CHAPTER 6

ARTEFACT ANALYSIS

Archaeological excavations at Chinaman’s Point were conducted to obtain a representative sample of the material remains at the site. Through these remains information was sought on the methods the Chinese fish curers used to sustain a livelihood, the domestic and industrial equipment required, their living conditions, consumption patterns and recreational activities.

The excavated areas revealed a mix of industrial and domestic artefacts, although different areas of activity were apparent through artefact types and distribution densities. The recovered artefacts include deliberately discarded and accidentally lost industrial and domestic items. While some were located in a simple, single, in situ ground layer; others had eroded from ground layers of the site through wave action and been deposited within the site’s tidal zone. None of the domestic remains could be directly connected to individual site occupants – known through historical documents – and therefore no attempt has been made to compare and contrast domestic artefacts to ascertain individual ownership or distinguish the roles of individuals.

As this research is the first of its kind in Australia, the industrial components from Chinaman’s Point cannot be compared or contrasted with a similar body of material remains. Therefore, for the purpose of this research, the industrial remains from Chinaman’s Point will be considered a standard collection of artefacts for a colonial Australian Chinese fish-curing site. The domestic artefact types from Chinaman’s Point were found to be consistent with Australian colonial-period urban and rural overseas Chinese sites, enabling a good level of comparative analysis. The site’s small size and isolation assists to provide a snapshot of a Chinese community in colonial Australia separate (but interlinked) to the overseas Chinese mining industry.

ARTEFACT COLLECTORS

With the erosion of the bank at Chinaman’s Point described in chapter 5 and the subsequent depositing of artefacts onto the tidal zone, thousands of artefacts became exposed to artefact collectors. People also retrieved artefacts by digging at the banks of the site. A walk through the residential streets of Port Albert reveals a myriad of Chinese style artefacts prominently displayed in kitchen and living room windows and in one case, hanging from a front-yard sculpture. Unusual looking objects, unbroken items and artefacts displaying Chinese characters would likely have been the first pieces collected. This is reflected in the poor representation of these artefact types recovered archaeologically from Chinaman’s Point. Artefact collecting at Chinaman’s Point has resulted in the loss of much scientific information and has made site interpretation difficult, especially in terms of estimating site population and gaining an understanding of how prolific certain industrial, domestic and recreational activities may have been.

ANALYSIS METHODOLOGY

The artefact classification system devised for this project is based partly on the very adaptable historical artefact management tools presented in The Canada Parks Service Classification System for Historical Collections (1992) and partly on the artefact typology guide in Orser (1988: 233). To further aid in developing an appropriate classification system and to describe and archaeologically interpret artefacts from the Chinaman’s Point site, a number of other artefact cataloguing and analysis guides were consulted, including South (1977), Sprague (1980–81), Davies & Buckley (1987), Orser (1989), Praetzellis & Praetzellis (1990), Adams & Adams (1991), Crook, Lawrence & Gibbs (2002), Casey (2004), Brooks (2005a; 2005b) and Crook (2005).

The artefact analysis aims to describe artefacts in a complete and organised manner, so that artefacts or groups of artefacts can be broken into variables that permit both a detailed analysis of the artefact assemblage – such as an individual tools usage or a description of fishing methods – and broad analysis – such as site demographics, activity areas or structural layout. The analysis also aims to identify artefacts of significance for more comprehensive examination. This will facilitate an understanding of the broader social and cultural framework of the assemblage and assist in an understanding of the people at Chinaman’s Point.

The artefact classification system is broadly functional, concentrating mainly on material and form (rather than a fabric-based analysis) to interpret primary original artefact use. Detailed examinations of artefact attributes, manufacturing technologies and post-manufacture modifications have also in some cases been used to determine site occupation periods and possible artefact re-use functions (i.e. when artefacts were used other 88than for their original purpose). To identify the artefacts from Chinaman’s Point, seven functional artefact categories are defined, each of which includes a number of more narrow sub-categories.

The categories are:

- Architectural/Structural. Artefacts originally created for the purpose of constructing dwellings or site features. Sub-category: fastener and construction material.

- Domestic. Artefacts originally created for the purpose of procurement, preparation and service of daily human food requirements and personal comfort. Sub-category: cooking, food, food storage, furnishing, liquid storage and tableware.

- Industrial. Artefacts originally created for the purpose of procuring and processing marine resources. Sub-category: fishing, recording, slag, tools.

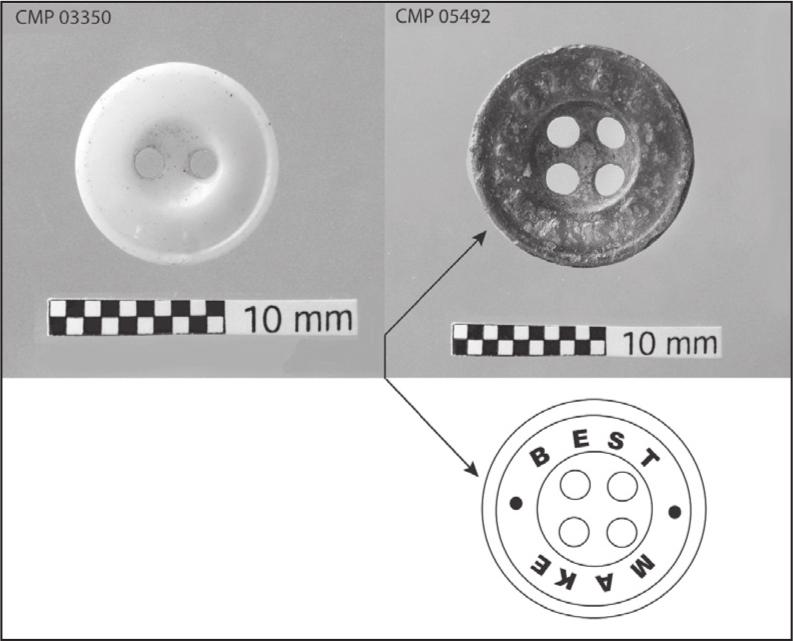

- Personal: artefacts originally created for individual human use such as clothing and associated objects. Sub-category: button.

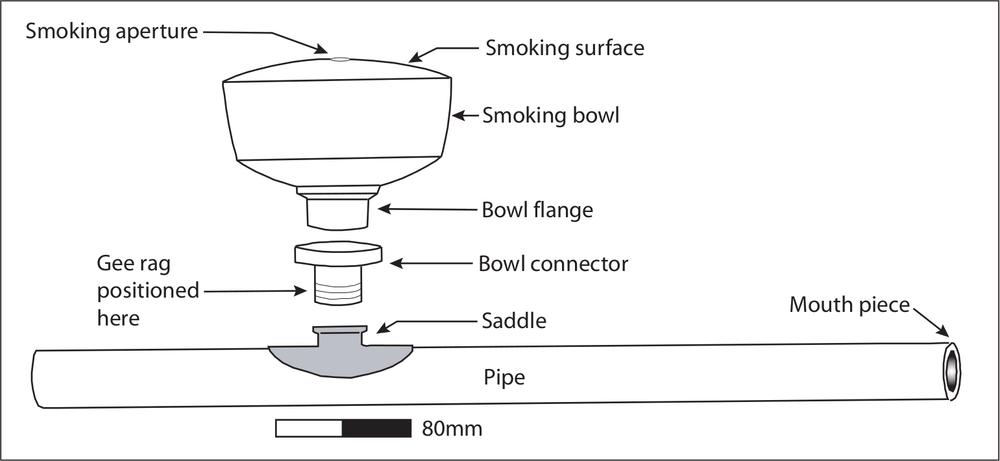

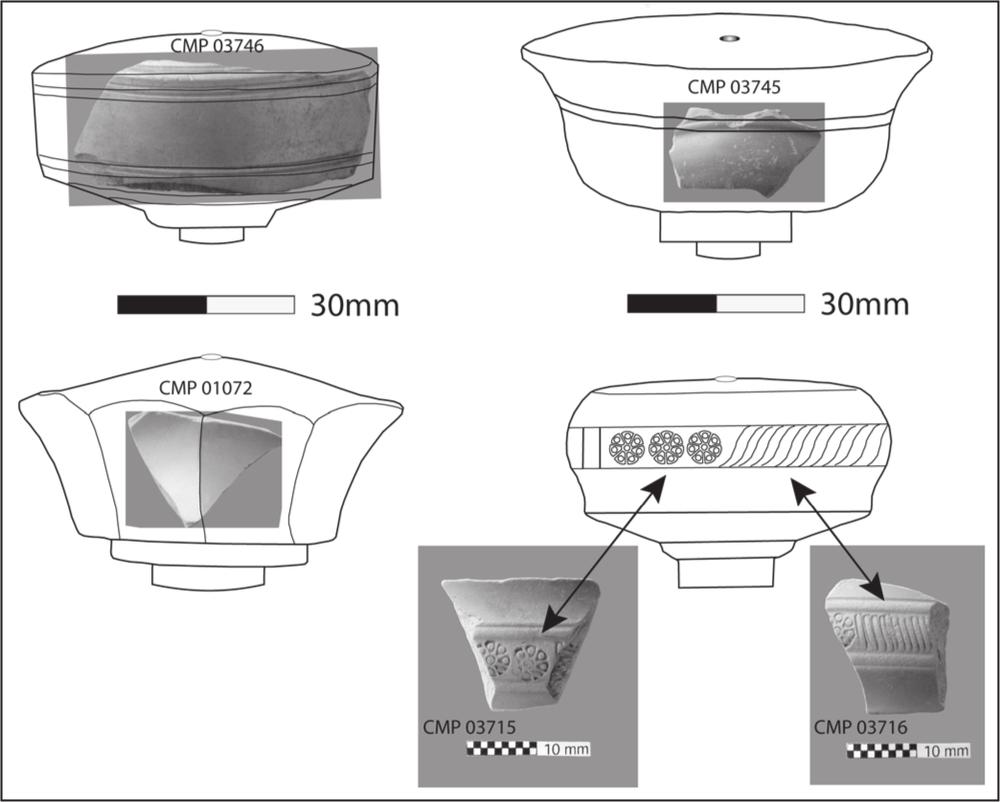

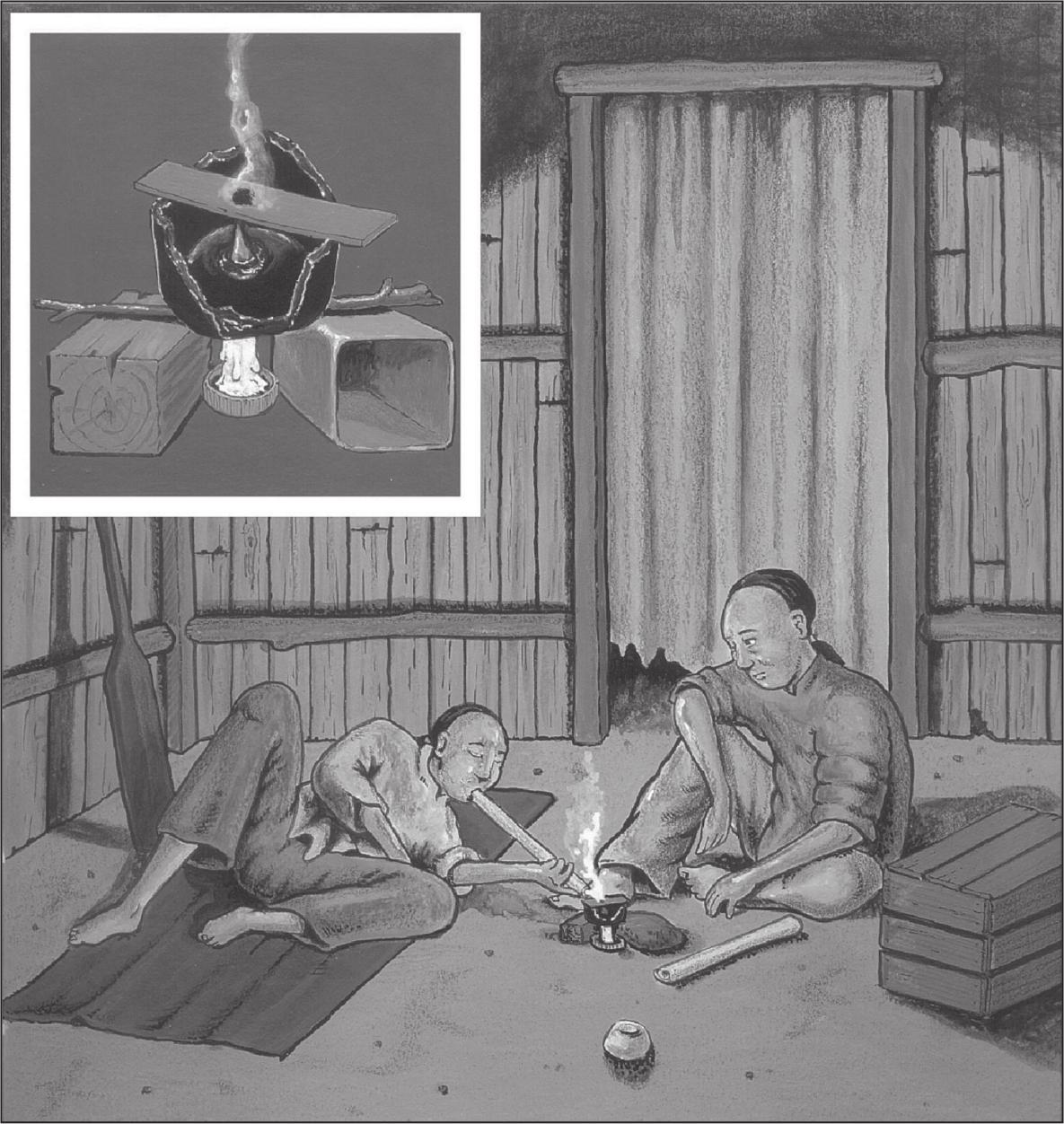

- Recreational. Artefacts originally created for individual or group enjoyment. Sub-category: opium smoking.

- Unidentified. Artefacts originally or subsequently created to serve a purpose that cannot now be determined. Sub-category: unidentified artefacts.

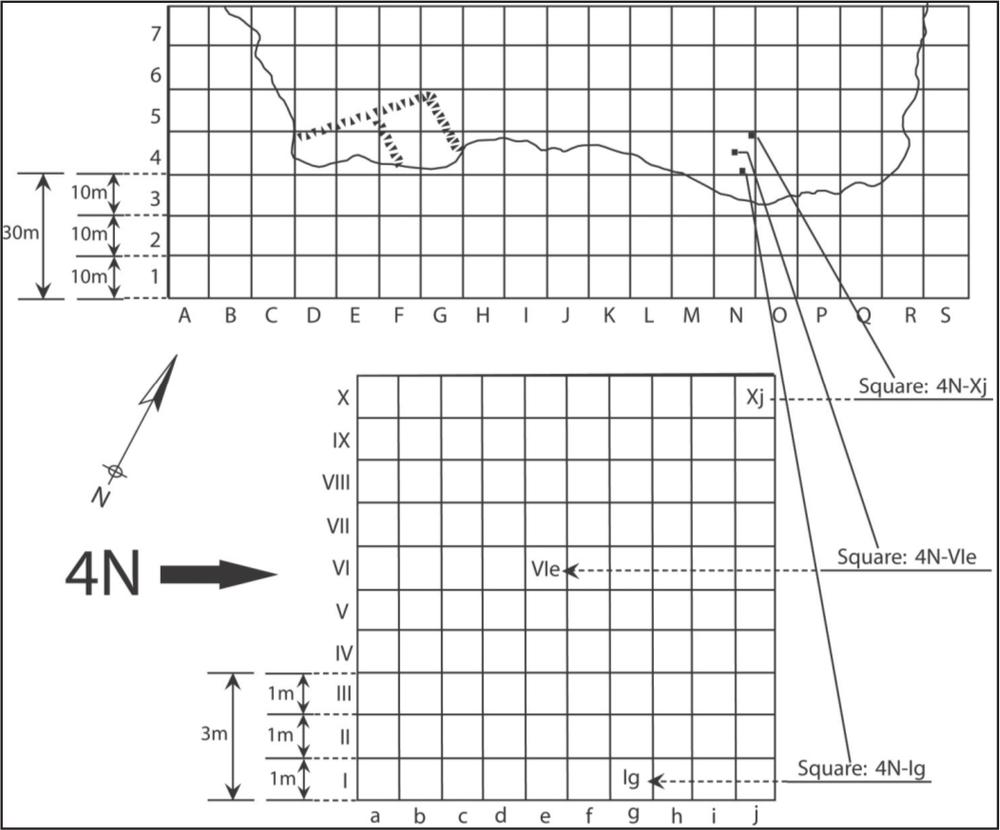

Recovered artefacts were cleaned in the field and bulk-bagged with other artefacts of the same fabric, grid square and stratigraphical layer. Bulk bags were assigned a five part identification code e.g. CMP-4G-IXh-2-3, where CMP represents Chinaman’s Point, 4G the ten-by-ten metre grid square, IXh the one-by-one metre grid square, 2 the spit number and 3 the stratigraphical ground layer (figure 6.1). Bags were clearly labelled using waterproof, indelible, black pen (Artline Drawing System EK-238) on Tyvek waterproof labels. Complete or diagnostic items were separately bagged and tagged. Labels were placed inside artefact bags, or for objects such as bottles the labels were tied to the object with fine cotton string.

Figure 6.1 Site grid (top) and one-by-one metre breakdown (bottom) used for artefact province details.

Due to the site’s coastal environment, recovered artefacts had been impregnated by salt and required salt leaching. Under the direction of Heritage Victoria’s conservation department, artefacts were placed in synthetic mesh bags and immersed in fresh tap-water. Water was changed fortnightly from the time of recovery until the water the artefact was in had achieved a salt content reading of 20 parts per million or below. The final water change was conducted using purified water in which artefacts were submerged for another four-week period. Consequently, all artefacts were immersed in fresh water for approximately ten months. To ensure artefacts did not become damaged during transportation from the field and storage, plastic water-filled tubs were packed loosely with bagged artefacts and fitted with a strong lid. Wet polyethylene was used to cushion any loose and/or fragile artefacts.

Artefact cataloguing and analyses were conducted at La Trobe University’s archaeological laboratories. In the laboratory, each artefact was reassessed and assigned a new double-sided tag. This tag displays the grid square and stratigraphic layer on one side and a Chinaman’s Point accession catalogue number on the 89other side. After this was completed and conjoins between artefacts made where possible, all artefacts were placed in numbered archival Corflute boxes and submitted to Heritage Victoria’s conservation laboratory in Abbotsford, Melbourne, where some significant artefacts underwent further conservation treatment and others went into storage.

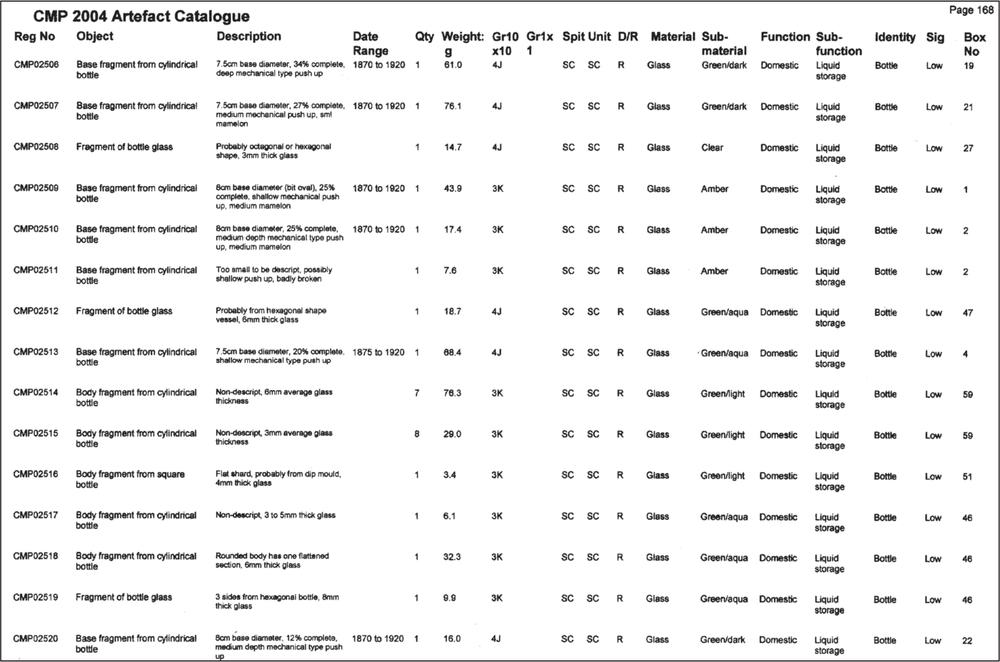

Artefact information has been recorded in an accession catalogue using a Microsoft Access database. Each database entry includes the artefact number, object, an artefact description, date range (where possible), quantity, weight, province, material, sub-material, function, sub-function, identity, significance (site and state) and the archival box number (figure 6.2). For consistency in catalogue entries, drop down tables were developed within the database according to category. To facilitate artefact identification and retrieval, the accession catalogue was designed to allow all artefact entries – besides the general description – to be searched in individual fields. This also enables artefact properties to be broken into variables for detailed and complex queries – such as only white ware ceramic rim fragments with 50 mm diameters or broad levels of analysis – such as all ceramic of a certain ware.

Figure 6.2 One-page example of the Chinaman’s Point artefact catalogue.

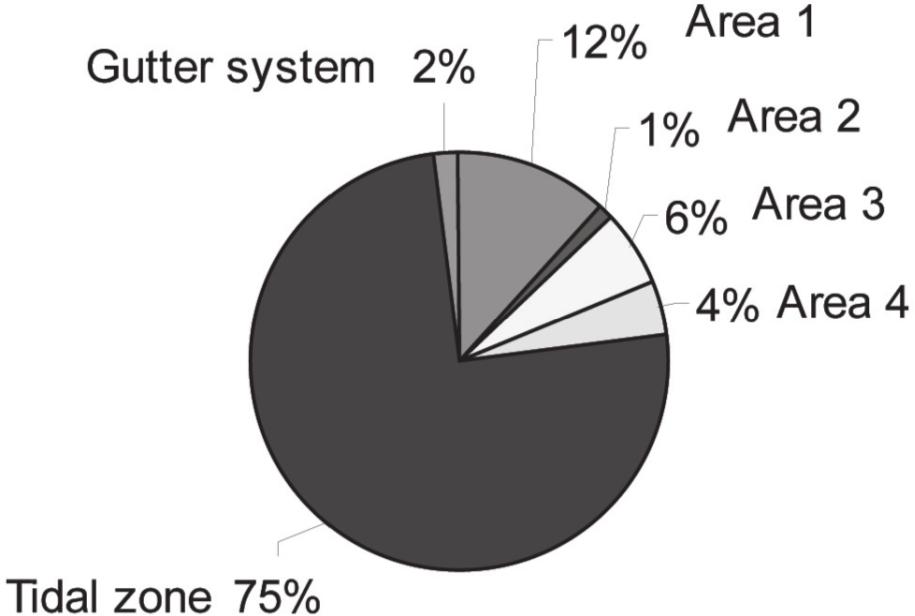

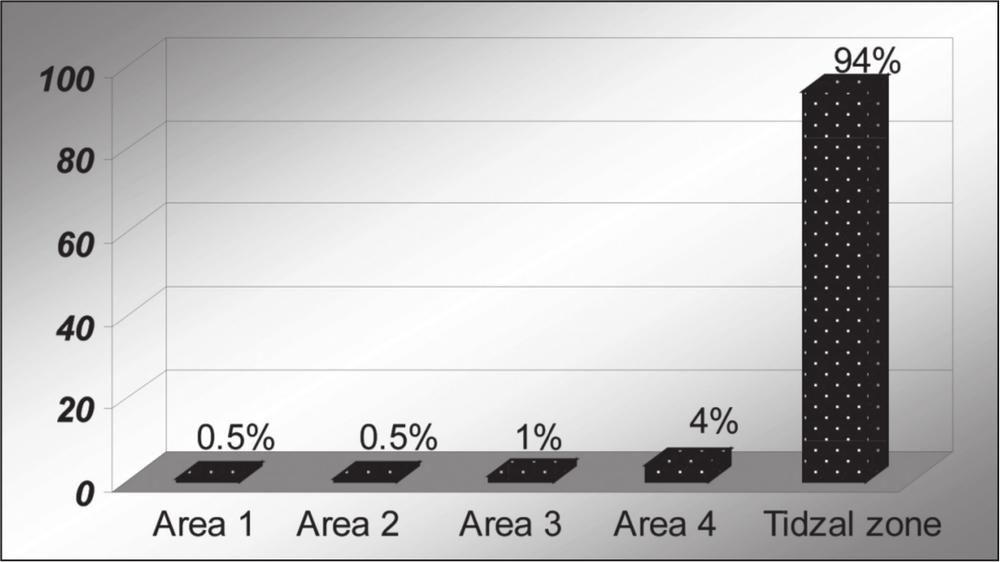

In total, 29 030 separate artefact fragments, weighing 234.655 kg and representing 6335 accession catalogue entries were recovered from the site. The majority of artefacts – 21 838 artefacts, weighing 211.479 kg – came from surface collections conducted on the tidal area of the site (the tidal zone). The remaining 7192 artefacts – weighing 23.176 kg – were excavated from sub-surface ground layers. Twelve separate artefact materials are present in the assemblage: bone, brass, ceramic, copper, ferrous metals, glass, lead, leather, mortar, shell, slate and wood. The term sherd is used in conjunction with ceramics fragments and the term shard is used when referring to glass fragments. A breakdown of artefact material types, numbers and weight is in table 6.1. Artefact densities can be seen in table 6.2. 90

| Materials | Number of artefact fragments | Weight (grams) |

|---|---|---|

| Bone | 56 | 560 |

| Brass | 2 | 17 |

| Ceramic | 3110 | 14 298 |

| Copper | 41 | 79 |

| Ferrous metal | 11 825 | 42 780 |

| Glass | 13 660 | 17 4872 |

| Lead | 29 | 589 |

| Leather | 2 | 5 |

| Mortar | 6 | 16 |

| Shell | 10 | 87 |

| Slate | 6 | 12 |

| Wood | 283 | 1340 |

| Total | 29 030 | 23 4655 |

Table 6.1 Breakdown of artefact material types, numbers and weight.

Table 6.2 Chinaman’s Point site artefact densities.

ARCHITECTURAL/STRUCTURAL

Fasteners

Nails were the dominant type of fastener recovered from Chinaman’s Point, although screws, spikes and washers were also found. Corrosion from the harsh marine environment hampered the identification and accurate sizing of many of the recovered nails. The largest nail size was approximately 75 mm long and 6 mm diameter – with diameter the most important determining factor. Smooth shaft ferrous metal fasteners exceeding these dimensions are classified as spikes. Two square shaft tack nails were recovered from the tidal zone, both approximately 25 mm long; one has a two facet chisel point and the other a four facet point. Two 25 mm diameter, machine-made, lead washers were also located in the tidal zone and could be associated with either boat maintenance or roofing nails.

Due to high levels of corrosion, some ferrous metal artefacts were deemed to have little or no archaeological value. It would be impractical to conserve and retain such artefacts. A sampling strategy that involved identifying and retaining the least corroded and most archaeologically informative pieces was employed to deal with the unidentifiable heavily corroded material. This resulted in a retention rate of approximately eight percent of metals. A percentage breakdown of retained and discarded metals can be seen in table 6.3. 91

| Metal form | Number of artefact fragments | Weight (grams) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nail | 319 | 1107 | 100 |

| Nail (retained) | 21 | 104 | 6.6 |

| Nail (discarded) | 298 | 1003 | 93.4 |

| Spike | 59 | 2992 | 100 |

| Spike (retained) | 7 | 557 | 11.9 |

| Spike (discarded) | 52 | 2435 | 88.1 |

| Screw | 8 | 103 | 100 |

| Rivet | 62 | 2231 | 100 |

| Rivet (retained) | 27 | 978 | 43.5 |

| Rivet (discarded) | 35 | 1253 | 56.5 |

| Cask strap | 2056 | 13 100 | 100 |

| Cask (retained) | 44 | 1016 | 2.1 |

| Cask (discarded) | 2012 | 12 084 | 97.9 |

| Cooking pot | 107 | 5440 | 100 |

| Drum plug | 65 | 122 | 100 |

| Drum rim | 20 | 113 | 100 |

| Lead | 29 | 589 | 100 |

| Slag | 279 | 754 | 100 |

| Slag (retained) | 4 | 14 | 1.4 |

| Slag (discarded) | 275 | 740 | 98.6 |

| Unidentifiable | 9286 | 16 229 | 100 |

| Unid. (retained) | 150 | 204 | 1.8 |

| Unid. (discarded) | 9136 | 16 025 | 98.2 |

| Total (retained) | 578 | 12 418 | 5.1 |

| Total (discarded) | 10 689 | 32 518 | 94.9 |

| Total | 12 290 | 42 780 | 100 |

Table 6.3 Breakdown of retained and discarded metals (Unid = Unidentifiable).

Nails (ferrous)

There are two problems in accurately dating nails recovered from historical sites in Australia. First, although a manufacture date can be roughly established from physical features, builders often held an initial prejudice against new nail types. This has created a time gap from when historical records demonstrate a nail was available, to when it was actually used in Australian structures. Second, due to the high price and scarcity of nails, builders often took nails from abandoned structures to re-use, creating a confusing chronological marker (Varman 1993: 182). Nonetheless, nails have proved to be one of the most common artefacts recovered from historical sites in Australia and are an important means of gathering historical archaeological information (Michael 1974: 99; Middleton 2005: 55, 61).

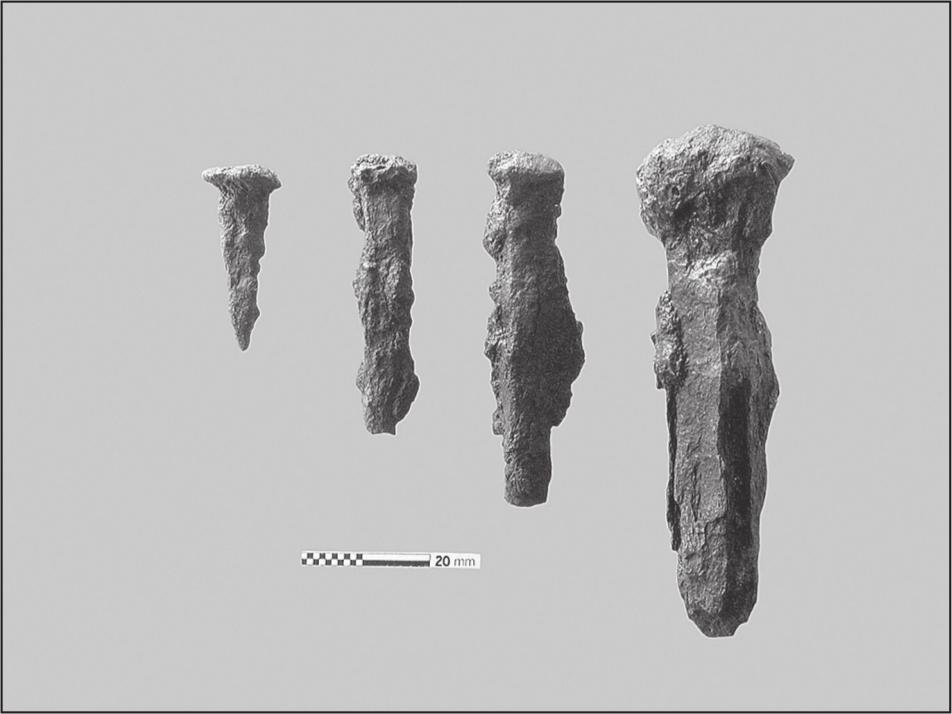

From 319 recovered iron nails, 233 are so corroded that identification to a specific type is not possible. The remaining 76 nails are recognisable and datable. Twenty are square/rectangle shaft, cut plate, rose head type nails that date from the 1840s until the 1870s (figure 6.3). The remaining 56 are hard drawn, round shaft, wire rose head type nails that date from 1853 to the 1890s (Varman 1980: 108) (table 6.4).

Spatially, the majority of nails were recovered east of square 3G within the tidal zone at Chinaman’s Point. Excavated nails areas were centralised around 4G in area 3 and 4H of area 4, suggesting possible workshop areas or the position of a perished structure. 92

Figure 6.3 Square shaft, cut plate, rose head nails from the Chinaman’s Point site.

| Metal fasteners | MNI | Site location |

|---|---|---|

| Square shaft rose head (retained) | 7 | area 4; TZ |

| Square shaft rose head (discarded) | 13 | area 4; TZ |

| Round shaft rose head (retained) | 6 | area 4; TZ |

| Round shaft rose head (discarded) | 50 | area 4; TZ |

| Unidentifiable nail (discarded) | 233 | area 4; TZ |

| Spike (retained) | 7 | area 4; TZ |

| Spike (discarded) | 52 | area 4; TZ |

| Tack | 2 | area 4; TZ |

| Screw | 8 | area 4; TZ |

| Washer (lead) | 2 | TZ |

| Total discard | 348 | area 4; TZ |

| Total retain | 40 | area 4; TZ |

| Total | 388 | N/A |

Table 6.4 Minimum number of metal fasteners (MNI = minimun number of individuals; TZ = tidal zone).

Screws

Eight screws are present in the assemblage. One is made of brass and the others are heavily corroded iron screws; all are designed to fasten into timber materials. Screw sizes range from 28 to 68 mm long and from 4 to 8 mm in diameter. These are standard type wood screws with a multitude of timber fastening applications such as securing internal or external shelving, frames, hinges and brackets.

Six screws were recovered from the tidal zone within squares 3G and 3P of the site grid. The remaining two screws – including the brass one – were excavated from area 4 of the site, one in the central region of area 4. Thus, the screws have very similar spatial positions to the recovered nails.

Spikes

Fifty-nine ferrous metal spikes were recovered. Thirty-eight of these have a square shaft that tapers to a two facet chisel point, with 12 of the 38 displaying a rose type head. Six of the spikes have round shafts with four facet points and unidentifiable heads; the remaining 15 spikes are too heavily corroded to have their attributes accurately recorded. All spikes range between 40 and 220 mm in length and 8 to 20 mm in diameter.

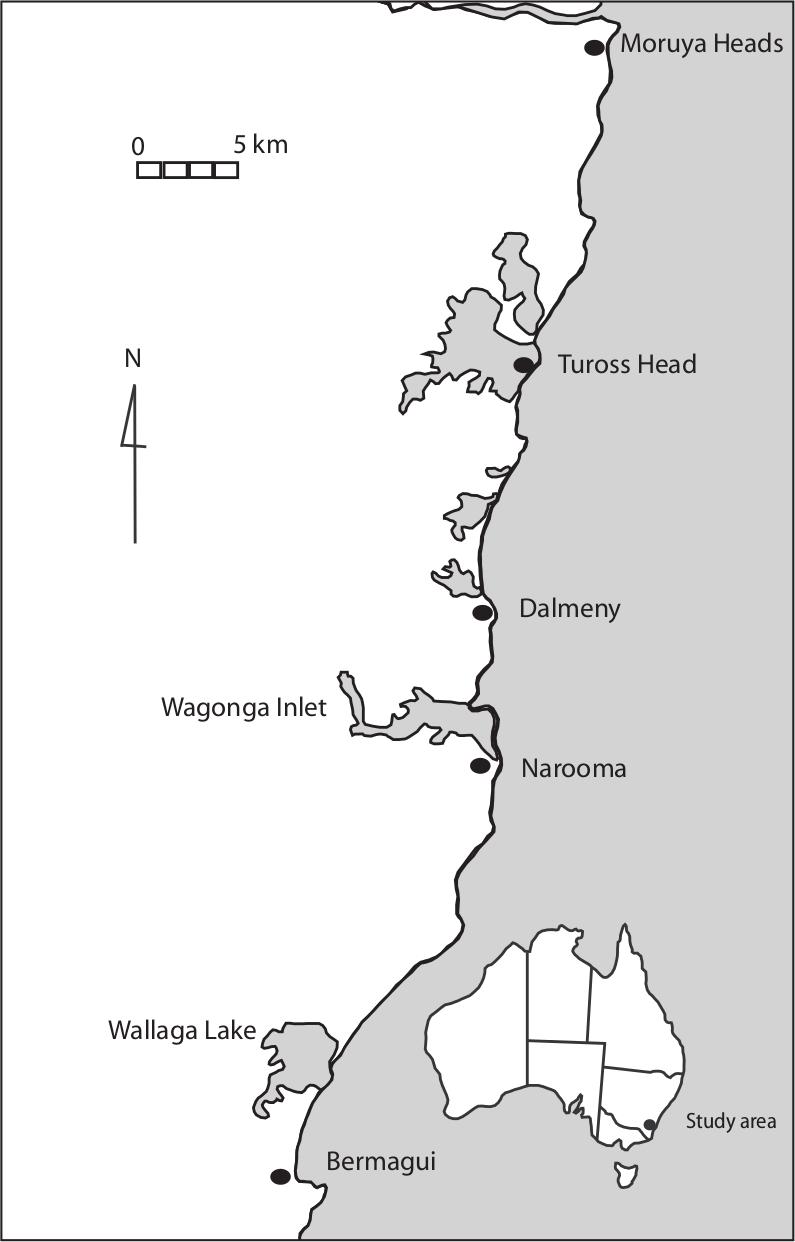

On the South Coast of New South Wales, between Moruya and Bermagui (figure 6.4), Bowen (1999: 64; 2003: 12) noted that spikes were commonly used by commercial fishermen to fasten together slipway timbers. Maintenance of boats is an ongoing task for any commercial fishing operation. Slipways were used to hold a boat out of water for maintenance purposes, necessary on average every six months. To construct a slipway, bearer timbers were placed parallel to the shore from below low tide mark to well above high tide mark. These were morticed to cradle timbers at a right angle to bearers and held together by steel spikes. 93

Figure 6.4 Location map for Moruya to Bermagui, South Coast, New South Wales.

Although no timber remains of a slipway are visible at Chinaman’s Point, the recovery of metal spikes at an establishment where fishing boats were almost certainly present suggests slipways were in use at the site. The metal spikes – of a similar size to those found on the South Coast of New South Wales – were recovered within a localised vicinity, slightly east of area 4 in the tidal zone.

Materials

A small representation of architectural and structural material was recovered from Chinaman’s Point including brick, timber post remains, lead sheeting and window glass. Timber post remains in area 1 and 3 and those associated with the jetty in the tidal zone have already been discussed in the site description section of chapter 5.

Bricks

With further settlement at Port Albert during the 1850s and 1860s, people desired permanent dwellings. To cater for this, a number of brick-making facilities were established in the region. For example, Henry Sherwood and Richard Huntington each operated a brick factory in the Tarraville area during the late 1850s and in the 1860s Samuel Taylor ran The Port Albert Brickworks located on the outskirts of town (Gippsland Guardian 1859, January 7; Gippsland Guardian 1860, September 21; Lennon 1975: 124).

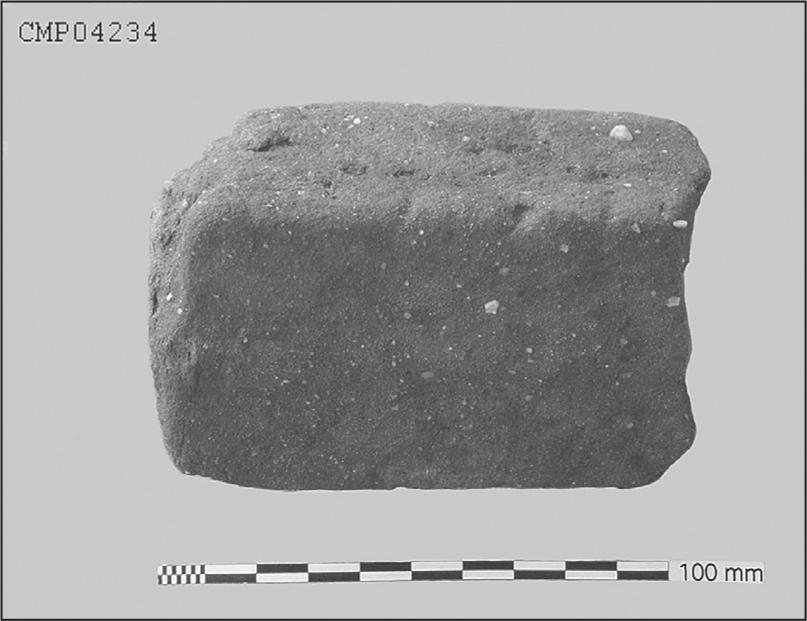

Twenty-two brick objects, weighing 2702 g and representing a minimum number of 18 bricks were recovered in a fragmentary, deteriorating and fragile condition from the Chinaman’s Point site. Most are hand moulded, uneven, poorly fired bricks of varying textures and range in colour from red/brown to orange/tan (figure 6.5). An estimate of the original brick sizes suggests their average square (head) end measurements were 75 mm thick by 100 mm wide. Length measurements were unobtainable. These dimensions do not match standard 19th-century British, American or Chinese brick sizes which were 65 thick by 115 mm wide (British), 55 mm thick by 100 mm wide (American) and 65 mm thick by 140 mm wide (Chinese) (Gurcke 1987: 118; Manson 1982: 13). Nineteenth-century Australian brick sizes did vary considerably (Stuart 2005: 83), however, as the standard brick sizes from other countries are not apparent in the sample from Chinaman’s Point and as bricks were available locally, the Chinaman’s Point bricks are probably not an imported variety. One brick fragment has a plain stamped frog or indent and is of superior manufacture quality – i.e. shows even firing – compared to the other recovered bricks. 94

Figure 6.5 Hand-moulded mud brick from the Chinaman’s Point site.

The brick of superior quality from the site is likely to have been manufactured at one of the region’s brick factories. The remaining poorer quality, non-standard sized bricks probably came from one of the informal, one-man brick-making operations that were also plentiful in the local vicinity (Adams 1990: 49, 120).

The bricks were not located in association with a hearth or other structural setting. Seven pieces were grouped together in the gutter system at the eastern end of square 5G. However, to function properly as a means of drainage, the gutter system would need to have been kept clear of obstructions, meaning these brick pieces probably represent displaced objects from the post-site occupation period. Three further brick pieces were excavated from area 4. The remaining 12 bricks portions were located randomly within the site’s tidal zone.

Lead sheet

Two pieces of lead sheeting weighing a total of 292.3 g were recovered from the tidal zone and area 4 of the site. Both are 1.5 mm thick, approximately 80 mm wide by 150 mm long and rectangular in shape and have a series of 3 mm diameter nail holes spaced evenly around their entire perimeter. These two artefacts probably acted as water-resisting measurers, i.e. for flashing, or as subsequent building repairs to weatherproof a structure.

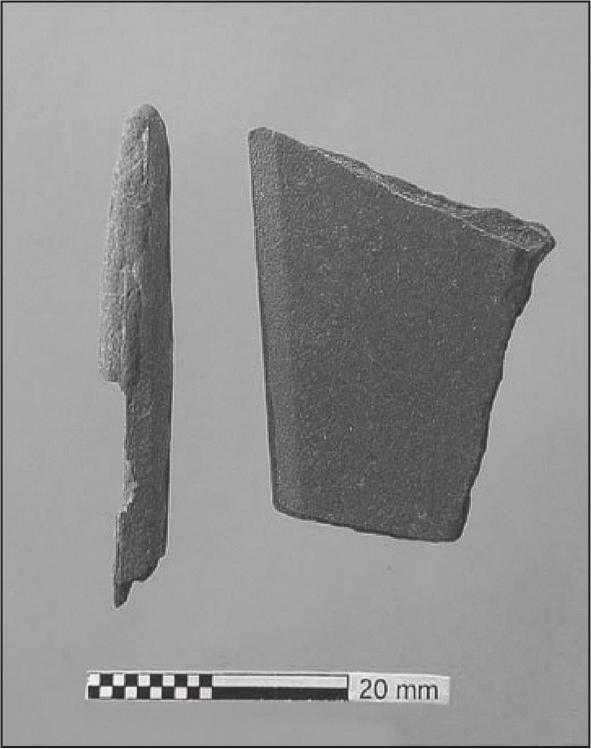

Window glass

One hundred and seven shards, weighing a total of 431 g and representing two types of window glass was recovered from the Chinaman’s Point site. Sixty-three shards are of the crown type window glass dating from 1800 to 1870 and 44 shards are of the improved flattened cylinder type window glass dating from 1834 to 1910 (Boow 1991: 100–02). Eighty-four shards were recovered from the tidal zone and 23 were excavated from area 4 (table 6.5). Evidence from other overseas Chinese sites in Australia (Smith 1998: 65–82), New Zealand (Ritchie 1986: 149) and the United States (Sisson 1993: 56), demonstrates that overseas Chinese dwellings were generally constructed without windows. Therefore, these artefacts are a variation to the typical overseas Chinese site and suggest the presence of at least one relatively permanent domestic structure, with windows, at Chinaman’s Point.

| Window | Type | Number of shards | Weight (grams) | Site location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqua tinge | Crown | 28 | 145 | area 4; TZ |

| Aqua tinge | Imp flat cylinder | 32 | 167 | area 4; TZ |

| Clear | Crown | 35 | 91 | area 4; TZ |

| Clear | Imp flat cylinder | 12 | 28 | area 4; TZ |

| Total | N/A | 107 | 431 | area 4; TZ |

Table 6.5 Window-glass type and amounts (TZ = tidal zone).

DOMESTIC

Domestic artefacts include those associated with cooking, food, food storage, furnishings, liquid storage and tableware. These artefact types make up a sizable proportion – 5108 catalogue entries, representing 17 381 95artefact fragments – of the Chinaman’s Point assemblage, principally due to the large amount of bottle glass and ceramic fragments recovered from the site.

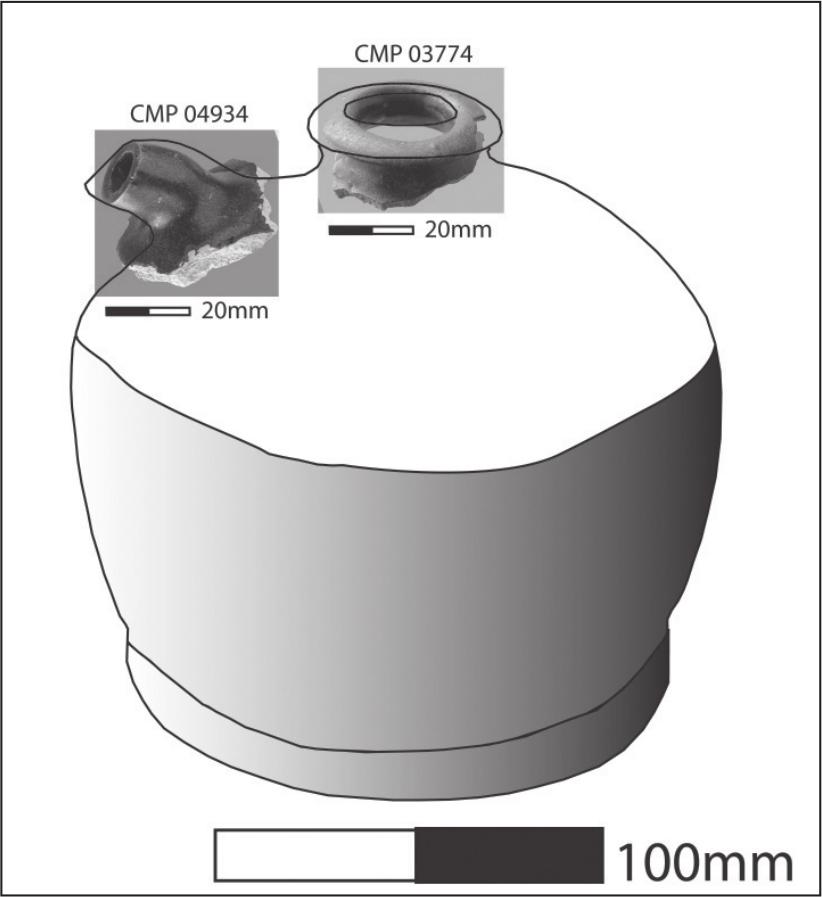

Cooking

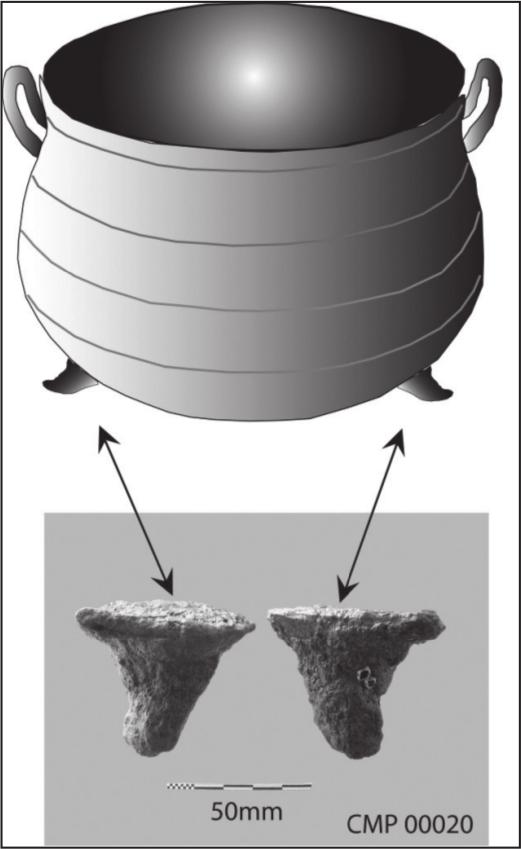

One hundred and seven metal objects, weighing 5440 g and including handles, rims, spouts, body fragments, base fragments, support legs and hooks were considered to be associated with metal cooking containers. All were recovered from within the tidal zone east of area 4 and are too corroded to enable even a rudimentary reconstruction through conjoining processes. There appear to be a minimum of two kettles, one cooking pot and one wok represented in the assemblage. There was no evidence of a cooking hearth, possibly due to erosion or to the common Chinese custom of using mobile clay stoves designed to allow easy removal upon site abandonment (Anderson & Anderson 1977: 365).

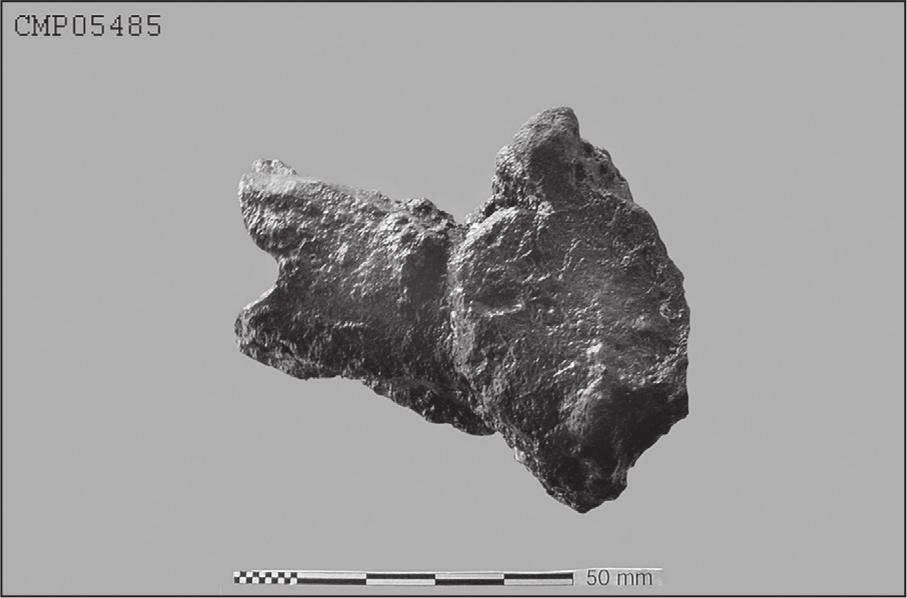

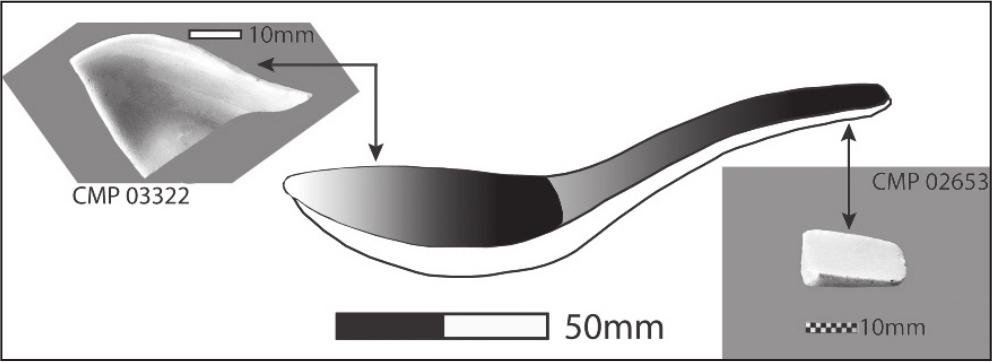

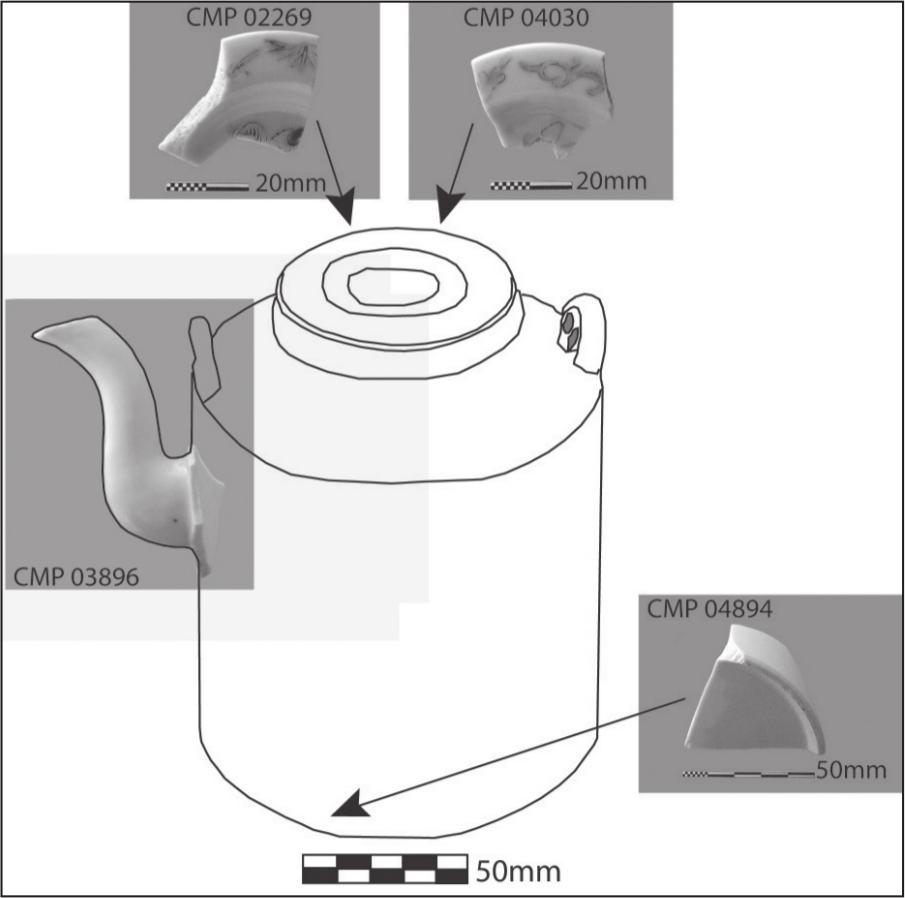

Containers

The two kettles were identified through the recovery of two pouring spouts. One spout is of a universal pouring design and may be attributed to a number of robust 19th-century cast iron kettle types (figure 6.6). The second spout is of a similar design, but appears even more robust in construction (figure 6.7). As no similar design has been located for European pouring implements, it is speculated through site association that this spout may be of Chinese origin.

Figure 6.6 Common 19th-century cast iron spout from the Chinaman’s Point site and the type of kettle it most likely represents.

Figure 6.7 Robust pouring spout from the Chinaman’s Point site, possibly of Chinese design and origin.

The thickness of the corroded metal enabled the cooking pot and kettle body fragments (6 to 12 mm thick) to be distinguished from the wok fragments which are approximately 3 mm thick. Differing curvatures of the thicker fragments – 150 and 200 mm diameters – show that either two separate cooking pot/kettle sizes are represented or that one of the objects was oval shaped (figure 6.8). The recovery of two stumpy iron pot feet suggests the cooking pot/kettle was manufactured in the standing tripod or four-leg style, popular in both Asian and European iron cooking vessels (figure 6.9). According to Anderson and Anderson (1977: 359), Lee and Lee (1979: 27), and Passmore & Reid (1982: 35), Chinese people did not tend to roast or bake food in their day-to-day cooking practices. Therefore, an iron pot would have been used for boiling rice, soups, stews and other liquid-based dishes and the wok for stir-frying, deep-frying, simmering and steaming. Kettles, pots and woks represent common kitchen implements in Chinese culture (Evans 1980: 90; Passmore & Reid 1982: 30). 96

Figure 6.8 Curved cast iron cooking pot fragments from Chinaman’s Point suggest that oval-shaped cooking pots such as the one shown here may have been used at the site.

Figure 6.9 Stumpy iron pot feet from the Chinaman’s Point site and a diagram of the type of vessel they most likely represent.

Food

Bone and shell remains are the only evidence of food consumed at Chinaman’s Point. All bone remains are believed to represent aspects of the diet of site occupants. Faunal remains are useful for deciphering cultural preferences, living conditions and the possible socio-economic status of the population (Schulz and Gust 1983: 44). Fifty-six bone pieces weighing 560 g and ten marine shells weighing 87 g were recovered. The bone and shell assemblage is analysed by individual taxa and then discussed as a single data set. This is intended to identify the full range of species and species components represented in the assemblage, determine the minimum number of each individual fauna, examine butchering and culinary aspects and offer some rationale for the assemblage. Faunal quantities and distribution across the site can be seen in tables 6.6 and 6.7.

Faunal specimens have been identified, described and analysed through the aid of documentary, pictorial and physical references such as in Levine (1921), Boessneck (1969), Schmid (1972), Coleman (1975), Getty (1975), von den Driesch (1976), Halstead & Collins (1994), Lyman (1994), Leach (1997), Jansen (2000) and in the bone and shell reference collection at La Trobe University. Six bone pieces weighing 5 g and six shell pieces weighing 20 g were too fragmented for accurate identification to a taxa level. The assemblage contains 20 sheep (Ovis aries) bones, 19 cattle (Bos taurus) bones, seven fish (Pisces) bones, four pig (Sus scrofa) bones and three chicken (Gallus domesticus) bones. All bone is from domestic taxa, except marine varieties. 97

| Animal | Number of bone pieces | Weight (grams) | Site location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | 19 | 329 | area 3, 4, TZ |

| Sheep | 20 | 147 | area 1, 3, 4, TZ |

| Pig | 4 | 61 | TZ |

| Chicken | 3 | 2 | area 4, TZ |

| Fish | 7 | 9 | area 4, TZ |

| Unidentified | 3 | 12 | area 1, TZ |

| Total | 56 | 560 | N/A |

Table 6.6 Number, weight and location of recovered animal bones (TZ = tidal zone).

| Animal | Area 1 | Area 2 | Area 3 | Area 4 | Tidal one |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep | 1 | 3 | 4 | 12 | |

| Cattle | 2 | 3 | 14 | ||

| Fish | 3 | ||||

| Chicken | 1 | 2 | |||

| Shell | 10 | 4 | |||

| Pig | 4 | ||||

| Unidentified | 1 | 2 |

Table 6.7 Faunal distribution across the site (minimum numbers identified).

A brief discussion on the Chinese consumption of meat and the differences between European and Chinese butchering practices provide useful background to the faunal analysis. The diet of overseas Chinese people varied from traditional food practices in southern China. The significance of this variation often remains undetermined in archaeological projects – i.e. it is not clear whether this reflects acculturation or simply a reflection of food availabilities or elements of both (Ritchie 1986: 623–24; Langenwalter 1987: 76; Longenecker & Stapp 1993: 98).

While acknowledging that some dietary variation occurred, it is generally accepted that most overseas Chinese people preferred to maintain their traditional dietary habits which consisted largely of rice, cereals and grains as a staple; a wide variety of vegetables and spicy sauces and in most cases only small quantities of meat (Spier 1958: 130; Anderson & Anderson 1977: 319; Piper 1988: 34). Depending on region, meat eaten in the traditional Chinese diet – in order of importance – has been documented as pork, fish (in areas near large bodies of water fish outranked pork in importance), beef, poultry and mutton (Anderson & Anderson 1977: 336; Langenwalter 1987: 56; Buck 1937: 413). Chinese people eat almost all parts of an animal except feathers, scales, hair and bone, which are generally used in other ways. Carcasses were carefully butchered to assist this maximum-usage pattern (Mote 1977: 201; Wang 1920: 290).

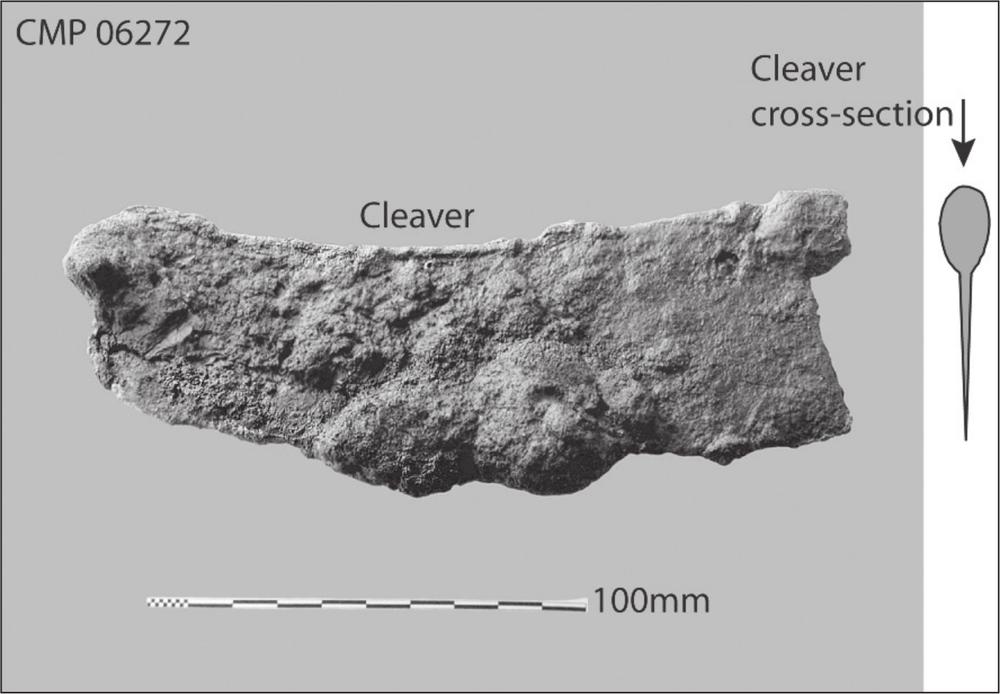

Colonial European butchers commonly used knives, cleavers and handsaws to divide animal carcasses, while Chinese butchers generally used knives and cleavers (Levine 1921: 8; Piper 1984: 35). Levine (1921: 11) and Longenecker & Stapp (1993: 105) suggest that occasionally – and only for cutting the pelvic, breast or vertebrate bone – Chinese people used saws. However, saws are not included in the standard Chinese animal-butchering kit described by Levine (1921) and Longenecker & Stapp (1993) and are usually not discussed in association with Chinese butchering techniques.

Accordingly, when examining butchering patterns in bone assemblages from overseas Chinese sites, the difference between European and Chinese butchering technologies should be identifiable through the presence or absence of saw marks on the bone – except for pelvic, breast or vertebrate bone. Langenwalter’s (1980: 107) studies on butchering techniques show that width and depth analysis of chopping marks on bone are also useful in distinguishing between European and Chinese butchering marks. While chopping marks on bone from Chinaman’s Point are too weathered to enable this type of analysis, saw marks are common. 98

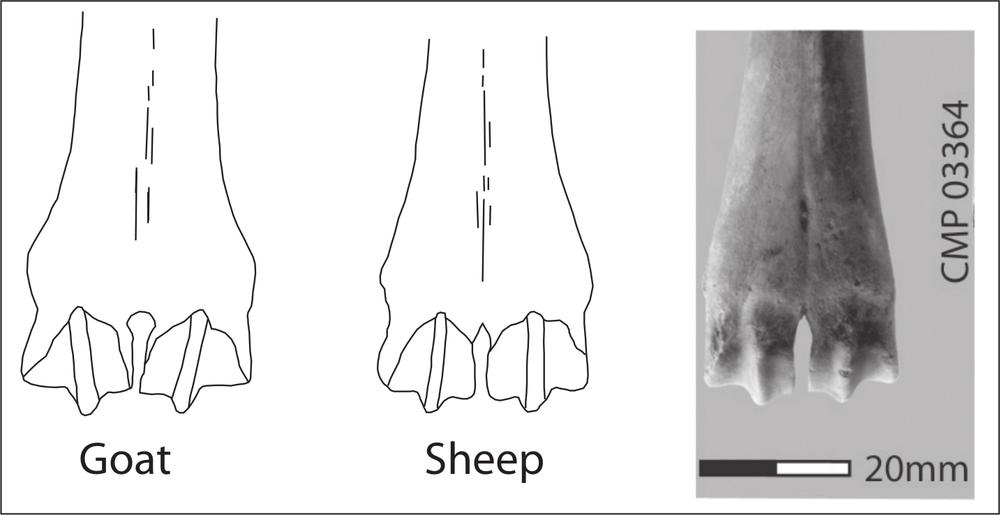

Sheep

In southern China, the Chinese fat-tailed sheep had minor importance as a source of meat, comprising approximately one percent of the standard dietary intake (Levine 1921: 4; Langenwalter 1987: 76). However, the widespread consumption of sheep by overseas Chinese people has been recorded at archaeological sites in the United States, New Zealand and Australia (Piper 1984: 22–23; Ritchie 1986: 621; Longenecker & Stapp 1993: 100; Lydon 1999: 97). Sheep were represented at Chinaman’s Point through metacarpi, humeri, ribs and teeth. It is estimated from the presence of four right metacarpis, bone size and tooth maturity that four incomplete individual sheep are represented. The recovered metacarpi distal ends show small, slightly notched, parallel trochlear condyles which, as described by Boessneck (1969: 355), clearly define them as sheep as opposed to the very similar skeletal structure of goat (Capra hircus) (figure 6.10). Moreover, goat was considered by the Chinese to be a greatly inferior quality of meat and was not commonly eaten (Levine 1921: 2, 4). One metacarpus displays distinct gnaw marks that are most likely from a rat, demonstrating rodent activity at the site.

Figure 6.10 Metacarpus from Chinaman’s Point showing similarities to sheep as opposed to goat.

The humeri have had either their distal, proximal or both ends removed by saw, which is usually associated with bone-marrow extraction (Piper 1991: 273). A number of rib bones were also sawn through at approximately one third from the head end, similar to European methods of butchering sheep (Piper 1991: 310).

The assemblage of sheep teeth includes a number of worn M2 and M3 molars from animals aged between two and four years. One pre-molar tooth was also present (Getty 1975: 93). The recovery of teeth and a cervical vertebra implies cranium presence, which could reflect on-site slaughter of animals (Schulz & Gust 1983: 48; Longenecker & Stapp 1993: 110). However, as most of the recovered sheep bone display European butchering patterns, it seems more likely that sheep heads were brought to the site and used for meals such as sheep’s head soup and those involving tongue, eyes and brain.

One weathered humerus displays a possible cleaver/chopping/cut mark in conjunction with saw marks. This mark could represent bone de-fleshing by a European butcher or a Chinese cook to reduce the size of meat cuts and assist handling with chopsticks (Chinese people did not use knives during meals) (Ball 1925: 149; Chang 1977: 8). Sheep bone from Chinaman’s Point shows a consistency with low meat-bearing portions and European butchering practices (Piper 1991: 93–94). This suggests that cheap cuts of sheep were purchased from European butchers, as opposed to sheep slaughtering and butchering occurring on site.

Cattle

Cattle in Australia have always been used predominantly for meat. During the 19th century in China, cattle were usually only eaten as a luxury item and were considered to be more valuable for pulling ploughs than for consumption (Wang 1920: 292; Langenwalter 1987: 75; Piper 1988: 35). Chinese people with strong Buddhist beliefs avoided eating beef altogether and many others considered it a sacred meal to be consumed only on special occasions (Wang 1920: 289; Mote 1977: 201). Nevertheless, beef did have some role in the Chinese diet and was estimated by Buck (1937: 413) to have contributed between two and seven percent of the animal calories for southern Chinese people.

A total of 19 cattle bones represent a minimum of two incomplete animals. This number was estimated through the presence of two different sized phalanx number two bones. The recovery of cattle phalanxes, 99carpi, tarsi, tibias, patellas, sawn proximal femurs, longitudinally sawn humeri and pelvis bones indicate that the Chinese tended to eat low meat-bearing portions. One mandible was located and is also a low meat-bearing part. None of the cattle bones display cleaver/chopping marks, but, as with the sheep bone, appear to have been sawn in the European fashion (described by Ritchie 1986: 591).

Two rib bones have been sawn into unusually small 60 mm long sections. Piper (1984: 20) discusses a similar bone assemblage from a Chinese site in New Zealand, suggesting they may represent the purchase of specially requested meat cuts. Cutting ribs (and other bone pieces) into small portions is a common Chinese practice especially for the sweet stir-fry meal of chue p’aai kwat and for ease of handling with chopsticks (Levine 1921: 13; Chang 1977: 8). Purchasing ribs pre-cut to this size would minimise the preparation required for Chinese-style cooking.

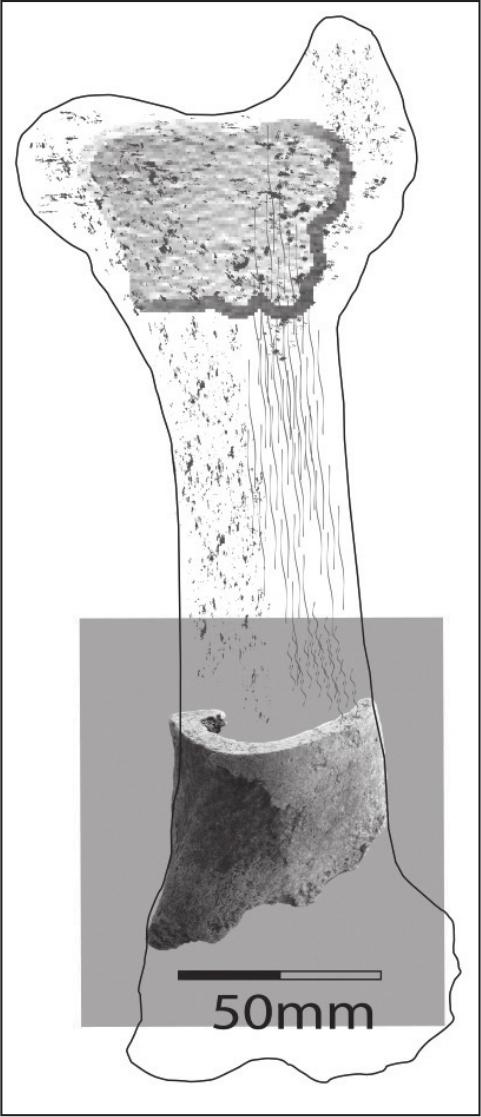

Larger bones such as the tibia and humerus have had their proximal/distal ends sawn off, or have been split longitudinally (figure 6.11). Similar butchering patterns on cattle bone were noted by Ritchie (1986: 591, 623) at Chinese sites in New Zealand and were suggested to indicate the “distinctly Chinese practice” of bone-marrow extraction. Smith (1998: 151) also noted the same cut patterns from Chinese sites at Kiandra, New South Wales. Marrow bones are very cheap to purchase and are generally used for stock in soups, broths and stews (Piper 1988: 37).

Cattle age at time of slaughter – estimated through size comparisons – was between one and three years, which is a standard slaughtering age for quality beef (Longenecker & Stapp 1993: 115).

Figure 6.11 Cattle long bone from the Chinaman’s Point site showing signs of deliberate sawing most likely for the removal of bone marrow.

Pig

There is generally a low representation of pig bone from overseas Chinese sites in Australasia. Pork is the favoured meat in China, accounting for an average 72% of dietary calories (Buck 1937: 413). Its low representation in Australasia is most likely a reflection of the limited availability of pork and its high price compared to beef and mutton during the colonial period (Piper 1988: 36). A lower left-side tusk, two rib bones and a left calcaneus were the only pig elements identified from the bone assemblage at Chinaman’s Point. The tusk size and visible fusing on the calcareous indicate that the pig was between two and two-and-a-half years old at time of slaughter. This is a relatively old hog for meat purposes which suggests a female animal, as male hogs were usually slaughtered under one year old and female hogs were kept longer for breeding purposes (Levine 1921: 14; Silver 1978: 286; Longenecker & Stapp 1993: 115). No butchering marks are evident on the calcaneus or tusk and although both ribs appear to have been sawn to approximately 60 mm lengths, the ends are too weathered for a conclusive result.

100As with the recovered sheep and cattle bone, the pig components represent low meat-bearing parts of the carcass. Studies of pig cranial remains from overseas Chinese archaeological sites such as those considered by Langenwalter (1980: 107) in California and Piper (1984: 21) and Ritchie (1986: 600) in New Zealand conclude that pig skulls were commonly split open and the brain extracted. Levine (1921: 14) states the most common Chinese use of pig head is:

for lard, or cut into strips about three quarters of an inch wide and cured or it may be used for making sausage or head cheese. The snout, ears and tongue may be used fresh or pickled.

This lack of wastage in the consumption of pig is typical of Chinese eating practices (Peabody 1871: 660). It is not surprising then, that archaeological investigations at overseas Chinese sites – including Chinaman’s Point – often recover the lower meat-bearing portions of pig bone (Langenwalter 1987: 75; Piper 1984: 22; Stapp 1990: 194, 200). The older age of the slaughtered pig and the cheaper cuts also suggests that the Chinese were happy and perhaps even thought it desirable (culturally or economically), to consume meat cuts that were considered poor quality by Europeans.

Chicken

Chicken was represented by one small, broken and fragile section of ulna, a radius in similar condition and a complete coracoid from a single mature bird. Both the ulna and radius may have been chopped with a cleaver, however as discussed by Piper (1988: 38), cleaver blows to chicken bones are difficult to determine, especially on weathered samples. Eggs are common in Chinese cuisine and most Chinese people with a little spare land – in China or overseas – raised poultry for eggs (Wang 1920: 290; Yee 1975: 12). Chicken meat, however, was more for special occasions than as an everyday meal and was consumed much less frequently than other poultry such as ducks and geese (Levine 1921: 4; Buck 1937: 413; Nordhoff cited in Spier 1958: 130; Piper 1988: 35). This may account for the negligible representation of chicken bone from Chinaman’s Point.

Fish

In locations near any large body of water, fish is the most important and widely used protein source in China (Anderson & Anderson 1977: 336). It is therefore surprising (especially as it was a fish processing site) that the fish component from Chinaman’s Point contains only seven pieces of bone weighing a total of 9 g. These include the lower mandible and premaxilla from a porcupine fish (Atopomycterus nictheremus), two vertebrae from sand flathead (Platycephalus caeruleopunctatus), one Parika scaber (erectile dorsal spine) from a leather jacket (Nelusetta vittata) and three fish vertebrae that are too fragmentary for identification to species level (Wedlick 1980: 48; Roughley 1957: 139).

Port Albert’s waterways abound with fish which were even more plentiful during Australia’s colonial period. Certainly the occupants of Chinaman’s Point fish-curing establishment would have consumed by choice and for economic reasons large quantities of fish. It is possible that a substantial cache of fish remains was missed during the site excavation process. Such ‘bone pits’ have been discovered at other colonial-period overseas Chinese sites (see for example Longenecker & Stapp 1993: 118). Possibly the cooking methods – steaming or boiling – softened the bones to such a degree that they have not survived in the archaeological record. Fish resources at Chinaman’s Point may have been so abundant that only the fleshiest parts were consumed – as with the European ‘boneless fillet’ – and the wasted portion thrown into the water with the commercial fish offal, used as berley when fishing or possibly taken off site and used as fertiliser, for example at Chin Lang Tip’s Chinese market garden approximately two kilometres away. However, as most bone came from the site’s tidal zone, the most likely explanation for the scarcity of fish remains at Chinaman’s Point is that food scraps were thrown in the rubbish tip area. It is likely that the fish bones were not heavy enough to withstand the tidal currents and were washed away – probably along with other animal bone and light materials from the site.

Shell

Ten shell pieces weighing 87 g were recovered from Chinaman’s Point. This shell represents three bivalves – two from the Mytilidae family (Xenostrobus inconstans) and one mud oyster (Ostraea angasi) – and one gastropod from the Muricidae family (Thais baileyana) (Coleman 1975; Jansen 2000). Of the remaining six shells, all are gastropods that are too fragmented to identify, other than that they are of a conical variety. As only the mud oyster represents a commonly used human food source and as shells occur naturally in the environment, with no definitive connection to human activity (Colley 2005: 75), the site’s shell component is not considered to represent a significant dietary source.

Discussion

The bone assemblage from Chinaman’s Point is typical of other overseas Chinese sites in Australasia. Although the sample size is small, meat consumption appears to have mainly consisted of sheep and cattle and to a lesser 101extent pig, chicken, fish and shelled mollusc. Meat consumption ratios are difficult to determine as fish and other animal bone is suspected to be severely under-represented (due to artefact removal through tidal-based site erosion) and it is unclear what quantities of sheep and cattle bone were purchased for bone marrow rather than for flesh. It is probable that the site occupants had a standard diet of fish, varied occasionally by other meats. The dominance of sheep and cattle bones over pig differs from traditional Chinese dietary preference. However, such a bone assemblage is common at overseas Chinese sites (see for example Piper 1984; Ritchie 1986; Langenwalter 1987; Smith 1998) and can be explained in terms of availability and relative cost of meats, as opposed to a change in dietary preferences.

A preference for lower quality, cheaper meat portions is noticeable in the sheep, cattle and pig bone assemblage. The use of low meat-bearing parts is often viewed as reflecting the site occupants’ low economic status (Schulz 1979: 56; Schulz & Gust 1983: 44). Australia’s colonial Chinese population is frequently portrayed as being frugal (Gittins 1981: 72), providing a convenient explanation for the cheap meat cuts from Chinaman’s Point and other sites. However, Chinese people have a cultural preference for less fatty, lower meat-bearing cuts and marrow bones used in Chinese style cooking. As animal bones from overseas Chinese sites in Australasia and the United States generally indicate a predominance of low meat-bearing parts such as head, rib, leg, shin, knuckle and marrow bones from sheep, cattle and pig (Langenwalter 1880: 107; Ritchie 1986: 593, 600, 602; Langenwalter 1987: 75, 88, 93; Smith 1998: 154, 286), a bone assemblage with a dominance of these types of meat cuts (if associated with other suitable material or documentary evidence) could be considered an indicator of overseas Chinese occupation of a site. The occupants of Chinaman’s Point probably purchased these types of meat cuts very cheaply for use in traditional Chinese dishes.

The absence of chopping marks, the dominance of saw marks and a pattern of standard European carcass dissection (described by Ritchie 1986: 591, 610–11) of the bone recovered from Chinaman’s Point, suggest that sheep and cattle elements were purchased from European butchers. While no definite conclusions can be made in regard to the butchering of the recovered pig elements, their low representation suggests that pigs were not raised and slaughtered on site.

None of the recovered bones display evidence of burning, which is typically demonstrated by white, often fragile sections of bone (Spennemann & Colley 1990: 57). Together with the style of cooking containers recovered from the site (stewing pots and a wok), this provides further evidence of Chinese cooking techniques, including water-based meals such as soups, broths and steamed foods and quick-cooking stir-fry meals (Ball 1925: 149; Anderson & Anderson 1977: 355, 358; Piper 1984: 12).

Food storage

Two types of food container were identified from Chinaman’s Point – European and Chinese timber casks and stoneware containers.

European cask

A 2450 year-old Egyptian-built wooden cask on display in New York’s Museum of Fine Arts reveals the long history of these storage containers (Hughes 1925: 22). During the 19th century, wooden casks were the most common form of bulk container used to store and transport food and other goods (Staniforth 1987: 21).

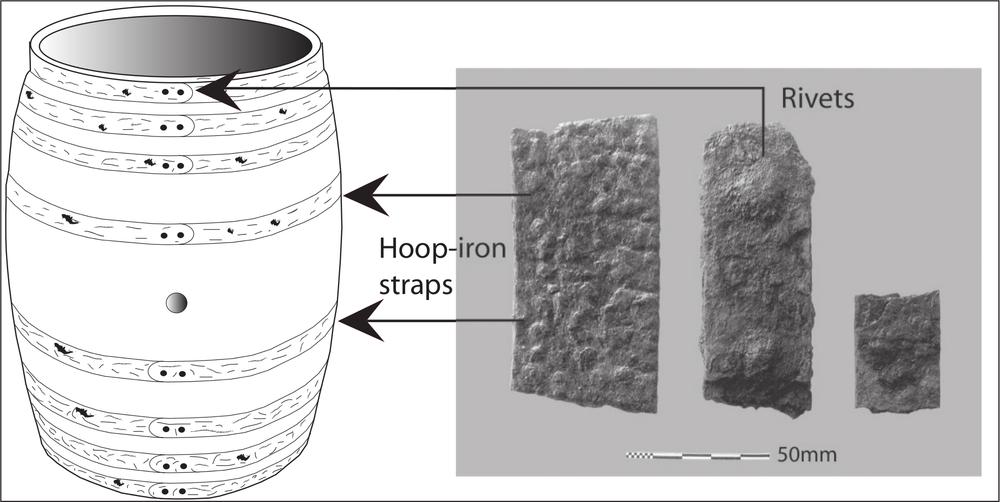

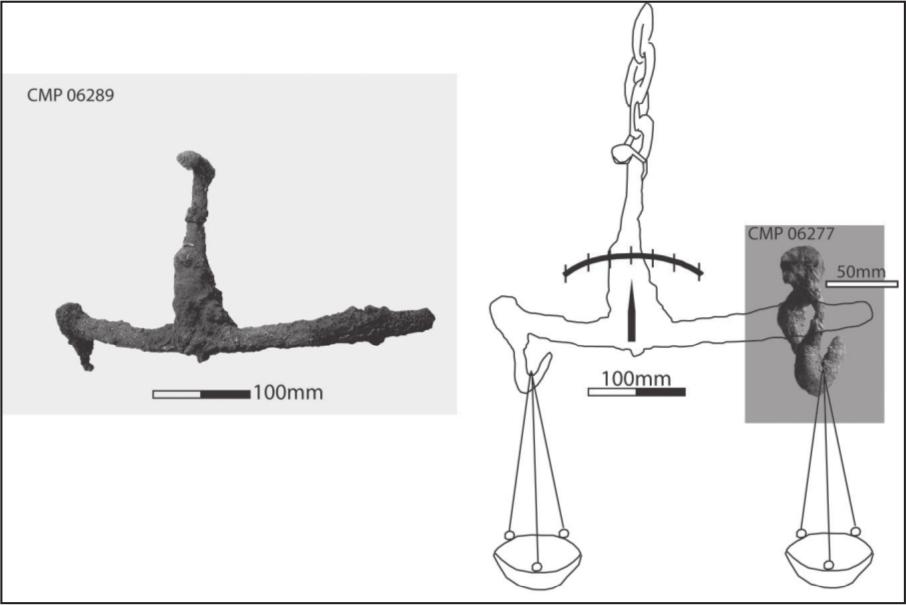

Two thousand and fifty six pieces, weighing 131 kg, of hoop iron for cask hooping were recovered from the Chinaman’s Point site. Three widths of strap – 38 mm, 32 mm and 25 mm – mostly displaying a uniform curvature, were evident in the assemblage. These measurements are consistent with standard 19th-century regulations for the top, middle and base hoop iron widths for wooden cask containers (Hughes 1926: 20) (figure 6.12). In association with the cask hooping were 62 metal rivets weighing 2231 g, which are consistent with the type of rivet used for securing the end pieces of cask hooping. Recovered rivets display a convex cylindrical head 20 to 35 mm diameter, 6 to 10 mm body diameter and a hammered flat section that forms the stop-end or inner rivet head.

The original function of the casks was probably to hold foodstuffs. They were probably used mainly at Chinaman’s Point for brining fish, as metal tubs would have quickly rusted and tainted the flesh. Timber casks could be re-used over long periods and may have been fitted with tight covers to reduce evaporation and dilution of the brine through rain water (Ashbrook 1955: 217). As approximately 76% of cast hooping fragments were recovered from area 1 – believed to have been an industrial area of the site – it is conceivable that barrels were positioned here for fish-brining purposes and in other areas of the site for storage of fresh water and other goods. 102

Figure 6.12 Cask hoop (with rivets) from the Chinaman’s Point site shown in association with a 19th-century European iron-hooped cask.

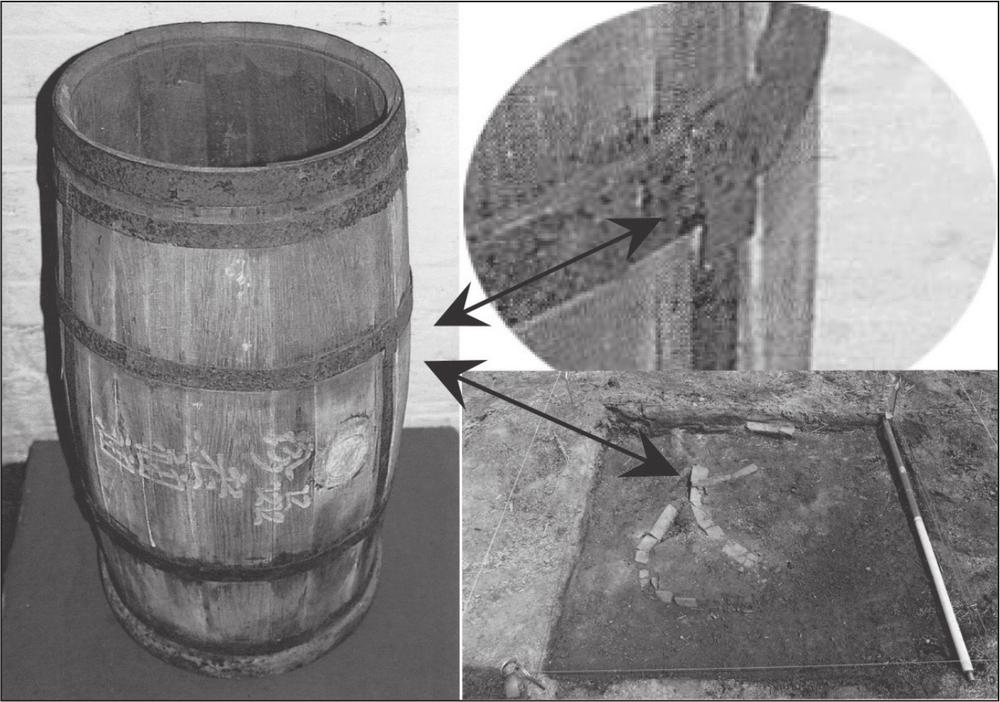

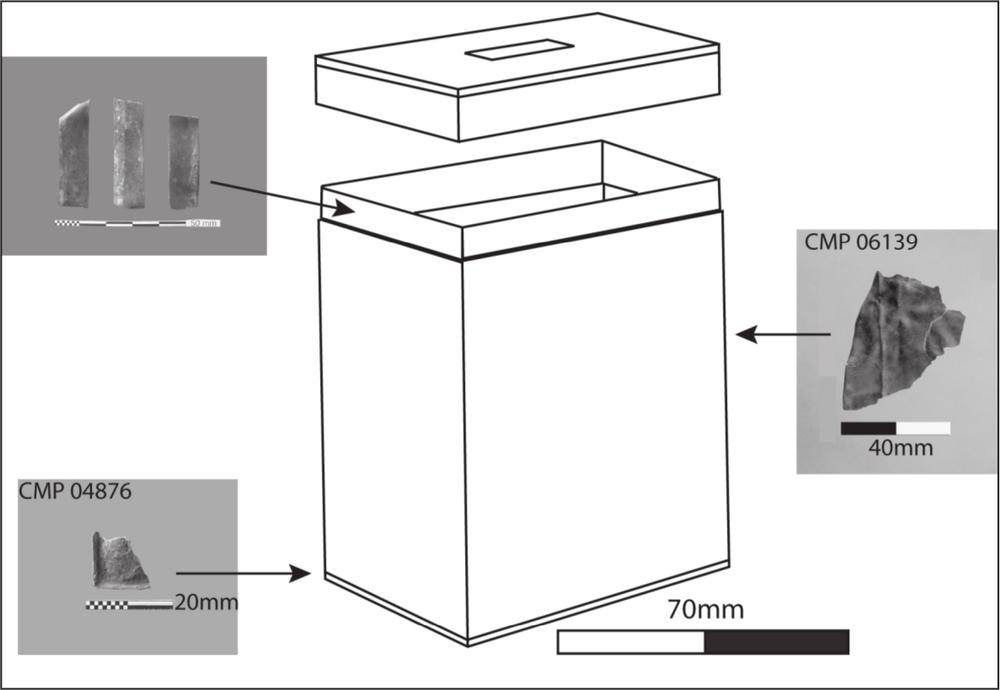

Chinese cask

A Chinese cask is held at the McCrossin’s Mill Museum in Uralla, New South Wales, labelled ‘early 1900s dark soy sauce barrel’ (Wilton 2004: 78). This cask differs in hoop-iron design from European casks as the horizontal, cylindrical hoops (25 mm wide) are supported by vertical, straight sections of iron (20 mm wide). To unite the vertical and horizontal straps, the vertical iron band has been folded and hammered tight around the cylindrical band.

In area 1 at Chinaman’s Point, corroded and fragmented cask hooping was located in association with very fragile timber remains. A section of approximately 20 mm wide hoop iron was bent and hammered flat around another approximately 28 mm wide section of hoop iron to form a 90 degree ‘T’ angle similar to the cask at McCrossin’s Mill Museum. It is probable that this hooping is from a Chinese-style timber cask. The feature was too fragile to be removed without the destruction of material and form. Therefore, it was recorded, drawn, photographed and left in situ (figure 6.13).

Figure 6.13 A Chinese-style timber cask (left and insert) and the in situ cask hooping from Chinaman’s Point. Image of Chinese cask from Wilton 2004: 78.

103The storage and transport of Chinese food items is most commonly associated with Chinese-style brown and green glazed stoneware ceramics. It is likely that Chinese casks held a variety of food items other than dark soy sauce. The Chinese cask remains from Chinaman’s Point may have contained imported items for use by the site occupants or been used to export commodities such as pickled fish from the site. At the very least, its presence reveals that Chinese-style timber casks were used in colonial Victoria and provides a basis to assist future researchers identify such artefacts.

Chinese stoneware

Chinese stoneware vessels specifically designed for food storage include the brown glazed wide-mouthed shouldered jars (and associated lids) and green glazed ginger-style jars. Both vessel types were recovered from the Chinaman’s Point site. The ceramics used by 19th-century overseas Chinese people are the subject of increasing amounts of research. Documentary information on Chinese stoneware vessels and other Chinese ceramics discussed below under the heading ‘Liquid storage’, ‘Tableware’ and ‘Recreational’, has come predominantly from Quellmalz (1972; 1976), Chace (1976), Etter (1980), Ritchie (1986), Brott (1987), Wegars (1988; 1998; 1999), Jones (1992), Wylie & Fike (1993), Sando & Felton (1993), Svenson (1994), Yang & Hellmann (1996), Lydon (1999) and Muir (2003).

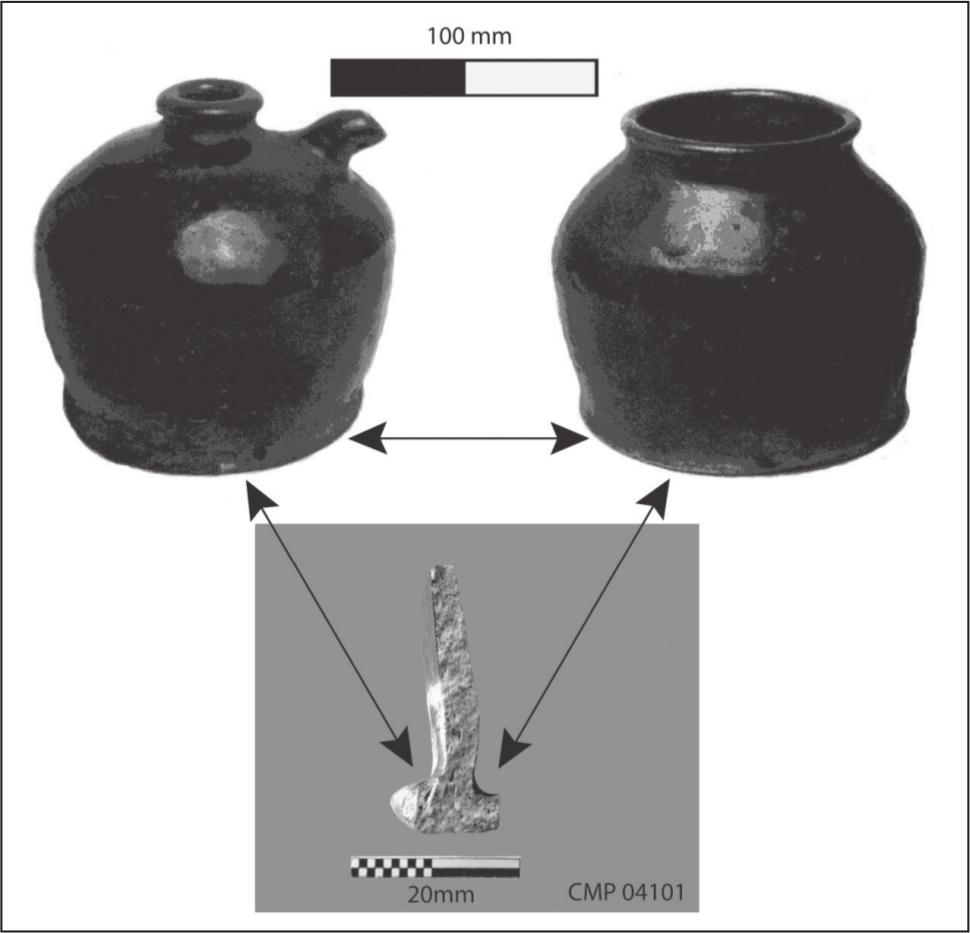

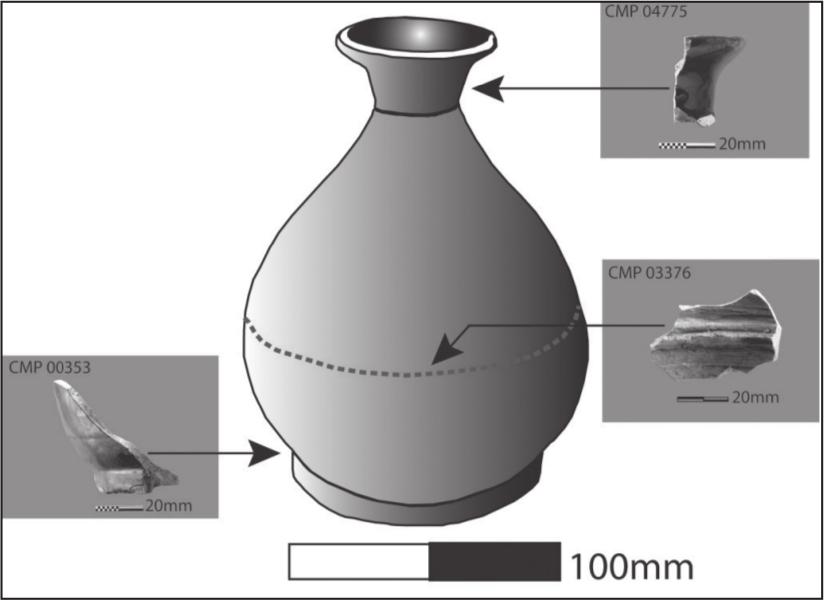

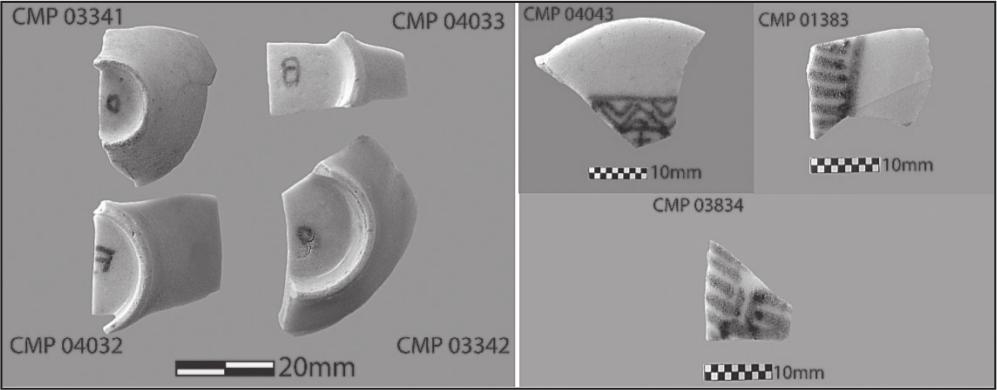

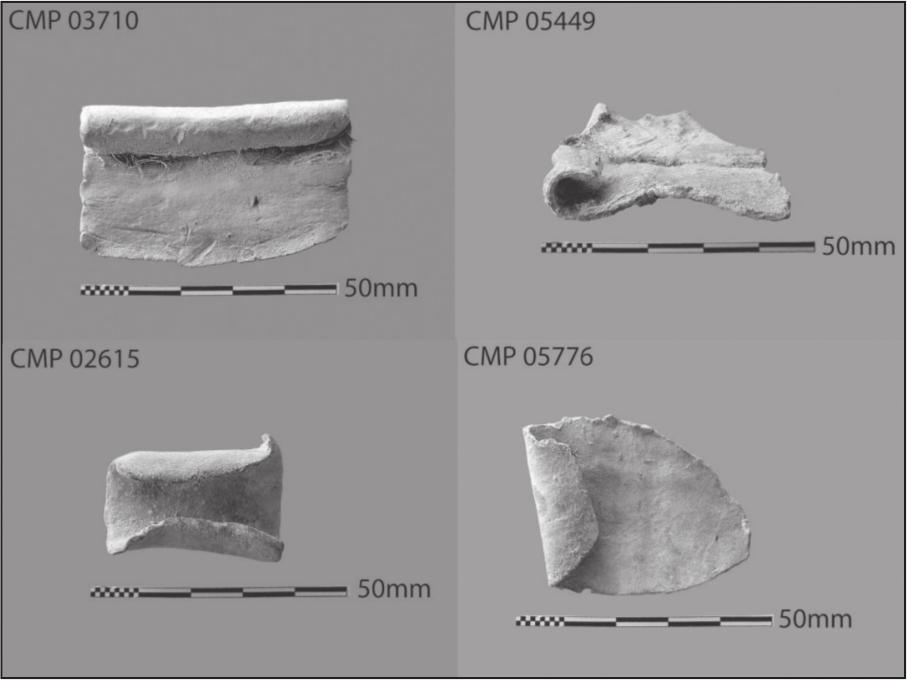

During analysis of the Chinese ceramics from Chinaman’s Point, it became clear that the base and body fragments from wide-mouthed shouldered jars are indistinguishable from those of the Chinese spouted jar (figure 6.14). Ritchie (1986: 234, 238) has also documented this similarity in artefacts from overseas Chinese sites in New Zealand and suggests that the body and base sections “could have been mass produced for both pot types”. In a fragmentary assemblage, it is only when rim, spout or shoulder sections of these vessels are represented that the individual items can be identified. For this reason, brown glazed stoneware fragments that could not be clearly identified as either a wide-mouthed or spouted jar are referred to here as being either wide/ spouted jars. The minimum number count for wide/spouted jars (table 6.8) has been estimated through base diameter reconstructions. Type, number of sherds, MNI and location for Chinese stoneware vessels is shown in table 6.8.

| Chinese stoneware | Number of sherds | Weight (grams) | MNI | Site location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquor bottles | 167 | 805 | 7 | TZ |

| Spouted jar | 63 | 545 | 19 | area 4; TZ |

| Wide-mouthed jar | 36 | 176 | 5 | TZ |

| Wide/spouted jar | 2377 | 10 966 | 26 | area 3; 4; TZ |

| Green glaze jar (round) | 31 | 68 | 2 | TZ |

| Lid/shallow bowl | 60 | 168 | 24 | TZ |

| Total | 2734 | 12 728 | 57 | N/A |

Table 6.8 Type, number of sherds, MNI and location for Chinese stoneware vessels (TZ = tidal zone).

Figure 6.14 The Chinaman’s Point base sherd could represent a Chinese spouted jar (left) or a Chinese wide-mouthed shouldered jar (right). Images of complete jars from Muir 2003: 44–45.

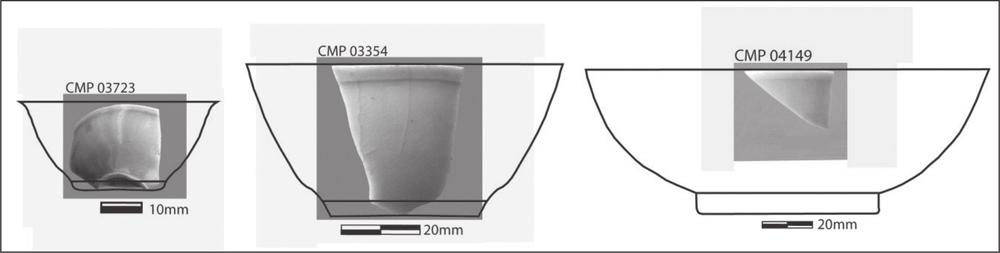

104Wide-mouthed shouldered jar

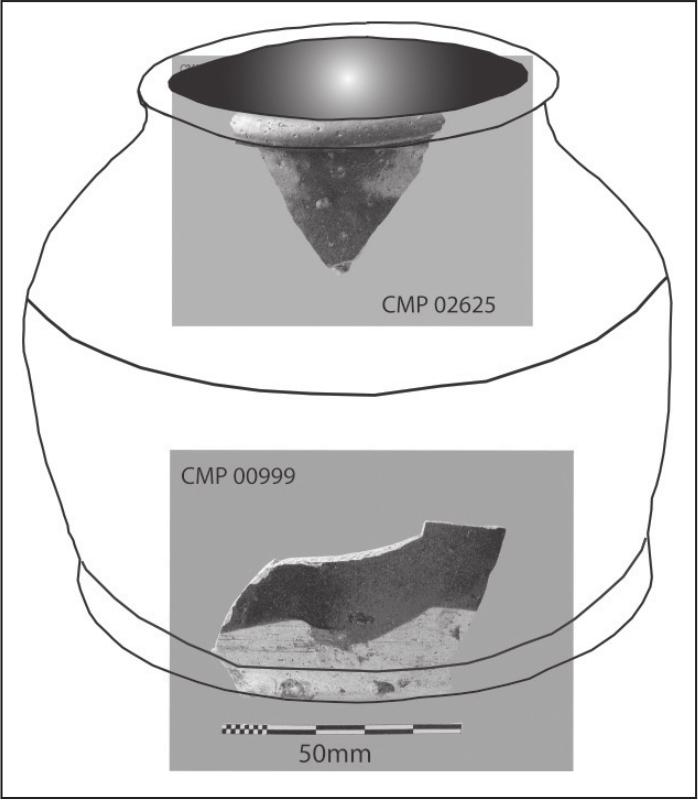

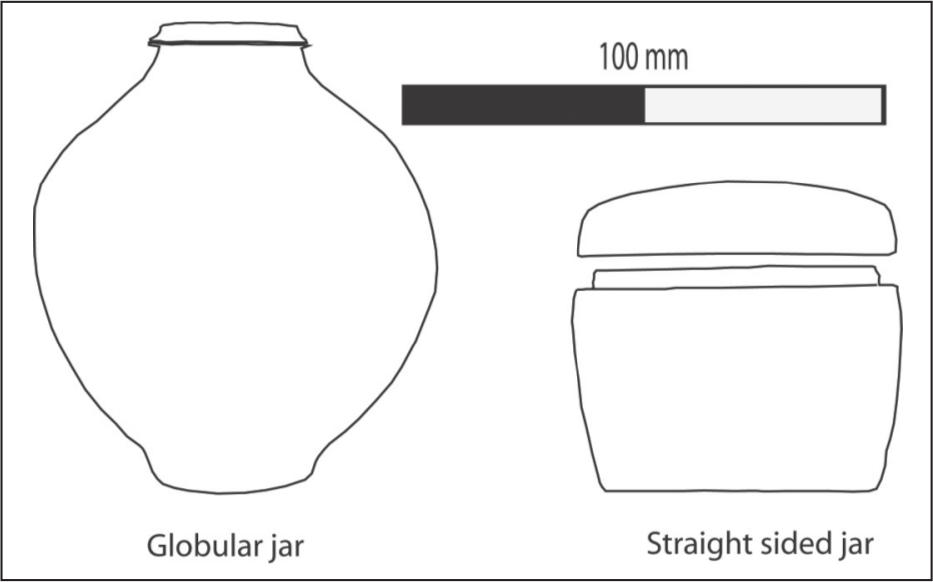

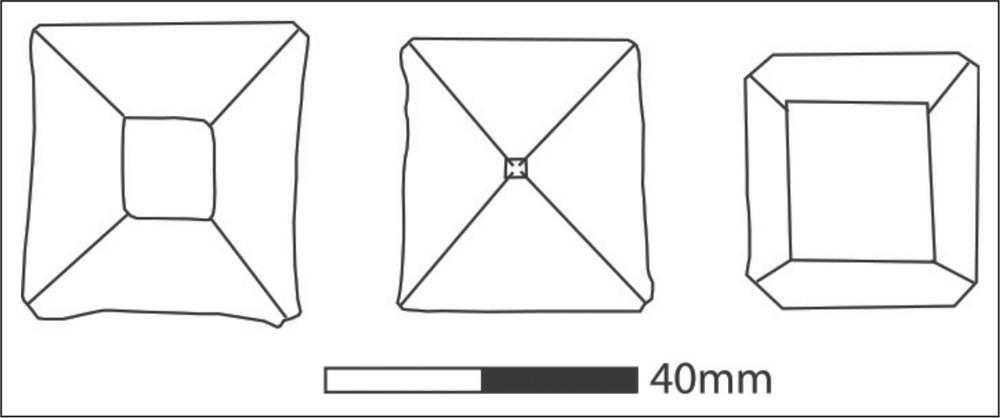

These utilitarian brown ware vessels are generally recovered in association with seven other Chinese brown ware containers: spouted jar, straight-sided jar, globular jar, liquor bottle, barrel jar and pan and are among the most common artefacts discovered at overseas Chinese sites (Yang and Hellmann 1996: 4–9; Lydon 1999: 215). They were produced in China from coarse stoneware that was shaped on a spinning wheel to a consistent ‘idealised form’ (Ritchie 1986: 231) and have a thick outer coating of brown iron glaze and a thinner, often uneven inner brown glaze (Muir 2003: 44). Their bases are concave and left unglazed externally (figure 6.15). The minimum number count for wide-mouthed shouldered jars from Chinaman’s Point (shown in Table 6.8) has been estimated through rim fragment diameter associations. Interestingly, the usually very common straight sided and globular jars (figure 6.16) were not found in the Chinaman’s Point assemblage.

Wide-mouthed jars are commonly between 130 to 150 mm high (Muir 2003: 44), with samples recovered from Chinaman’s Point displaying an average 4 mm in body thickness, between 100 and 200 mm in base diameter and 80 to 150 mm in rim diameter. Papers such as Yang & Hellmann (1996) have examined the uses of imported Chinese brown ware vessels in the United States and what their contents may have been, however archaeologists still struggle to ascertain a specific range of contents. It is generally accepted that they were used to store a wide array of preserved and raw foods such as eggs, vegetables, bean curd, fruit, garlic, soy bean, food pastes, salt and sugar. They also had an extremely versatile re-use value (Olsen 1978: 32; Yang & Hellmann 1996: 3; Muir 2003: 44).

Figure 6.15 Drawing of a wide-mouthed shouldered jar with associated artefacts from the Chinaman’s Point site.

Figure 6.16 Surprisingly, the Chinese globular jar (left) and straight-sided jar (right), were surprisingly not represented at the Chinaman’s Point site.

Wide-mouthed jars recovered from other overseas Chinese sites often display burning on the base sections, indicating that they have been used for cooking purposes (Ritchie 1986: 242). No stoneware bases from Chinaman’s Point revealed evidence of burning, however two base sherds from wide/spouted Chinese brown glaze vessels had residue adhered to their inner surface. This residue likely represents food remains and although expensive analyses could not be conducted for this project, future chemical analysis of these residues holds potential to reveal further information about the everyday lives of overseas Chinese people in colonial Australia. 105

Lid/shallow bowl

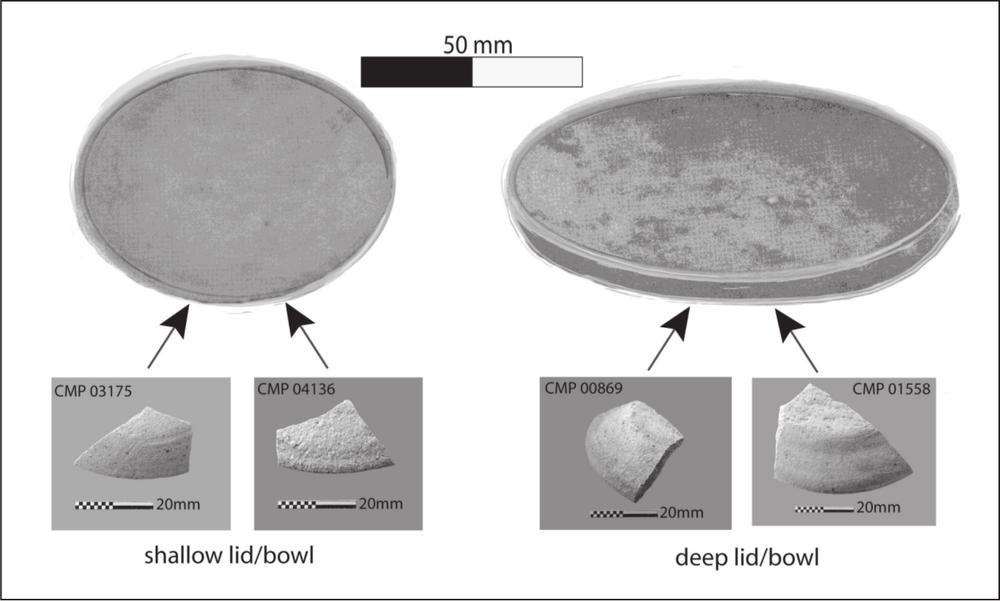

Chinese wide-mouthed jars are often located in association with unglazed, concave, stoneware lids. Ritchie (1986: 242) suggests the lids were fitted to seal the wide-mouthed vessels with soft unfired clay, the remnants of which are still adhere to some lids recovered from New Zealand sites. Yang and Hellmann’s (1996: 3–4) discussion on functional re-use suggests the saucer shape of the lids enabled them to be re-used as shallow bowls for sauces and other food.

The minimum number count for lid/shallow bowls from Chinaman’s Point (table 6.8) has been estimated through rim fragment diameter associations. The lids range between 80 and 150 mm in diameter, have an average 3 mm body thickness, sit between 10 and 15 mm deep in the bowl and range in colour from cream to buff red (figure 6.17). The lid diameters correspond with the wide-mouthed jar rims, thereby complementing Ritchie’s (1986) and Yang & Hellmann’s (1996) theory that the two items are associated artefacts.

Figure 6.17 Fragments of unglazed lid/shallow bowls from the Chinaman’s Point site and pictures of the complete items.

Chinese green-glazed jar

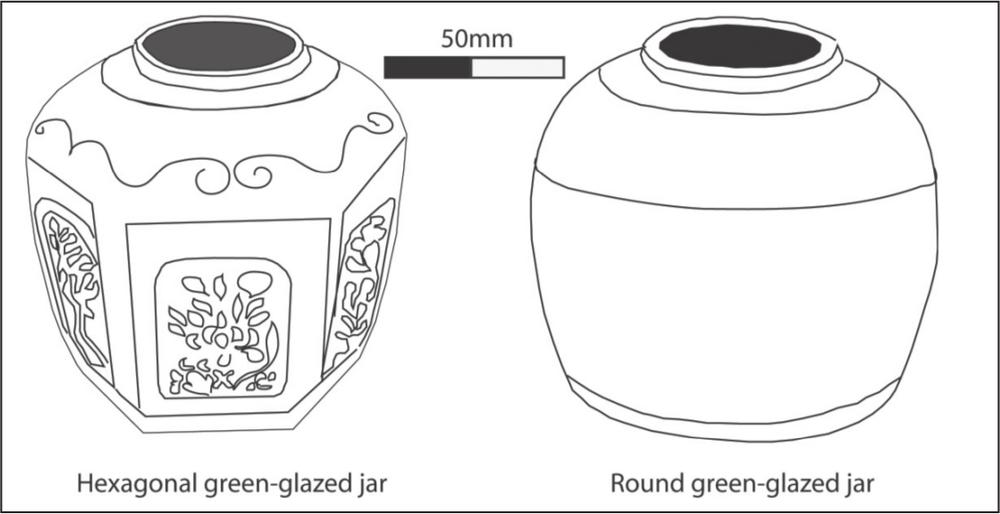

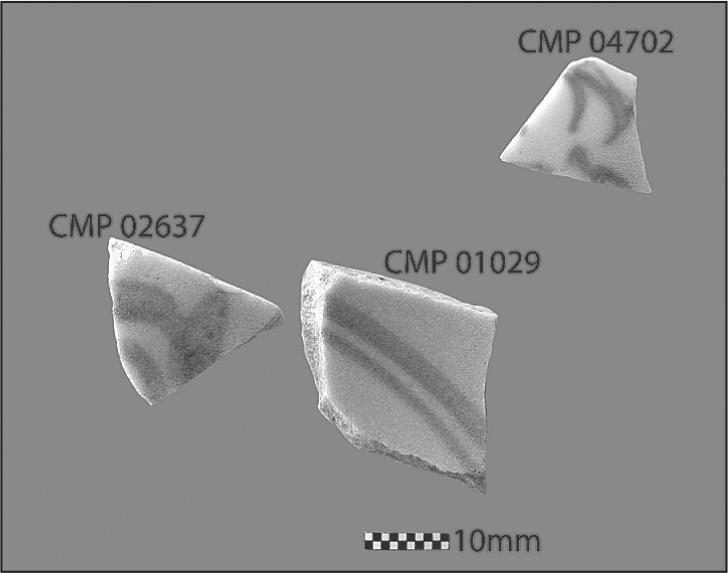

Green-glazed Chinese stoneware vessels are generally associated with the term ‘ginger jar’. However, as discussed by Olsen (1978: 35), these vessels contained a range of preserved foods other than ginger such as sliced turnip, green onions, green plums and sweet gherkins. Consequently, Ritchie (1986: 259) uses ‘ginger jar’ as a generic term, further suggesting they may also have contained various types of cosmetic or medicinal creams. Two green-glazed jar shapes are commonly recovered from overseas Chinese sites: the hexagonal and the round (figure 6.18). They are produced from a stoneware material, in a similar fashion to the brown glazed vessels, only their glaze is a glossy light or dark green colour (Muir 2003: 46). Wood (1999: 224) has analysed these green glazes to reveal that they were produced from a mix of ground glass and natural minerals found in river mud.

Figure 6.18 The two most common types of Chinese ginger jar: the hexagonal (left) and the round (right).

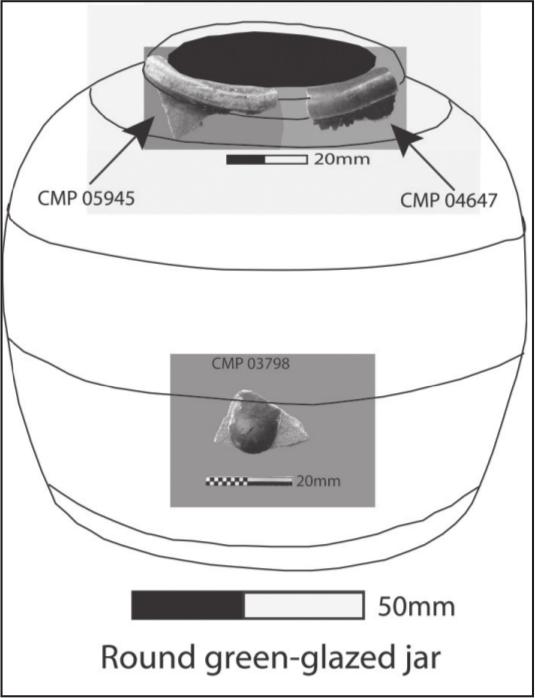

106The minimum number of green-glazed vessels was ascertained through the recovery of three different sized vessel rim diameters – 70 mm, 90 mm and 120 mm (table 6.8). Rim, body and base fragments reveal that each vessel is of the round wide-mouthed variety. In keeping with the green-glazed jars recovered from other overseas Chinese sites such as in Ritchie (1986: 260) and Brott (1987: 245), the green-glazed jars from Chinaman’s Point display a thick outer green-glaze that has been allowed to drip down the exterior to leave thick dollops or drips of glaze. They also have a light brown interior glaze (figure 6.19).

Figure 6.19 Chinese ginger jar rim fragments and a dollop of glaze (centre of jar) from the Chinaman’s Point site.

European stoneware

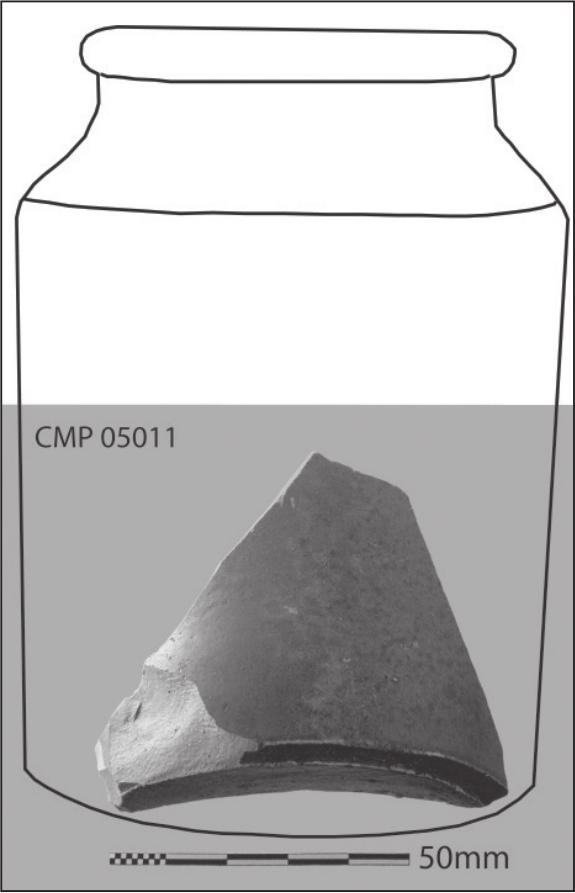

Like Chinese stoneware, European stoneware is generally associated with mass produced, heavy, thick-walled vessels that are most commonly used as utilitarian wares and storage containers with a huge range of re-use values (Sharpe 1992: 48). When kiln-fired, stoneware is non-porous and therefore does not require a glaze to seal the vessel. Even so, an external salt glaze and internal slip glaze was commonly applied for aesthetics or to enable easy cleaning for re-use purposes. Stoneware vessels were produced in a huge range of colours although the utilitarian and storage wares were most commonly a white/cream or light tan to dark brown colour (Gleeson 1997: 64). They were often impressed with a potter’s mark or had transfers printed with black ink, or were manufactured without markings (Arnold 1989: 111–12).

Eleven dark brown, salt glazed, European-style stoneware sherds, weighing 145 g and representing a minimum number of two food storage vessels were recovered from Chinaman’s Point. The minimum vessel count was estimated through the recovery of two similar but separate styles of vessel rim. None of the sherds display any evidence of a manufacturer or trademark. The only recovered base fragment is 80 mm in diameter. The two rim fragments have 60 mm diameters and body sherd thicknesses range from between 3 and 6 mm. These attributes are consistent with the European bung jar, a common storage vessel during the Australian colonial period (Ford 1995: 208). These containers require a large cork stopper to seal their opening, hence the name ‘bung jar’ and stored anything from pickled foods and preserved jams through to shaving creams and medicinal ointments (figure 6.20). They were also regularly sold without contents, as general storage jars (Arnold 1989: 112).107

Figure 6.20 Base fragment of common European bung jar from the Chinaman’s Point site.

Furnishings

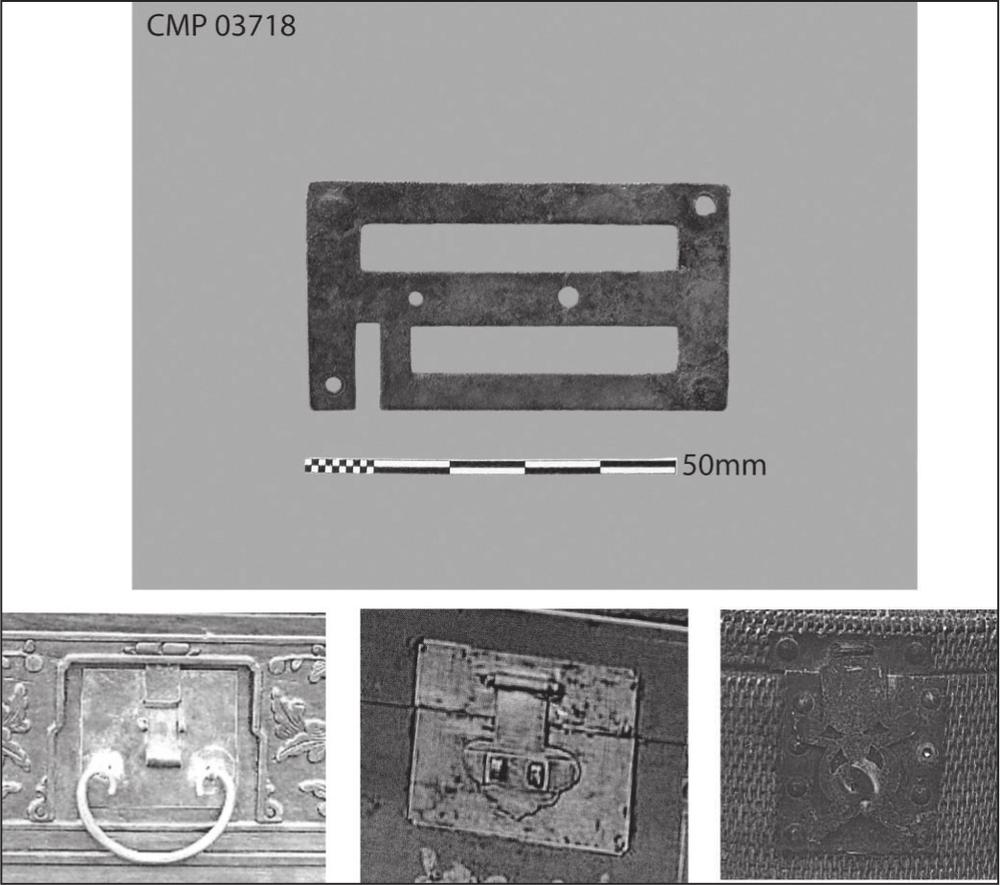

Box hasp

A flat, rectangular piece of brass weighing 13 g and displaying strategic circular and rectangular holes was recovered from the tidal zone at Chinaman’s Point. It measures 61 mm long, 33 mm wide and although set in one complete piece, has three separate rectangle-shaped sections that form two large enclosed rectangles, one small open-ended rectangle and six cylindrical holes. The item has 2 mm diameter holes in each corner of the rectangle, as if to fasten the object to a flat surface and a 2 mm and 1.5 mm diameter hole in its central region. The artefact’s unusual and deliberately constructed proportions suggest it had a specific function, perhaps as a box hasp – a locking mechanism that fits over a fastener and is secured by a pin, bolt, or padlock – on a Chinese luggage or storage chest/box.

Ornate hasps are especially popular in China. Internet sites of dealers in Chinese antiques demonstrate good comparisons, but not an exact match, between the Chinaman’s Point artefact and hasps on antique Chinese storage boxes (figure 6.21). For further examples see (www.trocadero.com and www.chinese-furniture.com).

Figure 6.21 Suspected box hasp from the Chinaman’s Point site (top) and examples of antique Chinese storage-box hasps (bottom). Picutres of box hasps from web pages www.trocadero.com and www.chinese-furniture.com.108

Liquid storage

The following section provides an outline of the main liquid storage containers recovered from the Chinaman’s Point site. These items include two types of material: bottle glass and Chinese stoneware.

Bottle glass

The popularity of glass containers in colonial Australia and the general durability of glass fragments ensure their regular recovery from historical archaeological sites. Analyses of glass assemblages are useful in identifying site occupation dates (discussed in chapter 7), patterns of consumption, living conditions and providing general insights into site activities. Repeated discoveries of similar bottle types across separate sites can also infer an ethnic site occupation, see for example Wegars’ (1993: 223) work on the identification of perfume vials and Ritchie’s (1986: 181, 195, 204) discussion on preferred domestic products, pharmaceutical containers and certain types of alcohol bottles. The data below describes the main glass container forms, specific attributes, their most likely original contents (no adhesive labels were recovered), shard quantities and the minimum number of vessels represented and provides some interpretation of the recovered assemblage as a whole.

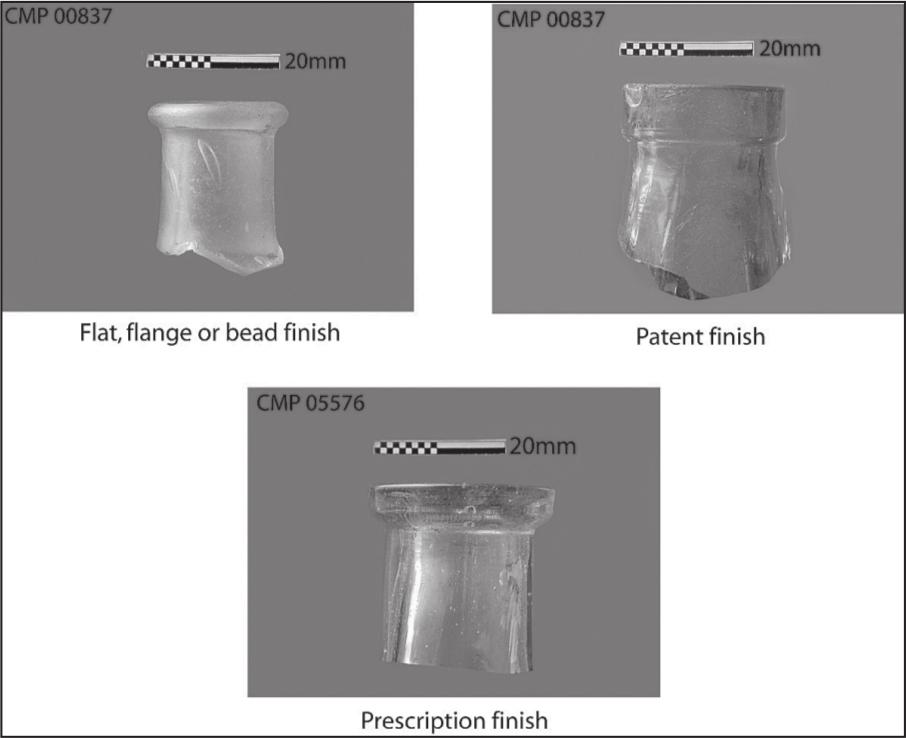

The high level of bottle-collector activity and site erosion through tidal movements is reflected in the recovery of only four complete glass bottles. Therefore, excluding buttons and window glass, the glass recovered – 13 997 shards, weighing 18.361 kg – represents a very fragmentary assemblage. The glass fragmentation and post-depositional movement of tidal-zone artefacts caused difficulty in analysing the glass bottle assemblage. Nineteenth-century glass bottles have a known colour-to-content association that enables broad patterns to be established. For the above reasons, this bottle glass analysis is structured around glass colour: dark green (often called ‘black glass’) light green, aqua-green, amber, light blue, aqua-blue and clear. Terms used to describe the basic bottle components from the top down are: finish, neck, shoulder, body and base (after Jones 1986: 34). Through analysing colour, shard form, bottle finishes and fragments of embossed glass, the main bottle styles appear to be beer, wine, aerated water, alcoholic spirits (gin, schnapps and whiskey), condiments (sauces, essences and oil) and medicinal containers.

One hundred and thirty-eight different bottle forms, representing a minimum number of 845 individual vessels have been identified from the Chinaman’s Point assemblage (tables 6.9 and 6.10). All minimum number of individual vessel counts have been estimated through an analysis of bottle base fragments. Spatially, bottle glass was recovered from all areas of the site, but most prolifically from area 4 and the tidal zone (table 6.11).

| Glass colour | Number of shards | Weight (grams) | Base types | MNI | Total% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dark green | 2993 | 52 641 | 30 | 278 | 32.9 |

| Light green | 6646 | 86 384 | 17 | 247 | 29.2 |

| Aqua-green | 2591 | 25 978 | 36 | 196 | 23.2 |

| Amber | 1236 | 14 617 | 29 | 90 | 10.6 |

| Light blue | 78 | 568 | 3 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Aqua-blue | 168 | 1559 | 17 | 22 | 2.6 |

| Clear | 285 | 1859 | 6 | 8 | 1 |

| Total | 13 997 | 18 3606 | 138 | 845 | 100 |

Table 6.9 Colour, number of shards, number of base types, MNI and MNI percentages for glass containers.109

| Glass colour | Cyl MNI | Sq MNI | Poly MNI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dark green | 231 | 47 | 0 |

| Light green | 206 | 41 | 0 |

| Aqua-green | 171 | 12 | 13 |

| Amber | 76 | 14 | 0 |

| Light blue | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Aqua-blue | 9 | 8 | 5 |

| Clear | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 701 | 126 | 18 |

| Total% | 83% | 15% | 2% |

Table 6.10 Colour, form, MNI and MNI percentages for cylindrical, square and polygonal glass containers (Cyl = cylindrical; Sq = square; Poly = polygonal).

Table 6.11 Chinaman’s Point bottle glass distribution.

As there is no available classification of glass colour in historical archaeology, the colour notation system from the Munsell (1966) book of colour standards has been used to provide an indication of the glass colours discussed. A great deal of literature exists on the identification and analysis of glass items. Glass artefacts from Chinaman’s Point are interpreted primarily through the aid of Jones (1971; 1981; 1986), Toulouse (1971); Vader & Murray (1975), Hutchinson (1987), Wilson (1981), Miller & Sullivan (1984), Jones & Sullivan (1989), Ritchie (1986), Arnold (1987; 1990), Fike (1987), Stapp (1990) and Boow (1991).

Dark green

Dark green glass is often so dark in colour that it appears black, especially in the thicker bottle sections; hence it is often referred to as ‘black glass’ (Boow 1991: 20). Dark green glass from Chinaman’s Point was at its lightest, Munsell hue 7.5GY 3/6, with a middle hue 7.5GY 3/2 and 5GY 2/1 at its darkest shade. Cheaply produced from impure materials – usually with high quantities of natural iron oxides in the sand – dark green glass bottles were manufactured in a range of shapes, sometimes with a globule-type ownership seal on the bottle body and occasionally with embossing (Wills 1974: 16; Dumbrell 1983: 152). These bottles are generally associated with aerated water and alcohols – primarily beer, wine and spirits (Vader & Murray 1975: 37; Boow 1991: 24, 37). Aerated water is unlikely to have been heavily consumed at an all-adult, male dominated Chinese fish-curing site. Imported colonial beer was bulky, which made it expensive to transport compared to its relative sale value, had low alcohol content and went stale during the slow sea voyage to Australia (Dingle 1980: 235). Moreover, for most of the 19th century, Victoria’s brewing industry only produced small quantities of poor quality beer, which in turn created a colonial preference for spirits, predominantly rum and brandy (Dingle 1980: 230, 232, 241). Therefore, the dark green bottles from Chinaman’s Point most likely contained wine and spirits.

Dark green bottles are the dominant type in the Chinaman’s Point glass assemblage by minimum number count. Thirty-five shards reveal evidence of embossing, which in a small number of cases indicated the original bottle contents to have been whisky or schnapps.

One cylindrical dark green bottle base showed evidence of deliberate post manufacture modifications. This base had the push up centre section (the pontil) chipped away to create a small opening in the base centre. Such modifications have been noted – but not analysed – from two other sites in Australia, both with 110an association to overseas Chinese occupation. This base is discussed in detail in the ‘Recreational’ section of this chapter, where a plausible function is suggested.

Light green

Sometimes called ‘forest glass’ or ‘natural green’, light green glass can be produced from only slightly more than the basic glass ingredients of sand and an alkali flux such as lime or soda with the addition of ash from burnt rotten vegetation which reduces the colour impact from iron impurities (Birmingham & Bairstow 1987: 153). Therefore, without the cost of expensive oxides and other compound additives and with more aesthetic elegance than dark green glass, light green glass became favoured among 19th-century glass bottle makers (Proh 1973: 23). Light green bottles had an extremely versatile use in colonial Australia and although they are associated more with wine and aerated water than with beer or spirits, their contents varied widely (Fike 1987: 13).

At its lightest Munsell hue, light green glass from Chinaman’s Point is 7.5GY 7/6, with a middle hue 7.5GY 5/4 and 7.5GY 4/6 at its darkest shade. By shard numbers (6646) and weight (86 384 g), light green is the most common glass colour from Chinaman’s Point, dominated by the middle hue. Seventeen bottle base designs and seven finish types are present. Seventy-two separate shards have evidence of embossing with 64% of these – representing a minimum number of seven vessels – confirmed to be the square bodied Udolpho Wolfe’s Schnapps bottle.

Udolpho Wolf’s Schiedham Aromatic Schnapps is a Dutch-produced, gin-based alcohol created from juniper berries and was widely considered to have been a distilled drink of excellent quality and alcoholic value for money (Valder & Murray 1975: 37; Wilson 1981: 75). Heavily advertised through colonial newspapers and pamphlets including in the local Gippsland papers (Gippsland Standard 1884, March 21) this bottle is a very common find at historical sites in Australia (Vader & Murray 1975: 40). Gin bottles and to a slightly lesser extent brandy, are also common at overseas Chinese sites (see for example Langenwalter 1980: 106; Ritchie & Bedford 1983: 239; McCarthy 1986: 37; Gaughwin 1995: 235). Whether overseas Chinese people found European gins to be of better quality, cheaper or more easily obtainable than the Chinese distilled equivalents (mm ga pei and mui guai lo) is uncertain. It is clear however, that overseas Chinese people in Australasia were consuming greater quantities of European alcohol than Chinese alcohol.

Even with bottles that specifically state their contents, there is no way of ascertaining what the bottles at Chinaman’s Point had contained, as it is likely that many were purchased as refilled second-hand vessels. Boow (1991: 24) indicates, “there are numerous references to used-bottle sales and part payment for returned empties” and both Ritchie & Bedford (1983: 237) and Staski (1993: 135–36) have recovered European manufactured bottles from overseas Chinese sites that have been pasted with Chinese language paper labels. In some cases, these labels had been pasted over embossing that denotes the original bottle contents. This suggests that the re-use of bottles by overseas Chinese people was a common and organised practice.

The Chinese preference for European gins and brandy over other alcohols is noted in colonial-period texts. Adams (1997: 24–26) compiled a number of original food supply invoices from 19th-century overseas Chinese gold miners in Victoria’s Omeo region (figure 6.22). These invoices show gin and brandy as the most frequently purchased alcohols. The Reverend Young’s 1868 report into the state of Victoria’s Chinese population estimates that overseas Chinese people were spending annually almost as much money on spirits as they were on food. Moreover, Reverend Young states that “Mr Wade, of the Coopers’ Arms Hotel, Little Bourke Street, informed me that he sells monthly to the Chinese 40 gallons of gin … in bottles”, an amount equalling the monthly Chinese purchase of all other alcoholic sprits combined (Young 1868 cited in McLaren 1985: 63). 111

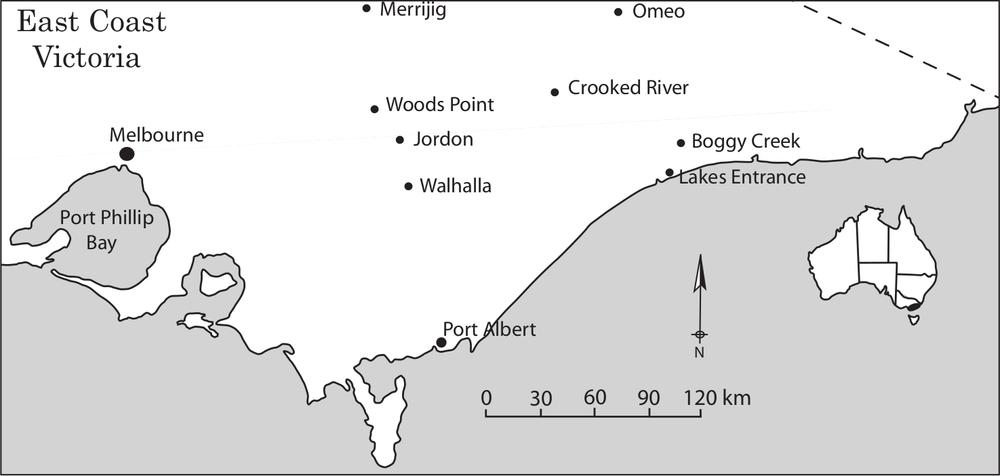

Figure 6.22 Map of Gippsland’s main colonial goldfields including Omeo, top right of map (Melbourne, Port Albert and Lakes Entrance are included as reference points only).

The light and dark green bottle assemblage from Chinaman’s Point suggests there was a preferred consumption of gin over other sprits. However, the fragmentary nature of the assemblage, the versatile use of green bottle glass and bottle re-use makes this difficult to confirm. It would be fair to say, however, that the occupants of Chinaman’s Point consumed considerably more European than Chinese wine and spirits (table 6.12).

| European alcohol bottles MNI | Chinese alcohol bottles MNI |

|---|---|

| 811 | 7 |

Table 6.12 Minimum number of European compared to Chinese alcohol bottles (MNI for European alcohol bottles is an estimate only due to the uncertainty of bottle contents).

Aqua-green

Aqua-green glass is a refined version of light green glass. It is produced through mixing good quality sand i.e. low in iron content, with a standard flux and a small quantity of oxide (Arnold 1990: 5). It had an extremely wide range of uses, including as window glass, drinking glasses, decanters, plates and bottles. In bottle form its contents were also wide ranging, holding anything from soft drinks, cooking additives and condiments, to medicinal liquids and alcohols.

A breakdown of aqua-green glass fragment attributes can be seen in table 6.13. The lightest aqua-green coloured shards correspond to Munsell hue 5GY 9/4 and have only the slightest tinge of green. The middle colour range correlates with the Munsell hue 5GY 8/2 and the darkest verge on a light green, but with a more transparent quality correlating with Munsell hue 5GY 8/4.

| Shards | Weight (grams) | Base types | Finish types | MNI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2591 | 25 978 | 36 | 16 | 196 |

Table 6.13 Green aqua bottle glass attributes.

Ninety-eight shards of aqua-green glass show signs of embossing or other identifying marks which reveal a range of original bottle contents including Champion’s vinegar, other vinegar or oils, coffee essence, Worcestershire sauce and tomato sauce. A number of manufacturer and trade marks were also recovered such as ‘T.B. & Co’, ‘R.M. Goodfellow & Co’, ‘J. Lesson’s’, ‘John Kilner & Sons’, ‘Blogg Brothers’ and ‘Lea & Perrin’. Many shards were too fragmented to accurately identify the embossed symbol, number pattern or wording.

Lea & Perrin Worcestershire sauce bottles have also been noted from other Australasian overseas Chinese sites by, for example, Ritchie & Bedford (1983: 250) and McCarthy (1986: 35). Worcestershire sauce has similarities to Chinese soy sauce – both are an all-purpose spice, have a strong fragrance and flavour, are very salty and use fermented wheat as a base ingredient. Traditional Chinese cooking ingredients were presumably periodically unavailable to the Chinaman’s Point site occupants, therefore European condiments such as Worcestershire sauce may have been used as a ‘best fit’ substitute.

112Similarly, vinegar is a key component of most Chinese food dressings, table sauces, sweet and sour dishes, sautés and stews (Passmore & Reid 1982: 34), which explains the strong representation of Champion’s and other vinegar bottles from Chinaman’s Point. Likewise, most Chinese cooking requires a quantity of vegetable oil (Passmore & Reid 1982: 34), reflected at Chinaman’s Point and other overseas Chinese sites such as those studied by Ritchie & Bedford’s (1983: 250) and Blanford (1987: 195) in the recovery of European-style salad oil bottles, most commonly the waisted band and the twist-neck types. Other domestic food and medicinal bottles in the Chinaman’s Point aqua-green glass assemblage – sauces, pickles, jams, coffee essence, pharmaceutical cure-alls and other pain killers – have been identified predominantly through bottle form or characteristics as opposed to embossing. The use of these items is considered to represent either a substitute for the Chinese traditional equivalent or purely individual choices based on personal preference.

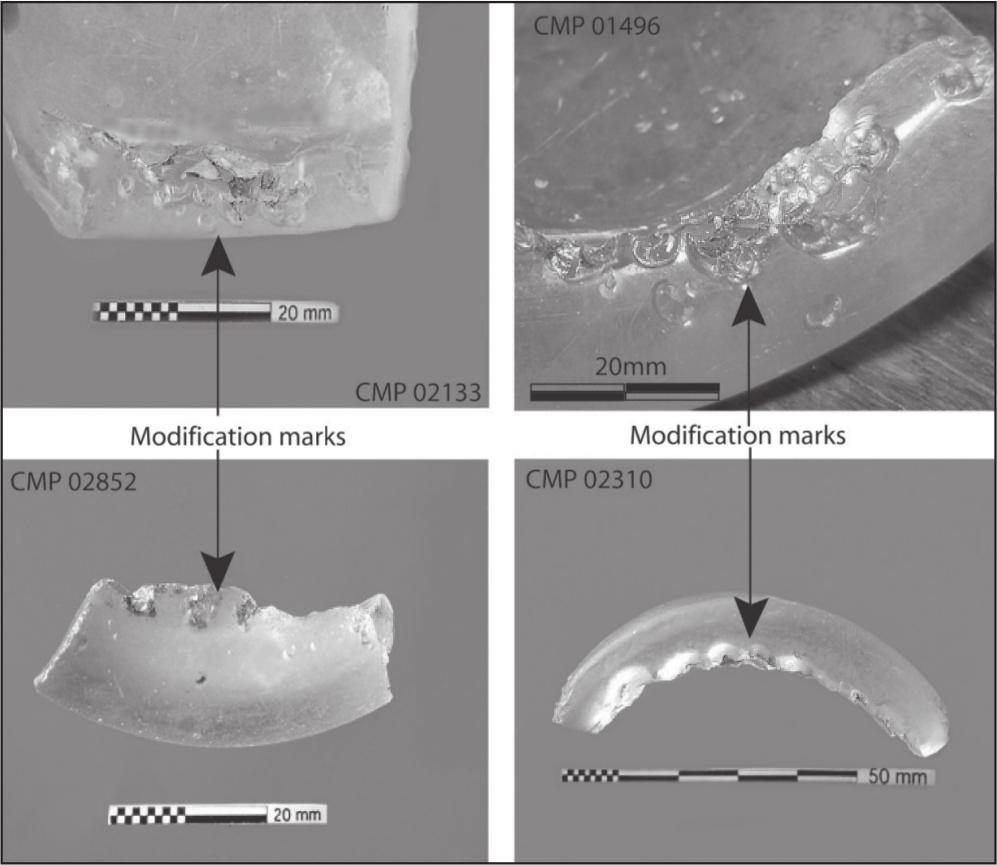

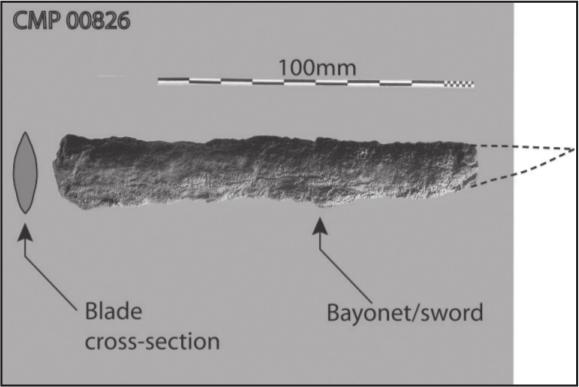

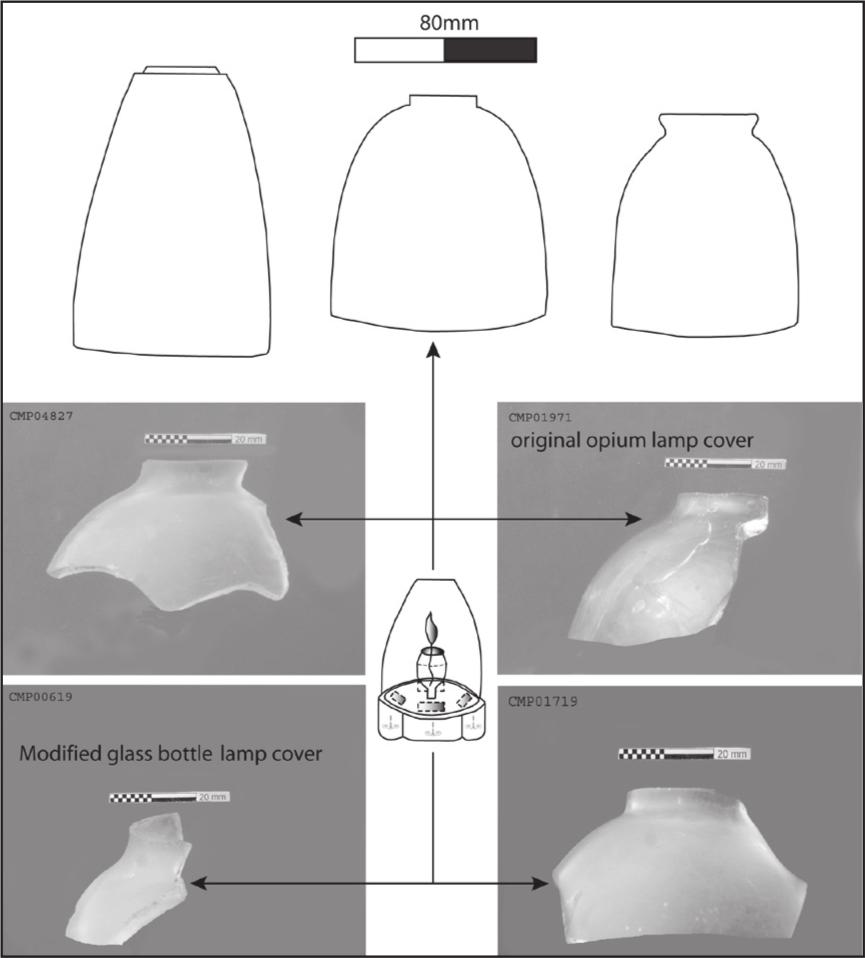

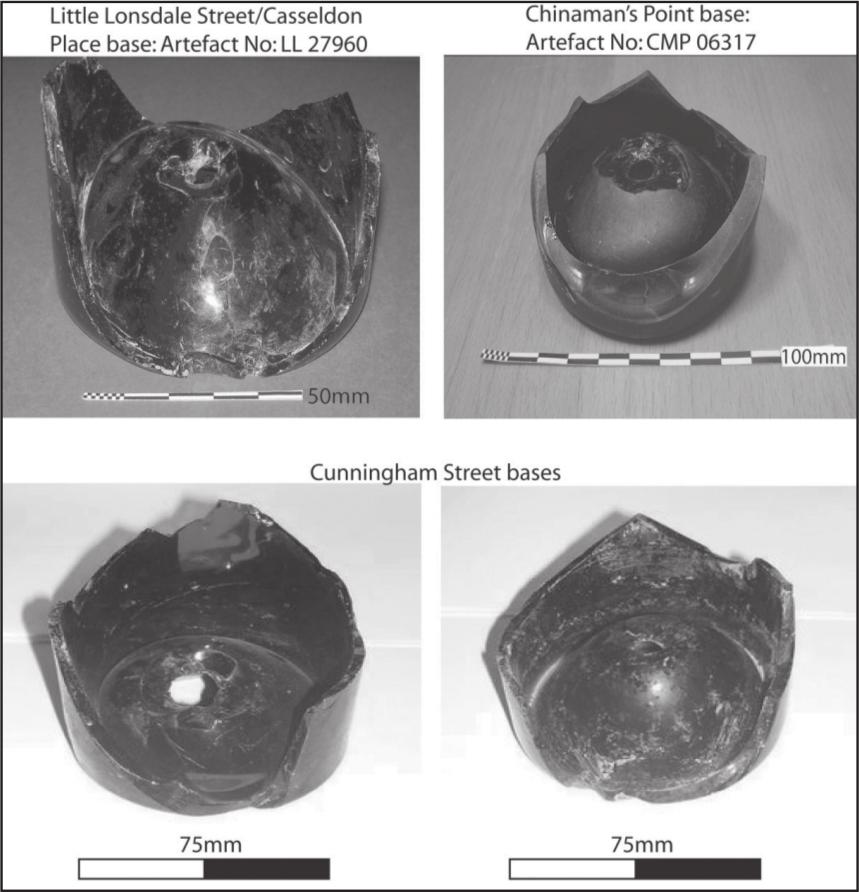

Thirty-six cylindrical aqua-green bottle base pieces, representing a minimum number of 30 individual bottles show evidence that the push-up sections have been deliberately and carefully knocked out. No complete modified base rims were represented, however accurate base measurements of 75 mm diameters were obtained. Each base has been modified through the use of a centre punch-type tool, tapped at intervals around the bottle base rim, effectively removing the push-up section and leaving distinct markings on the base shards (figure 6.23).

Modified glass artefacts at overseas Chinese sites have been noted by Ritchie & Bedford (1983: 248) McCarthy (1986: 36) and from the Chinaman’s Point site (discussed below with opium-related materials). These are usually suggested to be covers for opium heating lamps and are comprised of shoulder and neck bottle sections. However, no overseas Chinese sites display base modifications similar to the type recovered from Chinaman’s Point. The Chinaman’s Point base modifications are all at the bottle’s base, making the manufactured item too long in the body for use as opium-heating lamp covers.

Figure 6.23 Deliberate modification marks are clearly visible on these bottle base fragments.

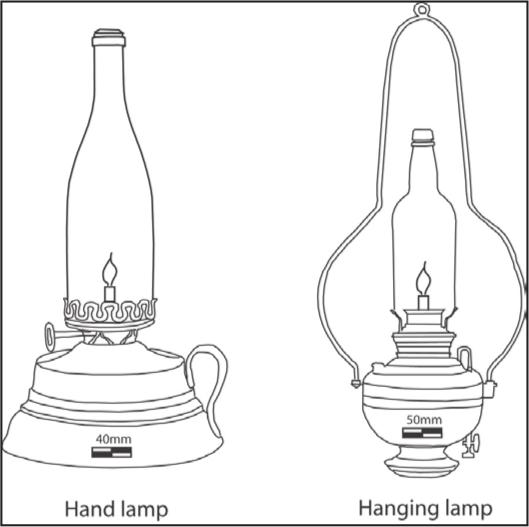

During Australia’s colonial period, domicile lamp bases and lamp chimneys were standard household items used for general lighting. Lamp chimneys are made of thin and delicate glass, with a range of standard base sizes up to and exceeding 75 mm in diameter (Cuffley 1973: 186). By using oil or kerosene lamp bases or any form of solid container to hold a wick or candle base, an aqua-green bottle without a base section would have made a robust lamp chimney (figure 6.24). The occupants at Chinaman’s Point may have produced such items for general domestic lighting purposes or for fishing at night. 113

Figure 6.24 Reconstruction of oil lamps using modified bottles as substitute lamp chimneys.

In Wards’s (1954: 198, 203) anthropological study of a Chinese fishing village, she notes that fishermen often work at night using:

glass globes and mantles for the purse-seine fishermen’s bright lights … the bright kerosene lights are used to attract fish … bright cat’s-eye lights [can] be seen all around the coast.