3

Our ways of learning in Aboriginal languages

Abstract

Aboriginal culture has not been lost – just disrupted. Our ways of knowing, being, doing, valuing and learning remain in an ancestral framework of knowledge that is still strong. Through Indigenous research in western New South Wales that explores these knowledge systems in land, language, people and the relationships among them, eight ways of learning have been identified. This chapter makes recommendations for using the eight ways in the teaching of Aboriginal languages in schools.

Tracking the pedagogy in our language

There is deep knowledge in our languages. There is a spirit of learning in our words. This is more than just knowledge of what to learn, but knowledge of how we learn it. This is our pedagogy, our way of learning. We find it in words about thinking and communicating. We find it in the language structure, in the way things are repeated and come around in a circle, showing us how we think and use information. The patterns in stories, phrases, songs, kinship and even in the land can show us the spirit of learning that lives in our cultures.

If your language has just one word for speak, tell, say and talk, then it is telling you something about the role of speech in learning – particularly if that same word carries the negative meaning of forcing somebody to do something against their will. You will go softly with the way you instruct, keeping in mind that the word for thinking and knowing in that language is also the word for loving. The language itself is giving you a picture of how to approach language education in your place. It might be telling you to give students a healthy balance of supportive discipline and independence. This is strong pedagogy.

38It is true that all Aboriginal languages are different and carry their own ways and values, but we also have many things in common. That Aboriginal idea of balance between social support and self-direction is one of them. To use the Aboriginal concept of balance – if that is a part of our way – then it makes sense for us to find what pedagogy we have in common with non-Aboriginal ways too, balancing the two worlds. If we find the overlap between our best ways of learning and the mainstream’s best ways of learning then we will have an equal balance.

From our language and our land knowledge we know there are always connections among all things, places where different elements are no longer separate but mix together and become something else. This way of working gives us new innovations as well as bringing us together. There are eight ways of learning that have been found at this interface of two worlds. This chapter not only shows those eight ways but also follows them in the way it is written. First we see how each of the eight ways came out of a research project and then we see how to use the eight ways in your Aboriginal language classroom.

The story

Story takes you up, and then down, leaving you in a place that is higher than before. It runs through everything in land, body, mind and spirit, tying together the shape of learning for all peoples. So this narrative about a western New South Wales (NSW) research project continues through these next eight sections, tying all of the elements together.

The eight ways came from Indigenous research, which is research done by and for Aboriginal people within Aboriginal communities, drawing on knowledge and protocol from communities, Elders, land, language, ancestors and spirit. These things formed the methodology – the ways and rules for working in research. As the research took place across western NSW and the researcher was a man with kinship ties in the far north and ancestral ties in the far south of Australia, that methodology had to work in the middle ground among different Aboriginal nations. It also had to work in the middle ground between Aboriginal knowledge systems and western learning systems.

Messages from land and spirit gave shape to the methodology, the way of working. Work was done with river junctions and interconnecting songlines that brought together different cultural knowledges. The work of Indigenous researchers who had gone before was also followed, bringing to the centre the idea of the cultural interface of Dr Martin Nakata from the Torres Strait, the idea of a dynamic overlap of knowledges from different peoples. This idea of the interface was found not only in research literature, but in Indigenous law and stories from all around Australia and the world. 39

The map

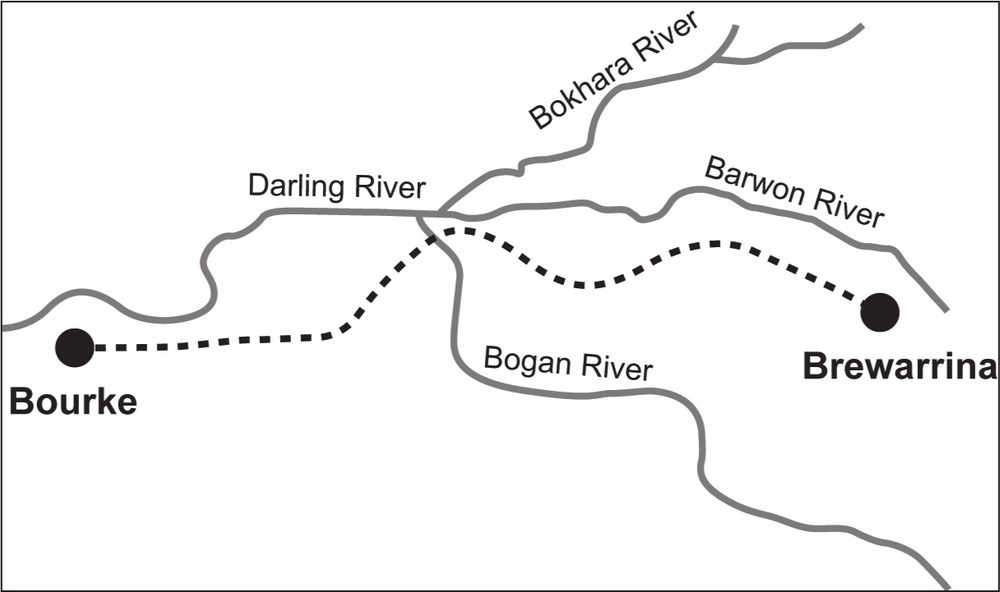

Following the model of a local river junction, the Aboriginal researcher and a local Ngemba mentor worked with non-Aboriginal education experts at a place between Bourke and Brewarrina where three rivers meet to become one. This river gave the shape for a map of the project, a way to bring together the ways of learning from different cultures and find what they had in common, then follow those common ways. The interface among three Aboriginal and western learning frameworks was found and the eight ways were born from that, carrying the best of both worlds down the river.

Figure 1. The map.

The silence

In our world the deepest knowledge is not in words. It is in the meaning behind the words, in the spaces between them, in gestures or looks, in meaningful silences, in the work of hands, in learning from journeys, in quiet reflection, in the Dreaming. The eight ways were tested on journeys following the river along a codfish songline linking to the Murray River, tested in ceremony, tested in the carving and use of tools to represent them. This silent knowledge was explored with the hands and the feet. A lot of this knowledge can’t be shown with words in a book like this – but in our way it would be up to the Aboriginal listener, and in this case the reader, to fill in those gaps themselves – to fill it with their own cultural knowledge and teaching experience.

The signs

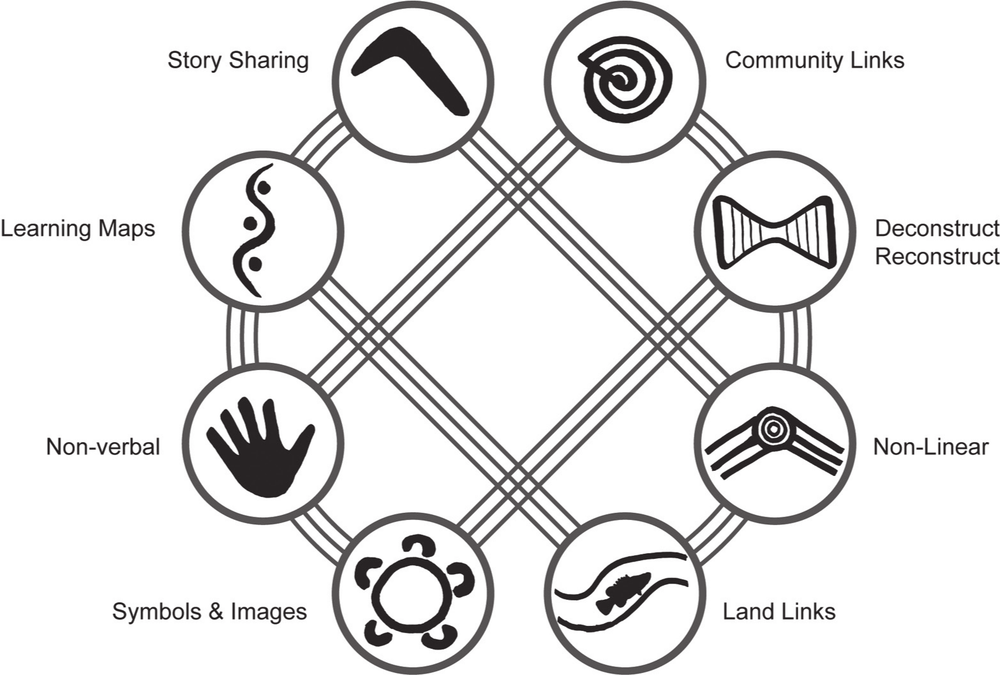

That same silent knowledge was also explored with the eyes, through the signs and images we all see – our way of visualising and sharing ideas that has been with us forever, the things that make up our mental landscape. These were not only signs 40from the land and animals, but also signs made by people. This became a way of finding, working with and sharing the eight ways through images. The images of the eight ways were brought together in one picture that was modelled on a kinship system to show they are not steps to follow, but dynamic and interactive processes.

Figure 2. The eight ways as symbols.

The land

Entities in the land like stones, animals, plants and rivers all provided knowledge through the research to uncover and share the eight ways. The languages and stories of the land were a part of this too. For example language and Dreaming stories from one language group showed that learning, thinking and all other journeys take a winding path, suggesting that there are no straight lines to knowledge or outcomes. This knowledge was tracked further into the land, walking and talking with local people down winding rivers and in the winding tracks of blue-tongue lizards. This winding path became the symbol for one of the eight ways and provided a map for thinking about and working with the other seven ways.

The shape

The winding path provided a shape for thinking outside of the straight line, that Western linear logic. But there were other shapes as well, particularly circular ways 41of thinking found in kinship systems, land knowledge, art and language structures. There was also a two-way shape, a balance and symmetry where opposites meet. That way of thinking brought home the cultural interface, allowing an understanding of the shapes of logic from different cultural viewpoints. For example it became clear that not all western thinking was in a straight line. It was also non-linear, in the way they think about cycles in science and in the recent tradition of lateral thinking that zig-zags in a similar way to the winding path mentioned above. All eight ways came to be developed in this way, finding the best ways of thinking in common across cultures, coming from two sides and meeting in the middle.

The back-tracking

One shape that came from the best thinking in both ways was from the idea of back-tracking through knowledge, a process with a shape like two funnels coming together at a centre point. In this way of learning you always give a model of the end product of any learning right at the start. This model can then be broken down into increasingly smaller parts then put back together – deconstructed and reconstructed. At the same time each piece must be seen as part of the whole, and as part of a purposeful activity in the real world. This way was seen in the mainstream practice of scaffolded literacy as well as in the Aboriginal learning of traditional cultural practices.

This was used in the research to help develop the eight ways by examining other models and research projects done by Indigenous people from around the world. It gave a vision of the end product, then a way of back-tracking through the process before attempting to go forward. This story you are reading now is starting that deconstructing–reconstructing process – giving an example of the eight ways in action, a model that will be broken down in more detail then put back together with the reader later in the chapter.

The home-world

In the research to find the eight ways, knowledge was always centred on the local communities in the region. It began with local knowledge then spiralled out to national and international literature and practice. It spiralled because no matter where knowledge came from in the world it was always found while orbiting out around the local centre, grounded in the question, ‘What does this mean to local people and how will it benefit the local community?’

The researcher not only worked with local knowledge and contexts but also left the product of the research with the local community. This meant passing on these eight ways to be used by local schools for connecting with the community through the curriculum, and to be used by community people in developing language or cultural programs that have integrity and intellectual rigour in our own ways of knowing. The researcher does not own this way of working, nor does the Department of Education or a university. The eight ways came from this western region and belong to this 42place. At the same time this way of working also links to other contributing regions and peoples around the world, but its centre is here.

Detail of the eight ways

The first way is story sharing

The killer boomerang symbol is our narrative model (see Figure 2, top left). Your story starts with normal life (handle end) then builds to a climax (boomerang elbow), but at the end (boomerang tip) when things calm down and return to ‘normal’, life is never the same. It’s at a higher place than before because new knowledge has come.

This is a powerful tool in the Aboriginal language classroom. You tell your personal stories about any topic right at the start, and make sure you give the students a chance to share their stories as well. That way you are drawing on everybody’s home culture and knowledge for the lesson. You can build units of work around stories too. You draw culture, vocabulary and grammar items from the story itself, rather than teaching isolated cultural lessons, lists of words and language structures.

The way in action

In one Stage 4 Aboriginal language program in western NSW each unit was based on a story. They didn’t want to teach body parts first, then family words, then animals and so forth, so instead they took their lessons from the story. They learned some body parts, animals and family names that were mentioned in the story, not as lists of words, but as parts of whole sentences in language that combined these things in a culturally meaningful way. In this way they were living Aboriginal language and culture, not just remembering some Aboriginal words.

The second way is learning maps

The winding path symbol represents a journey. Learning journeys can be drawn as a map with points of understanding indicated along the way rather than at the end. Learning journeys never take a straight path but wind, zig-zag, or go around. It is best to base these maps on the land where your language is from.

In the Aboriginal language classroom these learning maps help students to see where they are and where they are going in their journey of language learning. You can have whole units or even the whole scope and sequence for the year mapped out in this way. This can be based on the local landscape with local seasonal changes worked in. For example students might know they are about to begin their Term 1 assessment piece when the nights start getting cooler, when they see a seasonal indicator on the map in their classroom. Criteria for quality work, vocabulary lists and even attendance data can be added to this visual map.

The way in action

In one Stage 4 Aboriginal language program in western NSW the teacher mapped out 43the scope and sequence for the year based on a road that runs through her country. Hills at the start of the journey represented early challenges like getting pronunciation right. Each bend in the road represented quarterly assessment tasks, while other landmarks indicated changes to new topics and units of work. A significant totemic animal from that language group was shown on the map, along with its tracks, to indicate that this map showed the journey of that animal.

The third way is non-verbal learning

The symbol of the hand represents all knowledge that can be understood or acquired without words, including gestures, inference, expressions, eye movement, kinaesthetic learning, images and revealed knowledge (for example dreams, insight, inspiration, reflection).

In the Aboriginal language classroom this is a key element of culture and pedagogy. It is important to use total physical response activities where physical actions are used together with the words and ideas students are learning. The Aboriginal teacher uses facial expressions, body position, mime and gestures to communicate the meaning of language words and phrases, and this ensures that students are linking their language not to an English translation, but to their own cultural and personal meanings. We also use observation, watching people for the real meaning behind their words, and this skill can even be used with print – reading between the lines to find implied meanings. This is useful if you have to use an English text written by a non-Aboriginal person about culture, as it helps us to be critical and keep our own standpoint, to defend against colonising influences. With listening, as well as reading, a lot of information in our traditions comes from the learner filling in the blanks of speech or text. Finally, as Aboriginal language teachers we also need to facilitate that sense of personal spiritual connection where non-verbal learning comes from land, ancestors, the Dreaming and even our own bodies.

The way in action

In one Aboriginal language program in western NSW a traditional song about a process in the land was taught to students, but the focus was not on a word-for-word translation. The deeper knowledge of the song was unspoken, but conveyed through gestures to accompany the song, as well as through tone and expression. The tone was serious business and had to be done just right. There was meaning in the rhythm of the song associated with the land process that the song helps to bring about. Deeper layers of meaning came from repetition and performance of the song in different contexts. When they got it right, evidence of the learning came when the land did what the song was asking it to do – a natural event that had not happened in a long time – it rained.

The fourth way is symbols and images

This symbol represents people sitting at a meeting place yarning. It is an example of a simple symbol that contains a lot of deeper information and understandings. 44Aboriginal thinking is often done in images or shapes rather than words. Concepts can be shown this way.

In the Aboriginal language classroom this can give the same outcomes as the nonverbal way of learning – students linking language to their own cultural meanings rather than to English translations. For example, if a student has a picture of their mum labelled Gunhi, instead of writing in their books, ‘Gunhi – Mother’, this is linking the language to their own reality rather than to an English translation. Symbols and pictures can be used to represent words and concepts, or even learning processes. You can see this way at work in the learning maps as well.

The way in action

In one school in western NSW some students created a sand painting using Aboriginal symbols taught by a local Elder. Another group made a story map from a local Dreaming story, using both pictures and words to show where the main incidents in the story occurred on country. Later a group of Stage 4 Aboriginal language students studied these images, linking them to the appropriate words and story in language. They then made message sticks about a common theme using those images and others to represent language words and cultural concepts based on the theme of the unit. For oral assessment they were expected to ‘read’ the symbols on the message sticks to the class using only the language words they had learnt.

The fifth way is land links

The symbol represents a river. All the animals, plants and geographic forms in land and water contain deep knowledge. They also provide metaphors for concepts. Knowledge of local land and place is central to Indigenous ways of knowing.

In the Aboriginal language classroom this way is crucial as we are teaching the languages of the land. This link to land and country should always be present as it ensures cultural integrity. For example we know that often our Dreaming stories are misrepresented as fables or children’s tales, and we can tell when this is happening because land and place are left out when people tell our stories in this way. An indication of cultural integrity in storytelling is that land and place are central to the story. There’s no story without place, and no place without story. So linking your lesson content to land is one way of maintaining cultural integrity in your language program.

The way in action

In a Stage 4 Aboriginal language course in western NSW a unit of work was planned in which the class mapped out the events of a local Dreaming story on a geographical map of the area, following the river system. Different kinds of country such as redsoil and blacksoil were to be labelled in language along with landmarks, animals and the main sites of the story events. Other stories that intersected with this one at certain places were also mapped showing the way stories from other country connected with 45this one at special places. This leads into a comparative study of regional languages and cultures.

The sixth way is non-linear processes

The symbol represents circular logic at the centre, and the lines either side show the interface between opposites. In Aboriginal worldviews opposites meet to create something new, with symmetry and balance concepts valued above oppositional thinking. This sign has been carved into a boomerang (Figure 3). In this way we can also see that learning doesn’t go straight from one side to the other. It bends out to the side, bringing in knowledge that might seem to be off topic but that creates deeper understandings and richer learnings. This also shows that at low levels of knowledge there is a wide gap in cross-cultural understanding, but when you find the higher knowledge from both ways they come together with many things in common.

In the Aboriginal language classroom this way is a hard thing for which to plan. It is the most difficult of the eight ways to understand. It is best to think of it as how you move and think in hunting, gathering or fishing. You don’t go straight and you don’t think of just one thing you want to collect at the end. You think of a thousand things in the landscape and your experience that help you to find what you’re looking for, and you seldom walk in a straight line to find it. For us this way is about giving ourselves permission to follow our own ways of approaching a topic, without feeling like we have to change culture to fit Western ideas of a learning progression from A to Z.

The way in action

In the planning of a Stage 4 Aboriginal language course in western NSW we were looking at how to teach a continuous tense that was part of a story for study. Should we just say, ‘Here is the suffix and you use it this way. Now, do some practice sentences’? No. That’s not how we learn. So we looked at the connection between this suffix and the body function to which it is linked. We told funny stories about that and made a lot of rude jokes. Then we looked at a song about this, and the way a sense of striving comes through that body function and through a continuous action. We decided to use humour and song to teach the students the deeper meaning behind the way you use that continuous tense suffix. What was a grammar item before became a cultural lesson. The students would come to it from that different angle and in doing this they would find a deeper meaning and retain the knowledge better.

The seventh way is deconstruct/reconstruct

The symbol of the Torres Strait Islander drum represents the way knowledge can be learned by back-tracking through the context and the whole form in supported stages, then reproduced independently. The shape shows a balance between independence and support. This can be seen in literacy scaffolding programs as well as in traditional activities like learning corroboree. 46

In the Aboriginal language classroom this way gives a supportive structure to what you teach. Pronunciation, spelling and memorising words doesn’t come at the start but in the middle. You start with a whole text as a model – like a dialogue, a Welcome to Country, a song or a story. You look at the social and cultural context of this, give it a purpose, and model how it is used. You look at the structure of it; teach the cultural codes you see there, unpack it and work through the stages of learning you find in the language text. Only then, in the middle, do you get to what Western education refers to as ‘the basics’ – the pronunciation and spelling and so on. From there, our students use their strengths as independent learners and we support them in putting the language back together to create their own meaningful texts and yarns.

The way in action

In a Stage 3 Aboriginal language class in western NSW students were supposed to be memorising the names of body parts. But they seemed to be more interested in teasing each other. So the teachers presented a dialogue of two students teasing each other in language. The insults were made up of body parts combined with pronouns and adjectives. The teachers performed the dialogue several times with gestures and expression getting the meaning across to the students. They discussed cultural ways of dealing with conflicts from past and present. They performed the dialogue several times, with students later following the text on a written handout, joining in and mimicking the funnier parts. They examined each line and looked at how the structure was repeated. They sorted the words into pronouns, adjectives and nouns and practised pronunciation. They kept these lists in the same order as the sentence structure and then expanded those lists with new vocabulary. They used these lists to create their own insults, then in pairs built these into a funny dialogue that they practised and performed for the class.

The eighth way is community links

This symbol is Brad Steadman’s knowledge spiral from Brewarrina. It shows how, in the Ngemba way, creation patterns at the local level are repeated at the non-local level throughout the universe. It also shows how non-local information is viewed and used from local standpoints for community benefit, with all learning returned to the community.

In the Aboriginal language classroom this is important because, while you are drawing on local traditional knowledge in your school program, you are also promoting and maintaining this knowledge in the community. There is a give and take here. Another aspect of this is respecting the diverse group identities of students in your language class and school community, making sure they bring their unique cultural standpoint to the learning of this language. Our peoples have always been multilingual, learning the languages of other groups but always with the cultural protection of maintaining a home identity at the centre. When there are students from other language groups in your class their culture must be respected, and they must see the relevance of learning this different language with a view to developing the skills to learn and promote their 47own language. With every bit of knowledge you teach, students should clearly see the answer to the question, ‘What does this mean for me and my mob?’ This includes your non-Aboriginal students. Then that knowledge should be returned to the community in useful ways. The most obvious way to do this is through performances and displays, but community development and awareness projects are also possible.

The way in action

In a Stage 4 Aboriginal language course in western NSW students organised family language days to promote language revival, teach language to the community and showcase their work and skills for community evaluation. They performed songs and put on plays in language that were based on Dreaming stories, set up language activities for community members and held competitions. This gave a purpose to all the work the students did in class, as they knew every piece would end up being judged by their families. Community engagement and attendance at these days has been strongest when they have been held outside the school grounds, in a community space.

How to use all eight ways in a unit of work

It is best to start with community knowledge and a story related to the content. Share your stories and hear the students’ stories to find out what they know already about the topic or related topics. Whatever you want the students to be able to do by the end of the unit, model it first. Get them to work with those models in ways that don’t need words, like watching or copying your body language and gestures for meaning, total physical response activities, cutting up written and visual texts and sequencing them, looking for the unspoken meaning behind the words or just quietly reflecting. Question outsider knowledge sources and test for truth and integrity. Find the deeper knowledge of craft work, such as women’s business in weaving, and always link these to language use. Create a visual map of the learning and make maps of the land to show the places and connecting paths of stories. Make mind maps of ideas. Always link content back to land and place. Use images, colours and symbols to teach new vocabulary and concepts like grammar and structure. Don’t build to final outcomes, but rather find the outcomes along the way and don’t be afraid to go off the straight track to find them. Support students in the first half of the unit by backtracking though the modelled work then guide them towards working independently in the second half. Finally return the learning to community for community benefit and for them to evaluate. Allow Elders and other keepers of knowledge to have a say in the criteria for success.

We already do this!

The truth is these eight ways are not even needed if curriculum developers work with cultural integrity in a balanced partnership between the community and the school. The eight ways will be strong in a program then, even if the participants have 48never heard of them. An example of this is the Dubbo Wiradjuri program which was written before the eight ways were developed, but still covered all eight elements (see McNaboe & Poetsch, this volume). This occurred because the programming team was working with cultural integrity and there was community knowledge at the centre of everything with Aboriginal people leading the project:

- Story was embedded in each unit as a source of knowledge, themes and vocabulary, rather than having isolated lists of body parts, animals, greetings and so forth

- Story-mapping activities put these stories into the context of country. Genealogy mapping and visual maps of historic events were also planned

- Gestures, total physical response and craft activities were included to enhance non-verbal knowledge skills. Deeper unspoken meanings and values behind cultural activities, texts and vocabulary were explored

- Images were to be used in story work, artwork and the learning of vocabulary

- Most concepts were related back to land and place, particularly the river

- Structures like family trees and timelines were redrawn in familiar non-linear ways, for example family forests. Local concepts of balance were introduced, such as in health and diet

- Creating products for assessment always began with examining model texts

- Units were grounded in local knowledge through Elders with each unit being centred around a rule written in Wiradjuri from a list of Elders’ instructions for living on country. Assessment focused on ways to promote those rules in the community.

Cultural integrity in language instruction

These eight ways are a call for cultural integrity, for an end to culture as a tokenistic add-on. Johnny cakes are good, but if we’re not using language when we make them, then why are we doing this with our class? We need to learn through culture, not just about culture. Painting some dots on a cardboard boomerang and singing Humpty Dumpty in Aboriginal language is no longer good enough. These eight ways of working are for using cultural knowledge not just in what we teach, but in how we teach. Doing that puts us on an equal intellectual level with the education business of pedagogy; allows us to make partnerships as teachers of language courses that are on an equal academic footing with mainstream subjects.

This partnership needs to create an equal dialogue: an interface between our ancestrally-perfected ways of learning and departmental policies and frameworks for teaching. At that high level of knowledge we find more common ground than differences across cultures. This gives rise to respect and an empowerment of community. When our ways become part of planning at that higher level our values can also gain a place in the organisational structure of the school, giving us a true voice and true agency in education. Our culture and language is currently in the curriculum at the level of extra content. This has opened the door for us to bring it up to the next level. 49

Language and culture is the first step, the key. Aboriginal language teachers have the power to lead change in education, but there must be integrity in this as well as high intellectual standards. Rather than reproducing tokenistic souvenirs of culture we must put forward our deep knowledges to set the standard and demand quality from the best that mainstream learning has to offer. Remember that at low levels of knowledge there is only difference across cultures but at high levels there is common ground. Every one of the eight ways of learning shown in this paper is present in western and other cultures as well as our own. Our higher-order thinking processes need to be revealed in cultural items that are currently seen as primitive, simple or exotic. We need to bring the deep knowledges from different cultures alongside each other and find that common ground for a true act of reconciliation.

Figure 3. Not just ‘artefacts’, but eight tools for learning.50

1 Department of Education & Training, New South Wales.