CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

ECONOMIC ISSUES IN FUNDING AND SUPPLYING PUBLIC SECTOR INFORMATION

INTRODUCTION

In May 2005, a research team began to investigate whether designing and implementing a whole-of-government information licensing framework was possible. This framework was needed to administer copyright in relation to information produced by the government and to deal properly with privately-owned copyright on which government works often rely. The outcome so far is the design of the Government Information Licensing Framework (GILF) and its gradual uptake within a number of Commonwealth and State government agencies.1 However, licensing is part of a larger issue in managing public sector information (PSI); and it has important parallels with the management of libraries and public archives. Among other things, managing the retention and supply of PSI requires an ability to search and locate information, ability to give public access to the information legally, and an ability to administer charges for supplying information wherever it is required by law. The aim here is to provide a summary overview of pricing principles as they relate to the supply of PSI.

OVERVIEW OF MAJOR INFLUENCES ON INFORMATION POLICY

In the 1990s, three particular historical developments of considerable socioeconomic significance converged to create a need to rethink many issues related to PSI. The first was that the World Wide Web was made freely available as open source software on 30 April 1993. It was a catalyst for substantial investment in web technology and a number of ideas emerged about e-government, e-democracy, e-commerce, information superhighways, information infrastructure and the like. The second was a new wave of thinking about microeconomic reform that prefaced the start of the World Trade Organization (WTO) on 1 January 1995. The WTO aimed to deal more effectively with unfair international trading practices, especially where prices of goods and services were distorted by the operation of tariffs and subsidies. The WTO agreements also re-emphasised international obligations regarding intellectual property.2 The third development was the acceptance of ideas out of the 1992 United Nations Conference on the Environment and Development (UNCED). This was an advance on earlier global

330understandings on environmental issues. Among other things, the Rio Declaration and Agenda 21 re-emphasised ideas about a human right to a decent environment in which to live and work, and a right to know about the state of the environment.

Since the 1992 UNCED Conference, progress in implementing Agenda 21 as an action plan was reviewed after five years in 1997. The United Nations saw the occasion of the new millennia as an opportune time to reaffirm its principles and goals in relation to human rights and development in its Millennium Declaration.3 In 2002, marking ten years after international commitment to Agenda 21, a further World Summit on Sustainable Development produced the Johannesburg Declaration of Plan of Implementation.4 Building on this Declaration and Chapter 36 of Agenda 21 as adopted in 1992, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 57/254. This new Resolution designated the decade 2005–14 as the ‘United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development’ (UN-DESD); and UNESCO as the lead agency to promote the education program.5 In 2005, UNESCO issued its Plan for implementing an education program to fulfil the goals of the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD). The Plan proclaimed a vision of a world where everyone had an opportunity to learn about the values, behaviour and lifestyles required to transform societies and establish a sustainable future.

Australian governments responded to the growing need for national, regional and local responses to global issues by forming the Council of Australian Governments (COAG). COAG met for the first time in 1992. One of its early commitments was an agreement to support an enquiry, and later to implement its main findings in the form of a National Competition Policy. This involved a series of agreements and mutually supportive legislative changes.6 The policy envisaged the participation of government at all levels in ensuring that publicly owned income-producing assets achieved their highest and best use by introducing competition wherever it was thought to be desirable. The policy affected a variety of infrastructure – in energy, transport, telecommunications and sanitation, for example. The concept of ‘competitive neutrality’ and the adoption of ‘accrual accounting’ methods into government financial records also opened opportunities for competition by private firms. However, it also posed philosophical issues about what should be regarded as public or private enterprise. The spectacle of competition between government agencies and private firms also posed issues of why a government enterprise needed to compete with private enterprise; and how could a government enterprise remain accountable if information was withheld under a ‘commercial in confidence’ label.

Assets affected by competition policy included land held by government; and opened the possibilities that it might find better use if leased or sold to private interests under competitive tendering arrangements. Similar ideas were thought to be applicable to managing PSI as a resource; yet the worth of PSI as a resource depends on how many people can use it to

331advantage; and people can only guess at what it might be worth to them. The conceptual and measurement problems associated with trying to value information are extensive and are not considered here. Government as a living system maintains its coordination through internal communications between its sub-systems or departments; and external communications with its operating environment. Generally, individuals – acting alone or as part of an organisation – may receive information as:

- Additions to prior knowledge – providing new ideas and new perceptions about what are opportunities and threats. Confidence in new information may vary considerably and its perceived value may be highly dependent on the reputation of its author – that is, on whether the source is seen as ‘authoritative’.

- Corroboration of existing knowledge – in reinforcing levels of confidence in existing knowledge through additional corroborative information or evidence. At some stage, increasing redundancy in information may do little to increase levels of confidence and cost more than it is worth. This exemplifies declining marginal productivity in particular information gathering processes.

- Conflict with prior knowledge – where redundancy leads to contradictions with existing knowledge and decreased level of confidence in what is known. Stocks of existing knowledge may be subject to revaluation and devaluation as a consequence.

Experience suggests that learning processes do not necessarily provide discrete incremental additions to human knowledge. In a 2007 research report concerned with the public funding of science, Australia’s Productivity Commission referred to the changing nature of science where advice was subject to significant shifts of position. Therapeutics provides an example. On its discovery, thalidomide was seen as a successful treatment for morning sickness in pregnant women. Later it was understood to cause infant abnormalities. It is currently a frontline treatment for leprosy. It is thought to have considerable potential in treating HIV and cancer.7 On this basis, the Commission argued:

The implication is that any valuation of knowledge should be seen as highly uncertain. While the apparent benefits of widespread policy adoption of research findings may be high, it raises the potential costs if the research results are actually wrong (for example, an educational policy implemented across all schools that results in poorer literacy outcomes for hundreds of thousands of children) … One of the major benefits of sophisticated research capabilities and rich feedback mechanisms between policy makers and researchers is that these uncertainties can be reduced more quickly, lowering the potential costs of mistakes – this capability has a high option value.8

Unsurprisingly, agencies that are required to provide information according to a negotiated contract with a user rather than as a predetermined service authorised by a statute, are likely to display anticompetitive and antisocial behaviours. In this way, public servants are led to deliver a public disservice. Differential pricing may be appropriate in private enterprise where professional services may be priced according to a practitioner’s assessment of a client’s ability to pay. However, the application of differential pricing in a government enterprise that supplies PSI is open to several objections: 332

- Differential pricing can only be sustained if applicants do not know what others are paying – otherwise clients can ask questions about why they are being treated differently.

- Negotiations to sustain differential pricing can only be carried out in secret at the expense of openness and accountability. The process is eminently corruptible from a public finance point of view.

- Where trading occurs at a loss, the process can be construed as channelling public resources to benefit a private entity; apart from ‘crowding-out’ competition from private firms and stifling opportunities for developing innovative services through value-adding.

- Where trading occurs at more than the marginal cost, the profits might be construed as ‘taxation’ where proper authorisation is required.

Re-use of publicly-funded information from various departments of government, and from academic and other research areas has a potential for a wide variety of combinations. The underlying rationale for this is not so much in its predictability as its unpredictability – essentially accepting the risk that new knowledge may turn out to be more beneficial than harmful. Searches for ‘missing link’ information depend on what people have learned to see and are willing to see. ‘In the fields of observation chance favours only the prepared mind’.9 In a similar vein, Drucker argued that ‘Opportunity is where you find it, not where it finds you. The potential of a business is always greater than what is actualised’.10

Enlarging the chances of systematically inviting serendipity can sensibly become an aim of government information policy. Strategy for being accident prone in a positive sense is possible; and is inherent in ideas about ‘connectionism’ that underpin the advanced use of information and communications technology in the progress of science.11 The ideas of connectionism are manifest in the systems architecture of neural networks and parallel distributed processing; and in decision support and expert systems as aspects of ‘artificial intelligence’.

On 16 August 2000, the Assistant Treasurer of the Australian Government asked the Productivity Commission to review cost recovery arrangements of Australian Government regulatory, administrative and information agencies – including fees charged under the Trade Practices Act 1974 (TPA).12 The Commission produced two documents dated 16 August 2001- the final report;13 and proposed information agency guidelines.14 In a joint media statement of

33314 March 2002, the Treasurer and the Minister for Finance and Administration announced the release of the Commission’s final report together with the government’s interim response to the report’s recommendations.15

Among other things, the Productivity Commission found:

- Many cost recovery arrangements lacked transparency and accountability.

- Accounting data often failed to separate cost recovery receipts from other revenues.

- The objectives and rationale for many arrangements were difficult to establish.

- Regulation Impact Statements usually assessed regulatory proposals without dealing directly with cost recovery issues.16

The Commission’s recommendations numbered 3.1 and 3.2 are especially relevant in discussions on charges for PSI:

Recommendation 3.1

All cost recovery arrangements should have clear legal authority. Agencies should identify the most appropriate authority for their charges and ensure that fees-for-service are not vulnerable to challenge as amounting to taxation.

Recommendation 3.2

Revenue from the Commonwealth’s cost recovery arrangements should be identified separately in budget documentation and in the Consolidated Financial Statements. It should also be identified separately in each agency’s Annual Report and in Portfolio Budget Statements.

The Commission’s report drew particular attention to the need for formal authority if an agency is to charge for PSI. Constitutionally, the levying of compulsory taxes and charges is a sole prerogative and a duty of a legislature that represents the people who are called on to pay. Authorisation is needed to produce PSI legally since it involves an appropriation of public funds that may occur on a continuing basis. Authorisation is also needed to supply PSI legally – partly to clarify what may be disclosed legally, and especially so if the charge for supplying information exceeds its marginal cost and profits accumulate as consolidated revenue. Such a consolidation might be construed as a form of taxation by the executive arm of government without consent of the legislative arm of government and contrary to the government’s constitution.

A further issue arising from the Productivity Commission’s report is the regulatory impact of charging and whether it is properly integrated with all of the things that governments try to do. In this regard, conventional benefit-cost analysis seems to be inadequate and an approach oriented towards operational research seems to be more promising. This approach would need to have a proper regard for the technical, cognitive and behavioural aspects of producing and supplying information. It also needs to consider the reasons for producing the information in the first place; whether there are clusters of activities where the information might be useful; and whether there is potential for synergy. Perhaps this can be a direction for future research to

334provide a rationale for funding the production of information and the standards to be adopted in its production.

PROBLEMS WITH SEEMINGLY SIMPLE IDEAS

Some ideas are easy to adopt as political slogans because they sound simple. However, under Socratic-style enquiry they often pose more questions than they answer in trying to work out what they actually mean and whether they have any practical application. In relation to PSI and the role of government, the following ideas seem to have particular relevance.

- ‘No taxation without representation’ – a political slogan of considerable significance historically, which opens a series of questions:

– Who actually pays taxation when it is possible that some or all of the cost may be passed on in value-adding processes of intermediate product leading to final consumer goods and services?17

– Who can be said to own cultural heritage and the benefits that flow from it, having regard to parts of this heritage that may be global, regional or local in its significance?

– Are things such as changes in property rights regimes,18 conscription for military service;19 and the so-called ‘red-tape burden’ properly compensated or can they be construed as forms of taxation where people deserve to be properly represented individually and collectively?

– What does it mean to be represented? This has been resolved historically for the most part in favour of adult suffrage in elections for representative legislatures that have an important constitutional responsibility to decide how government revenue is raised and how it is appropriated.

- The ‘user pays’ principle – which opens a series of question regarding:

– Who can be identified as a user?

– If users can be identified how much should they should pay?

– Who should be paid within the framework of copyright law? The issue is often complicated by remnants of copyright that may subsist within PSI. It is difficult in practice to organise ‘equitable remuneration’ under copyright law. Part of the problem is in knowing when remuneration is due, given the uncertain boundaries of what is information per se and not subject to copyright, and what is not subject to remuneration under the ‘fair use’ provisions of copyright law.

– If payment is in fact due, how can a particular remuneration be properly called ‘equitable’?

– How can payments be effected and how much does it cost to effect these payment transactions? 335

- The proposition that information is an investment that should provide a return on capital opens a series of questions.

– What is the value of information – bearing in mind that things are not necessarily worth what they cost?

– What is the quality of information that might help to determine whether it is useful to anyone? In asking about the quality of information it is also possible to ask about the qualifications of the assessors and who assesses the assessors.

– How can a stock of information be valued, how can it be decided what information is worth as flows of current revenues and costs, and what can be said meaningfully about return on investment?

– If ‘maximising’ the use of PSI is an aim of public policy, how can it be decided that use is ‘maximised’?

In considering the multifaceted nature of these questions, leaving some of them unanswered might appear to be convenient. However, ignoring them will almost certainly pave the way for valid objections to a partial analysis. Alternatively, a single author who tries to address all of these questions will certainly extend beyond a personal level of expertise and leave room for valid objection by those who do have more expertise. In failing to view the issues holistically, opportunities to veto proposals arise in many places with a consequence that institutional innovation is especially difficult to achieve when it relates to how people are governed.

STRUCTURING OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS

In July 2007, research began into circumstances where charging for PSI is or may be appropriate. These questions are easy to ask and the answers can often be given simply. However, providing reasons for the decisions can be more difficult. The ability and willingness to provide reasons is important in matters of administrative justice and is the essence of what it means to be reasonable. Being recognised as reasonable underpins the legitimacy of a government in that it helps to develop an informed consent of the governed in supposedly democratic societies.

A further fundamental issue is where does formal authority originate that can describe any activity as ‘legal’ or ‘illegal’ and ‘legally enforceable’, and what are the learning processes that allow people to work and live in conformity with the laws. The following issues were deemed important in trying to review holistically the information-intensive activities of government:

- fundamental purposes of government and why a government needs information;

- how a government gives purpose and authority to its production of information;

- what conditions should apply to the supply of information between government agencies, other governments and private persons; and

- the development of a rational basis for deciding how much should be paid, who should pay, and how payments can be collected.

SUMMARY OF PRICING PRINCIPLES

The pricing principles that emerge from the research are summarised in Box 1. They depend on the nature of the transactions involved that may be summarised as: 336

No charging – Non-contractual supply of public sector information to anyone.

Charging – the circumstances can be considered as:

- Supply of information by command of a statute to anyone who is entitled to receive it.

- Inter-agency transfers and exchanges within a government as a single legal entity.

- Transfers from and exchanges between a government as one legal entity in dealing with other governments or statutory authorities as separate legal entities.

- Supply of information under terms of a contract with a private person.

Box 1 – Summary of pricing principles

No charging

- No charge should be made for government information where the government has objectives of informing the public; obtaining information from the public; or securing public cooperation and community engagement.

- No charge should be made in circumstances where people are able to re-use existing government information for lawful purposes at a negligible cost to the government.

- Costs to the government should be regarded as negligible where information is supplied online in a digital format; no representation is made that the information is suitable for any non-government purpose; and access is not restricted by any requirements for privacy or confidentiality.

Charging in some situations for services that provide information

- A charge should be made to conform to a prescribed fee for service as set out in an Act or associated regulation when information is supplied to meet statutory duties and standards of service.

- Important issues of public policy arise in going beyond prescribed statutory duties and using public resources to service the particular needs of a private person, firm or organisation for information or advice. Consequently, decisions about charging need to be well informed in relation to the political and economic risks involved. Without attempting to be exhaustive, things that need to be considered include:

– A liability regime that compares to private professional practice.

– A need for openness and accountability in pricing.

– A potential for profit-making to be construed as a form of taxation that should have parliamentary approval.

- A potential for non profit-making to be construed as failing to comply with competitive neutrality provisions and a crowding-out of private sector initiatives.

- A charge may be negotiated for work needed to achieve interoperability and cooperation between the government’s own agencies to meet its own purposes. Generally, details of the proposed work and inter-agency transfers of money and information should be recorded in a memorandum of understanding.

A charge may be negotiated for work needed to achieve interoperability and cooperation between governments. The arrangements should be properly set out in an inter-governmental agreement. 337

Information produced expressly by command of the parliament often provides information or evidence to satisfy needs of individuals and corporations. The enabling statutes may specify standards of service; rules about the government’s liability, rules regarding access, details of the licence pertaining to use of information, and the basis for charging for the service. Supply of information by command of the parliament cannot be construed sensibly as market place transactions.20

The arguments related to charging for public sector information are generally based on grounds of efficiency and fairness perceived broadly as follows:

- Efficiency – that may include issues such as effectiveness and synergy in achieving the purposes of government, administrative simplification, and the proportion of transaction costs associated with collecting revenue compared to the amount of revenue raised and the net revenue after collection.

- Fairness – that may include issues such as redistributive justice, administrative simplification and transparency, and the giving of reasons consistent with requirements for social cohesion.

EFFICIENCY CONSIDERATIONS

Generally, highly aggregated macroeconomic efficiency indicators do not identify information-intensive activities in ways that can inform information policies at an operational level.21 The microeconomic concepts that are usually associated with a package of microeconomic reform in market oriented activity provide a useful starting point. These concepts can be summarised as follows:

- Technical or x-efficiency – where efficiency improves if the same input can achieve greater output. Improving technical efficiency depends significantly on operational analysis. Some economists and textbooks do not acknowledge ‘x-efficiency’ as a concept, but others relate it to motivational factors and work output of human beings.22 Government responses are generally specific to industries and sectors and related to production methods and standards.

- Pareto or allocative efficiency – where efficiency improves when people can trade to mutual advantage without harming anyone else. This idea underpins much of the theory about the efficacy of markets; but the idealised circumstances are seldom approximated as a matter of practice. Equally simplistic is the idea that governments can readily intervene to correct perceived market imperfections.

- Dynamic or adaptive efficiency – where efficiency improves when resources are readily adaptable to new tasks.

In adapting market-oriented microeconomic efficiency concepts to the command type activities of public and private bureaucracies, some relabelling occurs to identify ideas about ‘efficiency’

338and ‘effectiveness’. While there is no formal acceptance of the meaning of some of these terms, a useful translation is as follows:

- Efficiency – doing things the right way – which aligns more or less with the microeconomic concept of technical efficiency.

- Effectiveness – doing the right things – where market-oriented processes of allocation are replaced by the collective decision making and appropriations made by a representative legislature.

According to a Pareto Criterion, overall economic welfare increases if one person can be made better off without making someone else worse off. Conceptually, a Pareto optimum can be reached when no further transactions meeting the Criterion can be negotiated. At this stage, commodities reach their highest and best use as indicated by market prices. This basic argument is tautological: a logical construct that says that things get better if nothing gets worse. Nonetheless, it underpins policies that favour free trade; and its practical importance lies in whatever influence it can give in trying to create social and economic conditions where there are winners and no losers.

The Pareto Criterion is subject to several qualifications. It assumes that a person is the best judge of his or her own welfare; and that parties are free from coercion in arriving at their decisions. An individual might not be the best judge of his or her own welfare if he or she is:

- intellectually immature or mentally handicapped;

- displaying obsessive or addictive behaviours – as in alcohol or drug dependence and gambling;

- seeking technical or professional advice either as a discrete service such as a medical consultation or as part of a larger overall objective such as financial advice on investment opportunity; or

- making purchase decisions under various degrees of uncertainty and involving elements of risk – a condition that applies to most long term commitments.

People need to understand how they might be satisfied in their transactions with other people; but just as important is how dissatisfaction can be managed if things do not turn out as expected. Accordingly, the need for learning underpins all efficiency considerations in a path to improved standards of living; regardless of whether decisions are made as individuals or collectively. Where knowledge is deemed to be a driver of technological progress, more attention ought to be directed to encouraging ‘knowledge production’ as a process where an individual learns something of value that he or she did not know previously.23 The application of knowledge to tasks, especially those that are non-routine and do not lend themselves readily to automation, requires a special kind of productivity in knowledge workers. In commenting on this issue, Drucker wrote:

The productivity of knowledge and knowledge workers will not be the only competitive factor in the world economy. It is, however, likely to become the decisive factor, at least for most industries in the developed countries.24

339In 1986, the UN adopted a Declaration on the Right to Development that referred to the idea of ‘sustainable human development’.25 In 1996, Stiglitz referred to the World Bank’s change of focus in financing economic development.

We now see economic development as less like the construction business and more like education in the broad and comprehensive sense that covers knowledge, institutions, and culture.26

Some commentators consider knowledge as a distinctly human attribute linked to the notion of ‘human capital’. In practice, a great deal of learning occurs in non-market conditions as indicated by the large volumes of information sharing that occur in practice.27 It is perhaps more precise to speak in terms of one-way communications as ‘transfers’ and two-way sharing of information as ‘exchanges’. Some learning may be pre-contractual insofar as people need to gain sufficient mutual understanding to form the basis of political or market-oriented agreements and contracts.

DEVELOPING EFFICIENCY IN LEARNING PROCESSES

Democracy depends on continually learning how to develop understandings and agreements that can sustain voting majorities on which democratic law making and collective action depends. The objective expressed in constitutional terms is to deliver ‘peace, order and good government’. The requirement to meet this objective is a collective intellectual authority that can understand what is possible; and a collective moral authority to understand what ought to happen in practice.

Facts of life determine that a society needs to retain its collective competence despite a continual turnover of its membership as people die but life goes on. Retaining this ‘collective competence’ in matters of self-government depends on each new generation:

- acquiring a collective knowledge of how to produce goods and services needed to sustain a society and its capacity for self-government;

- learning how to defend society diplomatically and militarily in relation to external forces to prevent overthrow of its self-governing capacity; and

- learning how to defend society against divisive internal forces to preserve the authority of representative legislatures, allow peaceful dispute resolution and maintain social cohesion.

340Societal continuity depends on institutional arrangements that allow cultural, genetic and material inheritances to pass from one generation to the next. Table 1 contains a brief description of these inheritances:

| TABLE 1: KEY INHERITANCES FOR SOCIETAL CONTINUITY | ||

| Cultural | Genetic | Material |

| Inherited in learning how to organise productive activities, distribute goods and services equitably, live peacefully, and find satisfaction and purpose in life. Benefiting from this cultural heritage depends on acquiring relevant language skills. | Inherited through birth. Genetic adaptation to changes in environmental conditions occurs slowly. In comparison, cultural adaptations happen more rapidly and provide capacity for both survival and for self-destruction | Inherited in natural and man-made resources, including the physical inheritance of meaningful symbols, objects and places. (Knowing how to recognise and use material things as resources is part of the cultural heritage). |

Although all societies aim to ensure their survival through continuity with the past, some societies also learn to expect future improvements in their standards of living. A society merely maintains its standard of living by knowing how to produce the same goods and services with less labour. Living standards do not improve until societies learn how to:

- redeploy human and other resources displaced by increased productivity in one area into new areas of production;

- overcome problems associated with disinvestment – especially in facilitating education and training of workers for new jobs; and, wherever necessary, in facilitating their movement to new places so they can live in reasonable proximity to their new jobs;

- relieve social tensions arising from unequal distribution of the benefits, costs, opportunities and risks associated with new technology, so far as this is practicable;

- acquire the language, understandings and agreements related to property, contract, liability, warranty and other institutional arrangements that allow proper use of new technology; and

- acquire the ability to regulate and mitigate the adverse consequences arising from abuse of new technology.

Viewed holistically, society relies on organisations in government, commerce and civil society sectors to produce most of its goods and services. In retrospect, these sectors have existed in some form since medieval times, and perhaps longer. Each is distinguished by how it accesses resources when engaging in processes of routine production and innovation. Each is also affected differently when innovations in information and communications technology remove constraints on its organising capabilities. Table 2 contains a brief description of these sectors: 341

| TABLE 2: PRODUCTIVE ORIENTATION IN MAJOR SECTORS OF SOCIETY | ||

| Government | Commerce | Civil Society |

| Activities whose authorisation and funding through compulsory taxes, levies and charges depends on decisions by a representative legislature. | Activities where survival of firms depends on capital raisings, profits and loans obtained from people with some degree of choice about whether or not they deal with the firm. | Activities of not-for-profit organisations that depend on subscriptions, fees for service, gifts, grants and in-kind contributions to retain financial solvency. |

Information asymmetry is inescapable in an information society based on task specialisation. Conceivably, a supplier of goods or services may have a purchaser’s interests in mind, and continuing business may find its basis in reputation for fair dealing. In these circumstances, ‘fair dealing’ contributes to economic efficiency. Thus, fair dealing can occur despite practical difficulties and any shortcomings there may be in arriving at ‘informed consent’. However, dealings that are perceived as unfair lead to less efficient outcomes: in things such as reduced satisfaction from transactions, loss of trust and reputation in suppliers, increased costs in surveillance and recourse to civil or criminal legal actions. Ethical dealing needs to underpin human interaction quite generally and avoid undue exploitation of people who are in weak bargaining positions. Williamson refers to ‘opportunism’ as ‘self-interest seeking with guile’; where transactions occur with some element of deceptive behaviour though non-disclosure of important information and with ‘lying, stealing and cheating’ as its more blatant forms. However, more subtle forms are recognisable as adverse selection and moral hazard that he relabelled respectively as ex ante and ex post opportunism.28

The increasing need imposed by laws of negligence and a duty of care to obtain ‘voluntary informed consent’ places particular obligations on the parties to maintain some in commercial transactions and where the government seeks to engage the community in debate on policy proposals. Improvement depends on:

- Encouraging experts to do whatever they can to make their work more understandable to other people through activities such as:

– Facilitating multidisciplinary teamwork based on clear objectives where experts can learn to work together.

– Facilitating access to information generally – and public sector information in particular, insofar as it relates to the authority, planning and monitoring regimes associated with the functioning of government.

– Producing summaries and versions of research findings that are more particularly directed towards the eventual need for voluntary informed consent where matters of public policy are concerned.

– Promoting non-aggressive interviewing technique in forums and discussion through the mass media that allow experts to demonstrate positive aspects of scientific curiosity and questioning rather than blind acceptance of particular points of view. 342

- Encouraging people to do whatever they can to increase their knowledge generally; and their capacities in particular for:

– continuity in employment;

– community engagement in programs such as those that maintain health, public safety and the human habitat; and

– contributing meaningfully to policy developments and debates in a participative democracy.

In the 1990s, attention turned towards lifelong learning as a feature of a ‘learning society’ and a ‘knowledge economy’ with increasing concerns about potential for underemployment and limits to remuneration despite educational attainments.29 In encompassing all these themes, UNESCO’s Fifth International Conference on Adult Education, held in Hamburg in 1997, produced two documents:

- ‘The Hamburg Declaration on Adult Learning’ as a statement of principle

- ‘An Agenda for the Future’ as a statement of intended actions.30

Aging populations introduce a new dimension in coping with complexity. Older people are able to participate in things that affect them; and their worldly experience can influence the development of an informed and tolerant citizenry. This is at least useful and may be a necessary condition for humanity’s survival. Long-term strategies for retirement incomes also pose significant social problems in knowing how to provide future incomes in the face of increasing vulnerability in socio-economic and ecological systems. The problem is not merely to provide incomes into the future but also to maintain their purchasing power and the solvency and survival of financial institutions that actually manage retirement savings.

The OECD has also expressed interest in the kinds of policies that can promote adult learning as older workers may need to work beyond what has been accepted as a retirement age. This tends to emphasise the needs for low-skilled workers to engage in continuing education to retain their opportunities for employment and their inclusion in the affairs of society. The relationship of education to employment has been followed for the most part in Australia in terms of where the payoffs are expected to be.31

In summary, governments have not always seen PSI as learning material; yet many worthy publications are publicly funded. Accordingly, public policy is inconsistent, incoherent, inefficient and ineffective when: 343

- governments promote activities associated with education, training, research, public libraries and archives at considerable cost in the hope that individuals will be able to use the information for personal and social advantage; and

- governments fail to promote opportunities associated with re-use of public sector information on an as-is basis when it can be achieved at minimal cost to government.32

EQUITY ISSUES

In a broad sense, allocation processes are corrupted when someone obtains benefits or incurs costs or penalties that they do not deserve. The benefits and costs may be political – as in gains in political power or losses of personal freedoms; or economic – comprising gains or losses that are usually reckoned in money terms. These misallocations usually occur through dishonesty in the information processes associated with deciding how rewards and penalties are to be applied.

The term ‘official corruption’ usually applies in the regulatory processes of government. However, it is a special case of a more general problem of governance where information asymmetry provides a potential for adverse selection and moral hazard – in relationships of employees vis-à-vis employers; company executive officers vis-à-vis shareholders; agents vis-àvis principals, for example.

The ideal of mutual advantage in undertakings according to the Pareto Principle is not always available in practice. In many cases, there are winners and losers; and losers go uncompensated due to the practical difficulties and transaction costs associated with trying to compensate them. However, where there are sufficient opportunities for people to have gains and losses at various times, the notion of compromise and ‘give and take’ becomes a part of everyday life. The problems arise if there are systematic attempts to allow the rich to get richer at the expense of poorer people. In this regard, the problems for a highly organised society is not only to distribute benefits of successful enterprise but also how to distribute the risks that things may turn out badly and the actual costs if insolvency actually occurs.

Limited liability became more widely available in the UK after 1855 through an amendment to the Joint-Stock Companies Act of 1844. The amendment followed a Royal Commission that canvassed strongly divergent attitudes towards limited liability and its implications for commerce and manufacturing. Historians tend to see the 1855 amendment as a sharp break with the past and that subsequent changes have been more gradual. However, few seemed to agree on why the change occurred. Bryer cites earlier work by Jefferys with approval in arguing that:

the success of the industrial and commercial revolutions had resulted in London and other commercial centres in the growth of a body of capitalists not directly engaged in trade, who were now seeking an outlet, with profit, for their accumulations. The National Debt, savings banks, the practice of joint stock banks in allowing interest on deposits, the canal and railway investments, had increased their numbers and had whetted their appetite for investment at a profit … This class were the chief instigators of the limited liability legislation.33

344Nowadays, commercial interests often emphasise the role of markets and private enterprise in undertaking ventures involving risk. However, they fail to mention laws that act in their favour since most firms are corporate entities whose shareholders benefit from limited liability. Similarly, laws regarding personal insolvency have evolved:

- initially out of situations where creditors took matters into their own hands;

- then to imposition of severe penalties and confinement in debtors’ prisons – usually at the behest of creditors; and

- then to situations where governments have tried to organise the best arrangement that circumstances allow; usually involving

– some forgiveness of the debt;

– attempts at rehabilitating the debtor; and

– trying to effect the best settlement that can be obtained for creditors.34

Limited liability as an institutional arrangement is an intangible investment in collective learning about how to manage business risks. Production in the latter part of the 1800s and into the 1900s entered a new phase as research into manufacturing processes began to yield significant productivity improvement. Tools were used to make other tools and machines could make parts for other machines. Since economies of scale depended on scale, mass production was unsustainable without mass consumption. That depended in turn on increases in actual purchasing power through wages and tax redistribution to working people, or through personal savings, or through access to consumer credit that could create an illusion of purchasing power. Mass consumerism also depended on a mass media that was highly dependent in turn on advertising revenue, and increasing consumer literacy and learning.

Arguably, the organisations of government, commerce and civil society share the same tendencies to bureaucratisation. Ownership and control are separated; and executive decisions replace market-style negotiations in the internal allocation of resources. The market power of large producers; their employment of human resources; and their reliance on public infrastructure means that company spokespersons acquire significant bargaining power in their threats to withdraw production from particular geographic locations and to reduce local employment. The abuse of this power is often a corrupting influence in the decisions affecting allocation of resources.

Equity issues become intimately bound up with a potential to manipulate information. Posing alternative views becomes a countervailing force to chicanery as complexity grows and things become more difficult to understand. It may be sufficient here to say that charging for PSI is an unnecessary barrier to self-motivated learning in all its forms; and an unnecessary complication in public administration where better use can be made of the resources tied up in this activity.

CONCLUSION

The role of government has become increasingly complex and efforts are needed to simplify its organisation without being unduly simplistic. Einstein adopted an adage – ‘Things should be as simple as possible but no simpler’. Communities need to place increasing attention on how they can cope with the complexity of their own self-government if they are to open opportunities for

345the benefits of technology to emerge while also coping with the potential for harm caused by abuse of technology. Experts ought to feel some obligation to explain the implications of what they know if there is to be informed consent in personal services and collective decision making. The people affected by these decisions ought to feel some obligation to understand how they are governed and satisfy themselves in relation to information that is readily available. These are essential processes in ‘learning societies’ and ‘knowledge economies’. Stable democracies depend on being able to sustain workable majorities in relation to important public policy initiatives to gain genuine community support for collective actions.

The supply of PSI at no charge is generally justifiable on grounds of economic efficiency where there are no clear obligations and risks related to nondisclosure. The arguments related to equity and ‘user pays’ are usually poorly conceived in the context of the public funding and the strenuous efforts devoted to the promotion of lifelong learning. Moreover, the contribution of resources to learning occurs in all sectors – government, commerce and civil society – and much of the contribution is voluntary.

The equity arguments are also poorly conceived in relation to the massive redistributions that occur through limiting liability in dealing with personal and company insolvency. The debts can be distributed locally and globally to impose on people who can ill-afford the losses. The need for redistribution of income and wealth is important to social stability and is achieved for the most part through differential taxation, transfer payments for social welfare purposes and through the not-for-profit organisations of civil society. Where the government has multiple sources of charges, the chances are that the government will be seen as giving with one hand and taking away with the other.

Where there are few certainties about what the future will bring, two things provide a sense of intellectual and moral solidarity. The first is that people can expect to be treated fairly and reasonably under the institutional framework that supports society. The second is that people will avail themselves of opportunities for self improvement in matters of health and education to maintain their physical and mental capacities and enjoy various pleasures of life that money cannot buy; and also feel some obligation to assist other people who may need help.

ATTACHMENT 1: SUMMARY OVERVIEW OF GOVERNMENT ACTIVITIES

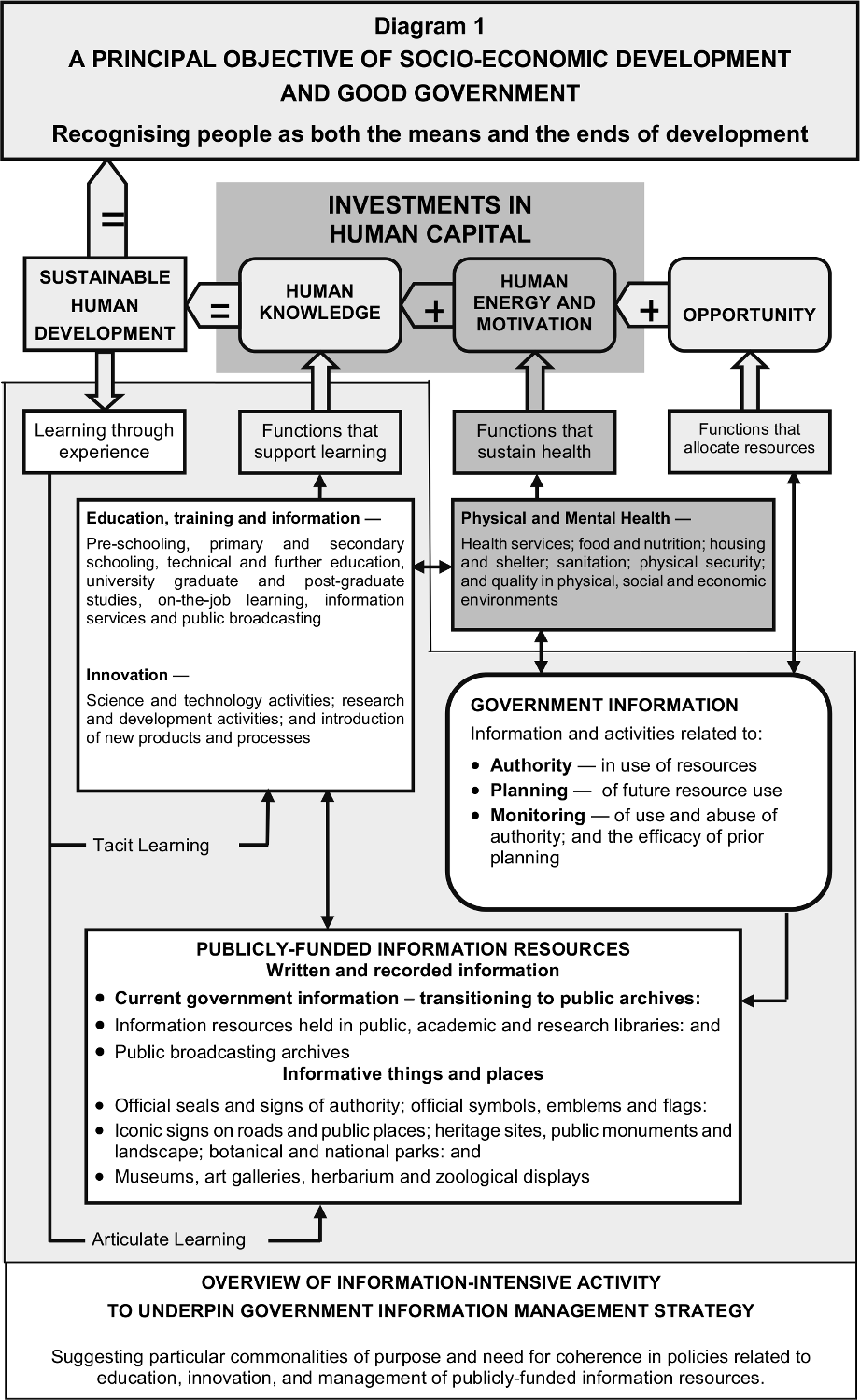

Arguably, the complexity of government needs to be simplified for the purpose of giving an overview of the whole of government for management purposes. Diagram 1 is designed to highlight the learning processes involved in developing human capital. 346

ATTACHMENT 2: STRUCTURING OF INFORMATION TO ACHIEVE GOVERNANCE

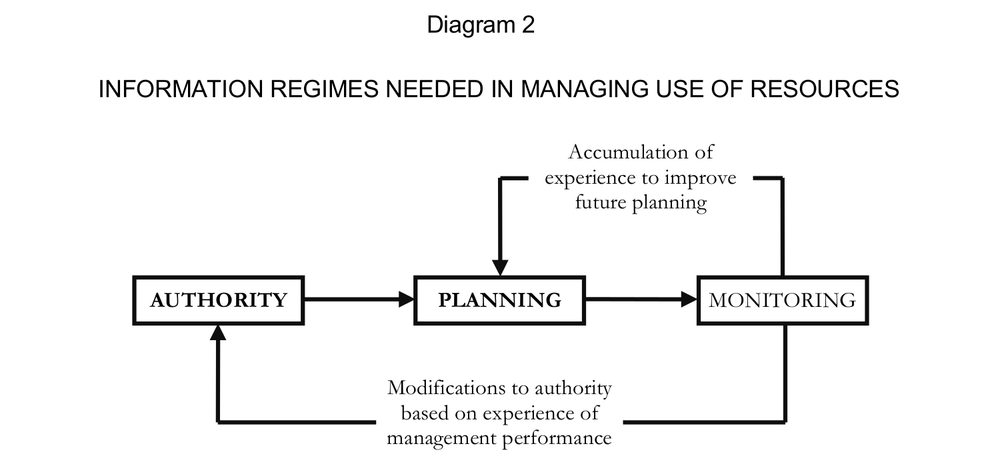

In establishing governance arrangements, most government and non-government enterprise depends on three information-intensive activity regimes:

- an authority regime – involving the creation of a legal framework of legally enforceable rights and obligations pertaining to ownership, transfer, exchange and use of resources;

- a planning regime – to establish the foresight on which to base future actions that involve use of resources; and

- a monitoring regime – to accumulate experience or hindsight on which planning depends, and to monitor performance on which continuing authority may be justified.

Diagram 2 shows the information bundling associated with resource management and the nature of the feedback processes known variously by terms such as ‘learning though experience’, ‘learning by doing’, and ‘evidence-based decision making’. Arguably, this provides a basis for ‘information infrastructure’ insofar as it relates to information as content.

Much depends on the availability, quality and readability of this information by all who are affected by what governments do. Opening this information to research and critique by anyone who has the motivation to use it increases the potential for improving human capital and the quality of encoded information held as records by government departments.

ATTACHMENT 3: EDUCATION OBJECTIVES

Education objectives were affirmed as a global issue in the aftermath of two World Wars interspersed by a fragile peace. Delegates to a conference held in London on 16 November 1945 agreed to constitute the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) as a specialised agency of the UN as permitted by the UN Charter.35 Australia accepted the Constitution on 11 June 1946. The Australian Parliament approved this acceptance formally in passing the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Act 1947.36 The UNESCO Constitution captured the prevailing ethos of leading nations in declaring with power and eloquence:

- that since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed;

- that ignorance of each other’s ways and lives has been a common cause, throughout the history of mankind, of that suspicion and mistrust between the peoples of the world through which their differences have all too often broken into war;

- that the great and terrible war which has now ended was a war made possible by the denial of the democratic principles of the dignity, equality and mutual respect of men, and by the propagation, in their place, through ignorance and prejudice, of the doctrine of the inequality of men and races;

- that the wide diffusion of culture, and the education of humanity for justice and liberty and peace are indispensable to the dignity of man and constitute a sacred duty which all the nations must fulfil in a spirit of mutual assistance and concern;

- that a peace based exclusively upon the political and economic arrangements of governments would not be a peace which could secure the unanimous, lasting and sincere support of the peoples of the world, and that the peace must therefore be founded, if it is not to fail, upon the intellectual and moral solidarity of mankind.37

The preamble to the UNESCO Constitution expresses a belief in ‘full and equal opportunities for education for all’; ‘the unrestricted pursuit of objective truth’, and ‘the free exchange of ideas and knowledge’. UNESCO’s purpose was centred on improving communications between people to develop deeper mutual understandings that could promote international peace and the common welfare of mankind consistent with the UN Charter.

The General Assembly adopted and proclaimed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) on 10 December 1948. Member States pledged themselves to cooperate with the United Nations in promoting universal respect for fundamental human rights and freedoms. These rights included a right to an adequate standard of living and social security in Articles 22 and 25; a right to education in Article 26; a right to work and to equal pay for equal work in Article 23; and a right of minorities to enjoy their own culture, religion and language.

The notion of a right to share in the benefits of science appeared at Article 27 of the UDHR.38

349Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.39

The Declaration also envisaged progressive national and international measures to improve the quality of life for all people in the world. The 1976 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights reasserted provisions of the 1948 Declaration by calling on parties to the Covenant to recognise the right of everyone to take part in cultural life, enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications, and benefit from ‘the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author’.40

Everyone has a right to an education; with free and compulsory education at elementary and fundamental stages; and accessibility to higher education ‘equally available to all on the basis of merit’.41 The UNESCO Constitution affirmed a basic tenet of humanistic philosophy in suggesting that:

Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.42

1 The GILF website is accessible online at www.gilf.gov.au and contains information and documents pertaining to the history of the project.

2 Documentation related to WTO membership is extensive. An Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) is set out in Annex 1C to the Marrakesh Agreement. Under TRIPS, members of the WTO are required to adopt particular minimum standards regarding intellectual property.

3 United Nations, Millennium Declaration, adopted by General Assembly Resolution 55/2 of 8 September 2000, accessed at www.un.org/millennium/summit.htm on 17 August 2008. Further discussion on this issue appears in Section 3.2.1.7

4 UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Sustainable Development, Johannesburg Plan of Implementation, proceedings of World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) held at Johannesburg, South Africa from 26 August to 4 September 2002, accessed 11 April 2009 at www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/

WSSD_POI_PD/English/POIToc.htm.

5 United Nations, General Assembly Resolution 57/254 of 20 December 2002, United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development, accessed online at www.un-documents.net/a57r254.htm

6 These agreements are reproduced by the National Competition Council as Part 1 in Compendium of National Competition Policy Agreements, 2nd edn., accessed at www.ncc.gov.au/pdf/PIAg-001.pdf.

7 Productivity Commission, Public support for science and innovation, Research Report, Canberra ACT: Australian Government, 9 March 2007, p. 171.

8 ibid.

9 The original expression, attributed to Louis Pasteur, is Dans les champs de l’observation le hasard ne favorise que les esprits préparés. The above translation is one of a few commonly cited translations.

10 Peter F Drucker, Managing for results, London UK: Pan, 1964.

11 ‘Connectionism’, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, first published 18 May 1997, substantially revised 8 March 2007, accessed online at URL www.science.uva.nl/~seop/entries/connectionism/ on 10 March 2008.

12 Rod Kemp, Assistant Treasurer, Terms of Reference, 16 August 2000, reproduced in Productivity Commission, Cost recovery by Government agencies, Report No.15, Australian Government: Canberra ACT, 16 August 2001, pp. iv-v accessed at URL www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/36877/

costrecovery1.pdf.

13 ibid., in main report.

14 Productivity Commission, Cost recovery by government agencies, Part 2 – Proposed information agency guidelines, Report No.15, Australian Government: Canberra ACT, 16 August 2001, accessed at URL www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_

file/0009/36882/costrecovery2.pdf.

15 Senator Nick Minchin (Minister for Finance and Administration); and Peter Costello (Treasurer), Release of the Productivity Commission Report on Cost Recovery by Government Agencies and the Government’s interim response to the report, Media release 11/02, 14 March 2002, www.financeminister.gov.au/media/2002/

mr_1102_joint.html.

16 ibid.

17 Economists usually refer to this as ‘the incidence of taxation’.

18 In particular, changes regarding permitted uses and obligations regarding natural and cultural heritage that impact adversely on property values.

19 The movement towards adult suffrage accelerated in the aftermath of the Napoleonic conflict and the first and Second World Wars.

20 The supply of information by land registration authorities is archetypical of these kinds of transactions.

21 This apart from the considerable conceptual and measurement problems associated with accounting for information-intensive activity.

22 An early article is due to Harvey Leibenstein, ‘Allocative efficiency vs. ‘x-efficiency’,’ American Economic Review, 56: 3, June 1966, pp. 392–415. Some economists apply the notion of technical efficiency mainly to machines and work methods. Others relate the notion of x-efficiency to human factors such as motivation, incentives and disincentives.

23 Fritz Machlup, Knowledge: its creation, distribution and economic significance, Vol.1 ‘Knowledge and knowledge production’, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1980, p. 7

24 Peter F Drucker, ‘The future that has already happened’, Harvard Business Review, September-October 1997, p. 21, cited in Thomas H Davenport, Thinking for a living: how to get better results from knowledge workers, Boston MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2005, p. 8. Further commentary on this theme appears in Peter F Drucker, ‘Knowledge-worker productivity: the biggest challenge’, California Management Review, 41: 2, 1999, pp. 79–94.

25 Declaration on the Right to Development, adopted by General Assembly Resolution 41/128 of 4 December 1986, at Article 2(1) – ‘The human person is the central subject of development and should be the active participant and beneficiary of the right to development’ - accessed at URL www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/74.htm.

26 Joseph E Stiglitz, Senior Vice President and Chief Economist of the World Bank, ‘Public policy for a knowledge economy’, Keynote address in The knowledge driven economy: analytical and policy implications, held by Department for Trade and Industry and Centre for Economic Policy Research Conference in London, UK on 27 January 1999, p. 3, accessed at www.worldbank.org/html/extdr/extme/knowledge-economy.pdf

27 Accordingly, a great deal of ‘knowledge production’ occurs outside traditional financial accounting procedures and is not measured and actually defies measurement.

28 Oliver E Williamson, The economic institutions of capitalism, Free Press - Macmillan: New York NY, 1985, p. 47.

29 D W Livingstone, ‘The limits of human capital theory: expanding knowledge, informal learning and underemployment’, Policy Options, July-August 1997, pp. 9–13, accessed online at URL www.irpp.org/po/archive/jul97/livingst.pdf.

30 UNESCO, ‘The Hamburg Declaration on Adult Education’ and ‘An Agenda for the Future’, Conference documents, CONFINTEA held at Hamburg from 14 - 18 July 1997 accessed at URL www.unesco.org/education/uie/confintea/pdf/con5eng.pdf.

31 Tom Karmel and Davinia Woods, Lifelong learning and older workers, National Centre for Vocational Education Research, Adelaide SA, NCVER, 2004, accessed online at URL www.ncver.edu.au/research/core/cp0303_2.pdf.

32 The diagram in Attachment 1 is an attempt to provide a graphic overview of learning processes that are important to government and a learning society.

33 J B Jefferys, ‘Trends in business organization in Great Britain since 1856, with special reference to the financial structure of companies, the mechanism of investment and the relations between shareholder and company’, unpublished PhD thesis, University of London, 1938, pp. 9–10, cited in R A Bryer, ‘The Mercantile Laws Commission of 1854 and the political economy of limited liability’, Economic History Review, New Series, 50: 1, February 1997, pp. 37–56, p. 37.

34 Methods of dealing with debt and personal insolvency date from ancient times. The history is difficult to trace as attitudes have waxed and waned over centuries in the harshness of their treatment of debtors.

35 Referred to in Article 57 of the Charter.

36 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Act 1947, (Act No.24 of 1947), s.2 and Schedule.

37 ibid.

38 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted and proclaimed by the UN General Assembly on 10 December 1948, Article 27 www.un.org/Overview/rights.html.

39 ibid., Article 27(1)

40 United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI) of 16 December 1966; entry into force 3 January 1976, Article 15(1) www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/a_cescr.htm.

41 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 26(1). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), Australian Treaty Series 1976 No.5, Entry into force generally on 3 January 1976, Entry into force for Australia on 10 March 1976. Article 13 expands on aspects of education –at URL www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/other/dfat/treaties/1976/5.html (accessed 16 April 2008).

42 ibid., Article 26(2).