CHAPTER THIRTEEN

PUBLIC SECTOR INFORMATION ACCESS POLICIES IN EUROPE

INTRODUCTION

In the digital age geo-information has become embedded in our daily lives, such as navigation systems, community platforms, real estate information and weather forecasts. Everybody uses geo-information for their day-to-day decision making. Therefore, access to geo-information is of vital importance to the economic and social development of the nation. Most geoinformation, especially the more valuable large scale geo-information is owned by governments all over the world. Government bodies create, collect, develop and disseminate geo-datasets and geo-information to support their public tasks. Although this information is primarily created and collected for internal use, it forms a rich resource for other public sector bodies, citizens and the private sector.

There have been a number of initiatives within the European Union (EU) to provide access to and re-use of this public sector information in order to create a free flow of information and services within the EU. Initially aimed at paper documents, these initiatives had little effect on geo-information. Geo-information existed as paper maps or geo-information systems requiring specialised software. But in the last decade improved computer processing capabilities, broadband internet and interoperability of systems have lead to mass digitalisation and thus better availability of information in general. EU initiatives to improve access to information, especially the 1993 Directive on re-use of public sector information, the so-called PSI Directive (2003/98/EC), should have had a flow-on effect on geo-information. But five years after adoption, its impact has not quite lead to the expected surge of value added geo-information products and services as predicted by some (e.g. PIRA 2000, RAVI 2000). The private sector still faces legal, financial and organisational obstacles when trying to access public sector information (e.g. MICUS 2003 and 2008, Groot et al. 2007).

So, maybe access to public sector geo-information is still not as simple as EU legislation intended it to be. The level playing field as envisioned by EU legislation may not be apparent in the geo-sector. What impact has the EU framework had on access to public sector geo-information to date? This paper will provide a description of the current EU framework. A brief history of public sector geo-information availability will be presented, and a description of the current situation in a number of European countries. The paper will finish with some conclusions and recommendations. 252

GEO-INFORMATION

GEO-INFORMATION USE AND USERS

What is geo-information exactly and why is it so different from other products? To start with, there are many different descriptions of geo-information, depending on the country and the application. Also, the terms ‘geo-information’, ‘geo-data’, ‘spatial information’ and ‘spatial data’ are interchangeably used as synonyms. For the purpose of this paper only the term geo-information (GI) will be used. There are many definitions for the concept of GI. MICUS (2008) defines GI fairly narrowly as ‘topographical data in all scales, cadastral information (including address coordinates and aerial photography’ because these are the categories with the highest re-use rates. In the EU GI is defined as ‘any data with a direct or indirect reference to a specific location or geographic area’ (EU 2007). After a literature study, Longhorn & Blakemore (2008) came up with possibly the broadest definition:

‘Geo-information is a composite of spatial data and attribute data describing the location and attributes of things (objects, features, events, physical or legal boundaries, volumes, etc.), including the shapes and representations of such things in suitable two-dimensional, three-dimensional or four-dimensional (x, y, z, time) reference systems (e.g. a grid reference, coordinate system reference, address, postcode, etc.) in such a way as to permit spatial (place-based) analysis of the relationship between and among thing so described, including their different attributes’.

GI may exist as static information such as aerial images, topographic maps, statistical data, land administration data or census data, but also as dynamic information such as meteorological radar data. In short, GI is more than just digital maps or cadastral information, it also includes administrative information such as address codes, environmental data, government spatial planning and legal system information. Because of its broad scope GI has become a valuable resource in current society.

One of the most efficient ways of making GI available is through an infrastructure. In the EU it will be mandatory for Member States to set up geo-information infrastructures (GIIs) in order to share public sector geo-information (PSGI) between governments. It is envisaged that such infrastructures will also be used by other users. Van Loenen (2006) distinguishes four types of users of a GII, namely primary users (the collector and major users); secondary users (incidental users for similar purposes as the primary user); tertiary users (users that use the dataset for other purposes than the purposes for which the information was collected and the dataset created); and end-users. Van Loenen (2006) asserts that the tertiary users will be the main drivers of the development of a GII. The private geo-sector, including firms that add value to existing GI and resell those products and services, the so-called value added resellers (VARs), form a large proportion of this tertiary users group. But also the end-users are becoming more influential in the development of GIIs. By exploring the viewing possibilities of GIIs they provide essential feedback. This is why consistent access policies are vital for the development of GIIs.

LIMITATIONS

Geo-information – like all other forms of information – has economic aspects which sets it apart from other products. In the case of large scale GI, the fixed production costs of creating information are high and there are also substantial sunk costs. Sunk costs are costs which must be incurred to compete in a market but are not recoverable on exiting the market. The variable costs of reproducing information are low and do not increase if additional copies are produced, 253i.e. the marginal costs are low. There are also no natural capacity limits to the number of copies produced (Shapiro & Varian, 1999). As such, information shows characteristics of a public good, i.e. a good that is non-rivalrous and non-excludable. Consumption of information does not reduce its availability for consumption by others, and in principle no-one can be excluded from consuming the good. However, because of the high investments costs consumption of GI may be limited by legal and/or technological means such as copyright and digital rights management. Thus, by making GI excludable, GI becomes a club good, i.e. a non-rivalrous but excludable good. By claiming intellectual property rights (IPRs) such as copyright – and in the EU also database rights – (re)use of GI can be controlled and commercially exploited through licences. Restricting use with licence conditions and charging a fee allows for recouping some of the investments made. If the public sector makes GI available, fees may vary from marginal cost recovery, e.g. the costs of burning a DVD and postage, to full cost recovery including all investment costs and personnel costs. Especially large scale GI may end up costing millions of Euros for land-covering datasets.

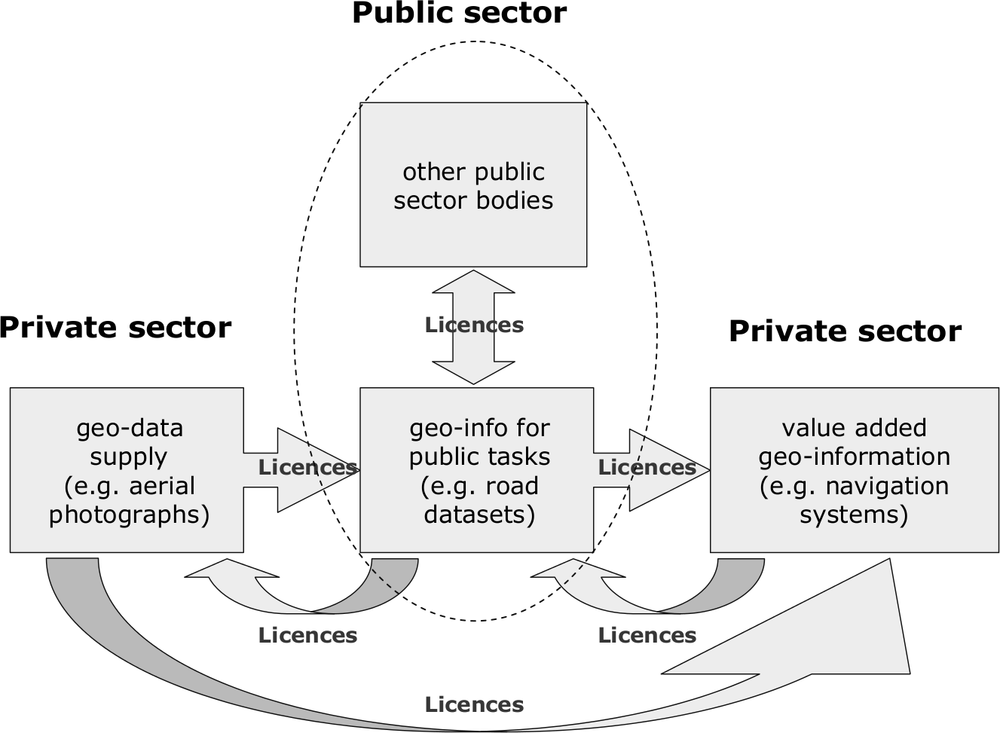

Figure 1: Flow of geo-information between public and private sector (F. Welle Donker, 2009)

GI may consist of many base datasets to make a total package. Integrating and analysing the many varied types of data may be time-consuming, and the process of updating is complex (Longley et al. 2001). Also, these individual base datasets are often from different sources and owned by different parties. These parties may or may not claim IPRs. Therefore, even if only one party supplying only a small part to the total information limits use by IPR, then the entire information will be limited as well. For example, a government agency produces a file 254containing information related to roads. The information includes datasets such as type of road surface, maintenance schedules, topographical layers, address coding, et cetera. The topographical layers are created by another public sector agency and are derived from aerial photographs. The aerial photographs are supplied by a private firm, specialised in such products. The firm claims copyright as a way to commercially exploit their images. The firm may stipulate that for each government agency a separate contract has to be negotiated. The firm may also stipulate that the derived products may not be made available to third parties because the same firm also sells the same aerial images to these third parties.

Another reason why re-use of GI may be limited is that GI may contain data that are subject to privacy protection legislation, e.g. data linked to a natural person. Data may also be limited because of security issues, e.g. satellite images showing army bases or GI may be linked to sensitive information such as breeding sites of endangered animals. As such, GI may have to be adapted before it is made available for (re)use, or may even be withheld or withdrawn from publication altogether.

PUBLIC SECTOR GEO-INFORMATION

GI, and especially large scale GI, is primarily used by the public sector for public tasks such as policy making, spatial planning, flood prediction and relief, emergency services, environmental assessments and many other applications. Large-scale GI generally refers to geographic datasets (to a scale of approximately 1:1,000) in densely populated areas. The scale of a dataset, its technical characteristics, and type are among the factors that determine the cost of data collection, which can vary significantly. A 1:1,000 dataset with comprehensive content for a complete jurisdiction is expensive compared to a 1:1,000,000 dataset that covers only one type of data for a sub-jurisdiction (Van Loenen 2006). Also, large scale GI needs to be updated frequently to be useful. Due to the high investment costs, there are only a few private sector enterprises that are able to produce large scale GI. Therefore, producing large scale GI is most often done by the public sector because of the economies of scale. The public sector may also create large scale GI for historic reasons (e.g. producing topographical maps traditionally for military purposes).

Large scale GI is usually produced for a specific purpose. Sometimes the public sector body acquires base data from the private sector to produce large scale GI, e.g. aerial photographs. These private sector enterprises usually make the data available to the public sector under a licence agreement. After the original purpose has been fulfilled, the public sector geo-information (PSGI) can be (re)used by others, either with or without licence conditions. The largest group of PSGI re-users consists of other public sector organisations. These organisations will adapt the PSGI again to suit their own purposes. Depending on the original licence conditions, they may or may not make this PSGI available for re-use by e.g. the private sector. The private sector can use this PSGI for their own business purposes (e.g. soil data for engineering firms) or they can enrich and add value to the existing PSGI for commercial purposes. This last category of companies is known as the so-called value added resellers (VARs) as they create differentiated products and services, both for the public sector and the market. However, VARs will not be able to produce value added products if the purchase price is too high or the licence conditions too strict. Thus a vicious circle can arise: the public sector starts to develop value added products themselves because the private sector is not doing so to a satisfactory extent (Groot et al. 2007). 255

ACCESS REGIMES FOR PUBLIC SECTOR GEO-INFORMATION

OPEN ACCESS

There are two funding regimes for financing public sector bodies that produce PSGI. The first model is the so-called marginal costs regime. With this regime PSGI is funded out of general revenue, and then made available for re-use for no more than the costs of dissemination and with a minimum of restrictions. Disseminating information for free with no user restrictions is called an open access model. The philosophy behind this model is that once taxpayers have paid for producing PSGI, the information belongs to the taxpayers and they should not have to pay again to re-use this information. This regime is applied to e.g. geo-information of United States (US) federal agencies. The expectations are that with an open access model the knowledge economy will be stimulated, more value-added products will be produced and thus revenue will flow back to the government in the form of taxes such as value added taxes and company taxes (Van Loenen 2006). With the marginal costs regime the costs are shared by all the taxpayers. However, this funding regime is sensitive to political decisions. If funding for a public sector body out of the general budget is reduced, the update frequency and quality of the datasets may be reduced. Also, there is no guarantee that revenue raised from taxation will be returned to the appropriate public sector body (Longhorn & Blakemore 2008).

There is another possible hitch with the open access model, especially when a public sector agency decides to switch to an open access model. Making PSGI available may be deemed to be an economic activity, even if it is for free. As such, it may be in breach with national Fair Trade Legislation in some countries as it may constitute an act of unfair trading practices if the private sector already has made vast investments to create similar datasets. The Dutch Department of Public Works ran into a dispute with some geo-companies after the Department made their National Roads Dataset available for free, in line with existing policy. The geo-companies had produced similar datasets for car navigation producers and for emergency services. The Department of Public Works withdrew the dataset after the geo-companies threatened to sue for unfair trading practices because the free National Roads dataset was competing with the fee-based datasets.

COST RECOVERY

The other regime for funding PSGI is by recovering all costs incurred in production and dissemination of the PSGI from the actual users, i.e. a user-pay system. The fees may include a return on investments. The information is only made available for (re)use under, often restrictive, licence conditions. The pricing model may be a fee per area, subscription fees, fixed access fees, royalties or a combination of these models (Welle Donker 2009). Providing fee-based access to information is called a cost recovery access model. This model is applied to e.g. data from United Kingdom Trading Funds1 such as the Ordnance Survey (the British Mapping Authority). The advantage of this regime is that all costs incurred in producing the information,

256are shared by the actual users. Also, the appropriate public sector body can use the revenue raised for updating and improving the information thus guaranteeing continuous high-quality information. However, when the number of likely (re)users is not known in advance, it may be difficult to set reasonable fees based on cost-recovery (Welle Donker 2009). There is no natural ceiling for prices as the public sector body often enjoys monopolistic advantages. Also, setting fees is complicated because the value of GI depends on many factors and assumptions (Longhorn & Blakemore 2008). Another risk with this regime is the boundary between public and private tasks is becoming blurred as the public sector body is also a market party.

The funding regimes described above are two extremes on a sliding scale. In the EU most governments employ a form of cost recovery regime for GI. In some countries a mixture of open access and cost recovery regimes is employed, sometimes even within the same level of government.

EUROPEAN UNION LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Until the 1990’s, there was no formal framework for marketing PSI. With each country setting their own policies, there was a variety of different policies with a variety of fees and user conditions. From about the mid 1990’s a general rethink occurred in a number of EU countries. Studies carried out in Europe and the US indicated that PSI would be a rich resource for creating value added products and services produced by the private sector (e.g. PIRA 2000). As such, PSI has a potential economic value worth thousands of million Euros. However, due to restrictions in availability, exploitation of PSI in Europe is lagging in comparison to the US. The potential economic value of PSI in general was estimated to be between 28 and 134 thousand million Euros in 1999 (PIRA 2000). Similar national studies came up with comparable figures (e.g. RAVI 2000; MICUS 2001), although other studies came up with more conservative estimates (MEPSIR 2006, OFT 2006). Even with more conservative estimates, the potential value ranges from 10 to 48 billion Euros (MEPSIR 2006).

CREATING A LEVEL PLAYING FIELD

The current legal framework related to PS(G)I is not so straight forward in Europe. Countries that are members of the EU have to abide to EU Directives and Treaties, national legislation and policies. A number of older EU Member States such as Germany and the United Kingdom already have established national legislation such as a Freedom of Information Act, Fair Trade legislation and Copyright Act, as well as specific statutes such as Cadastre Acts or Anti Terrorism legislation. Other EU countries, especially the newer Member States from Eastern Europe, may not have such an advanced legislative framework yet. However, by adopting and implementing the EU directives a general EU-wide framework is slowly emerging.

There are a number of Treaties and Directives which attempt to create a level playing field for businesses and to provide access to information within the EU. The Treaty establishing the European Community (EC Treaty), the Aarhus Convention, the PSI Directive, the INSPIRE Directive and the framework for the protection of intellectual property probably contribute most to setting a general framework. A brief description will follow below. There are additional EU Directives and Guidelines which are in some way relevant to PSI access models. This includes, inter alia, legislation relating to the protection of information and of personal data; broadband Internet access; the need for transparency within financial transactions and supervision by government agencies and the establishment of a regulatory framework for electronic communications networks and services. However, these will not be dealt with in this paper. 257

THE TREATY ESTABLISHING THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY AND THE TREATY OF MAASTRICHT

The Treaty establishing the European Economic Community of 1957 (in 1992 the name was changed to the Treaty establishing the European Community) provided two fundamental freedoms, namely the freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services. After incorporation of the EC Treaty into the Treaty of Maastricht in19932, the number of fundamental freedoms were extended to four, namely (1) free movement of goods; (2) free movement of persons, including free movement of workers and freedom of establishment; (3) free movement of services; and (4) free movement of capital. Both treaties seek to establish a level playing field for a European internal market. These fundamental freedoms are further specified in various directives and guidelines. The Treaties also deal with aspects such as State Aid in order to set a rough framework for governments and agencies when competing with the private sector.

THE PSI DIRECTIVE

The 2003 Directive on the re-use of Public Sector Information (2003/98/EC), the so-called PSI Directive, was established in order to set a general framework for governing the re-use of public sector information and to ensure fair, proportionate and non-discriminatory conditions for re-use. The objectives of the PSI Directive are twofold: 1) to provide access to and use of public sector information as an important ingredient for EU-residents to be well-informed and to participate in the democratic process; and 2) to facilitate the creation of Community-wide information products and services based on public sector information and to enhance the effective cross-border use of public sector information by the private sector in order to create value-added information products and services. The PSI Directive cannot enforce publication or re-use of information. The decision to authorise re-use remains with the Member State or the public sector body concerned. The PSI Directive does stipulate that information should be made available in electronic formats as much as possible. The PSI Directive leaves IPRs unaffected. A public sector body may continue to use licences and/or charge fees for re-use of PSI if they were already doing so in the past. Where charges are made, the total income should not exceed the total costs of collecting, producing, reproducing and disseminating documents, together with a reasonable return on investment. Unfortunately, what exactly is deemed to be a reasonable rate on investment is not specified in the Directive. Any conditions applicable to re-use and charges must be pre-established and published through electronic means where possible. Upon request, a public sector information holder (PSIH) has to give an account of how the charges were calculated and which costs were taken into account. The PSI Directive does not deal with redress issues, leaving that to individual Member States.

THE INSPIRE DIRECTIVE

Directive 2007/2/EC establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE), adopted in 2007, intends to establish a common framework for annotating and sharing geographic data between Member States, thus setting a framework for a

258geo-information infrastructure (GII). The Directive emphasises the environmental reasons to share data between official agencies in different EU countries, rather than focusing on access to that data as a way of promoting wider cross-border usage of geo-information. This INfrastructure for SPatial InfoRmation in Europe (INSPIRE) will be based on (N)GIIs created by Member States that are made interoperable with common implementing rules. The Directive applies to all PSGI used for carrying out public tasks. The INSPIRE Directive leaves IPR claims and the PSI Directive unaffected as far as access regimes and charges are concerned. However, it should be possible to at least view information without incurring fees. As far as INSPIRE is concerned, it will be necessary to facilitate access to PSGI that extend over national or administrative borders, in order to stimulate the development of value-added services by third parties. This should be achieved by developing technical standards to improve cross-border interoperability. Although INSPIRE describes all environmental information to be included in a NGII, it foresees a limited number of policy domains in which specific risks can occur when disclosing certain information, e.g., bird breeding grounds on military sites. The INSPIRE Directive has yet to be transposed into national legislation with the first step due in May 2009.

COPYRIGHT FRAMEWORK

Intellectual property is divided into two categories, namely industrial property (trademarks, patents, trade secrets) and creative works (copyright and related rights, database rights). Copyright was originally conceived as a way to restrict printing by granting exclusive rights to make copies. Nowadays copyright should provide an incentive for the creation of, and investment in, works such as music, films, print media, software, and their economic exploitation. There is no EU Directive establishing copyright as such as Member States already had established national Copyright Acts. The EU Directive on the harmonising of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society (2001/29/EC), the so-called Copyright Harmonisation Directive, merely harmonises terms of copyright protection within the EU. The Copyright Harmonisation Directive specifies the exceptions and limitations to the rights. The Directive also adapts the existing framework to reflect technological developments and allows digital rights management to control access to works. The Copyright Harmonisation Directive implements the framework of the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) Treaties of 1996. However, the Copyright Harmonisation Directive leaves Member States national legislation unaffected.

COPYRIGHT CHANGES

The European Commission announced in July 2008 that some more changes will be made to copyright legislation, mainly to bring performers’ protection more in line with that already given to authors. The European Commission also released a Green Paper on Copyright in the Knowledge Economy. In this Green Paper the Commission has highlighted the need to promote free movement of knowledge and innovation in the EU single market. According to the Green Paper, the free movement of knowledge and innovation should be considered to be the fifth fundamental freedom in the EU. The Green Paper will now focus on how research, science and educational materials are disseminated to the public and whether knowledge is circulating freely in the internal market. The consultation document will also look at the issue of whether the current copyright framework is sufficiently robust to protect knowledge products and whether authors and publishers are sufficiently encouraged to create and disseminate electronic versions of these products (Commission EC 2008) 259

SPIN-OFF DOCTRINE

Public sector bodies regularly claim database right to recoup investments made for producing public sector databases. Some national courts in the EU have interpreted the substantial investment test in such a way that it rules out investment in ‘spun-off’ databases (i.e. databases that are created to support its own operations or that are created as a result of these operations but not created as a core activity), the so-called spin-off doctrine. On November 9, 2004 the European Court of Justice (ECJ) had to rule in four closely related cases brought before it by a number of national courts. The ECJ confirmed the spin-off doctrine and thereby denied protection to producers of single-source databases. Only if the database in question was produced with the sole purpose of commercial exploitation, can database right be invoked, see, e.g. British Horseracing Board v William Hill (ECJ joint cases C-46/02, C-338/02 and C-442/02).

The ECJ ruled in cases against private sector and semi-public sector operators but the spin-off doctrine is also applicable to public sector organisations. In the Netherlands, the spin-off doctrine was confirmed by the District Court of Amsterdam on February 11, 2008 in the case of the Municipality of Amsterdam v Landmark Ltd. Landmark Ltd, a private company, had requested a file pertaining to soil pollution under the Freedom of Information Act. Initially the Municipality of Amsterdam refused to make the file available, claiming it was not public information. After Landmark Ltd lodged a formal complaint about breaching the Freedom of Information Act, the Municipality of Amsterdam decided to make the file available after all but charged a hefty fee by invoking database rights. Landmark Ltd sued the Municipality of Amsterdam claiming that database rights were not applicable. The District Court of Amsterdam ruled that a government or public sector body could not invoke database rights because the investments made to produce the database had not carried a substantial risk as such, even though the Municipality of Amsterdam had made a considerable investment to create the file. The soil database had been produced with public money for a specific public task, and not for commercial purposes (Amsterdam District Court, reg. no. LJN BG1554). The Municipality of Amsterdam lodged an unsuccessful appeal as the Council of State, the highest Dutch Court of Appeal for Administrative Law, upheld the District Court’s decision on April 29, 2009 (Raad van State, case nr. 200801985/1).

DATABASE DIRECTIVE

Europe, unlike the US, has recognised that creating databases requires vast investments. But databases are not subject to copyright protection as databases fail to comply with the creativity requirement. Some EU countries already had incorporated a ‘sweat of the brow’ doctrine in their Copyright Acts, i.e. having invested a substantial amount of resources to produce a work like a database, the creator could claim copyright. The 1996 Directive on the legal protection of databases (96/6/EC) established a sui generis3 right granting a 15 year protection period from date of publication or completion. Any change which could be considered to be a substantial new investment will lead to a new 15 year term. A database is defined as ‘a collection of independent works, data or other materials arranged in a systematic or methodical way and individually accessible by electronic or other means’. A database may contain all sorts of works or materials. The contents are described as ‘information’ in the widest sense of that term (EU 1996). Database rights prevent the unauthorised extraction and re-use of the entire or substantial part of the contents of the database. Since most GI is stored in some form of database and these databases are continually updated, the protection period is almost perpetual.

The objective of the Database Directive was to encourage investment in the information industry by providing protection from copying. However, the protection provided by the Database Directive has had an anticompetitive effect on the information market (Hugenholtz 2005). In effect, all databases are prevented from (re)use because of the ambiguity of terms like

260‘substantial’. Even government bodies claim database rights so licence restrictions and fees for re-using PSI can be imposed. In recent years, the EU national Courts, by adopting the Spin-Off Doctrine, have given some clarity as to when a database may be protected. The Spin-Off Doctrine questions if the requirement of ‘substantial investment’ is fulfilled when the database is generated as a by-product of other activities (spin-off), i.e. a database can only invoke rights if all investments are made solely to produce that specific database. The mere fact that substantial costs were made to collect the data is not enough to invoke protection under the Database Directive (see box Spin-Off).

THE AARHUS CONVENTION

The Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters, was adopted in Aarhus, Denmark, on 25 June 1998. The Aarhus Convention is a United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) environmental agreement and links environmental rights to human rights. It links government accountability and environmental protection. The Aarhus Convention specifies that governments should not only grant passive access to environmental information (giving access to information after an application has been lodged) but also active access (publishing reports, environmental registries, et cetera). The INSPIRE Directive recognises these principles and have adopted similar terms. Although most European countries have ratified the Aarhus Convention, they have adopted different interpretations. Some countries are setting up websites or web services showing environmental information. Some governments are using the Aarhus Convention as a lever to chance existing access policies for environmental information. The Norwegian Government passed legislation making all environmental thematic information available for free. The Dutch government is in the process of setting up a web service which will allow viewing and combining information related to one’s direct environment for free. This web service will include PSGI that is currently fee-based.

OBSTACLES TO ACCESSIBILITY

In spite of the EU framework there are still obstacles to accessibility of PSGI. PSGI is difficult to find as it is scattered throughout different public sector organisations. Often public sector organisations claim IPRs to maintain control over (re)use of PSGI. Each organisation applies its own licence conditions and pricing regime. A survey of PSGI licences in the Netherlands in 2006 revealed that most PSGIHs employ a wide variety of licences, all vastly different in length and phrasing. The licences varied from a couple of paragraphs in plain language to dozens of pages in legalese. The restrictions varied from only having to attribute the source, to having to supply a fully developed business plan showing what the user intends to use the data for. The fees also varied from free to hundreds of thousands of Euros for large scale land covering datasets (Welle Donker & van Loenen 2006). It is this inconsistency and non-transparency in user conditions that forms one of the biggest obstacles for VARs in their decision to (re)use public sector geo-information for their activities (see Groot et al. 2007, STIA 2001, RAVI 2000). Other obstacles frequently mentioned by VARs are unfavourable pricing and restrictive licence conditions (see e.g. MICUS 2008). As a consequence, value-added use remains limited.

Another obstacle to re-use of PSGI is that some public sector organisations will act as a VAR themselves by combining and enriching their datasets, and promoting these in the market. After the privatisation and unbundling wave of the last decade or so, a number of public sector organisations have become (semi-)private enterprises that are required to recover their operating costs. These organisations are also often PSGIHs such as the British Ordnance 261Survey. In some cases the geo-datasets were part of a privatisation ‘dowry’. Thus the original costs of collection and creation are reduced to zero, leaving only ongoing costs for maintenance, development and dissemination. Because of the cost recovery requirements, their GI is traded as a commodity with user restrictions. So, not only does the private sector find it hard to obtain GI from the public sector, they may also have to compete with the same public sector that may enjoy advantages private sector enterprises do not have. This may constitute distortion of the internal European market.

PSGI AVAILABILITY IN EUROPE

Although all EU Member States have to abide by the PSI Directive, there are still quite some differences with respect to access and licence conditions. Information regarding Nord Rhein Westfalen (Germany), Norway, France and the United Kingdom was collected as part of a study (Van Loenen et al. 2007). Information regarding the Netherlands was collected as part of earlier research by the author. In this chapter a brief summary of access policies of these countries will be provided.

North Rhine Westphalia (Germany)

Background

Germany is a federal republic with 16 States that have a high level of autonomy. The German federal government acknowledges the economic, political and societal importance of the availability of GI. The federal program Deutschland on-line has incorporated the GII, the so-called GDI-DE. Implementation of GDI-DE at the federal level is coordinated by the Inter-Ministerial Committee for Geo Information (IMAGI). IMAGI is supported by the GDI-DE Steering Committee and set about developing collaborations with the private sector and academia. IMAGI is now responsible for developing and operating a meta-information system as part of a federal geo-portal. Each German federal authority or agency currently defines its own data policy on a case-by-case basis under the direction of the appropriate Minister. The GDI-DE Steering Committee and IMAGI are – directly or indirectly – working towards the development of a harmonised and simplified licensing framework and a comparable pricing regime for GI (SADL 2008).

Each of the 16 states in Germany is responsible for its own topographic service, land and property register, environmental and statistical information collection, and in general for information policies. Information collection is largely decentralised and carried out mostly on the regional and local level. The different states have issued laws (‘Surveying and Cadastral Acts’) that regulate the work and the mandate of the surveying and mapping authorities, including defining the production of cartographic material as a public task. With regard to GII development, the developments of the GDI-NRW is closely watched by other states and IMAGI, as it may be an example for other state GIIs and GDI-DE.

North Rhine Westphalia (NRW) is one of the 16 states in the west of Germany and borders the Netherlands, Belgium and France. It covers about 34,600 km2 and has a population of over 28 million. Since March 2005 there is an Act stipulating that all PSI must be available for sharing between all levels of government and agencies. The government structure has three distinct levels of public authority: national, regional and local, all of which generate and hold PSGI. The levels are organised as follows: at the national level a State government; at the regional level 5 Regierungsbezirke (larger districts) and 54 Kreis government (small districts); at the local level Gemeinden (municipalities). In NRW small scale topographical information (e.g. 1:10,000) is the responsibility of the State Topographical Service. The Kreisen are responsible for large scale 262geo-information (e.g. 1:1,000). Municipalities are users and the Regierungsbezirke will oversee that the Cadastre Reform Act is adhered to and will assist the Kreisen on a technical level. A Kreis cannot collect its own taxes and is financially dependent on the State (income and property taxes) and Gemeinden (company tax).

Access to PSGI

Access to PSGI is largely controlled by the Cadastre Reform Act and corresponding legislation. GI not covered by the Cadastre Reform Act, the so-called non-geo base data, e.g. aerial photography of the districts, is covered by local policies. All local governments claim copyright and database rights in their information and only grant a ‘limited use’ licence for re-use. Use of geo-base data is free within the public sector. Other users pay a fee based on cost recovery regime. There are different tariffs depending on the format, category of the layers, size of the area required and information density. Different types of users also pay different fees. The pricing structure as set down in the Tariff Regulation is complicated and difficult to understand. Also, prices can be quite steep: a copy of the ALK (Automated Property Map) covering entire NRW amounted to about €3,400,000 in 2006. The private sector has indicated that the Tariff Regulation’s complexity is one of the main obstacles to re-using PSGI. Also, the Tariff Regulation is too inflexible to be of use for web service applications (MICUS 2003).

Because of the barriers re-use of PSGI for developing value added products and services by the private sector remains limited. Some of the Gemeinden, like the City of Aachen, have developed value added services to fill the gap. The Cadastre Reform Act does have a clause which allows experimental use of geo-data. This allows the State government to provide private companies with free access to explore the possibilities of PSGI. If a product appears successful then the free supply of PSGI will be stopped and a contract will be negotiated. An example of one experiment was e.g. www.mySDI.com by Con Terra and Vodafone. However, PSGI is mostly used by other public sector organisations and semi-public sector organisations such as utilities. Another problem for VARs in NRW is access to thematic data. Socio-economic data are not available from one single access point and are therefore harder to obtain. In addition, as production of topographical information is defined as a public task, the State Surveying Authority considers creating spin-off services such as leisure maps also to be a public task (MICUS 2008).

Some Gemeinden and Kreisen provide on-line access to PSGI via Web Mapping Services (WMSs) but they are not obliged to do so. The State government provides online access to its topographic and cadastral information via a web service called TIM-online (www.tim-online. nrw.de). Private use of the web service is free but downloading the reference information is illegal. A user can view information via a WMS. The user can also merge further geodata via a Web Feature Service (WFS)4. Due to the popularity of TIM online and feedback provided by users, the update frequency of TIM online has increased from annually to fortnightly. In addition, the popularity of TIM online has raised awareness of the value of GI at the decision making levels, although this has not resulted (yet) in major policy changes or additional finances. 263

Norway

Background

Norway is a mountainous long stretched country with an extensive coastline of over 2,000 km and an area of 307,000 km². Norway is part of Scandinavia and is located in the north-west of Europe. Norway is a monarchy with a State government, 19 counties (both as regional units of the state government and as a local government) and 431 kommunes (municipalities). Most of its population of 4.6 million reside in the southern part and is otherwise less populated. Norway is not a member of the EU but has strong ties with the EU. Therefore Norway adheres to general EU policy and implements most European Directives, probably even faster than most Member States. However, implementation of the PSI Directive took longer because it was tied to a renewal of the Norwegian FoI Act. The PSI Directive is now implemented in the Act on the right to access to objects in the public sector (public law), which came into effect on 1 January 2009. The new Act sets an upper limit for pricing of public sector information by stipulating that that the right to take a profit can only be used in special cases (www.epsiplus.net/news/psi_re_use_innovation). The Norwegian Ministry of Trade and Industry released a White Paper on 5 December 2008, in which it re-stated its commitment to establish favourable conditions for wealth creation based on sound solutions in the public sector and the increased use of public data as a driver for innovation (Norwegian Ministry of Trade & Industry 2008). In Norway, it is generally accepted that thematic GI is freely available. For environmental information, this has been enshrined in domestic Norwegian law since 1993.

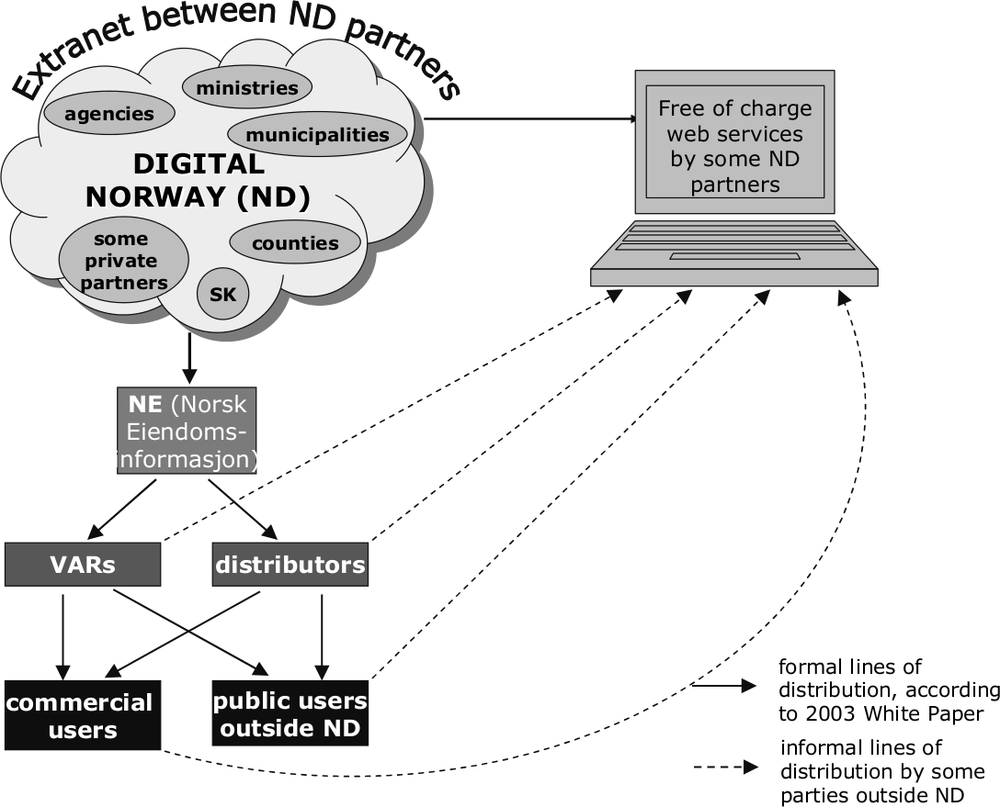

Figure 2: Norway Digital access model, formal and informal lines of distribution, (F. Welle Donker, 2009)

Both the State and local government have such data available on-line. Often this data is only on-line in raster formats but upon request it is possible to obtain the vector version as well. This principle seems to precede the Aarhus Convention (Van Loenen et al. 2007). 264

Access to PSGI

Within the public sector several organisations handle GI. The Norwegian Mapping and Cadastre Authority (Statents Kartverk SK), residing under the Ministry of Environment, is responsible for the coordination of the Norwegian GII. In 2003, a White Paper authorised GI sharing within the public sector by setting up a GII. This program, called Norge Digitalt (Digital Norway, www.GeoNorge.no), provides not only a portal but also a framework for cooperation within the public sector. Nearly all state departments and agencies, as well as local governments, have joined or are in the process of joining Norge Digitalt (ND). After paying a contribution, the government organisation then makes its GI available free of charge to other participating organisations. The contribution paid is related to the importance of base geo-data and the size of the organisation. Within ND all participants can use free GI for its own internal business processes. More than 30 state and almost all local government organisations are a member of ND. For historic reasons, some private sector organisations are allowed to join ND.

If the private sector wants to use PSGI, it can buy datasets from a government-owned intermediary, the Norsk Eiendominformasion (NE). The NE acts as a one-stop shop for VARs to get the data and resell it to end-users. A contract is drafted with the NE and NE pays royalties to ND. NE uses the same (restrictive) licence conditions for all information it resells. However, there are some unresolved issues with this system. As part of the decision to let SK coordinate the ND, the marketing activities of SK were sold off. A private firm, Ugland IT, now has an exclusive right to produce certain map series. SK is not allowed to sell its own GI to the private sector, as this was handed over to NE. However, other members of ND are still allowed to market their own GI. Several public sector organisations provide this GI for free through WMSs. Until 1 January 2007, all SK services were freely available on the web. To be in line with the access policy from the 2003 white paper, SK had to limit free access to ND partners only. NE does not have a publicly known pricing policy. In order for ND to operate more transparently, GI should be made available to outsiders under clear and equal conditions. NE was set up as a one-stop shop for VARs and distributors but is increasingly selling to end-users as well. By doing so NE acts more and more as a market party, thus blurring the separation between public and private sector. Because there is no legal framework for ND as such (only a white paper) there are no clear boundaries.

France

Background

The Republic of France is the largest country in Western Europe. Mainland France (excluding overseas territories of the French Republic) has an area of approximately 543,965 km² and a population of circa 65 million. France is governed by a centralised government, presiding over 22 Regions that are further subdivided into 96 Departments. These Departments are then further divided into Arrondissements and Communes. Most of PSGI is collected and used by these administrative divisions. Designing a common access policy in France is not so simple. The administrative divisions, especially the Communes have a high level of autonomy. Thus, a top-down approach has to be carefully implemented as the Communes cannot be compelled to adopt a Central Government policy, they can only be asked to participate in the interests of the Republic. A number of initiatives have commenced in order to modernise the French government’s approach to access to (national) PSI and services to citizens. One of those initiatives is the Direction Générale pour la Modernisation de l’Etat (DGME) initiative which was launched in January 2006. The Ministry of Public Works, Infrastructure and Land Planning 265is now working on an intranet geo-catalogue / geo-portal system for internal Ministry usage with a view to making this service available to other ministries in the future.

Access to PSGI

Within the DGME initiative, Geoportail has been set up as the main PSGI portal (www.geoportail.fr). There are three organisations responsible for the implementation and maintenance of Geoportail. The overarching organisation is the DGME, since Geoportail is a part of the DGME initiative. The DGME is responsible for coordinating the policies necessary to ensure that public sector bodies (and where possible local governments and the private sector) make their data available to Geoportail. The Ministry of Geology (BRGM) is the second organisation responsible for the implementation of Geoportail. BRGM’s role is to design, implement and maintain the catalogue component (Le Geocatalogue) of Geoportail. With the catalogue function, datasets can be located. The third organisation involved in Geoportail is the Institut Geographique National (IGN). IGN’s function is to implement the other main component of Geoportail, the visualisation component (the Visualiser). With the Visualiser, datasets can be viewed and downloaded. Viewing is free of charge but only custodians of the datasets can download data for free. Other parties like the private sector can download data on a subscription basis. With an API, Geoportail is available for the private sector to upload their own information. Geoportail is envisaged to become a community-oriented and development platform (IGN 2008).

Since its inception in July 2007, Geoportail has attracted millions of viewers with numbers now hovering around 1.2 million users per month (IGN 2008). Most of the datasets accessible through Geoportail belong to BRGM, IGN and some partners and contains topographical, cadastral, hydrographic and thematic information, and historical maps. The Visualiser allows 2D and 3D viewing, rivalling private sector platforms such as Google Earth in speed and performance. Thus, Geoportail far exceeds the requirements of INSPIRE. To increase the performance, images are stored as tiles on the server(s) in advance, requiring Terabytes of storage capacity. Geoportail requires 3 Gbps broadband capacity, two 50 Tb caches and a 100 Tb storage capacity (IGN 2008). Although Geoportail is set up to make PSGI accessible for re-use by both the public and the private sector, it is unclear to what extent revenue through downloads will help to recover the costs of development (circa 6 million Euros) and the annual operating costs (circa 1.5 million Euros). Also, as the lower governments cannot be compelled to participate, the success of Geoportail will depend on their willingness to make their datasets available. Funding will have to be made available to the lower governments to make their data compatible to Geoportail. Already a number of the local authorities have their own web services to provide access to local PSGI. Linking their websites to Geoportail may produce volumes of traffic that these sites were not designed to handle (Van Loenen 2007).

England and Wales (United Kingdom)

Background

The United Kingdom (UK) is an island nation in north-western Europe located between the Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea, to the west of France, Belgium and the Netherlands. The total area of the UK is circa 245,000 km² and its population is nearly 61 million. The UK is a constitutional monarchy and is centrally governed by a national government. Furthermore, there are three Executives (the governments of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales), and a complex system of local government. England, the largest country of the UK, has no devolved executive and is administered directly by the UK government on all issues. There are nine Government office regions, each further divided into boroughs, counties, district councils and 266unitary authorities, about 500 in total. Policy decisions are made by the central government and their agencies. Local governments are mainly responsible for local planning and everyday operations of their areas. The larger local authorities, such as the City of London, have a greater autonomy. The Executives of Scotland and of Northern Ireland have strong levels of independence. The Welsh Executive has more limited powers. For this paper England and Wales are combined as their access policies are very similar.

In the UK, there are different copyright regimes applicable to GI. The main copyright law affecting PSGI is the Crown Copyright. Crown Copyright applies to PSGI produced by central government agencies referred to as Crown Bodies. However, it is not always easy to distinguish which public sector organisations are Crown Bodies and thus affected by Crown Copyright because of technical legal reasons (APPSI 2004). Therefore different central government agencies will have different copyright regimes regulating their information, resulting in different rules for re-use.

Access to PSGI

Because of the centralised structure, the central government and its agencies require access to detailed information at both local and national level. The public sector is therefore the biggest producer of information. To support the service-orientated market, the UK government has implemented a number of initiatives to encourage the use and re-use of PSI. These are:

- the promotion by the Cabinet Office of the re-use of PSI to enhance the knowledge economy and the quality of government in the UK

- the initiatives of HM Treasury to leverage PSI to generate revenue and reduce the cost of government

- the Efforts by the DCA to promote transparent government through the Freedom of Information Act

- the DTI efforts to enhance the competitiveness of the UK information sector and the join-up government policy (APPSI 2004).

However, some of these initiatives show conflicts of interest with each other (APPSI 2004). In 2006, as part of a general review, the Advisory Panel on Public Sector Information (APPSI) had its mandate changed to a non-departmental public body of the Ministry of Justice to – among other things – review and consider complaints related to re-use of PSI.

Most PSGI is generated by the Ordnance Survey (OS), although other parties like the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO), Her Majesty Land Registry (HMLR) and the Royal Mail Group are also active. OS, UKHO and HMLR are all classified as Trading Funds and are required to generate a surplus. Therefore, these agencies all use restrictive licence conditions and fees to make their datasets available for re-use. There is no single access policy for PSI in the UK. UKHO use a network of VARs which re-use hydrographic information on a royalty basis. OS also have licence agreements with various VARs on a royalty basis.

As far as re-use within the public sector is concerned, OS uses a system of Collective Licensing Agreements (CLAs) to make their PSGI available to other public sector organisations. A CLA is a contract between OS and a group of public bodies whereby access is given to OS information for a set fee. There are at least four distinct CLAs between OS and the public sector. These are:

- The Pan-Government Agreement (PGA). This is a contractual arrangement between the OS and Central Government Agencies 267

- Mapping Services Agreement (MSA). This is the contractual arrangement between OS and Local Government Agencies for the provision of GI

- London Government Agreement (LGA). The contractual agreement between the Local Government Authority of London and OS for the provision of GI

- National Health Services Agreement (NHSA). This a blanket agreement amongst the different health sectors of England and the OS for the provision of GI.

The advantage of a CLA is that participants collectively only have to negotiate once with OS to get quick access to high quality information. However, the information may only be used for internal purposes. The public body concerned is not even allowed to place the information on its website. Within a CLA there may be sublicenses for large scale and small scale GI. Central government agencies with different sublicenses are not allowed to share OS information.

In the UK there is no central portal for PSGI but the major suppliers of PSGI offer GI web services with – where applicable – click-through licences. On-line access can be obtained to OS and UKHO datasets via their websites but the access is not open to the general public, only to business partners. There are GI web services that are freely accessible to the general public for viewing such as GI Gateway (www.gigateway.org.uk). GI Gateway is a free web service aimed at increasing awareness of and access to GI in the UK.

INTELLIGENT ADDRESSING V ORDNANCE SURVEY

Intelligent Addressing (IA), as partner of a joint venture with Local Government Information House Ltd, needed a database called AddressPoint to produce the National Land and Property Gazetteer (NLPG). Local governments can obtain data for the NLPG through the Mapping Services Agreement (MSA) with Ordnance Survey (OS) but IA is not a party to the MSA. IA claimed that OS offered licence terms which unnecessarily restricted competition. OS claimed the database was not a document as defined in the Re-use Regulations because the file contained third party (Royal Mail) proprietary postal coding address file. Therefore OS did not have to abide by the Re-use Regulations. In February 2006, IA lodged a complaint to the Office of Public Sector Information (OPSI), the regulatory body for PSI regulations and Fair Trade schemes, about breaches of the Re-use Regulations. In their defence OS claimed that as Royal Mail held third party IPR, the database was not a document as such. Oddly enough, OS’s claim that commercialisation of the information held by OS to be ‘a core part of its task’ was not contested by IA. If commercially marketing of PSI is a public task then the Re-use Regulations should have applied. OPSI ruled in July 2006 that OS had breached the Re-use Regulations. It was then mutually agreed that APPSI would review the findings of OPSI. APPSI ruled in April 2007 that the Regulations did not apply to AddressPoint because Royal Mail held third party IPR. APPSI also ruled that producing value added products was not a public task. Because the Re-use Regulations did not apply, the case was referred to the Office of Fair Trade (OFT).

Implementation of the PSI Directive

The PSI Directive was implemented in the UK in the form of the Re-use of Public Sector Information Regulations 2005 (the Re-use Regulations), dealing with re-use of government documents. Although the term ‘document’ is broadly defined and explicitly includes ‘any part’ of any content (art. 2), the Re-use Regulations do not apply to a document where supply of the document is not part of a public task (art.5(1)a) or if a third party owns relevant IPR in the document (art.5(1)b). The concept of ‘public task’ is not defined in the Regulations. The Re-use Regulations were quickly tested when in 2006 a private firm called Intelligent Addressing complained about the way in which OS licensed its address database called AddressPoint (see box Intelligent Addressing v Ordnance Survey). 268

From about 2007 there has been a marked increase across central government in the level of interest and debate in the re-use of PSI, including a debate about the position of the Trading Funds (APPSI 2007). Reports like the so-called Cambridge Report (2008) concluded that in most cases a marginal cost recovery regime would be welfare improving and would not have a detrimental effect on the quality of the data. Although OS, UKHO and the Met Office would have to receive additional funding from central government, the benefits would be commensurably bigger (Cambridge 2008). In its 2008 pre-Budget Report, the UK government stated that the Treasury will publish some key principles for the re-use of PSI, consider how these currently apply in each of the trading funds and how they might apply in the future, and the role of the OPSI in ensuring that government policy is fully reflected in practice. For OS, this will involve consideration of its underlying business model – (www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/prebud_pbr08_index.htm).

Netherlands

Background

The Netherlands, located in north-western Europe, is a low-lying densely populated country of about 41,500 km² and circa 16.4 million inhabitants. The Netherlands is a constitutional monarchy with a national government, 12 Provincial Councils, 26 Waterschappen (democratically elected water boards) and 441 Gemeenten (municipalities) as per 1 January 2009. The lower governments have a fairly high level of autonomy enshrined in legislation. Politics and governance in the Netherlands are characterised by an effort to achieve broad consensus on major issues. Therefore, the process of policy forming and governance may appear slow but generally, final outcomes are broadly supported by all parties involved. The Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment (Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening & Milieubeheer (VROM)) is responsible for coordinating GI and the establishment of a NGII. Most of the PSGI is collected and used by lower levels of government although VROM, some other Ministries and their related agencies hold large scale base datasets. Some of these PSGI agencies, such as Kadaster (Netherlands Cadastre, Land Registry & National Mapping Agency) and National Co-operation Large Scale Base Map of the Netherland5 (LSV GBKN), are public sector enterprises, i.e. they are self-funded public bodies that generate revenue from sales of their products and services. Other PSGI agencies such as the Department of Public Works are funded out of consolidated revenue. Lower levels of government are self-funded through levies and rates, and receive subsidies from the national government for delegated tasks.

Access to PSGI

Until the 1990 there was no overriding policy for access to PSI or government bodies engaging in market activities. After many complaints from the private sector about unfair trading practices by enterprising public sector organisations, an inquiry was held in 1995. This inquiry resulted in a policy document in 1998, the so-called Guidelines for Economic Activities by National Public Sector Bodies (Guidelines), pending formulation of overarching legislation. The Guidelines state that a national public sector body may only engage in economic activities if the private sector will not or cannot (due to e.g. security reasons). If a public sector agency engages

269in economic activities, then all costs incurred in collecting, processing and disseminating must be passed on to the customer and the agency must pay all due taxes (VAT, etc). The Guidelines only apply to national public sector bodies not covered by specific legislation. Lower levels of government do not have to abide by the Guidelines.

Some national agencies are governed by specific legislation with varying mandates. For instance, Kadaster – as a self-funded public sector enterprise – is allowed to employ a cost recovery regime and may produce value-added products from its own data as enshrined in the Cadastre Act. This means that the PSIHs of the more desirable datasets such those of Kadaster and the municipalities are not covered by the Guidelines. Also, the Guidelines only have the status of pseudo-legislation. In the few (lower) court cases where breach of the Guidelines was contested, the courts have set the Guidelines aside. The overarching legislation, although rewritten a number of times, has not proceeded beyond the draft stage to date.

Access to PSI in the Netherlands is covered since 1991 by the Freedom of Information Act (FoIA). The FoIA provides for access to public information, i.e. all information within government except information relating to national security, the security of the Crown, trade secrets, and information covered by privacy legislation. The general pricing regime is dissemination costs only. PSI covered by specific legislation, such as by the Cadastre Act, is subject to its own pricing regime. The dissemination costs regime also does not apply to data for which the policy line would result in financial problems for the supplier of the information. The FoIA was amended in 2006 when the PSI Directive was implemented as a separate chapter, 5A, in the FoIA. Chapter 5A stipulates that for re-use of PSI subject to IPR the total income out of supply of information should not exceed the costs of collection, production, reproduction and distribution, increased by a reasonable return on investments. With the ever decreasing blur between access to PSI and re-use of PSI in a web based environment, the duality of pricing regimes in the FoIA6 is confusing to both the public and the private sector. For national public sector bodies there is an additional clash between the policy line of no more than dissemination costs and the earlier mentioned Guidelines, which state that all costs made must be passed to customers. Provincial Councils and Waterschappen adopted the dissemination costs regime around 2006. Municipalities, however, use a variety of cost regimes. The larger municipalities, such as Amsterdam and Rotterdam, use full cost recovery regime for making their GI available because they have to finance their surveying departments. Most PSGIHs with a cost recovery regime basis, market their GI for area based pricing or on a subscription basis. The only exception is the Dutch Hydrographic Service which markets its GI to a set number of VARs on a royalty basis.

In the Netherlands there is a portal for all government information, but only for administrative documents such as copies of legislation (www.overheid.nl). There is no NGII as such, although serious efforts have been undertaken in the past to establish one. Currently – as part of INSPIRE requirements – Geonovum, the Dutch NGII Executive Committee is in the process of setting up a geo-catalogue service as precursor to an NGII. At the moment if one wants to find specific PSGI one still has to muddle through search engines. Most PSGIHs have their own web services, usually offering (samples of) PSGI free for viewing. Downloading is usually only possible after a paper contract has been signed. 270

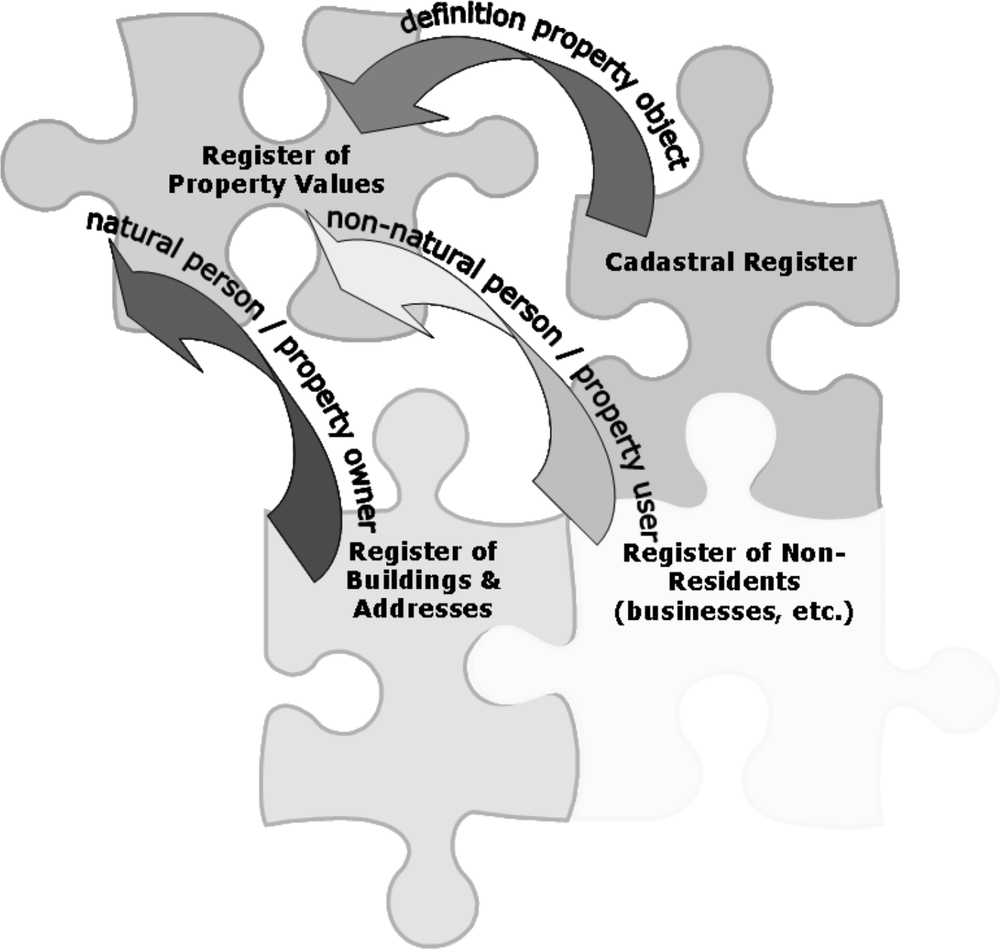

Base Registers

The Dutch national government is in the process of establishing a system of base registers. The idea is that authentic public information is only collected once and re-used many times. For instance, municipalities will be responsible for maintaining a single register for residents and addresses in its district. These 441 municipal registers are then combined into one national register. Other governmental bodies at all levels must re-use data from that register so that citizens do not have to resubmit name and address details every time they deal with a public sector body. Municipalities will be responsible for the quality of the data, and other government bodies must report back any mistakes to the municipality. The Dutch government has designated ten base registers so far, another three are nominated and will most likely follow suit. The base registers will include GI datasets such as the 1:10,000 Topographic Map of the Netherlands (TOP10NL), Cadastral Register, Cadastral Map, DINO (data pertaining to the subsoil) and the Large Scale Base Map. The base registers are interrelated, i.e. information out of one register will form an essential part of another register. For example, property ownership information from the municipal Buildings & Addresses Register will be combined with the definition of property objects from the national Cadastral Register and type of usage, e.g. commercial usage, to form the basis of a Register for Property Values (see figure 4).

As far as financing the roll-out of the base registers is concerned, the national government has made funding available. Future funding for maintenance and quality control of all the base registers is not guaranteed yet. Kadaster, the agency responsible for the TOP10NL, Cadastral Map and Cadastral Register, may continue charging other public sector bodies for their information7 even though re-use is compulsory. The base registries are primarily aimed at sharing authentic information between the different public sector bodies. Once fully established, re-use by the private sector may be considered for the public datasets. The base registries will have to be adapted before making them available to the non-public sector so that only aggregated information will be provided. A survey completed in 2007 indicated that the private sector regards base register information as the most valuable resource for creating value added products (Groot et al. 2007).

CONCLUSION

The EU has tried to promote a level playing field for the private sector by setting conditions for the free flow of information and services. This legal framework includes a number of Treaties and Directives such as the Aarhus Convention, the PSI Directive and the INSPIRE Directive. Different Member States have implemented this legal framework in different ways. Some countries such as Norway and the Netherlands have used the legal framework, including the Aarhus Convention, to make thematic geo-information available for free, at least for viewing purposes. France has taken the requirement of the PSI Directive to make PSI available in electronic format, one step further by setting up a geo-portal rivalling Google Earth. Most Member States use the cost recovery clause of the PSI and INSPIRE Directives to use raised revenue to maintain a continuous level of quality. In most comparisons between the EU and the US, the US marginal cost regime is often lauded as a best-practice example. However, the

271US marginal cost regime only applies to federal PSGI. It is debatable to what extent the quality of PSGI can be guaranteed if funding is dependable on political decisions. In the US some federal PSGI has not been updated for years. The Dutch Kadaster nearly went bankrupt at the end of the last century. Only by changing its organisational structure to that of an independent administrative agency with a cost-recovery regime could Kadaster guarantee the continuation of services and quality.

Figure 3: Interrelationship between Dutch Base Registers (F. Welle Donker, 2009)

The PSI Directive has been in force in the EU since 2003, but transposition into a national framework has taken longer with some Member States only having finished implementation in 2008. The effects of the PSI Directive are slowly starting to emerge, in spite of the fact that awareness of the existence of the PSI Directive among re-users is very low (MICUS 2008). But the PSI Directive and its evaluation in 2008 show that Member States are now reviewing their pricing regimes and policies. Some Member States are making more PSGI available for dissemination costs only or have reduced their fees significantly. For example, the Austrian National Mapping and Cadastral Agency (Bundesamt für Vermessungswesen BEV) has 272decreased its prices for digital orthophotos by 97%. Due to the fact that sales volume has increased by up to 7,000%, the total turnover of the BEV has remained more or less stable. New users from small to medium sizes enterprises are now purchasing data from BEV (MICUS 2008). The Dutch New Map of the Netherlands (a GIS file containing planning information from all levels of government) had its access regime changed from cost recovery to open access and was made available for free in April 2006. Since then the number of regular users has significantly increased (Welle Donker & Van Loenen 2006). Thus, by decreasing prices total revenue will in most cases be offset by increases in the number of new users. Especially when the additional revenue to the government in the form of value added taxes, company, income taxes, is taken into account, the total revenue will actually increase in the long term (Van Loenen 2006).

The PSI and INSPIRE Directives are have been instrumental in improving access to PSGI. In the past users of PSGI have indicated that the biggest obstacles to re-using PSGI was poor accessibility – both in terms of access rights and physical access – inconsistent and non-transparent access policies, differences in pricing, liability regimes and user conditions (e.g. KPMG 2001, RAVI 2000, PIRA 2000). Thanks to the PSI and INSPIRE Directives and technological advances, physical access to PSGI is improving. PSGIHs are setting up portals and WMS/WFSs that allow information from different sources to be combined. If those web services are also used to sell downloadable information, care should be taken to ensure that the pricing mechanism does not become too complex to calculate (MICUS 2003). Setting up geo-catalogues as part of NGIIs is a big step towards being able to find appropriate PSGI.

But there are still some more obstacles for (re)users. The biggest obstacle still appears to be restrictive and non-transparent licence conditions. PSGI has little value to users if the information cannot be re-used to create new products, either because the licence conditions are unclear or because the user is not allowed to re-use the PSGI. This is not just a problem for VARs which will have to obtain the necessary information from other sources. End-users wanting to re-use PSGI for their personal websites or community platforms may encounter the same problems. Already, community-driven initiatives to develop parallel GI are emerging. One such initiative is Open StreetMap which was originally set up in the UK in 2004 because OS did not allow their data to be re-used on community websites. Open StreetMap is a project whereby volunteers go out with GPS units to produce open source street maps for free usage. Open StreetMap now operates in many countries on six continents. Some private geo-companies have donated cartographic information or money to the project as well in return for their data or as a platform for innovative applications (www.opengeodata.org/?p=223). Open StreetMap is a prime example of an alternative GI platform purely developed because local PSGI just is not accessible for end-users.

Complicated and inconsistent licence conditions are a particular problem when combining different datasets. The INSPIRE Data and Services Sharing Drafting Team (2008) has come up with a guideline for licence implementing rules, including types of licences and a model for specific licences. Unfortunately this is only a guideline as the implementing rules are not compulsory. The model is a step forward because it addresses issues such as re-use by third parties. The model also contains an Emergency Use clause and a Transparency clause, similar to the transparency clause in the PSI Directive. The Creative Commons system of licensing can also be applied to free PSGI since the Creative Commons does not allow financial gain to be made. Creative Commons also provides a useful template to adapt the licensing framework to fee-based PSGI (Welle Donker & Van Loenen 2006). 273

Finally, there is a conflict of interest when public sector agencies act as VARs themselves, especially when in direct competition with the private sector. In the UK, Trading Funds act as VARs because they are required to recoup their costs. In Germany, production of topographical information is defined as a public task. Therefore creating spin-off services such as cycling maps are also deemed to be a public task, thus effectively locking the private sector out. In Norway when ND was set up, the SK was forced to sell its marketing activities. But other ND-participants can still sell their own data, making it more confusing for the private sector because of varying pricing and licensing regimes. In the Netherlands, Kadaster is legally mandated to produce value added products and services but only from their own data. Because of its monopoly position Kadaster takes part in many co-operative organisations. Within those co-operations Kadaster produces value added services using non-Kadaster data as well, and then sells those services to third parties. Just as OS does in the UK, Kadaster is pushing the boundaries of its legal mandate.

If there is to be a true free flow of geo-information and geo-services in the EU, there is still a long way to go. The legal framework is paving the way but the devil is in the interpretation into national legislation. Every Member State has its own legacy of PSGI access policies. Concepts like ‘public task’ are interpreted in different ways. What is deemed to be a public task in one Member State is deemed to be a task for the private sector in another. All the EU Member States have different legally mandated PSGI bodies with different cost regimes and different existing policies and legislation. Changing access policies will require extra funding and may also run into unforeseen problems. If a public sector body changes its access policy to unrestricted re-use for free, it may be in breach of national Fair Trade legislation if the supply of PSGI is deemed to be an economic activity. So, even if the Directives are transposed in their most liberal sense, they may still be in breach of existing national legislation. Whilst developing a functioning framework in the EU is a long term goal, legacy systems may slow down the required changes. Although it will take a long time before a level playing field is truly developed, at least the PSI Directive has had the effect that Member States are now seriously looking at and harmonising access policies in the EU. INSPIRE will probably give an additional impetus when it becomes operational.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ALK | Automatisierten Liegenschaftkarte (Computerised Property Map) |

| APPSI | Advisory Panel on Public Sector Information |

| BEV | Bundesamt für Vermessungswesen (Austrian National Mapping & Cadastral Agency) |

| BRGM | The Ministry of Geology |

| CLA | Collective Licence Agreement |

| DGME | Direction Générale pour la Modernisation de l’Etat |

| E(E)C | European (Economic) Commission |

| ECJ | European Court of Justice |

| EU | European Union |

| FoIA | Freedom of Information Act |

| GI(I) | Geo Information (Infrastructure) |

| HMLR | Her Majesty Land Registry 274 |

| IA | Intelligent Addressing |

| IGN | Institut Geographique National (National Cadastral & Mapping Agency) |

| IMAGI | Inter-Ministerial Committee for Geo Information |

| INSPIRE | INfrastructure for SPatial InfoRmation in Europe |

| IPR | Intellectual Property Rights |

| LSV GBKN | Landelijk Samenwerkingsverband Grootschalige Basiskaart Nederland (National Co-operation Large Scale Base Map of the Netherland) |

| ND | Norge Digitalt (Digital Norway) |

| NE | Norsk Eiendominformasion |

| (N)GII | (National) Geo Information Infrastructure |

| NLPG | National Land and Property Gazetteer |

| NRW | Nord Rhein Westfalen (North Rhine Westphalia) |

| OFT | Office of Fair Trading |

| OPSI | Office of Public Sector Information |

| OS | Ordnance Survey |

| PS | Public Sector |

| PS(G)I | Public Sector (Geo) Information |

| PSGIH | Public Sector Geo Information Holder |

| SK | Statents Kartverk (Norwegian Mapping & Cadastre Authority) |

| TOP10NL | Topographic Map 1:10,000 of the Netherlands |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| UKHO | United Kingdom Hydrographic Office |

| UNECE | United Nations Economic Commission for Europe |

| US | United States |

| VAR | Value Added Reseller |

| VROM | Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening en Milieubeheer (Dutch Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment) |

| WFS | Web Feature Service |

| WIPO | World Intellectual Property Organisation |

| WMS | Web Map Service 275 |