11

Whose language centre is it anyway?

Abstract

Typically regional language centres are referred to in the context of supporting documentation, materials production and school programs, and often employ university-trained linguists and other ‘experts’ to work on individual languages. Despite many successful projects facilitated by the Kimberley Language Resource Centre, this approach did not result in sustainable revival strategies for Kimberley languages and has not dramatically increased language use. We describe how the organisation has in recent years gathered Aboriginal community perspectives on language revival resulting in a revision of the strategic plan and management model. The organisation’s focus is now strongly directed towards community-managed revival with emphasis on promoting pre-school language acquisition. After summarising the reasons for changing direction we refer to the strategies being used to support it. We then go on to discuss how this approach struggles to receive support outside the Aboriginal communities the organisation works with. Grant bodies, particularly government ones, are reliant on Western academic perspectives on maintenance and revival when assessing funding submissions. In neither the organisation’s context nor the social context do they accept with equal validity Aboriginal people’s perspectives on how to revive their own languages. The Kimberley Language Resource Centre was established under a model of self-governance in the early spirit of self-determination. After briefly describing the operational changes and current strategies we conclude by setting out the difficulties of getting support for Aboriginal self-determined strategies. We do this by asking two questions: (a) whose responsbility is language continuation at the community level and why does the answer, the community, pose a problem for the Kimberley Language Resource Centre? and (b) why are Aboriginal revival strategies seen as less valid than the strategies of Western academia and education?

132The aim of this paper is to tell a story. The story covers the beginnings of the organisation, a summary of its operational practices past and present, a summary of its project strategies and finally a discussion about where the Kimberley Language Resource Centre (KLRC) is placed in the fight to continue the Aboriginal languages of the Kimberley, a region of great linguistic diversity. It is not possible in such a short paper to go into great detail about differing academic versus community views on endangered languages work. The KLRC has employed and continues to employ a wide variety of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal administrative and language staff and consultants. Naturally each comes with their own worldviews and their own opinions on what is best.1

However it is important to establish clearly that the the KLRC is an Aboriginal organisation which, under its governance model, is directed not by its staff but by its members and the Board of Directors2 elected from the membership. Successive boards have taken the advice of its staff, particularly linguists, but in recent years directors have begun to take more into consideration what needs are being talked about at the grass roots level. It is the role of both board and staff to find a resolution to those needs in the overall context of language continuation.3

Background to the organisation

Aboriginal activist, anthropologist and linguist Gloria Brennan first put forward the idea of Aboriginal, locally controlled ‘institutes of Aboriginal languages’ (1979, pp. 52–55). Various Kimberley Aboriginal people and linguists working in the area consulted with Aboriginal groups and organisations about similar ideas. In 1984 funding was

133received to run a pilot study across the region called the Kimberley Language Support Project. The subsequent report Keeping Language Strong (Hudson & McConvell 1985) identified a broad range of issues such as concerns about loss of intergenerational language transmission, concerns about the effect of English on the languages and the need for advocacy to government, as well as ideas on orthographies and resource development. All are still current topics.

The KLRC became the first regional language centre, incorporated in 1985. After 24 years the organisation has cemented its status with Aboriginal people as the peak representative body for languages within the region. It services an area of 422 000 square kilometres with six towns, approximately 50 remote Aboriginal communities and numerous outstations. Aboriginal people form almost 48% of the population, a target group of roughly 16 500 people (Kimberley Development Commission 2009).

The KLRC is governed by an elected board of 12 Aboriginal directors under the recently revised Office for Indigenous Corporation rules. The board, elected at an AGM, is chosen from and accountable to a 200 plus membership representative of the 30 or so languages still spoken in the Kimberley (about a fifth of the remaining national languages). Directors sit on the board for two years.4 The governance factor has an important role in setting an Aboriginal agenda, as will be discussed below.

Setting the direction

The recommendations from Keeping Language Strong are wide-ranging and refer to research, school programs, orthographies, repatriating materials and setting up and staffing an office. Recommendation 19 states, ‘community adults and schools jointly shoulder the burden of responsibility for keeping Aboriginal languages strong according to their particular expertise’ (Hudson & McConvell 1985, p. 89).

However, despite a summary of the issues precipitating the loss of languages in the community (pp. 35–37), proposals on how schools and the research community can work with Aboriginal people to change attitudes to language (pp. 40–44) and a mention of the importance of speaking to children in languages (p. 59), the report does not provide any specific recommendation on how Aboriginal people could overcome barriers to oral language acquisition in children in their community.

In 1993, internal correspondence to a coordinator from a linguist set out in stages a strategy for languages with less than 100 speakers (KLRC 1993). Stage one proposed to document the languages and make resources ‘before it’s too late’; stage two to use those resources in language classes, which would lead to stage three, the languages becoming first languages again. There is no timeframe set.

This literacy-based approach to language continuation was reaffirmed in a collection of draft policy documents from 1995. One states the ‘KLRC considers it important to undertake research work towards a grammar and a dictionary over the production

134of other kinds of ‘applied’ materials’ (KLRC 1995, p. 1). There was no indication in these policies how stage three above, languages becoming first languages using language teaching materials, could realistically be achieved. Neither is there mention of strategies to revive spoken language in pre-school children or promote community responsibility for that. Applied materials are noted to be impossible to develop without basic research having been done on the language first, that is a grammar or dictionary.

In 1998 a strategic planning process led to the production of the first Strategic Plan (KLRC 2000). The stated aims at that time were:

- Ensure the KLRC has the necessary physical and human resources to achieve its vision

- Advocate on behalf of languages at all levels

- Help keep languages strong by ensuring resources and information are accessible

- Keep language strong by undertaking community-driven projects

- Keep language strong by assisting with passing of language on to children

- Keep language strong by helping adults to learn

- Effectively monitor, evaluate and review the performance of the KLRC.

Even though passing on language to children is an aim, only one objective in the strategic plan refers to oral language. This is a reference to kōhanga reo5 that a coordinator in the early 1990s supported. Linguistic discussion of oral learning programs had taken place but within the context of Western education (compare McConvell 1986).

Aboriginal staff members from that time state the language nests were managed by the community because linguists did not appear to be interested. One language nest in particular was anecdotally successful as the participants, now teenagers, are speaking the language with some fluency. However funding from the Western Australian Department of Education was withdrawn in 2001 and lobbying for ongoing funding by the language groups involved did not succeed. Despite the well-documented success of language nests in New Zealand and Hawai’i, a strategy that might have ensured future language speakers was simply stopped.

Setting the management model

The focus of the pilot study recommendations influenced the organisation’s management model, since documentation and resource development relied on university-trained linguists. When a language group or community sent a request to the board the submission for funds invariably included wages for a linguist or other specialist to oversee discrete projects. Over the years a symbiotic relationship was created. Many Aboriginal people, particularly non-literate older generations, believed that language work through the KLRC only had a high status if a non-Aboriginal

135specialist was involved in the work and it resulted in a grammar, dictionary or other written resource.

One elderly language speaker, when asked to become involved in a bush trip for language learning, stated she did not need to teach the children herself because she had given all her language to the linguist who wrote it down in a big book which the children can learn from (pers. comm., 21 September 2006). This person is literate in her language, but the big book she was referring to is a PhD thesis.

An Aboriginal staff member says she too was completely convinced that if she put energy into helping linguists document the languages of the Elders, her language would continue. As a fluent speaker herself, a discussion never took place about orality and literacy, or that the relevance of the community being the managers of the language nests was that humans acquire first language(s) from what is heard before school and not what is written at school.

Even a previous coordinator of the KLRC was quoted as saying:

We’ve been tearing our hair out producing resources … And the producing doesn’t make any difference … If it was me making the decisions … I’d be putting all my energy into creating the circumstances for languages to be passed down to children. People keep thinking that we, the center, are going to make languages survive. They don’t like hearing, ‘You’ve got to do it yourself!’ (Abley 2003, p. 38)

Current situation

Reviewing the direction

Several factors prompted an internal review of the KLRC strategic direction in 2004:

- More and more people were questioning why children were not speaking languages despite all the work that had been done for languages.

- Between 2001 and 2004 a great deal of money for discrete language projects was sourced, but linguists or other project managers could not be found to initiate the unformulated projects.

- The backlog of projects had become overwhelming. A great deal of time was being spent chasing non-Aboriginal support with partial outcomes, for example unfinished resources or written materials unusable by the community.

- The assistant coordinator was promoted to become the first Aboriginal coordinator6 since the first year of the organisation.

A strategic planning specialist sourced through Indigenous Community Volunteers assisted with the development of a framework but the main review was internally managed. Questionnaires were sent out widely to both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people and groups. The board reviewed the Strategic Plan (KLRC 2000) identifying areas that were becoming unmanageable, unachievable or were not being met

136operationally. Previous projects were reviewed – particularly the incomplete ones – looking at how they were requested, how they were funded, how they were managed and what problems occurred completing them. Staff and consultants asked straightforward questions at meetings and workshops about what people saw as the issues for their particular language group or community, how they learned or did not learn their languages and what they believed would be the most effective way to revive languages and why.

The aims in the revised Strategic Plan (KLRC, 2005) and Business Plan 2008–11 (KLRC 2008) are:

- Encourage the oral transmission of languages and knowledge

- Advocate for Kimberley Aboriginal languages

- Build capacity in Kimberley communities to own and manage language and knowledge continuation

- Engage in partnerships, develop networks and fundraise.

- Strengthen the effective operations, resourcing and governance of the KLRC.

A comparison with the 2000 aims shows the change in direction to focus strongly on oral language transmission. The 2005 strategic plan still incorporates objectives for facilitating documentation and supporting schools, but the focus of how to meet those objectives is now external rather than internal.

The social context

Broader social issues affecting language continuation that the review made explicit were:

- lack of funds for communities to progress their own goals

- lack of information about theory and practice for possible language continuation strategies

- government intervention and top down management reinforcing disempowerment to change the way things are done in general

- a legacy of the colonial worldview continuing to shape beliefs about language and society and creating a barrier to language use

- inappropriate education curricula and lack of respect for cultural and linguistic values leading people to believe they must choose education in English at the expense of their own languages

- lack of knowledge of the right to maintain linguistic and cultural heritage7

- social and community issues preventing people becoming involved in language continuation strategies

- negative experiences of research influencing people to believe they have no other choices and thus choosing not to do anything rather than work within a documentation model

- lack of recognition of how language continuation happens naturally, for example cultural and ceremonial activities, nurturing of children through language(s) when they are very young, language use during natural resource management (NRM) activities.

137Social issues cannot be solved by the KLRC, but they need to be accounted for. Two linguists on separate occasions have told staff that many linguists will not work in Australia because they do not want to be involved in the social and political issues which accompany documentation work in northern areas. Both stated that graduates go to the Pacific in particular where they are ‘appreciated’ more than in this country (pers. comm. May 2007 & 2 September 2008). The KLRC does not see how it can fix this situation but it can work with the Aboriginal people who live with these problems daily to help them create space for language continuation in their communities.

Reviewing the management model

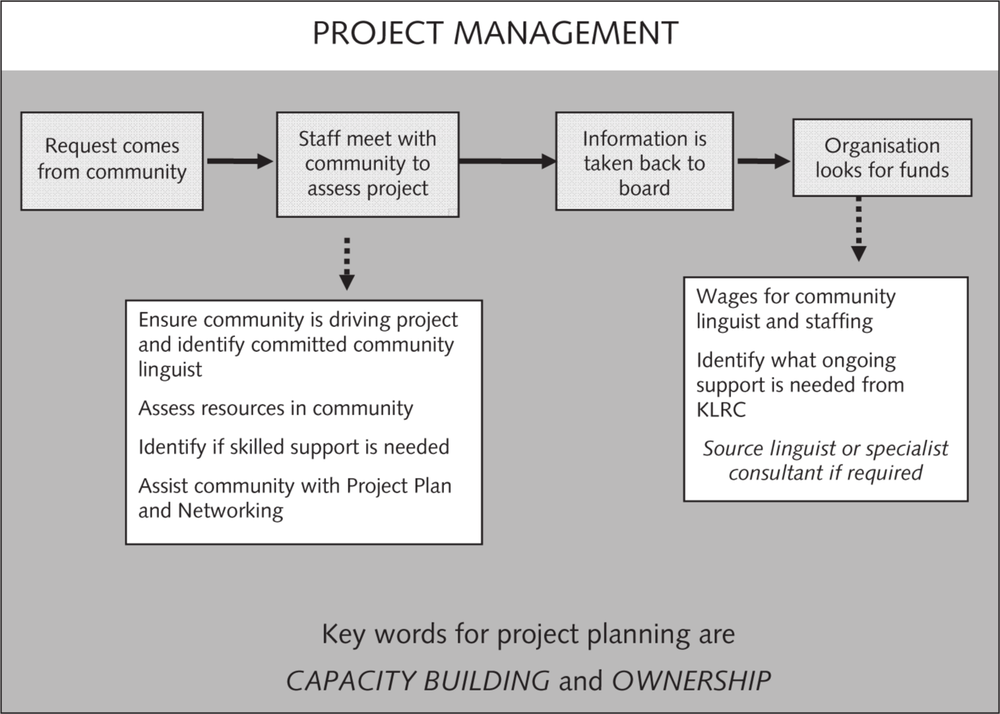

The results of this review led to the development of a new project management model (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Project management model. 138

The language continuation continuum

There is an urgent need to forefront the cultural divide between Aboriginal oral cultures and Western literate cultures. The divide is disempowering Aboriginal people because literacy is argued to be a ‘passport to success’ in the dominant culture (compare Freire & Macedo 1987).

Even in the face of the undisputed need for access to the dominant culture through English, Aboriginal people talk of reviving languages by returning to how the old people passed on the knowledge and the languages, on country and through the spoken word. Many of today’s Elders were taught in that way. As they got older they became more concerned about the loss of their languages. They now want to go back to teaching how they learned.

This is intuitive to Aboriginal people but is actually an articulation of academic research on language acquisition and language learning (compare Newport, Gleitman & Gleitman 1977; Krashen 1981; Chomsky 1986; Richards & Rodgers 1986; Johnson & Newport 1989; Cook 1993; Foster-Cohen 1999). These works inform aspects of what Aboriginal people are observing about both first language(s) acquisition and additional language(s) learning for both children and adults in the Kimberley context.

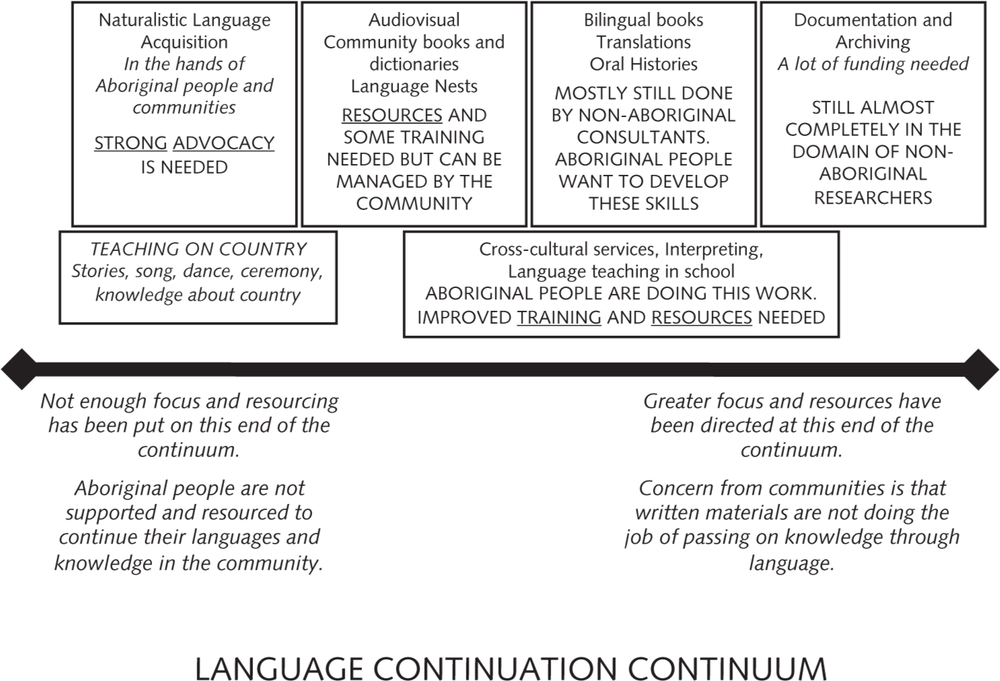

Figure 2. Language Continuation Continuum.

139The KLRC captures the complexity of this situation by referring to Teaching On Country (TOC) and placing that in the context of the Language Continuation Continuum (LCC). The LCC visually sets out the range of possible language continuation activities (Figure 2). Within this context TOC does not just refer to the act of oral language transmission on country as an activity, but captures the unbroken links of knowledge and country to languages. The desire to return to this way of passing on languages reflects feelings of great loss about what is no longer being taught about country and culture. Nettle & Romaine capture this by linking loss of indigenous linguistic diversity to loss of biodiversity (2000, p. 51).

Strategies and projects

In order to support the LCC and TOC the language centre staff is using the following strategies:

- creating greater awareness by increasing metalinguistic and sociolinguistic knowledge among Aboriginal community linguists.8 Through workshops delivered and meetings held we have identified that lack of understanding of the real purpose of linguistic documentation prevented Aboriginal people initiating or supporting appropriate community-level continuation strategies. We also identified that despite the intuitive understanding of language nests and the need to teach primarily through the spoken word, Aboriginal people are not aware that there is evidence to back this up in international research on how humans acquire their first language(s) and how humans best learn or are taught second language(s).

- empowering Aboriginal community linguists to develop and manage projects. Often the type of projects Aboriginal people want to carry out are based on the principles of TOC, but accessing sustainable funding for what is essentially the maintenance of a cultural lifestyle is pretty near impossible. By empowering Aboriginal groups to argue for cultural and linguistic diversity alongside the Western culture, they can lobby government and the private sector to resource a sustainable lifestyle with sustainable employment, for example NRM, interpreting, education, community development and childcare.

- directing funding towards community management of continuation strategies. This improves administrative transparency for the community, and decision-making is centred there.

Some recent projects and activities supporting these strategies are:

- workshops skilling people to use documentation materials

- community dictionaries

- community accessible materials development from ethno-biological resources

- collaborative development of a communication and consultation strategy with a government department

- audiovisual training for communities to document languages

- an adult education short course incorporating classroom teaching with existing resources and oral immersion activities on country

- mentoring in pre-school language acquisition methods, for example with childcare groups

- promotion of an holistic curriculum model for integrating languages and cultural knowledge with the Western Australian curriculum areas

- development of an early years oral curriculum

140Most of this work is achieved without direct project funding. Attempts to gain increased operational funding for additional staff members to support this work are consistently unsuccessful.

Refocusing the worldview

One of the main concerns of Aboriginal people in the Kimberley is the separation of languages from country.

Meek (2007) identifies how the contexts in which indigenous languages are spoken can be changed by a shift of perspective which separates the social use of language from what begins to be thought of as the traditional cultural uses of language. The younger generations begin to see indigenous languages as belonging to the Elders and not as part of their own lives.

In the Kimberley the belief that documentation materials and school programs can take the place of natural language acquisition has possibly been a trigger for the separation of languages from country and consequently daily life. Documentation work with older language speakers was sending a message that the languages belonged to the Elders in very specific contexts. The Elders meanwhile wanted English to become a target language for the younger generations. However many older speakers use a pidgin or dialect of Kriol, which they believe to be a type of English, even on country. Thus children acquire neither traditional languages nor English. In discussions with older generations about getting back to country we often ask the question about their choice of language(s). One answer is that children have to have English for school. The other answer is that children do not understand the languages. Much of our awareness-raising in the community talks about how languages can live beside each other. Traditional languages can be spoken in the community context as well as on country. Doing so will ensure the children can understand.

Another recent trigger for the distancing of languages from social use is the national spotlight on improving conditions for Aboriginal people, which the current Australian government refers to as ‘closing the gap’. There is a strong focus on the English language as a means of improving Aboriginal social conditions through employment, 141education and training. The more this message is pushed, the less people believe their own linguistic heritage can be part of the solution for their children (compare Ball & Pence 2006, p. 115) and so Aboriginal languages run the risk of dying out completely.

Self-determination in language continuation: who sets the agenda?

The story to this point says that the KLRC’s present strategic direction has a foundation in what Kimberley Aboriginal people want for their languages. The issue for the organisation is that we now operate with a different model of revival and maintenance to funding bodies, academic institutions and Western language teaching models.

There are opponents of what the organisation is doing. Disputing the wisdom of the KLRC’s community capacity building focus a linguist stated, ‘I believe that it is one of the roles of the KLRC is to turn scientific studies into materials for use in the community. There are many languages in the Kimberley and the KLRC needs to employ well more than a dozen linguists’ (pers. comm., 20 March 2006). Another linguist observed that Aboriginal people in the Kimberley are being let down because documentation is not being encouraged (pers. comm., 19 March 2007).

Such views inform government. If the board and membership have set a different agenda for preserving their languages, what evidence is there that their chosen method of language continuation will not work? There is plenty of academic research that suggests that it will work. If Aboriginal people believe it will, then that also overcomes another concern of one of the linguists quoted above about lack of interest from young Aboriginal people in Western linguistic study. Caffrey concludes that even for Aboriginal people who have undertaken linguistic studies ‘formal linguistic training has made limited contribution to the documentation and maintenance of Australia’s Indigenous languages to date’ (2008, p. 236).

The concern the KLRC Board of Directors wants addressed is the lack of recognition of the role Aboriginal people not only want to but have to play in the continuation of their own languages.

This concern can be explored by asking two further questions:

Whose responsbility is language continuation at the community level and why does the answer, the community, pose a problem for the KLRC?

We must apply an ecological bottom-up approach to language maintenance … Action needs to begin at the most local level in two senses. First, most of the work will have to be done primarily by small groups themselves … Second, it is necessary to concentrate on the home front (i.e. intergenerational transmission) … Without transmission, there can be no long-term maintenance. (Nettle and Romaine 2000, p. 177)

The direct effect of placing responsibility for language continuation within the community is that, if the KLRC does not meet the government criteria for a regional language organisation, we will not be operationally resourced. This means not 142having the staffing to fill out funding submissions, advocate for the issues, promote the organisation and pursue fee-for-service income. To become sustainable and independent of government, and so fulfil the Aboriginal agenda set by the membership and board, we need in the first instance to be adequately funded operationally. The organisation can then more effectively assist the communities with their bottom-up strategies for language continuation.

Aboriginal activist Noel Pearson (2007) talks passionately about the importance of Aboriginal languages to the reconciliation process and the need to make space at the community level for language continuation. However he also argues for the documentation model of funding:

There needs to be a generous government funded campaign for the maintenance of each indigenous language employing full-time linguists and other expert staff. Private, not-for-profit and public organisations should work together, but language policy and adequate funding must be provided by the national government.

If language activists and academics continue to fight to resource documentation and school programs but do not also argue for linguistic and cultural diversity to be resourced at the community level, the KLRC will be forced to return to the previous model of language continuation to survive. Since this model did not achieve spoken language revival at the community level, this is potentially a huge loss to the Kimberley and the nation as a whole.

Why are Aboriginal continuation strategies seen as less valid than the strategies of Western academia and education?

In societies across the world since ancient times, the quest for knowledge has been elevated to a high-level discipline, even an art form. In Yolŋu society, knowledge has always been considered valuable – almost more valuable than life itself … So why don’t Yolŋu learn … Could it be that the dominant culture education delivered to Yolŋu is so ineffective that almost no education occurs, and Yolŋu are left thinking that the age of knowledge and thinking is at an end? (Trudgeon 2000 pp. 121–22)

There can be no comparison between the transmission of knowledge within literate and oral cultures, but comparison is still sought.

When Aboriginal people express their beliefs on language acquisition in a way that can be conceptually understood by non-Aboriginal people, there may emerge ideas such as language nests which can be understood and accepted by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people.

What about when Aboriginal people are expressing something that cannot be interpreted into the Western worldview so easily, such as the need to protect country and spiritual and social health and wellbeing through continued connection to languages? Does lack of understanding or disagreement on the part of the 143non-Aboriginal person make Aboriginal decisions about languages wrong? Are non-Aboriginal people in the Kimberley asked to explain in such an exposing manner what their cultural background is, why they speak and think the way they do, and then argue for why they should be allowed to continue speaking their language and living their cultural lifestyle?

There is a lot written about us and the question is how do we get a balance between what others are writing about us and what we think and mean about ourselves? How do we have control and direct the knowledge about us? (Kimberley Land Council & Waringarri Resource Centre 1991 p. 39)

Conclusion

One of the many criticisms that gets levelled at indigenous intellectuals or activists is that Western education precludes us from writing or speaking from a ‘real’ and authentic indigenous position. Of course, those who do speak from a more ‘traditional’ indigenous point of view are criticized because they do not make sense (speak English, what!). Or, our talk is reduced to some ‘nativist’ discourse, dismissed by colleagues in the academy as naive, contradictory and illogical. (Smith 1999, p. 14)

The KLRC acknowledges the importance of the documentation work done on languages of the region, through the organisation and by independent researchers. It also acknowledges the contribution of both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people to sustaining language programs. Both strategies provide resources to support language continuation. They do not, however, result in significantly increased spoken language use or continuation of cultural knowledge through languages.

The KLRC is arguing to get the voices of Kimberley Aboriginal people heard despite top-down government policies and a continued academic approach to language continuation. It is imperative for the languages of the Kimberley that these voices are understood. If the KLRC struggles to get their message heard and consequently cannot do the work it is being asked to do by Aboriginal people, we have to ask not only ‘whose languages?’, but also, ‘whose language centre is it anyway?’

Among Aboriginal people, to know my world is to speak my language … I didn’t speak English until I went to school. By learning the English language I learned how to deal with the non-Aboriginal world. Now that we can both speak the same language, we would like to ask you to sit down with us, so that we can start talking and listening to one another. (Ivan Kurijinpi McPhee cited in Kimberley Land Council 1998, p. 26)

Acknowledgments

The KLRC would like to acknowledge Newry & Palmer’s (2003) paper, ‘Whose Language is it Anyway?’ in reference to the title of this paper.144

References

Abley M (2003). Spoken here: travels among threatened languages. London: William Heinemann.

Ball J & Pence A (2006). Supporting indigenous children’s development: community-university partnerships. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Brennan G (1979). The need for interpreting and translation services for Australian Aboriginals, with special reference to the Northern Territory – a research report. Canberra: Department of Aboriginal Affairs.

Caffrey J (2008). Linguistics training in Indigenous adult education and its effects on endangered languages. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Charles Darwin University, Northern Territory.

Chomsky N (1986). Knowledge of language. New York: Praeger.

Cook V (1993). Linguistics and second language acquisition. London: Macmillan.

Foster-Cohen SH (1999). An introduction to child language acquisition. London: Longman.

Freire P & Macedo D (1987). Reading the word and the world. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Hudson J & McConvell P (1985). Keeping language strong (long version). Broome: Kimberley Language Resource Centre.

Johnson J & Newport M (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning: the influence of the maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognitive Psychology, 21: 60–99.

Kimberley Development Commission (February 2009). Population structure & characteristics [Online]. Available: www.kdc.wa.gov.au/kimberley/tk_demo.asp [Accessed 26 March 2009].

Kimberley Land Council & Waringarri Resource Centre (1991). The Crocodile Hole report. Broome: Kimberley Land Council.

Kimberley Land Council (1998). The Kimberley: our place our future: Conference report. Broome: Kimberley Land Council.

Kimberley Language Resource Centre (1993). Plan for language groups that have less than 50–100 speakers. Unpublished manuscript.

Kimberley Language Resource Centre (1995). A policy for research work at the KLRC. Unpublished manuscript.

Kimberley Language Resource Centre (2000). Strategic plan. Unpublished manuscript.

Kimberley Language Resource Centre (2005). Strategic plan. Unpublished manuscript.

Kimberley Language Resource Centre (2008). Business plan 2008–11. Unpublished manuscript.

Krashen S (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. London: Pergamon. 145

Meek B (2007). Respecting the language of elders: ideological shift and linguistic discontinuity in a northern Athapascan community. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 17(1): 23–43.

McConvell P (1986). Aboriginal language programmes and language maintenance in the Kimberley. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics. Series S, 3: 108–22.

Nettle D & Romaine S (2000). Vanishing voices: the extinction of the world’s languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Newport E, Gleitman L & Gleitman H (1977). Mother I’d rather do it myself: some effects and non-effects of maternal speech style. In C Snow & C Ferguson (Eds). Talking to children: language input and acquisition (pp. 109–49). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Newry D & Palmer K (2003). Whose language is it anyway? rights to restrict access to endangered languages: a north-east Kimberley example. In J Blythe & R McKenna Brown (Eds). Maintaining the links: language, identity and the land (pp. 101–06). Proceedings of the 7th Foundation for Endangered Languages Conference. Broome, Western Australia, 22–24 September. Bath: Foundation for Endangered Language.

Pearson N (2007). Native tongues imperilled. The Australian [Online]. Available: www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/

0,20867,21352767-7583,00.html [Accessed 27 March 2009].

Richards JC & Rodgers TS (1996). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith LT (1999). Decolonizing methodologies. London: Zed Books.

Trudgeon R (2000). Why warriors lie down and die. Darwin: Aboriginal Resource and Development Services Inc.

United Nations (1989). Convention on the rights of the child [Online]. Available: www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/k2crc.htm [Accessed 19 May 2009].

1 This paper has been written in standard English by a non-Aboriginal staff member who has worked for the organisation since February 2002, with advice and guidance from Aboriginal colleagues and the 2008–10 Board of Directors. Historical and other information about the organisation is based on project reports and administrative paperwork, for example meeting minutes, government reporting documents, staff reports, strategic and business plans. Verbal and anecdotal evidence which has been documented and email communications are also used. The views set out in this paper are not the views of one person but of Aboriginal peoples from a wide range of language and personal backgrounds. It is the goal of this paper that these views will be listened to respectfully within academic and government contexts.

2 The Board of Directors was previously the Executive Committee. Reference to board and directors refers to both past and present governance.

3 The KLRC uses the term language continuation to refer to all strategies language groups in the Kimberley are using to keep their languages alive. The goal of any strategy is to have languages spoken into the future in whatever way is appropriate for a group or community. This term avoids others such as revitalisation, reclamation and maintenance. Categorising a language’s vitality can limit the type of language activity proposed. For example, for a language with one remaining fluent speaker documentation is argued to be a priority to preserve the language whereas language nests can be equally appropriate for the community to wake up the language.

4 The present board was elected in December 2008.

5 Language nests, a language transmission model developed by the Māori in New Zealand

6 This position has since been retitled manager.

7 Article 30 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child states, ‘In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities or persons of indigenous origin exist, a child belonging to such a minority or who is indigenous shall not be denied the right, in community with other members of his or her group, to enjoy his or her own culture, to profess and practise his or her own religion, or to use his or her own language’ (United Nations, 1989).

8 The KLRC uses community linguist to refer to Aboriginal people who become involved in language continuation in a variety of ways. It does not refer specifically to linguistic documentation work.