XII

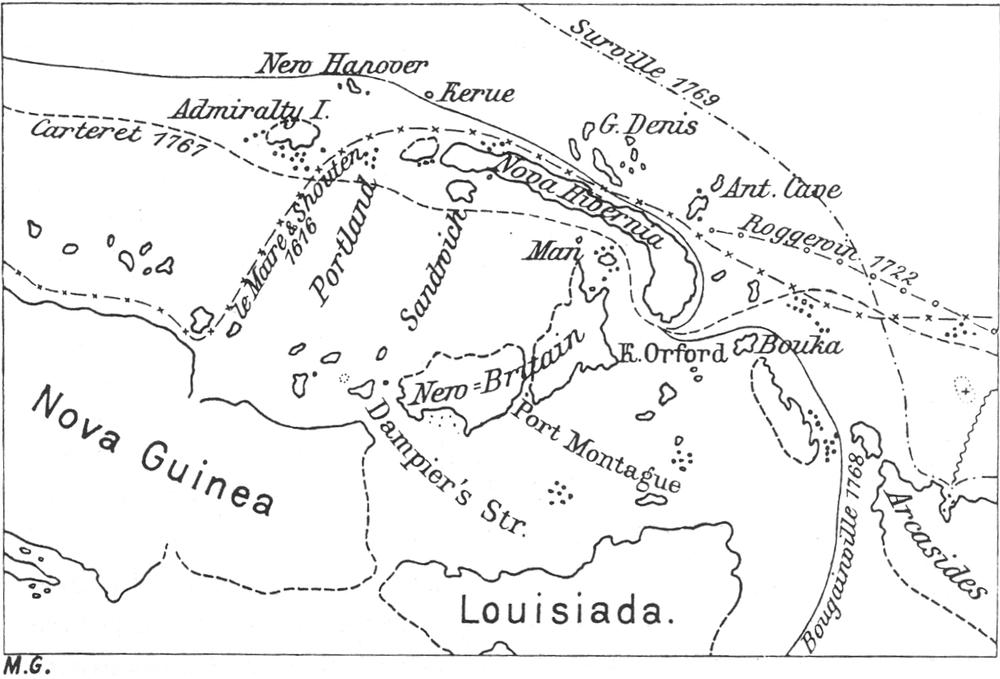

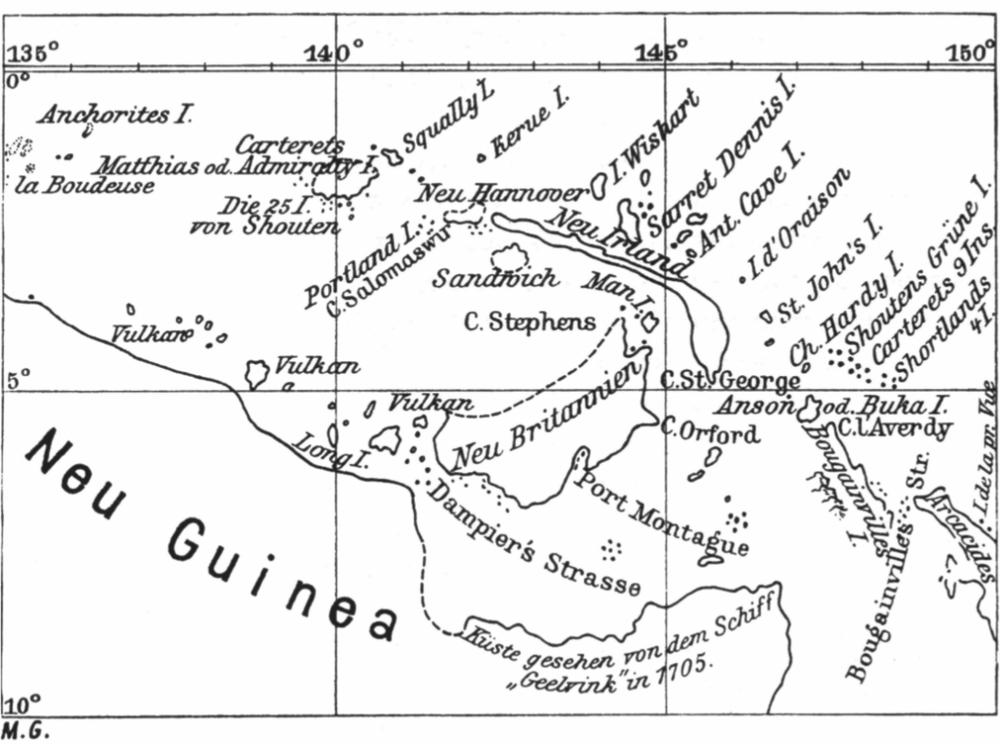

History of Discovery

Knowledge of the initial discovery of the Bismarck Archipelago by whites is wrapped in mysterious darkness for us.

The voyages that were undertaken on the Pacific Ocean shortly after the beginning of the 16th century were most probably not the first of this kind. Even before the birth of Christ, Babylonians and Shebans were trading with Lanka (Ceylon), and from there they ventured as far as the Malayan island world and China. In the north-west of Shantung, in Shansi, Shensi and in Honan, according to Chinese translations, the foreigners had permanent trading settlements. They came in ships in the shape of animals, with two large eyes at the bow. They introduced the Babylonian monetary system, weights and measures, all kinds of sorcery and astrology, the twelve signs of the zodiac, and more of the same, into China. About 140 BC the first traders from Tarsus came to China via Alexandria and Eilat at the northern tip of the Red Sea.

At that time, sea voyages went south from Sumatra and Java, past Timor. It is therefore not improbable that many of the intrepid seafarers in their unsuitably constructed vessels and without present-day nautical aids, lost their way, and were washed up in regions that lay beyond the borders of the then-known world. The large island of New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago further to the east were most probably familiar to them, and likewise the coasts of western and northern Australia, although we have no reliable reports. One day, perhaps, it may be possible to draw conclusions on prehistoric immigrations from the collected sagas of the islanders. Many of the characteristic traditions and customs of the present inhabitants might be remnants of an early culture, transplanted into new ground by the original discoverers.

Migrations of people in Europe and Asia destroyed, among other things, trade and communication with the far east. The few accounts that had been brought back by intrepid travellers, bearing the stamp of the miraculous and fabulous, gained attention only in limited circles. The real knowledge of the seafarers and geographers of Greece, Rome and China has never been revealed to us, although classical authors give hints here and there which indicate at least that, many centuries ago, the human mind was already involved with these far-distant regions, whether as a consequence of imaginative speculations or the outcome of universally acknowledged facts.

After Vasco da Gama had rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1497 the door was reopened to maritime discoveries. The courageous, far-sighted seamen of Spain and Portugal, and their successors the Dutch, French and English, whether it be the quest for glory, or for gold and treasure, proceeded to search for distant lands, and luck, accident or calculation must in time have brought to light what was previously hidden.

By 1511, the Portuguese Francisco Serrano had discovered the Moluccas. His friend and countryman, Fernando Magelhaens, after Serrano’s death, endeavoured to persuade the Portuguese administration to outfit an expedition to take possession of the rich islands. Rebuffed by Portugal, he turned to Spain, which agreed to his proposals. Meanwhile, on 25 September 1513, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa had gazed from the heights of Darien on the immense sea that was later given the name, ‘Pacific Ocean’. Magelhaens suspected that, south of the new part of the world discovered by Columbus, a sea passage must lead to the Pacific Ocean, and thereby to the Moluccas. Subsequent events showed that his assumptions were correct. Sailing through the Magelhaens Strait he traversed the Pacific Ocean between 28 November 1520 and 6 March 1521, and it is probable that it was on this voyage that he sighted the high land of ‘New Guinea’ (that is, the high mountain range on the island of New Ireland), which at that time, and for many years after, was regarded as part of New Guinea.

Alvaro de Saavedra, who, in 1527, sailed from New Spain across the Pacific Ocean to the Moluccas, again discovered what was then called New Guinea, and anchored on the coast for a whole month.

In 1529, after long struggles, the Spanish had relinquished to Portugal their claims on the 350Moluccas, and not until 1540 did they resume their voyages from New Spain through the Pacific; this time with a view to settling the Philippines, discovered by Magelhaens. These undertakings, about which only brief accounts are available, encountered great difficulties. From Mexico it was, of course, easy to lay a course to the west, with help from the equatorial current and the east trade wind, whereas the return voyage along the same route, against wind and ocean current, caused numerous adversities. On these voyages the east coast of present-day New Ireland was not only sighted but also visited, because Abel Tasman asserts that on the old Spanish sea charts of that period he had seen the ‘Cabo de Santa Maria’ and the adjacent coast, the eastern tip of the present New Ireland.

Finally, in 1565 Andres Urdeneta succeeded in finding a route across the Pacific Ocean from west to east at about the 40˚ North latitude; he took 130 days for the crossing to Acapulco. Thus, the route across the ocean was laid down for seafarers for a long time to come.

The great aim of the Spanish had been achieved. The Moluccas, the Philippines, and the rest of the East Indian Spice Islands could be reached on a route across the Pacific, and linked to the motherland. All the other parts of the ocean not lying on the sea route north of the equator, remained ignored. In actual fact, it appears to have been the policy of the Spanish administration, very early on, to impede all further exploration of the Pacific Ocean. On the American continent, Spain was in possession of an immense empire that was already difficult enough to administer; the gold and silver mines of this empire offered a seemingly neverdiminishing source of wealth, and neither greed nor ambition drove them to take possession of new unknown regions. The Portuguese also had attained their goal in the East Asian Spice Islands, and so it came about that although European settlements on the east coast of Asia and the west coast of America rapidly increased – settlements created as departure points for exploring the unknown Pacific Ocean – all the voyages for a long time passed along a definitively prescribed sea route, which was unfavourable for making new discoveries.

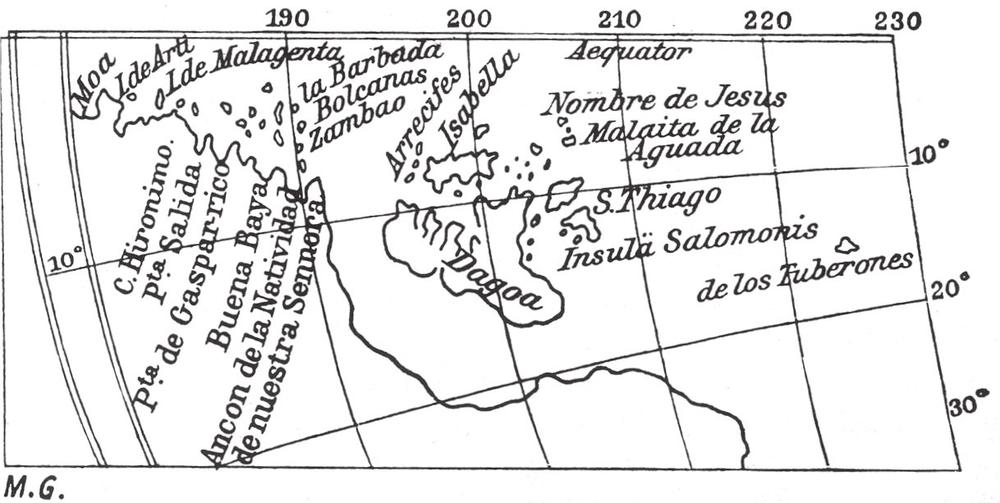

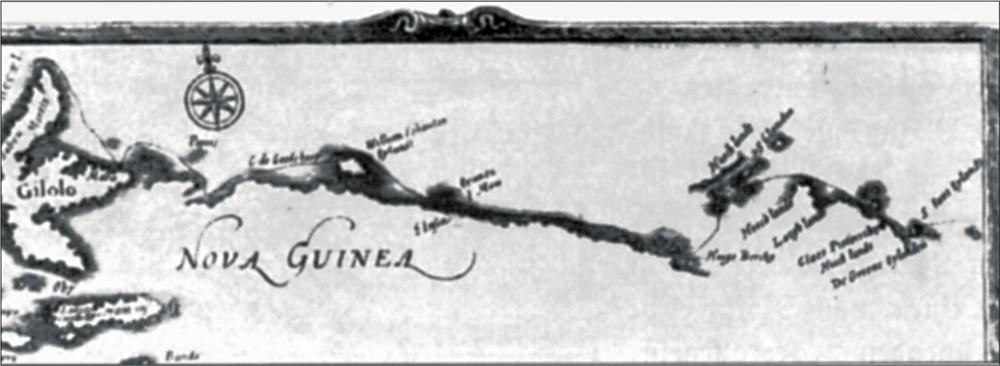

Fig. 126 Fragment of a map of the western hemisphere, by Th. de Bry (1596)

The viceroys in New Spain, however, conducted politics in their own right, and not always in accordance with the government in their homeland. They were besieged by adventurers of all ranks, whose ambition and greed had not been satisfied in the New World, and who for their part were pressing on to new undertakings that would lead to the fame and fortune of the participants. For these people the great southern land, the Terra Australis incognita designated on all the maps of the time, was the goal of all their efforts. Public opinion populated this unknown land with fabulous beings and immeasurable riches, although nobody could state exactly where this wonderful land was.

The Terra Australis incognita of the old cartographers is undoubtedly based on an inaccurate knowledge of present-day Australia, but it was given total reality in consequence of a theory of the learned geographers of that time, according to which, corresponding with the land masses of the northern hemisphere, there had to be an opposing land mass in the southern hemisphere, to maintain equilibrium with the former. In an old 10th-century manuscript by Macrobius there is a map on which the unknown southern land is already depicted. In later centuries it takes on more definite form, and on one map, dated 1536, now in the British Museum, it is called ‘Java la Grande’. On all maps from the same century, particularly on the maps of the French, whose geographers played a leading role at that time, we find not only the coasts of western and northern Australia, but also the islands lying to the north. The English and Dutch geographers, on the other hand, tried to connect facts with the theory at the same time.

At the court of the viceroys, the impetus became stronger year by year. The magnificent southern land could, in everyone’s opinion, not be too far away, and in 1566 the viceroy of the time, Lope Garcia de Castro, outfitted two ships to find the unknown southern land. Overall command was given to Alvaro Mendaña de Neyra, with Hernando Gallego assigned as navigator. Both ships, Almirante and Capitano, left Callao on 19 November 1566, and returned to Peru on 19 June 1568. During the voyage, on 1 February 1567, a group of islands was discovered. This was named ‘Los Bajos de la Candelaria’ (the earlier German Ongtong Java Islands or Lord Howe group). Sailing south from there, on 9 February the two ships anchored off the coast of an island that Mendaña named after his wife, Isabel (previously German, transferred to England a few years ago). Mendaña was thus the discoverer of the Solomon Islands, which he regarded as a part of the southern land. In 1896, the German warship Möwe named the cape first sighted by the expedition not far from their first anchorage, Cape Gallego, in honour of the original discoverer. 351

Mendaña was so convinced of the wealth of the land discovered by him that he pushed for a repeat of the expedition; but he achieved this goal only as an old man. However, on this second voyage, in 1595, he was not able to locate his earlier discovery; in the end, he reached the southerly situated Santa Cruz Islands, like his later follower, Pedro Fernandez de Quiros, who discovered the northern New Hebrides. Torres, Quiros’s second-in-command, brings us back once more to the neighbourhood of the German South Seas possessions when, after separating from the commander-in-chief, he sailed westwards and discovered the strait between Australia and New Guinea that today bears his name. This significant discovery was kept secret by the Spanish, and only when the English occupied Manila in 1762 was Torres’s report found there in the archives. Likewise, Mendaña’s first journals were kept secret, and the later reporters, Herrera and Figueroa, gave such an incomplete and inaccurate account that the geographers of the time located the Solomon Islands too far to the east and then too far west, and later seafarers who actually sighted the groups were of the opinion that they had discovered new, hitherto unknown island groups. The French geographers Buache in 1781, and Fleurieu in 1790, established finally that the islands discovered by the English and the French at the end of the 18th century were identical to Mendaña’s Solomon Islands.

Mendaña’s discoveries have no significance for our German Solomon Islands of Buka and Bougainville – they were discovered about 200 years later. However, I have not been able to avoid the geographers’ dispute over Mendaña’s discovery because, as we shall see later, it strongly influenced the cartography of the Bismarck Archipelago.

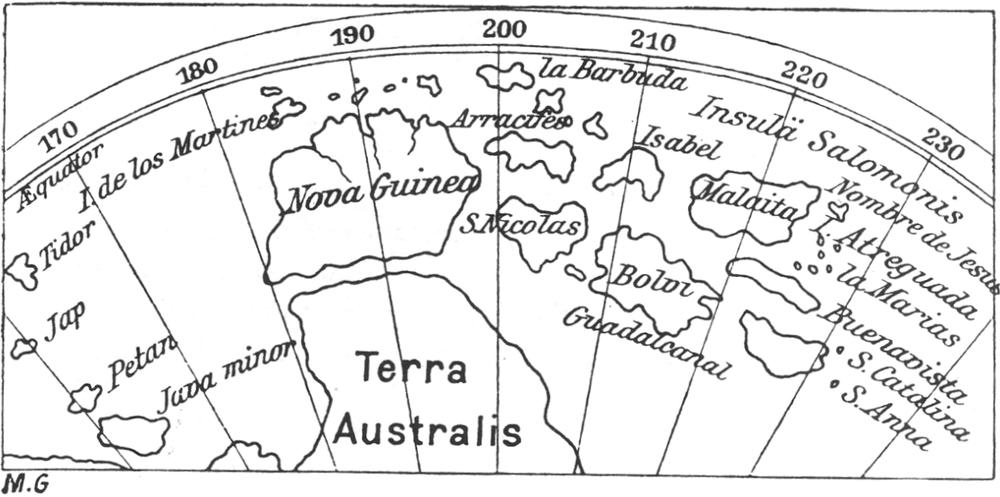

Fig. 127 Part of a map by Witfliet (1597)

With the beginning of the 17th century we see the power and influence of Spain already on the wane. The Netherlands had shaken off the Spanish yoke, and quickly decided that, if the trading of the hated papists could be hurt, there would be a possibility of winning back the Netherlands’s southern provinces. Geography and hydrography were the subject of ongoing research, and, in Peter Plancius’s nautical school in Amsterdam, they systematically studied how the Spanish and Portuguese possessions could be usurped. Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, who had spent fourteen years in the Portuguese territories and absorbed a wide knowledge, published his observations in Amsterdam in 1618, and fired up his countrymen even further with his accounts.

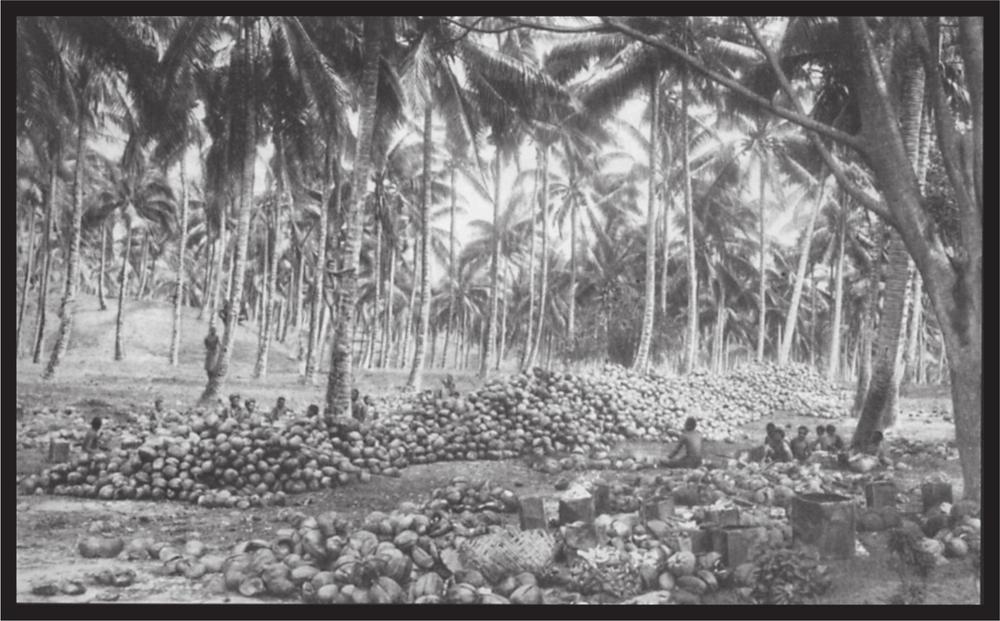

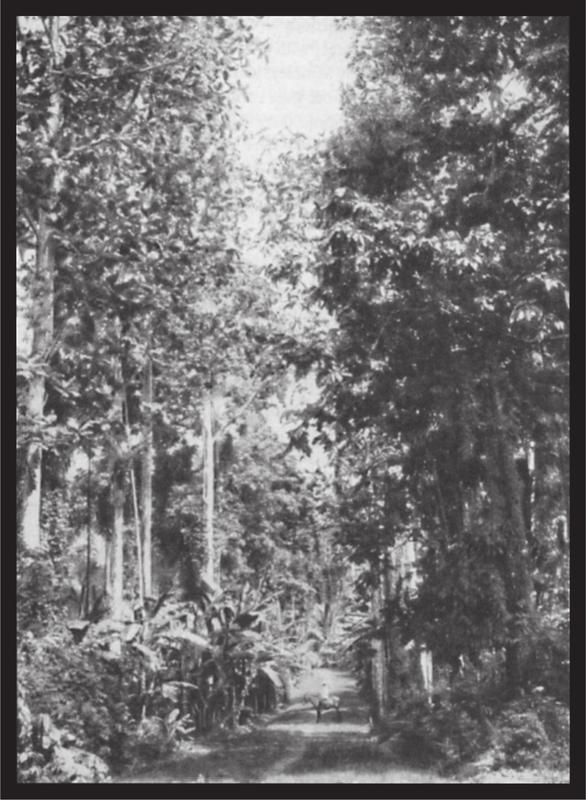

Plate 52 Coconut plantation at Ralum

352In 1602, the Dutch East India Company had been founded, and its ships were soon sailing to seize the trade with Batavia, Bantam, Amboina, Banda and other places. However, at home opposition soon stirred against the company, which sought to monopolise all commerce, and, out of indignation against the rude allegations, Willem Corneliszoon Schouten and Jacob Le Maire fitted out the ships De Eendracht and Hoorn in which they embarked on their voyage in 1616.

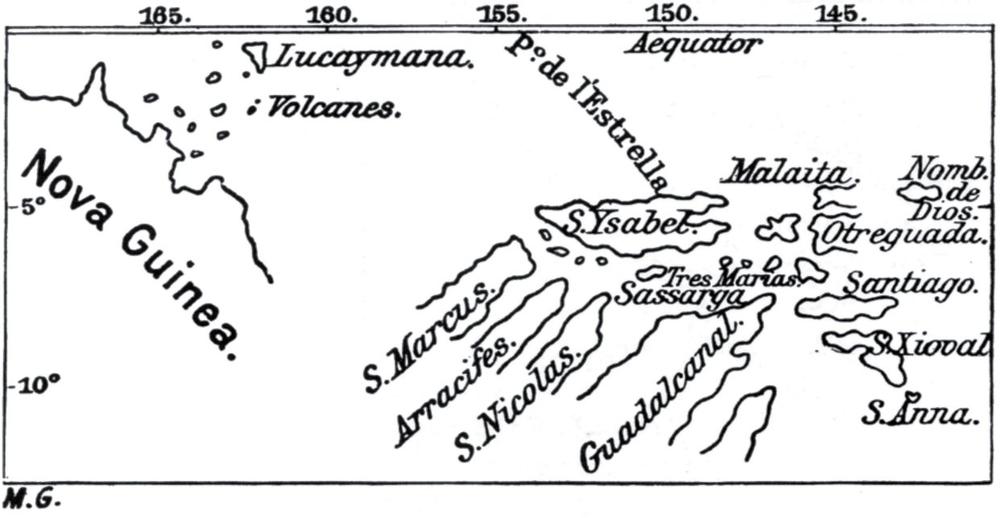

Fig. 128 (top) Part of a map by Herrera (1601)

Fig. 129 (above) Schouten and Le Maire’s map

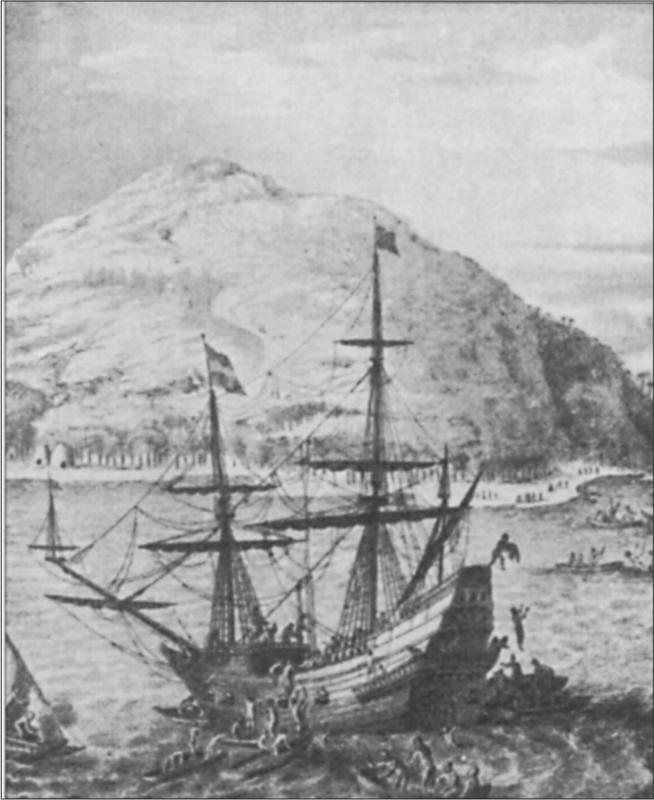

This voyage by the two Dutchmen is of significance to our South Sea possessions, since after they had rounded Cape Horn and sailed through the southern tropical zone they sighted low-lying land on 20 June, and sailed close inshore on 21 June. There were three or four small wooded islands with a coral reef stretching to the north-west. Two canoes came alongside, and both Schouten and Le Maire recorded that here, for the first time in the South Seas, they noticed bows and arrows in the hands of the natives. In the evening of the 22nd, they again sighted a number of small low-lying islands, which they named the Marken Islands.

Fig. 130 De Eendracht, Schouten and Le Maire’s ship. After an old copperplate engraving.

On 24 June they sighted three low-lying islands in the south-west that seemed to be covered in trees; two of them were about 2 miles long, while the third was small. The coasts were steep and without any anchorage. This group was named the ‘Groene Islanden’ (the Sir Charles Hardy Islands or Nissan on the current charts). Sailing on, they discovered two further islands that we designate today as ‘Green Islands’ (Pinepil and Esau). Due to the onset of darkness they did not venture closer to these islands.

Meanwhile, west-a-quarter-north-west a high mountainous island had come into view ahead, and during the night they traversed the island-free gap, which according to Le Maire’s statements was 15 miles (60 nautical miles). The high island was named ‘Sankt Jan’ from the calendar saint of that day.

On the morning of the 25th, they sighted very high land. St John was no longer visible, and they sailed towards the high land that conformed to the then-known profile of the north-eastern tip of New Guinea. We know today that the coastline encountered was the current New Ireland, in the vicinity of Cape Santa Maria.

The wind before and after was east-south-east and they were able to sail close inshore along the coast, but did not find an anchorage. The boats launched to pilot them were attacked by canoes of natives with slingshot stones, and the following day, the 26th, the ships were attacked so that firearms had to be used. Ten of the attackers were killed and three captured, while four canoes were seized and destroyed. Two of the prisoners were released on payment of a ransom, consisting of a pig and a bundle of bananas. The journal adds: ‘They did not seem to be worth more.’ The following day a pig was traded for several iron nails and other trinkets, thereby paving the way for peaceful contact, for on the 28th a beautiful large canoe came alongside with twenty-one natives who marvelled tremendously at the ship. They brought lime and betel, but made no offer to ransom the third prisoner, who was then released.

Only a few years ago, some 250 years later, quite similar events could have been played out on that same coast.

Sailing on, they discovered the offshore islands. However, they did not recognise the insular character of the current New Hanover; they also 353skirted east of the Admiralty Islands, which they designated as ‘Hooch Landt’. Schouten designated the small islands offshore from the eastern end and the southern coast as ‘Fünfundzwanzig Inseln’, whereas contemporary charts frequently give them as ‘Islas de la Magdalena’, probably from accounts of earlier Spanish seafarers.

From here the enterprising seafarers directed their course to the coast of New Guinea, and during the subsequent voyage they did not come into contact with any further islands of the archipelago.

We are again indebted to the Dutch for further exploration of the archipelago. In 1642 the then Dutch governor of the East Indian possession, Anton van Diemen, fitted out two ships to look for the unknown southern land.

The expedition vessels consisted of the yacht Heemskerk, the flagship, and the Zeehaen. The former had a crew of sixty, and the latter fifty, the best seamen that could be recruited at that time in Batavia. Provisioning was reckoned on twelve to eighteen months.

Abel Jansz Tasman was the commander-in-chief; the commander of the Heemskerk was the master mariner Yde T’Jercxzoon Holman, or Holleman, from Jever in the present archduchy of Oldenburg. The Zeehaen was commanded by Gerrit Janszoon of Leiden, and Isaak Gilsemans, the probable draughtsman of the expedition, was on the same ship, as auxiliary. Aboard the Heemskerk, Abraham Coomans acted as Tasman’s secretary. These people, together with the two first mates, formed the ‘grand council’ of the expedition, with Tasman as chairman. The first mate of the Zeehaen was Hendrik Pieterson, while on the Heemskerk, and with the title of ‘pilot-major’ it was Franz Jacobszoon Visscher from Vlissingen, a seafarer who had already made numerous important voyages in the service of the company.

Of the crew, the following are known by name: on the Heemskerk, Crijn Hendrikszoon de Ratte or de Radde from Middelburg, and Carsten Jurriaenszoon; the gunnery officer, Eldert Luytiens; the head carpenter, Pieter Jakobszoon, and his assistant, Jan Joppen; the quartermaster, Jan Pieterszoon, from Meldorf; and seaman Joris Claesen. On the Zeehaen were the second mates, Peter Duijts and Cornelius Roobol; the boatswain, Cornelius Joppen; seamen Pieterszoon from Copenhagen, Jan Tijssen, Tobias Pieterszoon from Delft, Jan Isbrandtszoon, and the ship’s boy Gerrit Gerritszoon. The ships’ surgeon, Hendrik Haalbos, was probably on the Heemskerk.

Although Tasman as an explorer cannot be placed alongside the great Spaniards and the Portuguese of the preceding century, nor the great Englishmen of the following century, he is nevertheless the most prominent personality in this field in the 17th century.

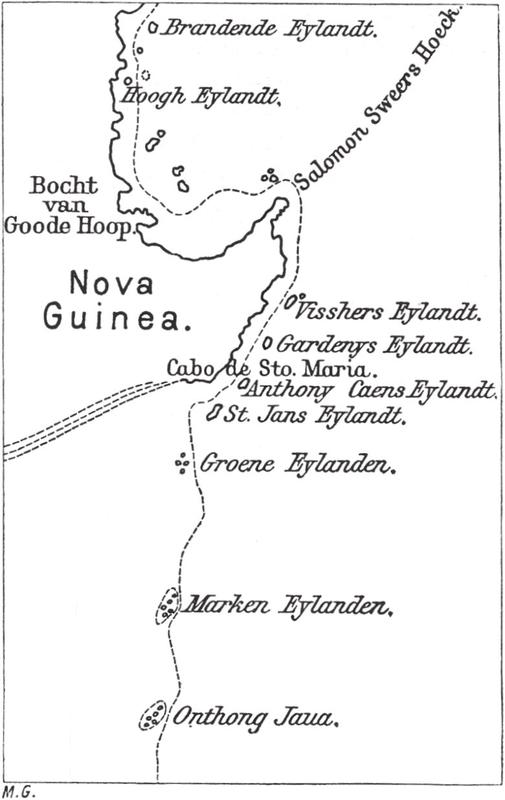

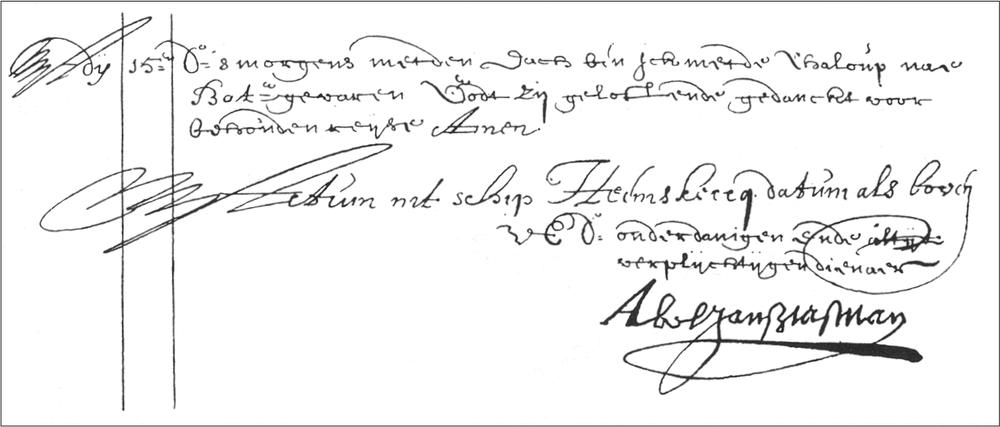

Fig. 131 Tasman’s chart

His original log has apparently been lost; a fair copy bearing Tasman’s personal signature is held in the State Archives in the Hague, and was made available to a wider circle by Frederik Muller & Co. in Amsterdam in 1898, in a splendid display of facsimiles. An extract of this follows, as far as the islands of the Bismarck Archipelago are concerned, and covers the period from 22 March until 14 April 1643:

22 March: At noon we spied land ahead, about 4 miles off; in order to pass to the north of it, we steered firstly west by north and then west-orth-west. Towards evening we sailed in a north-westerly direction close inshore. These islands are about 30 in number, but are very small, the largest no more than 2 miles long; all the rest are small and are surrounded by a reef. Another reef runs off to the north-west, surmounted by three coconut palms, which make it easy to see. These are the islands that Le Maire had indicated on his chart; they are about 90 miles from the coast of New Guinea. In the evening we saw land to the north-north-west.1 We therefore set our course north-north-east, on the wind, to sail north of all the shallows, furled our foresails and continued thus until morning.

[Various coast representations follow in the manuscript, with signature.] We named these islands the ‘Inseln von Onthong Jaua’ on account of their great similarity with them; they are surrounded by reefs, and appear in this form when you have them in the south-west about 2 miles from you.

23 March. In the early morning we again made sail, and steered westwards, having the small islands that we had seen the previous day about 3 miles to the

354south. The wind was easterly and north-easterly, with cloud cover and trade-wind weather. At noon our position was latitude 4˚31’, longitude 177˚18’; steered west-north-west, sailed 20 miles. During the night, at the end of the first watch we hove to, because we feared beaching on the island of Marcken, discovered by Le Maire.

24 March. In the morning the sails were set again and we steered westwards. Towards noon we spied land directly ahead; this land was very low-lying, and appeared to be two islands lying south-east and north-west of each other. The northernmost showed several similarities with the island of Marcken in the Zuyder Zee, as Le Maire says, for which reason he gave it the name Marcken. Noon observation gave 4˚55’ latitude and 175˚30’ longitude; kept a westerly course as far as we could estimate. We find, however, that a strong current is pushing us southward; we sailed 20 miles with an easterly and east-south-easterly wind and trade-wind weather with a light topsail breeze. In the evening we altered our course to the north, to pass north of the island. During the night we drifted becalmed, and closed on the forementioned island.

[The following page has a coastal representation with signature.] The island appears like this when it is west from you at a distance of 2 miles; Le Maire named the island Maercken because of its great similarity with this island.

25 March. In the morning watch we heard the sound of breakers on the beach; as it was still totally calm, the pinnace and the sea boat were launched to haul us free of the reef or shallows. However, sea and tide drove us a distance towards the reef. To our great chagrin, we found no anchorage. About 9 o’clock a canoe from the island came alongside, carrying seven people and about twenty coconuts. We traded a dozen of these for three strings of beads and four medium-sized nails; the coconuts appear to have grown wild, and were of poor quality. The people seemed rough and wild, with a darker skin than those of the islands where we had taken recreation. They were also less well-mannered, and were totally naked except for an apparently cotton cover of their sexual organs, scarcely big enough to conceal them. Several had short hair while others wore it bound up like the rascals in Murderers’ Bay.2 One of them wore two feathers on his head, like horns; another had a ring through his nose, although we could not establish what it was made of. Their canoe tapered sharply fore and aft like the wings of a seagull although not elegant in shape and in poor condition; they had arrows and two bows, and seemed to have no esteem for either beads or nails, nor to value them at all. Then the wind came from the south and fortunately helped us to get away from the reef. The canoe was paddled back to the beach. We saw a small canoe approaching, but it did not reach us because of a suddenly arising squall. A northerly course was then laid, to bring us out of the area of reef and shallows. The islands are about fifteen to sixteen in number, the largest being about a mile long while the rest seemed like houses. They all lay together, surrounded by one reef. The reef runs north-west from the islands; about a cannon-shot from the islands a grove of trees stands level with the water. Two miles further north-west is another small island, like a toppershoetje (a small seaman’s hat). The reef stretches a further half mile to sea, so that in total it runs about 3 miles north-west from the islands. The noon position was 4˚34’S latitude and 175˚10’E longitude. Course north-west, sailed 7 miles. Towards noon the wind shifted to the north-west and then north. We altered course to the west, upon which the wind was from the north-north-east, and a gentle breeze sprang up, which altered our course to the north-west. During the night, with calm weather and a northerly wind we ran somewhat more to the west.

26 March. Fine weather and a calm sea with a light north-easterly breeze. Noon observation was 4˚33’ latitude and 174˚30’ longitude; westerly course, sailed 10 miles. We encountered a strong current going to the south, and we again set our course north-west. Variation 9˚30’ north-east.

27 March. Wind and weather as before. Noon observation 4˚1’ latitude, 173˚36’ longitude; course north-west by west, sailed 16 miles; at noon steered westwards to look for the islands lying east of the New Guinea coast, and then to reconnoitre the mainland coast by sailing close inshore. Variation 9˚30’ north-east.

28 March. Continuing fine weather; light easterly breeze and calm sea. Noon observation 4˚11’ latitude, 172˚32’ longitude; course west; sailed 16 miles. Towards noon we sighted land ahead, and at noon were still about 4 miles from it. This island lies at 4˚30’ S latitude and 172˚16’ longitude. It is 46 miles west and west by north of the island that Jakob Le Maire named Marken. At night we drifted in calm.

[Here the text has a sketch of the coast of the Green Islands with the comment:] Le Maire named these islands the ‘Groene Eylanden’ because they seemed beautiful and green; their form is as shown here when the east end is to the south and the west end to the south-west, from about 2 miles away.

29 March. In the morning we observed that the current was carrying us towards the island. Noon observation, 4˚20’ latitude, 172˚17’ longitude. Throughout the day we drifted in calm, so that in the last 24 hours we had travelled 5 miles south-west. In the middle of the afternoon two small vessels from the island came alongside; they had two wings

355or outriggers. Their paddles were small with thick blades; they seemed poorly made to us. One of the canoes carried six people; the other, three. When they were about two ship-lengths away, one of the six men in the one canoe broke one of his arrows, stuck one half in his hair and held the other in his hand, apparently indicating his friendship. These people were completely naked, and their bodies were black with crinkly hair like the Kaffirs, but not quite so woolly as the latter, nor were their noses quite so flat. Several wore white armbands, apparently made from bone, round their arms; others had smeared their faces with lime, and wore a piece of tree bark, about three fingers wide, on their foreheads. They had nothing but bows, arrows and spears. We called out several words from the vocabulary of the New Guinea language; however, they seemed to recognise only the word lamas, meaning ‘coconut’. They pointed continually towards land. We gave them two strings of beads and two large nails, as well as an old tablecloth, in exchange for which they gave us an old coconut, the only thing that they had with them, then they paddled back to shore. Towards evening it was still calm, with a very slight breeze from the north-east; we sailed close inshore and had to launch our boats to keep us off the beach. At the end of the dogwatch we succeeded in escaping the island. There were two large islands and three small ones, the latter lying on the western side. Le Maire had named these islands the ‘Groene Eylanden’ (Green Islands). In the west-north-west we saw a further high island and two to three small ones; also, in the west we noticed very high land that appeared to be a continental coast; but only time will tell the truth of this opinion. Variation 9˚ north‑east.

[At this point the text contains a coastal view of the island of St John, with the following note:] A view of Sankt Jans Eylandt when it is about 2 miles distant to the north.

30 March. Fine weather with a light breeze from the north-east; still engaged with towing; we found that the current was taking us south. Noon observation 4˚25’ latitude, 172˚ longitude; course west; sailed or drifted 4 miles. In the evening St John’s Island was 6 miles to the north-west.

31 March. Continuing good calm weather, with an easterly wind and calm sea. Noon observation 4˚28’ latitude, 171˚42’ longitude; course west; sailed 6 miles; at noon we hoisted the white flag and pennant, at which our friends on the Zeehaen came aboard and we have decided with them what can be seen more fully in today’s resolution.

1 April AD 1643. We had the coast of New Guinea alongside at 4˚30’S latitude, at a place that the Spanish call ‘Cabo Santa Maria’. Noon observation 4˚30’ latitude and 171˚2’ longitude; westerly course, sailed 10 miles. Variation 8˚45’.

2 April. Continuing good calm weather with variable breeze. We did our best to sail along the shore, which here extends north-west and south-east of St John’s Island. North-west is another island, which we named Anthony Caens Island.3 The island lies directly north of Cabo de Santa Maria. Noon observation 4˚9’ latitude and 170˚41’ longitude; course north-west, sailed 10 miles; we then had Cabo de Santa Maria to the south, which fixes it at 171˚2’ longitude. In the evening we ran under the shore so that we could make better progress with the land breeze. At four bells of the first watch we obtained a light land breeze and made our course along the shore.

[The subsequent four pages contain coastal views with the notes:]

View of the coast of Noua Guinea when sailing along it; this land is named ‘Cabo de Santa Maria’

View of the coast of Noua Guinea between Cabo de Santa Maria and Anthony Caens Eylandt.

View of Anthony Caens Eylandt when it lies to the north.

View of ‘Gerrit de Nijs Eylandt’4 lying two miles to the north.

View of ‘Visschers Eylanden’ 4 miles to the east.

View of the coast of Noua Guinea when sailing along it between Gerrit denys Eylandt and Visschers Eylandt.

3 April. In the morning we felt another slight land breeze; our course was still north-west along the shore. About 9 o’clock we saw a fully manned vessel coming from the shore; the vessel was curved at both ends like a corre-corre from Ternate. It lay quietly for a while beyond the range of our big ordnance, then paddled back to shore. Noon observation 3˚42’ latitude, 170˚20’ longitude; course north-west; sailed 10 miles. Towards evening a light breeze arose from the east-south-east. We continued north-west along the coast. This seemed to be very fine land; however, the worst was that we did not find an anchorage anywhere. During the night we had thunderstorms with rain and variable breeze.

4 April. We continued to sail along the coast, which here extends north-west by west and south-east by east. It is a fine coast with many inlets. We passed an island about 12 miles from Anthony Caens; both lie on a line north-west and south-east from each other. We named this island Garde Neijs. Noon at 3˚22’ latitude and 169˚50’ longitude; course north-west by west; sailed 9 miles; continuing variable light winds and calm. In the evening we had a land wind with thunder, and did our best to sail along the coast.

Fig. 132 Heemskerk and Zeehaen, Tasman’s two ships. From an old copperplate engraving

5 April. In the morning we still had a light land wind. Towards noon we reached another island about 10 miles from Gardenys in a line west-north-west and east-south-east from each other. On the beach of this island we saw several canoes that were probably used for fishing, which was why we named this island Visschers Eilandt (Fisher Island). Towards noon we observed six vessels ahead, three of which paddled so close to our ship that we were able to drop two or three pieces of old sailcloth, two strings of beads and two old nails down to them. They did not seem to notice the sailcloth, and also barely noticed the other items. However, they pointed constantly to their heads, from which we gathered that they wanted turbans. These people seemed to be very shy, and judging from their behaviour were fearful of being shot; they did not come close enough for us to ascertain whether they were armed. They were very black, and totally naked apart from a few leaves covering their genitals. Several had black hair, others had hair of another shade. Their canoes had outriggers, and each held three or four people, but, because of the distance, it was not possible to discover further features. After they had paddled around the ship for a long time, they paddled to the beach, calling out to us, while we responded, although neither understood the other. Noon at 3˚ latitude and 169˚17’ longitude. Course west-north-west, sailed 10 miles; in the afternoon we had a light north-west wind.

Fig. 133 Natives of New Ireland. From a drawing in Tasman’s log

6 April. In the morning there was no wind. In the middle of the forenoon we again observed eight or nine canoes coming from the same island; three paddled to the Zeehaen and five to our ship. Several held three people, others four, and one five people. When they were about two stones’ throws away, they stopped paddling and called to us; we did not understand them but we beckoned them closer. At this, they paddled in front of the ship and loitered there for a long time, without coming alongside. Finally the boatswain took off his belt and held it out to them, whereupon one of the canoes came alongside. We gave them a string of beads, and the boatswain handed his belt over to them, in exchange for which we received only a piece of pith of a sago palm, the only thing that they had with them. Meanwhile, the other canoes had come alongside, as they saw that their friends had suffered no injury. None of the canoes contained weapons or anything they could have used to fight us. At first we had our suspicions that they were rascals who were plotting evil and looking for plunder, because they affected such great apprehension. Had our suspicions been well-founded they would have been warmly received, because we had already prepared measures necessary to repel them, although the cook had not yet prepared breakfast. We called out the words anieuw, oufi, pouacka, and so on (coconuts, yams, pigs, and so on), to them, which they appeared to understand, because they pointed towards the shore, as if they wanted to say, ‘There they are’. Then, with one accord, they paddled swiftly back to the beach, as the wind had grown stronger; we did not see them again. These natives are dark brown, almost as black as Kaffirs; their hair has various shades depending on whether or not they have powdered it with lime; their faces are smeared with red dye except for their foreheads. Several wore a thick bone, the size of a little finger, through the nose. Otherwise they wore nothing on their bodies, except for several green leaves over their genitals. Their canoes were new, and neatly constructed, decorated fore and aft with carvings, and fitted with an outrigger; their paddles were neither very long nor broad, and tapered at the end. Towards noon the wind turned south-east, and we made our course west by north along the shore; observed latitude 2˚53’, longitude 168˚59’; course west-north-west, sailed 5 miles; during the afternoon we made good progress. During the night we had a light offshore breeze.

[The next three pages contain views of the New Guinea coast, with the comments:]

View of the coast of Noua Guinea, when sailing westwards from ‘Visshers Island’.

View of the coast of Noua Guinea up to this bight.

View of the coast of Noua Guinea or ‘Salmon Sweers hoeck’5.

View of a canoe of Noua Guinea, with local

357natives (fig. 133).

7 April. In the morning we drifted without wind. Before noon twenty canoes came back, and remained in the vicinity of the ship, but outside cannon range, as on the previous day. After repeatedly making signs to them, they finally ventured alongside. They had nothing in their vessels, although one contained three coconuts, one of which we traded for a string of beads. Our thought was to get all three but they firmly refused to hand over the other two. Another had a shark, which we similarly traded for three strings of beads; a third had a dolphin, which one of our sailors traded for an old cap. Several had small fish that they threw to our people, but they were not worth eating. Eventually three or four of the people came aboard, looking at everything with great astonishment and walking round as though they were drunk – a peculiar characteristic, since in their small canoes they paddle for many miles out to sea without the slightest sign of seasickness, but on a big ship like ours they seem to be struck with dizziness from the movement brought about by ocean swells. They had neither weapons nor objects with which they could have attacked us. They appeared to feed themselves from fishing, as several carried eel spears (fishing spears). After they had spent some time on board, they left us and, with great commotion, paddled hastily to shore. We lay here during the afternoon, drifting in a calm. Further westward, the land becomes very low-lying, but the coast still stretches, unbroken, west by north and west-north-west. At noon we estimated 2˚35’ latitude and 168˚25’ longitude; course west by north; sailed 9 miles. In the afternoon we saw more high land west by north, and west of the previously mentioned point; and estimated that this land was about 10 miles away. We drifted becalmed, but soon found a light easterly wind and tried to approach the high land. The current along this coast is steadily in our favour, so that we proceed further westwards every day as we evidently advance over the water. We passed a large inlet during the night.

8 April. In the morning we reached the western side of the bight and four small low-lying islands. When we had passed these, we again reached three small islands, lying west of those that we had passed at noon. At noon we estimated 2˚26’ latitude, 167˚39’ longitude; the wind was south-east but variable; course west by north, sailed 12 miles; variation 10˚ north-east. South-west by west we had a low cape with two small islands to its north. From this cape the land begins to run gradually southwards. Towards 6 o’clock in the evening we had the two small islands to the south by west, and the next land visible, very low and flat, lay south-west by south, about 4 miles away. During the entire time we steered our course along the coast.

9 April. At sunrise in the morning we drifted becalmed; the land sighted in the south lay southeast by east, about 2.5 miles away, where the coast suddenly dropped away. We then had another low island to the south-south-west, about 2 miles away. Although we did our best to sail closely along the point in question, we were prevented by lack of wind. At noon, 2˚33’ latitude, 167˚4’ longitude; course west-south-west; sailed 7 miles, variation 10˚. In the afternoon we again steered towards the point.

10 April. During the last 24 hours we have made good progress southwards. As a result of the calm and for other reasons, we attempted to go southwards as fast as possible, partly to explore the coast, partly to find a southern passage. At noon the southernmost point was east-north-east, and the northernmost north-north-east. At noon 3˚2’ latitude, 167˚4’ longitude; course southerly, sailed 12 miles. In the afternoon sailed further south; towards evening the wind became north-northwest. To come close in under the land a course was set east-south-east and south-east, and occasionally south; variable winds with rain bothered us a lot. But after midnight we again drifted becalmed on a smooth sea.

11 April. At noon we drifted becalmed, without being in a position to take a sighting. We still observed land before us to the north-east, i.e. the easternmost point; the westernmost point lay north-north-east and north by east ahead of us. At noon, 3˚28’ latitude and 166˚51’ longitude; course south-west by west half a point west, sailed 7 miles. In the second watch a light breeze from the north-north-east; altered course to south-east, close on the wind, but later it became calm again.

12 April. At three bells in the morning watch we felt such a strong earthquake that none of our crew, even though fast asleep, remained in his hammock; they all came on deck instantly with the greatest astonishment, in the belief that the ship had run onto a rock. It was just as if the keel had slid over a coral reef, but when we took soundings we found no bottom. There were further earthquake shocks later, but none as powerful as the first; initially we had calm weather, then heavy rain later; wind variable and occasionally still. We attempted to push as far south as possible. Towards 3 o’clock in the afternoon we had a light westerly wind. At noon, 3˚45’ latitude and 167˚1’ longitude; course south-south-east; sailed 6 miles. Then we sailed south-south-east and observed a small, round, low island in the south and west, about 4.5 to 5 miles away. Heavy rain and changeable weather at night.

[The three subsequent pages contain coastal views of New Guinea and Vulcan Island with the annotations:]

View of the coast of Noua Guinea in the large bight where we hoped to find a passage through to Cape Keerweer, but were deceived.

358 View of Nova Guinea in the large bight close to the reef.

View of the coast of Nova Guinea, when sailing westwards between the coast and the volcanic island.

View of the volcanic island in the north-east.

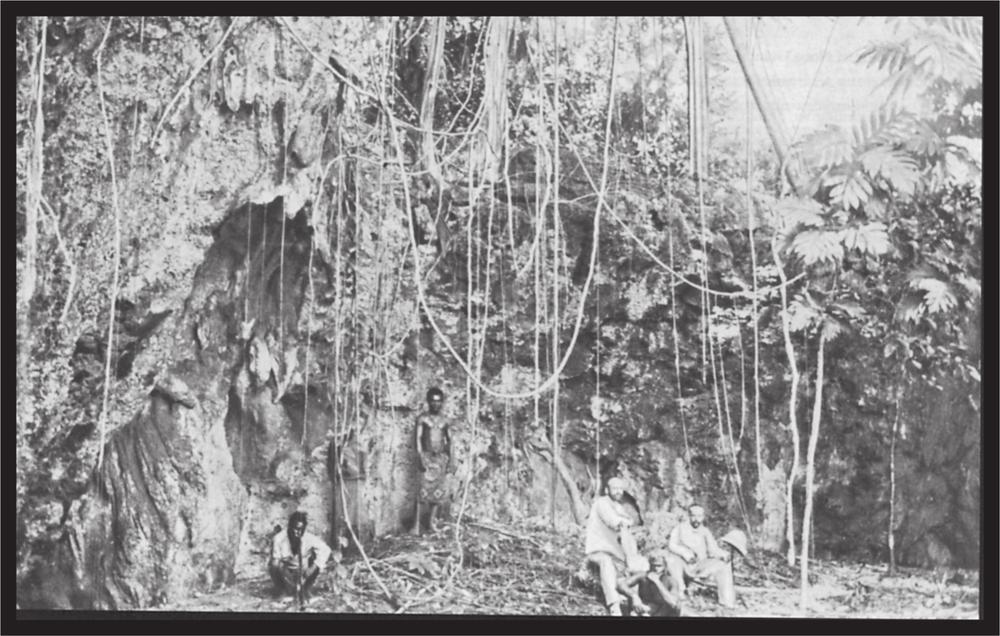

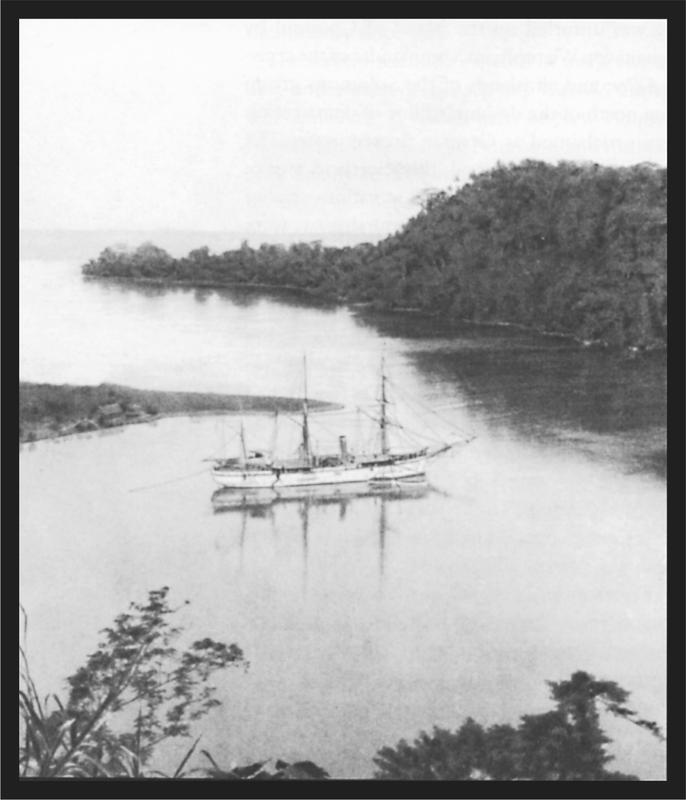

Plate 53 Grotto in raised coral rock on Mioko

13 April. In the morning a light north-easterly wind; observed high land with several mountains and low land between, from south-west by west to east-south-east. We appear to have found ourselves in a large bight. We did our best to go as far south as possible. At noon, 4˚22’ latitude, 167˚18’ longitude; course south-south-east, sailed 10 miles. Drifted in calm during the afternoon, without being able to strike bottom; the sea here is as calm as a river, without any movement, which makes us believe even more that we have found ourselves in a large bay; we will find the real situation with time. At night variable wind with occasional calm. In the evening a distinct mountain range to the south-south-west, towards which we set our course.

Fig. 134 Facsimile of Tasman’s log with his personal signature

14 April. In the evening we saw land from east-north east to south-south-west, and later in the west-south-west. We hoped, but in vain, to find a passage through; however, as we came closer, we found that it was a bight, and that the land was continuous to the south. Therefore in the afternoon we directed our course to west by south with a north-north-west wind, and between 3 and 4 o’clock in the afternoon we found a reef which lay right on the surface of the sea, and which we could scarcely pass, with the prevailing wind. The reef in question lies about 2 miles from the shore, as far as we could estimate. At noon, 5˚27’ latitude, 166˚57’ longitude; course south-south-west, sailed 15 miles; variation 9˚15’ north-east. Towards evening light wind from the north-north-east. At night, again drifted in calm.

I end the extract from Tasman’s journal here, because from this point on it has no connection with the Bismarck Archipelago. However, if we follow his course, we observe that if on the 14 April he had succeeded in penetrating further south-west, then on this day or, with the same course, on the 15th at least, he would have discovered the straits between New Guinea and New Britain. Seen from the area where he was on the 14th, western New Britain, Rook Island and New Guinea appear to form a connected land mass.

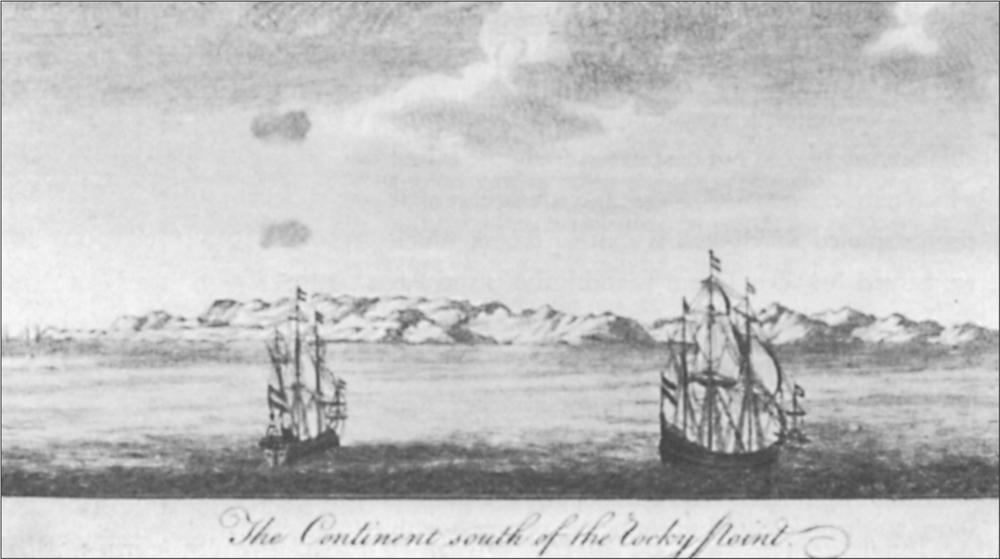

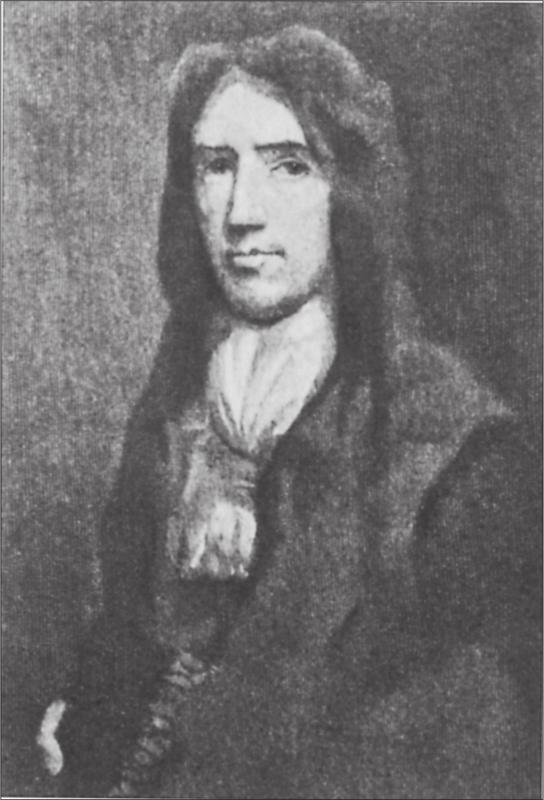

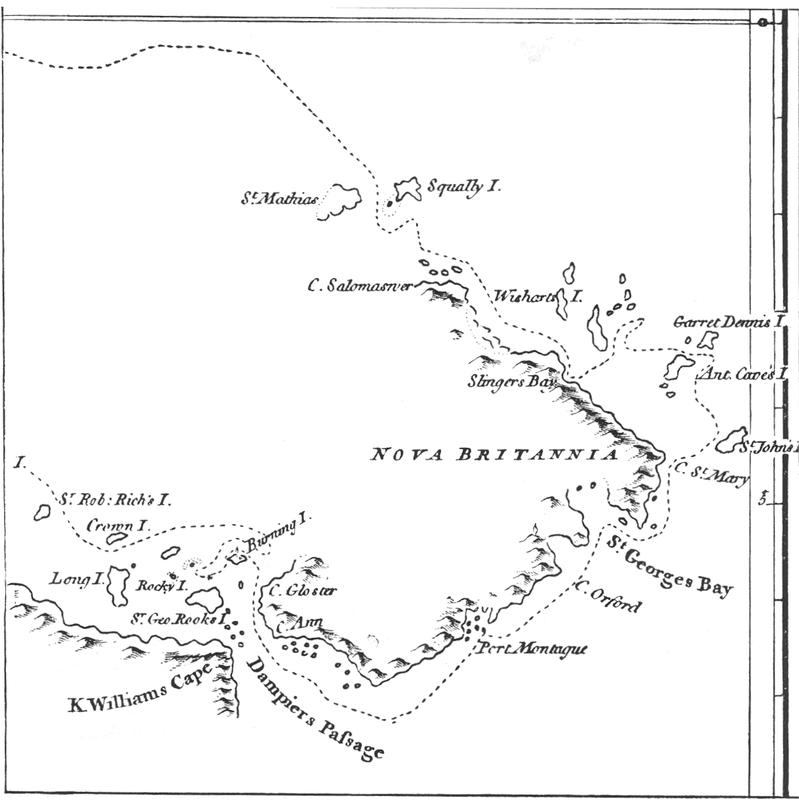

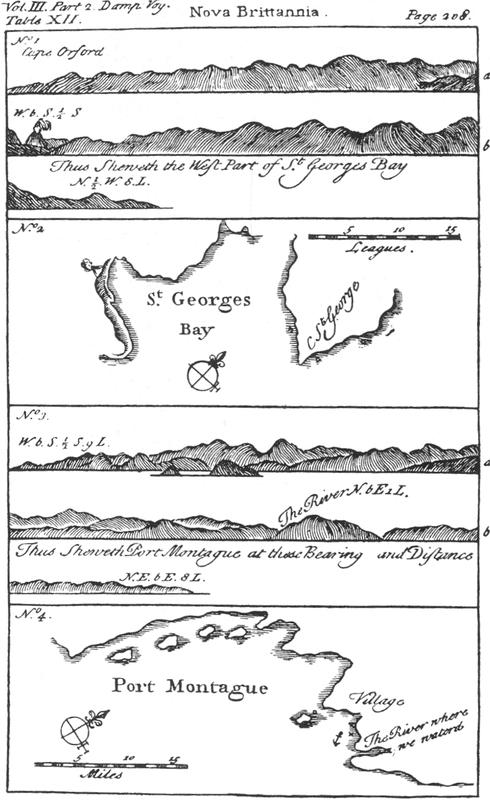

A long pause in discoveries set in, right up until 359the end of the century. English, Dutch, French, Spanish and Portuguese were heavily occupied in siphoning off the treasures won in the East Indies and America from one another on the journey home. A form of official piracy, that promised easy pickings, flourished widely, and nobody found time for further exploration. Not until the end of the century did the desire for discovery reawaken, this time in England where the intrepid seafarer William Dampier drew attention by the publication of his adventures in America and the East Indies. The Earl of Oxford, at that time Lord of the Admiralty, was introduced to the well-travelled man, and finally appointed him commander of a South Seas expedition. On 26 January 1699, Dampier left the English coast in the ship Roebuck; we find him again on the west coast of Australia, which he had already visited once before. From here he turned towards Timor, and then steered eastwards between latitudes 2˚and 2.5˚S. About the 149th meridian he steered south, thereby avoiding the ‘Hooch Landt’ of Schouten and Le Maire. However, on 16 February 1700 he encountered St Matthias, and then sailed between this island and Squally Island to the present New Hanover. On his map he indicated a portion of the small islands off the north coast of New Hanover, but he came as little as did his predecessor to the conclusion that New Hanover was an independent island.

From then on he steered a course along the coast, but somewhere between the present Gardner Island and Gerrit Denys Island he came into conflict with the natives, who attacked his ship with slingshots from their canoes. Dampier named the spot Slinger’s Bay, and preferred to put further out to sea. He touched the small offshore islands, and approached the coast again only in the vicinity of Cape Santa Maria. Moving further south he discovered and named Cape St George, and after he had sailed round it he anchored in a fairly large bight stretching northwards; he named it St George’s Bay. In the northern corner of the bay he observed huge clouds of smoke rising from a crater (volcano on the Mother peninsula). According to his map he must also have noticed the present Neulauenburg islands, since in the inner northern corner of his St George’s Bay two small islands are shown in the location of that group.

Thus, William Dampier is the first European documented as having anchored in the Bismarck Archipelago.

Had Dampier arrived at another time of the year, say July, then wind and current would probably have driven him into the so-called St George’s Bay, and he would have made the discovery that remained reserved to his later successor, Carteret, that this was a strait. However, he navigated the coasts of the present-day Neumecklenburg and Neupommern from 16 February until April, and, during this period, a strong current sets out of his assumed bay, due to the prevailing north-west wind. When Dampier left his anchorage, both a favourable wind and a favourable tide carried him along the south coast of New Britain. In Montague Bay, which he named, Dampier again came into contact with natives, of whom he gives a description that is still relevant today. However, he did not stop here but sailed along the coast until he found the Dampier Strait, named after him, between a smaller island that he named Sir George Rook’s Island, and the large main island, that he gave the name of Nova Britannia. His further course led him along the coast of New Guinea and, if we look at his chart we can recognise without difficulty the Ritter, Tupinier, Heyn, Lottin, Long and Crown islands. Thus, Dampier became the discoverer of the Bismarck Archipelago which, up until then, had been regarded as a part of the large island of New Guinea.

Fig. 135 William Dampier. From an old engraving

Fig. 136 Dampier’s map

360It is interesting that on his special chart of St George’s Bay, and on his depiction of the western shore, Dampier shows a then-active volcano. The position of the volcano is approximately correct, although it has currently been extinct for a long time. It was probably extinct even during the time of Carteret, who does not mention it, even though, during his long stay at the southern end of New Ireland, he would certainly have noticed the volcano opposite, had it been active at that time.

Fig. 137 Facsimile of Dampier’s coastal survey of New Britain

Once more, twenty-two years pass before a seafarer approaches the archipelago. In 1722 the Dutchman Jacob Roggeveen sighted the island of Nova Britannia, which he named Neu Zeeland. However, his voyage brings nothing new. On board Roggeveen’s squadron as a sergeant of marines was a German named Karl Friedrich Behrens, a native of Mecklenburg. Behrens published his experiences of the voyage in Leipzig in 1738. He honoured his fatherland by calculating his longitude east and west of the meridian of his homeland, which is somewhat confusing to the reader.

Forty-five years later, in 1767, the Bismarck Archipelago emerges again out of its darkness, to be enriched again by a significant discovery. Between 1764 and 1766 the English administration had despatched the first of those epoch-making voyages of discovery into the South Seas, under Captain Byron, soon followed by the voyage of Captain Wallis and the three voyages of the famous James Cook.

All of these voyages, as well as the almost simultaneous expeditions of the French – Bougainville, Surville, La Perouse and D’Entrecasteaux – supplement our knowledge of the Pacific Ocean, and the current German possessions were also at that time further explored.

First of all, the expedition under Captain Wallis is significant to us. He was in charge of two ships, the frigate Dolphin and the much smaller vessel Swallow which was commanded by Lieutenant Philipp Carteret, who had previously been a member of the Byron expedition in 1764-65.

The Swallow was a so-called ‘sloop of war’ of fourteen cannon, with a crew of ninety men and twenty-two deck officers. She was totally unsuitable for the voyage for, as Carteret himself says, ‘she was an old ship, in service for thirty years already and unfit for a longer voyage’. Besides, the outfitting was inadequate, and even the most essential items were missing. It sounds almost laughable when we read today that Carteret’s formal request to the Admiralty to supply a portable forge and iron, a small boat and other small items that, from experience, he knew were essential, was bluntly refused because ‘the fitting-out for the intended purpose is completely satisfactory’. Even rigging was provided only sparingly, and Carteret was overjoyed when he received 5 metric hundredweight of rope from the commander-in-chief during the voyage. It is small wonder, therefore, that the voyage, which lasted from August 1766 until 20 February 1769, was an almost uninterrupted sequence of all manner of difficulties. At the outlet of the Magelhaen Strait, the badly sailing Swallow lost the Dolphin from view (11 April 1767), and the unruffled Carteret decided to continue the voyage alone. Only rarely did he sight land; on 24 August 1767 he spotted the Carteret Islands, named after him. His description matches the present situation remarkably: ‘The inhabitants are black, and woolly haired like the African negroes; their weapons are bows and arrows, and they own large canoes, which they navigate by means of sails.’

Nissan was sighted the following evening, and on the same day high land was discovered to the south. Carteret named it Winchelsea’s Island in his journal, but on his chart he named it Lord Anson’s Island. This is the first report on the northernmost of the Solomon Islands, the island of Buka. On the 26th, St John’s Island was sighted and, shortly 361after, the raised land of Nova Britannia. They rounded Cape St George, and on 27 August wind and tide drove the ship into Dampier’s St George’s Bay. On the 28th their joy was great when they were able to anchor not far off the small Wallis Island. The crew’s condition was demonstrated by the fact that, in spite of the efforts of the entire crew, they were unable to raise the anchor on the 29th; this was achieved only after renewed effort on the 30th. The Swallow was brought closer inshore and beached in the tiny English Cove to careen the hull, badly damaged by ship worm. They stayed here until 7 September, when they sailed several miles north to Carteret Harbour and anchored between a small island with a stand of coconut palms and the main island.

The voyage was continued on 9 September; outside they found strong east-south-east winds and a strong current from the south-east, which drove the Swallow deeper into St George’s Bay, and Carteret discovered that the assumed bay was actually a broad strait, which he named St George’s Channel. In the evening, they discerned the Duke of York Islands (today Neulauenburg) which Carteret, however, designated on his chart as Man Island, and they observed three high mountains, named the ‘Mother and Daughters’. Carteret reports, ‘The Mother is the middle and highest mountain, and behind it we saw giant clouds of smoke.’ (These would be from the not yet totally extinct volcano, which Carteret could not see from his vantage point.) He named the northern point to his left Cape Stephens, and the current Cape Gazelle ‘Cape Palliser’. Not far from Cape Stephens, he discovered another smaller island that he named Man Island; however, he left it unnamed on his chart. Wind and current took him along the coast of the newly discovered large island, which he named Nova Hibernia. On the 12th he sailed between Nova Hibernia and a small island, and gave the latter the name Sandwich Island. During a calm he received a visit from ten canoes with about 150 natives. They were shy and did not venture aboard. Carteret’s description of the canoes and their crew is appropriate word-for-word today. In the continuation of the voyage they discovered the strait between New Ireland and New Hanover, presented for the first time as an island; the strait is named Byron Straits.

Early on the 13th they sighted the small islands already seen by Tasman, now christened Portland Islands, and on the 14th they had the small eastern islands of the Admiralty group in view. On the 15th, numerous canoes and natives came from the islands. They could not be persuaded to go aboard, behaved in a hostile manner, and finally attacked the ship with their spears. Carteret had to use his ordnance to dissuade them from further attacks. Continuing on, they encountered another group of them; they had to be put to flight, and a canoe containing all kinds of weapons and objects was seized. The hostile demeanour of the natives frustrated a detailed investigation of the islands, which he designated with the name they retain today.

In the evening of 18 September they again saw two small islands; one of them could be seen only from the masthead, and it was named Durour Island. They passed the second island during the night, and a lot of natives were seen running along the beach with torches; he named this island Maty Island (‘Matty’ is a later disfigurement).

With this, the Carteret discoveries in the Bismarck Archipelago came to an end.

The French too were busy in the South Seas at the same time as the English.

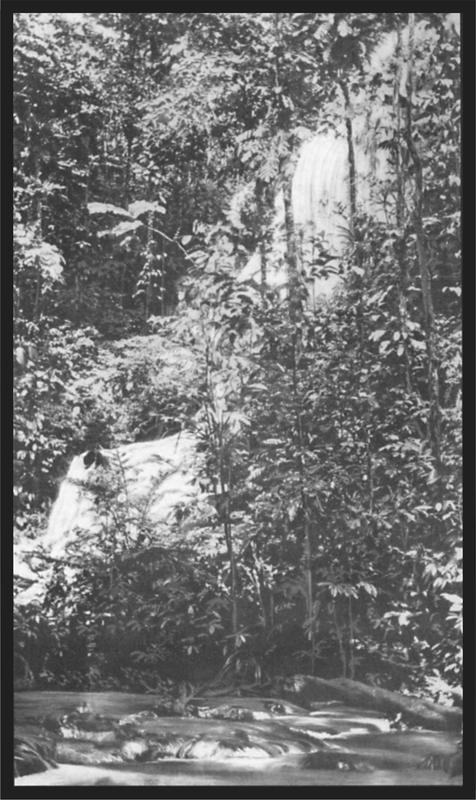

Plate 54 Waterfall in the Karo valley. Baining

On 15 December 1766, Louis Antoine de Bougainville 362put to sea from St Malo with two ships, La Boudeuse and L’Etoile, under orders of the king. After he had discovered the southern border of the Louisiades he sailed north, and on 28 June 1768 he sighted the coast of a long high island to starboard. On the 30th he had come so close to the coast that he attempted to anchor. A boat was launched, which was followed by many heavily manned canoes but was not attacked. However, there appeared to be open sea ahead, and both ships continued their set course. On 1 July the boat was launched again to find an anchorage, and was attacked by ten canoes containing about a hundred natives. The island was named ‘Choiseul’ and the strait they sailed through still bears the name Bougainville.

After passing through the Bougainville Strait, they spied an extensive coast to the west, whose high mountain peaks were hidden in clouds. In the evening of 2 July the northern tip of Choiseul was still visible, but on the morning of the 3rd they saw only the coast of the land discovered the day before, whose height was astonishing. The northern tip of the island was named Cape l’Averdie; while the island itself was named after its discoverer, Bougainville.

Early in the morning of the 4th, they sighted land lying further to the west; the coast was less high, and between the southernmost point of the land and Cape l’Averdie they noticed a wide open stretch which was assumed to be a pass or a broad deep bight. On the far side of the presumed strait, or bight, the peaks of high mountains rose steeply, which led to the conclusion that the land must be an island. I will let Bougainville continue:

In the afternoon three canoes pushed off from shore to reconnoitre our ship; each contained five or six negroes. They stopped just out of range, and only after an hour did our continuous entreaties succeed in bringing them closer. Several trinkets thrown to them, tied to pieces of wood, strengthened their resolve, so that in the end they came alongside and held up a few coconuts, crying ‘Bouka, Bouka, Onellé’ over and over again. After some time we did the same, and this appeared to cause great joy. They did not stay long by the ship but indicated to us that they were going back to shore to collect coconuts. However, these treacherous people had gone scarcely twenty paces away when one of them fired an arrow at us which fortunately did not hit anyone. Then they paddled away as fast as possible, and we despised them too much to think about punishing them.

These negroes were totally naked; they had short woolly hair, their ears were pierced and pulled down and many had their hair dyed red, with various parts of their bodies painted with white patches. To judge from the red stains on their teeth they appeared to chew betel, and we noticed the same in the inhabitants of Choiseul Bay, for, in their canoes, we found small bundles of leaves as well as Areca and lime.

The island, which we named Bouka, seems very well populated, if we can draw a conclusion from the large number of huts and the numerous gardens. A fine plain against a hillside, completely planted out in coconut palms and other trees was a splendid sight to us, and I would have liked to have found an anchorage off the island, but wind and current were perceptably taking us north-west.

They hove-to during the night, but the following morning the island of Buka, which Carteret had named Winchelsea, or Lord Anson, the previous year, was already far to the east and south-east.

In the afternoon of 5 July the high land of New Ireland was discovered and on the 6th they dropped anchor on the western side, not far from the southern tip. The place was christened ‘Baie de Praslin’; the same place that Carteret had named ‘Gower Harbour’ the year before. Here the crew recovered a little, and the journey was then continued along the east coast, since the existence of a strait in the west was then unknown to the French. Bougainville gave new names to the islands already discovered by his predecessors; for example, he changed St John into Bournand, the Caen Islands into ‘Isles d’Oraison’, Gerrit Denys into Bouchaye, Wishart Island into Souzanett, and so on, names that have already long since disappeared from the maps. Sailing on, he sighted Squally Island and St Matthias, and further to the west discovered the Isles des Anachorettes and the Echiquier Islands. His course then led him further along the coast of New Guinea.

In 1781, the Spanish warship Princesa, under Captain Maurelle, fleetingly touched the east coast of New Ireland and the Admiralty Islands and, travelling on, sighted the Hermit Islands.

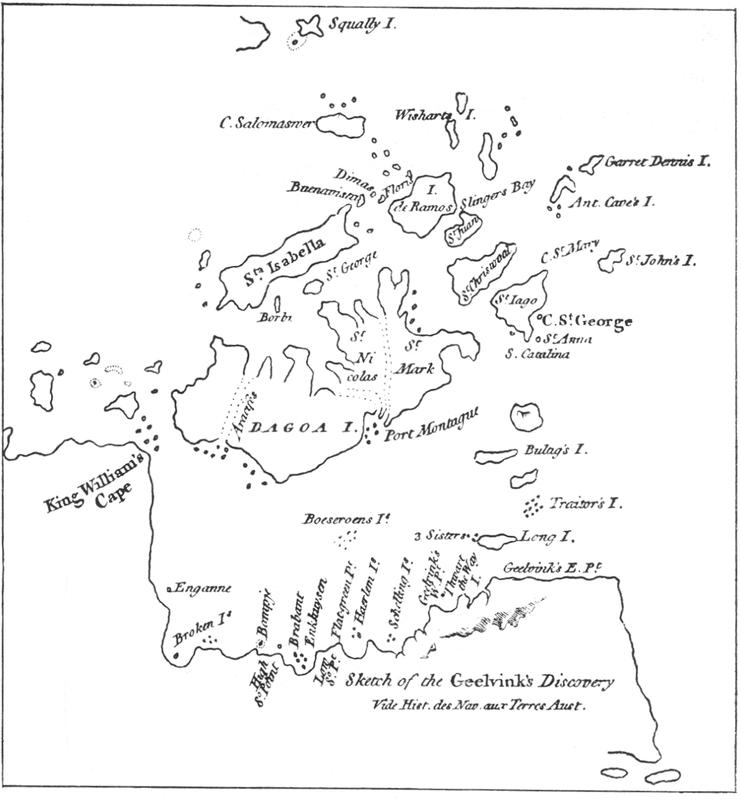

At this time there arose the previously mentioned argument among the geographers about the position of the Solomon Islands. The French asserted the rediscovery of the group by their seafarers, while the English, on the other hand, laid claim to the fame of their people for having discovered new land, and moved the Solomon Islands, the existence of which, however, could not totally be denied, westward, north of New Guinea, where they were attempting to bring the discoveries of Dampier and Carteret into accord with those of Mendaña.

The Englishman Dalrymple was the principal proponent of this theory, and for further clarification, he presented a map in conjunction with his written evidence. The map is reproduced here. On it he ingeniously combined the islands of the present Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon Islands into an island group that of course does not bear the slightest resemblance to the real situation. On the other hand, the French maps of 3631785 and 1790 give the position and shape of the archipelago and the northern Solomon Islands with reasonable accuracy.

A consequence of this argument was the fitting-out of a further French expedition under Count de la Pérouse, which left its homeland in 1785. La Pérouse visited first the west coast of the Americas and the east coast of Asia, and reached Australia in September 1787, whence he began his second great voyage. However, he went missing in February 1788, and, on the order of Ludwig XVI, the two ships Recherche and Espérance, under the command of Bruny D’Entrecasteaux, were sent out in 1791 to search for the missing people. We are grateful to this expedition for valuable contributions to the knowledge of our archipelago.

It must be mentioned here that the English commodore Hunter, whose ship, Sirius, had stranded on Norfolk Island in 1790, and who was travelling with the Dutch ship Waaksamhed from Sydney to Batavia, on 23 May 1791 put into the small harbour, named Port Hunter after him, on the north coast of Duke of York (Neulauenburg) to take on water. He came into conflict with the natives, which was, however, finally settled, and on his departure as a gift Hunter left two English pointers, which were probably eaten immediately as dainty morsels. From Duke of York, Hunter saw huge volcanic eruptions on New Britain, in the present Blanche Bay. On the continuation of the voyage the Waaksamhed passed the Admiralty Islands, and Hunter thought he saw items of French uniforms on the natives. He had met La Pérouse in Australia and knew that he intended to visit these regions.

The Frenchman’s disappearance without trace was still fresh in his mind, and, from a distance, the white body paint of the natives looked like the white uniform facings of the French marines to the commodore, who assumed that La Pérouse had foundered here. Hunter reported this supposition on his arrival in Batavia, from where it was passed on to the French Governor on Ile de France. The latter immediately despatched a frigate to inform D’Entrecasteaux’s expedition in Cape Town. Hunter was in Cape Town at the same time as the two French ships, and it seems strange that not only did he not pass on his observations to the commander, but on the other hand maintained to friends that he knew nothing of the matter.

Fig. 138 Dalrymple’s map

Nonetheless, D’Entrecasteaux went directly from Cape Town to Van Diemen’s Land and, via New Caledonia, to the archipelago to carry out an investigation. They sighted the southern end of Bougainville on 10 July 1792, but heavy rain prevented closer investigation until the 13th. On the 14th the small islands at the north-western end of Bougainville were sighted, and on the 15th they were not far from the northern tip of Buka. Canoes of natives came out to the ship, and their description by the naturalist, Labillardière, who was accompanying the expedition, is as apt as if he were describing them today. The contact with the natives was totally friendly.

Fig. 139 Part of a map put together in 1785 for orientation of the Count de la Pérouse

On the morning of the 16th they passed Nissan, and Cape St George came into view about 1 o’clock. On the 17th they dropped anchor in the tiny Carteret Harbour and stayed there until the 24th without coming into contact with natives. Sailing along the west coast of New Ireland, they found themselves off the small islands between New Ireland and New Hanover on the 26th. Finally, on the 28th they sighted the eastern Admiralty Islands; La Vandola was reached on the 29th 364and they got on peacefully with the islanders, who were, however, very thievish. They navigated the north coast of the main island on the 30th, and on 1 August the group was lost from sight. Contact was friendly everywhere; Labillardière accurately described the natives. However, no trace was found of the missing La Pérouse. Sailing on, they made contact with the inhabitants of the Hermit Islands, and then sailed to New Guinea.

Fig. 140 L.C.D. Fleurieu’s map (1790)

Fig. 141 Admiralty Islanders. After an engraving in D’Entrecasteaux’s account of the voyage

Thus passed the expedition’s first visit to the archipelago. After a voyage among the East Indian islands, along the west coast of Australia, and after visiting a number of new islands, the expedition approached the archipelago a second time, this time along the north coast of New Guinea.

Labillardière writes about this last visit:

At daybreak on 30 June 1793 we discovered, north-west by west, a very high mountain, the flanks of which were furrowed by deep longitudinal valleys. This was Cape King William. Later we sighted the west coast of New Britain and steered towards it under full sail, so as to pass through Dampier Strait before nightfall. Since the sun was in our faces the lookout did not promptly spot a flat with

breakers, which we passed over at about 8 o’clock in the morning. We had believed that we were out of danger when again, three-quarters of an hour later, we found ourselves between two shoals that surrounded us on all sides to such an extent that, with the south-south-east wind driving us further and further in, it seemed impossible to pass through. The commander immediately ordered to go about; time was too short to carry out this manoeuvre and our ship drifted steadily towards the northern shoals ahead of us. Shipwreck seemed inevitable, when suddenly Citizen Giquel yelled from the masthead that he had spotted a passage which, although very narrow, seemed wide enough to allow our ship to pass through. Immediately steering for this pass, we finally got out of one of the most dangerous situations during the course of the expedition. We were, however, still not yet completely out of danger and, surrounded by many shoals, we were frequently obliged to alter course. However, we finally succeeded, luckily, in finding a path through the narrow channels.

Towards noon we had already travelled quite far into Dampier Strait; our latitude was 5˚83’S, our longitude 146˚24’E.

In direction the coast of New Britain ran from east 37˚ south, to east 61˚ north; our distance from land amounted to about 2,500 toises.

The island (Tupinier) on which Dampier had observed a volcano, lay to the west, about 38˚ north, about 7,600 toises away. This volcano was now extinct; however, 5,130 toises distant in the west 28˚ north we saw a small conical island (Ritter Island), which had shown no sign of subterranean fire during Dampier’s time. From time to time, a thick column of smoke rose from the summit of this mountain; about half past three, great masses of fiery material were hurled out of the crater; they covered the eastern side of the mountain in a fiery glow and rolled down the slope until they fell into the sea, causing the water to boil, and white clouds of vapour to rise. At the time of the eruption, a dense cloud of smoke of many hues, but mostly copperred, was thrown upwards with such violence that it rose above the highest clouds.

On the New Britain coast we saw numerous natives and several huts, which were erected on stones in the Papuan style.

We left the strait before darkness fell.

Sailing along the north coast of New Britain, we discovered several small previously unknown islands. During this journey the current was barely noticeable; at the meridian of Port Montague only did we drift quickly northwards, which led us to conclude that we were off a strait dividing New Britain in two. On 9 July we left this coast, after our exploration had been made more difficult by south-east winds and frequent calms.

For a long time our food had consisted of wormy 365ship’s biscuit and tainted salt pork, and therefore scurvy was very prevalent. Most of us had to refrain from drinking coffee, because it induced troublesome convulsive episodes.

On 11 July we sailed close by the Portland Islands.

We sighted the eastern Admiralty Islands in the afternoon of the 12th, and about sunset on the 18th we sighted the Anchorites south-west by west.

About 7 o’clock on the 21st, our commander D’Entrecasteaux died from intractable diarrhoea, which had set in two days previously. Minor bouts of scurvy had afflicted him from time to time, but we were far from suspecting the severe loss that threatened us.

Several names of members of this expedition are preserved on current maps: D’Entrecasteaux, Willaumez, Dumerite, Cretin, Giquel, Huon, Kermadec, Riche, Duportail, and so on.

The real discoveries in the Bismarck Archipelago basically conclude with these two voyages by D’Entrecasteaux. The 19th century brought a series of more or less significant, isolated expeditions through which we become more closely acquainted with the coasts as well as with the land and people. Settlement followed only in the last quarter of the century.

After D’Entrecasteaux’s expedition, it was again the French who explored the archipelago. The frigate Coquille, under Duperrey, visited the northern Solomon Islands, New Ireland and New Britain in 1824. Lesson, the naturalist, accompanied the expedition. Then, in 1825, we find the French admiral Dumont d’Urville on his first South Seas expedition, and again, on a second expedition, in 1838.

The Englishmen, Sir Edward Belcher in the Sulphur and Lieutenant Kellett in the Starling, visited New Ireland in 1840. In Carteret Harbour, where their ships anchored, they even met a native who spoke a little English, whom the sailors christened Tom Starling. The latter reported that, from time to time, ships from Australia touched on the coast, and that a certain amount of trading had developed. An American named Jacob Kunde, who visited the South Seas in 1834 aboard the clipper Margaret Oakley, gave his accounts of the contact at that time; however, these were not published until 1844. Captain Morrell of the Margaret Oakley had certainly behaved neither more cruelly nor more humanely in his dealings with the natives than had his contemporaries; however, his contact for the most part consisted of hostile encounters, in which the natives always drew the shorter straw.

Captain Keppel, in the English warship Meander, passed the Purdy Islands on 29 December 1849. On the 30th and 31st he came into contact with the Admiralty Islanders, and, although he described them as excitable and noisy, the contact was nevertheless peaceful. On 4 January 1850 he passed the Sandwich Islands, and sailed along the coast of New Ireland with the intention of visiting Hunter Harbour. This was unsuccessful, and instead, on 6 January they anchored not far away in Makada Harbour. The Meander remained in Carteret Harbour from 8 January until the 12th. Captain Keppel and several of his crew visited a village north of the harbour and admired the carefully laid-out, well-kept gardens. Although the natives seemed peaceful, one had to be very alert. One of the officers, who had gone hunting, allowed two natives to guide him back to the Meander. On the way, they tried to steal his pocket watch, and he threw one of the thieves into the water, and threatened the second with his rifle butt before compelling him to guide him on board. This minor incident is so typical that one would not be surprised today, if something similar were to occur.

The English warship Blanche, Captain Simpson, discovered Blanche Bay in 1872, and anchored in the inner corner behind Matupi in Simpson Harbour.

Plate 55 Forest path on the Gazelle Peninsula. Breadfruit and canari trees, bananas

366At the same time, ships of the Hamburg firm Johann Cäsar Godeffroy & Sohn, established in Samoa, were occasionally visiting the archipelago from the Carolines, and the firm decided to open up the island group to trading. In 1873, the first traders were landed at Nogai at the foot of Mother, not far from Cape Stephens, and on the island of Matupi, by Captain Levison in the brig Iserbrook. The settlement at Nogai had to be abandoned after only four weeks on account of hostile behaviour from the natives, and the trader fled to his colleague on Matupi. Three weeks later, they had to flee from here as well, and seek sanctuary with an Englishman in Port Hunter, who was representing the interests of an English firm there. The following year Levison set up the first permanent German station at Mioko, Duke of York Islands.

The year 1875 greeted two scientific expeditions to the archipelago. The Challenger, commanded by Sir George Nares, with the scientific expedition led by Sir Charles Wyville Thomson, paid a formal visit to the Admiralty Islands from 3 until 10 March 1875. The ship anchored among small islands at the north-western end of the group, and since then the harbour has borne the name Nares Harbour. Contact with the natives was peaceful. The naturalist Moseley, who accompanied this famous expedition, gave comprehensive reliable accounts of conditions there. Our knowledge has not increased significantly since then.

The second scientific expedition was a German one, undertaken on the warship Gazelle, Captain von Schleinitz. It visited parts of New Hanover, New Ireland, the Gazelle Peninsula, and the island of Bougainville. The numerous German names on the map, like Bendemann, Dietert, Strauch, Rittmeyer, Steffen, Hüsker, and so on, stem from that expedition.

The same year also brought Christian missionaries to the archipelago. A Catholic mission had already been founded on Rook Island in 1852, but was abandoned after a brief existence. This time, a permanent station was founded at Hunter Harbour by the Wesleyan mission. The mission ship John Wesley anchored there on 15 August 1875 and, by the 16th, the missionary George Brown was marking out a building site. On 12 October, the first branch station was established at Nodup, at the foot of Mother, on the Gazelle Peninsula, and, several weeks later, two coloured catechists were stationed opposite on the coast of New Ireland.

Eduard Hernsheim founded a trading station at Makada in 1876; however, for health reasons, he transferred it to the small island of Matupi in Blanche Bay. The well-known Russian naturalist, Miklucho Maclay, visited the Admiralty Islands and several of the small western island groups the same year.

From then on warships of the various nations called in frequently, especially the ships of the English Australian squadron. The German warship Ariadne, Captain B. von Werner, made a visit in 1878, and subsequently, visits by German warships on the Australian station took place more and more frequently, to provide forceful backing wherever necessary to the aspiring German trade.

In 1879, the island of New Ireland was the stage for one of the greatest swindles of the century. In France that year, the Marquis de Ray established the colony ‘Nouvelle France’, which comprised all islands of the western Pacific that had not at that time been claimed by any power. The ship Chandernagor brought the first settlers, who landed at the south-east end of New Ireland. This miserable undertaking struggled on until 1882, when suddenly the great bubble burst, and the last of the cheated settlers, swindled out of their money, left the inhospitable coast. Thirteen million francs had been involved in this swindle, and numerous families were ruined.

Catholic priests who had accompanied the expedition and had, over time, seen through the swindle, moved to the Gazelle Peninsula. In 1881, Father Lanuzel set up a Catholic mission at Nodup, but had to abandon his station in 1883 as a result of dissension with the natives, caused by the activities of an Australian recruiting ship. However, the foundation of this station led to the Sacred Heart Missionary Society taking on the task, and proceeding with it.

The first plantation in the Bismarck Archipelago was established by the author in December 1882 at Ralum on the Gazelle Peninsula, and, in conjunction with this, the following year T. Farrell founded the trading and plantation firm which later experienced a significant upswing under the name E.E. Forsayth.