9

“CULTURE WARS”: GETTING TO PEACE

KEYNOTE ADDRESS

I start with some stories and then an observation on the way to an argument about what we should do about “The Culture Wars”.

The first story

A long time ago in a place far away (Europe), the elite spoke Latin while the masses spoke “vulgar” languages (English, French and Germany). The elite ignored the masses. The masses ignored the elite.

The second story

In 1927, Huxley, wrote this:

In the days before machinery men and women who wanted to amuse themselves were compelled, in their humble way, to be artists. Now they sit still and permit professionals to entertain them by the aid of machinery. It is

111difficult to believe that general artistic culture can flourish in this atmosphere of passivity.2

John Philip Souza had uttered that very same idea about two decades before. Souza was testifying at the United States Capitol about what he called “the talking machines.” As he said:

These talking machines are going to ruin the artistic development of music in this country. When I was a boy … in front of every house in the summer evenings you would find young people together singing the songs of the day or the old songs. Today you hear these infernal machines going night and day. We will not have a vocal chord left. The vocal chords will be eliminated by a process of evolution, as was the tail of man when he came from the ape.

This is a picture: the picture of young people singing the songs of the day or the old songs. It is a picture of culture that we might call, using modern computer terminology, a kind of “read-write” culture. It’s a culture where people participate in the creation and re-creation of their culture. In this sense it is read-write.

Souza’s fear was that we would lose the capacity to engage in this read-write culture because of these “infernal machines”. They would take it away – displace it – and in its place we would have the opposite of read-write culture, what could call, using modern computer terminology, a kind of “read-only” culture. A culture where creativity was consumed, but the consumer was not a creator; a culture, which was top-down, where the “vocal chords” of the millions of ordinary people have been lost.

If you look back at the 20th century, at least in what we call the “developed world”, it is very hard not to conclude that John Philip Souza was right. Never before in the history of culture had its production become as concentrated. Never before had it become professionalised. Never before had the ordinary people’s creativity been effectively displaced and displaced for precisely the reasons that Souza spoke of because of these “infernal machines”. The 20th Century was the century of read only culture, and it stands against a background of read-write culture from the beginning of man.

Why was it like this? The answer is technical, or at least largely technical. This was the age of broadcasting and vinyl. It produced a culture that could do little more than passively consume. It enabled efficient consumption, thus “reading”, but inefficient production, at least by ordinary people, thus “writing.” It was an age wired for mass reading; it was an age that discouraged mass writing.

112

The third story

In 1919, the United States voted itself dry. By a constitutional amendment, the nation launched a war against an obvious evil: the dependence upon intoxicating liquors. This was a war waged first by the progressives of the era, people who thought they could use law to make man better.

A decade later, this war was largely failing. The police found it increasing difficult to stop the illegal trade of intoxicating liquor. They therefore adopted new techniques to fight back. One such technology was the wiretap. And in a case involving Roy Olmstead and other defendants,3 the Supreme Court had to consider whether this technique, the wiretap, was legal.

To answer that question, the Supreme Court looked at our Constitution — in particular to the Fourth Amendment. That Amendment reads:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

The question the Court had to answer was whether police attaching a wiretap to the telephones of Roy Olmstead and his associates, without any judicial authorisation, violated this prescription against “unreasonable searches and seizures”.

The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, former President William Howard Taft, looked at the objectives of the Fourth Amendment. These, he held, were to protect against “trespassing.” Wiretapping, however didn’t necessarily involve any trespass. There was no need to enter the apartment of Mr Olmstead to tap his phones. The police just needed to attach an alligator clip to the telephone wire once it left the apartment. Since there was no trespass, Taft held, there could be no violation of the Fourth Amendment. And thus was there no constitutional proscription against the government tapping telephones in the United States until the Court reversed itself until 1968.

More important than the opinion of the Court was a critical dissent by Justice Louis Brandeis. There was a principle at stake here, Brandeis wrote. That principle

113was to protect against a certain kind of invasion. It was, in other words, to protect “privacy.” But how you protect privacy is a function of technology. Citing an earlier case, Brandeis wrote, “time works changes” in those technologies. And thus the objective of the Court must be to translate old protections into a new context.

Brandeis lost, and the wiretap won. But by 1933, the war against intoxicating liquor had been deemed a failure. Increasing costs — the rise in organised crime, the fall in civil rights — and vanishing benefits — everyone drank, Prohibition notwithstanding — led the country to realise that perhaps costs outweighed the benefits. In 1933, Prohibition was ended and peace was declared by a constitutional amendment that repealed the constitutional amendment that had banned the sale of intoxicating liquors.

But the important point to recognise here was that what was repealed was not the aim to fight dependence on alcohol. All that was “repealed” was the idea of using war, or this metaphorical war, as a means to fight that dependence on intoxicating alcohol

Observations

Think about the idea of “writing”. Writing is a quintessentially democratic activity. I don’t mean that we vote upon what you are allowed to write. I mean instead that we expect everyone to have the capacity to write. Indeed, we teach our children how to write, and we measure the quality of their education on the basis of how well they write.

Why is it that we teach our kids how to write? I can understand why we teach them how to write in 1st grade to 8th grade, when they learn the basics to understand how to use words to communicate. But why do we waste our time teaching them to write from about 9th grade to college? Why do we tell them they have to write essays on Shakespeare or Hemingway or worse still, Proust? Why would anybody force their children into this activity? What do they expect to gain, because I can assure you, as a Professor who reads the writing of many students, that the vast majority of this writing is just “crap”. So why do we do it?

The answer is obvious, but we should remark it nonetheless. We all understand that we learn something in the act of writing even if what we write is no good. We learn, if nothing else, respect for just how hard this creativity is, and we learn the value of the ability to engage in that creativity.

Now within this democratic activity of writing, think about a particular activity called “quoting.” I had a friend in college who wrote essays that were essentially the stringing together, in the most elaborate and artistic way, of quotes that he had 114gathered from other writing, in order to make a point that was the point of his essay. He always got the very highest grades for that writing. He took it for granted that he could take, and use, and build upon, other people’s writing, without permission from anyone — at least so long as he cited the original source accurately.

So long as you cite, we believe you can take and build upon anybody’s work. Indeed, imagine what it would be like the other way round, imagine having to ask permission before you quoted someone’s work. Imagine how absurd it would be for my friend to call the Hemingway estate to ask for permission to quote Hemingway in his college essay. Imagine how absurd it would be, and then you would understand how you too believe writing and quoting are an essentially democratic form of expression. Democratic in the sense that we all take for granted the right to take, and use, other people’s work freely.

Argument

Think about writing or creating in a digital age. What should the freedom to write, or the freedom to quote, or the freedom to remix, in a digital age be?

In answering that question, notice the parallels with the stories that I told you.

As with the fight over Prohibition, right now in the United States, we are engaged in a war, the copyright wars, war which my friend, the late Jack Valenti, Head of the Motion Picture Association of America, used to refer to as his own “terrorist” war, where the terrorists in this war are our children.

As with the fight Souza was engaged in, this war is inspired by artists and an industry terrified that changes in technology will effect a radical change in how culture gets made.

And as with the war that led to prohibition, there is a fundamental question about these copyright wars that we need to raise: are the costs of this war greater than the benefits?

To answer that last question — in my view, the critical question — we have to think first about the benefits of copyright.

Copyright is a solution to a particular kind of problem. In my view, it is an essential solution to an unavoidable problem. Without the restriction on speech that copyright is, we would, paradoxically, have less speech. Copyright limits freedom, the freedom to unreservedly copy other people’s work, or compete with the original creator of creative work, in order to inspire more free speech. 115

We limit this freedom — through regulation — to give creators the incentive they need to create more free speech. But as with privacy, the right regulation is going to be a function of the technology of the time. As technology changes, the architecture of the right regulation will change as well. What made sense in one period will make no sense in another. Instead, we need to adjust the architecture of regulation, so the same value protected before in a different context can be protected now in the new context.

With copyright, what would that right regulation look like today?

I believe with Souza that we need to distinguish between the amateur and the professional, but recognise that we need a copyright system that encourages both. We need the incentives for the professional, but also freedom for the amateur.

How could we achieve that?

If we watch the evolution of digital technologies, we can begin to see how the law could cope with both.

Think of this evolution in two stages: The first stage begins around 2000. In this stage, digital technologies simply extend the read only culture from our past. Technologies that make it massively efficient to get and consume culture created elsewhere: Apple is the poster child of this vision of culture, with its iTunes music store, allowing you for 99 cents to download any song you want to your iPod (and only to your iPod), and in the United States, at least mark yourself as cool. This is the vision my colleague, Paul Goldstein, spoke of when he described the “celestial jukebox” — enabling you at any time, whenever you want, to access any culture you want.4 This is a critically important model for providing and supporting culture, facilitating an enormous diversity of culture, and the spread and support for culture. But it is just one model of culture supported by digital technology.

The second stage in this evolution begins around 2004. It is a revival of the readwrite culture from our past. The poster child for this image of culture is Wikipedia, and the enormous energy directed to that project. But I want to talk here about a slice of that culture that is distinct from Wikipedia — what I call “remix“.

Some examples will make the idea clear.

In the context of music: Everyone knows the White Album, created by the Beatles. That album inspired the Black Album, created by Jay-Z. That then inspired DJ Danger Mouse to produce the Grey Album. Four years later, Girl Talk sets the

116standard, mixing together hundreds of songs to produce a single album, Feed the Animals.

In the context of film: In 2004, the film Tarnation made its debut at Cannes. It was said by the BBC to “wow Cannes.” This was made with $218: A kid took video that he had shot through his whole life, and using an iMac given to him by a friend, remixed it in a way to wow Cannes and win the 2004 Los Angeles Film Festival.

Or finally, in the context of politics: Consider Will.I.Am’s work, taking the words of Obama and mixing them with music. Or still my favourite, think about the work of Johan Soderberg, mixing images of George Bush and Tony Blair, with the song, Endless Love.5

This is remix. But these are still examples of creativity which is in some way broadcast, though by using the Internet.

More interesting is the way that this platform has become a platform for communities to remix the work of other communities. You Tube has become the best example of this. Take, for example, Superman Day Parade, or Superman Retires, which mixes cartoon footage of a mature Superman, Wonderwoman, Birdman, Mr T and others, and dubs dialogue that involves Mr T challenging “old man” Superman to a fight, and propositioning Wonderwoman. This video inspired a Simpsons remix on You Tube, which inspired a Bambi remix video. Or one final example from You Tube: a performance of the Canon in D Major by Johann Pachelbel by Funtwo: This arrangement has been seen by more than 60 million people across the world, and more interestingly, it has inspired thousands of replications and remixes.

These remixes are conversations. They are the modern equivalent of what Souza was speaking of when he romanticised young people singing the songs of the day, or the old songs. But instead of gathering on the corner, or the back lawn, now people from around the world use this digital platform to engage in a form of read-write creativity, powerful and original and (to anyone who will listen), inspirational.

The importance in this has nothing to do with the particular technique: for the techniques have been available since the beginning of film or recorded music. The importance is that the technique has been democratised. It is the fact that anybody with access to a $1500 computer can make sounds and images that remix the

117culture around him or her and spread them broadly in ways that speak more powerfully to a younger generation than any words could.

And here then is the key linking back to my first story.

This is “writing” in the 21st century. It is not the “writing” that most of us do. Most of us write with words and sentences — this essay, for example. But that sort of “writing” in the 21st century will be the equivalent of Latin in the Middle Ages. Writing with images, sounds and video in the 21st century is the writing of the “vulgar.” They engage in it and if we ignore it, they, the vulgar, ignore us.

Yet here’s the problem with this new way of writing: The norms and law from the 20th century, as applied to this “writing” in the 21st century, are different. The norms that we apply to media are different from the norms we apply to text. With respect to text, the freedom to quote is taken for granted. With media, the norms assume you need permission first.

Why did these norms develop and support such a difference in freedom? Again, the reason is technical. If you look at the architecture of copyright law, and the architecture of digital technologies, the reasons are clear. The architecture of copyright law triggers its regulation on the production of something called a “copy.” The architecture of digital technology says every single time you use culture you produce a copy. This is a radical change in the scope and reach of copyright law, for copyright law never purported to regulate every use of culture.

Think about this point in the context of a book. Many uses of a book are simply unregulated by the law. To read a book is not a fair use of the book. It is a free use of the book, because to read a book is not to produce a copy. To give someone a book is not a fair use of the book, it is a free use of the book, because again, to give someone a book is not to produce a copy. To sell a book under the American copyright scheme is specifically exempted from the reach of the copyright owner because to sell a book is not to produce a copy. To sleep on a book is in no jurisdiction anywhere in the world a copyright relevant use of the book, because to sleep on a book is not to produce a copy.

These unregulated uses are balanced by a set of important regulated uses, regulated so as to create the incentives necessary for authors to create great new works. To publish a book you need permission from the copyright owner because that monopoly right is deemed essential to create the incentive in some authors to create great new works.

And then in the American tradition, there is a slim sliver of exemptions from copyright law called fair use: uses which would have otherwise been regulated by 118the law, but which the law says are to remain free to encourage creativity or critique to build upon older work.

This balance between unregulated, regulated and fair uses gets radically changed when digital technologies are brought into the mix. Because now, every use produces a copy, and thus now, the balance between regulated and unregulated uses gets radically changed. Merely because the platform through which we get access to our culture has changed, the presumptive reach of copyright law has changed, thus rendering this read-write material presumptively illegal under the regime we inherit from the 20th century.

No one in any legislative body ever thought about this. There was no Act To Massively Regulate Every Creative Activity Act — anywhere. This is instead the unintended consequence of the interaction between these two architectures of regulation, copyright law and digital technologies.

This unintended consequence is what I think of as Problem 1 in the copyright wars. Law is out of sync with technology, and just as before with the Fourth Amendment, in my view, that law needs to be updated. Just as the Fourth Amendment needed to be updated to take account of new technologies, copyright law needs to be updated to take account of these new technologies.

Problem 2 is what people refer to as piracy, or peer-to-peer “piracy.” Here however, we must link to prohibitions. This is a war of prohibition, and this law of prohibition, like most wars of prohibition, has not worked, if by worked we mean reduced the “bad” behaviour. We have learned that kids who share files don’t read opinions of the United States Supreme Court. Here is a map of peer-to-peer file sharing in the United States. Here is the point where the Supreme Court declared this activity illegal, but we still see no drop off in the behaviour of peer-to-peer file sharing. Instead of reducing the bad behaviour, all this war has done is render a generation of criminals. This is Problem 2, a technology out of sync with the law, and just as with the Fourth Amendment, copyright needs an update to take care of this misapplication as well.

What we should do?

Abolitionism is growing among the denizens of digital culture. Copyright, in their view, may have been needed for a couple of hundred years. We don’t need it anymore. Other techniques (business models) and other technologies (digital rights management) provide all the “protection” creators need, on this view. Anything more is simply unnecessary government regulation. 119

I am not an abolitionist. But I do believe abolitionism will grow unless we find a way to update the law of copyright to better take into account new technology. We need a series of changes in law. I am going to outline two here.

First: the law has to give up its obsession with the “copy.” The idea of a law being triggered upon reproduction in the digital age is insane. Instead the law needs to focus on meaningful activities. “Copying,” in a digital age, is not meaning, meaningful.

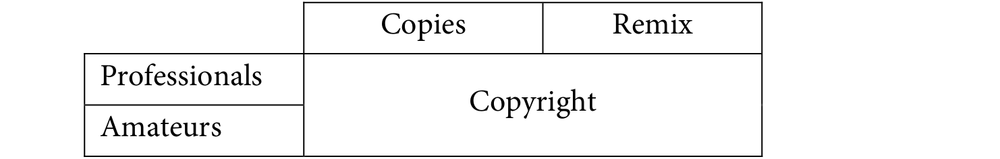

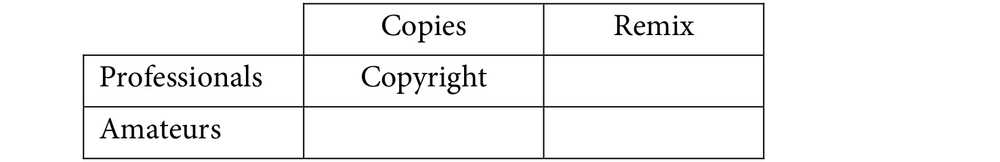

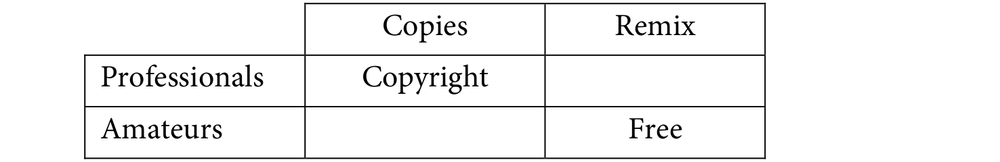

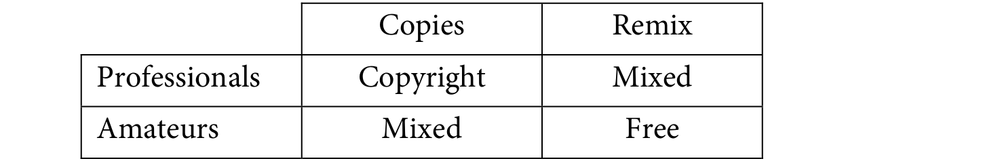

“Meaningful” in turn should be determined by the function of use. If we distinguish between copying and remixing, and between professionals and amateurs, we get something like this matrix.

The presumption of copyright law today is that all of this is regulated in the same way. Professional or amateur, copies or remix: it’s the same law that gets triggered. The first point to recognize: Never has the law of copyright purported to reach this broadly, and it makes no sense for the law to reach that broadly now.

Instead of course the law has to regulate efficiently here with professionals controlling the distribution of copies of their work. For if it doesn’t regulate efficiently here, then we can’t create the incentives that some professionals need to create their work.

120But equally clearly, amateurs remixing culture should be free of the regulation of copyright law. There should be a simple clear directive that this activity should be set free of any regulation, without needing a lawyer to provide an opinion that such use is “fair.”

In the middle, we have two harder cases — instances where the law has some important role in restricting use, but where that restriction must be balanced with important freedoms. Amateurs distributing copies of work should, to some degree, be privileged (I should be free to share my favourite song with my brother), but in some sense controlled (I should not be free to share my favourite song with my 10,000 best friends). Likewise, professionals involved in remix need the freedom to remix without requiring the permission of every copyright owner, but plainly, some derivative work is rightly owned by the copyright holder.

This map of reform is essentially libertarian. I am arguing for a fundamental deregulation of a significant space of our culture, and for focusing the regulation of copyright law in those areas where it can do some good. If we need regulation here, that regulation should at least demonstrate its necessity. Too much regulation is allowed to pass without any such demonstration.

Second: We need a change of law in the context of peer-to-peer piracy. We need to recognise that this decade-long war has been a failure. Some respond to failed wars by waging an ever more vicious campaign against the enemy. My response is to sue for peace, and find a better way to achieve the objectives of the war. The objectives of this war are to compensate creators for the exploitation of their work. We can provide that compensation without waging war against our kids.

For the last decade, many of us here have been bouncing around from hearing many decent proposals to address this fundamental problem, compulsory licenses to the voluntary collective licenses that the Electronic Frontier Foundation has proposed. All of these proposals seek to compensate the artist for the exploitation of her work without also breaking the Internet.

When we reflect on these proposals, here’s the point I want you to see: if we had enacted any one of these proposals into law one decade ago, the world today would be very different, in very tangible ways: 121

1. Artists would have more money. The current campaign to sue peer-to-peer “pirates” has given nothing of value to artists. When students are sued by the RIAA in America, artists get nothing from those lawsuits. Instead, the money simply funds further lawsuits, which means, the money simply goes to the lawyers. Whatever copyright law is for, it is not to provide a full employment act for lawyers.

2. Businesses would have enjoyed more competition and more opportunity for innovation. If the rules had been clearer at the start of this last decade, then more companies than Apple could have stepped in to figure out how to exploit this opportunity for spreading culture more broadly.

3. And certainly most important by a mile: If we had enacted these proposals a decade ago, we would not have raised a generation of “criminals.” As it is, we have millions of kids who have spent the last decade engaging in activities that they are told is criminal, but that in their own head seems as sensible as any behaviour that any normal person who “gets it” engages in. That creates a dissonance. That dissonance is a cost. It is a tax on their soul, as it alienates them from doing what’s right.

When you weigh these different factors — profit to record companies on one side, and gains to artists, business, and the souls of our kids on the other — I suggest the cost of this war to this generation is high enough to force us to adopt a different way to secure the promise of copyright in the 21st century.

In Europe we see this battle being fought in a very distinctive way. In France, we have recently seen the consideration of a 3-Strikes proposal, which basically says “Violate copyright law three times and your ISP has an obligation to kick you off the internet.” By contrast, Germany is now considering the Green Party’s proposal of a cultural “flat rate,” under which everyone pays a given amount in exchange for legalising non-commercial peer-to-peer sharing of copyrighted material.

That contrast, in my view, frames the contrast of choices that we are facing around the world. The 3-Strikes proposal is the American response to hopeless wars — waging an ever more effective war against the enemy. The German cultural flat rate is a response that recognises that this war of prohibition has failed, and that we need a different way to secure the objectives of copyright: to ensure copyright owners get compensated for the use of their work.

Australia and New Zealand have an enormously important role to play in that debate. Of course, New Zealand has recently considered and rejected the 3-Strike proposal and at least is speaking about a fundamental reconsideration about the 122way copyright law regulates in the 21st century. There is also here in Australia, a significant question about the way copyright law will regulate in the future.

My plea to you today is that you recognise the leadership you could play in this debate, and that you direct that leadership not to figuring out ever more fancy weapons to use against our kids, but to push all of us, and especially those of us in the United States, towards a position of sanity and sensibility for copyright in the 21st century.

* * *

I had the opportunity to speak at a conference at the Association of the Bar of the City of New York. The conference was held in a beautiful room, with luxurious red velvet curtains and a plush red carpet. The aim of the conference was to explain to creators how they could comply with the law of copyright, and how they could rely upon the law of fair use.

The law of fair use offers four factors that must be weighed by a judge before the judge can conclude that a particular use was “fair.” The lawyers organising the event decided that they would ask four lawyers to speak for 15 minutes each on each of the four factors — on the theory, I take it, that at the end of the hour the audience would be educated about fair use, and could go forward and create consistent with the law.

As I sat there and looked out at the audience, it wasn’t an understanding that I saw. It was total confusion. That confusion then led me to a day-dream about the event, and about its purpose.

Because as I looked around the room, I kept asking myself what that room remind me of. And eventually, it dawned on me. As a college student, I had spent a lot of time travelling throughout Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. That room, I realised, reminded me of the soviet parliament. And that led me to ask:

When was it in the history of the Soviet system when you could have convinced the Soviets that their system had failed? 1976 was too early, as it was puttering along okay in 1976. 1989 was too late: If you didn’t get it by 1989, you were never going to get it. So when was it, between 1976 and 1989, that you could have convinced them that the system had failed and, more importantly, what could you have said to these Soviets to convince them that the ideology that they had romanticised had crashed and burned, and to continue with the Soviet system was to betray a certain kind of insanity. 123

Because, as I listen to lawyers insist that “nothing had changed,” and that “the same rules should apply,” and that “it is the pirates who are the deviants,” I recognised that it is we, lawyers, who are insane.

This existing system of copyright could never work in the digital age. Either it will force kids to stop creating, or it will force upon the system a revolution. In my view, both options are not acceptable.

Extremism invites extremism in response. And the extremism of the rights holders today has created the extremism of abolitionism. I think both extremes are wrong. Thus in this war, I am Gorbachev, not Yeltsin: an old communist who’s trying to preserve this old system in a new time against extremisms from both sides. Extremisms that would destroy the system of copyright that we have inherited.

Some of you might not care about destroying the system of copyright. So then allow me one final plea: We have to recognise this: We can’t kill this form of creativity; we can only criminalise it. There is no way we can stop our kids from engaging in this form of creativity; we can only drive their creativity underground. We can’t make them passive; we can only make them “pirates.” The question we have to ask is, is that any good? In my country, kids live in an age of prohibition, constantly living their life against the law. We need to recognise: that life is corrosive, and corrupting to the rule of law, at least the rule of law in a democracy.

That is a cost of this war. In my view, it is large enough to say that our first moral obligation must be to find a way to stop this war. Now.

Thank you very much.

1 Professor Lawrence Lessig is Director of the Edmund J Safra Foundation Center for Ethics at Harvard University, a Professor of Law at Harvard Law School and former Professor of Law at Stanford Law School. He is a founder of the Creative Commons organisation, which enables copyright holders to license their work online for primarily non-commercial purposes, and Change Congress, an organisation dedicated to changing the system that requires members of Congress to solicit private donations in order to fund election campaigns. Professor Lessig is perhaps the world’s most famous exponent, and critic, of copyright policy in the United States. He has written seminal works on information policy, focusing on the social and economic effect of government regulation of the use of digital communications technology. He has written several seminal works, including Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace (1999) and Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy (2008).

2 Huxley, Aldous, The Doors of Perception Harper & Bros, 1954.

3 Olmstead v United States 277 US 438 (1928). The Supreme Court considered whether police wiretapping of the telephone of a bootlegger, Roy Olmstead, violated rights of privacy and against self-incrimination protected by the fourth and fifth amendments of the Constitution. The Court upheld Olmstead’s conviction for bootlegging and he served a four year prison sentence.

4 Paul Goldstein published Copyright’s Highway: From Gutenberg to the Celestial Jukebox (Stanford University Press) in 2003.

5 Soderberg remixed audiovisual material to create a 2003 video of George Bush and Tony Blair ostensibly serenading each other with the words of Endless Love, the duet performed by Lionel Richie and Diana Ross. Posted on You Tube in 2007 the video became a viral sensation.