Martin 2005, p. 31).

Other critics question the ‘trustworthiness’ of for-profits where markets are imperfect. Care recipients do not fit the model of fully rational consumers able to exercise choice, accurately assess quality, choose between alternatives, and exit the market when a product fails to satisfy (Hirschmann 1970). Care recipients, and those purchasing care on their behalf can access only imperfect information, as care takes place over extended periods of time and is highly personal, making it difficult (and expensive) to monitor quality (Folbre & Nelson 2000). This raises risks that opportunistic for-profits will exploit consumers’ inability to fully monitor services by charging high prices but skimping on those aspects of quality which consumers find difficult to observe and respond to (Hirth 1997, p. 419; Morris & Helburn 2000). That is, for-profits may ‘sell low-quality care as if it were of high quality’ (Morris 1999, p. 142). Compounding this, for-profits lack organisational values and social missions against which they can be held to account (and which offer symbolic assurance of 22quality); and they have less thorough public reporting requirements and democratic accountability, and may shy from evaluation of their outcomes (Gibelman & Demone 2002, p. 395).

Another set of arguments highlights the supposedly negative implications of growth. Pursuing profit exposes care services to speculative investment as well as mergers and takeovers, processes which risk reducing the competition supposed to keep service provision efficient, and exposing care provision to the possibility of collapse (Scourfield 2007; Salaman 1999). Profit-seeking growth also increases the dominance of chains which, controlled by off-site management and shareholders, are seen as more aggressive profit-maximisers than smaller, independent for-profits (Morris 1999). Further, increased concentration may make care markets difficult to regulate, as large profit-seeking providers can entrench their interests by influencing regulation and shaping the terms of the market (see Press & Woodrow 2009; Scourfield 2007).

A final set of arguments against for-profits highlights working conditions and the organisation of work. Crucial here is the idea that ‘profitable care’ and ‘quality care’ conflict. Workers are the major determinants of care quality—and the major component of costs. Because care involves relationship-building, any increases in productivity will reduce quality (Morris 1999; Himmelweit 2007). Quality declines as the need to minimise costs causes for-profits to circumscribe the time available for the relationship-building at the heart of good care. The risk here is that ‘caring’ motivation (a guarantee of quality and effectiveness) will be squeezed out, with care instead performed ‘lovelessly’, impersonally and to minimum standards (King 2007, p. 203; Folbre & Nelson 2000). As Lynch puts it:

When a “care” relationship is set within a system of social relations focused on profit or gain in particular, it is self-evident that the care dimension of this relationship is likely to be either precluded, subordinated, or made highly contingent on the profit-margins expected (2007, p. 563). 23

For-profits’ imperative to minimise costs places pressure on labour, lowering staff-to-client ratios, wages, skills, training and professional development, and contributing to problems in recruiting and retaining staff (Schmid 2001). Profit also provides an incentive to produce those more physically visible, measurable aspects of care, which are easiest to clearly codify in contracts to be bought and sold. The main consequence is reduced professional discretion and therapeutic work in for-profits and a tendency to squeeze out those more fluid interpersonal aspects of labour processes which seem to yield few tangible results, like attentiveness and friendship, and, at an organisational level, participation of workers and consumers in decision-making (Scourfield 2007; Schmid 2001).

Arguments that for-profit status doesn’t matter

A third set of arguments holds that organisational form matters little to care. Some we have already canvassed treat the involvement of money, not profits per se as the key problem for care provision (Stone 2005), so that many of the organisations included in Figure 2.1, not just for-profits, would engender the same problems. This is because, as Stone puts it, paying for care compels third-party purchasers to ‘count it, monitor it, define it, and limit it’ (2005, p. 282–83), and to prioritise the physical acts or ‘doing’ of care over the less tangible ‘being’ of care. In this frame, it is not (only) the pursuit of profits, but paying for care, contracting for care, and bureaucratising care that risks reducing care to mundane, physical, measurable elements.

By contrast, some analysts see concerns about for-profit status as exaggerated. They claim that real world markets and organisations do not operate according to the competitive and profit-maximising ideal, but instead involve complex social relationships and institutions, and the profit motive can be bounded and controlled (Folbre & Nelson 2000). Some feminist economists, for example, have questioned dualisms between self-interested behaviour in supposedly impersonal markets, and virtuous motivation in the non-market sphere, pointing out for-profit provision can embody a range 24of values and strategies (Folbre & Nelson 2000; Nelson & England 2002). Some for-profits may pursue only small profits alongside social goals rather than being driven by ‘financial gain above all else’ (Nelson & England 2002, p. 5). These arguments suggest it is how care services are delivered, not the ownership structure of the delivering organisation, that matters most. As motivations for care are complex and layered, the pursuit of profit will not, inevitably, squeeze moral virtue or quality out of care.

Another set of arguments highlights pressures towards organisational ‘isomorphism’ which obviate the differences between organisations with different ownership structures (Estes & Swan 1994). Some emphasise the importance of institutional networks, and their structure, over ownership (Perry 1998, p. 414; Le Grand 1998). On this view, government contracting can neutralise differences in for-profit and non-profit behaviour, with regulation and quasi-market competition driving providers both to mimic each other and to emulate the government agencies on which they depend (see also Estes & Swan 1994, p. 279). When obliged to conform to the same regulations and outcome standards, contractors, regardless of organisational form, are expected to develop similar service delivery structures and technologies (Schmid & Nirel 2004). In this frame, organisations are dynamic. Rather than ownership determining behaviour, organisations respond to each other in competitive environments, and to regulation.

The disability rights movement’s call for ‘nothing about us without us’, and for the rights of people with disabilities to live independently, also imply that ownership structure is not a critical determinant of service quality and access. What matters is that users ‘have choice over … who provides assistance and control over when and how that assistance is provided’ (Carmichael & Brown 2002, p. 805, emphasis in original).4

25Control may also be important to service providers as well as service users, and may eclipse profit-maximising as a primary goal, particularly among small, owner-operated, for-profit providers. When autonomy and a modicum of professional satisfaction replace profit maximising as an organisational goal, some of the consequences feared by critics of the provision of care for profit may not materialise (Kendall 2001; Matosevic et al. 2007; 2008). These are the ‘dwarves of capitalism’, and suggest that when it comes to the impact of ownership on services, size matters (Davidson 2009).

Professionalism can, in theory, also play a role in reducing the differences between for-profit and non-profit providers. Professionalism has been posited as a ‘third logic’, beside the logic of markets and bureaucracies (Freidson 2001, cited in Evetts 2003). On this view, where professionals provide services, they adhere to norms and practices defined by their occupation rather than by the organisations for which they work, regardless of ownership. There are, of course, positive and negative views of professionalism: proponents see professionalism as offering a framework for the development and practice of norms that support high-quality care, based on specialised expertise and commitment to professional ethics, while critics see professionalism as the paternalistic exercise of power by self-interested members of state-sanctioned monopolies (Evetts 2003; Knijn & Verhagen 2007; Meagher 2006).

Evidence from social care systems

Many arguments for and against for-profit provision—and some that are indifferent—rest on theoretical claims about ideal typical behaviours and organisations. Yet whether or not organisational form makes a difference to the quality and accessibility of paid care services is an empirical question. In this section we consider 26research evidence on whether the quality of care is different in for-profit organisations in three social care sectors: residential aged care, child care, and home care for the aged and people with disabilities.

Residential aged care

With few exceptions (for example, Castle & Shea 1998), studies show inferior standards of quality in for-profit residential aged care (Aaronson et al. 1994; Castle & Engberg 2007; Davis 1993; Harrington et al. 2001; Martin 2005). Staffing is a consistent theme. In the United States, a study of over 13,000 federally regulated nursing homes revealed investor-owned homes had lower staffing ratios than non-profits or public homes, with chain ownership associated with the lowest levels of quality (Harrington et al. 2001). Similarly, in Canada, for-profit status is associated with lower levels of staff-client contact than in non-profits, with studies showing they deliver fewer hours of direct nursing care (Berta et al. 2005; McGrail et al. 2007; McGregor et al. 2005).

In Australia’s residential care sector, too, for-profits have been found to have fewer aged care workers per bed than non-profits and government operated facilities, higher staff turnover, higher staff vacancy rates (especially for registered nurses), and higher use of agency staff (Martin 2005). However, despite this discrepancy, when asked about various aspects of their work, such as pressure to work harder, ability to spend enough time with each resident, level of freedom to decide how to do their work, and capacity to use their skills, workers in non-profit and for-profit facilities gave very similar answers (King & Martin 2009).

In terms of care outcomes, for-profits appear to have poorer health outcomes. In a study of 449 nursing homes in Pennsylvania, Aaronson and colleagues (1994) found that residents of for-profit homes had higher risks of pressure sores than residents of non-profits, and for-profits used restraints on the elderly more often. Another study of 422 hospices across the United States found that patients in for-profit 27facilities received a narrower range of care services than in non-profits, controlled for a range of confounding factors (Carlson et al. 2004).

Hospitalisation rates provide further evidence of poorer outcomes of for-profit nursing home care. A study of more than 43,000 residents of subsidised nursing homes in British Columbia (McGregor et al. 2006) found for-profits had higher hospitalisation rates for some conditions (pneumonia, anaemia and dehydration) although differences were not significant for falls, urinary tract infections or gangrene. In that large study, the lowest hospitalisation rates came from non-profit facilities attached to a hospital or health authority (presumably due to their proximity to health professionals), or those that were multi-site, with the latter tending to be better staffed and to have better access to health professionals (who may, for example, be shared between sites).

Other studies point to the negative impact of growth and concentration in the residential care sector. In the United Kingdom in particular, mergers and acquisitions have compounded concentration in aged care since the late 1990s. These processes, it is argued, allow more aggressive profiteering, as they have shifted political power from regulators to the largest for-profits and, in the process, have limited scope for choice, service user involvement and professional discretion (Drakeford 2006; Holden 2005; Scourfield 2007).

While there is little evidence that quality standards are higher in private for-profit residential care, studies into care-home providers’ motivations (potentially a proxy for quality) suggest ownership status may not make a significant difference. A series of English studies has found that regardless of whether they were operating as public, private or voluntary providers, care-home managers reported aspiring to professional goals, and the desire to meet older people’s needs (intrinsic motivators), over any desire for personal income or profit (extrinsic motivators) (Matosevic et al. 2007; 2008). Moreover, private providers should not be assumed to be profit-maximisers—the desire for autonomy and independence are also important motivators 28among the small-business operators of care homes who participated in Kendall’s English study (2001). The findings of these studies are interesting, but not entirely comparable with the studies we discuss above. One problem is that providers’ attitudes may not be a reliable and valid measure of service quality, because they may not directly translate into organisational policy and behaviour. Matosevic and colleagues surveyed ‘managers’ of public, voluntary non-profit and for-profit care homes, and more than a third of respondents from for-profit homes were neither owners nor owner-managers. These respondents probably worked in the corporate sector.5 How much scope these managers have to set organisational policies and service standards on the basis of their own motivations for working in aged care is not established.

Child care

Studies of child care also contribute a considerable body of evidence to support the argument that for-profit organisations are more likely to provide services of inferior quality. And like for-profit residential aged care, staffing and staffing ratios are recurrent themes in studies of the quality of child care.

In a study of 325 child care centres in Canada, for example, Cleveland and Krashinsky (2005) found a statistically significant difference in the quality of the environment and of care in for-profit and non-profit centres, with for-profit centres over-represented among poor quality services. However, much depends on the type of non-profit or for-profits (with chain-affiliated centres performing the worst),

29and on the character of licensing and regulation (Morris & Helburn 2000). In a study of 401 centres in four representative states of the United States, Morris and Helburn (2000) found higher staff ratios in independent and church-affiliated non-profits, and in public child care centres, and lower ratios in those centres operated by for-profits, but also in those operated by community agencies and churches. Morris found for-profits skimp on staff wages and qualifications, instead spending more on facilities than non-profits (1999, p. 138).

As well as operating with lower staff ratios and lower paid staff, there is evidence that for-profit child care centres may be less likely to publicly state their staffing standards. A study of 115 American child care centres (Gelles 2000) found that, in the absence of strong regulation, for-profit centres were less likely to state their staff-child ratios in written advertising material (19 per cent of for-profits did compared with 44 per cent of non-profits). As well as failing to state standards against which they could be held accountable, for-profits were more likely to regroup children throughout the day, temporarily lowering staffing ratios at the expense of stability in children’s care environment, and without parents’ knowledge (Gelles 2000, p. 240). In addition, Gelles (2000) found patterns of volunteering (which offers a way for parents to monitor the centre’s internal operations) differed significantly between for-profit and non-profit child care centres. Only one per cent of for-profits reported seven or more volunteer hours a week, compared with 30 per cent of non-profits. Together, these practices make it more difficult to monitor for-profit performance, and to hold them to account.

Some studies explicitly test the theory that for-profit child care centres are less ‘trustworthy’ than non-profits, exploring whether they will exploit consumers’ inability to accurately assess quality by enhancing superficial aspects of quality in attempts to lower cost without losing business (Morris 1999). Morris and Helburn (2000) examined whether for-profit child care centres were more likely to direct effort to ‘easy to observe’ aspects of quality (like centre appearance) while skimping on supervised learning programs and 30staff-child interactions, which involve more highly trained staff and higher staff-to-child ratios. They confirm that skimping on the hard to observe aspects of quality occurs where lower licensing standards allow staff ratios and staff training to fall (in their multi-state study, this was in North Carolina). For-profits affiliated with chains, in particular, were found to skimp on activities undertaken while parents were not present (including meals, supervision of creative play, supervision of fine motor activities, staff cooperation and staff professional development opportunities). Compared with independent for-profits, chain-affiliated for-profits focused their efforts more strongly on greeting and departing, personal grooming, furnishings, child-related displays, space, equipment, and provisions for parents (such as meeting areas). Community agencies also provided lower hard-to-observe quality for preschoolers, which the authors attributed to either managerial laxness or shirking where agencies had long contracts with government departments (Morris & Helburn 2000).

Further evidence of poorer performance by for-profits relates to equity, with for-profits found to serve smaller proportions of low-income children and children with special needs (Cleveland & Krashinsky 2005; Morris & Helburn 2000). Preston (1993) also found that, in the absence of regulation in the United States, non-profits provided services with higher levels of ‘social externalities’, measured in terms of service to children who were black, minority, or from poor or single parent families. That study also found lower levels of extra early childhood and counselling services in for-profit child care centres. However, minority participation levelled where centres were subject to stringent regulation, although non-profits maintained advantages in terms of staff quality and provision of extra early childhood services.

There is also some evidence to support the argument that size matters when it comes to for-profit provision of child care (Rush 2007; Morris & Helburn 2000). For example, one Australian study of centre-based child care quality, based on a survey of 578 childcare workers, found 31significant differences on most main measures of service quality between (large) corporate chains on one hand and (small) owner-operated for-profit providers and non-profit providers on the other (Rush 2007).

Home care for the elderly and people with disabilities

Evidence about for-profits in home care is mixed, with several studies pointing to the potential for regulation to neutralise differences in behaviour deriving from organisational form.

One study of 750 home care clients in Ontario (where providers are required to meet specific standards) found that, for the most part, there were no differences in the care provided by for-profits and non-profits, although clients of for-profits were slightly more satisfied with their care, and had slightly better mental health outcomes than those of non-profits (Doran et al. 2007). However, other Ontario studies draw evidence from home care workers, showing lower wages and working conditions in the for-profit sector. Aronson and colleagues (2004) examined the consequences of layoffs of 317 non-profit home care support workers in 2002, finding that most who stayed in the sector were absorbed by for-profits and suffered deterioration in their wages and conditions. A third Ontario study draws evidence from 835 home care workers (Denton et al. 2007). Denton and colleagues identify problems of job satisfaction and staff turnover, but attribute this to the character of managed competition, which, rather than for-profit status, they argue, reduces job security, erodes organisational and peer support, and shifts organisational values from ‘caring’ to business priorities. Thus, overarching market structures, which engender organisational isomorphism among providers with different ownership structures, may de-differentiate the quality of care and work, bringing both down by ‘spreading the bads’ between providers of different ownership status (see also Gustafsson & Szebehely 2009).

Researchers in the United Kingdom also emphasise the importance of regulatory arrangements. In a study of 155 providers in eleven 32English local authorities, Forder and colleagues (2002) highlight how the type of contract between purchasers and providers, rather than ownership per se, influences how home-care organisations pursue profit. They found that regardless of ownership structure, recipients of grants (lump sums with broad service specifications) placed a lower priority on profit-making than those engaged on contracts for specified quantities of service, or those contracting on the basis of price per case. This adds weight to arguments that the character of contracts and regulation may be more important influences on organisational behaviour than ownership or organisational form.

The case of home care also offers support for arguments downplaying the role of ownership, showing how regulation can neutralise the effects of ownership differences. A ten-year longitudinal study examined the growth of Israeli home care services, which was facilitated by the introduction of social insurance contributions (Schmid 2001). That study showed government contracting caused the strategic, structural, administrative and human behaviour of for-profits and non-profits to blur. Both non-profits and for-profits became more dependent on government resources, adopted similar service technologies and similar pricing, financing and marketing strategies, and transmitted professional norms. Professional communication networks minimised differences, and executives moved across sectors, transmitting policies and processes as they went (Schmid 2001).

Nevertheless, Schmid (2001) found that private providers did perform worse than non-profits in the first few years of contracting, although distinctions lessened over the decade. For-profits ‘caught up’ by establishing links with governments, adhering to standards, setting up quality control systems, formalising work roles and systems, investing more in training, and reducing staff turnover. After ten years, for-profits were virtually indistinguishable from non-profits in terms of service effectiveness and client satisfaction, causing the author to call for research and policy to focus on the key 33problem not of who provides services, but on how care is organised and provided (Schmid 2001).

British studies of the motivations of domiciliary care providers find that they are, like the motivations of residential care providers, mixed, with the desire to make money co-existing with the desire for professional satisfaction and to help others. The balance between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations may differ by ownership type, but so does the capacity to express intrinsic motivations, which depends much on the external environment. The researchers stress the role of contract specification and the experience of day-to-day relationships with local authority purchasers in determining whether motivations that support high-quality care are crowded in—or out (Kendall et al. 2003).

Given the theoretical potential for professionalism to support high-quality care, Knijn and Verhagen’s (2007) study of the impact of payments for care on professionalism in home care offers a further useful insight into the dynamic effects of the emergence of markets in home care services. These researchers argue that professionalism in home care has been put under significant pressure by one key method of promoting a market in home care services; viz. direct payments to service users. Direct payments push care out of the public sector, into the private domains of the family and market. In many European countries, for example, service users can pay family members to provide care. One result of this is that home care, as a ‘weak profession’, is poorly placed to resist perceptions that it is not clearly distinguishable from what family members can offer, more cheaply, and more warmly. Further, direct payment systems typically decouple public funding from public provision, opening up private markets for home care, markets in which pressures for cost-cutting are strong, thereby undermining the quality of both care and employment in the sector. 34

Taking stock

Abstract principles from economics and moral theory are invoked by some participants in the debate about for-profit care. However, the debate takes place in a specific historical context, in which several trends converge to create demand for paid care services and in which for-profit paid care becomes one way of meeting that demand.

Population ageing, changing family structures and increasing participation in the labour market by women are increasing demand for provision of care services outside the family. Writing about Western Europe, but making arguments also applicable in the English-speaking liberal welfare states, Fargion argues that these changes ‘reduce … the practical possibilities for inter-generational cooperation, thereby increasing the difficulties in the performance of caring functions within the primary network’ (Fargion 2000, p. 61).

Increasing demand is expressed as increasing expectations by citizens that social care services will be provided in some form by governments. But the emergence of new care needs has coincided with concern that claims on the welfare state need to be constrained, and that the size of the public sector needs to be contained, and if possible, reduced. Thus, privatisation of social care has emerged as a solution—the institutional size of the public sector has been contained in English-speaking countries, while service provision can be expanded through public subsidies to private sector (both for-profit and non-profit) organisations.

Because the changes that have ‘defamilialised’ informal care and ‘privatised’ social care have been so profound and contested, it is not surprising that the debate about for-profit paid care is caught up in wider debates about the nature of the good society. These debates canvass questions about the appropriate scope of the market (as a domain of freedom or exploitation, depending on one’s point of view), the proper role of governments and the public sector (as an inefficient and coercive institution or as an expression of collective 35responsibility, again depending on one’s point of view), and the place of women in the public sphere.

That the debate about for-profit care reflects broader ideological divides is one reason why assessment of the evidence is so crucial in this rather fraught field of social policy. Several points stand out from our survey of evidence on for-profit provision of paid care.

First is that the weight of evidence seems to fall on the side of critics of for-profit provision, particularly in residential aged care and in child care, and particularly in North America. However, the case against for-profit provision in any and all situations is not overwhelming, which brings us to a second point: that the distinction between ‘for-profit’ and ‘non-profit’ may be too coarse-grained. As Morris and Helburn (2000) show in their study of child care in the United States, the categories ‘for-profit’ and ‘non-profit’ can each include different kinds of organisations, such that quality outcomes do not vary entirely systematically with auspice. Further, Shmid’s study of home care for the aged in Israel (2001) shows how differences between for-profit and non-profit services can decline over time, as environmental factors and organisational learning engender a process of institutional isomorphism. Meanwhile, professionalism is a set of values and practices that can be mobilised in both non-profit and for-profit settings, and so may also mitigate differences between the performance of different kinds of organisations.

Third is that the policy context, including regulation and contracting conditions, is a critical environmental factor affecting the performance of organisations providing social care. Regulation can put a ‘floor’ under the quality of care services (and care work jobs), or fail to do so, enabling skimping on unmeasured or hard-to-measure aspects of quality. Regulation can also ‘spread the bads’ in purchaser-provider or consumer choice systems, as the dynamic consequences of competition play themselves out in pressures on providers to cut costs and to fragment and routinise care work practices. Thus, when the motivations of care providers include both intrinsic and extrinsic 36elements, policy makers need to design social service systems that enable expression of the intrinsic motivations that support quality care. This suggests that the fate of professionalism as a normative and organisational framework for maintaining and improving the quality of care is also ultimately policy-dependent.

Fourth, it seems that the care sector matters too. Evidence suggests that the impact of for-profit organisation differs in home care services compared to institutional care services for children and the elderly (specifically centre-based child care and nursing homes). Why this might be is worth further investigation.

These findings mean that the search for models of social care provision in which the quality of both care and jobs is high, and access to services is equitable, remains open—in wealthy, English-speaking democracies, at any rate. Clearly, further research and policy experimentation are required.

References

Aaronson, W., Zinn, J. & Rosko, M. 1994, ‘Do for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes behave differently’?, The Gerontologist, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 775–86.

Abzug, R. & Webb, N. 1999, ‘Relationships between non-profit and for-profit organizations: A stakeholder perspective’, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 416–31.

Aronson, J., Denton, M. & Zeytinoglu, I. 2004, ‘Market-modelled home care in Ontario: Deteriorating working conditions and dwindling community capacity’, Canadian Public Policy vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 111–25.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 1993, Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC), 1993, Cat. No. 1292.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2001, Community Services, Australia, 1999–2000, Cat. No. 8696.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra. 37

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC), 2006, Cat. No. 1292.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

Berta, W, LaPorte, A, & Valdemanis, C. 2005, ‘Observations on institutional long-term care in Ontario: 1996-2002’, Canadian Journal of Aging, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 70–84.

Brennan, D. 2007, ‘The ABC of child care politics’, Australian Journal of Social Issues, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 213–26.

Carlson, M., Gallo, W. & Brady, E. 2004, ‘Ownership status and patterns of care in hospice: Results from the National Home and Hospice Care Survey’, Medical Care, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 432–38.

Carmichael, A. & Brown, L. 2002, ‘The future challenge for direct payments’, Disability & Society, vol. 17, no. 7, pp. 797–808.

Castle, N. & Engberg, J. 2007, ‘The influence of staffing characteristics on quality of care in nursing homes’, Health Services Research, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 1822–47.

Castle, N. & Shea, D. 1998, ‘The effects of for-profit and not-for-profit facility status on the quality of care for nursing home residents with mental illnesses’, Research on Aging, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 246–263.

Cleveland, G. & Krashinsky, M. 2005, The Quality Gap: A Study of Non-profit and Commercial Childcare Centres in Canada, Toronto, Child Care Resource and Research Unit.

Davidson, B. 2009, ‘For-profit organisations in managed markets for human services’, in Paid Care in Australia: Politics, Profits, Practices, eds D. King & G. Meagher, Sydney University Press, Sydney.

Davis, M. 1993, ‘Nursing home ownership revisited: Market, cost and quality relationships’, Medical Care, vol. 31, no. 11, pp. 1062–68.

Denton, M., Zeytinoglu, I., Kusch, K. & Davies, S. 2007, ‘Market-modelled home care: Impact on job satisfaction and propensity to leave’, Canadian Public Policy, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 81–100.

Dias, J. & Maynard-Moody, S. 2006, ‘For-profit welfare: Contracts, conflicts, and the performance paradox’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 189–211. 38

Doran, D., Pickard, J., Harris, J., Coyte, P., Macrae, A., Laschinger, H., Darlington, G. & Carryer, J. 2007, ‘The relationship between characteristics of home care nursing service contracts under managed competition and continuity of care and client outcomes: Evidence from Ontario’, Healthcare Policy, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 97–113.

Dowding, K. & John, P. n.d., ‘The value of choice in public policy’, [Online], Available: http://www.ipeg.org.uk/papers/D+J_value_of_choice_in_public_policy290906.pdf [2008, Sep 10].

Drakeford, M. 2006, ‘Ownership, regulation and the public interest: The case of residential care for older people’, Critical Social Policy, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 932–44.

England, P. 2005, ‘Emerging theories of care work’, Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 31, pp. 381–99.

England, P., Budig, M. & Folbre, N. 2002, ‘Wages of virtue: The relative pay of care work’, Social Problems, vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 455–73.

Estes, C. & Swan, J. 1994, ‘Privatization, system membership, and access to home health care for the elderly’, Milbank Quarterly, vol. 72, no. 2, pp. 277–98.

Evetts, J. 2003, ‘The sociological analysis of professionalism: Occupational change in the modern world’, International Sociology, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 395–415.

Fargion, V. 2000, ‘Timing and the development of social care services in Europe’, Western European Politics, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 59–88.

Folbre, N. & Nelson, J. 2000, ‘For love or money—Or both?’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 123–40.

Forder, J., Knapp, M., Hardy, B., Kendall, J., Matosevic, T, & Ware, P. 2004, ‘Prices, contracts and motivations: Institutional arrangements in domiciliary care’, Policy & Politics, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 207–22.

Fourcade, M. & Healy, K. 2007, ‘Moral views of market society’, Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 33, pp. 285–311.

Gelles, E. 2000, ‘The role of the economic sector in the provision of care to trusting clients’, Nonprofit Management & Leadership, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 233–49. 39

Gibelman, M. & Demone, H. 2002, ‘The commercialization of health and human services: Neutral phenomenon or cause for concern?’ Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services, vol. 83, no. 4, pp. 387–97.

Gilbert, N. 2005, The ‘enabling state?’ from public to private responsibility for social protection: Pathways and pitfalls, OECD Social Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 26, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Gustafsson, R. Å. & Szebehely, M. 2009, ‘Outsourcing of eldercare services in Sweden: Effects on work environment and political legitimacy’, in Paid Care in Australia: Politics, Profits, Practices, eds D. King & G. Meagher, Sydney University Press, Sydney.

Harrington, C., Woolhandler, S., Mullan, J., Carrillo, H. & Himmelstein, D. 2001, ‘Does investor ownership of nursing homes compromise the quality of care?’, American Journal of Public Health, vol. 91, no. 9, pp. 1452–55.

Himmelweit, S. 1999, ‘Caring labor’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 561, pp. 27–38.

Himmelweit, S. 2007, ‘The prospects for caring: Economic theory and policy analysis’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 581–99.

Hirschmann, A. 1970, Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Response to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Hirth, R. 1997, ‘Competition between for-profit and nonprofit health care providers: Can it help achieve social goals?’ Medical Care Research and Review, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 414–38.

Holden, C. 2005, ‘Organizing across borders: Profit and quality in internationalized providers’, International Social Work, vol. 48, no. 5, pp. 643–53.

Kendall, J. 2001, ‘Of knights, knaves and merchants: The case of residential care for older people in England in the late 1990s’, Social Policy & Administration, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 360–75.

Kendall, J., Matosevic, T., Forder, J., Knapp, M., Hardy, B. & Ware, P. 2003, ‘The motivations of domiciliary care providers in England: New concepts, new findings’, Journal of Social Policy, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 489–511. 40

Kendall, J., Knapp, M., & Forder, J. 2006, ‘Social care and the non-profit sector in the Western developed world’, in The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, eds W. Powell & R. Steinberg, Yale University Press, New Haven.

King, D. 2007, ‘Rethinking the care-market relationship in care provider organisations’, Australian Journal of Social Issues, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 199–212.

King, D. & Martin, B. 2009, ‘Caring for-profit? The impact of for-profit providers on the quality of employment in paid care’, in Paid Care in Australia: Politics, Profits, Practices, eds D. King & G. Meagher, Sydney University Press, Sydney.

Knijn, T. & Verhagen, S. 2007, ‘Contested professionalism: Payments for care and the quality of home care’, Administration & Society, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 451–75.

Le Grand, J. 1998, ‘Ownership and social policy’, The Political Quarterly, vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 415–21.

Lynch, K. 2007, ‘Love labour as a distinct and non-commodifiable form of care labour’, Sociological Review, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 550–70.

Martin, B. 2005, Residential aged care facilities and their workers: how staffing patterns and work experience vary with facility characteristics, National Institute of Labour Studies, Flinders University.

Matosevic T., Knapp, M., Kendall, J., Henderson, C. & Fernández, J. 2007. ‘Care home providers as professionals: Understanding the motivations of care home providers in England’, Ageing and Society, vol. 27, pp. 103–26.

Matosevic, T., Knapp, M. & Le Grand, J. 2008, ‘Motivation and commissioning: Perceived and expressed motivations of care home providers’, Social Policy & Administration, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 228–47.

McGrail, K. McGregor, M., Cohen, M., Tate, R. & Ronald, L. 2007, ‘For-profit versus not-for-profit delivery of long-term care’, Canadian Medical Association Journal, vol. 176, no. 1, pp. 57–58.

McGregor, M., Tate, R., McGrail, K., Ronald, S., Broemeling, A. & Cohen, M. 2006, ‘Care outcomes in long-term care facilities in British Columbia, Canada: Does ownership matter?’ Medical Care, vol. 44, no. 10, pp. 929–35. 41

McGregor, M., Cohen, M., McGrail, K., Broemeling, A., Adler, M., Schulzer, M., Ronald, L. Cvitkovich, Y. & Beck, M. 2005, ‘Staffing levels in not-for-profit and for-profit long-term care facilities: Does type of ownership matter?’ Canadian Medical Association Journal, vol. 172, pp. 645–49.

Meagher, G. 2006, ‘What can we expect from paid carers?’ Politics and Society, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 33–54.

Morris, J. 1999, ‘Market constraints on child care quality’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, vol. 563, pp. 130–45.

Morris, J. & Helburn, S. 2000, ‘Child care centre quality differences: The role of profit status, client preferences, and trust’, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 377–99.

Nelson, J. 1999, ‘Of markets and martyrs: Is it OK to pay well for care?’ Feminist Economics, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 43–59.

Nelson, J. & England, P. 2002, ‘Feminist philosophies of love and work’, Hypatia, vol. 17, no. 2., pp. 1–18.

Nelson, J. & Folbre, N. 2006, ‘Why a well-paid nurse is a better nurse’, Nurse Economics, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 127–30.

Pearson, M. & Martin, J. 2005, Should we extend the role of private social expenditure? OECD Social Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 23, OECD Publishing.

Perry 6. 1998, ‘Ownership and the new politics of the public interest services’, The Political Quarterly, vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 404–14.

Press, F. & Woodrow, C. 2009, ‘The giant in the playground: Investigating the reach and implications of the corporatisation of childcare provision’, in Paid Care in Australia: Politics, Profits, Practices, eds D. King & G. Meagher, Sydney University Press, Sydney.

Preston, A. 1993, ‘Efficiency, quality, and social externalities in the provision of day care: Comparisons of nonprofit and for-profit firms’, Journal of Productivity Analysis, vol. 4, nos 1–2, pp. 165–82.

Rush, E. 2007, ‘Employees’ views on quality’, in Kids Count: Better Early Childhood Education and Care in Australia, eds E. Hill, B. Pocock & A. Elliott, Sydney University Press, Sydney. 42

Salaman, L. 1999, ‘The nonprofit sector at a crossroads: The case of America’, Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 5–23.

Schmid, H. 2001, ‘Nonprofit organizations and for-profit organizations providing home care services for the Israeli frail elderly: A comparative analysis’, International Journal of Public Administration, vol. 24, no. 11, pp. 1233–65.

Schmid, H. & Nirel, R. 2004, ‘Ownership and age in nonprofit and for-profit home care’, Administration in Social Work, vol. 28, no. 3–4, pp. 183–200.

Scourfield, P. 2006, ‘“What matters is what works”? How discourses of modernization have both silenced and limited debate on domiciliary care for older people’, Critical Social Policy, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 5–30.

Scourfield, P. 2007, ‘Are there reasons to be worried about the “cartelization” of residential care?’ Critical Social Policy, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 155–80.

Stone, D. 2005, ‘For love nor money: The commodification of care’, in Rethinking Commodification: Cases and Readings in Law and Culture, eds M. Ertman & J. Williams, New York University Press, New York, pp. 271–90.

Tuominen, M. 1991, ‘Caring for profit: The social, economic and political significance of for-profit child care’, Social Service Review, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 450–67.

Ungerson, C. 1997, ‘Social politics and the commodification of care’, Social Politics, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 362–81.

Wærness, K. 1984, ‘The rationality of caring’, Economic and Industrial Democracy, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 185–211.

1 Choosing a collective term for these services is not straightforward. In Australia, the term ‘community services’ was used to classify official statistics on such activities (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1993; 2001), but has recently been replaced by two terms, ‘residential care services’ and ‘social assistance services’ (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006). Our preferred alternative, ‘social care’ is more commonly used in the United Kingdom, and includes both these domains of practice. See Kendall and colleagues (2006) for an extensive definition.

2 Even parents are sometimes paid for caring for their children under, for example, personal care assistant schemes that provide cash to people with disabilities to purchase care from whomever they please, including family members. Indeed, some forms of home child care payments can be understood as ‘payments for care’ to parents of able-bodied children. Meanwhile, in many paid care interactions, a third party pays for the care services provided to the recipient: nurses are typically employed by hospitals, not patients, for example. The carer is paid, but not by the recipient.

3 Theories of the origin of profit are notoriously controversial in economics, both orthodox and heterodox. However, most economists would agree that firms seek to maximise profit.

4 Thanks to Helen Meekosha, who pointed this out at the workshop on ‘Social care for people with a disability and frail aged people: Perspectives from Australia, Scandinavia, Canada and the UK’ at the Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales, in February 2008.

5 Matosevic and colleagues (2007, p. 114) gathered data from 58 homes, of which 28 were private for-profit, 21 were voluntary non-profit, and nine were local-authority managed. Among for-profit homes, ten were small, six were medium-sized, and 12 were corporate. Among respondents, 40 were managers, four owners, and 14 acted as both manager and owner. Given the organisation types included in the sample, logic suggests that all eighteen of the owners and owner-managers operated in the for-profit sector, mostly in small and medium homes, leaving ten non-owning managers of for-profit homes, most probably in the corporate sector.