Chapter 10

Peace process or just peace deal? The media’s failure to cover peace

In general, the news media in the West do not appear to be particularly interested in the outside world. Coverage has decreased considerably from the Cold War days when foreign news accounted for up to 45 percent of the time allocated for network television in the US (Moisy 1996, p9). This is of course paradoxical, given the growing connectedness of the world, and the fact that advancing information and communications technology increasingly allows the media to gather news from and transmit it to more of the world more quickly than it ever has before. It is also paradoxical given the proliferation of media corporations that appear to have gone global, and the rise of the internet, obviating the need for media audiences to be gathered in a single geographical space, easily reachable by physical forms of communication.

Within the limited media coverage of the world in the US, there are high levels of disproportion, largely along lines of geography, culture and socioeconomic status (Tai 2000). Perhaps most notably, the African continent finds itself considerably marginalised in Western media coverage (Golan 2008; Franks 2010). This can also be seen in the coverage of conflicts and peace processes (Hawkins 2002; Beaudoin & Thorson 2002, p57), resulting in stealth conflicts – those that go on largely without appearing on the media ‘radar’. This marginalisation occurs despite the fact that conflicts in Africa have accounted for up to 88 percent of the world’s conflict-related deaths since the end of the Cold War (Hawkins 2008, pp12–25).262

Stealth conflicts are of particular concern considering the role of the media in the agenda-setting process that links actors in a position to respond to conflict. The media, particularly in the centres of power in the West, have the potential to influence public and policy responses to conflict, including expressions of concern, humanitarian aid, diplomatic pressure and, in some exceptional cases, military intervention. In this sense, the failure of the media to respond to conflict can also contribute to the lack of response to conflict by other actors. This is not to suggest that greater media coverage of a conflict will necessarily contribute to policies that will alleviate suffering and perhaps help move the conflict in the direction of a peaceful conclusion. Media coverage can often contribute to responses that have a negative impact on a conflict situation: through framing that does not reflect the reality on the ground, by oversimplification, and by taking sides. By the same token, much can be said for the potential of the media to influence public and policy responses in a positive way.

Does the disproportion in coverage levels seen in response to violent phases of conflict apply also to peace processes? This chapter examines the levels of media coverage that peace processes aimed at ending such stealth conflicts receive, relative to other more visible conflicts. It is based largely on a quantitative comparison of coverage of the peace process in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) with that in Israel–Palestine. It finds that there was proportionately less coverage of the peace process in the former case than there was in the latter, and that coverage was so limited and sporadic in the former that the media failed to refer to the series of events leading to the peace agreement as a ‘process’. The chapter then goes on to discuss why this is so.

Media coverage of peace processes

Peace is a process, not an event. It is not two signatures at the bottom of a document or a handshake among former enemies. This process necessarily goes far beyond any formal agreement, both in terms of time and in terms of how agreements are translated into change on the ground in the societies in question. And peace is not simply limited to the absence of violence (‘negative peace’), but it can also be seen as a condition in 263which the root conflict, or causes of the violence, are eliminated (‘positive peace’) (Galtung 1985). Nor are peace processes the sole domain of elite players – the contribution of grassroots efforts should not be underestimated. For the purposes of this study, however, the use of the term ‘peace process’ will be limited to the time period starting at the point of substantive negotiations aimed at stopping violent confrontation, and ending at the conclusion of (or the failure to conclude) a peace agreement. Provisionally using this narrow definition permits a quantitative evaluation of media coverage of peace processes according to what could be considered to reflect the media’s own definition of the term.

How do the media perform in covering ‘peace processes’ in this sense? While very little research has been conducted on this question, it is safe to say that the media perform quite poorly. In many cases, most of the little coverage that there is of conflict is focused on the violent phase, with very little on the peace process, or on the phases that precede and follow the violence (Jakobsen 2000). Indeed, the ‘needs’ of media corporations in going about the business of constructing news do not fit well with the needs of peace processes.

A successful peace process requires patience, and the news media demand immediacy. Peace is most likely to develop within a calm environment and the media have an obsessive interest in threats and violence. Peace building is a complex process and the news media deal with simple events. (Wolfsfeld et al. 2008, p374)

Media coverage of conflicts tends to be based on ‘violence journalism’, in which conflict is a battle between two sides, not unlike the coverage of a sports event in which two teams contest victory (Lynch & Galtung 2010, pp1–8).

Such ‘if it bleeds, it leads’ newsroom mentalities can be widely observed in the end product, the levels of media coverage of conflict situations. Various studies have found news of the world being dominated by negativity – conflict, violence and crisis (Beaudoin & Thorson 2002, pp48–49; Williams 2004, pp44–45). Peace processes themselves often seem to attract little coverage, and coverage of a conflict tends to quickly evaporate when the peace agreement is concluded. But this is 264not always the case. A limited number of peace processes do manage to attract considerable coverage. A study of coverage of the world in the Los Angeles Times, for example, found that 60 percent of stories focusing on the Middle East referred to conflict resolution (Beaudoin & Thorson 2002, p57). This was not the case for Africa. Only 16 percent of stories focusing on Africa referred to conflict resolution, and Africa accounted for just four percent of all conflict resolution stories recorded.

As noted above, news of peace has an inherent disadvantage in attracting coverage – ‘reporters search for “action” and when they find it their editors are more likely to place these stories in a prominent position’ (Wolfsfeld 2004, p20). But while peace in itself may appear serene, inactive and thereby not newsworthy, peace processes are not necessarily uneventful or without drama. There is the tension of bitter foes coming to sit at the same table, the outbreaks of residual violence that threaten to ruin the process, the threats of walkouts, the breakthroughs along the way, the anticipation of a successful outcome, and (hopefully) the jubilation and celebration when an agreement is finally reached. This may be followed by the withdrawal of troops and perhaps historic elections. The secrecy of the negotiations could also contribute to the excitement of the proceedings. Not as dramatic as explosions and killings, admittedly, but there is certainly room for some form of ‘action’ or drama.

This kind of drama is most likely the basis for the coverage of peace processes that does make it to the newspapers and television stations. Beaudoin and Thorson’s finding that there is, in fact, substantive coverage of conflict resolution – in some places rather than others – serves as a useful starting point for analysis. It raises the question of why some peace processes are able to attract considerable media coverage where others are not. With a view to addressing this question, this study is concerned with issue salience in the media agenda – the ‘what is covered’ (and, importantly, the ‘what is not covered’) rather than the ‘how it is covered’. That is, it is about objects (first-level or traditional agenda-setting) rather than the attributes (second-level agenda-setting) (McCombs 2004, pp69–71). While the question of how a peace process is covered is certainly an important one, and more coverage does not 265necessarily contribute to a positive outcome (it can, as previously mentioned, often have a negative impact), quantity of coverage must also be taken into consideration. This is particularly the case given that coverage of peace processes is often negligible, meaning that even the potential for a positive impact is absent. Where coverage is absent, so too are incentives for elite involvement in mediation efforts, the application of pressure on the parties to the conflict, and other forms of support for the process. It is in this sense that this study focuses on the quantity of coverage.

By examining the levels of media coverage of the peace process that brought an official end to the conflict in the DRC – a stealth conflict consistently marginalised by the media in the outside world – and comparing it to the coverage of other more visible peace processes, this study hopes to contribute to our understanding of the media’s perspectives on peace.

The case of the Democratic Republic of Congo

The conflict in the DRC may be the deadliest of our times. It saw the direct involvement of armed forces from nine countries (and the indirect involvement of many others), and numerous non-state forces, both foreign and local. It was simultaneously a series of international, national and local conflicts and became known as Africa’s First World War. In a series of mortality surveys conducted by the International Rescue Committee (IRC), the death toll was estimated at 1.7 million in 2000, 2.5 million in 2001, 3.3 million in 2003, 3.8 million in 2004, and 5.4 million in 2008 (IRC 2008). The results have recently been disputed by the Human Security Report Project as being far too high (HSRP 2010), but for the purposes of this study, it is important to note that during the period examined here (2001–2003) the ‘known’ (then undisputed) death toll stood at 2.5 million (IRC 2001), making it by far the deadliest conflict since the end of the Cold War.

In terms of a peace process, the Inter-Congolese Dialogue (ICD) from late 2001 to early 2003 (particularly 2002) is arguably the period most worthy of examination. While there had been a peace agreement before this (the Lusaka Agreement of 1999 set up the ICD but was 266regarded as a failure), and while the conflict has continued at varying degrees of intensity at a local level (with foreign sponsorship) after the conclusion of the ICD, this phase of the peace process culminated in the withdrawal of all foreign forces, the establishment of a transitional government and the official end of the conflict.

This was not a peace deal agreed upon in secret that suddenly took the outside world by surprise, nor was it a series of impasses or frustrating blocking manoeuvres from uncommitted parties that bore no fruit. The talks were presided over by a former head of state (Ketumile Masire of Botswana), in Ethiopia and then in South Africa. There were setbacks, walkouts and some fighting on the ground (at one point rebels captured a town, prompting the government delegation to walk out, only returning when the rebels promised to withdraw), and yet there was progress and a series of major and conclusive agreements (Apuuli 2004). The results of these agreements – large-scale troop withdrawals by foreign forces (30 000 troops from Rwanda alone) and the establishment of a transitional government – were quite tangible and visible. In short, this was an event-filled conclusion to the world’s deadliest conflict – there was plenty of ‘news’ to be reported. And yet very little of this process was being reported, and what was, was done so in a very piecemeal and disjointed manner.

Table 1: Timeline of the Inter-Congolese Dialogue (ICD) (2001–2003)

| Date | Event | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–23 Oct 01 | ICD opens in Addis Ababa | Talks break down | ||

| 26 Feb to 19 Apr 02 | ICD resumes with talks in Sun City | Agreement on power sharing framework reached | ||

| 25–30 Jul 02 | Rwanda–DRC peace talks | Bilateral peace agreement | ||

| 6 Sep 02 | Uganda–DRC peace talks | Bilateral peace agreement | ||

| 5 Oct 02 | Withdrawal of Rwandan troops ends | Complete withdrawal confirmed | ||

| 30 Oct 02 | Withdrawal of Zimbabwean, Angolan, Namibian troops ends | Complete withdrawal confirmed | ||

| 25 Oct to 17 Dec 02 | Talks in Pretoria by all Congolese parties to conflict, political opposition, civil society | Comprehensive power sharing agreement reached, formal end of conflict | ||

| 2 Apr 03 | Pretoria agreement ratified in Sun City | Conclusion of the ICD | ||

| 4 Apr 03 | Promulgation of transitional constitution |

267In order to examine how extensively this peace process was covered by the media in the outside world, a study was conducted of media coverage by The New York Times (US), The Times (UK), The Globe and Mail (Canada), and The Australian (Australia). Leading media sources from the US and the UK were selected because of their ability to influence the global information flow and the level of interest/response of other powerful global actors. Media sources from Canada and Australia were selected to examine the pervasiveness of trends in the global information flow. While both are Western countries, they can be seen as being distinct from the more powerful US and UK: Canada in terms of the government’s approach to foreign affairs issues, and Australia in terms of its geographic distance from the centres of power. The particular newspapers selected are known as newspapers of record in their respective countries. While this particular study looks only at English language media, it can be noted here that previous studies on the levels of coverage of conflict that included non-English media sources found comparatively higher levels of coverage on the DRC in the French language media than English language media, and almost insignificant levels of coverage in the Japanese media (Hawkins 2002; 2008, pp109–11).268

Using the LexisNexis database, a search was conducted for articles on the DRC during the period of the ICD. Articles were separated into those that focused primarily on the ongoing peace process and those that did not, including reporting centred around fighting and humanitarian suffering, as well as reporting unrelated to the conflict (such as volcanic eruptions and Belgium’s apology for its role in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba). As many articles contained a mix of these topics, articles coded as those focusing primarily on the peace process were determined to be those in which the coverage of the peace process accounted for more than half the article. Coverage of the peace process here included that of the progress of the peace talks (successes and failures) and their aftermath (in this case most notably foreign troop withdrawals), initiatives, gestures and the interventions and application of pressure by outside parties.

None of the sources studied appeared to show much interest in the peace process. While The New York Times, for example, did at least cover each of the events in Table 1, it did so in very little depth. Perhaps most telling is the fact that 65 percent (31 of 48) of all articles focusing on the peace process were not full articles, but world briefings, none being more than 130 words in length. In fact the average length of an article on the peace process in this period was just 263 words. Of the events in the course of the ICD, the peace agreement between Rwanda and the DRC attracted the most coverage (five articles and one briefing), and the withdrawals were also covered. The Sun City peace talks that preceded this were mostly glossed over in world briefings, and, by the time talks were underway in Pretoria, what interest there was had mostly been lost. A world briefing mentioned that talks were resuming, but no updates were offered on the progress of the talks until two months later, when a single article informed readers that the Pretoria agreement had been signed. While this article did contain some information on the agreement and some background of the conflict, no analysis or followup articles were printed after this.

The New York Times had more to say about the peace process than the other sources studied. The Times printed a series of substantive articles on the Rwanda–DRC peace agreement, but little more. Only 269one substantive article was produced on the Sun City talks (231 words noting that the talks had collapsed) and none was forthcoming on the Pretoria talks or agreement or the ratification of the deal in Sun City in 2003 (world briefings are not included in the LexisNexis database for The Times and were not examined). The most detailed article dealing with the DRC in general was a 2874-word article by a reporter travelling with UK Secretary of State for International Development, Clare Short, on a four-day tour of the DRC, Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda. It is essentially a travel/adventure diary (not a news article) with hints of colonial nostalgia: they were ‘buccaneers’ who faced spies, rebels and food poisoning, and crossed the Congo River in a pirogue (Treneman 2002).

Canada’s The Globe and Mail first acknowledged the existence of the peace talks in March 2002, with a 35-word brief noting that the DRC Government had pulled out of the peace talks in Sun City (it never mentioned there were talks going on to begin with). In the 18 months of the ICD, this newspaper published only four substantive articles on the entire peace process – one on the Rwanda–DRC peace deal, two (one article and one editorial) on the Pretoria agreement, and one editorial after the final Sun City agreement. With no apparent irony, the article on the Rwanda–DRC deal opens with the words ‘It’s a forgotten war’ (Nolen 2002), and the final editorial, entitled ‘The invisible war’ invites readers to ‘Spare a thought for the war that is not being brought live to living rooms across North America’ (Anon 2003). In total, briefings that averaged 53 words accounted for 78 percent (14 of 18) of the articles published on the peace process.

The Australian newspaper took no half measures in its marginalisation of the DRC peace process. It needed only 672 words to cover the entire 18 months of the ICD: 41 words to note that talks would be starting in Addis Ababa, 37 words to report that Rwanda and the DRC would sign a deal, 568 words when that deal was signed, and 26 words after the ratification of the comprehensive agreement in April 2003. The newspaper missed the crucial talks and agreements at Sun City and Pretoria altogether. Oddly enough, in the same period it did report on other news in the DRC, such as the eruption of a volcano, 270students arrested for protesting high school fees, 17 people killed in a freak storm, illegal miners killed after being sealed into a mine, and alleged cannibalism. It had more to say in a single article about a Congo exhibition in Belgium than it did about the entire course of the peace process (Sutherland 2002). See Hawkins (2009) for a more detailed look at the coverage of the DRC conflict in The Australian.

Some comparisons

It is useful to examine how the coverage of the peace process in the DRC compares to that of other peace processes. This section will begin by comparing the coverage in The New York Times of the peace process in the DRC in 2002 with coverage of the Israel–Palestine peace process in 2003. It should be noted from the outset that the lessons that can be learned from comparing two very different peace processes at different stages are limited and certainly need to be handled with care. There are, however, some similarities between the two peace processes in these periods, and, by focusing on a period of one year, a very basic comparison is possible.

In both cases, there were movements in the peace processes throughout the course of the year. Major agreements were debated for a number of months and were adopted. In both cases, agreements saw the withdrawal of foreign forces – Israeli forces from northern Gaza, and all foreign forces (except Uganda) from the DRC. The involvement in the process of the US at the presidential level in the Israel–Palestine case is clearly a major difference between the two, and this could be expected to serve as a major boost to coverage. On the other hand, whereas the Israel–Palestine case was a debate on a ‘road map’ towards an agreement (not by any means an agreement in itself), the DRC case saw the successful conclusion of a number of both international (bilateral) and national comprehensive agreements and the official end to the conflict. Furthermore, the DRC conflict was known to be the world’s deadliest, with a death toll hundreds of times greater than that in Israel–Palestine. These points could conceivably have justified a boost in coverage of the DRC peace process.

A quantitative study of media coverage is clearly not needed to tell us that there was more coverage of the Israel–Palestinian peace process 271than there was of the DRC peace process. The question is how much more? Two previous studies that compared the overall coverage of these conflicts (the violence, humanitarian issues and the peace processes combined) in The New York Times (one covering the year 2000, Hawkins 2002; and one covering the year 2009 Hawkins unpublished) found that Israel–Palestine attracted 12–13 times more coverage than the DRC. This study, isolating the coverage of the peace processes (for 2002 in the case of the DRC and 2003 in the case of Israel–Palestine), found that there was 20 times more coverage for Israel–Palestine (more than 225 000 words) than there was for the DRC. That is, the peace process of the DRC conflict attracted comparatively less attention than did the violence and humanitarian aspects.

A similar comparison of the coverage of the DRC and Israel–Palestine peace processes in The Australian sent the disproportion to new heights, with coverage of the Israel–Palestine peace process being 115 times higher than coverage of the DRC peace process. In the case of The Globe and Mail, one day of coverage on the Israel–Palestine peace process (1 May 2003, when the ‘road map’ was unveiled) was more than enough to exceed the 18 months of coverage on the DRC peace process in that newspaper.

It is also worth pointing out that in The New York Times the average length of an article on the peace process in the case of Israel–Palestine was 864 words – almost three times longer than the average length of an article on the DRC peace process. This means that not only was there far more coverage of the Israel–Palestine peace process as a whole, but that each individual article dealt with the issue in far greater depth. The majority of articles on the peace process in the DRC simply noted, very briefly, that an event that had taken place (for example, talks breaking down, or a deal being signed), whereas articles on the peace process in Israel–Palestine included analysis, a variety of viewpoints, and depth. On a general methodological note, this also suggests that very different results may be obtained from quantitative studies of media coverage depending on whether numbers of articles are counted, or the numbers of words in the articles.272

Comparisons with other less extreme examples (cases considered less relevant to powerful political interests) can also help boost our understanding of the coverage of peace processes. In this light, this study also looked at coverage in The New York Times of peace processes in Darfur, Kenya and Nepal. In the case of Darfur, the study followed the conclusion of peace talks in Nigeria in May 2006 that resulted in a peace agreement with one faction of the rebel Sudan Liberation Army (other groups did not sign). Substantive articles appeared in the paper on a daily basis for the first nine days of May, and in less than one month the quantity of reporting on the peace process for Darfur easily exceeded that for the 18 months of the DRC peace process.

An eruption of post-election violence left 1300 people dead and hundreds of thousands displaced in Kenya in late 2007 and early 2008. Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan attempted to mediate, and an agreement on power sharing was reached in March 2008. Coverage of the conflict itself was relatively heavy in The New York Times, as was the peace process that led to the power sharing agreement. The roughly two months of coverage of the peace process exceeded the 18 months of the DRC peace process.

Conflict in Nepal between government and Maoist rebel forces, while far less deadly than that in the DRC, was deadlier than that in Israel–Palestine or Kenya, with an estimated death toll of 13 000 people since 1996. The year 2006 saw the fall of the monarchy and a peace agreement with the rebels. The combined coverage of these two phases of the peace process in The New York Times (over a period of approximately eight months) was considerably greater than that for the course of the DRC peace process.

Peace process or peace deal?

One of the products of a peace process is a peace agreement, or deal. Peace deals do not happen overnight. They are almost invariably the result of long and painstaking negotiations, accompanied at times by impasses, setbacks, walkouts, prodding by third parties, and compromises. Such a ‘process’ may happen very quickly when one of the parties to the conflict vanquishes the other, as seen in Angola in 2002, Iraq 273in 2003, and Sri Lanka in 2009 (the ‘agreement’ of the vanquished is not really required), or when the conflict itself is very short, as seen in Kenya in 2008, for example. In the majority of cases, however, the process leading to a deal is a long and complex one.

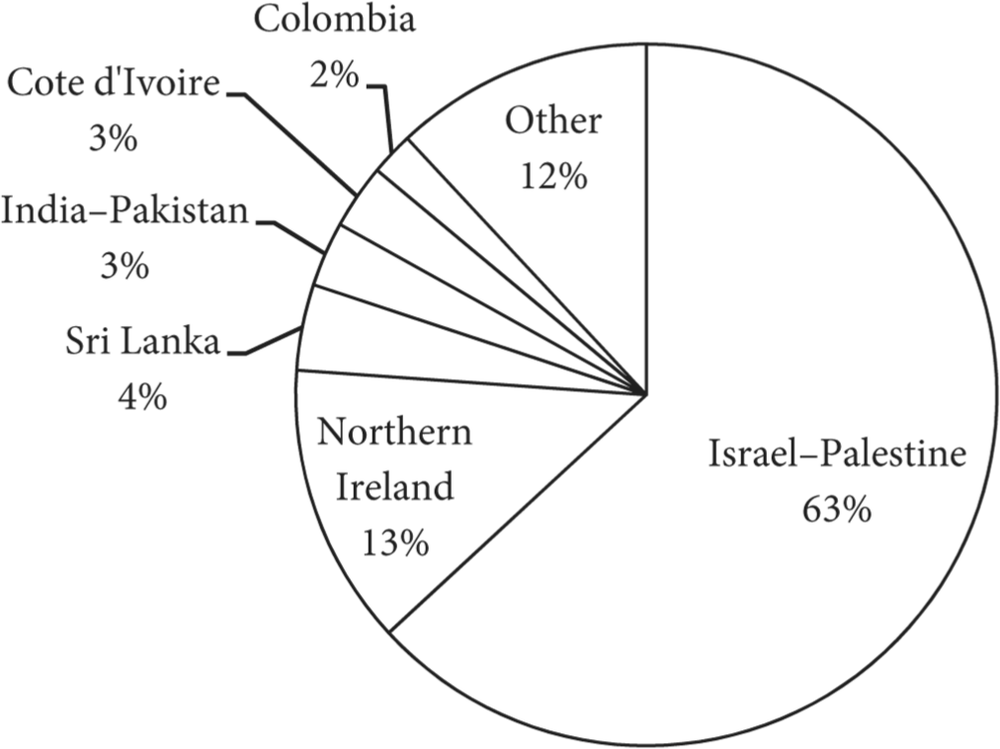

Figure 1: Use of term ‘peace process’. The New York Times, 2000–2009 (n=276).

But do the media portray the series of events leading up to a peace agreement as a peace process? In most cases, they appear not to. This study conducted a LexisNexis search of the term ‘peace process’ in the headline or lead paragraphs of The New York Times articles for the period from 2000 to 2009, and recorded the conflict to which the term was referring. Figure 1 is a summary of the results. Over the course of the ten years examined, more often than not (63 percent of cases) the term ‘peace process’ was used in reference to a single conflict – that in Israel–Palestine. A considerable number of references was also found for Northern Ireland, but the use of the term was a rarity beyond these two cases. In some instances, the term was used not by the reporter 274writing the article, but by the political leader being interviewed (seen in the case of India–Pakistan and Somalia). In the case of the DRC, the term was used in just three articles with an average length of 107 words, and only one of these was during the course of the ICD. Interestingly, there also appears to be no ‘peace process’ for the two conflicts that are most heavily covered by the newspaper – those in Iraq and Afghanistan (there was only one reference for each), a reflection that the primary ‘solution’ in each case has been considered a military one.

The series of events that led to the Pretoria agreement in 2002, and its ratification in Sun City in 2003, was certainly a process. It had a clear beginning, a conclusion and a set of steps that got it from one to the other. It even had a name – the Inter-Congolese Dialogue. So why didn’t the media call it a ‘process’? In the case of Israel–Palestine, every twist and turn in the ‘road’ supposedly headed in the direction of peace has been reported – every proposal, every concession and gesture, every day of talks, every rejection and collapse. The dots along the timeline that has been presented by the media are so close together that there is somehow a connectedness, a sense of continuous action in a particular direction, however little apparent progress there had been. In the case of the DRC, however, the dots marked along the timeline were so few and far between (and so fleetingly and marginally recorded) that it was difficult for them to be connected in a coherent pattern, however process-like the series of events were. There were plenty of twists and turns along the road to the comprehensive peace agreement, but few of them were reported (or reported in any depth). As a result, the media reported the existence of a ‘deal’, ‘accord’ or ‘agreement’, but not a ‘process’.

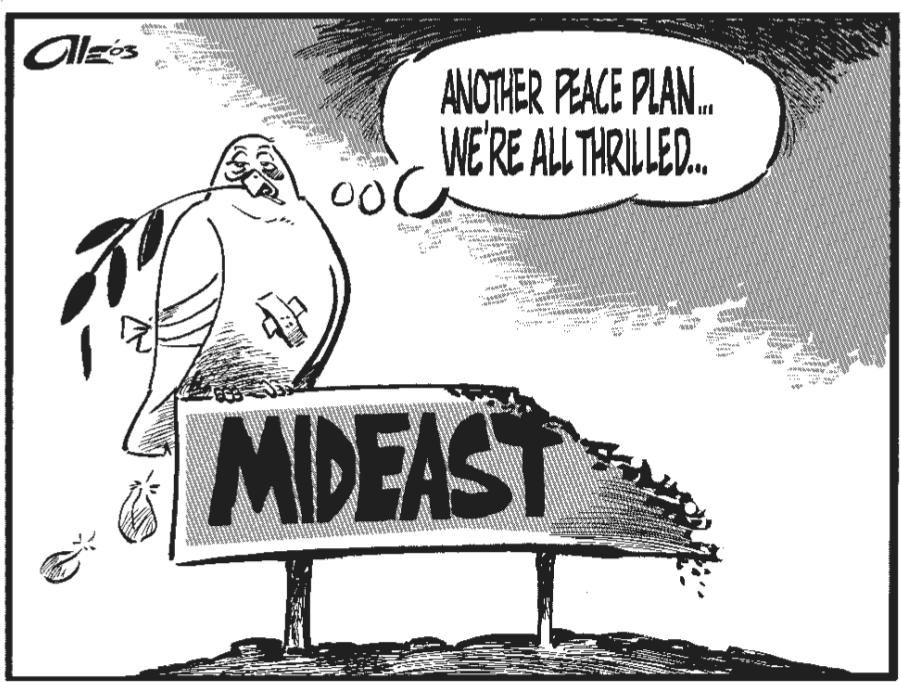

The notion of ‘peace’ itself tends to be heavily associated by the media with the conflict in Israel–Palestine, something that can also been seen in the use of artwork in the media. A search for the word ‘dove’ (a symbol of peace) in the online collection of political cartoons on the website Politicalcartoons.com, for the period 2000 to 2009, revealed that of those cartoons that included imagery of doves in reference to a specific conflict, 56 percent were on Israel–Palestine (a further eight percent were on the Israel–Lebanon conflict). There were no such 275cartoons appearing in reference to the DRC. The fact that the dove usually appeared in these cartoons about the Israel–Palestine conflict being eaten, blown up, decapitated, or otherwise maimed/threatened is ironically indicative of the fact that there has been little progress in achieving peace there. That the dove continues to be used primarily to refer to this particular conflict, regardless of this paradox, is indicative of how heavily the peace process there is being covered by the media.

What factors determined the coverage?

A number of studies have attempted to pin down the factors behind the newsworthiness of events. In 1965 Galtung and Ruge published a set of 12 factors that they found to be key determinants: frequency, threshold, unambiguity, meaningfulness, consonance, unexpectedness, continuity, composition, reference to elite nations, reference to elite people, reference to persons, and reference to something negative. Harcup and O’Neill (2001) reviewed these factors, made adjustments, and came up with the following ten, for the British press: the power elite, celebrity, entertainment, surprise, bad news, good news, magnitude, relevance, follow-up, and newspaper agenda. Golding and Elliott (1979) published a similar set of criteria, but, critically, added proximity to the mix. Shoemaker and Reese (1996) identified a ‘hierarchy of influences’, or five levels that influence news content: individual preferences and background, organisational routines, editorial policy and other organisational imperatives, extra-media influences, and ideology (at societal level). Allern, pointing to the need for a greater emphasis on commercial news criteria, added a number of criteria, perhaps most notably that ‘the more resources – time, personnel and budget – it costs to cover, follow up or expose an event, etc., the less likely it will become a news story’ (Allern 2002, p145).

In terms of factors specifically aimed at conflicts and peace processes, Hawkins (2008, pp189–202) proposed a list of factors behind the attention (not only of media, but also of policymakers, the public and academia) a conflict attracts: national/political interest, geographic proximity/access, ability to identify, ability to sympathise, simplicity, and sensationalism. Wolfsfeld (2004, pp15–23) identified immediacy, 276drama, simplicity, and ethnocentrism as factors that determine attention for events making up a peace process, although this focused on media based within the conflict zone, rather than outside it. So how well do these lists apply to the salience in the media agenda of the peace processes raised in this study? Of course, these lists are not manuals or checklists. Some criteria apply and others do not, and whether or not a particular situation will attract and sustain the media’s attention depends not only on how many of these criteria it meets, but also on how strongly each of the criteria applies, not to mention from whose perspective they apply – in some cases one might be enough.

Comparing the cases of the DRC and Israel–Palestine, a number of factors are apparent. Although the elite nation (or power elite, national/political interest) criteria may be somewhat ambiguous, Israel can be said to carry an elite nation status, largely because of the importance conferred on it by its elite nation allies. The rise in coverage that accompanied the US president’s visit and proposal of the ‘road map’, and the rise accompanying the visits of other elites from the US, can be considered to serve as an example of the elite nations and elite people criteria. The meaningfulness/relevance/ability to identify factors can also apply in the Western world, not only because of the relatively high socioeconomic status of the participants, but also because the area of contestation is considered to be the Holy Land by Muslims, Jews and Christians alike. Continuity/follow-up are also relevant criteria – the conflict has always been the subject of heavy coverage and therefore it continues to be.

The DRC, on the other hand, had few of these criteria to recommend it as a news topic. None of the factors that applied to Israel–Palestine was relevant in this case. There was no direct or open involvement by elites (nation or person), and a conflict affecting poor black people apparently has limited relevance for those in the affluent white-dominated West. The limited elite interest in the conflict in the DRC undoubtedly served to deter media attention. As a conflict sparked by the invasion of US/UK allies Rwanda and Uganda, and given the mining interests of powerful Western corporations, attention to the situation in the DRC was potentially embarrassing for elite interests in the West. From the 277elite perspective, those suffering in the DRC were not ‘worthy victims’ (Herman & Chomsky 1994, pp37–86). Furthermore, as the conflict was consistently marginalised from the outset, the trend continued throughout the peace process – a mark of continuity.

It is important to note that while the threshold/magnitude criteria may apply to domestic news or accidents, it is not relevant in the case of conflict and conflict resolution. The scale of a conflict (marked, for instance, by death toll) is, for all intents and purposes, unrelated to the level of media attention it attracts. As this study confirms, conflicts with relatively small death tolls often attract heavy coverage, while many of the world’s deadliest conflicts are consistently absent from the media radar. The fact that the peace process for what was by far the world’s deadliest conflict could only attract one-twentieth at most (less than one-hundredth at least) of the quantity of coverage of a peace process aimed at resolving a conflict with a death toll hundreds of times smaller makes the magnitude criteria altogether irrelevant.

The negative/bad news and good news criteria also didn’t seem to have a considerable impact here. In the case of Israel–Palestine, there was little particularly good news (the successful conclusion of a deal, for example), and the failure of the process was gradual – there was no major negative incident that suddenly destroyed the entire peace process. To begin with, the starting point of the ‘road map’ was not met with a great deal of expectation. A political cartoon by Olle Johansson (reprinted here) summed up the mood of the times. A battered and very unenthused peace dove sitting on a shot-up signboard (to the Middle East) says sarcastically to the readers, ‘Another peace plan … we’re all thrilled’. Yet coverage of each intricate part of the peace process was reported in detail alongside the negativity of the violence. In the case of the DRC, the agreement was particularly good news. Although there was trouble brewing in Ituri, the bilateral peace deals were conclusive, as was the comprehensive peace agreement in Pretoria, which led to the establishment of a transitional government; and the large-scale troop withdrawals were very visible positive effects. This end to the world’s deadliest conflict should have done something to offset the factors that prevented its coverage, but it did not.278

None of the other peace processes studied (Darfur, Kenya, Nepal) came close to the levels of coverage of the Israel–Palestine peace process, but all attracted greater coverage than did the DRC peace process. None involved elite nations or elite people, but, importantly, in some cases there was elite interest in their resolution. In the case of Darfur, there was a degree of US policy interest, and the peace talks came at the peak of public interest in the US, coinciding with a series of highly coordinated nationwide rallies for Darfur. In the case of Kenya, an elite person (immediate past UN Secretary General Kofi Annan) stepped in as mediator.

© Olle Johansson 2003. Reproduced with permission

This is in line with studies finding that the media agenda largely follows the lead of the policy agenda – indexing (Bennett 1990) and (to a slightly lesser degree) cascading network activation (Entman 2004). Indexing holds that the media coverage reflects the strength of the voices in government. When there is consensus in government, the media will present that perspective; when there is debate within government, those perspectives will be offered; and the lack of policy voices will be matched by a lack of media coverage. In a somewhat more nuanced approach, the cascading network activation portrays agenda items 279originating primarily from the policy elites at the top of the ‘cascade’, but allows for items ‘splashing’ back up to the top from the lower tiers.

Other factors helped boost coverage. While the DRC and Israel–Palestine conflicts and peace processes were portrayed in very complex terms, the Darfur, Kenya and Nepal conflicts were reported in simplified one-on-one formats (the realities in each case were, of course, far from simple). Israel–Palestine is also essentially a one-on-one conflict, but the solution is reported in great detail and complexity. With so many actors at different levels with different motives and objectives, the DRC conflict has always been unsimplifiable. This has set it apart from other conflicts and can be considered a major factor in its marginalisation. In the case of Kenya, the element of unexpectedness/surprise also served as a major factor in the levels of interest. The conflict suddenly appeared in what was thought to be a relatively peaceful country. The media also attempted to connect readers to the conflict using the images already in their minds (meaningfulness/relevance). There were stories in The New York Times about the damage to the tourism industry and the dangers faced by marathon runners.

Commercial news criteria also need to be considered as major factors determining the levels of coverage; most notably, the proximity of news bureaus to the events. The long-term interest in the Israel–Palestine conflict has resulted in the stationing of numerous bureaus and reporters; most in Israeli-controlled West Jerusalem. As such, newsgathering is possible for however long a peace process goes on at little marginal expense. The same can be said of the Kenya process. Nairobi is one of the few places in Africa in which Western journalists are stationed. Jeffrey Gettleman, for example, reported for The New York Times on the conflict and peace process in Kenya from the newspaper’s already established bureau there. There are no such bureaus in the vicinity of the DRC, making decisions to gather news from there expensive ones, with approved expeditions measured in days, not months. A short-term focus on the DRC peace process can be seen in The Times (UK), for example, with the bulk of the reporting during this period (the peace agreement with Rwanda) coinciding with a tour of the region by Africa-based journalist Michela Wrong.280

Admittedly, the peace process for the DRC was conducted largely in relatively accessible South Africa (The New York Times has a bureau in Johannesburg), but covering both the peace process and the situation on the ground would have required two reporters. Such a split did not, however, prevent substantive coverage of the peace talks for Darfur taking place in Nigeria. Distance did little to stop coverage of the sensational volcanic eruption in eastern DRC. In each of the newspapers studied, less than one week of coverage of the eruption and its effects exceeded that of months of coverage of the peace process. In the case of The Australian, coverage of the eruption easily exceeded coverage of the entire 18-month peace process. A short stay to cover a sensational event (parachute journalism) makes good business sense, but a long stay to cover a peace process does not.

Finally, the influence of the elite news media on other news media, or intermedia agenda-setting (McCombs 2004, pp113–17), needs to be considered. With few foreign correspondents, smaller newspapers rely on other more powerful newspapers and agencies not only for their newsgathering capacity, but also for their judgements on newsworthiness. This pack journalism mentality results in a convergence of news agendas – many different newspapers end up reporting on the same peace process. Although information is certainly available from reputable sources (primarily news agencies) on events occurring in the DRC, a newspaper is unlikely to buy this news and publish it unless it is already considered by more powerful news sources as being newsworthy.

Conclusion

It is no secret that the Western mainstream media marginalise conflict in Africa (or Africa in general, for that matter), giving much greater coverage to conflicts in Europe and the Middle East. This chapter has examined how these trends applied to peace processes, comparing the media coverage of the peace process in the DRC over the course of the Inter-Congolese Dialogue and the conclusion of a series of comprehensive peace agreements, with part of the peace process in Israel–Palestine 281(the announcement of the ‘road map’ in 2003) and, to a lesser degree, with peace processes in Darfur, Kenya and Nepal.

It found that, of the peace processes examined here, the DRC was by far the least covered. This was despite the fact that the conflict in the DRC was a multinational affair with a death toll hundreds of times greater than the others, and despite the scale of the achievements made possible by the successful conclusion of the peace agreements there – the withdrawal of tens of thousands of foreign troops and the establishment of an inclusive transitional government. Furthermore, the study found that, relative to the coverage of the violent phase of the conflict, the proportion of coverage of the peace process was considerably less for the DRC than it was for Israel–Palestine. In fact, the coverage of the peace process in the DRC was so little and so sporadic, that the media did not identify the organised set of events leading up to the peace agreement as a peace process. They were reported simply as peace deals or agreements.

The reasons for this marginalisation are complex, but include the lack of involvement and interest of elite nations and persons, the perceived failure of a predominantly white and affluent audience to identify, the sheer complexity, the fact that the conflict has been consistently marginalised in the past (continuity), commercial factors such as the lack of reporters permanently stationed in the vicinity, and the gravitational pull of powerful agenda-setters in the media.

Peace journalism focuses on the manner in which conflict, violence and peace are covered by the media. It is an approach that is not only critical in enhancing the public’s understanding of conflict, but one that can also encourage and promote efforts towards peace. In this sense, it is certainly a worthy pursuit. At the same time, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that the majority of armed conflicts, and, critically, the peace processes aimed at ending them, are rarely covered by the media in any form. With a view to furthering understanding of these conflicts and enhancing the exploration of scenarios that will lead to a positive outcome, perhaps room can be made in the peace journalism movement for encouraging improvements in the quantity, as well as quality, of journalism related to armed conflict and its resolution. 282

References

Allern, Sigurd (2002). Journalistic and commercial news values: news organisations as patrons of an institution and market actors. Nordicom Review, 23(1–2): 137–52.

Anon (2003). The invisible war. Globe and Mail. Toronto. 4 April 2003. [Online]. Available: www.theglobeandmail.com/subscribe.jsp?art=385343 [Accessed 2 August 2011].

Apuuli, Kasaija (2004). The politics of conflict resolution in the Democratic Republic of Congo: the Inter-Congolese dialogue process. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 4(1): 65–84.

Beaudoin, Christopher & Esther Thorson (2002). Spiral of violence? Conflict and conflict resolution in international news. In Eytan Gilboa (Ed). Media and conflict: framing issues, making policy, shaping opinions (pp45–64). Ardsley: Transnational Publishers.

Bennett, W. Lance (1990). Toward a theory of press-state relations in the United States. Journal of Communication, 40(2): 103–25.

Entman, Robert (2004). Projections of power: framing news, public opinion, and US foreign policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Franks, Suzanne (2010). The neglect of Africa and the power of aid. International Communication Gazette, 72(1): 71–84.

Galtung, Johan (1985). Twenty-five years of peace research: ten challenges and some responses. Journal of Peace Research, 22(2): 141–58.

Galtung, Johan & Mari Holmboe Ruge (1965). The structure of foreign news: the presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. Journal of International Peace Research, 1: 64–91.

Golan, Guy (2008). Where in the world is Africa? Predicting coverage of Africa by US television networks. International Communication Gazette, 70(1): 41–57.

Golding, Peter & Philip Elliott (1979). Making the news. London: Longman.

Harcup, Tony & Deirdre O’Neill (2001). What is news? Galtung and Ruge revisited. Journalism Studies, 2(2): 261–80.283

Hawkins, Virgil (2009). National interest or business interest: coverage of conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the Australian newspaper. Media, War and Conflict, 2(1): 67–84.

Hawkins, Virgil (2008). Stealth conflicts: how the world’s worst violence is ignored. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Hawkins, Virgil (2002). The other side of the CNN factor: the media and conflict. Journalism Studies 3(2): 225–40.

Herman, Edward & Noam Chomsky (1994). Manufacturing consent: the political economy of the mass media. London: Vintage.

Human Security Report Project (HSRP) (2010). Human Security Report 2009/2010: the causes of peace and the shrinking costs of war. [Online]. Available: www.hsrgroup.org/human-security-reports/20092010/overview.aspx [Accessed 2 August 2011].

International Rescue Committee (IRC) (2008). Mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo: an ongoing crisis. [Online]. Available: www.rescue.org/special-reports/congo-forgotten-crisis [Accessed 2 August 2011].

International Rescue Committee (IRC) (2001). Mortality in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: results from eleven mortality surveys. [Online]. Available: www.grandslacs.net/doc/3741.pdf [Accessed 2 August 2011].

Jakobsen, Peter (2000). Focus on the CNN effect misses the point: the real impact on conflict management is invisible and indirect. Journal of Peace Research, 37(2): 131–43.

Lynch, Jake & Johan Galtung (2010). Reporting conflict: new directions in peace journalism. St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press.

McCombs, Maxwell (2004). Setting the agenda: the mass media and public opinion. Cambridge: Polity.

Moisy, Claude (1996). The foreign news flow in the information age. Cambridge: Harvard University.284

Nolen, Stephanie (2002). Skepticism surrounds peace deal: Rwanda and Congo prepare to sign accord that could be historic, or another false hope. Globe and Mail. Toronto. 30 July: A9.

Shoemaker, Pamela & Stephen Reese (1996). Mediating the message: theories of influence on mass media content. London: Longman.

Sutherland, Tracy (2002). Congo exhibition to jolt nostalgic Belgians. The Australian, November 4: 16.

Tai, Zixue (2000). Media of the world and world of the media: a cross-national study of the rankings of the ‘top 10 world events’ from 1988 to 1998. Gazette, 62(5): 331–53.

Treneman, Ann (2002). Fixed in short time. The Times. 20 February: features.

Williams, Paul (2004). Britain and Africa after the cold war: beyond damage limitation? In Ian Taylor & Paul Williams (Eds). Africa in international politics: external involvement on the continent (pp41–60). Oxon: Routledge.

Wolfsfeld, Gadi (2004). Media and the path to peace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wolfsfeld, Gadi, Eitan Alimi & Wasfi Kailani (2008). News media and peacebuilding in asymmetrical conflicts: the flow of news between Jordan and Israel. Political Studies, 56(2): 374–98.