CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

BORDERS IN CYBERSPACE: CONFLICTING PUBLIC SECTOR INFORMATION POLICIES AND THEIR ECONOMIC IMPACTS*

1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION

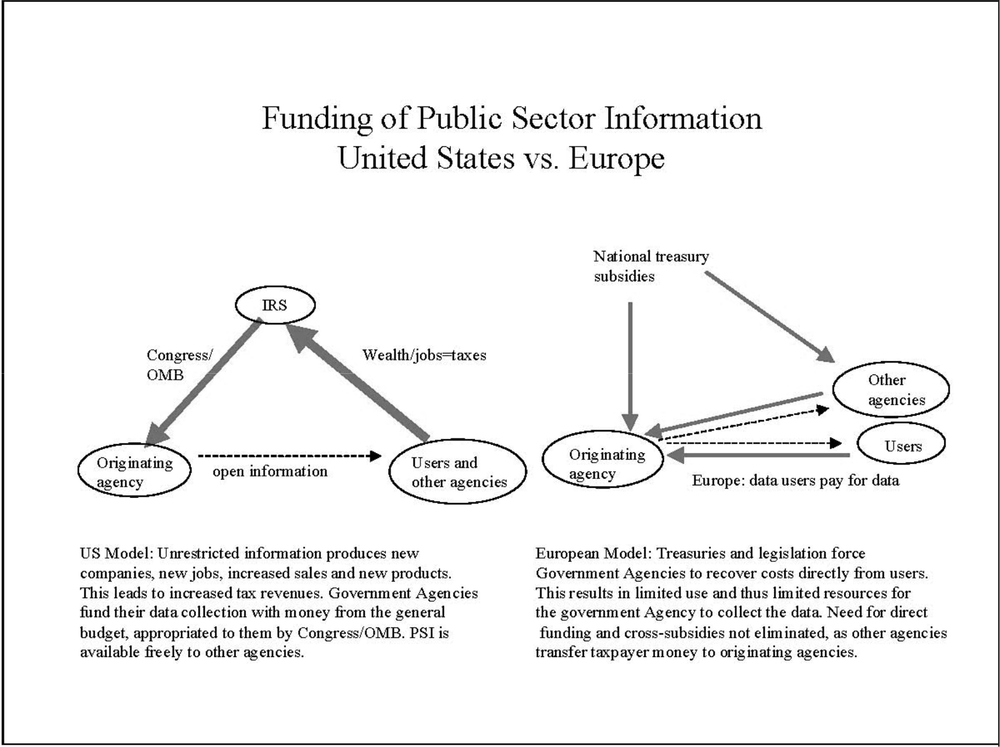

Many nations are embracing the concept of open and unrestricted access to public sector information – particularly scientific, environmental, and statistical information of great public benefit. Federal information policy in the US is based on the premise that government information is a valuable national resource and that the economic benefits to society are maximised when taxpayer funded information is made available inexpensively and as widely as possible. This policy is expressed in the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995 and in Office of Management and Budget Circular No. A-130, ‘Management of Federal Information Resources’.2 This policy actively encourages the development of a robust private sector, offering to provide publishers with the raw content from which new information services may be created, at no more than the cost of dissemination and without copyright or other restrictions.

In other countries, particularly in Europe, publicly funded government agencies treat their information holdings as a commodity used to generate short-term revenue. They assert monopoly control on certain categories of information to recover the costs of its collection or creation. Such arrangements tend to preclude other entities from developing markets for the information or otherwise disseminating the information in the public interest.

In the US, open and unrestricted access to public sector information has resulted in the rapid growth of information intensive industries particularly in the geographic information and environmental services sectors. Similar growth has not occurred in Europe due to restrictive government information practices. As a convenient shorthand, one might label the American and European approaches as ‘open access’ and ‘cost recovery’, respectively. The cost recovery model is now being challenged on a variety of grounds: 593

- Economists argue that the benefits to the American Treasury that accrue from corporate and individual taxes from the secondary publishing and service activities stimulated by open access policies far exceed any revenues that might be generated through cost recovery policies;

- Cost recovery policies often mean that budgetary constraints prevent some government agencies from acquiring information that has already been created or collected by another part of government, resulting in agencies either doing without or using inferior alternatives;

- No one supplier, public or private, can design all information products required to meet the needs of all users in a modern information-based economy. Private sector intermediaries are increasingly important players in the rapidly developing information economy;

- European information service providers are increasingly frustrated at the competitive advantages enjoyed by their American counterparts;

- A recognition that efforts to build transnational data sets, be they meteorological or environmental (where serious problems have already arisen), statistical or cartographic, are hampered by national agencies bent on preserving intellectual property to pursue local cost recovery policies;

- A growing understanding of the wealth creating possibilities (‘prosperity effects’ in the words of one Dutch study) that arise from a common information base (e.g. US street mapping) or software standard (e.g. the World Wide Web).

This report examines fundamental differences in the policy and funding models for public sector information (PSI) in the US as compared to Europe. The following figure illustrates these differences.

594This report seeks to demonstrate the economic and societal benefits of open access and dissemination policies for public sector information, particularly as compared to the limitations of the ‘cost recovery’ or ‘government commercialisation’ approach.

It focuses primarily on the conclusions of recent economic and public policy research in this area, as well as examples of failed or limited cost recovery experiments in the US and Europe. Emerging European thinking on the issue of government competition with the private sector, and recent developments at the European Commission level and in selected European countries are briefly summarised.3

2. RECENT RESEARCH

The vast economic potential of public sector information has only recently begun to be recognised in the economics and public policy literature. Recent significant research, much of it originating in Europe, documents the effect that governmental information policies have on the economy in general and on particular sectors.

THE POTENTIAL OF EUROPEAN PUBLIC SECTOR INFORMATION

With respect to the growing challenge from economists, the European Commission’s Directorate General for the Information Society commissioned a study from PIRA International on the Commercial Exploitation of Europe’s Public Sector Information. (‘the PIRA study’)4. The PIRA study attempts to quantify the economic potential of public sector information in Europe and the extent to which it is being commercially exploited, and suggests policy initiatives and good practices. Although some of the qualitative data had to be extrapolated, the study should be sufficient to persuade policymakers of the need for serious rethinking of European information policy and its high priority. PIRA states:

Cost recovery looks like an obvious way for governments to minimize the costs related to public sector information and contribute to maximizing value for money directly. In fact, it is not clear at all that this is the best approach to maximizing the economic value of public sector information to society as a whole. Moreover, it is not even clear that it is the best approach from the viewpoint of government finances. […] Estimates of the US public sector information market place suggest that it is up to five times the size of the EU market.

The PIRA study went on to observe that the fledgling European market would not even have to double in size for governments to more than recoup in extra tax receipts what they would lose by ceasing to charge for public sector information. The problem is that these positive macro-economic effects are masked by the adaptation of European markets to cost recovery policies, by which both individual agencies and partner publishers have grown adept at extracting monopoly rents from captive markets to their own benefit but to the detriment of the economy at large. Furthermore, as the study noted with understatement: 595

The concept of commercial companies being able to acquire, at very low cost, quantities of public sector information and resell it for a variety of unregulated purposes to make a profit is one that policymakers in the EU find uncomfortable.

The amounts of money involved are significant. PIRA distinguished between government investment in public sector information (‘Investment Value’) and the value added by users in the economy as a whole (‘Economic Value’). Economic Value could not be directly obtained, so aggregated data was used. PIRA estimated the Investment Value of public sector information for the entire European Union at 9.5 billion EURO/year. The Economic Value was estimated at 68 billion EURO a year. By comparison, the Investment Value for the United States is 19 billion EURO/year and the Economic Value is 750 billion EURO/year. To summarise:

| Economic Potential of PSI in Europe and US | ||

| In EUROs | EU | US |

| Investment value | 9.5 billion | 19 billion |

| Economic value | 68 billion | 750 billion |

This contrast points to both opportunities and challenges for European companies and their governments. PIRA’s main conclusions are:

- Charging for public sector information may be counter-productive, even from the short term perspective of raising direct revenue for government agencies;

- Governments should make public sector information available in digital form at no more than the cost of dissemination;

- The fledgling EU market would not even have to double in size for governments to more than recoup in extra tax receipts what they would lose by ceasing to charge for public sector information;

- Governments realise two kinds of financial gain when they drop charges:

- Higher indirect tax revenue from higher sales of the products that incorporate the public sector information; and

- Higher income tax revenue and lower social welfare payments from net gains in employment.

PROSPERITY EFFECTS OF OPEN ACCESS POLICIES

A study commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of the Interior examined both qualitative and quantitative prosperity effects of different pricing models for public sector information5: no cost, marginal cost and full cost recovery. Its main conclusions:

- Prosperity effects will be maximised when data is sold at marginal cost. Marginal cost is defined as all costs related to the dissemination of public sector information. This includes shipping, promotional costs, personnel and information technology costs

- Enormous additional economic activity can be expected by extrapolating the study’s results to all public sector information. 596

RESOLVING CONFLICTS ARISING FROM THE PRIVATISATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL DATA

A U.S. National Academy of Sciences study6 which examined the practices of commercialised government agencies in Europe and experiences with privatisation of environmental data in the US concluded:

‘…[c]ountries that exercise intellectual property rights over government data…limit the extent to which government-collected data can be used, even in international collaborations. By making it more difficult to integrate global data sets and share knowledge, such a commercialization policy will fail to achieve the maximum benefits provided by international collaboration in the scientific endeavor’.

For example, basic research on monsoon prediction at the India Institute of Technology is hampered by the unaffordable prices for historic atmospheric model data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting. As a result, the researchers are not able to integrate the European data with freely available US data.7

Thus, the Academy recommended:

- Environmental information created by government agencies to serve a public purpose should be accessible to all. To facilitate further distribution, it should be made available at no more than the marginal cost of reproduction, and should be usable without restriction for all purposes

- The practice of public funding for data collection and synthesis should continue, thereby focusing contributions of the private sector primarily on value-added distribution and specific observational systems.

ECONOMIC BENEFITS OF OPEN ACCESS POLICIES FOR GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

A study8 commissioned by the private sector members of the Dutch Federal Geographic Data Committee attempts to quantify the economic effects of open access policies for spatial data. The main conclusions are:

- Consumers as well as private business can profit significantly from freely accessible public sector information;

- Growth potential for the geographic information industry: lowering the price of public sector geographic data by 60% would lead to a 40% annual turnover growth plus employment growth of approximately 800 jobs. Companies that pay a much lower price for public sector information will invest these savings in the development of new products, thereby expanding the potential market. 597

POLICY COMPARISON IN THE DISSEMINATION OF SPATIAL DATA

A North American-European comparative study on the impact of government information policies, which focused on databases from national mapping agencies,9 concluded that:

- A direct association exists between pricing and its effects on public access and commercialisation of government agency information. Current pricing problems are having a deleterious effect on the affordability of spatial data in Canada, France, and the United Kingdom;

- A direct association exists between the application of intellectual property rights and the degree of public access and commercialisation of government agency information. The greater the restrictions on access, the less successful dissemination programs will be;

- Reducing prices and relaxing intellectual property restrictions on government datasets are significant factors improving opportunities for access and commercialisation for stakeholders in the geographic information community.

THE IMPACT OF DATABASE PROTECTION LEGISLATION IN EUROPE

A study prepared for the Canadian government examined the European Database Directive, which does not exclude governments from using the database protection right and gives European governments an extra argument for cost recovery policies.10 Therefore, its findings are important in the debate on public sector information policies:

- During its first year, the new protection right seems to have produced a one-time boost in database production and the number of new firms entering the industry. Since 1999, however, growth rates have returned to previous low levels

- The European database protection regime has also produced side effects (‘negative externalities’ in economic parlance) including:

– Excessive protection for certain databases (e.g. phone directories, environmental observations);

– New barriers to data aggregation;

– New opportunities for dominant firms to harass competitors with threats of litigation;

– Increased transactional gridlock due to so-called ‘anti-commons’ effects; and

– Inadvertent impediments and disincentives for non-commercial database providers, e.g. universities and other research institutes.

THE ECONOMICS OF METEOROLOGICAL INFORMATION

John Zillman, Director of the Australian Meteorological Department and John Freebairn of the University of Melbourne recently performed extensive theoretical research on the economics of meteorological information.11

Their main conclusions are:

- Direct government funding and free provision to all are favoured with their contribution to national welfare maximised at the point where marginal benefits equal marginal costs

- ‘Private and Mixed Goods’ (i.e. ‘value added’) meteorological services are most economically produced and provided through market forces.

COMPARING WEATHER RISK MANAGEMENT AND COMMERCIAL METEOROLOGY MARKETS IN THE US AND EUROPE

The Weather Risk Management Association, representing an emerging economic sector which uses weather and climate data to mitigate commercial risk, commissioned PricewaterhouseCoopers to study the rapid growth of this industry.12 The study shows that the weather risk management industry is booming in the United States (9,696 million USD in contract value in 5 years ending March 2002) compared to the small European market (721.3 million USD in the same 5 years)

| Notional Value by Contract Coverage Period and Region, All Contract Types (in thousands of US Dollars) | ||||||

| Coverage Period | North America | Europe | Asia | Australia | Other | Total |

| 1997 | 169,410 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 169,410 |

| 1998 | 1,835,238 | 320 | 0 | 0 | 300 | 1,835,858 |

| 1999 | 2,882,423 | 70,690 | 4,360 | 0 | 1,689 | 2,959,162 |

| 2000 | 2,409,185 | 49,329 | 45,067 | 2,523 | 10,541 | 2,516,645 |

| 2001 | 2,400,000 | 90,000 | 90,000 | 25,000 | 1,190,001 | 4,306,000 |

| Total | 9,696,256 | 721,339 | 139,427 | 27,523 | 1,202,530 | 11,787,075 |

599A comparison of US and European commercial meteorology activity also illustrates a significant disparity. The prosperous commercial meteorology activity in the US has resulted in a tenfold difference in the number of firms, revenue, and job creation.13

Given that the US and EU economies are approximately the same size, the primary reason for the European weather risk management and commercial meteorology markets to lag so far behind the US is the restrictive data policies of a number of European national meteorological services.

3. GOVERNMENT COMPETITION WITH THE PRIVATE SECTOR – WHAT IS THE APPROPRIATE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT?

The larger public policy issue behind public sector information policies is whether or not commercial government activities that compete with the private sector are proper for a government agency funded primarily by the taxpayers. In 1995, European national meteorological services prevailed in the World Meteorological Organization on the issue of replacing the organisation’s previous policy of full and open exchange of meteorological information with a procedure (WMO Resolution 40, CgXII), which sanctions charging and use restrictions on broad categories of data. In the words of the National Academy’s ‘Privatization’ study, summarised above:

The change of policy was aimed at preventing private sector entities from competing with national meteorological services in Europe, which recoup costs through sales of data and services… WMO Resolution 40 substantially decreased the amount of data member nations made freely available.14

Three recent examples illustrate the Academy’s point.

- In Switzerland, a commercial meteorology firm alleged that the Swiss national meteorology office was engaging in price discrimination by offering discounted, nominal prices to its own commercial arm. The Swiss competition authority held:

– Anyone engaging in the sale of meteorological [data] as well as providing sovereign activities, is acting as an independent party in the commercial process and, as a public undertaking, is subject to the provisions of the Antitrust Act … In the Swiss market, [the Swiss Meteorological Institute] has a market-dominating position. It must make available to interested third parties on a non-discriminatory manner all the data and products which it uses for its own services15

- In Germany, the leading news magazine Der Spiegel recently published an expose of the German meteorological service, Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD)16. It claimed that the DWD was also engaging in price discrimination in an attempt to drive its newly emerging commercial weather service ‘competitors’ out of business. DWD was said to be offering completely produced and ready to air weather forecasts to television and radio stations at prices equal or lower than charged the commercial meteorological firms for the raw data on which to base their competing broadcast forecasts. According to atmospheric sciences professor Dr Michael Sachweh of the Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich: 600

– This is for sure no fair competition … The commercial companies are pushed to the wall

- In an apparent attempt to drive commercial weather companies out of business, the Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI) deliberately degraded its radar images between June 1999 and December 1999 when delivering them to the Scandinavian Composite consisting of radar images for Finland, Sweden and Norway, which is sold to private sector commercial weather services. The degraded radar images contained false radar signals (‘clutter’) which users mistook for rain. In its own operations, the FMI used the high-quality radar observations.

The Finnish Competition Authority found that the FMI abused its dominant position in the national meteorological data market and recommended an infringement fine of FIM 200,000 (33,500 Euro) on the FMI for its breach of competition legislation. To remedy this situation, the Finnish government has announced plans to separate and privatise the commercial arm of FMI as a self-sustaining private sector entity without government subsidy, and retain its ‘public purpose’ functions in a taxpayer funded government agency subject to open data policies.17

In addition to Finland, two other European countries are actively reconsidering the wisdom of such policies and practices.

In Sweden, the Agency for Administrative Development’s (Statskontoret) seminal report ‘The State as Commercial Actor’ identified a range of issues associated with government entities entering the commercial field and the effects on the private sector18. For example, they found that the National Land Survey:

- Had an unfair competitive advantage over emerging commercial firms;

- Was the dominant player in the geographic information market;

- Is the ‘preferred’ provider in the market due to its ‘official’ status;

- Has access to taxpayer-funded ‘strategic infrastructure’, including government owned information technology assets;

- Has copyright and other rights over public sector data;

- Is partly funded by taxpayer Kronor and enjoys monopoly rents from other entities;

- Obscures the demarcation between government and private activities.

In light of these findings the Statskontoret recommended that the commercial arm of the National Land Survey be completely privatised, subject to open public audit and oversight, and its data holdings placed in the public domain for access by the general public and competing private sector entities.

As follow-on to ‘The State as Commercial Actor’, the Statskontoret was asked to examine the operations of the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI), and has reached

601similar conclusions.19 It recommended that the commercial functions of SMHI be split off into a private corporation, and the essential government functions of SMHI be retained in a government agency with an open and unrestricted data policy. The study went one step further by recommending that the practice of ‘cross-subsidisation’ of SMHI by ‘assignment’ work from other government agencies should cease. Validated requirements of agencies responsible for roads, fisheries, forestry, etc. would either be put out to bid, or would be designated as inherently governmental and specifically authorised to be performed by SMHI under direct appropriations. The Statskontoret recognised, as argued elsewhere in this paper, that transfer payments from other government agencies have usually been counted by national meteorological services as part of their ‘commercial’ revenues, and touted as part of their success at ‘commercialisation’. An effective date for the separation of SMHI into private and governmental arms has yet to be established.

In the Netherlands, the Ministry of Economic Affairs published a report on unfair government competition with the private sector in the specific context of public sector information.20 The main conclusions were:

- Public sector databases should be made available to third parties on a non-discriminatory basis at uniform prices;

- The public sector should not make unnecessary modifications to databases to create unfair competition. In other words, information services directly linked with the ‘public task’ are allowed, and all other (commercial or ‘value added’) services are forbidden;

- Additional (commercial) information services may only be provided by the public sector when there is a public need for such services, and no private sector company is already providing that service and it is unlikely that any private sector company is going to pursue it in the near future.

Based on this report, the Dutch government separated the commercial arm from the Dutch Royal Meteorological Institute into a commercial entity.

The Swedish and Dutch studies agree generally with consensus views in the US, which are restated by Stiglitz, et al., ‘Role of Government in a Digital Age’21. The Computer and Communications Industry Association commissioned Nobel Laureate and former chair of the US Council of Economic Advisors, Joseph Stiglitz, to analyse the role of government in a digital age, with particular emphasis on public-private competition issues through a number of agency case studies. With regard to the National Weather Service partnership with the private sector and the balance between public and private roles, the report concluded: ‘The National Weather Service seems to strike this balance well’.

An opposite viewpoint remains prevalent among commercialised European government agencies, particularly among national mapping and meteorological agencies. It has been articulated formally in the United Kingdom, where Ministries actively encourage government bodies to develop value-added services charged at market prices: 602

All government bodies will be free to offer value added products and services providing this is done in a transparent manner in a level playing field among all market participants.22

We agree, however, with the central conclusions of both the Swedish and Dutch governments that a level playing field without unfair competition and cross subsidisation is impossible in the case of government agencies providing both commercial and public interest services. Two recent significant experiments in the UK will test this conclusion.

In December 2001, the UK government preliminarily decided to transfer the entire Ordnance Survey from a ‘Trading Fund’ to a government-owned public limited company (PLC) with the government owning 100% of the shares. By contrast, in Sweden (land office and met office, SMHI), the Netherlands (met office, KNMI) and soon Finland (met office, FMI), the approach is privatisation of the ‘commercial arm’ while retaining the ‘public interest’ arm in the government. The belief in Sweden, Holland and Finland is that the basic observing systems and the official forecasts and warnings generated from their data are inherently governmental, as are the public interest mapping and land registration functions of the Swedish land office. This approach inevitably leads to an open data policy since the new ‘spin off’ will need to fend for itself against competition, and the only way to guarantee a ‘level playing field’ is through an open data policy.

In the Ordnance Survey situation, as pointed out by the Swedish Statskontoret in the context of the analogous Swedish agency, if the entity performs both governmental and commercial functions it will tend to have a natural monopoly position due to economies of scale and other factors, and will continue to need infusions of taxpayer funds (even if under contract rather than as a direct appropriation) as ‘commercial’ revenues will not be adequate to fund the ‘public interest’ aspect. If this is accompanied by the right to control the underlying data, funded in part by the taxpayers, healthy competition from other private entities and the overall growth of that economic sector will be impeded.

Using a different model, the UK Met Office has recently entered into a joint venture with private sector interests to create a new entity, Weather Exchange Ltd., which will carry out the functions of the Met Office’s commercial arm, and seek to develop and market a range of value added products. The private interests will contribute capital and staff, and the Met Office will contribute data and staff. Outstanding questions are whether this new entity will have any of the competitive advantages cited by the Swedish Statskontoret in the context of publicly owned commercial entities, and whether the Met Office will adopt a completely open data policy. How these questions are answered will determine whether the commercial meteorology and weather risk management industries in the UK begin to expand, and at what rate.

4. FAILED EXAMPLES OF COST RECOVERY IN THE UNITED STATES

There have been a number of examples of failed cost recovery experiments in the United States at both the Federal and State levels, which demonstrate concretely the practical effects of restrictive data policies. 603

- The ‘Automated Tariff Filing and Information System’ (ATFI) was created by the US Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) to collect, manage and disseminate data on tariffs filed by common carriers, including information on cargo types, shipping destinations and service contract terms. In November 1992, Congress passed the ‘High Seas Driftnet Fisheries Enforcement Act’, Public Law 102–582, which included a requirement that FMC collect user fees from anyone directly or indirectly accessing ATFI data. The goal was to raise $810 million over three years by charging 46 cents per minute to retrieve the information directly or indirectly. However, the actual user fees collected were $438,800, which was only 0.05% of the original mandate.23 This dramatic failure can be attributed to (1) optimistic assumptions about the perceived inelasticity of tariff data, and (2) failure to consider the possibility that users may obtain tariff data from other sources

- The United States Geological Survey (USGS) in the early 1980s attempted to move towards cost recovery by increasing prices for data products including maps. As a result, demand dropped so precipitously that the USGS was forced to quickly reduce prices to recapture the previous market. After reducing the charges to previous levels, sales took three years to return to their earlier level. After this failed attempt towards aggressive cost recovery, the USGS struggled for several years to find a balanced method to recover dissemination costs, suggesting that recovering dissemination costs only is not always easy. USGS has recovered close to 100% of its dissemination costs for the past 4 years, which they now realise is the practical upper bound of cost recovery24

- A spectacular example of the failure of cost recovery for data comes from the State of California.25 California encouraged State level agencies to charge fees to local levels of government within the state for products derived directly from base data provided by these same local levels of government. This cost recovery policy resulted in several problems. First, some local governments could no longer afford to pay for the same products they once obtained at no cost, leading to a disincentive for these local governments to continue providing updated data to the State. Second, some local governments retaliated against the State-level agencies by charging their own user fees. While the State of California has since returned to the ‘free’ system, some local governments continue to charge user fees. Now, due to local government assertion of intellectual property rights, the State cannot include information in public documents obtained from local governments that charge user fees for that information. This has led to incomplete datasets, and State regional plans have a ‘swiss cheese’ appearance, with some areas containing significantly more detail than others. These incomplete and internally inconsistent maps can be particularly troubling during public emergencies when complete, accurate, and easily accessible data is essential. Recognising the failures of cost recovery policies, California has begun to move towards a state-wide open data policy 604

- A tale of two counties. An unintended controlled experiment in cost recovery was performed by two counties in Wisconsin.26 Clark County adopted a cost of dissemination policy for its digitised aerial photographs (digital orthophotos); and Brown County adopted a full cost recovery policy for its identical products. The inexpensive data in Clark Co. led to widespread use by individuals who might not otherwise have even tried using the data. People invested in CAD/GIS software and availed themselves of the County data for a broad range of applications. People got ‘hooked’ on using the data and kept coming back for more. The contrast with Brown County was striking. The cost recovery pricing did not discourage a small number of specialised users such as professional surveyors or others who have site-specific projects where only one section or two of data was needed. However, those needing much larger areas, e.g. entire townships or cities, were deterred by the high pricing. As the county program manager stated:

– Some of the responses from people requesting data is, ‘I can’t afford that! That blows the entire budget for this project’. So they choose not to buy ANY of the data, hang up the phone, and generally go away with a bad taste about the entire program. I don’t think we’re generating much support this way. When people choose not to use our data because it is too expensive, what are the implications? Most people who want to use the data are doing something to the land which affects the community that we all live in. Without good, accurate data, are these people able to make the best decisions? I’ve seen it from both sides of the fence, and I plan to work on revising our policy.

5. LIMITATIONS ON COST RECOVERY IN EUROPE

We believe the perceived benefits of cost recovery have generally been overstated by commercialised European government agencies. The following five examples support this point:

- The Ordnance Survey (OS) of the United Kingdom was chartered as a semi-independent Executive Agency in 1990, and is required to maximise its reliance on revenue from customer entities. However, OS does not approach full cost recovery. Of the £100 million annual OS revenues, only £32 million comes from commercial product sales. The remainder comes from other central, regional and local government departments and agencies as well as from entrenched usage of large scale maps by the recently privatised utilities. These remaining revenues cannot reasonably be characterised as ‘commercial’, but rather are a combination of monopoly rent and reallocation of public money from one public sector ledger to another, with no net benefit to the taxpayer or the Treasury

- Similarly, the UK Meteorological Office gets 50% of its ‘commercial’ revenue as a transfer payment of taxpayer funds from the Ministry of Defence, and reportedly another 20% of its revenue from other UK government agencies.27 The Met Office recently decided to make significant categories of basic observational (surface) data available for free due to negligible revenue from data sales and a growing recognition of the benefits of open access policies 605

- The Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) was reorganised in a 1998 statute that explicitly authorised its commercial activities with a mandate that it minimise reliance on general state funding. However, an audit report issued October 25, 2000 by the German Federal Accounting Office (Bundesrechnungshof), shows that this cost recovery policy has not met expectations.28 Also, in spite of years of expensive consulting assistance, DWD has been unable to set up transparent accounting standards. Data sales recover less than 1% of total expenditures. In sum, DWD has yet to minimise the expenditures that are not covered by income and decrease the burden on the general budget. The report finds that without significant new revenue sources, for example new charges on regulated aviation users of meteorological data, DWD will not achieve its statutory cost recovery mandate

- The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting is losing private meteorology firm customers for its operational model outputs due to unaffordable prices required to be charged by its national meteorological service sponsors. The emerging European commercial meteorology industry is rapidly taking advantage of increasingly inexpensive computational capacity to run their own localised versions of freely available US atmospheric models, and are using freely available US data to initialise those models

- Meteo-France is among the most secretive (French taxpayers cannot obtain access to the details of its expenditures and revenue sources under existing freedom of information law)29 and aggressive (only one French commercial meteorology firm has been identified) of the European meteorological services. A recent WMO report disclosed, however, that Meteo France has come to an understanding with the French treasury that it would endeavour to achieve a cost recovery rate of 10% of its total expenses.30 Beyond data sales, this presumably includes revenue from specialised products for broadcasting and individual clients. In addition, it has established a separate office ‘Meteo-France International’ to encourage developing nations to emulate its government commercialisation and restrictive data policies.

6. OTHER RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN SELECTED COUNTRIES

THE NETHERLANDS

- Three documents under consideration in the Lower Chamber will impact the policy framework for making government information available in the new millennium. The plan ‘Towards the optimum availability of government information’, has developed an ambitious agenda, and declares that government information must be easily and widely accessible and available. It contains a clear analysis of the judicial framework concerning the use of government information. As far as effectiveness is concerned, the plan has a certain degree of ‘try not to step on anyone’s toes’ especially in the category of ‘remaining information’ 606

- The Netherlands completed a comprehensive policy review under its Electronic Government Action Programme, ‘Towards Optimum Availability of Public Sector Information’. This brings the information policies of the Netherlands into close harmony with those of the United States. However, implementation may be less than smooth. The policy objective pursued by the Action Programme is to ensure that public sector information is as widely accessible and available to citizens as possible. First, citizens need that information in order to participate in the democratic process. Secondly, the economy will benefit from public sector information being made available in an open and unrestricted manner. The Action Programme expressed concern that public sector bodies had been reserving copyright and database protection rights on a large scale, and that this was contrary to the spirit of Dutch FOI law. It proposed that no license fee should be charged for the use of public databases, and that copyright and database-right required conditions should only be set for external use to protect the public interest and third party rights

- The ‘Government and Markets’ Directive,31 specified that public sector databases could be made available to third parties only on a non-discriminatory basis and at uniform prices. It also indicated that the public sector should not make unnecessary modifications to databases to create unfair competition. This report led to the separation of the commercial arm of the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) in 1999 as a limited liability corporation (no public sector employees) into a company called Holland Weather Service. Since then, the Dutch government has implemented the following policies:

– Stepwise designation of all meteorological data as ‘essential’ under WMO Resolution 40;

– Adoption of an ‘open and unrestricted’ data dissemination policy with charges limited to distribution costs only.

UNITED KINGDOM

- The UK government has accepted the general principle of providing government data at marginal costs

- However, Trading Funds, e.g. the Ordnance Survey and the Met Office, are specifically excluded from this principle. In general, trading funds have the most interesting public sector datasets when it comes to opportunities for the private sector and the scientific and research communities.32 The Trading Funds are, however, to ‘improve’ (i.e., make transparent) pricing and dissemination policies

- A trend within the UK towards making basic data available is illustrated by a freedom of information law that was enacted in November 2000 and will be implemented starting fall 2002. However, a counter trend towards increasing commercialisation of government agencies still exists, particularly in the cases of the Ordnance Survey and the Met Office, discussed above

- Financial targets for Trading Funds are set by the Treasury, and reflect the cost of assembling data, not its value. The problem this creates is illustrated by the decision to make 2001 Census Data free of charge when it became clear that public sector bodies wouldn’t budget to buy the data, which costs £250 million to assemble. In addition, the UK Meteorological Office is now openly disseminating categories of meteorological observations which are of potentially great public benefit, but which did not generate significant revenue for the agency. 607

FINLAND

- The 1999 Publicity Act provides for a general right of access to legally defined administrative documents created, sent, or received by a government agency, including electronic records, on condition that the document is in the public domain. A public authority can collate various databases and make them available. Data from various public sources can be combined and re-used. The authorities also are to promote public access to information and they are expected to pro-actively publicise their activities and to ensure all relevant documents are readily available.

GERMANY

- No Federal freedom of information law exists in Germany, but one is being considered. As regards access to public sector information, an official statement on the intent of the law under consideration is that, ‘People should be able to access original documents at any time on-line and perform transactions which are important for their daily lives with the administration via the Internet. The public authorities need to make increasing use of the technical possibilities now available to make their administration work transparent for everyone’. However, data policies and commercial re-use of government information do not seem to be under consideration

- In July 2001, a potentially significant competition case in the information field arose in Germany.33 The European competition Commissioner ordered the German company IMS Health to license its geographical ‘brick’ system to competitors due to abuse of its dominant market position. The ‘bricks’ are geographic grids that break down countries and cities into meaningful geographical units for analysing public health related geographical patterns e.g. doctors’ prescriptions, drug sales and public health trends. In the view of the Commissioner, the ‘bricks’ constitute a de facto industry standard in Germany, also known as an ‘essential facility’ in antitrust law, and for there to be fair competition IMS health must license its copyright on reasonable terms. The decision, which is being challenged in German courts, indirectly implicates the question of what types of public sector information may form an ‘essential information infrastructure’. In short, is compulsory licensing of essential government databases on equitable terms necessary to foster a competitive private sector information industry?

7. CONCLUSIONS 608

- The consensus of recent research is that charging marginal cost of dissemination for public sector information will lead to optimal economic growth in society and will far outweigh the immediate perceived benefits of aggressive cost recovery. Open government information policies foster significant, but not easily quantifiable, economic benefits to society

- Over the long term, the cost recovery goal of European governments’ commercialisation approach cannot succeed, because:

– The private user base that can be charged is not large enough to support recovery of the full costs of a comprehensive, unsubsidised information service;

– Charging other government users merely shifts the expenses from one agency to another rather than actually saving the national treasury any money;

– Due to some of the fundamental economic characteristics of information (high elasticity of demand, public good characteristics) one must question whether any governmental entity can successfully raise revenue adequate to pay not only for the dissemination of its information but also for the costs associated with creating the information for governmental purposes in the first instance

– High prices for information ultimately lead to predatory and anticompetitive practices, like price dumping, and the creation of government owned corporations or joint ventures with preferred private sector entities that may serve to exclude others from the market.

- The most sensible solution is to separate commercial activities into truly commercial entities separate from the government and adopt open access policies. Separation of commercial activities would be the basis not only for an open market in accordance with European competition law, but also guarantee market structures with maximum overall economic potential

- Some government agencies are willing to liberalise their policies, but fear that they will suffer budget consequences. Therefore, the relevant government Ministries must come to understand that open data policies will create wealth and tax revenues more than adequate to offset the short term ‘losses’, and that they need to fully fund agency information activities.

In sum, recognition is slowly emerging in Europe that open access to government information is critical to the information society, the scientific endeavour, and economic growth. However, recent trends towards more ‘liberal’ policies face opposition. This comes from treasuries as well as from entrepreneurial civil servants in charge of ‘government commercialisation’ initiatives, who are sometimes tempted to engage in anti-competitive practices. Therefore, these issues require consideration at the highest policy making levels of government.

Recognising the scale of the opportunity presented, and the speed of enabling technological change, the US and the EU should commit to move forward together to take the practical steps necessary to establish internationally harmonised open and unrestricted data policies for all public sector information.

* This was first published as a report titled Borders in Cyberspace: Conflicting Public Sector Information Policies and their Economic Impacts by Peter Weiss. The original report is available at: www.epsiplatform.eu/psi_library/reports/borders_in_cyberspace

1 U. S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Weather Service. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. National Weather Service. Contract support from Yvette Pluijmers, Pricewaterhouse Coopers, is gratefully acknowledged.

2 Respectively, 44 United States Code Chapter 35, and 61 Federal Register 6428 (February 20, 1996).

3 This summary report is accompanied by a longer monograph that includes as Appendices a primer on the economics of information, a point-by-point refutation of arguments commonly made in support of cost recovery, and suggestions for further research. They are not summarised here.

4 PIRA International (2000) Commercial Exploitation of Europe’s Public Sector Information. Final Report for the European Commission, Directorate General for the Information Society.

5 Berenschot and Nederlands Economisch Instituut (2001) Welvaartseffecten van verschillende financieringsmethoden van elektronische gegevensbestanden. Report for the Minister for Urban Policy and Integration of Ethnic Minorities.

6 Resolving conflicts arising from the privatization of environmental data, Committee on Geophysical and Environmental Data. Board on Earth Sciences and Resources. Division on Earth and Life Studies. National Research Council. Washington, DC. National Academy Press, 2001.

7 Goswami, et al. Association between quasi-biweekly oscillations and summer monsoon variabilities, Indian Meteorological Society (March 2001).

8 Ravi Bedrijvenplatform (2000) Economische effecten van laagdrempelige beschikbaarstelling van overheidsinformatie. Publication 00–02.

9 Lopez, Xavier R. (1998) The dissemination of spatial data: a North American-European comparative study on the impact of government information policy. Ablex Publishing Corporation. See also: Lopez, Xavier R. (1996) The impact of government information policy on the dissemination of spatial data. PhD Thesis. University of Maine, Department of Spatial Information Engineering.

10 Maurer, Stephen M. (2001) Across Two Worlds: Database Protection in the US and Europe. A paper prepared for Industry Canada’s Conference on Intellectual Property and Innovation in the Knowledge Based Economy. May 23–24, 2001. See also: Stephen M. Maurer, P. Bernt Hugenholtz, and Harlan J. Onsrud. Intellectual Property: Europe’s Database Experiment. Science 2001 October 26; 294: 789–90. (In: Policy Forum). 598

11 Zillman, J.W. and J.W. Freebairn (2000). Economic Framework for the Provision of Meteorological Services. Also see the background papers: Freebairn, John W. and John W. Zillman (2000). ‘Economic Benefits of Meteorological Services’. Meteorological Applications (2002). And Freebairn, John W. and John W. Zillman (2000). ‘Funding meteorological services’. Meteorological Applications (2002).

12 PricewaterhouseCoopers (2002) The weather risk management industry: survey findings for November 1997 to March 31, 2002. Prepared for the Weather Risk Management Association, June 2002. Website: wrma.cyberspace.com/library/public/file345.doc.

13 Sources: Commercial Weather Services Association, Association of Environmental Data Users of Europe.

14 National Research Council (2001). Resolving conflicts arising from the privatization of environmental data. National Academy Press.

15 Swiss Competition Commission (November 16, 1998). The case is being appealed on other grounds.

16 Der Spiegel, Issue 47 at p. 230, (November 19, 2001).

17 Interview with Finnish Competition Authority, September 2001.

18 ‘The State as Commercial Actor’ (2000). Available only in Swedish.

19 ‘Prognos för SMHI - myndighet, bolag eller både och?’ (‘Forecast for the SMHI - authority, company or both?’) 11 January 2002. Available only in Swedish.

20 Ministry of Economic Affairs (1997). Markt en Overheid; spelregels voor gelijke concurrentieverhoudingen tussen overheidsorganisaties en private ondernemingen.

21 Stiglitz, et al. (2000). Role of Government in a Digital Age. Computer and Communications Industry Association. October 2000.

22 Department of Trade and Industry (2000) Click-Use-Pay – Hewitt. News Release September 6, 2000, P/2000/602.

23 United States General Accounting Office, Accounting and Management Division, March 10 1995 GAO/AIMD-95-93R ATFI User Fees. Also see: Washington Post Editorial, August 4 1992, ‘Boats, Budgets and a Bad Idea’.

24 Blakemore, Michael and Gurmukh Singh (1992) Cost Recovery Charging for Government Information. A false economy? pp. 30–34; updated by USGS staff.

25 National States Geographic Information Council (2001) Fees for Data discussion. Informal email discussion.

26 Email from Jeff DuMez, Coordinator, Brown County Land Information Office (Dec. 2001).

27 See ‘It’s raining weathermen’, The Financial Times (April 23.2001).

28 Bundesrechnungshof (2000) Gebühreneinnahmen aus Flugwetterdienstleistungen des Deutschen Wetterdienstes and Entwicklung der Ausgaben und Einnahmen des Deutschen Wetterdienstes.

29 Statement of Charles DuPuy before the Swedish Meteorology Society, October 2000.

30 WMO Regional Office for the Americas, Regional Seminar on Marketing for NMHSs (September 2001).

31 Directive on market activities conducted by government departments, Dutch Official Journal 1998, no. 95.

32 See e.g. Lopez, Xavier points out the importance of National Mapping data for commercial purposes.

33 The Economist August 25th 2001. ‘Battling over bricks. A growing row over intellectual property rights’. p. 54.