CHAPTER NINETEEN

GOVERNMENT INFORMATION AND OPEN CONTENT LICENSING: AN ACCESS AND USE STRATEGY*

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1.1 This report outlines work undertaken during Stage 2 of the Government Information Licensing Framework Project.

1.2 Stage 1 of the project resulted in endorsement by the Queensland Spatial Information Council (QSIC) and the Information Queensland Steering Committee of an open content licensing model, based on Creative Commons (CC).

1.3 Stage 2 of the project was initiated to bring QSIC licensing arrangements up to date, and to create a Draft Government Information Licensing Framework based on an open content licensing model to support data and information transactions between the Queensland Government, other government jurisdictions and the private sector.

1.4 Other jurisdictions in Australia and overseas are moving to more open access and use arrangements to support social and economic development, and are introducing policies and principles and implementing appropriate licences to support this move. Background research during Stage 2 has resulted in the recommendation that the Queensland Government also move to open access and use arrangements, balanced with appropriate protection for private and confidential information collected or held by government.

1.5 The project proved valuable in testing the CC licences against a sample of existing licences used within the Queensland Government. A detailed legal analysis of existing licences was undertaken to identify key characteristics and to map these to CC licence provisions.

1.6 Feedback received through consultation workshops conducted with agencies identified a clear demand for simpler, formal and standardised licences.

1.7 The project included a review of the digital rights management component which embeds an electronic watermark into licensed data.

3531.8 Further work to progress the Draft Government Information Licensing Framework will be required, including developing a business case, legal drafting, developing technical systems for the digital rights management and conducting a pilot project. These activities are proposed to be conducted, subject to funding, during Stage 3. A Government Information Licensing Framework Project Stage 3: Draft Project Plan was provided to the Strategic Information and ICT Board on 27 September 2006 for noting.

1.9 There is an opportunity to progress a generic standard for government information licensing in partnership with CC.

1.10 This report is to be provided to QSIC, the Information Queensland Steering Committee, the Office of Economic and Statistical Research Office Management Team and the Strategic Information and ICT Board.

2. RECOMMENDATIONS

2.1 That the Queensland Government establish a policy position that, while ensuring that confidential, security classified and private information collected and held by government continues to be appropriately protected, enables greater use and re-use of other publicly available government data and facilitates data-sharing arrangements.

2.2 That the CC open content licensing model be adopted by the Queensland Government to enable greater use of publicly available government data and to support data-sharing arrangements.

2.3 That QSIC and the Office of Economic and Statistical Research continue to work closely with the Department of Justice and Attorney-General to ensure that any privacy provisions developed also support new data use, re-use and sharing policies.

3542.4 That the Government Information Licensing Framework Project Stage 3: Draft Project Plan for the next phase of this project be endorsed.

2.5 That the Draft Government Information Licensing Framework toolkit, which incorporates the six iCommons (Creative Commons Australia) licences, be endorsed for use in pilot projects proposed for Stage 3, which involves Information Queensland, the Department of Natural Resources and Water, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, the Office of Economic and Statistical Research of Queensland Treasury and the Queensland Spatial Information Council, enabling testing of the CC licences for multi-agency and whole-of-Government arrangements.

2.6 That an application be made through the ICT Innovation Fund and Microsoft Program Committee in the Department of Public Works for further funding, to enable the technical development of a Government Information Licensing Management System, consistent with the Draft Government Information Licensing Framework toolkit.

2.7 That a limited number of standard templates be developed to support information-licensing transactions relating to confidential or private information or information with commercial value and for which the CC model is not appropriate.

3. PROJECT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

3.1 Information Queensland and QSIC sponsored this project to update licensing arrangements used within the Queensland Government and the wider spatial industry.1

3.2 Stage 2 has followed on from Stage 1 of the project, which identified that the CC open content licensing model could be used to meet approximately 85% of Queensland Government licensing arrangements. Stage 1 resulted in the endorsement by QSIC and the Information Queensland Steering Committee of an open content licensing model, based on CC.

3.3 The Government Information Licensing Framework Project Stage 2 was established to create a framework for the Queensland Government to support data and information access and use between Queensland Government agencies, between the Queensland Government and other government jurisdictions, between the Queensland Government and the private sector, and to the community. The framework will confirm the Queensland Government as a single business entity and establish standardised terms, conditions and rules for information transactions to support strategic information access and use in the delivery of government priorities.

3.4 Information Queensland is reliant on specific deliverables from the project and has funded the legal component. Information Queensland aims to provide mapping layers, statistical information, and derivative data products to the public via an information web portal and using web service technology, and requires an online licensing solution to enable authorised users easy and timely access to data. The licensing solution is to be based on a whole-of-Government policy position and legal framework and include implementation guidelines.

3.5 QSIC is the peak body for spatial information in the Queensland Government and has been operating effectively since 1992 to develop and maintain Queensland’s spatial information infrastructure to support the state’s economic and social development. QSIC liaises with industry and all levels of government and coordinates several working groups focusing on

355education, global navigation satellite systems, spatial imagery, health communities, addressing and spatial presentation.

3.6 Other initiatives, including the state-wide Water Information Management Project and State of Environment Reporting, rely on access to and use of data held by custodians in other agencies and jurisdictions.

3.7 The National Data Network, coordinated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics partnered by the Queensland Government Statistician and the Office of Economic and Statistical Research, requires an online data and information licensing solution and the Office of Economic and Statistical Research through this QSIC project has offered to provide the results of this project to the National Data Network to benefit its community of researchers and authorised users of administrative statistics.2

3.8 To assist business transactions within the spatial industry, QSIC’s Business Environment is based on a ‘supply chain methodology’, which describes the environment, principles and agreements for the spatial industry. The ‘supply chain methodology’ tracks the use of data from capture, to data management and access, value-adding of data or data integration, to distribution and business integration.

3.9 Four types of licences were developed by QSIC to support the QSIC Business Environment and these are available from the QSIC website – Business, End User, Online User Clickthrough, and a memorandum of understanding.

3.10 While the licences from the QSIC Business Environment have been successfully used within the industry for a number of years, they are now considered dated and in need of review. Some of the problems identified by QSIC include:

- They are considered long and difficult to use.

- They were originally written for writing data to disc that was distributed as a CD copy, and not for the online environment.

- They aim to restrict use rather than support wider use.

- There are many derivative licences – or licences that have been adapted from the standard licences and which are now not considered to be a ‘standard QSIC licence’. The practice of adapting standard licences to create customised licences requires individual legal advice and input for many routine transactions – adding to delays in delivering data and services to authorised users.

- There is some variation in the legal frameworks used and agencies can consider themselves as individual business entities, rather than distribution points for the single business and legal entity that is the Queensland Government.3

3563.11 A survey of existing licensing practices adopted by Queensland Government agencies conducted in Stage 1 of this project indicated variations in licensing practices. Significantly, almost two-thirds of government business units (63%) release data without any licence in place. Of these:

- 63% use workflow processes

- 21% use Information Standards

- 21% use copyright statements

- 26% aggregate data for confidentiality and privacy

- 21% apply caveats and disclaimers

- 5% use memorandums of understanding

- 10% rely on ‘relationships’.

Of the 37% of government business units who do use licences:

- 63% use dated arrangements (e.g. Queensland Spatial Information Strategy (QSIS) licences)

- 27% use deeds of confidentiality

- 36% use adapted current licensing (the Department of Natural Resources and Water, AEShareNet etc)

- 9% apply copyright statements

- 27% use memorandums of understanding for cross-agency data access.

3.12 With the variety of licences, transaction types and licensing processes on offer, it can be complex for businesses, community members and individuals to deal with the Queensland

357Government. It can also be difficult for Queensland Government departments to deal with each other and it can be more difficult for agencies to get information from another Queensland Government agency than it is for an external party to access the data and information. This has created confusion for clients and data custodians and has meant that it has been impossible to design the architecture for an online solution.

3.13 QSIC identified the need to update its suite of existing licences to enable more open access and use provisions for publicly available data and data sharing arrangements, and to introduce an online digital rights management system.

4. PROJECT SCOPE

4.1 Stage 2 of the project aimed to develop a Government Information Licensing Framework:

- to facilitate improved access to, and use of, government-held data and information to authorised users

- to establish a standard, single interface and licence system based on a standard set of terms and conditions for other levels of government and the private sector to access information about Queensland Government-held data and information

- to preserve the Queensland Government’s intellectual property

- to reduce legal risks to the Queensland Government associated with misuse of data and information products and services

4.2 The terms and conditions of the Government Information Licensing Framework are to:

- be applicable to the Government’s strategic information datasets

- be applicable to Queensland Government business units, in conjunction with other licences as necessary

- acknowledge the Queensland Government as a single business entity, and support cross-agency information access to support outcomes required under the Government’s priorities

- support distributed custodianship (across government and the private sector)

- for data assets, consider and clearly define the copyright, intellectual property rights (especially when data is integrated), security, privacy and confidentiality obligations, and other specific statutory and legal constraints

- define Digital Rights Management statements for individual digital datasets

- define the fitness for purpose of data and information, including the extent of Government liability in relation to use of the data and provide relevant disclaimers for liability and fitness for use

- be applicable to all access and distribution methods including the internet, data file distribution and hardcopy

- cater for commercial access of datasets and information products

- be scalable – one determination providing a set of rules for all information access and use

- incorporate existing Government Information Standards, including Information Standard No 25 – Intellectual Property (IS25), Information Standard No 33 – 358Information Access and Pricing (IS33) and Information Standard No 44 – Draft Data Custodianship (IS44).

4.3 These activities were undertaken during Stage 2:

- a series of consultations with key data custodians to identify current licensing practices and to review these practices against the range of available CC licences

- discussions with other interested organisations – Creative Capital Victoria, the Office of Spatial Data Management, the Australian Government Information Management Office and Creative Commons California (US)

- presentations were provided to the Unlocking IP Conference, held at the University of New South Wales and to the Spatial Sciences Institute NSW and Tasmania Regional Conferences – GIS Evolutions 2006

- analysis of current licensing arrangements being utilised by agencies

- consultation with agencies about the identified benefits of moving to the CC suite of licences

- background research

- review of policies and standards

- review of technical implementation of a digital rights management system.

4.4 This project was guided by advisors including:

- Professor Brian Fitzgerald, Head, School of Law Queensland University of Technology (QUT)

- Steve Jacoby, Chair, QSIC

- Dr Peter Crossman, Queensland Government Statistician

- Neil Lawson, Executive Director, Land Information and Titles, Department of Natural Resources and Water

- Keith Millman, Commercial Counsel, Legal Services Unit, Queensland Treasury

- Dr Anne Fitzgerald, Adjunct Professor, School of Law QUT

- Tim Barker, Assistant Government Statistician and Director, Queensland Spatial Information Office, Office of Economic and Statistical Research.

4.5 QSIC funded the secondment of Neale Hooper, Principal Lawyer, Crown Law, Department of Justice and Attorney-General to act as legal advisor and Principal Project Manager for Stage 2 of this project.

4.6 QUT provided in-kind support to the project through the legal and other advice provided by Professor Brian Fitzgerald and Dr Anne Fitzgerald and through the contribution of Brendan Cosman in assessing requirements for the technical implementation. Dr Anne Fitzgerald also undertook significant background research for the project, and analysed existing licences identified by agencies.

4.7 The Department of Natural Resources and Water provided in-kind support by offering Dr Anne Fitzgerald one day per week for the duration of the project. Graham McColm, from Information Policy, Department of Natural Resources and Water, assisted during Stage 2, by providing workshop presentations and analysing licences provided by agencies. QUT provided Brendan Cosman, who was funded by Information Queensland to assist the project with an 359assessment of issues associated with the technical implementation of the digital rights management system.

4.8 Stage 2 excluded implementation, expected to be conducted during Stage 3 as a pilot project with key agencies to validate the general operational and legal appropriateness of the created terms and conditions.

5. CREATIVE COMMONS

5.1 The CC model identified in Stage 1 is considered a best-practice example of open content licensing systems. Examples of other open content licences include AEShareNet and the BBC’s Creative Archive. (For a more detailed explanation of these licences see Attachment 2 – Overview of Open Content Licence Types and Attachment 6 – Background Research.)

5.2 The CC concept was developed by Professor Lawrence Lessig, Professor of Law at Stanford Law School, a proponent of reduced legal restrictions on copyright, trademark and radio frequency spectrum, and technology applications.

5.3 CC licences are based on the full range of exclusive rights that are conferred on copyright owners of the various categories of works and subject matter protected under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). CC defines a spectrum of models which can be used by copyright owners in exercising the bundle of exclusive rights, ranging from ‘copyright’ where all rights are reserved by the creator, to ‘public domain’ where no rights are reserved by the creator. It allows creators to reserve some rights, to retain copyright and have their intellectual property protected while also inviting further sharing and use of the work. However, there is an important exception to the range of situations in which CC licences can be used. They cannot be used to license copyright material if the copyright owner has applied a technological protection measure to preclude unauthorised use of the material. CC licences are not excluded from being used where the copyright owner has included Electronic Rights Management information in the protected material (see further below at paragraph 5.5).

5.4 CC includes a predetermined set of licensing terms and conditions written in three ways – in plain English, in legal terms, and in technical terms. It minimises administration by providing a consistent and transparent legal framework for all information resources.

5.5 CC licences are given effect online through a subset of digital rights management referred to as ‘Electronic Rights Management’. Digital rights management is a systematic approach to copyright protection for digital media which was created to prevent piracy of commercially marketed material and illegal distribution of paid content over the internet. Electronic Rights Management information is protected by Australian copyright law. The Electronic Rights Management information is used to ‘tag’ the media (as well as the web page which links to the media), which allows people and computer programs (such as search engines) to determine the licence attached to the media.

5.6 A central feature of open content licences is that the material in question is protected by copyright, which consists of rights that can be exercised exclusively by the copyright owner. Copyright automatically gives copyright owners a bundle of rights which are described as ‘exclusive’ because they enable the copyright owner to exclude others from doing certain acts in relation to the protected material. The bundle of exclusive rights that make up copyright varies according to the kind of material protected, with the most important rights being those to reproduce, to electronically communicate to the public and to make an adaptation of the material. Since the enactment of the Copyright Amendment (Digital Agenda) Act 2000 (Cwlth), 360copyright owners also have the rights to protect their materials against unauthorised use by applying technological protection measures, and Electronic Rights Management information. Open content licences involve the granting of permission to other persons to use the copyright material in ways that fall within the bundle of exclusive rights belonging to the copyright owner. In other words, they authorise (permit) users to do certain specified acts within the scope of the bundle of rights which can be exercised exclusively by the copyright owner. Importantly, open content licences grant users rights to do acts that fall within the scope of the copyright owner’s exclusive rights and do not impose further (i.e. non-copyright related) obligations on the users of the copyright material. In this respect, open content licences differ from many traditional information licences which seek to impose, by means of a contract between the copyright owner and the recipient, additional obligations or constraints on users (e.g. limitations on re-use or confidentiality requirements).

5.7 CC has been adapted for use in over 40 countries, including sections of the US, UK, South African and other governments, and not-for-profit organisations.

5.8 CC licences can be applied to a range of materials, including text, books, photographs, music and spatial data. In November 2005, Google introduced a specific CC search facility to enable searchers to locate materials available under the suite of CC licences.

5.9 Australian versions of the CC licences were developed in January 2005 in conjunction with iCommons, which oversees the internationalisation of the CC idea. The Australian CC licences enable creators to license works under Australian copyright law, which differs from the US copyright law in certain important respects. For example, under US copyright law no copyright subsists in Federal government materials. In substance, US Federal government materials are part of the public domain. The Australian CC licences are available from the CC website creativecommons.org/worldwide/au/. The four categories of licence available are:

|

Attribution: The work is made available to the public with the baseline rights, but only if the author/custodian receives proper credit. | |

|

Non-commercial: The work can be copied, displayed and distributed by the public, but only if these actions are for non-commercial purposes. | |

|

No Derivative Works: This licence grants baseline rights, but it does not allow derivative works to be created from the original. | |

| Share Alike: Derivative works can be created and distributed based on the original, but only if the same type of licence is used, which generates a ‘viral’ licence. These can be combined to create six licences: |

- Attribution 2.5

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/au/ - Attribution-NoDerivs 2.5

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.5/au/ - Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/au/ - Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/au/ 361 - Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/au/ - Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/au/

5.10 The Australian versions of the CC licences set out the same basic licensing elements as the international CC licences, but in language tailored to the Australian legal system. In addition, the Australian licences address the moral rights granted to certain authors under Australian copyright law. Similar moral rights do not exist in all other overseas jurisdictions and hence are not included in the generic CC licences. As a result, the Australian CC licences contain an additional restriction, in that a licensed work cannot be used in a manner that is derogatory or prejudicial to the original author’s reputation, in accordance with the author’s right of integrity.

5.11 The development of the Australian version of CC was led by Tom Cochrane, Deputy Vice Chancellor QUT, Professor Brian Fitzgerald, Head, School of Law QUT, and Ian Oi, Blake Dawson Waldron Lawyers. Professor Brian Fitzgerald has an international reputation in the area of Cyberlaw, Technology and Intellectual Property. QUT is also home to the Faculty of Creative Industries, which is keen to use the CC model to further develop innovation in the creative industries, the Faculty of Information Technology, which is a leader in information security, and the Faculty of Business, which has recognised expertise in technology policy and innovation.

5.12 QUT is the leading agency in Australia for CC and the OAK Law Project. The OAK Law Project was funded by the Commonwealth Department of Education, Science and Training and evolved out of the CC initiative to enable online licensing of research results, papers and publications arising from publicly funded research conducted at participating Australian universities. The OAK Law Project produces ‘nationally and internationally applicable legal protocols and licences based on the CC model that can be used to facilitate open access to copyright material’. On the 28 September 2006 the OAK Law Report Number 1 was released which investigates a legal framework that supports open access to Australian academic and research outputs such as datasets, articles and electronic theses and dissertations. This report explains that with the rise of networked digital technologies our knowledge landscape and innovation system is increasingly reliant on best practice copyright management strategies.4

5.13 CC licences are not suitable for use in relation to certain information transactions, including where:

- access to and use of data is restricted due to the confidential, private or classified nature of the data and where specific conditions of use would be agreed between the provider and recipient prior to access and use

- rights to access and use data are given as part of high-value commercial transactions, which involve negotiation of the terms of access and use between data providers and recipients.

362Transactions of this kind are typically governed by legal agreements, licences, contracts or memoranda of understanding designed to maintain the confidentiality or privacy of the information or to secure its commercial value.

6. RATIONALE FOR NEW APPROACH

6.1 There is an increasing amount of activity, at national and international levels, to enable information and content generated or held by public sector institutions and publicly-funded universities and research institutes to be more readily accessed and re-used.

6.2 Although attention has been given to improving access to public sector information since the 1980s, efforts to facilitate access and re-use have strengthened in recent years. As well as advances in computing technology, an important contributing factor has been the body of economic research over the past decade which points to the advantages to be gained.5 This trend is in recognition of the potential social and economic value of public sector datasets, databases and other informational products, articulated by key authors in this area – Carl Shapiro and Hal Varian, Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy (1999), Peter N. Weiss, article from US Department of Commerce, ‘Borders in Cyberspace: Conflicting Public Sector Information Policies and their Economic Impacts’ (2002), PIRA International Ltd, Commercial Exploitation of Europe’s Public Sector Information (2000), commissioned by the European Commission Directorate-General for the Information Society, and Stiglitz et al., ‘The Role of Government in a Digital Age’ (2000), Computer and Communications Industry Association, Washington, DC. (For more information on the economic benefits of open content licensing see Attachment 7 – Economic Benefits.)

6.3 Internationally, one of the most significant initiatives in recent years has been the European Union’s Directive on the re-use of public sector information (‘the EU Directive’), which was adopted by the European Parliament and Council on 17 November 2003.6 The EU Directive, which aims to facilitate the development of European data products based on public sector information, was the culmination of efforts that began in the late 1980s.7 With a lack of clear policies or uniform practices in relation to access to and re-use of public sector information, European content firms dealing in the aggregation of information resources into value-added information products were perceived to be at a competitive disadvantage in comparison to their US counterparts. The lack of harmonisation of policies and practices regarding public sector information resources among the European Union Member States was regarded as a barrier to the establishment of European information products based on information obtained from

363different countries.8 By contrast, the situation in the US was seen as providing extensive opportunities for the re-use of public sector information, due to a legislative framework which enhances access to and re-use of federal government information. Features of the US legal framework which were identified as contributing to the advantageous position of US firms include the broad right of citizens and businesses to electronically access Federal government information and re-use it for commercial purposes, the lack of copyright on Federal government materials, the lack of restrictions on re-use and the limitations of fees to marginal costs of reproduction and dissemination.9

6.4 European Union Member States were required to bring their national laws into conformity with the Directive by 1 July 2005 and to review the application of the Directive by 1 July 2008.10,11 By 15 December 2005, 12 countries (including France, Ireland, Italy, Sweden, the Netherlands and the UK) had notified the European Commission that they had given effect to the Directive.12 In the UK, the Directive has been given effect by the Re-use of Public Sector Information Regulations 2005, which came into force on 1 July 2005, and in May 2005 the UK government established an Office of Public Sector Information with responsibility for the coordination of policy standards on the re-use of public sector information.13,14

6.5 An independent study undertaken in the United Kingdom by Intrallect Ltd, initially a spinoff company from the University of Edinburgh, and the AHRC Research Centre for Studies in IT and IP Law at the University of Edinburgh considered the applicability of CC licences to facilitate access to and re-use of significant public sector information.15

3646.6 It is also worth noting that The Gates Foundation now requires data sharing as a condition of its new funding program for a HIV/AIDS vaccine. The Gates Foundation requires all grantees to share their data to accelerate research and make available to all who can use it.16

6.7 In November 2005, Australian Government agencies – the Office of Strategic Data Management and the Australian Bureau of Statistics – abandoned their longstanding, ‘traditional’ restrictive government licensing practices in relation to their datasets, which included charging fees for the data and severely restricting or prohibiting commercial downstream use of the data by the licensee or others. This is an indication that, at the Australian Government level, there is a move to the philosophy of the open content licensing, and the removal of certain data charges and restrictions on downstream use of data, whether commercial or otherwise.

6.8 The current licence agreement being used by these agencies for online access to, and the download and further use of, their data resembles an open content licence as it grants very broad rights to use and sub-license data (commercially or otherwise), and requires that the Commonwealth be recognised as owner of the intellectual property rights in the dataset.

6.9 Two of several departures from a typical open content licence are that the licence requires an indemnity and obliges certain record keeping and reporting, but with reports only to be provided on reasonable request by the agency.

6.10 Put simply, these fundamental changes in access and management practices represent a major paradigm shift on the part of these Australian Government agencies and a significant step towards embracing the open content licensing principles and philosophies of only ‘some rights reserved’ as opposed to the traditional copyright ‘all rights reserved’ licence. The main feature of open content licensing models, including CC, is the requirement for the acknowledgement or attribution of copyright ownership and then the granting of a range of generous rights of use.

6.11 This fundamental change in Australian Government licensing practice coincided with the release of the report Unlocking the Potential: Digital Content Industry Action Agenda, Strategic Industry Leaders Group report to the Australian Government, November 2005.17 This report identified three key issues in relation to intellectual property, including low levels of industry knowledge about managing intellectual property, the importance of effective intellectual property management to build revenue in firms, and insufficiently developed mechanisms for accessing Crown intellectual property for exploitation. The report also proposed solutions, including engaging with work occurring in the area of alternative approaches to intellectual property licensing, such as CC, and developing ways of improving access to Government intellectual property for commercial exploitation by digital content firms to encourage innovation.

6.12 This report contains a strong encouragement for the broader uptake of the CC licensing regimes by Australian Government agencies in relation to ‘Crown intellectual property’. Whilst the recommendations contained in the Unlocking the Potential report are not official government policy there is a push by the Australian Government to have its intellectual property promoted within the private sector to support industry growth.

3656.13 Stage 2 of this project indicates that the CC licensing regime, and open content licensing more generally, will be of value to Queensland Government agencies, Queensland businesses and community members by enabling increased access to and re-use of public sector information (including spatial or mapping information), and will facilitate economic activity and better informed decision making generally, and foster the development of the information industry in Queensland.

7. CONSULTATIONS

7.1 Consultation workshops were conducted to provide key agencies with an overview of the findings from Stage 1, to outline the philosophy or principles governing open content licensing, to discuss the extent to which open content licensing, and CC in particular, might facilitate more efficient and effective licensing practices, and to identify the agency’s business needs. (For a more detailed report see Attachment 3 – Workshop Consultation Report.)

7.2 Workshops were conducted with data and information custodians from a range of Queensland Government agencies, including representatives from:

- Department of Natural Resources and Water – Indooroopilly, Information Policy, Products and Services, Land Information and Titling

- Environmental Protection Agency

- Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries

- Office of Economic and Statistical Research, Queensland Treasury

- Queensland State Archives

- Department of Public Works (Office of Government ICT)

- Smart Services Queensland

- Department of Justice and Attorney-General (Office of the Chief Information Officer, and Freedom of Information and Privacy Unit)

- State-wide Water Information Management Project, the Department of Local Government, Planning, Sport and Recreation

- Queensland Health

- QSIC Healthy Communities Working Group

- Information Queensland

- Australian Bureau of Statistics

- Commonwealth Office of Spatial Data Management

- Department of State Development, Trade and Employment

- GeoScience Australia

- Local Government Association of Queensland.

7.3 The workshops, and subsequent survey of participants, aided the analysis of existing licences used and assisted in identifying ‘gaps’ between the existing CC licences and current operational requirements.

7.4 Feedback from the workshops identified a clear demand for simpler and more standardised licences. It was also made clear by those attending the workshops that there was a need for 366some formality in licensing rather than informality and reliance upon ‘trusted relationships’. The consultation with agencies confirmed that the combination of the six CC licences would support the majority of data access and use transactions conducted by the Queensland Government.

8. ANALYSIS OF EXISTING LICENCES AND LICENSING ARRANGEMENTS

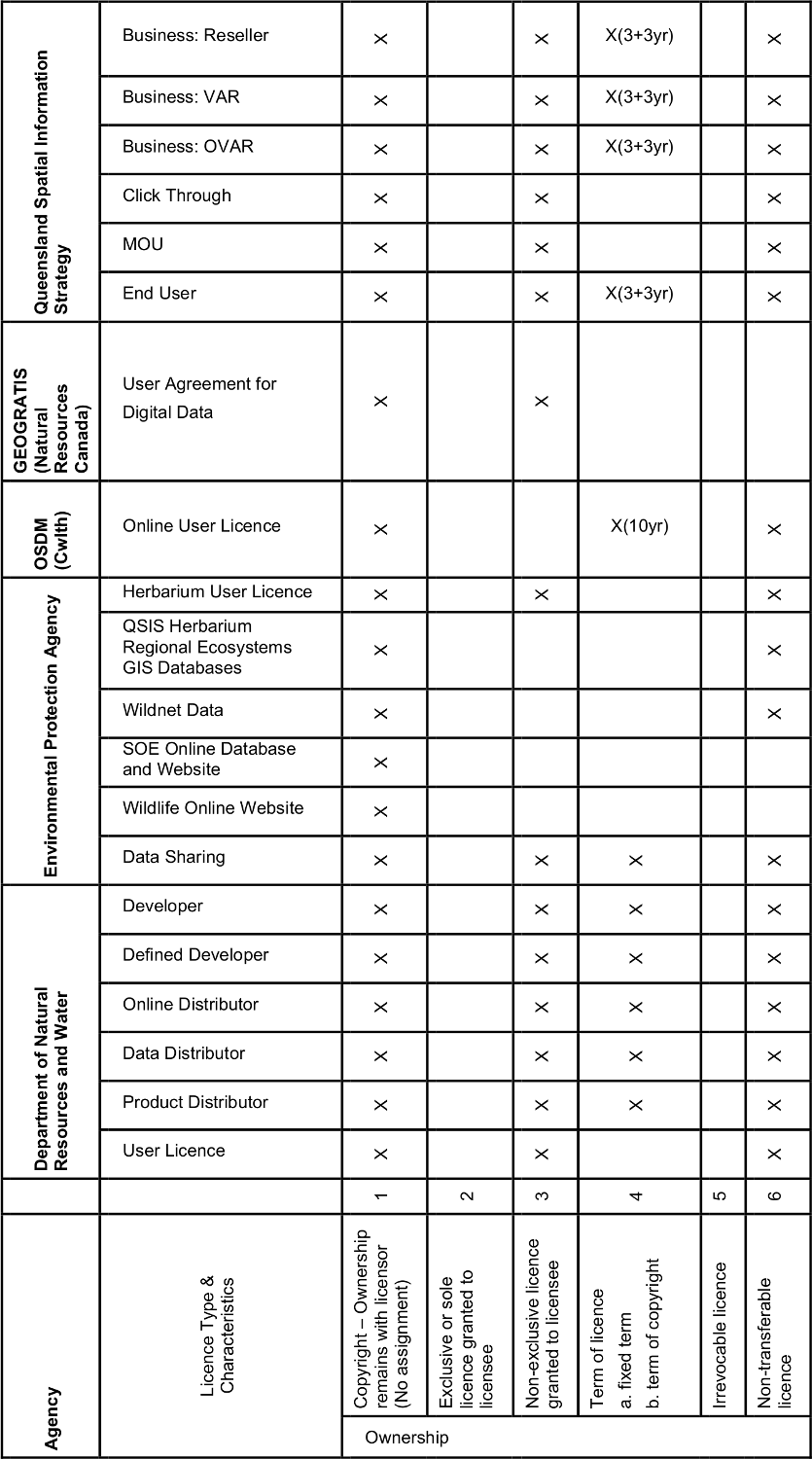

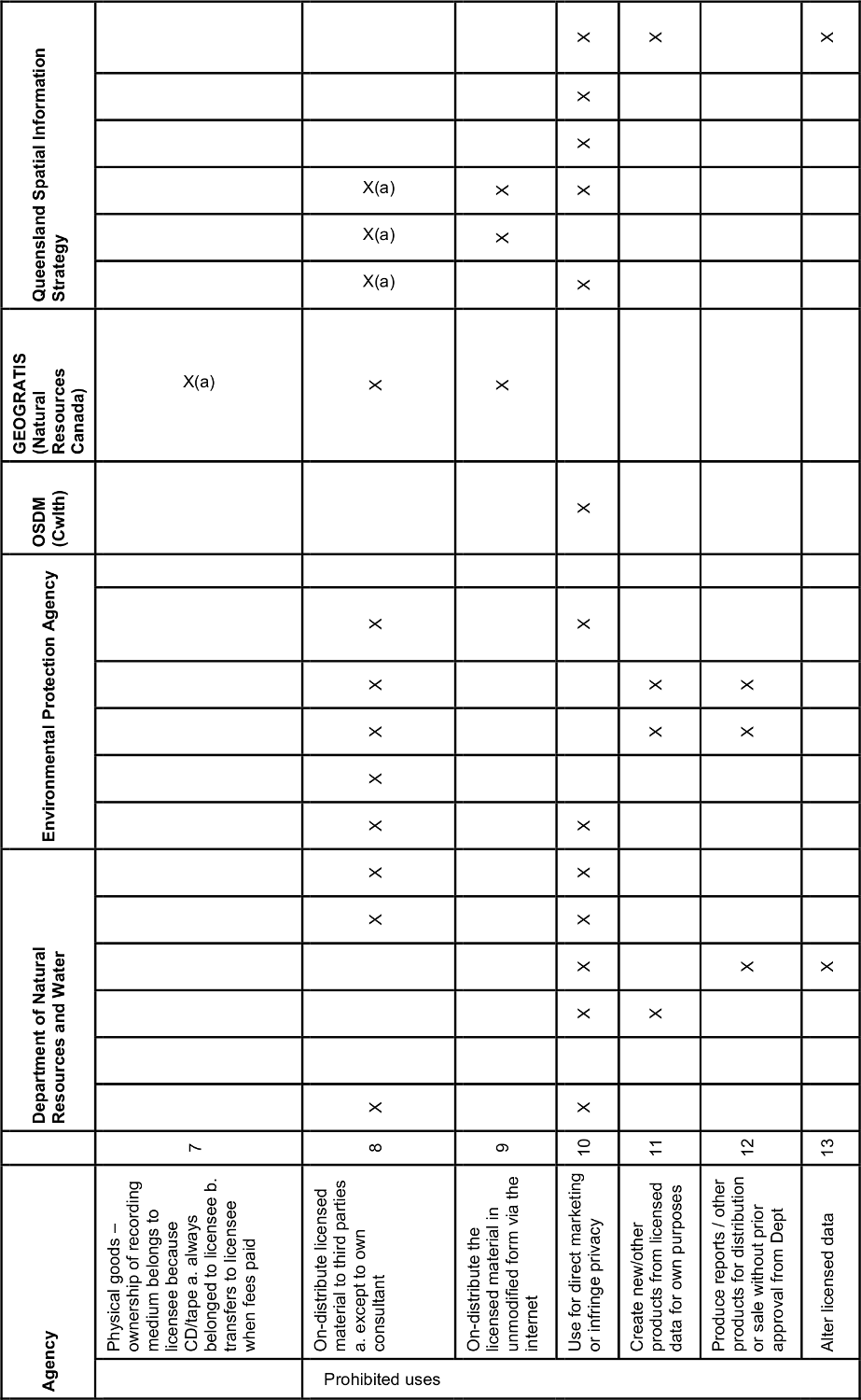

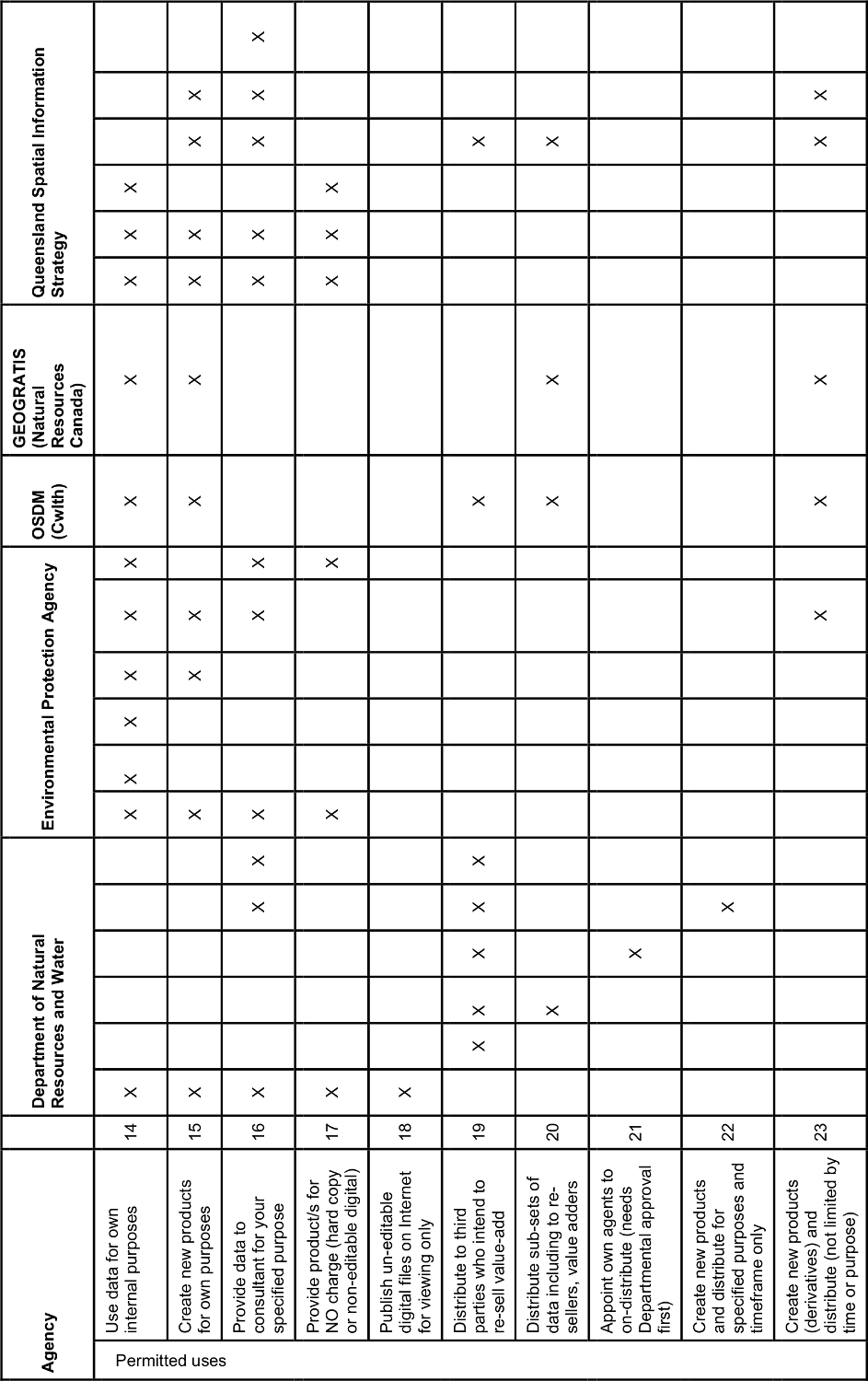

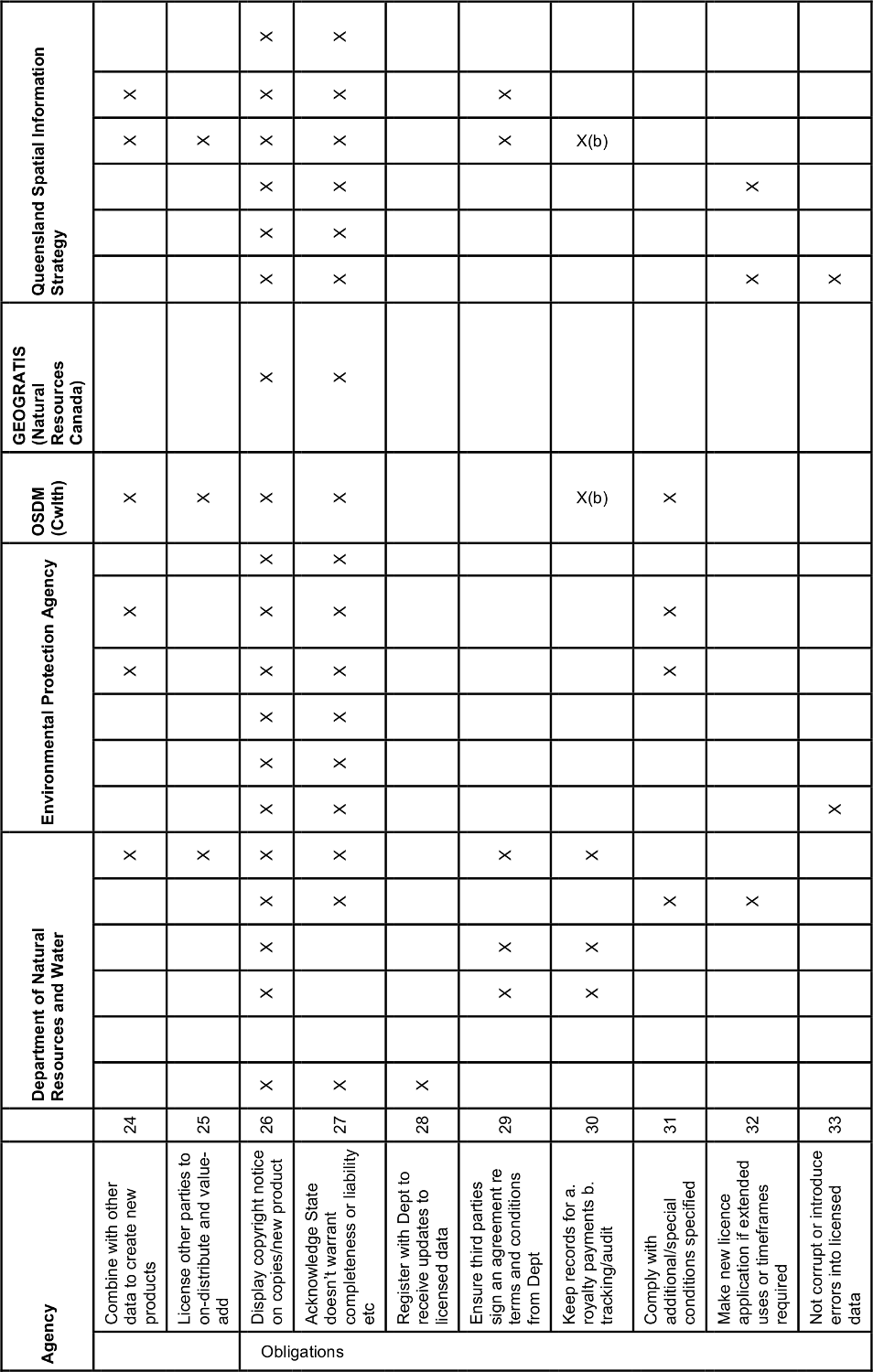

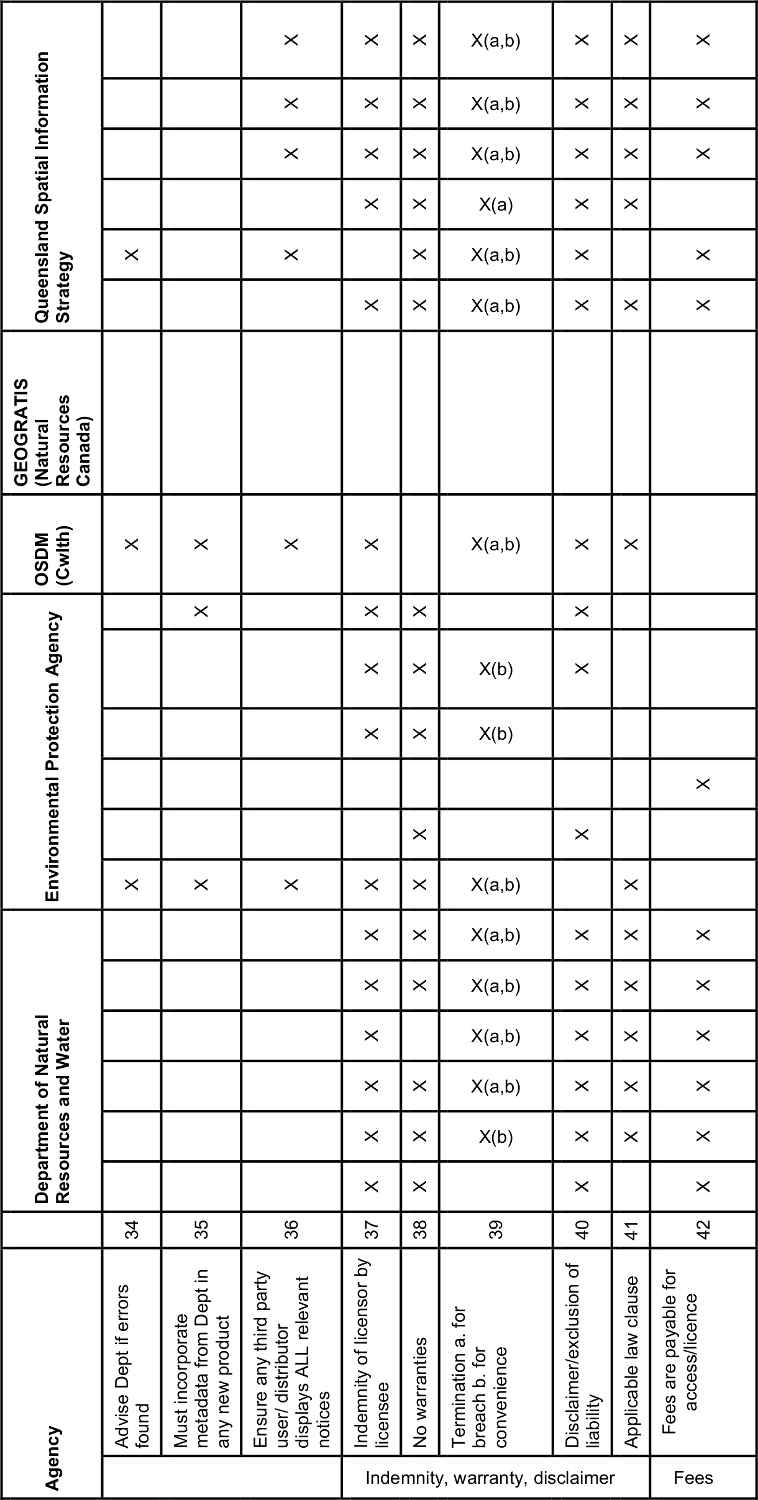

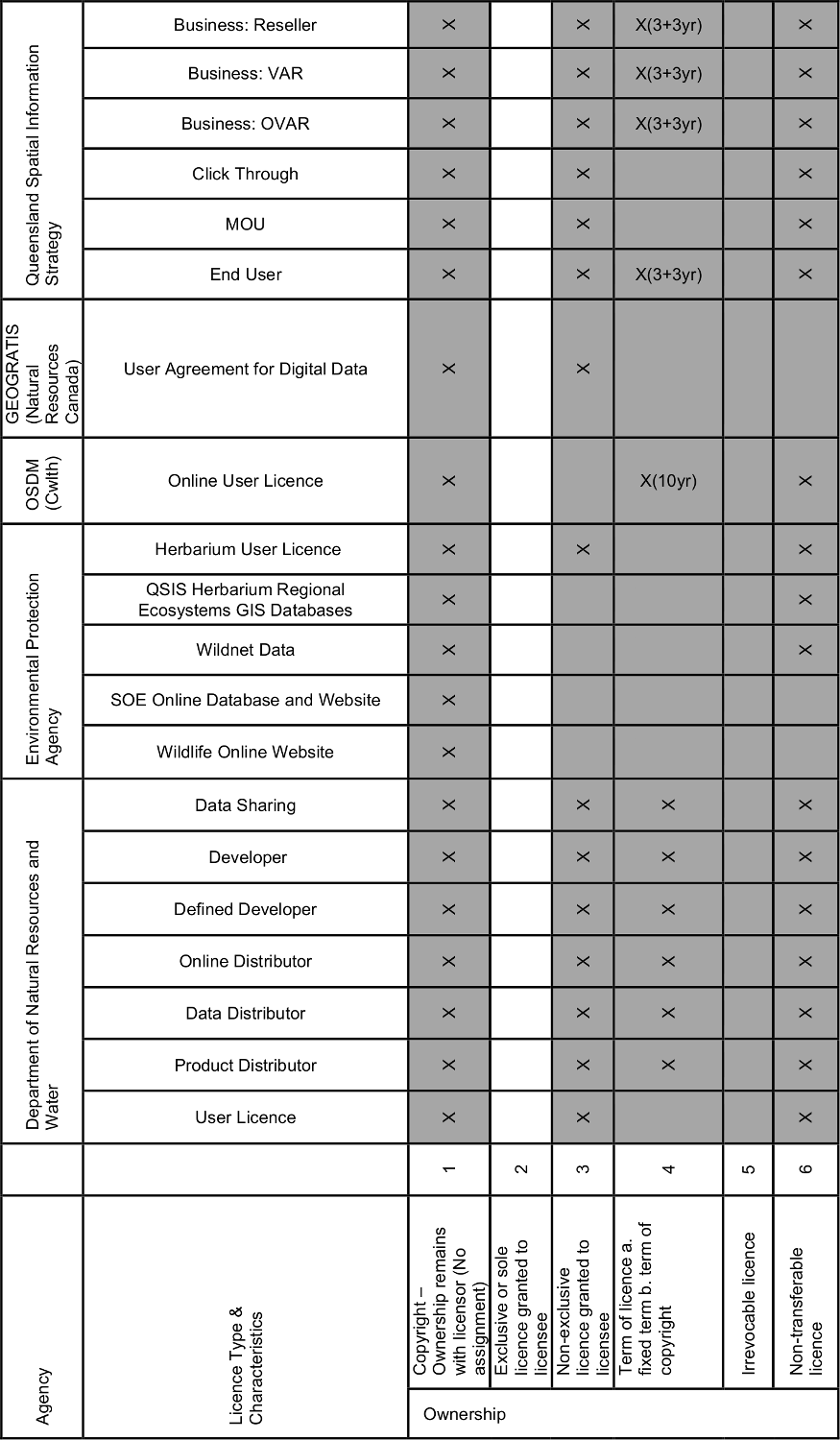

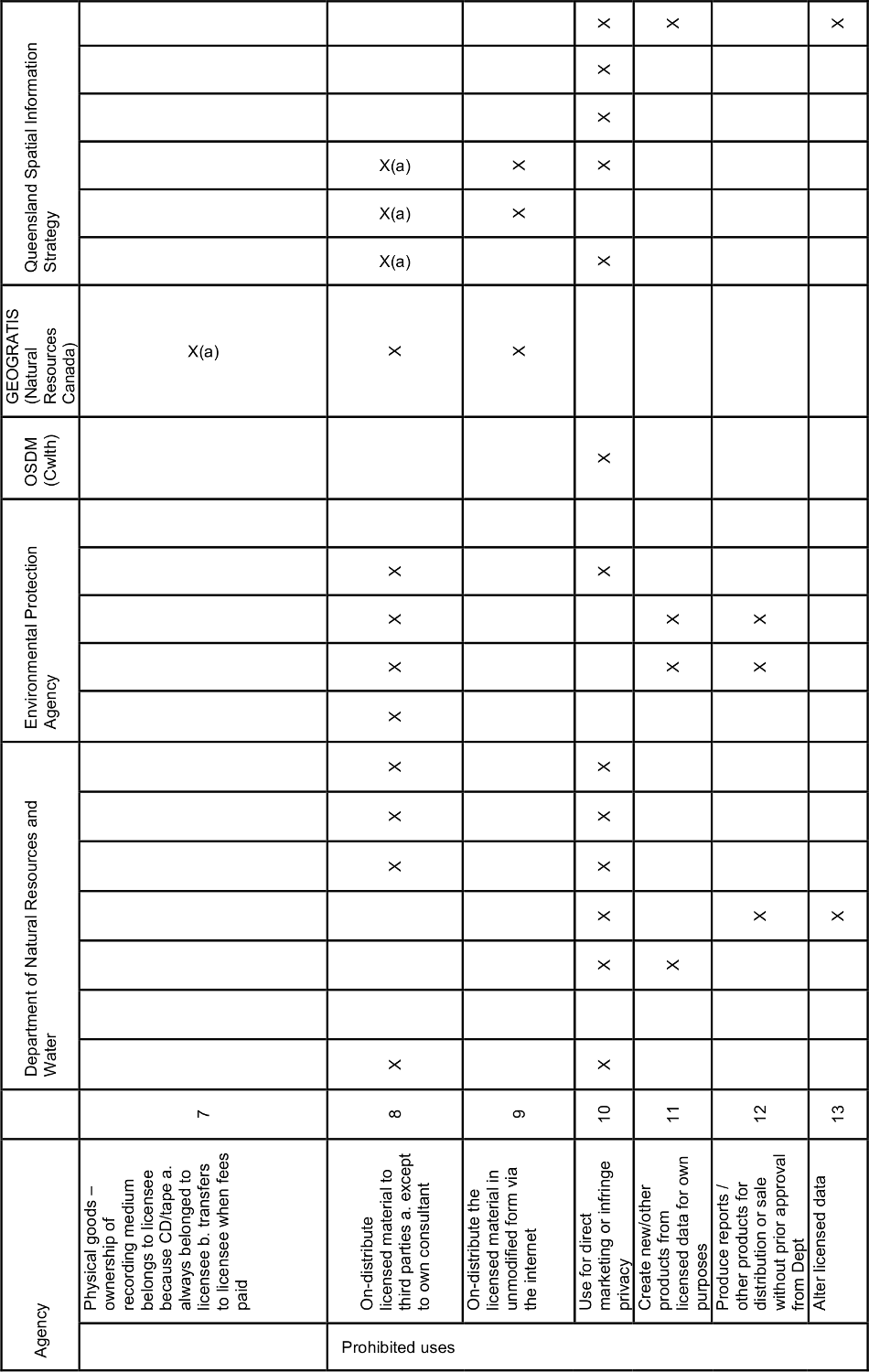

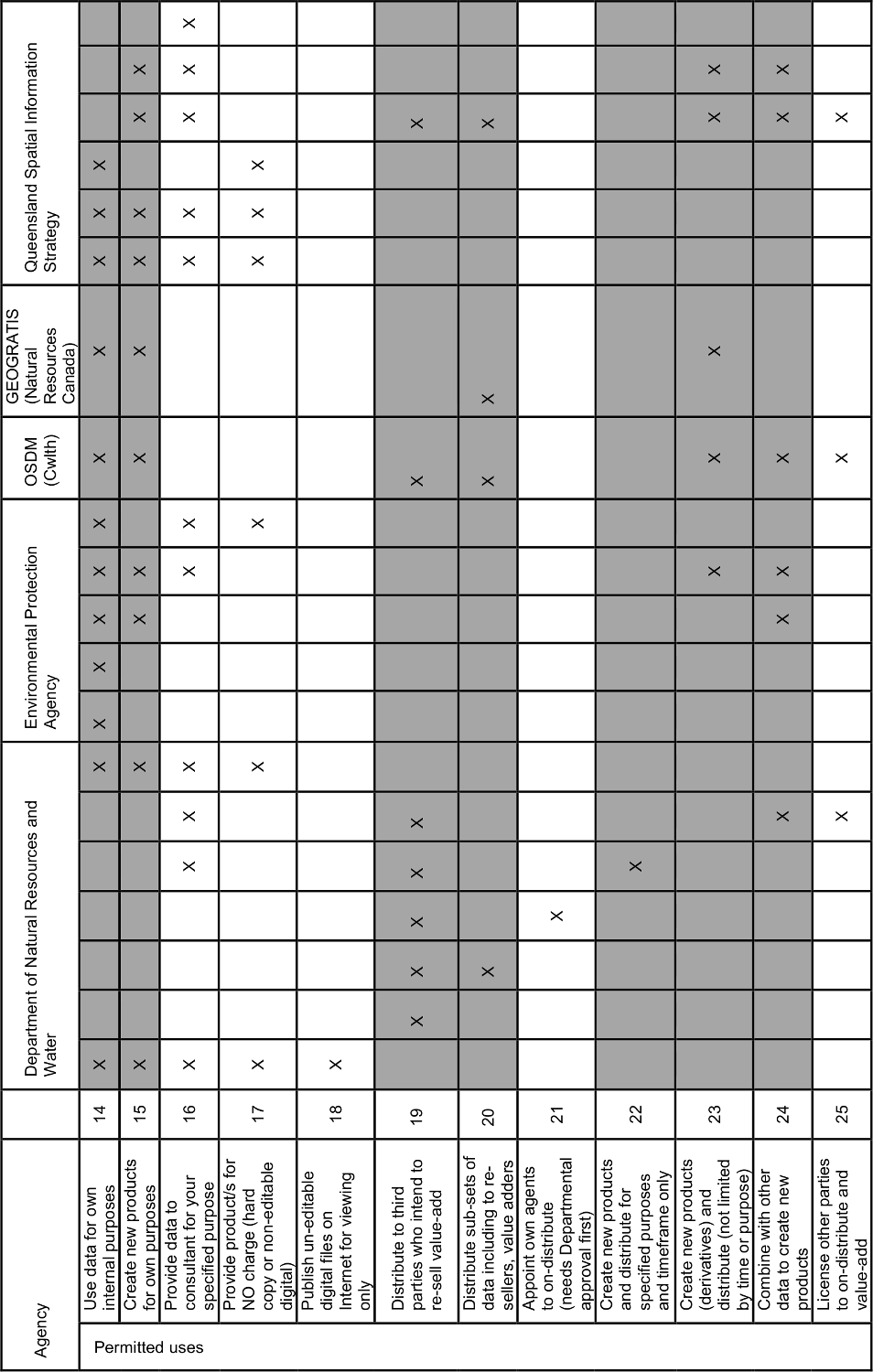

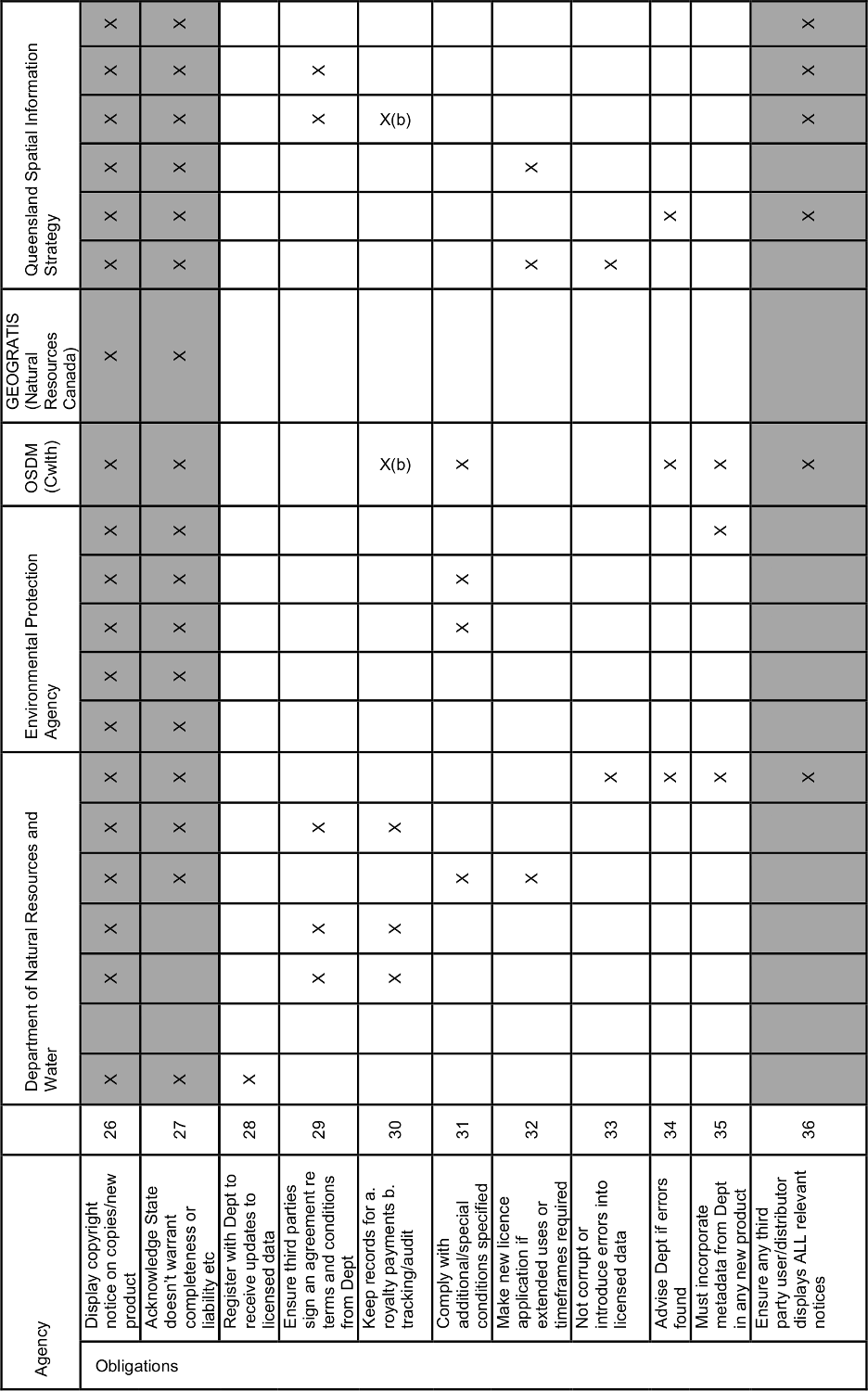

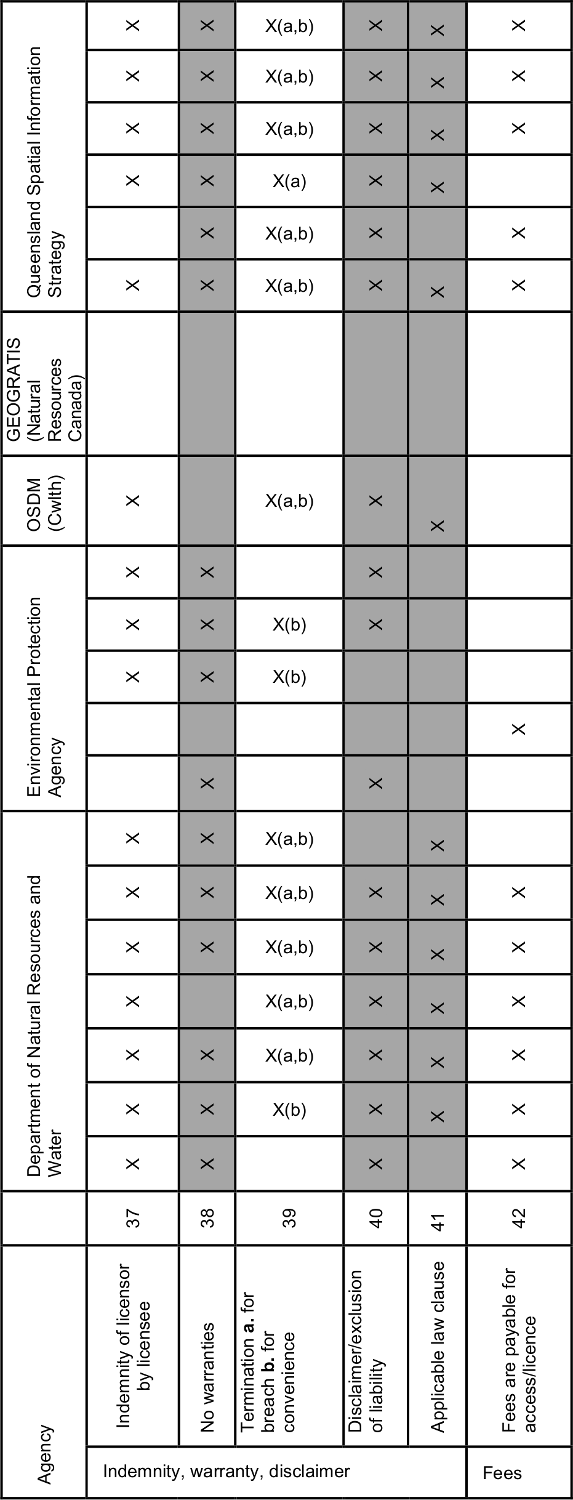

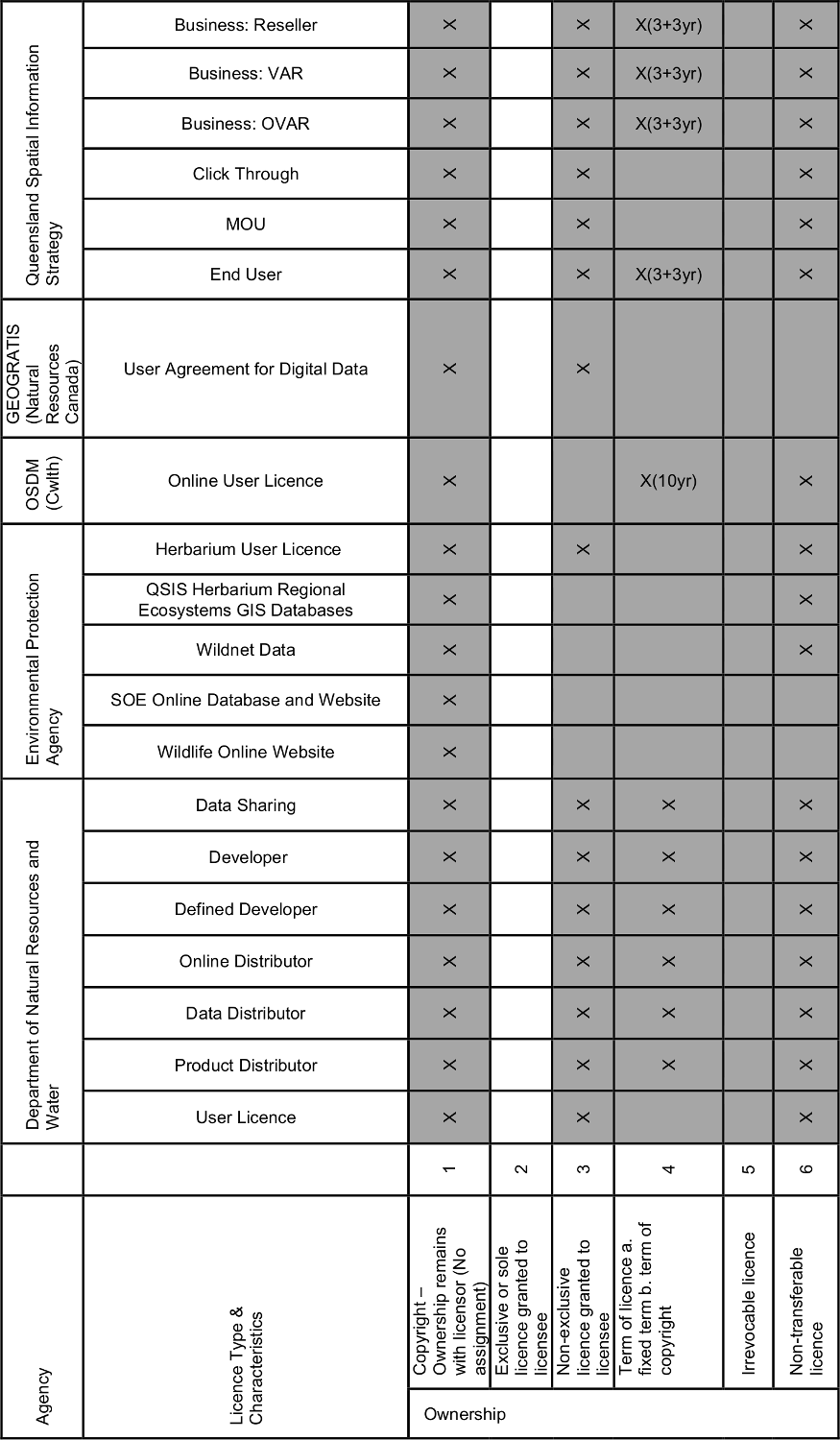

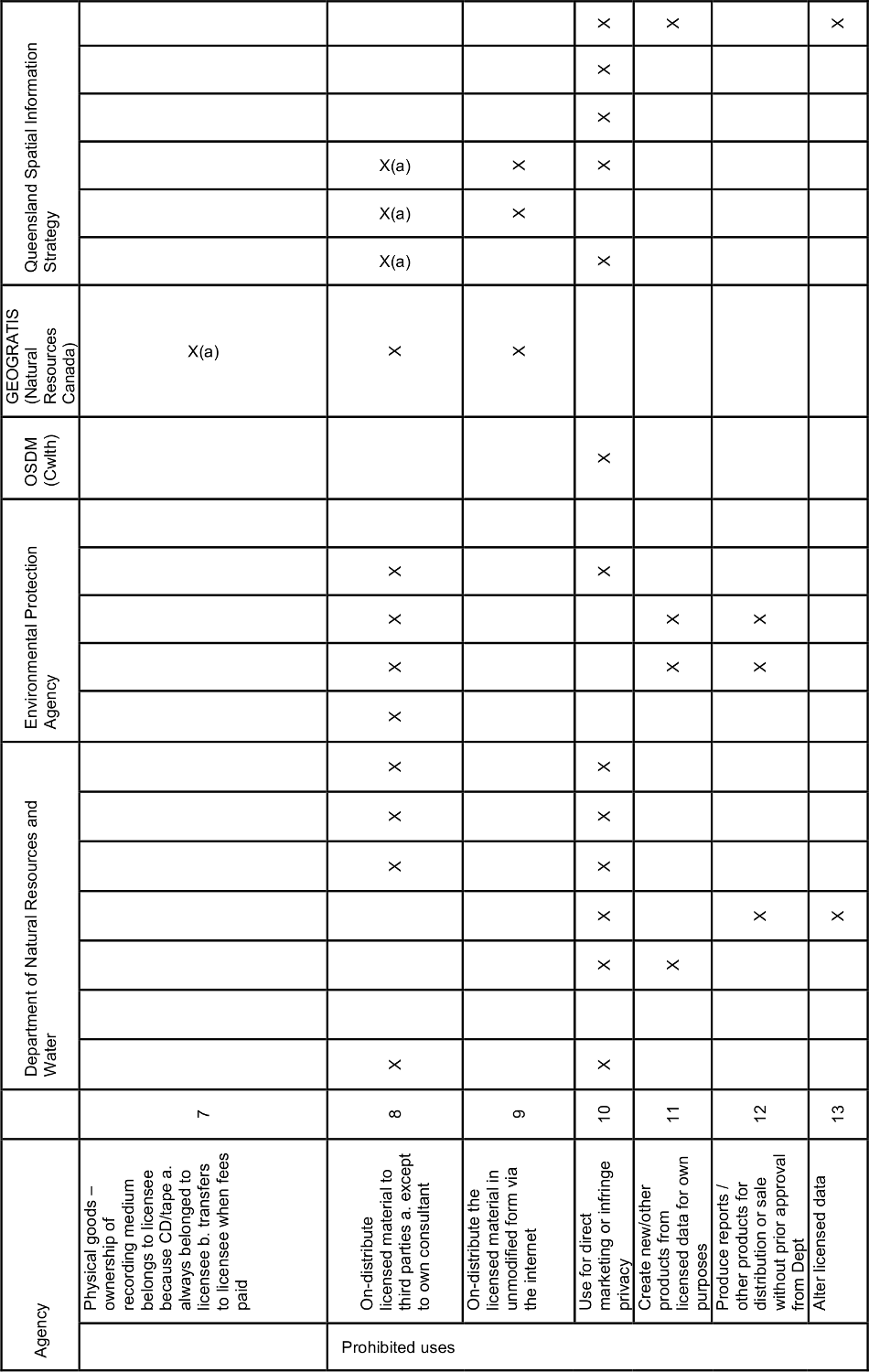

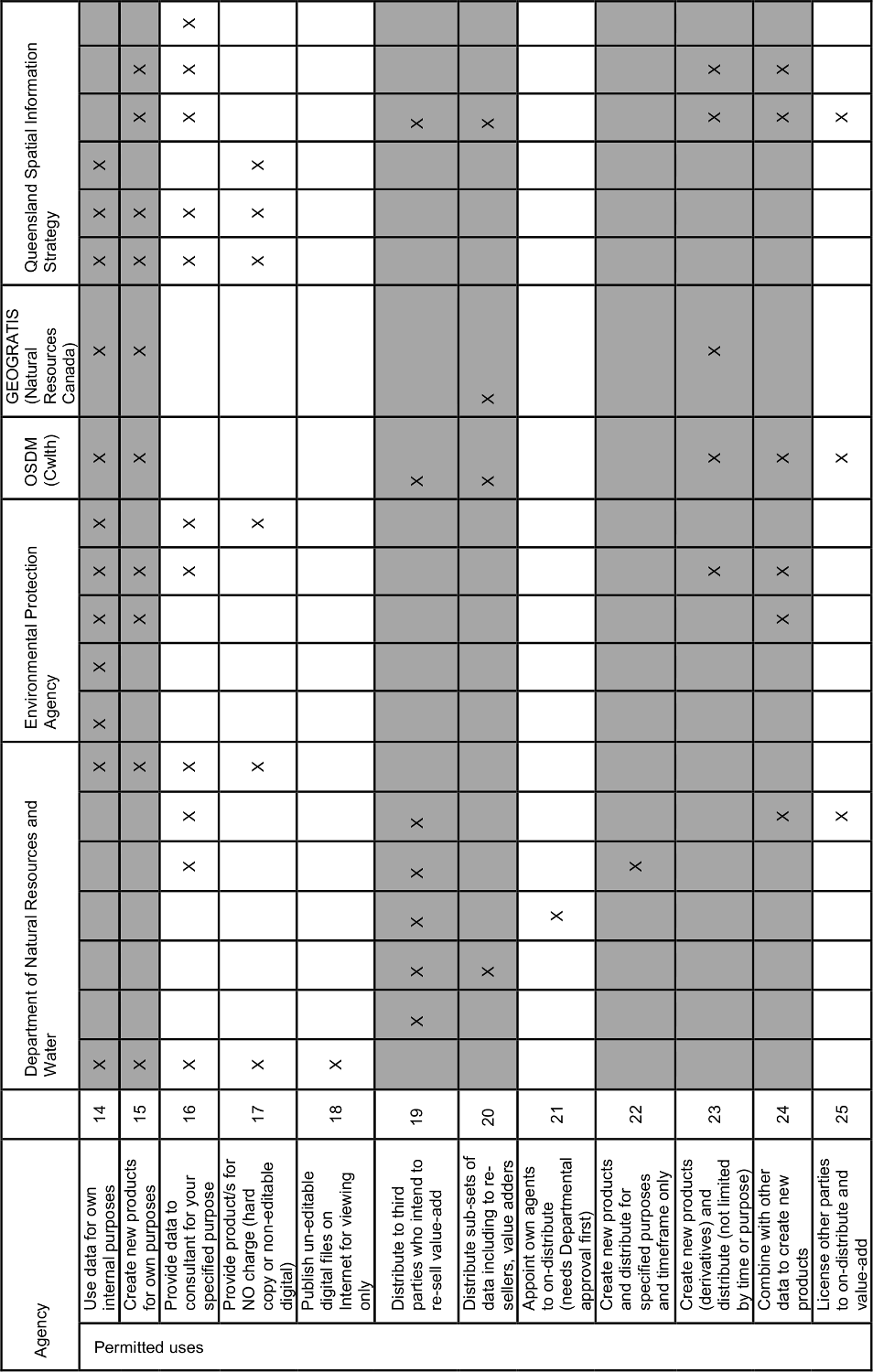

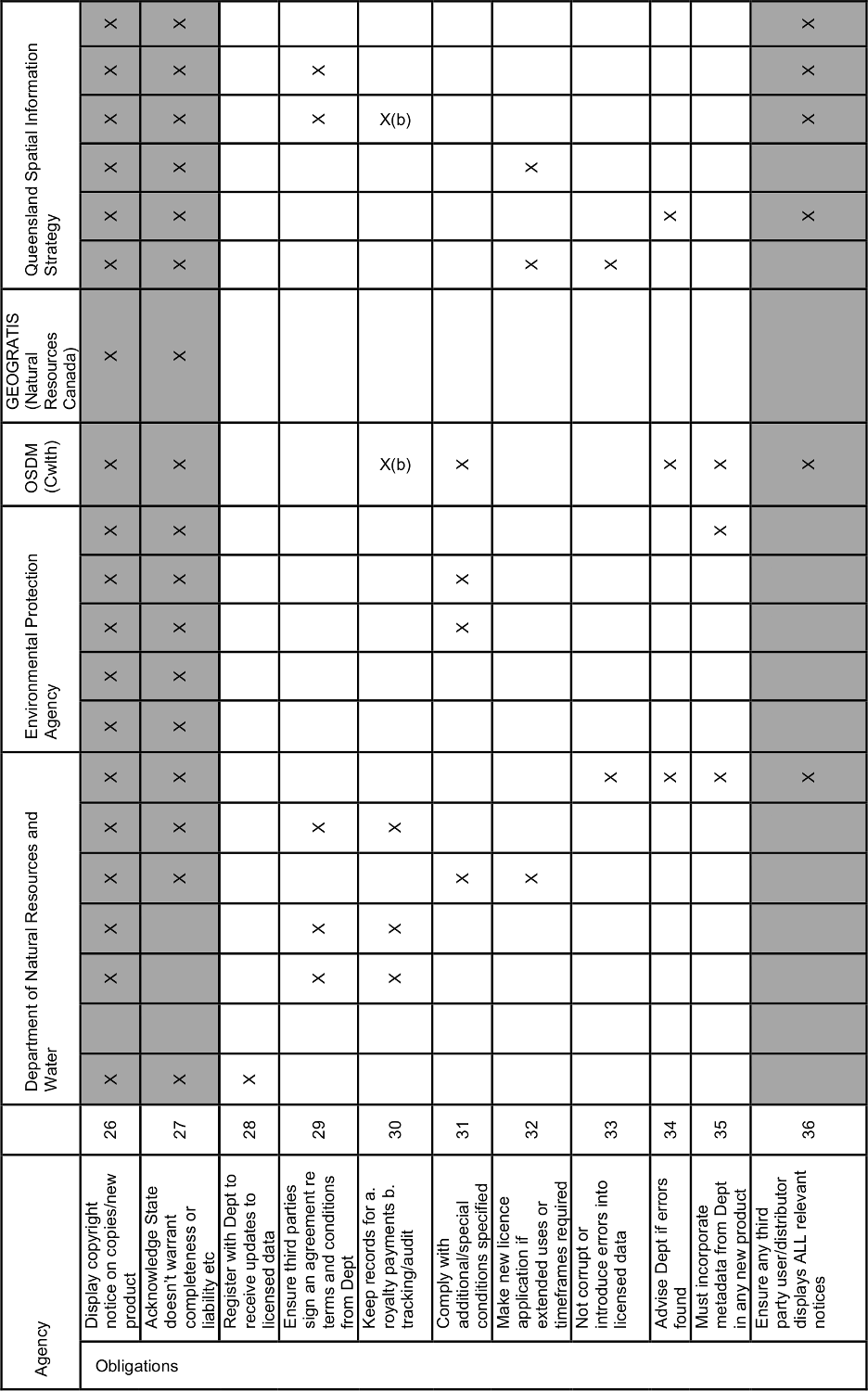

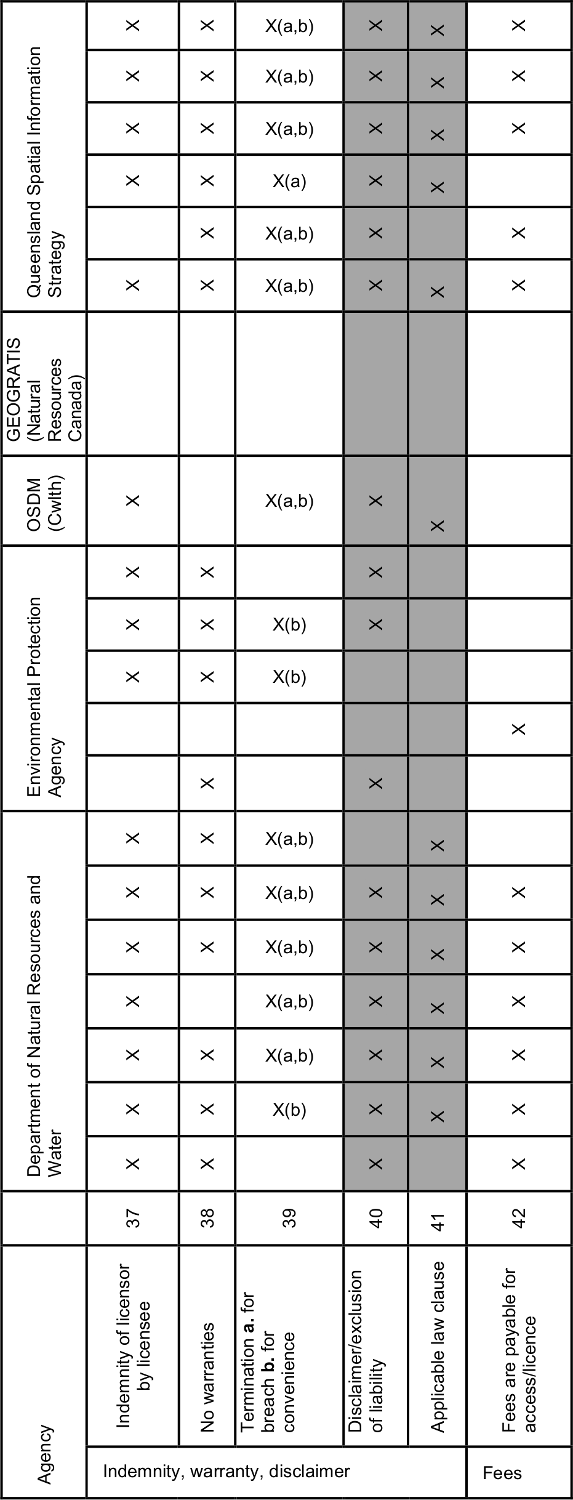

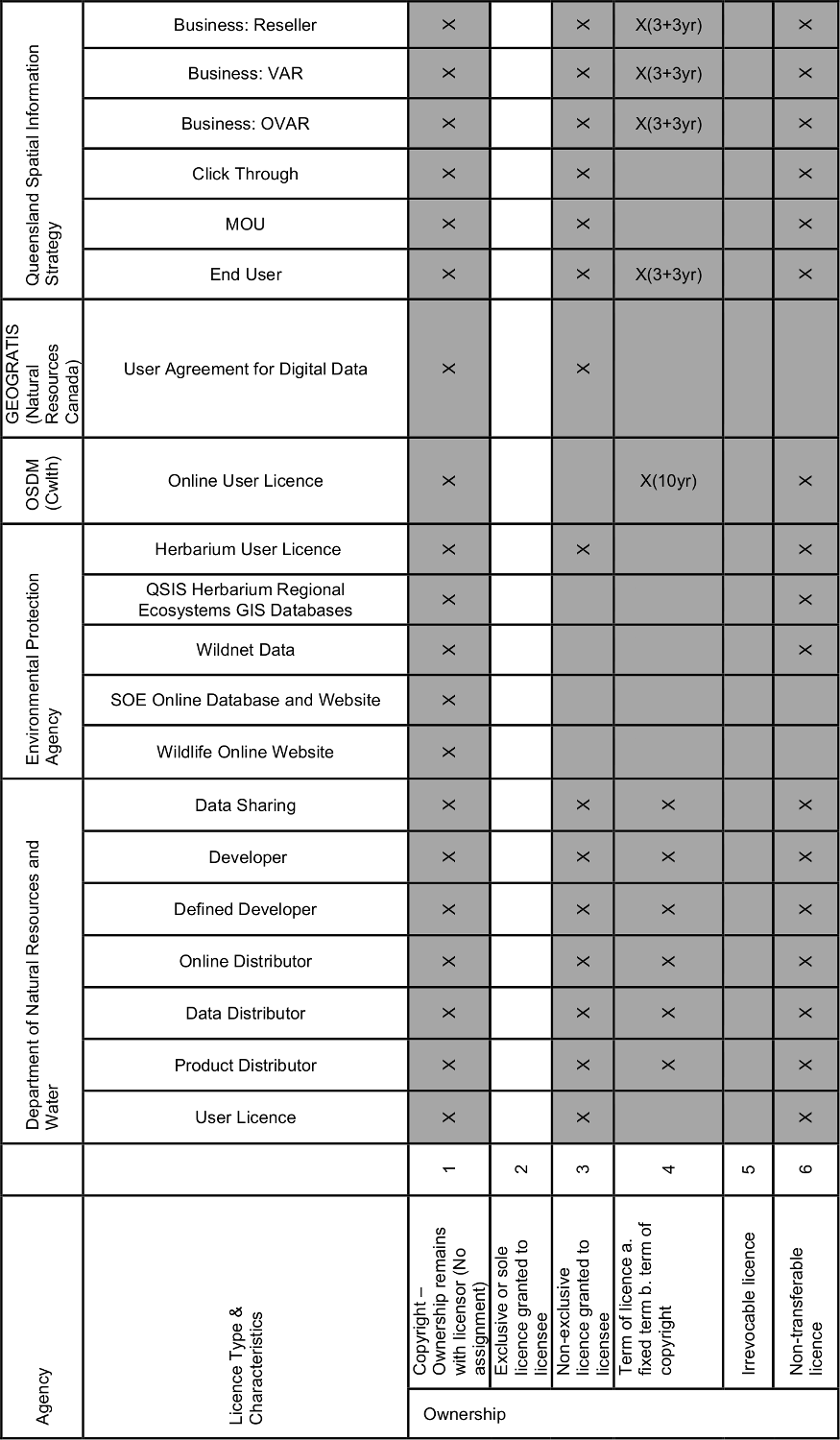

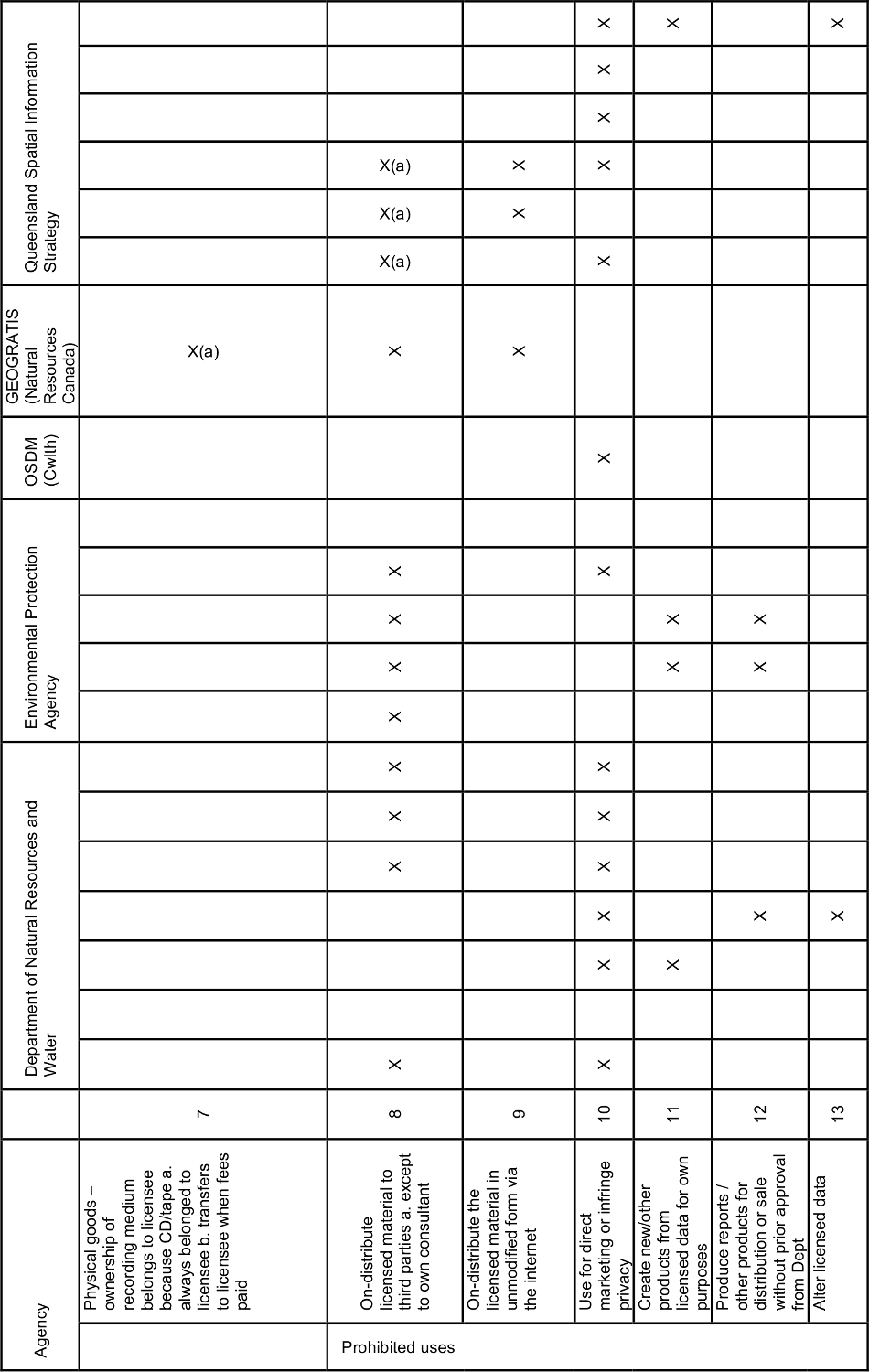

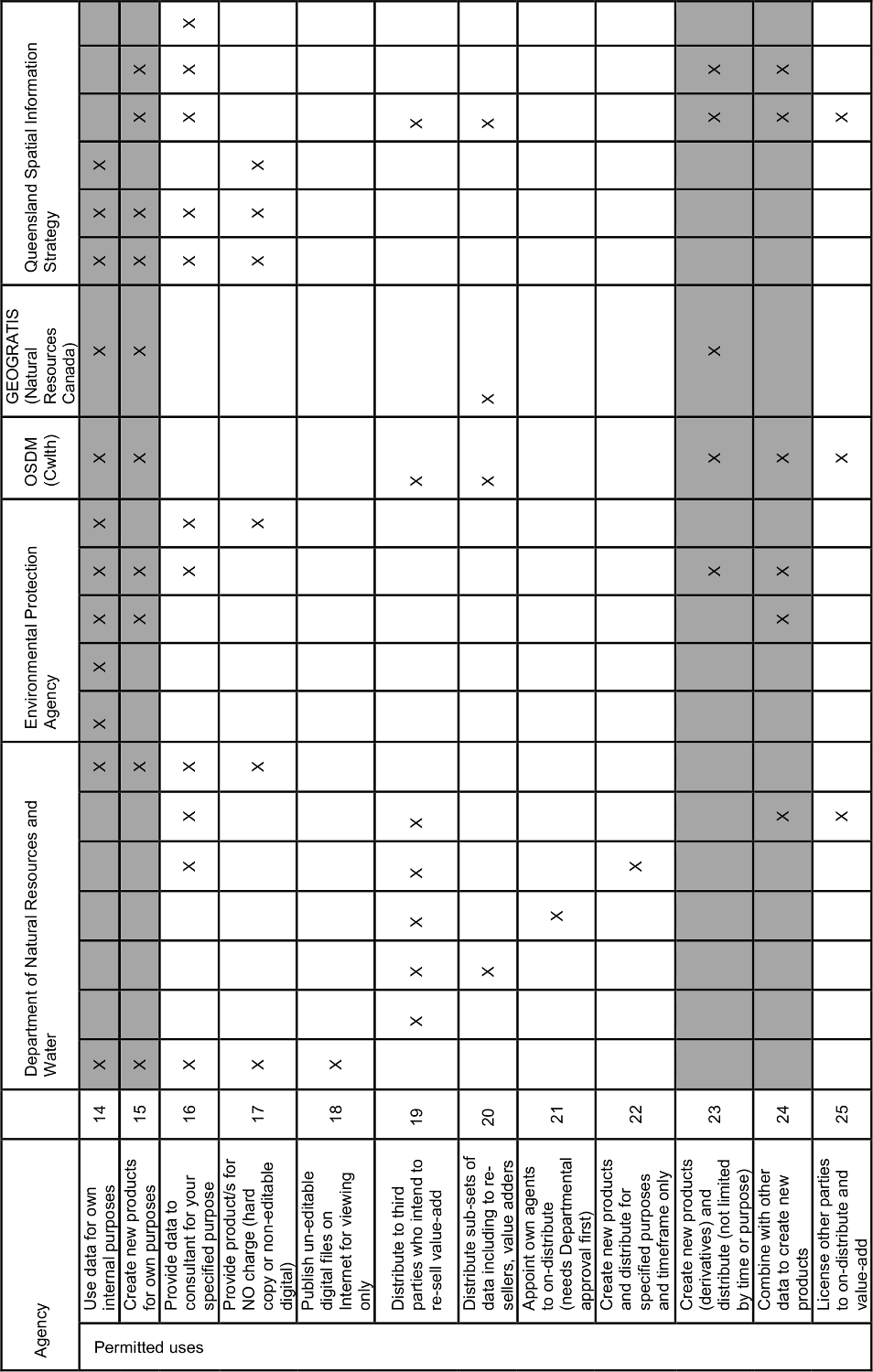

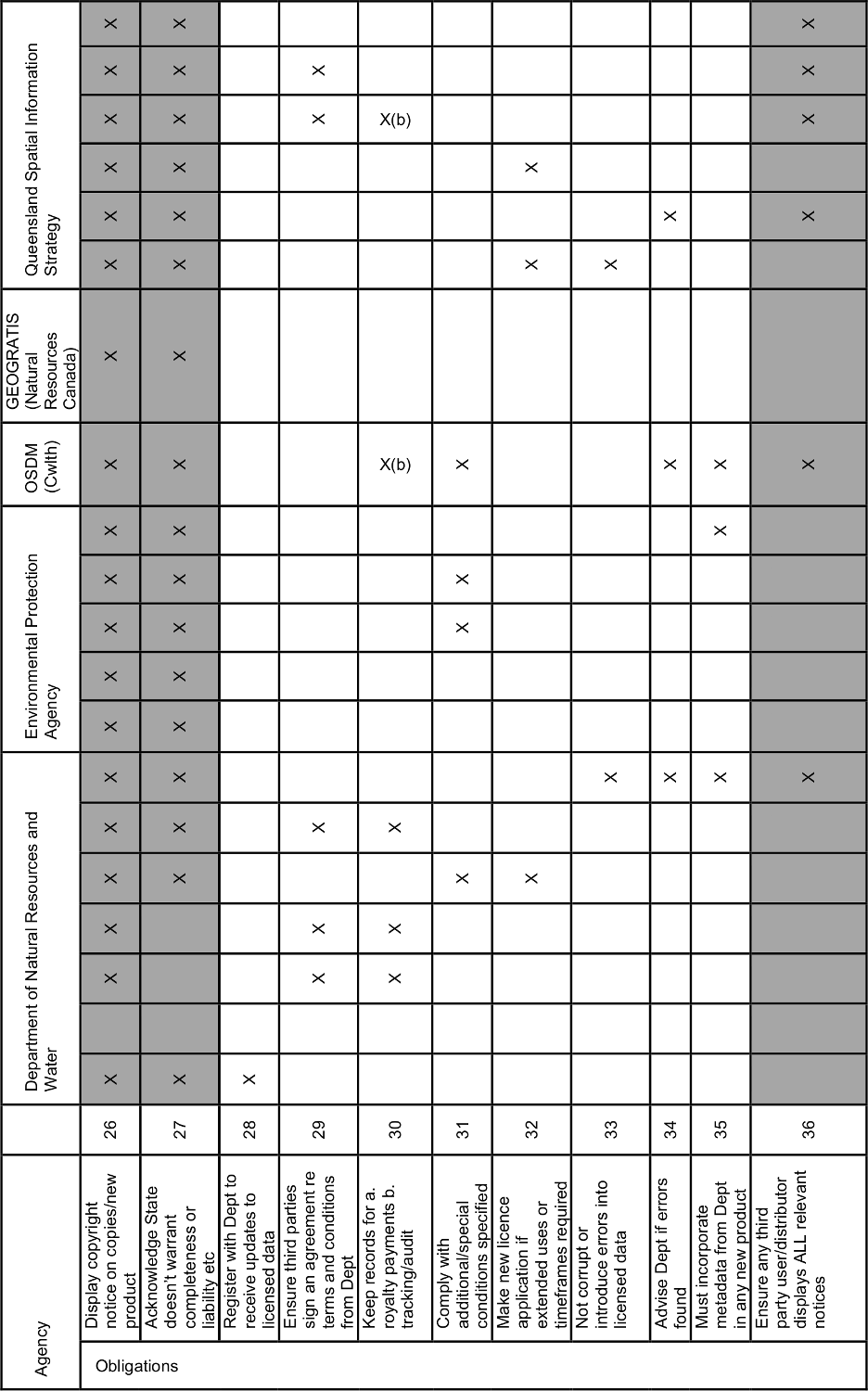

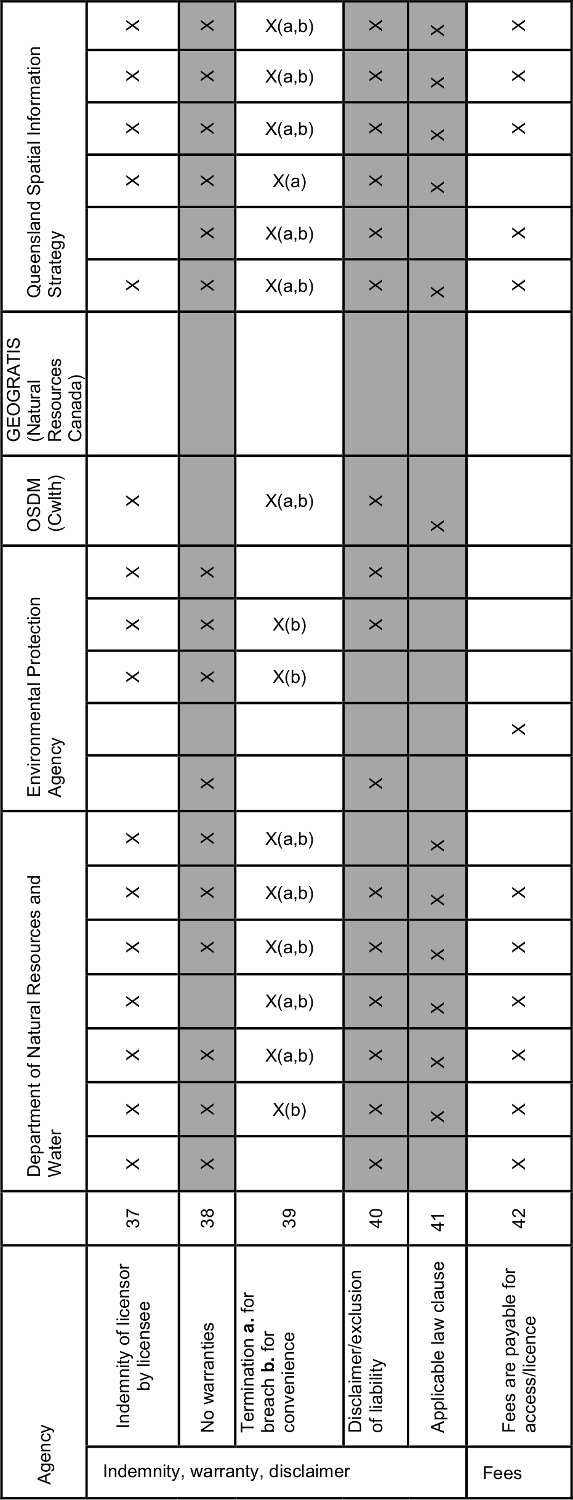

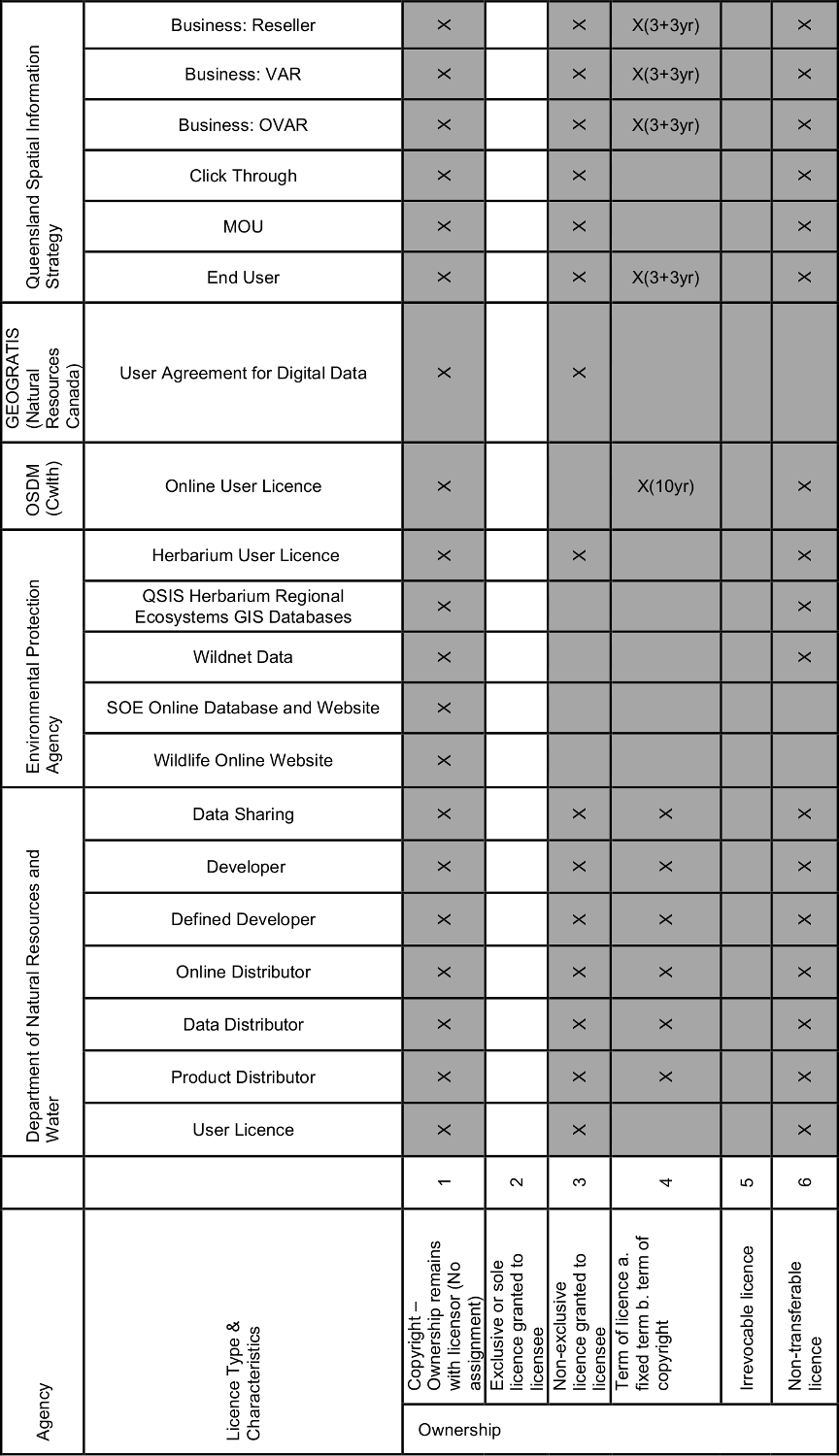

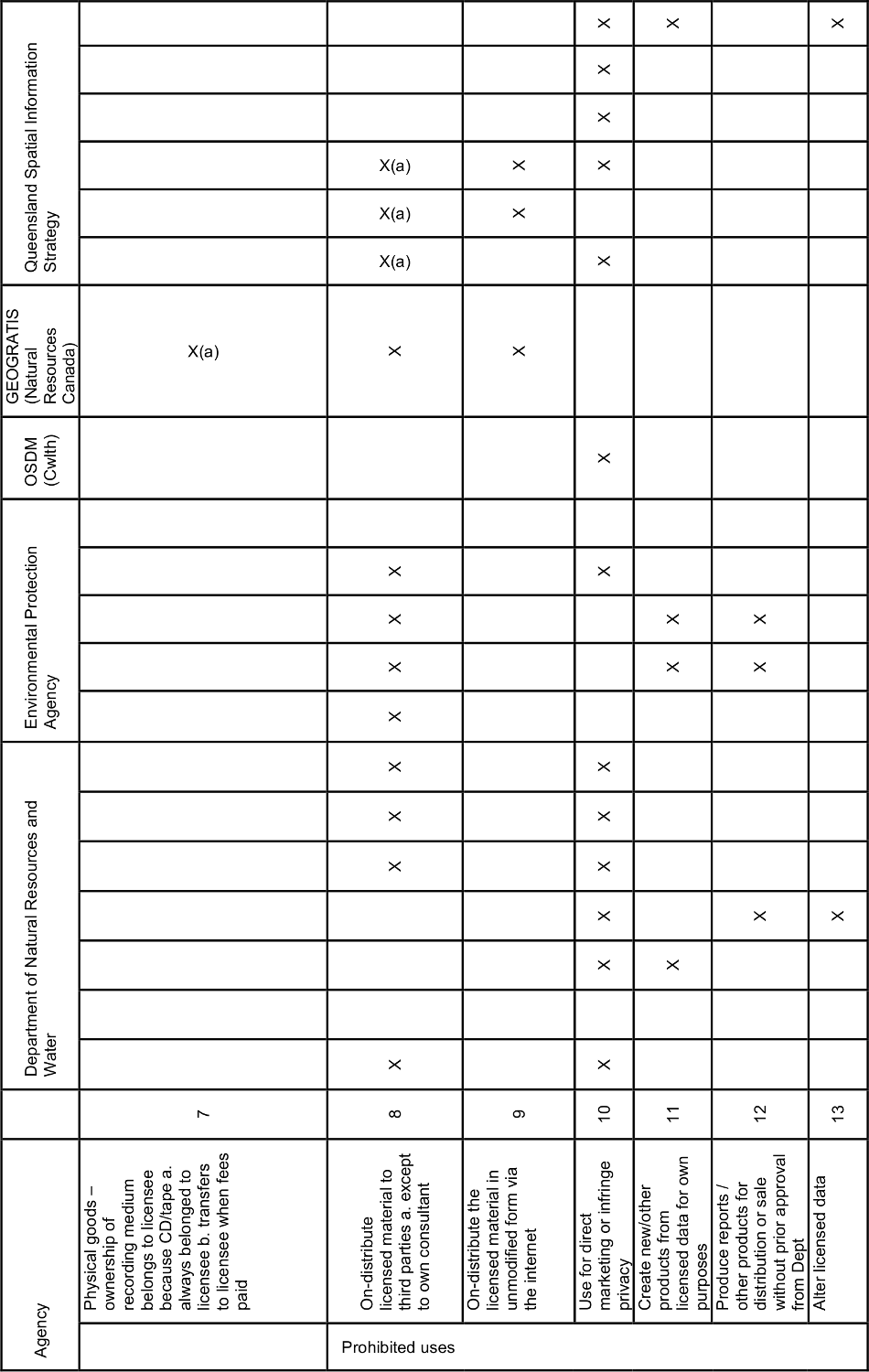

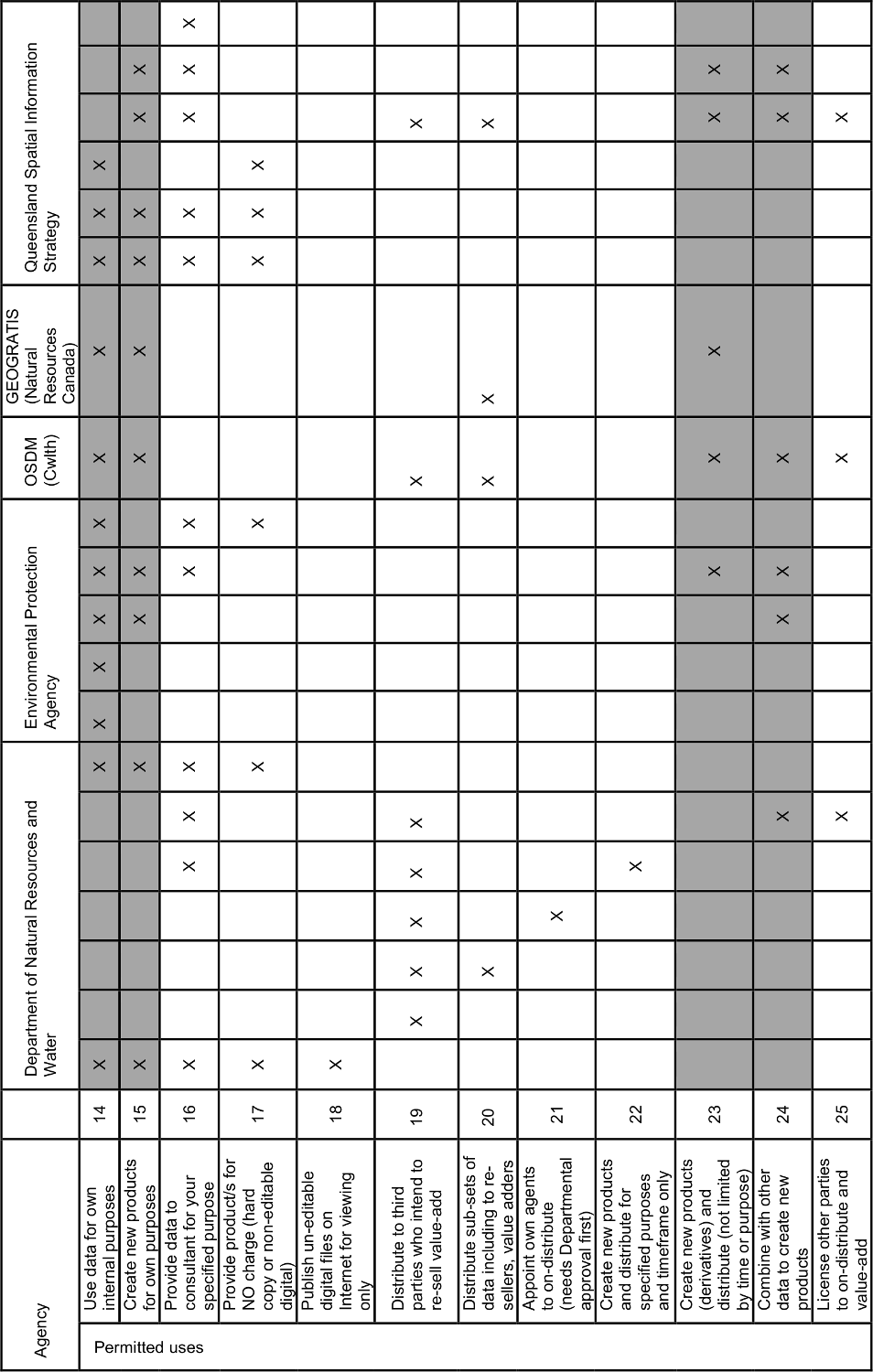

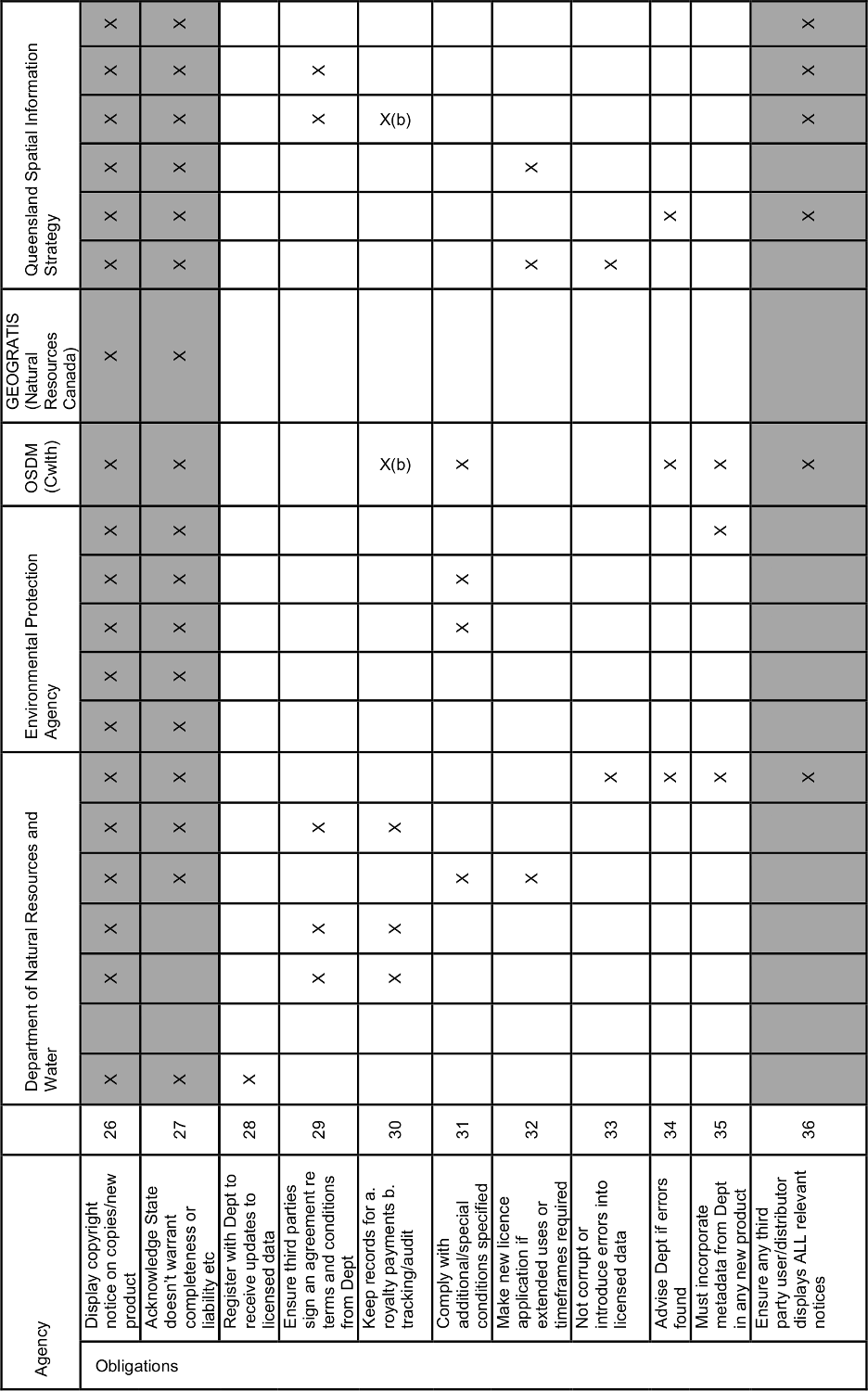

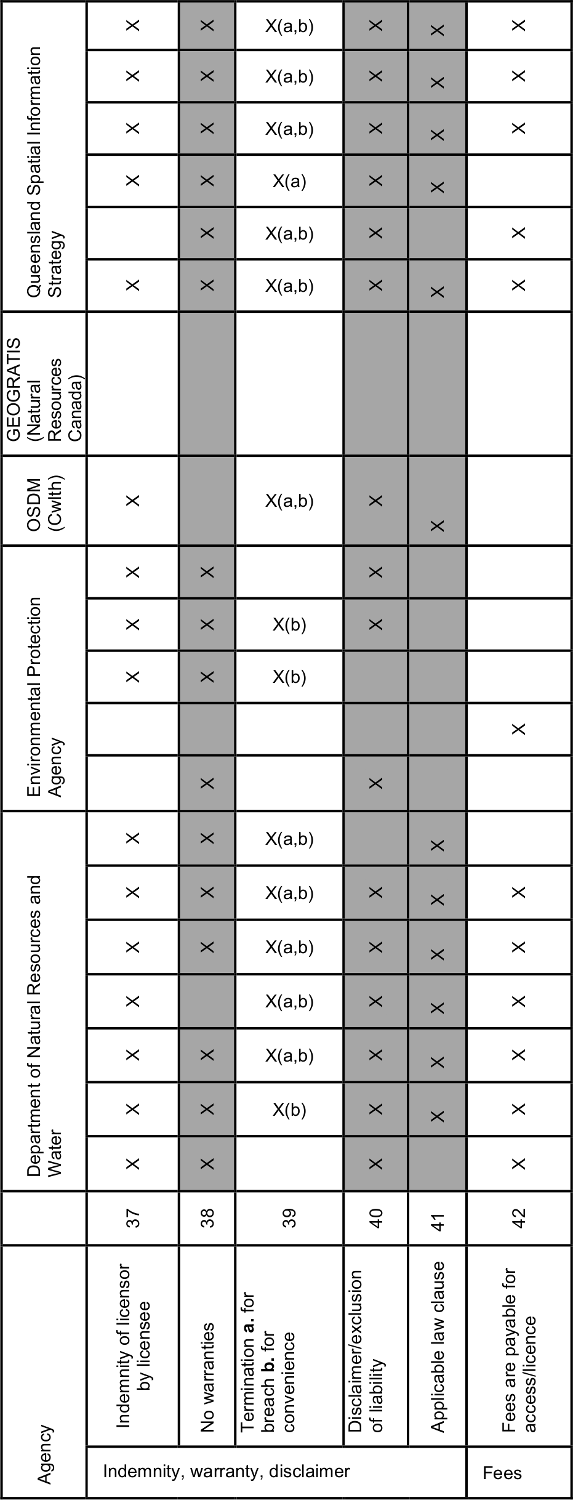

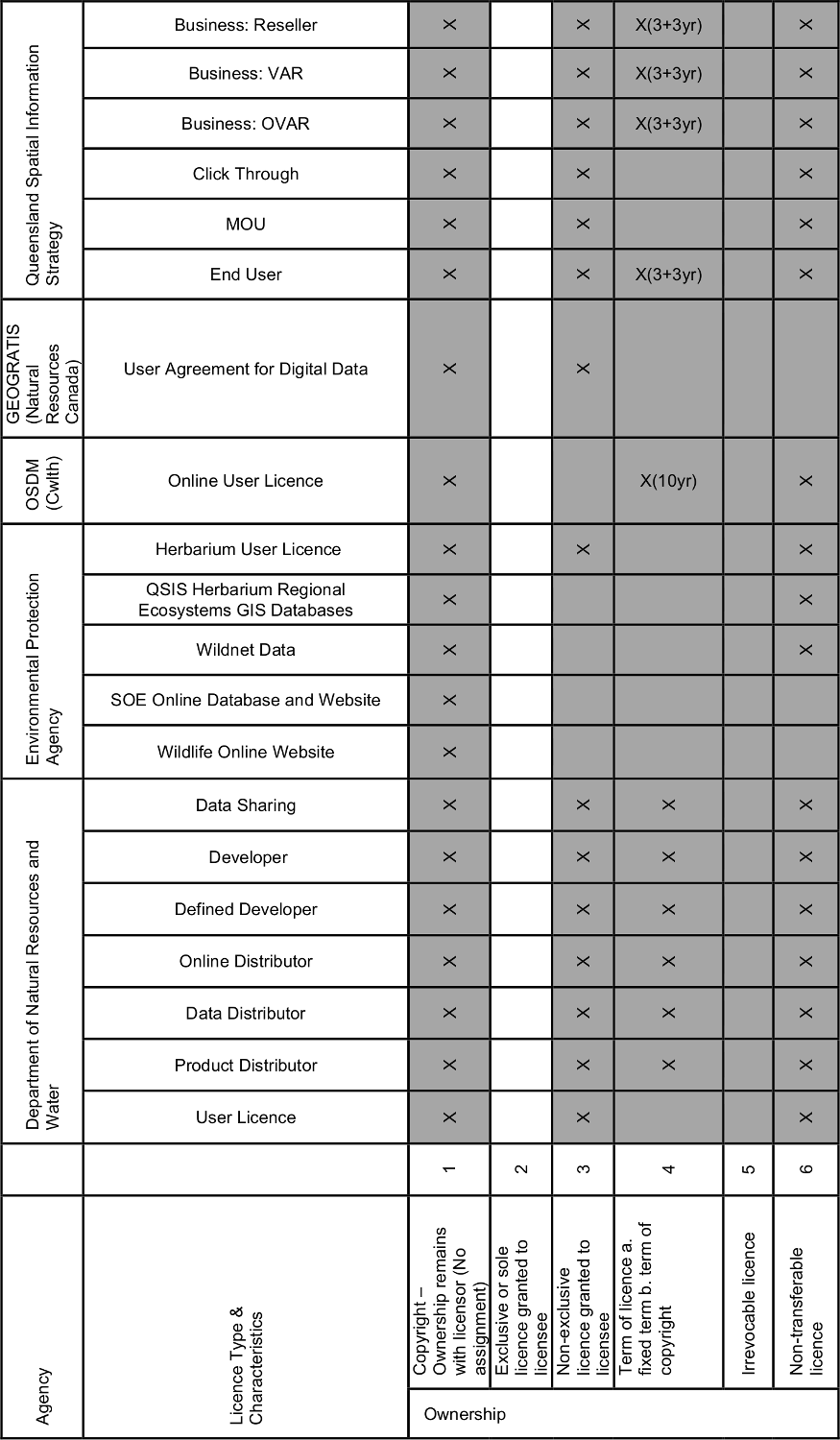

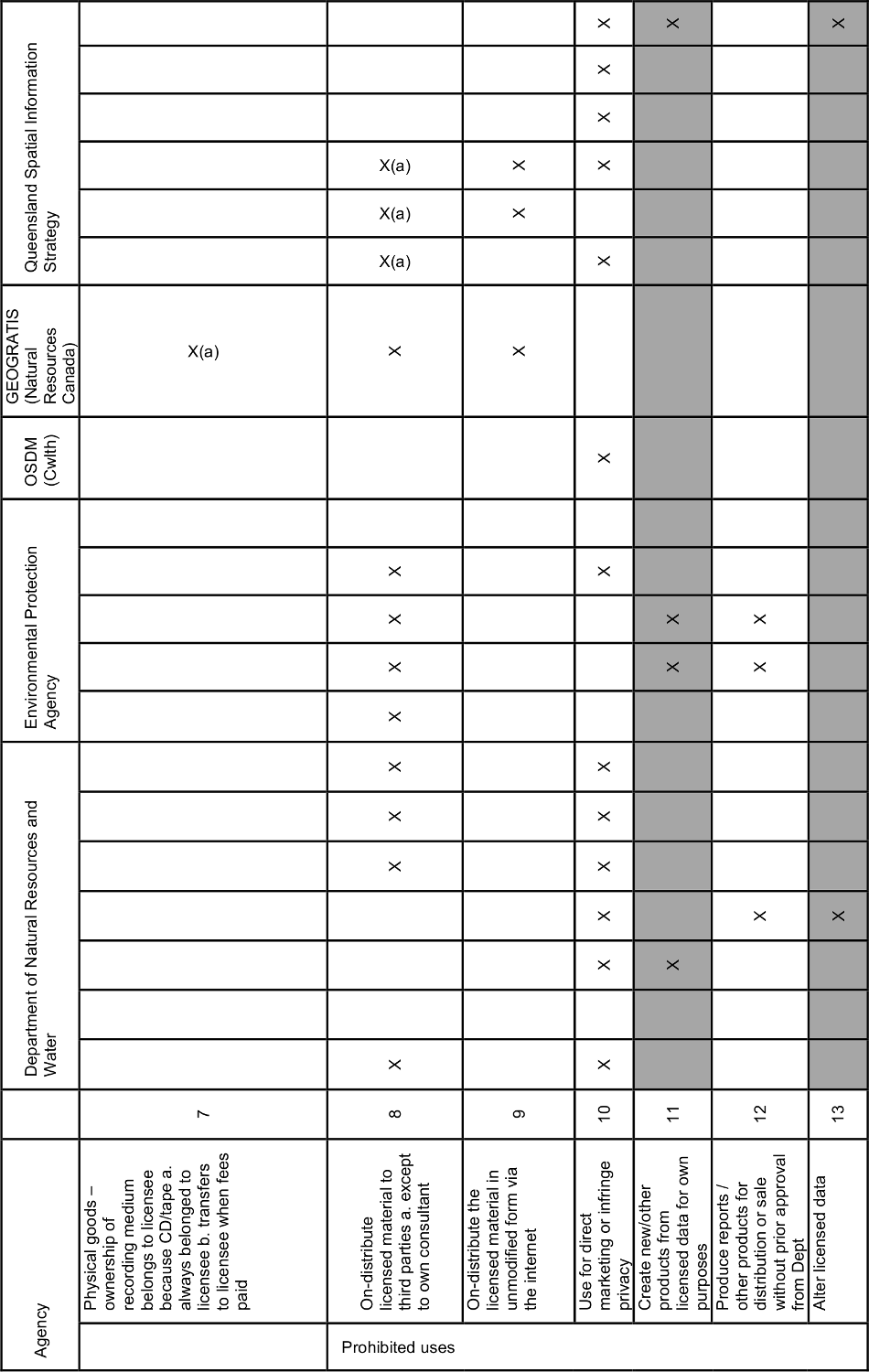

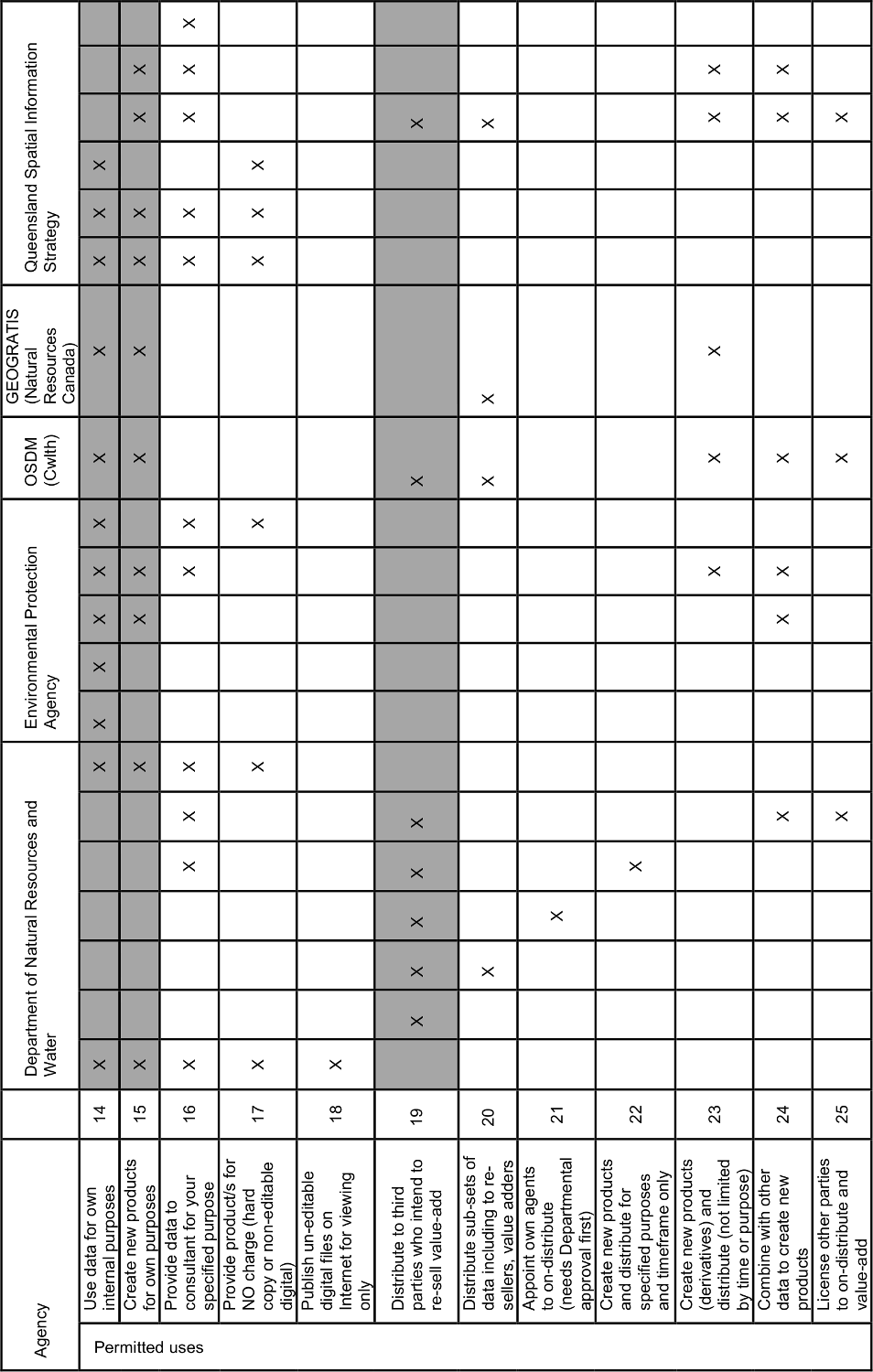

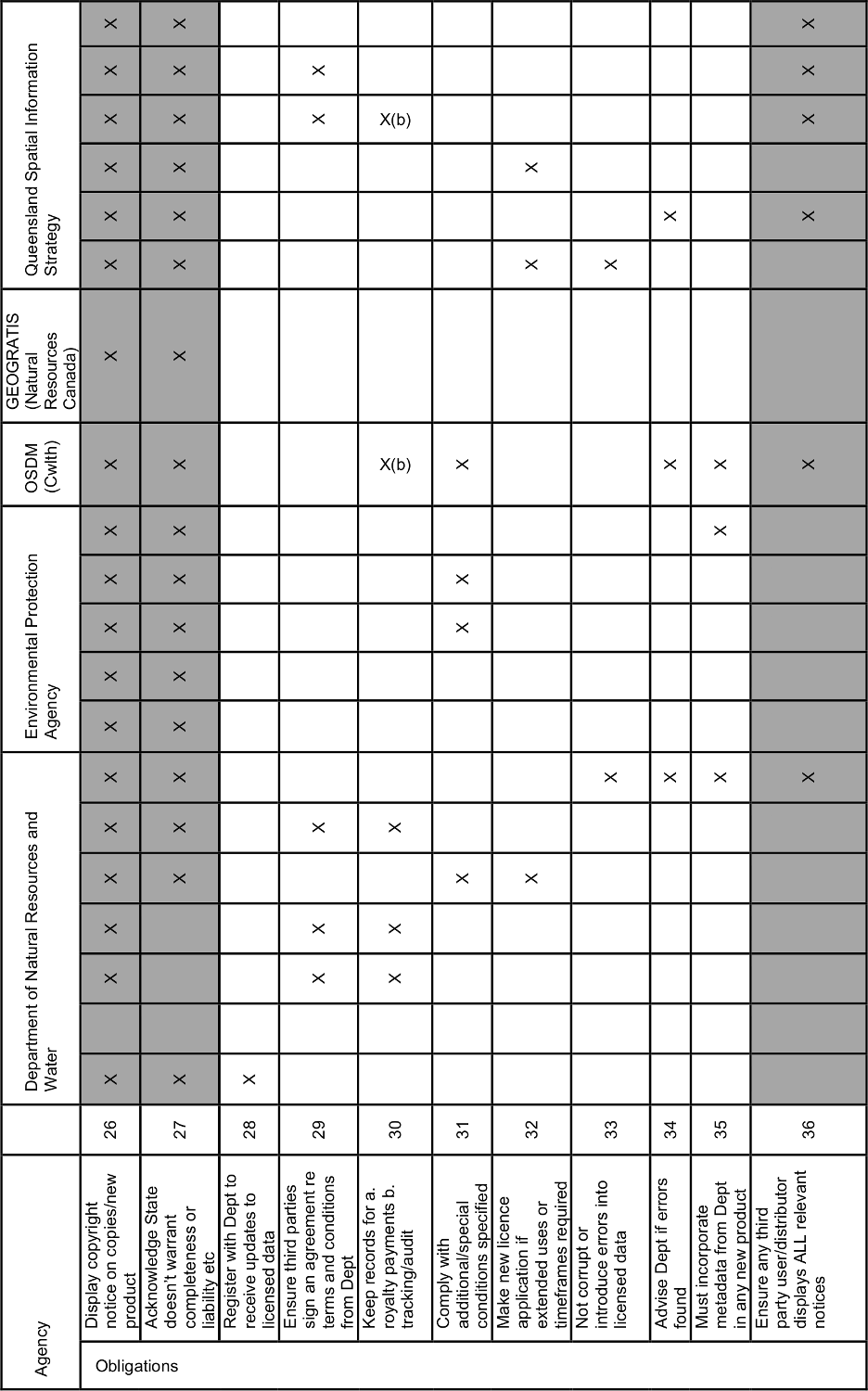

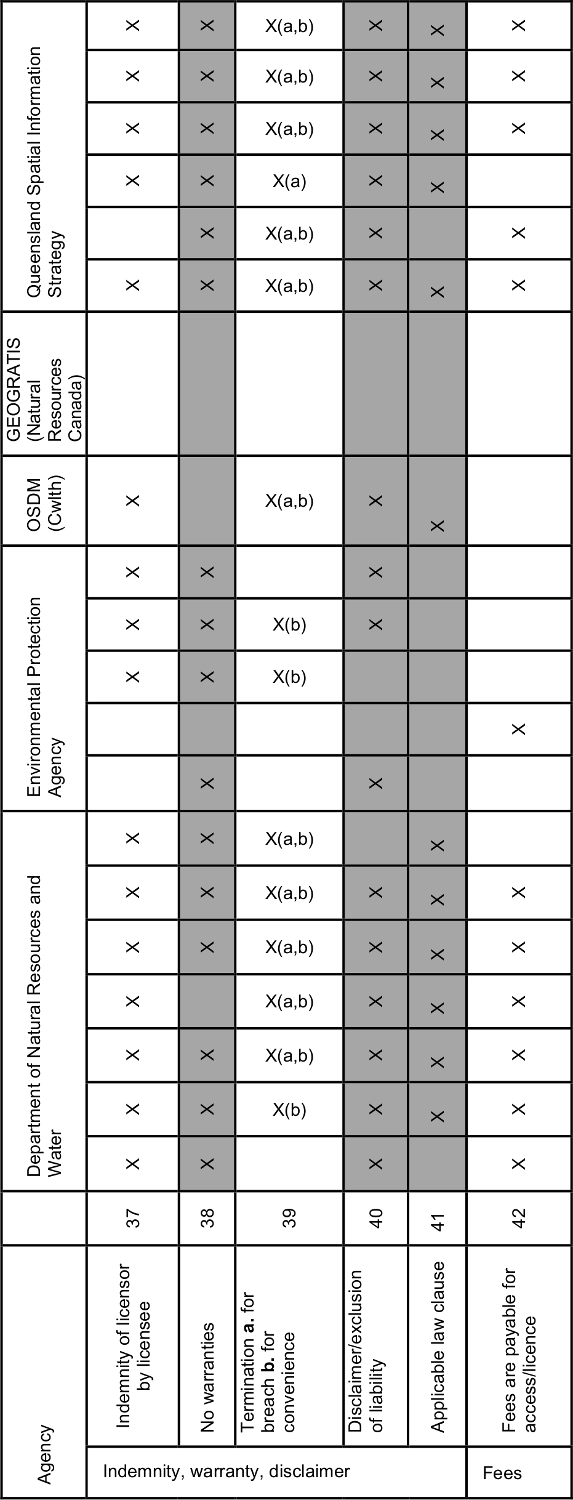

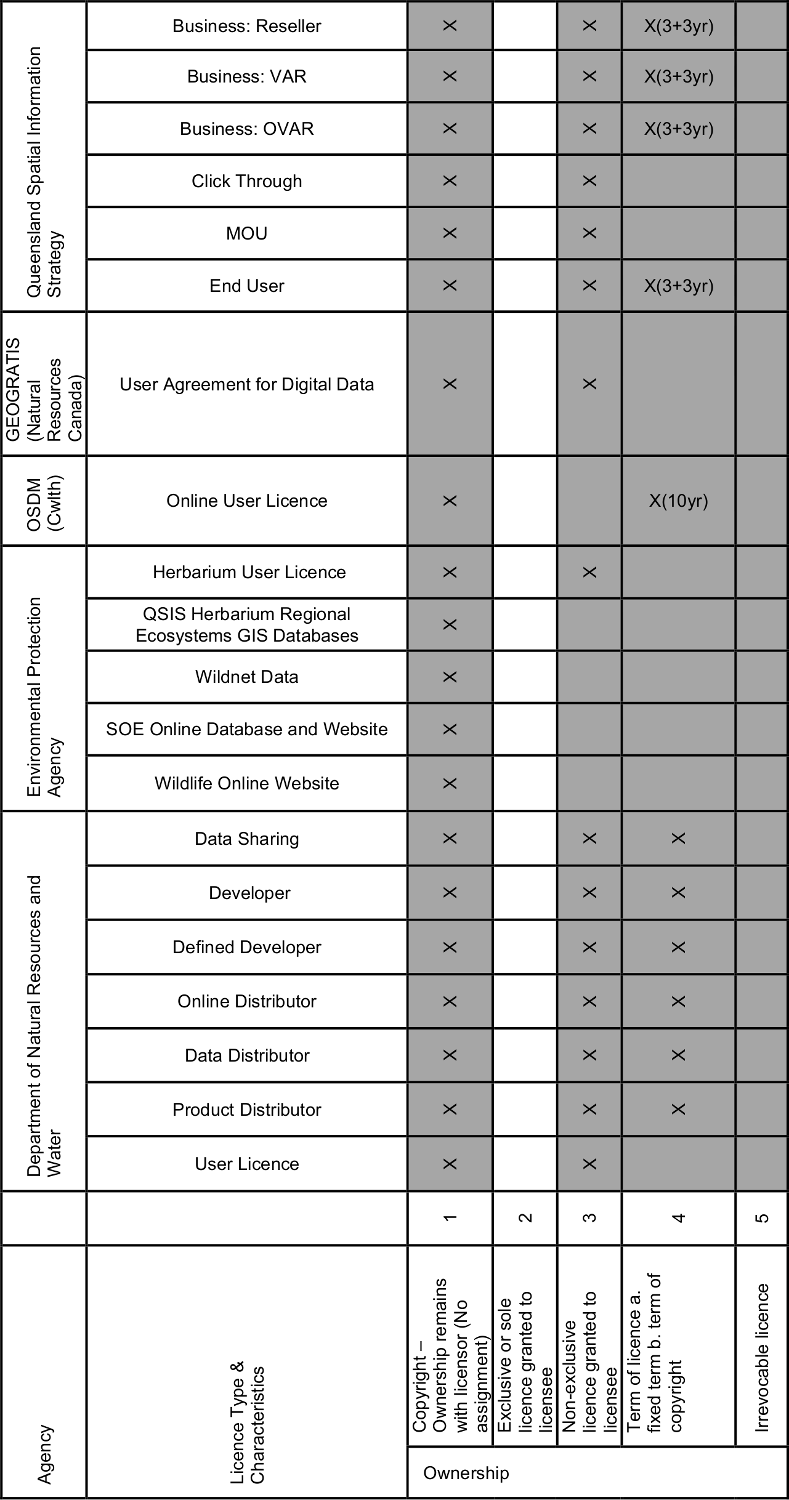

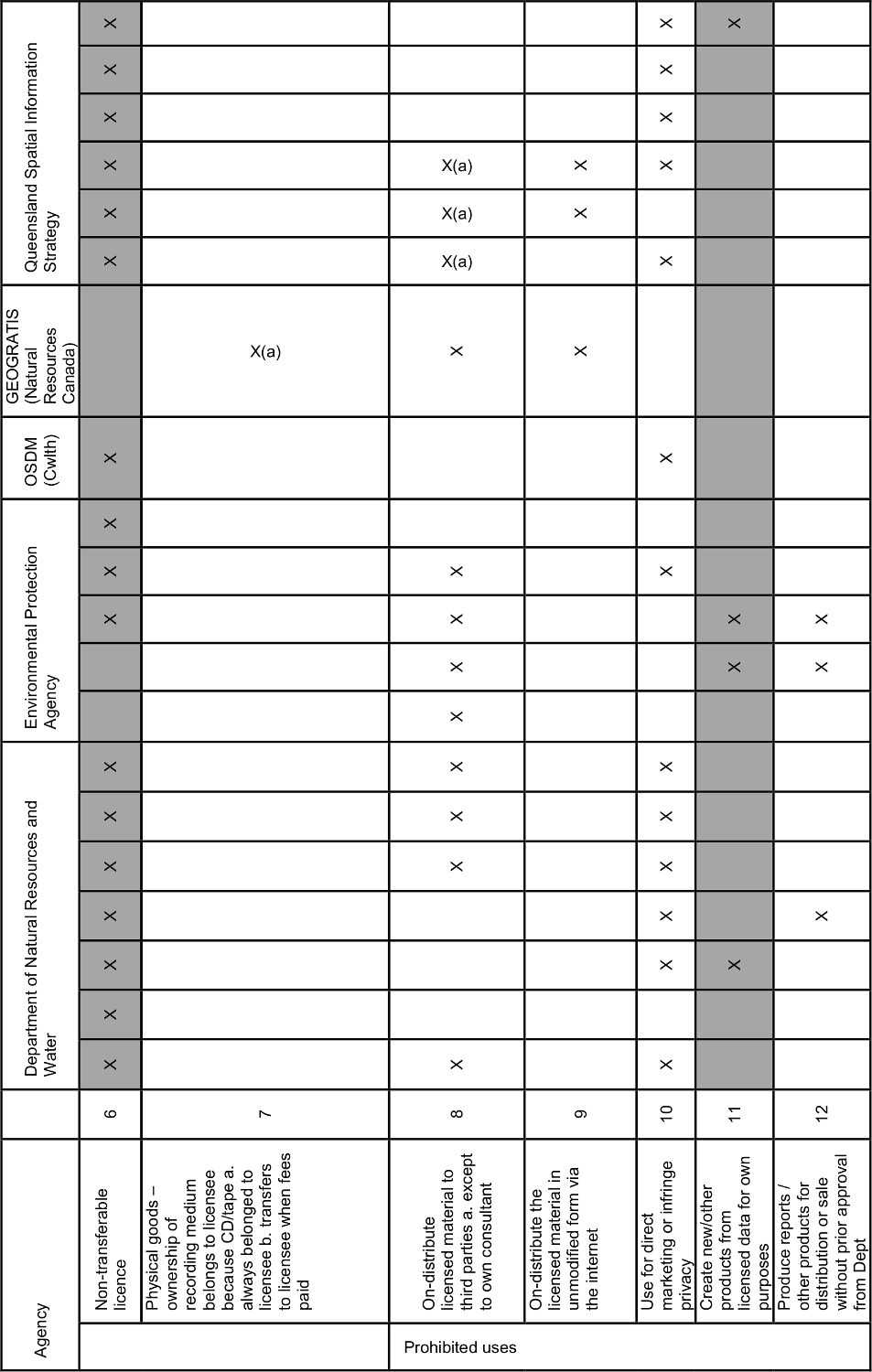

8.1 Time and resources available in Stage 2 did not permit a comprehensive assessment of every licence and agreement for information access or provision used by or imposed upon Queensland government agencies. Instead, a reference sample of licences was examined and analysed to establish the general characteristics of licences currently in use to develop an understanding of licensing policies and practices. Sample licences were identified by workshop attendees as being representative information transactions and licences. An analysis of the sample licences provided by those agencies which participated in the workshops identified common access and use rights, privileges and restrictions, as well as other terms and conditions.

8.2 Queensland Government licences and licensing arrangements were analysed to identify key characteristics, including ownership, permitted uses, prohibited uses, obligations and fees. The following lists the licences reviewed. (A more detailed analysis is provided in Attachment 4 – Analysis of Existing Licences. See also paragraph 8.6.)

QSIS licences:

- End User

- Memorandum of Understanding (MOU)

- Click Through (Online User)

- Business (OVAR, VAR, Reseller).

Department of Natural Resources and Water licences:

- User Licence

- Product Distributor

- Data Distributor

- Online Distributor

- Defined Developer

- Developer

- Data Sharing.

In addition, the Department of Natural Resources and Water uses memoranda of understanding and agreements.

It is clear from the consultation process that this department has developed and applies a fully developed and comprehensive suite of six or seven licences. It is generally accepted that the licences currently used by the Department of Natural Resources and Water have evolved from the QSIS licences, in response to the department’s business requirements and environment. A considerable amount of the agency’s data is available online. The department has developed a set of principles or guidelines to assist officers in identifying which of the licences is to be used in particular circumstances. 367

Information Queensland, Department of Natural Resources and Water – Spatialink/Infolink key data sets:

- Multiple agency use (e.g. State Digital Road Network)

- Share between agencies, add to and update (e.g. Cadastre from the Department of Natural Resources and Water)

- Public access (Licence type) (e.g. Integrated Planning Act planning schemes, the Department of Local Government, Planning, Sport and Recreation).

Information Queensland has adopted existing licensing arrangements established for the State Digital Road Network and the Cadastre. There are a significant numbers of data assets that still require relevant licences to be applied.

Environmental Protection Agency licences:

- Wildlife Online Website;

- State of the Environment (SOE) Online Database and Website

- Wildnet Data

- QSIS Herbarium Regional Ecosystems GIS Databases

- Herbarium User Licence.

The Environmental Protection Agency presently makes much of its data available online. It uses several kinds of fairly simple contract-based licences. The terms and conditions that apply generally to the Environmental Protection Agency’s websites, which are usually accessed via hypertext links at the bottom of web pages, needs to be reviewed for consistency with the terms and conditions of the standard licences used by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Queensland State Archives (QSA) licensing arrangements include:

- Memorandum of Understanding (for confidential surveys conducted by the Office of Economic and Statistical Research on behalf of QSA e.g. Technical reports, frequency tables, graphs)

- Licensing (distribution) arrangement with State Records NSW (for Keyword AAA Thesaurus to be distributed by QSA to Queensland public authorities)

- Licence agreement with public authorities in Queensland who use Keyword AAA

– agreement covers intellectual property, prohibited uses, services by third parties, documents, defects, changes to licence conditions and termination of the licence agreement

- Conditions of use (e.g. information for research or private study, and for no other purpose – copies of public records in QSA’s collection by members of the public and researchers)

- Conditions of entry (e.g. access to public records for users of QSA’s public search room – a readers ticket to access the records indicates that users have agreed to the conditions of entry to the public search room)

- Attribution/copyright (e.g. QSA’s Annual Report used by Parliament, Minister, MPs, public authorities, the public – QSA has no objection to the material in its annual report being reproduced but asserts its right to be recognised as author of its material and the right to have its material remain unaltered). 368

Office of Economic and Statistical Research:

- Memorandum of Understanding

- Agreement.

The Office of Economic and Statistical Research memorandum of understanding documents reflect a strong, traditional, contract-based approach. Emphasis is placed upon compliance with the Statistical Returns Act 1896 and applicable privacy Information Standards. The variables for particular projects are set out in the Schedule.

Licences from some other jurisdictions were also reviewed:

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS):

– CD 2001 Licence agreement

– ABS@Final

– ABS Conditions of Sale.

The ABS agreements reflect a strong, traditional, contract-based approach with only restricted rights being conferred on licensees. The need to respect privacy and confidentiality is emphasised.

- Office of Spatial Data Management (OSDM) Australian Government:

– Online User Licence

– Agency-specific Deed of Licence for spatial data provided over the internet.

The online user licence is royalty-free and grants broad rights to the licensee. Whilst reflecting certain CC licence attributes it also contains certain traditional contract-based licence features.

- Natural Resources Canada:

– GeoGratis User Agreement for Digital Data.18

The GeoGratis royalty-free licence permits the licensee to create and distribute online derivative information products, but prohibits on-distribution of the unaltered licensed data online. Recognition of copyright is required, together with an indemnity in favour of the licensor. This is a short licence written in plain English.

8.3 The findings from the analysis follow. Many of the licences, including those presently in use by the Department of Natural Resources and Water reflect a policy or philosophy focusing on the maintenance of control over the use of data downstream after it has been made available initially under the licence. These provisions are designed to maintain control over the use that may be made of the information through a chain or series of end-to-end interlocking contractual provisions. The legal measures used are essentially contract-based rather than copyright-based. The general approach is to endeavour to ensure, as far as practicable, that in each successive downstream transaction certain core or fundamental provisions are replicated. These provisions typically include: 369

- several forms of copyright notice and statement, depending on whether or not the licensee was entitled to create value-added or derivative products, to indicate copyright ownership (e.g. Crown copyright generally, or Crown copyright in the base data as initially licensed which then forms part of the derivative or value-added product)

- scope of use rights (e.g. right to sub-license, right to commercialise, right to create value-added/derivative products)

- an indemnity by the licensee in favour of the immediate licensor as well as the State of Queensland.

8.4 Similar observations to those set out above apply to the current suite of QSIS licences, which in significant part were the precursors to the current suite of licences used by the Department of Natural Resources and Water. The QSIS licences were prepared for use by both the public and private sectors about 10 years ago and do not focus specifically on the legal or operational issues arising in the online environment.

8.5 The following paragraphs deal with specific terms and conditions contained in the existing sample of licences.

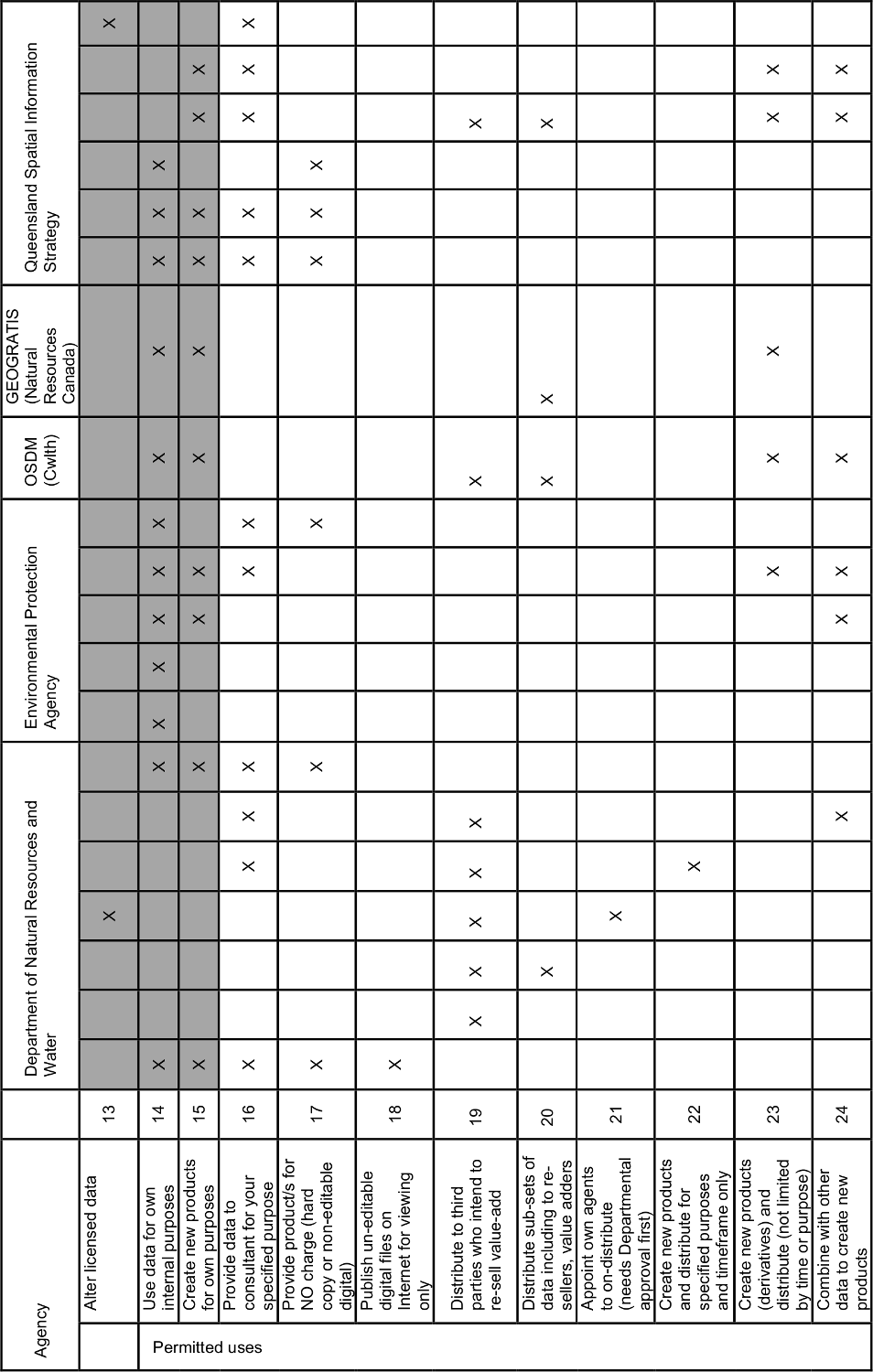

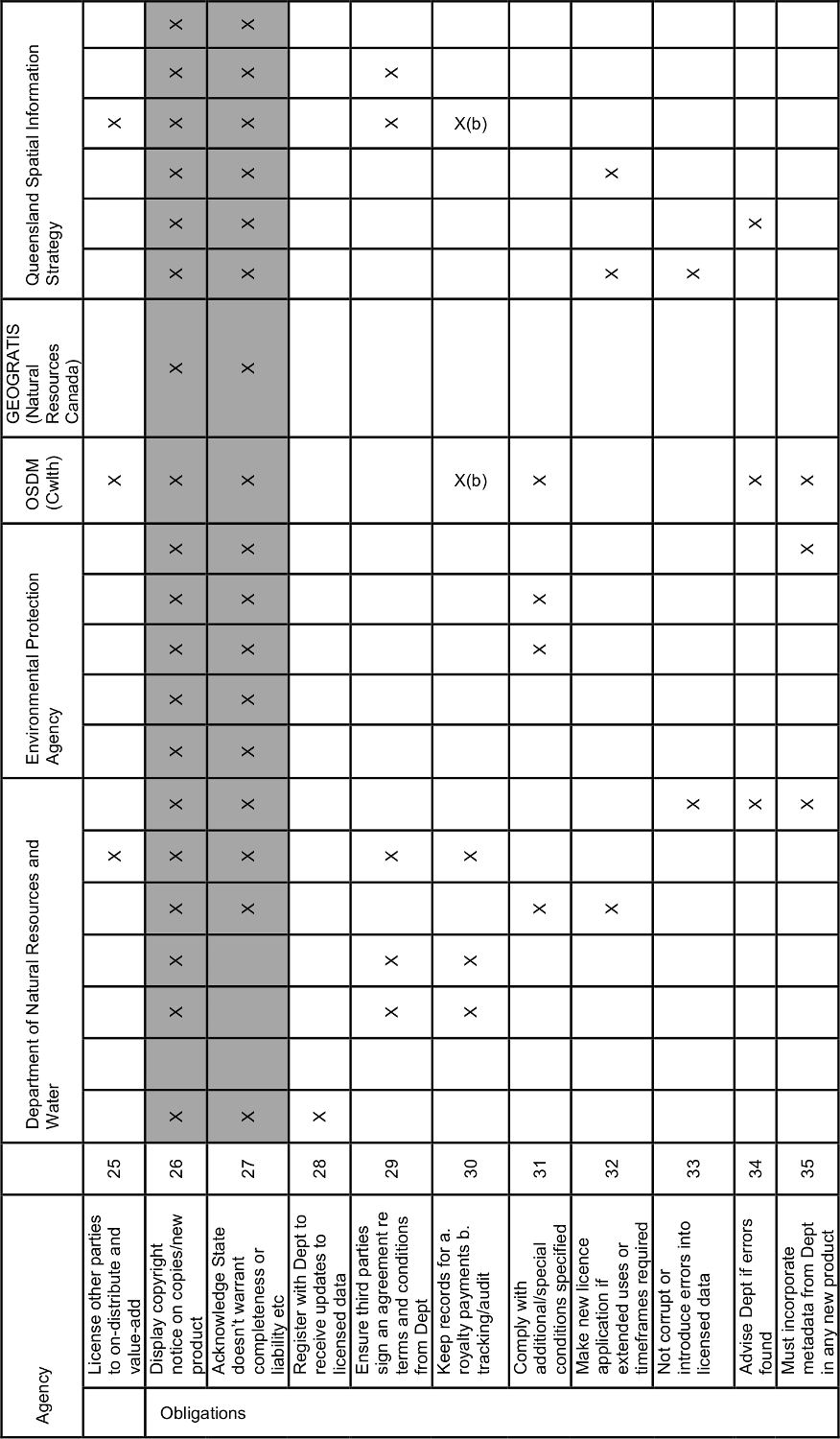

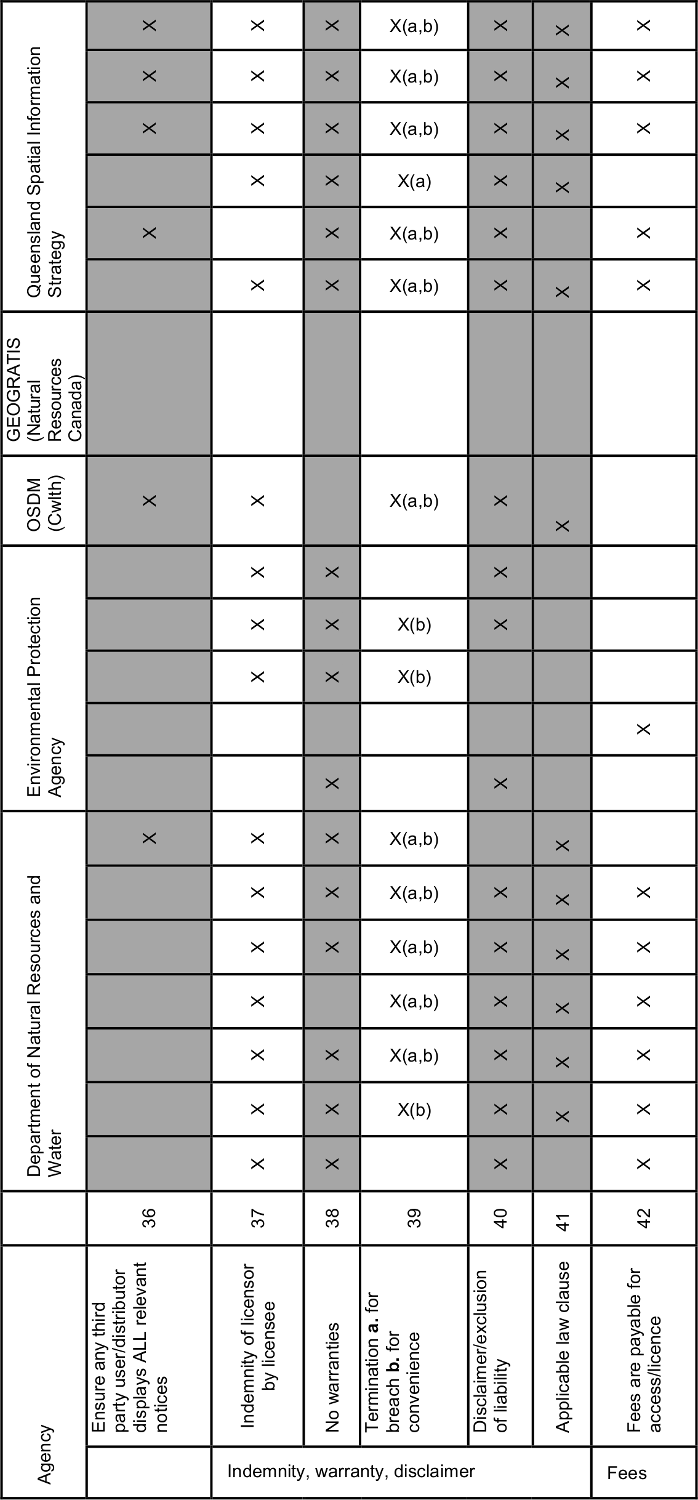

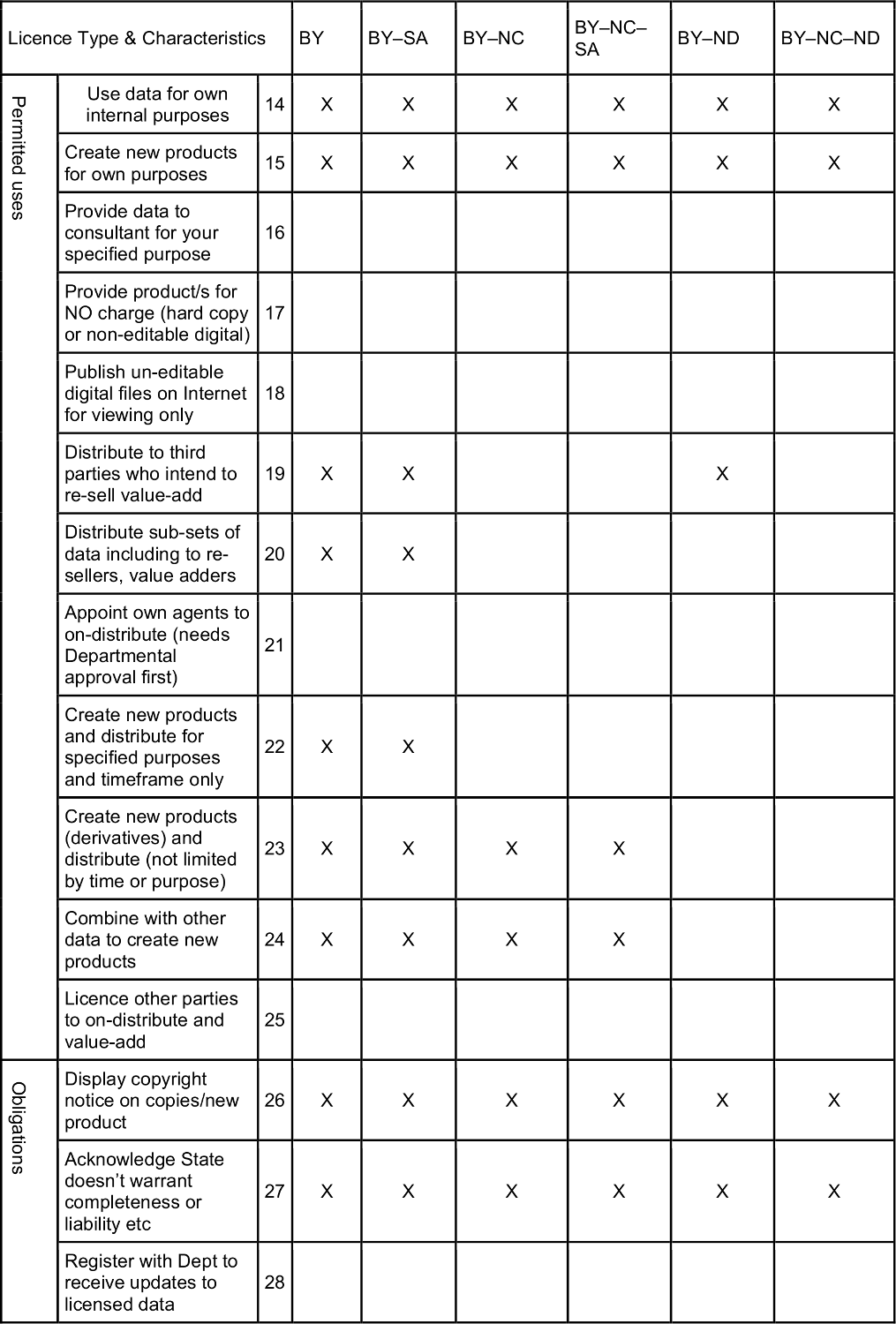

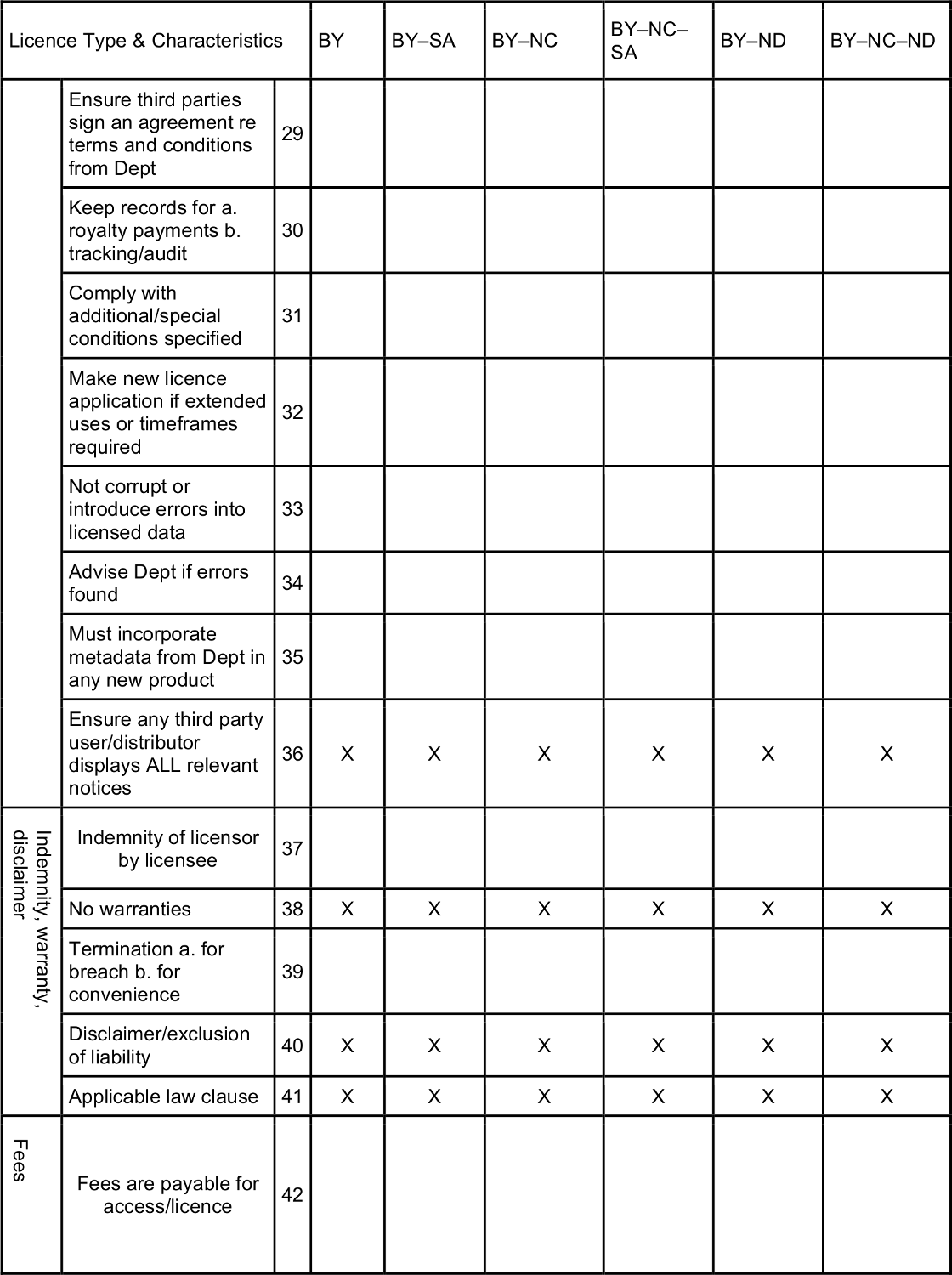

8.6 The existing 20 licences reviewed during Stage 2 were examined in relation to 42 concepts or terms, of which many map directly to 15 to 18 concepts or terms contained in the CC licences. The following tables are contained in Attachment 4 – Analysis of Existing Licences. They summarise in a general way the main characteristics of each of the 20 licences and the generally equivalent CC licence provision.

- TABLE 1: Analysis of Licences – Terms and conditions in existing licences

- TABLE 2: Broadly equivalent terms and conditions in the CC Attribution (BY) licence

- TABLE 3: Broadly equivalent terms and conditions in the CC Attribution Share Alike (BY–SA) licence

- TABLE 4: Broadly equivalent terms and conditions in the CC Attribution No Derivatives (BY–NC) licence

- TABLE 5: Broadly equivalent terms and conditions in the CC Attribution Non-commercial Share Alike (BY–NC–SA) licence

- TABLE 6: Broadly equivalent terms and conditions in the CC Attribution No Derivatives (BY–ND) licence

- TABLE 7: Broadly equivalent terms and conditions in the CC Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives (BY–NC–ND) licence

- TABLE 8: Broadly equivalent terms and conditions in six CC licences.

8.7 The following section discusses the terms and conditions that are contained in the 20 licences reviewed and which are not included in any of the CC licences. These terms have been reviewed to identify whether they are still REQUIRED, and if still required whether they can be met through new POLICY, LEGAL (either through contract or legislation), or ADMINISTRATIVE arrangements aimed at streamlining the licensing process and making greater use of public sector information.

| TERM or CONDITION (see Table 1, Attachment 4 – Analysis of Existing Licences) | COMMENT and RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

| 2. This term refers to ‘ownership’ and provides exclusive or sole licence to the licensee | This term has not been used in any of the licences reviewed and does not exist in the original QSIS licence terms. As it is not generally used, it is NOT REQUIRED. 370 |

| 7. This term refers to ownership and is used in the Geogratis (Natural Resources Canada) User Agreement for Digital Data. The Canadian licence uses it to state that a recording medium (CD/tape) belongs to the licensee if it always belonged to the licensee. | This is considered to have been drafted in the pre-web environment and when recording mediums were more costly. It is suggested that this term is now NOT REQUIRED if web medium is used. |

| 8. This term is used in 12 of the licences reviewed and prohibits a user from on-distributing material to third parties except own consultant. | This term ties in with term 10 and it would still be required for government licences for security reasons. These are outside the scope of the CC model and this term is REQUIRED – LEGAL (CONTRACT). |

| 9. This prohibits the users from on-distributing the licensed material in unmodified form via the internet. It appears in two QSIS licences and in the Geogratis licence (Canada). Some further clarification of the definitions for ‘derivative’ and ‘derivative only licence’ will be required. | It is considered that this term is NOT REQUIRED if a new POLICY PRINCIPLE on access and use is adopted. |

| 10. This term is in 13 of the 20 licences reviewed and prohibits the use of the data or product for direct marketing or if it infringes privacy. | This term reflects the government’s privacy principles. This term is REQUIRED – LEGAL (LEGISLATION), POLICY and ADMINISTRATIVE ARRANGEMENTS. |

| 12. This term appears in three licences – Natural Resources and Water Distributor, Environmental Protection Agency SOE Online Database and Website and Wildnet Data – and prohibits the user from producing reports or other products for distribution or sale without prior approval from the Department. | It is recommended that this term is for transactions outside the scope for the CC model and it is REQUIRED – LEGAL (CONTRACT). |

| 16. This term defines a permitted use – to provide data to a consultant for a specified purpose – and is included in 11 of the licences reviewed. | Terms that apply to licensees must also apply to ‘agents’ such as consultants or contractors, and these ‘agents’ when working with confidential information are required to enter into a legal contract which includes a confidentiality provision. This term would still be required for transactions that are highly commercial or confidential and therefore outside the scope of the CC model. For these arrangements a policy principle and legal contract, including a confidentiality term are required. REQUIRED – LEGAL ARRANGEMENT (CONTRACT). |

| 17. This term permits users to ‘provide products for no charge’ (hard copy or non-editable digital). This appears in six of the reviewed licences – QSIS End User, MOU, Click Through, Natural Resources and Water User and Data Sharing licences, and the Environmental Protection Agency Herbarium User licence. | There may be specific instances where agencies require this term, however if there is a change in charging and access policy, then it may not be required. NOT REQUIRED – POLICY. 371 |

| 18. This term permits users to publish un-editable digital files on the internet for viewing only and appears in the Natural Resources and Water User Licence. | This term is no longer required as it can be covered using a CC licence – BY-NC-ND or BY-ND and it is NOT REQUIRED if there is a new POLICY PRINCIPLE that supports more open access and use. |

| 21. This term is used by Natural Resources and Water in its Online Distributor licence to appoint their own agents to on-distribute (requires Natural Resources and Water approval). | This term is not applicable to CC transactions and it is REQUIRED – LEGAL CONTRACT. |

| 25. This term permits users to license other parties to on-distribute and value-add and appears in the QSIS Business: OVAR licence, the Natural Resources and Water Defined Developer licence and the OSDM (Federal Government) Online User licence. | This term is addressed by the CC licences (BY-SA) and it is NOT REQUIRED if a new POLICY PRINCIPLE to encourage wider use of copyright materials based on the CC model is adopted. |

| 28. This term is used in the Natural Resources and Water User licence and obliges the user to register with the Department to receive updates on licensed data. | This term is NOT REQUIRED if an ADMINSTRATIVE ARRANGEMENT such as information on packaging is used. |

| 29. This term is used in two QSIS licences and three Natural Resources and Water licences – and obliges third parties to sign an agreement re the licence terms. | This term ties in with term 10 above. It is REQUIRED – LEGAL (CONTRACT). |

| 30. This term is used in two QSIS Business licences and in three Natural Resources and Water licences – Data Distributor, Online Distributor and Developer –and obliges the user to keep records for royalty payments and for tracking on audits. | This term could be met through a POLICY PRINCIPLE and ADMINISTRATIVE ARRANGEMENT and it is NOT REQUIRED. |

| 31. This term is used in four licences – the Natural Resources and Water Defined Developer, the Environmental Protection Agency Wildnet Data and QSIS Herbarium Regional Ecosystems GIS Databases and the OSDM Commonwealth Online User Licence. It obliges users to comply with additional/special conditions. | This term is used by the Department of Natural Resources and Water for transactions that would be outside the scope of the CC model and it is REQUIRED – LEGAL (CONTRACT). |

| 32. This term is in the QSIS End User and Click Through licences and in the Environmental Protection Agency Defined Developer licence and obliges users to make a new licence application if extended uses or timeframes are required. | Under the CC model, the duration of licences is unlimited and if there is a POLICY PRINCIPLE based on the CC philosophy of making data available for use and re-use indefinitely then it is NOT REQUIRED. |

| 33. This term is in the QSIS End User and the Natural Resources and Water Data Sharing licence and obliges the user not to corrupt or introduce errors into received data. | As this is already covered by a general law concept of ‘acting in good faith’, which could be reinforced by a POLICY PRINCIPLE, it is NOT REQUIRED. However, if the ‘indemnity’ term is not available, then this term may still be REQUIRED. 372 |

| 34. This term requires users to report if errors are found (Natural Resources and Water Data Sharing, OSDM Commonwealth Online User Licence and QSIS MOU). | As above with 33, this is covered by a general law concept of ‘acting in good faith’, which could be reinforced by a POLICY PRINCIPLE. This condition is NOT REQUIRED. |

| 35. This term is in three licences and requires users to incorporate metadata from the Department in any new product. | This condition is central to good data management and it is required to reinforce the POLICY PRINCIPLES established in Information Standard No 34 – Metadata (IS34), and IS44. REQUIRED – POLICY and ADMINISTRATIVE ARRANGEMENTS (TECHNICAL SOLUTION). |

| 37. This term appears in 16 licences and ensures indemnity of the licensor by the licensee. | This needs to be limited to situations where there is a high risk and it is NOT REQUIRED if there is a POLICY PRINCIPLE related to legal liability and if a risk analysis is undertaken by the agency. |

| 39. This term is in 15 licences and provides for termination due to breach or convenience. | It is not possible to terminate a CC licence for convenience only. However a CC licence terminates automatically on breach by the licensee. The convenience provision is NOT REQUIRED for transactions within the scope of the CC model. In the case of a breach the State could sue a licensee for damages. For transactions outside the CC scope, it would be REQUIRED. |

| 42. This term is in 12 licences and refers to fees that are payable for access on the licence. | This term supports commercial transactions and it is considered outside the scope of the CC model and it is REQUIRED – POLICY and LEGAL (CONTRACT) for these cases. |

8.8 Generally, the terms that continue to be required reflect transactions:

- that are highly commercial

- relating to confidential information or the use of private information (e.g. direct marketing etc)

- where time limits apply

- where the ability to terminate a licence is required or where the licence is revocable

- where an indemnity is required.

8.9 From this review of existing terms and conditions the legal requirements set out below, which are not provided for under the CC licences, would continue to be applicable and therefore should be addressed in any replacement template licences to be implemented within the Queensland Government. These are arrangements where a licensor needs to:

- limit authorised users – for example, to:

– provide data to a consultant for a specified purpose

– prohibit users from on-distributing material to third parties except own consultant

– appoint their own agents to on-distribute 373

– oblige third parties to sign an agreement re the licence terms.

- establish pricing and charging – for example to:

– refer to fees that are payable for access.

- ensure good data management – for example to:

– incorporate metadata from the custodian in any new product.

9. ISSUES ASSOCIATED WITH MOVING TO CREATIVE COMMONS LICENCES

9.1 The project team considered the issues and additional template licences or licence provisions that would be needed to bridge or close the gap between existing licensing arrangements and the CC licences.

9.2 A considerable number of Queensland Government agencies would, by adopting certain of the present CC licences, be able to meet all their business or operational requirements. The majority of Queensland Government databases could be made available under the simplest of the CC licences, namely the Attribution (or BY) licence, where there are no issues of privacy, confidentiality, statutory constraints or policy constraints. Using this licence, agencies could make such datasets readily available online:

- as free data or where a statutory charge or fee is payable

- without imposing any substantive requirements or limits on the initial recipient (licensee) or later recipients

- if the State’s ownership of copyright is recognised at all times during any use by the original or subsequent recipients (licensees).

Licensees can receive data either on CD or DVD or as a download online.

The present CC Attribution (BY) licence is suitable without any amendment for the majority of public sector information.

9.3 The present proposal, being conceptually founded on open content licensing, does not involve going beyond the rights inherent in copyright ownership. In particular, it does not seek to impose further restrictions or constraints on the recipients of licensed data. It is for this reason that the present proposal recommends a preliminary qualifying process be conducted for each dataset, to exclude data which can only be distributed if further constraints or obligations are imposed on recipients. In cases where it is considered necessary to impose further constraints or obligations on recipients of information, it will be necessary to consider whether such restrictions are to be imposed by contractual provisions, by administrative means, or by technological measures (e.g. by passwords or encryption).

9.4 There will be instances where data and information products will not qualify for the application of CC licences and where additions to and modifications of the CC licences are required. Therefore a limited number of standard templates will need to be developed for agencies to support information licensing transactions relating to confidential or private information or information with commercial value and for which the CC model is not appropriate. High value commercial transactions are outside the scope of the CC philosophy and licence structure. Agencies which conduct these transactions would still require negotiations and individual licence arrangements such as a memorandum of understanding or Specific Conditions of Use. Nevertheless any customised licences which need to be created to meet an 374agency’s business requirements in a particular case should be based as far as practicable on CC baseline rights, to foster consistency as much as possible across the public sector.

9.5 In general terms it is apparent that some of the major issues of relevance for agencies are whether the licensee of public sector data has the right to make commercial use of the licensed data and whether the licensee has the right to use the licensed data to create derivative products. The present suite of CC licences directly addresses these issues in a legally effective manner for the majority of situations or information transactions engaged in by agencies.

9.6 Non-endorsement provision: As a matter of caution, it would be desirable if a ‘non-endorsement provision’ such as that currently in use in the BBC’s Creative Archive Licence were added to the standard CC licence. The provision would be to the effect that the Licensee must not use the licensed data in any way that would suggest or imply the Licensor’s support, association or approval. It is understood that such a clause will be included in the next version of the CC licences. This provision could be ‘added to’ the present standard CC Attribution licence by means of a statement on the agency’s website, in combination preferably with a field in the metadata, styled ‘additional legal provisions’ so that this condition remained embedded in the data throughout its various uses online.

9.7 Meaning of ‘commercial/non-commercial’ in CC licences: CC is presently clarifying the meaning of ‘non-commercial’ as it is applied to three of its licences. As it stands, ‘non-commercial’ means that use of the licensed data is not primarily for financial gain, although some incidental commercial activity is permissible provided this activity is secondary or incidental to the primary non-commercial purpose. Nevertheless an agency would be able to collect a statutory charge or impose a licence fee under the Attribution (BY) licence, as well as under any of the three CC licences with the ‘non-commercial’ feature, as the non-commercial restraint on use applies only to the licensee’s use of the data (and not use by the licensor/agency).

9.8 As the CC licensing model does not deal comprehensively with ‘commercial’ access to and re-use of material – for example, where government agencies are required by government policy to recover the cost of information services through fee-for-service charges – additional licence terms would be needed. In some cases, data custodians may apply different conditions to commercial access and use of their data and services as opposed to non-commercial (not-for-profit) applications.

9.9 Whilst the CC model was designed from its inception to be used in the online environment of the internet, it also operates effectively and efficiently in the hardcopy (analog) environment and in the digital but non-online environment (e.g. where an agency provides data in digital format on say a CD or DVD as opposed to online via a website). Here a hard copy CC licence would be signed by the licensor and licensee.

9.10 As a result of considering the array of non-uniform licences presently in use across the public sector and the consultation conducted as part of this project, it is considered that a move to open content licensing, specifically CC licences, would result in the benefits set out below being secured.

From the perspective of the agency or Department there would be:

- consistency and transparent treatment of digital resources

- improved perception of ‘value for money’ by the general public

- reduction in effort of dealing with enquiries for information/resources

- reduction in effort of developing a re-use policy by sharing a common policy 375

- reduction in legal input through the adoption of existing licences rather than drafting new licences in each agency/department

- enhanced public relations, potentially leading to increased use of other services

- choice of licences offering flexibility

- a framework of rights clearances conditions in future projects or databases.

From the perspective of the users of public sector information, the benefits would be:

- wider access to previously unavailable digital resources

- clear, unambiguous and permissive conditions of use

- usability at the point of discovery

- reduced confusion through a common set of well-recognised licences and symbols

- peace of mind through knowing that re-use is legal and encouraged

- ability to re-distribute and make derivative works (in permitted cases)

- ability of search engines to offer searches based on the conditions of use.

9.11 The benefits of implementing CC licences, as far as practicable, across the public sector need to be contrasted with the disadvantages of the array of non-uniform licences presently in use across the public sector:

- The present proliferation of licence types causes confusion for users and will act as a barrier to acceptance. By using a licensing scheme that is already widely used (over 140 million resources are already linked to CC licences world-wide) familiarity will encourage use.

- When data or information resources from different sources are aggregated to produce collective or derivative works, problems of licensing the new work are reduced if the component works share licence conditions.

- If a new licence is created based on CC then trademarks, symbols, human-readable deeds and metadata associated with CC cannot be used.

9.12 These advantages and disadvantages generally coincide with those identified in the Common Information Environment and Creative Commons: Final Report to the Common Information Environment Members of a Study on the Applicability of Creative Commons Licences (2005) by Intrallect and the University of Edinburgh.19

10. DIGITAL RIGHTS MANAGEMENT

10.1 One of the greatest technological advances available online with the CC model is the digital rights management feature which automatically embeds metadata into the data prior to download wherever it is transmitted online. This enables users to know who the custodian of

376the data is, copyright ownership details, specific terms and conditions, and other details about the data to assist a user to assess its fitness for purpose.

10.2 Information Queensland will assist in the initial pilot for the digital rights management feature and requires that the system will:

- attach the terms and conditions to the datasets to be made available to potential downloaders

- enable users to select datasets to download

- enable users to aggregate selected datasets and accompanying terms and conditions

- enable delivery of selected datasets to the user

- enable the capture and storage of download activity and terms and conditions supplied.

10.3 The digital rights management is dependent upon the infrastructure being compliant with the Government Enterprise Architecture and associated Information Standards. Using the terminology of the Government Enterprise Architecture, when data and its associated information are delivered to a user the bundle of information is referred to as a ‘payload’ and the user is a ‘consumer’. Under the proposed model, the payload delivery system would:

- allow the consumer to search the metadata repository

- allow the consumer to view the full metadata record for a selected dataset

- authenticate the user is permitted to download that dataset

- present the consumer with licence and usage restriction information

- handle or offload any e-commerce component (for cost recovery or statutory fee collection)

- create a payload containing the dataset, metadata and licence – if possible, the licence and metadata will also be embedded directly in the dataset.

10.4 An initial assessment of issues associated with the technical implementation of a digital rights management system has been made (Attachment 5 – Considerations for the Technical Implementation). A key technical requirement will be that the system will select and present a licence to the consumer, which must be accepted before data and information may be accessed, and which constitutes effective notice to the consumer of the terms under which they can access and use the data and information.

11. IMPLEMENTATION

11.1 Stage 2 of the project determined that a clear policy position supported by a sufficiently detailed set of guiding principles should underlie open content licensing to assist agencies in implementing it. Experience in Australia and internationally to date indicates that the development and adoption of a general policy and guiding principles are crucial steps in the implementation of systems designed to promote access to and re-use of public sector information. The importance of basing an access regime on an appropriate policy and guiding principles has been recognised in the Intrallect and University of Edinburgh report commissioned by the UK’s Common Information Environment, Common Information Environment and Creative Commons (2005) and in the Australian Government’s Office of Spatial Data 377Management, A Proposal for a Commonwealth Policy on Spatial Data Access and Pricing Policy (2001).20 Statements of the principles underlying access and re-use are also central to the EU Directive on the re-use of public sector information of 2003 and the OECD’s Declaration on Access to Research Data from Public Funding (2004) (‘OECD Declaration’).21 (See Attachment 6 – Background Research, for clear statements of principles.)

11.2 A question raised during the project was whether a new ‘licensing’ Information Standard would be required, or whether a new approach to licensing could be handled using existing or draft standards. A review of key Information Standards indicates that the Queensland Government has moved towards an ‘open content licensing’ philosophy and this is reflected in some Information Standards, including IS33, IS25, and IS44.

11.3 IS33 states that ‘Government information must be made accessible, directly or indirectly, to citizens of Queensland and those doing business in Queensland at no more than the cost of provision and in a manner which provides reasonable access to the community unless statutory requirements vary the access and pricing arrangements. Certain types of information will be required to be freely available’. While IS33 does not deal specifically with ‘licensing’ as such, it does promote access to government information. This standard is due for review. An option to be considered during the review is whether the standard should include stronger principles related to access to government information, and whether the name should be ‘Access, Use and Pricing’.

11.4 IS25 was developed to provide guidance to agencies on how to appropriately manage and commercialise their intellectual property assets. Under the intellectual property policy agencies are responsible for managing the intellectual property assets they generate or use and commercialisation of intellectual property by an agency is generally ancillary to that agency’s core business. Recognition is given to staff that develop intellectual property with commercial opportunities (including moral rights). The general principles on which this policy is based include that agencies:

- are responsible for the management of intellectual property assets owned or used by the agency, in a publicly accountable manner, in accordance with all relevant legislation, policies and guidelines

- should take appropriate and necessary steps to identify, secure, preserve, maintain, and, where appropriate, advertise the availability of commercialisation opportunities and enhance the operational and commercial value of intellectual property assets owned or controlled by the agency

- should not expend a significant amount of resources to further develop an intellectual property asset for the sole or substantial purpose of commercialisation of that asset

- should minimise the risks associated with the use of intellectual property assets and endeavour to commercialise such assets in a manner which does not expose the agency or the State to unnecessary or disproportionate risks. In the case of commercialisation agreements, this may involve ensuring that any warranties which the public authority gives are appropriate and that legal agreements include liability caps or indemnities from liability.

37811.5 A key rationale for IS25 and the intellectual property policy is that government agencies can produce increased revenue, more efficient operation of service delivery, opportunities to develop local industry and deliver on the Government’s commitment to a Smart State.

11.6 In addition to IS33 and IS25, the Office of Government ICT, Department of Public Works has developed a draft Information Standard for custodianship – IS44 – which in its current form contains the following principle in relation to data accessibility and protection:

Protecting the accessibility of data is fundamental to creating accessible and responsive government service delivery. To ensure maximum accessibility, use and interoperability of data across government and the community agencies must at a minimum:

- ensure access to data is maintained and readily available to authorised users

- provide licensing and metadata statements with any data that is released/shared

- ensure data is captured and maintained to a standard which facilitates its interoperability between systems

- establish licensing and contractual arrangements/agreements and charging regimes that are consistent with the requirements of IS33

- ensure that the privacy, security, confidentiality, copyright and intellectual property obligations are addressed when using and releasing datasets.

11.7 The two options for further establishing the principles of open content licensing across the Queensland Government are to:

- add licensing features where appropriate to existing standards e.g.:

– reviewing IS33 to Access, Use and Pricing and including specific principles to support open content licensing

– adding specific implementation advice to IS25 that includes the use of CC licences for government data and information

– proposing an additional principle to be included in the Draft IS44: ensure that data is available for re-use unless privacy, confidentiality, security or highly commercial restrictions prevail.

- establish a new standard on access and use which incorporates principles similar to those in the EU Directive and OECD Declaration.

11.8 The Queensland Government’s adoption of an open content licensing framework will support its open access objective and make government information available in a manner which provides reasonable access to the community.

11.9 It has been determined that further work is required to enable the CC licences to be implemented and this work is outlined in the Government Information Licensing Framework Project Stage 3: Draft Project Plan which was provided to the Strategic Information and ICT Board on 27 September 2006. An application for funding for Stage 3 has been submitted to the ICT Innovation Fund and Microsoft Program Committee to cover:

- further legal drafting to cover non-compliant information transaction

- development of the digital rights management system and implementation of the technical architecture 379

- pilot – 2 or 3 case studies (Office of Economic and Statistical Research, Information Queensland and Infolink Natural Resources and Water, Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, Department of Local Government, Planning, Sport and Recreation), more detailed consideration of the pilot agencies’ business requirements, a closer examination of all information transactions of the pilot agencies to identify issues which need to be addressed and to confirm the CC and other licence type are appropriate to meet the agencies’ overall business requirements

- extension of the whole-of-Government metadata profile to include relevant fields e.g. Access Rights, Copyright, Citation

- whole-of-Government metadata audit to update metadata with licensing information

- Business Case including cost-benefits analysis

- Cabinet Submission for consideration of whole-of-Government implementation

- International Open Content Licensing Conference (with QUT) implementation.

The following key data assets are disseminated by Information Queensland and are proposed to be included in Stage 3 in the first pilot:

| Proposed data asset | Custodian agency | Draft CC licence type |

|---|---|---|

| Cadastre | Natural Resources and Water | Attribution–ShareAlike 2.5 |

| IPA planning schemes | Local Government, Planning, | Attribution–NoDerivs 2.5 |

| Sport and Recreation | ||

| Population projections | Office of Economic and Statistical Research | Attribution–NoDerivs 2.5 |

| State Digital Road Network | Main Roads | Attribution–NoDerivs 2.5 |

11.10 The Government Information Licensing Framework Toolkit has been developed to assist custodians in implementing open content licensing including the use of CC licences. (See Attachment 1 – Draft Government Information Licensing Framework Toolkit.)

12. CONCLUSION

12.1 Stage 2 of the Government Information Licensing Framework Project has confirmed the applicability and benefits of using the CC licences for key data custodians within the Queensland Government.

12.2 Background research undertaken during this stage has confirmed that a range of jurisdictions are moving to more open content models for licensing data and information and that governments particularly are improving the control of intellectual property in their data assets, as well as access to and re-use of public sector information by using models such as CC.

12.3 The project has identified the potential to work directly with the CC organisation to enable the implementation of the licences in the government environment. 380

12.4 This stage assisted in determining that the combination of CC licences would support the majority of data access and use transactions conducted by the Queensland Government.

12.5 It has been determined that further work is required to enable this licensing model to be implemented and this work is outlined in the Government Information Licensing Framework Project Stage 3: Draft Project Plan which was provided to the Strategic Information and ICT Board on 27 September 2006. An application for funding for Stage 3 has been submitted to the ICT Innovation Fund and Microsoft Program Committee.

ATTACHMENT 1: DRAFT GOVERNMENT INFORMATION LICENSING FRAMEWORK TOOLKIT

INTRODUCTION